ABSTRACT

We have engineered a Human Immune System (HIS)-reconstituted mouse strain (DRAGA mouse: HLA-A2. HLA-DR4. Rag1 KO. IL-2Rγc KO. NOD) in which the murine immune system has been replaced by a long-term, functional HIS via infusion of CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) from cord blood. Herein, we report that the DRAGA mice can sustain inducible and transmissible H1N1 and H3N2 influenza A viral (IAV) infections. DRAGA female mice were significantly more resilient than the males to the H3N2/Aichi infection, but not to H3N2/Hong Kong, H3N2/Victoria, or H1N1/PR8 sub-lethal infections. Consistently associated with large pulmonary hemorrhagic areas, both human and murine Factor 8 mRNA transcripts were undetectable in the damaged lung tissues but not in livers of DRAGA mice advancing to severe H1N1/PR8 infection. Infected DRAGA mice mounted a neutralizing anti-viral antibody response and developed lung-resident CD103 T cells.

These results indicate that the DRAGA mouse model for IAV infections can more closely approximate the human lung pathology and anti-viral immune responses compared to non-HIS mice. This mouse model may also allow further investigations into gender-based resilience to IAV infections, and may potentially be used to evaluate the efficacy of IAV vaccine regimens for humans.

KEYWORDS: Humanized mouse, pro-coagulation Factor 8 mRNA, natural IAV transmission, CD103 lung-resident T cells, IAV gender-based resilience

Introduction

Influenza infections pose one of the world’s greatest challenges for health and impose a significant economic burden. Seasonal influenza type A virus (IAV) infections kill between 15,000 and 35,0000 people in the U.S.A. every year.1,2 According to the Center for Diseases Control (CDC) reports, some 90% of deaths occur in individuals with high risk of acquiring the infection, such as children younger than age 5 and elderly older than age 65, pregnant women and women up to 2 weeks post-pregnancy, American Indians and Alaska Natives, patients with inherited or acquired immunodeficiency or preexistent medical conditions including asthma, blood disorders such as sickle cell disease, chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic heart and kidney disease, or individuals with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease (HIV/AIDS), or individuals under corticosteroid or chemotherapeutic regimens.1,2 While the A/H1N1 subtypes are responsible for common seasonal infections in humans, the A/H3N2 viruses are notoriously affect the elderly population.

IAVs are enveloped orthomyxoviruses with a segmented RNA genome of negative polarity3 encoding at least 17 proteins.4,5 The hemagglutinin (HA) viral protein is the most abundant and immunogenic envelope protein, which plays a critical role in viral attachment and entry into cells and induction of protective antibodies.6,7-8 IAV replication in the lung epithelium occurs in three major stages starting with HA binding to sialic acid residues linked to alveolar cell surface that expresses α-2,6 or α-2,3 glycans, and followed by attachment of virions, endocytosis into the alveolar cells, and further trafficking to the lysosomes.9 The acidic microenvironment in lysosomes promotes activation of matrix protein-2 channel (M2 protein), which favors dissociation of viral ribonucleoprotein (RNP) and its transport to the host cell nucleus where viral RNA replication occurs.10 At the same time, the HA and other viral envelope proteins are being released in the cytosol and concentrated in alveolar lipid rafts. Finally, the newly synthesized viral RNA progeny in the host nucleus of dying alveolar cells are released into the cytosol where they bud with viral proteins to form new virions that are further released upon cleavage of sialic acid residues by the viral neuraminidase (NA). Newly generated virions can further invade adjacent alveolar cells and propagate the infection.11

Protection against influenza infections relies on both the innate and adaptive immune responses. Thus, viral proteins from dying infected cells are up taken by antigen-presenting cells (APC) such as macrophages and dendritic cells where they are digested by lysosomal proteases, assembled as MHC class II-peptide complexes on the APC surface, and presented to the CD4 T cells, which in turn prime the B cells toward secretion of specific antibodies. Furthermore, specific antibodies targeting the viral envelope proteins interfere with hemagglutinin-mediated attachment of virions to alveolar cells8,12 and the release of virions progeny from infected cells by blocking the NA enzyme or viral replication. These antibodies can bind to the viral M and NP proteins13,14 or killing the infected cells by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC).15 At the same time, CD8 T cells can efficiently kill infected cells by releasing Perforin and Granzyme cytotoxic molecules upon MHC class I-viral peptide interaction on the surface of infected cells.16,17

While the mouse and ferret models of IAV infection are unable to fully recapitulate the complexities of human lung pathology and immune responses, humanized mice expressing a Human Immune System (HIS) may overcome such limitations.18,19 However, among several HIS-humanized mouse models reported so far, some limitations still exist, i.e., short-term reconstitution with T and B memory cells, interference with previously antigen-experienced T and B memory cells from the human donor, development of acute or chronic Graft Versus Host Disease (GVHD), insufficient numbers of human T cells, sub-optimal human B cell development, lack of immunoglobulin class switching, poor HSC engraftment and inefficient homeostasis of human immune cells.20,21 We have recently described two new humanized mouse strains (DRAG mouse: HLA-DR4. RAG1 KO. IL-2Rγc KO. NOD, and DRAGA mouse: HLA-A2. HLA-DR4. RAG1 KO. IL-2Rγc KO. NOD) knocked out for the murine immune system whilst expressing a long-lived functional human immune system (HIS) upon engraftment with human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) from cord blood.22,23 Both DRAG and DRAGA mice responded by specific antibodies to infection or immunization with malaria protozoans, HIV, ZIKA, malaria protozoan, influenza A/H1N1 PR8 virus,24 and scrub typhus.25,26,27-28

Although various wild-type and humanized mouse models have been described for a number of viral infections (i.e., HIV, EBV, HCV, HBV, HCMV, DENV, HTL-1, HSV-2, HuNoV, JVC, Scrub typhus, ZIKA virus) and bacterial or parasitic infections (i.e., Plasmodium falciparum, Leishmania, Neisseria meningitides, Salmonella Typhi, Borrelia herrmesii, Streptococcus agalactiae group B sepsis, and Scrub Typhus),18 HIS-humanized animal models for infections with influenza type A infections (IAV) of groups 1 and 2 have not been established yet.

Herein, we show that the DRAGA mouse is an excellent HIS-humanized mouse model for inducible and transmissible H1N1 and H3N2 IAV infections, and that it closely recapitulates the human lung pathology of IAV infection and the antiviral antibody response.

Materials and methods

Mice

DRAGA mice were generated and reconstituted using HLA-matched-(HLA-A2.1, HLA-DRB1*0401), CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) isolated from the umbilical cord blood from four different human donors (New York Blood Bank, NY), as we previously described.22 The HIS-reconstituted DRAGA mice are under a provisional patent application by NMRC and USUHS and will be referred to hereafter as “DRAGA mice”, unless otherwise specified. To establish the peak of human immune reconstitution, DRAGA mice were monitored by FACS for blood circulating human T and B cell subsets (15–19% hu-CD4+ T cells, 5–7% hu-CD8+ T cells, 18–22% hu-CD19+ B cells), and by ELISA for human IgM and IgG in sera (600–800 μg/ml and, respectively, 400–500 μg/ml) (Tables 1Sa and 1Sb). DRAGA female and male mice were used in experiments at the age of 5–6 months and 4 months after CD34+ HSC infusion. The rate of human immune cell reconstitution in DRAGA mice. i.e. the percentage of mice that became fully reconstituted, was ≥95%. We did not observe significant differences in terms of levels of T and B cell reconstitution between males and females, nor differences in the level of HIS reconstitution from different cord blood donors.23 Mice care and HIS assessment was conducted under an approved animal use protocol in an AAALACi accredited facility in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals and in adherence to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, NRC Publication 2011 edition.

Viruses and infection protocols

DRAGA mice were first anesthetized with 25 mg/kg of ketamine/xylazine in 80 μL saline/mouse injected intraperitoneal (i.p.) prior to intranasal (i.n.) inoculation of LD50 sub-lethal doses of live virions (Charles River Labs). The LD50 infectious dose in 20 μl saline solution for each virus has been previously established in BALB/c mice. The following live-purified virions adapted for mouse by serial lung-to-lung passages have been used for infections: A/H1N1/PR/8/34 and A/H3N2/Aichi/2/68 (4x10−4 EID50/mL), A/H3N2/Victoria/3/75 (5.2x10−4 EID50/mL), and A/H3N2/Hong Kong/8/68 (2.5x10−4 EID50/mL). The experimental end-point for PR8 and Aichi infections was established whenever 35% loss in body mass occurred. For less virulent strains such as the Victoria and Hong Kong viruses, the experimental end-point was established at 50 dpi. The PR8 natural transmission experiment consisted of one sub lethally (LD50)-infected DRAGA male mouse caged together with 3 non-infected DRAGA male mice, and the experimental end-point was established at 50 d of co-habitation when one virus-recipient mouse recovered completely its body mass. All infection protocols were conducted under the IACUC protocols approved by USUHS (MED-18-048) and WRAIR/NMRC (ID#16-IDD-43) in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and in accordance with the principles set forth in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals,” Institute of Laboratory Animals Resources, National Research Council, National Academy Press, 1996 (Fig. 1S).

Hematoxylin-eosin (HE), immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence staining of lung sections

Lungs from naive and infected DRAGA mice were fixed for 2 h at room temperature in formalin 10%, or preserved in OCT (Tek O.C.T. compound, Sakura Finetek, Torrance) frozen blocks at −30°C until analyzed. 5 μ serial lung sections prepared from visibly affected and non-affected areas were either stained with HE or an Ab-HRP conjugate. For immunohistochemistry, serial 5μ cryosections were thawed for 30 min, fixed in BD Cytofix/Cytoperm fixation/permeabilization solution (BD, San Jose, CA) at room temperature for 10 min, and then blocked for 30 min at 37°C in 1X PBS containing 1% BSA. Sections were next incubated with 10 μg/ml mouse anti-human CD36 IgM (BD Pharmingen) at 37°C for 30 min followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 min with a rat anti-mouse IgM-HRP (1:10,000 dilution, clone #II/41, BD Pharmingen). The Antibody-HRP binding was visualized after a 5-min incubation with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) in buffered substrate (DAB Substrate Kit; ThermoScientific), counterstained with hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and imaged at 20,000 pixels with a Zeiss Axioscan Confocal microscope equipped with Zeiss Zen software. The percentage of human CD36+ epithelial cells (EC) expressed on the entire lung sections was scored and averaged using the Zeiss Zen software.

The immunofluorescence staining of 5μ lung sections has been performed using similar methodology like for the immunohistochemical staining using human CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD103 antibodies labeled with PE or FITC (BD Pharmingen) at 1:2000 dilution. Immunofluorescent stained slides were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and then blocked with goat serum, washed with PBS and mounted and sealed in Vectashield containing 1% DAPI. Stained slides were scanned in a Zeiss Axioscan Confocal microscope at 512 × 512 pixels and images were merged using the Zeiss Zen software.

RNA extraction from lungs and liver

To estimate the virus load by RT-qPCR in IAV-infected DRAGA mice, lungs were perfused with cold saline solution and RNA was extracted from visibly affected (hemorrhagic) and non-affected areas. Lung slices were snap-frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen until analyzed. Some 30 mg of snap-frozen lung tissue was lysed using lysing matrix D and homogenized in RLT buffer using a FastPrep-24 instrument (MP Biomedicals) as follows: 5 cycles at 6 m/s speed with 5 min rest period between cycles. Similarly, liver RNA was prepared from non-infected and infected DRAGA mice. Homogenized lung and liver samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and total RNA was extracted from individual samples using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and quantitated using a ThermoFisher NanoDrop-8000 instrument.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and nested RT-PCR

RNA extracts from A/H1N1/PR8/34 and A/H3N2/Aichi/2/1968 virions (Charles River) were used as positive controls for HA viral RNA. Briefly, 200 μg of live virions (based on protein content measured by biuret assay) were homogenized in RLT buffer, and total RNA was purified from homogenates using an RNEasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified RNA samples were quantitated using a NanoDrop-8000 instrument (ThermoFisher). Precise 2.5 ug aliquots of total lung RNA from individual mice were used as substrate for reverse transcription using SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (Fisher; Cat: 18064014). Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) was performed using an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System and software SDS v1.4. Amplification of viral hemagglutinin (HA) cDNA was carried out using in house designed primers for H1N1/PR8-HA (forward: GACACTGTTGACACAGTACTC, and reverse: AGAGCCATCCGGCGATGTTAC), and for H3N2/Aichi-HA (forward: CAGTGCTGAACGTGACTATGC and reverse: GGCTTAACTATTGTCCAATAAG). Specific primers for human IFN-γ were, forward: TCGGTAACTGACTTGAATGTCCA and reverse: TCCTTTTTCGCTTCCCTGTTTT, and for human TNF-α were forward: CCTCTCTCTAATCAGCCCTCTG, and reverse: GAGGACCTGGGAGTAGATGAG. Thermocycling parameters were: 10 min at 95°C, 30 sec at 95°C followed by 1 min at 60°C. The threshold cycle (CT) is the proportion of target copies in the sample and defined as the PCR cycle in which the gain in fluorescence due to accumulating amplicon products exceeds 10 standard deviations of the mean baseline fluorescence. CT data were collected from cycles 10 to 40.

Human GAPDH RNA was used as an internal control to normalize the RNA amount loaded in each agarose well. Amplification of human GAPDH cDNA internal control from lungs of infected or non-infected individual mice was carried out using commercially available forward and reverse primers (Qiagen, Cat: QT01658692). Q-PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 20 μl in SYBR Green Master Mix (ABI & ThermoFisher; REF: 4309155) containing forward and reverse primers at 1.25 μM, respectively. The normalized signal level was calculated based on the ratio to the corresponding GAPDH signal. RT-qPCR samples were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel containing 0.2% ethidium bromide.

Quantification of F8 mRNA (encoding factor VIII, from lung tissues of infected and non-infected DRAGA mice) required nested PCR (using a One-step RT-PCR kit # 210210, Qiagen) due to low endogenous transcript levels. A Flurochem E imager (Cell Biosciences) was used to image the gels. Briefly, a 50 μl reaction mix for each sample was prepared in 10 μl of 5x RT-PCR buffer, 2μl of dNTP mix, 2μl of Enzyme mix, 1uM of human or murine F8-specific primers, 1μM of RNA template, and RNAse-free water. Nested PCR primers to amplify the human F8 exon 22–23 junction region were as described,29 and similar primers to amplify this same region in mice were designed in-house. The murine F8 primers were: exon 22 FWD1: GTAGATCTGTTGGCACCAATG; exon 24 REV: CTTCCCTGGAGGTG AAGTCG; exon 22: FWD2: ACCAATGATTGTTCATGGCATCAAGA; exon 23 REV: TGCAAACGGATATATCGAGCAATAA. The human F8 primers were: exon 22 FWD1: GTGGATCTGTTGCACCAATG; exon 24 REV: CTCCCTTGGAGGTGAAGTCG, exon 22 FWD2: ACCAATGATTATTCACGGCATCAAGA; exon 23 REV: TGCAAACGGATGTATC GAGCAATAA. The conditions for the first reverse transcription reaction, using the outer primers only, were: 30 min at 50°C, an initial PCR activation at 95°C for 15 min, then 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, annealing at 50°C for 45 sec, followed by extension at 72°C for 1 min. Next, 5μl of PCR product was used as the substrate for the second (nested) PCR run under the same conditions described above, using the inner primers. The PCR amplicons were electrophoresed in a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide, and gel images were acquired using a Fluorochem E imager.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA was used to measure the titers of human IgM and IgG in sera from infected and non-infected (control) DRAGA mice according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bethyl Labs). Duplicate serum samples at 1:100 dilution in PBS/1% BSA/0.05% Tween 20 were incubated in 96-well plates coated overnight at 4°C with 5 μg/ml of UV-inactivated virions (with respect to protein content) or with 5 μg/ml of rHA viral proteins (Sino Biological, Wayne, PA) in 0.05M bicarbonate buffer pH 9.6, and blocked with 5% BSA in 1X PBS for 2 h at room temperature. 100 μl of 1:100 serum dilution was then added to duplicate wells overnight at 4°C, plates were washed 3 times with 1X PBS containing 0.05% Tween, and the anti-human IgM-HRP conjugate (dilution 1:200,000) or IgG-HRP conjugate (dilution 1:150,000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, Inc.) was added to the plates for 2 h at room temperature. Plates were washed 3 times with 1X PBS, and TMB substrate (BD Biosciences) was added to the wells (100 μl/well) for 10 min followed by addition of 50 μl/well of 0.18M H2SO4 stop solution. Optical density (OD) of bound Ab-HRP conjugates was recorded at 450 nm by an ELISA reader (Molecular Devices).

Hemagglutination inhibition assay (HIA)

The virus neutralization capacity of sera from infected DRAGA mice was measured by HIA, as we previously described.30 Briefly, 5 ml of fresh chicken red blood cells (RBC, Lampire Biologicals Labs, Inc.) were washed in 1X PBS at 1,200 rpm at 4°C until the supernatant was clear of hemolysate. 50 μl/well of serial sera dilutions by a factor of 20 made in 1X PBS and a constant, standardized amount of virions in 50 μl of 1X PBS/well were incubated together for 2 h at room temperature in 96-well round-bottom plates in the presence of 50 μl/well 1% chicken RBCs. The HI titer was defined as the highest serum dilution able to fully inhibit hemagglutination of chicken RBCs.

Biostatistics

Significance in the loss of body weight and virus load in the lungs of infected DRAGA mice was calculated by comparing average reductions in the body weight and, respectively, the RT-qPCR CT values from female and male mice within the same group using the paired t test and Mann–Whitney test, with p ≤ 0.05 considered significant. For ELISA measurements of viral-specific Abs in sera of infected mice, the standard deviation (± SD) between 2 repeated measurements was calculated at 99% interval of confidence using Sigma Plot software v.12.

Results

DRAGA mice sustain sub-lethal infection with A/H1N1/PR8 virus

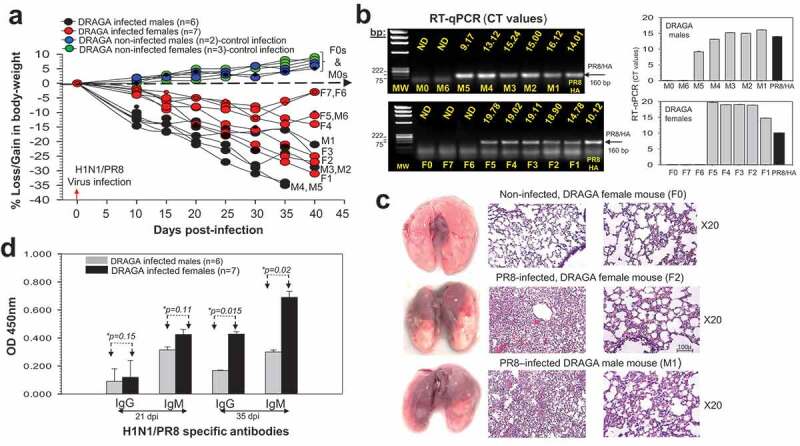

DRAGA female and male mice were infected by intranasal (i.n.) route with a BALB/c-equivalent LD50 sub-lethal dose of H1N1/PR8/A/34virus. Loss in body mass was detected by 10 d post-infection (dpi) for both female and male mice, and the infection was sustained for 35 to 45 d (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Infection of DRAGA mice with A/H1N1/PR8 virus. (a) Body weights of PR8-infected DRAGA female mice (F1-F7, red symbols) and male mice (M1-M5, dark symbols). Shown is a control group of non-infected DRAGA female mice (n = 3, green symbols) and male mice (n = 2, blue symbols) marked as F0s and, respectively, M0s. Dashed arrow marks the borderline between body weight losses and gains; (b) Left panels, agarose gel electrophoresis of the PR8/HA amplicons revealed by RT-qPCR from lung RNA and the corresponding CT values for DRAGA infected F1-F7 female mice, M1-M6 male mice, a representative non-infected F0 female mouse and a representative non-infected M0 male mouse. Shown is the PR8/HA amplicon (positive control). ND, Not Detected. Right panels, RT-qPCR CT values in panel b-left panels; (c) Lungs (left panels), and HE staining of lung sections from affected areas (middle panels) and non-affected areas (right panels) from two representative infected DRAGA mice (F2 and M1 mice) in panel a analyzed at 40 dpi. Shown are the lungs and HE staining sections from the lungs of a representative non-infected DRAGA female mouse (F0, control infection). Large hemorrhagic (brownish) areas are visible on the lungs of infected female mouse F2 and male mouse M1; (d) ELISA titers in 1:100 sera dilution of PR8-specific IgG and IgM antibodies from infected DRAGA female and male mice in panel a, as measured at 21 and 35 dpi. Each mouse represents its own control, as sera from individual mice were measured by ELISA before infection and corresponding OD450 values for nonspecific signal-noise background to the virions-coated ELISA plates (OD450 = 0.015 to 0.045) were subtracted from values obtained at 21 dpi and 35 dpi. Shown are the significant difference (*p values) between infected female and male mice at 35 dpi.

Both infected female and male infected mice showed the presence of PR8/HA viral RNA in the lungs at 35 to 40 dpi with the exception of female mice F6 and F7 (Figure 1b). The lungs of infected mice showed lymphocyte infiltration and disrupted bronchi-alveolar architecture in the visibly affected areas at the time of analysis (35 dpi or 40 dpi, Figure 1c). Analysis of human sera antibodies to the PR8 virions by ELISA at 21 dpi and 40 dpi showed the presence of specific IgM and IgG antibodies that were significantly higher in female mice than male mice by 35 dpi (Figure 1d). Of note, in contrast to the rest of the infected mice, three female mice (F5, F6, and F7) and one male mouse (M6) showed signs of recovery from infection starting on day 21 post-infection, as they started to regain body mass (Figure 1a) and built higher anti-PR8 serum neutralization titers (Table 1).

Table 1.

HIA serum titers and percent virus neutralization in DRAGA mice sublethally (LD50)-infected with A/H1N1/PR8 virus (as per Figure 1b).

| DRAGA mice # | dpi | F0 | M0 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | Human sera |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | <1:20 | <1:20 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:60 | 1:60 | 1:80* | 1:80* | 1:60 | 1:40 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:60 | ||

| HIA serum titers to PR8 virus | 35 | <1:20 | <1:20 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:60 | 1:120 | 1:180* | 1:180 | 1:60 | 1:40 | 1:40 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:100 | 1:560** |

| 21 | < 25 | <25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 75 | 75 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 50 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 75 | ||

| Percent of virus neutralization | 35 | < 11 | <11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 33 | 66 | 100 | 100 | 33 | 22 | 22 | 11 | 11 | 56 |

F0, non-infected DRAGA female mouse; M0, non-infected DRAGA female mouse, F1-F7 female mice and M1-M6 male mice assessed at 21 and 35 dpi as per Figure 1b.

* Highest HIA titer among all mice at 21 and 35 dpi. Percent viral neutralization among individual mice in each group was calculated based on the highest HIA titer at days 21 and 35 post-infection.

** HIA titer of a vaccinated individual with 2014 AFLUVIA vaccine as assessed in 2015.

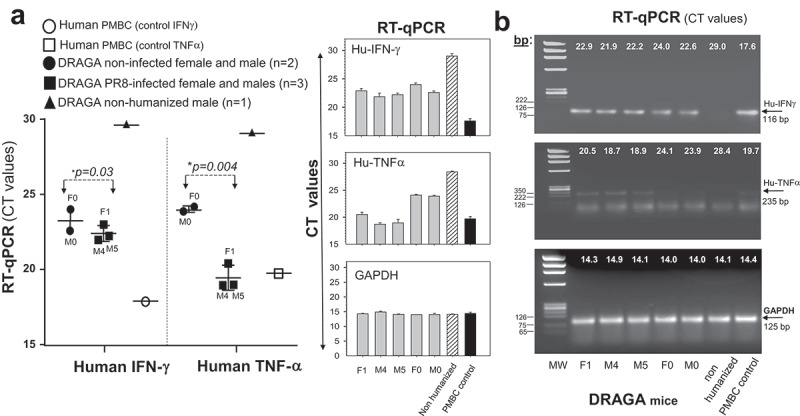

Since mice losing the body mass at a faster pace and showing high PR8/HA RNA expression in the lungs were categorized as severely infected, we measured by RT-qPCR the RNA expression of human IFNγ and TNFα inflammatory cytokines in their lungs. The so-called “cytokine storm” referring to the release of inflammatory cytokines by infiltrating lymphocytes in infected lungs can be a significant damaging event.29 Severely infected F1, M4, and M5 mice showed slightly, but not significantly higher IFNγ RNA expression in affected areas of the lungs than non-infected mice (*p = .03), whereas the TNFα RNA expression was significantly higher in the infected mice (*p = .004) (Figure 2). No differences in human IFNγ and TNFα RNA expression were detected by RT-qPCR between the non-affected lung area from infected and non-infected mice (data not shown), and no human IFNγ and TNFα RNA was present in non-HIS humanized DRAGA mice (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

RNA expression of inflammatory cytokines in the lungs of A/H1N1/PR8-infected DRAGA mice. Left panels, human IFNγ and TNFα RNA expression in the lung-affected areas of PR8-infected DRAGA mice advancing into severe infection, as per Figure 1. Shown are plotted RT-qPCR CT values for two representative infected male mice (M5 and M5) at 35 dpi, one representative infected female mouse (F1) at 40 dpi, one non-infected female mouse (F0), and one non-infected male mouse (M0). Right panels, agarose gel electrophoresis of human IFNγ and TNFα amplicons and corresponding RT-qPCR CT values.

Together, the results indicated that both DRAGA female and male mice were able to sustain a prolonged sub-lethal PR8 infection with human-like lung pathology, and to mount a virus-specific antibody response.

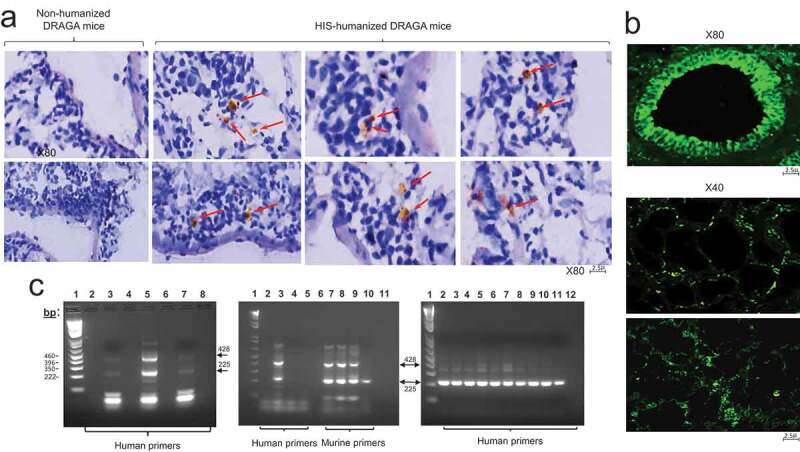

F8 mRNA expression is obliterated in the lungs of A/H1N1/PR8-infected DRAGA mice advancing to severe pneumonia

We have previously reported that human endothelial cells can be reconstituted in the liver of DRAGA mice upon infusion of human CD34+ HSC.22 Herein, immunohistochemical analysis of lungs from non-infected, DRAGA mice revealed the presence of human CD36+ in lung parenchyma and ECs (Figure 3a,b). Averaging the CLSM readouts of 5 different slides from each mouse at a resolution of 20,000 pixels in an AXIO SCAN Z1 microscope revealed that 4–5% of parenchymal lung cells and 12–18% of lung endothelial cells (EC) stained positive for human CD36, indicating engraftment of a quiet large number of human ECs in DRAGA mouse lungs. Since the ECs are the exclusive source of the coagulation protein Factor VIII, and large hemorrhagic areas were found in the lungs of DRAGA mice infected with the PR8 virus (Figure 1c, left panels), we compared the level of human and mouse F8 mRNA expression in the lungs of non-infected DRAGA (control) mice and PR8-infected DRAGA mice at 7, 14 and 21 dpi. RT-qPCR revealed that both human and murine F8 mRNA transcripts were present in the lungs of non-infected DRAGA mice (Figure 3c, left panel). However, the human F8 mRNA expression was undetectable by 14 dpi (Figure 3c, left panel) whilst murine F8 mRNA expression was undetectable by 21 dpi (Figure 3c, middle panel). Since we have previously reported the presence of human hepatic ECs in DRAGA mice, we next investigated whether the human F8 mRNA expression was affected in the livers of PR8 sub-lethally infected DRAGA mice. While the PR8 infection down-regulated both human and mouse F8 mRNA expression in the lungs, the human F8 mRNA expression in the liver of these mice remained unaffected (Figure 2c, right panel).

Figure 3.

F8 mRNA expression in the lungs and liver of A/H1N1/PR8-infected DRAGA mice. Affected lung areas and liver from PR8 sub lethally (LD50)-infected DRAGA mice were analyzed by RT-qPCR for human F8 mRNA expression at different time-points after infection. (a) Lung sections from non-infected/non HIS-reconstituted DRAGA mice and non-infected/DRAGA mice double stained with anti-human CD36-HRP conjugate (brownish color) and DAPI (blue color). Red arrows indicate the location of human CD36+ ECs throughout lung parenchyma; (b) A representative bronchiole from a non-infected DRAGA mouse stained with anti-human CD36-FITC conjugate showing a continuous layer of human CD36+ ECs (upper panel), and human CD36+ cells scattered throughout lung parenchyma and bronchiolar epithelia (lower two panels); (c) Nested RT-PCR using lung and liver RNA from PR8-infected DRAGA mice. Left panel, RT-qPCR using lung RNA and human F8-specific primers: lane 1, molecular markers; lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8, distilled water (dH2O); lane 3, non-infected, non-HIS reconstituted DRAGA female mouse (control human F8 mRNA); lane 5, non-infected, DRAGA female mouse (control human F8 mRNA); lane 7, infected DRAGA female mouse at 14 dpi. Middle panel, RT-qPCR using human and murine-specific F8 primers for lung RNA: lane 1, molecular markers; lane 2, human F8 primers alone; lane 3, non-infected, DRAGA female mouse; lanes 4 and 5, infected HIS-reconstituted DRAGA female mice at 7 dpi and, respectively, 14 dpi; lane 6, murine F8 primers alone; lane 7, non-infected, DRAGA female mouse; lanes 8 and 9, infected DRAGA female mice at 7 dpi and, respectively, 14 dpi; lane 10, infected DRAGA female mouse at 21 dpi; lane 11, dH2O. Right panel, nested RT-PCR using liver RNA and specific human F8 primers; lane 1, molecular markers; lanes 2–6, five different infected DRAGA female and male mice at 7 dpi; lanes 7–10, four different infected DRAGA female and male mice at 14 dpi; lane 11, human liver F8 mRNA (control); lane 12, dH2O.

These experiments revealed the presence of CD36+ human endothelial cells in the lung parenchyma and EC compartments of DRAGA mice. Furthermore, human F8 mRNA-expression in the lungs infected with a sub-lethal dose of PR8 virus, but not in the liver, became undetectable as early as 7 d post-infection.

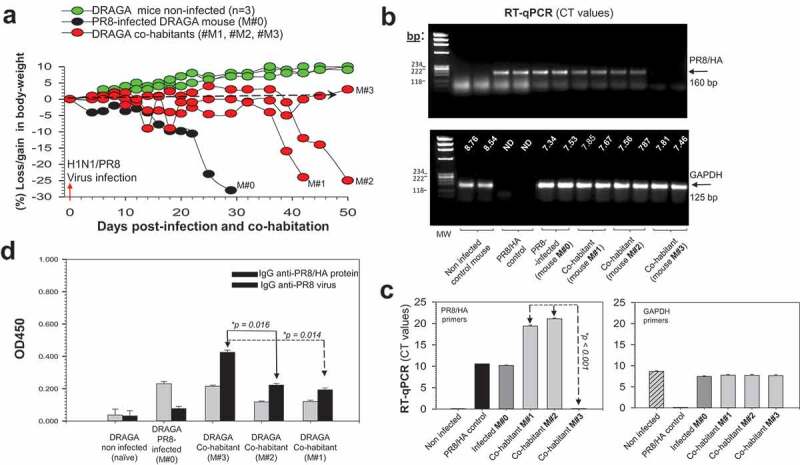

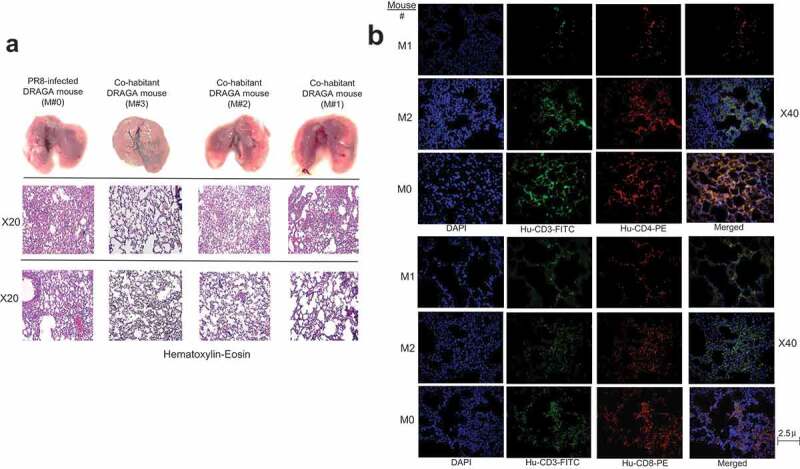

DRAGA mice develop human CD103 lung-resident T cells upon natural A/H1N1/PR8 infection

A DRAGA male mouse was sub-lethally infected i.n. with a BALB/c-equivalent LD50 dose of A/H1N1/PR8 virus and co-caged with 3 naïve DRAGA male mice. While the infected mouse (#M0) started to lose body mass significantly by 20 dpi, the co-habitant mice (#M1, #M2, and #M3 mice) showed a moderate loss in body weight (5–10%) at 20 dpi (Figure 4a). However, by day 38 of co-habitation, mice M#1 and M#2 showed a dramatic loss in body mass, whilst mouse M#3 started to regain body mass by day 41 of co-habitation. RT-qPCR revealed a significant amount of PR8/HA viral RNA in the lungs of PR8-infected mouse #M0 by 30 dpi and in the lungs of mice #M1 and #M2 by day 42 and, respectively, day 50 of co-habitation, as compared with the absence of PR8/HA viral RNA in the lungs of M#3 co-habitant measured by day 50 of co-habitation (Figure 4b,c).

Figure 4.

Natural transmission of A/H1N1/PR8 virus in DRAGA mice. (a) Body weights of a PR8-infected DRAGA male mouse (M#0) and its naïve DRAGA male co-habitants (#M1-M3). Dashed line marks the borderline between losses vs. gains in body mass; (b) Agarose gel electrophoresis of PR8/HA viral amplicons in the affected lung areas of infected transmitter mouse #M0 and its co-habitants #M1-M3. Shown are the corresponding RT-qPCR CT values measured at 29 dpi for the infected transmitter mouse #M0, and at 42 dpi and, respectively, 50 dpi for the co-habitant mice #M1 and #M2-M3 (upper panel), and the corresponding RT-qPCR CT values of housekeeping GAPDH gene (lower panel); (c) RT-qPCR CT values in panel b showing significant difference (*p value) between the virus load in the lungs of DRAGA male mice M#1 and M#2 versus M#3; (d) IgG-specific antibodies to PR8 virions and PR8/rHA viral protein measured by ELISA in 1:100 sera dilutions at 29 dpi for the infected transmitter mouse #M0 and 40 dpi for the #M1-M3 co-habitant mice. Each mouse represents its own control, as sera were individually measured by ELISA before infection and the corresponding OD450 values for nonspecific signal-to-noise binding to the virions-coated ELISA plates (OD450 nm = 0.015 to 0.045) and PR8/rHA (OD450nm = 0.15–0.18) were subtracted from those obtained at the time of measurement. Shown are the ± SD values for duplicate samples.

While the infected mouse #M0 mounted a weak human IgG response to the PR8 virions and showed low serum neutralization capacity, the co-habitant mice developed a stronger human IgG response and serum neutralization capacity (Figure 4d and Table 2). Co-habitant mice #M1 and #M2 showed hemorrhagic areas with lymphocyte infiltrations and distorted alveolar architecture in the lungs, whereas the co-habitant mouse #M3 following full recovery from the infection had few scattered hemorrhagic areas and less lung infiltration and bronchi-alveolar disruption in the left lobe (Figure 5a). Also, the co-habitant mouse #M3 developed a higher anti-viral serum neutralization capacity than its M#2 and M#3 counterparts (Table 2).

Table 2.

HIA serum titers and percent virus neutralization in a DRAGA mouse sub-lethally (LD50)-infected with A/H1N1 PR8 virus and its DRAGA co-habitants (as per Figure 4).

| DRAGA mice # | dpi | M0 | M1 | M2 | M3 | Human sera |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 1:20 | |||||

| HIA titers to PR8 virus | 42 | 1:60 | 1:560** | |||

| 50 | 1:60 | 1:240* | ||||

| Percent of Virus neutralization | 30 | 0.4 | ||||

| 42 | 25 | |||||

| 50 | 25 | 100 |

M0, DRAGA (infected) transmitter mouse; M1, M2, and M3, DRAGA

co-habitant recipient) mice with the infected M0 mouse. Percent viral neutralization among individual mice was calculated based on the highest HIA titer (M3 co-habitant mouse) measured at 50 dpi. * Highest HIA titer among all mice. *HIA titer of a vaccinated individual with 2014 AFLUVIA vaccine and assessed in 2015.

Figure 5.

Lung analyses of DRAGA mice naturally infected with A/H1N1/PR8 virus. (a) Lungs (upper panels), and HE staining of 5μ formalin-fixed sections from non-affected lung areas (middle panels) and affected lung areas (lower panel) harvested from PR8-infected DRAGA mouse #M0 mouse at 29 dpi, and from co-habitant mice #M1-M3 at 41 dpi and 50 dpi; (b) Immunofluorescence staining infiltrating CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T cells in the lungs of the H1N1/PR8 infected DRAGA male mouse (#M0) and two DRAGA male co-habitants (#M1 and #M2 in Figure 4a).

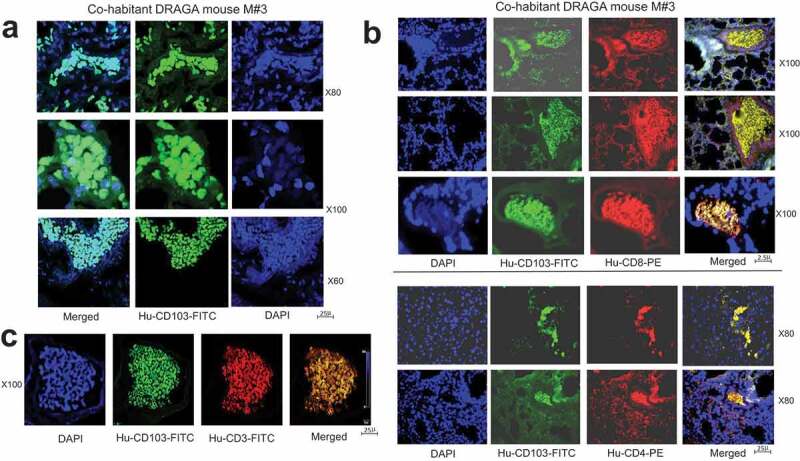

Both the infected M#0 mouse and co-habitants showed lung infiltration with CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T cells (Figure 5b). Interestingly, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) revealed that the co-habitant mouse #M3 but not the other two co-habitants, harbored human CD8+CD103+ and CD4+CD103+ cells, as well as CD3+CD8+CD103+ T cells in the lung EC niches (Figure 6). The CD103 antigen is the hallmark of lung-resident T memory-effector cells,31,32 among which, the CD8+CD103+ T resident cells have been recently regarded as powerfully cross-protective against IAV infections.33,34-35

Figure 6.

Analysis of CD103 lung-resident cells in A/H1N1/PR8 naturally infected DRAGA mouse. (a) human CD103 lung-resident cells in the lung ECs of A/H1N1/PR8 naturally infected DRAGA male mouse (#M3 in Figure 4a) that recovered from infection, as revealed by CLSM; (b) human CD8+CD103+ and CD4+CD103+ T resident cells in the lung EC niches of A/H1N1/PR8 naturally infected DRAGA male mouse (#M3 in Figure 4a); (c) human CD3+CD8+CD103+ T cells resident in the lung EC niches of A/H1N1/PR8 naturally infected DRAGA male mouse #M3 in Figure 4a, as revealed by CLSM.

These data strongly suggest that natural transmission of H1N1/PR8 virus occurred by direct contact (most likely through mouse licking) between the infected DRAGA mouse and its co-habitants. It is not unlikely that transmission of infection could have also occurred between the co-habitant mice, if a co-habitant acquired an early enough infection.

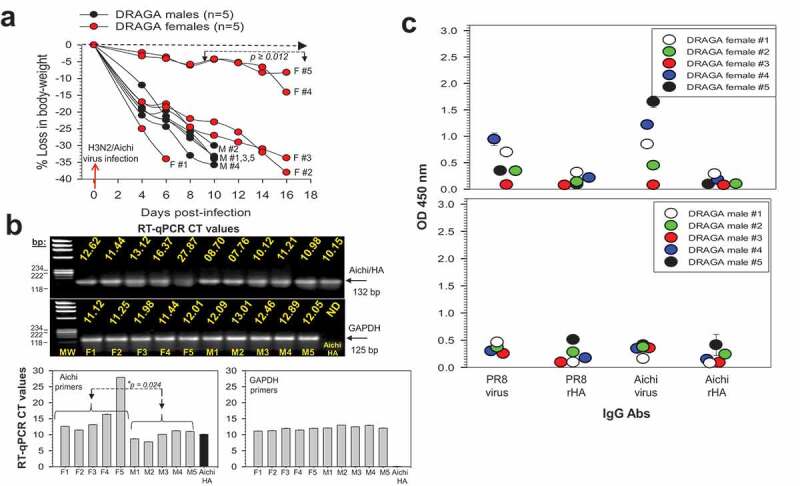

DRAGA mice sustain sub-lethal infections with A/H3N2 virus strains

DRAGA female and male mice were infected by the i.n. route with a BALB/c-equivalent LD50 sub-lethal dose of A/H3N2/Aichi virus, or with the A/H3N2/Victoria virus, or with the A/H3N2/Hong Kong virus. The Aichi-infected DRAGA female mice lost body mass at a significantly slower pace than their male counterparts between 10 and 16 dpi, with the median percent body weight reduction evaluated using the Mann–Whitney test (*p = .019). The paired t-test to evaluate average loss in body mass at 16 dpi indicated that indeed, the female mice were more resilient to Aichi infection than the male mice (*p = .012) (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Infection of DRAGA mice with A/H3N2 Aichi virus. (a) Body weights of Aichi-infected DRAGA female mice (F1-F5) and male mice (M1-M5). Significant difference in the loss of body mass between female and male mice is shown between 8 dpi and 16 dpi (*p ≥ .012). Dashed arrow marks the borderline between losses and gains in body weight; (b) Upper panels, agarose gel electrophoresis of Aichi/HA viral amplicons revealed by RT-qPCR in the affected areas of infected lungs from mice in panel a, at 6, 10, and 16 dpi. Shown are the RT-qPCR CT values using specific primers for Aichi/HA viral RNA and corresponding housekeeping GAPDH RNA amplicons. Lower panels, RT-qPCR CT values in panel b upper panels. Shown is a significant lower virus load in the lungs of DRAGA female mice than in male mice infected with Aichi virus (*p = .024); (c) Human IgG antibodies to Aichi virus and Aichi/rHA protein, and cross-reactive human IgG antibodies to H1N1/PR8 virus and H1N1/rHA protein from mice in panel a, as measured by ELISA in 1:100 sera dilution at 6, 10, and 16 dpi. Each mouse represents its own control, as sera were individually measured by ELISA before infection, and the corresponding OD450 values for nonspecific signal-to-noise binding to the Aichi virions-coated ELISA plates (OD450 = 0.025 to 0.055) were subtracted from those obtained post-infection. Shown are the ± SD values for duplicate samples.

RT-qPCR using specific primers for Aichi/HA viral RNA detected the virus in the lungs of all infected DRAGA mice up to 16 dpi, with the exception of female mouse F5, which showed signs of clearance by 16 dpi (Figure 6b, upper panels). Overall, the virus load in the lungs of infected DRAGA female mice was significantly lower than in the lungs of DRAGA male infected with the same amount of Aichi virions (*p = .024) (Figure 7b, lower panels).

Antibody serum titers measured at the time of euthanasia (10 dpi for male mice and 16 dpi for 4 female mice) indicated that both female and male mice mounted a human IgG antibody response to Aichi virions, although the overall titers were slightly weaker in males than in females (Figure 7c). Also, both female and male mice developed a human IgG cross-reactive response to A/H1N1/PR8 virions, but with serum titers lower than those against the Aichi virions. Among all infected mice, the female mice F4 and F5 mounted the highest human IgG response and serum neutralization capacity against Aichi virions (Figure 7c upper panel, and Table 3). However, the cross-neutralization titers to the PR8 virions were lower than to the Aichi virions in all Aichi-infected mice (Table 3).

Table 3.

HIA titers and percent A/H3N2/Aichi virus neutralization and AH1N1 PR8 virus cross-neutralization in DRAGA female and male mice sublethally (LD50)-infected with A/Aichi H3N2 virions (as per Figure 7).

| DRAGA mice # | dpi | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | Human sera |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIA titer to Aichi virus | 10 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:320** | |||||

| 16 | 1:40 | 1:40 | 1:40 | 1:120* | 1:120* | |||||||

| Percent of Aichi virus neutralization | 10 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | ||||||

| 16 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 100 | 100 | |||||||

| HIA titer to PR8 virus | 10 | 1:20 | 1:40 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:560** | |||||

| 16 | 1:40 | 1:40 | 1:40 | 1:60* | 1:60* | |||||||

| Percent of PR8 virus cross-neutralization | 10 | 33 | 66 | 33 | 33 | 33 | ||||||

| 16 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 100 | 100 |

M1-M5, male mice assessed at 10 dpi, and F1-F5 female mice assessed at 16 dpi. * Highest HIA titer to Aichi virus, and, respectively, to PR8 virus among all mice in each group. Percent viral neutralization and cross-neutralization among individual mice was calculated based on the highest HIA titer to AICHI, or the highest HIA titer to PR8 viruses at 10 dpi for male mice, and, respectively, 16 dpi for female mice. ** HIA titers of a vaccinated individual with 2014 AFLUVIA vaccine and assessed in 2015.

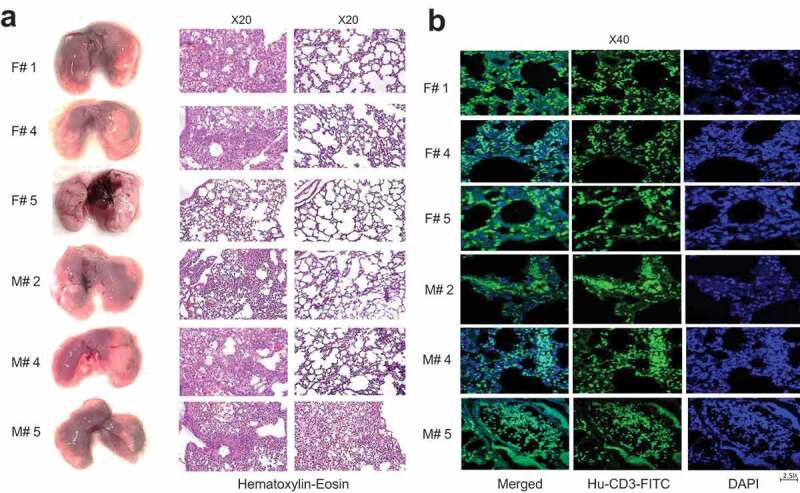

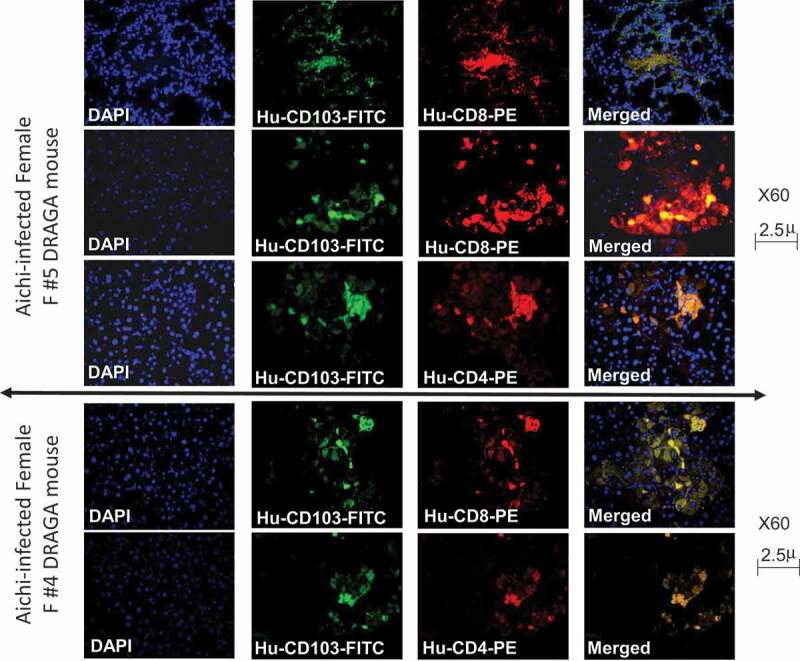

Lung analyses of DRAGA mice sub-lethally infected with the Aichi virus carried out at the time of euthanasia (6, 10, and 16 dpi) revealed large hemorrhagic areas in the lungs of all mice except the female mouse F5 (Figure 8a). With the exception of female mouse F5 (showing signs of recovery according to the gain in body mass and virus clearance from the lungs by 16 dpi), the HE and immunohistochemical staining of lung sections from the affected areas of all Aichi-infected DRAGA mice showed disrupted bronchi-alveolar architecture (Figure 8a) and higher T-cell infiltration (Figure 8b). Interestingly, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) revealed that female mouse F5 showing signs of recovery but not the other female and male mice harbored human CD8+CD103+ and CD8+CD103+ T cells in the lung EC niches (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Lungs analysis of DRAGA mice infected with A/Aichi (H3N2) virus. (a) Lungs from 3 representative Aichi-infected DRAGA females (F1, F4, and F5) and 3 males (M2, M4, and M5) (left panels) and analyzed at 6, 10, and 16 dpi as per Figure 7a. Left panels, lungs with visibly affected (hemorrhagic brownish) areas. Of note, no visible hemorrhagic areas are present in the lungs of female mouse F5 showing signs of recovery from infection; middle panels, HE-stained lung sections from visibly affected areas of mice in the left panel; right panels, corresponding HE-stained lung sections from non-affected areas of mice in the left panel; (b) human CD3+ T-cell infiltrates in the lung parenchyma of three representative mice in panel b, as developed by immunofluorescence staining of formalin/OCT-fixed sections from the affected lung areas.

Figure 9.

Analysis of CD103 lung-resident cells in an A/H3N2 Aichi-infected DRAGA mouse. Upper panels, human lung-resident CD8+CD103+ T cells in the lung EC niches of DRAGA female mouse (#F5 in Figure 7a) that recovered from infection, as revealed by CLSM; Lower panels, human lung-resident CD4+CD103+ cells in the lung EC niches of DRAGA female mouse (#F5).

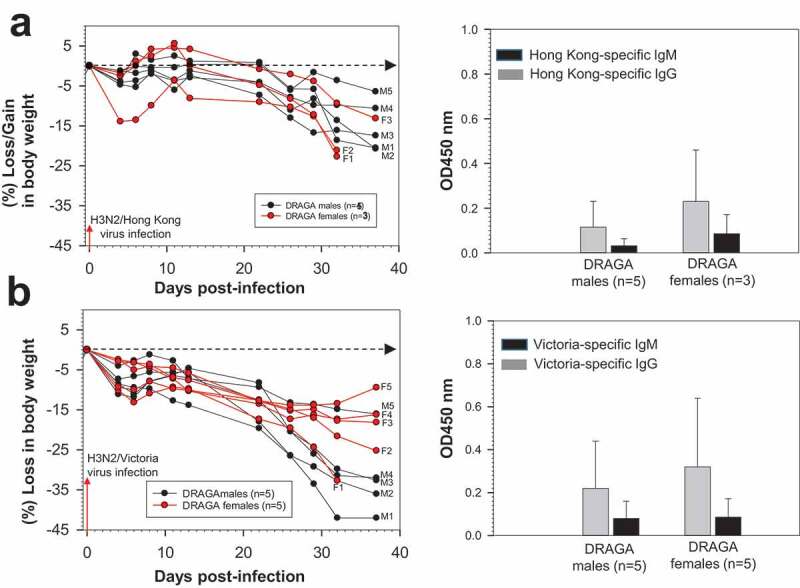

All DRAGA mice were able to sustain sub-lethal (LD50) infections with A/H3N2 Hong Kong and Victoria viruses, with no significant loss in body mass between female and male mice at the experimental end-point (38 dpi) (Figure 8a,b, left panels). Both groups of Hong Kong- and Victoria-infected DRAGA female and male mice developed virus-specific, human IgG antibodies (Figure 5a,b, right panels) and serum neutralization capacity (Table 4). Similar to the mice infected with PR8 and Aichi viruses, both Victoria- and Hong Kong-infected DRAGA female and male mice showed lung infiltration with lymphocytes, disrupted bronchi-alveolar architecture, and lung hemorrhagic areas at the experimental end-point (34 and 38 dpi, data not shown).

Figure 10.

Infection of DRAGA mice with A/Hong Kong (H3N2) and A/Victoria (H3N2) viruses. (a) Body weights of 3 Hong Kong-infected DRAGA female mice (F1 to F3) and 5 male mice (M1 to M5) (left panel) and their virus-specific, human IgM and IgG responses (right panel) measured at 32 dpi by ELISA in 1:100 sera dilutions; (b) Body weights of 5 Victoria-infected DRAGA female mice and 5 male mice (left panel) and their virus-specific, human IgM and IgG responses (right panel) measured at 32 dpi by ELISA in 1:100 sera dilutions. Each mouse represents its own control, as sera were individually measured by ELISA before infection and the corresponding OD450 values for nonspecific binding to the virions-coated ELISA plates (OD450 = 0.015 to 0.025) were subtracted from those obtained at 32 dpi.

Table 4.

HIA serum titers and percent virus neutralization in DRAGA mice sublethally (LD50)-infected with A/H3N2 Hong Kong or A/H3N2 Victoria virions. (as per Figure 10).

| HK-infected mice # | dpi | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | F1 | F2 | F3 | Humans era | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIA titers | 1:40 | 1:40 | 1:40 | 1:100* | 1:100* | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:40 | 1:320** | |||

| Percent of virus neutralization | 40 | 40 | 40 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 20 | 40 | ||||

| Victoria-infected mice # | 32 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | |

| HIA titers | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:20 | 1:80 | 1:20 | 1:40 | 1:40 | 1:40 | 1:120* | 1:560** | |

| Percent of virus neutralization | 32 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 66 | 16 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 100 |

M1-M5 male mice and F1-F3 female mice infected with Hong Kong virus and assessed at 32 dpi; M1-M5 male mice and F1-F5 female mice infected with Victoria virus and assessed at 32 dpi. * Highest HIA titer to the virus. Percent viral neutralization among individual mice was calculated based on the highest HIA titer in each group. ** HIA titers of a vaccinated individual with 2014 AFLUVIA vaccine and assessed in 2015.

Together, these experiments demonstrated that DRAGA mice can sustain sub-lethal infections with A/H3N2 Aichi, Hong Kong, and Victoria viruses, and they were able to mount virus-specific human IgM and IgG antibodies with neutralization capacity.

Discussion

The present work was built on our earlier establishment of a new strain of humanized mouse (DRAGA mouse: HLA-A2. HLA-DR4. RAG1 KO. IL-2Rγc KO. NOD) that can be reconstituted long-term with fully functional human T and B cell compartments.22,23 We have previously reported that DRAGA mice that lack the murine immune system and express a functional human immune system can be used to generate and assess the therapeutic efficacy of cross-reactive, human anti-influenza monoclonal antibodies targeting a conserved B cell epitope (180WGIHHPPNSKEQQNLY195) of hemagglutinin (HA) envelope protein of PR8/A/34 (H1N1) virus. This sequence is highly conserved among seven different IAV heterosubtypes.24 Both DRAG and DRAGA mouse strains were shown to respond to several pathogens with specific human IgM and IgG antibodies.24-28

Our data indicate that the DRAGA mouse is a viable model for studies of human-like lung physiopathology, and of humoral and cellular immune responses to infections with IAVs such as A/H1N1/PR8 and A/H3N2 subtypes of Aichi, Victoria and Hong Kong viruses.

The IAV subtypes used in this study have been isolated from patients and mouse adapted by lung-to-lung passages. Previous studies of mice infected with human IAV strains utilized virus adaptation to overcome the cross-species barrier. This inter-species barrier may exist when considering that influenza viruses bind preferentially to α2,6-linked sialic acid (SA) receptors on human epithelial and endothelial (EC) cells of the upper and lower respiratory tract, whereas mice express α2,3-linked sialic acid (SA) receptors on their ECs.36,37-38 However, zoonotic influenza viruses such as the avian and swain strains prefer α2,3-SA receptors,39 some zoonotic viruses, e.g. the A/H5N1 avian virus, have been isolated from human nasal α2,6-SA receptors.40,41-42 On the other hand, there is evidence that some zoonotic viruses, e.g. the avian A/H5N1 and A/H7N9 subtypes as well as human H1N1 viruses, can infect mice and ferrets.43,44 Thus, the binding flexibility of IAV strains between human α2,6- and mouse α2,3-linked SA receptors on ECs and the presence of human lung ECs in DRAGA mice indicate that DRAGA mice can be infected with human IAVs without the need for mouse adaptation.

Humans do not acquire a lethal dose of influenza viruses by airborne transmission, but they may advance to acute pneumonia with severe complications, depending on the replication rate of a particular virus subtype and the host immune status. Therefore, our experiments employed BALB/c-equivalent LD50 sub-lethal doses of A/H1N1 and A/H3N2 infections in DRAGA mice. Interestingly, when given same infectious dose, both female and male DRAGA mice were more sensitive to A/H3N2 Aichi than to A/H1N1 PR8 sublethal infection. Thus, many Aichi-infected mice lost over 25% body mass by 10 dpi, whilst most of PR8-infected mice lost 25% to 35% body at later time points, i.e. by 25 dpi. This observation is in agreement with a previous study in ferrets suggesting a higher virulence of A/H3N2 than A/H1N1 subtypes.45 Furthermore, DRAGA female mice infected with PR8, Aichi, or Victoria viruses mounted a slightly stronger specific human IgG response, which was correlated with better recovery and viral clearance from the lungs. Also, DRAGA female mice, but not the male mice showed a less pronounced loss in body mass during the course of PR8, Aichi, and Victoria infections, and a significantly longer survival after Aichi infection.

Was gender-based resilience to Aichi infection related to a different rate of HIS-reconstitution between female and male DRAGA mice, or to a particular cord blood used for HIS-reconstitution, or to the time elapsed after CD34+ HSC infusion? Notta et al. described better engraftment of human HSC in female than in male NSG mice,46 although this observation does not relate to the gender of the cord bloods, as the authors used a pool of cord bloods without gender identification. Using the same NRG mice transplantation approach of cord blood HSCs as that used by Notta et al., Volk and collaborators found a significant discrepancy only in reconstitution of human CD3+CD8+ T cells at 10 weeks, but not at a later time after CD34+CD38− transplantation.47 DRAGA mice have been used in experiments at 4 months post-infusion of CD34+ HSCs. There are also other differences between Notta’s and Volk’s system, and our system. Thus, (1) their HIS reconstitution occurs via intra-femoral infusion of CD34 HSCs, whereas ours occurs by i.v. infusion, (2) the authors used for HIS-reconstitution NSG and NRG mouse strains without expression of HLA transgenes, whereas the DRAGA mouse is a NRG strain expressing the HLA molecules in the mouse thymus. We have previously reported that expression of HLA-DR4 transgene in the thymus of DRAGA mouse is essential for efficient human T cell reconstitution (≥95% rate of T-cell reconstitution) achieved at 4 months after CD34+ HSC infusion and regardless of mouse gender.22 Furthermore, both DRAGA female and male mice infected with the H1N1/PR8 virus or H3N1/Aichi virus were HIS reconstituted from the same batch of cord blood (Table 1Sa), which rules out a differential output after IAV infection due to the nature of the cord blood. Thus, only the H3N2/Aichi-infected DRAGA females but not the H1N1/PR8-infected ones were more resilient to the infection, and no difference in resilience to the IAV strains used in our experiments was detected in DRAGA male mice (Figure 1a vs. 6a). These data suggest a differential effect of the IAV heterosubtype on the resilience of DRAGA female mice regardless of the nature of the cord blood donor used for HIS reconstitution. This maybe also related to a differential rate of viral replication, since a number of murine and human studies including our unpublished results found that at the same viral load, some IAV strains are more virulent than others. It is plausible that sex hormones may play an important role in these observed variations.

A murine study by Robinson et al. suggested that the 17β-estradiol may have a role on the female-based resilience to IAV infections by reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines, favoring the recruitment of neutrophils into the lungs through increased production of chemoattractants, and augmentation of virus-specific cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells in the lungs.48 Conversely, several reports claimed that the male testosterone was associated with higher sensitivity to influenza infection in wild-type mice.49,50-51 These observations are consistent with studies by Sutherland et al. showing that androgen blockade in mice and humans supports thymic regeneration,52 which in turn enhances HIS reconstitution following HSC transplantation.53 However, studies by Nowak et al. suggested that different fractions of the androgen hormones in humans afflicted by IAV infections are modulatory, rather than implicitly immunosuppressive.54 In conclusion, the HIS characteristics of DRAGA mice together with the findings of gender-based resilience to IAV infection in this mouse model advocate for its suitability for further investigations on the mechanism(s) of gender-based resilience to IAV infections vis-a-vis the complexity of hormone-immune system interplay.

Acute viral pneumonia with alveolar hemorrhage in humans afflicted by seasonal IAV infections is a catastrophic clinical condition promoting bacterial superinfection and hypoxemic respiratory failure.55,56 We found striking evolution toward alveolar hemorrhage in sub-lethal infections of DRAGA mice with H1N1/PR8 and H3N2/Aichi viruses. Since it is known that upper and lower respiratory viruses including influenza viruses can suppress host transcription for a number of genes,57,58,59-60 we questioned whether pulmonary hemorrhage detected in H1N1/PR8-infected DRAGA mice may relate to virus-induced alterations of pro-coagulant processes in their lungs. FVIII protein, which is secreted by the vascular ECs,61,62 is an essential coagulation cofactor that amplifies thrombin generation, and hence blood clotting by accelerating the enzymatic activity of the serine protease factor IXa.29,63 We found that DRAGA lung epithelium was reconstituted with 10–12% of human CD36+ ECs. Furthermore, severe H1N1/PR8 infection of DRAGA mice resulted in undetectable human and murine F8 mRNA expression in the damaged lung areas. Further investigations will be required to determine if the decrease in F8 mRNA in the lungs correlates with the viral load, and whether the observed dramatic decrease is due to transcriptional regulatory events, or apoptosis of bronchi-alveolar ECs by the NP protein, or to widespread damage resulting from the “cytokine storm”, or a combination of any of these events. Many influenza virus strains are apoptotic, and the cytokine/chemokine storm is triggered by exaggerated IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxicity of CD8 T cells against infected bronchi-alveolar ECs.30 Indeed, lung analysis of some DRAGA mice with critical loss in body mass upon H1N1/PR8 infection showed slightly increased human IFNγ and TNFα, according to RT-qPCR. From a therapeutic standpoint, it is tempting to speculate that administration of FVIII, or of other agents to rebalance hemostasis in the lungs, may decrease pulmonary micro-hemorrhagic events in acute influenza infections. This could in turn reduce the risk of bacterial superinfections, although the risk of provoking pulmonary micro thrombosis needs to be considered. All these questions could be addressed in future studies utilizing the DRAGA model of IAV infections.

Influenza infection in rodents is routinely induced by i.n. inoculation or by release of aerosols with live virions released by nebulizers in enclosed chambers. Since mice do not cough or sneeze, the risk of airborne transmission is minimal or absent. However, direct contacts though licking between co-caged mice occur frequently. Early on, Eaton et al. claimed transmissibility by direct contact between wild-type mice,64 which was partially confirmed 20 y later by Shulman et al. who reported a 5% to 25% mouse-to-mouse transmissibility of several type A influenza viruses.65,66-67 Natural airborne transmission in ferrets was also reported to occur more often than in mice.68 The present study strongly suggest that transmissibility of A/H1N1/PR8 influenza infection can occur most likely by direct contact among DRAGA mice. Naive DRAGA mice co-caged with an infected DRAGA mouse became infected, thereby demonstrating that we have established the first HIS-mouse model for natural transmission of the H1N1/PR8 influenza virus. It is also plausible that a direct contact transmission may have been propagated between the co-habitant recipient mice themselves; this will be tested more rigorously in future studies.

While neutralizing antibodies are critical for clearing the virus from the lungs,6,69 lung-resident CD8+CD103+ T cells are transcriptionally poised for efficient anti-viral cross-protection.32,33 Interestingly, one DRAGA natural recipient of the PR8 virus and a female mouse infected with Aichi virus, both recovering from the infection, were able to mount strong neutralizing antibody response and to develop lung-resident CD103+ T cells.

In summary, this work indicates that DRAGA mouse models can recapitulate the human lung pathology, humoral immune responses, and lung resident immunity upon IAV group 1 and 2 infections. Pulmonary hemorrhage in H1N1/PR8-infected DRAGA mice advancing toward a severe stage has been also noticed, and it occurred in the context of down-regulation of lung ECs-synthesized F8 mRNA. As in humans afflicted by IAV infections, gender-based resilience to the infection, natural transmission of infection, and development of highly protective lung-resident CD103+ T cells have now been documented in IAV-infected DRAGA mice. Although the innate immune system is largely of mouse origin, the DRAGA mouse model provides compelling advantages for studies to evaluate the human immune adaptive responses to IAV vaccine regimens for humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hui Liu for assistance with RT-qPCR, Dennis McDaniel for assistance with CLSM microscopy and Cara Olsen for statistical analyses. T-D.B, SC, and KPP are US Government employees. The work of these individuals was prepared as part of government duties. Title 17 U.S.C. §105 provides that ‘Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.’ Title 17 U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Uniformed Services University, Department of Defense, or other Federal Agencies.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by USUHS under grants RO83193816 and G287252016 to T-D.B, and by NIH under grant R01 HL 130448 to KPP

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1713605.

References

- 1.Dushoff J, Plotkin JB, Viboud C, Earn DJ, Simonsen L.. Mortality due to influenza in the United States-an annualized regression approach using multiple-cause mortality data. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(2):181–87. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(CDC) CfDCap . Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza-United States, 1976–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010;59:1057–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kilbourne ED. Influenza. New York: (NY): Plenum; 1987. p. 234. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasin AV, Temkina OA, Egorov VV, Klotchenko SA, Plotnikova MA, Kiselev OI. Molecular mechanisms enhancing the proteome of influenza A viruses: an overview of recent discovered proteins. Virus Res. 2014;187(7):53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.viruses.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medina RA, Garcia-Sastre A. Influenza A viruses: new research developments. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(8):590–603. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wrammert J, Koutsonanos D, Li G-M, Edupuganti S, Sui J, Morrissey M, McCausland M, Skountzou I, Hornig M, Lipkin WI. Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. J Exp Med. 2011;208(1):181–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Throsby M, van den Brink E, Jongeneelen M, Poon LLM, Alard P, Cornelissen L, Bakker A, Cox F, van Deventer E, Guan Y, et al. Heterosubtypic neutralizing monoclonal antibodies cross-protective against H5N1 and H1N1 recovered from human IgM+ memory B cells. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e3942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang T, Tan GS, Hai R, Pica N, Petersen E, Moran TM, Palese P. Broadly protective monoclonal antibodies against H3 influenza viruses following sequential immunization with different hemagglutinins. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rust MJ, Lakadamyali M, Zhang F, Zhuang X. Assembly of endocytic machinery around individual influenza viruses during viral entry. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:567–73. doi: 10.1038/nsmb769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinto LH, Lamb RA. The M2 proton channels of influenza A and B viruses. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8997–9000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossman JS, Lamb RA. Influenza virus assembly and budding. Virology. 2011;411:229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klausberger M, Tscheliessnig R, Neff S, Nachbagauer R, Wohlbold TJ, Wilde M, Palmberger D, Krammer F, Jungbauer A, Grabherr R. Globular head-displayed conserved influenza H1 hemagglutinin stalk epitopes confer protection against heterologous H1N1 virus. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujimoto Y, Tomioka Y, Takakuwa H, Uechi G-I, Yabuta T, Ozaki K, Suyama H, Yamamoto S, Morimatsu M, Mai LQ, et al. Cross-protective potential of anti-nucleoprotein human monoclonal antibodies against lethal influenza A virus infection. Journal of General Virology. 2016;97(2):2104–16. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu W, Li H, Chen Y-H. N terminus of M2 protein could induce antibodies with inhibitory activity against influenza virus replication. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;35:141–46. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00009-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Holle TA, Moody MA. Influenza and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant EJ, Quiñones-Parra SM, Clemens EB, Kedzierska K. Human influenza viruses and CD8 (+) T cell responses. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;16:132–42. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant EJ, Josephs TM, Loh L, Clemens EB, Sant S, Bharadwaj M, Chen W, Rossjohn J, Gras S, Kedzierska K. broad CD8+ T cell cross-recognition of distinct influenza A strains in humans. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5427. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07815-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ernst W. Humanized mice in infectious diseases. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;49:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brehm MA, Wiles MV, Greiner DL, Schultz LD. Generation of improved humanized mouse models for human infectious diseases. J Immunol Methods. 2014;410:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akkina R. New generation of humanized mice for virus research: comparative aspects and future prospects. Virology. 2013;435(1):14–28. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akkina R. Humanized immune responses and potential for vaccine assessment in humanized mice. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25(3):403–09. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danner R, Chaudhari SN, Richie TL, Brumeanu T-D, Casares S. Expression of HLA class II molecules in humanized NOD.Rag1KO.IL2Rg KO mice is critical for the development and function of human T and B cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majji S, Wijayalath W, Shashikumar S, Pow-Sang L, Villasante E, Brumeanu TD, Casares S. Differential effect of HLA class-I versus class-II transgenes on human T and B cell reconstitution and function in NRG mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28093. doi: 10.1038/srep28093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendoza M, Ballesteros A, Qiu Q, Pow Sang L, Shashikumar S, Casares S, Brumeanu T-D. Generation and testing anti-influenza human monoclonal antibodies in a new humanized mouse model (DRAGA: NOD/RAG1 KO/IL-2Rγc KO/HLA-DR*0401+/HLA-A2.1+). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(2):345–60. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1403703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J, Peachman KK, Jobe O, Morrison EB, Allam A, Jagodzinski L, Casares SA, Rao M. Tracking HIV-1 infection in the humanized DRAG mouse model. Front Immunol. 2017;8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yi G, Xu X, Abraham S, Petersen S, Guo H, Ortega N, Shankar P, Manjunath N. A DNA vaccine protects human immune cells against Zika virus infection in humanized mice. E. BioMedicine. 2017;25:87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wathsala W, Majji S, Villasante EF, Brumeanu TD, Richie TL, Casares S. Humanized HLA-DR4. Rag KO. IL2Rγc KO. NOD (DRAG) mice sustain the complex vertebrate life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Malar J. 2014;13:386. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang L, Morris EK, Aguilera-Olvera R, Zhang Z, Chan T-C, Shashikumar S, Chao -C-C, Casares SA, Ching W-M. Dissemination of Orientiatsutsugamushi (scrub typhus) and immunological responses in the humanized DRAGA mouse model. Front Immunol. 2018;9:816. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dutta D, Gunasekera D, Ragni MV, Pratt KP. Accurate, simple, and inexpensive assays to diagnose F8 gene inversion mutations in hemophilia A patients and carriers. Blood Adv. 2016;1(3):231–39. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2016001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oldstone MB, Rosen H. Cytokine storm plays a direct role in the morbidity and mortality from influenza virus infection and is chemically treatable with a single sphingosine-1-phosphate agonist molecule. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014;378:129–47. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-05879-5_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topham DJ, Reilly EC. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells: from phenotype to function. Front Immunol. 2018;9:515. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pizzola A, Nguyen THO, Sant S, Jaffar J, Loudovaris T, Mannering SI, Thomas PG, Westall GP, Kedzierska K, Wakim LM. Influenza-specific lung-resident memory T cells are proliferative and polyfunctional and maintain diverse TCR profiles. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(2):721–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI96957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu T, Hu Y, Lee Y-T, Bouchard KR, Benechet A, Khanna K, Cauley LS. Lung-resident memory CD8 T cells (TRM) are indispensable for optimal cross-protection against pulmonary virus infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95:215–24. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0313180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkinson TM, Li CKF, Chui CSC, Huang AKY, Perkins M, Liebner JC, Lambkin-Williams R, Gilbert A, Oxford J, Nicholas B. Preexisting influenza-specific CD4+ T cells correlate with disease protection against influenza challenge in humans. Nat Med. 2012;18:274–80. doi: 10.1038/nm.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slutter B, Pewe LL, Kaech SM, Harty JT. Lung-airway-surveilling CXCR3hi memory CD8+ T cells are critical for protection against influenza a virus. Immunity. 2013;39:939–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shinia K, Ebina M, Yamada S, Ono M, Kasai N, Kawaoka Y. Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in human airways. Nature. 2006;440:435–36. doi: 10.1038/440435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Riel D, Munster VJ, de Wit E, Rimmelzwaan GF, Fouchier RAM, Osterhaus ADME, Kuiken T. H5N1 virus attachment to lower respiratory tract. Science. 2006;312:399. doi: 10.1126/science.1125548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ibricevic A, Pekosz A, Walter MJ, Newby C, Battaile JT, Brown EG, Holtzman MJ, Brody SL. Influenza virus receptor specificity and cell tropism in mouse and human airway epithelial cells. J Virol. 2006;80:7469–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02677-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicholls JM, Bourne AJ, Chen H, Guan Y, Peiris JM. Sialic acid receptor detection in the human respiratory tract: evidence for widespread distribution of potential binding sites for human and avian influenza viruses. Respir Res. 2007;8:73. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subbarao K, Klimov A, Katz J, Regnery H, Lim W, Hall H, Perdue M, Swayne D, Bender C, Huang J, et al. Characterization of an avian influenza A (H5N1) virus isolated from a child with a fatal respiratory illness. Science. 1998;279:393–96. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu X, Tumpey TM, Morken T, Zaki SR, Cox NJ, Katz JM. A mouse model for the evaluation of pathogenesis and immunity to influenza A (H5N1) viruses isolated from humans. J Virol. 1999;73(7):5903–11. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.7.5903-5911.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maines TR, Lu XH, Erb SM, Edwards L, Guarner J, Greer PW, Nguyen DC, Szretter KJ, Chen L-M, Thawatsupha P. Avian influenza H5N1 viruses isolated from humans in Asia in 2004 exhibit increased virulence in mammals. J Virol. 2005;79(18):11788–800. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11788-11800.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lakdawala SS, Shih AR, Jayaraman A, Lamirande EW, Moore I, Paskel M, Sasisekharan R, Subbarao K. Receptor specificity does not affect replication of virulence of pandemic H1N1 influenza virus in mice and ferrets. Virology. 2013;446:349–56. doi: 10.1016/jvirol.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joseph T, McAuliffe J, Lu B, Jin H, Kemble G, Subbarao K. Evaluation of replication and pathogenesis of avian influenza A/H7subtype viruses in a mouse model. J Virol. 2007;81(19):10558–66. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00970-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryan KA, Slack GS, Marriott AC, Kane JA, Whittaker CJ, Silman NJ, Carroll MW, Gooch KE. Cellular immune response to human influenza viruses differs between H1N1 and H3N2 subtypes in the ferret lung. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0202675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Notta F, Doulatov S, Dick JE. Engraftment of human hematopoietic stem cells is more efficient in female NOD/SCID/IL-2Rgc-null recipients. Blood. 2010;115(18):3704–07. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Volk V, Schneider A, Spineli LM, Grosshenning A, Stripeke R. The gendar gap: discrepant human T-cell reconstitution after cord blood stem cell transplantation in humanized female and male mice. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:596–97. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson PD, Hall OJ, Nilles TL, Bream JH, Klein SL. 17β-estradiol protects females against influenza by recruiting neutrophils and increasing virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses in the lungs. J Virol. 2014;88:4711–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02081-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steeg V, Klein SL. Sex and sex steroids impact influenza pathogenesis across the life course. Semin Immunopathol. 2019;41(2):189–94. doi: 10.1007/s00281-018-0718-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Furman D, Hejblum BP, Simon N, Jojic V, Dekker CL, Thiebaut R, Tibshirani RJ, Davis MM. System analysis of sex differences reveals an immunosuppressive role for testosterone in the response to influenza vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(2):869–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321060111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klein SL, Hodgson A, Robinson DP. Mechanisms of sex disparities in influenza pathogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92(1):67–73. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0811427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sutherland JS, Goldberg GL, Hammett MV, Uldrich AP, Berzins SP, Heng TS, Blazar BR, Millar JL, Malin MA, Chidgey AP. Activation of thymic regeneration in mice and humans following androgen blockade. J Immunol. 2005;175:2741–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sutherland JS, Spyroglou L, Muirhead JL, Heng TS, Prieto-Hinojosa A, Prince HM, Chidgey AP, Schwarer AP, Boyd RL. Enhanced immune system regeneration in humans following allogeneic or autologous hemopoietic stem cell transplantation by temporary sex steroid blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1138–49. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nowak J, Pawlowski B, Borkowska B, Augustyniak D, Drulis-Kawa Z. No evidence for the immunosuppressive handicap hypothesis in male humans. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7392. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25694-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gilbert CR, Vipul K, Baram M. Novel H1N1 influenza A viral infection complicated by alveolar hemorrhage. Respir Care. 2010;55:623–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kenedy ED, Roy M, Norris J, Fry AM, Kanzaria M, Blau DM, Shieh W-J, Zaki SR, Waller K, Kamimoto L. Lower respiratory tract hemorrhage associated with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Influenza Other Resp Viruses. 2013;7(5):761–65. doi: 10.1111/irv.12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang S, Chi X, Wei H, Chen Y, Chen Z, Huang S, Chen J-L. Influenza A virus-induced degradation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B contributes to viral replication by suppressing IFITM3 protein expression. J Virol. 2014;88:8375–85. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00126-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khaperskyy DA, McCormick C. Timing is everything: coordinated control of host shutoff by influenza A virus NS1 and PA-X proteins. J Virol. 2015;89(13):6528–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00386-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lyles DS. Cytopathogenesis and inhibition of host gene expression by RNA viruses. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64(4):709–24. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.4.709-724.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rivas HG, Schmaling SK, Gaglia MM. Shutoff of host gene expression in influenza A virus and herpes viruses: similar mechanisms and common themes. Viruses. 2016;8(102):2–26. doi: 10.3390/v8040102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fahs SA, Hille MT, Shi Q, Weiler H, Montgomery RR. A conditional knockout mouse model reveals endothelial cells as the principal and possibly exclusive source of plasma factor VIII. Blood. 2014;123(24):3706–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-555151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Everett LA, Cleuren AC, Khoriaty RN, Ginsburg D. Murine coagulation factor VIII is synthesized in endothelial cells. Blood. 2014;123(24):3697–705. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-554501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davie EW, Fujikawa K, Kisiel W. The coagulation cascade: initiation, maintenance, and regulation. Biochemistry. 1991;30(43):10363–70. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eaton MD. Transmission of epidemic influenza virus in mice by contact. J Bacteriol. 1940;39(3):229–41. doi: 10.1128/JB.39.3.229-241.1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schulman JL. Experimental transmission of influenza virus infection in mice. IV. Relationship of transmissibility of different strains of virus and recovery of airborne virus in the environment of infector mice. J Exp Med. 1967;125(3):479–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.125.3.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schulman JL, Kilbourne ED. Airborne transmission of influenza virus infection in mice. Nature. 1962;195:1129–30. doi: 10.1038/1951129a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schulman JL, Kilbourne ED. Experimental transmission of influenza virus infection in mice. Some factors affecting the incidence of virus infection in mice. J Exp Med. 1963;118:267–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.118.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Herfst S, Schrauwen EJA, Linster M, Chutinimitkul S, de Wit E, Munster VJ, Sorrell EM, Bestebroer TM, Burke DF, Smith DJ. Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1/ virus between ferrets. Science. 2012;336(6088):1534–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1213362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nguyen HH, Tumpey TM, Park H-J, Byun Y-H, Tran LD, Nguyen VD, Kilgore PE, Czerkinsky C, Katz JM, Seong BL, et al. Prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of avian antibodies against influenza virus H5N1 and H1N1 in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.