Abstract

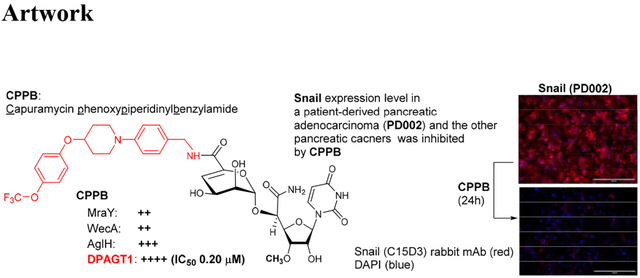

Capuramycin displays narrow spectrum of antibacterial activity by targeting bacterial translocase I (MraY). In our program of development of new N-acetylglucosaminephosphotransferase1 (DPAGT1) inhibitor, we have identified that a capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide analogue (CPPB) inhibits DPAGT1 enzyme with an IC50 value of 200 nM. Despite a strong DPAGT1 inhibitory activity, CPPB does not show cytotoxicity against normal cells and a series of cancer cell lines. However, CPPB inhibits migrations of several solid cancers including pancreatic cancers that require high DPAGT1 expression in order for tumor progression. DPAGT1 inhibition by CPPB leads to a reduced expression level of Snail, but does not reduce E-cadherin expression level at the IC50 (DPAGT1) concentration. CPPB displays a strong synergistic effect with paclitaxel against growth-inhibitory action of a patient-derived pancreatic adenocarcinoma, PD002: paclitaxel (IC50 1.25 μM) inhibits growth of PD002 at 0.0024–0.16 μM in combination with 0.10–2.0 μM of CPPB (IC50 35 μM).

Keywords: Capuramycin analogues, DPAGT1 inhibitor, Antimigratory activity, Snail zinc-finger transcription factors, E-Cadherin, Synergistic effect, Computational chemistry

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

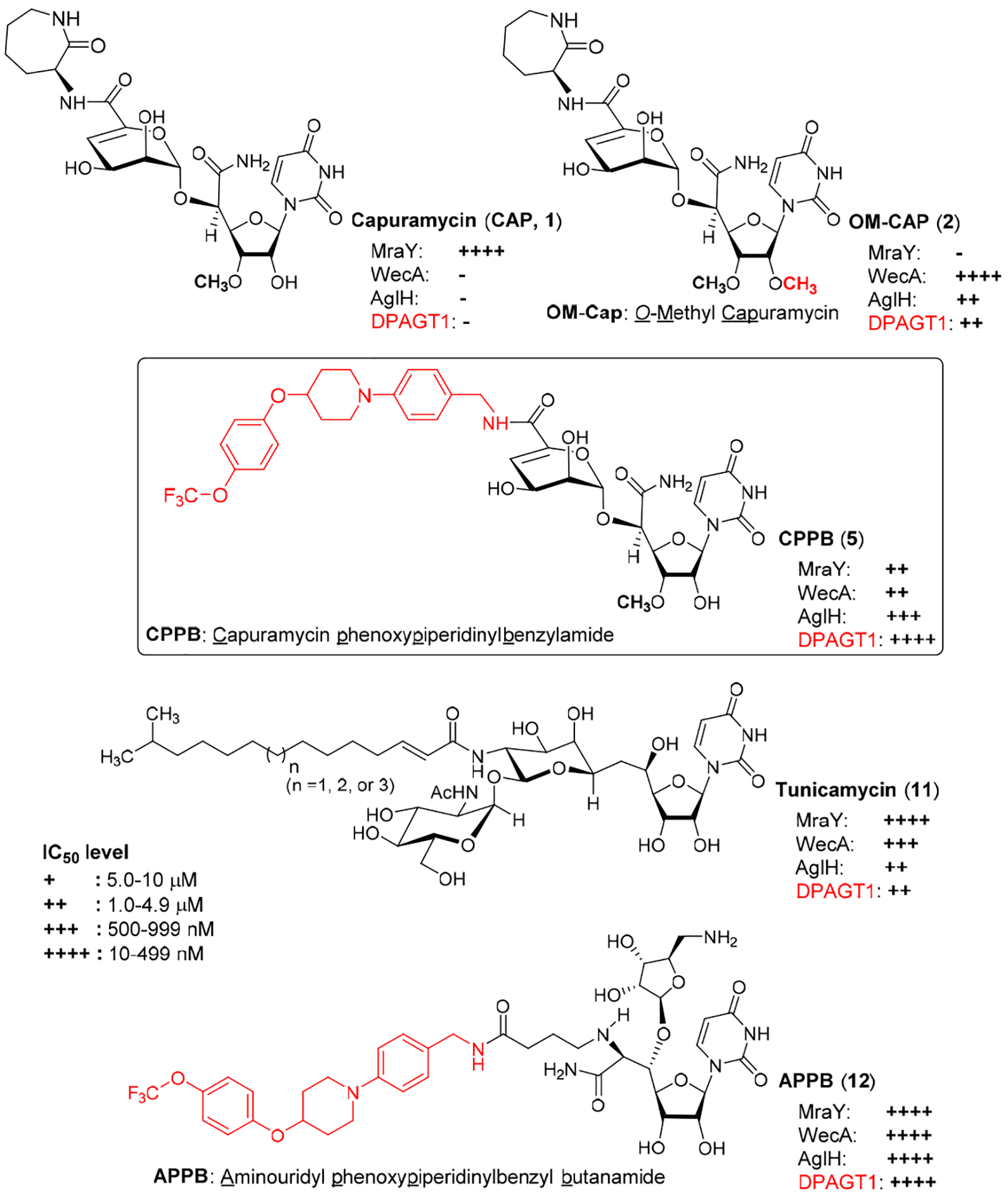

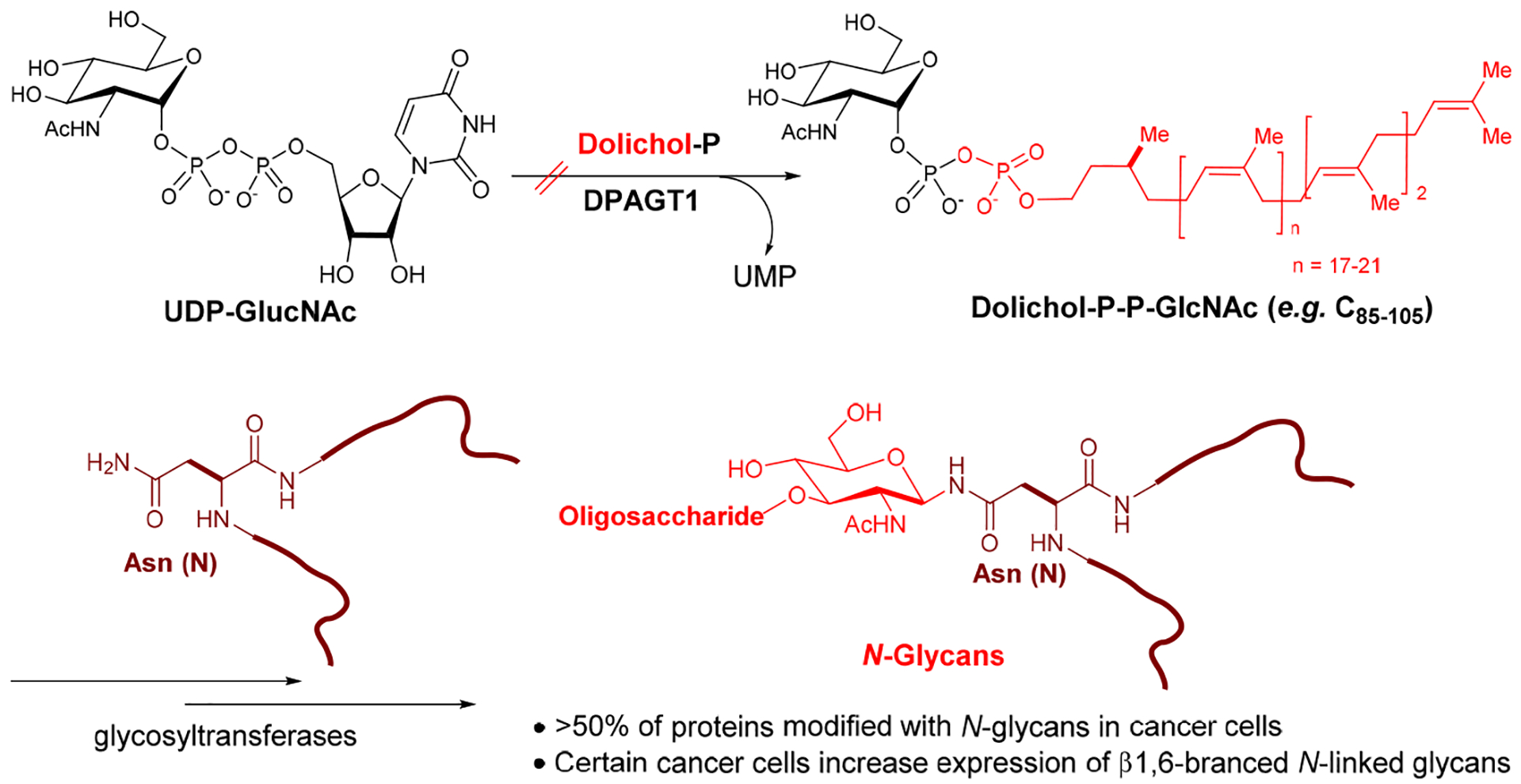

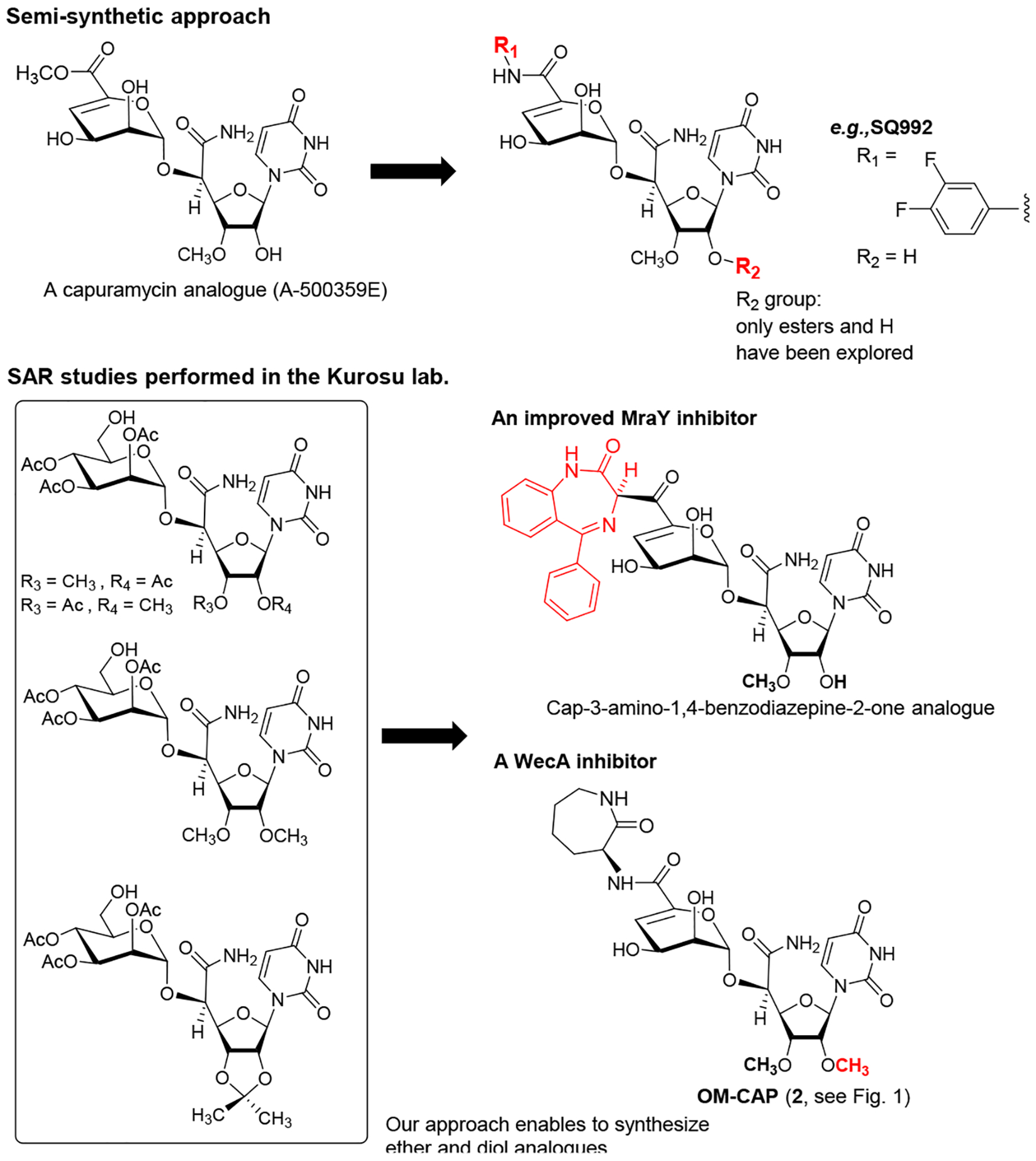

Capuramycin (CAP (1), Figure 1) is a nucleoside antibiotic, which has a narrow-spectrum of activity against Gram-positive bacteria including Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb).1–3 To date, medicinal chemistry efforts on capuramycin have been focused on developing a new TB drug; new capuramycin analogues have been synthesized to improve bacterial phospho-MurNAc-pentapeptide translocase I (MraY and MurX for Mycobacterium spp.) enzyme as well as antimycobacterial activities.1,4,5 Somewhat recently, the anti-Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile) activity of a capuramycin analogue has been reported.6 Capuramycin is a specific inhibitor of MraY with the IC50 value of 0.13 μM,7 however, some other nucleoside antibiotics (e.g., muraymycin A1 and tunicamycins) display activity against MraY, WecA (polyprenyl phosphate-GlcNAc-1-phosphate transferase), and its human homologue, DPAGT1 (N-acetylglucosaminephosphotransferase1)-type phosphotransferases.8–14 MraY is an essential enzyme for growth of the vast majority of bacteria that catalyzes the transformation from UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide (Park’s nucleotide) to prenyl-MurNAc-pentapeptide (lipid I).15 WecA catalyzes the transformation from UDP-GlcNAc to decaprenyl-P-P-GlcNAc, the first membrane-anchored glycophospholipid that is responsible for the biosynthesis of mycolylarabinogalactan in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). WecA is an essential enzyme for the growth of Mtb and some other bacteria. Biochemical studies of WecA enzyme are hampered by lack of selective inhibitor molecules.9 Tunicamycin shows inhibitory activity against these phosphotransferases with the IC50 values of 2.9 μM (MraY/MurX), 0.15 μM (WecA), and 1.5 μM (DPAGT1).9,10 CPZEN-45, an antimycobacterial MraY inhibitor, was reported to exhibit WecA inhibitory activity (IC50 ~0.084 μM).16 We showed that 2’O-methyl capuramycin (OM-CAP (2), formerly UT-01320, Figure 1) does not exhibit MraY/MurX inhibitory activity, but displays a strong WecA inhibitory activity (IC50 0.060 μM).1,9 In vitro cytotoxicity of tunicamycin has been documented in a number of articles.17 Acute toxicity of tunicamycin due to its narrow therapeutic window (LD50: 2.0 mg/kg, LD100: 3.5 mg/kg mice, IP) discourages scientists from developing tunicamycin for new antibacterial, antifungal, or anti-cancer agents.18,19 A large number of scientists believe that cytotoxicity of tunicamycin is attributable to its interaction with DPAGT1, which catalyzes the first and rate limiting step in the dolichol-linked oligosaccharide pathway in N-linked glycoprotein biosynthesis (Figure 2).10,12 In contrast, OM-CAP (2) possesses the same level of DPAGT1 inhibitory activity (IC50 4.5 μM) to tunicamycins (IC50 1.5 μM), but it does not show cytotoxicity against healthy cells (e.g., Vero and HPNE cells) at 50 μM and some cancer cell lines (e.g., L1210, KB, AsPC-1, PANC-1, LoVo, SK-OV-3) at 10 μM. A sharp difference in the cytotoxicity profiles between tunicamycins (11, Figure 1) and OM-CAP (2) raises the question of whether selective inhibition of DPAGT1 enzyme function in certain cells/organs by small molecules does not cause unacceptable level of toxicity against human during chemotherapy. We have recently engineered the structure of muraymycin to yield strong DPAGT1 inhibitors; one of these analogues, APPB (12, Figure 1), showed a promising antiproliferative effect on a series of solid cancer cell lines that required overexpression of the DPAGT1 gene in their growth and cancer progression.11,13,14 The design of APPB was originated from the discovery of DPAGT1 inhibitors of capuramycin analogues. In this article, we report structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies of capuramycin to identify novel DPAGT1 inhibitors, and in vitro anti-invasion and anti-metastasis activity of a new capuramycin analogue DPAGT1 inhibitor, CPPB (capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide analogue, 5) (Figure 1). A unique synergistic effect was observed against a patient-derived pancreatic adenocarcinoma, PD002 in a combination of CPPB with paclitaxel. We demonstrated key interactions of CPPB with DPAGT1 via molecular docking studies. Lastly, we report a semi-synthetic method to deliver enough CPPB for future in vivo studies.

Figure 1.

Development of DPAGT1 Inhibitors of Capuramycin Analogues. Structures of Capuramcyin, O-Methyl capuramycin (OM-Cap), Capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide analogue (CPPB), Aminouridyl phenoxylpiperidinylbenzylbutanamide (APPB, Previously Reported DPAGT1 Inhibitor), and Tunicamycin (Reference Molecule).

Figure 2.

DPAGT1 in N-Glycan Biosynthesis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemistry and Structure activity relationship (SAR).

Sankyo (currently Daiichi-Sankyo) and Sequella have reported several capuramycin (CAP, 1) analogues that have improved MraY enzyme and bacterial growth inhibitory activities.2,3,5,20 Their SAR studies rely on a capuramycin biosynthetic intermediate, A-500359E, which allows delivery of novel amide molecules (R1 group) having an ester (R2) functional group (Figure 3). The capuramycin analogue, SQ992, has an interesting antibacterial characteristic with antimycobacterial activity in vivo.21 We have accomplished a total chemical synthesis of capuramycin and its analogues.22, To date, we have identified an novel analogue possessing improved MraY inhibitory activity, Cap-3-amino-1,4-benzodiazepine-2-one analogue,23 and a selective WecA inhibitor, OM-Cap (2), via our total synthetic approach (Figure 3).1,9 Since our first report on a total synthesis of capuramycin, a few improvements of the synthetic scheme have been made: we introduced acid-cleavable protecting groups for the uridine ureido nitrogen (3-postion in a) and primary alcohol (6”-position in c) (Scheme 1).23 The MDPM and MTPM groups can simultaneously be removed with 30% TFA to form the key synthetic intermediate A for capuramycin. In our on-going SAR of capuramycin, commercially available protecting groups (BOM and chloroacetyl groups) for the ureido nitrogen (3-position) and C6“-alcohol were decided to apply in our SAR tactics. Success of hydrogenolytic cleavage of the BOM group and tolerability of the chloroacetyl group were difficult to predict in capuramycin synthesis. To establish the new protecting group strategy, we first demonstrated the synthesis of iso-capuramycin (I-Cap) (Scheme 2A). Syntheses of all building blocks and the experimental procedures for their synthetic steps in Scheme 2 and 3 are summarized in Supporting Information (SI). Highlights of syntheses of new capuramycin analogues are illustrated in Scheme 2 and 3. The (S)-cyanohydrin 13 was subjected to NIS-AgBF4 promoted α-selective mannosylation with the thioglycoside 14 to yield the α-mannosylated cyanohydrin 15 in 78% yield.22 The cyano group of 15 was hydrated using HgCl2-aldoxime in aq. EtOH, and the BOM and chloroacetyl groups of the generated amide were deprotected stepwisely: dechloroacetylation with thiourea followed by hydrogenation with 10% Pd-C in AcOH-iPrOH-THF provided the C6”-free alcohol 16 in 53% overall yield. Oxidation-elimination reaction of 16 with SO3•pyridine in a solvent system (CH2Cl2/Et3N/DMSO = 10/2/1) provided the α, β unsaturated aldehyde 17 in quantitative yield (determined by 1H NMR analysis). After all volatiles were removed, the aldehyde 17 was oxidized to the corresponding carboxylic acid 18 by using NaClO2 in the presence of NaH2PO4 and 2-methyl-2-butene.24 The resulting carboxylic acid 18 was coupled with (2S)-aminocaprolactam by using a standard peptide-forming reaction condition (HOBt, EDCI, and NMM) to yield the coupling product 19 in 70% overall yield from 16. Saponification of 19 by using Et3N in MeOH provided I-Cap (3) in quantitative yield. Similarly, dimethyl-capuramycin (DM-CAP) was synthesized in 31% overall yield from the cyanohydrin-acetonide 20. CAP (1) and its three analogues, OM-CAP (2), I-CAP (3), and DM-CAP (4) were evaluated in enzyme inhibitory assays against bacterial phosphotransferases, MraY and WecA, and archaeal and human dolichyl-phosphate GlcNAc-1-phosphotransferases, AglH and DPAGT1.7,9,11 CAP is a selective MraY inhibitor that does not display inhibitory activity against WecA, AglH, and DPAGT1 (Table 1). Previously, OM-CAP (2) was identified as a selective WecA inhibitor (IC50 0.060 μM) that does not possess MraY inhibitory activity (IC50 >50 μM (entry 2 in Table 1).9 In this program, it was realized that OM-CAP (2) has inhibitory activity against AglH and DPAGT1 with the IC50 values of 2.5 and 4.5 μM, respectively (entry 2). I-CAP (3) showed enzyme inhibitory activity against MraY, WecA, AglH, and DPAGT1 with the IC50 between 8.5–30 μM concentrations (entry 3). On the contrary, DM-CAP (4) showed only a weak WecA inhibitory activity (IC50 35.0 μM) (entry 4). In recent reports on co-crystal structures of DAPGT1 with tunicamycin (PDB: 5O5E and 6BW6), the fatty acid chain of tunicamycin is occupied in the hydrophobic tunnel (the proposed dolichol-phosphate (Dol-P) binding site).25,26 We speculated that introduction of pharmacologically amenable hydrophobic groups that occupy the proposed Dol-P binding site is essential to exhibit strong DPAGT1 inhibitory activity. In virtual screening of a hydrophobic group (excluding fatty acids) using the structure of DPAGT1 with bound tunicamycin (PDB: 6BW6), an analogue (e.g., (((trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidinyl)benzylamide) of (((trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)phenol group (i.e. 34 in Scheme 3) found in a new anti-TB drug, delamanid,27,28 was suggested to be a reasonable fatty acid surrogate, whose capuramycin derivatives (capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide (CPPB, 5), iso-capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide (I-CPPB, 6), O-methyl capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide (OM-CPPB, 7), demethyl capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide (DM-CPPB, 8), capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamine (CPPA, 9), and iso-capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamine (I-CPPA, 10)) could bind to DPAGT1 with high affinity. However, the docking program used in these studies is not able to distinguish between low- and high-binding molecules: all (((trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)phenyl)methanamino derivatives provided “good” GlideScores of between -12.9~-16.6 (see Table S1 in SI). Therefore, we decided to synthesize all analogues (CPPB, I-CPPB, OM-CPPB, DM-CPPB, CPPA, and I-CPPA) identified in the virtual screening and evaluate their phosphotransferase inhibitory activity.

Figure 3.

General Strategy of SAR of Capuramycin.

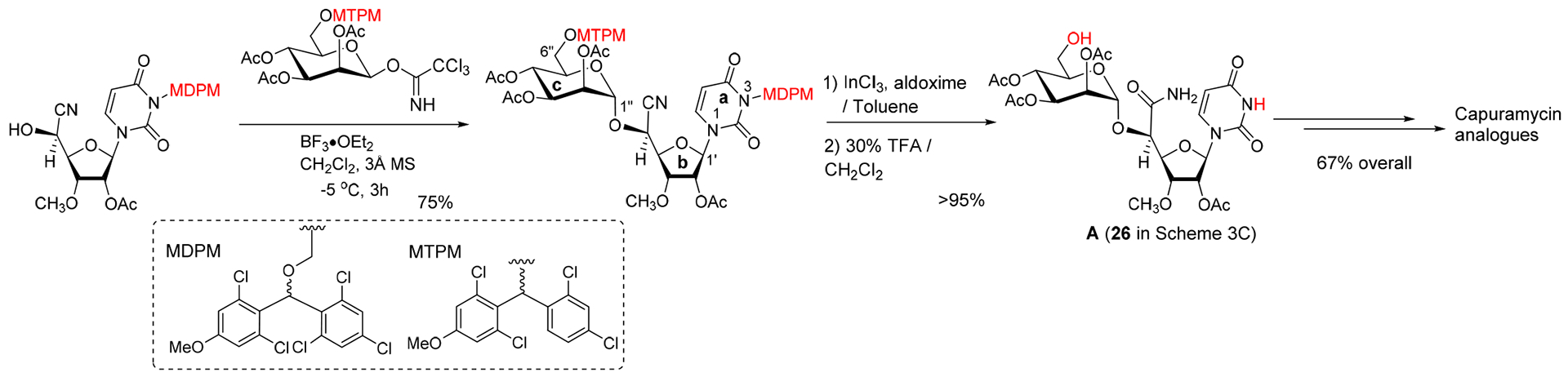

Scheme 1.

An Improved Synthesis of Capuramycin Analogues Developed in The Kurosu Lab.

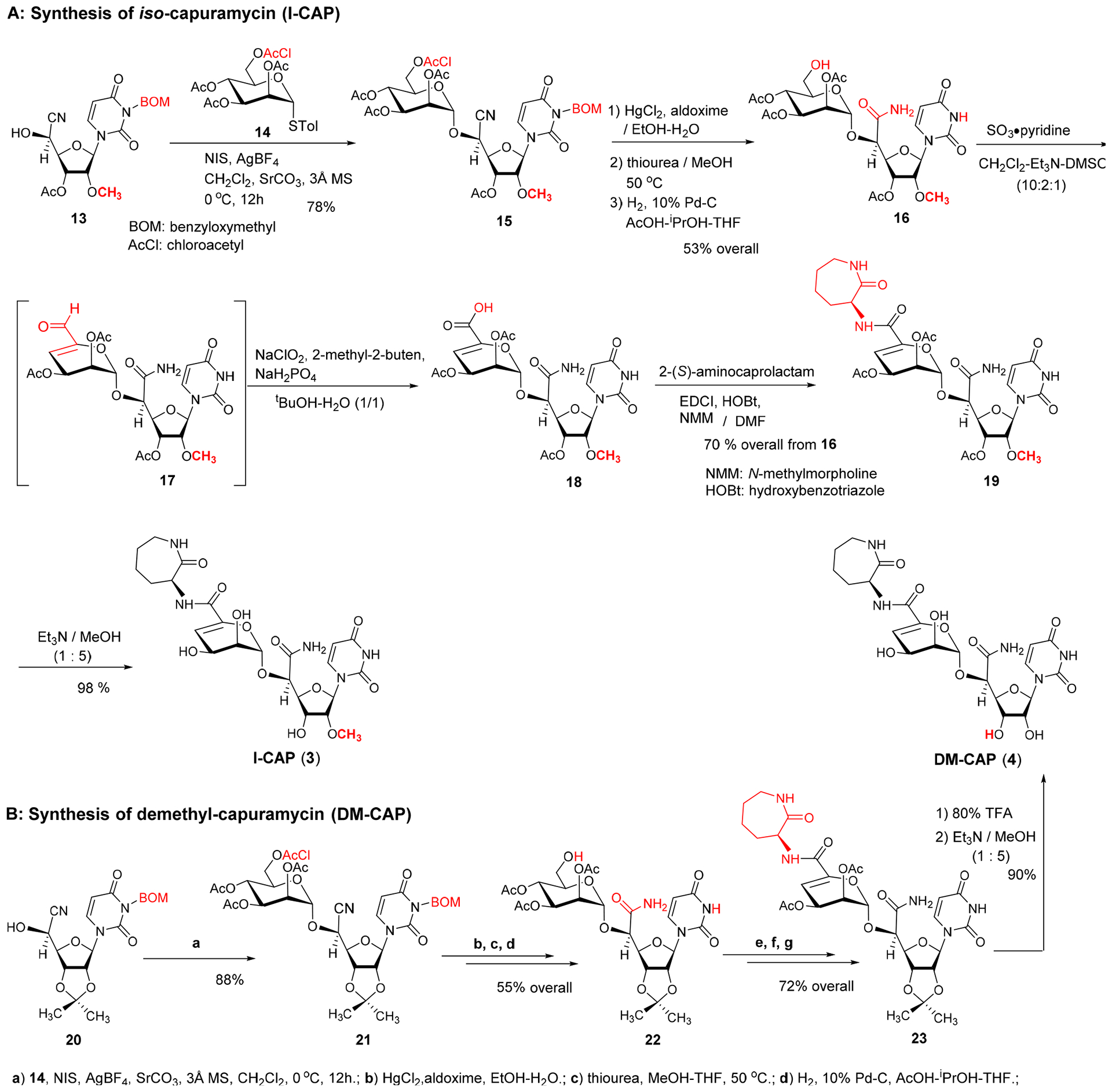

Scheme 2.

Syntheses of iso-Capuramycin (I-CAP, 3) and Demethyl-capuramycin (DM-CAP, 4).

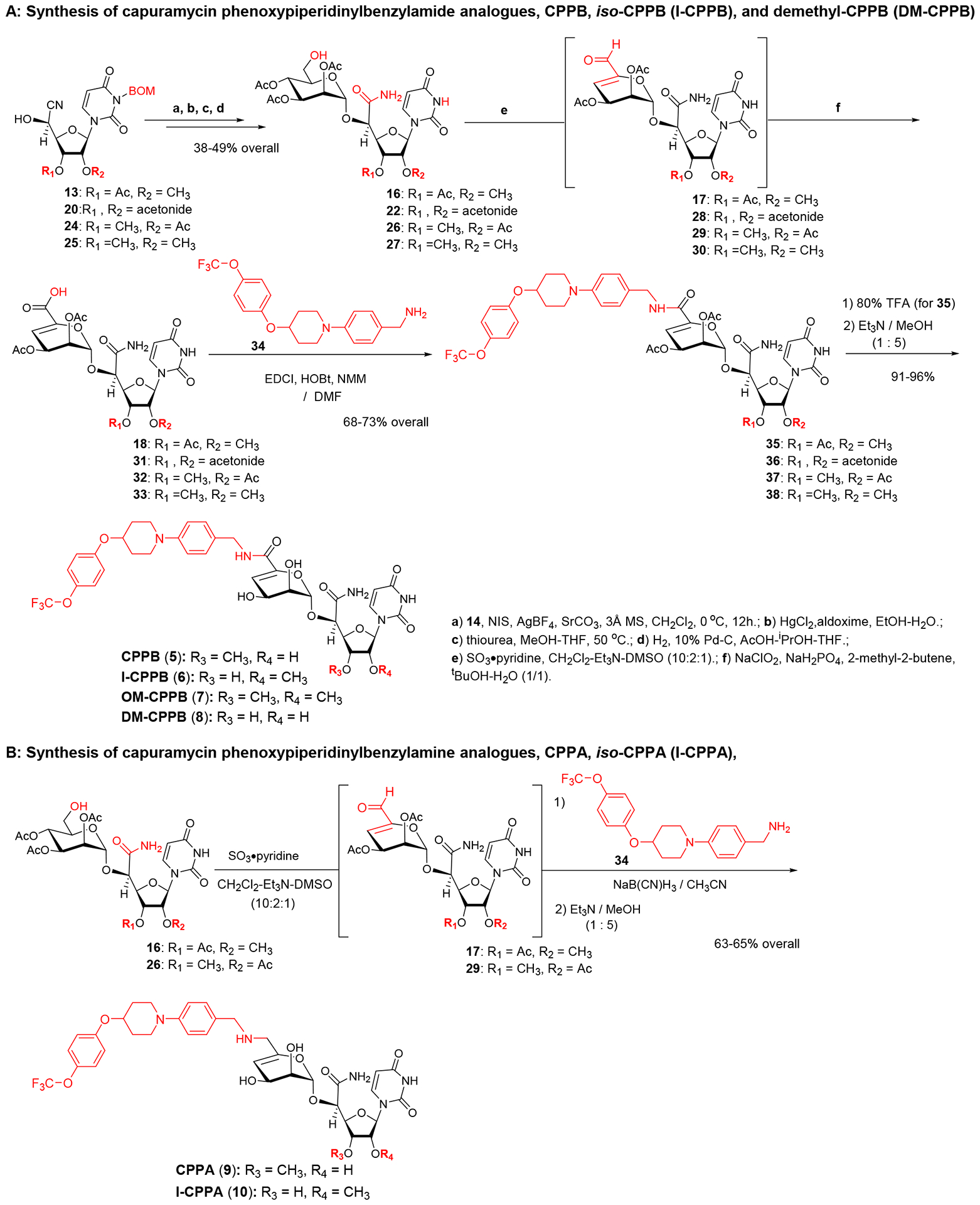

Scheme 3.

Syntheses of Capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamine (CPPA, 9) and iso-Capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamine (I-CPPA, 10).

Table 1.

Phosphotransferase Enzyme Inhibitory Activities of Capuramycin Analogues.a

| Entry | Compound | IC50 (μM)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MraY (Hydrogenivirga sp.) | WecA (E. coli) | AglH (M. jannaschii) | DPAGT1 (Human) | ||

| 1 | Capuramycin (CAP, 1) | 0.13 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 2 | O-Methyl capuramycin (OM-CAP, 2) | >50 | 0.060 | 2.5 | 4.5 |

| 3 | iso-Capuramycin (I-CAP, 3) | 8.5 | 30.0 | 20.0 | 11.5 |

| 4 | Demethyl capuramycin (DM-CAP, 4) | >50 | 35.0 | >50 | >50 |

| 5 | Capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide (CPPB, 5) | 10.3 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| 6 | iso-Capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide (I-CPPB, 6) | >50 | 20.0 | 15.0 | 0.60 |

| 7 | O-Methyl capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide (OM-CPPB, 7) | 5.0 | 10.0 | 30.0 | 20.0 |

| 8 | Demethyl capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide (DM-CPPB, 8) | >50 | 30.0 | >50 | >50 |

| 9 | Capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamine (CPPA, 9) | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 10 | iso-Capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamine (I-CPPA, 10) | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 11 | Tunicamycin (11) | 2.9 | 0.15 | 13.2 | 1.5 |

All assay protocols are summarized in Experimental Section as well as SI.

The carboxylic acid intermediate 32 for CAP (1) was subjected to peptide coupling reaction with (((trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)phenyl)methylamine (34), providing the protected CPPB, 37. Saponification of 37 and purification by reverse HPLC yielded CPPB (5) in 95% overall yield from 37. Similarly, I-CPPB (6), OM-CPPB (7), and DM-CPPB (8) were synthesized from the mannuronic acid derivatives 18, 33, and 31 in 24–34% overall yield (Scheme 3A). Capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamine analogues, CPPA (9) and I-CPPA (10), were synthesized via reductive aminations of the aldehydes 29 and 17 with the amine 34, furnishing the desired products in 63–65% overall yield from 26 and 16 after saponification. MraY, WecA, AglH, and DPAGT1 enzyme inhibitory activity assays for the six (((trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)phenyl)methylamine analogues revealed that CPPB (5) and I-CPPB (6) are high nM range DPAGT1 inhibitors (entries 5 and 6 in Table 1), however, the O-methylation and demethylation analogues (OM-CPPB (7) and DM-CPPB (8)) turned out to be very low- or no-DPAGT1 inhibitor (entries 7 and 8). The secondary amine analogues, CPPA (9) and I-CPPA (10), did not inhibit all phosphotransferases tested in Table 1 at 50 μM concentration (entries 9 and 10). CPPB was determined to be three times stronger DAPGT1 inhibitor (IC50 0.20 μM) than I-CPPB (entry 5 vs. 6). I-CPPB did not display MraY inhibitory activity, but showed a very weak WecA and AglH enzyme inhibitory activity (entry 6). Interestingly, difference in these phosphotransferase inhibitory profiles between CPPB and I-CPPB correlate with their antimycobacterial activity: CPPB possessing MraY/WecA inhibitory activity killed Myocobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, Mycobacterium avium 2285, Mycobacterium smegmatis (ATCC607) with the MIC values 6.25–12.5 μg/mL. In contrast, I-CPPB, which does not have MraY inhibitory activity, did not show growth inhibitory activity against these Mycobacterium spp. at 50 μg/mL.

Cytotoxicity of new capuramycin analogues, CPPB (5) and I-CPPB (6).

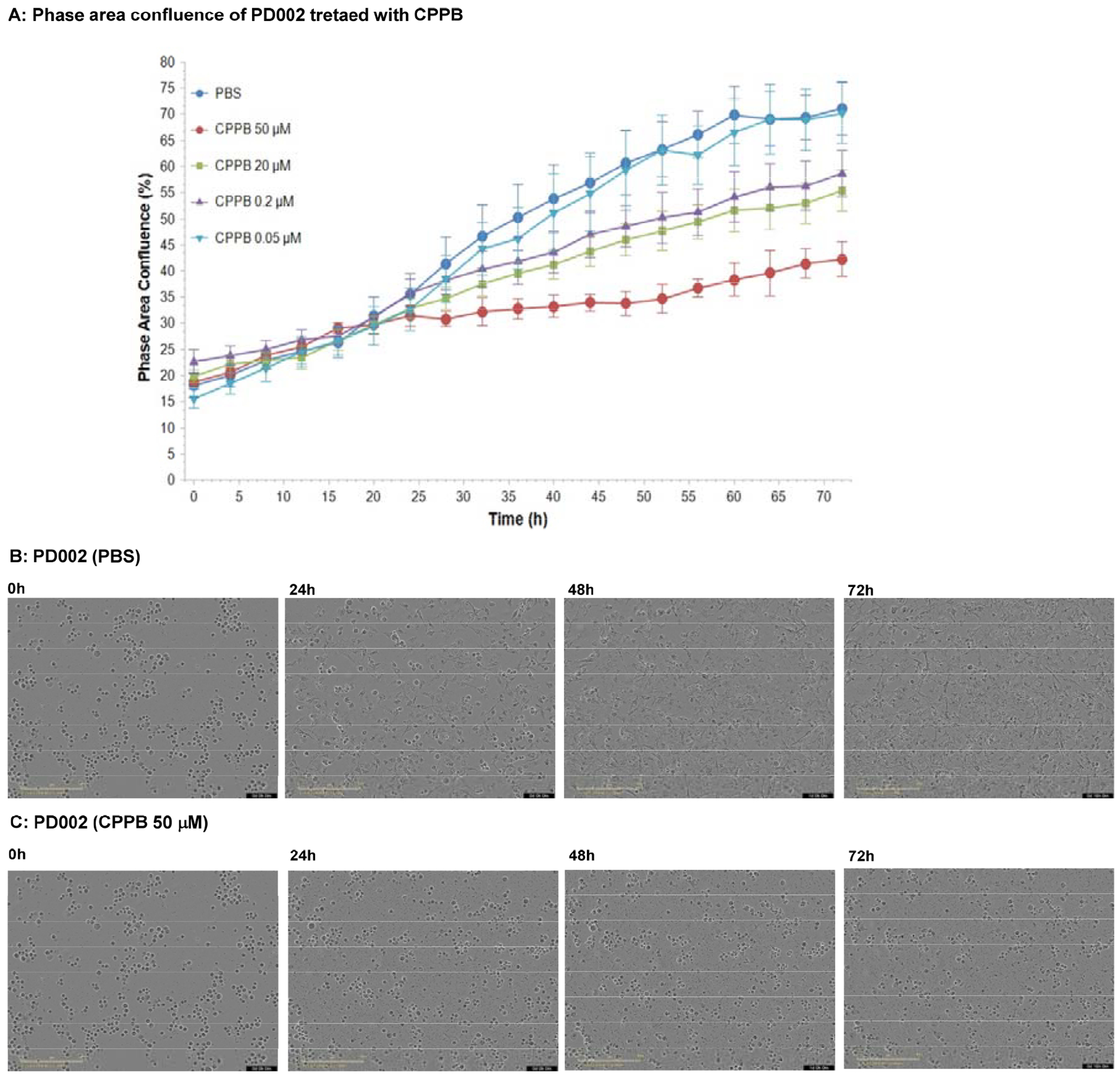

In the capuramycin analogue series, the degree of MraY inhibitory activity correlates with their antimycobaterial activity.7–9,13 Antimycobacterial capuramycin analogues display low in vitro cytotoxicity against mammalian cells, and have been recognized as safe drug leads that have acceptable tolerability in animal models.2,3 The toxicity of tunicamycin (11, Figure 1) has been studied extensively in vitro: tunicamycin inhibits growth in many cancer cell lines without selectivity, and has a narrow therapeutic window demonstrated in in vivo studies using mice.18,29 The toxicity of tunicamycin is believed to be attributable to its ability to inhibit DPAGT1 enzyme function.10,30 However, in our studies, tunicamycin’s toxicity could not be explained solely by its inhibition of DPAGT1. Our DPAGT1 inhibitor, APPB (12, Figure 1) inhibits DPAGT1 with greater than 30-times the inhibitory activity of tunicamycin, and inhibits growth of selected solid cancer cell lines at low μM concentrations with selective cytotoxicity (IC50 normal cells / cancer cells) of >35.10 The LD50 value of APPB is >20 mg/kg (mouse), whereas it is 2.0 mg/kg (mouse) for tunicamycin.10,18 Capuramycin-based DPAGT1 inhibitors, CPPB (5) and I-CPPB (6), identified in this program inhibited DPAGT1 enzyme with the IC50 values of 0.2 and 0.6 μM, respectively. Unlike the MraY-antimycobacterial activity relationship observed for CAP analogues, the DPAGT1 inhibitors, CPPB and I-CPPB, did not show antiproliferative activity against L1210 (a leukemia cell), HPNE (a normal pancreatic ductal cell), and Vero (a normal kidney cell) at 50 μM. They showed various levels of growth inhibitory activity against several solid cancer cell lines such as KB (HeLa, a cervix carcinoma), SiHa (a cervical squamous cell carcinoma), HCT-116 (a colorectal adenocarcinoma), DLP-1 (a colorectal adenocarcinoma), Capan-1 (a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma), PANC-1 (a pancreatic ductal carcinoma), AsPC-1 (a pancreatic adenocarcinoma), PD002 (a patient-derived pancreatic adenocarcinoma) in MTT assays (IC50 15–45 μM, Table 2). A lower DPAGT1 inhibitor, tunicamycin (11), showed growth inhibition of all cell lines in Table 2 with the IC50 values of 0.78–7.5 μM concentrations (entry 5 in Table 2). Cellular behavior and morphological changes of a patient-derived metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, PD002 treated with CPPB were monitored over time via IncuCyte® live cell analysis imaging system (Figure 4A). Interestingly, 10–13% of phase area confluent of PD002 culture (time 0h) remained the same after 72h for the CPPB-treated cells (50 μM), whereas, ca. 70% of confluence was reached for the control PD002 culture (PBS) (Figure 4B vs.4C). Although morphological changes were subtle over time (0–72h), cell viability assessed by the MTT reduction assay revealed that PD002 cells treated with CPPB (50 μM) was significantly decreased (Table 2). Exposure of CPPB (0.2–20 μM) inhibited cell proliferation of PD002: ca. 20% of cell proliferation was inhibited at time 72h. These results may indicate that DPAGT1 inhibitors may have cytostatic effect again certain cancerous tumors that require DPAGT1 overexpression for their growth.

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity of Capuramycin, Capuramycin Analogues, and Tunicamycin.

| Entry | Compound | IC50 (μM)a | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1210 | KB | SiHa | HCT-116 | DLD-1 | Capan-1 | PANC-1 | AsPC-1 | PD002 | HPNE | Vero | ||

| 1 | CAP (1) | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 2 | OM-CAP (2) | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| 3 | CPPB (5) | >50 | 35.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 25.0 | 30.0 | 35.0 | 25.0 | 35.0 | >50 | >50 |

| 4 | I-CPPB (6) | >50 | 35.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 35.0 | 40.0 | 45.0 | 30.0 | 50.0 | >50 | >50 |

| 5 | Tunicamycin (11) | 1.70 | 2.50 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 0.45 | 1.50 | 7.5 | 0.78 |

CAP: Capuramycin.; OM-CAP: O-Methyl capuramycin.; CPPB: Capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide.; I-CCB: iso-Capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide.; L1210 (ATCC® CCL-219™): mouse lymphocytic leukemia.; KB (ATCC® CCL-17™): HeLa, human cervical carcinoma.; SiHa (ATCC® HTB-35™): human cervical squamous cell carcinoma.; HCT-116 (ATCC® CCL-247™): colorectal adenocarcinoma.; DLD-1 (ATCC® CCL221™): colorectal adenocarcinoma.; Capan-1 (ATCC® HTB-79™): pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.; PANC-1 (ATCC® CRL-1469™): pancreatic ductal carcinoma.; AsPC-1 (ATCC® CRL-1682™): pancreatic adenocarcinoma.; PD002: a pancreatic adenocarcinoma staged at T3N1M0 from a 55 years old Caucasian male in 2011 (provided by Dr. Glazer (University of Tennessee Health Science Center).; hTERT-HPNE (ATCC® CRL-4023™): normal pancreatic ductal cell.; Vero (ATCC® CCL-81™): normal Cercopithecus aethiops kidney cell.

IC50 values were determined via MTT assay.

Figure 4.

Kinetic Proliferation Assays for PD002 Treated with CPPB Monitored by IncuCyte® Live Cell Analysis.a

aImages were obtained every 4h using an IncuCyte Live-Cell Imaging System (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI). After 72h, cell proliferation was quantified using the metric phase object confluence (POC), the area of the field of view that is covered by cells (phase area confluence %) is calculated by the integrated software.

Cell migratory inhibition by CPPB (5).

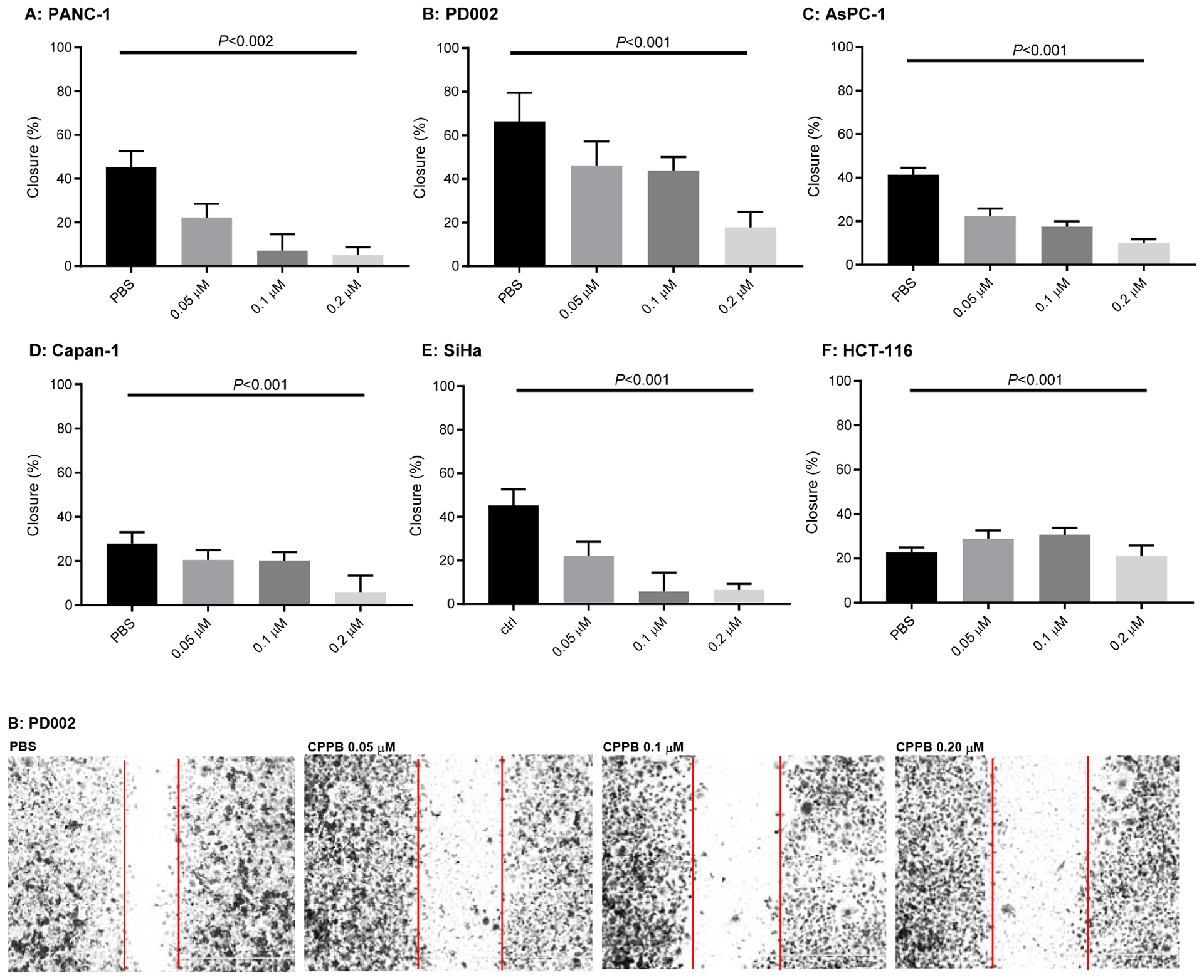

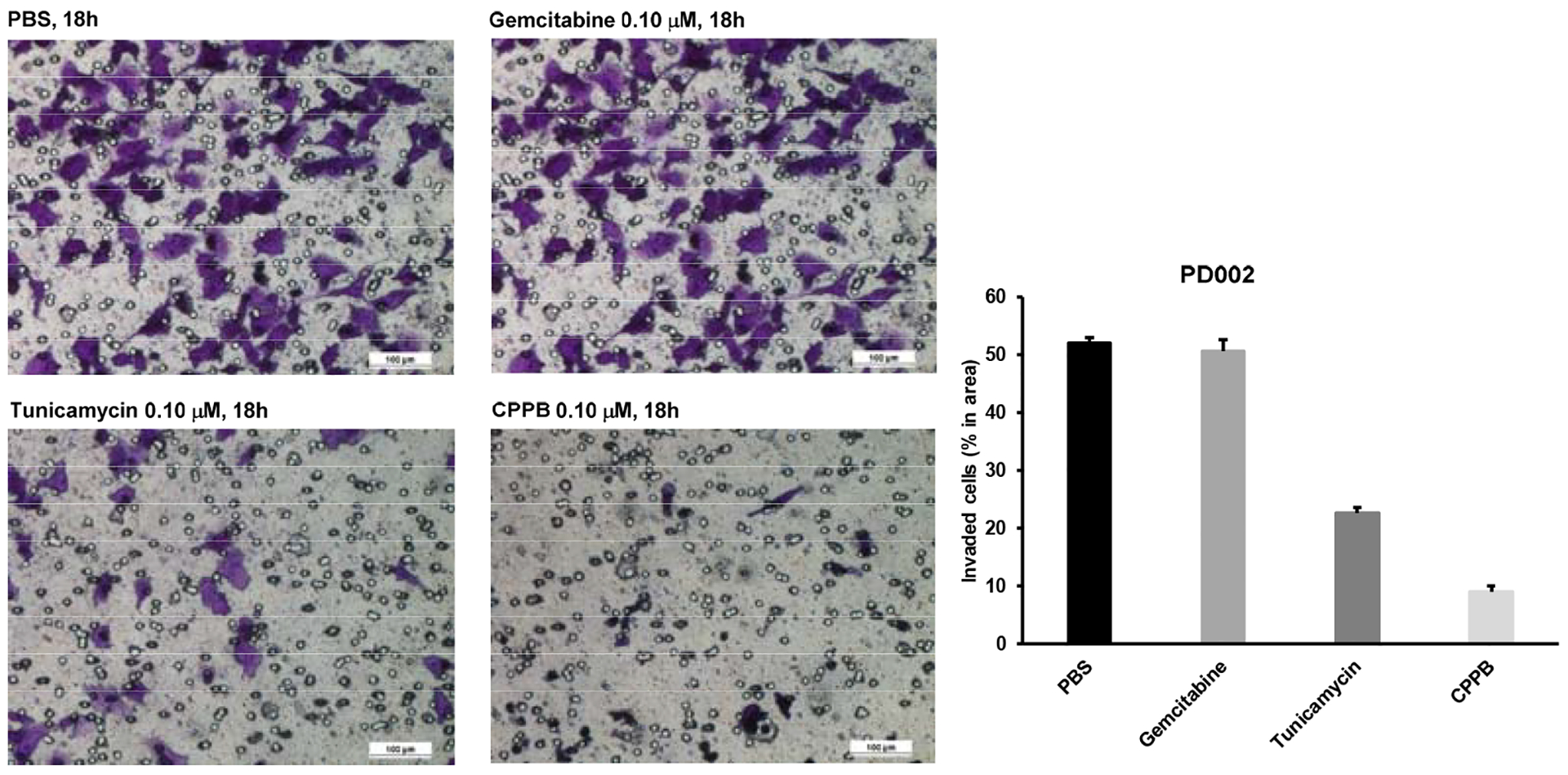

DPAGT1 catalyzes the first step in N-glycan biosynthesis of mammalian cells (Figure 2). Aberrant N-glycosylation is common in many solid cancers and important for the epithelial to mesenchymal transition program (EMT, a mechanism of metastases).10 We found high levels of DPAGT1 protein expression in a series of pancreatic cancers (e.g., PANC-1, Capan-1, and AsPC-1). Dysregulation of DPAGT1 enzyme leads to disturbances in cell-cell adhesions and may increase epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT): these processes increase migratory and invasive capabilities of malignant neoplasms that are the initiation of metastasis in cancer progression, especially pancreatic cancer.31,32 Interestingly, there is significant crosstalk between DPAGT1 and the Wnt/β-catenin and Snail pathway where DPAGT1 overexpression leads to 1) accumulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm and then translocation into the nucleus, and 2) reduction of the Snail expression levels, preventing epithelial-mesenchymal transition by suppressing the E-cadherin expression (a cell-cell adhesion glycoprotein).10,31,32 As such, aberrations in these pathways occur in numerous cancers, thus, discovery of small molecules directed towards inhibition of the Wnt and Snail pathways represents an important area of anticancer therapeutics.33–35 In order to obtain insights into anti-metastatic ability of DPAGT1 inhibitors, we explored the degree of cell migration in several commercially available cell lines (Capan-1, PANC-1, and AsPC-1), a patient-derived pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell line (PD002), a cervical carcinoma (SiHa), and a colorectal adenocarcinoma (HCT-116) to determine the effects on cellular motility. After 24h of three treatment doses (0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 μM) with CPPB (5), inhibition of migration (closing the gap) was measured in a scratch assay (wound healing assay).36 Only the images for PD002 are shown in Figure 5 and all other images obtained through these experiments are illustrated in Supporting Information (SI). The pancreatic cancer cell lines treated with CPPB migrated far less than the PBS treated (control) cells (Figure 5A–D). In these assays, the wound-healing rate of the untreated PD002 cells was 63% in 24h. In sharp contrast, CPPB treated cells inhibited the wound-healing effectively at its IC50 level against DPAGT1 (0.2 μM): the wound-healing rate was approximately 20% (Figure 5B). We thoroughly evaluated migration inhibition ability of CPPB compared to gemcitabine, one of the main chemotherapy drugs used to treat pancreatic cancer, and tunicamycin using PD002 cells. Gemcitabine shows a wound-healing rate of 43% at 0.2 μM, and tunicamycin shows 35% at 0.2 μM (SI). Thus, it was concluded that CPPB is more effective in inhibiting cancer cell migration than gemcitabine and tunicamycin. These trends were further confirmed by an endpoint migration assays via Boyden chambers for PD002.37,38 In these assays, the cell migrations of PD002 treated with CPPB (0.1 μM) were inhibited on a higher level compared to those with tunicamycin and gemcitabine at the same concentration (0.1 μM) (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Analyses of Migration inhibition of Pancreatic Cancers (PANC-1, PD002, AsPC-1, and Capan-1), a Cervical carcinoma (SiHa), a Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (HCT-116) by Treatment with CPPB in Would Healing (Scratch) Assays.a

aAll images were acquired at 24h and these are summarized in SI (only the data for PD002 shown). P values were obtained from T score calculator.

Figure 6.

Cell Migration Inhibition of PD002 by Gemcitabine, Tunicamycin, and CPPB via Transwell Chamber.a

aThe cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 0.5h and stained with 0.05% crystal violet (300 μL/well), after 0.5h, the images were captured via 10X magnification microscopy.

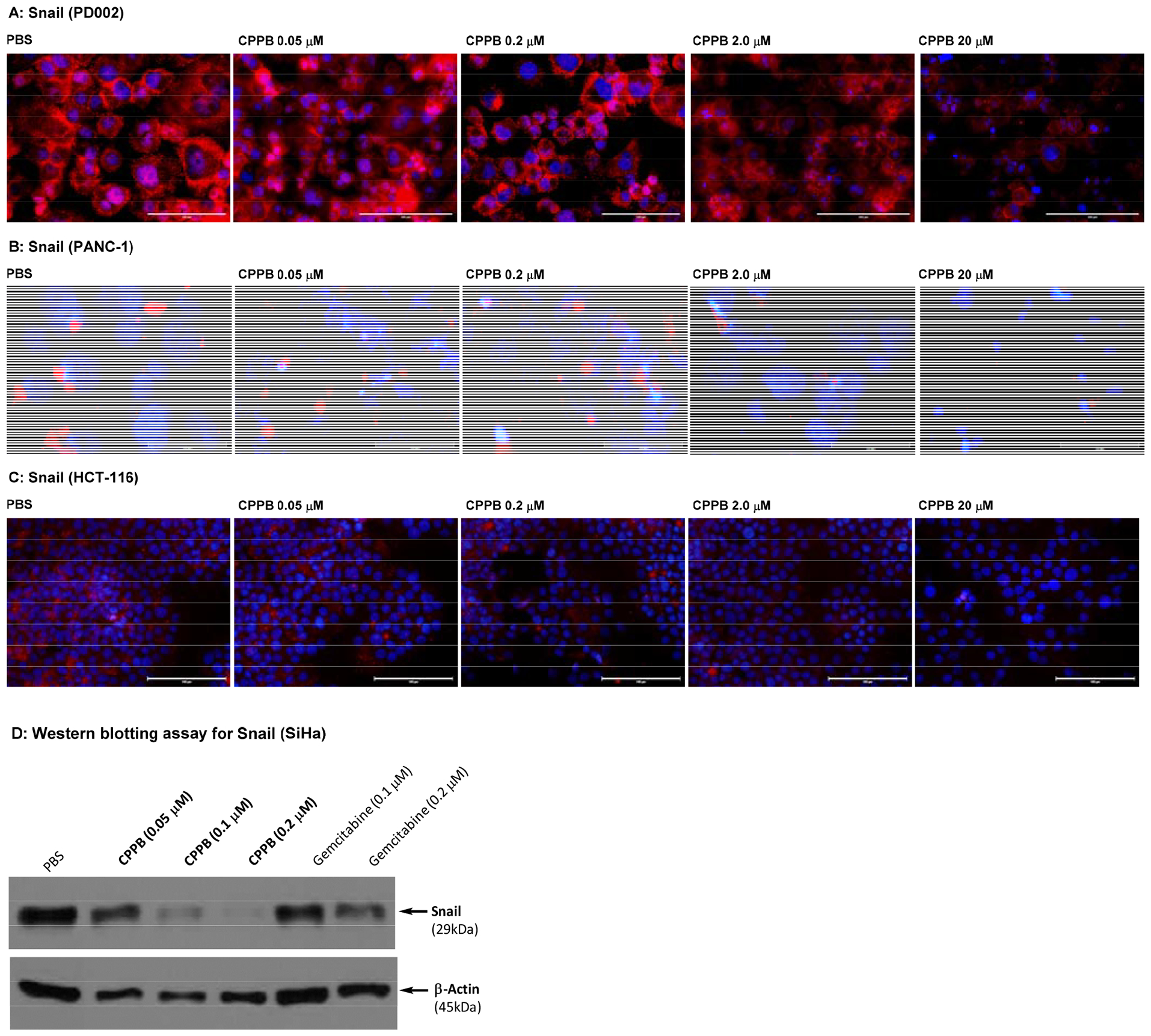

Inhibition of a zinc-finger transcription factor, Snail1 (Snail) in the selected cancer cell lines by CPPB.

Snail protein is one of the most important transcription factor that induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), which converts epithelial cells into migratory mesenchymal cells that are more efficient at metastasizing.39 EMT induced by overexpression of Snail produces cancer stem-like properties in a number of solid organ cancers. Aberrant expression of Snail leads to loss of expression of E-cadherin.40 Thus, suppression of Snail expression or inhibition of Snail functions represents a potent targeted therapeutic strategy for many cancers.41,42

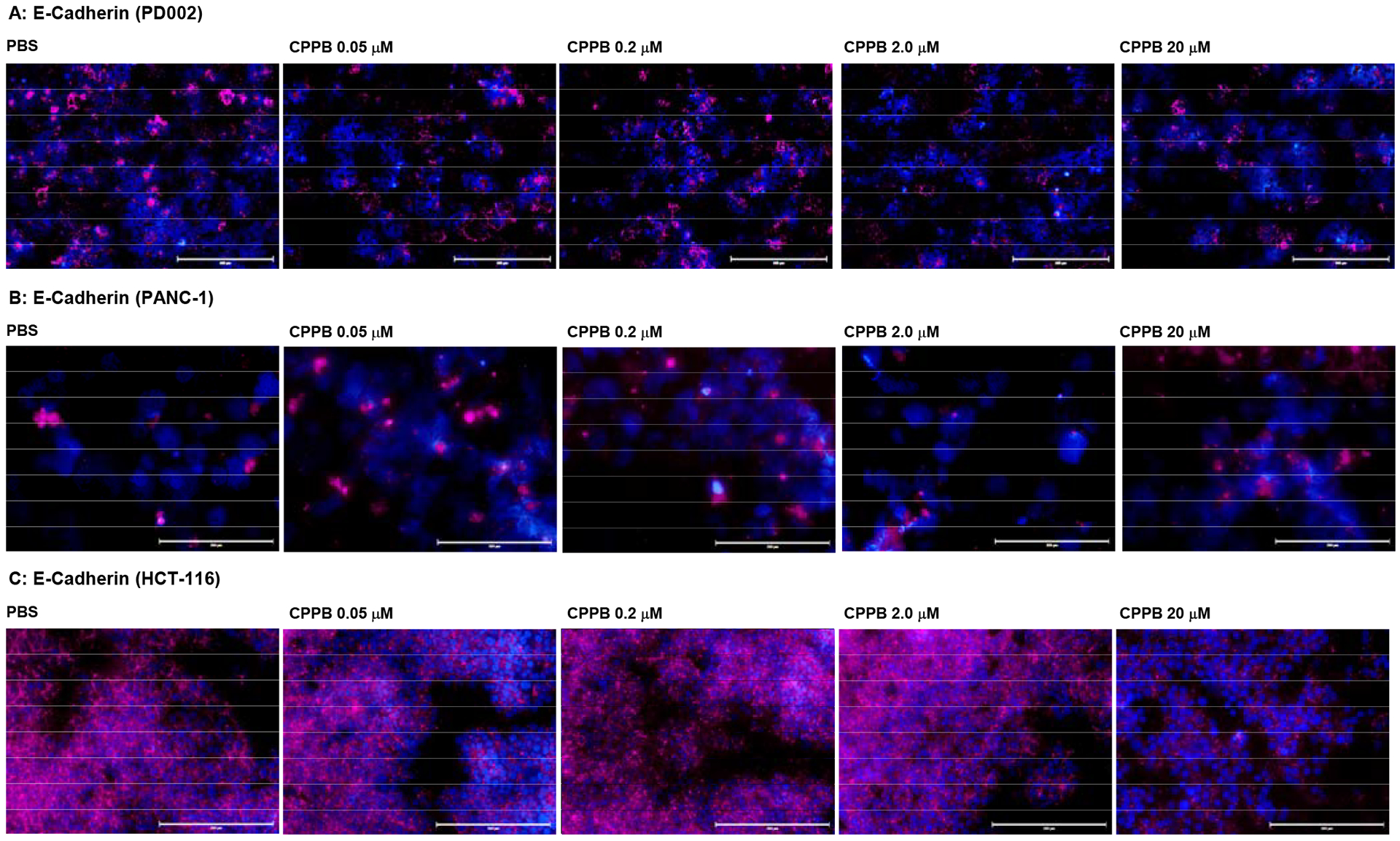

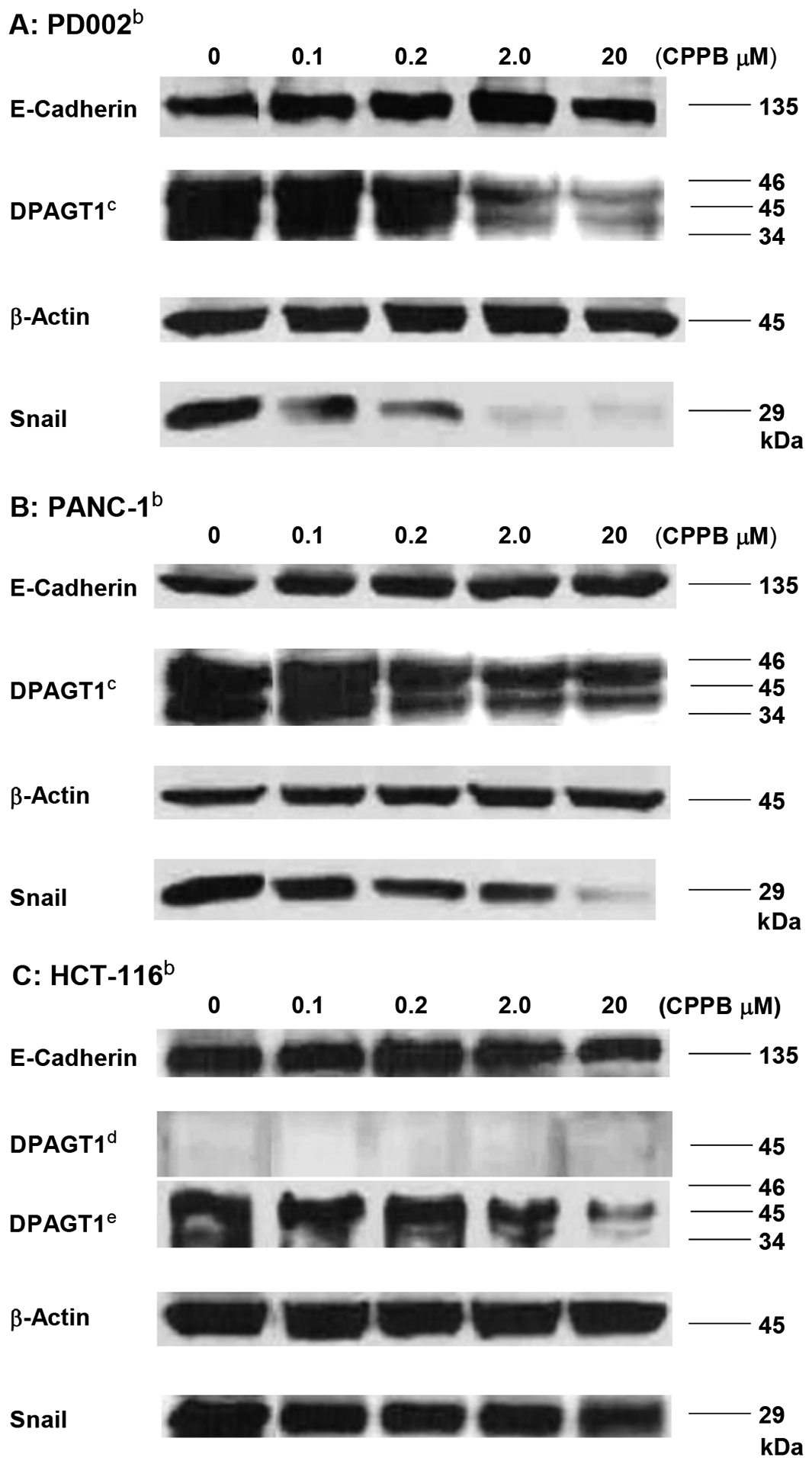

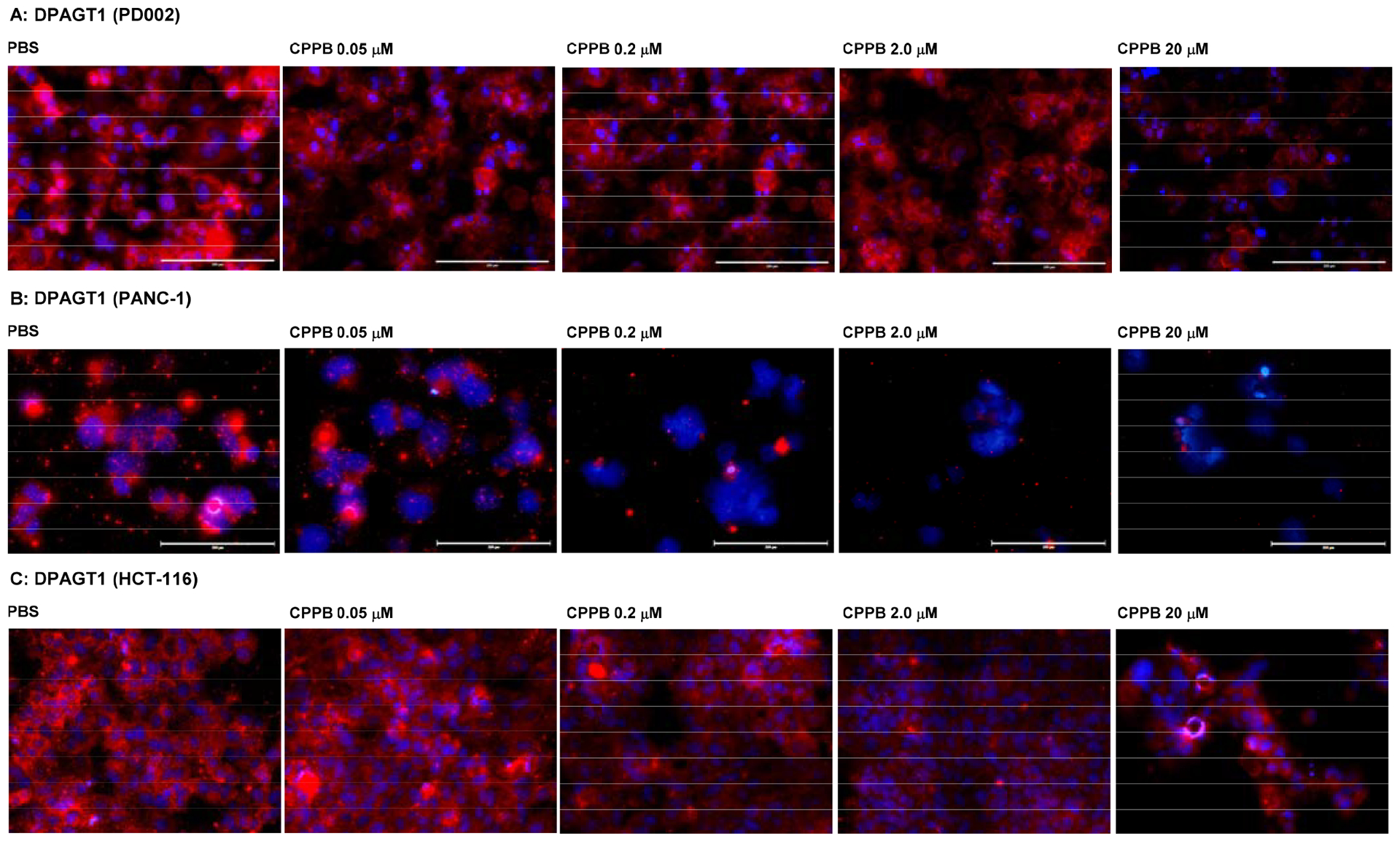

Immunofluorescence assays using an anti-Snail antibody revealed that the fluorescence intensity of Snail was strong in a series of pancreatic cancer cells (PANC-1, AsPC-1, Capan-1, and PD002), and the expression of Snail was decreased by the treatment with CPPB in a concentration dependent manner. Among pancreatic cancer cell lines, only the data for PD002 and PANC-1 are shown in Figure 7A and 7B (see SI for AsPC-1 and Capan-1). The Snail expression level of a non-metastatic pancreatic cancer, PANC-1, was much lower than metastatic pancreatic cancers (e.g., PD002 and Capan-1). A few other types of cancer cells such as a colorectal cancer (HCT-116) and a cervical cancer (SiHa) were examined by similarly designed immunofluorescence assays or Western blot assays (Figures 7C and 7D). The Snail expression in SiHa was inhibited by treatment of CPPB in a concentration dependent manner; at the IC50 concentration (0.2 μM against DPAGT1), CPPB effectively inhibited the Snail expression (Figure 7D). In contrast, the Snail expression level in HCT-116 was not noticeably changed by the treatment of CPPB between 0.05 and 2.0 μM concentrations. Interestingly, cell migration of HCT-116 was not inhibited by CPPB demonstrated in the wound healing (scratch) assays (Figure 5F). At the concentrations tested in the scratch assays (0.05–2.0 μM), the E-Cadherin expression levels of PD002, PANC-1, and HCT-116 were not changed significantly (Figure 8). To support the above discussion based on the immunefluorescent staining (Figure 7 and 8), the relative expression levels of Snail and E-cadherin in PD002, PANC-1, and HCT-116 treated with CPPB were measured by Western blot analyses (Figure 9). The relative expression levels were obtained by using Image Studio™ Lite quantification software, and these quantified data were summarized in SI (see Figure S5). PD002 and PANC-1 treated with CPPB (0 to 2.0 μM) lead to a dose dependent decrease in Snail. The E-Cadherin expression level of a metastatic pancreatic cancer, PD002 was increased in a CPPB concentration depended manner (0 to 2.0 μM), whereas, a non-metastatic pancreatic cancer, PANC-1 exhibited the same expression level of E-Cadherin at 0–2.0 μM concentrations of CPPB (Figure 9A and 9B). A low DPAGT1 expressed-colon cancer, HCT-116 did not display noticeable difference in the expression levels of Snail and E-Cadherin at 0–2.0 μM CPPB concentrations (Figure 9C).

Figure 7.

Immuno-fluorescent staining: Effect of a DPAGT1 Inhibitor, CPPB, on Snail in Pancreatic Cancer Cells (PD002 and PANC-1) and a Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (HCT-116). Western Blotting Assay for a Cervical Cancer (SiHa).a

aFluorescence microscopy images at 40x. The cells (1 ×105–6) were treated with CPPB (0.05, 0.2, 2.0, and 20 μM) or PBS for 24h. For immunefluorescent studies: the cells were treated with Snail (C15D3) rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology), followed by Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™568 (red). DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), a blue fluorescent DNA dye, was used to mark the nucleus. 40x. For Western blotting assays: The cells were treated with Snail (C15D3) rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology), followed by secondary antibody, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked antibody (Cell Signaling Technology).

Figure 8.

Immunofluorescent Staining: Effect of a DPAGT1 inhibitor, CPPB, on E-Cadherin in Pancreatic cancer cells (PD002 and PANC-1) and a Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (HCT-116).a

aFluorescence microscopy images at 20x. The cells (1 ×105–6) were treated with CPPB (0.05, 0.2, 2.0, and 20 μM) or PBS for 24h. The cells were treated with E-cadherin (4A2) mouse mAb (Cell Signaling Technology), followed by secondary antibody, goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor™ Plus 647 (Invitrogen). DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), a blue fluorescent DNA dye, was used to mark the nucleus. 40x

Figure 9.

Western blot Analyses of DPAGT1, Snail, and E-Cadherin in PD002, PANC-1, and HCT-116 treated with CPPB.a

aThe relative expression level was quantified by using Image Studio™ Lite quantification software (n = 3, p<0.001, see SI).; bAll cell lysates were prepared to be 1.5 mg total protein/mL by 15,200 xg, 30min at 4 °C unless indicated. CAt least three isoforms of DPAGT1 were detected.; dDPAGT1 was not detectable at 30 μL (1.5 mg total protein /mL).; eThe cell lysate was prepared by ultracentrifugation (130,000 xg for 1h at 4 °C). 30 μL of the lysate was analyzed.

Inhibition of DPAGT1 by CPPB.

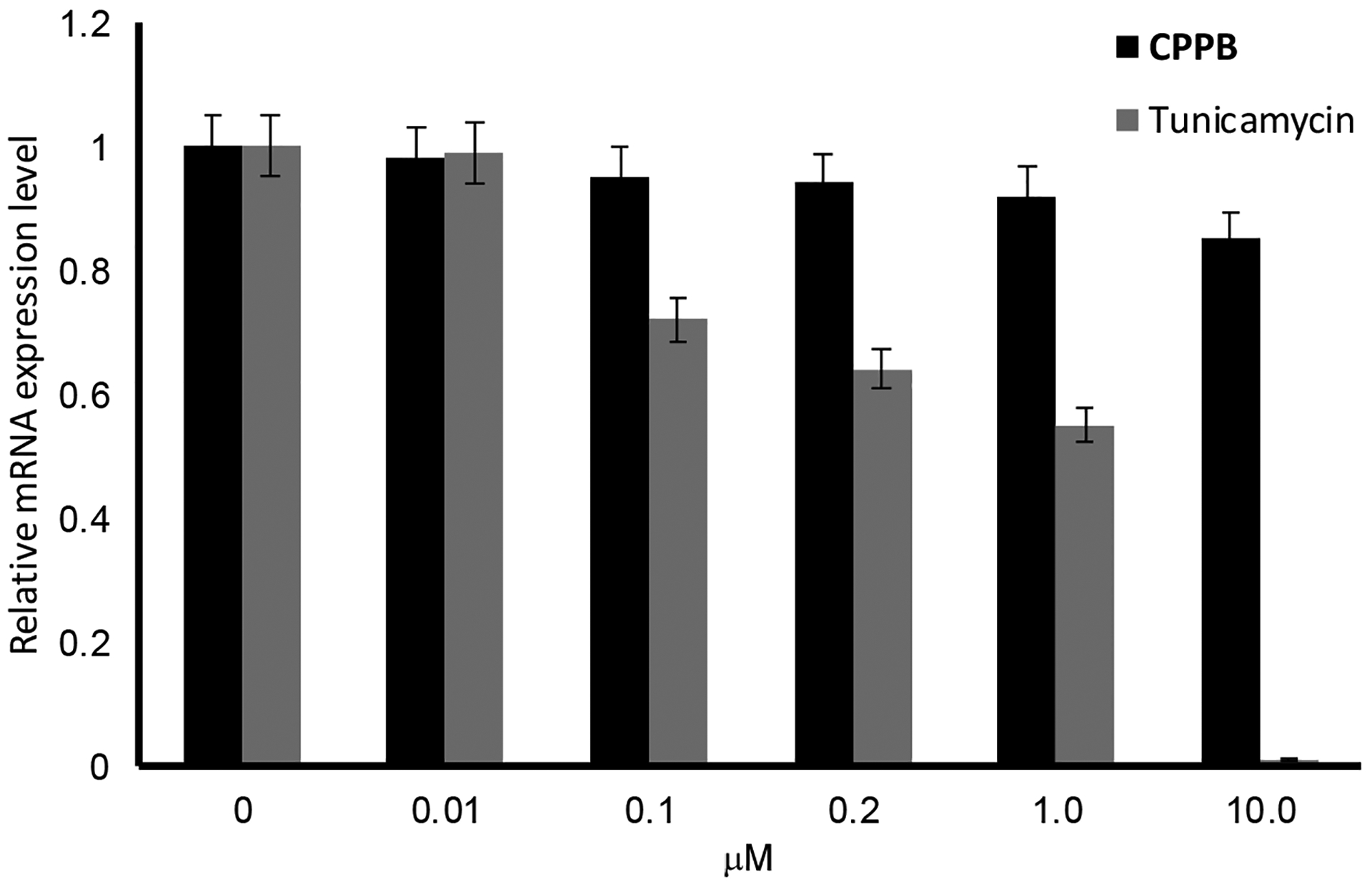

CPPB decreased the DPAGT1 expression level in all pancreatic cancer cell lines examined in Figure 5: the DPAGT1 expression was apparently inhibited by the IC50 concentration of CPPB (0.2 μM) (only the data for PD002 and PANC-1 shown Figure 10 and see Figure S4 in SI) for AsPC-1 and Capan-1). An important observation is that the DPAGT1 expression of the pancreatic cancer cell lines could not completely be inhibited at a high concentration of CPPB (2–20 μM) (Figures 9 and 10). In MTT assays, we realized that all pancreatic cancers tested remained viable at 20 μM concentration of CPPB (Table 2). We confirmed that the DPAGT1 expression level in a colorectal adenocarcinoma, HCT-116 is significantly lower than that in the pancreatic cancer cell lines (PD002 and PANC-1); DPAGT1 was not detectable in Western blot assays for the lysate obtained by a standard protocol (50 μg/30 μL of total protein sample). A 10 times concentrated HCT-116 cell lysate (prepared by ultracentrifugation, 130,000xg for 1h) enabled us to detect DPAGT1 in Western blotting. By treatment of HCT-116 with CPPB at 0.1–20 μM concentration, the DPAGT1 expression levels of HCT-116 remained higher fluorescence intensity in immunefluorescent assay (Figure 10C) and 20–90% in Western blot assays (Figure 9C). These data imply that the inhibitory effect of CPPB on cell migration varies depending on degree of inhibition of the DPAGT1 expression: immunefluorescent assays at 0.2–2.0 μM concentrations of CPPB, the degree of DPAGT1 expression was decreased by the following order: PANC-1 > PD002 >> HCT-116. Migration inhibition observed in the scratched assays (Figure 5) is well-correlated with the degree of the DPAGT1 expression inhibition. Although CPPB decreased the protein expression of DPAGT1 without significantly decreasing its gene (DPAGT1) expression, tunicamycin decreased both the gene expression of DPAGT1 and DPAGT1 protein expression (Figure 11). These down-regulation in DPAGT1 gene expression by tunicamycin may be attributable to its high cytotoxicity against mammalian cells without selectivity.

Figure 10.

Immunofluorescent staining: The DPAGT1 Expression Level in the Selected Cancer Cell Lines (PD002 and PANC-1) and a Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (HCT-116) Treated with CPPB.a

aFluorescence microscopy images at 20x. The cells (1 ×105–6) were treated with CPPB (0.05, 0.2, 2.0, and 20 μM) or PBS for 72h. The cells were treated with DPAGT1 polyclonal antibody (Invitrogen, PA5–72704), followed by secondary antibody, Donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor™ 555 (red) (Invitrogen). DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), a blue fluorescent DNA dye, was used to mark the nucleus.

Figure 11.

RT-qPCR Analyses of DPAGT1 Expression Level in PD002 Treated with CPPB.a

a~5 ×106 of PD002 was applied. Incubation time: 24h at 37 °C. At 10 μM, tunicamycin killed PD002 in 100%.

Synergistic effect of CPPB with paclitaxel.

The FOLFIRINOX (a combination of folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) and nab-paclitaxel (albumin-bound paclitaxel)-gemcitabine regimens have been adopted into clinical practice for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancers.43 Median progression-free survival was reported in one study of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer to be 6.4 months in the FOLFIRINOX group and 3.3 months in the gemcitabine group.43,44 Over the past years, the clinical data have not supported that FOLFIRINOX is associated with any better (or worse) survival rates compared to the nab-paclitaxel-gemcitabine regimen as there have been no head-to-head trials.45 However, the inclusion of paclitaxel and its derivatives in combination regimens remains an important therapeutic strategy in pancreatic cancer chemotherapy since nab-paclitaxel-gemcitabine is associated with less adverse effects (toxicity in patients) than FOLFIRINOX.46 In this regard, we were very interested in synergistic or additive effects of DPAGT1 inhibitor in combination with paclitaxel. The synergistic or antagonistic activities of CPPB were assessed in vitro via checkerboard technique.47,48 In these experiments, CPPB displayed strong synergistic effects with paclitaxel in a wide range of concentrations against PD002. Table 3 summarizes the results of FIC index analyses for selected combinations of CPPB (IC50 35.0 μM) plus paclitaxel (IC50 1.25 μM) that showed synergistic combination (ΣFIC<0.5). The FIC index below 0.50 was observed for 20 combinations of two molecules out of 96 different concentrations (see Figure S6 in SI). The IC50 value of paclitaxel against PD002 was lowered (0.024–0.61 μM) in combination with CPPB (0.1–2.0 μM).

Table 3.

Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) of a Combination of CPPB and Paclitaxel against a Patient-derived Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma PD002.a

| Entry | Combination of A and Bb | CA and CB (μM)c | ΣFICd |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A: CPPB | 0.10 | 0.50 |

| B: Paclitaxel | 0.63 | ||

| 2 | A: CPPB | 0.10 | 0.13 |

| B: Paclitaxel | 0.16 | ||

| 3 | A: CPPB | 0.20 | 0.0096 |

| B: Paclitaxel | 0.0049 | ||

| 4 | A: CPPB | 0.20 | 0.021 |

| B: Paclitaxel | 0.020 | ||

| 5 | A: CPPB | 0.20 | 0.26 |

| B: Paclitaxel | 0.031 | ||

| 6 | A: CPPB | 2.0 | 0.021 |

| B: Paclitaxel | 0.020 | ||

| 7 | A: CPPB | 2.0 | 0.037 |

| B: Paclitaxel | 0.039 | ||

| 8 | A: CPPB | 2.0 | 0.26 |

| B: Paclitaxel | 0.31 |

ΣFIC index for the wells at growth–no growth interface.

The IC50 values of CPPB and paclitaxel against PD002 are 35.0 and 1.25 μM, respectively.

CA and CB are concentrations of A and B.

ΣFIC is the sum of fractional inhibitory concentration calculated by the equation ΣFIC = FICA + FICB = CA/IC50A + CB/IC50B. Cellular behavior of PD002 treated with paclitaxel or a combination with paclitaxel and CPPB was monitored over time by IncuCyte® live cell analysis (Supporting Information).

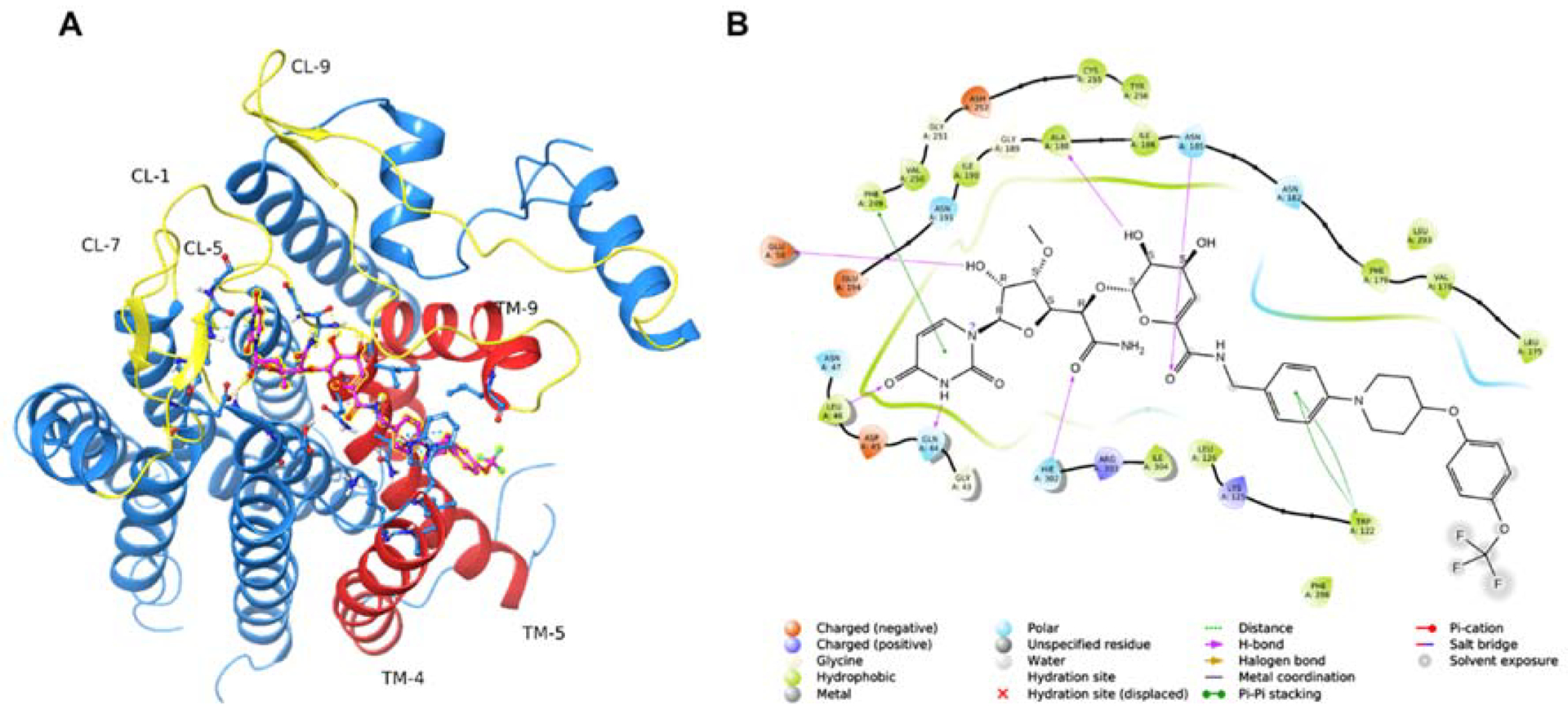

Interaction of CPPB with DPAGT1 (Modeling Studies).

DPAGT1 encompasses ten transmembrane segments, three loops on the ER (endoplasmic reticulum) side, and five loops on the cytoplasmic side. Four loops (CL-1, CL-5, CL-7, and CL-9) on the cytoplasmic side form the UDP-GlcNAc-binding domain.25,26 The hydrophobic tunnel created by the transmembrane segments (TM-4, TM-5 and CL-9) within the lipid bilayer is predicted to interact with dolychol-phosphate (Dol-P). The weak DPAGT1 inhibitors, O-methyl capuramycin (OM-CAP) and iso-capuramycin (I-CAP) (Table 1), yielded low docking scores (Glide Scores) using Schrödinger’s Glide program: the score for OM-CAP was -12.4 and for I-CAP was -10.9. These scores predicted that OM-CAP and I-CAP possess significantly lower affinity for DPAGT1 than CPPB, which showed a docking score of -16.6 (see Table S1 in SI).49–51 The docked CPPB-DPAGT1 structure illustrated in Figure 12 shows several key interactions. The C2’-OH acts as a donor in a hydrogen bond to the Glu56 carboxylate. This interaction is likely be lost when the C2’-OH is methylated. Pi-stacking interactions are observed between 1) Phe249 and the uracil ring, and 2) Trp122 and the trifluoromethoxybenzene in the hydrophobic moiety. Asn185 and Ash252 (protonated Asp) form hydrogen-bond(s) to the primary amide and the dihydropyran-hydroxy (C3”-OH) group, respectively. Additional hydrogen-bonds between the uridine ureido group and the backbone amides (Gln44 and Leu46) strengthen the ligand interaction. In this program, capuramycin (CAP), a strong MraY inhibitor with no DPAGT1 inhibitory activity, was successfully engineered to be a relatively strong DPAGT1 inhibitor by introducing a hydrophobic functional group, (((trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy) piperidin-1-yl)phenyl)methylamine at the C6“-position. This hydrophobic group allows the preferable conformation of the uridine-enopyranosiduronic moiety in the DPAGT1 biding domain, resulting in increased interactions with Asn185, Ash252, Glu56, and Phe249.

Figure 12.

Modeling CPPB-DPAGT1 Interaction to Design New Inhibitor Molecules.a

aDocking studies were performed using the human DPAGT1 with bound tunicamycin (PDB: 6BW6) (PMID 29459785). The biological unit was downloaded and prepared using the Protein Preparation Wizard of the Maestro Small Molecule Drug Discovery Suite (Schrödinger, LLC). The docking receptor grid was prepared using Schrödinger’s Glide program. (PMID 15027866, PMID 15027865). CPPB was built and prepared for docking using the LigPrep program using default settings (Schrödinger, LLC). A: Predicted binding pose of CPPB (highlighted ball & stick model) into DPAGT1. Key active site loops (yellow) and transmembrane regions (orange) are indicated. B: 2D ligand interaction diagram of the docked CPPB-DPAGT1 complex with key predicted interactions shown.

CL: cytoplasmic loop.; TM: transmembrane segment

A semi-synthesis of CPPB from A500359F.

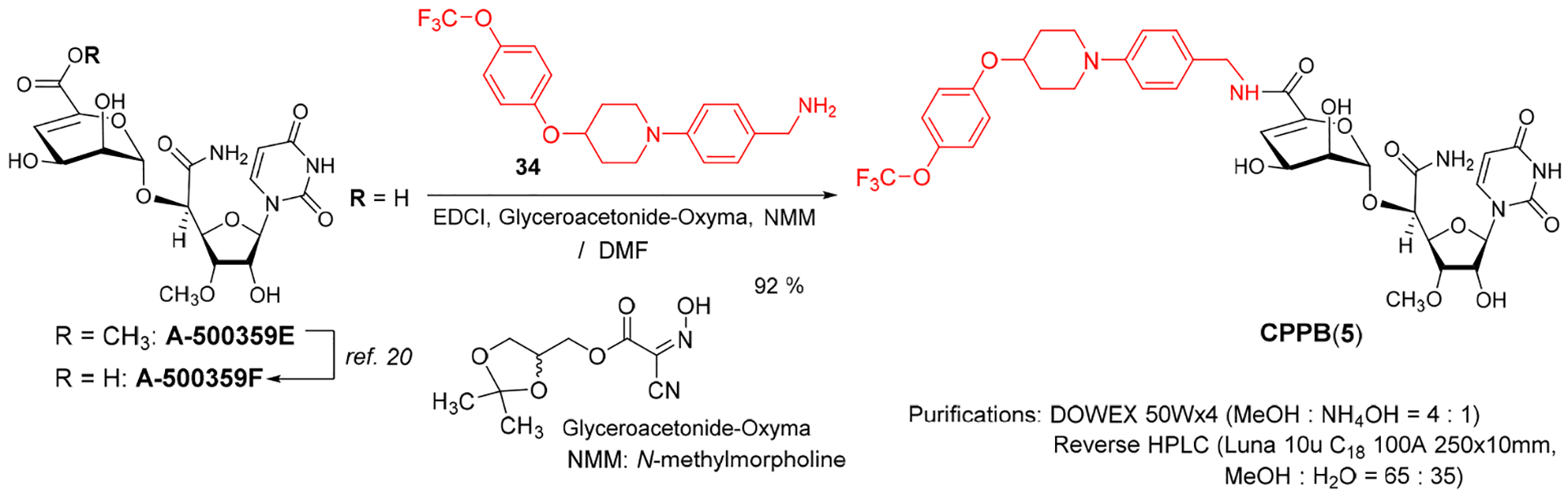

Pharmacological studies of CPPB (5) and its related analogues using appropriate animal models will be a focus of our future research efforts. Previously, a natural product A-5003659E was used to develop novel capuramycin analogues with strong MraY inhibitory activity (Hotoda et. al. 2003) (Figure 3).52 Its free-carboxylic acid analogue, A-500359F was also isolated from the capuramycin-producing strain, Streptomyces griseus Sank 60196. Saponification of A-5003659E to A-500359F was established by the Sankyo group.20 Although, the currently available synthetic schemes for capuramycin analogues (e.g., Scheme 3) include a relatively short number of chemical steps,22,23,53 a semi-synthetic approach is more feasible to deliver a large quantities of CPPB for pharmacological studies. To establish semi-synthesis of CPPB, A-500359F was first synthesized from the CAP-synthetic intermediate 32 (Scheme 3A) in a single step. Amide-forming reaction of synthetic A-500359F with (((trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy) piperidin-1-yl)phenyl)methylamine (34) was performed under an optimized condition using EDCI, glyceroacetonide-Oxyma, and NMM in DMF.54 All coupling reagents could be removed by partitions between CHCl3 and water and evaporation. The crude product was passed through DOWEX 50Wx4 column (MeOH : NH4OH = 4 : 1) to provide CPPB with >95% purity, which was further purified by C18-reverse HPLC (MeOH : H2O = 65 : 35) to yield pure CPPB (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

A Semi-synthesis of CPPB from Synthetic A-500359F, a Metabolite of S. griseus SANK60196.

CONCLUSION

This paper describes the identification of a new DPAGT1 inhibitor of capuramycin analogue, capuramycin phenoxypiperidinylbenzylamide (CPPB, 5) and its isostere I-CPPB (6). Previously, tunicamycin is the only DPAGT1 inhibitor that has been widely applied to the studies associated with protein misfolding in vitro.55,56 Tunicamycin displays cytotoxicity against cancer and healthy cells with low selectivity ratio.10 One of cytotoxicity mechanisms of tunicamycin is believed to be its ability to inhibit DPAGT1 enzyme functions. The DPAGT1 expression levels vary depending on the cell types; renal cancers and lymphomas express low-levels of DPAGT1, whereas, a majority of solid cancers express high-levels.57 Thus, the observed antiproliferative activity of tunicamycin against all types of cancer cells are difficult to understand solely by its DPAGT1 inhibitory activity. In our studies, CPPB showed ~7.5 times stronger DPAGT1 inhibitory activity than tunicamycin. However, unlike tunicamycin, CPPB did not inhibit growth of cancer cell lines at the IC50 values observed for tunicamycin (0.45 –7.5 μM). CPPB is a cell-permeable molecule which was demonstrated by IncuCyte® live cell analyses and immunofluorescence assays. In this article, we have studied effectiveness of CPPB on the expression levels of Snail, E-cadherin, and DPAGT1 primary in pancreatic cancers (Figures 7–10). CPPB decreased the Snail expression in commercially available pancreatic cancer cell lines (PANC-1, AsPC-1, and Capan-1) and a patient-derived pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell line (PD002) in a dose dependent manner. On the other hand, the E-cadherin expression level was increased in PD002 (a metastatic pancreatic cancer cell) or was not noticeably changed in PANC-1 at between 0.05–0.2 μM of CPPB. These biochemical data may support that a selective DPAGT1 inhibitor, CPPB is effective in inhibiting metastasis spread of the pancreatic cancer cells observed in scratch and transwell assays (Figures 5 and 6). Other than pancreatic cancers, a lower DPAGT1 expression cell, a colorectal adenocarcinoma (HCT-116) and a higher DPAGT1 expression cell, a cervical carcinoma (SiHa) were examined. CPPB did not inhibit migration of HCT-116, but strongly inhibited migration of SiHa in scratch assays at 0.2 μM (IC50 concentration against DPAGT1). These observations were supported by the biochemical analyses of the Snail and E-cadherin expression levels. Snail plays an important role in cancer progression. The accumulated evidences on Snail indicate that over-expression of Snail promotes drug resistance, tumor recurrence and metastasis.40 Although, only limited data have been generated in this article, CPPB’s Snail inhibitory activity observed in pancreatic and a several high DPAGT1-expressed cell lines suggests that selective DPAGT1 inhibitors have the potential to develop into less toxic anticancer therapeutics than anticancer drugs that are cytotoxic to all dividing cells in the body. CPPB is not cytotoxic against a series of cancer and healthy cell lines at 10 μM or higher concentrations. However, it showed a cytostatic activity against pancreatic cancers and a strong synergistic effect with paclitaxel; cytotoxic activity of paclitaxel was improved over 250-times against PD002 in combination with CPPB (0.2–2.0 μM). Docking studies of CPPB with the available DPAGT1 crystal structures provided insight into unique interactions, and thus, structure-based molecule design may be a fruitful approach to improve CPPB’s DPAGT1 affinity. A collaboration with Daiichi-Sankyo is essential to efficiently produce CPPB for in vivo studies using large-animal models such as dogs, pigs, and monkeys. We have demonstrated a semi-synthesis of CPPB from a capuramycin biosynthetic intermediate, A-500359F, that will secure a production of large amount of CPPB (Scheme 4). Our total synthetic scheme is amenable to produce gram-quantity of CPPB (Scheme 3). Extensive synergistic, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic studies of CPPB will be performed using preclinical animal models, and these data including detailed evaluation on in vivo efficacy against pancreatic and cervical cancers will be reported elsewhere.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemistry. General Information.

All chemicals were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification unless otherwise noted. THF, CH2Cl2, and DMF were purified via Innovative Technology’s Pure-Solve System. All reactions were performed under an Argon atmosphere. All stirring was performed with an internal magnetic stirrer. Reactions were monitored by TLC using 0.25 mm coated commercial silica gel plates (EMD, Silica Gel 60F254). TLC spots were visualized by UV light at 254 nm, or developed with ceric ammonium molybdate or anisaldehyde or copper sulfate or ninhydrin solutions by heating on a hot plate. Reactions were also monitored by using SHIMADZU LCMS-2020 with solvents: A: 0.1% formic acid in water, B: acetonitrile. Flash chromatography was performed with SiliCycle silica gel (Purasil 60 Å, 230–400 Mesh). Proton magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectral data were recorded on 400, and 500 MHz instruments. Carbon magnetic resonance (13C-NMR) spectral data were recorded on 100 and 125 MHz instruments. For all NMR spectra, chemical shifts (δH, δC) were quoted in parts per million (ppm), and J values were quoted in Hz. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were calibrated with residual undeuterated solvent (CDCl3: δH = 7.26 ppm, δC = 77.16 ppm; CD3CN: δH = 1.94 ppm, δC = 1.32ppm; CD3OD: δH =3.31 ppm, δC =49.00 ppm; DMSO-d6: δH = 2.50 ppm, δC = 39.52 ppm; D2O: δH = 4.79 ppm) as an internal reference. The following abbreviations were used to designate the multiplicities: s = singlet, d = doublet, dd = double doublets, t = triplet, q = quartet, quin = quintet, hept = heptet, m = multiplet, br = broad. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer FT1600 spectrometer. HPLC analyses were performed with a Shimadzu LC-20AD HPLC system. HR-MS data were obtained from a Waters Synapt G2-Si (ion mobility mass spectrometer with nanoelectrospray ionization). All assayed compounds were purified by reverse HPLC to be ≥95% purity.

(2S,3S,4S,5R,6R)-2-((1S)-((2R,5R)-3-Acetoxy-5-(3-((benzyloxy)methyl)-2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-4-methoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)(cyano)methoxy)-6-((2-chloroacetoxy)methyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4,5-triyl triacetate (15).

To a stirred suspension of 13 (0.17 g, 0.38 mmol), 14 (0.37 g, 0.75 mmol), MS3Å (0.50 g) and SrCO3 (0.28 g, 1.88 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (9.4 mL) were added AgBF4 (0.037 g, 0.19 mmol) and NIS (0.25 g, 1.13 mmol) at 0 °C. After being stirred for 19h, the reaction mixture was added Et3N (1.0 mL) and passed through a silica gel pad (hexanes/EtOAc = 1/4). The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc = 2/1 to 1/2) to afford 15 (0.24 g, 78%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.40 – 7.27 (m, 6H), 6.07 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 6.00 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.51 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 5.47 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 5.37 (dd, J = 3.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 5.28 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 5.22 – 5.15 (m, 2H), 4.84 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.71 (s, 2H), 4.41 (dd, J = 5.5, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.39 – 4.35 (m, 1H), 4.33 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.14 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 2H), 4.03 – 4.01 (m, 1H), 3.93 (ddd, J = 8.9, 5.9, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.47 (s, 3H), 2.20 (s, 3H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 2.07 (s, 3H), 2.02 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.20, 169.84, 169.50, 166.92, 162.19, 150.97, 137.75, 137.46, 128.32 (2C), 127.72, 127.69 (2C), 113.96, 103.58, 96.29, 88.68, 80.93, 80.09, 72.30, 70.42, 69.60, 68.46, 67.94, 65.16, 64.35, 63.58, 59.26, 40.61, 31.58, 20.70, 20.66, 20.62, 20.57; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C35H41ClN3O17 [M + H] 810.2125, found: 810.2151.

(2R,3S,4S,5R,6R)-2-((1R)-1-((2S,5R)-3-Acetoxy-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-4-methoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-amino-2-oxoethoxy)-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4,5-triyl triacetate (16).

To a stirred solution of 15 (0.24 g, 0.29 mmol) in a 9:1 mixture of EtOH and H2O (2.9 mL) were added HgCl2 (0.16 g, 0.59 mmol) and acetaldoxime (0.18 mL, 2.9 mmol). After being stirred for 13h at r.t., the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was quenched with aq. NaHCO3, and extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc = 1/2 to CHCl3/MeOH = 96/4) to afford the amide (0.21 g, 87%). To a solution of the amide (0.21 g, 0.26 mmol) in a 1:1 mixture of THF and MeOH (2.6 mL) was added thiourea (0.059 g, 0.77 mmol). After being stirred for 11h at 50 °C, the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was diluted with H2O and extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 98/2 to 97/3 to 96/4) to afford the primary alcohol (0.15 g, 75%). To a stirred solution of the primary alcohol (0.15 g, 0.19 mmol) and AcOH (0.040 mL) in a 1:1 mixture of THF and iPrOH (2.0 mL) was added 10% Pd/C (0.12 g) under N2. H2 gas was introduced and the reaction mixture was stirred under H2 atmosphere for 3h, the solution was filtered through Celite and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 97/3 to 92/8) to afford 16 (0.10 g, 81%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.08 (brs, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (brs, 1H), 6.12 (brs, 1H), 6.00 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.87 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 5.55 – 5.52 (m, 1H), 5.26 – 5.22 (m, 2H), 5.20 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 4.53 (dd, J = 6.5, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.06 (dd, J = 5.5, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 3.76 – 3.71 (m, 1H), 3.69 – 3.57 (m, 2H), 3.44 (s, 3H), 2.17 (s, 3H), 2.15 (s, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.42, 170.46, 170.46, 170.40, 163.10, 150.03, 139.50, 103.61, 97.15, 96.95, 88.50, 81.26, 80.96, 75.33, 72.91, 69.67, 68.89, 65.54, 61.27, 59.05, 50.86, 20.82, 20.75, 20.67, 20.59; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C25H34N3O16 [M + H] 632.1939, found: 632.1963.

(2S,3S,4S)-3,4-Diacetoxy-2-((1R)-1-((2S,5R)-3-acetoxy-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-4-methoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-amino-2-oxoethoxy)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-6-carboxylic acid (18).

To a stirred solution of 16 (0.10 g, 0.16 mmol) and DMSO (0.11 mL, 1.57 mmol) in a 5:1 mixture of CH2Cl2 and Et3N (0.80 mL) was added SO3•pyridine (0.25 g, 1.57 mmol). After being stirred for 3h at r.t., the reaction mixture was added H2O (0.16 mL) and passed through a silica gel pad (CHCl3/MeOH = 92/8) to provide the crude 17. To a stirred solution of the crude mixture in tBuOH (1.0 mL) and 2-methyl-2-butene (0.5 mL) was added a solution of NaClO2 (0.071 g, 0.78 mmol) and NaH2PO4•2H2O (0.12 g, 0.78 mmol) in H2O (1.0 mL). After being stirred for 4h at r.t., the reaction was quenched with H2O and extracted with CHCl3/MeOH (9/1). The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 9/1) to afford 18 (0.078 g, 85%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.77 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.94 (d, J = 11.7 Hz, 1H), 5.94 (s, 1H), 5.78 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 5.66 (dd, J = 4.5, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 5.56 (ddd, J = 4.7, 3.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 5.32 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 4.99 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 4.85 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 4.60 (dd, J = 5.2, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.39 (s, 3H), 2.13 (s, 3H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 2.05 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 172.79, 172.06, 171.60, 167.79, 166.01, 152.05, 148.16, 140.97, 104.23, 103.98, 97.91, 88.13, 83.38, 82.91, 76.56, 71.95, 65.17, 65.06, 59.41, 20.75, 20.63, 20.57; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C23H28N3O15 [M + H] 586.1520, found: 586.1549.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((1R)-1-((2S,5R)-3-Acetoxy-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-4-methoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-amino-2-oxoethoxy)-6-(((S)-2-oxoazepan-3-yl)carbamoyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (19).

To a stirred solution of 18 (31 mg, 0.053 mmol), 2-(S)-aminocaprolactam (26 mg, 0.16 mmol), HOBt (21 mg, 0.16 mmol) and NMM (58 μL, 0.53 mmol) in DMF (0.26 mL) was added EDCI (51 mg, 0.26 mmol). After being stirred for 6h at r.t., the reaction was quenched with aq. NaHCO3, and extracted with CHCl3/MeOH (9/1). The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 95/5) to afford 19 (30 mg, 82%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.68 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.02 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 5.91 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 5.89 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H), 5.73 (dd, J = 4.4, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 5.68 – 5.65 (m, 1H), 5.51 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 5.01 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.76 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.62 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 4.60 – 4.57 (m, 1H), 3.98 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 3.35 (s, 3H), 2.11 (s, 3H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 2.05 (s, 3H), 2.03 – 1.98 (m, 2H), 1.91 – 1.83 (m, 2H), 1.65 – 1.56 (m, 2H), 1.44 – 1.37 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 176.12, 172.32, 171.66, 171.29, 171.21, 165.96, 160.96, 151.90, 144.61, 141.42, 106.25, 103.54, 98.81, 88.77, 83.41, 79.28, 77.39, 74.79, 64.91, 64.49, 59.26, 57.36, 53.25, 42.36, 32.19, 29.75, 28.94, 20.54, 20.41, 20.32; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C29H38N5O15 [M + H] 696.2364, found: 696.2391.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((1R)-2-Amino-1-((2S,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-3-hydroxy-4-methoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-oxoethoxy)-3,4-dihydroxy-N-((S)-2-oxoazepan-3-yl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-6-carboxamide (3).

A solution of 19 (30 mg, 0.043 mmol) in a 5:1 mixture of MeOH and Et3N (0.60 mL) was stirred for 5h at r.t., and concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by reverse-phase HPLC [column: Luna® (C18, 10 μm, 100 Å, 250 × 10 mm), solvents: 15:85 MeOH:H2O, flow rate: 3.0 mL/min, UV: 254 nm, retention time: 20 min] to afford I-CAP (3, 24 mg, 98%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.92 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.02 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 5.88 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 5.74 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.23 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 4.67 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.59 – 4.54 (m, 2H), 4.38 (t, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 4.29 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 3.98 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 3.43 (s, 3H), 2.06 – 1.99 (m, 2H), 1.89 – 1.81 (m, 2H), 1.62 – 1.45 (m, 2H), 1.44 – 1.33 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 176.27, 173.46, 166.15, 161.85, 152.32, 144.23, 141.91, 109.37, 102.82, 101.22, 90.27, 83.49, 81.02, 78.93, 74.54, 68.51, 63.53, 58.67, 53.35, 42.48, 32.36, 29.91, 29.06; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C23H32N5O12 [M + H] 570.2048, found: 570.2071.

(2S,3S,4S,5R,6R)-2-((S)-((3aR,4R,6R,6aR)-6-(3-((Benzyloxy)methyl)-2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-2,2-dimethyltetrahydrofuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl)(cyano)methoxy)-6-((2-chloroacetoxy)methyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4,5-triyl triacetate (21).

To a stirred suspension of 20 (0.24 g, 0.56 mmol), 14 (0.55 g, 1.12 mmol), MS3Å (0.72 g), and SrCO3 (0.41 g, 2.80 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (14.0 mL) were added AgBF4 (0.055 g, 0.28 mmol) and NIS (0.25 g, 1.12 mmol) at 0 °C. After being stirred for 12h, the reaction mixture was added Et3N (1.0 mL), and passed through a silica gel pad (hexanes/EtOAc = 1/4). The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc = 6/4 – 4/6) to afford 21 (0.39 g, 88%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.37 – 7.28 (m, 5H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.82 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.61 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 5.50 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 5.42 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 5.35 – 5.27 (m, 1H), 5.23 (dd, J = 10.0, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 5.07 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 4.98 (dd, J = 6.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 4.84 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 4.69 (s, 2H), 4.43 (dd, J = 7.1, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (dd, J = 12.2, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 4.17 – 4.07 (m, 2H), 4.05 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 3.97 – 3.92 (m, 1H), 2.16 (s, 3H), 2.02 (s, 3H), 1.98 (s, 3H), 1.59 (s, 3H), 1.39 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.80, 169.57, 169.47, 166.80, 162.08, 150.84, 140.89, 137.67, 128.33 (2C), 127.91, 127.77, 127.63 (2C), 115.23, 114.72, 102.84, 96.56, 96.30, 86.55, 84.15, 80.95, 72.42, 70.41, 69.41, 68.39 (2C), 66.04, 65.35, 62.90, 40.52, 27.03, 25.20, 20.73, 20.64, 20.59; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C35H41ClN3O16 [M + H] 794.2175, found: 794.2198.

(2R,3S,4S,5R,6R)-2-((R)-2-Amino-1-((3aR,4S,6R,6aR)-6-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-2,2-dimethyltetrahydrofuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl)-2-oxoethoxy)-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4,5-triyl triacetate (22).

To a stirred solution of 21 (0.39 g, 0.49 mmol) in a 9:1 mixture of EtOH and H2O (4.9 mL) were added HgCl2 (0.27 g, 0.98 mmol) and acetaldoxime (0.30 mL, 4.9 mmol). After being stirred for 12h at r.t., the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was diluted with aq.NaHCO3, and extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc = 1/2 to CHCl3/MeOH = 97/3) to afford the amide (0.36 g, 91%). To a solution of the amide (0.36 g, 0.45 mmol) in a 1:1 mixture of THF and MeOH (4.5 mL) was added thiourea (0.10 g, 1.34 mmol). After being stirred for 11h at 50 °C, the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was diluted with H2O, and extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 98/2 to 97/3 to 96/4) to afford the primary alcohol (0.25 g, 76%). To a stirred solution of the alcohol (0.25 g, 0.34 mmol) and AcOH (0.08 mL) in a 1:1 mixture of THF and iPrOH (4.0 mL) was added 10% Pd/C (0.20 g) under N2. H2 gas was introduced and the reaction mixture was stirred under H2 atmosphere. After being stirred for 4h at r.t., the reaction mixture was filtered through Celite and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 96/4 to 92/8) to afford 22 (0.17 g, 80%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.45 (brs, 1H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (brs, 1H), 6.17 (brs, 1H), 5.78 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.60 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.43 (dd, J = 10.1, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 5.33 (dd, J = 3.5, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.20 (t, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 5.12 – 5.05 (m, 1H), 5.03 (dd, J = 6.4, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 4.98 (s, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (dt, J = 10.1, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.60 – 3.53 (m, 2H), 2.14 (s, 3H), 2.07 (s, 3H), 2.02 (s, 3H), 1.55 (s, 3H), 1.35 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.68, 170.40, 170.28, 170.24, 163.27, 150.13, 142.81, 114.72, 102.85, 96.39, 87.34, 84.26, 80.35, 71.92, 69.35, 68.64, 66.03, 61.16, 27.25, 25.42, 20.83, 20.77, 20.74; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C25H34N3O15 [M + H] 616.1990, found: 616.2018.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((R)-2-Amino-1-((3aR,4S,6R,6aR)-6-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-2,2-dimethyltetrahydrofuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl)-2-oxoethoxy)-6-(((S)-2-oxoazepan-3-yl)carbamoyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (23).

To a stirred solution of 22 (0.17 g, 0.27 mmol) and DMSO (0.19 mL, 2.72 mmol) in a 5:1 mixture of CH2Cl2 and Et3N (1.4 mL) was added SO3•pyridine (0.43 g, 2.72 mmol). After being stirred for 3h at r.t., the reaction mixture was added H2O (0.27 mL) and passed through a silica gel pad (CHCl3/MeOH = 92/8). To a stirred solution of the crude mixture in tBuOH (1.0 mL) and 2-methyl-2-butene (0.5 mL) was added a solution of NaClO2 (0.12 g, 1.36 mmol) and NaH2PO4•2H2O (0.21 g, 1.36 mmol) in H2O (1.0 mL). After being stirred for 5h at r.t., the reaction was extracted with CHCl3/MeOH (9/1). The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 9/1) to afford the acid (0.13 g, 81%). To a stirred solution of the acid (28 mg, 0.049 mmol), 2-(S)-aminocaprolactam (24 mg, 0.15 mmol), HOBt (20 mg, 0.15 mmol) and NMM (54 μL, 0.49 mmol) in DMF (0.25 mL) was added EDCI (47 mg, 0.25 mmol). After being stirred for 14h at r.t., the reaction was quenched with aq.NaHCO3, and extracted with CHCl3/MeOH (9/1). The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 95/5) to afford 23 (30 mg, 89%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.79 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.98 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 5.84 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 5.78 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.62 (dd, J = 4.5, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 5.51 – 5.48 (m, 1H), 5.45 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 4.74 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 4.71 (dd, J = 6.2, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (dd, J = 6.2, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 4.59 – 4.55 (m, 2H), 3.76 – 3.67 (m, 4H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 3H), 1.86 (d, J = 13.4 Hz, 3H), 1.63 – 1.52 (m, 3H), 1.51 (s, 3H), 1.45 – 1.34 (m, 3H), 1.25 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 176.35, 172.24, 171.62, 171.28, 166.24, 161.14, 151.99, 144.75, 142.76, 115.34, 106.38, 102.91, 98.75, 93.55, 87.12, 85.94, 82.02, 78.13, 67.16, 64.99, 64.46, 56.04, 53.46, 46.10, 42.52, 42.43, 32.25, 29.89, 29.08, 27.47, 25.47, 20.61, 20.52; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C29H38N5O14 [M + H] 680.2415, found: 680.2432.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((1R)-2-Amino-1-((2S,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-3,4-dihydroxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-oxoethoxy)-3,4-dihydroxy-N-((S)-2-oxoazepan-3-yl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-6-carboxamide (4).

A solution of 23 (30 mg, 0.044 mmol) in a 4:1 mixture of TFA and H2O (0.88 mL) was stirred for 4h at r.t., and concentrated in vacuo. A solution of the crude diol in a 5:1 mixture of MeOH and Et3N (0.88 mL) was stirred for 9h at r.t., filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by reverse-phase HPLC [column: Luna® (C18, 10 μm, 100 Å, 250 × 10 mm), solvents: 15:85 MeOH:H2O, flow rate: 3.0 mL/min, UV: 254 nm, retention time: 16 min] to afford DM-CAP (4, 22 mg, 90%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.94 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.03 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 5.85 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 5.73 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.19 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 4.68 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 4.61 (dd, J = 11.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 4.54 (dd, J = 5.8, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 4.36 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 4.30 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (t, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.97 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.43 – 3.38 (m, 1H), 3.03 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.70 – 2.64 (m, 1H), 2.07 – 1.97 (m, 2H), 1.81 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 2H), 1.62 (q, J = 11.9, 10.7 Hz, 1H), 1.39 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 176.85, 174.05, 166.21, 162.02, 152.21, 144.60, 141.91, 108.72, 102.50, 101.60, 90.76, 84.77, 79.50, 75.68, 71.40, 63.63, 60.06, 53.44, 42.50, 31.89, 29.82, 29.14; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C22H30N5O12 [M + H] 556.1891, found: 556.1912.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((1R)-1-((2S,5R)-4-Acetoxy-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-3-methoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-amino-2-oxoethoxy)-6-((4-(4-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)benzyl)carbamoyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (37).

To a stirred solution of 32 (55 mg, 0.094 mmol), 34 (0.10 g, 0.28 mmol), HOBt (38 mg, 0.28 mmol) and NMM (95 μL, 0.94 mmol) in DMF (0.47 mL) was added EDCI (90 mg, 0.47 mmol). After being stirred for 7h at r.t., the reaction mixture was quenched with aq.NaHCO3, and extracted with CHCl3/MeOH (9/1). The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 95/5) to afford 37 (76 mg, 87%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.71 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 5.97 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 5.91 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.87 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 5.74 (dd, J = 4.5, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 5.67 (ddd, J = 4.5, 2.8, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.43 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 5.28 (dd, J = 5.1, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 4.70 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 4.54 (dq, J = 7.5, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 4.42 (d, J = 14.5 Hz, 1H), 4.38 (dd, J = 6.2, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 3.82 – 3.79 (m, 1H), 3.48 (td, J = 9.0, 6.8, 3.5 Hz, 3H), 3.13 – 3.06 (m, 2H), 3.05 (s, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.06 (s, 3H), 1.87 (dtd, J = 12.3, 8.2, 3.6 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 172.85, 171.84, 171.43, 171.17, 166.07, 162.39, 157.61, 152.11, 151.92, 144.94, 143.92, 141.57, 130.89, 130.02 (2C), 123.59 (2C), 118.04 (2C), 117.98 (2C), 106.19, 103.75, 98.26, 89.36, 83.17, 78.98, 76.60, 74.71, 73.98, 64.75, 59.35, 48.18, 48.16, 31.43 (2C), 20.70, 20.52, 20.49; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C42H47F3N5O16 [M + H] 934.2970, found 934.2998.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((1R)-2-Amino-1-((2S,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-4-hydroxy-3-methoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-oxoethoxy)-3,4-dihydroxy-N-(4-(4-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)benzyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-6-carboxamide (5).

A solution of 37 (76 mg, 0.082 mmol) in a 5:1 mixture of MeOH and Et3N (1.6 mL) was stirred for 6h at r.t., and concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by reverse-phase HPLC [column: Luna® (C18, 10 μm, 100 Å, 250 × 10 mm), solvents: 65:35 MeOH:H2O, flow rate: 3.0 mL/min, UV: 254 nm, retention time: 18 min] to afford CPPB (5, 63 mg, 95%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.86 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (dd, J = 10.9, 8.6 Hz, 4H), 7.02 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 5.98 (dd, J = 3.3, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 5.80 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.21 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.68 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.54 (dp, J = 7.3, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (dd, J = 5.2, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (d, J = 14.5 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (t, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (d, J = 14.6 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.06 – 4.02 (m, 1H), 3.66 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 3.52 – 3.45 (m, 3H), 3.19 (s, 3H), 3.08 (ddd, J = 12.3, 8.6, 3.4 Hz, 3H), 2.15 – 2.07 (m, 2H), 1.86 (dtd, J = 12.2, 8.3, 3.5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 173.68, 166.16, 163.31, 157.62, 152.18, 152.08, 144.15, 141.83, 130.91, 129.76 (2C), 123.58 (2C), 118.03 (4C), 109.58, 102.74, 100.64, 90.83, 83.32, 80.35, 77.51, 74.27, 74.01, 67.61, 63.48, 58.61, 48.20 (2C), 43.51, 31.47 (2C); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C36H41F3N5O13 [M + H] 808.2653, found 808.2675.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((1R)-1-((2S,5R)-3-Acetoxy-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-4-methoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-amino-2-oxoethoxy)-6-((4-(4-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)benzyl)carbamoyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (35).

To a stirred solution of 18 (33 mg, 0.056 mmol), 34 (62 mg, 0.17 mmol), HOBt (23 mg, 0.17 mmol) and NMM (62 μL, 0.56 mmol) in DMF (0.28 mL) was added EDCI (54 mg, 0.28 mmol). After being stirred for 14h at r.t., the reaction was quenched with aq.NaHCO3, and extracted with CHCl3/MeOH (9/1). The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 95/5) to afford 35 (43 mg, 82%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.69 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 5.99 – 5.97 (m, 1H), 5.95 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 5.91 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.74 – 5.71 (m, 1H), 5.66 – 5.63 (m, 1H), 5.46 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 5.05 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.57 – 4.52 (m, 1H), 4.49 (d, J = 14.5 Hz, 1H), 4.39 – 4.34 (m, 1H), 4.30 (d, J = 14.7 Hz, 1H), 3.84 – 3.80 (m, 1H), 3.64 (s, 3H), 3.53 – 3.45 (m, 2H), 3.13 – 3.06 (m, 2H), 2.83 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 2.10 (s, 3H), 2.07 (s, 3H), 2.06 (s, 3H), 1.87 (dtd, J = 12.7, 8.5, 3.5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 172.92, 171.74, 171.36, 170.39, 166.18, 162.23, 157.56, 152.06, 151.81, 145.05, 140.90, 130.78, 129.96 (2C), 123.52 (2C), 117.96 (2C), 117.92 (2C), 105.75, 103.47, 98.22, 88.92, 82.72, 78.21, 76.44, 73.95, 67.92, 64.42, 61.21, 58.65, 58.20, 48.10 (2C), 43.57, 31.38 (2C), 20.60, 20.44, 20.39; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C42H47F3N5O16 [M + H] 934.2970, found 934.2991.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((1R)-2-Amino-1-((2S,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-3-hydroxy-4-methoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-oxoethoxy)-3,4-dihydroxy-N-(4-(4-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)benzyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-6-carboxamide (6).

A solution of 35 (43 mg, 0.046 mmol) in a 5:1 mixture of MeOH and Et3N (0.92 mL) was stirred for 6h at r.t., and concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by reverse-phase HPLC [column: Luna® (C18, 10 μm, 100 Å, 250 × 10 mm), solvents: 65:35 MeOH:H2O, flow rate: 3.0 mL/min, UV: 254 nm, retention time: 19 min] to afford I-CPPB (6, 35 mg, 93%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.79 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 4H), 7.02 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 5.98 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 5.94 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 5.77 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.36 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 4.67 – 4.65 (m, 1H), 4.61 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (dd, J = 8.6, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.36 – 4.33 (m, 1H), 4.27 (dd, J = 5.4, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 3.71 – 3.65 (m, 2H), 3.51 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 2H), 3.48 (s, 3H), 3.25 – 3.18 (m, 2H), 2.13 – 2.00 (m, 3H), 1.92 – 1.76 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 173.68, 166.15, 163.30, 157.62, 152.18, 152.08, 144.15, 141.83, 130.90, 129.76 (2C), 123.58 (2C), 118.10 (2C), 118.02 (2C), 109.57, 102.73, 100.63, 90.83, 83.32, 80.35, 77.51, 74.27, 74.01, 67.61, 63.48, 58.61, 48.20 (2C), 43.51, 31.47 (2C); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C36H41F3N5O13 [M + H] 808.2653, found 808.2668.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((1R)-2-Amino-1-((2S,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-3,4-dimethoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-oxoethoxy)-6-((4-(4-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)benzyl)carbamoyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (38).

To a stirred solution of 33 (38 mg, 0.068 mmol), 34 (75 mg, 0.20 mmol), HOBt (28 mg, 0.20 mmol) and NMM (75 μL, 0.68 mmol) in DMF (0.34 mL) was added EDCI (65 mg, 0.34 mmol). After being stirred for 7h at r.t., the reaction was quenched with aq.NaHCO3, and extracted with CHCl3/MeOH (9/1). The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 95/5) to afford 38 (53 mg, 86%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.75 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 5.98 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 5.96 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.85 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 5.71 – 5.66 (m, 2H), 5.43 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.70 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 4.57 – 4.51 (m, 1H), 4.45 – 4.40 (m, 2H), 4.34 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (dd, J = 4.9, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.60 (dd, J = 6.9, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 3.50 (td, J = 7.6, 7.0, 3.3 Hz, 2H), 3.46 (s, 3H), 3.11 (dd, J = 8.9, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 3.08 (s, 3H), 2.83 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 2.14 (dd, J = 8.7, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 2.10 (s, 3H), 2.07 (s, 3H), 1.87 (dtd, J = 12.5, 8.2, 3.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 172.98, 171.81, 171.42, 166.22, 162.30, 157.62, 152.12, 151.87, 145.11, 140.96, 130.85, 130.02 (2C), 123.58 (2C), 118.03 (2C), 117.98 (2C), 105.81, 103.54, 98.28, 88.98, 82.79, 82.54, 78.28, 76.50, 74.02, 64.59, 64.49, 61.28, 58.72, 58.27, 48.17 (2C), 43.64, 42.08, 31.45 (2C), 20.67, 20.51; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C41H47F3N5O15 [M + H] 906.3021, found 906.3045.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((1R)-2-Amino-1-((2S,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-3,4-dimethoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-oxoethoxy)-3,4-dihydroxy-N-(4-(4-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)benzyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-6-carboxamide (7).

A solution of 38 (53 mg, 0.059 mmol) in a 5:1 mixture of MeOH and Et3N (1.2 mL) was stirred for 6h at r.t., and concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by reverse-phase HPLC [column: Luna® (C18, 10 μm, 100 Å, 250 × 10 mm), solvents: 65:35 MeOH:H2O, flow rate: 3.0 mL/min, UV: 254 nm, retention time: 21 min] to afford OM-CPPB (7, 46 mg, 96%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.89 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 5.98 (dd, J = 3.0, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 5.85 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.22 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 4.67 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 4.57 – 4.51 (m, 1H), 4.46 (dd, J = 6.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.43 (d, J = 14.9 Hz, 1H), 4.40 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 4.32 (d, J = 14.5 Hz, 1H), 4.08 (t, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (t, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 3.52 – 3.47 (m, 2H), 3.45 (s, 3H), 3.13 (s, 3H), 3.08 (td, J = 9.1, 4.6 Hz, 2H), 2.15 – 2.09 (m, 2H), 1.91 – 1.82 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 173.61, 166.17, 163.21, 157.62, 152.09, 151.92, 144.02, 141.57, 130.94, 129.89 (2C), 123.59 (2C), 118.03 (2C), 117.98 (2C), 109.78, 102.61, 100.76, 88.94, 83.23, 82.71, 78.58, 77.02, 74.02, 67.27, 63.42, 60.07, 58.70, 58.37, 48.18, 47.87, 45.76, 43.53, 31.46 (2C); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C37H43F3N5O13 [M + H] 822.2809, found 822.2838.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((R)-2-Amino-1-((3aR,4S,6R,6aR)-6-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-2,2-dimethyltetrahydrofuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl)-2-oxoethoxy)-6-((4-(4-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)benzyl)carbamoyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-3,4-diyl diacetate (36).

To a stirred solution of 31 (27 mg, 0.047 mmol), 34 (52 mg, 0.14 mmol), HOBt (19 mg, 0.14 mmol) and NMM (52 μL, 0.47 mmol) in DMF (0.24 mL) was added EDCI (45 mg, 0.24 mmol). After being stirred for 11h at r.t., the reaction was quenched with aq.NaHCO3, and extracted with CHCl3/MeOH (9/1). The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 95/5) to afford 36 (37 mg, 84%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.69 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 4H), 7.02 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 5.99 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 5.87 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 5.83 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.66 (dd, J = 4.4, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 5.57 – 5.54 (m, 1H), 5.41 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.70 (dd, J = 6.3, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 4.63 (dd, J = 6.4, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 4.57 – 4.52 (m, 1H), 4.39 (s, 2H), 3.79 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (s, 1H), 3.49 (ddd, J = 10.9, 6.4, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 3.09 (ddd, J = 12.4, 8.6, 3.4 Hz, 2H), 2.83 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 2.16 – 2.09 (m, 2H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 2.05 (s, 3H), 1.87 (dtd, J = 12.1, 8.1, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 1.53 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 172.59, 171.76, 171.36, 166.16, 162.38, 157.61, 152.04, 151.92, 145.03, 142.46, 130.80, 129.66 (2C), 123.59 (2C), 118.05 (2C), 118.02 (2C), 115.67, 106.20, 103.33, 98.57, 92.78, 86.55, 85.61, 81.72, 77.88, 73.99, 64.84, 64.58, 61.28, 48.20 (2C), 43.59, 31.47 (2C), 27.52, 25.45, 20.66, 20.51; HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C42H47F3N5O15 [M + H] 918.3021, found 918.3053.

(2S,3S,4S)-2-((1R)-2-Amino-1-((2S,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-3,4-dihydroxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-oxoethoxy)-3,4-dihydroxy-N-(4-(4-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)benzyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-6-carboxamide (8).

A solution of 35 (37 mg, 0.040 mmol) in a 4:1 mixture of TFA and H2O (0.80 mL) was stirred for 4h at r.t., and concentrated in vacuo. A solution of the crude alcohol in a 5:1 mixture of MeOH and Et3N (0.80 mL) was stirred for 10h at r.t., and concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by reverse-phase HPLC [column: Luna® (C18, 10 μm, 100 Å, 250 × 10 mm), solvents: 35:65 MeOH:H2O, flow rate: 3.0 mL/min, UV: 254 nm, retention time: 15 min] to afford DM-CPPB (8, 29 mg, 91%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.92 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 2H), 7.18 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.01 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 5.80 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 5.73 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.14 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.57 – 4.51 (m, 1H), 4.50 (dd, J = 6.7, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 4.41 – 4.31 (m, 3H), 4.16 (dd, J = 6.6, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.04 (dd, J = 4.9, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (dd, J = 6.7, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 3.47 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 3.27 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 3.07 (ddd, J = 17.0, 8.1, 4.0 Hz, 2H), 2.37 – 2.29 (m, 1H), 2.16 – 2.07 (m, 2H), 1.86 (dtd, J = 12.3, 8.2, 3.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 174.07, 170.14, 166.22, 163.14, 157.62, 152.12, 151.99, 144.89, 141.84, 131.07, 129.64 (2C), 123.58 (2C), 118.08 (2C), 118.03 (2C), 116.78, 108.52, 102.45, 101.32, 91.15, 84.20, 78.81, 75.49, 74.02, 71.19, 69.27, 63.69, 60.09, 47.81 (2C), 31.46 (2C); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C35H39F3N5O13 [M + H] 794.2496, found 794.2522.

(2R)-2-(((2S,3S,4S)-3,4-Dihydroxy-6-(((4-(4-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)benzyl)amino)methyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-2-((2S,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-4-hydroxy-3-methoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)acetamide (9).

To a stirred solution of 16 (5.8 mg, 0.0092 mmol) and DMSO (0.065 mL, 0.92 mmol) in a 5:1 mixture of CH2Cl2 and Et3N (0.5 mL) was added SO3•pyridine (15 mg, 0.092 mmol). After being stirred for 2h at r.t., the reaction mixture was added H2O (0.1 mL) and passed through a silica gel pad (CHCl3/MeOH = 93/7) to afford the crude 17: this was used without purification. To a stirred solution of the crude 17 and 34 (17 mg, 0.046 mmol) in CH3CN (0.5 mL) was added NaB(CN)H3 (5.8 mg, 0.092 mol). After being stirred for 3h at r.t., the reaction was quenched with aq.NaHCO3, and extracted with CHCl3/MeOH (9/1). The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was passed through a silica gel pad (CHCl3/MeOH = 9/1). The solution of the crude product in a 5:1 mixture of MeOH and Et3N (0.5 mL) was stirred for 8h at r.t., and concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by reverse-phase HPLC [column: Luna® (C18, 10 μm, 100 Å, 250 × 10 mm), solvents: 65:35 MeOH:H2O, flow rate: 3.0 mL/min, UV: 254 nm, retention time: 15 min] to afford CPPA (9, 4.6 mg, 65% for 3 steps): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.02 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 5.90 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.73 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.06 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 4.57 (dd, J = 6.4, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (td, J = 4.4, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 4.26 (d, J = 26.3 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 3.90 – 3.77 (m, 3H), 3.55 – 3.50 (m, 2H), 3.49 (s, 3H), 3.15 – 3.06 (m, 3H), 2.16 – 2.07 (m, 3H), 1.86 (m, J = 8.8, 4.3 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 174.07, 165.86, 163.68, 157.58, 151.26, 144.88, 142.07, 131.25, 129.37 (2C), 123.22 (2C), 118.03 (4C), 109.57, 102.60, 100.40, 90.92, 83.37, 80.46, 77.56, 74.63, 73.77, 73.15, 67.78, 63.30, 58.33, 48.19 (2C), 43.21, 30.74 (2C); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C36H43N3F5O12 [M + H] 794.2860, found 794.2877.

(2R)-2-(((2S,3S,4S)-3,4-Dihydroxy-6-(((4-(4-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenoxy)piperidin-1-yl)benzyl)amino)methyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-2-((2S,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)-3-hydroxy-4-methoxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)acetamide (10).