Although 8–20% of patients are reported to carry a penicillin allergy label (PAL), more than 95% of these individuals will be negative on standardized penicillin allergy (PA) testing1–3. Patients with a PAL are subject to adverse health outcomes, including increased nosocomial infections, surgical site infections, prolonged time to administration of emergent antibiotics, prolonged hospitalizations, and hospital readmissions4–6. PA testing has been shown to be safe, facilitates antibiotic stewardship, and data suggests it is likely to be cost effective1,7,8. While much is published regarding the worse outcomes of a PAL and approaches to remove a PAL9, little is known about PA patients’ willingness to undergo PA testing. Therefore, we conducted the “Readiness for PENicillin allergy testing: Perception of Allergy Label (PEN-PAL)” survey to ascertain beliefs, perceptions, and experiences of a current self-reported PA patient population and to identify potential barriers to testing.

A survey (Figure E1 in the Online Repository) was created using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), an established secure web-based application for creating and managing online surveys and databases. Of note, the only mandatory question was whether the patient reported either a current penicillin allergy, reported a historical penicillin allergy which was removed, or reported no penicillin allergy. The participants were free to omit answers to all other questions if they did not recall the answer or if they chose not to answer, and thus, the denominator of responses varied slightly by question. An email with the survey was sent to 18,943 adult patients (≥18 years of age) pre-consented to receive IRB-approved study advertisements in the context of the MyResearch at Vanderbilt (MRAV) program, with three reminder emails, from late October 2019 to early December 2019. Additional details regarding REDCap and MRAV can be found in the EMethods in the Online Repository.

For continuous variables, median and interquartile range were calculated. Statistical comparisons were performed between the three penicillin allergy status groups. For categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test or Pearson’s chi-squared statistic were used. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare continuous variables. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 15.0.

18,943 eligible participants of MRAV, 5284(28%) completed the survey. 1047(20%) reported a current PA, 4091(77%) reported no PA, and 146(3%) reported a historical PA which was removed. Participants reporting a current PA were more likely to be female (Pearson, P<0.005) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographics of PEN-PAL Survey Participants

| Demographic | No Penicillin Allergy (n=4091) | Current Penicillin Allergy (n=1047) | Removed Penicillin Allergy (n= 146) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age [IQR] | 62 [51–70] | 61 [51–69] | 64 [51–71] | NS |

| Gender No. (%) | ||||

| Male | 1599 (39) | 275 (26) | 45 (31) | <0.005 |

| Female | 2464 (60) | 769 (73) | 99 (68) | |

| Other | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Declined to answer | 26 (1) | 3 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Race No. (%) | ||||

| White | 3720 (92) | 972 (93) | 136 (93) | NS |

| African American | 167 (4) | 44 (4) | 3 (2) | |

| Other | 177 (4) | 26 (2) | 7 (5) | |

| Declined to answer | 27 (1) | 5 (0) | 0 (0) |

Patients reporting a current PAL experienced their index reaction at a median age of 16 [IQR 6–30] with most reactions occurring ≥10 years ago (915/1040, 88%). The three most common types of reactions were rash only (510/1037, 49%), an unknown reaction (141/1037, 14%), or “anaphylaxis” (139/1037, 13%), and all reactions recalled are detailed in Table E1 in the Online Repository. Of the 116/998(12%) who endorsed receiving epinephrine, 77(66%) recalled the index reaction of “anaphylaxis” and 39(34%) received epinephrine but didn’t recall the index reaction of “anaphylaxis.” Following the index reaction, of those who recalled their highest level of care required (805/1034, 78%), most required only an outpatient visit, phone call, or self-discontinued penicillin (612/805, 76%), while few utilized the emergency department (106/805, 13%), inpatient floor (62/805, 8%), or the intensive care unit (17/805, 2%).

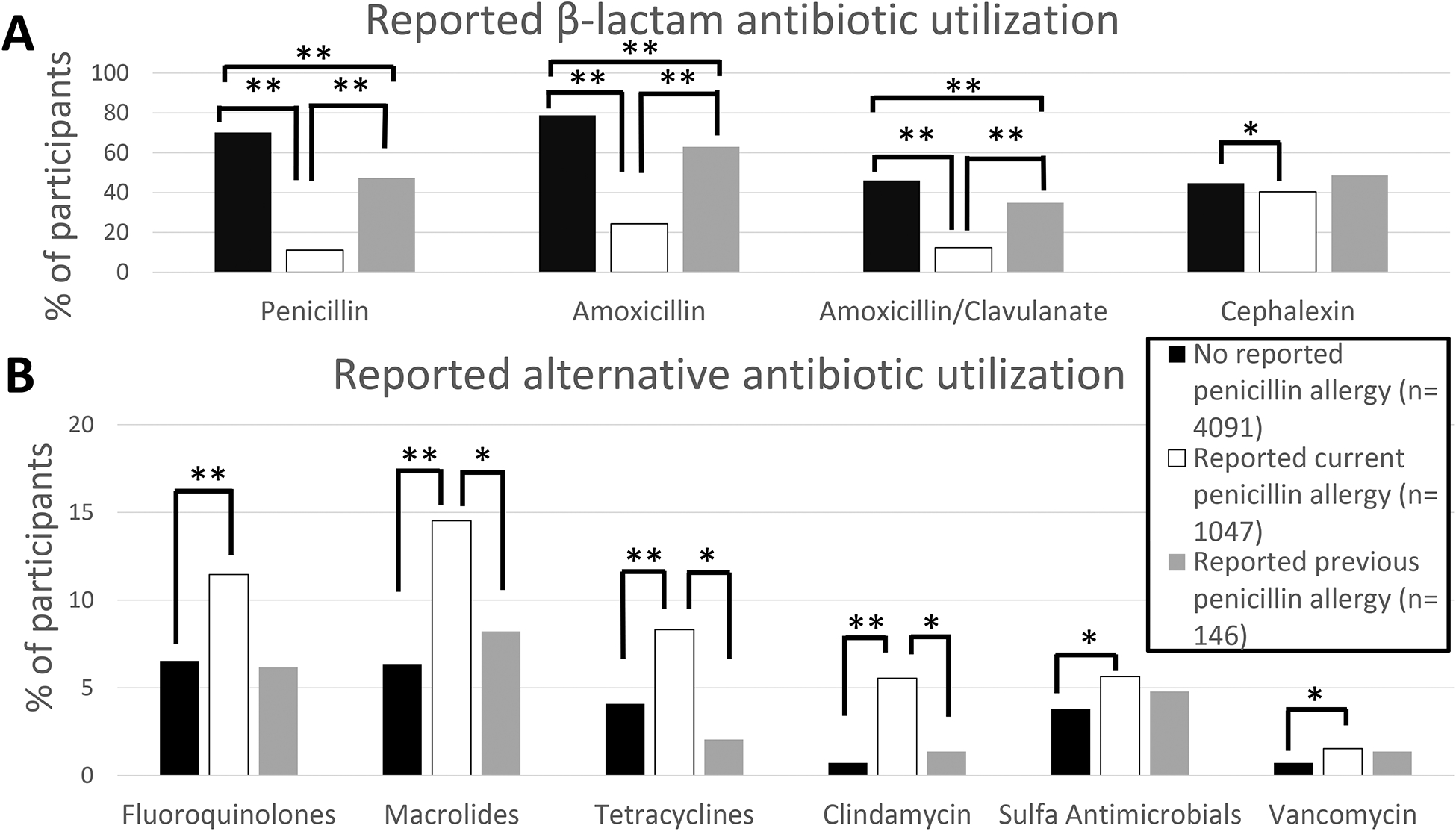

Antibiotic utilization differed among those reporting a current PA and the other groups (Figure 1). Compared to no reported PA, participants reporting a current PA less frequently recalled receiving penicillin** (subsequent to index reaction) (11% vs 70%), amoxicillin** (24% vs 79%), amoxicillin/clavulanate** (12% vs 46%), and cephalexin* (40% vs 45%), and more frequently recalled receiving fluoroquinolones** (11% vs 7%), macrolides** (15% vs 6%), tetracyclines** (8% vs 4%), clindamycin** (6% vs 1%), sulfa antimicrobials* (6% vs. 4%), and vancomycin* (2% vs 1%) (Pearson chi-squared *P<0.05, **P<0.005). Compared to participants reporting a historical PA which was removed, participants reporting a PA less frequently recalled receiving penicillin** (subsequent to index reaction) (11% vs 47%), amoxicillin** (24% vs 63%), and amoxicillin/clavulanate** (12% vs 35%), and more frequently recalled receiving clindamycin* (11% vs 6%), tetracyclines* (8% vs 2%), and macrolides* (15% vs 8%) (Fisher’s exact test *P<0.05, **P<0.005) (Figure 1). Furthermore, 198/1040(19%) with a PAL had taken and tolerated a penicillin, but continued to self-report their PAL.

Figure 1: Reported antibiotic utilization, by penicillin allergy status.

A) Participants reporting a current PA less frequently reported utilization of penicillin** (after index reaction, when applicable), amoxicillin**, amoxicillin/clavulanate**, and cephalexin*. B) Participants reporting a current PA more frequently reported utilization of fluoroquinolones**, macrolides**, tetracyclines**, clindamycin**, sulfa antimicrobials*, and vancomycin* (* P<0.05, ** P<0.005, no bar= NS).

Participants reporting a current PA often discussed their PA with a primary care provider (639/1035, 61%), but that conversation rarely comprised of the negative consequences of a PA (73/1040, 7%), and the minority were offered referral to an allergist for PA testing (38/1040, 4%). Regarding surgeries in PA patients, 869/1039(81%) reported both a PA and a surgery since their index reaction, and majority of these (747/861, 87%) had a pre-operative discussion of their PA with a provider. The minority of these participants perceived their PA had an adverse effect on their medical care (167/1040, 16%). Most (799/989, 81%) believed their PA to be permanent, and many believed it “likely” or “very likely” to react to penicillin today (397/1039, 38%). Despite this, a high proportion (813/1016, 80%) would take penicillin for an indicated cause if an allergist tested them and found it to be safe. Overall, 561/1024 (55%) were interested in PA testing.

This survey is the first which attempts to capture a large population-based sample of attitudes and experiences of a current reported PA patient, and while the survey link was only sent to those accessing care at a tertiary medical center, we believe that the conclusions are generalizable to a population level. Limitations of the study which we do not believe will significantly change conclusions are that many of the answers involve the participants recollection of reaction details and medications, and we did not ask the participants whether they had other antibiotic allergies, which may independently alter the antibiotics received.

We identified educational points for both patients and providers. Notably, >80% of those with a current PA perceived their PA as permanent. However, if the reported histories of rash only, “my family member told me I’m allergic but I don’t recall,” gastrointestinal distress, unknown history, and family history of penicillin allergy were applied to a recently validated penicillin allergy risk stratification scheme9,10, 71% of our PA participants’ reported histories would be categorized as low risk, and thus likely to tolerate a single-dose amoxicillin oral challenge today. Most (561/1024, 55%) with a current PAL were interested in PA testing, and the majority (813/1016, 80%) indicated they would take a penicillin if testing was negative. Despite this, primary care doctors rarely referred our participants for PA testing (38/1040, 4%).

Self-reported antibiotic utilization was different between those with and without a current PAL. PAL participants recalled significantly fewer β-lactam prescriptions and increased prescriptions of antibiotics associated with potentially reduced treatment efficacy. Those with a current PAL also recalled fewer β-lactam prescriptions than those with a historical PAL which was removed, highlighting the importance of PAL testing in guiding antibiotic prescribing patterns.

PAL patients believed their PAL to be permanent and several retained a PAL despite proven tolerance. Although they expressed interest in formal allergy assessment, and most would take penicillin if tested negative, they were rarely referred, leading to differential antibiotic utilization in favor of broader spectrum and potentially less effective therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Douglas Conway, BA and James Ryan Moore, BS of the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research of Vanderbilt University Medical Center for their effort in survey distribution.

Funding Sources

Dr. Coleman received a Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (VICTR) grant #53885

Dr. Stone receives funding from AHRQ K12 HS026395.

Dr. Wei receives funding from NIH NHLBI 1R01HL133786

Dr. Phillips receives funding National Institutes of Health (1P50GM115305-01, R21AI139021 and R34AI136815 and 1 R01 HG010863-01) and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia)

This project was supported by CTSA award No. UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest directly related to this manuscript

Clinical Implications: Patients reporting penicillin allergy believe their allergy to be permanent, would take penicillins if tested negative, but are rarely referred for penicillin testing, leading to differential antibiotic utilization.

References:

- 1.Trubiano J, Adkinson N, Phillips E. Penicillin Allergy Is Not Necessarily Forever. Jama. 2017;318(1):82–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penicillin Macy E. and beta-lactam allergy: epidemiology and diagnosis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(11):476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint Task Force on Practice P, American Academy of Allergy A, Immunology, et al. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(4):259–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenthal K, Ryan E, Li Y, Lee H, Kuhlen J, Shenoy E. The Impact of a Reported Penicillin Allergy on Surgical Site Infection Risk. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018;66(3):329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conway E, Lin K, Sellick J, Kurtzhalts K, Carbo J, Ott MC, et al. Impact of Penicillin Allergy on Time to First Dose of Antimicrobial Therapy and Clinical Outcomes. Clinical therapeutics. 2017;39(11):2276–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumenthal K, Li Y, Banerji A, Yun B, Long A, Walensky R. The Cost of Penicillin Allergy Evaluation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):1019–1027 e1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattingly T 2nd, Fulton, Lumish R, Williams AMC, Yoon S, Yuen M, et al. The Cost of Self-Reported Penicillin Allergy: A Systematic Review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(5):1649–1654 e1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone C Jr., Trubiano J, Coleman D, Rukasin C, Phillips E The challenge of de-labeling penicillin allergy. Allergy. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone C Jr., Stollings J, Lindsell C, Dear ML, Buie RB, Rice TW, et al. Risk-Stratified Management to Remove Low-Risk Penicillin Allergy Labels in the Intensive Care Unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.