Abstract

The Saudi government is currently facing multiple challenges in achieving “The Gold Standard” in nursing practice. This is not limited to educational challenges, staffing shortage, paucity of international and national benchmark evidence, absence of clear and defined scope of nursing practice, and lack of appropriate policies and regulations. This study presented a comprehensive plan for developing a policy based on current challenges, recognition of policy goals, assessment of potential options and alternatives, identification of stakeholders, proposition of recommended solutions, and implementation of the framework to transform nursing standards and link these changes with the Saudi Vision 2030. However, amendments are required in the present strategic plan for the better management of the nursing profession. It is doubtful that the current nursing profession status quo is capable of meeting the golden standards for health care. Thus, the transformation of the nursing profession in Saudi Arabia is necessary.

Keywords: Health care, Nursing, Policies, Strategies, Transformation, 2030 Saudi vision

1. Introduction

Globally, nurses have made important contributions to a range of health priorities including universal health coverage, mental and community health, emergency preparedness and response, patient safety, and the provision of comprehensive patient-centered care (WHO, 2020). Without consistent and continuous efforts aimed at maximizing the contribution of nurses in their roles in interprofessional health teams, the national health agenda cannot be achieved. These efforts require policy interventions that empower nurses and optimize their scope of practice and promote their positive influences and effectiveness on the quality of delivered care, while accelerating development in nursing education, competencies, and skills.

Saudi Arabia takes up three-fourths of the Arabian Peninsula and has a population of approximately 34,000,000. According to Al-Dossary (Al-Dossary, 2018), Saudi Arabia has experienced an economic boom based on the unprecedented increase in oil prices from 2003 to 2013, which consequently has affected the lifestyle and health of Saudi individuals. In this context, the WHO (WHO, 2014) indicated that there has been an upsurge in life expectancy among the Saudi population from 69 years in 1990 to 76 years in 2012.

However, Saudi Arabia has entered a new era of progress and prosperity after developing Vision 2030—a program that contributes a series of developments in the fields of health delivery systems, nursing, trade, education, communications, science, and technology. One of the goals of Saudi Vision 2030 is improving the health delivery system to enhance community health status. In this regard, the provision of free healthcare services in Saudi Arabia is the responsibility of the Ministry of Health (MOH) at three care levels: primary, secondary, and tertiary (Al-Jazairi et al., 2011). Moreover, the government plays an essential role by offering varied levels of health services. In fact, the Saudi government has spent SR 484 billion from 2007 to 2016 in the healthcare sector to create 2,390 primary healthcare centers and 284 hospitals (Ministry of Health, 2018).

In Saudi Arabia, nurses make important contributions to the healthcare sector as healthcare providers. Moreover, it is predicted that the demand for nurses in Saudi Arabia will be more than doubled by 2030, as the annual population growth continues to increase at an annual rate of 2.52%. This shows that almost 150,000 nursing positions should have been filled by 2030. To meet this need without overseas recruitment, approximately 10,000 new nurses should graduate and be employed each year in Saudi Arabia. However, in juxtaposition with developed countries, Saudi Arabia faces extreme staffing shortages, socio-cultural challenges, paucity of international and national benchmark evidence, absence of clear and defined scope of nursing practice, and, most importantly, policies and regulations along with the ensuing repercussions on the quality of care being offered (Aboshaiqah, 2016, Al-Dossary et al., 2016). These hurdles inhibit the achievement of the “The Gold Standard” in nursing practice as promised by the Saudi government. Consequently, the nursing status quo contradicts the 2030 Saudi Vision regarding the enhancement of nursing working environment to retain and empower nurses.

To undertake such challenges, the success of delivering “The Gold Standard” in nursing depends on whether the Saudi government is vigilant, less centralized, smart, and sophisticated (Alalyani, 2011). In addition, nursing staff will have to be empowered to ensure appropriate decision-making in the right place at the right time. To this end, they need the authority to make choices, accept responsibility, and take action. Therefore, this policy paper puts forth its emphasis on several extractable themes associated with nursing transformation in order to spell out the underlying nursing objectives proposed in the 2030 Saudi Vision.

2. Background

In Islamic history, Rufaida Al-Asalmiya was the first woman to practice nursing. As a nursing educator and counterpart to Florence Nightingale, she offered nursing care to injured soldiers in primitive tribes throughout the initial Islamic period. In addition, she established a clinic for teaching nursing and offering nursing care to the community (Almalki et al., 2011). Eventually, in 1954, nursing was established as a profession according to the MOH. In addition, the collaboration between the WHO and the MOH in 1958 led to the establishment of the “Health Institute Program” for one-year in Riyadh (Almalki et al., 2011).

2.1. Nursing shortage

As global health systems creak under the strain of the coronavirus, it has been made clear that there are not enough nurses to meet global and national health needs. In Saudi Arabia, the current shortage of nurses has led to the creation of many loopholes in quality of offered care, and has developed an acute prerequisite for expatriate nurses to meet the healthcare needs and reduce the impact of nursing paucity that has arisen in MOH and other healthcare sectors. As shown in Table 1 , a total of 184,565 registered nurses are currently working in Saudi Arabia, which includes the private sector and other governmental agencies. In, 2018, Saudi nurses comprised 38.8% of the total nurses᾿ population (Ministry of Health, 2018). More specifically they constituted 59.4%, 17.6%, and 4.9% of the total nurses working in MOH, other governmental hospitals, and the private sector, respectively. In addition, a ratio of 55.2 nurses per 10,000 individuals is represented in the population of Saudi Arabia, with an escalation of 48% from 2012 to 2018.

Table 1.

Key Indicators (Ministry of Health, 2018).

| Ministry of Health | ||

| Nurses including Midwives | 105,473 nurses | |

| Percentage of Saudi nurses | 59.4% | |

| Other Governmental Sectors | ||

| Nurses including Midwives | 35,697 nurses | |

| Percentage of Saudi nurses | 17.6% | |

| Private Sectors | ||

| Nurses including Midwives | 43,395 nurses | |

| Nurses including Midwives | 4.9% | |

| Total | ||

| Nurses including Midwives | 184,565 nurses | |

| Percentage of Saudi nurses | 38.8% | |

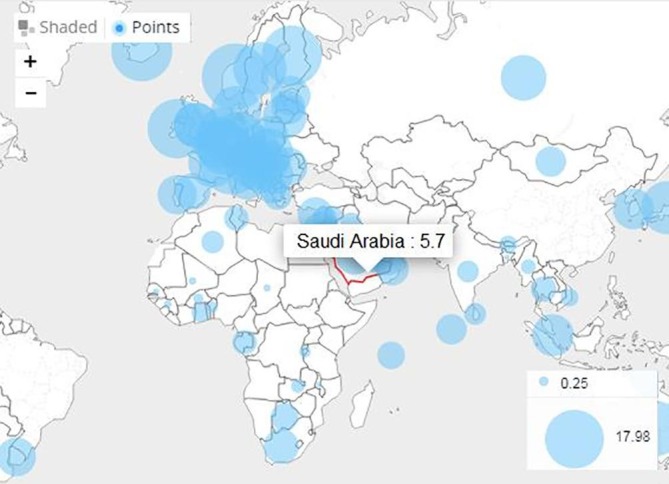

Fig. 1 shows recent statistics published by the World Bank (The World Bank, 2019) in 2019, in which there are 5.7 Saudi nurses per 1,000 individuals in the population, with an increase of 17.98% from 2016 to 2019. To provide more context, Saudi Arabia has the second highest ratio of nurses after Qatar (74/10,000) as compared to, Jordan, Bahrain, and UAE that have lower nurse populations (Khoja et al., 2017). When compared globally, the ratio of nurses in Saudi Arabia is still low as compared to France (93/10,000), the United Kingdom (95/10,000), USA (98/10,000), and Canada (105/10,000) (WHO, 2020, WHO, 2014).

Fig. 1.

Nurses and Midwives per 1000 people (The World Bank, 2019).

However, besides the low ratio of nurses in Saudi Arabia, the sole reliance on the recruitment of expatriate nurses resulted in various challenges, including an escalated burden on the economy and unstable health care.

2.2. Nursing education programs

In Saudi Arabia, nursing programs have had poor enrolment rates due to the bad reputation of the nursing profession across the community (AlYami and Watson, 2014, Saied et al., 2016). This bad reputation was stimulated by mixed working environments, cultural reasons, the role of family, and varied working conditions, including night shifts specifically for female nurses (AlYami and Watson, 2014). However, the low enrolment rates have been addressed inequitably by the Ministry of Education (MOE) by establishing enrolment in nursing programs that are open-access for students who were rejected from other health professions due to a low GPA. Consequently, the graduation of competent nurses from Saudi universities is doubtful.

2.3. Centralized management

As the MOH is a leading government agency, its responsibility is to regulate, plan, finance, and manage the healthcare sector via the Council of Health Services (Alkhamis, 2012). A Royal Decree in 2002 established the Council of Health Services, which was headed by the minister of MOH. The Council includes private health sectors and representatives from other governmental sectors. Therefore, according to Almalki, FitzGerald, and Clark (Almalki et al., 2011), the MOH is reflected as a National Health Service (NHS) for the overall population. However, no substantial improvement has been made in terms of these platforms and initiatives (Alshammari et al., 2019). Significant delays in decisions, less innovative ideas, and resistance to change from the front-line level were led by such a centralized system where the majority of the decisions were made by a small chain of stakeholders (Shanker et al., 2017, El-Demerdash and Mostafa, 2018). This prevented the introduction of new concepts and methods to improve the provision of health care in MOH hospitals and other private hospitals.

Moreover, during the last decade, the MOH has become less centralized in order to manage healthcare services by operating independent health care clusters with autonomous budgets. Nonetheless, there are still many decisions—such as regulation, legislation, planning, and investment—that are controlled by the top-level management of the MOH (El-Demerdash and Mostafa, 2018). In addition, although the hospital managers and regional directors of health services have greater supervisory roles and responsibilities, they were left with minimal authority. Most importantly, shared governance was identified by nursing professionals as a fundamental determinant of excellence in the nursing profession; thus, it is clear that conventional centralized management does not collaborate with them in order to attract and retain their strategies (McClarigan et al., 2019, Hess, 2017). However, most obstacles have been formed due to the hierarchical structures of decision-making, which include employee empowerment and autonomy, that hinder quality of care and develop a lack of trust between employees and managers (Palatnik, 2016).

2.4. Professional body

At the national level in Saudi Arabia, there is no nursing council or professional body with established responsibilities and accountabilities for governing nursing practice and providing professional autonomy such as a nursing code of ethics and nursing practice (Lovering, 2013). In this context, at the MOH, the general administration of nursing (GAON) is responsible for assorted roles, scopes, and responsibilities for nurses (Hibbert et al., 2017). It also establishes regulations and legislation; therefore, it is a professional institution that oversees the entire nursing community.

In 2002, the Scientific Nursing Board (SNB) was established and operated under the authority of the Saudi Commission for Healthcare Specialties (SCFHS). The objectives defined by the SNB involved the formulation of criteria for professional practice; the assessment of hospitals and health centers for the objective of education; the development of ethical, practical, and educational competency standards; and the development of credentialing procedures (Abu-Zinadah, 2006). The SNB plays a major role in evaluating and equalizing professional certificates as a licensing board and a registration authority. Thus, a national regulatory body is needed in the nursing profession in Saudi Arabia for developing policies as well as enforcing the rules and laws of nursing practices. However, on the contrary, the establishment of a nursing body has still not been defined in Saudi Arabia for the sake of ruling and regulating the nursing discipline. Thus, it is important for nursing leaders in healthcare agencies, particularly in the MOH, to establish the context of nursing care by formulating a professional body that stimulates the realm of nursing in the absence of a regulatory body.

2.5. Absence of clear and defined scope of nursing practice

The scope of nursing practice is defined as the range of roles, functions, responsibilities, and activities that qualified registered nurses are authorized to perform (Guido, 2014). It reflects all the roles and activities undertaken by registered nurses to address the full range of human experiences and responses to health and illness. It is well-founded to state that the absence of a clear scope in nursing practice increases the workload on nurses and allows the wastage of significant amounts of time on activities that do not enhance patient care, such as housekeeping and secretarial tasks. (Furåker, 2009) In recent years, the nursing board has begun focusing on standardizing nursing practice in SCHS, but the scope of nursing practice has not yet been formalized (Al‐Dossary, 2018). Therefore, a major challenge has been presented by the restrictions on enacted scope of practice in managing nursing services to maximize the utilization of nurses’ skill sets. Nevertheless, it must be noted that regardless of a clear standard scope of nursing practice, nurse educators will still experience several issues in clinical practice, and there will be challenges in developing staff educational plans.

3. Policy goals and objectives

-

•

Enhancing the attractiveness and reputation of the nursing working environment

-

•

Enhancing the retention of qualified nurses

-

•

Establishing a national benchmark database in existing Magnet hospitals with the current nursing practice for comparing clinical, organizational, and nursing outcomes with quality indicators

-

•

Formulating the nursing scope of practice

3.1. Policy options

Adequate understanding about the policy development process is required while studying policy-making in health care systems to highlight its impact on the framed health objectives (Alsufyani, 2020). In addition, the process of policy development needs to be negotiable between stakeholders.

3.2. Stakeholders

3.2.1. Primary stakeholders

Nurses in healthcare settings, the MOH, Magnet hospitals, nursing professionals, midwives, nurse educators, practitioners, nursing managers, health accreditation institutions, sponsors as well as representatives from the Saudi parliament, other government agencies and private sectors are considered primary stakeholders.

3.2.2. Secondary stakeholders

Visitors, clients, patients, families of patients, families of nurses and midwives, and families of nursing managers are considered secondary stakeholders as are citizens living in Saudi Arabia who will benefit from having and supporting this policy that augments the level of quality care.

4. Methods

4.1. Policy options and alternatives

-

▪

Option 1 is to do nothing or stay in the same condition, which means that no changes will be made on the existing policy.

-

▪

Option 2 is to make an incremental change on the existing policy to make it applicable to transform nursing standards and direct it based on the 2030 Saudi Vision.

-

▪

Option 3 is to make a comprehensive and significant change, or derive a new policy from scratch based on the 2030 Saudi Vision.

4.2. Assessment of policy options and alternatives

After listing three policy options aiming to facilitate nursing transformation in Saudi Arabia, it is necessary to narrow down the options to identify the most applicable policy option for politicians and decision-makers by establishing evaluation criteria.

4.2.1. Establishing evaluation criteria

A total of five features were considered while comparing the policy alternatives including, social acceptability, political feasibility, fairness, cost, and contribution. The selection of these features was based on the appropriateness in conducting health policy analysis for turning ideas into actions (Engelman et al., 2019, Collins, 2005). Amongst these features, the contribution of policy is the most essential feature to achieve the preferred objectives, specifically to transform nursing standards and practices. Other important features include the cost of applying changes and political feasibility. Furthermore, fairness in distribution of advantages is also essential. Lastly, social acceptability is the feature that defines, based on evidence, the extent to which the proposed change becomes acceptable and popular among primary and secondary stakeholders.

4.2.2. Analysis and comparison of policy alternatives

Option 1 restricts making changes or prefers to continue functioning with the current strategies and policies. Although, this option is politically feasible with the same cost, it contradicts the Saudi Arabian 2030 vision regarding retaining and empowering nurses. Meanwhile, the pressure on nursing staff will be the same as observed in recent cases; thus, it is an inequitable option.

Option 2 introduces an incremental change to the existing policy. This will accomplish the 2030 Saudi Vision. In addition, it will be politically and economically feasible. Furthermore, it will be socially accepted as it is designed to enhance the quality of healthcare.

Option 3 indicates a comprehensive change or the changing of the policy from scratch. This entails the removal of the existing policy and the establishment of a new policy. Although this option will accomplish the 2030 Saudi Vision, it will be politically and economically infeasible as it includes major changes. However, it will be considered fair by the stakeholders and socially accepted.

5. Results

5.1. Recommended solution

As shown in Table 2 , the recommended option for making policy changes is Option 2. The changes made in the policy as per this option will ensure that the 2030 Saudi Vision remains active and focused on nursing demands. Further, Option 2 will help hospitals that have Magnet recognition in their strategic plans as the loopholes in the nursing work environment can be distinguished when nurses possess a high satisfaction level, low turnover rate retention, healthy organizational climate, educational development at every career stage, and autonomous nursing care—which will be accomplished using Option 2.

Table 2.

Policy options evaluation scorecard.

| Option 1 | Option 2 | Option 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contribution | – | √ | √ |

| Political Feasibility | √ | √ | – |

| Fairness | – | √ | √ |

| Social Acceptability | – | √ | √ |

| Cost | √ | √ | – |

| Total | 2 | 5 | 3 |

6. Discussion

6.1. Nursing shortage

The chronic shortage in nursing with respect to facilities and technologies has been further exacerbated by the rapid growth in the Saudi population, healthcare systems, and changing healthcare needs. In terms of nursing manpower, stability and retention can be addressed with benefits like opportunities for administrative and promotion tasks, reduced workload, flexible schedules, and bonuses (Alboliteeh et al., 2017). For female nurses, the most useful aspect could be the introduction of flexible working hours and reduction in working hours, as 80% of the nursing workforce is female (Ministry of Health, 2018). In addition, nursing colleges and the MOH can collaborate to start enrolment programs in nursing colleges and ensure employment after graduation. This marketing plan may attract high school students (Alroqi, 2017). Thus, the critical issue of nursing shortage can be addressed through nursing practice, research, and education.

6.2. Nursing management

There is a need for establishing a national benchmark database in existing Magnet hospitals with the current nursing practice to compare clinical, organizational, and nursing outcomes with quality indicators (Stimpfel et al., 2014). It appears timely for nursing management to evaluate the effect of the Magnet Recognition Program—in which workplace environments, nurse satisfaction and shortage, and patient care quality and safety are evaluated—on the elected hospitals as well as demonstrate whether it can assist in reducing the professional constraints associated with autonomy, retention, and nursing shortage (Rondeau and Wagar, 2006, Armstrong and Laschinger, 2006).

Moreover, it has been observed that the nursing shortage can be improved by Magnet hospitals with the provision of opportunities that affect the healthcare structure and enhance professional relationships (Hess, 2017). Different hospitals have used the Magnet Recognition Program throughout cultural, political, economic, and clinical settings (Walker and Aguilera, 2013). Thereby, the existence of two Magnet hospitals can give nursing managers the opportunity to identify the effects of Magnet designation on patient outcomes and nursing practice in Saudi Arabia.

6.3. Nursing education

It has been observed that specific changes are required to mitigate the acute shortage of nurses with respect to nursing education. In this regard, increasing the number of nursing scholarships and programs can address the nursing shortage. Further, it is a significant responsibility of nurse educators to enhance the attractiveness and good reputation of nursing as a profession, and to meet the demands of the country in order to overcome the burden of the shortage. In addition, the assurance of a high-quality curriculum should be the priority of Saudi nursing colleges. They should also adopt problem-based learning and self-directed learning approaches, and remove the traditional spoon-feeding teaching strategies (Alsufyani et al., 2019). On the other hand, nurse leaders and educators should develop campaigns to correct inaccurate stereotypes and long-standing myths, emphasizing the significance of nurses’ responsibilities on the interdisciplinary healthcare team, and consequently, enhancing the image of the nursing profession. Such campaigns can increase public knowledge and awareness of the nursing profession (Alboliteeh et al., 2017, Hassan, 2017).

6.4. Scope of nursing practice

There is a need to develop national guidelines for the scope of nursing. A well-defined scope of nursing practice explains general nursing functions, work-related procedures with other healthcare professionals, and tasks and responsibilities either collaboratively or independently. In addition, it is mandatory to elect and manage adequate restrictions in nurse-client relationships to facilitate therapeutic and safe practice. However, these boundaries further should account for different cultures with varied understanding and anticipations of boundaries and relationships.

Moreover, the nursing profession can benefit from implementing successful international examples in the Saudi Arabian healthcare system to improve this situation. For instance, the Nursing and Midwifery Board in Australia, the Nursing Midwifery Council (NMC), and the American Nurses Association (ANA) in the United States all provide guidelines and standards of education or codes, training, and practice in their respective countries. These organizations assist in protecting the public by assuring ethical and safe nursing practices and ensuring that nurses are adequately educated and trained for their roles. Thus, SCHS is required to draw from the 2030 Saudi Arabia Vision to imitate these international models by establishing an autonomous regulatory council or nursing body and formulating a clear scope of nursing practice based on nurses᾿ knowledge, skills, and judgments.

However, it is worth noting that varied implications might be derived from this policy evaluation for nursing education, policymakers, and administration of the Saudi nursing profession and the mission towards which it is inclined with respect to the 2030 Saudi Vision.

7. Conclusion

The Saudi Vision 2030 calls for unifying the efforts of nursing leaders, educators, and practitioners toward nursing transformation. Nursing transformation requires improving the quality of delivered care, a stronger education foundation, establishing an autonomous regulatory council, formulating a clear scope of nursing practice based on nurses᾿ knowledge and skills, and reducing professional constraints and centralization of the management. The core focus of current policy assessment is on the accomplishment of nursing transformation. In this context, nursing policies and strategies must be continuously monitored for ensuring its consistency with nursing transformation.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This research is not funded by any resource.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abdulaziz M. Alsufyani: Conceptualization, Project administration, Literature review. Mohammed A. Alforihidi: Methodology, Resources. Khalid E. Almalki: Validation of resources. Sayer M. Aljuaid: Writing – First Draft Preparation, Writing – Second Draft Preparation. Ayman A. Alamri: Resources, Writing - review & editing, Writing – Final Draft. Mussad S. Alghamdi: Supervision, English Editing, References Editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The author is very thankful to all the associated personnel in any reference that contributed in/for the purpose of this research.

References

- Al-Dossary R.N. The Saudi Arabian 2030 vision and the nursing profession: The way forward. International Nursing Review. 2018;65(4):484–490. doi: 10.1111/inr.12458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jazairi A.S., Al-Qadheeb N.S., Ajlan A. Pharmacoeconomic analysis in Saudi Arabia: An overdue agenda item for action. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(4):335–341. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.83201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboshaiqah A. Strategies to address the nursing shortage in Saudi Arabia. International Nursing Review. 2016;63(3):499–506. doi: 10.1111/inr.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dossary R.N., Kitsantas P., Maddox P.J. Clinical decision-making among new graduate nurses attending residency programs in Saudi Arabia. Applied Nursing Research. 2016;29:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alalyani M.M. Curtin University; Perth: 2011. Factors influencing the quality of nursing care in an intensive care unit in Saudi Arabia [doctoral dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- Almalki M., FitzGerald G., Clark M. The nursing profession in Saudi Arabia: An overview. International Nursing Review. 2011;58(3):304–311. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.10.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. Nurses and midwives (per 1,000 people) – Saudi Arabia. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.NUMW.P3?locations=SA/; 2019 [accessed 01 July 2020].

- Khoja T., Rawaf S., Qidwai W., Rawaf D., Nanji K., Hamad A. Health care in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: A review of challenges and opportunities. Cureus. 2017;9(8) doi: 10.7759/cureus.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AlYami M.S., Watson R. An overview of nursing in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Health Specialties. 2014;2:10. doi: 10.4103/1658-600X.126058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saied H.I., Al Beshi H., Al Nafaie J., Al A.E. Saudi community perception of nursing as a profession. Journal of Nursing and Health Science. 2016;5(2):95–99. doi: 10.4172/2167-1168.C1.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhamis A. Health care system in Saudi Arabia: An overview. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2012;17(10):784–793. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.83201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshammari M., Duff J., Guilhermino M. Barriers to nurse–patient communication in Saudi Arabia: An integrative review. BMC Nursing. 2019;18:61. doi: 10.1186/s12912-019-0385-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanker R., Bhanugopan R., Van der Heijden B.I., Farrell M. Organizational climate for innovation and organizational performance: The mediating effect of innovative work behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2017;100:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Demerdash S.M., Mostafa W. Association between organizational climate and head nurses’ administrative creativity. IJND. 2018;8(1):1–9. doi: 10.15520/ijnd.2018.vol8.iss01.268.01-09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McClarigan L., Mader D., Skiff C. Yes, we can and did: Engaging and empowering nurses through shared governance in a rural health care setting. Nurse Leader. 2019;17(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mnl.2018.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hess R.G. Professional governance: Another new concept? Journal of Nursing Administration. 2017;47(1):1–2. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palatnik A. The future of nursing. Nursing in Critical Care. 2016;11(3):4. doi: 10.1097/01.ccn.0000482518.50906.58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering S. Magnet® designation in Saudi Arabia: Bridging cultures for nursing excellence. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2013;43(12):619–620. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert D., Aboshaiqah A.E., Sienko K.A., Forestell D., Harb W.A., Yousuf S.A. Advancing nursing practice: The emergence of the role of advanced practice nurse in Saudi Arabia. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 2017;37(1):72–78. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2017.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Zinadah S. Saudi Nursing Board, Saudi Commission for Health Specialties; Riyadh: 2006. Nursing situation in Saudi Arabia. [Google Scholar]

- Guido G.W. Pearson; Boston: 2014. Legal and ethical issues in nursing. [Google Scholar]

- Furåker C. Nurses' everyday activities in hospital care. Journal of Nursing Management. 2009;17:269–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2007.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsufyani A.M. Role of theory and research in policy development in health care system. American Journal of Public Health Research. 2020;8(2):61–66. doi: 10.12691/ajphr-8-2-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman A., Case B., Meeks L., Fetters M.D. Conducting health policy analysis in primary care research: Turning clinical ideas into action. FMCH. 2019;7(2) doi: 10.1136/fmch-2018-000076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins T. Health policy analysis: A simple tool for policy makers. Public Health. 2005;119(3):192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alboliteeh M., Magarey J., Wiechula R. The profile of Saudi nursing workforce: A cross-sectional study. Nursing Research and Practice. 2017;2017(4):1–9. doi: 10.1155/2017/1710686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alroqi H.M. Anglia Ruskin University; Cambridge: 2017. Perceptions of the community toward the nursing profession and its impact on the local nursing workforce shortage in Riyadh [doctoral dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- Stimpfel A.W., Rosen J.E., McHugh M.D. Understanding the role of the professional practice environment on quality of care in Magnet® and non-Magnet hospitals. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2014;44(1):10–16. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondeau K.V., Wagar T.H. Nurse and resident satisfaction in magnet long-term care organizations: Do high involvement approaches matter? Journal of Nursing Management. 2006;14(3):244–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K.J., Laschinger H. Structural empowerment, Magnet hospital characteristics, and patient safety culture: Making the link. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2006;21(2):124–132. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200604000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess R.G., Jr. Professional governance: Another new concept? The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2017;47:1–2. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker K., Aguilera J. The international Magnet® journey. Nursing Management. 2013;44(10):50–52. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000434600.60977.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsufyani A.M., Aboshaiqah A.E., Moussa M.L., Baker O.G., Almalki K.E. Competence of nurses relating self-directed learning in Saudi Arabia: A meta-analysis. Global Journal of Health Science. 2019;11(9):145–152. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v11n9p145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M.M. Strategies of improving the nursing practice in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Health Education Research & Development. 2017;5(2) doi: 10.4172/2380-5439.1000221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, (2014). World health statistics 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112738/9789240692671_eng.pdf;jsessionid=4D02D575F42441F6520924D538BA82A8?sequence=1 [accessed 10 March 2020].

- WHO, (2020). State of the world᾿s nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs and leadership. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279 [accessed 01 July 2020].

- Ministry of Health, (2018). Statistical yearbook. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Pages/default.aspx/ [accessed 01 July 2020].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.