Abstract

We investigated whether or not nitric oxide synthase 3 (NOS3) rs2070744 genotypes can affect the response for lenvatinib treatment in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We evaluated the relation of the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes to the tumor response, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) as the response for lenvatinib. We also examined the association between fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) gene polymorphisms, a potential feature of lenvatinib, and the response. There were no significant differences between the studies for either PFS or OS, even though patients with the TT genotype had a longer mean PFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.60; p = 0.069) and mean OS (HR 0.46; p = 0.075) than those with the TC/CC genotypes. However, patients with a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) combination pattern of the NOS3 rs2070744 TC/CC and FGFR4 rs351855 CT/TT genotypes had a significantly shorter mean PFS (HR 2.56; p = 0.006) and mean OS (HR 3.36; p = 0.013) than those with the other genotypes. The NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes did not influence the clinical response. However, the SNP combination pattern of the NOS3 rs2070744 and FGFR4 rs351855 genotypes may be helpful as treatment effect predictors and prognostic factors for HCC patients treated with lenvatinib.

Subject terms: Cancer, Genetics, Biomarkers, Gastroenterology, Medical research, Molecular medicine, Oncology

Introduction

Lenvatinib, a novel multikinase inhibitor, was found to be comparable to sorafenib in overall survival (OS) in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients in a randomized phase III non-inferiority (REFLECT) trial1–5. Therefore, it is now prescribed as the first-line therapy for advanced unresectable HCC. Compared with those for cancer-targeted treatments, the predictive factors for the response to lenvatinib, which target the microenvironment of the tumor, are unknown. The identification of such markers could improve the management of HCC by selecting the most effective therapeutic options available6. Some researchers have reported that a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) or the NOS3 gene influences the response to sorafenib in patients with HCC7,8. The production of endogenous NO plays an essential role in carcinogenesis and tumor growth progression.

Three distinct genes, NOS1, NOS2, and NOS3, encode the NOS isoforms: the neuronal (nNOS), inducible (iNOS), and eNOS, and the genetic variations present in genes encoding for NOS isoforms can affect NOS expression9. A point mutation of thymine to cytosine at the NOS3 T-786C polymorphism (rs2070744) results in the altered NOS protein levels and enzymatic activity10,11. The previous study has reported a correlation between the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes and the clinical response to sorafenib, which exerts antitumor effects by inhibiting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), in patients with HCC12.

Lenvatinib exerts antitumor effects by inhibiting receptor tyrosine kinases, including VEGFR5. The NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes may be useful predictors of the clinical response to lenvatinib. However, lenvatinib is a multiple receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting not only VEGFR but also fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR), platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, and KIT and RET proto-oncogenes. The potent activity against FGFR is a characteristic of lenvatinib, unlike sorafenib. Thus, there may be a difference in the responsiveness of NOS3 polymorphisms to HCC between lenvatinib and sorafenib. Therefore, we analyzed the role of the NOS3 polymorphism on HCC patients treated with lenvatinib.

Results

Enrolled patients

Of the 168 patients enrolled in this study, 68 (40.5%) patients were excluded (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online). Therefore, relevant clinical data were collected from 100 patients in three medical centers in Kanagawa: Kitasato University Hospital (n = 56), Yokohama City University Medical Center (n = 27), and Shonan Kamakura General Hospital (n = 17). All the patients from Shonan Fujisawa Tokushukai Hospital were excluded from the study because they did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Correlation between the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes and clinical characteristics

The demographic characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. The frequencies of TT, TC, and CC of the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes were 76%, 23%, and 1%, respectively. The number of patients with the TT and TC/CC genotypes was 76 and 24, respectively. Comparing the clinical characteristics of patients with the TT genotype with those of patients with the TC/CC genotypes, there were no significant differences between the groups.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics.

| Characteristics | All (N = 100) | NOS3 rs2070744 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT (n = 76) | TC/CC (n = 24) | |||

| Median age (IQR), years | 72 (66–78) | 73 (66–79) | 72 (65–78) | 0.625 |

| Age ≥ 65 years, n (%) | 76 (76) | 58 (76) | 18 (75) | 1.000 |

| Age ≥ 75 years, n (%) | 43 (43) | 35 (46) | 8 (33) | 0.347 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 68 (68) | 54 (71) | 14 (58) | 0.316 |

| Etiology of HCC, n (%) | ||||

| Hepatitis B | 17 (17) | 12 (16) | 5 (21) | 0.504 |

| Hepatitis C | 41 (41) | 34 (45) | 7 (29) | |

| Alcohol use | 15 (15) | 10 (13) | 5 (21) | |

| Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis | 21 (21) | 14 (18) | 7 (29) | |

| Others | 7 (7) | 6 (8) | 1 (4) | |

| ECOG-PS, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 95 (95) | 71 (93) | 24 (100) | 0.333 |

| 1 | 5 (5) | 5 (7) | 0 | |

| Child–Pugh system, n (%) | ||||

| Class A5 | 61 (61) | 46 (61) | 15 (63) | 0.984 |

| Class A6 | 22 (22) | 17 (22) | 5 (21) | |

| Class B | 17 (17) | 13 (17) | 4 (17) | |

| Bodyweight ≥ 60 kg, n (%) | 59 (59) | 44 (58) | 15 (63) | 0.813 |

| Median BMI (IQR), kg/m2 | 23.0 (21.1–25.2) | 22.9 (21.1–25.1) | 23.2 (20.8–26.7) | 0.663 |

| BCLC staging system, n (%) | ||||

| Stage B (intermediate stage) | 55 (55) | 41 (54) | 14 (58) | 0.815 |

| Stage C (advanced stage) | 45 (45) | 35 (46) | 10 (42) | |

| Macroscopic PVI, extrahepatic spread, or both, present, n (%) | 37 (37) | 27 (36) | 10 (42) | 0.303 |

| Up-to-seven criteria, n (%) | ||||

| within | 60 (60) | 45 (59) | 15 (63) | 0.816 |

| beyond | 40 (40) | 31 (41) | 9 (38) | |

| Maximum tumor size > 5 cm, n (%) | 28 (28) | 22 (29) | 6 (25) | 0.799 |

| Number of tumors, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 14 (14) | 10 (13) | 4 (17) | 0.703 |

| 2 | 13 (13) | 11 (14) | 2 (8) | |

| ≥ 3 | 69 (69) | 52 (68) | 17 (71) | |

| UICC-TNM staging system, n (%) | ||||

| I and II | 25 (25) | 18 (24) | 7 (29) | 0.597 |

| III and IV | 75 (75) | 58 (76) | 17 (71) | |

| Tumor liver occupying rate ≥ 50%, n (%) | 6 (6) | 4 (5) | 2 (8) | 0.628 |

| Initial dose, n (%) | ||||

| 12 mg | 32 (32) | 23 (30) | 9 (38) | 0.704 |

| 8 mg | 49 (49) | 39 (51) | 10 (42) | |

| 4 mg | 19 (19) | 14 (18) | 5 (21) | |

| RDI at 56 days ≥ 80%, n (%) | 44 (44) | 31 (41) | 13 (54) | 0.328 |

| ALBI grade | ||||

| Grade 1 (≤ − 2.60) | 44 (44) | 36 (47) | 8 (33) | 0.372 |

| Grade 2 (> − 2.60 to ≤ − 1.39) | 54 (54) | 39 (51) | 15 (63) | |

| Grade 3 (> − 1.39) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (4) | |

| AFP at baseline ≥ 200 ng/mL, n (%) | 35 (35) | 24 (32) | 11 (46) | 0.226 |

| AFP at baseline ≥ 400 ng/mL, n (%) | 31 (31) | 22 (29) | 9 (38) | 0.455 |

| Median PIVKA- II (IQR), mAU/mL | 392 (74–2200) | 346 (74–2420) | 672 (105–1489) | 0.686 |

AFP α-fetoprotein, ALBI albumin-bilirubin, BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, BMI body mass index, ECOG-PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-Performance Status, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, IQR interquartile range, NOS3 nitric oxide synthase 3, PIVKA-II protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist II, PVI portal vein invasion, RDI relative dose intensity.

Effect of NOS3 rs2070744 on tumor response

Tumor response rates are summarized in Table 2. The confirmed objective response rates were 54% with the NOS3 rs2070744 TC/CC genotypes and 42% with the TT genotype (odds ratio [OR] 1.63; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.58–4.56; p = 0.351). The disease control rate (objective response plus stable disease) was 83% with the TC/CC genotypes and 84% with the TT genotype (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.25–4.44; p = 1.000).

Table 2.

Effect of the NOS3 rs2070744 on tumor response, progression-free survival, and overall survival.

| Variable | N | Tumor response | Progression-free survival | Overall survival | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORR, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p | DCR, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p | Mean months (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | p | Mean months (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | p | ||

| NOS3 rs2070744 | |||||||||||||

| TC + CC | 24 | 13 (54) | 1.63 (0.58–4.56) | 0.351 | 20 (83) | 0.94 (0.25–4.44) | 1.000 | 7.5 (4.8–10.2) | 1 (ref) | 0.069 | 16.1 (12.7–19.4) | 1 (ref) | 0.075 |

| TT | 76 | 32 (42) | 64 (84) | 10.6 (8.9–12.4) | 0.60 (0.34–1.05) | 22.3 (20.2–24.4) | 0.46 (0.19–1.11) | ||||||

CI confidence interval, DCR disease control rate (objective response plus stable disease), HR hazard ratio, NOS3 nitric oxide synthase 3, OR odds ratio, ORR objective response rate (complete and partial response).

Effect of NOS3 rs2070744 on PFS and OS

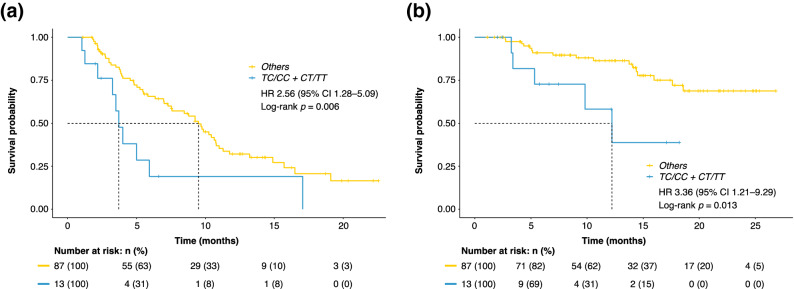

Figure 1 and Table 2 show the effect of the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes on clinical outcomes. The mean progression-free survival (PFS) of all enrolled patients was 10.0 (95% CI 8.5–11.5) months. The mean PFS of the NOS3 rs2070744 TC/CC genotypes and the TT genotype was 7.5 (95% CI 4.8–10.2) months and 10.6 (95% CI 8.9–12.4) months, respectively. There were no significant differences between the PFS of the two groups (HR 0.60; 95% CI 0.34–1.05; p = 0.069). The mean OS of all enrolled patients was 21.3 (95% CI 19.4–23.3) months. The mean OS of the TC/CC genotypes and TT genotype was 16.1 (95% CI 12.7–19.4) months and 22.3 (95% CI 20.2–24.4) months, respectively. There were no significant differences between the OS of the two groups (HR 0.46; 95% CI 0.19–1.11; p = 0.075).

Figure 1.

(a) Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS according to the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes: TC/CC (blue line) vs. TT (yellow line). (b) Kaplan–Meier curves of OS according to the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes: TC/CC (blue line) vs. TT (yellow line). CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, NOS3 nitric oxide synthase 3, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival.

Effects of the FGFR gene polymorphisms on clinical response

Table 3 shows the effect of the FGFR gene polymorphisms on clinical outcomes. FGFR2 (rs2912791, rs2981429, rs2981582) and FGFR4 (rs351855) showed no significant differences in tumor response, PFS, or OS.

Table 3.

Effects of FGFR alone and in combination with NOS3 polymorphism on tumor response, progression-free survival, and overall survival.

| Variable | N | Tumor response | Progression-free survival | Overall survival | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORR, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p | DCR, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p | Mean months (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | p | Mean months (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | p | ||

| FGFR2 rs2912791 | |||||||||||||

| CT + CC | 66 | 31 (47) | 0.79 (0.31–1.97) | 0.673 | 57 (86) | 0.61 (0.18–2.16) | 0.398 | 10.4 (8.5–12.3) | 1 (ref) | 0.490 | 21.5 (19.1–23.8) | 1 (ref) | 0.771 |

| TT | 34 | 14 (41) | 27 (79) | 9.3 (6.8–11.8) | 1.20 (0.72–1.99) | 19.8 (16.6–22.9) | 1.14 (0.48–2.71) | ||||||

| FGFR2 rs2981429 | |||||||||||||

| CT + TT | 48 | 23 (48) | 0.80 (0.34–1.89) | 0.688 | 41 (85) | 0.82 (0.23–2.73) | 0.789 | 10.4 (8.2–12.5) | 1 (ref) | 0.541 | 21.5 (18.9–24.1) | 1 (ref) | 0.742 |

| CC | 52 | 22 (42) | 43 (83) | 9.5 (7.3–11.6) | 1.17 (0.71–1.91) | 19.9 (17.3–22.5) | 1.15 (0.50–2.66) | ||||||

| FGFR2 rs2981582 | |||||||||||||

| CT + CC | 91 | 41 (45) | 0.98 (0.18–4.86) | 1.000 | 77 (85) | 0.64 (0.11–6.93) | 0.633 | 10.0 (8.4–11.7) | 1 (ref) | 0.817 | 21.0 (19.0–23.1) | 1 (ref) | 0.441 |

| TT | 9 | 4 (44) | 7 (78) | 10.4 (7.4–13.4) | 0.91 (0.39–2.11) | 21.1 (15.5–26.6) | 0.46 (0.06–3.45) | ||||||

| FGFR4 rs351855 | |||||||||||||

| CT + TT | 63 | 28 (44) | 0.94 (0.39–2.31) | 1.000 | 54 (86) | 1.40 (0.40–4.71) | 0.580 | 10.3 (8.4–12.2) | 1 (ref) | 0.552 | 21.4 (19.0–23.8) | 1 (ref) | 0.963 |

| CC | 37 | 17 (46) | 30 (81) | 9.3 (6.9–11.7) | 1.17 (0.70–1.94) | 19.8 (16.9–22.6) | 1.02 (0.43–2.44) | ||||||

| NOS3 rs2070744 + FGFR4 rs351855 | |||||||||||||

| Others | 87 | 41 (47) | 0.50 (0.10–1.97) | 0.373 | 74 (85) | 0.59 (0.13–3.77) | 0.432 | 10.6 (9.0–12.3) | 1 (ref) | 0.006 | 22.0 (20.1–24.0) | 1 (ref) | 0.013 |

| TC/CC + CT/TT | 13 | 4 (31) | 10 (77) | 6.0 (2.7–9.3) | 2.56 (1.28–5.09) | 12.0 (8.1–15.8) | 3.36 (1.21–9.29) | ||||||

CI confidence interval, DCR disease control rate (objective response plus stable disease), FGFR2 fibroblast growth factor receptor 2, FGFR4 fibroblast growth factor receptor 4, HR hazard ratio, NOS3 nitric oxide synthase 3, OR odds ratio, ORR objective response rate (complete and partial response).

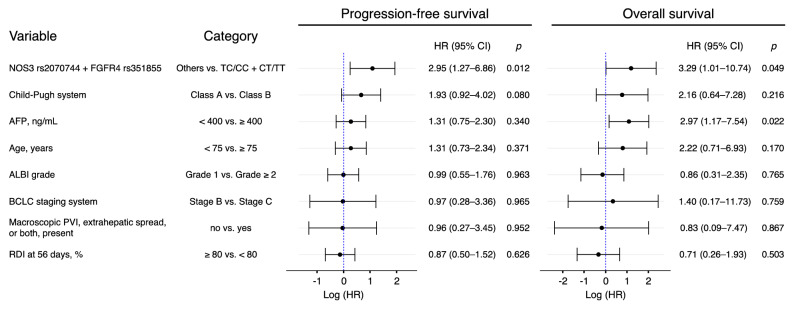

The SNP combination pattern and clinical outcomes

Figure 2 and Table 3 show the effect of FGFR alone and in combination with the NOS3 polymorphism on clinical outcomes. According to the effects of an SNP combination pattern of the NOS3 rs2070744 and FGFR4 rs351855 genotypes, patients with the NOS3 rs2070744 TC/CC and FGFR4 rs351855 CT/TT genotypes had a significantly shorter mean PFS of 6.0 (95% CI 2.7–9.3) months than did those with the other genotypes who had a mean PFS of 10.6 (95% CI 9.0–12.3) months (HR 2.56; 95% CI 1.28–5.09; p = 0.006). Similarly, patients with the TC/CC and CT/TT genotypes had a significantly shorter mean OS of 12.0 (95% CI 8.1–15.8) months than did those with the other genotypes who had a mean OS of 22.0 (95% CI 20.1–24.0) months (HR 3.36; 95% CI 1.21–9.29; p = 0.013).

Figure 2.

(a) Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS according to an SNP combination pattern of the NOS3 rs2070744 and FGFR4 rs351855: TC/CC + CT/TT genotypes (blue line) vs. Others (yellow line). (b) Kaplan–Meier curves of OS according to an SNP combination pattern of the NOS3 rs2070744 and FGFR4 rs351855: TC/CC + CT/TT genotypes (blue line) vs. Others (yellow line). CI confidence interval, FGFR4 fibroblast growth factor receptor 4, HR hazard ratio, NOS3 nitric oxide synthase 3, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors affecting the PFS and OS

We evaluated the relationship between the clinical response and the baseline clinical characteristics using a logistic regression model (see Supplementary Table S1 online). Table 4 provides the factors most associated with survival. In multivariate analysis adjusted for the Child–Pugh system (Class A vs. Class B), α-fetoprotein (< 400 vs. ≥ 400), age (< 75 vs. ≥ 75), albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade (Grade 1 vs. Grade ≥ 2), Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system (Stage B vs. Stage C), Macroscopic portal vein invasion, extrahepatic spread, or both, present (no vs. yes), and relative dose intensities at 56 days (≥ 80% vs. < 80%). The SNP combination pattern of the NOS3 rs2070744 TC/CC and FGFR4 rs351855 CT/TT genotypes was significantly associated with both PFS (HR 2.95; 95% CI 1.27–6.86; p = 0.012) and OS (HR 3.29; 95% CI 1.01–10.74; p = 0.049), respectively.

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis for baseline prognostic factors for progression-free survival and overall survival.

AFP α-fetoprotein, ALBI albumin-bilirubin, BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, CI confidence interval, FGFR4 fibroblast growth factor receptor 4, HR hazard ratio, NOS3 nitric oxide synthase 3, PVI portal vein invasion, RDI relative dose intensity.

Adverse event assessment

The most common adverse events among patients who received lenvatinib were anorexia (59%), fatigue (55%), palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (47%), abdominal pain (41%), and diarrhea (41%) (see Supplementary Table S2 online). Adverse events associated with lenvatinib forced dose reductions and discontinuation in 57% and 46% of the patients, respectively. The median time to the first dose reduction was 1.3 (interquartile range [IQR]; 0.8–3.0) months among the patients for whom the dose was reduced due to adverse events. The median time to dose reduction of the NOS3 rs2070744 TT genotype and TC/CC genotypes was 1.3 (IQR; 0.8–3.0) months and 1.4 (IQR; 0.9–3.4) months, respectively. There were no significant differences between the median time of the two groups (p = 0.627). Grade 3 adverse events occurred in 33 (43%) patients with the NOS3 rs2070744 TT genotype and 10 (42%) patients with the TC/CC genotypes. Grade 3 adverse events also occurred in 16 (43%) patients with the FGFR4 rs351855 CC genotype and 27 (43%) patients with the CT/TT genotypes. No grade 4 adverse events were observed. The median treatment duration was 6.4 (IQR; 2.5–12.6) months for the enrolled patients. The median treatment duration with the NOS3 rs2070744 TT genotype was longer than that with the TC/CC genotypes (6.9 [IQR; 2.5–12.9] months vs. 5.6 [IQR; 2.4–9.0] months, p = 0.611); however, the incidence rate of adverse events was similar.

Table 5 shows the impact on clinical outcomes of adverse events with an incidence rate of 30% or more. The mean PFS of the patients who developed grades 2 or 3 hypertension (n = 20) was significantly longer than that for those who developed grade 1 hypertension (n = 15) (10.9 [95% CI 7.5–14.2] months vs. 5.5 [95% CI 3.1–7.8] months; HR 0.37 [95% CI 0.17–0.83]; p = 0.012). There were no significant differences between the OS of the two groups (22.7 [95% CI 19.1–26.3] months vs. 16.6 [95% CI 11.3–21.9] months; HR 0.38 [95% CI 0.11–1.36]; p = 0.123). There were no correlations between the genetic polymorphisms, including those of the NOS3 gene, and the prevalence and severity of adverse events.

Table 5.

Effect of the adverse events on progression-free survival and overall survival.

| Variable | N | Progression-free survival | Overall survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean months (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | p | Mean months (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Anorexia | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 10 | 8.8 (3.7–13.9) | 1 (ref) | 0.702 | 26.8 (26.8–26.8) | N/A | 0.087 |

| Grade ≥ 2 | 49 | 8.7 (6.8–10.5) | 1.19 (0.50–2.84) | 18.8 (16.2–21.4) | |||

| Fatigue | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 31 | 8.6 (6.3–11.0) | 1 (ref) | 0.540 | 19.9 (16.6–23.2) | 1 (ref) | 0.429 |

| Grade ≥ 2 | 24 | 7.6 (5.4–9.7) | 1.21 (0.66–2.22) | 18.6 (14.7–22.5) | 1.48 (0.56–3.93) | ||

| PPE | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 25 | 8.3 (5.9–10.8) | 1 (ref) | 0.547 | 21.1 (17.3–25.0) | 1 (ref) | 0.857 |

| Grade ≥ 2 | 22 | 9.5 (6.6–12.5) | 0.82 (0.42–1.58) | 19.7 (16.1–23.2) | 1.11 (0.37–3.31) | ||

| Abdominal pain | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 26 | 8.3 (5.5–11.0) | 1 (ref) | 0.779 | 18.9 (15.3–22.4) | 1 (ref) | 0.929 |

| Grade ≥ 2 | 15 | 7.8 (5.1–10.5) | 1.10 (0.55–2.21) | 20.1 (15.2–25.0) | 0.95 (0.31–2.91) | ||

| Diarrhea | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 24 | 7.1 (5.3–8.9) | 1 (ref) | 0.201 | 17.5 (13.7–21.3) | 1 (ref) | 0.154 |

| Grade ≥ 2 | 17 | 10.7 (6.5–14.9) | 0.62 (0.29–1.30) | 21.3 (17.7–24.9) | 0.40 (0.11–1.48) | ||

| Dysgeusia | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 29 | 7.3 (5.6–9.0) | 1 (ref) | 0.958 | 19.6 (16.0–23.1) | 1 (ref) | 0.635 |

| Grade ≥ 2 | 7 | 7.0 (4.2–9.8) | 1.02 (0.42–2.52) | 16.5 (9.3–23.7) | 1.37 (0.38–4.97) | ||

| Edema | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 24 | 9.9 (6.9–12.8) | 1 (ref) | 0.584 | 24.8 (22.1–27.5) | 1 (ref) | 0.137 |

| Grade ≥ 2 | 12 | 9.0 (5.7–12.2) | 1.24 (0.57–2.70) | 19.7 (15.1–24.4) | 3.38 (0.62–18.6) | ||

| Anxiety | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 28 | 7.2 (5.4–9.1) | 1 (ref) | 0.447 | 19.6 (16.3–22.9) | 1 (ref) | 0.449 |

| Grade ≥ 2 | 7 | 8.9 (3.6–14.1) | 0.69 (0.26–1.82) | 16.7 (9.5–24.0) | 1.66 (0.44–6.29) | ||

| Hypertension | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 15 | 5.5 (3.1–7.8) | 1 (ref) | 0.012 | 16.6 (11.3–21.9) | 1 (ref) | 0.123 |

| Grade ≥ 2 | 20 | 10.9 (7.5–14.2) | 0.37 (0.17–0.83) | 22.7 (19.1–26.3) | 0.38 (0.11–1.36) | ||

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, N/A not available, PPE palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report a correlation between the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes and the clinical response to lenvatinib in patients with unresectable HCC. In a study investigating the utility of NOS3 SNPs, the NOS3 rs2070744 TT genotype was strongly associated with worse prognoses in patients with advanced HCC treated with sorafenib12. However, the NOS3 rs2070744 TC/CC genotypes tended to correspond to a worse prognosis after the administration of lenvatinib, although there were no statistically significant differences. That is, there was a difference in the responsiveness of NOS3 polymorphisms to HCC between the administration of lenvatinib and sorafenib. This can be attributed to the fact that lenvatinib is a multiple receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting not only VEGFR but also FGFR.

HCC is a hypervascularized tumor. Tumor angiogenesis can be effectively suppressed by simultaneously suppressing both VEGFR and FGFR signals. Lenvatinib inhibits angiogenic factor-mediated pathways, including VEGF and FGF, resulting in a subsequent further reduction in NO production. Reduced production of NO, a vasodilator, induces contraction of hepatic stellate cells13. Moreover, it increases intrahepatic vascular resistance and decreases intrahepatic blood flow as well. This infers that the portal hemodynamic effects of lenvatinib are different from those of sorafenib. Lenvatinib significantly aggravates the Congestion index (− 23.1% vs. + 16.2%), which reflects portal hemodynamics, and may exacerbate portal hypertension in patients with advanced HCC14,15.

In the present study, we also revealed that an SNP combination pattern of the NOS3 rs2070744 and FGFR4 rs351855 genotypes was associated with PFS and OS. In another study, it was suggested that the FGFR4 Gly388Arg polymorphism (rs351855) resulted in the transmembrane domain missense mutation and may affect protein expression16. Mutations in the transmembrane domain of the tyrosine kinase receptor can alter the pathological phenotype or signal transduction of FGFR417. Because FGFR4 has the highest expression of transcripts in the liver, FGFR4 rs351855 may regulate HCC signaling18–20. Moreover, the FGFR4 rs351855 CT/TT genotypes sustained receptor activation and improved stability of the receptor more than did the CC genotype. This suggested influence on the response to chemotherapy in HCC patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors21–24.

The NOS3 rs2070744 TC/CC genotypes may reduce the promoter activity of the NOS3 gene compared to the TT genotype, resulting in reduced NO production25–27. As is the case with the portal hemodynamic study14,15, the effects of NO with the NOS3 rs2070744 when treated with lenvatinib may differ from the results of a previous study12. Therefore, we presumed that the NOS3 rs2070744 and FGFR4 rs351855 genotypes could be useful predictors of the clinical response to lenvatinib treatment. The results revealed that the SNP combination pattern of the NOS3 rs2070744 and FGFR4 rs351855 genotypes was helpful as treatment effect predictors and prognostic factors for HCC patients treated with lenvatinib. However, there was no significant difference in the objective response rate. The objective response rate can not always be used to directly evaluate the clinical benefit nor can it be comprehensively used to measure drug efficacy. More research is needed to validate whether or not this SNP combination pattern can be a potential biomarker for chemotherapy.

There have been cases reported correlating patients' clinical response to treatment with drug-related adverse events28–30. In this study, patients who developed grades 2 or 3 hypertension during lenvatinib treatment had significantly longer PFS than those who developed grade 1 hypertension. Moreover, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia and diarrhea of grades 2 or 3 showed a prolonged PFS compared with grade 1. Previous studies have shown that patients who experienced hypertension and hand-foot skin reaction during lenvatinib treatment had significantly better outcomes than did those who did not develop these adverse events31,32. Our findings indicate that hypertension can be a positive predictive marker of prognosis in patients receiving lenvatinib treatment. VEGFR inhibitors such as sorafenib and lenvatinib have been reported to cause endothelial dysfunction associated with reduced NO production and activation of endothelin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor33–37. However, it is unclear why hypertension develops and why it is a marker of improved prognosis. On the other hand, grades 2 or 3 of anorexia and/or fatigue were poor prognostic factors for survival, although the differences were not significant. Anorexia was reported to be one of the common adverse events and was associated with time to discontinuation of lenvatinib treatment32. Anorexia and fatigue may be challenging conditions to alleviate and may affect the continuation of treatment and quality of daily life. The impact of genetic polymorphisms on the prevalence and severity of adverse events should be assessed, and the mechanisms underlying the occurrence of adverse events should be elucidated.

In this study, 55 (55%) patients were in the intermediate BCLC stage B and received systemic lenvatinib therapy. The global standard of care recommended for intermediate BCLC stage B is transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE)38,39. However, recent clinical studies have shown that lenvatinib treatment for patients with intermediate-stage HCC who present with beyond up-to-seven criteria and have Child–Pugh class A prolonged PFS and OS40,41. Therefore, patients in this study with intermediate BCLC stage B and thus less likely to benefit from TACE were also treated with lenvatinib from the initial step at the discretion of their physicians. This study can help provide evidence for the importance of lenvatinib as a first-line treatment in patients with intermediate-stage HCC, who are very difficult to manage with TACE alone.

There were three limitations to this study. First, the selection bias for enrolled patients in this study cohort was undeniable because genomic DNA could not be obtained from all the patients receiving lenvatinib. Some patients, who had a short survival after lenvatinib treatment, could not be enrolled in this study. Therefore, individuals who had an inadequate response to lenvatinib were less likely to participate in the study. The median survival time of all the enrolled patients in this study was longer than that in the REFLECT trial with lenvatinib vs. sorafenib as a first-line treatment in 20185. Moreover, the selection bias was correlated with the outcome. The multivariate analysis showed that an SNP combination pattern of the NOS3 rs2070744 and FGFR4 rs351855 genotypes was an independent factor of lenvatinib response, and a previous report showed that the factors significantly associated with poor OS included skeletal muscle mass index and ALBI grade42. Second, there was no control arm in the present study. Therefore, a clear distinction could not be made between the prognostic role of the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes in patients treated with lenvatinib. Finally, the expression levels of NOS, which are crucial for NO synthesis, were not evaluated. Therefore, NOS expression and NO levels warrant further study and elucidation in patients with HCC.

In conclusion, the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes did not influence the clinical response. However, we found that the SNP combination pattern of the NOS3 rs2070744 and FGFR4 rs351855 genotypes may be helpful as treatment effect predictors and prognostic factors for HCC patients treated with lenvatinib. Multicenter and prospective studies enrolling an appropriate number of patients will be required to confirm further the correlation of genetic polymorphisms with clinical outcomes and adverse events of lenvatinib.

Methods

Ethics

The Institutional Review Board (Ethics Committee) approved this study at all study the institutes involved, and the protocol of this study conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study is registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000036625).

The study was approved by the research ethics board at each participating center, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients were informed about the risk and benefits of the research and then chose to give their consent to participate.

Patients

This retrospective multicenter study was conducted in four medical institutions: Kitasato University Hospital, Yokohama City University Medical Center, Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, and Shonan Fujisawa Tokushukai Hospital in Japan.

Eligible patients (age, ≥ 20 years) with advanced or unresectable HCC caused by chronic liver disease, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-performance status of 1 or less, and adequate organ function were included in this study. We diagnosed HCC by blood tests and imaging modalities and histopathological analyses of biopsy specimens for patients with atypical imaging findings. Critical exclusion criteria included no genomic DNA extracted from whole blood, treatment of cases discontinued within 14 days, severe liver failure (Child–Pugh class C), refractory ascites, end-stage kidney disease, or malignancies other than HCC.

Treatment

Lenvatinib was recommended for patients with advanced BCLC stage C such as portal vein invasion, metastases to distant organs, and for those who were unsuitable and/or refractory to transcatheter arterial therapies. Patients with intermediate BCLC stage B also received systemic lenvatinib therapy at the discretion of their physicians. For patients without risk factors, the recommended dose of lenvatinib was based on body weight: 12 mg/day for patients with a body weight of 60 kg or more and 8 mg/day for patients with a body weight of less than 60 kg. Dose reduction from the initial dose was approved according to the attending physician’s discretion for patients who had risk factors. After the administration of lenvatinib, the dose was changed based on the clinical response and/or the occurrence of severe adverse events. Treatment continued with progressive disease (PD) or until the occurrence of unmanageable adverse events.

Evaluation for treatment response

We defined tumor response according to the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST)43. Tumor response was visualized by a radiologist using either dynamic computed tomography or dynamic magnetic resonance imaging techniques and was assessed by the attending physician. The target lesion in the mRECIST assessment was defined as the contrast-enhanced portion of the lesion in the arterial phase. For the mRECIST assessment, a complete response (CR) was defined as the disappearance of the target lesion. Partial response (PR) was defined as a reduction of at least 30% of the target lesion size compared to the baseline diameter. PD was defined as an increase of at least 20% of the target lesion size. Stable disease (SD) was defined as any case that does not qualify for either PR or PD.

Objective response was defined as the proportion of patients with the best overall response of confirmed CR or PR. Disease control was defined as the best tumor response of CR, PR, or SD. Patients with an unknown response because of missing data could not be evaluated and were therefore excluded from our analyses. We also recorded the best variation (maximal decrease or minimal increase) in the sum of the most significant lesion dimensions for each patient.

End-point measurement

To investigate whether or not the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes can affect the response for lenvatinib treatment in patients with HCC, we examined the influence of the genotypes on the tumor response, PFS, OS, and adverse events. Furthermore, we investigated the impact of the FGFR gene on the response in HCC patients treated with lenvatinib. PFS and OS defined as the time from the first dose of lenvatinib to progression or death (for PFS) or death alone (for OS) according to mRECIST. Adverse event assessments were done according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 definitions.

Genomic DNA isolation

Blood samples from the follow-up patients were exclusively collected in EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) tubes. Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using an automated MagNA Pure Compact Instrument (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) with the MagNA Pure Compact Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit I (Roche) following the manufacturer's instructions.

TaqMan SNP genotyping assays

Genotypes for the NOS3 rs2070744 were determined using the TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Patients were classified as heterozygotic or homozygotic for each allele. They were categorized as the TT genotype (wild type homozygous mutant), the TC genotype (heterozygous mutant), and the CC genotype (homozygous mutant). As SNPs for the FGFR gene, FGFR2 (rs2912791, rs2981429, rs2981582) and FGFR4 (rs351855) were also determined. Chromosomes, positions, and biological effects of the SNPs studied can be found in the Supplementary Table S3 online.

The reaction consisted of 10 μL Master Mix (2 × conc.), 2 μL of the Primer–probe mix (10 × conc.), 6 μL of Water (PCR grade), and 2 μL of genomic DNA sample in a total reaction volume of 20 μL using the FastStart Essential DNA Probes Master kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The 2-step amplification cycling conditions were: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. VIC (victoria) and FAM (fluorescein) fluorescence data were analyzed under Endpoint Genotyping using LightCycler 96 System software version 1.1.0.1320 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

Statistical analysis

We estimated that this study would require a total of 100 patients by considering loss to follow-up. Variables were examined using Fisher’s exact test or the Chi-square test. The differences between the PFS and OS in the two groups were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method and the Log-rank test. Variables identified using the univariate analysis to be significantly associated with PFS and OS were entered into the Cox proportional hazards regression model for multivariate analysis. Univariate and multivariate analyses with logistic regression models were used to calculate the OR at 95% CI to assess the correlation between the response and the NOS3 rs2070744 genotypes for lenvatinib treatment. A two-sided p value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) by the Statista Corporation (Kyoto, Japan) and Stata/MP 15.1 for Mac (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Board for Human Genome Research of the Kitasato University Medical Ethics Organization (KMEO) (Approval Number: KMEO G18-16), the Ethical committee in human genome research of the Yokohama City University (Approval Number: A190725004), and the Tokushukai Group Ethics Committee of Shonan Kamakura General Hospital and Shonan Fujisawa Tokushukai Hospital (Approval Number: TGE01429-024). The results/data/figures in this manuscript have not been published elsewhere, nor are they under consideration (from you or one of your Contributing Authors) by another publisher.

Consent for publication

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Consent to participate

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and after obtaining approval of the institutional research ethics committee and written informed consent obtained from all participants.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Robert E. Brandt, Founder, CEO, and CME, of MedEd Japan, for editing and formatting the manuscript.

Author contributions

S.A. was responsible for the concept and design, collection and assembly of data, and statistical analysis. H.U. and M.C. collected and assembled the data. H.H. and T.N. analyzed and interpreted the data. X.S., M.K., K.N., S.I., S.M., W.K., and K.A. contributed to data collection and critically reviewed the manuscript. M.K. was the general director of the study group. All authors read and gave final approval to the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset are available from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

4/14/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-021-86457-y

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-73930-3.

References

- 1.Kudo M. Extremely high objective response rate of lenvatinib: its clinical relevance and changing the treatment paradigm in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2018;7:215–224. doi: 10.1159/000492533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kudo M. Proposal of primary endpoints for TACE combination trials with systemic therapy: lessons learned from 5 negative trials and the positive TACTICS trial. Liver Cancer. 2018;7:225–234. doi: 10.1159/000492535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391:1301–1314. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kudo M. Lenvatinib may drastically change the treatment landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2018;7:1–19. doi: 10.1159/000487148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kudo M, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CH, et al. Distinct role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms from menopausal status in the patients with sporadic breast cancer in Taiwan. Nitric Oxide. 2018;72:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casadei Gardini A, et al. eNOS polymorphisms and clinical outcome in advanced HCC patients receiving sorafenib: final results of the ePHAS study. Oncotarget. 2016;7:27988–27999. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marisi G, et al. ANGPT2 and NOS3 polymorphisms and clinical outcome in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving sorafenib. Cancers (Basel) 2019 doi: 10.3390/cancers11071023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziche M, Morbidelli L. Molecular regulation of tumour angiogenesis by nitric oxide. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2009;20:164–170. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2009.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diler SB, Öden A. The T-786C, G894T, and intron 4 VNTR (4a/b) polymorphisms of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene in prostate cancer cases. Russ. J. Genet. 2016;52:220–225. doi: 10.1134/s1022795416020022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safarinejad MR, Safarinejad S, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. Effects of the T-786C, G894T, and Intron 4 VNTR (4a/b) polymorphisms of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene on the risk of prostate cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2013;31:1132–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casadei Gardini A, et al. Association of NOS3 and ANGPT2 gene polymorphisms with survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma receiving sorafenib: results of the multicenter prospective INNOVATE study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohya K, et al. Early changes in ammonia levels and liver function in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated by lenvatinib therapy. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:12101. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48045-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hidaka H, et al. Portal hemodynamic effects of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective cohort study. J. Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1030–1035. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0563-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hidaka H, et al. Portal hemodynamic effects of lenvatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Hepatol. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1111/hepr.13531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheu MJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 polymorphism is associated with liver cirrhosis in hepatocarcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0122961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma Z, et al. Polymorphisms of fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 have association with the development of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia and the progression of prostate cancer in a Japanese population. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;123:2574–2579. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao L, Shay C, Lv F, Wang X, Teng Y. Implications of FGF19 on sorafenib-mediated nitric oxide production in hepatocellular carcinoma cells: a short report. Cell Oncol. (Dordr) 2018;41:85–91. doi: 10.1007/s13402-017-0354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho HK, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 regulates proliferation, anti-apoptosis and alpha-fetoprotein secretion during hepatocellular carcinoma progression and represents a potential target for therapeutic intervention. J. Hepatol. 2009;50:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guagnano V, et al. FGFR genetic alterations predict for sensitivity to NVP-BGJ398, a selective pan-FGFR inhibitor. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:1118–1133. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao L, et al. FGF19/FGFR4 signaling contributes to the resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma to sorafenib. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;36:8. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0478-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tovar V, et al. Tumour initiating cells and IGF/FGF signalling contribute to sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2017;66:530–540. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang HM, Tian G, Zhou LJ, Zhou HY, Fang YZ. FGFR4 genetic polymorphisms determine the chemotherapy response of Chinese patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013;34:549–554. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Yu W, Cai Y, Ren C, Ittmann MM. Altered fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 stability promotes prostate cancer progression. Neoplasia. 2008;10:847–856. doi: 10.1593/neo.08450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakayama M, et al. T-786–>C mutation in the 5'-flanking region of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene is associated with coronary spasm. Circulation. 1999;99:2864–2870. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.22.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagassaki S, et al. eNOS genotype is without effect on circulating nitrite/nitrate level in healthy male population. Thromb. Res. 2005;115:375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senthil D, et al. Genotype-dependent expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and its regulatory proteins in cultured endothelial cells. DNA Cell Biol. 2005;24:218–224. doi: 10.1089/dna.2005.24.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Granito A, et al. Prognostic significance of adverse events in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2016;9:240–249. doi: 10.1177/1756283X15618129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, et al. Incidence and risk of sorafenib-induced hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014;16:177–185. doi: 10.1111/jch.12273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu S, Chen JJ, Kudelka A, Lu J, Zhu X. Incidence and risk of hypertension with sorafenib in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:117–123. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimose S, et al. clinical significance of adverse events for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib: a multicenter retrospective study. Cancers (Basel) 2020 doi: 10.3390/cancers12071867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiraoka A, et al. Prognostic factor of lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in real-world conditions—multicenter analysis. Cancer Med. 2019;8:3719–3728. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamnvik OP, et al. Clinical risk factors for the development of hypertension in patients treated with inhibitors of the VEGF signaling pathway. Cancer. 2015;121:311–319. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bair SM, Choueiri TK, Moslehi J. Cardiovascular complications associated with novel angiogenesis inhibitors: emerging evidence and evolving perspectives. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2013;23:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell JA, Ali F, Bailey L, Moreno L, Harrington LS. Role of nitric oxide and prostacyclin as vasoactive hormones released by the endothelium. Exp. Physiol. 2008;93:141–147. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.038588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kappers MH, et al. Hypertension induced by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib is associated with increased circulating endothelin-1 levels. Hypertension. 2010;56:675–681. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.149690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ancker OV, Wehland M, Bauer J, Infanger M, Grimm D. The Adverse effect of hypertension in the treatment of thyroid cancer with multi-kinase inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017 doi: 10.3390/ijms18030625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.European Association for the Study of the Liver Electronic address, e. e. e. & European Association for the Study of the, L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen LT, et al. Pan-Asian adapted ESMO clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with intermediate and advanced/relapsed hepatocellular carcinoma: a TOS-ESMO initiative endorsed by CSCO, ISMPO, JSMO, KSMO, MOS and SSO. Ann. Oncol. 2020;31:334–351. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kudo M, et al. Lenvatinib as an initial treatment in patients with intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma beyond up-to-seven criteria and child-pugh a liver function: a proof-of-concept study. Cancers (Basel) 2019 doi: 10.3390/cancers11081084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kudo M. A new treatment option for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma with high tumor burden: initial lenvatinib therapy with subsequent selective TACE. Liver Cancer. 2019;8:299–311. doi: 10.1159/000502905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uojima H, et al. Skeletal muscle mass influences tolerability and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with lenvatinib. Liver Cancer. 2020;9:193–206. doi: 10.1159/000504604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin. Liver Dis. 2010;30:52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset are available from the corresponding author.