Abstract

There is significant variability in the type and severity of symptoms reported by individuals diagnosed with binge-eating disorder (BED). Using latent class analysis (LCA), the current study aimed to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity among individuals with BED. Participants were 775 treatment-seeking adults with DSM-IV-defined BED. Doctoral research clinicians reliably assessed participants for BED and associated eating-disorder psychopathology using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders and the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) interview, measured weight and height, and participants completed a battery of self-report measures. Based on fit statistics and class interpretability, a 2-class model yielded the best overall fit to the data. The two classes were most distinct with respect to differences in body image concerns, distress about binge-eating, and depressive symptomology. Number of binge episodes were significantly different between classes, though the effect was much smaller. Body mass index was not a significant indicator or covariate in the majority of models. The results show that many of the features currently used to define BED (e.g., binge-eating frequency) are not helpful in explaining heterogeneity among individuals with BED. Instead, body image disturbances, which are not currently included as a part of the diagnostic classification system, appear to differentiate distinct subgroups of individuals with BED. Future research examining subgroups based on body image could be integral to resolving ongoing conflicting evidence related to the etiology and maintenance of BED.

Keywords: binge-eating disorder, latent class analysis, diagnosis, obesity, body image, empirical classification

Introduction

Binge-eating disorder (BED) was formally recognized in the most recent edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostics and Statistical Manual 5th edition (DSM-5; APA; 2013), and the next version of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) will also include BED as a formal condition (Stein et al., 2020). BED is prevalent and associated strongly with severe obesity and with significant psychiatric and medical comorbidity (Udo and Grilo, 2018; Udo and Grilo, 2019), including increased risk for suicide (Udo et al., 2019). BED is also associated with significant functional impairment, productivity loss, and higher health care utilization and cost (Ling et al., 2017).

BED, like all psychiatric disorders is polythetic, which contributes to substantial heterogeneity in clinical presentation. Moreover, there has been significant ongoing debate about correlates of BED not currently included as a part of the diagnostic system, including dietary restraint, body-image disturbances, and body mass index. Some studies of clinical, and less-often, community samples demonstrate elevated levels of dietary restraint among individuals with BED (Peterson et al., 2013; Wilfley et al., 2000). Other studies fail to replicate this finding (Masheb and Grilo, 2000). In contrast, the majority of research supports elevated levels of body image concerns as compared with samples with normal weight, overweight, or obesity (Ahrberg et al., 2011), and undue influence of body weight on self-evaluation (i.e., overvaluation) is strongly associated with increased psychopathology and BED severity (Goldschmidt et al., 2010; Ojserkis et al., 2012). Finally, body mass index is correlated with binge eating (Guss et al 2002) and BED is associated strongly with severe obesity (Guss et al., 2002; Udo and Grilo, 2018) although BMI has generally not predicted treatment outcomes (Grilo et al., 2012b; Munsch et al., 2012).

Arguably the best approach to understanding heterogeneity within diagnostic classes is latent class analysis (LCA). LCA describes a family of analytic strategies generally aimed at finding the smallest number of groups (i.e., latent classes) that best describe the associations among a set of observed indicators, such that individuals in one class are similar to one another but are distinct from individuals in other classes (Moss et al., 2007). LCA has been used previously in studies of eating disorder patients broadly, which tend to identify a binge eating class independent of other types of classes (e.g., Forbush and Wildes, 2017; Swanson et al., 2014) and in distinguishing BED from other psychiatric (e.g., anxiety and mood) disorders (Hilbert et al., 2011). Two major studies that have examined the structure of eating disorders applied LCA (Bulik et al., 2000; Keel et al., 2004). In a study with a combined sample of probands and affected relatives examining anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and eating disorder not otherwise specified, Keel and colleagues (2004) reported four latent classes, which differed based on psychiatric disorder comorbidity, obsessive compulsive features, and the presence/type of weight-compensatory behaviors. Bulik et al. (2000), in a large community sample, reported a six-class solution, including one class that partly resembled BED, although it had low rates of loss of control and obesity.

To date, there have only been two studies using LCA among samples of individuals exclusively with BED. Peterson and colleagues (2013) completed LCA with a sample of 259 individuals with BED. The authors found evidence to support a three-class solution, which included a group with high dietary restraint, a group with low dietary restraint, and a group with high dietary restraint plus other types of psychopathology, including high levels of overvaluation. Sysko and colleagues (2010) also conducted LCA with 205 treatment seeking BED individuals and found evidence to support a four-class model. The solution included one class that potentially migrated from other types of eating disorders, with the highest proportion of individuals with a prior non-BED eating disorder diagnosis, the lowest BMI, and the highest level of physical activity. Class 2 represented a severe variant of BED, with the most frequent binge eating and highest level of eating disorder psychopathology, including compensatory behaviors. Class 3 was similar to Class 2, but individuals in this class did not demonstrate elevated levels of compensatory behaviors. The fourth and final class was phenotypically most similar to individuals with obesity, including demonstrating elevated BMI and overeating episodes and fewer or lower severity eating disorder symptoms. The mixed findings from the only two available studies that applied LCA to BED data highlight the need for further research. The present study aimed to build on the two existing studies and to examine heterogeneity of BED in a large, diverse treatment-seeking group of patients at one research center using rigorous, psychometrically improved interview-based assessments of key eating-disorder psychopathology variables. We hypothesized that cognitive and psychological correlates, rather than behavioral features (e.g., OBEs) or physical correlates (e.g., BMI) of BED, would best discriminate between latent classes.

Methods

Procedures

Participants were treatment-seeking men and women with BED evaluated for treatment studies testing pharmacological, psychological, and/or behavioral treatments for BED at an urban, medical-school based program in the northeastern United States. Respondents to media recruitments for treatment studies were screened by telephone and, if potentially eligible and interested in treatments for BED, were scheduled for in-person intake assessment with a research-clinician. All research clinicians were doctoral-level, experienced with eating/weight disorders, had additional specific training using the study’s assessment protocols. This study was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study design and implementation were reviewed by the university’s ethical review committee, and all enrolled participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Participants (N = 775) were aged 18 – 65 years and met full DSM-IV (2000) criteria for BED. Participants were excluded if they were receiving concurrent treatment (psychosocial or pharmacological) for eating/weight concerns, had medical conditions that influenced eating/weight (e.g., uncontrolled hypothyroidism), were taking medications that could influence eating/weight, had a severe mental illness that could interfere with assessment and treatment (e.g., psychosis), or were pregnant. In line with DSM-IV (2000) diagnostic criteria for BED, participants who endorsed regular compensatory behaviors were excluded (e.g., twice a week), though irregular or infrequent compensatory behaviors were not considered exclusionary for the primary analyses (a parallel series of secondary analyses excluding such cases are described below). Participants had a mean age of 45.59 years (SD = 9.85) and a mean BMI of 38.08 kg/m2 (SD = 6.80). Participants were primarily female (n = 576; 74.3%) and most had some college or higher education (n = 622; 80.88%). The racial-ethnic distribution of the sample was: White (n = 568; 73.5%), Black (n = 121; 15.7%), Hispanic (n = 54, 7.0%), and 30 (3.9%) individuals identified as biracial, multiracial, or “Other” racial group.

Procedures

Trained and monitored (to maintain reliability and prevent drift) research clinicians administered two semi-structured interviews (described below) to determine DSM-IV-defined BED diagnosis, to assess eating-disorder psychopathology, and to assess historical variables. Height and weight were measured during the evaluation process and used to calculate body mass index (BMI). Participants completed self-report inventories.

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (First et al., 1997), a structured diagnostic interview for psychiatric disorders, was administered to determine the BED diagnosis. For the current study, diagnostic information regarding anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa was also used.

Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) Interview (Fairburn and Cooper, 1993), is a semi structured, investigator-based interview, was used to confirm the SCID-IV-informed diagnosis of BED and to assess the features of eating-disorder psychopathology (Grilo et al., 2004; Grilo et al., 2001a). The EDE assesses the frequency of overeating behaviors, including objective binge-eating episodes (OBE, i.e., eating an unusually large amount of food while feeling a sense of loss of control; this corresponds to the DSM-based definitions of binge eating), subjective binge-eating episodes (SBE, i.e., eating that includes a sense of loss of control and does not include consuming an unusually large amount of food), and purging/compensatory behaviors (e.g., vomiting, laxative misuse, or compulsive exercise). The EDE also assesses cognitive and behavioral features of eating-disorder psychopathology and comprises four subscales (restraint, shape concern, weight concern, and eating concern) and a “global” or total score; all these items are rated using a 7-point scale (0-6) with higher scores reflect greater severity/frequency.

We note that the present study used an alternative three-scale structure (dietary restraint, dissatisfaction with weight/shape, and overvaluation of weight/shape) which recent research has reliably found to demonstrate superior psychometric properties for patients with BED (Grilo et al., 2010) as well as across diverse clinical (eating disorders, obesity) and non-clinical samples (Grilo et al., 2012a; Grilo et al., 2013; Grilo et al., 2015; Machado et al., 2018). This decision was further indicated by the underlying assumptions related to LCA, which include independence of indicators beyond the covariance caused by latent class membership, which raised issues for the original EDE structure because of the high correlation between weight and shape concerns (Grilo et al., 2010). Interrater reliability examined on a portion (n =37) of this study’s sample revealed very strong to excellent intraclass correlations for the alternative three scales: dietary restraint (.882), overvaluation (.902), and dissatisfaction (.838).

Interviewers also rate the patient’s level of distress related to the binge-eating behavior (OBE) and the sum of the number of “loss of control” indicators specified by the DSM-IV and DSM-5 (i.e., eating rapidly; eating until uncomfortably full; eating large amounts when not physically hungry; eating alone because of embarrassment about eating; and feeling disgusted, depressed, or very guilty following an episode) was also used.

Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., 1987) is a well-established, widely used measure of depressive symptoms and levels with demonstrated excellent psychometric properties (Beck et al., 1988). The BDI taps a broad range of negative affective, not just depressive affect, and correlates strongly with broad psychopathology (Grilo et al., 2001b; Ivezaj, Barnes, & Grilo, 2016). In the present study, we included BDI scores in the models rather than major depression disorder diagnosis (based on the SCID-I/P) given findings that the BDI has superior value for identifying clinical severity in individuals with BED (Grilo et al., 2001b) and obesity (Ivezaj et al., 2016) and for predicting treatment outcomes for BED (Grilo et al., 2012b). In the present study, internal consistent alpha was 0.88.

Body Mass Index (BMI).

BMI was calculated based on measured height and weight at the time of the intake assessment.

Statistical Analyses

Variables of interest were checked for the presence of outliers and non-normality. Variables related to binge eating (OBE and SBE) indicated positive skew and several outliers. A logarithmic transformation was attempted but it did not significantly improve skew statistics. Outlying cases were visually inspected, and they were determined to likely be part of the existing population and the decision was made to retain the cases. Analyses were re-run with outlying OBE cases censored to 2 standard deviations above the mean. Fit statistics did not support a different solution with this adjustment, and as such, data is reported without censoring. All other interval variables were determined to be approximately normal.

LCA models were estimated using Mplus Version 8.3 using full information maximum likelihood with robust standard errors. In the total sample, 86.84% had complete data and the majority of the remaining sample was missing information on only a single variable (10.45%). LCA included continuous and categorical indicators using the approach outlined by Asparouhov and Muthen (2012) and MPlus Version 8.3. The objective of LCA is to find the smallest number of groups (i.e., latent classes) that best describe the associations among a set of observed indicators, such that individuals in one class are similar to one another but are distinct from individuals in other classes (Moss et al., 2007). The following continuous variables were entered in the models: dietary restraint, overvaluation of weight and shape, dissatisfaction with weight and shape, objective binge-eating episodes, subjective binge-eating episodes, the number of loss of control indicators endorsed, distress related to objective binge-eating episodes, and depression (BDI) scores. The following categorical variables were also included in the model: a history of either anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa and report of any type of compensatory behavior in the 28 days prior to intake. The following covariates were included: gender, education, race, age, and BMI.

LCA procedures were completed iteratively, fitting two through five-class models and comparing models using relative and inferential fit indices, including Bayesian information criterion (BIC), sample size adjusted BIC (aBIC), the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio (LRM) test, and the bootstrapped likelihood ratio tests (BLRT). Lower values for BIC and aBIC indicate better fit, whereas a significant loglikelihood ratio test for either the Vuong-Lo-Mendell Rubin and BLRT indicate that the model including more classes is a better fit. In line with the suggestions outline by Asparouhov and Muthén (2012), the number of random starts was increased iteratively, such that the best replicated loglikelihood ratio test for a given class solution was rerun with twice the number of random starts to confirm replication. In addition to fit statistics class-size, class homogeneity, and interpretability of classes were considered were deriving the solution. Following identification of solution individuals were assigned a class based on their most likely class membership and mean differences were compared controlling for covariates using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Notably in these models, the homogeneity of variance assumption was violated. Analyses were completed again using robust estimation of quality of means or Welch’s F, which does not allow for inclusion of covariates. Results remained the same. Because the differences between groups not accounted for by the covariates was the primary interest, results are reported from ANCOVA analyses. Additionally, the analyses (LCA and ANCOVA) were repeated with N=45 participants excluded who reported compensatory behaviors in the past 28 days.

Results

Table 1 includes a description of the total sample, including demographic and clinical characteristics. Table 2 summarizes the two- through five-class solutions, including the descriptive and inferential fit statistics. The various fit indices do not converge on a single solution, with BIC and aBIC supporting the five-class solution as the best model, the LMR test supporting the two-class solution, and the BLRT supporting a three-class solution. Though the data are limited at this time, a simulation study identified LMR and especially BLRT as superior in identifying the correct solution as compared with BIC and aBIC(Nylund et al., 2007; Tein et al., 2013). As such, the two and three-class solutions were examined more closely. The two- and three-class solutions were highly similar; each solution contained a class with subclinical levels of overvaluation and dissatisfaction and a class or classes with clinical levels of overvaluation and dissatisfaction. The most significant difference between the two- and three-class solutions was the inclusion of a class with significantly more subjective binge-eating episodes in the three- class solution. Given the minimal differences, the decision was made to retain a two-class solution and further investigate the defining features and the relative importance of covariates.

Table 1.

Total Sample (N = 775) Sociodemographic, Psychiatric, and Eating Disorder Symptomology

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 199 (25.68) |

| Female | 576 (74.32) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 568 (73.48) |

| Black | 121 (15.65) |

| Hispanic | 54 (6.99) |

| Other | 30 (3.88) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| HS or less | 147 (19.12) |

| Some college | 271 (35.24) |

| College or higher | 351 (45.64) |

| Eating Disorder History, n (%) | |

| No History | 683 (94.47) |

| Positive History | 40 (5.53) |

| Current Compensatory Behaviors, n (%) | |

| None | 730 (94.19) |

| 1 or more | 45 (5.81) |

| Age, M(SD) | 45.59 (9.85) |

| BMI, M(SD) | 38.08 (6.80) |

| EDE Dietary Restraint, M(SD) | 1.78 (1.35) |

| EDE Overvaluation, M(SD) | 3.64 (1.75) |

| EDE Dissatisfaction, M(SD) | 4.76 (1.08) |

| Objective Binge-Eating Episodes, M(SD) | 18.69 (12.95) |

| Subjective Binge-Eating Episodes, M(SD) | 7.97 (13.11) |

| Depression (BDI) Scores, M(SD) | 16.28 (9.10) |

Notes. HS: High School; Bx: Behavior; EDE: Eating disorder examination interview.

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Latent Class Models

| Class type | BIC | aBIC | Entropy | Lo-Mendel Rubin testa | BLRTa Replicated | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-class | 29834.876 | 29726.911 | 0.747 | p < 0.001 | Yes | p < 0.001 |

| Three-class | 29623.350 | 29464.578 | 0.817 | p = 0.255 | Yes | p < 0.001 |

| Four-classb | 29499.492 | 29289.913 | 0.844 | p = 0.132 | No | NA |

| Five-Classb | 29477.808 | 29217.422 | 0.784 | p = 0.698 | No | NA |

Notes. AIC: Akaike information Criterion, BIC: Bayesian information criterion, aBIC: sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion. BLRT: Bootstrapped Ratio Likelihood Test.

a significant result indicates that the solution with the higher number of classes is a better fit

For BLRT testing, attempts were made to increase the LRTSTARTS, default is 20 and 5, successive runs were tried up to 1000 and 400.

Table 3 reports the means and standard errors for continuous indicators of the two-class solution as well as the proportion of each class endorsing a history of either anorexia or bulimia or reporting at least one compensatory behavior in the last 28 days. Class 1 reported subclinical levels of dietary restraint, overvaluation, dissatisfaction, and depression. Class 1 was very unlikely to report a non-BED eating disorder history or compensatory behaviors. In contrast, Class 2 endorsed clinical levels of overvaluation, dissatisfaction, and depression. Due to the additional features, this class was conceptualized as a BED class with cognitive and depressive symptoms (BED+Cog/Dep class), while Class 1 was understood simply as the BED class. While a history of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa and current compensatory behaviors remained relatively uncommon in the BED+Cog/Dep class, it was more frequently endorsed in the BED+Dep/Cog class than the BED class. Class means were compared using ANCOVA, while controlling for BMI, age, gender, education, and race. Effect sizes indicated that body image concerns and distress related to objective binge-eating episodes explained a large proportion of the variance. Results with N=45 excluded participants who reported compensatory behaviors in the past 28 days are presented in Supplemental Tables S1 and S2. The results, including a 2-class solution and important differences between the classes, remain essentially unchanged.

Table 3.

Estimated Parameters and Mean Differences Between Classes

| Class 1 (n = 238) | Class 2 (n = 526) | Fb,c | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ma | SE | Ma | SE | ||||

| Dietary Restraint | 1.41 | 0.09 | 1.92 | 0.08 | 21.60 (1, 756) | p < .001 | 0.028 |

| Overvaluation | 2.26 | 0.10 | 4.26 | 0.08 | 302.51(1, 756) | p < .001 | 0.286 |

| Dissatisfaction | 3.78 | 0.06 | 5.06 | 0.05 | 307.75 (1, 756) | p < .001 | 0.289 |

| Objective Binge-Eating Episodes | 17.34 | 0.90 | 21.11 | 0.75 | 12.66 (1, 756) | p < .001 | 0.016 |

| Subjective Binge-Eating Episodes | 7.75 | 0.90 | 9.78 | 0.76 | 3.52 (1, 756) | p = .061 | 0.005 |

| Loss of control | 3.71 | 0.06 | 4.44 | 0.05 | 104.34 (1, 714) | p < .001 | 0.128 |

| Distress About Binge Eating | 3.18 | 0.05 | 4.43 | 0.04 | 454.03 (1, 740) | p < .001 | 0.380 |

| Depression (BDI) Scores | 10.35 | 0.56 | 19.46 | 0.47 | 189.36 (1, 752) | p < .001 | 0.201 |

| % Class | SE | % Class | SE | ||||

| Positive AN/BN History | 1.3% | 0.01 | 7.50% | 0.01 | |||

| Current Compensatory Behaviors | 0.6% | 0.01 | 8.30% | 0.01 | |||

Notes. AN: anorexia nervosa, BN: bulimia nervosa; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory

Means are estimated marginal means controlling for age and BMI.

Race, gender, education, age, and BMI included in the model.

Levine’s test of the homogeneity of variance was violated for all variables except dietary restraint.

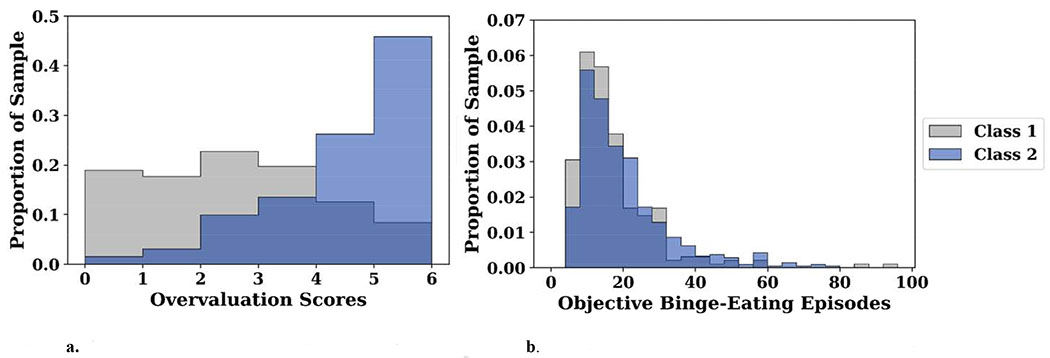

Figure 1a plots overlapping histograms based on the percentage of each class with scores on the overvaluation subscale of the EDE. The data show that there is significant separation in the distribution of scores, with the BED+Dep/Cog class shifted to the right and a significant proportion of participants in this class scoring a six, representing the most extreme value and indicating severe undue influence of shape or weight in one’s self-evaluation. In contrast, the BED class shows a more dispersed distribution, and many participants reported subclinical levels of overvaluation. The amount of variance explained by dietary restraint, objective binge-eating episodes, and subjective binge-eating episodes was proportionally very small, though the differences remain statistically significant. Figure 1b graphically presents the significant degree of overlap among the two latent classes with respect to objective-binge episodes. Overall the figures demonstrate differences in both the central tendency (i.e., mean scores) but also the dispersion of scores within the latent classes. With regard to covariates, individuals in the BED+Dep/Cog class were significantly more likely to be women (OR = 3.45, 95% CI = 2.20 - 5.42) and significantly less likely to be Black (OR = 0.519, 95% CI = 0.33 - 0.81) and significantly more likely to be younger (OR = −0.97, 95% CI 0.95 – 0.99), though the effect size for the difference in age was small. There were no significant differences between classes with respect to BMI or education.

Figure 1.

a. Distribution of Overvaluation Scores by Class. b. Distribution of Objective Binge-Eating Scores by Class.

The two classes are indicated by color, and the histograms plot the proportion of each class scoring in a given range. The darkest shading indcates overlap between the classes. That is, the proportion common to both classes scoring within that range. In Fig. 1a the data demonstrate significant seperation between classes with respect to the central tendecy as well as the overall distribution. In Fig. 1b, the data demonstrate significant overlap between classes.

Discussion

The current study used LCA to examine heterogeneity in the clinical features of eating disorder psychopathology in a large series of individuals seeking treatment for BED. Based on fit statistics and class interpretability, a 2-class model yielded the best overall fit to the data. Controlling for relevant covariates, the classes were most distinct with respect to body image concerns, distress about binge eating, and depression. The frequency of objective binge-eating episodes and BMI were relatively stable across classes. This solution aligns with accumulating evidence related to the salience of cognitive and psychological factors in understanding BED presentations and treatment needs.

The two-class solution identified in the current study is parsimonious and bears important similarities to prior work in this area. Specifically, the BED+Dep/Cog class was most similar to Class 2 described in the work by Sysko and colleagues (2010), which also found increased levels of weight and shape concerns (e.g., dissatisfaction in the current study), distress about binge eating, and depression. Moreover, our BED+Dep/Cog and the Sysko et al (2010) Class 2 showed highly similar levels of infrequent compensatory behaviors. We note here that both of these studies rigorously followed DSM-IV criteria for BED (using diagnostic interviews) and adhered to the principles of excluding “regular/recurrent” but not “infrequent” weight compensatory behaviors. We note that there can be some possible overlap in the diagnoses of BED and bulimia nervosa depending on specific aspects of changes from DSM-IV to DSM5 because the threshold for the frequency of compensatory behaviors was reduced from twice weekly (DSM-IV) to once weekly (DSM5). Thus, we performed a series of supplemental analyses with N=45 participants excluded who reported compensatory behaviors in the past 28 days and the LCA revealed a highly similar solution. Thus, changes in diagnostic nosology pertaining to the frequency of compensatory behaviors for a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa do not change the primary findings. The BED+Dep/Cog had lower rates of past eating disorder diagnoses as compared with the rates observed by Sysko and colleagues (2010), though the raw frequencies in the current study (n = 34) was significantly higher than observed in the work by Sysko and colleagues (i.e. n = 9) and may represent a more stable finding. The BED class identified in this study was most similar to Class 3 identified by Sysko et al (2010) with elevated binge-eating episodes and less severe depression and body image concerns. The only other LCA investigating BED patients identified dietary restraint as a significant defining feature of classes, with one class showing a notable absence of any dietary restraint and other classes showing higher, albeit subclinical levels of dietary restraint. In the current study, dietary restraint did not differ between classes and also fell in the subclinical range. Additional research is needed to determine whether and how dietary restraint among patients with BED contributes to heterogeneity. Finally, while epidemiologic data support a strong association between obesity and BED (Udo and Grilo, 2018), treatment research (e.g., Grilo et al., 2012b; Munsch et al., 2012) and LCA data from a large community sample (Bulik et al., 2000) fail to support the clinical or prognostic significance of weight. Future research recruiting individuals with BED with a broader range of BMI should further examine these relationships.

Study findings should be considered within the context of several potential limitations. The current study included treatment-seeking adults and the findings may not generalize to younger groups, to groups of differing sociodemographic/cultural characteristics, to non-treatment-seeking persons (see Coffino et al., 2019), or to persons who choose not to participate in research. As such, generalizability to non-treatment seeking and non-adult samples is limited. The current study also lacks external validation of latent classes. This represents an important future direction, including the stability of classes over time (whether individuals transition from one latent class to another over time) and the need to examine prospectively the potential association with treatment outcomes. Additionally, although the indicators used were based on robust research in BED literature, additional indicators could reveal additional sources of heterogeneity among patients with BED. For example, neurocognitive research related to BED and impulsivity is highly equivocal, and LCA could be helpful in illuminating reasons for conflicting findings. The assessment of depression was based on self-reported depressive symptoms, and some data suggest only moderate agreement with structured interviews for major depressive disorder among individuals with BED (Udo et al., 2015). However, data also suggests potential advantages of the BDI-II, including stronger associations with BED severity (Grilo et al., 2001b) and treatment outcomes (Grilo et al., 2012b). As such, the current data is best understood as characterizing the severity of negative affect and depression rather than identifying depressed and non-depressed individuals.

An important aim of the current work included addressing existing discrepancies in models explaining heterogeneity in BED samples. This work replicates important findings from the work by Sysko and colleagues (2010) and did not find evidence to support the importance of dietary restraint as observed in the work by Peterson et al., (2013). In addition to replicating specific findings, this work adds to the existing literature in several ways. First, the study group was relatively large. Adequate sample size when conducting latent variable analysis is important for avoiding violation of assumption local (conditional) independence and the related problem of under-extraction (Dziak et al., 2014). Additionally, although the majority of the study group identified as white and female, it was relatively diverse and included a fair number of men and substantial racial and ethnic diversity. Recent epidemiologic research indicates that prevalence rates of BED do not differ much across racial/ethnic groups (Udo and Grilo, 2018). Second, the current study utilized the alternative scoring structure for the EDE, which has shown superior psychometric properties (e.., replicable factor structure and improved internal consistency reliability) across studies and relevant subsamples BED (Grilo et al., 2010; Grilo et al., 2012a; Grilo et al., 2013; Grilo et al., 2015; Machado et al., 2018). Latent class solutions are only as valid and reliable as the indicators used to define the classes (Collins and Lanza, 2010). An improved understanding of potential BED subtypes may help refine diagnostic, etiologic, and maintenance models of BED. The current data align with research suggesting the importance of considering body image when diagnosing BED. For example, a specifier related to overvaluation has been previously suggested in the literature (Grilo, 2013), and the current data found evidence that this is a salient feature for a homogenous subgroup of individuals with BED. Subtypes may also differ in risk factors associated with developing BED or their responsiveness to treatments once diagnosed. While replication and longitudinal data are needed, future research examining subgroups based on overvaluation could be integral to improving prevention and treatment efforts for BED.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Patients with binge-eating disorder present with marked heterogeneity in symptoms

Latent class analysis was used to interrogate sources of heterogeneity

A two-class model yielded the best fit to the data

The severity of body image, distress, and depression differed between classes

Binge-eating frequency and weight were minimally different between classes

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health grant R01 DK49587 (Grilo). Dr. Grilo was also supported, in part, by NIH grants R01 DK114075, R01 DK112771, and R01 DK121551. Dr. Carr was supported by T32 DA019426. Funders played no role in the content of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. Dr. Grilo reports several broader interests which did not influence this research or paper. Dr. Grilo’s broader interests include: Consultant to Sunovion and Weight Watchers; Honoraria for lectures, CME activities, and presentations at scientific conferences and Royalties from Guilford Press and Taylor & Francis Publishers for academic books.

Data Availability Statement: Data are available from the senior author upon reasonable and explicit request.

References

- Ahrberg M, Trojca D, Nasrawi N, Vocks S, 2011. Body image disturbance in binge eating disorder: a review. Eur Eat Disord Rev 19 (5), 375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2000. Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B, 2012. Using Mplus TECH11 and TECH14 to test the number of latent classes. Mplus Web Notes 14, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer R, Brown G, 1987. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG, 1988. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review 8 (1), 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Kendler KS, 2000. An empirical study of the classification of eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry 157 (6), 886–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffino JA, Udo T, Grilo CM, 2019. Rates of help-seeking in us adults with lifetime DSM-5 eating disorders: Prevalence across diagnoses and differences by sex and ethnicity/race. Mayo Clin. Proc 94 (8), 1415–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Lanza ST, 2010. Latent class and latent transition analysis : with applications in the social behavioral, and health sciences. Wiley, Hoboken, N.J. [Google Scholar]

- Dziak JJ, Lanza ST, Tan X, 2014. Effect Size, Statistical Power and Sample Size Requirements for the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test in Latent Class Analysis. Struct Equ Modeling 21 (4), 534–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, 1993. The Eating Disorder Examination, in: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT (Eds.), Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment (12th ed.). Guilford Press, New York, pp. 317–356. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB, 1997. User's guide for the Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders SCID-I: clinician version. American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Forbush KT, Wildes JE, 2017. Application of structural equation mixture modeling to characterize the latent structure of eating pathology. International Journal of Eating Disorders 50 (5), 542–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Hilbert A, Manwaring JL, Wilfley DE, Pike KM, Fairburn CG, Striegel-Moore RH, 2010. The significance of overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy 48 (3), 187–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, 2013. Why no cognitive body image feature such as overvaluation of shape/weight in the binge eating disorder diagnosis? The International journal of eating disorders 46 (3), 208–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Crosby RD, Peterson CB, Masheb RM, White MA, Crow SJ, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE, 2010. Factor structure of the eating disorder examination interview in patients with binge-eating disorder. Obesity (Silver Spring) 18 (5), 977–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Crosby RD, White MA, 2012a. Spanish-language Eating Disorder Examination interview: factor structure in Latino/as. Eat Behav 13 (4), 410–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Henderson KE, Bell RL, Crosby RD, 2013. Eating disorder examination-questionnaire factor structure and construct validity in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg 23 (5), 657–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Crosby RD, 2012b. Predictors and moderators of response to cognitive behavioral therapy and medication for the treatment of binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 80 (5), 897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Barry DT, 2004. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination in patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 35 (1), 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, 2001a. Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder: a replication. Obesity Research 9 (7), 418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, 2001b. Subtyping binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 69 (6), 1066–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Reas DL, Hopwood CJ, Crosby RD, 2015. Factor structure and construct validity of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire in college students: further support for a modified brief version. Int J Eat Disord 48 (3), 284–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guss JL, Kissileff HR, Devlin MJ, Zimmerli E, Walsh BT, 2002. Binge size increases with body mass index in women with binge-eating disorder. Obesity Research 10 (10), 1021–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert A, Pike KM, Wilfley DE, Fairburn CG, Dohm F-A, Striegel-Moore RH, 2011. Clarifying boundaries of binge eating disorder and psychiatric comorbidity: a latent structure analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy 49 (3), 202–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivezaj V, Barnes RD, Grilo CM, 2016. Validity and Clinical Utility of Subtyping by the Beck Depression Inventory in Women Seeking Gastric Bypass Surgery. Obes Surg 26 (9), 2068–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Fichter M, Quadflieg N, Bulik CM, Baxter MG, Thornton L, Halmi KA, Kaplan AS, Strober M, Woodside DB, Crow SJ, Mitchell JE, Rotondo A, Mauri M, Cassano G, Treasure J, Goldman D, Berrettini WH, Kaye WH, 2004. Application of a latent class analysis to empirically define eating disorder phenotypes. Archives of General Psychiatry 61 (2), 192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling YL, Rascati KL, Pawaskar M, 2017. Direct and indirect costs among patients with binge-eating disorder in the United States. Int J Eat Disord 50 (5), 523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado PPP, Grilo CM, Crosby RD, 2018. Replication of a Modified Factor Structure for the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire: Extension to Clinical Eating Disorder and Non-clinical Samples in Portugal. Eur Eat Disord Rev 26 (1), 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masheb RM, Grilo CM, 2000. On the relation of attempting to lose weight, restraint, and binge eating in outpatients with binge eating disorder. Obesity Research 8 (9), 638–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi HY, 2007. Subtypes of alcohol dependence in a nationally representative sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 91 (2-3), 149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsch S, Meyer AH, Biedert E, 2012. Efficacy and predictors of long-term treatment success for cognitive-behavioral treatment and behavioral weight-loss-treatment in overweight individuals with binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy 50 (12), 775–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SB, 2019. Updates in the treatment of eating disorders in 2018: A year in review in eating disorders: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention. Eating Disorders 27 (1), 6–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthen BO, 2007. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 14 (4), 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Ojserkis R, Sysko R, Goldfein JA, Devlin MJ, 2012. Does the overvaluation of shape and weight predict initial symptom severity or treatment outcome among patients with binge eating disorder? International Journal of Eating Disorders 45 (4), 603–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Engel S, 2013. Predicting group cognitive-behavioral therapy outcome of binge eating disorder using empirical classification. Behaviour Research and Therapy 51 (9), 526–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Szatmari P, Gaebel W, Berk M, Vieta E, Maj M, de Vries YA, Roest AM, de Jonge P, Maercker A, 2020. Mental, behavioral and neurodevelopmental disorders in the ICD-11: an international perspective on key changes and controversies. BMC Medicine 18 (1), 1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson SA, Horton NJ, Crosby RD, Micali N, Sonneville KR, Eddy K, Field AE, 2014. A latent class analysis to empirically describe eating disorders through developmental stages. International Journal of Eating Disorders 47 (7), 762–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysko R, Hildebrandt T, Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras WS, 2010. Heterogeneity moderates treatment response among patients with binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 78 (5), 681–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tein J-Y, Coxe S, Cham H, 2013. Statistical power to detect the correct number of classes in latent profile analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 20 (4), 640–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo T, Bitley S, Grilo CM, 2019. Suicide attempts in US adults with lifetime DSM-5 eating disorders. BMC Med 17 (1), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo T, Grilo CM, 2018. Prevalence and Correlates of DSM-5-Defined Eating Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. Biol Psychiatry 84 (5), 345–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo T, Grilo CM, 2019. Psychiatric and medical correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States. Int J Eat Disord 52 (1), 42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo T, McKee SA, Grilo CM, 2015. Factor structure and clinical utility of the Beck Depression Inventory in patients with binge eating disorder and obesity. General Hospital Psychiatry 37 (2), 120–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Schwartz MB, Spurrell EB, Fairburn CG, 2000. Using the eating disorder examination to identify the specific psychopathology of binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders 27 (3), 259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.