Abstract

Food digestion is vital for the survival and prosperity of insects. Research on insect digestive enzymes yields knowledge of their structure and function, and potential targets of antifeedants to control agricultural pests. While such enzymes from pest species are more relevant for inhibitor screening, a systematic analysis of their counterparts in a model insect has broader impacts. In this context, we identified a set of 122 digestive enzyme genes from the genome of Manduca sexta, a lepidopteran model related to some major agricultural pests. These genes encode hydrolases of proteins (85), lipids (20), carbohydrates (16), and nucleic acids (1). Gut serine proteases (62) and their noncatalytic homologs (11) in the S1A subfamily are encoded by abundant transcripts whose levels correlate well with larval feeding stages. Aminopeptidases (10), carboxypeptidases (10), and other proteases (3) also participate in dietary protein digestion. A large group of 11 lipases as well as 9 esterases are probably responsible for digesting lipids in diets. The repertoire of carbohydrate hydrolases (16) is relatively small, including two amylases, three maltases, two sucreases, two α-glucosidases, and others. Lysozymes, peptidoglycan amidases, and β−1,3-glucanase may hydrolyze peptidoglycans and glucans to harvest energy and defend the host from microbes on plant leaves. One alkaline nuclease is associated with larval feeding, which is likely responsible for hydrolyzing denatured DNA and RNA undergoing autolysis at a high pH of midgut. Proteomic analysis of the ectoperitrophic fluid from feeding larvae validated at least 131 or 89% of the digestive enzymes and their homologs. In summary, this study provides for the first time a holistic view of the digestion-related proteins in a lepidopteran model insect and clues for comparative research in lepidopteran pests and beyond.

Keywords: phylogenetic analysis, insect immunity, midgut, serine protease, lipase, esterase, carbohydratase, RNA-Seq

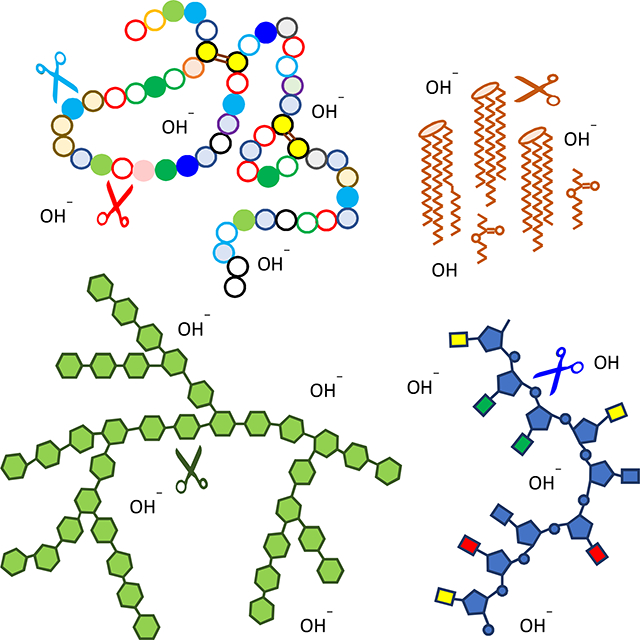

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The evolutionary success of diverse insects depends on their abilities to acquire nutrients from various food sources, detoxify xenobiotics, and kill pathogens. Understanding the biochemistry and molecular biology of insect digestion, detoxification, and defense is, therefore, crucial for the development of novel strategies that control agricultural pests and disease vectors (Terra and Ferreira, 2012; Zhu-Salzman and Zeng, 2015; Saraiva et al., 2016). Genome and gut transcriptome data are available from pests including Plutella xylostella (You et al., 2013; Lin et al. 2018), Spodoptera frugiperda (Brioschi et al., 2007; Kakumani et al., 2014), Helicoverpa armigera (Kuwar et al., 2015; Pearce et al., 2017), Tenebrio molitor (Oppert et al., 2018), Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Schoville et al., 2018), Mayetiola destructor (Zhang et al., 2010) and Locusta migratoria (Spit et al., 2016), and from vectors such as Anopheles gambiae (Dennison et al., 2016) and Aedes aegypti (Canton et al., 2015). Similar data are also available from model insects like Drosophila melanogaster (Dutta et al., 2015), Tribolium castaneum (Morris et al., 2009) and Manduca sexta (Pauchet et al., 2010). In comparison with medically important insects, agricultural pests feed on crops and, hence, food digestion is better studied in many of these species. Digestive proteases and pest responses to protease inhibitors or proteolytically activated bacterial toxins have received special attentions due to close associations with practical problems and biotechnological applications (Khajuria et al., 2010; Srp et al., 2016; Oppert et al., 2012).

The tobacco hornworm M. sexta represents a large group of agricultural pests in the order of Lepidoptera and should contribute to the research on insect digestive enzymes on the basis of its well-studied genome and transcriptomes (Kanost et al., 2016; Cao and Jiang, 2017). Thirteen of the 67 RNA-seq datasets are from midgut tissues of M. sexta ranging from 2nd instar larvae to late adults. While nondigestive serine proteases (SPs, 107) and their homologs (SPHs, 18) in the S1A subfamily were well annotated (Cao et al., 2015), gut (serine) proteases (GPs) and their noncatalytic homologs (GPHs) in the same group have not yet been reported so far in the genome level. Prior to the genome analysis, a study of the midgut transcriptome (Pauchet et al., 2010) provided three key functional perspectives of this tissue during larval feeding stages, digestion, detoxification and defense. That research reported cDNA sequences but not mRNA levels. Lacking gene transcription details, it is unclear which gene products are responsible for digesting major food ingredients or how their roles may vary in distinct life stages. In comparison to SP-like proteins in the S1A subfamily, less is known about other digestive enzymes that hydrolyze proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids. Although overview of these enzymes is available for a few agricultural pests (Pearce et al., 2017; Spit et al., 2016; Oppert et al., 2018), in-depth analysis of a complete set of digestion-related proteins is not yet available for any insect to the best of our knowledge. In fact, there is no exquisite separation between digestive enzymes and midgut-specific proteins, between enzymes and their noncatalytic homologs, between extracellular and intracellular proteins, and between feeding and nonfeeding stages. To address these problems, we examined GP(H) sequences and identified other groups of digestive enzymes. We then explored their gene expression patterns, proposed tentative names and functions for these proteins, and identified proteins in ectoperitrophic fluid from feeding larvae to validate our predictions. The systematic analysis in a biochemical model should facilitate research on similar proteins in agricultural pests and development of inhibitors that cause indigestion.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Identification of M. sexta digestive enzymes and new S1A SP(H)s

Genes of putative digestive enzymes were first selected from expression group-9, −10 and −11, representing genes preferentially expressed in midgut tissues (Cao and Jiang, 2017). OGS2.0 genes with FPKM values lower than 100 in all the 67 libraries were excluded from that study. A BLASTP search was performed against NR database of NCBI in a local supercomputer with “hit-table” used as the output format. Subject sequences with at least one hit (identity >25%, length >50, E-value <10−6, and bit score >100) were considered as homologs of the queries. Using Python scripts, query genes were first named after the best matched homologs based on hit-linked information. Highly expressed genes were manually examined to ensure accuracy. Queries without names or with but unrelated to digestion were eliminated prior to further analysis. Gut (serine) proteases (GPs) and their noncatalytic homologs (GPHs) in the S1A subfamily were set aside from other digestion-related proteins for more extensive examination along with the S1A SP(H)s. Domain structures of protein sequences in MCOT 1.0 (Cao and Jiang, 2015) and Manduca OGS2.0 (Kanost et al., 2016) were predicted using InterProScan 5 (v5.17). Proteins containing a chymotrypsin-like domain were extracted for comparison with the 193 SP(H)s (Cao et al., 2015) to find new ones. Their gene models were manually improved by crosschecking Oases 3.0, Trinity 3.0, Cufflinks 1.0, and Manduca genome contigs (Cao and Jiang, 2015; Kanost et al., 2016).

2.2. Expression profiling

Fifty-two cDNA libraries were sequenced by Illumina technology, each representing a sample of whole larvae, organs, or tissues at various life stages (Kanost et al., 2016). The number of reads mapped onto each transcript in the list of digestive enzymes and their noncatalytic homologs was used to calculate transcripts per kilobase million (TPM) in the libraries by RSEM (Li and Dewey, 2011). Hierarchical clustering of the log2(TPM +1) values was performed using Seaborn, a Python package with the Euclidean-based metric and average linkage clustering method.

2.3. Sequence properties of M. sexta digestion-related proteins

For S1A SPs and SPHs, sequences were categorized by examining the presence of a His-Asp-Ser catalytic triad. If all three residues existed in the conserved TAAHC, DIAL and GDSGGP motifs, the proteins were considered as SPs or GPs. Sequences lacking one or more of the residues were designated SPHs or GPHs. GP(H)s were first identified in midgut (Pauchet et al., 2010) but GP6, GP33, GPH35 and GPH46 were expressed at similar levels in other tissues (Cao et al., 2015). For other digestion-related proteins, structural features were revealed by multiple sequence alignment of homologous enzymes whose catalytic mechanisms are known. Protease families are named based on a BLAST search of MEROP peptidase database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/merops/). Signal peptide was predicted by SignalP 4.1 (Petersen et al., 2011). Domain structure and catalytic residues of each enzyme were predicted using InterProScan (Jones et al., 2014). Residues 190, 216 and 226 (chymotrypsin numbering) (Perona and Craik, 1995), which determine the primary substrate-binding pocket, were identified from the aligned protease domain sequences to predict substrate specificities of the GPs. Residue annotation of Zn proteases, amino- or carboxy-peptidases, lipases, esterases, and other hydrolases were performed using InterProScan (v5.35).

2.4. Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

A multiple sequence alignment of the 80 entire S1A SP(H)s specifically expressed in midgut were performed using MUSCLE, one module of MEGA 7.0 (http://www.megasoftware.net) under the default settings with maximum iterations changed to 1000. The aligned sequences were converted to NEXUS format by MEGA (Kumar et al., 2016). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using MrBayes v3.2.6 (Ronquist et al., 2012) under the default model with the setting “nchains=6”. MCMC (Markov chain Monte Carlo) analyses were terminated after the standard deviations of two independent analyses was <0.01 or after 10 million generations (SD < 0.01). FigTree 1.4.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) was used to display the phylogenetic tree.

2.5. Insect rearing and collection of ectoperitrophic fluid

M. sexta eggs were ordered from Carolina Biological Supply and larvae were reared on an artificial diet (Dunn and Drake, 1983). Whole guts, dissected from 3–5 day 1 or 2, 5th instar larvae, were rinsed three times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.4 mM KH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4) and once with sterile 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0 to remove hemolymph. After blotting with a dry filter paper, a scission was made through the midgut epithelial layer to expose peritrophic membrane. Upon removal of the membrane and its content, central 3/5 of the whole midgut was excised and transferred to a microfuge tube containing 100 μl of sterile 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0 and, after gentle mixing, centrifuged at 15,000×g for 2–3 min. About 150 μl of the supernatant was collected as a sample of ectoperitrophic fluid or digestive juice and aliquoted for protein concentration measurement, for storage at −80 °C, and for treatment with 1/5 volume of 6×SDS sample buffer at 95 °C for 5 min.

2.6. SDS-PAGE separation, peptide sample preparation, and LC-MS/MS analysis

Proteins in the digestive fluid (6 μg) were separated by electrophoresis on a 4–15% Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast protein gel (Bio-Rad). After Coomassie staining, the protein lane was cut into four gel slices and processed as described before (He et al., 2016). Extracted trypsinolytic peptides were dissolved in 45 μl of mobile phase A (0.1% HCOOH in H2O), and 10 μl were injected onto a heated 75 μm×50 cm Acclaim PepMap RSLC C18 column (Thermo Fisher) using a vented trap-column. Peptides were separated via an HPLC gradient of 4–35% mobile phase B (0.1% HCOOH in 20% H2O and 80% ACN) developed over a 120-min period. Peptides were ionized in a Nanospray Flex ion source using a charged stainless steel needle and analyzed by MS and MS/MS in an Orbitrap Fusion quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) in DNA/Protein Resource Facility at Oklahoma State University. Intact ion m/z’s were measured in the FT sector at nominal 120,000 resolution, while MS/MS fragments were fragmented by HCD at 34% energy and their fragments analyzed in the ion trap sector. Ions were selected for MS/MS using the quadrupole (1.6 m/z width), monoisotopic precursor selection, charge state screening of ions +2 to +6, and minimum ion intensities of 5×104. Dynamic exclusion (45 sec) was used to minimize repetitive MS/MS sampling, and the scan cycle was repeated every 3 sec.

2.7. Database construction and protein identification

For peptide identification, a database named “Manduca_121119_v3” was assembled from OGS2.0 (Kanost et al., 2016), MCOT1.0 (Cao and Jiang, 2015), NCBI (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/all/GCF/000/262/585/GCF_000262585.1_Msex_1.0/GCF_000262585.1_Msex_1.0_protein.faa.gz), and a list of 545 immunity- and digestion-related genes. Peptides were identified by searching this database with MaxQuant (v1.6.10.43) (Cox and Mann, 2008) using the default settings, but with the variable modifications of Cys by acrylamide or iodoacetamide, oxidized Met, cyclization of Gln to pyroglutamate, and acetylation of protein N-termini. Protein groups were assembled by MaxQuant using principles of parsimony. Proteins are considered as identified if there is at least one unique peptide detected. Protein groups which include decoy or contaminant proteins were removed.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of digestive enzymes and related proteins in M. sexta, an overview

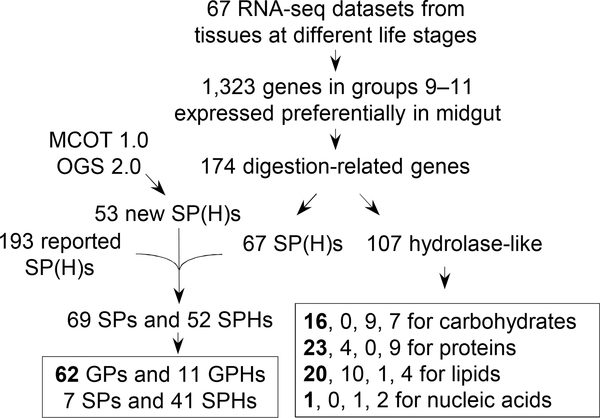

Digestive enzymes are synthesized by midgut epithelial cells and secreted into ectoperitrophic space and gut lumen to hydrolyze food ingredients during feeding stages of insects. Based on this definition, we examined a list of 1,323 genes preferentially expressed in the midgut (Cao and Jiang, 2017). Of these, group-9 genes are favorably transcribed from the 2nd instar to pre-wandering stage of the 5th instar larvae (i.e. larval feeding stages); group-10 genes are specially expressed from pre-wandering to the end of wandering stage; group-11 represents genes that are transcribed at higher levels in the pupal and adult stages. Among the genes that produce transcripts at considerable levels (i.e. FPKM >100), only a small portion encode digestive enzymes to hydrolyze the bulk of food during larval feeding stages (Fig. 1). Some genes in group-10 and −11 could be related to digestion as well, since their products may participate in midgut tissue recycling in pupae or nectar consumption in adults. Others are also expressed in midgut at lower but substantial levels in feeding larvae. For simplicity, we focus on digestion-related proteins in larval feeding stages. From the BLAST search results, we have identified 174 candidate genes in these groups and classified their protein products into hydrolases of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids.

Fig. 1.

Scheme for identification of the 122 digestive enzymes in M. sexta. As described in Section 2.1, the transcriptome analysis revealed three groups of genes favorably expressed in midgut at different developmental stages (Cao and Jiang, 2017). BLAST search indicated that 174 genes encode SPs, SPHs, and other hydrolase-related proteins. A comparison with SPs and SPHs in the MCOT1.0 and OGS2.0 assemblies (Cao and Jiang, 2015) and the 125 nondigestive and 68 digestive SPs and SPHs (Cao et al., 2015) led to the identification of 69 SPs and 52 SPHs beyond the 125 nondigestive SP(H)s. The 121 SP(H)s were divided into GP(H)s and nonGP(H)s based on their expression profiles. The other 107 hydrolase-like proteins are classified into: 1) digestive enzymes, 2) digestion-related noncatalytic proteins, 3) not digestion-specific, and 4) digestion-unrelated. Their numbers are listed in columns 1–4, respectively, with those in bold font standing for the digestive enzymes in larvae.

3.2. GPs, GPHs, and other SP-related proteins in M. sexta

The tobacco hornworm has 53 more SP(H) genes in the S1A group than reported before (Cao et al., 2015). In the previous work, we uncovered 193 SP(H)s and divided them into 68 digestive and 125 nondigestive based on the preliminary data of expression profiling. The former greatly overlapped with the SP(H)s uncovered in the transcriptome study of 15,451 OGS2.0 genes (Cao and Jiang, 2017; Table S1). Transcripts of eleven genes (GP16, 23, 29, 31, 54, 64, 67, GPH25, SP67, 95 and 137) in a group named “<9” had similar patterns to those in group-9 but were less abundant (FPKM <100 in all of the 67 libraries). We further searched MCOT1.0 (Cao and Jiang, 2015) and Manduca OGS2.0 (Kanost et al., 2016) to identify additional S1A SP-like proteins based on the domain features and found 53 new SP(H)s (SPH201–SP253, Table S1, Supplemental text). OGS2.0 models of these genes were improved using MCOT1.0 models based on Msex_1.0 genome assembly. Ten of the 53 genes lack OGS2.0 models. SPH226, 233, 235 and SP252 belong to group-9 or −<9, whereas SP251 is a group-11 member. Totally, 246 S1A SP(H) genes exist in the M. sexta genome, close to 257 in D. melanogaster (Cao and Jiang, 2018). Eighty of them (66 SPs and 14 SPHs) are in group-9 (48 and 9), −<9 (11 and 2), −10 (1 and 0), and −11 (6 and 3), respectively. In other words, nearly one third of the family members function in the midgut of M. sexta at various developmental stages.

3.2.1. Features of the 80 SP(H)s preferentially expressed in the midgut

Except for GP28, 52, GPH50, 70 and SPH235, entire sequences of the 80 SP(H)s are 244–309 residues long (average: 276 residues) (Table S1). Almost all of them are predicted to contain a signal peptide that suggests extracellular functions. Over half of the 66 SPs have trypsin-like specificity, more than chymotrypsins (18) and elastases (13). Note that the putative specificity may differ, as it has been shown that the key determinants in the S1 pocket do not always match with the actual substrate specificity (Hedstrom, 2002). Predicted proteolytic activation sites of the 66 SPs are almost all located between Arg and Ile and, thus, a minute amount of trypsin is anticipated to rapidly generate a mixture of trypsins, chymotrypsins, and elastases.

While 59 of these gut SPs are expressed during larval feeding stages, transcripts of 14 SPHs are detected in group-9 (GPH7, 41, 50, 60, 70, SPH128, 135, 226, 233), −<9 (GPH25, SPH235), 11 (SPH79, 96, 139). Except for GPH50, 70, SPH135 and 233, all the gut SPHs have a cleavage site between Arg and Ile/Val-Val/Ala/Ile-Gly-Gly (Table S1), indicative of functional importance because, otherwise, these sites would have deteriorated beyond recognition before long. Cleavage-induced conformational change occurs during zymogen activation of S1A SPs (Shibata et al., 2018). The liberated N-terminal hydrophobic residues move from the surface to an internal site where its cationic amino group forms an ion pair with the invariant Asp before the active site Ser, leading to proper formation of the enzyme specificity pocket and oxyanion hole. We suspect that similar conformational change in the SPHs, induced by cleavage at the conserved site and insertion of the new N-terminus, likely associates with their functions (unrelated to catalysis).

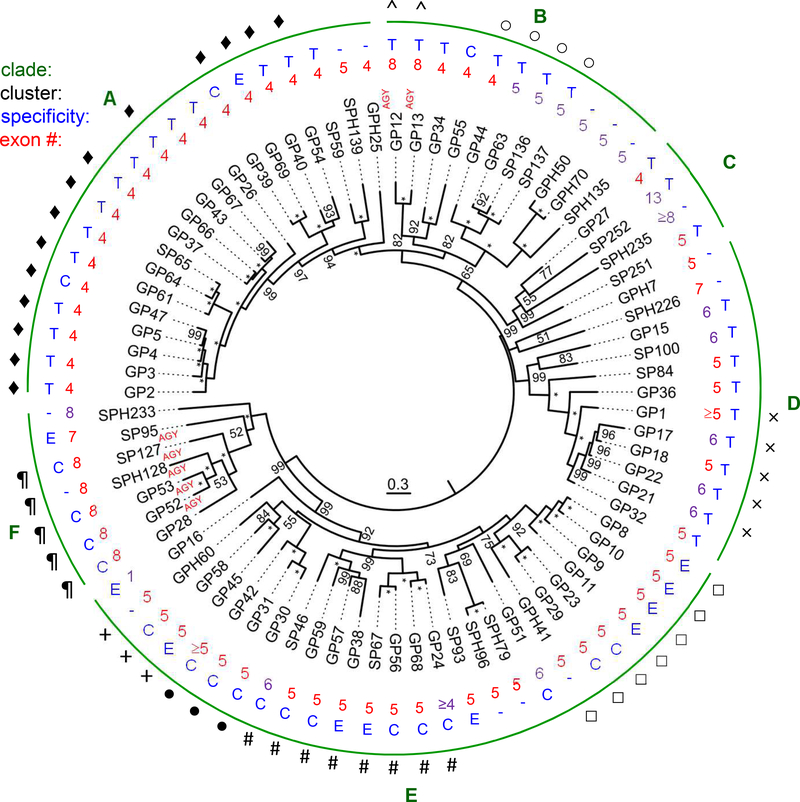

3.2.2. Phylogenetic relationships of the 80 GP(H)s and other related findings

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree construction led to division of the 80 SP(H) genes into six clades (Fig. 2): GP1 through GPH25 in clade A (20), GP12 through SPH135 in B (11), GP27, SP252, SPH235 and SP251 in C (4), GPH7 through GP32 in D (12), GP8 through GP16 in E (26), and GP28 through SPH233 in F (7). In each clade, most members possess similar features including exon number, enzyme specificity, codon of active site Ser, and genome location. For instance, 19 and 22 genes in the clades A and E contain 4 and 5 exons, respectively. While 15 clade A genes encode trypsin-like SPs, 22 clade E genes code for elastases or chymotrypsins (none for trypsin). Specificities of elastases and chymotrypsins overlap but not with trypsins. Apart from GP55, 21 SPs in clades B, C and D all have trypsin-like specificity and they are more similar to the trypsins in clade A than to members of clades E and F. In clade F, SP95 gene has 7 exons, the other six SP(H)s have 8, and they encode four chymotrypsins, one elastase and two SPHs. Of the 80 SP(H)s, seven use AGY (Y: C/T) codon for the active site Ser residue (5 in clade F; 2 in clade B) and the other 73 use TCN (N: A/T/C/G) codon (or its derivatives in SPHs). We identified nine gene clusters including GP12–13, GP44–63-SP136–137, and GP1–17-18–22-21 (Fig. 2). Residing in the genome contigs 9016–9021 (data not shown), the largest cluster consists of 18 genes coding for GP2−5, 37, 39, 40, 43, 47, 54, 61, 64, 69, SP65, 66, 63, 62, and 47. The last four had low FPKM (<10) in all the midgut libraries and were thus classified as nondigestive SPs in expression groups A and D (Cao et al., 2015). Probability values of 84–100% provided strong support for the phylogenetic relationships among members of the gene clusters (Fig. 2). While GPH50–70 and SPH79–96 pairs arose from recent gene duplications, their ancestors and the other ten SPH genes are located close to the root. In other words, they derived from SPs so long ago that mutation should have already ruined the R*IVGG region unless it has a cleavage-induced change needed for noncatalytic functions.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree from MrBayes analysis of the 80 M. sexta SP(H) preferentially expressed in midgut. As described in Section 2.4, entire protein sequences of the SP(H)s were aligned for constructing the tree. Percentages of Bayesian posterior probabilities are shown at the nodes, with “*” representing 100. Branch lengths represent expected substitution rates per site. AGY (Y: C/T) codons for the active site Ser are indicated whereas TCN (N: A/C/G/T) codons for this residue are not shown. Numbers of exons for each gene are labeled in red font. Predicted enzyme specificity of SPs is indicated in blue font: “T” for trypsin, “C” for chymotrypsin, “E” for elastase, and “−” for SPHs that lack an amidase activity. Members of a gene cluster are marked with ♦, ^, ○, ×, □, #, ●, +, or ¶. Six clades (A–F) are indicated in green font.

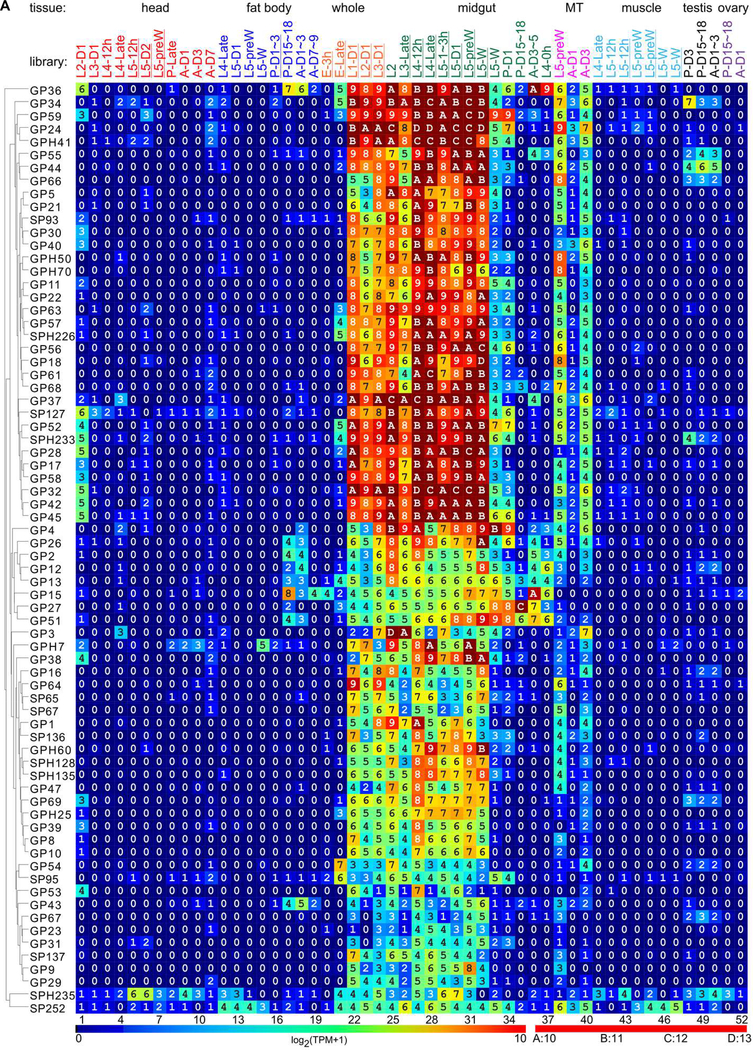

3.2.3. Expression profiles of the 80 GP(H)s

GPs and GPHs fall into two expression groups with similar characteristics (Fig. 3A). The group of high expression (GP36 to GP45) consists of 34 genes whose TPM values were in the range of 29 and 213 in the midgut tissues from 2nd instar feeding larvae to 5th instar wandering larvae. Their mRNA levels were so high that similar TPM values were observed in whole larvae from the 1st to 3rd instar. The transcripts of GP34, 36, 57, 52, SPH226, and 233 were detected in late embryo. In another midgut sample from wandering larvae, a major drop of mRNA levels to 22 and 26 was observed in 32 of the 34 genes. While sequencing methods differ, sample difference is more likely responsible for the drop. Around the time larvae cease to feed, a small difference in sampling time appear to have greatly impacted the results. Expression of these genes is generally low in the pupal and adult stages. This expression pattern strongly correlates with the feeding behavior of M. sexta. In the group of low expression (GP2 to SP252, 38 genes), TPM values are mostly in the range of 24 and 28. Their preferential expression in midgut is still obvious in the feeding stages.

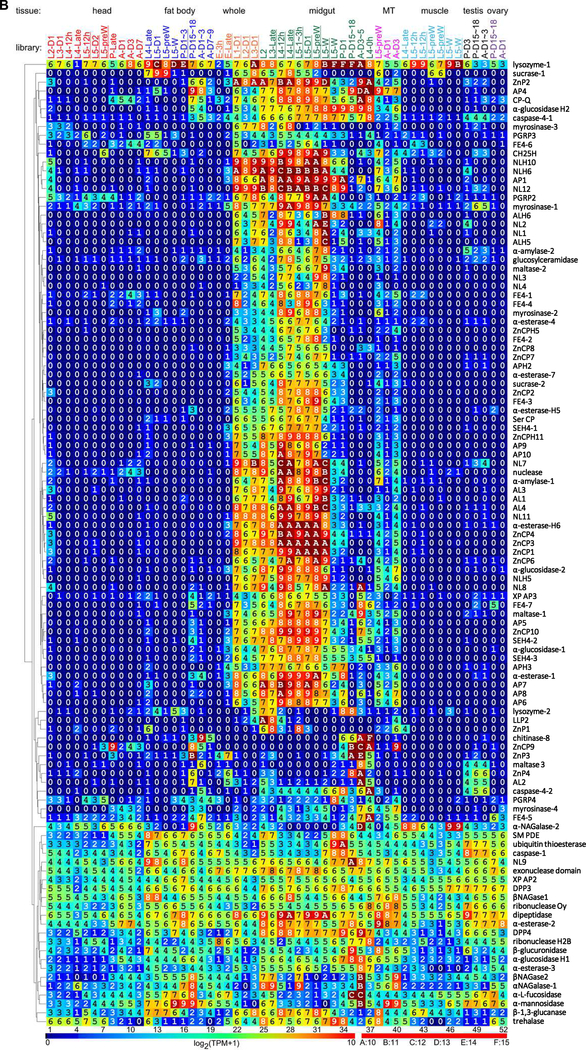

Fig. 3.

Gene expression profiles of the 61 GPs and 11 GPHs (A) and 107 other hydrolases and homologs (B) in various tissues and stages of M. sexta. The first part of the library names indicates major stages of the insect, embryo (E), 1st to 5th instar larvae (L1–L5), pupae (P), and adults (A). In the second part, “D” stands for day, “h” for hour, “preW” for pre-wandering, and “W” for wandering. As shown on the left, order of the proteins represents their relatedness in expression pattern, as revealed by the cluster analysis. Log2(TPM+1) values for the transcripts are shown in the gradient heat map from dark blue (0) to red (≥10). The values of 0~0.49, 0.50~1.49, 1.50~2.49, … 8.50~9.49, 9.50~10.49, …, 14.50~15.49 are labeled as 0, 1, 2, … 9, A, …, F, respectively. The other hydrolase-related genes are listed as abbreviations on the right of panel B (see Table S2 for full names).

3.3. Proteases and their homologs from other families

We identified 36 other protease-related genes in the expression groups 9–11 (Table S2), 23 encoding proteases. Serine proteases include a CP (standing for carboxypeptidase rather than Cys protease) in S10 family and a dipeptidyl peptidase in S9B subfamily; Cysteine proteases are three C14A caspases and one C85 ubiquitin thioesterase; Metalloproteases include eight M1 aminopeptidases (APs) and two homologs, two M24B Xaa-Pro APs, four M12A zinc endopeptidases, nine M14 zinc CPs and two homologs, one M20 dipeptidase, one M28 CP, and one M49 dipeptidyl peptidase. No aspartic protease is found in the midgut groups. The C14A, C85, M20, and M49 peptidases lack a signal peptide and, hence, are not directly related to food digestion. Midgut expression of caspase-4–1 and −4–2 in the feeding through adult stages (Fig. 3B) is likely involved in apoptosis of damaged epithelial cells (Napoleão et al., 2019).

Structural features and expression patterns provided functional insights into these proteins. The finding of M1 and M14 homologs indicates that loss of catalytic residue(s) is not limited to S1A SPs. Noncatalytic homologs may participate in digestion by means other than peptide hydrolysis (Section 4.2). ZnCP9, one of the eight M14s, contains all the key residues for catalytic activity (Table S2) but, unlike the other seven, is not produced in the larval feeding stages. It is highly expressed in late pupae and adults perhaps for tissue remodeling and/or digestion of proteins in nectar. In addition to these CPs, Zn proteases 1–4 in subfamily M12A and AP1, 4–10 in family M1 may hydrolyze dietary proteins.

3.4. Lipases, serine esterases, and their noncatalytic homologs

Thirty-five genes in expression groups 9–11 encode proteins for lipid hydrolysis. These include nine neutral lipases (NLs) and three homologs (NLHs), four acidic lipases (ALs) and two homologs (ALHs), twelve serine esterases (SEs) and five homologs (SEHs) (Table S2). As a special group of SEs, ALs may only hydrolyze triacylglycerols whereas NLs account for most of the lipase activity for phospholipid and galactolipid digestion in lepidopteran midgut (Christeller et al., 2011). Other SEs include esterases of ferulates, acetylcholine, juvenile hormones, and other carboxylic acid esters. Neutral and acidic lipases hydrolyze water-insoluble long-chain triacylglycerols; esterases act on water-soluble short acyl chain esters; their homologs lack the catalytic residue(s) for cleavage of carboxyl ester bonds but may somehow affect lipid binding or digestion. All these proteins adopt an α/β hydrolase fold comprising 8 β-strands and 6 α-helices surrounding the β-sheet (Casas-Godoy et al., 2018). While thirty-one genes belong to group-9 that well associates with digestion, AL2, NL9, α-esterase-3, and feruloyl esterase FE4–7 in group-11 displayed no or low preferential expression in midgut of the feeding larvae (Fig. 3B). Lacking a signal peptide, α-esterase-1 and −2 may not digest dietary esters but may detoxify allelochemicals or insecticides inside epithelial cells (Wang et al, 2015; Guillemaud et al, 1997). The preferential transcription of α-esterase-1 in feeding larvae is more pronounced than α-esterase-2 or −3. In general, lipase mRNAs are several fold higher than other esterases’. This seems consistent with a higher content of neutral lipids and phospholipids than short-chain flavor esters in plant leaves (Lin and Oliver, 2008; Roughan and Batt, 1969).

M. sexta neutral lipases 1−4, 7−9, 11, 12, H. armigera NL, and B. mori NL2 (Fig. S2A) contain a G(F/H/Y)SLG region conserved in pancreatic lipases (e.g. Equus caballus NL) of mammals. Ser residue in the motif forms a catalytic triad with Asp and His at the conserved sites. Substitution of the Ser with Gly in NLHs 5, 6 and 10 likely abolishes the lipase activity. M. sexta acidic lipases 1−4 and H. armigera AL (Fig. S2B) contain a G(H/F)SQG motif found in gastric lipases (e.g. human AL1) of mammals. While the active site Ser exists, M. sexta ALH5 and 6 lack the Asp and His residues for catalysis to occur, due to a truncation at the carboxyl-terminus.

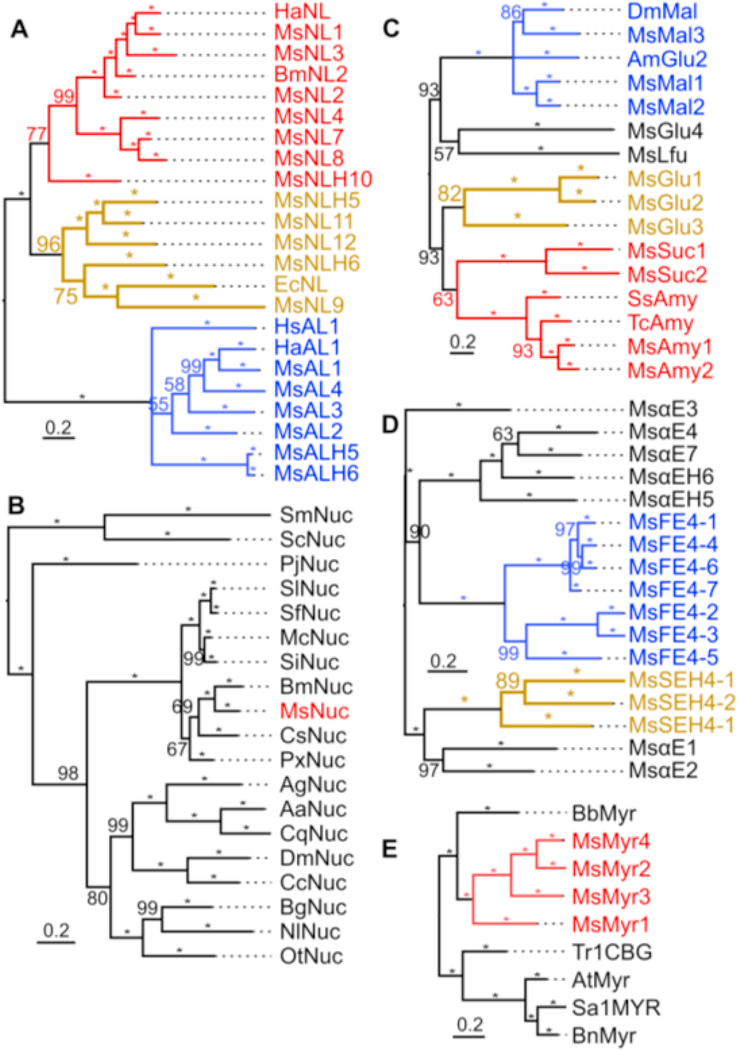

In a phylogenetic tree of the lipases (Fig. 4A), NLs and ALs along with respective homologs belong to two distinct groups, suggesting their divergence occurred long before the separation of vertebrates and invertebrates, since insect NLs and ALs are closer to mammalian pancreatic and gastric lipases, respectively. Yet, both groups of lipases have the same oxyanion hole (Casas-Godoy et al., 2018) and are in the same class (http://www.led.uni-stuttgart.de). The other SE-related proteins in M. sexta display complex phylogenetic relationships (Fig. 4D) and some levels of sequence conservation around their active sites (Fig. S3). The thirty-five lipase- and SE-like proteins account for a small portion of the SE homologs encoded by the genome (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic trees of lipase-related proteins (A), nucleases (B), carbohydratases (C), serine esterase-related proteins (D), and myrosinases (E) from M. sexta and other organisms. Based on the sequence alignments (Figs. S2–S5), phylogenetic trees were constructed using MrBayes v3.2.6. Probability values are indicated on top of branches, with “*” representing 100; major taxonomic or protein groups are shown in different colors. Abbreviations are indicated in the corresponding supplemental figures.

3.5. Carbohydrate hydrolases and their noncatalytic homologs

We identified a total of 32 carbohydratase-related proteins in group-9−11 (Table S2), including two α-amylases, two α-glucosidases, three maltases, two sucrases, one trehalase, two lysozymes, three peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs), and one β−1,3-glucanase. Based on expression profiles of these genes (Fig. 3B), sixteen encode digestive enzymes (Fig. 1).

As members of glycoside hydrolase family 77 (GH77), α-amylases hydrolyze α−1,4-glycosidic bonds of glycogen, starch, and related polysaccharides. Over-production of amylases may protect insects from plant amylase inhibitors (Franco et al., 2002). M. sexta α-amylase-1 mRNA levels are about ten-fold higher than α-amylase-2’s during feeding stages (Fig. 3B). Both proteins contain a (β/α)8-barrel domain A with a catalytic triad of Asp, Glu and Asp (Fig. S4), an N-terminal Ca2+-binding domain B, and a C-terminal domain C with a Greek key motif.

M. sexta α-glucosidase-2 mRNA levels are twice as high as α-glucosidase-1’s. Both α-glucosidase homolog-1 and −2 lack signal peptide and at least one catalytic residue. The former is widely distributed in other tissues, the latter is mainly limited to midgut, and both are favorably produced in midgut cells perhaps for carbohydrate transport, a process that may concur with food digestion in gut lumen and ectoperitrophic space. Maltases, named after their preferred substrate maltose, are the most abundant form of insect α-glucosidases. M. sexta maltase-1 mRNA levels are four-fold higher than maltase-2’s (Fig. 3B). As maltase-3 TPM value in the midgut of feeding larvae is so low but reaches 25−8 in late pupae and young adults, we suspect it is an adult-specific enzyme that digests sucrose in nectar. Sucrase-1 and −2 hydrolyze sucrose to glucose and fructose. Their transcript levels are comparable in larval feeding stages but sucrase-2 mRNA levels are maintained in the pre-wandering and wandering stages. As a result of midgut alkalinity, sucrases are not inhibited by alkaloid sugars (Daimon et al, 2008).

Trehalase hydrolyzes trehalose, a nonreducing sugar of two glucose units linked by an α−1,1-glycosidic bond. Apical trehalase might have a role in food digestion while basal trehalase utilizes trehalose in hemolymph (Terra and Ferreira, 2012). M. sexta trehalase expression profile cannot distinguish these roles (Fig. 3B) but the enzyme is not detected in the midgut digestive juice (Table S2). While the trehalase transcripts in midgut are considerably more abundant than in fat body and muscles during the larval feeding stages, the mRNA peak was reached in midgut of wandering larvae and new pupae. The detection of its mRNA in head and several other tissues in various life stages suggests that trahalase is required by all these tissues (including midgut) to utilize trehalose in the hemolymph.

Lysozymes cleave β−1,4-glycosidic bonds in the glycan strands of bacterial peptidoglycans (PGs); certain PGRPs hydrolyze the lactylamide bond between N-acetylmuramic acid and L-Ala in the stem peptide (Mellroth et al., 2003). β−1,3-glucanase hydrolyzes plant callose as well as fungal cell wall. M. sexta lysozymes and PGRP2−4 may digest cell wall of bacteria (He et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2005). We think PGRP2, PGRP3, and β−1,3-glucanase are digestive enzymes, based on their elevated mRNA levels in midgut of feeding larvae (Fig. 3B). It is possible that killing pathogens via digestion is a natural defense mechanism of insects.

Myrosinases are β-thioglucosidases that hydrolyze glucosinolates, compounds plants make to fight herbivores and diseases (Winde and Wittstock, 2011). M. sexta myrosinase-1 and −2 are made in all larval feeding stages; myrosinase-3 mRNA exists in midgut of 1st−4th instar; myrosinase-4 is produced in adult midgut and Malpighian tubules (Fig. 3B). While some hydrolytic products of glucosinolates are toxic, M. sexta, as a specialist, must have developed ways to detoxify or at least tolerate isothiocyanates as it harvests glucose from their precursors. While catalytic residues of the plant myrosinases are Gln and Glu (Fig. S5), the equivalent residues in the cabbage aphid and tobacco hornworm are both Glu (Barrett et al., 1995; Jones et al., 2002; Bhat et al., 2019).

3.6. Nucleases and alkaline midgut

Four putative nucleases are identified in the three gut-specific groups (Table S2). Two lack signal peptide, RNase Oy does not display any expression association with larval feeding, but the last one is expressed in midgut of larvae in the feeding stages (Fig. 3B). Its ortholog in the silkworm hydrolyzes single- and double-stranded DNA and RNA (Arimatsu et al., 2007a). Since DNA strands separate and RNA molecules undergo autolysis at a high pH, its natural substrate is likely single stranded DNA. The putative nuclease and its orthologs in the lepidopterans form a tight monophyletic group distinct from the homologs in other orders of insects (Fig. 4B).

3.7. Identification of digestion-related proteins in midgut juice of M. sexta feeding larvae

To test if the 122 hydrolases and 25 noncatalytic homologs are digestion-related, we collected fluid in the ectoperitrophic space of 5th instar feeding larvae. SDS-PAGE analysis showed most of the proteins are smaller than 50 kDa (Fig. S6A) and no distinct band was detected at the positions of storage proteins or lipophorins, major hemolymph proteins in this stage. Thus, contamination of hemolymph was minimal. We identified 131 of the 147 proteins in the sample by LC-MS/MS analysis (Tables S1 and S2). For the ones with transcriptome and proteome data, a low correlation was observed between log2(TPM+1) and log2(LFQ+1) values (Fig. S6B). A similar discordance was observed and examined in details between plasma protein levels and their mRNA levels in hemocytes and in fat body (He et al., 2016). Of the sixteen proteins not identified in the gut juice (GP5, 13, 15, 16, 23, 29, 53, SP95, 252, SPH235, ZnP1, AL1, AL3, AL4, PGRP3, and myrosinase-3), TPM values of GP5, AL1, AL3, and AL4 gene transcripts were >26 in the midgut sample at the corresponding stage of feeding larvae (Fig. 3). Low expression of the other genes may account for their protein levels below the detection limit. The acidic lipases may digest lipids taken up by gut epithelial cells (Section 4.3). In summary, preferential genes expression in midgut of larval feeding stages and examination of structural features (e.g. signal peptide) yielded a rate of >95% success in predicting digestion-related proteins.

4. Discussion

4.1. Elucidation of a midgut digestive enzyme system in feeding larvae of M. sexta

Digestive enzymes account for a small number of proteins made by midgut epithelial cells. In addition to the gene products that maintain basic cellular functions, proteins are produced for gut-specific processes, such as digestion, defense, and detoxification (Pauchet et al., 2010). While the epithelial cells secret soluble proteins or enzymes into gut lumen to build up peritrophic membrane and hydrolyze food ingredients, these cells may also contribute to the pool of hemolymph proteins via basal lamina (Palli and Locke, 1987). As such, when genome sequence and gut transcriptome data are available, cautions need to be practiced to correctly identify digestive enzymes.

We adopted a combined approach to define a complete set of digestive enzymes from M. sexta. Our transcriptome analysis yielded three groups of gut-specific genes expressed in various life stages (Cao and Jiang, 2017). With the first group closely linked to the larval feeding stages, the other two are much less correlated with food digestion. A BLAST search allowed us to select 174 digestion-related genes for further characterization (Fig. 1). By examining SP(H)s from different sources, we identified gut SPs as candidates of major endopeptidases of dietary proteins. We also examined expression patterns, signal peptides, and catalytic residues of other peptidases, lipases, nucleases and carbohydrate hydrolases. The LC-MS/MS analysis finally validated the existence of 107 digestive enzymes and 24 noncatalytic homologs in the gut secretion from the feeding larvae. Together, the results revealed major components of the entire system of digestive enzymes in M. sexta. This framework of information from a model species constitutes a foundation for studying their counterparts in lepidopteran pests and for future development of inhibitors for crop protection.

High-sensitivity mass spectrometry provided insights into other aspects of the ectoperitrophic fluid. Of the 3,428 protein hits, 1,958 had LFQ values higher than 1.02×106, the lowest intensity in a group of the 120 digestive enzymes and homologs. Based on homology with previously studied proteins, some of the 1,838 other proteins came from cytosol (>90), mitochondria (>121), lysosomes (>3), and peroxisomes (>5). This indicates the sample contained intracellular proteins and subcellular organelles, released from lysed epithelial cells undergoing apoptosis and/or damaged tissues during dissection. Additionally, 54 abundant hemolymph proteins were observed in the digestive juice at levels much lower than those in plasma (data not shown). In contrast, we did not detect AL1, AL3 and AL4 (TPM >26) in the digestive juice. In summary, a part of the proteome complexity may come from contamination.

4.2. A possible role for noncatalytic homologs of digestive enzymes

One surprising result from this study is the detection of proteins that resemble S1A gut serine proteases, M1 aminopeptidases, M14 carboxypeptidases, lipases, and other serine esterases, but lack one or more of their catalytic residues. Do these proteins have functions unrelated to substrate hydrolysis? Expression profiles of the 6 GPH, 5 SPH, 2 APH, 2 CPH, 3 NLH, 2 ALH, and 5 SEH genes displayed close association with feeding, their mRNA levels comparable to the homologous enzymes (Fig. 3), and their proteins detected in the digestive juice (Fig. S6). Early divergence of the enzymes and respective homologs, as exhibited in the phylogenetic trees (Fig. 4), suggests that the homologs are functional because, otherwise, their genes would deteriorate and become inactive pseudogenes. In the case of SPHs, conservation of the proteolytic activation sites (R*IVGG) in most GPHs and fewer SPHs indicates that cleavage at these locations is likely needed for their functions. Based on the conformational change of SP zymogen activation (Shibata et al., 2018), we indicate that a similar change may occur in cleaved GPHs to enable binding of normal substrates or poorly hydrolyzed molecules (e.g. protease inhibitors). While preferential association with inhibitors by GPHs is not yet confirmed, a certain level of inhibitor sequestration likely protects GPs from inactivation and host from indigestion.

4.3. Possible adaptation to alkaline pH of midgut

In holometabolous insects, neutral and acidic lipases are mainly responsible for hydrolyzing tri-, di-, and mono-acylglycerols, phospholipids, and galactolipids (Horne et al, 2009). But it is not clear how both groups of lipases may efficiently hydrolyze lipids at a particular pH. In lepidopteran insects, NLs may adapt to a high pH but how may ALs change their optimal pH? We first examined whether there is a global down-regulation of AL transcription and found, except for AL2, the average mRNA levels of ALs or ALHs are comparable to those of NL(H)s (Fig. 3B). Remarkably, none of the four ALs was detected in the gut juice but LFQs of ALH5 and ALH6 were 2.31×107 (Table S2). In contrast, LFQs of eight NLs and three NLHs encompass 1.02×106 and 2.38×109. Only NL9, a group-11 member like AL2, was not found in the larval digestive fluid. We suggest that AL1, AL3 and AL4 function as digestive enzymes but, instead of working at an unfavorable pH, they may be transported into acidic lysosomes to digest lipids taken up by midgut epithelial cells through endocytosis. According to Dow (1992), pH values of the first seven midgut sections in a total of nine are above 9.3 and peaks at 11.2 in the 5th section. It would be interesting to test this hypothesis and compare the results with insects that have a neutral or acidic midgut.

Another example of adaptation to alkaline midgut could be the nuclease whose expression well correlates with larval feeding. While natural substrates are unclear for this enzyme, we predict it is a single-stranded deoxyribonuclease (ssDNase) based on behaviors of DNA and RNA at a high pH of 10.5 and nutritional value of nucleic acids to insects. Our premise is to some extent supported by two studies, one in Bombyx mori (Arimatsu et al., 2007a) and the other in Choristoneura fumiferana (Schernthaner et al., 2002). The 41 kDa silkworm enzyme hydrolyzes dsRNA, ssRNA, but not dsDNA at a pH of 7–10. However, knowing the enzyme has an optimal pH >11, the authors did not report ssDNA as a potential substrate. cDNA cloning indicates that it is a pre-pro-enzyme activated by cleavage between Arg65 and Ser66, homologous to a dsRNase of Serratia marcescens (Arimatsu et al., 2007b), and has close orthologs in other lepidopterans (Fig. 4B). A digestive DNase with a pH optimum of 10–10.5 was isolated from digestive tract of the spruce budworm (Schernthaner et al., 2002), which cleaves single- and double-stranded DNA. The purified enzyme has a molecular mass of 23 kDa and an N-terminal sequence highly similar to C. fumiferana trypsin-1. Recombinant expression of the M. sexta nuclease in insect cells is needed to characterize the putative ssDNase in terms of optimal pH and substrates.

4.4. Additional information on digestion-related proteins

Considering some digestion-related genes may have been missed due to the FPKM threshold of 100 (Section 2.1), we did a BLAST search of the OGS2.0 (Kanost et al., 2016) and MCOT1.0 (Cao and Jiang, 2015) models using all of the protein sequences in Table S2 and an identity cutoff of >60%. Of the 43 hits, we removed redundancy, checked their expression profiles and presence in the midgut proteome, and enlisted their mRNA levels, protein abundances, and structural features in Table S3. According to their digestive enzyme-relatedness indexes, 11 of the 23 newly identified proteins are related to digestion (Supplemental text). They are ZnCP12, NL13, NLH14, FE4–8, 9, 11–13, and myrosinase-5–7. Since the mRNA and protein levels are low or very low, their contribution to digestion is expected to be minor. With these eleven proteins included, the total counts of digestive enzymes and their noncatalytic homologs reach 132 and 26, respectively.

The genome, transcriptome, and proteome data indicate that similar hydrolases of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids are present in M. sexta and other insects studied. No special nutritional requirements appear to exist at the omic levels, supporting the tobacco hornworm’s role as a relevant model for studying similar enzymes in lepidopteran pests. Adaptation to solanaceous plants is less related to digestion than to detoxification. The latter, beyond the scope of this study, has been covered in the genome study (Kanost et al., 2016). M. sexta, unlike insects specialized in wood or fruit feeding, does not have any gene coding for cellulase, xylanase, or pectinase. Yet, at the transcription level, evidence for differential gene regulation is strong between leaf-chewing larvae and nectar-sipping adults (Fig. 3). In summary, this evidence-based study provides a good reference for comparative studies in agricultural pests from the order of Lepidoptera.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Expression profiles of the 49 newly identified SP(H) genes unrelated to food digestion. Tissues, stages, and library IDs (1−52) are color coded as described in Fig. 3 legend.

Fig. S2. Aligned sequences of the neutral (A) and acidic (B) lipase-related proteins from M. sexta and other animals. Equus caballus neutral or pancreatic lipase (EcNL, NP_001157421.1), H. armigera NL (XP_021186848.1), B. mori NL2 (XP_004929630.1), M. sexta NL(H)s, Homo sapiens acidic or gastric lipase-1 (HsAL1, NP_001185758.1), H. armigera AL1 (XP_021181637.1), and M. sexta AL(H)s. Green font denotes residues of signal peptide; red font denotes conserved catalytic residues.

Fig. S3. Sequence alignment of the serine esterase-related proteins expressed in M. sexta midgut. Sequences of α-esterases (αEs), feruloyl esterases (FEs), and their homologs are aligned. Green font denotes signal peptides; red font denotes conserved catalytic residues.

Fig. S4. Aligned sequences of α-amylases, α-glucosidases, maltases, sucrases, and α- L-fucosidase from M. sexta and other animals. Sus scrofa pancreatic α-amylase (XP_003125929.2), T. castaneum α-amylase (NP_001107848.1), D, melanogaster maltase A1 (NP_476627.3), Apis mellifera α-glucosidase-2 (NP_001035326.1) are aligned with their M. sexta homologs. Green font denotes signal peptides; red font denotes conserved catalytic residues.

Fig. S5. Multiple sequence alignment of myrosinases from M. sexta and other species. Myrosinases of Sinapis alba (P29092.2), Arabidopsis thaliana (P37702), Trifolium repens (P26205), Brassica napus (Q00326), and Brevicoryne brassicae (AAL25999.1) are aligned with their homologs in M. sexta. Green font denotes signal peptides; red font denotes conserved catalytic residues.

Fig. S6. SDS-PAGE and LC-MS/MS analysis of digestive fluid from feeding larvae of M. sexta. (A) Coomassie staining. Proteins (3 μg) in midgut juice from day 1, 5th instar larvae were treated with SDS-sample buffer, separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, and stained with Coomassie blue. Positions and sizes of the Mr makers are indicated on the left. (B) Correlation of mRNA and protein levels. Values of log2(TPM+1) and log2(LFQ+1), representing relative mRNA and protein levels, respectively, are plotted and subjected to a linear regression analysis. The equation and correlation coefficient (r2) are shown.

Highlights.

Identification of a complete set of 122 digestive enzyme genes in a model lepidopteran species

Discovery of 53 new serine protease-related proteins making 246 size of the entire family

Evidence-based classification and verification of digestive enzymes and related proteins

Enzyme characterization via sequence comparison, domain search, and catalytic site detection

At least 131 or 89% of these proteins are identified in ectoperitrophic fluid from feeding larvae

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Estela Arrese in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Oklahoma State University for an insightful discussion on insect lipases and suggestion of a proteomics study of digestive juice from feeding larvae. Dr. Steve Hartson and Mrs. Janet Rogers kindly provided supports for the LC-MS/MS analysis. This study was supported by NIH grants GM58634 and AI139998. The paper was approved for publication by the Director of Oklahoma Agricultural Experimental Station and supported in part under project OKL03054.

Abbreviations

- AL and ALH

acidic lipase and homolog

- AP and APH

aminopeptidase and homolog

- αNAGalase

α-N-acetyl galactosaminidase

- βNAGase

β-N-acetylglucosaminidase

- CP and CPH

carboxypeptidase and homolog

- DPP

dipeptidyl peptidase

- FE

feruloyl esterase

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads

- GH

glycoside hydrolase

- GP and GPH

gut serine protease and homolog

- LFQ

label-free quantification

- LLP

lysozyme-like protein

- NL and NLH

neutral lipase and homolog

- PGRP

peptidoglycan recognition protein

- SE and SEH

serine esterase and homolog

- SP and SPH

serine protease and homolog

- ssDNase

single stranded DNA 3’−5’ exonuclease

- TAG

triacylglycerol

- TPM

transcripts per kilobase million

- ZnCP

zinc carboxypeptidase

- ZnP

zinc protease

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arimatsu Y, Furuno T, Sugimura Y, Togoh M, Ishihara R, Tokizane M, Kotani E, Hayashi Y, Furusawa T, 2007a. Purification and properties of double-stranded RNA-degrading nuclease, dsRNase, from the digestive juice of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J. Insect Biotechnol Sericol. 76, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Arimatsu Y, Kotani E, Sugimura Y, Furusawa T, 2007b. Molecular characterization of a cDNA encoding extracellular dsRNase and its expression in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 37, 176–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T, Suresh CG, Tolley SP, Dodson EJ, Hughes MA, 1995. The crystal structure of a cyanogenic β-glucosidase from white clover, a family 1 glycosyl hydrolase. Structure 3, 951–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat R, Vyas D, 2019. Myrosinase: insights on structural, catalytic, regulatory, and environmental interactions. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 39, 508–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brioschi D, Nadalini LD, Bengtson MH, Sogayar MC, Moura DS, Silva-Filho MC, 2007. General up regulation of Spodoptera frugiperda trypsins and chymotrypsins allows its adaptation to soybean proteinase inhibitor. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 37, 1283–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canton PE, Cancino-Rodezno A, Gill SS, Soberón M, Bravo A, 2015. Transcriptional cellular responses in midgut tissue of Aedes aegypti larvae following intoxication with Cry11Aa toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis. BMC Genomics. 16, 1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, He Y, Hu Y, Zhang X, Wang Y, Zou Z, Chen Y, Blissard GW, Kanost MR, Jiang H, 2015. Sequence conservation, phylogenetic relationships, and expression profiles of nondigestive serine proteases and serine protease homologs in Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 62, 51–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Jiang H, 2015. Integrated modeling of protein-coding genes in the Manduca sexta genome using RNA-Seq data from the biochemical model insect. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 62, 2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Jiang H, 2017. An analysis of 67 RNA-seq datasets from various tissues at different stages of a model insect, Manduca sexta. BMC Genomics 18, 796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Jiang H, 2018. Building a platform for predicting functions of serine protease-related proteins in Drosophila melanogaster and other insects. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 103, 53–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas-Godoy L, Gasteazoro F, Duquesne S, Bordes F, Marty A, Sandoval G, 2018. Lipases: an overview. Methods Mol Biol. 1835, 3–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Mann M, 2008. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daimon T, Taguchi T, Meng Y, Katsuma S, Mita K, Shimada T, 2008. β-fructofuranosidase genes of the silkworm, Bombyx mori: insights into enzymatic adaptation of B. mori to toxic alkaloids in mulberry latex. J Biol Chem. 283, 15271–15279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison NJ, Saraiva RG, Cirimotich CM, Mlambo G, Mongodin EF, Dimopoulos G, 2016. Functional genomic analyses of Enterobacter, Anopheles and Plasmodium reciprocal interactions that impact vector competence. Malar J. 15, 425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow JA 1992. pH gradients in lepidopteran midgut. J Exp Biol. 172, 355–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn PE, Drake DR, 1983. Fate of bacteria injected into naive and immunized larvae of the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta. J Invertebr Pathol. 41, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta D, Dobson AJ, Houtz PL, Gläßer C, Revah J, Korzelius J, Patel PH, Edgar BA, Buchon N, 2015. Regional cell-specific transcriptome mapping reveals regulatory complexity in the adult Drosophila midgut. Cell Rep. 12, 346–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco OL, Rigden DJ, Melo FR, Grossi-De-Sá MF, 2002. Plant α-amylase inhibitors and their interaction with insect α-amylases. Eur J Biochem. 269, 397–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemaud T, Makate N, Raymond M, Hirst B, Callaghan A, 1997. Esterase gene amplification in Culex pipiens. Insect Mol Biol. 6, 319–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Cao X, Li K, Hu Y, Chen Y, Blissard GW, Kanost MR, Jiang H, 2015. A genome-wide analysis of antimicrobial effector genes and their transcription patterns in Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 62, 23–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Cao X, Zhang S, Rogers J, Hartson S, Jiang H, 2016. Changes in the plasma proteome of Manduca sexta larvae in relation to the transcriptome variations after an immune challenge: evidence for high molecular weight immune complex formation. Mol Cell Proteomics 15, 1176–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedstrom L, 2002. Serine protease mechanism and specificity. Chem Rev. 102, 4501–4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne I, Haritos VS, Oakeshott JG, 2009. Comparative and functional genomics of lipases in holometabolous insects. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 39, 547–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AME, Winge P, Bones AM, Cole R, Rossiter JT, 2002. Characterization and evolution of a myrosinase from the cabbage aphid Brevicoryne brassicae. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 32, 275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P, Binns D, Chang H-Y, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, McWilliam H, Maslen J, Mitchell A, Nuka G, Pesseat S, Quinn AF, Sangrador-Vegas A, Scheremetjew M, Yong S-Y, Lopez R, Hunter S, 2014. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakumani PK, Malhotra P, Mukherjee SK, Bhatnagar RK, 2014. A draft genome assembly of the army worm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Genomics 104, 134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanost MR, Arrese EL, Cao X, Chen Y, Chellapilla S, Goldsmith MR, Grosse-Wilde E, Heckel DG, Herndon N, Jiang H, Papanicolaou A, Qu J, Soulages JL, Vogel H, Walters J, Waterhouse RM, Ahn S, Almeida FC, An C, Aqrawi P, Bretschneider A, Bryant WB, Bucks S, Chao H, Chevignon G, Christen JM, Clarke DF, Dittmer NT, Ferguson LCF, Garavelou S, Gordon KHJ, Gunaratna RT, Han Y, Hauser F, He Y, Heidel-Fischer H, Hirsh A, Hu Y, Jiang H, Kalra D, Klinner C, Konig C, Kovar C, Kroll AR, Kuwar SS, Lee SL, Lehman R, Li K, Li Z, Liang H, Lovelace S, Lu Z, Mansfield JH, McCulloch KJ, Mathew T, Morton B, Muzny DM, McCulloch KJ, Mathew T, Morton B, Muzny DM, Neunemann D, Ongeri F, Pauchet Y, Pu L, Pyrousis I, Rao X, Redding A, Roesel C, Sanchez-Gracia A, Schaack S, Shukla A, Tetreau G, Wang Y, Xiong G, Traut W, Walsh TK, Worley KC, Wu D, Wu W, Wu Y, Zhang X, Zou Z, Zucker H, Briscoe AD, Burmester T, Clem RJ, Feyereisen R, Grimmelikhuijzen CJP, Hamodrakas SJ, Hansson BS, Huguet E, Jermiin LS, Lan Q, Lehman HK, Lorenzen M, Merzendorfer H, Michalopoulos I, Morton DB, Muthukrishnan S, Oakeshott JG, Palmer W, Park Y, Passarelli AL, Rozas J, Schwartz LM, Smith W, Southgate A, Vilcinskas A, Vogt R, Wang P, Werren J, Yu X, Zhou J, Brown SJ, Scherer SE, Richards S, Blissard GW, 2016. Multifaceted biological insights from a draft genome sequence of the tobacco hornworm moth, Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 76, 118–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khajuria C, Zhu YC, Chen MS, Buschman LL, Higgins RA, Yao J, Crespo AL, Siegfried BD, Muthukrishnan S, Zhu KY, 2009. Expressed sequence tags from larval gut of the European corn borer (Ostrinia nubilalis): exploring candidate genes potentially involved in Bacillus thuringiensis toxicity and resistance. BMC Genomics 10, 286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwar SS, Pauchet Y, Vogel H, Heckel DG, 2015. Adaptive regulation of digestive serine proteases in the larval midgut of Helicoverpa armigera in response to a plant protease inhibitor. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 59, 18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Dewey CN, 2011. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinf. 12, 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Xia X, Yu XQ, Shen J, Li Y, Lin H, Tang S, Vasseur L, You M, 2018. Gene expression profiling provides insights into the immune mechanism of Plutella xylostella midgut to microbial infection. Gene 647, 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Oliver DJ, 2008. Role of triacylglycerols in leaves, Plant Sci. 175, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Mellroth P, Karlsson J, Steiner H, 2003. A scavenger function for a Drosophila peptidoglycan recognition protein. J Biol Chem. 278, 7059–7064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris K, Lorenzen MD, Hiromasa Y, Tomich JM, Oppert C, Elpidina EN, Vinokurov K, Jurat-Fuentes JL, Fabrick J, Oppert B, 2009. Tribolium castaneum larval gut transcriptome and proteome: A resource for the study of the coleopteran gut. J Proteome Res. 8, 3889–3898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoleão TH, Albuquerque LP, Santos ND, Nova IC, Lima TA, Paiva PM, Pontual EV, 2019. Insect midgut structures and molecules as targets of plant-derived protease inhibitors and lectins. Pest Manag Sci. 75, 1212–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppert B, Dowd SE, Bouffard P, Li L, Conesa A, Lorenzen MD, Toutges M, Marshall J, Huestis DL, Fabrick J, Oppert C, Jurat-Fuentes JL, 2012. Transcriptome profiling of the intoxication response of Tenebrio molitor larvae to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry3Aa protoxin. PLoS One 7, e34624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppert B, Perkin L, Martynov AG, Elpidina EN, 2018. Cross-species comparison of the gut: Differential gene expression sheds light on biological differences in closely related tenebrionids. J Insect Physiol. 106, 114–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauchet Y, Wilkinson P, Vogel H, Nelson DR, Reynolds SE, Heckel DG, ffrench-Constant RH Pyrosequencing the Manduca sexta larval midgut transcriptome: messages for digestion, detoxification and defense. Insect Mol Biol. 19, 61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palli SR, Locke M, 1987. The synthesis of hemolymph proteins by the larval midgut of an insect Calpodes ethlius (Lepidoptera:Hesperiidae). Insect Biochem. 17, 561–572 [Google Scholar]

- Pearce SL, Clarke DF, East PD, Elfekih S, Gordon KHJ, Jermiin LS, McGaughran A, Oakeshott JG, Papanicolaou A, Perera OP, Rane RV, Richards S, Tay WT, Walsh TK, Anderson A, Anderson CJ, Asgari S, Board PG, Bretschneider A, Campbell PM, Chertemps T, Christeller JT, Coppin CW, Downes SJ, Duan G, Farnsworth CA, Good RT, Han LB, Han YC, Hatje K, Horne I, Huang YP, Hughes DST, Jacquin-Joly E, James W, Jhangiani S, Kollmar M, Kuwar SS, Li S, Liu NY, Maibeche MT, Miller JR, Montagne N, Perry T, Qu J, Song SV, Sutton GG, Vogel H, Walenz BP, Xu W, Zhang HJ, Zou Z, Batterham P, Edwards OR, Feyereisen R, Gibbs RA, Heckel DG, McGrath A, Robin C, Scherer SE, Worley KC, Wu YD, 2017. Genomic innovations, transcriptional plasticity and gene loss underlying the evolution and divergence of two highly polyphagous and invasive Helicoverpa pest species. BMC Biol. 15, x63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perona JJ, Craik CS, 1995. Structural basis of substrate specificity in the serine proteases. Protein Sci. 4, 337–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H, 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions Nat Methods 8, 785–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Hohna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP, 2012. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 61, 539–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughan PG, Batt RD, 1969. The glycerolipid composition of leaves. Phytochem. 8, 363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva RG, Kang S, Simões ML, Angleró-Rodríguez YI, Dimopoulos G, 2016. Mosquito gut antiparasitic and antiviral immunity. Dev Comp Immunol. 64, 53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schernthaner JP, Milne RE, Kaplan H, 2002. Characterization of a novel insect digestive DNase with a highly alkaline pH optimum. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 32, 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoville SD, Chen YH, Andersson MN, Benoit JB, Bhandari A, Bowsher JH, Brevik K, Cappelle K, Chen MM, Childers AK, Childers C, Christiaens O, Clements J, Didion EM, Elpidina EN, Engsontia P, Friedrich M, García-Robles I, Gibbs RA, Goswami C, Grapputo A, Gruden K, Grynberg M, Henrissat B, Jennings EC, Jones JW, Kalsi M, Khan SA, Kumar A, Li F, Lombard V, Ma X, Martynov A, Miller NJ, Mitchell RF, Munoz-Torres M, Muszewska A, Oppert B, Palli SR, Panfilio KA, Pauchet Y, Perkin LC, Petek M, Poelchau MF, Record É, Rinehart JP, Robertson HM, Rosendale AJ, Ruiz-Arroyo VM, Smagghe G, Szendrei Z, Thomas GWC, Torson AS, Vargas Jentzsch IM, Weirauch MT, Yates AD, Yocum GD, Yoon JS, Richards S, 2018. A model species for agricultural pest genomics: the genome of the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Sci Rep. 8, 1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata T, Kobayashi Y, Ikeda Y, Kawabata SI, 2018. Intermolecular autocatalytic activation of serine protease zymogen factor C through an active transition state responding to lipopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 293, 11589–11599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spit J, Badisco L, Vergauwen L, Knapen D, Vanden Broeck J, 2016. Microarray-based annotation of the gut transcriptome of the migratory locust, Locusta migratoria. Insect Mol Biol. 25, 745–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srp J, Nussbaumerová M, Horn M, Mareš M, 2016. Digestive proteolysis in the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata: activity-based profiling and imaging of a multipeptidase network. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 78, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terra WR, Ferreira C, 2012. Biochemistry and molecular biology of digestion In: Gilbert LI (Ed.), “Insect Molecular Biology and Biochemistry”. Academic Press, London, pp. 365–418. [Google Scholar]

- Wang LL, Huang Y, Lu XP, Jiang XZ, Smagghe G, Feng ZJ, Yuan GR, Wei D, Wang JJ, 2015. Overexpression of two α-esterase genes mediates metabolic resistance to malathion in the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel). Insect Mol Biol. 24, 467–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winde I, Wittstock U, 2011. Insect herbivore counteradaptations to the plant glucosinolate-myrosinase system. Phytochem. 72, 1566–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You M, Yue Z, He W, Yang X, Yang G, Xie M, Zhan D, Baxter SW, Vasseur L, Gurr GM, Douglas CJ, Bai J, Wang P, Cui K, Huang S, Li X, Zhou Q, Wu Z, Chen Q, Liu C, Wang B, Li X, Xu X, Lu C, Hu M, Davey JW, Smith SM, Chen M, Xia X, Tang W, Ke F, Zheng D, Hu Y, Song F, You Y, Ma X, Peng L, Zheng Y, Liang Y, Chen Y, Yu L, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Li G, Fang L, Li J, Zhou X, Luo Y, Gou C, Wang J, Wang J, Yang H, Wang J, 2013. A heterozygous moth genome provides insights into herbivory and detoxification. Nat Genet. 45, 220–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Shukle R, Mittapalli O, Zhu YC, Reese JC, Wang H, Hua BZ, Chen MS, 2010. The gut transcriptome of a gall midge, Mayetiola destructor. J Insect Physiol. 56, 1198–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, He Y, Cao X, Gunaratna RT, Chen YR, Blissard G, Kanost MR, Jiang H, 2015. Phylogenetic analysis and expression profiling of the pattern recognition receptors: insights into molecular recognition of invading pathogens in Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 62, 38–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu-Salzman K, Zeng R., 2015. Insect response to plant defensive protease inhibitors. Ann Rev Entomol. 60, 233–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Expression profiles of the 49 newly identified SP(H) genes unrelated to food digestion. Tissues, stages, and library IDs (1−52) are color coded as described in Fig. 3 legend.

Fig. S2. Aligned sequences of the neutral (A) and acidic (B) lipase-related proteins from M. sexta and other animals. Equus caballus neutral or pancreatic lipase (EcNL, NP_001157421.1), H. armigera NL (XP_021186848.1), B. mori NL2 (XP_004929630.1), M. sexta NL(H)s, Homo sapiens acidic or gastric lipase-1 (HsAL1, NP_001185758.1), H. armigera AL1 (XP_021181637.1), and M. sexta AL(H)s. Green font denotes residues of signal peptide; red font denotes conserved catalytic residues.

Fig. S3. Sequence alignment of the serine esterase-related proteins expressed in M. sexta midgut. Sequences of α-esterases (αEs), feruloyl esterases (FEs), and their homologs are aligned. Green font denotes signal peptides; red font denotes conserved catalytic residues.

Fig. S4. Aligned sequences of α-amylases, α-glucosidases, maltases, sucrases, and α- L-fucosidase from M. sexta and other animals. Sus scrofa pancreatic α-amylase (XP_003125929.2), T. castaneum α-amylase (NP_001107848.1), D, melanogaster maltase A1 (NP_476627.3), Apis mellifera α-glucosidase-2 (NP_001035326.1) are aligned with their M. sexta homologs. Green font denotes signal peptides; red font denotes conserved catalytic residues.

Fig. S5. Multiple sequence alignment of myrosinases from M. sexta and other species. Myrosinases of Sinapis alba (P29092.2), Arabidopsis thaliana (P37702), Trifolium repens (P26205), Brassica napus (Q00326), and Brevicoryne brassicae (AAL25999.1) are aligned with their homologs in M. sexta. Green font denotes signal peptides; red font denotes conserved catalytic residues.

Fig. S6. SDS-PAGE and LC-MS/MS analysis of digestive fluid from feeding larvae of M. sexta. (A) Coomassie staining. Proteins (3 μg) in midgut juice from day 1, 5th instar larvae were treated with SDS-sample buffer, separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, and stained with Coomassie blue. Positions and sizes of the Mr makers are indicated on the left. (B) Correlation of mRNA and protein levels. Values of log2(TPM+1) and log2(LFQ+1), representing relative mRNA and protein levels, respectively, are plotted and subjected to a linear regression analysis. The equation and correlation coefficient (r2) are shown.