Abstract

Limited information on current dietary patterns of Native American (NA) adults exists. This paper describes the dietary intake of 582 NA adults, aged 19–75 years, living in six communities in New Mexico and Wisconsin in 2016–2017 and compares macronutrient and micronutrient intakes, estimated via a semi-quantitative 30-day Block Food Frequency Questionnaire, among different age and sex groups. NA adults consumed a diet high in % energy from total fat, saturated fat, added sugars, and sodium. A general trend of lower micronutrient intakes with increasing age was observed. Health professionals can apply this information to develop effective and culturally-relevant nutrition interventions.

Keywords: Native American, dietary intake, adults

Introduction

Compared to the general U.S. population, Native American (NA) adults have higher prevalence of obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (Carter et al. 2008; Halpern 2007). Chronic disease prevalence is also increasing among NA groups (Stang et al. 2005). Dietary patterns are strongly correlated with obesity and related health outcomes. Excess intakes of fat, saturated fat, and sodium are associated with increased risk for type 2 diabetes and CVD (Fialkowski et al. 2010; Hsiao et al. 2013).

The nutrition transition is the most common explanation for the high prevalence of overweight and obesity among NA adults (Schell and Gallo 2012). NA communities have moved away from traditional diets, characterized as high in complex carbohydrates and fiber and low in fat, and a highly active subsistence lifestyle of hunting, gathering, and agriculture (Halpern 2007; Schell and Gallo 2012). Around the 1920s, there were reports of malnutrition concerns in these populations (Compher 2006). Acculturated diets in the NA population have been documented as early as around the late 1970s and 1980s (Compher 2006). Today, NA dietary patterns are characterized as energy-dense with an emphasis on commodities that are high in refined carbohydrates, fat and sodium (Halpern 2007; Schell and Gallo 2012). Consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables among NA populations has also declined, as many NA communities face physical and economic barriers to accessing healthy food (Halpern 2007; Schell and Gallo 2012). Many NA adults live in rural areas with limited retail food outlets that carry healthy, fresh and affordable foods, forcing many community members to rely on gas-station stores (Gittelsohn et al. 2017). Low healthy food access is also tied to the history of NA people, who have experienced mass forced relocation to reservations (relocation era) and were forbidden to practice their traditional ways (Stannard 1992). NA children were also forced to attend off-reservation boarding schools that banned and punished the children for speaking their languages and practicing spiritual and cultural ways. This experience prevented intergenerational transmission of language, culture, and knowledge and practice of traditional diets (Evans-Campbell 2008). We estimate that in the NA communities in our study, four to five generations have passed since the relocation era and two to three generations since residential schools. Today, as these tribal communities face an increasing burden of chronic disease amongst their members, there is renewed interest in reviving traditional ways of life, especially those focused on traditional foods and physical activities with the potential to improve health (CDC 2019). However, the lack of reliable and consistent information on current dietary patterns in NA populations makes it difficult to establish baselines and develop initiatives aimed at improving nutritional intake.

The current dietary literature on nutrient intakes of various NA tribal groups includes studies that date back to 1980 of various sample sizes and participant ages, ranging from 10–91 years (Carter et al. 2008; Halpern 2007). Dietary data collection methods varied, and included single interviewer-administered 24-hour dietary recalls (Ballew et al. 1997; Carter et al. 2008; Sharma et al. 2010; Smith et al. 1996; Stang et al. 2005) , dietary records (Fialkowski et al. 2010) and quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire (QFFQ) (Sharma et al. 2010; Smith et al. 1996). Culturally appropriate QFFQs have also been developed for some NA populations, including the Navajo Nation (Sharma et al. 2010; The National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health 2006).

In general, the macronutrient intake of NA groups has been similarly described to that of the general U.S. population (HHS et al. 2015). The majority of both populations were found to be meeting total carbohydrate and protein intake recommendations while exceeding recommended intakes for total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol and sodium (Fialkowski et al. 2010) In some studies, the NA sample had higher median intakes of dietary cholesterol (Janette Carter et al. 1989; Stang et al. 2005) as well as % energy from fat and saturated fat than the general U.S. population from NHANES data (Carter et al. 2008) Overall difference in diet between NA populations in tribal reservations and general U.S. population was deemed insignificant (Stang et al. 2005)

Micronutrient intakes were less consistent across different studies examining different NA groups. While some studies found an inadequate intake of vitamin C among certain NA populations (Stang et al. 2005) , others did not (Carter et al. 2008; Sharma et al. 2010; Stang et al. 2005). Past research also found that in some NA populations intakes of vitamins A, B6 and E were below recommended dietary intakes, even lower than the general U.S. population intake (Stang et al. 2005). Low fruit, vegetable and fortified whole grain consumption was suggested as an explanation for low vitamin A and C intakes (Stang et al. 2005). Additionally, deficiencies in calcium (Ballew et al. 1997) , magnesium (Ballew et al. 1997) , folate (Ballew et al. 1997; Schell and Gallo 2012; Stang et al. 2005) and zinc (Ballew et al. 1997) were seen among both sexes and all adult age groups. Men and women below 60 years were found to have median intakes of thiamin and riboflavin below the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) (Schell and Gallo 2012). Median iron intake for women under 60 was also below RDA (Ballew et al. 1997). In comparison to NHANES data for the general U.S. population intake, median intakes of all vitamins except folate were found to be lower, while intakes of vitamin B12 and sodium were higher among studied NA populations (Stang et al. 2005).

Few studies have examined the factors associated with variance in macronutrient and micronutrient intakes. Sex and age have both been shown to moderate nutrient intake levels (Ballew et al. 1997; Smith et al. 1996; Stang et al. 2005). Despite substantial variations in traditional food habits, geographic location and climate, no significant differences in dietary nutrient intake were found by tribal association (Carter et al. 2008; Stang et al. 2005).

Primarily due to the general exclusion of NA populations living on reservations from national health and nutrition surveys (Carter et al. 2008) , there is a lack of data on nutrient intakes (Stang et al. 2005) , weight status, and general health of these populations (Carter et al. 2008). Population trends in nutrient intake are also worth examining in order to support dietary interventions for particularly vulnerable populations. For example, it is known that there is a correlation between increasing age and decreasing micronutrient intake in various NA groups (Ballew et al. 1997). A better understanding of the dietary intake of NA populations can help create the foundation needed to improve their health status.

To address these gaps, this analysis aimed to explore the dietary intakes of NA adults in six tribal communities in New Mexico and Wisconsin and to answer the following research questions:

What is the usual dietary intake of Native American adults in six tribal communities in New Mexico and Wisconsin?

Are there differences in the intakes of macronutrient and micronutrients among different age and sex groups in this NA population?

Methods

The cross-sectional data presented in this paper were collected as part of the baseline information from the OPREVENT2 trial (Obesity Prevention Research and Evaluation of InterVention Effectiveness in NaTive North Americans 2) (Gittelsohn et al. 2017). This intervention works with NA communities in New Mexico and Wisconsin to reduce obesity through promotion of healthy foods and physical activity at various levels, including policy, institutional, community worksites, schools, and retail food stores (Gittelsohn et al. 2017).

The OPREVENT2 trial was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (IRB), the Indian Health Service IRB, the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board. The six participating tribal communities also provided approvals in the form of tribal/chapter resolutions and school and health board approvals (Gittelsohn et al. 2017).

Participants and Recruitment

OPREVENT2 evaluated NA adults ages 18–75 years at baseline between September 2016 and May 2017. Two communities in Wisconsin and four in New Mexico of the United States participated in the trial. All six tribal communities were located in rural reservations, at least an hour distance from major population centers. Three of the communities had small-chain, medium-sized supermarkets, while the others only had small community stores. Rural was defined in this study based on the Economic Research Service’s 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes and/or self-identification by community leaders. Inclusion criteria for tribal communities included having at least: 500 on-reservation population, one on-reservation school, one on-reservation food store, including supermarket, grocery store, or convenience store, and one worksite that employs at least five tribal members. At baseline of the intervention, at least 100 adults from each of the six communities (n=601) were randomly recruited from a recruitment list provided by each tribal community. Households within each community were randomly selected from this recruitment list. From each randomly selected household, an individual was identified as the main food purchaser and/or preparer and screened for eligibility (e.g. tribal member, adult 18–75 years, not pregnant or breastfeeding, not planning to move in the next two years). Participants were contacted via telephone. Those who agreed to be interviewed provided informed written consent and were compensated for their time with a $40 gift card. Additional details on study design and methods of the OPREVENT2 trial are reported elsewhere (Gittelsohn et al. 2017).

Instruments

The Adult Impact Questionnaire (AIQ) was used to gather data on sociodemographic variables (e.g. age, education, marital status). A modified Block Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), based on the FFQ used in the Strong Heart Study Family Study, Cardiovascular Disease in Native Americans (Phase V) (Gittelsohn et al. 2017; Setiono et al. 2019; The National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health 2006) , was developed specifically between the research team and NutritionQuest for the OPREVENT2 study sample. The FFQ instrument was selected, as it is the favored instrument for measuring habitual dietary intake and has low respondent burden, administration and processing cost (Thompson and Subar 2013) The semi-quantitative 30-day FFQ included traditional NA foods common in New Mexico and Wisconsin (e.g. fry bread, pozole, beans), standard Block FFQ food items, and specific food items promoted and discouraged within the OPREVENT2 intervention (Setiono et al. 2019) The instrument contained 95 questions related to frequency (i.e. never, once per month, 2–3 times per month, once per week, 2 times per week, 3–4 times per week, 5–6 times per week, every day) and portion sizes of specific foods. Participants were asked to estimate portion sizes of each food they consumed using standard portion size illustrations. Pilot testing of the FFQ in two tribal communities not participating in the baseline assessments indicated that our instrument was culturally appropriate and inclusive of common traditional foods most commonly consumed by the target population. The FFQ did not gather any information on the use of nutritional supplements because supplements did not come up in the piloting. Data collectors completed all measurements and forms in private at each community site (Gittelsohn et al. 2017).

Data Collection

Data collectors were trained in-person in all evaluation instruments, recruiting, reviewing consent with participants, collecting data through electronic forms, and managing completed instruments. Throughout training, the principal investigator and supervisors provided feedback to the data collectors. All data collectors earned a certificate upon completion of their training.

Data Management, Safety and Monitoring

Completed AIQ instruments were sent directly to a data manager, who then worked with OPREVENT2 program staff to check the data for missing and extreme values, and entered data into Microsoft Access® (2016). All program staff received Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) certification.

Completed FFQ forms were scanned and sent directly to NutritionQuest (Berkeley, California, USA), the official analysis service for the Block questionnaire, for processing and analysis. Nutrient summaries were calculated and electronically sent to the data manager.

A Data Safety and Monitoring Board was formed to assure that the OPREVENT2 study conformed to standards of safety and confidentiality and to handle possible adverse events. The board meets 1–2 times per year.

Data Analysis

Age categories were formed to match those of the Dietary Reference Intake (DRI): 19–30; 31–50; 51–70; 71–75 years old. Participants below 19 years old (n=11) were removed from analysis. Caloric intake cutoffs were made at the lowest and top 0.5 percentile of the dataset (≤ 403.75 kcal or ≥ 9107.21 kcal), as they were deemed implausible based on an average basal metabolic rate. This cutoff removed 3 male and 5 female participants. In total, 19 participants were removed from the analysis, resulting in a final analytical sample of a total n=582.

For dichotomous variables (i.e. smoking status; participation in food assistance programs), chi-squared test was used to assess the differences in proportions between sex for each region of communities (Wisconsin and New Mexico). For ordinal variables (i.e. age groups, marital status and education level), Kruskal Wallis test was used to determine whether a statistically significant difference existed between the two sexes for Wisconsin and New Mexico communities. A post-hoc Dunn’s test with a Bonferroni adjustment was done if the probability was found to be ≤0.05 for ordinary pair-wise rank sum tests. Statistical significant for all tests was defined a priori at 0.05.

Since most nutrient intake distributions were skewed, mean intakes with their standard error (Tables 2–5), as well as intakes at the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles (Supplemental Tables 1-4), were presented for each examined micronutrient and macronutrient per age group within each sex. Mean energy (kcal) intakes were significantly different between male and female participants when analyzed by a two-tailed t-test (p <0.001). Since energy intake influences macronutrient and micronutrient intake, and DRI values vary by sex, dietary nutrient intakes of male and female participants were analyzed separately and adjusted for energy intake (Willett 2012). Our model specification checks, including assessment of model residuals, revealed that treating micronutrients in their continuous shape violated linearity assumptions. To address this issue and to determine age-group differences for mean intakes of each nutrient, separated by sex, we employed a linear regression model with a bootstrap method with 2000 repetitions (Supplemental Tables 5 and 6) and bias-corrected confidence intervals clustered on individual-level.

Table 2:

Mean Intake of Energy and Macronutrients by Age Group among Male Participants in the OPREVENT2 Study

| 19–30 y (n = 35) | 31–50 y (n = 66) | 51–70 y (n = 44) | 71–75 y (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | ||||

| Energy, kcal | 2846.8 (234.3)c, d | 2976.6 (211.2)c, d | 2151.1 (163.9)d | 1303.9 (178.0) |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 335.3 (28.9) | 341.8 (24.7) | 244.9 (22.4) | 137.1 (19.5) |

| % Energy from carbohydrate | 46.9 (1.2)d | 46.1 (0.8)d | 44.6 (1.2) | 41.9 (1.3) |

| Protein (g) | 111.5 (9.8) | 115.5 (8.9) | 83.6 (5.9) | 64.4 (10.4)a, b, c |

| % Energy from protein | 15.8 (0.5) | 15.5 (0.4) | 16.0 (0.4) | 19.4 (1.2)a, b, c |

| Total fat (g) | 117.7 (9.6) | 126.6 (9.4) | 93.9 (6.9) | 56.3 (7.3) |

| % Energy from fat | 37.3 (0.7) | 38.2 (0.6) | 39.8 (0.9)a | 39.5 (1.7) |

| Saturated fat (g) | 39.1 (3.4) | 42.5 (3.1) | 31.7 (2.3) | 18.7 (3.0) |

| % Energy from saturated fat | 12.3 (0.3) | 12.8 (0.3) | 13.5 (0.4)a | 12.9 (0.8) |

| Trans fat (g) | 4.5 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.4) | 3.5 (0.3) | 56.3 (7.3) |

| Fiber (g) | 19.0 (1.6) | 20.5 (1.6) | 14.9 (1.4) | 10.4 (1.2) |

| Total sugar (g) | 146.7 (13.4) | 153.6 (11.5) | 111.6 (12.4) | 56.6 (13.8) |

| % Energy from sweets, desserts | 15.9 (1.4) | 16.1 (1.0) | 14.8 (1.4) | 11.4 (2.8) |

| % Energy from alcoholic beverages | 1.3 (0.5)d | 2.0 (0.5)d | 1.0 (0.3)d | 0.06 (0.06) |

SE = Standard Error of Mean

Each column’s age category is assigned a letter accordingly:

= 19–30y,

= 31–50y,

= 51–70y,

= 71–75y.

Lower case superscript letters in each column indicate statistically significant age group comparisons of mean nutrient intakes after adjusting for total energy intake (p < 0.05), with the letters shown beneath the highest value of the comparisons.

Table 5:

Mean Intake of Micronutrients by Age Group among Female Participants in the OPREVENT2 Study

| 19–30 y (n = 73) | 31–50 y (n = 154) | 51–70 y (n = 182) | 71–75 y (n = 19) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | ||||

| Vitamin A (μg RAE) | 698.9 (52.2) | 698.3 (32.8) | 644.5 (33.8)a | 604.4 (74.1) |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 111.8 (9.3)c, d | 96.1 (5.0)c | 73.3 (3.9) | 60.8 (10.3) |

| Vitamin D (IU) | 118.2 (13.0) | 117.6 (8.1) | 116.9 (8.9)a | 137.7 (31.8)a |

| Sodium (mg) | 3869.0 (313.9) | 3532.1 (181.7) | 3107.2 (145.9)a | 2736.8 (301.6) |

| Folate (μg DFE) | 556.2 (44.4) | 504.1 (24.0) | 459.4 (24.4)a | 404.2 (51.1) |

| Zinc (mg) | 12.8 (1.1) | 12.2 (0.7)a, d | 10.9 (0.6)a | 10.3 (1.3)a |

| Calcium (mg) | 956.7 (66.4) | 885.1 (40.4) | 776.9 (39.5) | 783.3 (107.1) |

| Iron (mg) | 16.7 (1.3) | 15.3 (0.7) | 13.8 (0.7)a, b | 12.5 (1.6)a |

SE = Standard Error of Mean, RAE = Retinol Activity Equivalent, DFE = dietary folate equivalent

Each column’s age category is assigned a letter accordingly:

= 19–30y,

= 31–50y,

= 51–70y,

= 71–75y.

Lower case superscript letters in each column indicate statistically significant age group comparisons of mean nutrient intakes after adjusting for total energy intake (p < 0.05), with the letters shown beneath the highest value of the comparisons.

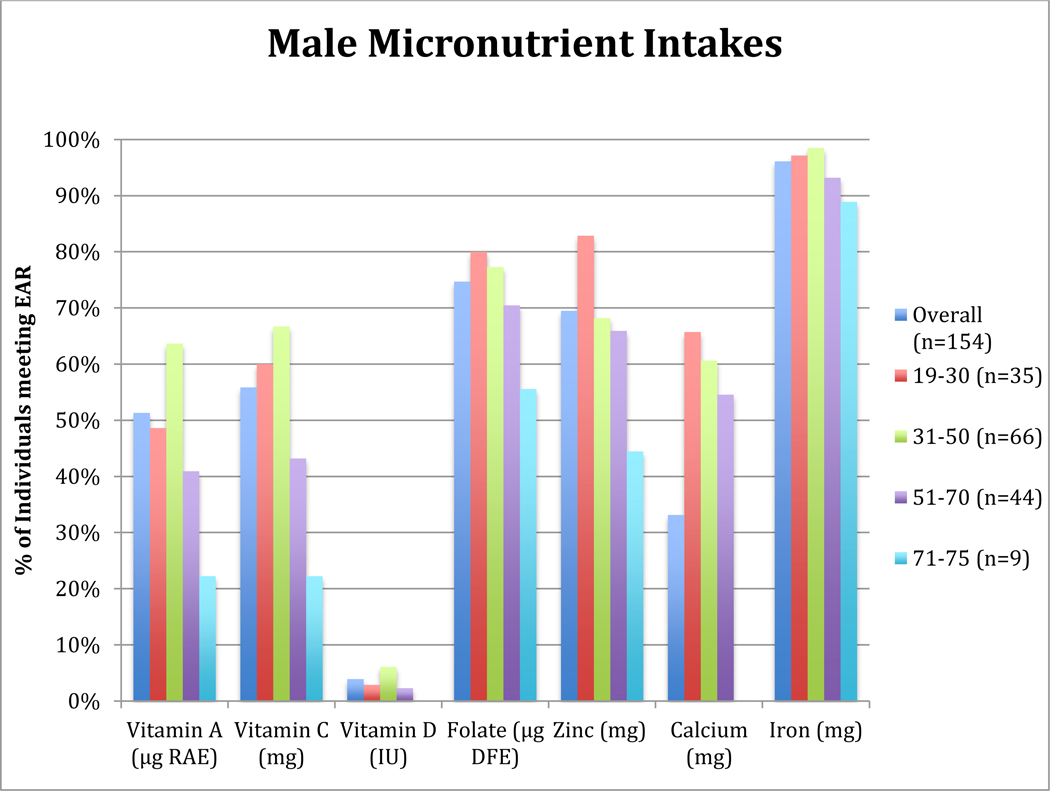

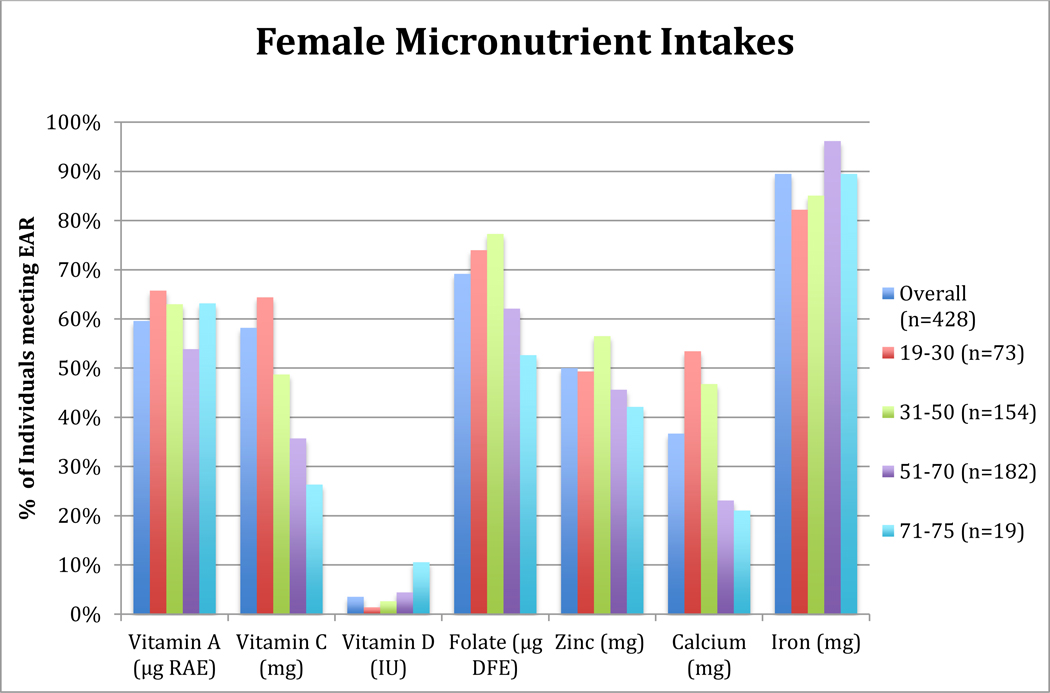

The macronutrients and micronutrients examined are detailed in Tables 2–4. Understudied micronutrients that have important health implications, such as vitamin D and zinc, and micronutrients found with deficient or excess intakes among NA tribes in previous studies, including vitamins A and C (Stang et al. 2005) , calcium (Ballew et al. 1997; Schell and Gallo 2012; Stang et al. 2005) , iron (Ballew et al. 1997) and folate (Ballew et al. 1997; Schell and Gallo 2012; Stang et al. 2005), were chosen for this analysis. Proportion of adults with micronutrient intakes meeting the sex- and age-specific Estimated Average Requirement for each examined micronutrient, as outlined in the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (HHS et al. 2015), was calculated for age-group comparisons of micronutrient intakes without energy adjustment (Figures 1–2).

Table 4:

Mean Intake of Micronutrients by Age Group among Male Participants in the OPREVENT2 Study

| 19–30 y (n = 35) | 31–50 y (n = 66) | 51–70 y (n = 44) | 71–75 y (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | ||||

| Vitamin A (μg RAE) | 708.8 (73.9) | 854.0 (58.9) | 670.8 (54.5) | 495.2 (85.7) |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 99.5 (9.1) | 113.8 (9.7) | 73.4 (7.3) | 49.3 (9.5) |

| Vitamin D (IU) | 148.2 (22.9) | 158.5 (16.1)d | 152.2 (14.9)d | 58.6 (11.1) |

| Sodium (mg) | 4692.1 (383.1) | 4875.7 (379.9) | 3442.2 (258.4) | 2300.9 (293.8)c |

| Folate (μg DFE) | 611.7 (54.4) | 659.3 (50.4) | 463.7 (36.3) | 336.4 (49.8) |

| Zinc (mg) | 15.6 (1.4) | 16.1 (1.2) | 11.8 (0.8) | 9.2 (1.5)a, b, c |

| Calcium (mg) | 1109.3 (112.8) | 1149.3 (79.4) | 882.1 (61.4) | 490 (82.0) |

| Iron (mg) | 19.4 (1.7) | 20.3 (1.5) | 14.7 (1.1) | 10.3 (1.3) |

SE = Standard Error of Mean, RAE = Retinol Activity Equivalent, DFE = dietary folate equivalent

Each column’s age category is assigned a letter accordingly:

= 19–30y,

= 31–50y,

= 51–70y,

= 71–75y.

Lower case superscript letters in each column indicate statistically significant age group comparisons of mean nutrient intakes after adjusting for total energy intake (p < 0.05), with the letters shown beneath the highest value of the comparisons.

Figure 1: Percentage of OPREVENT2 Male Participants meeting Dietary Reference Intake for Selected Micronutrients by Age Group.

Note: Column graph shows the percentage of individuals, overall and within each age group, with an intake that is the below sex- and age-specific Estimated Average Requirement for each listed micronutrient (20)

RAE = Retinol Activity Equivalent, DFE = Dietary Folate Equivalent

Figure 2: Percentage of OPREVENT2 Female Participants meeting Dietary Reference Intake for Selected Micronutrients by Age Group.

Note: Column graph shows the percentage of individuals, overall and within each age group, with an intake that is the below sex- and age-specific Estimated Average Requirement for each listed micronutrient (20)

RAE = Retinol Activity Equivalent, DFE = Dietary Folate Equivalent

All statistical analysis was conducted in STATA 13 (StataCorp., College Station, TX).

Results

Study participants included in this analysis were 428 women and 154 men (n=582), age 19–75 years (46.4±14.8) (Table 1). More than 65.0% of participants were from New Mexico. Majority of NA participants were under the age of 71 years. The distribution of age was only significantly different among participants in New Mexico communities (p < 0.05), while distribution of marital status was only significant among participants in Wisconsin communities (p < 0.01). Most men (58.3%) and women (57.9%) in Wisconsin tribes were current smokers, while only 13.0% of New Mexican participants were current smokers. For all communities, a majority of all participants (73.5%) participated in at least one food assistance program, with the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), church, and senior center meals being the most common. Most study participants (52.6%) completed more than a high school education.

Table 1:

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Participants

| Wisconsin Tribes | New Mexico Tribes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | Men | Sample Size (n) | Women | Sample Size (n) | Men | Sample Size (n) | Women | Sample Size (n) |

| Total Sample Size | 60 | 200 | 140 | 200 | 94 | 382 | 288 | 382 |

| Current Smoker, n(%) | 58.3% | 60 | 57.9% | 140 | 17.2% | 93 | 11.6% | 284 |

| Age | ||||||||

| Mean Age (y) (SE) | 45.6 (1.9) | 60 | 47.2 (1.2) | 140 | 42.9 (1.6) | 94 | 47.3 (0.9) | 288 |

| 19–30 years (%) | 16.7% | 60 | 15.0% | 140 | 26.7% | 94 | 18.1% | 288 |

| 31–50 years (%) | 45.0% | 60 | 40.0% | 140 | 41.5% | 94 | 34.0% | 288 |

| 51–70 years (%) | 33.3% | 60 | 40.7% | 140 | 25.5% | 94 | 43.4% | 288 |

| 71–75 years (%) | 5.0% | 60 | 4.3% | 140 | 6.4% | 94 | 4.5% | 288 |

| Food Assistance Participation, n(%) | ||||||||

| SNAP | 28.3% | 60 | 27.1% | 140 | 41.5% | 94 | 45.6% | 287 |

| Church | 5.0% | 60 | 10.0% | 140 | 35.1% | 94 | 30.3% | 287 |

| Senior Center Meals | 23.3% | 60 | 15.0% | 140 | 22.3% | 94 | 27.5% | 287 |

| WIC | 13.3% | 60 | 15.7% | 140 | 11.7% | 94 | 15.3% | 287 |

| Participating in at least one food assistance programa | 70.0% | 60 | 65.7% | 140 | 74.5% | 94 | 77.8% | 288 |

| Education Level, n(%) | ||||||||

| Less than High Schoolb | 16.7% | 60 | 12.9% | 140 | 19.4% | 93 | 18.9% | 285 |

| High School | 28.3% | 60 | 27.1% | 140 | 32.3% | 93 | 31.2% | 285 |

| GED/Technical/Associates Degree/Some College/Other | 51.6% | 60 | 55.0% | 140 | 41.9% | 93 | 42.8% | 285 |

| Bachelor/Master/Doctoral Degree | 3.3% | 60 | 5.0% | 140 | 6.5% | 93 | 7.0% | 285 |

| Marital Status, n(%) | ||||||||

| Single/Never Married | 51.7% | 60 | 56.4% | 140 | 43.5% | 92 | 31.7% | 281 |

| Married/Lives with Partner/Common Law | 28.3% | 60 | 22.9% | 140 | 51.1% | 92 | 48.0% | 281 |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 20.0% | 60 | 20.7% | 140 | 5.4% | 92 | 20.3% | 281 |

Abbreviations: SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), WIC (The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children), GED (General Educational Development), SE = Standard Error of Mean

Food assistance programs include WIC, SNAP, commodity foods, the Food Bank, senior center meals, church, other tribal food distribution programs, local farm surplus and the summer food service program.

Less than High School means uncompleted high school degree, elementary school, middle school or no education.

Macronutrient Intake for Native American Men

Mean macronutrient intakes, unadjusted for energy intake, of male participants by age categories are presented in Table 2. For male participants, significant differences were observed by age groups for all macronutrients after adjusting for energy intake, except carbohydrate (g), sugar (g), total, saturated and trans fat (g), fiber (g), and % energy from sweets and desserts (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Male participants of 71–75 years and 51–70 years had a significantly lower mean total daily energy intake than participants of younger age groups (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Men age 71–75 years consumed significantly less % energy from carbohydrate than men age 19–50 years (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Mean energy-adjusted protein intake in grams and % of energy of men age 71–75 years were significantly higher than that of younger men (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Males age 51–70 years had a significantly higher mean % energy from total and saturated fat than males age 19–30 years (p < 0.05 for all comparisons).

Males had average intakes of sweets and desserts that ranged from 11.4% to 16.1% of total energy (Table 2). Men 51–75 years old had lower mean and median intakes of fiber than younger men, but the difference was not significant after fiber intake was adjusted for energy intake (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 1). The oldest men consumed significantly less % of energy from alcoholic beverages than their younger counterparts in the study (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Alcohol was an insignificant % of energy for most males (overall median = 0%; mean = 1.4%). Results of statistical analyses are presented in Supplemental Table 5.

Macronutrient Intake for Native American Women

Mean macronutrient intakes, unadjusted for energy intake, of female participants by age categories are given in Table 3. Like males, female participants of 51–75 years had significantly lower mean total daily energy intakes than participants of younger age groups (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). After adjusting for total energy intake, mean carbohydrate intake of the youngest women, age 19–30 years, was significantly higher than intake of older women (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). However, the youngest women also had the lowest mean energy-adjusted protein intakes in grams and in % of energy, with a significantly lower mean protein intake than women above 31 years (p < 0.01 for all comparisons). Generally, the youngest women also had lower energy-adjusted total and saturated fat intake. On average, women age 19–30 years had significantly lower energy-adjusted intakes of total fat in grams than women age 31–70 years and significantly lower % of energy from total fat than women age 51–70 years (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Mean energy-adjusted intake of saturated fat in grams was lowest for women age 19–30 years, with differences in mean being statistically significant for all age group comparison (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). The youngest women also had significantly lower intake of % of energy from saturated fat than women 31–70 years (p < 0.05 for all comparisons).

Table 3:

Mean Intake of Energy and Macronutrients by Age Group among Female Participants in the OPREVENT2 Study

| 19–30 y (n = 73) | 31–50 y (n = 154) | 51–70 y (n = 182) | 71–75 y (n = 19) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | ||||

| Energy, kcal | 2551.5 (189.1)c, d | 2254.3 (104.7)c, d | 1941.9 (87.0) | 1752.0 (205.6) |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 316.8 (23.5)b, c, d | 259.4 (11.4) | 217.9 (10.2) | 203.6 (23.7) |

| % Energy from carbohydrate | 49.4 (0.9)b, c | 46.6 (0.6)c | 44.7 (0.5) | 46.4 (1.7) |

| Protein (g) | 89.1 (7.5) | 86.1 (4.7)a | 77.2 (4.1)a, b | 69.8 (8.5)a |

| % Energy from protein | 13.8 (0.3) | 15.2 (0.2)a | 15.7 (0.2)a | 16.2 (0.8)a |

| Total fat (g) | 105.5 (8.0) | 98.0 (5.0)a | 85.7 (3.8)a | 75.8 (9.8) |

| % Energy from fat | 37.6 (0.7) | 38.8 (0.5) | 40.0 (0.5)a | 38.7 (1.4) |

| Saturated fat (g) | 33.9 (2.6) | 32.1 (1.6)a | 27.8 (1.3)a | 24.9 (3.3)a |

| % Energy from Saturated Fat | 12.1 (0.2) | 12.7 (0.2)a | 12.9 (0.2)a | 12.7 (0.6) |

| Trans fat (g) | 4.0 (0.4) | 3.4 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.2) | 2.6 (0.4) |

| Fiber (g) | 17.3 (1.5) | 16.0 (0.8) | 15.0 (0.8)a, b | 13.4 (2.0) |

| Total sugar (g) | 153.6 (11.5)b, c, d | 119.5 (5.8)c | 92.2 (4.7) | 91.2 (10.5) |

| % Energy from sweets, desserts | 19.7 (1.2)b, c, d | 16.0 (0.7)c | 12.7 (0.6) | 12.4 (2.2) |

| % Energy from alcoholic beverages | 0.6 (0.2)d | 1.0 (0.2)d | 1.0 (0.3)d | 0.02 (0.02) |

SE = Standard Error of Mean

Each column’s age category is assigned a letter accordingly:

= 19–30y,

= 31–50y,

= 51–70y,

= 71–75y.

Lower case superscript letters in each column indicate statistically significant age group comparisons of mean nutrient intakes after adjusting for total energy intake (p < 0.05), with the letters shown beneath the highest value of the comparisons.

Furthermore, younger women in this sample tended to have higher energy-adjusted sugar intakes and lower fiber intakes. The youngest women, age 19–30 years, had significantly higher energy-adjusted sugar intakes in grams and in % of energy from sweets and desserts than their older counterparts, while women age 31–50 years had significantly higher intakes than women age 51–70 years (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Although mean and median unadjusted fiber intakes decreased with increasing age groups (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 2), women age 19–50 years had significantly lower mean energy-adjusted fiber intakes than women age 51–70 years (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Similar to male participants, % of energy from alcohol was negligent for most female participants, and the oldest females had a significantly lower mean intake % of energy from alcohol than younger females (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Results of statistical analyses are presented in Supplemental Table 6.

Micronutrient Intake

Mean micronutrient intakes, unadjusted for energy intake, of male and female participants by age categories are given in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. To compare unadjusted micronutrient intakes by age categories, the proportion of males and females with micronutrient intakes meeting the sex- and age-specific EAR for each nutrient in each age category were calculated (Figures 1 and 2) (The Office of Dietary Supplements, n.d.). These figures are for age-group comparison purposes; prevalences shown are not an assessment of dietary adequacy, as the FFQ may not capture all foods consumed by individuals.

About 4% of men and women in this study (≤6% of individuals within each age group) had intakes of vitamin D meeting the EAR (Figures 1 and 2). The oldest male and female participants had the lowest proportion of individuals with intakes meeting the EAR for vitamin C (22.2% and 26.3%, respectively). Majority of women age 19–30 years and men age 19–50 years had intakes of vitamin C meeting EAR. Prevalence of vitamin A intake meeting EAR was also lowest in the oldest men age 71–75 years, with about 38% of men age 51–75 years with intakes meeting the EAR (Figure 1). However, most women in each age group achieved adequate intakes of vitamin A, with the proportion of individuals with intakes meeting EAR within each age group ranging from 53.9% to 65.8% (Figure 2). Most men, age 19 to 70 years, had intakes of calcium meeting the EAR. However, for all male participants of 71–75 years (n=9), the FFQ did not capture intakes meeting the EAR for calcium. While 53.4% of females 19–30 years had calcium intakes meeting the EAR, most females above 30 years had low calcium intakes, with only 22.9% of females 51–75 years meeting the EAR.

Half of female participants had zinc intakes meeting the EAR, while the proportion of men with zinc intakes meeting EAR for each age group was above 65% for all age groups except 71–75 years. Iron consumption for most men and women met the EAR. Except for participants age 71–75 years, over 60% of males and females in all other age groups had intakes of folate meeting the EAR. Over 50% of women within each age group consumed sodium over the UL, with the highest proportion found among women age 31–50 years (data not presented in figures). More than 75% of male participants below 71 years consumed sodium over the UL, but only 33% of males 71–75 years had excess intakes.

After adjusting for energy intake, several micronutrient intakes differed significantly by age categories (Tables 4 and 5). Compared to men 31–70 years, men age 71–75 years had a significantly lower and energy-adjusted mean intake of vitamin D (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). They also had a significantly higher energy-adjusted mean sodium intake than men age 31–50 years (p < 0.05). The oldest males also had significantly higher energy-adjusted mean intake of zinc than all younger males in this sample (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Results of statistical analyses are presented in Supplemental Table 5.

Additionally, the youngest women in the study sample, age 19–30 years, had significantly higher and lower energy-adjusted mean intakes of vitamin C and vitamin D, respectively, than women age 31–70 years (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Women age 51–70 years also had a significantly lower energy-adjusted mean vitamin C intake than women age 31–50 (p < 0.01). Furthermore, younger women in the study had lower energy-adjusted intakes of zinc and iron. On average, women age 51–70 years also had significantly higher energy-adjusted intakes of vitamin A, folate and sodium than women 19–30 years (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Results of statistical analyses are presented in Supplemental Table 6.

Discussion

Based on the dietary intake captured by the FFQ, NA adults in the six communities in New Mexico and Wisconsin had high % energy from total and saturated fat and from added sugars (sweets and desserts), and high intake of sodium.

A general trend of lower micronutrient intakes, unadjusted for energy, with increasing age was observed among our NA study participants. This trend was also found in previous studies that utilized the 24-hour dietary recall (Ballew et al. 1997; Carter et al. 2008). This suggests that elderly NA living in rural communities may be at a higher risk for certain nutrient inadequacies. Their diets may not provide sufficient micronutrients, which is consistent with the findings from the 1991–1992 Navajo Health and Nutrition Survey (NHNS) that noted diets of limited variety among elderly Navajo (Ballew et al. 1997). In the literature, elderly NA are more likely than their younger counterparts to be food insecure (Mullany et al. 2013). Food insecurity can encourage the consumption of cheap, energy-dense foods over more expensive, nutrient-dense foods (Mullany et al. 2013) , thereby increasing the risk of micronutrient deficiencies seen among the NA elderly population.

The highest proportions of low calcium intakes were seen among the oldest men and women. Low calcium is particularly problematic for older women because of their increased risk for osteoporosis (Institute of Medicine 2010). The trend of decreasing calcium intake with increasing age group was also observed among female Navajo participants of the 1991–1992 NHNS (Ballew et al. 1997). Intakes of calcium and vitamin C have been consistently low among similar populations. For example, low intakes of these micronutrients have been reported among Navajo adults in the past, as well as in more recent studies (Ballew et al. 1997; Sharma et al. 2010). Altogether, this study’s data suggest a low intake of fruits, vegetables and dairy in the diet of study participants. A possible explanation for lower calcium intake with aging could be the increased prevalence of lactose intolerance with age (Thorn 2010) that prompts older adults to avoid dairy products. Improving education on alternative sources of calcium and increasing the community’s access to lactase enzyme supplements and lactose-free dairy products may be future potential intervention approaches.

Men in this study had significantly higher food energy intake than women (p = 0.0001). The sex-differences in total caloric intake, and presumably absolute nutrient intake, are reasonable when considering that individuals with a larger body size and/or muscle mass will likely have a higher energy requirement (Westerterp 2007).

Our study participants had low fiber intakes, demonstrating an overall low intake of fiber-rich foods such as whole grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables. Previous studies have also found that NAs are less likely than White, Black and Hispanic populations to consume the number of servings of fruits and vegetables recommended by the USDA (Berg et al. 2012) , suggesting the need to improve the NA food environment and their access to affordable fruits and vegetables.

Younger NA adults in this study were found to have a high sugar intake, which may be due to a high intake of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), as past studies have reported a high intake of SSBs in NA, especially in the young and those with less education and income (Yracheta et al. 2015). High sodium consumption was seen across all age groups and sexes in the study population. High mean and median values of sodium intake observed in this study and the large proportion of participants with intakes above 2300mg/day suggest an excessively high sodium intake within this population. The high sodium consumption may also be due to a high intake of processed or prepared foods, as 58% of study participants noted that prepared foods from restaurants, including fast food restaurants, carry-outs and delis, were brought home for the family some or most of the time.

Overall, mean and median values of vitamin D in each age group were low. However, study data did not account for vitamin D obtained through supplements and foods not captured in the FFQ and produced endogenously. The low levels of vitamin D intake across all age groups noted in this large sample of NA adults residing in the New Mexico and Wisconsin suggest the need for further research on vitamin D status of these populations, especially since calcitriol, the active metabolite of vitamin D, has been linked with preventative or therapeutic action in cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic conditions (Institute of Medicine 2010). Older adults are also less efficient at synthesizing vitamin D and tend to have less sun exposure (Office of Dietary Supplements 2018). Furthermore, studies have found that vitamin D supplementation was less effective in raising serum 25OHD levels, the biomarker for vitamin D, in obese elderly participants and that vitamin D was stored in adipose tissues instead of being released when needed in obese subjects (Institute of Medicine 2010). These findings require additional investigation but have important implications on dosage recommendations when addressing deficient intakes of vitamin D among NA populations that have higher prevalence of obesity (Institute of Medicine 2010).

Study Limitations and Strengths

One limitation of this study is that nutritional supplement intake was not measured, as the FFQ was designed and adapted to focus on foods and beverages that were encouraged or discouraged by the OPREVENT2 trial rather than to capture all intake. Data on vitamin and mineral supplements would have provided a better estimate of micronutrient intakes. However, many previous studies assessing NA nutrient intakes have also excluded supplements from assessments of nutritional intake (Fialkowski et al. 2010; Smith et al. 1996; Stang et al. 2005). Data on vitamin supplement intake was excluded from Ballew et. al’s study analysis largely due to the minimal contribution of supplements to the intakes of the study participants (<2%) who reported taking them (Ballew et al. 1997). Due to the nature of FFQ data, we were also unable to report dietary adequacy or compare collected dietary data to other studies that utilize data collected via dietary recalls, such as NHANES data. While dietary recalls provide more specific intake data since they do not rely on a finite food list, quantitative FFQs estimate an individual’s usual intake and are less affected by when the survey was administered (Smith et al. 1996). Furthermore, dietary data captured in this study provide valuable information on dietary intake between genders and among age groups. To further investigate macronutrient and micronutrient adequacy among this population, future studies should employ multiple 24-hour diet recall.

Another limitation is that food preparation methods and sources of food are not captured in the FFQ. Some information on food source was collected as part of the AIQ but was limited to generalizations. Sources and preparation methods of food can affect the nutritional content of the food being consumed. For instance, home-cooked meals typically have lower levels of sodium and fat, because meals bought from restaurants and other food vendors contain more salt and oil (Guthrie, Lin, and Frazao 2002). Additionally, sodium levels noted in this study may not truly reflect intake since nutritional contents were based on FFQ data (i.e. average foods rather than specific foods consumed by study participants). Recall and response bias also affects the quality of the dietary data captured by the 30-Day FFQ, where participants overestimate and underestimate intake of various nutrients and food groups. To account for potential inaccurate reporting of typical dietary consumption, implausible energy intakes were excluded from the present analysis. Furthermore, baseline data collector training was held to assure high quality data collection also limited response bias. Most data collectors also spoke the local language and were more familiar with Native dietary habits, which may have reduced participant bias. Random selection of participants and the study’s low refusal rate of 3.8% also reduced selection bias.

The FFQ instrument was also limited in that it lacked detail since it utilized a finite food list and was ultimately a subjective estimate of dietary intake. However, FFQs are one of the most common tools to estimate habitual dietary consumption and were found to be more accurate than 24-hour recalls when estimating energy and nutrient intakes in Pima Indians (Smith et al. 1996). The Block FFQ used in this study was also deemed inclusive of Native foods through informal piloting in two tribal communities. It was modified to include traditional NA foods commonly consumed in the Upper Midwest and Southwest regions as well as foods that the OPREVENT2 program promotes and discourages, which improves the ability of the instrument to accurately capture food and food group consumption and nutrient intake. Furthermore, data collectors used food illustrations to help participants assess portion sizes of foods they consumed to increase validity of dietary data.

This study included a large number of NA participants (n = 582) from six NA tribes in New Mexico and Wisconsin of the United States. However, most of the study sample was female due to the study’s eligibility criteria that specified participants to identify as the main food preparer and/or purchaser in the household. Thus, the nutrient intake and age-group comparisons described in this study may be more reflective of female NA in these regions. The smaller male cohort in this study may have also masked significant age-group differences in nutrient intakes.

This study describes the macronutrient and micronutrient intakes of rural NA adults in the New Mexico and Wisconsin and the differences in intakes observed by sex and age groups. The findings of this study add to the current literature on the nutrient intakes, especially of different age groups, of NA. Further research on the underlying reasons for the relatively lower energy-unadjusted micronutrient intakes among elderly NA, including dietary habits, personal and cultural perceptions of food, can help develop new and improve existing nutrition interventions and policies aimed at improving the health and nutrition status of this underserved population. Considering that 73.5% of all study participants participated in at least one food assistance program, these programs, especially the senior center meals, could provide an effective platform through which nutritional education and interventions could reach this population. Public health officials should support increased efforts in education and in reducing salt content in processed foods and foods provided through food assistance programs. Furthermore, as elderly persons are especially vulnerable to undernutrition and food insecurity, vitamin and mineral supplementation at senior centers may also be beneficial. Health professionals can apply this information on the baseline dietary intake of NA adults in Wisconsin and New Mexico to develop targeted, effective, and culturally-appropriate nutrition interventions at the individual and population levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the OPREVENT2 interventionists for intervention implementation and data collection at each tribal community. We also thank all tribal leaders, health directors, teachers and other community members that cooperated with the OPREVENT2 trial.

Source of financial support

Study reported in the manuscript was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under Grant R01HL122150.

Abbreviations

- NA

Native American

- CVD

Cardiovascular diseases

- IOM

Institute of Medicine

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- AIQ

Adult Impact Questionnaire

- FFQ

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NHNS

Navajo Health and Nutrition Survey

- EAR

Estimated Average Requirement = the estimated level of nutrient intake that fulfills the requirement of half of the healthy individuals within a particular life-stage and gender group (9)

- RDA

Recommended Dietary Allowance = the average daily dietary intake level that would meet the nutrient requirement of 97–98% of healthy individuals in a particular life-stage and gender group population; set by adding two standard deviations to the Estimated Average Requirement for a specific micronutrient

- AI

Adequate Intake = the recommended level of intake when EAR cannot be set that is based on observational or experimentally derived estimations of nutrient intake by healthy individuals

- DRI

Dietary Reference Intake = lists of the RDA or AI for all micronutrients set by the the Institute of Medicine

- UL

Tolerable Upper Intake Level = the highest level of intake before almost all individuals in the general population experience any adverse health effects due to consumption of that nutrient

Footnotes

Conflict of financial and funding disclosure

All authors have no conflict of interest.

Bibliography

- Ballew C, White LL, Strauss KF, Benson LJ, Mendlein JM, and Mokdad AH. 1997. Intake of Nutrients and Food Sources of Nutrients among the Navajo: Findings from the Navajo Health and Nutrition Survey. The Journal of Nutrition 127(10): 2085–2093S.[http://jn.nutrition.org/content/127/10/2085S]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C, Daley C, Nazir N, Kinlacheeny J, Ashley A, Ahluwalia J, Greiner K, and Choi W. 2012. Physical Activity and Fruit and Vegetable Intake among American Indians. Journal of Community Health 37(1): 65. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9417-z[http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=104630532&site=ehost-live&scope=site]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter TL, Morse KL, Giraud DW, and Driskell JA. 2008. Few Differences in Diet and Health Behaviors and Perceptions were Observed in Adult Urban Native American Indians by Tribal Association, Gender, and Age Grouping. Nutrition Research 28(12): 834–841. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2008.10.002[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0271531708002248]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. 2019. Good Health and Wellness in Indian Country. Last Modified February 12, 2019. Accessed Apr 14, 2019 https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/indian-country.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Compher C 2006. The Nutrition Transition in American Indians. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 17(3): 217–223. doi: 10.1177/1043659606288376[ 10.1177/1043659606288376]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Appendix E-2.1 of Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T 2008. Historical Trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska Communities: A Multilevel Framework for Exploring Impacts on Individuals, Families, and Communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312290[ 10.1177/0886260507312290]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fialkowski MK, McCrory MA, Roberts SM, Tracy JK, Grattan LM, and Boushey CJ. 2010. Estimated Nutrient Intakes from Food Generally do Not Meet Dietary Reference Intakes among Adult Members of Pacific Northwest Tribal Nations. The Journal of Nutrition 140(5): 992–998. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.114629[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20237069]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittelsohn J, Jock B, Redmond L, Fleischhacker S, Eckmann T, Bleich SN, Loh H, Ogburn E, Gadhoke P, Swartz J, et al. 2017. OPREVENT2: Design of a Multi-Institutional Intervention for Obesity Control and Prevention for American Indian Adults. BMC Public Health 17(1): 105. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4018-0[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=oprevent2]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JF, Lin B, and Frazao E. 2002. Role of Food Prepared Away from Home in the American Diet, 1977–78 Versus 1994–96: Changes and Consequences. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 34(3): 140–150.[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12047838/]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern P 2007. Obesity and American Indians/Alaska Natives. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]

- HHS, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, USDA, Center for Nutrition Policy Promotion, U.S. Health and Human Services and Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee 2015. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020. Washington, D. C: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao P, Mitchell D, Coffman D, Craig Wood G, Hartman T, Still C, and Jensen G. 2013. Dietary Patterns and Relationship to Obesity-Related Health Outcomes and Mortality in Adults 75 Years of Age Or Greater. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 17(6): 566–572. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0014-y[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23732554]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service Division of Diabetes Treatment and Prevention. 2012. Diabetes in American Indians and Alaska Natives Facts at-a-Glance. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. 2010. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janette C, Horowitz R, Wilson R, Sava S, Sinnock P, and Gohdes D. 1989. Tribal Differences in Diabetes: Prevalence among American Indians in New Mexico. Public Health Reports (1974-) 104(6): 665–669.[http://www.jstor.org/stable/4628773]. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullany B, Neault N, Tsingine D, Powers J, Lovato V, Clitso L, Massey S, Talgo A, Speakman K, and Barlow A. 2013. Food Insecurity and Household Eating Patterns among Vulnerable American-Indian Families: Associations with Caregiver and Food Consumption Characteristics. Public Health Nutrition 16(4): 752–760. doi: 10.1017/S136898001200300X[https://search-proquest-com.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/docview/1314393293?accountid=11752]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2016. Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-Term Trends in Health. U.S. Center for Disease Control, Hyattsville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Dietary Supplements. 2018. Vitamin D Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Last Modified November 9, 2018. Accessed Dec 27, 2018 https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/. [Google Scholar]

- Rural-Urban Continuum Codes Documentation. Accessed Sep 22, 2019 https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/documentation/.

- Schell LM and Gallo MV. 2012. Overweight and Obesity among North American Indian Infants, Children, and Youth. American Journal of Human Biology : The Official Journal of the Human Biology Council 24(3): 302–313. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22257[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3514018/]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setiono FJ, Jock B, Trude A, Wensel CR, Poirier L, Pardilla M, and Gittelsohn J. 2019. Associations between Food Consumption Patterns and Chronic Diseases and Self- Reported Morbidities in Six Native American Communities. Current Developments in Nutrition 3(Supplement 2): 69–80. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzz067[https://academic.oup.com/cdn/article/3/Supplement_2/69/5511267?guestAccessKey=8f1abf1e-a12f-496d-b490-06f03747e4c9]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Yacavone M, Cao X, Pardilla M, Qi M, and Gittelsohn J. 2010. Dietary Intake and Development of a Quantitative FFQ for a Nutritional Intervention to Reduce the Risk of Chronic Disease in the Navajo Nation. Public Health Nutrition 13(3): 350–359. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009005266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ, Nelson RG, Hardy SA, Manahan EM, Bennett PH, and Knowler WC. 1996. Survey of the Diet of Pima Indians using Quantitative Food Frequency Assessment and 24-Hour Recall. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 96(8): 778–784. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00216-7[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002822396002167]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stang J, Zephier EM, Story M, Himes JH, Yeh JL, Welty T, and Howard BV. 2005. Dietary Intakes of Nutrients Thought to Modify Cardiovascular Risk from Three Groups of American Indians: The Strong Heart Dietary Study, Phase II. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 105(12): 1895–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stannard D 1992. American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. 2006. Strong Heart Family Study Cardiovascular Disease in American Indians (Phase V) Operations Manual. Oklahoma City: Accessed Sep 22, 2019 https://strongheartstudy.org/portals/1288/Assets/documents/manuals/Phase%20V%20Operations%20Manual.pdf?ver=2017-11-15-134617-657 [Google Scholar]

- The Office of Dietary Supplements. Nutrient Recommendations: Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI). Accessed Dec 2, 2017 https://ods.od.nih.gov/Health_Information/Dietary_Reference_Intakes.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FE and Subar AF. 2013. Dietary Assessment Methodology. In Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-391884-0.00001-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn A 2010. Understanding Lactose Intolerance. Clinician Reviews 20(11): 17[http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=55546439&site=ehost-live&scope=site]. [Google Scholar]

- Westerterp KR 2007. Determinants of Energy Expenditure and Energy Balance. Appetite 49(1): 339. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.03.213[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666307002541]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willett W 2012. Nutritional Epidemiology. 3rd ed ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yracheta JM, Lanaspa MA, Le MT, Abdelmalak MF, Alfonso J, Sánchez-Lozada LG, and Johnson RJ. 2015. Diabetes and Kidney Disease in American Indians: Potential Role of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 90(6): 813–823. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.03.018[https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(15)00268–2/fulltext]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.