Abstract

Background:

Little is known about specialist-specific variations in guideline agreement and adoption.

Objective:

To assess similarities and differences between allergists and pulmonologists in adherence to cornerstone components of the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program’s Third Expert Panel Report (EPR-3).

Methods:

Self-reported guideline agreement, self-efficacy and adherence were assessed in allergists (n=134) and pulmonologists (n=99) in the 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians.

Multivariate models were used to assess if physician and practice characteristics explained bivariate associations between specialty and “almost always” adhering to recommendations (i.e., ≥75% of the time).

Results:

Allergists and pulmonologists reported high guideline self-efficacy and moderate guideline agreement. Both groups “almost always” assessed asthma control (66.2%, SE 4.3), assessed school/work asthma triggers (71.3%, SE 3.9), and endorsed inhaled corticosteroids use (95.5%, SE 2.0). Repeated assessment of inhaler technique, use of asthma action/treatment plans and spirometry were lower (39.7%, SE 4.0, 30.6%, SE 3.6, 44.7%, SE 4.1, respectively). Compared to pulmonologists, more allergists almost always performed spirometry (56.6% vs 38.6%, P=.06), asked about nighttime awakening (91.9% vs 76.5%, P=.03) and ED visits (92.2% vs 76.5%, P=0.03), assessed home triggers (70.5% vs 52.6%, P=.06) and performed allergy testing (61.8% vs 21.3%, P<0.001). In multivariate analyses, practice-specific characteristics explained differences except for allergy testing.

Conclusions:

Overall, allergists and pulmonologists adhere to the asthma guidelines with notable exceptions, including asthma action plan use and inhaler technique assessment. Recommendations with low implementation offer opportunities for further exploration and could serve as targets for increasing guideline uptake.

Keywords: Self-efficacy, spirometry, NAEPP, agreement, inhaler technique, asthma treatment plan

Introduction

Practice guidelines can improve both the process and outcomes of care and have been available for asthma since 1991. The most recent complete update from 2007, the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program’s (NAEPP) Third Expert Panel Report (EPR-3), highlighted four cornerstones of asthma management: regular assessment of asthma control, patient education, control of environmental factors including avoidance of asthma triggers, and pharmacologic therapy.1 EPR-3 used an evidence-based approach and where evidence was lacking, a consensus approach to make guideline recommendations.

Compared to general practitioners, asthma specialists have higher adherence to asthma guidelines and better patient outcomes.1 It is not clear, however, if better outcomes among specialists are due to higher guideline use compared to generalists; specialty training and experience in managing asthma;2, 3 differences in patient population; or a combination of all these factors. Most comparisons have been between generalists and allergists, or generalists and pulmonologists.4, 5 Few studies have examined how different asthma specialists (allergists and pulmonologists) use the guidelines.6, 7 One study reported high use of spirometry by both specialty groups, greater use of asthma treatment plans by allergists compared to pulmonologists and low use by both specialty groups of standardized asthma control tests.7 Another study described differences in practice characteristics associated with differences in patient populations.8 The goal of this study was to compare guideline agreement and self-efficacy (defined as clinician confidence in their ability to competently implement specific EPR-3 recommendations) between allergists and pulmonologists, using data from a nationally representative sample of asthma specialists. We investigated similarities and differences in guideline use between the two specialty groups to provide information regarding implementation of the guidelines and to inform implementation efforts based upon specialty type, patient population and/or practice characteristics.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) is conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to collect information about patient, clinician, and office visit characteristics. In 2012, a one-time clinician questionnaire supplement (the National Asthma Survey of Physicians, NAS) was added. The NAS questionnaire was designed to assess self-reported clinician agreement, self-efficacy and adherence with EPR-3 recommendations. Data from the 2012 NAS supplement to NAMCS were released in 2017. In addition to the traditional sample of non-federally employed physicians who were engaged primarily in office-based patient care, the 2012 NAMCS oversampled allergists and pulmonologists to provide a sufficient sample size of asthma specialists for the NAS supplement.9, 10 The NCHS Institutional Review Board approved NAS and informed consent was obtained from participating clinicians.

The unweighted and weighted response rates for the overall combined NAS sample were 38% and 28%, respectively, a rate similar to another national physician survey.11 Of the 1726 respondents (i.e., those who responded that they saw patients with asthma), 234 were categorized as asthma specialists. One non-clinical respondent was excluded. The final sample included 134 allergists and 99 pulmonologists. Clinician sociodemographic information included clinical specialty, age, sex, and race and ethnicity. Available data for practice characteristics included census region, level of urbanization, practice ownership, age group(s) of patient population and patient revenue source. Results using the NAS supplement comparing all specialists combined and primary care clinicians have been published previously.12

Outcomes

The four EPR-3-recommended cornerstones of care--assessment and monitoring, patient education, environmental control, and pharmacologic treatment--were used to categorize outcome variables and assess self-reported clinician adherence (Table E1). Specialist agreement and self-efficacy with a smaller subset of EPR-3 recommendations were also determined by self-report (Table E2). Adherence to individual guideline recommendations was initially assessed using a Likert scale of percentage of asthma visits for which the recommendation was followed: “almost always” (≥75% of the time), “often” (25–75% of the time), “sometimes” (1–25% of the time) and “never” (0% of the time). Similarly, agreement was measured with responses ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” and self-efficacy with responses “very confident,” “somewhat confident,” “not at all confident” and “N/A” (do not perform). Missing responses were low (0.01–2.0%) and were excluded for individual outcomes.13

Three index variables were created as dichotomous measures of adherence. An agreement index variable was defined as a response of “strongly agree” versus all other responses to all 5 questions about agreement with selected guideline recommendations (Table E2). Similarly, a self-efficacy index variable was defined as a response of “very confident” versus all other responses for all 5 questions about self-efficacy related to selected guideline recommendations. To assess overall adherence with assessing asthma control, individual outcomes were combined into a third index variable (control index). Asthma control defined by EPR-3 is composed of two domains—impairment and risk. Validated asthma control tests assess impairment but not risk. Accordingly, in the asthma control index, we included questions that assess impairment. Respondents who reported almost always using a control assessment tool and/or almost always asking five questions about impairment (ability to engage in normal activities, daytime symptoms, nighttime symptoms, rescue inhaler/short acting beta agonist (SABA) use, and patient perception of control) were categorized as almost always assessing control. That is, the control index variable indicates if a clinician reported almost always adhering with the overall recommendation to assess asthma control using at least one of two possible methods.

Assessment of adherence to recommendations for pharmacologic treatment of asthma was evaluated by providing respondents with a list of medication classes and requesting respondents to specify the indication for which they used each class of medications (e.g., symptoms relief, controller therapy, add-on therapy, difficult-to-control asthma). Frequencies of use of each medication class for each clinical indication were estimated.

Statistical Analysis

NAS sample weights that accounted for the probability of selection and non-response were used to calculate national estimates, and all analyses accounted for the complex survey design. We compared agreement, self-efficacy, and adherence for each EPR-3 recommendation between allergists and pulmonologists using chi-square test statistics. Statistical reliability of proportions was determined according to NCHS standards,14 and estimates with low reliability are indicated. A two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. P values in the text and tables reflect differences across the range of categories (e.g., age categories or Likert scale).

Separate logistic regression models to assess the association between specialty adherence are shown only for the six guideline recommendations for which adherence differed between allergists and pulmonologists (P<0.10) (documenting asthma control, asking about nighttime awakening, asking about ED visit frequency, performing spirometry, assessing triggers at home, and allergy testing). Multivariable models for each of these outcomes were constructed a priori and included, in addition to specialist category: agreement with guideline recommendations (strong agreement versus other response categories), self-efficacy (very confident versus other response categories), clinician age group (<40, 40–59, 60+ years), clinician sex, clinician race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, all other races), practice region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), urbanization (large metro, medium/small metro, non-metro), practice ownership, and revenue source (e.g., Medicaid, Medicare, private). Covariates were added sequentially in three groups (clinician characteristics, practice location, and practice characteristics) to assess the possible separate sources of confounding. Differences in pharmacologic use between specialty groups were assessed by chi-square analysis. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and SUDAAN 11.0 (RTI, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Results

Clinician and Practice Demographics, Guideline Agreement and Self-efficacy

Compared to pulmonologists, allergists were more likely to be female (29.6% vs 8.7%, P<0.001) and to care for both children and adults (97.3% for allergists vs 12.6% for pulmonologists (P<0.001)) (Table 1). Practice characteristics also varied. Compared to allergists, pulmonologists reported a higher proportion of practice revenue from Medicare (71.5% of pulmonologists reported more than 25% revenue from Medicare versus 22.9% of allergists P<0.001).

Table 1:

Physician and practice characteristics and physician agreement and self-efficacy with EPR-3 guidelines (weighted percentages), by physician specialty, 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians

| Total (n=233) | Allergy (n=134) | Pulmonology (n=99) | Chi square | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | p-value | |

| Provider age | |||||

| <40 years | 24 | 9.5 (2.3) | 8.2* (2.8) | 10.1* (3.1) | 0.28 |

| 40–59 years | 124 | 54.0 (4.1) | 47.4 (5.3) | 57.4 (5.5) | |

| 60+ years | 85 | 36.5 (4.0) | 44.4 (5.4) | 32.5 (5.4) | |

| Provider sex | |||||

| Female | 44 | 15.7 (2.7) | 29.6 (4.6) | 8.7* (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Male | 189 | 84.3 (2.7) | 70.4 (4.6) | 91.3 (3.3) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 175 | 75.3 (3.6) | 75.8 (4.2) | 75.0 (5.1) | 0.56 |

| Other | 50 | 22.8 (3.6) | 20.8 (4.1) | 23.8 (5.1) | |

| Missing | 8 | 2.0 (0.8) | 3.4* (1.7) | 1.3* (0.9) | |

| Ownership of practice | |||||

| Private | 198 | 84.4 (2.8) | 87.8 (3.4) | 82.7 (3.9) | 0.10 |

| HMO, Academic Center, Other | 26 | 12.0 (2.5) | 6.5* (2.4) | 14.8 (3.6) | |

| Missing | 9 | 3.6 *(1.4) | 5.8* (2.6) | 2.5* (1.7) | |

| Census region | |||||

| Northeast | 47 | 21.1 (2.0) | 22.6 (2.7) | 20.3 (3.0) | 0.57 |

| Midwest | 54 | 17.8 (1.5) | 20.5 (2.7) | 16.4 (2.3) | |

| South | 73 | 38.0 (2.7) | 37.4 (3.5) | 38.3 (4.2) | |

| West | 59 | 23.2 (1.8) | 19.5 (2.7) | 25.0 (2.9) | |

| Level of urbanization | |||||

| Large Metro | 154 | 66.5 (3.8) | 63.7 (4.5) | 68.0 (5.5) | 0.80 |

| Medium/Small Metro | 65 | 27.2 (3.7) | 30.3 (4.7) | 25.5 (5.2) | |

| Non-metro | 14 | 6.3 (2.2) | 6.0 (2.6) | 6.5 (3.1) | |

| Patient population | |||||

| Pediatric only | 11 | 8.2* (2.9) | 1.4* (1.4) | 11.6* (4.3) | <0.001 |

| Adult only | 74 | 50.6 (4.2) | 1.3 (0.7) | 75.8 (5.0) | |

| All ages | 141 | 41.3 (3.5) | 97.3 (1.6) | 12.6 (3.1) | |

| Percent Revenue, Medicare | <0.001 | ||||

| <25% | 96 | 29.5 (3.5) | 62.2 (4.9) | 12.7* (4.1) | |

| 25–100% | 102 | 55.1 (4.0) | 22.9 (4.2) | 71.5 (5.4) | |

| Missing | 35 | 15.5 (3.4) | 14.9 (3.6) | 15.8 (4.7) | |

| Agreement with guidelines (index variable) | |||||

| Strongly agree | 64 | 27.9 (3.9) | 23.0 (42) | 30.4 (5.5) | 0.29 |

| Other | 169 | 72.1 (3.9) | 77.0 (4.2) | 69.6 (5.5) | |

| Self-efficacy with guidelines (index variable) | |||||

| Very confident | 175 | 72.3 (3.9) | 76.6 (4.2) | 70.2 (5.4) | 0.33 |

| Other | 58 | 27.7 (3.9) | 23.4 (4.2) | 29.9 (5.4) | |

Estimate does not meet NCHS standards of reliability.

Source: 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

Agreement with five key guideline recommendations from EPR-3 (usefulness of spirometry for asthma diagnosis, inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) effectiveness, asthma action/treatment plan effectiveness, need for ≤6 month follow up visits and assessing severity for initial treatment) ranged from 41.0% for agreement with the effectiveness of asthma action/treatment plans (AAP) to 79.3% for severity assessment to determine initial treatment (Table 2). Strong agreement with all 5 selected guideline recommendations, however, was 27.9%. In contrast, self-efficacy in managing asthma for all five selected guideline recommendations ranged from 81.3% to 92.8% of respondents expressing high confidence in using spirometry, assessing severity, prescribing ICS, and stepping up and stepping down treatment. The overall high self-efficacy index for these 5 recommendations was 72.3%. There were no differences in individual indices for agreement and self-efficacy between allergists and pulmonologists.

Table 2:

Percentage of physicians with strong agreement and high self-efficacy with EPR-3 guideline recommendations, and overall agreement and self-efficacy indicesb (weighted percentages), 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians

| Total | Allergy | Pulmonology | p-valuea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | n | Strongly agree | Other | Strongly agree | Other | Strongly agree | Other | |

| Spirometry is essential for diagnosis | 233 | 77.6 (3.8) | 22.4 (3.8) | 84.2 (3.5) | 15.8 (3.5) | 74.2 (5.3) | 25.8 (5.3) | 0.12 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids are effective for persistent asthma | 232 | 76.0 (3.4) | 24.0 (3.4) | 70.4 (4.9) | 29.6 (4.9) | 78.9 (4.5) | 21.2 (4.6) | 0.21 |

| Asthma action plans are effective | 233 | 41.0 (4.1) | 59.0 (4.1) | 39.2 (4.8) | 60.8 (4.8) | 41.9 (5.8) | 58.1 (5.8) | 0.72 |

| Follow up visits every 6 months | 233 | 68.8 (3.5) | 31.3 (3.5) | 61.1 (5.3) | 38.9 (5.3) | 72.7 (4.5) | 27.3 (4.5) | 0.10 |

| Assessing severity needed for initial treatment | 233 | 79.3 (3.3) | 20.7 (3.3) | 76.6 (4.6) | 23.5 (4.6) | 80.7 (4.4) | 19.3 (4.4) | 0.52 |

| Overall agreement index | 233 | 27.9 (3.9) | 72.1 (3.9) | 23.0 (4.2) | 77.0 (4.2) | 30.4 (5.5) | 69.6 (5.5) | 0.29 |

| Self-efficacy | Very confident | Other | Very confident | Other | Very confident | Other | ||

| Confidence using spirometry | 232 | 92.8 (2.1) | 7.2 (2.1) | 91.7 (2.9) | 8.3 (2.9) | 93.4 (2.8) | 6.6 (2.8) | 0.68 |

| Confidence assessing severity | 233 | 81.3 (3.5) | 18.7 (3.5) | 81.4 (3.8) | 18.6 (3.8) | 81.3 (4.8) | 18.7 (4.8) | 0.92 |

| Confidence prescribing inhaled corticosteroids | 233 | 91.1 (2.2) | 8.9 (2.2) | 93.7 (2.1) | 6.3 (2.1) | 89.7 (3.1) | 10.3 (3.1) | 0.30 |

| Confidence step up treatment | 233 | 89.5 (2.4) | 10.6 (2.4) | 90.8 (3.0) | 9.2 (3.0) | 88.8 (3.2) | 11.2 (3.2) | 0.65 |

| Confidence step down treatment | 232 | 87.0 (2.6) | 13.0 (2.6) | 91.3 (2.8) | 8.7 (2.8) | 84.9 (3.6) | 15.2 (3.6) | 0.15 |

| Overall self-efficacy index | 233 | 72.3 (3.9) | 27.7 (3.9) | 76.6 (4.2) | 23.4 (4.2) | 70.2 (5.4) | 29.9 (5.4) | 0.33 |

Chi-square test significant for difference between allergists and pulmonologists (P<0.05).

Overall strong agreement was defined as strong agreement with all five EPR-3 recommendations shown in the table. Overall high self-efficacy was defined as high confidence in performing all five EPR-3 recommendations shown in the table.

Source: 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

Use of Guideline Recommendations: Similarities and Differences Between Specialties

Assessment of asthma control was high among both allergists and pulmonologists. Allergists were more likely to almost always document asthma control (85.1% versus 72.5%, P=0.04) and to ask about nighttime awakening (91.9% versus 76.5%, P=0.03) than pulmonologists. Regarding assessing risk, allergists more frequently asked about ED visit frequency (92.2% versus 76.5%, P=0.03). Both groups of specialists also almost always assessed frequency of use of rescue inhalers (90.6 %), and oral steroid frequency (86.8%) (Table 3). Both allergists and pulmonologists almost always (93.6% vs 90.7% respectively) assessed daily controller medication use for patients with persistent asthma.

Table 3.

Reported use of guideline recommendations, components 1–3, by specialty (weighted percentages, SE), 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians

| Total | Allergy | Pulmonology | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Almost always | Often | Some-times/Never | Almost always | Often | Some-times/Never | Almost always | Often | Some-times/Never | p-valuea | |

|

Component 1: assess asthma control/severity | |||||||||||

|

Assessment of impairment frequency | |||||||||||

| Document asthma control | 226 | 76.8 (3.8) | 20.5 (3.7) | 2.7* (1.2) | 85.1 (3.1) | 11.0 (2.9) | 3.9* (2.0) | 72.5 (5.5) | 25.5 (5.4) | 2.0* (1.5) | 0.04 |

| Ask about normal activities | 232 | 84.5 (3.3) | 14.9 (3.2) | 0.6 (0.6) | 90.2 (2.7) | 9.8 (2.7) | 0.0* | 81.6 (4.6) | 17.4 (4.5) | 1.0* (1.0) | 0.21 |

| Ask about daytime symptoms | 233 | 91.1 (2.5) | 8.5 (2.5) | 0.4 (0.4) | 93.7 (2.0) | 6.3* (2.0) | 0.0* | 89.7 (3.6) | 9.6* (3.6) | 0.7 (0.7) | 0.44 |

| Ask about nighttime awakening | 233 | 81.7 (3.6) | 14.9 (3.3) | 3.4* (1.9) | 91.9 (2.2) | 8.1 (2.2) | 0.0* | 76.5 (5.2) | 18.4 (4.7) | 5.2* (2.8) | 0.03 |

| Use control assessment tool | 233 | 28.6 (3.5) | 20.4 (3.4) | 51.0 (4.2) | 37.0 (4.9) | 21.8 (4.3) | 41.2 (5.4) | 24.3 (4.8) | 19.7 (4.7) | 56.0 (5.7) | 0.13 |

| Ask about perception of control | 233 | 70.7 (4.2) | 26.0 (4.0) | 3.3* (1.9) | 78.3 (4.2) | 21.5 (4.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | 66.8 (5.8) | 28.4 (5.6) | 4.8* (2.9) | 0.13 |

| Ask about frequency rescue inhaler use | 233 | 90.6 (2.8) | 6.5* (2.2) | 2.9* (1.7) | 94.7 (2.3) | 2.7* (1.2) | 2.7* (2.0) | 88.6 (4.0) | 8.5* (3.3) | 3.0* (2.4) | 0.29 |

|

Assessment of risk frequency | |||||||||||

| Ask about oral steroid frequency | 232 | 86.8 (3.1) | 11.6 (3.1) | 1.6 (0.8) | 87.5 (3.7) | 9.2* (3.2) | 3.3* (2.1) | 86.5 (4.3) | 12.8* (4.3) | 0.7 (0.7) | 0.43 |

| Ask about ED visit frequency | 232 | 81.9 (3.8) | 12.6 (3.2) | 5.6* (2.2) | 92.2 (2.5) | 4.6* (1.5) | 3.2* (2.0) | 76.5 (5.5) | 16.6 (4.7) | 6.8* (3.2) | 0.03 |

|

Objective assessment and monitoring | |||||||||||

| Ask about peak flow results | 231 | 12.8 (2.5) | 27.9 (3.7) | 59.3 (4.1) | 16.1 (3.8) | 20.7 (4.2) | 63.2 (4.6) | 11.1 (3.3) | 31.6 (5.3) | 57.3 (5.7) | 0.21 |

| Perform spirometry | 232 | 44.7 (4.1) | 35.0 (4.0) | 20.3 (4.0) | 56.6 (5.2) | 31.0 (4.8) | 12.4 (3.4) | 38.6 (5.5) | 37.1 (5.7) | 24.3 (5.7) | 0.06 |

|

Ongoing monitoring frequency | |||||||||||

| Assess daily controller use | 232 | 91.7 (2.4) | 8.2 (2.4) | 0.2 (0.1) | 93.6 (2.6) | 6.0* (2.6) | 0.4 (0.4) | 90.7 (3.4) | 9.3* (3.4) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.48 |

| Repeated assessment inhaler technique | 233 | 39.7 (4.0) | 44.9 (4.3) | 15.5 (3.0) | 44.5 (5.0) | 38.4 (5.1) | 17.1 (4.0) | 37.2 (5.6) | 48.2 (6.0) | 14.6* (4.1) | 0.45 |

|

Component 2: patient education | |||||||||||

| Provide asthma action plan | 233 | 30.6 (3.6) | 32.7 (4.1) | 36.7 (4.4) | 37.5 (4.9) | 32.8 (4.9) | 29.7 (4.6) | 27.1 (4.8) | 32.7 (5.7) | 40.3 (6.0) | 0.25 |

|

Component 3: control of environmental factors | |||||||||||

| Assess home triggers | 233 | 58.7 (4.2) | 35.2 (4.2) | 6.1* (2.2) | 70.6 (4.7) | 26.8 (4.5) | 2.6* (1.9) | 52.6 (5.8) | 39.5 (5.8) | 8.0* (3.2) | 0.06 |

| Assess school or workplace triggers | 230 | 71.3 (3.9) | 24.2 (3.6) | 4.2* (2.0) | 70.0 (4.4) | 25.4 (4.2) | 4.6* (2.1) | 72.0 (5.5) | 23.6 (5.1) | 4.4* (2.8) | 0.96 |

| Test for allergic sensitivity | 233 | 35.0 (3.6) | 32.3 (4.1) | 32.8 (4.0) | 61.8 (4.8) | 26.9 (4.6) | 11.3 (2.7) | 21.3 (4.6) | 35.0 (5.7) | 43.7 (5.8) | <0.001 |

Chi-square test for difference between allergists and pulmonologists

Estimate does not meet NCHS standards of reliability. Source: 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Notes: ED=emergency department

For some components of the asthma guidelines, fewer than half of clinicians from each specialty group reported high adherence (Table 3). These included almost always using an asthma control assessment tool (28.6%), asking about peak flow results (12.8%), and regular assessment of inhaler technique (39.7%). Spirometry was almost always performed by less than half of the specialists (44.7%). Reported adherence to providing a written AAP was low among both specialty groups (30.6% for “almost always”) with no difference in adherence between specialty groups (P=0.25) (Table 3). Moderate proportions of specialists almost always assessed individual home and/or school/workplace environmental triggers (range 58.7–71.3% overall), while a higher percentage of allergists than pulmonologists almost always performed allergy testing (61.8% vs 21.3%, P<0.001).

Asthma control can be assessed in at least two ways that are consistent with the guidelines (asthma control tool or asking a set of questions). To more broadly compare asthma specialist groups assessing asthma control, specialties were compared on “almost always” using one or both possible means to assess asthma control using an index variable (Table 4). Overall, 66.2% of specialists reported almost always assessing control using one or both methods. The percentage with high adherence to assessing asthma control did not vary between specialties (P=0.26), but the method used did (P=0.02). Allergists were nearly evenly split between using questions combined with an asthma control tool, or questions only (49.6% and 48.4%) with only 2% almost always using only an asthma control tool. Nearly two thirds (61.6%) of pulmonologists used questions only, 27.0% used both questions and an asthma control tool, and 11.4% used only an asthma control tool.

Table 4.

Percentage of specialists with high adherence to asthma control assessment, by specialty (weighted percentages, SE), 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians

| Means to assess control | Total (n=224) | Allergy | Pulmonology | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control indexb | 66.2 (4.3) | 71.7 (4.7) | 63.3 (5.9) | 0.26 |

| Means used to assess asthma control (among those with high adherence) | 0.02 | |||

| Questions & tool | 35.3 (4.3) | 49.6 (6.0) | 27.0 (5.8) | |

| Questions only | 56.8 (4.8) | 48.4 (6.0) | 61.6 (6.8) | |

| Tools only | 7.9 (3.1) | 2.0 (1.3) | 11.4 (4.9) | |

Chi-square test for difference between allergists and pulmonologists across all categories.

Control index defined as almost always assessing asthma control using either or both the following:

● Questions: ability to engage in normal activities, daytime and nighttime symptoms, SABA use, patient perception of control

● Tool: Use of an Asthma control assessment tool

Source: 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

Assessing Differences in Adherences between Specialties

Table 5 shows crude and adjusted odds for the six adherence outcomes that differed between allergists and pulmonologists. In unadjusted analyses, allergists had higher odds of almost always adhering to the following recommendations: document asthma control, ask about nighttime awakening, ask about ED/urgent care visits, perform spirometry, assess triggers at home, and perform allergy testing (crude odds ratios ranged from 2.0 to 6.5). In adjusted analyses, a significant difference between allergists and pulmonologists remained only for allergy testing. High self-efficacy was significantly associated only with performing spirometry (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 5.0, 95% CI 2.1, 11.9). While practice location in the Northeast and practice ownership were associated with allergy testing, controlling for these and other factors did not negate the observed association between specialty and allergy testing. Physicians practicing outside of large metropolitan areas were more likely to report almost always documenting asthma control and asking about nighttime awakening.

Table 5:

Crude and adjusted odds ratios for physician specialty, adjusted odds ratios of covariates for six guideline recommendations that differ between allergists and pulmonologists, 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians

| Document control | Ask about night awakening | Ask about ED/urgent visits | Perform spirometry | Assess triggers at home | Perform allergy testing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Crude odds ratios (95% confidence interval) | ||||||

| Specialty (referent: Pulmonology) | ||||||

| Allergy | 2.1 (1.0, 4.6) | 3.7 (1.6, 8.5) | 3.5 (1.4, 8.7) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.8) | 2.3 (1.2, 4.4) | 6.5 (3.3, 13.0) |

|

Adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence interval) | ||||||

| Specialty (referent: Pulmonology) | ||||||

| Allergy | 1.0 (0.4, 2.9) | 2.6 (0.8, 8.2) | 3.1 (0.7, 13.8) | 1.5 (0.5, 4.0) | 1.5 (0.7, 3.6) | 5.8 (2.2, 15.4) |

| Index of agreement (referent: less than strong) | ||||||

| Strongly agree | 0.5 (0.2, 1.5) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.1) | 0.7 (0.2, 2.5) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.3) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.6) | 1.2 (0.5, 3.3) |

| Index of self-efficacy (referent: less than high) | ||||||

| Very confident | 1.5 (0.5, 4.4) | 2.6 (0.7, 9.1) | 2.8 (0.9, 8.9) | 5.0 (2.1, 11.9) | 2.0 (0.8, 4.7) | 1.8 (0.7, 4.4) |

| Age group (referent: < 40 years) | ||||||

| 40–59 years | 1.6 (0.4, 5.8) | 0.5 (0.1, 3.9) | 2.4 (0.5, 11.4) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.9) | 0.7 (0.2, 2.3) | 0.9 (0.3, 3.0) |

| 60+ years | 2.8 (0.7, 11.5) | 0.2 (0.0, 1.7) | 0.6 (0.1, 2.5) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.3) | 0.8 (0.2, 2.8) | 1.0 (0.3, 3.6) |

| Physician sex (referent: male) | ||||||

| Female | 2.3 (0.7, 8.0) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.8) | 0.7 (0.1, 3.9) | 1.1 (0.4, 2.7) | 1.9 (0.7, 5.7) | 1.9 (0.7, 5.3) |

| Physician race/ethnicity (referent: non-Hispanic white) | ||||||

| All other | 0.4 (0.1, 1.0) | 1.4 (0.5, 4.1) | 1.5 (0.5, 4.5) | 0.4 (0.2, 1.0) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.4) | 1.7 (0.6, 4.6) |

| Region (Referent: West) | ||||||

| Northeast | 0.2 (0.0, 0.6) | 1.5 (0.2, 9.3) | 2.5 (0.5, 12.9) | 1.3 (0.5, 3.3) | 1.3 (0.4, 3.9) | 4.9 (1.5, 16.3) |

| Midwest | 0.5 (0.1, 2.2) | 2.0 (0.3, 11.6) | 2.1 (0.4, 11.6) | 2.4 (0.8, 6.7) | 1.7 (0.6, 5.0) | 3.2 (0.9, 11.3) |

| South | 0.3 (0.1, 1.5) | 0.2 (0.0, 1.1) | 0.2 (0.1, 1.2) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.7) | 0.7 (0.3, 2.1) | 1.5 (0.5, 4.9) |

| Urbanization (referent: large metro) | ||||||

| All other | 3.0 (1.1, 8.1) | 6.1 (1.6, 24.0) | 2.1 (0.6, 7.5) | 0.9 (0.4, 2.0) | 1.9 (0.8, 4.3) | 2.0 (0.7, 5.3) |

| Practice ownership (referent: private) | ||||||

| HMO, academic center and/or other hospital | 0.6 (0.2, 2.1) | 0.3 (0.1, 1.6) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.5) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.1) | 0.3 (0.1, 1.0) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.8) |

| Medicare revenue (referent >25%) | ||||||

| <25% | 2.4 (0.7, 8.1) | 6.8 (1.3, 34.7) | 2.3 (0.4, 15.0) | 1.5 (0.6, 4.0) | 1.1 (0.4, 2.8) | 0.9 (0.4, 2.6) |

| Missing | 2.0 (0.5, 7.4) | 0.5 (0.1, 1.8) | 2.7 (0.8, 9.2) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.8) | 0.7 (0.2, 2.4) | 0.6 (0.2, 2.0) |

Notes: Bolded odds ratios have 95% confidence intervals that exclude 1.0 (note some values above or below 1.0 may be rounded to 1.0).

Two covariates appeared to confound of the association between specialty and adherence outcomes: practice ownership and payment source (see Table E3 for impact of sequential addition of covariates to the models). Physicians practicing in an HMO or academic center compared to private practice had lower odds of asking about ED visits, assessing triggers at home, and performing allergy testing compared to the referent category of private practice. Physicians in practices with <25% of revenue from Medicare were more likely to ask about nighttime awakening (AOR 6.8, 95% CI 1.3, 34.7). These practice-related factors, even when not statistically significantly related to high adherence, appeared to confound the association between specialty and adherence more than other factors (agreement and self-efficacy, physician characteristics and practice location).

Pharmacologic Treatment: Similarities and Differences

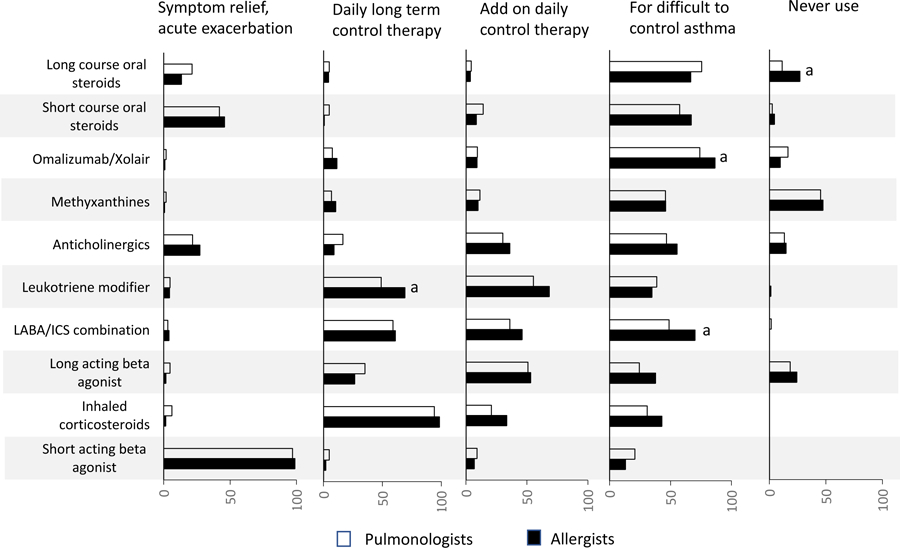

Pharmacologic management differed between allergists and pulmonologists in several ways. Both specialty groups highly endorsed use of SABA for symptomatic relief and use of ICS for long term asthma control (overall, 97.5% and 95.5%, respectively) (Figure 1). Allergists reported that they were more likely to use a long-acting bronchodilator (LABA)/ICS combination for difficult to control asthma compared to pulmonologists (70.0% vs 48.7%, respectively, P=0.008) and more likely to use a leukotriene modifier (LTRA) for long-term asthma control (69.0% vs 48.9%, P=0.006). Allergists were also more likely to use Omalizumab for difficult to control asthma (86.4% vs 74.0%, P=0.04). Twenty-seven percent of allergists never used long courses of oral steroids compared to 11.2% of pulmonologists (P=0.004).

Figure 1:

Reported use of pharmacologic therapy for asthma, by indication of the guideline recommendation component, by specialty, 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians

a Chi-square test significant for difference between allergists and pulmonologists (P<0.05). Note: Estimates that did not meet the NCHS standards of reliability are not separately indicated in the figure. These estimates were all below 10%, indicating an appropriately low percentage of clinicians reporting a non-indicated usage. All estimates for which a significant difference was observed between specialties were reliable.

Source: 2012 National Asthma Survey of Physicians: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

Discussion

This study demonstrates that specialists agree with most EPR-3 guidelines (except for the effectiveness of asthma action/treatment plans) and adhere to most guideline recommendations, and that similarities and differences exist between allergists and pulmonologists. Similarities include high adherence with assessment of asthma control (albeit by different methods), use of short acting bronchodilators for quick relief, and use of ICS for long-term asthma control. In both specialty groups, however, adherence to other guideline recommendations (e.g., AAP use, frequent use of spirometry, asking about peak flow results, and repeated assessment of inhaler technique) was below 50%. While most specialists endorsed the assessment of asthma control, use of allergy testing differed by specialty, with allergists being nearly three-times more likely to perform testing for allergic sensitization than pulmonologists. Patterns of medication use also differed by specialty with allergists using more ICS/LABA combinations and more omalizumab for difficult to control asthma and more LTRA for long term asthma control than pulmonologists, and pulmonologists using more oral corticosteroids than allergists.

Use of the guidelines by both specialty groups for all recommendations, however, was higher than published studies of guideline use by generalists.12 Our findings are consistent with the few studies that have compared guideline adherence between allergists and pulmonologists. In the multicenter TENOR study of patients with either severe or difficult to treat asthma who were cared for by pulmonologists or allergists, allergists reported using more leukotriene modifiers while pulmonologists prescribed more oral corticosteroids for long-term therapy.8 In other studies, pulmonologists were more likely to use high-dose ICS than allergists.5, 6

Guidelines are designed to standardize patient care using an evidence-based approach. Our findings and others, however, suggest significant differences in practice characteristics between pulmonologists and allergists.5, 6, 8 Many of the differences in guideline use observed in this study are consistent with differences in asthma populations seen by the two specialties. Patients with suspected underlying allergic disease are more likely to be referred to an allergist for an allergy evaluation while patients with fixed airway disease or worse lung function are often referred to pulmonologists.9 Patient demographics are also likely to be different. In TENOR, it was suggested that the higher proportion of patients without private insurance who were receiving care from pulmonologists could be explained by the affiliation of more pulmonary practices with large, urban medical centers.8 This does not appear to be the case in our study, in that there were no differences in practice locations in urban centers or in practice ownership. Pulmonologists, however, reported receiving a higher proportion of practice revenue from Medicare compared to allergists, and some pulmonary practices may experience limitations in medication choices, older patient age groups, and a higher prevalence of co-morbidities (including COPD and severe asthma). This COPD/asthma overlap and the severity of disease may be reflected in the greater use of long-term oral corticosteroids by pulmonologists. Older age, patient co-morbidities, and lower socioeconomic status associated with limited reimbursement and cultural disparity in terms of affordability and acceptability are factors in what has been called “clinical inertia”, defined as “failure to treat to target, or prescription that is not concordant with guidelines.”15

Less than half of specialists reported almost always performing spirometry testing. This is much lower than the ~95% reported in the Asthma Insight and Management Survey.7 In that study, the type of lung function test (spirometry, peak flow) was not specified in the physician questionnaire and could have been performed either in the physician’s own clinic or via referral. However, 72% of physicians in that study reported conducting an annual lung function test for each patient. This measure still differs from the assessment in the current study which asked about the percentage of visits for which spirometry was performed, and questionnaire differences could explain the different results between studies. While not statistically different, a higher percentage of allergists reported almost always performing spirometry than pulmonologists. Differences in frequency of use of spirometry have been observed by others with allergists performing more spirometry than pulmonologists.16 The guidelines recommend spirometry testing at the initial assessment, after treatment is initiated and symptoms have stabilized, during periods of progressive or prolonged loss of asthma control, every 1–2 years or more frequently as well as to assess “step down” therapy.1 It is possible that specialists interpreted this question differently; pulmonologists see a greater number of older patients with Medicare who in general have greater disease severity and more appointments than younger patients and may have more difficulty performing spirometry testing.8 Thus, the frequency of testing could be less for the Medicare population and patient populations seen by pulmonologists. Guideline ambiguity is likely an additional factor in differences in practice patterns. A more nuanced question (or set of questions) may have been able to better explore the reasons for the differences in spirometry testing than the those included in the survey.

The guidelines recommend a written AAP for all asthma patients. Similar to two other studies of specialists in which 51% and 33% reported preparing a written AAP for all or most of their patients,18,19 we found that only 30.6% of specialists almost always either provided patients with a new written plan or reviewed an existing plan. Recent reports suggest that specialists question the value of written treatment plans despite the strength of evidence demonstrating their benefit to individuals with asthma (Grade B in the guidelines).17

The frequency of almost always teaching/reviewing inhaler technique was lower than expected. Improper inhaler technique is known to contribute to unintentional medication non-adherence and the results from this study suggest adherence to the guidelines could be improved. It is a rarely assessed element of asthma care for both generalists and specialists18 and proper inhaler technique is associated with improved control.19

This study has limitations. Although new literature/evidence has accumulated since 2007, the results reflect clinical practice after the latest guideline update. Revised guidelines in 2020 are designed to update EPR-3 in targeted areas, but the basic components of the EPR-3 guidelines evaluated in this study will remain current. Thus, these findings are relevant to continued efforts to understand and increase guideline adherence. Self-reported behaviors are subject to social and recall bias,.20 Furthermore, past studies have shown that physician-reported behavior and clinical decision making differs from that documented in the medical record and/or actual behavior and practice.21, 22 Relatively low response rates in physician surveys are also known limitations.23 The NAS did not report response rates for specialists separately from the entire group. Sample weights accounted for the probability of selection and non-response and were used to calculate national estimates. Finally, while the NAS was not specifically designed to be representative of specialists, the characteristics of NAS asthma specialists were comparable to allergists in a 2014 workforce survey,24 suggesting a representative sample. The questions were developed for all practicing clinicians and may not have been sufficiently nuanced for the types of patients cared for by specialists, who may have co-morbidities that alter assessment and treatment in different ways.

The major strengths of this study are the nationally representative sample of both allergists and pulmonologists and the broad range of questions that included multiple key recommendations within the current guidelines. In addition, both adult and pediatric specialists were included.

Previous studies have shown that patients cared for by specialists experience improved outcomes.2, 3, 5, 25 Whether these improved outcomes are due to guideline adherence or to specialists’ additional training and experience is not clear.26 Schatz et al. found no difference in outcomes between patients of allergists and those of pulmonologists, suggesting that it is training and experience that are most important.5 Patient outcomes were also not assessed in the NAS data. There may be factors that influence specific elements of care by pulmonologists and allergists and understanding the factors and clinical decision-making underlying variations in guideline adherence and differences between specialist groups could better inform guideline recommendations with respect to specialist practice characteristics and patient populations. Inherent in the EPR-3 guidelines is the assumption that both specialists and generalists should adhere to evidence-supported recommendations to improve patient outcomes. This study informs efforts to further improve asthma outcomes by improving specialist practice, especially in the area of assessment of inhaler technique.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this topic?

Asthma specialists have higher adherence to asthma guidelines than general practitioners. Yet, little is known whether guideline agreement and adoption vary between allergists and pulmonologists at the national level.

What does this article add to our knowledge?

Guideline agreement and self-efficacy did not differ between specialist groups, and both had relatively low percentages who almost always provided asthma action plans or regularly assessed inhaler technique. Adherence differences were explained by practice-specific differences.

How does this study impact current management guidelines?

Improving understanding of factors and clinical decision-making underlying lower adherence to guideline recommendations and different adherence patterns between allergists and pulmonologists could better inform guideline recommendations with respect to specialist practice characteristics and patient populations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Z01-ES-025041), and through a contract to Social & Scientific Systems funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (HHSN273201600002I).

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Abbreviations:

- AAP

Asthma Action/Treatment Plan

- ED

emergency department

- EPR-3

Expert Panel Report-3

- ICS

Inhaled Corticosteroid

- LABA

Long-acting beta agonist

- NAEPP

National Asthma Education and Prevention Program

- NAMCS

National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

- NAS

National Asthma Survey

- NCHS

National Center for Health Statistics

- SABA

Short-acting beta agonist

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: Dr. Schatz receives research funding paid to his institution from Merck and ALK. This work is not related to the current manuscript. Dr Fuhlbrigge is an unpaid consultant to AstraZeneca for the development of asthma and COPD related outcome measures and a consultant to Novartis for analyses related to asthma control. Neither of these projects is directly related to the current manuscript. No other authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Harrold LR, Field TS, Gurwitz JH. Knowledge, patterns of care and outcomes of care for generalists and specialists. J Gen Intern Med 1999;14(8):499–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly CS, Morrow AL, Shults J, Nakas N, Strope G, Adelman RD. Outcomes evaluation of a comprehensive intervention program for asthmatic children enrolled in Medicaid. Pediatrics. 2000. 105:1029–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott L, Morphew T, Bollinger ME, Samuelson S, Galant SP, Clement LT, et al. Achieving and maintaining asthma control in inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:432–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braido F, Baiardini I, Alleri P, Bacci E, Barbetta C, Bellochia M, et al. Asthma management in a specialist setting: Results of an Italian Respirtory Society survey. Pulmonary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2017;44:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schatz M, Zeiger RS, Mosen D, Apter AJ, Vollmer WM, Stibolt TB, et al. Improved asthma outcomes from allergy specialist care: A population-based cross-sectional analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;116:1307–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanc PD, Katz PO, Henke J, Smith S, Yelin EH. Pulmonary and allergy subspecialty care in adults with asthma: Treatment, use of services and health outcomes. West J Med 1997;167:398–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy KR, Meltzer EO, Blaiss MS, Nathan RA, Stoloff SW, Doherty DE. Asthma management and control in the United States: Results of the 2009 Asthma Insight and Management Survey. Allergy Asthma Proc 2012;33:54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H, Johnson CA, Haselkorn T, Lee JH, Israel E. Subspecialty differences in asthma characteristics and management. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:786–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistics NCfHSDoHC. 2012 NAMCS micro-data file documentation. 2016. ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NAMCS/doc2012.pdf. Published 2012 August 21, 2015.

- 10.Statistics NCfHSDoHC. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey 2012 Asthma Supplement. 2012.

- 11.The College of Family Physicians of Canada CMA RC. National Physician Survey 2014 Response Rates. Mississauga, Ontario: National Physician Survey; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cloutier MM, Salo PM, Akinbami LJ, Cohn RD, Wilkerson JC, Diette GB, et al. Clinician agreement, self-efficacy, and adherence with the guidelines for the diagnosis and managment of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol: In Pract 2018;6:886–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knol MJ, Janssen KJ, Donders AR, Egberts AC, Heerdink ER, Grobbee DE, et al. Unpredictable bias when using the missing indicator method or complete case analysis for missing confounder values: an empirical example. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63(7):728–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker JDTM, Malec DJ, Beresovsky V, Carroll M, Gonzalez JF, et al. Presentation Standards for Proportions. National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aijoulat I, Jacquemin P, Rietzschel E, Scheen A, Trefois P, Wens J, et al. Factors associated with clinical inertia: an integrative review. Advances in Medical Education and Practice. 2014;5:141–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sokol KC, Sharma G, Lin Y-L, Goldblum RM. Choosing wisely: Adherence by physicians to recommended use of spirometry in the diagnosis and management of adult asthma. American Journal of Medicine. 2015;128:502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheares BJ, Du Y, Vazquez TL, Mellins RB, Evans D. Use of written treatment plans for asthma by specialist physicians. Pediatr Pulmonol 2007;42(4):348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janson S, Weiss K. A national survey of asthma knowledge and practices among specialists and primary care physicians. The Journal of asthma : official journal of the Association for the Care of Asthma. 2004;41(3):343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baddar S, Jayakrishnam B, Al-Rawas OA. Asthma control: Importance of compliance and inhaler technique assessments. J Asthma 2014;51(4):429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy KR, Meltzer EO, Blaiss MS, Nathan RA, Stoloff SW, Doherty DE. Asthma management and control in the United States: results of the 2009 Asthma Insight and Management survey. Allergy and asthma proceedings : the official journal of regional and state allergy societies. 2012;33(1):54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erhardt LR. Barriers to effective implementation of guideline recommendations. Am J Med 2005;118 Suppl 12A:36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, Gillespie K, Narayan KMV, Lang K. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 2001;20(1):61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Association of American Medical Colleges. 2014 Physician Specialty Data Book: Center for Workforce Studies. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2014 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aung YN, Majaesic C, Senthilselvan A, Mandhane PJ. Physician specialty influences important aspects of pediatric asthma management. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2014;2(3):306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinberger M Why clinical practice guidelines hinder rather than help. Paediatr Respir Rev 2018;25:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.