Abstract

Purpose:

This study aimed to evaluate comprehensively; accuracy, repeatability and reproducibility of T1 and T2 relaxation times measured by magnetic resonance fingerprinting using -corrected fast imaging with steady-state precession (FISP–MRF).

Methods:

The International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/National Institute of Standards and Technology (ISMRM/NIST) phantom was scanned for 100 days, and six healthy volunteers for 5 days using a FISP–MRF prototype sequence. Accuracy was evaluated on the phantom by comparing relaxation times measured by FISP–MRF with the reference values provided by the phantom manufacturer. Daily repeatability was characterized as the coefficient of variation (CV) of the measurements over 100 days for the phantom and over 5 days for volunteers. In addition, the cross-scanner reproducibility was evaluated in volunteers.

Results:

In the phantom study, T1 and T2 values from FISP–MRF showed a strong linear correlation with the reference values of the phantom (R2 = 0.9963 for T1; R2 = 0.9966 for T2). CVs were <1.0% for T1 values larger than 300 ms, and <3.0% for T2 values across a wide range. In the volunteer study, CVs for both T1 and T2 values were <5.0%, except for one subject. In addition, all T2 values estimated by FISP–MRF in vivo were lower than those measured with conventional mapping sequences reported in previous studies. The cross-scanner variation of T1 and T2 showed good agreement between two different scanners in the volunteers.

Conclusion:

-corrected FISP-MRF showed an acceptable accuracy, repeatability and reproducibility in the phantom and volunteer studies.

Keywords: International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/National Institute of Standards and Technology system phantom, magnetic resonance fingerprinting, quantitative imaging

Introduction

MRI has been widely used for diagnosis of various diseases for many years. However, conventional weighted images are practically qualitative images, and quantitative images for measuring physical properties, such as T1 and T2, have been expected to more directly reflect and help evaluate disease characterization,1–4 follow-up,5 and monitoring of treatment effects6,7 in recent years. Several methods have been proposed for quantification of T1 and T2 values; the gold standard methods for T1 and T2 quantifications are an inversion recovery spin echo method with varying inversion time (TI) and a single spin echo method with varying TE, respectively. However, both methods require long acquisition times, and multiple tissue properties cannot be simultaneously obtained. Recently, many techniques have been proposed to shorten acquisition times8–13 and to simultaneously quantify T1 and T2 values.14–16

Magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF) is a novel concept, which uses transient-state signal evolutions sensitive to several quantitative tissue properties, including T1 and T2 relaxation times.17 Varying acquisition parameters for MRF such as flip angle (FA) and TR lead to efficient signal encoding and in combination with varying k-space trajectories to efficient tissue quantification because of the both spatially and temporally incoherent acquisition. In MRF, quantitative tissue properties are derived by pattern matching between the acquired signal evolution and the entries of a dictionary containing simulated signal evolutions for a wide range of tissue parameters, such as T1 and T2 relaxation times. In addition, it has been reported various types of MRF; fast imaging with steady-state precession (FISP) to obtain T1, T2 and proton density values,18 balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) to obtain T1, T2 and ΔB0,17 and echo planar imaging (EPI) to obtain T1 and .19

For the clinical use of quantitative imaging, accuracy, repeatability and reproducibility are the most important properties. Some studies have been reported on these three properties in other quantitative methods, using a multidynamic multiecho sequence20 or quantification of relaxation times and proton density by multiecho acquisition of a saturation-recovery using turbo spin-echo readout (QRAPMASTER) pulse sequence.21 Few studies have already reported the properties of MRF; however, they mainly focused on a phantom study22 and in vivo studies.23,24 In addition, only few studies have used B1 correction, although RF field () inhomogeneity has been known to introduce errors in quantitative MR including MRF.25 However, to our knowledge, no study has covered all of the three properties with FISP–MRF including a correction method. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the -corrected FISP–MRF comprehensively; accuracy, repeatability and reproducibility of T1 and T2 measurements on the ISMRM/NIST system phantom and healthy volunteers with two different scanners.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our university hospital. For human scans, informed written consent was obtained from all volunteers before examination.

MRF protocol

Two 3T scanners (MAGNETOM Skyra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with 20-channel head receiver array coils were used for this study with a prototype implementation of a 2D FISP–MRF sequence as described in Jiang et al.18 For all studies, acquisition parameters of MRF were set to an in-plane spatial resolution of 1.2 × 1.2 mm2 and a slice thickness of 5.0 mm. After the inversion pulse (TI = 21 ms), the FISP acquisition started with a TE of 2 ms. FA and TR varied for each echo. FA varied between 0° and 74°, and TR varied between 12.1 and 15.0 ms. A total of 3000 TRs were acquired for each slice, resulting in a scan time of 40 s per slice. Each echo encoded an image by a single spiral readout with a variable-density k-space trajectory,26 using an inner and outer under-sampling ratio of 24 and 48. The spiral readout had a duration of approx. 6 ms for default parameters (FOV 300 mm, matrix 256 × 256, 48 spiral interleaves), and was followed by gradients for rewinding the moments on the x- and y-axes. To improve the incoherence of resulting under-sampling artifacts, the spiral trajectory was rotated by 82.5° from TR to TR using an interleave reordering scheme.27 The sinc-shaped excitation pulse had a duration of 2.0 ms and time bandwidth product of 8. The effect of the slice excitation profile on the net signal within a voxel was considered by the Bloch Simulation when calculating the dictionary.25 A spoiler gradient at the end of each TR applied a dephasing moment of 8.8 π along the slice axis. Before FISP–MRF acquisitions, a map28 was obtained. The mapping sequence consists a TurboFLASH sequence with a saturation recovery preparation module to encode the field (voxel size: 7 × 7 × 8 mm3, acquisition time 20 s). A correction based on the map was applied for each pixel in combination with a dictionary extended by a dimension. The dictionary consisted of 69,1497 atoms (8537 T1–T2 combinations, 81 B1 values) with T1 ranging from 10 to 4500 ms (increments of 10, 20, 40, and 100 for ranges 10–90, 100–1000, 1040–2000, and 2050–4500, respectively, in ms) and T2 ranging from 2 to 3000 ms (increments of 2, 5, 10, 50, 100, and 200 for ranges 2–98, 100–150, 160–300, 350–800, 900–1600, and 1800–3000, respectively, in ms). The atoms (fingerprints) contained in the dictionary are calculated by performing a Bloch Simulation of the MRF sequence for each parameter combination of T1, T2, and . In a second step, the fingerprints are compressed along the temporal dimension by a singular value decomposition (SVD) to 50 main components in order to reduce the size of the dictionary file and to accelerate the matching process.29 The matching is performed by calculating the inner product of the measured data with each dictionary entry along the T1 and T2 dimension, whereas the B1 dimension is determined based on the prescan measurement.25 The post processing time for creating the quantitative maps (spiral image reconstruction plus dictionary matching) is approximately 20 s per slice.

Phantom measurements

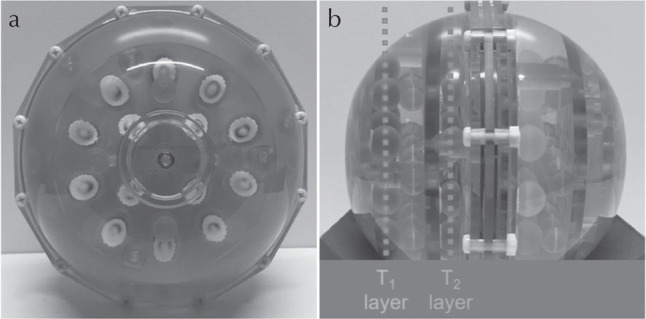

An International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/National Institute of Standards and Technology (ISMRM/NIST) system phantom (Fig. 1) was used to evaluate the accuracy and repeatability of -corrected FISP–MRF. This phantom consists of a deionized-water-filled spherical shell with an inner diameter of 200 mm. Inside the spherical shell is a framework, consisting of five plates rigidly connected with positioning rods. These plates support 57 fiducial spheres, a 14-element T1 array (T1-1 to -14), a 14-element T2 array (T2-1 to -14) and a 14-element proton density array which are designed to have a range of specific T1, T2, and proton density values. The spheres in the T1 array are filled with NiCl2-doped water, while the T2 spheres are filled with MnCl2-doped water. All solutions in the various compartments of the phantom are well-characterized and monitored by NIST for stability and accuracy.30

Fig. 1.

An International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/National Institute of Standards and Technology (ISMRM/NIST) MRI system phantom used in this study. (a) Frontal view and (b) lateral view.

This study focused on the T1 and T2 values; therefore, two slices, each corresponding to the T1 array and the T2 array in the ISMRM/NIST system phantom, were scanned for 100 days, with a minimum interval of at least 12 h between two adjacent scans. For each daily scan, the phantom was placed in the magnet for more than 30 min before the FISP–MRF acquisition to reduce the effects of liquid motion inside the phantom on measurements. During all measurements, temperature was recorded in the bulk water volume in the phantom after scanning in the MR scanner room using a digital thermometer with a resolution of 0.01°C and an accuracy ±0.05°C within ±2°C of the standard value (Extreme Accuracy Thermometer, 1227U09; S/N 170421710, Thomas Scientific, NJ, USA). T1 and T2 values of each sphere in the phantom were obtained from a circular ROI of diameter 10 mm, manually drawn on the T1 and T2 maps to exclude edge pixels. Accuracy was evaluated from these scans to compare the T1 and T2 values obtained by FISP–MRF with the reference values of the ISMRM/NIST system phantom provided by the manufacturer.31 The relative deviation of these values was displayed as correlation plots and Bland–Altman plots. Repeatability was characterized as coefficient of variation (CV), defined as the ratio between the standard deviation and the mean T1 and T2 values of the measurements over 100 days. The prescan is only accurate for T1 values larger than approx. 300 ms due to neglected magnetization recovery effects between preparation pulse and echo train as described in Chung et al.28 Therefore, spheres T1-7 to T1-14 and T2-11 to T2-14 were excluded from the evaluation.

In vivo examination

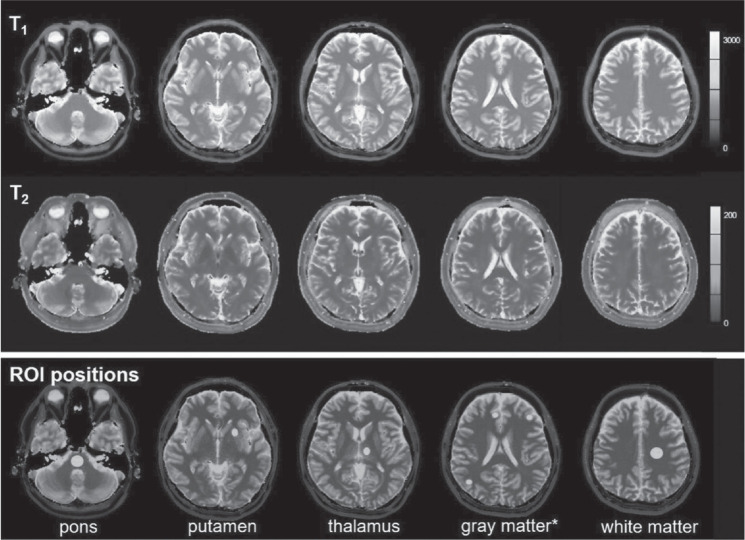

Six human volunteers (six males; mean age, 37 years; age range, 29–51 years) participated in this study and were scanned in two different MAGNETOM Skyra systems (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) (scanner A and B) on 5 days within a 2-month period. Human brain data were acquired from five different slices. These slices contained the internal auditory canal, basal ganglia, thalamus, corona radiata, and semi-oval center. Each scan was preceded by an automated slice positioning scout sequence (Siemens’s AutoAlign) for precise and reproducible anatomic coverage at each scanning session. The AutoAlign sequence was acquired by 3D FLASH using the following parameters: TR, 3.15 ms; TE, 1.37 ms; FOV, 260 mm; matrix, 160 × 160; slice thickness, 1.6 mm; FA, 8°; bandwidth, 540 Hz/pixel; acquisition time, 14 s. It involves automated alignment of slice positioning for head examinations, and thus enables easy and accurate patient follow-up. AutoAlign refers to the 3D MR brain atlas and automatically aligns the slice position in a standardized reproducible manner. In addition, body temperatures were monitored for all subjects on each day. Figure 2 shows an example of T1 and T2 maps obtained from one subject scanned by FISP–MRF, and ROIs were manually drawn on the pons, putamen, thalamus, white matter (WM), and gray matter (GM). Repeatability was characterized by the CV of the measurements from 5 days in the 2-month period at each scanner. The relative deviation of T1 and T2 values from the mean across both scanners was displayed as Bland–Altman plots to show the cross-scanner reproducibility. In addition, T1 and T2 values for the WM and the GM obtained by FISP–MRF were compared with those reported in previous publications.32–35

Fig. 2.

Example of T1 (upper row), T2 (middle row) maps, and ROI positions (lower row). *Mean of 3 ROIs.

Results

Phantom measurements

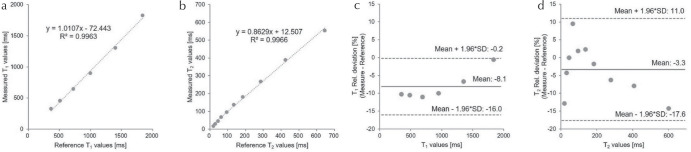

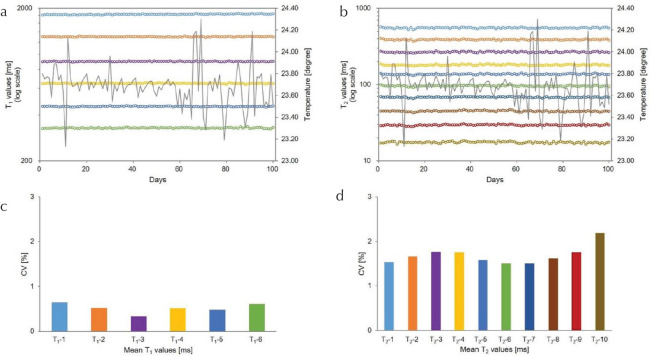

Table 1 summarizes the mean T1 and T2 values from measurements obtained over 100 days, alongside the reference values of the ISMRM/NIST system phantom. Figure 3 shows the mean T1 (a) and T2 (b) values from -corrected FISP–MRF over 100 days against the reference values. The results showed a strong linear correlation with reference values (R2 = 0.9963 for T1; R2 = 0.9966 for T2). The relative deviations of these mean T1 (c) and T2 (d) values over 100 days from the reference values are shown as Bland–Altman plots. The mean bias for T1 was −8.1%, and the 95% limits of agreement ranged from −16.0% to −0.2%. The mean bias for T2 was −3.3%, and the 95% limits of agreement ranged from −17.6% to 11.0%. Figure 4 shows T1 (a) and T2 (b) values of sphere phantoms on each layer over 100 days. The repeatability of these T1 (c) and T2 (d) values are characterized as the CVs over 100 days. The CVs of T1 and T2 values (T1 > 300 ms) were <1.0% and 3.0%, respectively. The temperature variation of the phantom over the 100 measurement days was within 1.06°C.

Table 1.

Summary of measured values and reference values

| T1 sphere no. | T1-1 | T1-2 | T1-3 | T1-4 | T1-5 | T1-6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured T1 (ms) | 1829 | 1305 | 899.2 | 646.1 | 455.7 | 329.7 | ||||

| Reference T1 (ms) | 1838 | 1398 | 998.3 | 725.8 | 509.1 | 367.0 |

| T2 sphere no. | T2-1 | T2-2 | T2-3 | T2-4 | T2-5 | T2-6 | T2-7 | T2-8 | T2-9 | T2-10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured T2 (ms) | 554.3 | 390.3 | 268.4 | 181.8 | 137.4 | 96.21 | 68.49 | 45.02 | 29.66 | 17.52 |

| Reference T2 (ms) | 645.8 | 423.6 | 286.0 | 184.8 | 134.1 | 94.40 | 62.51 | 44.98 | 30.95 | 20.10 |

Mean T1 and T2 values from measurements obtained over 100 days, alongside the reference values of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/National Institute of Standards and Technology (ISMRM/NIST) system provided by the manufacturer.

Fig. 3.

Correlation plots of T1 (a) and T2 (b), and relative deviation depicted as Bland–Altman plots of T1 (c) and T2 (d) comparing mean values from -corrected fast imaging with steady-state precession (FISP–MRF) over 100 days to the reference values of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/National Institute of Standards and Technology (ISMRM/NIST) system phantom. SD, standard deviation.

Fig. 4.

Results of T1 (a) and T2 (b) values obtained from - corrected fast imaging with steady-state precession (FISP–MRF) measurements for each sphere over 100 days. CV showing the repeatability of T1 (c) and T2 (d) values obtained from -corrected FISP–MRF over 100 days. CV, coefficient of variation.

In vivo examination

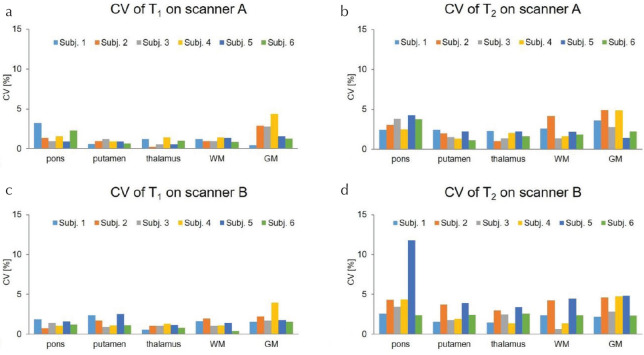

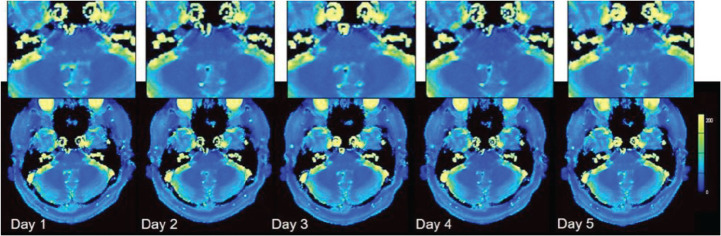

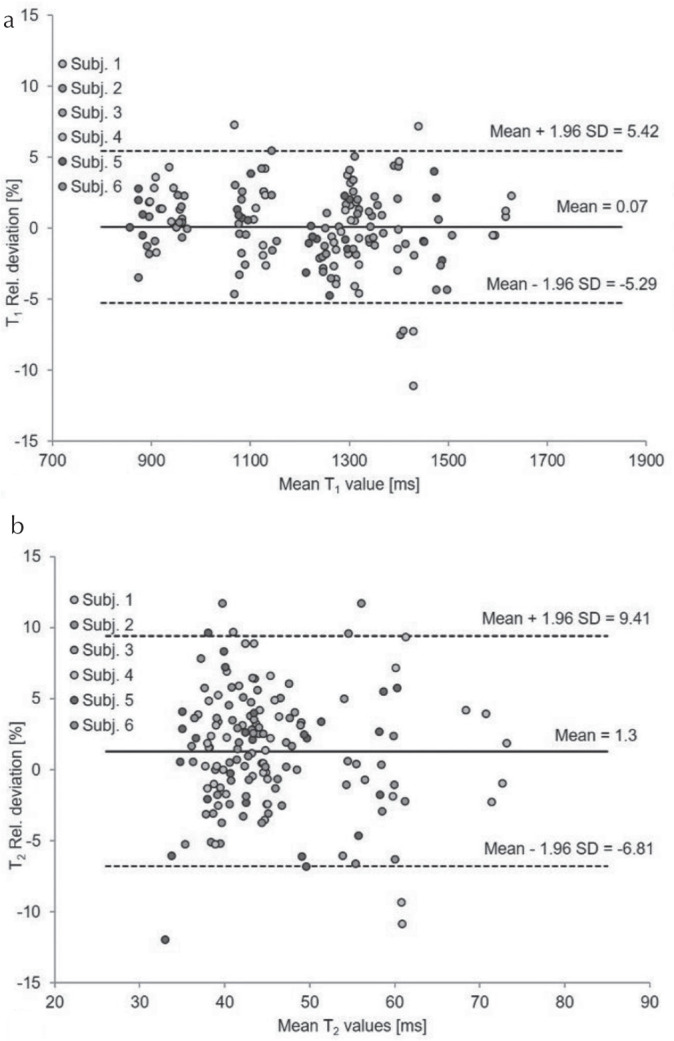

Figure 5 shows the CVs for T1 (a) and T2 (b) values obtained from the human brains by -corrected FISP–MRF over 5 days in the two different scanners. The CVs were <5.0% for both T1 and T2 values, aside from T2 values for the pons measured on scanner B system in subject 5. The T2 map and T2 values in the outlier subject are displayed in Fig. 6 and Table 2. Figure 7 shows the cross-scanner reproducibility of T1 and T2 measurements. The mean bias for T1 was 0.07%, and the 95% limits of agreement ranged from −5.29% to 5.42%. The mean bias for T2 was 1.3%, and the 95% limits of agreement ranged from −6.81% to 9.41%. Table 3 summarizes the mean T1 and T2 values from WM and GM for all volunteers across the five measurement days, compared with several previous literature reports.32–35 T1 values obtained from FISP–MRF were in agreement with previous literature; however, T2 values from FISP–MRF tended to be lower than reported in previous literature. Body temperatures of all subjects were stable across all days.

Fig. 5.

CV showing the repeatability of T1 (a and c) and T2 (b and d) values obtained from human brain using - corrected fast imaging with steady-state precession (FISP–MRF) on five separate days in two scanners (A and B). CV, coefficient of variation.

Fig. 6.

T2 maps on the scanner B system in subject 5.

Table 2.

T2 values for the pons measured on the scanner B system in subject 5

| Subject 5 on scanner B | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 (ms) | 41.5 | 37.6 | 39.8 | 30.9 | 41.5 |

T2 value on day 4 was relatively low among 5 days for this subject.

Fig. 7.

Relative deviation of T1 (a) and T2 (b) values obtained from -corrected fast imaging with steady-state precession (FISP–MRF) on volunteers in two scanners displayed as Bland–Altman plots showing the cross-scanner reproducibility. SD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

Mean T1 and T2 values from white matter and gray matter for all volunteers over 5 days, compared with previous literature

Discussion

According to the Quantitative Imaging Biomarker Alliance, the following three primary metrology areas of interest are critical to the performance of quantitative imaging biomarkers in preclinical or clinical settings: accuracy, repeatability, and reproducibility.36 In this study, the accuracy and repeatability of T1 and T2 measurements obtained from -corrected FISP–MRF were evaluated by scanning an ISMRM/NIST system phantom over 100 days. In addition, repeatability and cross-scanner reproducibility were also evaluated with healthy human brain data by using two scanners.

In phantom studies, the accuracy of T1 and T2 relaxation times, measured by FISP–MRF, was comparable to previous literature.22 Although the previous authors used an inversion- recovery spin-echo method and a multiple single-echo spin-echo method to characterize the T1 and T2 values as a gold standard, we compared the T1 and T2 values obtained by FISP–MRF with reference values from the ISMRM/NIST system phantom, which showed good agreement. The applied mapping method is only accurate for T1 values larger than approximately 300 ms28 and thus imposed a limitation on the T1 range of the FISP–MRF implementation used in this study. Consequently, spheres T1-7 to T1-14 and T2-11 to T2-14 were excluded from the evaluation. Furthermore, the minimum TR used in FISP–MRF was 12.1 ms, which was at the lower boundary for accurate T2 estimation.22

Repeatability of T1 relaxation times measured by FISP–MRF in this study were equal to the previous study.22 As for the CVs of T2 values, this results (<3.0%) was much improved compared with the previous study (<7.0%).11 correction might have contributed to this improvement in this study because variation affects T2 values more than T1 values.37 The T2 value is known to be more affected by temperature fluctuations than the T1 value; however, there is little correlation between temperature fluctuation and T2 values across 100 days in this study. Recently, some studies suggested to simultaneously map with MRF which could estimate not only T1 and T2 values but also values efficiently by using an MRF sequence only,38–40 which might allow estimations of T1 and T2 in a wider range and avoid misregistration between the prescan and the actual MRF acquisition.

The accuracy and repeatability of T1 and T2 values could also have been affected by the dictionary resolution, which is a trade-off between the image reconstruction time and the accuracy and/or repeatability. A previous study reported that the accuracy of T1 and T2 values are not affected by different dictionary resolutions, and the repeatability could be improved when finer dictionary step sizes were used.22 Therefore, repeatability could be further improved by using a finer dictionary resolution in the future.

In healthy human brains, T1 and T2 values obtained by -corrected FISP–MRF over 5 days provided comparable repeatability with that in the ISMRM/NIST system phantom over 100 days according to the CVs. However, the CV of the T2 value in the pons region on scanner B system for subject 5 was found to be >11% (Fig. 5d). The T2 value on day 4 was relatively low among 5 days for this subject. Potentially the T2 values were affected by motion that occurred during the scan because T2 values were found to be more sensitive to motion, especially through-plane motion like respiration, than T1 values.41

High cross-scanner reproducibility was achieved over both scanners. T1 values could be reproduced with approx. 10% variability and T2 values with approx. 15% variability, within the 95% limits of agreement. Note that measurement variation might still be caused by positioning differences and physiological changes are particularly relevant for inter-scanner variation even though the AutoAlign method was used. According to the repeatability and cross-scanner reproducibility, T1 values seemed to be more stable than T2 values in FISP–MRF that was similar to the previous reports.18,22

As for the T2 values obtained by FISP–MRF, all T2 values were lower than those previously reported in some publications,32–35 which were based on Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) type acquisition schemes. However, at present there is no method which can measure “ground-truth” T1 and T2 values in vivo, due to scan time restrictions but also due to complex in vivo tissue properties such as partial-volume effects, diffusion, magnetization transfer etc. FISP–MRF uses an unbalanced gradient moment, which can mitigate the banding artifacts observed in the bSSFP–MRF. Recently, a previous study suggested that the spoiler gradient used in FISP–MRF might lead to an underestimation of T2 values because of its sensitivity to diffusion motion42 and off-resonance dependency.43 To solve this limitation, some studies tried to quantify diffusion44 and off-resonance39 simultaneously with T1 and T2 values in MRF. Further technical developments which add more tissue-related parameters into MRF will be expected for the precise quantification in the future.

Conclusion

-corrected FISP–MRF measurements of T1 and T2 values showed high accuracy and repeatability over 100 days across a wide range of T1 and T2 values in the ISMRM/NIST system phantom, and high repeatability and reproducibility over 5 days in healthy human brains. T2 relaxation times measured by FISP–MRF in human brains were significantly lower compared with the results reported in previous studies which were all based on CPMG type spin-echo sequences; however, this difference needs further exploration.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Yutaka Kato, Kazushige Ichikawa, Kuniyasu Okudaira, Toshiaki Taoka, and Shinji Naganawa have no conflicts of interest; Hirokazu Kawaguchi, Katsutoshi Murata, Katsuya Maruyama, Gregor Koerzdoerfer, Josef Pfeuffer, and Mathias Nittka are employees of Siemens Healthcare.

References

- 1.West J, Aalto A, Tisell A, et al. Normal appearing and diffusely abnormal white matter in patients with multiple sclerosis assessed with quantitative MR. PLoS One 2014; 9:e95161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roebuck JR, Haker SJ, Mitsouras D, Rybicki FJ, Tempany CM, Mulkern RV. Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill imaging of prostate cancer: quantitative T2 values for cancer discrimination. Magn Reson Imaging 2009; 27:497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghugre NR, Ramanan V, Pop M, et al. Quantitative tracking of edema, hemorrhage, and microvascular obstruction in subacute myocardial infarction in a porcine model by MRI. Magn Reson Med 2011; 66:1129–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenlon HM, Tello R, deCarvalho VL, Yucel EK. Signal characteristics of focal liver lesions on double echo T2-weighted conventional spin echo MRI: observer performance versus quantitative measurements of T2 relaxation times. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2000; 24:204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papadopoulos K, Tozer DJ, Fisniku L, et al. TI-relaxation time changes over five years in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2010; 16:427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McSheehy PM, Weidensteiner C, Cannet C, et al. Quantified tumor T1 is a generic early-response imaging biomarker for chemotherapy reflecting cell viability. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16:212–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weidensteiner C, Allegrini PR, Sticker-Jantscheff M, Romanet V, Ferretti S, McSheehy PM. Tumour T1 changes in vivo are highly predictive of response to chemotherapy and reflect the number of viable tumour cells—a preclinical MR study in mice. BMC Cancer 2014; 14:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Look DC, Locker DR. Time saving in measurement of NMR and EPR relaxation times. Rev Sci Instrum 1970; 41:250–251. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Homer J, Beevers MS. Driven-equilibrium single-pulse observation of T1 relaxation. A reevaluation of a rapid “new” method for determining NMR spin-lattice relaxation times. J Magn Reson (1969) 1985; 63:287–297. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doneva M, Börnert P, Eggers H, Stehning C, Sénégas J, Mertins A. Compressed sensing reconstruction for magnetic resonance parameter mapping. Magn Reson Med 2010; 64:1114–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bieri O, Scheffler K, Welsch GH, Trattnig S, Mamisch TC, Ganter C. Quantitative mapping of T2 using partial spoiling. Magn Reson Med 2011; 66:410–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben-Eliezer N, Sodickson DK, Block KT. Rapid and accurate T2 mapping from multi-spin-echo data using Bloch-simulation-based reconstruction. Magn Reson Med 2015; 73:809–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilbert T, Sumpf TJ, Weiland E, et al. Accelerated T2 mapping combining parallel MRI and model-based reconstruction: GRAPPATINI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018; 48:359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warntjes JB, Leinhard OD, West J, Lundberg P. Rapid magnetic resonance quantification on the brain: optimization for clinical usage. Magn Reson Med 2008; 60:320–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmitt P, Griswold MA, Jakob PM, et al. Inversion recovery TrueFISP: quantification of T1, T2, and spin density. Magn Reson Med 2004; 51:661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warntjes JB, Dahlqvist O, Lundberg P. Novel method for rapid, simultaneous T1, , and proton density quantification. Magn Reson Med 2007; 57:528–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma D, Gulani V, Seiberlich N, et al. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Nature 2013; 495:187–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang Y, Ma D, Seiberlich N, Gulani V, Griswold MA. MR fingerprinting using fast imaging with steady state precession (FISP) with spiral readout. Magn Reson Med 2015; 74:1621–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rieger B, Zimmer F, Zapp J, Weingärtner S, Schad LR. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting using echo-planar imaging: joint quantification of T1 and relaxation times. Magn Reson Med 2017; 78:1724–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagiwara A, Hori M, Cohen-Adad J, et al. Linearity, bias, intrascanner repeatability, and interscanner reproducibility of quantitative multidynamic multiecho sequence for rapid simultaneous relaxometry at 3 T: a validation study with a standardized phantom and healthy controls. Invest Radiol 2019; 54:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krauss W, Gunnarsson M, Andersson T, Thunberg P. Accuracy and reproducibility of a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging method for concurrent measurements of tissue relaxation times and proton density. Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 33:584–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Y, Ma D, Keenan KE, Stupic KF, Gulani V, Griswold MA. Repeatability of magnetic resonance fingerprinting T1 and T2 estimates assessed using the ISMRM/NIST MRI system phantom. Magn Reson Med 2017; 78:1452–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badve C, Yu A, Rogers M, et al. Simultaneous T1 and T2 brain relaxometry in asymptomatic volunteers using magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Tomography 2015; 1:136–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Körzdörfer G, Kirsch R, Liu K, et al. Multicenter and multiscanner reproducibility of Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting relaxometry in the brain. Proceedings of the 26th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Paris, 2018;0798. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma D, Coppo S, Chen Y, et al. Slice profile and B1 corrections in 2D magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Magn Reson Med 2017; 78:1781–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer CH, Zhao L, Lustig M, et al. Dual-density and parallel spiral ASL for motion artifact reduction. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 2011; 19:3986. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Körzdörfer G, Pfeuffer J, Kluge T, et al. Effect of spiral undersampling patterns on FISP MRF parameter maps. Magn Reson Imaging 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2019.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Chung S, Kim D, Breton E, Axel L. Rapid mapping using a preconditioning RF pulse with TurboFLASH readout. Magn Reson Med 2010; 64:439–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGivney DF, Pierre E, Ma D, et al. SVD compression for magnetic resonance fingerprinting in the time domain. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2014; 33:2311–2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russek S. ISMRM/NIST MRI System Phantom. https://collaborate.nist.gov/mriphantoms/bin/view/MriPhantoms/MRISystemPhantom (Accessed May 29, 2018).

- 31.Keenan KE, Stupic KF, Boss MA, et al. Comparison of T1 measurement using ISMRM/NIST system phantom. Proceedings of the 24th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Singapore, 2016;3290. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bojorquez JZ, Bricq S, Acquitter C, Brunotte F, Walker PM, Lalande A. What are normal relaxation times of tissues at 3 T? Magn Reson Imaging 2017; 35:69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu H, Nagae-Poetscher LM, Golay X, Lin D, Pomper M, van Zijl PC. Routine clinical brain MRI sequences for use at 3.0 Tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging 2005; 22:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wansapura JP, Holland SK, Dunn RS, Ball WS. NMR relaxation times in the human brain at 3.0 tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging 1999; 9:531–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gelman N, Gorell JM, Barker PB, et al. MR imaging of human brain at 3.0 T: preliminary report on transverse relaxation rates and relation to estimated iron content. Radiology 1999; 210:759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raunig DL, McShane LM, Pennello G, et al. Quantitative imaging biomarkers: a review of statistical methods for technical performance assessment. Stat Methods Med Res 2015; 24:27–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y, Jiang Y, Pahwa S, et al. MR fingerprinting for rapid quantitative abdominal imaging. Radiology 2016; 279:278–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cloos MA, Knoll F, Zhao T, et al. Multiparametric imaging with heterogeneous radiofrequency fields. Nat Commun 2016; 7:12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Körzdörfer G, Jiang Y, Speier P, et al. Magnetic resonance field fingerprinting. Magn Reson Med 2019; 81:2347–2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buonincontri G, Sawiak SJ. MR fingerprinting with simultaneous B1 estimation. Magn Reson Med 2016; 76:1127–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu Z, Zhao T, Assländer J, Lattanzi R, Sodickson DK, Cloos MA. Exploring the sensitivity of magnetic resonance fingerprinting to motion. Magn Reson Imaging 2018; 54:241–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kobayashi Y, Terada Y. Diffusion-weighting caused by spoiler gradients in the fast imaging with steady-state precession sequence may lead to inaccurate T2 measurements in MR fingerprinting. Magn Reson Med Sci 2019; 18:96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Körzdörfer G, Guzek B, Jiang Y, et al. Description of the off-resonance dependency in slice-selective FISP MRF. Proceedings of the 26th Annual Meeting of ISMRS, Paris, 2018;4085. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang Y, Ma D, Wright K, Seiberlich N, Gulani V, Griswold MA. Simultaneous T1, T2, diffusion and proton density quantification with MR fingerprinting. Proceedings of the 22th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Milan, Italy, 2014;0028. [Google Scholar]