Abstract

Rationale:

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) may be cardioprotective because it accepts cholesterol from macrophages via the cholesterol transport proteins ABCA1 and ABCG1. The ABCA1-specific cellular cholesterol efflux capacity (ABCA1 CEC) of HDL strongly and negatively associates with cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, but how diabetes impacts that step is unclear.

Objective:

To test the hypothesis that HDL’s cholesterol efflux capacity is impaired in subjects with type 2 diabetes.

Methods and Results:

We performed a case-control study with 19 subjects with type 2 diabetes and 20 control subjects. Three sizes of HDL particles, small-HDL, medium-HDL and large-HDL, were isolated by high-resolution size exclusion chromatography from study subjects. Then we assessed the ABCA1 CEC of equimolar concentrations of particles. Small-HDL accounted for almost all of ABCA1 CEC activity of HDL. ABCA1 CEC—but not ABCG1 CEC—of small-HDL was lower in the subjects with type 2 diabetes than the control subjects. Isotope dilution tandem mass spectrometry demonstrated that the concentration of serpin family A member 1 (SERPINA1) in small-HDL was also lower in subjects with diabetes. Enriching small-HDL with SERPINA1 enhanced ABCA1 CEC. Structural analysis of SERPINA1 identified 3 amphipathic α-helices clustered in the N-terminal domain of the protein; biochemical analyses demonstrated that SERPINA1 binds phospholipid vesicles.

Conclusions:

The ABCA1 CEC of small-HDL is selectively impaired in type 2 diabetes, likely because of lower levels of SERPINA1. SERPINA1 contains a cluster of amphipathic α-helices that enable apolipoproteins to bind phospholipid and promote ABCA1 activity. Thus, impaired ABCA1 activity of small HDL particles deficient in SERPINA1 could increase CVD risk in subjects with diabetes.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus; high-density lipoprotein; ABC transporter; proteomics; Diabetes, Type 2; Lipids and Cholesterol

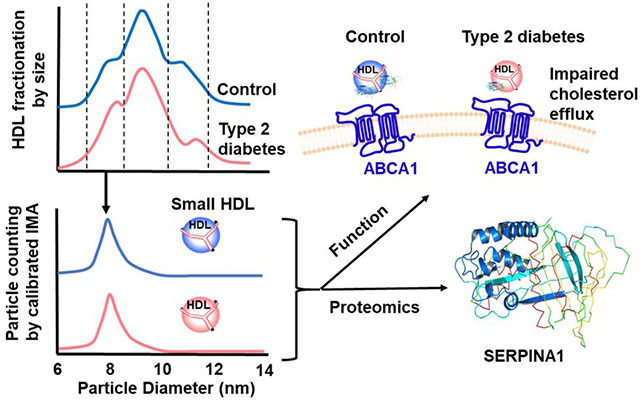

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus is increasing worldwide, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death in that population 1–4. Previous studies have shown that subjects with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus have a two-to-four-fold higher risk of CVD than people without diabetes 2, 5 and, even with statin therapy, their risk remains high 6–7. Also, patients with type 2 diabetes often suffer from diabetic dyslipidemia—elevated levels of plasma triglycerides (TG) and low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) 8–9—which strongly associates with the risk of CVD 10.

A low level of HDL-C strongly and inversely correlates with CVD risk 11–13. However, the failure of HDL-C elevating interventions to lower cardiac events in statin-treated subjects suggests that the association between HDL-C levels and CVD risk may be indirect and that HDL may not play a causal role in cardiovascular disease 14–21. It is therefore critical to identify new HDL metrics that better predict CVD risk and lead to potential therapeutic targets.

Many lines of evidence indicate that one of HDL’s cardioprotective functions is to mediate reverse cholesterol transport from macrophages, a key cellular component of the atherosclerotic lesion 22–26. Two steps in this pathway involve ATP-binding cassette transporters in the cell membrane—ABCA1 and ABCG1—that are highly induced when macrophages accumulate excess cholesterol 27. First, ABCA1 mediates cholesterol efflux from macrophages to lipid-poor apolipoproteins 28 and small dense HDL 29. ABCG1 then transports cellular cholesterol to the more mature lipidated HDL particles generated by ABCA1 30–31. Humans deficient in ABCA1 accumulate cholesterol-loaded macrophages in many different tissues 32; and cholesterol efflux from macrophages is also severely impaired when ABCA1 is deleted 33. Moreover, recent studies demonstrated that the ABCA1-specific cholesterol efflux capacity (ABCA1 CEC) of serum HDL (serum depleted of APOB-containing lipoproteins) inversely associates with both incident and prevalent CVD 34–36. Importantly, that association was independent of HDL-C levels. These results strongly suggest that HDL’s cholesterol efflux capacity is a critical contributor to its anti-atherogenic effects in humans.

The ABCA1 CEC of serum HDL and isolated HDL correlate highly, indicating that altered HDL function is likely a key factor in impaired ABCA1 CEC 37. Biochemical and genetic studies of mice strongly implicate apolipoprotein A1 (APOA1), the main structural protein of HDL, and APOE as key mediators of ABCA1 CEC 38–39. However, the molecular factors that control HDL’s CEC are still not fully understood. Moreover, HDL is a heterogeneous population of particles, with sizes ranging from 7 nm to 14 nm, that collectively contain >80 different proteins 40–41. Du et al. recently used reconstructed HDL and human HDL isolated by ultracentrifugation to demonstrate that small, dense HDLs are the most efficient lipidated mediators of cholesterol efflux by the ABCA1 pathway 29. However, it is still not clear how diabetes affects the function of small HDL.

In the current studies, we tested the hypothesis that HDL’s function is impaired in subjects with type 2 diabetes relative to control subjects without diabetes. We found that ABCA1 CEC was significantly lower in small HDL (S-HDL) of subjects with type 2 diabetes than in that of control subjects. Furthermore, levels of SERPINA1 (serpin family A member 1, also termed α1-antitrypsin [ATT]) was also significantly lower in S-HDL of subjects with type 2 diabetes, and enriching S-HDL with SERPINA1 increased its ABCA1 CEC. Our observations suggest that ABCA1 CEC, the first key step in cholesterol export from macrophages, is impaired in diabetes when S-HDL contains subnormal levels of SERPINA1.

METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Experimental design.

Subjects were selected from the Carotid Lesion Epidemiology and Risk (CLEAR) study 42–43 that was approved by institutional review boards at the University of Washington, Virginia Mason Medical Center, and Veterans Affairs Puget Sound. The CLEAR study is a Seattle-based prevalent carotid artery disease case-control study composed primarily of veterans. All subjects were collected through an Epidemiology Research and Information Center project at the Puget Sound Veterans Affairs Health Care System from 9/20/96 to 10/17/11. Censored age matching was based on the age at the time of the blood draw for controls and the age at the diagnosis of vascular disease for cases. Subjects gave written informed consent. All plasma samples were deidentified, randomized, analyzed in a blinded manner, and contained no information that might allow for the identification of individuals. Exclusion criteria were: total cholesterol >400 mg/dl, known coagulopathy, or unable/willing to consent. All subjects underwent carotid ultrasound and were accepted only if they had <10% carotid stenosis bilaterally. Subjects with atherosclerosis-related diagnoses were excluded. All subjects were on statin therapy. None was on triglyceride-lowering therapy.

Diabetic status was defined as HbA1c level >6.5% or use of insulin or antidiabetic medications. We studied 19 subjects with type 2 diabetes and 20 controls. The two groups were similar in age, gender, and HDL-C, LDL-C, and triglyceride levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study subjects

| Characteristic | Control (n=20) | Diabetic (n=19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61±6 | 63±7 | 0.35 |

| Female/Male (n) | 2/18 | 4/15 | 0.34† |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 50±10 | 46±7 | 0.14 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 110±34 | 99±37 | 0.36 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 118±49 | 130±39 | 0.40 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.5±0.4 | 7.2±1.2 | 4.0×10−6 |

| Total-HDL (µM) | 14.9±0.52 | 13.8±0.4 | 0.13 |

| S-HDL (µM) | 5.2±0.4 | 5.5±0.4 | 0.64 |

| M-HDL (µM) | 7.1±0.5 | 6.3±0.4 | 0.18 |

| L-HDL (µM) | 2.6±0.3 | 2.1±0.2 | 0.17 |

Chi-square test

HDL isolation.

Plasma was quickly thawed at 37°C, and subjected to sequential ultracentrifugation (UC) to isolate HDL (density 1.063–1.210 g/mL) 44. The protein concentration in HDL was measured using the Bradford assay, with albumin as the standard.

Ultracentrifuge-isolated HDL (total-HDL) was separated (0.1 mL/min) by sequential fractionation on two tandem Superdex 200 Increase 5/150 GL columns at 4°C in 150 mM ammonium acetate buffer with an ÄKTA 10 fast protein liquid chromatography system (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA). Fractions containing APOA1 (200 μL) were collected and combined to obtain different sizes of HDL (Fig. I): fractions 12–13 for L-HDL (11.9±0.5 nm, mean ± standard deviation); fractions 14–15 for M-HDL (9.8±0.4 nm); fractions 16–18 for S-HDL (8.1±0.1 nm).

HDL Particle Concentration (HDL-Pima).

The sizes and concentrations of HDL particles were quantified as total HDL (Total-HDL), small HDL (S-HDL), medium HDL (M-HDL), and large HDL (L-HDL) by calibrated ion mobility analysis 45. HDL particles were separated by size in the gas phase and quantified by particle counting. HDL particle counts were converted into aqueous particle concentrations with glucose oxidase calibration curves. The method yields a stoichiometry of APOA1 and sizes and relative abundances of HDL subspecies that are in excellent agreement with those determined by non-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and analytical ultracentrifugation 45–46 .

Cholesterol Efflux Capacity (CEC).

ABCA1 CEC and ABCG1 CEC of isolated HDLs were quantified using BHK (baby hamster kidney) cells with mifepristone-inducible human ABCA1 or ABCG1 28. BHK cells were cultured in DMEM/high glucose media with 4.00 mM L-glutamine (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/mL of penicillin/streptomycin (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA). Cells were radiolabeled by incubation with [H3]cholesterol for 24 h, washed twice, and then incubated for 4 h with 30 pmol of S-HDL, M-HDL, L-HDL, or Total-HDL in 250 μL of medium 47. ABCA1-specific and ABCG1-specific CEC were calculated as the percentage of total [H3]cholesterol (medium plus cell-associated) released into the medium of BHK cells stimulated with mifepristone minus that of cells stimulated with medium alone.

Targeted Protein Quantification by Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM).

Details are provided in the Supplemental Materials.

Incubation of SERPINA1 with S-HDL.

S-HDL was isolated from pooled HDL (five healthy adult subjects), using two tandem Superdex 200 Increase 5/150 GL columns as described above. S-HDL (1.2 mg/mL protein) was incubated with human SERPINA1 at molar ratios of 0.25:1, 0.5:1, and 1:1 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C for 1 h and then re-isolated by ultracentrifugation (density 1.063–1.210 g/mL). SERPINA1 concentrations used during incubation were 0.25-1 mg/mL, which are lower than or close to SERPINA1 levels in human plasma (1-3 mg/mL). About 50% of APOA1 was recovered by ultracentrifugation of the reaction mixture. MS/MS analysis of re-isolated S-HDL and SERPINA1-enriched HDL demonstrated no difference in their relative amounts of APOA1. Furthermore, SERPINA1 levels in SERPINA1-enriched HDL were in the lower range of those of HDL isolated by ultracentrifugation from human plasma. There was no impact of SERPINA1 supplementation on the size of the re-isolated S-HDL as determined by calibration ion mobility analysis (Fig. II).

Identification of Potential Amphipathic α-Helical Sequences with Lipid-Binding Affinity.

The LOCATE algorithm uses termination rules to identify potential amphipathic α-helices in proteins 48–51. WHEEL is a complementary algorithm 48–50 that creates Schiffer-Edmundson helical wheel diagrams 52. WHEEL uses the helical wheel diagram to calculate a parameter of lipid affinity for each sequence, termed Λα 50, which increases with increasing lipid affinity. Both algorithms are based on a minimum of 16 sequential amino acid residues. LOCATE followed by WHEEL was used to identify putative amphipathic α-helical regions in the sequences of SERPINA1 and APOA1.

Phospholipid Binding of SERPINA1.

Phospholipid binding was measured with the biotin capture lipid affinity assay we previously described 53. Briefly, small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were made with 99% POPC (1-palmitoyl,2-oleoyl phosphatidylcholine), 0.5% BT-PE ((biotinyl)-1,2-dipalmitoyl phosphatidylethanolamine), and 0.5% Rhod-PE ((N-lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl)-1,2 dioleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine) (w/w) 53. SUVs (43 µg of phospholipid) were incubated with SERPINA1 in a series of concentrations (0, 10, 25, 50, 100, 150 and 225 µg/mL) in PBS (100 µL) for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were then incubated for 30 min on immobilized streptavidin columns in a 96-well filter plate. The columns were washed 3 times with 100 µL PBS. Bound protein and PL were eluted from the columns, using PBS with 1% sodium cholate (w/v). The eluted PL was quantified by fluorescence (excitation of rhodamine B fluorophor at 550 nm with monitoring emission at 590 nm). Protein was quantified by a 3-(4-carboxybenzoyl)quinoline-2-carboxaldehyde (CBQCA) fluorescence protein assay kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Statistical Analyses.

All statistical analyses were performed with STATA software version 12 (Stata Corp, College Park, TX). Power calculations were based on data from previous analyses and indicated that 15 subjects per group would give 80% power to detect a 15% difference in CEC and 90% power to detect a 30% difference in protein abundance (two-sided α=0.05). To compare groups, we used the chi square test for categorical values and the two-sample t-test for normally distributed continuous variables. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the means of three or more groups. Multivariate linear regression models with an interaction term (diabetic status x lipid component) were used to investigate the association of efflux with each lipid component after controlling for diabetic status. A P value of 0.05 was the threshold for significance. Unless otherwise stated, values represent means ± standard deviations.

For proteomic analyses, differences in HDL-associated protein expression between control subjects and subjects with type 2 diabetes were first calculated by the two-sample t-test. To account for multiple comparisons, P values obtained from the t-test were compared with its Benjamini-Hochberg critical value q, (i/m)Q, where I is the rank, m is the total number of tests, and Q is the false discovery rate (15%) 54–55. Protein levels were considered significantly different when the P value from the t-test was lower than or equal to its q value 54–55.

RESULTS

Study design.

To test the hypothesis that CEC from ABCA1 to HDL particles is impaired in subjects with type 2 diabetes, we performed a case-control study with 39 subjects from the CLEAR study 42–43. Subjects meeting our study criteria (Methods) were randomly selected. The diabetic (n=19) and control (n=20) groups had similar ages and percentages of females (Table 1). Mean hemoglobin A1c levels were 7.2% for the cases and 5.5% for the controls (P=4.0×10−6). The two groups showed no significant differences in HDL-C, LDL-C, or plasma triglyceride levels, or in total-HDL, S-HDL, M-HDL, or L-HDL (Table 1). All the subjects were on statin therapy.

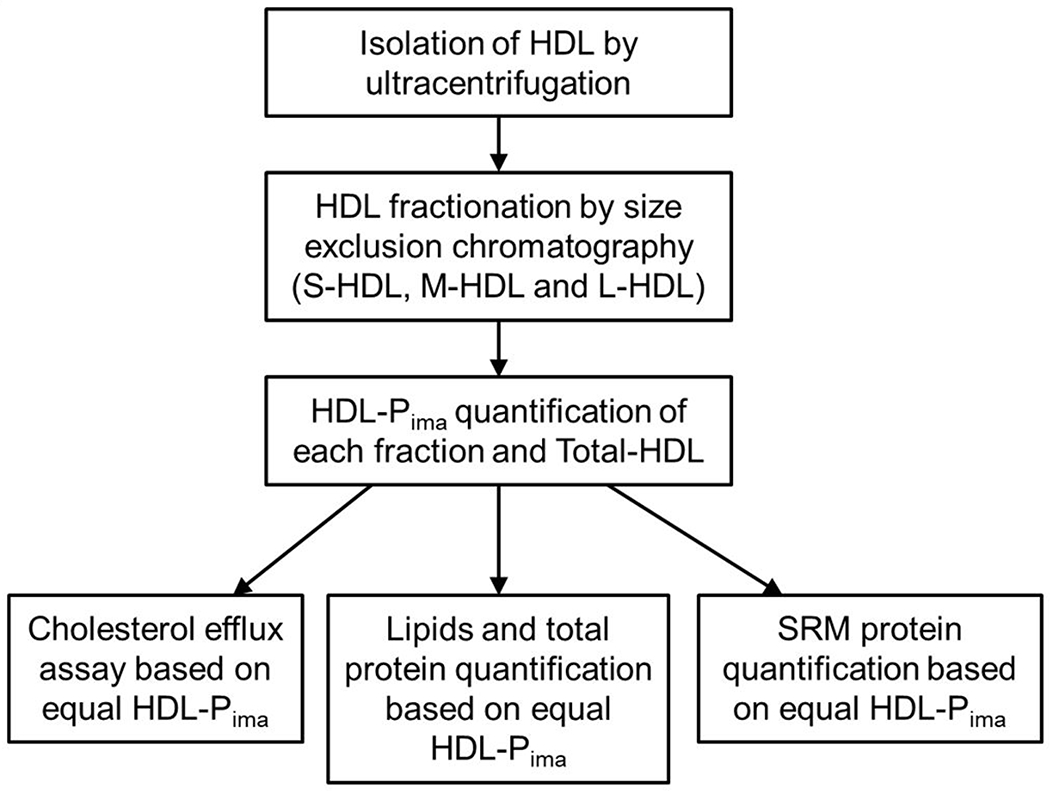

An overview of the study’s workflow is shown in Figure 1. HDL was isolated by ultracentrifugation from freshly thawed plasma (stored at −80 °C after collection), and further separated by high-resolution size exclusion chromatography into three fractions: S-HDL (8.1 nm±0.1nm), M-HDL (9.8±0.4 nm), and L-HDL (11.9±0.5 nm). For each isolated fraction as well as for total-HDL, we used calibrated ion mobility analysis to quantify HDL particle concentration and size (HDL-Pima) 45. Examples of size distributions of S-HDL, M-HDL, and L-HDL are shown in Figure I (Supplemental Material).

Figure 1.

Study design.

All subsequent analyses were performed using the same concentration of HDL particles in each assay. Therefore, the composition (triglycerides, phospholipids, cholesterol, cholesteryl ester and total protein) of the HDL particles as well as CEC and quantitative proteomics were based on equal molar particle concentrations. In the proteomic analyses, we determined relative quantities of 30 proteins that had been consistently detected in HDL in previous studies 40, 56–57 using SRM and isotope dilution with 15N-labeled APOA1 as the internal standard.

Small HDL particles are the major lipidated acceptors of cholesterol from the ABCA1 pathway in both diabetic and control subjects.

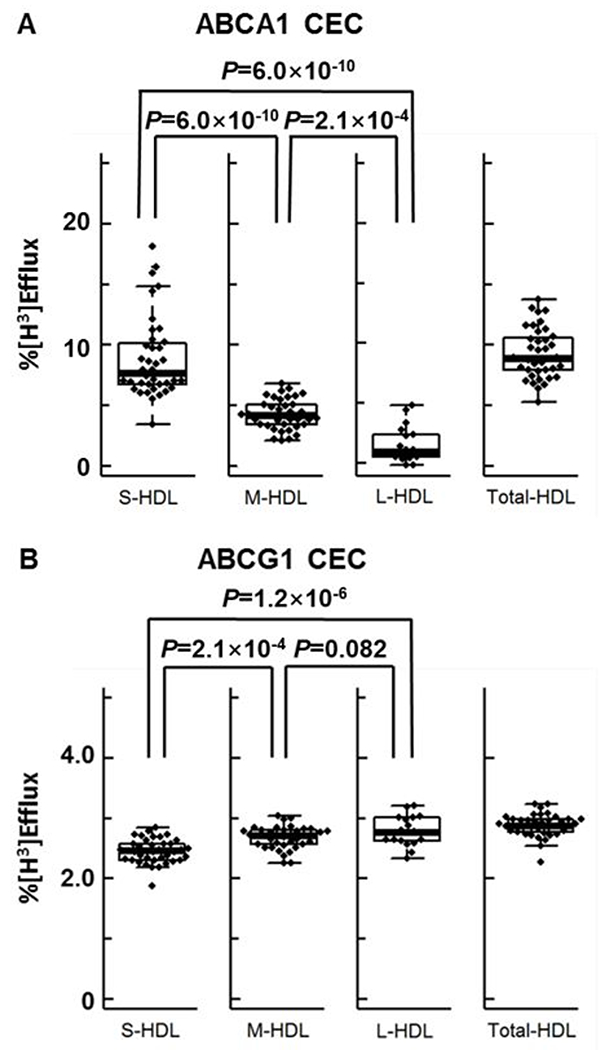

We first tested the capacity of HDL particles of different sizes to promote ABCA1- and ABCG1-specific CEC independently of diabetic status. ABCA1 CEC and ABCG1 CEC were measured using BHK cells with or without expression of mifepristone-inducible human ABCA1 or ABCG1. The cells were exposed to equal concentrations of S-HDL, M-HDL, and L-HDL particles based on HDL-Pima. Regardless of diabetic status, the S-HDL fraction was the major contributor to ABCA1 CEC (Fig. 2A), which was much less efficient with M-HDL and, especially, L-HDL particles. The differences among the ABCA1 CECs of the three sizes of HDL particles were significant after adjustment for diabetic status (P=6×10−10, P=6×10−10 and P=2.1×10−4 from one-way ANOVA, Tukey-Kramer post-test). In contrast, L-HDL and M-HDL particles were the major acceptors of cholesterol from the ABCG1 pathway (Fig. 2B). After adjustment for diabetic status, both M-HDL and L-HDL promoted significantly more efflux through the ABCG1 pathway than did S-HDL (P=2.1×10−4 and P=1.2×10−6, respectively). There was no significant difference between the ability of M-HDL and L-HDL to promote ABCG1 efflux (P=0.082).

Figure 2. ABCA1-mediated and ABCG1-mediated cholesterol efflux capacity (CEC) of different sizes of HDL particles.

Box plots of ABCA1 CEC (A) and ABCG1 CEC (B) for different sizes of HDL particles in the entire study population (n=39 for S-HDL, M-HDL and Total-HDL; n=18 for L-HDL). HDL was isolated by sequential ultracentrifugation and high-resolution size exclusion chromatography. ABCA1 CEC and ABCG1 CEC were measured after a 4-h incubation with HDL (120 nM), using mifepristone-stimulated BHK cells and BHK cells stimulated with medium alone. Efflux was calculated as the % of radiolabeled cholesterol in the medium relative to the total radiolabeled cholesterol content of the medium and cells. CEC is based on equal particle concentrations. The central rectangle of the box plot is the first quartile to the third quartile (interquartile range) range of the data. A segment inside the rectangle shows the median, and “whiskers” above and below the box are the minimum and maximum values. Outliers (●) are values >1.5 times the interquartile range; they were included in the statistical analysis. P value: one-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post-test, controlling for diabetic status.

Small HDL particles from subjects with type 2 diabetes exhibit defective ABCA1 CEC.

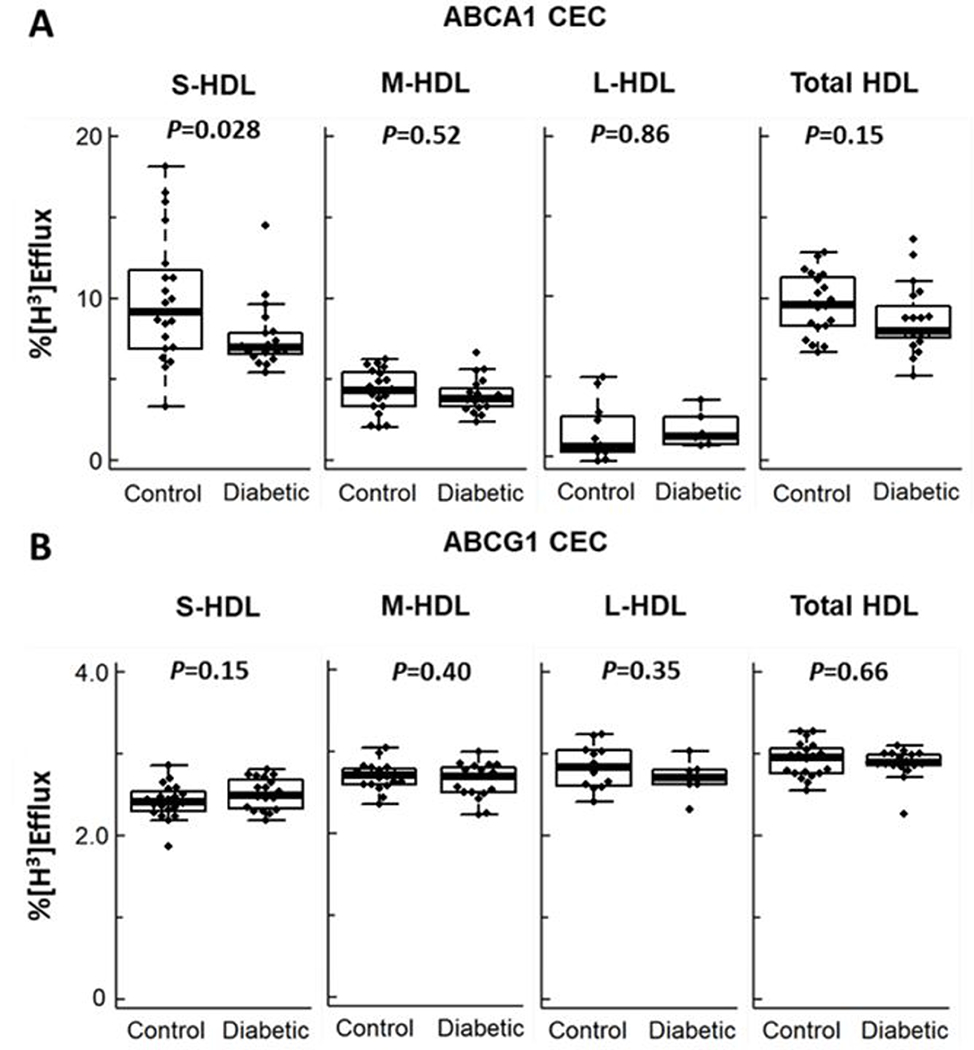

S-HDL particles from subjects with type 2 diabetes were less able to promote efflux through the ABCA1-specific pathway than those of control subjects (Fig. 3A; 7.6 % efflux vs 9.9 % efflux from controls, P=0.028). In contrast, the ABCA1 CEC of the M-HDL and L-HDL particles of the subjects with type 2 diabetes did not differ significantly from that of the controls (Fig. 3A; P=0.52 for M-HDL and 0.86 for L-HDL). Moreover, all three sizes of HDL particles from the subjects with type 2 diabetes had similar ABCG1 CECs when compared with particles from the controls (Fig. 3B). Importantly, there were no significant differences in total HDL particle concentration or S-HDL, M-HDL, or L-HDL particle concentration between control and subjects with type 2 diabetes (Table 1).

Figure 3. Box plots of ABCA1 CEC (A) and ABCG1 CEC (B) for different sizes of HDL particles in subjects with and without diabetes.

All analyses were based on equal particle concentrations (n=20 for control and n=19 for subjects with type 2 diabetes in S-HDL, M-HDL and Total-HDL; n=12 for control and n=6 for subjects with type 2 diabetes in L-HDL). ABCA1 CEC and ABCG1 CEC (mifepristone-stimulated BHK cells minus BHK cells incubated in medium alone) were measured after a 4-h incubation with HDL as indicated in the legend to Fig. 1. P value, two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Diabetic status significantly affects triglyceride levels in S-HDL.

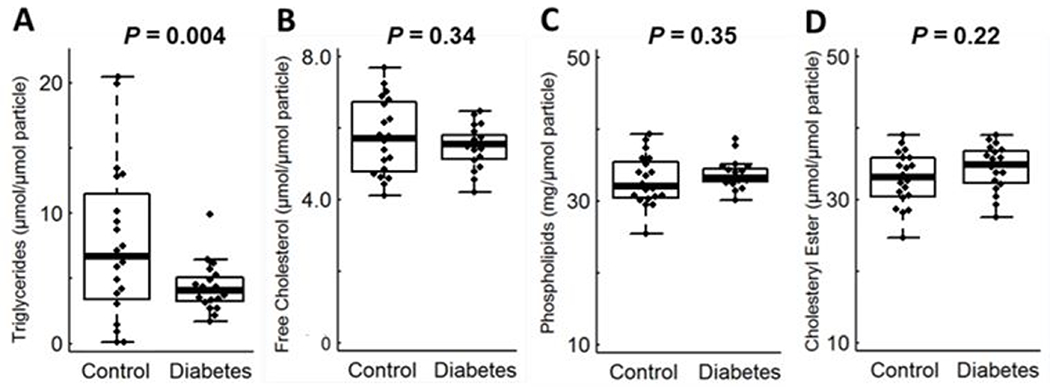

To investigate potential determinants of ABCA1 CEC, we measured the lipid composition of S-HDL in diabetic and control subjects (Fig. 4). All of the lipid levels were normally distributed (P>0.05; Shapiro-Wilk test). Triglyceride levels in S-HDL particles were significantly lower in the subjects with type 2 diabetes than in the controls (P=0.004) (Fig. 4A). However, no significant differences were found for the other lipids: free cholesterol content (Fig. 4B, P=0.34), phospholipids (Fig. 4C, P=0.35), and cholesteryl ester (Fig. 4D, P= 0.22). S-HDLs from the control and subjects with type 2 diabetes contained similar amounts of protein (73.3±12.8 mg/µmol particle in control subjects and 69.3±10.9 mg/µmol particle in subjects with diabetes).

Figure 4. Triglycerides (A), free cholesterol (B), phospholipids (C) and cholesteryl ester (D) of S-HDL particles in subjects with and without diabetes.

The box plots show the distribution of the data (median, interquartile ranges), while the dots represent outliers (n=20 for control and n=19 for subjects with type 2 diabetes). Outliers were included in the statistical analysis.

ERPINA1 and APOC2 levels are altered in diabetic S-HDL, and levels of both proteins correlate with ABCA1 CEC.

To further investigate the mechanism whereby diabetes might impair S-HDL function, we quantified HDL proteins using MS/MS analysis with selected reaction monitoring, a sensitive and precise method for quantitative proteomics analysis in complex biological materials 58–60. We monitored the 30 most abundant HDL proteins. All proteins had been identified previously in at least two different human populations 40, 56–57 (Table I).

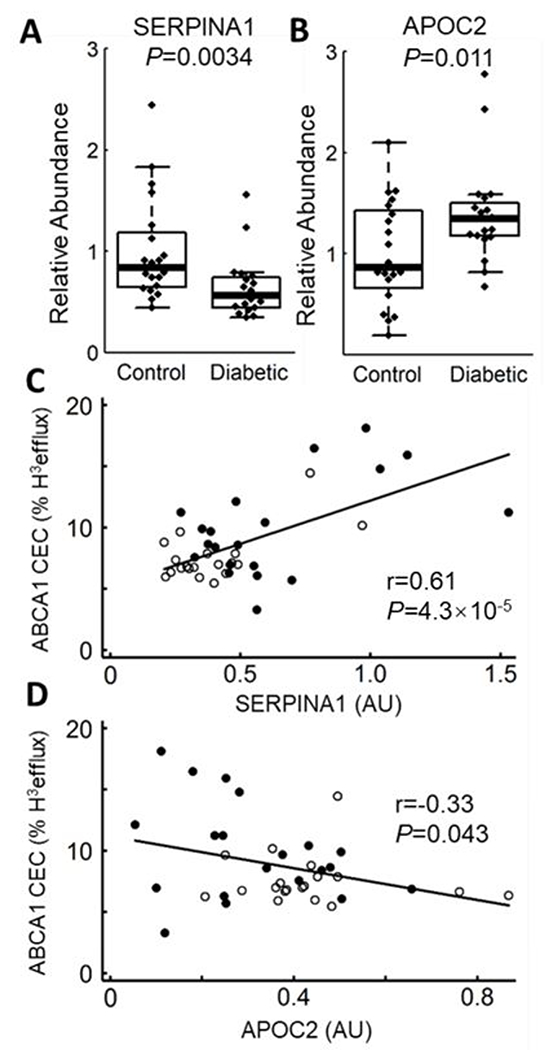

After controlling for multiple comparisons, we found that levels of two proteins—SERPINA1 and APOC2—differed significantly in S-HDL from subjects with type 2 diabetes (Fig. 5). The mean level of SERPINA1 was 35% lower in the subjects with type 2 diabetes than in the control subjects (P=0.0034, Fig. 5A). This deficit was unlikely to be explained by reduced plasma levels of SERPINA1, which did not differ between control and subjects with type 2 diabetes (Fig. IIIA). Moreover, SERPINA1 levels in S-HDL did not correlate with those in plasma (Fig. IIIB), indicating that differences in plasma levels of SERPINA1 did not account for the differences in the SERPINA1 levels in S-HDL of control and subjects with type 2 diabetes. The SERPINA1 level in S-HDL showed a significant positive correlation with ABCA1 CEC (Fig. 5C, r=0.61, P=4×10−5).

Figure 5. Box plots of SERPINA1 (A) and APOC2 (B) in subjects with and without diabetes.

Peptides were quantified by isotope dilution MS/MS as the integrated peak area relative to that of [15N]APOA1 peptide (n=20 for control and n=19 for subjects with type 2 diabetes). P values were calculated from log transformed data. Scatter plots show the correlation of MS/MS analysis and ABCA1-specific efflux for SERPINA1 (C) and APOC2 (D). r represents the Pearson correlation. AU, arbitrary units. ● Control, ○ Diabetic.

In contrast, the mean level of APOC2 was higher in the subjects with type 2 diabetes than in the control subjects (P=0.011, Fig. 5B), while its level in S-HDL correlated negatively with ABCA1 CEC (r=−0.33, P=0.043, Fig. 5D). SERPINA1 levels, but not APOC2 levels, correlated significantly and positively with the triglyceride level in S-HDL (r= 0.40, P=0.011, Fig. IV).

SERPINA1 promotes ABCA1 CEC of small HDL particles.

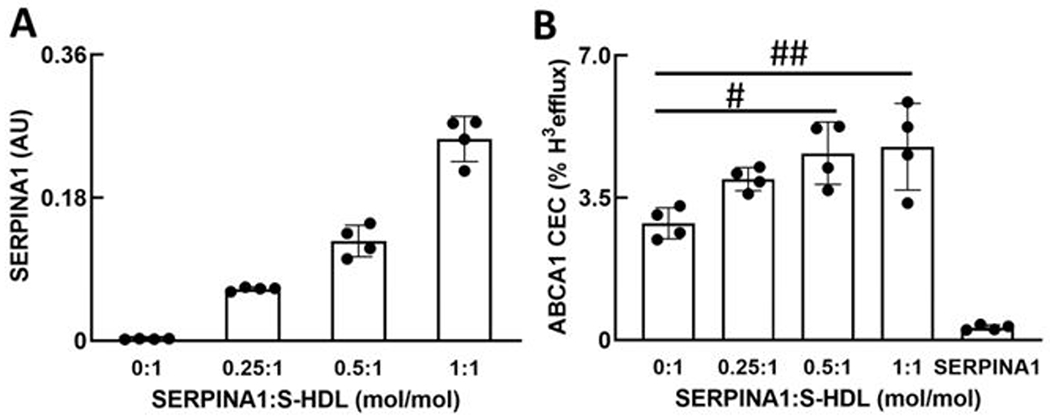

To determine whether SERPINA1 and APOC2 might regulate the ABCA1 CEC of S-HDL particles, we incubated S-HDL isolated by high-resolution size exclusion chromatography with purified SERPINA1 or APOC2 and then re-isolated the lipoproteins by ultracentrifugation. The impact of enriching S-HDL with APOC2 on ABCA1 CEC was variable, perhaps because the apolipoprotein dissociated from S-HDL during ultracentrifugation or displaced APOA1 from S-HDL. In contrast, MS/MS analysis demonstrated that levels of SERPINA1 in re-isolated HDL consistently increased when the lipoprotein was incubated with increasing amounts of the protein (Fig. 6A) without changing the size of the S-HDL particles (Fig. II).

Figure 6. Impact of S-HDL-associated SERPINA1 and free SERPINA1 on ABCA1 CEC.

S-HDL particles were incubated with the indicated concentrations of SERPINA1 (mol/mol particle) for 1 h. HDL was re-isolated by ultracentrifugation, and the relative concentrations of SERPINA1 (A) and ABCA1 CEC (B) were determined by MS/MS analysis and with BHK cells expressing ABCA1 (mifepristone-stimulated BHK cells minus BHK cells incubated in medium alone), respectively. CEC is based on equal particle concentrations. SERPINA1 in panel B represents ABCA1 CEC of lipid-free human SERPINA1 (4 µg/mL). Results are means with standard deviations (n=4, technical replicates) and are representative of those found in 3 independent experiments. AU, arbitrary units. To compare means, 1-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post-test was used in B: #P=0.020, ##P=0.011.

Moreover, enrichment of S-HDL particles with physiological levels of SERPINA1 promoted ABCA1-specific cholesterol efflux from BHK cells. Stimulation was half-maximal at 0.25 mol SERPINA1/mol S-HDL during the incubation; it plateaued at approximately 0.50 mol SERPINA1/mol S-HDL (Fig. 6B). No free APOA1 was detected by immunoblot analysis in the medium of BHK cells incubated with S-HDL or SERPINA1-enriched S-HDL (Fig. V), and the APOA1 contents of the two lipoproteins were indistinguishable by MS/MS analysis, strongly suggesting that SERPINA1 was not displacing APOA1 from HDL.

Biotin labeling followed by MS/MS analysis demonstrated similar levels of ABCA1 protein in plasma membranes isolated from BHK cells exposed to S-HDL or SERPINA1 enriched S-HDL (Fig. VI). S-HDL and SERPINA1-enriched HDL also inhibited TNF-α-stimulated mRNA levels of inflammatory genes ICAM1 and VCAM1 in human endothelial cells to a similar degree (Fig. VII). Collectively, these observations strongly suggest that the increased ABCA1 CEC we found with SERPINA1 enrichment of HDL was not due to altered levels of free or HDL-associated APOA1, increased cell-surface expression of ABCA1 protein, or altered anti-inflammatory properties of S-HDL.

SERPINA1 contains amphipathic α-helices.

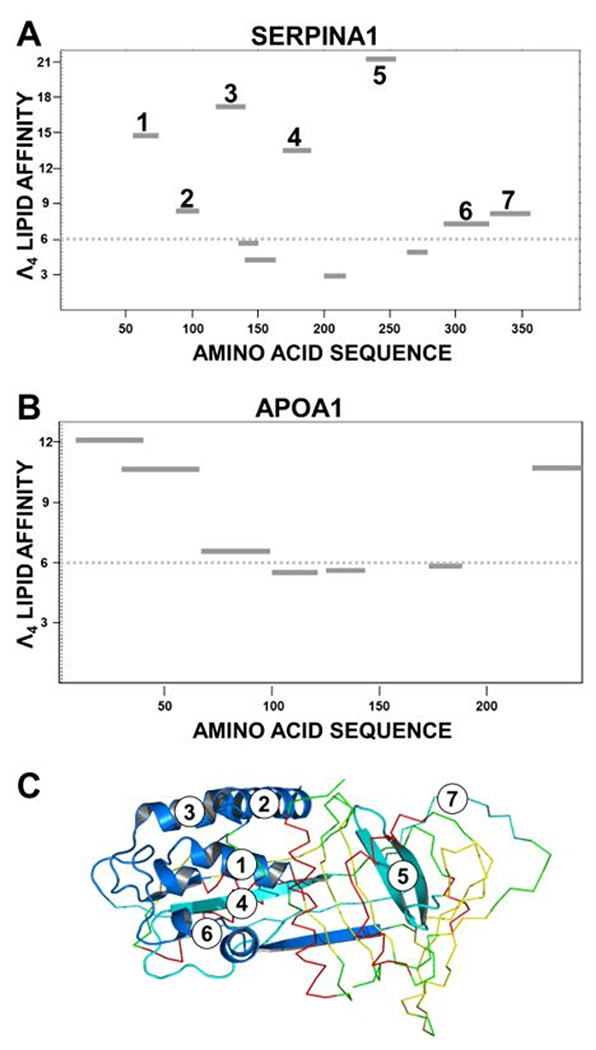

Amphipathic α-helices are key mediators of lipid binding in apolipoproteins and membrane proteins 48, and they play a critical role in modulating the ABCA1 activity of lipid-free APOA1 28. We used the LOCATE and WHEEL algorithms 50 to identify potential amphipathic α-helical lipid-binding domains in SERPINA1. Lipid affinity, termed Λα 50, was calculated for each sequential sequence containing a minimum of 16 amino acids. Based on the analysis of known lipid-binding amphipathic α-helices in apolipoproteins, Λα lipid affinity >6.0 was defined as a potential lipid-binding domain. In SERPINA1, we identified 7 sequences with Λα values >6.0 (Fig. 7A). Analysis of APOA1 (Fig. 7B), which binds phospholipids via α-helical domains in the C- and N-terminal domains 49, 61, identified 4 potential amphipathic α-helical sequences in the C- and N-terminal domains with Λα values >6.0. All of the identified amphipathic α-helical sequences identified in APOA1 are α-helical sequences in the crystal structure of APOA1 49 and are known to mediate phospholipid binding 61.

Figure 7. Potential lipid-binding amphipathic α-helices in SERPINA1 (A) and APOA1 (B) identified with the LOCATE and WHEEL algorithms.

LOCATE uses termination rules to identify potential amphipathic α-helices in proteins 48–50. WHEEL calculates a parameter of lipid affinity for each amino acid sequence (termed Λα) 50. Based on the analysis of known α-helices with lipid-binding affinity 50, sequences with Λα lipid affinity >6.0 (dotted line) were considered potential lipid binding domains. The locations of each putative amphipathic α-helix in the two sequences are denoted by dark lines. (A) Location of α-helical lipid-binding domains in the amino acid sequence of SERPINA1. Seven potential binding domains were identified, each of which is mapped as a single sequence. (B) Location of α-helical lipid-binding domains in the amino acid sequence of APOA1. (C) Crystal structure of SERPINA1. The locations of the seven putative amphipathic helical domains with lipid-binding affinity identified with WHEEL and LOCATE in (A) are mapped in blue in the cartoon. The remainder of the SERPINA1 structure is mapped in CPK colors, using the ribbon format. Four of the putative amphipathic α-helices mapped onto α-helical regions in the crystal structure (1, 2, 3, 6) and 3 of these (1, 2, 3) were clustered at the N-terminus of the protein.

We mapped the locations of the 7 potential lipid-binding domains identified by LOCATE and WHEEL on the crystal structure of SERPINA1 (Fig. 7C). Four were in α-helical domains, and 3 of those were clustered at the N-terminal end of the protein’s globular structure. Taken together, these observations raise the possibility that amphipathic α-helical domains of SERPINA1 mediate lipid binding to HDL.

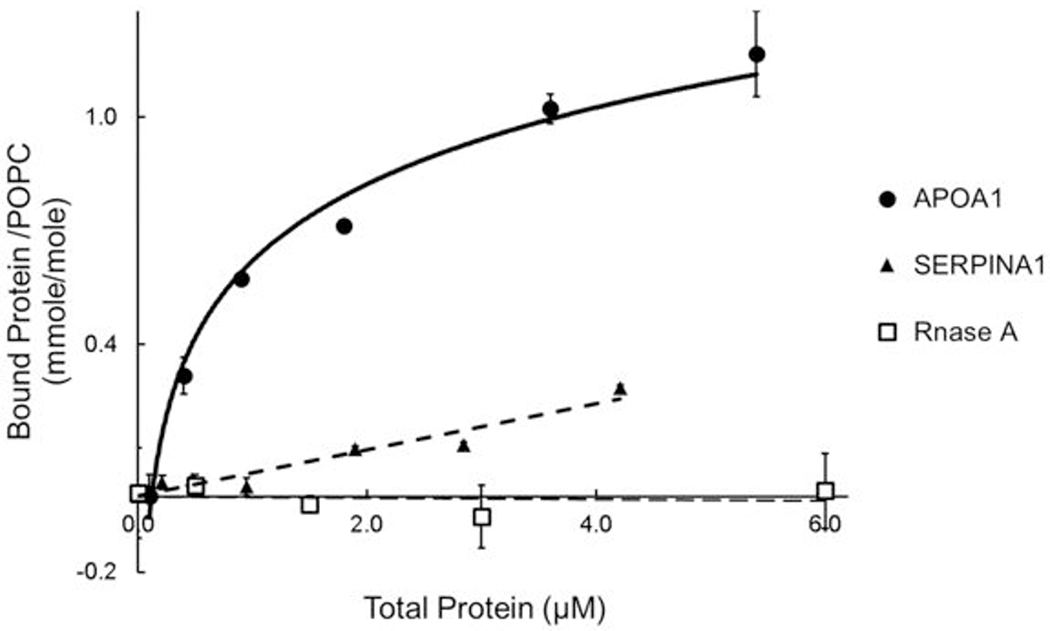

SERPINA1 binds phospholipid vesicles.

We used phospholipid SUVs53 to investigate the lipid-binding properties of lipid-free SERPINA1 (Fig. 8). This approach demonstrated that SERPINA1 binds SUVs. Its apparent binding affinity was ~22% that of APOA1, but it had a much higher apparent maximal binding capacity. In contrast to SERPINA1 and APOA1, Rnase A (which lacks amphipathic α-helical sequences) failed to bind phospholipid SUVs (Fig. 8). These observations demonstrate that SERPINA1 is a phospholipid-binding protein.

Figure 8. Phospholipid-binding profiles of SERPINA1, APOA1, and Rnase.

Lipid-binding of proteins (43 µg) were assessed in 100 μL of PBS for 30 min at 25°C, using SUVs (99% POPC/0.5% BT-PE/0.5% Rhod PE [w/w]). Values are the mean of three independent replicates. Results are representative of two independent experiments. Error bars are ±1 SD.

DISCUSSION

Because pharmacological interventions that raise HDL-C have failed to reduce CVD risk in clinical trials, it is critical to identify new metrics that reflect HDL’s biological roles in humans 11–13, 62–65. One proposed functional metric is ABCA1 CEC, which predicts incident and prevalent CVD in humans independently of HDL-C 34–36. We tested the hypothesis that HDL particles are functionally impaired in subjects with type 2 diabetes, which might contribute to increased CVD risk in these subjects. Except for diabetic status, the clinical characteristics of the control and case subjects we studied were very similar. Importantly, we always compared HDL function on the basis of equimolar concentrations of particles. When HDL concentration is based on other metrics (e.g. protein content), the absolute concentration of the particles can vary widely for the different size classes of HDL.

We found that the ABCA1 CEC of S-HDL was selectively impaired in subjects with type 2 diabetes. The level of impairment (~23%) was much greater than that seen in subjects with prevalent and incident CVD (~9%) 35–36, 66. Because S-HDL particle concentrations were similar in patients with diabetes and controls, these finding suggest a functional impairment of S-HDL in subjects with type 2 diabetes that reduces ABCA1 CEC. In contrast, there was no difference in the ABCG1 CEC of S-HDL, M-HDL, or L-HDL between subjects with and without diabetes.

We also found that S-HDL particles are the major contributors to ABCA1 CEC. These observations raise the possibility that S-HDL particles in patients with diabetes are unable to effectively promote efflux by the ABCA1 pathway, the first key step in reverse cholesterol efflux from macrophages in the artery wall.

These observations confirm and extend the work of Du et al., who demonstrated that small, dense HDLs were the most efficient mediators of cholesterol efflux by the ABCA1 pathway 29. However, that group based its analyses on equal protein concentrations, using reconstituted HDL particles and HDL isolated by ultracentrifugation of plasma from healthy humans. Because the stoichiometry of APOA1 ranges from 2–6 in the different sizes of HDL particles 67, this approach did not allow the investigators to determine the specific activity of each particle size (i.e., ABCA1 CEC based on the molar concentration of the particles) or the contributions of the different sizes of HDL to the CEC of total-HDL.

To determine why small HDL particles are dysfunctional in humans with diabetes, we quantified levels of proteins and lipids in S-HDL. MS/MS analysis showed that levels of SERPINA1 were significantly lower in the S-HDL of the subjects with diabetes. Diabetes associates with lower levels of SERPINA1 in plasma 68–72. In contrast, plasma levels of SERPINA1 were similar in our study of subjects with and without diabetes. Moreover, levels of SERPINA in S-HDL did not correlate with plasma levels of SERPINA1, strongly suggesting that altered levels of plasma SERPINA1 did not account for the differences in SERPINA1 levels we found in S-HDL. Importantly, when we enriched S-HDL with physiological levels of SERPINA1, the ABCA1 CEC of the re-isolated HDL increased, suggesting that SERPINA1 enhances S-HDL’s capacity to promote cholesterol efflux from cells by this pathway and that low levels of SERPINA1 in S-HDL contribute to impaired ABCA1 CEC.

We also found differences in the lipid composition of HDL from subjects with and without diabetes. Triglyceride levels of S-HDL of subjects with diabetes were significantly lower than in control subjects. Levels of SERPINA1 in S-HDL correlated linearly and strongly with the triglyceride content of the particles, suggesting that low triglyceride levels impair the association of SERPINA1 with S-HDL. These observations raise the possibility that lipid composition is another important factor influencing the ABCA1 CEC of S-HDL and that lowering the concentration of triglycerides in HDL particles also might lower SERPINA1 levels.

Because amphipathic α-helices are key mediators of lipid binding in apolipoproteins and membrane proteins, and because they are critical modulators of ABCA1 activity of lipid-free APOA1 28, we searched for evidence that SERPINA1 contains amphipathic α-helices. The LOCATE and WHEEL algorithms identified 7 sequences in SERPINA1 that could be amphipathic α-helices. Four were located in α-helical domains in the crystal structure of SERPINA1, and three of those were clustered at the N terminal end of the globular protein structure, raising the possibility they could be a lipid-binding domain. Biochemical studies with SUVs demonstrated that SERPINA1 is indeed a phospholipid-binding protein. Its apparent binding affinity was ~22% that of APOA1, but it had a much higher apparent maximal binding capacity.

Because apolipoproteins are known to use amphipathic α-helical sequences to associate with lipid and activate ABCA1 28, 48–50, our observations strongly suggest that the amphipathic α-helical regions we identified in SERPINA1 enable to the protein to both bind to lipid in S-HDL and modulate ABCA1 activity. The domain may promote ABCA1 CEC by directly interacting with ABCA1. Alternatively, SERPINA1’s amphipathic α-helical helices could alter APOA1’s ability to bind to lipid, in turn enhancing its ability to interact with ABCA1.

SERPINA1 may play other roles in CVD. Gordon et al. have suggested that both its anti-elastase activity and anti-inflammatory functions are enhanced when it binds to HDL 73. As neutrophil infiltration of culprit coronary lesions is implicated in plaque rupture and thrombus formation in acute myocardial infarction 74, the lower level of SERPINA1 in S-HDL of subjects with diabetes might contribute to the increased risk of morbidity and mortality from myocardial infarction 75 by impairing HDL’s ability to protect tissue from promiscuous proteolysis by serine proteases.

Our study has several limitations. First, the number of subjects was relatively small and the majority were male. It will be important to confirm our results in larger cohorts with more female participants. Second, the size distributions of the isolated HDL subpopulations overlapped to some degree, reflecting the limited resolution of size-exclusion chromatography. Importantly, the mean sizes of S-HDL, M-HDL and L-HDL were well separated. Moreover, there were marked differences in the ABCA1 CEC of the different sizes of HDL particles. These observations strongly support the proposal that the size of HDL has a major impact on both its biological functions and composition 46. Finally, it will be important to carry out additional biochemical and cellular studies to identify the functional domains and mechanisms that enable SERPINA1 to enhance ABCA1 CEC in HDL.

In conclusion, we found that the ABCA1 CEC and SERPINA1 of S-HDL were selectively impaired in subjects with diabetes. In contrast, enrichment of S-HDL particles with SERPINA1 increased ABCA1 CEC. Structural and biochemical studies supported the proposal that SERPINA1 contains amphipathic α-helical regions and is a phospholipid-binding protein, suggesting that SEPINA1 binds to HDL phospholipids, altering the lipoprotein’s ABCA1 activity. Thus, the S-HDL produced during diabetes could be unable to remove adequate amounts of cholesterol from the artery wall due to its decreased SERPINA1 content, placing patients at higher risk for CVD.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Patients with type 2 diabetes often have low levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than non-diabetic patients.

One of HDL’s important cardioprotective functions is likely its cholesterol efflux capacity—the ability to remove cholesterol from macrophage foam cells.

HDL is a heterogeneous population of particles that vary widely in size and molecular composition.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Small HDL particles are the primary mediators of cholesterol efflux that involves the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1).

Small HDL particles in patients with type 2 diabetes have impaired cholesterol efflux capacity and contain subnormal amounts of serpin family A member 1 (SERPINA1).

Reconstituting small HDL with SERPINA1 improves cholesterol efflux capacity.

SERPINA1 binds phospholipids. Three putative amphipathic α-helical domains in the N-terminus of SERPINA1 likely mediate this binding.

Selective impairment of small HDL’s cholesterol efflux capacity may contribute to increased CVD risk in patients with type 2 diabetes.

HDL may help protect against CVD because it accepts the cholesterol that is removed from arterial wall macrophages by ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCA1). Type 2 diabetes greatly increases the risk of CVD, but its impact on cholesterol efflux by ABCA1 is poorly understood. We isolated HDL from control subjects and subjects with type 2 diabetes and fractionated the particles into three size classes. We found that small HDL was the major contributor to ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux from cells. Moreover, the efflux capacity of small HDL particles was selectively impaired in the patients with type 2 diabetes. Using quantitative proteomics, we showed that those patients had lower SERPINA1 levels in their small HDL particles. Enrichment of small HDL with SERPINA1 markedly improved cholesterol efflux capacity. Structural studies demonstrated that SERPINA1 contains multiple putative amphipathic α-helical domains in its N-terminus that likely mediate its ability to bind to phospholipids and promote cholesterol efflux. Our findings suggest that type 2 diabetes might increase CVD risk by depleting small HDL of SERPINA1, thereby impairing its ability to remove artery wall cholesterol.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Michael Oda (Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute) for providing isotope-labeled APOA1 and Dr. Priska D. von Haller (University of Washington) for technical assistance and helpful discussions. Mass spectrometry experiments were supported by the Diabetes Research Center (P30DK17047) and the University of Washington’s Proteomics Resource (UWPR95794).

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health (R01HL112625, R01HL108897, P01HL092969, DP3DK108209, R01HL149685, T32HL007828, P01HL076491, P01HL128203), the American Heart Association (15POST22700033) and the Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP 2016/00696-3).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- ABCA1

ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

- ABCG1

ATP-binding cassette transporter G1

- BHK

baby hamster kidney

- CEC

cholesterol efflux capacity

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- FC

free cholesterol

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-P

HDL particle concentration

- HDL-Pima

HDL-P concentration determined by calibrated ion mobility analysis

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- L-HDL

large HDL

- M-HDL

medium HDL

- MS

mass spectrometry

- PL

phospholipid

- rHDL

reconstructed HDL particles

- S-HDL

small HDL

- SRM

selected reaction monitoring

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics−-2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014; 129: 399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haffner SM. Dyslipidemia management in adults with diabetes. Diabetes care. 2004; 27 Suppl 1: S68–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD,Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes care. 1993; 16: 434–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R,King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes care. 2004; 27: 1047–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orchard TJ,Costacou T. When are type 1 diabetic patients at risk for cardiovascular disease? Curr Diab Rep. 2010; 10: 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, Hitman GA, Neil HA, Livingstone SJ, Thomason MJ, Mackness MI, Charlton-Menys V,Fuller JH. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004; 364: 685–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins R, Armitage J, Parish S, Sleigh P,Peto R. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003; 361: 2005–2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manzato E, Zambon A, Lapolla A, Zambon S, Braghetto L, Crepaldi G,Fedele D. Lipoprotein abnormalities in well-treated type II diabetic patients. Diabetes care. 1993; 16: 469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taskinen MR. Diabetic dyslipidaemia: from basic research to clinical practice. Diabetologia. 2003; 46: 733–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman MJ, Ginsberg HN, Amarenco P et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease: evidence and guidance for management. European heart journal. 2011; 32: 1345–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon DJ,Rifkind BM. High-density lipoprotein--the clinical implications of recent studies. The New England journal of medicine. 1989; 321: 1311–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahdy Ali K, Wonnerth A, Huber K,Wojta J. Cardiovascular disease risk reduction by raising HDL cholesterol--current therapies and future opportunities. Br J Pharmacol. 2012; 167: 1177–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson PW, Abbott RD,Castelli WP. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality. The Framingham Heart Study. Arteriosclerosis. 1988; 8: 737–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rader DJ,Hovingh GK. HDL and cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2014; 384: 618–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mank-Seymour AR, Durham KL, Thompson JF, Seymour AB,Milos PM. Association between single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the endothelial lipase (LIPG) gene and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004; 1636: 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanoni P, Khetarpal SA, Larach DB et al. Rare variant in scavenger receptor BI raises HDL cholesterol and increases risk of coronary heart disease. Science. 2016; 351: 1166–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M et al. Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2012; 367: 2089–2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Investigators A- H, Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, Chaitman BR, Desvignes-Nickens P, Koprowicz K, McBride R, Teo K,Weintraub W. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. The New England journal of medicine. 2011; 365: 2255–2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M et al. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. The New England journal of medicine. 2007; 357: 2109–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nissen SE, Tardif JC, Nicholls SJ, Revkin JH, Shear CL, Duggan WT, Ruzyllo W, Bachinsky WB, Lasala GP, Tuzcu EM,Investigators I. Effect of torcetrapib on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2007; 356: 1304–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Group HTRC, Bowman L, Hopewell JC, Chen F, Wallendszus K, Stevens W, Collins R, Wiviott SD, Cannon CP, Braunwald E, Sammons E,Landray MJ. Effects of Anacetrapib in Patients with Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2017; 377: 1217–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kontush A,Chapman MJ, High-Density Lipoproteins: Structure, Metabolism, Function, and Therapeutics. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rader DJ, Alexander ET, Weibel GL, Billheimer J,Rothblat GH. The role of reverse cholesterol transport in animals and humans and relationship to atherosclerosis. Journal of lipid research. 2009; 50 Suppl: S189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy AJ,Tall AR. Proliferating macrophages populate established atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation research. 2014; 114: 236–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klancic T, Woodward L, Hofmann SM,Fisher EA. High density lipoprotein and metabolic disease: Potential benefits of restoring its functional properties. Mol Metab. 2016; 5: 321–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Favari E, Thomas MJ,Sorci-Thomas MG. High-Density Lipoprotein Functionality as a New Pharmacological Target on Cardiovascular Disease: Unifying Mechanism That Explains High-Density Lipoprotein Protection Toward the Progression of Atherosclerosis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2018; 71: 325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rye KA,Barter PJ. Regulation of high-density lipoprotein metabolism. Circulation research. 2014; 114: 143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oram JF,Heinecke JW. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1: a cell cholesterol exporter that protects against cardiovascular disease. Physiological reviews. 2005; 85: 1343–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du XM, Kim MJ, Hou L et al. HDL particle size is a critical determinant of ABCA1-mediated macrophage cellular cholesterol export. Circulation research. 2015; 116: 1133–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennedy MA, Barrera GC, Nakamura K, Baldan A, Tarr P, Fishbein MC, Frank J, Francone OL,Edwards PA. ABCG1 has a critical role in mediating cholesterol efflux to HDL and preventing cellular lipid accumulation. Cell metabolism. 2005; 1: 121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yvan-Charvet L, Wang N,Tall AR. Role of HDL, ABCA1, and ABCG1 transporters in cholesterol efflux and immune responses. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2010; 30: 139–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrans VJ,Fredrickson DS. The pathology of Tangier disease. A light and electron microscopic study. The American journal of pathology. 1975; 78: 101–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Out R, Jessup W, Le Goff W, Hoekstra M, Gelissen IC, Zhao Y, Kritharides L, Chimini G, Kuiper J, Chapman MJ, Huby T, Van Berkel TJ,Van Eck M. Coexistence of foam cells and hypocholesterolemia in mice lacking the ABC transporters A1 and G1. Circulation research. 2008; 102: 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ridker PM. The JUPITER trial: results, controversies, and implications for prevention. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2009; 2: 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohatgi A, Khera A, Berry JD, Givens EG, Ayers CR, Wedin KE, Neeland IJ, Yuhanna IS, Rader DR, de Lemos JA,Shaul PW. HDL cholesterol efflux capacity and incident cardiovascular events. The New England journal of medicine. 2014; 371: 2383–2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saleheen D, Scott R, Javad S et al. Association of HDL cholesterol efflux capacity with incident coronary heart disease events: a prospective case-control study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015; 3: 507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monette JS, Hutchins PM, Ronsein GE, Wimberger J, Irwin AD, Tang C, Sara JD, Shao B, Vaisar T, Lerman A,Heinecke JW. Patients With Coronary Endothelial Dysfunction Have Impaired Cholesterol Efflux Capacity and Reduced HDL Particle Concentration. Circulation research. 2016; 119: 83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pamir N, Hutchins P, Ronsein G, Vaisar T, Reardon CA, Getz GS, Lusis AJ,Heinecke JW. Proteomic analysis of HDL from inbred mouse strains implicates APOE associated with HDL in reduced cholesterol efflux capacity via the ABCA1 pathway. Journal of lipid research. 2016; 57: 246–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pamir N, Hutchins PM, Ronsein GE et al. Plasminogen promotes cholesterol efflux by the ABCA1 pathway. JCI Insight. 2017; 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaisar T, Pennathur S, Green PS et al. Shotgun proteomics implicates protease inhibition and complement activation in the antiinflammatory properties of HDL. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007; 117: 746–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah AS, Tan L, Long JL,Davidson WS. Proteomic diversity of high density lipoproteins: our emerging understanding of its importance in lipid transport and beyond. Journal of lipid research. 2013; 54: 2575–2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarvik GP, Hatsukami TS, Carlson C, Richter RJ, Jampsa R, Brophy VH, Margolin S, Rieder M, Nickerson D, Schellenberg GD, Heagerty PJ,Furlong CE. Paraoxonase activity, but not haplotype utilizing the linkage disequilibrium structure, predicts vascular disease. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2003; 23: 1465–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jarvik GP, Rozek LS, Brophy VH, Hatsukami TS, Richter RJ, Schellenberg GD,Furlong CE. Paraoxonase (PON1) phenotype is a better predictor of vascular disease than is PON1 (192) or PON1(55) genotype. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2000; 20: 2441–2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mendez AJ, Oram JF,Bierman EL. Protein kinase C as a mediator of high density lipoprotein receptor-dependent efflux of intracellular cholesterol. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991; 266: 10104–10111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hutchins PM, Ronsein GE, Monette JS, Pamir N, Wimberger J, He Y, Anantharamaiah GM, Kim DS, Ranchalis JE, Jarvik GP, Vaisar T,Heinecke JW. Quantification of HDL particle concentration by calibrated ion mobility analysis. Clinical chemistry. 2014; 60: 1393–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenson RS, Brewer HB Jr., Chapman MJ, Fazio S, Hussain MM, Kontush A, Krauss RM, Otvos JD, Remaley AT,Schaefer EJ. HDL measures, particle heterogeneity, proposed nomenclature, and relation to atherosclerotic cardiovascular events. Clinical chemistry. 2011; 57: 392–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shao B, Fu X, McDonald TO, Green PS, Uchida K, O’Brien KD, Oram JF,Heinecke JW. Acrolein impairs ATP binding cassette transporter A1-dependent cholesterol export from cells through site-specific modification of apolipoprotein A-I. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005; 280: 36386–36396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segrest JP, De Loof H, Dohlman JG, Brouillette CG,Anantharamaiah GM. Amphipathic helix motif: classes and properties. Proteins. 1990; 8: 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Segrest JP, Jones MK, Klon AE, Sheldahl CJ, Hellinger M, De Loof H,Harvey SC. A detailed molecular belt model for apolipoprotein A-I in discoidal high density lipoprotein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999; 274: 31755–31758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Segrest JP, Jones MK, Mishra VK,Anantharamaiah GM, Experimental and computational studies of the interactions of amphipathic peptides with lipid surfaces. In Peptide-Lipid Interactions, 2002; pp 397–435. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Segrest JP, Jones MK, Mishra VK, Anantharamaiah GM,Garber DW. apoB-100 has a pentapartite structure composed of three amphipathic alpha-helical domains alternating with two amphipathic beta-strand domains. Detection by the computer program LOCATE. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994; 14: 1674–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schiffer M,Edmundson AB. Use of helical wheels to represent the structures of proteins and to identify segments with helical potential. Biophys J. 1967; 7: 121–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davidson WS, Ghering AB, Beish L, Tubb MR, Hui DY,Pearson K. The biotin-capture lipid affinity assay: a rapid method for determining lipid binding parameters for apolipoproteins. Journal of lipid research. 2006; 47: 440–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benjamini Y,Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995; 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benjamini Y,Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann Stat. 2001; 29: 1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gordon SM, Deng J, Tomann AB, Shah AS, Lu LJ,Davidson WS. Multi-dimensional co-separation analysis reveals protein-protein interactions defining plasma lipoprotein subspecies. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2013; 12: 3123–3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ronsein GE, Pamir N, von Haller PD, Kim DS, Oda MN, Jarvik GP, Vaisar T,Heinecke JW. Parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) and selected reaction monitoring (SRM) exhibit comparable linearity, dynamic range and precision for targeted quantitative HDL proteomics. Journal of proteomics. 2015; 113: 388–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Picotti P,Aebersold R. Selected reaction monitoring-based proteomics: workflows, potential, pitfalls and future directions. Nature methods. 2012; 9: 555–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Addona TA, Abbatiello SE, Schilling B et al. Multi-site assessment of the precision and reproducibility of multiple reaction monitoring-based measurements of proteins in plasma. Nature biotechnology. 2009; 27: 633–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gillette MA,Carr SA. Quantitative analysis of peptides and proteins in biomedicine by targeted mass spectrometry. Nature methods. 2013; 10: 28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mishra VK, Palgunachari MN, Datta G, Phillips MC, Lund-Katz S, Adeyeye SO, Segrest JP,Anantharamaiah GM. Studies of synthetic peptides of human apolipoprotein A-I containing tandem amphipathic alpha-helixes. Biochemistry. 1998; 37: 10313–10324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Joyce CW, Amar MJ, Lambert G, Vaisman BL, Paigen B, Najib-Fruchart J, Hoyt RF Jr., Neufeld ED, Remaley AT, Fredrickson DS, Brewer HB Jr.,Santamarina-Fojo S. The ATP binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) modulates the development of aortic atherosclerosis in C57BL/6 and apoE-knockout mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002; 99: 407–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singaraja RR, Fievet C, Castro G, James ER, Hennuyer N, Clee SM, Bissada N, Choy JC, Fruchart JC, McManus BM, Staels B,Hayden MR. Increased ABCA1 activity protects against atherosclerosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2002; 110: 35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yvan-Charvet L, Ranalletta M, Wang N, Han S, Terasaka N, Li R, Welch C,Tall AR. Combined deficiency of ABCA1 and ABCG1 promotes foam cell accumulation and accelerates atherosclerosis in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007; 117: 3900–3908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tall AR,Rader DJ. Trials and Tribulations of CETP Inhibitors. Circulation research. 2018; 122: 106–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ebtehaj S, Gruppen EG, Bakker SJL, Dullaart RPF,Tietge UJF. HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein) Cholesterol Efflux Capacity Is Associated With Incident Cardiovascular Disease in the General Population. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2019; 39: 1874–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang R, Silva RA, Jerome WG, Kontush A, Chapman MJ, Curtiss LK, Hodges TJ,Davidson WS. Apolipoprotein A-I structural organization in high-density lipoproteins isolated from human plasma. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2011; 18: 416–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sandler M, Gemperli BM, Hanekom C,Kuhn SH. Serum alpha 1-protease inhibitor in diabetes mellitus: reduced concentration and impaired activity. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 1988; 5: 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lisowska-Myjak B, Pachecka J, Kaczynska B, Miszkurka G,Kadziela K. Serum protease inhibitor concentrations and total antitrypsin activity in diabetic and non-diabetic children during adolescence. Acta diabetologica. 2006; 43: 88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hashemi M, Naderi M, Rashidi H,Ghavami S. Impaired activity of serum alpha-1-antitrypsin in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2007; 75: 246–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bristow CL, Di Meo F,Arnold RR. Specific activity of alpha1proteinase inhibitor and alpha2macroglobulin in human serum: application to insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Clinical immunology and immunopathology. 1998; 89: 247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sandstrom CS, Ohlsson B, Melander O, Westin U, Mahadeva R,Janciauskiene S. An association between Type 2 diabetes and alpha-antitrypsin deficiency. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2008; 25: 1370–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gordon SM, McKenzie B, Kemeh G, Sampson M, Perl S, Young NS, Fessler MB,Remaley AT. Rosuvastatin Alters the Proteome of High Density Lipoproteins: Generation of alpha-1-antitrypsin Enriched Particles with Anti-inflammatory Properties. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2015; 14: 3247–3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Naruko T, Ueda M, Haze K et al. Neutrophil infiltration of culprit lesions in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2002; 106: 2894–2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malmberg K, Norhammar A, Wedel H,Ryden L. Glycometabolic state at admission: important risk marker of mortality in conventionally treated patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction: long-term results from the Diabetes and Insulin-Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction (DIGAMI) study. Circulation. 1999; 99: 2626–2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ronsein GE, Reyes-Soffer G, He Y, Oda M, Ginsberg H,Heinecke JW. Targeted Proteomics Identifies Paraoxonase/Arylesterase 1 (PON1) and Apolipoprotein Cs as Potential Risk Factors for Hypoalphalipoproteinemia in Diabetic Subjects Treated with Fenofibrate and Rosiglitazone. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2016; 15: 1083–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoofnagle AN, Becker JO, Oda MN, Cavigiolio G, Mayer P,Vaisar T. Multiple-reaction monitoring-mass spectrometric assays can accurately measure the relative protein abundance in complex mixtures. Clinical chemistry. 2012; 58: 777–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.MacLean B, Tomazela DM, Shulman N, Chambers M, Finney GL, Frewen B, Kern R, Tabb DL, Liebler DC,MacCoss MJ. Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics. 2010; 26: 966–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shah AS, Tan L, Long JL,Davidson WS. Proteomic diversity of high density lipoproteins: our emerging understanding of its importance in lipid transport and beyond. Journal of lipid research. 2013; 54: 2575–2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vaisar T, Pennathur S, Green PS et al. Shotgun proteomics implicates protease inhibition and complement activation in the antiinflammatory properties of HDL. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007; 117: 746–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gordon SM, Deng J, Tomann AB, Shah AS, Lu LJ,Davidson WS. Multi-dimensional co-separation analysis reveals protein-protein interactions defining plasma lipoprotein subspecies. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2013; 12: 3123–3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Benjamini Y,Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995; 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Benjamini Y,Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann Stat. 2001; 29: 1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cavigiolio G, Shao B, Geier EG, Ren G, Heinecke JW,Oda MN. The interplay between size, morphology, stability, and functionality of high-density lipoprotein subclasses. Biochemistry. 2008; 47: 4770–4779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eng JK, Fischer B, Grossmann J,MacCoss MJ. A Fast SEQUEST Cross Correlation Algorithm. Journal of Proteome Research. 2008; 7: 4598–4602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Subramaniyam D, Virtala R, Pawlowski K, Clausen IG, Warkentin S, Stevens T,Janciauskiene S. TNF-alpha-induced self expression in human lung endothelial cells is inhibited by native and oxidized alpha1-antitrypsin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008; 40: 258–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.