Abstract

Background

Duplication 15q syndrome (Dup15q) is a rare neurogenetic disorder characterized by autism and pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Most individuals with isodicentric (idic15) have been on multiple medications to control seizures. We recently developed a model of Dup15q in Drosophila by elevating levels of fly Dube3a in glial cells using repo-GAL4, not neurons. Unlike other Dup15q models, these flies develop seizures that worsen with age.

Methods

We screened repo>Dube3a flies for approved compounds which can suppress seizures. 3–5 day old flies were exposed to compounds in the fly food during development. Flies were tested using a bang sensitivity assay for seizure recovery time. At least 40 animals were tested per experiment, with separate testing for males and females. Studies of K+ content in glial cells of the fly brain were also performed using a florescent K+ indicator.

Results

We identified 17 out of 1280 compounds in the Prestwick Chemical Library could suppress seizures. Eight compounds were validated in secondary screening. Four of these compounds regulated either serotoninergic or dopaminergic signaling and subsequent experiments confirmed that seizure suppression occurs primarily through stimulation of serotonin receptor 5-HT1A. Additional studies of K+ levels showed that Dube3a regulation of the Na+/K+ exchanger ATPα in glia may be modulated by serotonin/dopamine signaling, causing seizure suppression.

Conclusions

Based on these pharmacological and genetic studies, we present an argument for the use of 5-HT1A agonists in the treatment of Dup15q epilepsy.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Dup15q, Seizures, Drosophila melanogaster, Prestwick Chemical Library, Serotonin, Dopamine

Introduction

Chromosomal deletions and duplications of the 15q11.2-q13.1 region cause serious developmental disabilities in humans, including Angelman syndrome (AS), Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) and a common genetic abnormality leading to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and intellectual disability (ID), Duplication 15q syndrome (Dup15q) (1). A recent study showed that children with isodicentric duplications (idic15) and epilepsy also had the greatest degree of ID in this cohort (2). Multiple lines of evidence from both human genetic studies and experimental models suggest a tight regulation of UBE3A expression in the mammalian brain including maternal allele specific expression of UBE3A (3–5). Most studies focus on UBE3A expression in neurons, since UBE3A is expressed exclusively from the maternal allele in mammalian neurons (4, 6–11). However, UBE3A is not imprinted in either neurons of the sub-ventricular zone (neural stem cells) (3), the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus (12) or in glial cells (4, 13–15). In AS, loss of the maternal UBE3A allele through deletions, mutations of maternal UBE3A or paternal uniparental disomy all result in an AS phenotype (16). While evidence suggests that maternal, but not paternal, duplications of 15q result in ASD phenotypes, implicating the maternal expression of UBE3A in neurons (17, 18), there is still no definitive proof from murine models that this is the case (19). Furthermore, multiple studies focused on maternal expression of Ube3a in mouse neurons have failed to recapitulate the characteristic severe pharmacoresistant epilepsy phenotype shared by most isodicentric Dup15q individuals (19–22).

A common coincident phenotype in ASD is an increased incidence of epileptic seizures (23–25). Although the most prominent features of Dup15q syndrome are ASD, ID and behavioral abnormalities, most individuals with idic15 also suffer from difficult to control seizures (pharmacoresistant) (1, 26). Typically individuals with idic15 have been on several medications to control their seizures and some individuals continue to suffer from epilepsy despite a variety of anti-epileptic drugs available. Parent reporting indicates that these pharmacoresistant seizures are the most difficult issue to address in the Dup15q population (26).

We recently developed a model of Dup15q syndrome in Drosophila melanogaster which recapitulates the seizure phenotype seen in humans (27). We showed that glial expression, but not neuronal expression, of Dube3a (the fly UBE3A orthologue) results in a robust and reproducible seizure phenotype in flies (27). Although there are several mouse models of Dup15q syndrome which elevate Ube3a levels in neurons, none of these mice show a spontaneous or easily inducible seizure phenotype like our Drosophila model. Flies expressing Dube3a or human UBE3A in glial cells will seize after vortexing, at elevated temperatures or even through optical stimulation using a strobe light (27).

Studies in both murine models and human brain indicate that the UBE3A gene escapes allele specific expression in glial cells. Early studies of imprinting in cultured neurons or glia from Ube3a maternal allele deficient mice indicated that not only is Ube3a expressed from the paternal allele in cultured glia, but that the Ube3a antisense transcript, which regulates Ube3a expression on the paternal allele, could not be detected in cultured glia from Ube3aM’/P+ animals (15). Additional studies in mice showed that Ube3a escapes allele specific regulation in GFAP+ glial cells and oligodendrocytes of the brain (13, 28). Studies utilizing a Ube3a-YFP knock in construct further validated the observation that Ube3a is bi-allelically expressed in glial cells (29). Recently, a study using human brain samples confirmed at the protein level that UBE3A is present in GFAP+ glial cells of the human brain (28).

Given the body of evidence supporting biallelic expression of UBE3A in glia and the hypothesis that biallelically expressed UBE3A in glial cells should be elevated in idic15 individuals who have 4 or more copies of UBE3A, we used our fly model to screen for drugs that can suppress seizures that initiate in glia. We exploited a 30 second window of paralysis observed in flies expressing Dube3a in glial cells to find to identify previously approved drugs that can be repurposed to treat seizures in humans with Dup15q.

Methods and Materials

Complete detailed methods can be found online (Supplemental).

Fly Husbandry and Drug Screening

Flies were maintained at 25°C on a 12-hour light/dark cycle and raised on standard corn meal media. A complete list of stocks used can be found in Table S1. Compounds were dissolved in DMSO at a final concentration of 1pM in the food for primary screening. The bang sensitivity assay (BSA) was performed as previously described (30–32). Flies were allowed to eclose and aged for three days prior to testing. The primary screen was conducted as in Fig. 1, while the secondary validation required ice anesthetizing animals briefly prior to the BSA. Total recovery time, defined by the time it took the fly to right itself and walk freely, was measured in seconds. At least 40 animals were tested for each drug in the secondary screen (males and females).

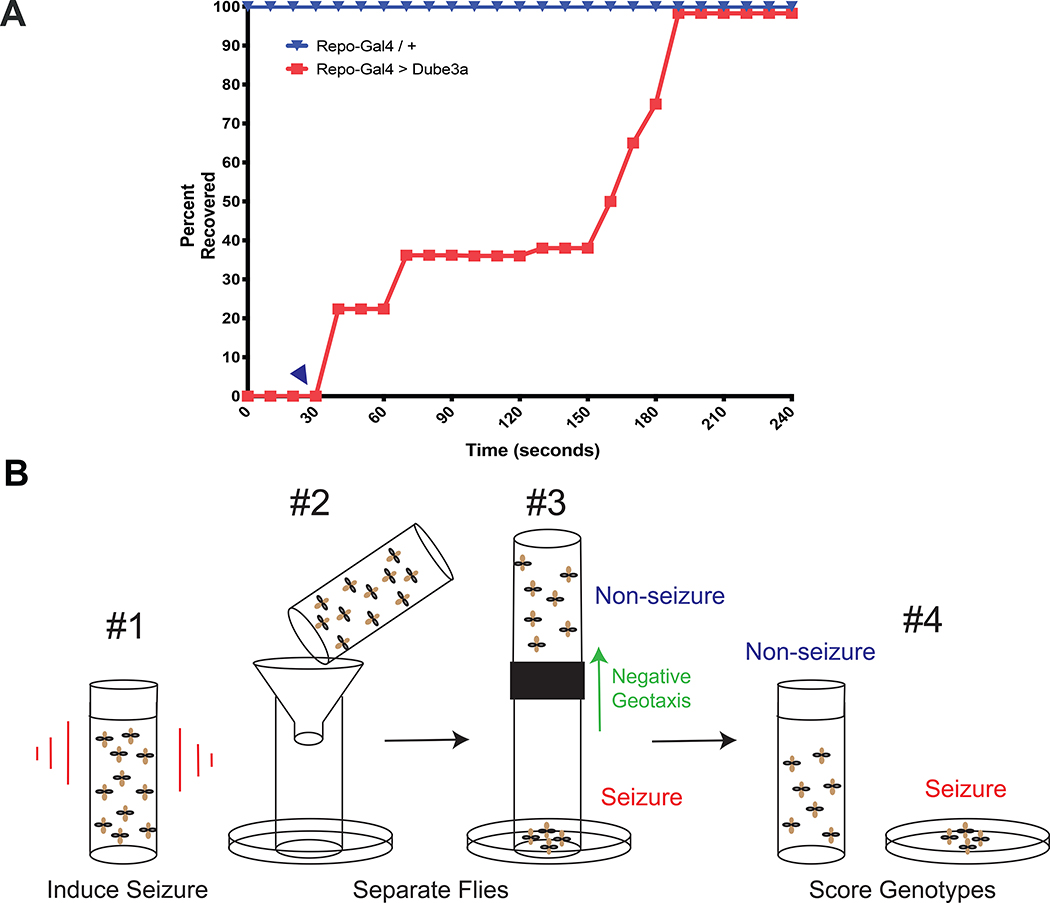

Figure 1. Primary Screening Protocol.

A) Only flies of the repo>Dube3a genotype have bang sensitivity (red filled squares). repo-GAL4 alone (blue inverted triangles) show no bang sensitive phenotype (top line). repo>Dube3a flies always take at least 30s to begin to recover from seizures (blue arrow head). Total recovery time for all flies of the repo>Dube3a genotype is ~ 99% recovery at 180s. This means there is a window of 30s during the paralysis phase of the seizure when all seizing flies are immobile. B) In panel #1 flies in a vial with no food are vortexed for 10s. In #2, flies that were vortexed are dumped into the funnel. #3, flies that are seizing drop into the petri dish, while flies that are not seizing can climb up the vile, negative geotaxis behavior, into a new tube. After no more than 30s, flies in both groups are collected with seizing flies in the dish and non-seizing flies in a new empty vial (#4).

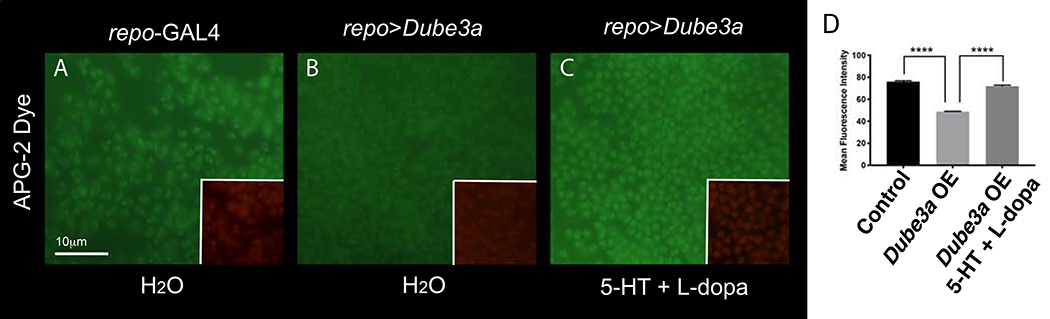

K+ Content Assays in Glial Cells

Asante Potassium Green 2 (APG-2, TEFlabs), a fluorescent cell membrane permeable K+ indicator, was used to quantify K+ levels in glial cells of the fly brain as previously described (27). Three-day old repo>tdTomato or repo>Dube3a+tdTomato flies fed on food with water or food with 0.04pM 5HT + L-dopa were briefly anesthetized and their heads were removed, submerged in room temperature Drosophila saline, brains dissected from the head case, and incubated with 7.5pM APG-2 in Drosophila saline for 1 hour. Brains were washed and wet mounted on a microscope slide with Drosophila saline. Images were captured from the optic lobe on a Leica DM6000B microscope (Leica) using a 63X oil immersion lens and filters for tdTomato and APG-2 respectively. A minimum of 35 cells was analyzed per group from at least 3 images each from 3 different brains per group.

Statistical Analysis and Graphing

All histograms and measurements are shown as mean ± SEM. To test for statistical significance, we used Student’s t-test with two tailed comparison (two groups) or among multiple samples, a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison correction using Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad). All analyses were performed with the experimenter blinded to genotype.

Results

Previously, we determined that glial expression of fly Dube3a using the pan-glial driver repo-GAL4 results in a bang sensitive phenotype, i.e. seizures after vortexing (27). These studies also revealed a 30 second window after vortexing wherein 100% of repo>Dube3a animals are in the paralysis phase which we confirmed in N=100 flies per genotype (Figure 1A). We designed a screening method exploiting this 30 second window of paralysis to separate flies that are not seizing from flies that are seizing. Seizing flies will fall to the bottom of the tube, but flies that are not seizing, have very short seizure recovery times, or are not the repo>Dube3a genotype, will crawl towards the top of the tube and can be collected separately (Figure 1B). Each group of flies is then evaluated under the microscope to identify only repo>Dube3a flies in each group for scoring. For screening, we used the Prestwick Chemical Library of 1280 off-patent small molecules previously approved for use in humans for a wide variety of clinical indications (Figure S1). Food was prepared containing 1μM of each compound plus DMSO only controls. Flies were grown at 25°C on drug containing food from embryos and tested in the modified bang sensitivity screen 3–5 days after eclosion.

Seizure Suppression Screening Reveals Eight Candidate Compounds

Our primary screening selection criteria for compounds that could suppress seizures was suppression in at least 25% of the repo>Dube3a animals within the 30s collection window. Using these criteria, we identified 17 compounds that could suppress seizures in flies that eclosed from triplicate crosses (Table 1). These compounds were not overrepresented in any one category and were not primarily used for the treatment of nervous system disorders (Figure S1). We noted that 5 out of 17 compounds, which passed primary screening, were related in some way to serotonin (serotonin hydrochloride (5HT), mirtazapine and minaprine dihydrochloride) or dopamine (minaprine dihydrochloride, levodopa (L-dopa) and prenylamine lactate) signaling.

Table 1.

Primary Screen Hits.

| Seizure | No seizure | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Compound | repo>Dube3a | UAS-Dube3a; TM3, Sb | repo>Dube3a | UAS-Dube3a; TM3, Sb | Total # repo>Dube3a | Percent Suppression |

| N/A | DMSO* | 6 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 6 | 0.0% |

| Prestw-1 | Azaguanine-8 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 17 | 14 | 42.9% |

| Prestw-17 | Levodopa | 8 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 12 | 33.3% |

| Prestw-19 | Captopril | 10 | 0 | 6 | 13 | 16 | 37.5% |

| Prestw-66 | Minaprine dihydrochloride | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 50.0% |

| Prestw-390 | Fusidic acid sodium salt | 9 | 0 | 7 | 20 | 16 | 43.8% |

| Prestw-457 | Meclozine dihydrochloride | 9 | 0 | 7 | 16 | 16 | 43.8% |

| Prestw-470 | Ceforanide | 21 | 0 | 7 | 23 | 28 | 25.0% |

| Prestw-1358 | Vatalanib | 21 | 1 | 8 | 47 | 29 | 27.6% |

| Prestw-1385 | Closantel | 17 | 1 | 7 | 43 | 24 | 29.2% |

| Prestw-481 | Serotonin hydrochloride | 14 | 0 | 7 | 32 | 21 | 33.3% |

| Prestw-1144 | Mirtazapine | 10 | 0 | 12 | 19 | 22 | 54.5% |

| Prestw-560 | Prenylamine lactate | 7 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 36.4% |

| Prestw-871 | Iopamidol | 12 | 1 | 7 | 43 | 19 | 36.8% |

| Prestw-1116 | Dorzolamide hydrochloride | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 50.0% |

| Prestw-1118 | Cefepime hydrochloride | 19 | 2 | 7 | 41 | 26 | 26.9% |

| Prestw-1711 | Felbamate | 3 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 50.0% |

| Prestw-1318 | Pranoprofen | 12 | 0 | 8 | 37 | 20 | 40.0% |

Percent suppression is the percentage of flies expressing Dube3a in glia that were not seizing.

Only one representative DMSO vial is shown here. For more extensive DMOS data in males and females see Figure S2.

Validation of the 17 primary screen compounds was performed using a more accurate bang sensitivity assay with individual flies and measuring the actual seizure recovery times. All 17 compounds were also tested at four different concentrations in order to identify the lowest effective seizure suppression dose and in the appropriate solvent (DMSO, water or EtOH depending on the compound). While there were no differences in seizure activity across different solvents, we did note a difference in variance in male flies versus female repo>Dube3a flies (Figure S2). Therefore, we tested both males and females separately for the validation assays.

The go/no go criteria for validation of a primary screen candidate was as follows: the compound must suppress seizures by at least a 50% decrease in recovery time versus solvent alone at one of the tested concentrations; 2) the suppression must reach a statistical significance by one-way ANOVA of at least pvalue≤0.01; 3) the suppression must occur in both males and females. Using these criteria we were able to identify 8/17 primary screen candidates that can suppress seizures in repo>Dube3a males and females (Figure S3). Using these stringent criteria we found that most of the compounds could suppress seizures by 50% in males and females at a concentration of 0.04μM in the food (the exception being Iopamidol, which required 1μM and both levodopa and dorzolamide hydrochloride which both required at least 0.2μM for suppression). A complete list of these compounds and their approved uses in humans can be found in Table S2. Drugs that failed the secondary validation can be found in Figure S4.

Once again, five compounds involved in serotonin and dopamine signaling identified in the primary screen reached significance including 5HT, mirtazapine, minaprine dihydrochloride, prenylamine lactate and L-Dopa. The relationship among the three serotonin signaling compounds provided clues to the mechanism of action of seizure suppression. Serotonin can stimulate 5-HT1, 5-HT2, 5-HT3 and 5-HT4,5,6,7 receptors, but mirtazapine is a strong antagonist of all serotonin receptors except 5- HT1A (33–36). Minaprine dihydrochloride is a serotonin and dopamine re-uptake inhibitor, and can therefore increase the levels of free serotonin and dopamine at the synapse (37). Another drug, prenylamine lactate, is known to prevent noradrenaline and dopamine from reuptake by storage granules, thereby increasing their concentration in the synaptic cleft (38, 39). Thus, both minaprine dihydrochloride and prenylamine lactate could possibly increase serotonin and dopamine levels at the synapse, which is consistent with the observation that levodopa can also suppress seizures in addition toserotonin (Figure S3). Additional information about these drugs can be obtained from Chemical Entities of Biological Interest (ChEBI, EMBL-EBI) and DrugBank databases.

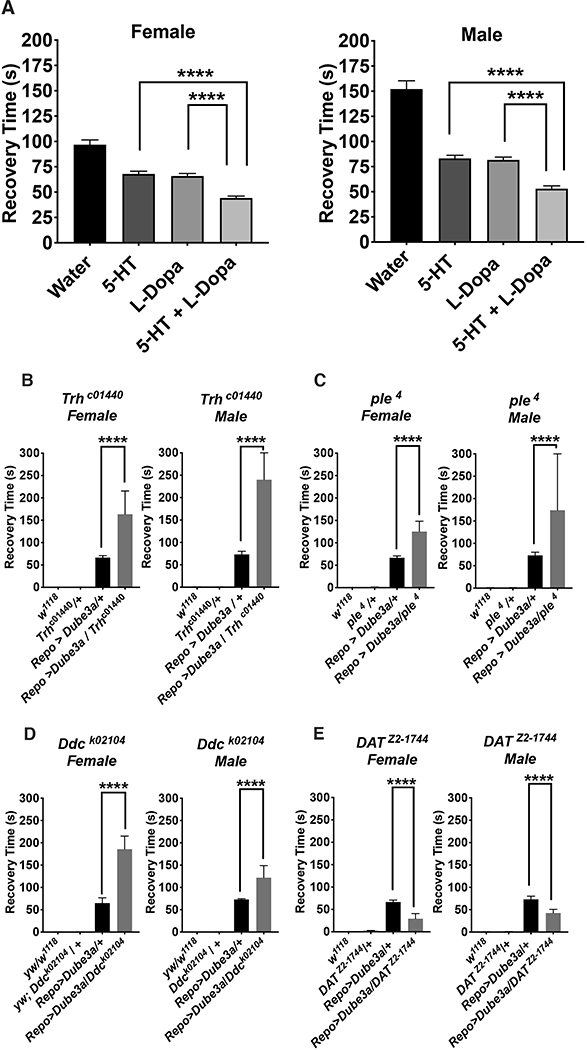

Combining Compounds with Serotonin Reveals an Additive Effect of Dopamine in Seizure Suppression

Next, we conducted experiments on the combined effect of 5HT with drugs modulating serotoninergic / dopaminergic signaling and other drugs that suppressed seizures in our screen. Three drugs related to serotonin or dopamine signaling (Minaprine HCl, Prenylamine lactate and Mirtazapine) and one unrelated drug (Dorzolamide HCl) were able to significantly decrease recovery time more than 5HT alone in female repo>Dube3a flies (Figure S5). The addition of minaprine hydrochrloride (pvalue≤0.05), prenylamine lactate (pvalue≤0.01), mirtazapine (pvalue≤0.05) plus 5HT decreased recovery time below the addition of 5HT alone in repo>Dube3a females, but had little effect on seizure suppression in males. However, the combination of 5HT plus L-dopa significantly decreased recovery time below 5HT alone in both male and female repo>Dube3a flies (pvalue≤0.001) (Figure 2A). These results show that a combination of serotonin and dopamine signaling may be required for the maximum seizure suppression in repo>Dube3a flies.

Figure 2. Combining serotonin with dopamine can further suppress seizures.

A) Synergistic effects of drugs at four diminishing concentrations indicated that of the 28 compounds identified, only L-dopa could further suppress the effects of serotonin alone in both males and females. Although some combinations were able to decrease recovery times in males or females, no other combination reached significance in both (Figure S5). B-D) Mutations in critical enzymes for either serotonin synthesis (Trhc1440), dopamine synthesis (ple4) or shared by both pathways (DdcDEI) significantly enhanced seizure recovery time in repo>Dube3a flies. E) Loss of function mutations in the dopamine transporter gene DATZ2−1744, which clears dopamine from the synaptic space, significantly suppressed seizures in repo>Dube3a animals, decreasing recovery time. Error bars are SEM. N>100 animals per column for (A), N>7 animals per column for (B–E).

To support this pharmacological data with genetic evidence, we acquired several mutants in various components of the serotonin and dopamine synthesis pathways and one mutant involved in dopamine re-uptake. The synthesis of both serotonin and dopamine is linked in both flies and humans via an enzymatic pathway that contains three enzymes. Tryptophan hydroxylase (Trh in flies) is the first enzymatic step in the conversion of tryptophan to serotonin followed by dopa decarboxylase (Ddc in flies) also known as aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase which coverts 5-hydroxytryptophan to serotonin. Dopamine is made by converting tyrosine to L-dopa via tyrosine hydroxylase (ple in flies) and then L-dopa is converted to dopamine via the same L-amino acid decarboxylase as serotonin (Ddc). Heterozygous loss of function mutations in Trhc1440, DdK02104 or ple4 significantly increased seizure recovery time, by as much as 2X, over repo>Dube3a animals alone (Figure 2B–D), indicating that down regulation of serotoninor dopamine exacerbates the seizure phenotype. A heterozygous loss of function mutation called DAT in the dopamine transporter gene (dopamine active transport or DAT in flies) which clears dopamine from the synaptic space, significantly suppressed seizures in repo>Dube3a animals (Figure 2E). These data suggest that more dopamine in the synaptic space can suppress seizures produced by elevated Dube3a in glia. In combination with the neurotransmitter synthesis data, these genetic studies fully support the pharmacological studies which suggest stimulation of serotonin and/or dopamine pathways can significantly suppress seizures in our model.

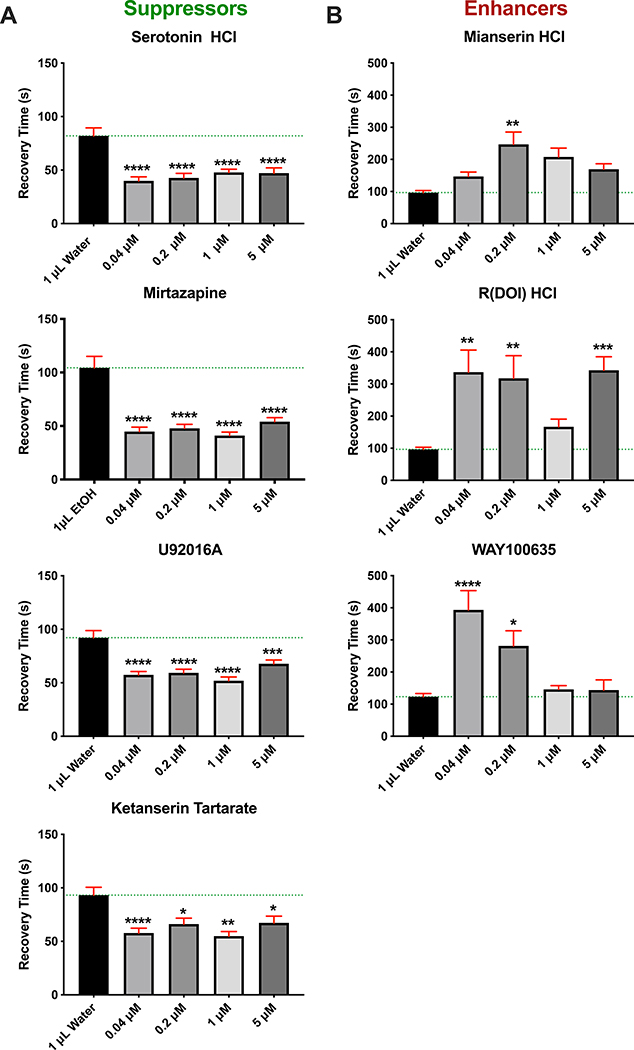

Stimulation of 5-HT1A Receptor Alone Suppresses Seizures in Repo>Dube3a Flies

Since both serotonin and mirtazapine, an antagonist of all serotonin receptors except 5- HT1A, were both able to suppress seizures in repo>Dube3a flies, we expanded our analysis using a series of specific serotonin receptor agonists and antagonists in order to address the hypothesis that stimulation of 5-HT1A alone can suppress seizures. Table S3 lists specific 5-HT receptor agonists and antagonists, and their predicted impact on seizures in repo>Dube3a flies. Two 5-HT1A agonists (serotonin hydrochloride and U92016A), two 5-HT1A antagonists (WAY100635 and mianserin HCl), one 5-HT2A antagonist (ketanserin tartrate) and one agonist for 5-HT2A,2B,2C, but not 5-HT1 ((R) DOI HCl), were assayed for their ability to suppress or enhance seizures at various concentrations. All drugs that stimulated 5-HT1A, directly or indirectly, were able to suppress seizures at concentrations down to 0.04μM in the food (Figure 3A). All compounds that either directly or indirectly routed serotonin away from 5-HT1A increased the seizure recovery times significantly in repo>Dube3a animals at concentrations ranging from 0.04μM to 1μM (Figure 3B). In fact, these same agonists and antagonists had identical effects on seizures in 9 day old flies expressing human UBE3A in glia at identical dosages that were effective in animals expressing fly Dube3a in glia (Figure S7). These results indicate that stimulation of 5-HT1A, or inhibition of 5-HT2A in the presence of active 5-HT1A, can pharmacologically suppress seizures generated in glia by over-expression of either fly or human UBE3A.

Figure 3. Serotonin Agonists and Antagonists Reveal a 5-HT-1A Mechanism for Suppression.

Repo>Dube3a flies were assayed for bang sensitivity (total recovery time in seconds) after being raised on food containing solvent alone (water or EtOH) versus increasing concentrations of various 5-HT1A agonists and antagonists. A) All compounds that act either as 5-HT1A agonists (Serotonin HCl, U92016A and Ketanserin Tartrate) or are antagonists to 5-HT2A receptor (Mirtazapine) significantly suppressed seizures in repo>Dube3a animals at concentrations down to 0.04μM in the food. B) All compounds that are 5-HT1A antagonists (Mianserin HCl, R(DOI) HCl, WAY100635) significantly enhanced seizure recovery time at concentrations between 0.04–0.2μM. Green lines are average recovery time in water or EtOH. Error bars (red) are SEM. N>60 animals per data point. All flies in this figure were female, males showed similar results (Figure S6).

To support these pharmacological findings, we performed genetic experiments designed to determine if serotonin could suppress seizures in repo>Dube3a flies in a 5-HT1A or 5-HT2A mutant background. Loss of function alleles of both 5-HT1A( 5HT1AA5kb) C1644 or 5-HT2A(5HT2A ) receptors were crossed to a stock containing both repo-GAL4 and UAS-Dube3a co-segregating over Xap (w1118; [repo-GAL4;UAS-Dube3a]/Xap). As expected, loss of 5-HT1A significantly increased seizure recovery time in repo>Dube3a animals, but loss of 5-HT2A had no effect (Figure S8). There was also a noticeable shift in transcript expression from 5-HT1A to 5-HT2A in repo>Dube3a flies vs control animals (Figure S8). Although the pharmacological data indicated that inhibition of 5-HT2A can also suppress seizures, these genetic experiments show that the 5-HT2A receptor itself is not involved in seizure suppression.

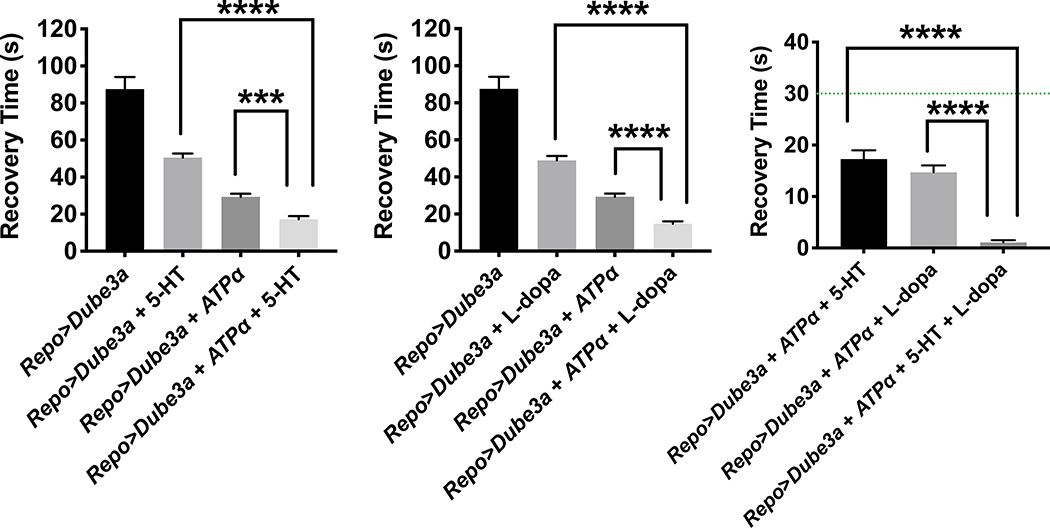

Previously, we showed that glial overexpression of Dube3a causes seizures and synaptic impairments in Drosophila concomitant with down regulation of the Na+/K+ pump ATPα (27). Serotonin and dopamine are known activators of glial or astrocytic Na+/K+ pump ATPα via adenyl cyclase dependent protein kinase A (PKA) signaling (40–42). To understand the mechanism underlying serotonin or dopamine mediated seizure suppression in repo>Dube3a flies, we fed serotonin or dopamine to flies co-expressing ATPα, which we previously showed could partially rescue seizures (27). We found that either serotonin or dopamine suppressed seizures more effectively in flies co-expressing ATPα and Dube3a, than flies expressing either ATPα + Dube3a (without drug) or Dube3a (with drug) (Figure 4A–B). Finally, adding a cocktail of both serotonin and dopamine while co-expressing ATPα almost completely suppressed seizures in repo>Dube3a flies (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Complete rescue of seizure phenotype in repo>Dube3a animals. A) Expression of ATPα with 5HT treatment significantly decreases recovery time from >85s to <20s on average. B) Expression of ATPα with L-dopa treatment significantly decreases recovery time from >85s to <20s on average. C) Expression of ATPα with 5HT + L-dopa treatment significantly decreases recovery time from >80s to <1s on average. Most animals had no seizures at all. The green line is 30s, the minimum recover time for all repo>Dube3a flies we used for primary screening. Error bars are SEM. N>20 animals per column.

The function of ATPα is to pump K+ into the cell while pumping Na+ into the extracellular space in an ATP-dependent manner. We previously showed that elevated Dube3a levels within glia reduce internal K+, consistent with the hypothesis that Dube3a down regulates ATPα levels causing a disruption of Na+/K+ homeostasis (27). We dissected whole brains from flies expressing the florescent marker tdTomato in glial cells both with and without Dube3a co-expression and fed a combination of 5HT + L- dopa. Brains were incubated in a cell-permeable fluorescent K+ indicator called Asante Potassium Green 2 AM (APG-2) as previously described (27) to visualize K+ levels within glia. Quantification of the fluorescence intensity of APG-2 in tdTomato+ cells is an indicator of the relative concentration of K+ in glial cells across genotypes. As expected, there was a significant reduction in APG-2 fluorescence in repo>tdTomato + Dube3a compared to control repo>tdTomato glial cells (Figure 5). However, the addition of a serotonin + L-dopa cocktail restored the concentration of K+ within the tdTomato+ glial cells (Figure 5). These data suggest that 5HT and L-dopa can modulate ATPα activity in glia, restoring intercellular K+ levels, and thereby maintaining the ionic homeostasis at the synapse.

Figure 5.

Restoration of K+ levels in glial cells though pharmacological intervention with 5HT and L-dopa. Fresh dissected fly brains incubated in the K+ binding fluorescent dye APG-2 (green) and tdTomato (Red) visualized at 100X on an upright fluorescent microscope. All images were taken using the same exposure settings. A) repo-GAL4 alone shows a moderate level of K+ within glial cells also marked by repo>td-tomato (red channel not shown). B) repo>Dube3a brains show a significant decrease in the amount of K+ detected in glia. C) repo>Dube3a animals raised on food containing a cocktail of 5HT + L-dopa show complete restoration of K+ levels in glia. D) Quantification of mean fluorescent intensity using 63X images (A-C) analyzed as described in the supplemental methods section using ImageJ. APG-2 signal quantification confirmed a significant rescue of K+ levels in glia for repo>Dube3a flies when raised on 5HT + L-Dopa. Error bars are SEM. N>35 cells per column.

Discussion

A Role for Serotonin Signaling in Seizure Suppression

Epilepsy is a common co-morbidity with ASD (25, 43–48), but can be more severe and difficult to treat in syndromic forms of ASD like Dup15q syndrome (1, 26, 49, 50). Most children with isodicentric duplications of 15q that include four copies of the UBE3A gene, biallelically expressed in glia (13, 15, 28, 29), suffer from pharmacoresistant seizures (26). Here we utilized our fly model of Dup15q to screen for compounds that can suppress seizures due to elevated levels of UBE3A in glia, not neurons (27). We identified 8 compounds that could significantly suppress these gliopathic seizures in both males and females. Surprisingly, five of these compounds (serotonin, levodopa, mirtazapine, prenylamine and minaprine dihydrochloride) are specifically related to serotonin and dopamine signaling. We show that suppression occurs preferentially through stimulation of serotonin 5-HT1A receptors, although it is not clear which specific dopamine receptors may be involved in seizure suppression. The pharmacological and genetic data presented here strongly suggest that specific agonists of 5-HT1A used to treat depression, for example the drug vortioxetine, could potentially be strong suppressors of seizure activity in Dup15q individuals.

A Possible Mechanism for Seizure Suppression

We found that inhibition of or heterozygous mutations in 5HT2A alone do not influence seizure susceptibility in repo>Dube3a flies (Figure S8). One explanation is that in the presence of 5-HT2A antagonists or background mutations in 5-HT2A receptor, free serotonin is still able to suppress seizures in repo>Dube3a flies through 5-HT1A. Cross talk between 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors has been documented in the mammalian brain previously (51) and expression studies here indicate that overexpression of Dube3a simultaneously down regulates 5HT1A receptor and up regulates 5HT2A receptor expression (Figure S8).

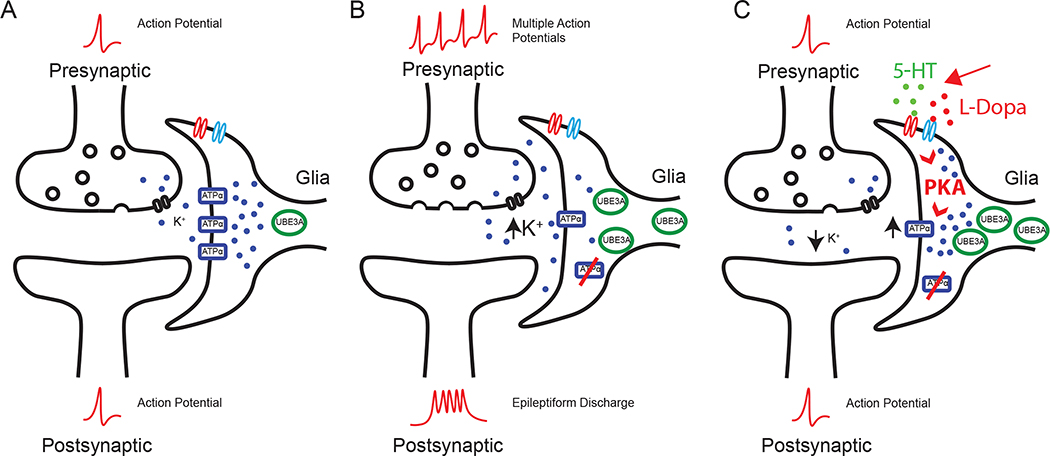

We show that both serotonin and dopamine are able to suppress seizures in repo>Dube3a flies. Previously, we showed that glial overexpression of Dube3a causes seizures and synaptic impairments in Drosophila concomitant with down-regulation of the Na+/K+ pump ATPα (27, 52). Serotonin modulates glial Na+/K+-ATPαse activity in the rat brain, through 5-HT1A receptor signalling (42). In addition, dopamine activates Na+/K+-ATPαses and Mg2+-ATPαses in the rat cerebral cortex (53). Using behavioral and live imaging data assaying glial cell K+ content, we show here that both serotonin and dopamine suppress seizures by modulating Na+/K+-ATPαse activity, despite the decrease in ATPα protein levels, possibly though the activation of ATPα by PKA phosphorylation. A massive influx of K+ ions into glia helps to restore the action potential to basal levels, suppressing seizures. Our new model proposes that serotonin and dopamine can reduce neuronal hyperexcitability by activation of PKA in glia, which in turn, activates the residual ATPα not degraded by Dube3a, restoring basal levels of K+ ions in the synaptic cleft (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

New model of ATPα modulation in Dup15q syndrome. A) Under normal conditions, the Na+/K+ exchanger ATPα pumps K+ ions from the synaptic cleft nearby glial support cells in order to maintain ionic homeostasis. B) When UBE3A levels are elevated in glia, the K+ concentration increases at the synapse because UBE3A can decrease ATPα levels in glia. The increase in K+ levels at the synapse leads to hyperpolarized neurons and pre-disposes these neurons to epileptiform activity. C) Here we have shown that a combination of 5HT and L-dopa can significantly suppress seizures in repo>Dube3a animals despite low levels of ATPα and increased Dube3a in glia. The primary method of this suppression is through the restoration of K+ imbalance. We have also documented a restoration of K+ levels in glial cells of the brain in the presence of 5HT + L-dopa. Here we propose a mechanism by which both 5HT and L- dopa can activate PKA, which in turn, activates residual ATPα within the glial membrane.

Compounds Unrelated to Serotonin or Dopamine that Can Suppress Seizures

The compound screen we conducted also yielded potential seizure suppressors unrelated to serotonin or dopamine signaling. Although we focused on serotonin and dopamine for our mechanistic studies, these other hits are interesting as well, since they regulate seizure activity via complementary mechanisms, which could prove useful in the future.

Pranoprofen, brand name Niflan, belongs to a class of medications called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). Niflan can block the synthesis of prostaglandins by inhibiting cyclooxygenase, an enzyme converting arachidonic acid to cyclic endoperoxides, precursors of prostaglandins (54). Cytokines and prostaglandins are inflammatory mediators in the brain, and their biosynthesis is enhanced following seizures (54). Dorzolamide hydrochloride is an inhibitor of carbonic anhydrases (CA), enzymes known to catalyze reversible hydration/dehydration of CO2/HCO3(–), respectively. CA inhibitors can reduce seizures through perturbation of the CO2 equilibrium and/or the inhibition of ion channels (55). Acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, is primarily used in combination therapy with other antiepileptic medications in both children and adults (55–57).

Vital dyes like brilliant vital red (58) and methyl blue IV (59) have been proposed before as anti-convulsive agents. The prevailing hypothesis was that these dyes work by rendering the blood-brain barrier impermeable to “convulsive toxins” in the systemic circulation (60). Recently, methylene blue has been found to be an anti-convulsant during self-sustaining status epilepticus (SSSE) induced by prolonged basolateral amygdala stimulation (BLA) in Wistar rats (61). Although speculative, it is possible that the contrast agent or dye lopamidol, identified in our screen (Figure S3), might function in a similar manner.

Advantages of Seizure Screening in Drosophila

Screening for compounds using a Drosophila model of a human disorder is not unprecedented. It’s been clear for some time that genes across the fly genome show significant homology to human genes when associated with human disease etiology (62). Recent efforts have also illustrated the use of Drosophila to quickly evaluate new disease associated variants in vivo (63–65) and compound screens have produced important new drugs for treating human conditions ranging from cancer to kidney stones (66–68), as well as nervous system conditions (69). In this study all of the genes in both serotonin and dopamine signaling, as well as the UBE3A gene, show high DIOPT scores of homology (70) to their human counterparts (Table S4). Functional studies in Drosophila support the idea that these basic neurotransmitter-signaling pathways are highly conserved from flies to humans (71–73). Although several mouse models of Dup15q syndrome have been made, none of these mice show the spontaneous seizures found in patients, but our fly model does recapitulate the seizure sensitivity phenotype (27). Even if these mouse models did show a seizure phenotype, it would be practically impossible to screen 1280 compounds in a short period of time as we have done here. Recent and ever expanding genetic tools available for human disease studies in the Drosophila system (63, 64, 74), the ease of compound screening (66, 69), the availability of a large collection of wild caught alleles for modifier studies (75, 76) and the relatively low cost, makes the fly system ideal for medium throughput screens like this one.

One of the limitations of this Dup15q model, however, is that we are unable to perform complex behavior analysis, primarily because these flies are weak and very sensitive to seizure induction. Although we have shown recently that we can identify genes which affect ASD-like behaviors in flies (77) including repetitive behaviors (grooming), social communication (mating latency) and social spacing (social interaction) we are unable to utilize these behavior tests to explore the ASD aspects of Dup15q syndrome in the current fly model.

Links Between Serotonin and Syndromic Epilepsy

Recent studies using a mouse model that represents int(15) more than the pharmacoresistant idic(15) cases does show serotonergic modulation of ASD phenotypes can be corrected with 5-HT (78), but this model does not display spontaneous seizure activity (19). The Nakai et al. study is consistent with our model, however, since these mice were made by simple 3X duplication of the syntenic region of 15q inclusive of the Ube3a locus. Compounds that modulate serotonin signaling have also proven effective in seizure suppression in a zebrafish model of the unrelated seizure disorder Dravet syndrome. Capitalizing on the ability to perform high-throughput screening in the fish model (79–81), multiple serotonin modulating compounds have been identified that have the potential to decrease seizure frequency in this model of pharmacoresistant epilepsy. While both of these studies support further investigation into a therapeutic role for the serotonergic pathway in seizure suppression, neither study was focused on a possible role for glial cells in this process as we demonstrate here in Drosophila.

Future Studies in Humans with Dup15q and Pharmacoresistant

Seizures Recently, our group identified an EEG biomarker in children with Dup15q syndrome, which has now been confirmed in other cohorts by high density EEG analysis (18, 82). This biomarker could potentially be used to assess the effects of treating children with Dup15q syndrome with 5-HT1A agonists like vortioxetine, an antidepressant, in an offlabel trial for seizure suppression in these children. Preliminary studies presented here show that vortioxetine is just as efficient in suppression of seizures as serotonin and more efficient than commonly used AEDs felbamate and valproic acid in our fly model (Figure S9). Additionally, our other validated drugs have shown more effective seizure suppression in both male and female flies, than the routinely used medications for Dup15q patients (26) like felbamate or valproic acid (83, 84) (Figure S9). Given the hint of success that treatment for depression in non-syndromic epilepsy results in a decrease in seizure frequency when patients are given drugs for anxiety or depression (85, 86), and more specific studies in rodent models of epilepsy indicating that treatment with 5HT1A agonists can reduce seizure susceptibility (87), our current study could significantly benefit the Dup15q community by providing a new, safe and a more effective method of decreasing seizure frequency.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCE TABLE.

| Resource Type | Specific Reagent or Resource | Source or Reference | Identifiers | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Add additional rows as needed for each resource type | Include species and sex when applicable. | Include name of manufacturer, company, repository, individual, or research lab. Include PMID or DOI for references; use “this paper” if new. | Include catalog numbers, stock numbers, database IDs or accession numbers, and/or RRIDs. RRIDs are highly encouraged; search for RRIDs at https://scicrunch.org/resources. | Include any additional information or notes if necessary. |

| Antibody | ||||

| Bacterial or Viral Strain | ||||

| Biological Sample | ||||

| Cell Line | ||||

| Chemical Compound or Drug | Drugs : [Prestwick 1280 compound library, Serotonin HCl, Pranoprofen, Iopamidol, Mirtazapine, Prenylamine lactate, Minaprine HCl, Levodopa, Dorzolamide HCl, Azaguanine 8, felbamate, valproic acid, vatalanib, meclizine, captopril, closantel, fusidic acid, cefepime, ceforanide]; [Mianserin HCl, U92016A, WAY100635, Ketanserin Tartarate]; [Vortioxetine, R(DOI)HCl] | Drugs : [Prestwick Chemical] - PMID 15145337, 29898895, 29067299; [Santacruz Biotechnology: PMID 28553207, 21749913, 12435434, 19041376, 29985473, 24370737]; [Sigma adlrich : PMID 26989517] respectively. | https://www.prestwickchemical.com/index.html http://www.prestwickchemical.com/libraries-publications.html https://www.scbt.com/home; https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/united-states.html https://www.fishersci.com/us/en/home.html | |

| Commercial Assay Or Kit | ||||

| Deposited Data; Public Database | ||||

| Genetic Reagent | ||||

| Organism/Strain | Drosophila Stocks : 5HT1AΔ5kb/CyO; DdcDE1; DATZ21744; Ddc27pr1/CyO; Ddck02104; ple4/TM3,Sb; Trhc01440; 5-HT2AC1644; 10XUAS-IVS-myr::tdTomato; repo-GAL4/TM3Sb; UAS-ATPα; UAS Dube3a; UAS human UBE3A; elav-GAL4 | BDSC#27640;BDSC#3168;BDSC#30867;BDSC#3190;BDSC#10508;BDSC#3279;BDSC#10531;BDSC#4830; BDSC#32222; BDSC#7415; F001458; Reiter et al., 2006, PMID: 16905559; Hugo Bellen (Baylor College of Medicine) | https://bdsc.indiana.edu/ | |

| Peptide, Recombinant Protein | ||||

| Recombinant DNA | ||||

| Sequence-Based Reagent | ||||

| Software; Algorithm | NIH Image J; Adobe Photoshop CC2018; Prism 8 | NIH and LOCI; Adobe; Graphpad - Prism respectively. | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/; https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html; https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ | |

| Transfected Construct | ||||

| Dye | Asante Potassium Green 2 (TMA + salt), Catalog number 3652 | TEFLabs.com |

Acknowledgements

This work was initiated through a UTHSC CORNET Award to G.P and L.T.R. and supported by NIH/NICHD R21HD091541 to L.T.R. K.A.H was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the Dup15q Alliance. Some 5HT agonists/antagonists were a gift from Dr. Charles Nichols, LSU Medical School. Stocks were obtained from the BDSC (NIH P40OD018537) for this study. We also thank Yesenia Sanchez and Andrew Liess for Drosophila work.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References Cited

- 1.Finucane BM, Lusk L, Arkilo D, Chamberlain S, Devinsky O, Dindot S, et al. (1993): 15q Duplication Syndrome and Related Disorders. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJH, et al., editors. GeneReviews(R). Seattle: (WA). [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiStefano C, Wilson RB, Hyde C, Cook EH, Thibert RL, Reiter LT, et al. (2020): Behavioral characterization of dup15q syndrome: Toward meaningful endpoints for clinical trials. Am J Med Genet A. 182:71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dindot SV, Antalffy BA, Bhattacharjee MB, Beaudet AL (2008): The Angelman syndrome ubiquitin ligase localizes to the synapse and nucleus, and maternal deficiency results in abnormal dendritic spine morphology. Hum Mol Genet. 17:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Judson MC, Sosa-Pagan JO, Del Cid WA, Han JE, Philpot BD (2014): Allelic specificity of Ube3a expression in the mouse brain during postnatal development. The Journal of comparative neurology. 522:1874–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landers M, Bancescu DL, Le Meur E, Rougeulle C, Glatt-Deeley H, Brannan C, et al. (2004): Regulation of the large (similar to 1000 kb) imprinted murine Ube3a antisense transcript by alternative exons upstream of Snurf/Snrpn. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:3480–3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albrecht U, Sutcliffe JS, Cattanach BM, Beechey CV, Armstrong D, Eichele G, et al. (1997): Imprinted expression of the murine Angelman syndrome gene, Ube3a, in hippocampal and Purkinje neurons. Nat Genet. 17:75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustin RM, Bichell TJ, Bubser M, Daily J, Filonova I, Mrelashvili D, et al. (2010): Tissue- specific variation of Ube3a protein expression in rodents and in a mouse model of Angelman syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 39:283–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rougeulle C, Glatt H, Lalande M (1997): The Angelman syndrome candidate gene, UBE3A/E6-AP, is imprinted in brain. Nat Genet. 17:14–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato M, Stryker MP (2010): Genomic imprinting of experience-dependent cortical plasticity by the ubiquitin ligase gene Ube3a. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:5611–5616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallace ML, Burette AC, Weinberg RJ, Philpot BD (2012): Maternal loss of Ube3a produces an excitatory/inhibitory imbalance through neuron type-specific synaptic defects. Neuron. 74:793–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang YH, Armstrong D, Albrecht U, Atkins CM, Noebels JL, Eichele G, et al. (1998): Mutation of the Angelman ubiquitin ligase in mice causes increased cytoplasmic p53 and deficits of contextual learning and long-term potentiation. Neuron. 21:799–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones KA, Han JE, DeBruyne JP, Philpot BD (2016): Persistent neuronal Ube3a expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of Angelman syndrome model mice. Scientific reports. 6:28238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grier MD, Carson RP, Lagrange AH (2015): Toward a Broader View of Ube3a in a Mouse Model of Angelman Syndrome: Expression in Brain, Spinal Cord, Sciatic Nerve and Glial Cells. PLoS One. 10:e0124649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mardirossian S, Rampon C, Salvert D, Fort P, Sarda N (2009): Impaired hippocampal plasticity and altered neurogenesis in adult Ube3a maternal deficient mouse model for Angelman syndrome. Exp Neurol. 220:341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamasaki K, Joh K, Ohta T, Masuzaki H, Ishimaru T, Mukai T, et al. (2003): Neurons but not glial cells show reciprocal imprinting of sense and antisense transcripts of Ube3a. Hum Mol Genet. 12:837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang P, Lev-Lehman E, Tsai TF, Matsuura T, Benton CS, Sutcliffe JS, et al. (1999): The spectrum of mutations in UBE3A causing Angelman syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 8:129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook EH Jr., Lindgren V, Leventhal BL, Courchesne R, Lincoln A, Shulman C, et al. (1997): Autism or atypical autism in maternally but not paternally derived proximal 15q duplication. American journal of human genetics. 60:928–934. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urraca N, Cleary J, Brewer V, Pivnick EK, McVicar K, Thibert RL, et al. (2013): The interstitial duplication 15q11.2-q13 syndrome includes autism, mild facial anomalies and a characteristic EEG signature. Autism Res. 6:268–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamada K, Tomonaga S, Hatanaka F, Nakai N, Takao K, Miyakawa T, et al. (2010): Decreased exploratory activity in a mouse model of 15q duplication syndrome; implications for disturbance of serotonin signaling. PLoS One. 5:e15126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Copping NA, Christian SGB, Ritter DJ, Islam MS, Buscher N, Zolkowska D, et al. (2017): Neuronal overexpression of Ube3a isoform 2 causes behavioral impairments and neuroanatomical pathology relevant to 15q11.2-q13.3 duplication syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics. 26:3995–4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishnan V, Stoppel DC, Nong Y, Johnson MA, Nadler MJ, Ozkaynak E, et al. (2017): Autism gene Ube3a and seizures impair sociability by repressing VTA Cbln1. Nature. 543:507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith SE, Zhou YD, Zhang G, Jin Z, Stoppel DC, Anderson MP (2011): Increased gene dosage of Ube3a results in autism traits and decreased glutamate synaptic transmission in mice. Sci Transl Med. 3:103ra197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strasser L, Downes M, Kung J, Cross JH, De Haan M (2018): Prevalence and risk factors for autism spectrum disorder in epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 60:19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buckley AW, Holmes GL (2016): Epilepsy and Autism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 6:a022749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bozzi Y, Provenzano G, Casarosa S (2018): Neurobiological bases of autism-epilepsy comorbidity: a focus on excitation/inhibition imbalance. Eur J Neurosci. 47:534–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conant KD, Finucane B, Cleary N, Martin A, Muss C, Delany M, et al. (2014): A survey of seizures and current treatments in 15q duplication syndrome. Epilepsia. 55:396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hope KA, LeDoux MS, Reiter LT (2017): Glial overexpression of Dube3a causes seizures and synaptic impairments in Drosophila concomitant with down regulation of the Na+/K+ pump ATPαlpha. Neurobiol Dis. 108:238–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burette AC, Judson MC, Li AN, Chang EF, Seeley WW, Philpot BD, et al. (2018): Subcellular organization of UBE3A in human cerebral cortex. Molecular Autism. 9:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hillman PR, Christian SGB, Doan R, Cohen ND, Konganti K, Douglas K, et al. (2017): Genomic imprinting does not reduce the dosage of UBE3A in neurons. Epigenetics Chromatin. 10:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benzer S (1971): From the gene to behavior. JAMA. 218:1015–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganetzky B, Wu CF (1982): Drosophila mutants with opposing effects on nerve excitability: genetic and spatial interactions in repetitive firing. J Neurophysiol. 47:501–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stone B, Burke B, Pathakamuri J, Coleman J, Kuebler D (2014): A low-cost method for analyzing seizure-like activity and movement in Drosophila. J Vis Exp.e51460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoyer D, Clarke DE, Fozard JR, Hartig PR, Martin GR, Mylecharane EJ, et al. (1994): International Union of Pharmacology classification of receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine (Serotonin). Pharmacol Rev. 46:157–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoyer D, Hannon JP, Martin GR (2002): Molecular, pharmacological and functional diversity of 5-HT receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 71:533–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pytliak M, Vargova V, Mechirova V, Felsoci M (2011): Serotonin receptors - from molecular biology to clinical applications. Physiol Res. 60:15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Celada P, Puig M, Amargos-Bosch M, Adell A, Artigas F (2004): The therapeutic role of 5- HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 29:252–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biziere K, Worms P, Kan JP, Mandel P, Garattini S, Roncucci R (1985): Minaprine, a new drug with antidepressant properties. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 11:831–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A (2005): Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review. Prog Neurobiol. 75:406–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gronberg M, Terland O, Husebye ES, Flatmark T (1990): The effect of prenylamine and organic nitrates on the bioenergetics of bovine catecholamine storage vesicles. Biochem Pharmacol. 40:351–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang LN, Li JX, Hao L, Sun YJ, Xie YH, Wu SM, et al. (2013): Crosstalk between dopamine receptors and the Na(+)/K(+)-ATPαse (review). Mol Med Rep. 8:1291–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Therien AG, Blostein R (2000): Mechanisms of sodium pump regulation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 279:C541–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pena-Rangel MT, Mercado R, Hernandez-Rodriguez J (1999): Regulation of glial Na+/K+- ATPαse by serotonin: identification of participating receptors. Neurochem Res. 24:643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berg AT, Plioplys S, Tuchman R (2011): Risk and correlates of autism spectrum disorder in children with epilepsy: a community-based study. J Child Neurol. 26:540–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Besag FM (2018): Epilepsy in patients with autism: links, risks and treatment challenges. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 14:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Canitano R (2007): Epilepsy in autism spectrum disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 16:61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee BH, Smith T, Paciorkowski AR (2015): Autism spectrum disorder and epilepsy: Disorders with a shared biology. Epilepsy Behav. 47:191–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spence SJ, Schneider MT (2009): The role of epilepsy and epileptiform EEGs in autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Res. 65:599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuchman R (2017): What is the Relationship Between Autism Spectrum Disorders and Epilepsy? Semin Pediatr Neurol. 24:292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Battaglia A (2005): The inv dup(15) or idic(15) syndrome: a clinically recognisable neurogenetic disorder. Brain Dev. 27:365–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Battaglia A (2008): The inv dup (15) or idic (15) syndrome (Tetrasomy 15q). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 3:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naumenko VS, Bazovkina DV, Kondaurova EM (2015): [On the Functional Cross-Talk between Brain 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A Receptors]. Zh Vyssh Nerv Deiat Im I P Pavlova. 65:240–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jensen L, Farook MF, Reiter LT (2013): Proteomic profiling in Drosophila reveals potential Dube3a regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and neuronal homeostasis. PLoS One. 8:e61952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Antonelli de Gomez de Lima M, Rodriquez de Lores Arnaiz G (1981): Tissue specificity of dopamine effects on brain ATPαses. Neurochem Res. 6:969–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shimada T, Takemiya T, Sugiura H, Yamagata K (2014): Role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of epilepsy. Mediators Inflamm. 2014:901902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aggarwal M, Kondeti B, McKenna R (2013): Anticonvulsant/antiepileptic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 23:717–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Millichap JG, Woodbury DM, Goodman LS (1955): Mechanism of the anticonvulsant action of acetazoleamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 115:251–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reiss WG, Oles KS (1996): Acetazolamide in the treatment of seizures. Ann Pharmacother. 30:514–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cobb S, Cohen ME, Ney J (1938): Brilliant Vital Red as an anticonvulsant. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 37:463–465. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lennox WG (1940): Study of epilepsy in America in 1938. Epilepsia 2nd series. 1(4):279–291. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aird RB (1939): Mode of action of brilliant vital red in epilepsy. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 42:700–723.. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cui ZQ, Li WL, Luo Y, Yang JP, Qu ZZ, Zhao WQ (2018): Methylene Blue Exerts Anticonvulsant and Neuroprotective Effects on Self-Sustaining Status Epilepticus (SSSE) Induced by Prolonged Basolateral Amygdala Stimulation in Wistar Rats. Med Sci Monit. 24:161–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reiter LT, Potocki L, Chien S, Gribskov M, Bier E (2001): A systematic analysis of human disease-associated gene sequences in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 11:1114–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chow CY, Reiter LT (2017): Etiology of Human Genetic Disease on the Fly. Trends Genet. 33:391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ugur B, Chen K, Bellen HJ (2016): Drosophila tools and assays for the study of human diseases. Dis Model Mech. 9:235–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wangler MF, Yamamoto S, Bellen HJ (2015): Fruit flies in biomedical research. Genetics. 199:639–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ali SN, Dayarathna TK, Ali AN, Osumah T, Ahmed M, Cooper TT, et al. (2018): Drosophila melanogaster as a function-based high-throughput screening model for antinephrolithiasis agents in kidney stone patients. Dis Model Mech. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dar AC, Das TK, Shokat KM, Cagan RL (2012): Chemical genetic discovery of targets and anti-targets for cancer polypharmacology. Nature. 486:80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mukherjee S, Tucker-Burden C, Kaissi E, Newsam A, Duggireddy H, Chau M, et al. (2018): CDK5 Inhibition Resolves PKA/cAMP-Independent Activation of CREB1 Signaling in Glioma Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 23:1651–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang L, Hagemann TL, Messing A, Feany MB (2016): An In Vivo Pharmacological Screen Identifies Cholinergic Signaling as a Therapeutic Target in Glial-Based Nervous System Disease. J Neurosci. 36:1445–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hu Y, Flockhart I, Vinayagam A, Bergwitz C, Berger B, Perrimon N, et al. (2011): An integrative approach to ortholog prediction for disease-focused and other functional studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 12:357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alekseyenko OV, Chan YB, Okaty BW, Chang Y, Dymecki SM, Kravitz EA (2019): Serotonergic Modulation of Aggression in Drosophila Involves GABAergic and Cholinergic Opposing Pathways. Curr Biol. 29:2145–2156 e2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Monier M, Nobel S, Danchin E, Isabel G (2018): Dopamine and Serotonin Are Both Required for Mate-Copying in Drosophila melanogaster. Front Behav Neurosci. 12:334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nebigil CG, Etienne N, Schaerlinger B, Hickel P, Launay JM, Maroteaux L (2001): Developmental^ regulated serotonin 5-HT2B receptors. Int J Dev Neurosci. 19:365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wangler MF, Yamamoto S, Chao HT, Posey JE, Westerfield M, Postlethwait J, et al. (2017): Model Organisms Facilitate Rare Disease Diagnosis and Therapeutic Research. Genetics. 207:9–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frochaux MV, Bou Sleiman M, Gardeux V, Dainese R, Hollis B, Litovchenko M, et al. (2020): cis-regulatory variation modulates susceptibility to enteric infection in the Drosophila genetic reference panel. Genome Biol. 21:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Palu RAS, Ong E, Stevens K, Chung S, Owings KG, Goodman AG, et al. (2019): Natural Genetic Variation Screen in Drosophila Identifies Wnt Signaling, Mitochondrial Metabolism, and Redox Homeostasis Genes as Modifiers of Apoptosis. G3 (Bethesda). 9:3995–4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hope KA, Flatten D, Cavitch P, May B, Sutcliffe JS, O’Donnell J, et al. (2019): The Drosophila Gene Sulfateless Modulates Autism-Like Behaviors. Front Genet. 10:574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nakai N, Nagano M, Saitow F, Watanabe Y, Kawamura Y, Kawamoto A, et al. (2017): Serotonin rebalances cortical tuning and behavior linked to autism symptoms in 15q11–13 CNV mice. Sci Adv. 3:e1603001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Griffin AL, Jaishankar P, Grandjean JM, Olson SH, Renslo AR, Baraban SC (2019): Zebrafish studies identify serotonin receptors mediating antiepileptic activity in Dravet syndrome. Brain Commun. 1:fcz008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Griffin A, Hamling KR, Knupp K, Hong S, Lee LP, Baraban SC (2017): Clemizole and modulators of serotonin signalling suppress seizures in Dravet syndrome. Brain. 140:669–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baraban SC, Dinday MT, Hortopan GA (2013): Drug screening in Scn1a zebrafish mutant identifies clemizole as a potential Dravet syndrome treatment. Nat Commun. 4:2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Frohlich J, Reiter LT, Saravanapandian V, DiStefano C, Huberty S, Hyde C, et al. (2019): Mechanisms underlying the EEG biomarker in Dup15q syndrome. Mol Autism. 10:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schmidt D (1993): Felbamate: successful development of a new compound for the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 34 Suppl 7:S30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jensen PK (1993): Felbamate in the treatment of refractory partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia. 34 Suppl 7:S25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hamid H, Kanner AM (2013): Should antidepressant drugs of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor family be tested as antiepileptic drugs? Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 26:261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cardamone L, Salzberg MR, O’Brien TJ, Jones NC (2013): Antidepressant therapy in epilepsy: can treating the comorbidities affect the underlying disorder? Br J Pharmacol. 168:1531–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wada Y, Shiraishi J, Nakamura M, Koshino Y (1997): Role of serotonin receptor subtypes in the development of amygdaloid kindling in rats. Brain Res. 747:338–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.