Abstract

Pluto is covered by numerous deposits of methane, either diluted in nitrogen or as methane-rich ice. Within the dark equatorial region of Cthulhu, bright frost containing methane is observed coating crater rims and walls as well as mountain tops, providing spectacular resemblance to terrestrial snow-capped mountain chains. However, the origin of these deposits remained enigmatic. Here we report that they are composed of methane-rich ice. We use high-resolution numerical simulations of Pluto’s climate to show that the processes forming them are likely to be completely different to those forming high-altitude snowpack on Earth. The methane deposits may not result from adiabatic cooling in upwardly moving air like on our planet, but from a circulation-induced enrichment of gaseous methane a few kilometres above Pluto’s plains that favours methane condensation at mountain summits. This process could have shaped other methane reservoirs on Pluto and help explain the appearance of the bladed terrain of Tartarus Dorsa.

Subject terms: Asteroids, comets and Kuiper belt; Atmospheric dynamics

Pluto is covered by numerous deposits of methane. Here, the authors show that the formation of methane frost on mountain tops and crater rims in Pluto’s equatorial regions completely differ from those forming snow-capped mountains on Earth.

Introduction

An important observation of Pluto made by the New Horizons spacecraft in July 2015 was the great geomorphological diversity and albedo contrast of terrains in its equatorial regions1–6. In particular, west of Sputnik Planitia, the region of Cthulhu is characterized by a spectacular dark mantling that has been interpreted as an accumulation of haze particles that have settled from the atmosphere7, or in some locations a cryovolcanic deposit8.

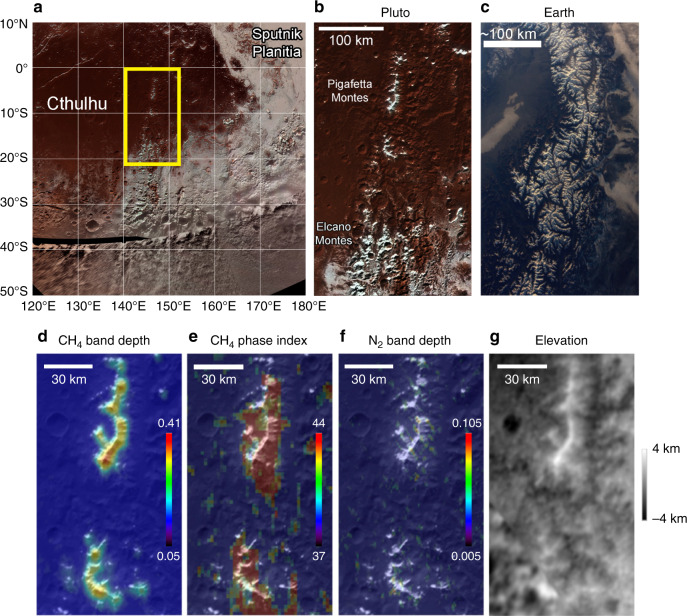

Although most of Cthulhu’s surface appears volatile-free3, the Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) instrument onboard New Horizons revealed the presence of patchy bright deposits at specific locations6 and the Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera (MVIC) showed that they contain methane (CH4)2. Figure 1a, b shows a part of eastern Cthulhu containing isolated high-altitude mountain chains, known as Pigafetta Montes, the crests of which reach 2.5–3.5 km above their bases and almost 4 km above mean radius9. They are capped with bright frosts (with an albedo of ~0.6510) above 1.5 km altitude with a striking resemblance to terrestrial alpine landscapes (Fig. 1c). MVIC showed that these frosts contain CH4 but could not conclude on its state (CH4-rich ice, CH4 diluted in N2-rich ice or both)2,11.

Fig. 1. Detection of CH4-rich ice on top of Pigafetta and Elcano Montes.

a New Horizons map of the southeast Cthulhu region on Pluto, located in the equatorial regions west of Sputnik Planitia. Yellow box indicates the boundaries of the area seen in detail in (b). b Detail of the CH4 frost-capped ridges of Pigafetta and Elcano Montes within Cthulhu Macula (148.2°E, 10.1°S), seen in an enhanced Ralph/MVIC colour image (680 m/pixel, cylindrical projection). c Satellite view of water ice-capped mountain chains in the Alps. d LEISA CH4 band depth map focusing on the Pigafetta Montes within Cthulhu, superimposed on the visible map, with blue-to-red indicating increasing CH4 absorption. e CH4 phase index map (at ~3× lower spatial resolution, see definition in ‘Methods’, Phase index maps), with red corresponding to CH4-rich ice and green-blue to N2-rich ice containing CH4. Yellow corresponds to some mixture of both phases. The high value of the CH4-phase index likely indicates that only the CH4-rich phase is present. f Same as (d) for the N2 band depth map. g New Horizons elevation map. Lateral resolution of the topography data at Pigafetta Montes is ~2.5 km, with a vertical precision of 230 m11.

Why does CH4 ice form on top of these mountains? It has been suggested that the sublimation and condensation of volatile ices could drive the ices out of thermodynamic equilibrium and result in altitude segregation with N2-rich ice dominating at low-elevations and CH4-rich ice dominating at high elevations12,13. Here we explore an alternative scenario that involves an atmospheric process. On Earth, atmospheric temperatures decrease with altitude, mostly because of adiabatic cooling and warming in upward and downward air motions, respectively. As a consequence, surface temperatures also decrease with altitude because the surface is cooled by the dense atmosphere through sensible heat fluxes. In such conditions, as moist wind approaches a mountain, it rises upslope and cools adiabatically, leading to condensation and formation of snow on top of mountains. Note that here frost is defined as ice crystals that form directly on a below-freezing surface via a phase change from gas in the atmosphere, whereas snow is defined as individual ice crystals that grow while suspended in the atmosphere and subsequently fall as precipitation onto the surface.

Could this process apply to Pluto too? Both observations and modelling show that, unlike on Earth, there is a strong increase in atmospheric temperatures with altitude in the first kilometres above the surface14,15 because of the heating resulting from the absorption of solar radiation by CH4 gas (except when N2 ice is present on the surface, because local N2 ice sublimation can cool the lowermost few kilometres of the atmosphere14,15). The atmosphere is too thin to affect the surface temperature itself and in the absence of N2 ice, the surface remains in local radiative balance everywhere, independent of the altitude and colder than the atmosphere above. One consequence of this is that the near-surface air is cooled and tends to flow downslope because it is denser than the air away from the slope at the same level. Climate simulations confirm this trend and indicate that these katabatic downslope near-surface winds dominate everywhere and at all times of day on Pluto14. Under such conditions, it is impossible to explain the condensation of CH4 by upward air motion as on the Earth, and a different mechanism must be identified.

Here we demonstrate that the bright frosts observed in Cthulhu are mostly made of CH4-rich ice. We then use a numerical climate model of Pluto to investigate the origin of their formation. Our simulations reproduce the accumulation high-altitude CH4 ice where the frost-capped mountains are observed, in particular on the ridges and crests of the Pigafetta and Elcano Montes in eastern Cthulhu. They show that CH4 condensation is favoured by sublimation-induced circulation cells that seasonally enrich the atmosphere with gaseous methane at those higher altitudes.

Results

Detection of CH4-rich ice on the top of the mountain chains

Figure 1d–g shows CH4 and nitrogen (N2) band depth and CH4-phase index maps3 derived from the highest spatial resolution spectral-image of the Linear Etalon Imaging Spectral Array (LEISA) instrument, presented alongside the latest digital elevation model9. These maps indicate that the bright frosts on the top of the mountain chain are mostly composed of CH4-rich ice. Only a few very small N2-rich ice patches occur in this area, mostly located at the bases of these mountains and in the valleys separating them.

Another geographical context where CH4 ice was detected was on north-facing walls and rims of many craters in Cthulhu, including Edgeworth Crater and many smaller examples surrounding Pigafetta Montes. The composition and phase maps also show that these deposits are CH4-rich ice3. We can straightforwardly explain this behaviour by calculating that these slopes received less insolation than the south-facing slopes during the previous northern fall and winter (see Supplementary Figs. 8, 9). They could thus have acted as cold traps for CH4 ice.

Numerical climate simulations of Pluto

Here, we use the Pluto Global Climate Model (GCM) of the Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique (LMD), designed to simulate the climate and CH4 cycle on Pluto14,16 (see ‘Methods’, The LMD Pluto GCM). It includes a full description of the volatile exchange between surface ice and atmospheric gas (for N2, CH4 and CO), transport and turbulent mixing of gaseous CH4 in the atmosphere and an implicit scheme for the formation of CH4 clouds. The radiative effect of CH4 and CO is also included14. The model provides an evolution of surface pressure and of the CH4 and CO mixing ratio in good agreement with New Horizons and terrestrial observations14,17. In the model, we rely on Raoult’s law as a substitute for the ternary equation of state. We consider that CH4-rich ice behaves like pure CH4 and that N2-rich ice contains 0.5% of CH4 (see ‘Methods’, CH4 and CO condensation–sublimation on the surface). We note that this approximation can lead to some uncertainties in CH4 solid-phase stability but that it remains a reasonable approach for the focus of this paper (CH4-rich deposits) and does not qualitatively change the results of this paper.

To simulate Pluto as observed in 2015, we performed a simulation similar to the one presented in Bertrand et al.16 but with the following improvements. Firstly, we used the latest topography data of the encounter hemisphere of Pluto9, which includes Sputnik Planitia, eastern Cthulhu, and Tartarus Dorsa (the latter being the western extent of the bladed terrain, a chain of massive, low-latitude, high-elevation deposits of CH4 ice that have been eroded via sublimation into the eponymous blades, and which extend across much of the sub-Charon side of Pluto11,18). Secondly, perennial CH4 deposits were added on the sub-Charon side of Pluto (covered by low-resolution New Horizons imaging) wherever terrain with diagnostic characteristics of the bladed terrain was detected18 (i.e. intermediate albedo in LORRI approach imaging, strong CH4 spectral signature in MVIC imaging, high elevation in far side limb profiles). Thirdly the initial state of the simulation was obtained for Earth year 1984 from a 30-million-year simulation performed with the Pluto volatile transport model19,20 (see ‘Methods’, Initial state of the reference simulation and grid resolution), thus allowing a steady state for ice distribution, surface and soil temperatures to be reached. We used two horizontal resolutions: a baseline resolution of 7.5° in latitude, 11.25° in longitude (i.e. ~150 km) for the years 1984–2014 and a higher resolution of 2.5° in latitude and 3.75° in longitude (i.e. ~50 km) for the years 2014–2015. This allowed us to better represent the atmosphere-topographic interactions during the New Horizons encounter.

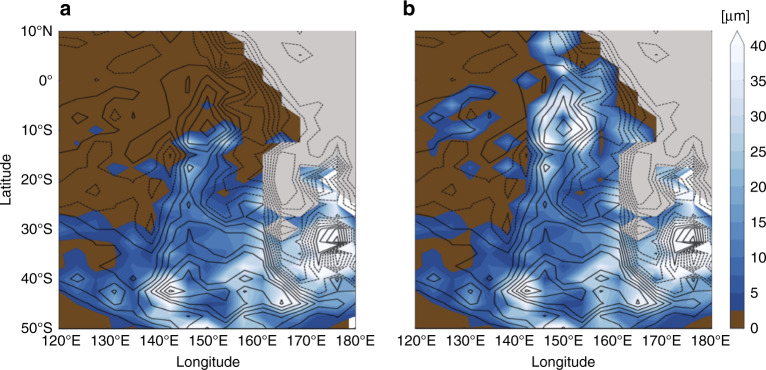

Net diurnal CH4 deposition in Cthulhu in 2015

In our simulation, the CH4 atmospheric mixing ratio reaches 0.4–0.7% in 2015, with slightly higher values in the northern hemisphere due to increasing CH4 ice sublimation from the mid-to-high northern latitude plains, as predicted by previous climate simulations14. A net CH4 ice deposition of ~20 μm over the year 2015 is obtained locally in Cthulhu, at the summits and on the flanks of the highest mountains of Pigafetta and Elcano Montes, in qualitative agreement with New Horizons observations (Fig. 2a). In this first simulation, CH4 ice affects the surface albedo by increasing it from 0.1 (volatile-free, or deposits thinner than 1 μm) to 0.5 (roughly the albedo of the CH4-rich bladed terrain, for deposits thicker than 1 μm). However, on Pluto, it is likely that once a fresh initial CH4 frost grows to a few millimetres, the surface albedo increases to values even higher than 0.5, inducing a stronger cooling (reduced solar heating) of the surface and allowing more CH4 to condense there. This positive feedback should favour even stronger katabatic winds and the accumulation of more ice on top of Pluto’s mountains. To explore its effect, we performed a second simulation in which the CH4 ice–albedo was slowly increased up to 0.9 as soon as the ice thickness reached more than 1 µm (see ‘Methods’, Surface albedo feedback for equatorial CH4 ice). In this second simulation, the modelled CH4 condensation rates are stronger than in the first, in particular in the diurnal zone above ∼20°S with a net CH4 ice deposition over the year 2015 of ~40 μm and on top of Pigafetta Montes and a better agreement with New Horizons observations (Fig. 2b). By extrapolating over the last 27 Earth years (beginning of northern spring), such an accumulation would have covered the tops of these mountains with a ~1-mm-thick CH4 ice deposit. However, the frosts could have started forming during northern fall or winter and accumulated to thicknesses much >1 mm. It may also be possible that they grew thicker (up to a few metres) over multi-annual timescales, during past climate epochs with larger amounts of gaseous CH4 available for condensation20. The lack of image resolution, the uncertainties on the starting season of the frosts and the model approximations for computing CH4 condensation and sublimation rates (see ‘Methods’, CH4 and CO condensation–sublimation on the surface) prevent us for estimating the thickness of CH4-rich deposits with great confidence. Nevertheless, the 2015 simulation sheds light on the possible processes forming the CH4-rich deposits seen at mountain summits in eastern Cthulhu.

Fig. 2. Modelled deposition of CH4 ice in eastern Cthulhu.

a Net surface CH4 ice accumulation (from blue to white) in Cthulhu (covering the same area as in Fig. 1a) obtained in our simulation for 2015. Superimposed topography contours are at 300-m intervals. The volatile-free surface is shaded in brown, the Sputnik Planitia N2 ice sheet is shaded in grey. b The same as (a) but using an amplifying albedo feedback for CH4 ice (see ‘Methods’, Surface albedo feedback for equatorial CH4 ice). The albedo feedback has no effect below ∼20°S because these latitudes receive little to no insolation (polar night) in 2015.

What drives the formation of high-altitude CH4-rich frosts?

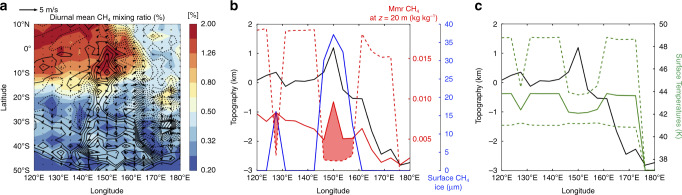

Condensation on the surface occurs when the near-surface atmospheric CH4 mixing ratio is greater than the CH4 mixing ratio at saturation (see ‘Methods’, CH4 and CO condensation–sublimation on the surface). As mentioned above, on a N2-free surface such as in Cthulhu, there is no dependence of surface temperature on altitude (Supplementary Fig. 1a, c). The CH4 mixing ratio at saturation, which depends only on surface temperature, is therefore independent of altitude and should be relatively constant for given surface properties and insolation. Our model indicates that despite their very low albedo (∼0.1), the equatorial regions in Cthulhu in 2014–2015 are cold enough during night-time (~40–42 K) to trigger CH4 condensation onto the surface and the formation of μm-thin CH4 frosts (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). In the model, these frosts then entirely sublime during daytime, when the surface heats up to ∼45–48 K (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 1c, d), except over high-altitude terrains, where the night-time condensation dominates the daytime sublimation (Supplementary Fig. 2), allowing the frosts to subsist and grow thicker. We determine from the analysis of our results that this is because the near-surface atmospheric CH4 mixing ratio in the model strongly varies with altitude in the equatorial regions, with an enrichment in gaseous CH4 above ~4 km altitude (above mean radius, Supplementary Fig. 3) and a depletion in the lowest levels of the atmosphere. This vertical distribution of gaseous CH4 in the first kilometres above the surface forms self-consistently as an outcome of our GCM simulation but remains unconstrained by observations as the CH4 mixing ratio was not observed by New Horizons below 80 km altitude. As a result, the modelled near-surface atmospheric CH4 mixing ratio and therefore the condensation rates are higher on top of the mountains (which peak into an atmosphere richer in CH4) than in the depressions (Fig. 3a, b). As shown in ‘Methods’ (see CH4 and CO condensation–sublimation on the surface), the CH4 condensation is also controlled by the near-surface winds, which mix gaseous CH4 near the surface (turbulent mixing). The model predicts that on Pluto, these winds tend to be stronger on the steepest slopes, such as on the flanks of Pigafetta Montes where slopes can range up to 45°9 (Fig. 3a), which enhances CH4 condensation rates there.

Fig. 3. Atmospheric CH4 abundance and surface temperatures drive CH4 condensation and accumulation on mountain summits.

a Near-surface CH4 atmospheric mixing ratio in Cthulhu as simulated by our model (filled contours, in %) with arrows indicating winds at 5 m above the surface. b Cross-section of Cthulhu at 5°S showing the diurnal mean CH4 mass mixing ratio (kg kg−1) above the local surface (red solid line) and the diurnal mean CH4 mass mixing ratio at saturation (red dotted line), as obtained in our simulation for July 2015; the topography; and the thickness of the surface layer of CH4 ice (black solid line); and the thickness of the surface layer of CH4 ice (about ∼40 µm on top of Pigafetta Montes, blue solid line). The shaded areas indicate where there is saturation of CH4 above the surface (in diurnal mean) that leads to condensation onto the surface. c Same cross-section showing the diurnal mean surface temperature (solid line) as obtained in our simulation. The diurnal minimal and maximal surface temperatures are also indicated (dotted lines). Colder daytime temperatures are obtained where CH4 ice is present, due to the brighter surface (albedo positive feedback). Maps are shown in the Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2.

Discussion

Why is Pluto’s equatorial atmosphere depleted in gaseous CH4 near the surface and enriched at higher altitudes in the model? This could have been a consequence of CH4 cloud formation, with condensation in the cold, lowest atmospheric levels, but we ruled out this hypothesis by performing a simulation in which atmospheric condensation was artificially neglected: it yielded the same results.

In fact, the model indicates that ascending winds in the western regions of Sputnik Planitia are responsible for this enrichment by transporting gaseous CH4 upward. Analysing the general circulation indicates that two different mechanisms are involved. First, as N2 sublimes in the north and condenses in the south, it triggers a meridional circulation dominated by a north-to-south flow and characterized by one circulation cell centred above Sputnik Planitia16. As CH4 ice sublimes in the northern hemisphere, it is transported southward and toward higher altitudes above the equatorial regions by this circulation cell. Second, the interaction between the zonal flow and the high western boundary of Sputnik Planitia’s basin produces vertical upward motions which also contributes to the vertical transport of gaseous CH4.

Overall, the formation of CH4 frost on top of Pluto’s mountains appears to be driven by a process completely different from the one forming snow-capped mountains on the Earth, according to our model. It is remarkable that two phenomena and two materials that are so dissimilar could produce the same landscape, when seen at similar resolution (Supplementary Fig. 4). The proposed plutonian process creating frost-capped mountains may control an important factor governing the CH4 cycle on Pluto in general. In particular, it might help explain the bladed texture of Tartarus Dorsa, the massive CH4 deposits located east of Sputnik Planitia11, by favouring CH4 condensation at higher altitude (bladed terrain is found almost exclusively at elevations >2 km above the mean radius8). In such conditions, initially elevated portions of the CH4 deposits may represent sites of increased CH4 condensation relative to lower portions, and so their positive topographic relief may gradually be amplified. This would complement the ‘penitente model’11,21 in which the bladed texture is suggested to be mostly induced by sublimation processes.

Methods

The LMD Pluto GCM

We used the LMD Pluto GCM14,16 to simulate Pluto’s climate and the methane cycle in 2015. The model includes atmospheric dynamics and transport, turbulence, radiative transfer and molecular conduction as well as phase changes for N2, CH4 and CO. The GCM reproduces well the thermal structure measured by the New Horizons spacecraft in the lower atmosphere (below 200 km altitude) and the threefold increase in surface pressure observed from stellar occultations between 1988 and 2015 with ~1.1 Pa in 20155,22. Recent improvements to the model include incorporation of perennial high-altitude CH4 deposits in the equatorial regions (bladed terrain), based on mapping of Pluto’s far side18, and the use of the latest topography from New Horizons data9. We use flat topography for the non-observed southern hemisphere. Adding topography in the southern hemisphere does not impact the results of this paper. The general circulation is strongly controlled by the north-to-south N2 flow and is not significantly impacted by the presence of N2 ice deposits outside Sputnik Planitia16.

Initial state of the reference simulation and grid resolution

The initial state for the GCM is derived from simulations performed with the 2D LMD Pluto volatile transport model over 30-million years, taking into account the orbital and obliquity changes of Pluto over time16,19,20. These long-term simulations allow the surface ice distribution (N2, CH4 and CO ices), surface temperatures and soil temperatures to reach a steady state for current-day Pluto. The initial state of the atmosphere in the 3D GCM is an isothermal profile. We run the GCM from 1984 to 2015 which is sufficient to reach a steady state for the atmosphere and a realistic circulation regime insensitive to the initial state14.

The long-term volatile transport simulations and the low-resolution GCM simulations are performed with a horizontal grid of 32 × 24 points to cover the globe (i.e. 11.25 × 7.5°, ~150 km in latitude) and 27 vertical levels. Simulations for the years 2014 and 2015 are then performed with a higher spatial resolution by using a grid of 96 × 72 points (3.75 × 2.5, ~50 km in latitude) and 47 vertical levels (with a first level at z1 = 5 m).

Surface conditions

Our GCM simulations have been performed using an N2 ice emissivity of 0.8 and albedo of 0.7. The surface N2 pressure simulated in the model is constrained by these values. The albedo and emissivity of the bare ground (volatile-free surface) are set to 0.1 and 1, respectively, which corresponds to a terrain covered by dark materials such as Cthulhu10. Methane ice emissivity is fixed to 0.8 in all simulations. We use a CH4 ice–albedo of 0.5 for the equatorial deposits (except when the albedo feedback scheme is on, see below) and of 0.65 for the polar deposits, which is consistent with the available albedo maps of Pluto10.

The thermal conduction into the subsurface is performed with a low thermal inertia near the surface, set to Id = 20 J s−0.5 m−2 K−1, to capture the short-period diurnal thermal waves and a larger thermal inertia below set to Is = 800 J s−0.5 m−2 K−1 to capture the much longer seasonal thermal waves which can penetrate deep into the high-TI substrate. The rest of the settings are similar to the previous simulations of Pluto with the LMD GCM14,16. We assume a density for CH4 ice of 500 kg m−3 20.

CH4 and CO condensation–sublimation on the surface

CH4 and CO are minor constituents of Pluto’s N2 atmosphere and their surface–atmosphere interactions depend on the turbulent fluxes given by:

| 1 |

with qsurf the saturation vapour pressure mass mixing ratio (in kg kg−1) at the considered surface temperature, q the atmospheric mass mixing ratio, ρ the air density, U the horizontal wind velocity and Cd the drag coefficient at 5 m above the local surface (Cd = 0.06). qsurf is computed using the thermodynamic Claudius–Clapeyron relation23 for CH4 with a latent heat for sublimation of 586.7 kJ kg−1.

On Pluto’s surface, the volatile ices should form solid solutions whose phases follow ternary phase equilibria; they do not exhibit ideal behaviour12,24. We note that sophisticated equations of state exist for the N2–CH4 and N2–CH4–CO systems under Pluto surface conditions (CRYOCHEM12). These ternary and binary systems, as currently understood12, are able to explain a great diversity of phases (CH4-rich, N2-rich and N2-rich+CH4-rich solids) that are seen on Pluto within the range of expected temperatures and relatively unvarying surface pressure and strongly N2-dominated vapour composition seen on Pluto.

At the temperature of the CH4 deposits modelled in this paper (∼45 K, prevailing at high altitudes), the ternary phase equilibria shown by Tan and Kargel12 predict that two phases coexist: a very nearly pure CH4 solid (≪1% impurities of N2 and CO in solid solution) and N2-rich vapour. This is consistent, to first order, with the observations by New Horizons and with what we report in this paper and in Fig. 1.

However, as these equations of state have not been coded for use in a GCM or been applied to the specific distribution of ices and temperatures seen on Pluto or in a GCM, we have substituted the alternative of relying on Raoult’s law, as described next. It is possible that for conditions of rapid frost deposition, the solid condensates may be amorphous mixtures, which might tend to exhibit thermodynamics somewhat like those implied by Raoult’s law. Accordingly, we interpret Pluto to be a non-equilibrium dynamical environment with continuous exchange of materials (condensation, sublimation, atmospheric transport…), including on daily timescales where departures from equilibrium could be likely.

Future work involving laboratory experiments, spectroscopic analyses, thermodynamic models and GCMs is strongly needed to improve the models, constrain the timescales for ice relaxation toward thermodynamics equilibrium and explore in detail the effect of the ternary phase equilibrium on Pluto (and on other Trans-Neptunian objects).

Here, for simplicity in coding with a GCM, we have adopted Raoult’s law, as in previous GCM studies14,16,17. We consider the mixtures N2:CH4 and N2:CO with 0.5% of CH4 and 0.3% of CO respectively, as retrieved from telescopic observations and from New Horizons observations4,25. However, we note that Raoult’s law was at first intended for vapour–liquid equilibria and ideal solutions only, which do not include the N2–CH4–CO system observed on Pluto. Despite the fact that this approximation gives good results and allows for reproducing the atmospheric mixing ratios observed by New Horizons observations17, it may still introduce errors on sublimation and condensation rates of the different types of ice. This approximation seems sufficient for our present needs and for the study of CH4-rich ice deposits on Pluto’s surface, which are the focus of this paper, but we acknowledge that it leads to some unevaluated uncertainties in CH4 solid-phase stability.

Surface albedo feedback for equatorial CH4 ice

We tested the impact of an amplifying surface ice–albedo feedback on the results. To do that, we allowed the surface CH4 ice–albedo to change depending on the thickness of ice Q present on the surface. We assumed a minimal albedo of Amin = 0.1 for deposits thinner than Qlim = 1 μm, and a maximal albedo of Amax = 0.9 for the thickest deposits. In the model, this change is applied to CH4 ice in the equatorial regions only, outside the bladed terrain deposits (i.e. only recent frost). We use a simple hyperbolic tangent function for the transition between the extreme albedo values (tanh functions are commonly used in climate models to represent time-variation of icy surfaces albedo26):

| 2 |

In our model, this ice–albedo scheme leads to a strong positive feedback when CH4 condenses on the surface, as it lowers the surface temperature and therefore the near-surface CH4 mixing ratio at saturation, thus allowing for a further increase of the CH4 condensation rate. Note that the goal here is to boost the effect of albedo feedback with a simple representation within the time of the simulation, but these changes in surface albedo may actually occur over longer timescales, and be efficient for deposits thicker than ~1 mm.

Phase index maps

The phase index, as defined in Schmitt et al.3 is an index allowing discrimination between CH4 diluted in N2 ice and CH4-rich ice phases based on the position of a set of CH4 near-infrared bands. It is thus based on the measure of the shift of these bands upon dilution in N2 ice as measured in the laboratory27.

At the spatial resolution of the LEISA measurements (2.7 km in the high-resolution strip used for Fig. 1d, f, and 7 km used for the 1e panel) we cannot discriminate between a patchwork distribution of N2-rich and CH4-rich ice at scale below a few kilometres, with an intimate mixture of the crystals of both phases or a vertical stratification (but at sub-mm scale). However, taking into account the noise and detection level, the maps show that nitrogen may be only present in some very localized area at low altitude. The phase index maps clearly point to a CH4-rich dominant composition.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Kevin Zahnle, Jeff Moore, John Wilson, Bob Haberle and Melinda Kahre for insightful discussions and stimulating discussions and comparisons between Mars and Pluto. We thank the NASA New Horizons team for their excellent work on a fantastic mission and their interest in this research. We thank the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) for its financial support through its “Système Solaire” programme. T.B. was supported for this research by an appointment to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Post-doctoral Programme at the Ames Research Center administered by Universities Space Research Association (USRA) through a contract with NASA.

Author contributions

T.B. and F.F. designed and developed the model. T.B. performed the simulations. T.B. and F.F. made the modelling figures, B.S. and W.G. produced the LEISA maps, T.B. and F.F. wrote the manuscript with significant contributions from B.S. and O.W.

Data availability

The GCM data is freely available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

All model versions are freely available upon request by contacting the corresponding authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Jeffrey Kargel and Laurence Trafton for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tanguy Bertrand, Email: tanguy.bertrand@nasa.gov.

François Forget, Email: forget@lmd.jussieu.fr.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-18845-3.

References

- 1.Grundy WM, et al. Surface compositions across Pluto and Charon. Science. 2016;351:6279. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Earle AM, et al. Methane distribution on Pluto as mapped by the New Horizons Ralph/MVIC instrument. Icarus. 2018;314:195–209. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2018.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmitt B, et al. Physical state and distribution of materials at the surface of Pluto from New Horizons LEISA imaging spectrometer. Icarus. 2017;287:229–260. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Protopapa S, et al. Pluto’s global surface composition through pixel-by-pixel Hapke modeling of New Horizons Ralph/LEISA data. Icarus. 2017;287:218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stern AS, et al. The Pluto system: initial results from its exploration by New Horizons. Science. 2015;350:6258. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore JF, et al. The geology of Pluto and Charon through the eyes of New Horizons. Science. 2016;351:1284–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grundy WM, et al. Pluto’s haze as a surface material. Icarus. 2018;314:232–245. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2018.05.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruikshank DP, et al. Recent cryovolcanism in Virgil Fossae on Pluto. Icarus. 2019;330:155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2019.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schenk PM, et al. Basins, fractures and volcanoes: global cartography and topography of Pluto from New Horizons. Icarus. 2018;314:400–433. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2018.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buratti BJ, et al. Global albedos of Pluto and Charon from LORRI New Horizons observations. Icarus. 2017;287:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.11.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore JM, et al. Bladed Terrain on Pluto: possible origins and evolution. Icarus. 2018;300:129–144. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2017.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan SP, Kargel JS. Solid-phase equilibria on Pluto’s surface. Monthly Not. R. Astronomical Soc. 2018;474:4254–4263. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stx3036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young, L. A. et al. On the disequilibrium of Pluto’s volatiles. Conference abstract: Pluto System After New Horizons,2133, 7039 (2019).

- 14.Forget F, et al. A post-new horizons global climate model of Pluto including the N2, CH4 and CO cycles. Icarus. 2017;287:54–71. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.11.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinson DP, et al. Radio occultation measurements of Pluto’s neutral atmosphere with New Horizons. Icarus. 2017;290:96–111. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2017.02.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertrand T, et al. Pluto’s beating heart regulates the atmospheric circulation: results from high resolution and multi-year numerical climate simulations. JGR. 2020;125:e2019JE006120. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertrand, T. & Forget, F. Observed glacier and volatile distribution on Pluto from atmosphere-topography processes. Nature, 540, 86–89 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Stern, S. A. et al. Pluto’s far side. Icarus356, 113805 10.1016/j.icarus.2020.113805 (2020).

- 19.Bertrand T, et al. The nitrogen cycles on Pluto over seasonal and astronomical timescales. Icarus. 2018;309:277–296. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2018.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertrand T, et al. The CH4 cycles on Pluto over seasonal and astronomical timescales. Icarus. 2019;329:148–165. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2019.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moores JE, et al. Penitentes as the origin of the bladed terrain of Tartarus Dorsa on Pluto. Nature. 2017;541:188–190. doi: 10.1038/nature20779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meza, E. et al. Lower atmosphere and pressure evolution on Pluto from ground-based stellar occultations, 1988–2016. Astron. Astrophys.625, A42 (2019).

- 23.Fray N, Schmitt B. Sublimation of ices of astrophysical interest: a bibliographic review. Planet. Space Sci. 2009;57:2053–2080. doi: 10.1016/j.pss.2009.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trafton LM. On the state of methane and nitrogen ice on Pluto and Triton: implications of the binary phase diagram. Icarus. 2015;246:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2014.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merlin F. New constraints on the surface of Pluto. Astron. Astrophys. 2015;582:A39. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201526721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saltzman, B. Dynamical Paleoclimatology: Generalized Theory of Climate Change (Academic Press, San Diego, 2002).

- 27.Quirico E, Schmitt B. Near-infrared spectroscopy of simple hydrocarbons and carbon oxides diluted in solid N2 and as pure ices: implications for Triton and Pluto. Icarus. 1997;127:354. doi: 10.1006/icar.1996.5663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The GCM data is freely available from the corresponding authors upon request.

All model versions are freely available upon request by contacting the corresponding authors.