Abstract

The relative safety of chronic exposure to electronic cigarette (e-cig) aerosol remains unclear in terms of lung pathogenesis. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate gene/protein biomarkers, which are associated with cigarette-induced pulmonary injury in animals chronically exposed to nicotine containing e-cig aerosol. C57BL/6J mice were randomly assigned to three exposure groups: e-cig, tobacco cigarette smoke, and filtered air. Lung tissues and/or paraffin embedded slides were used to evaluate gene and/or protein expressions of the CYP450 metabolism (CYP1A1, CYP2A5, and CYP3A11), oxidative stress (Nrf2, SOD1), epithelial-mesenchymal transition (E-cadherin and vimentin), lung pathogenesis (AhR), and survival/apoptotic pathways (p-AKT, BCL-XL, p53, p21, and CRM1). Expressions of E-cadherin and CRM1 were significantly decreased, while CYP1A1, AhR, SOD1 and BCL-XL were significantly upregulated in the e-cig group compared to the control (p<0.05). Nuclear sub-cellular localization of p53, evaluated by immunohistochemistry staining, in bronchiolar tissues was higher in the e-cig group (25.3±2.7%) as compared to controls (12.1±1.8%) (p<0.01). Although the biomarkers responses were not identical, in general, the responses had similar qualitative trends between the e-cig and cigarette groups. As these related molecular changes are involved in the pathogenesis of cigarette-induced lung injury, the possibility exists that e-cigs can produce a similar outcome. Although further investigation is warranted, e-cigs are unlikely to be considered as safe in terms of pulmonary health.

Keywords: Vaping, Smoking, Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis, Lung, Mouse

Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigs), also known as vapes, are purported to be a modified risk device with a stated aim to aid in smoking cessation (McNeil et al., 2015; Hyman and Brown, 2017). However regardless of their intended function, e-cig use is becoming increasingly popular both across the United States and world-wide (Cobb et al., 2010; Schoenborn and Gindi, 2015). As many as 4.5% of US adults use vaping devices daily, and of those individuals 51.2% are under the age of 35 (Schoenborn and Gindi, 2015). Perhaps more troublingly, many studies now indicate that the portion of e-cig users who were previously classified as “never-smokers” is increasing rapidly, and has been reported to be as high as 15% of all e-cig users (King et al., 2013; Polosa et al., 2017; Mirbolouk et al., 2018). Furthermore, studies estimate that up to 50% of all “vapers” classify themselves as dual users of both tobacco products and e-cig devices (Piper et al., 2019).

Despite the increasing incidence of e-cig use, little is known about the implications they may exert on the pulmonary health of e-cig users. The knowledge gap concerning their potential to damage the lungs is present, in part, due to the fact that all e-cig aerosols contain a widely variable mixture of at least some toxic chemicals (such as acetaldehyde, acetone, acrolein, formaldehyde, and even nicotine) with little to no industry regulation (Olfert et al., 2018). Current human e-cig exposure data are inadequate to allow conjecture about many long-term effects on pulmonary health. In order to better understand the potential of chronic e-cig exposure to contribute to pulmonary pathologies, we examined changes in gene and protein biomarkers involved in molecular pathways that have previously been implicated in cigarette smoking and the development of lung diseases (such as CYP450 metabolism, oxidative stress, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and survival/apoptotic pathways).

Cigarette smoke is known to generate excessive aromatic hydrocarbons and reactive oxidative species (ROS). Both of these molecule families represent important mechanisms for lung damage in chronic animal cigarette smoke exposure models (T. Harju, 2004; Vu et al., 2015). In order to quell these harmful chemicals, CYP1A1 and the related regulatory transcription factor aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) expressions are increased to diminish levels of harmful aryl hydrocarbons (Wu et al., 2009). Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), CYP2A5, and CYP3A1 are all upregulated by smoke-induced oxidative stress to mitigate cellular damage (Hoffmann et al., 2013; Lerner et al., 2016). Given mounting evidence that e-cigs also induce production of aromatic hydrocarbons and ROS (Cheng, 2014; Goel et al., 2015), it is likely the molecular biomarkers for these pathways will also be involved in e-cigarette aerosol exposure. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) has also been linked to cigarette exposure and lung pathogenesis. EMT is exhibited in cigarette smokers, and can be linked to nicotine, a highly addictive substance in some e-cigs and traditional cigarettes (Sanner and Grimsrud, 2015). EMT not only acts as a vital step for acquisition of malignant tumor phenotypes (resulting in cancer metastases), but also with lung tissue remodeling contributing to fibrosis, and airway/alveolar wall destruction (Zou et al., 2013). However, the ability for e-cigs to induce EMT in animal models remains unclear. Lastly, the cell survival and apoptotic pathways regulate a wide range of cellular processes that can be linked to smoking and the development of lung pathologies (Kuwano et al., 2000; Mizuno et al., 2015). The changes in the anti-apoptotic proteins p-AKT and B-cell lymphoma extra-large (BCL-XL), p53 and p21, and chromosome region maintenance 1 (CRM1) proteins all play a role in the development of chronic pulmonary diseases (Zhang et al., 2012). But again, the responses of these biomarkers following chronic e-cig exposure is poorly understood.

We hypothesize, if e-cigs are safe (or less-risky) compared to traditional cigarettes that many, if not all, of the biomarkers linked to smoking-related lung diseases would not respond in the same manner with chronic e-cig exposure. We expect that examining the changes in expression of biomarkers in animals chronically exposed to e-cig aerosol and cigarette smoke will help shed light on the potential for pulmonary damage given chronic e-cig exposure, and provide insight on the prospective molecular mechanisms related to e-cig induced harm.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Reagents

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Primary antibodies, AhR, CRM1 (A-7), CYP1A1(H-70), E-cadherin (H-108), p53 (Pab 1801), and SOD1 (11407); biotinylated secondary antibody; and Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Primary antibodies including, phospho-AKT (S473-D9E), BCL-XL (54H6), Nrf2 (D1Z9C), p21 (12D1), and GAPDH (D16H11-XP™) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). 10× Tris-buffered saline (TBS), 20× Tween, SYBR Green one step kits, and chemiluminescence kits were purchased from BIORAD laboratories (Hercules, CA). Diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) and avidin-biotin complex (ABC) kits were purchased from vector laboratories (Burlingame, CA). RT-PCR primers listed in Table 1 were purchased from Eurofins Scientific (Bellevue, OH).

Table 1.

PCR primers used for qRT-PCR

| Primers | Sequence 5’-3’ |

|---|---|

| CYP2A5-F | GTGCCCTTTTCCATTGGAAAAC |

| CYP2A5-R | GGTGCCTGTGTGGATTTGAAGT |

| CYP3A11-F | ATTCCTGGGCCCAAACCTCTGCCA |

| CYP3A11-R | TGGGTCTGTGACAGCAAGGAGAGGC |

| BCL-XL-F | AACATCCCAGCTTCACATAACCCC |

| BCL-XL-R | GCGACCCCAGTTTACTCCATCC |

| E-cadherin-F | CGGGAATGCAGTTGAGGATC |

| E-cadherin-R | AGGATGGTGTAAGCGATGGC |

| Vimentin-F | CTTGAACGGAAAGTGGAATCCT |

| Vimentin-R | GTCAGGCTTGGAAACGTCC |

| CRM1-F | AGCAGTCGTGCAACCTCC |

| CRM1-R | TCAAGGTGGGTTTCACAGTT |

Animals and Exposure Model

Lung tissue and paraffin embedded slides were obtained from animals reared and exposed for our previous study (Olfert et al., 2018). Briefly, 10-wk-old C57BL/6J mice (n=45) were randomly assigned to groups: e-cig aerosol (18 mg/mL nicotine) (n=15), 3R4F reference cigarette smoke (n=15), or filtered air as a control (n=15). Exposures started at 13–14 weeks of age and continued for 8 successive months. Terminal surgical procedures were conducted at 12 months of age, which mimicked 35-year-old humans with 20+ exposure (assuming a 78-year lifespan for humans and a 2-year lifespan for mice).

Cigarette exposure models have established that a minimum of 6 months exposure is generally required to elicit significant cigarette smoke-induced structural lung damage/destruction. Similar data from long-term exposure with respect to vaping electronic cigarettes are lacking, so we selected an 8-month exposure to ensure we beyond the minimum exposure time frame. Given that smoking creates a significant burden to the lung via production of aerosol particulate matter, we also designed the inhalation exposure paradigm to ensure the same puffing topology and measured/matched the same overall total particulate matter (TPM) exposure between the cigarette and e-cig groups (Olfert et al., 2018). Thus, the biological effects we would observe would be normalized for aerosol particular matter.

Western Blotting

Western Blotting procedures followed a protocol which our lab has used in the past (Zhu et al., 2014). Briefly, the tissues (Control n=7; E-cig, n=5; Cigarette, n=6) were homogenized in RIPA buffer on ice with an ultrasonic sonicator and then centrifuged to collect the supernatant. After protein quantification, 100μg of total protein for each sample were separated by gel electrophoresis on a 4–12% SDS polyacrylamide gel. Signals were exposed via BIORAD ChemiDoc. Relative densitometric digital analysis of protein bands for each sample were determined utilizing Image-J Software and normalized to the intensity of GAPDH.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from portions of whole lung tissue according to our previously published protocols (Chen et al., 2011). An iTaq Universal SYBR green One-step kit was used for amplification of total RNA (75ng). The Ct values of our genes of interest were normalized to the Ct value of GAPDH within the same sample. Fold change of gene expression were calculated via the ΔΔCt method. Reactions for each sample were done in duplicate, and a non-template control was included in each PCR run.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining

Immunohistochemical and H&E staining techniques and protocols were similar to those conducted previously by our lab (Chen et al., 2011). IHC for SOD1 was probed in order to qualitatively corroborate the Western blot findings. Quantitative analysis for subcellular localization of IHC staining for p53 was also performed. Five areas containing ~100 cells/area were obtained from each animal. The areas were then analyzed for total cell number, and cells in which the nuclear staining of p53 was equal to or exceeded the cytoplasmic staining (N≥C). The proportion of N≥C was then determined by: .

Statistical analysis

Analysis of protein expression, gene expression, and IHC results were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD post hoc test. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism8 software. Differences with a p-value ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

CYP450 Family and Oxidative Stress

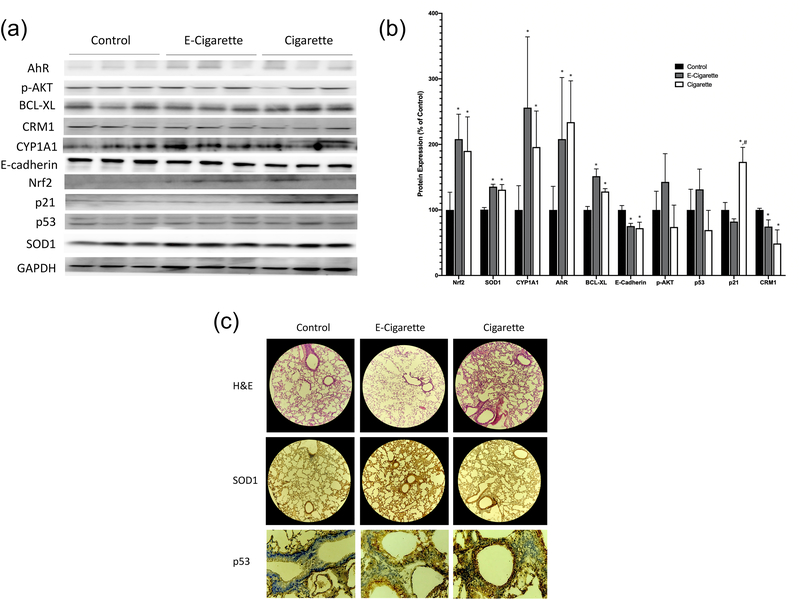

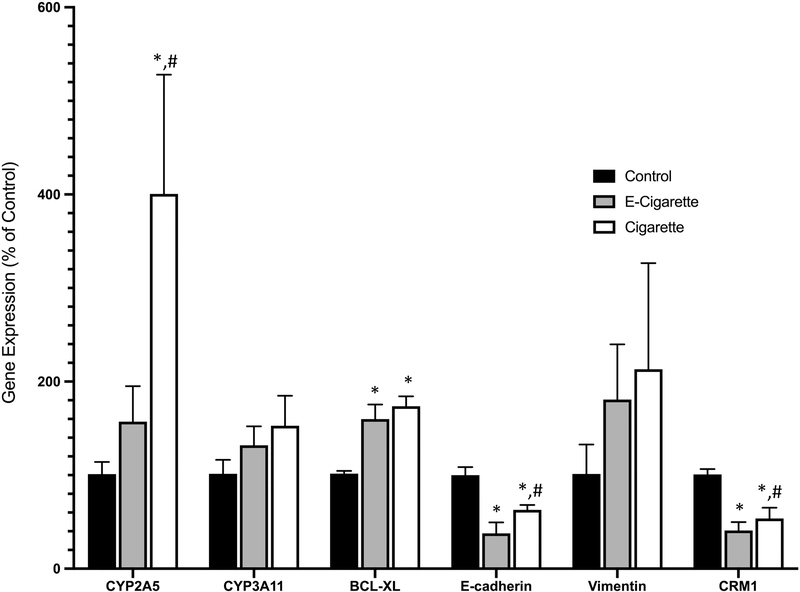

CYP1A1 protein expression was significantly increased in both the e-cig group (256±108%) and the cigarette group (196±55%) as compared to the control group (100±37%) (p<0.05, Figure 1). The mRNA expression of CYP2A5 was found to be significantly increased in the cigarette group (400±127%) as compared with e-cig (157±38%) and control groups (Figure 2). The difference between the e-cig and control groups was marginally significant (p=0.067). In addition, there were no significant changes seen in the expression of CYP3A11 (Figure 2). AhR protein expression was significantly increased in both the e-cig group (208±94%) and the cigarette group (234±63%) as compared to the control group (100±36%) (p<0.05, Figure 1). Nrf2 protein expression was significantly increased in both the e-cig group (208±38%) and the cigarette group (190±52%) as compared to the control group (100±27%) (p<0.05, Figure 1). SOD1 protein expression was upregulated in both the e-cig (135±3%) and cigarette (130±7%) groups as compared to the control (p<0.05, Figure 1), which was further confirmed by IHC (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

The protein expressions of Nrf2, SOD1, CYP1A1, AhR, BCL-XL, E-Cadherin, p-AKT, p53, p21, and CRM1 after cigarette smoke and e-cigarette aerosol exposure. (A) Western Blot bands for all target proteins. Bands are representative of their group, and any reassembly of lanes were demarcated by vertical black lines. (B) The relative protein intensities of target proteins, normalized by intensity of GAPDH as compared to controls. (C) H&E staining (10×) and IHC staining of SOD1 (10×) and p53 (40×) from paraffinized lung tissues representing the control, E-cigarette, and cigarette groups. Data represent the means ± SD. Values bearing “*” indicate significant difference as compared with the control and those labeled “#” denote a significant difference when compared with the e-cig group (Control, n=7; E-cig, n=5; Cigarette, n=6).

Figure 2.

The gene expression of CYP2A5, CYP3A11, BCL-XL, E-cadherin, Vimentin, and CRM1 after cigarette smoke and e-cigarette aerosol exposure compared to controls. Data represent the means ± SD. Values bearing “*” indicate significant difference as compared with the control and those labeled “#” denote a significant difference when compared with the e-cig group (Control, n=7; E-cig, n=5; Cigarette, n=6).

EMT

The protein expression of the cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin was significantly downregulated in the cigarette (72±9%) and e-cig groups (75±4%) compared with the control (p<0.05, Figure 1). These results were further confirmed by data generated via qRT-PCR which also exhibited significantly decreased mRNA expression of E-cadherin in both exposure groups as compared to the control group (e-cig 37±11% and cigarette 62±5%, p<0.05, Figure 2). No significant changes of the mRNA expression of vimentin was observed in any group.

Cell Survival and Apoptosis

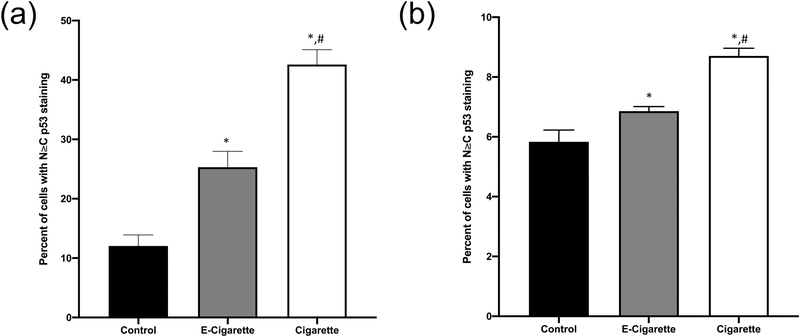

There were no significant differences observed in the activated anti-apoptotic protein p-AKT (Figure 1). Significant increases in the expression of anti-apoptotic protein BCL-XL were detected in both the cigarette (128±4%) and the e-cig (151±11%) groups as compared to the control group (p<0.05, Figure 1). These data were also confirmed by qRT-PCR analyses (e-cig 159±15%, and cigarette 173±10%, Figure 2). Total protein expression of p53 was not significantly different amongst all groups (Figure 1). However, as shown in Figures 1C and 3, subcellular nuclear localization of p53 was significantly elevated in both of the exposure groups for both alveolar cells (cigarette 8.8±0.3%, and e-cig 6.9±0.1%) and bronchiolar cells (cigarette 42.6±2.5%, and e-cig 25.3±2.7%), as compared to the control group (alveolar 5.8±0.4%, and bronchiolar 12.1±1.8%) (p<0.05). The cigarette group had the highest value for N=C p53 staining in both cell types. The cyclin associated cell cycle arrest protein, p21 was not significantly different in the e-cig group (82±4%), yet significantly increased in the cigarette group (173±22%) as compared to the control (p<0.05, Figure 1). CRM1 is a primary nuclear export protein involved in shuttling both p53 and p21 out of the nucleus. CRM1 was found to be significantly decreased in both of the exposure groups (cigarette 48±20%, and e-cig 74±10%) as compared to the control group (p<0.05, Figure 1), also shown by the results of qRT-PCR (cigarette 53±11%, and e-cig 41±8%, p<0.05, Figure 2).

Figure 3.

The nuclear accumulation of p53 after cigarette smoke and e-cigarette aerosol exposure. Paraffin-embedded lung tissues were sectioned at 5μm. IHC was performed, using DAB as a stain and hematoxylin as a counterstain. Approximately 2500 cells per control and exposure group were counted. (A) The proportion of bronchiolar cells with p53 staining N≥C. (B) The proportion of alveolar cells with p53 staining N≥C. Data represent the means ± SD. Values bearing “*” indicate significant difference as compared with the control and those labeled “#” denote a significant difference when compared with the e-cig group (Control, n=7; E-cig, n=5; Cigarette, n=6).

Discussion

Our study indicates that while the changes seen in the molecular biomarkers of lung injury we evaluated were not identical, we did observe a qualitatively similar trend, between chronic cigarette smoke and e-cig aerosol exposed mice. For instance, the majority of the biomarkers that we identified had no significant difference between the exposure groups despite both being significantly different from the controls. However, CYP2A5 and p21 were very responsive to cigarette smoke, but not in the e-cig group as compared to controls. Given that these biomarkers are known to be associated with lung damage from chronic smoking, it should not be assumed that vaping is safe in respect to lung health.

Recent studies have shown that activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway and the downstream mitigators of oxidative stress, such as SOD1 and SOD2, play a role in pulmonary sequela induced by long-term cigarette smoke (Rangasamy et al., 2004; Hoffmann et al., 2013; Mercado et al., 2015). It is thought that smoking increases the nuclear uptake of Nrf2 and through its action as a transcription factor, upregulates SOD2, and potentially SOD1, to help prevent damage and/or further injury to the central bronchial epithelium or alveolar epithelium in smokers with or without COPD (T. Harju, 2004; Hübner et al., 2009). Lately, animal studies have also found evidence of oxidative stress in lung tissues following acute e-cig exposure (Sussan et al., 2015). Here, we find that Nrf2 and SOD1 protein expression were equally increased in both cigarette and e-cig exposed groups of our study compared controls. This leads to the inference that to some extent, damaging oxidative cellular stress is present in both exposure groups. The hydroxylation activities and expression of CYP2A5 too, indicates increased oxidative stress, but also implicates the metabolism of nicotine, cotinine, lipopolysaccharides, and nitrosamines found with tobacco smoke and nicotine containing compounds (Zhou et al., 2010; Willis et al., 2014). Additionally, increased expression of hepatic CYP2A5 has been shown to correlate organ system toxicity induced by gutkha, a smokeless Indian cigarette (Willis et al., 2014). Furthermore, when the functions of most other CYP enzymes are compromised, it has been found that mouse CYP2A5 (also known as human CYP2A6) is induced with lung and liver injury (Zhou et al., 2010). Thus, the marked increase in mRNA expression of CYP2A5 in the cigarette group is likely a physiologic response aimed at mounting a response against lung damage/disease. A similar trend, albeit a much lower response, was also seen in the e-cig exposed mice. Finally, AhR and CYP1A1 activity have both been implicated in the development of lung disease and cigarette smoke (Wang et al., 2015; Rogers et al., 2017). The mechanism of AhR signaling and the subsequent increase in CYP1A1 expression is important for reducing damage from aromatic hydrocarbons in cigarette smoke exposure. Thus, the increase in expression of these two proteins seen in the e-cig exposed group indicates there is potential for cellular damage from aromatic hydrocarbons derived from e-cig aerosol as well. Given the similarities we observed in these oxidative stress and aryl hydrocarbon biomarkers in mice with chronic exposure to either cigarette smoke or e-cig aerosol, these data suggest the cellular environment produce by e-cigs aerosol is as potentially pathognomonic as cigarette smoke exposure. Research aimed at exploring further CYP450 metabolism mechanisms and expanded oxidative stress pathways linked to a chemical analysis of e-cig aerosol merits further study.

Changes in EMT related biomolecules have also been noted in the development of lung diseases by many previous studies (Sohal and Walters, 2013). For example, it has been reported that EMT, including increases in vimentin and decreases in E-cadherin, was involved in patients with lung injuries such as COPD induced by cigarette smoke (Milara et al., 2013). The results of our study indicate that there are similar EMT changes occurring in chronic e-cig exposure that are seen in cigarette smoke and acute e-cig exposure (Figure 2). While we did not observe a significant change in the expression of vimentin in either of the exposure groups, E-cadherin was significantly decreased in both the e-cig and cigarette groups and matched the trend shown in the aforementioned studies. This leads us to believe that the ability for epithelial cells to become mesenchymal and contribute to pulmonary disease exists with exposure to e-cig aerosol.

Apoptosis is a tightly regulated cellular process that can induce and/or exacerbate many disease processes including pulmonary disease. BCL-XL and p-AKT are two molecules that can influence the normal course of apoptosis. Increases in both BCL-XL and p-AKT have both been shown by previous studies to contribute to the progression of lung disease by the inhibition of apoptosis (Drakopanagiotakis et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2016). BCL-XL and p-AKT may also be linked to EMT, independent of their respective anti-apoptotic activity (Choi et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). However, we found that only BCL-XL, and not p-AKT, was significantly increased in both chronic exposure groups compared to controls. This suggests that at least BCL-XL may induce anti-apoptotic proliferation and aid in developing pulmonary disease in response to e-cig use.

Significant changes were also observed in the p53 pathway of animals exposed to e-cig aerosol and cigarette smoke in our study. One prominent p53 cascade implicated in lung disease involves p53 transcriptional modification and interaction with cyclin/p21 to induce G1-S phase cell cycle arrest (Abbas and Dutta, 2009). Both of these molecules and their actions rely on the activity of the nuclear export protein CRM1, which is a major mammalian export protein that enables large macromolecules (such as p53 and p21) to be transported between the nucleus to the cytoplasm (Chen et al., 2011). Together, these biomarkers have all been identified as contributory factors of pulmonary diseases linked to cigarette smoking (Korthagen, 2011). However, like the other biomarkers mentioned before, these responses yet to be studied in a chronic e-cig model. Our data shows that there is a significant difference in the subcellular localization of the protein, especially in the bronchiolar cells which are directly exposed to e-cig aerosol and cigarette smoke. We found that nuclear p53 is highest in the cigarette group, yet it is still significantly elevated in the e-cig group as compared to the control group with a significant difference between all groups. Thus, indicating that the p53 is likely being retained and active in the nucleus prospectively indicating cellular damage from cytotoxic stress in animals exposed to e-cig aerosol. Furthermore, CRM1 protein expression in the three groups inversely correlate with the subcellular p53 data in both the alveolar and bronchiolar. Thus, p53 and p21 are allowed to accumulate in the nucleus and remain active. The significant increase of p21 in cigarette group indicates that, under this circumstance, the lung tissue is relying in part on the G1 arrest pathway to avoid cellular damage and disease development. As for the e-cig group, we have determined that there are differences in the activity of p53, however further investigation is needed to determine if there are any changes to downstream proteins other than p21.

Additionally, we probed the animal serum for pro-inflammatory cytokines using a multiplex assay kit from meso scale diagnostics (data not shown). The 10 cytokines analyzed include granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF); interferon gamma (IFN-γ); vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF); tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α); and interleukins 1β, 4, 5, 6, 10, and 15. Due to the high variation in the samples, we observed insignificant trends of increased TNF-α and IL6 in both the e-cigarette and cigarette groups. Therefore, future efforts should be devoted to determining if there are any real appreciable different levels of serum pro-inflammatory cytokines after chronic e-cigarette exposure.

Lastly, a histopathological analysis of the lung tissues was conducted and previously reported (Olfert et al, 2018). Criteria examined were acute inflammation, chronic inflammation, emphysematous changes, alveolar macrophage infiltration, pigmented macrophages, goblet cell hyperplasia of bronchi, arterial pulmonary hypertension, smooth muscle hyperplasia of the mainstem bronchus, fibrosis, and percent of brown fat out of total fat content. There was no significant change in cumulative histopathology score between the control (2.4±0.90) and e-cig groups (2.4±0.97). However, there was a significant increase in histopathological scoring observed in cigarette group (6.8±3.54). Additionally, as reported in this same study, there were similar number of animals lost across all groups (including the air-exposed control). Necropsy of lost animals did not show evidence of overt lung damage, therefore it seems unlikely that the exposure was the primary cause of death in the animals lost before completion of the study. Our results from the present study suggest that molecular alterations might be more sensitive than histopathological changes. Future investigation should be done to examine the true relationship between lung histopathological changes and chronic e-cig exposure in terms of exposure route, time, and dosage.

There are some limitations associated with our study. Primarily, all e-cig devices vary in concentrations of nicotine and other toxins, making generalizations from any one-device e-cig study difficult. We also did not measure chemical composition of the e-cig aerosol generated in our study, and therefore inferences cannot be made with respect to any causative agents. Additionally, we only used an e-cig liquid containing nicotine, so we cannot determine if any the observed responses are due to nicotine or other constituents in the e-cig aerosol cloud. However, it is worth noting that vaping without nicotine, has shown similar changes on cardiovascular responses as smoking or vaping with nicotine (Franzen et al., 2018). Moreover, a systematic genomic and proteomic analyses of mouse tissues chronically exposed to e-cig aerosol will likely facilitate the identification of potential unrecognized biomarkers involved in pathogenesis of pulmonary diseases. Such methods include high-throughput gene microarrays or two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis. Additional research, including studies of primary human pulmonary epithelial cells exposed to e-cig in air-liquid interface cell exposure system, will also be required to more precisely elucidate the toxicity associated with e-cigs.

In summary, we observed that changes in lung biomarker molecules, from a multitude of biological cascades associated with lung injury and disease, are qualitatively similar between chronic e-cig and cigarette exposure in mice. While there are some differences between individual molecules, broadly the changes in biomarkers observed in chronic e-cig aerosol exposure were found to follow those seen in chronic cigarette smoke exposure. Because these biomarkers have been shown to contribute significantly to the development of cigarette-induced lung diseases, our study indicates that chronic e-cig exposure has the potential to initiate pathologic processes that are known to contribute to chronic lung damage/diseases.

E-cigarette exposure results in molecular biomarker alterations linked to lung injury

Chronic vaping has the potential to produce similar pathological pathways as smoking

E-cigarette use may not be a safe alternative to cigarette smoking

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to Dr. Eiman Aboaziza, Mr. Matthew Breit, Ms. Hannah Hoskinson, Ms. Mireia Fabrega, Ms. Morgan Pelley, Mr. Richard Nolan and Mr. Gregory Ede, for their help in conducting the daily exposure.

Dr. Weimin Gao was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number NIH R15ES026789. Dr. I. Mark Olfert was supported by the West Virginia University/Marshall University Health Cooperative Initiative Award; with additional support from NIH P20GM103434 (West Virginia IDeA Network for Biomedical Research Excellence), and NIH U54GM104942 (West Virginia Clinical Translational Science Institute). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbas T, Dutta A, 2009. P21 in cancer: Intricate networks and multiple activities. Nature Reviews Cancer 9, 400–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Moore JE, Samathanam C, Shao C, Cobos E, Miller MS, Gao W, 2011. CRM1-dependent p53 nuclear accumulation in lung lesions of a bitransgenic mouse lung tumor model. Oncology Reports 26, 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T.J. T. c, 2014. Chemical evaluation of electronic cigarettes. Tobacco control 23, ii11–ii17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Chen Z, Tang L, Fang Y, Shin S, Panarelli N, Cheny Li Y, Jiang X, Du Y, 2016. Bcl-xL promotes metastasis independent of its anti-apoptotic activity. Nature Communications 7, 10384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb NK, Byron MJ, Abrams DB, Shields PG, 2010. Novel nicotine delivery systems and public health: the rise of the "e-cigarette". American journal of public health 100, 2340–2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakopanagiotakis F, Xifteri A, Polychronopoulos V, Bouros D, 2008. Apoptosis in lung injury and fibrosis. European Respiratory Journal 32, 1631–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzen KF, Willig J, Cayo Talavera S, Meusel M, Sayk F, Reppel M, Dalhoff K, Mortensen K, Droemann D, 2018. E-cigarettes and cigarettes worsen peripheral and central hemodynamics as well as arterial stiffness: A randomized, double-blinded pilot study. Vascular Medicine (United Kingdom) 23, 419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel R, Durand E, Trushin N, Prokopczyk B, Foulds J, Elias RJ, Richie J P J C.r.i.t Jr, 2015. Highly reactive free radicals in electronic cigarette aerosols. Chem Res Toxicol 28, 1675–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann RF, Zarrintan S, Brandenburg SM, Kol A, de Bruin HG, Jafari S, Dijk F, Kalicharan D, Kelders M, Gosker HR, ten Hacken NHT, van der Want JJ, van Oosterhout AJM, Heijink IH, 2013. Prolonged cigarette smoke exposure alters mitochondrial structure and function in airway epithelial cells. Respiratory Research 14, 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübner R-H, Schwartz JD, De BP, Ferris B, Omberg L, Mezey JG, Hackett NR, Crystal RG, 2009. Coordinate control of expression of Nrf2-modulated genes in the human small airway epithelium is highly responsive to cigarette smoking. Mol Med 15, 203–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman W, Brown S, 2017. E-cigarettes and Vaping: Risk Reduction and Risk Prevention. Texas Public Health Journal 69, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- King B, Alam S, Promoff G, Arrazola R, Dube S, 2013. Awareness and ever-use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010–2011. Nicotine and Tobacco Research 15, 1623–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthagen N, van Moorsel C, Kazemier K, & Grutters J, 2011. Association between polymorphisms in the P53 and P21 genes and IPF. European Respiratory Journal 38, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwano K, Hagimoto N, Tanaka T, Kawasaki M, Kunitake R, Miyazaki H, Kaneko Y, Matsuba T, Maeyama T, Hara N, 2000. Expression of apoptosis-regulatory genes in epithelial cells in pulmonary fibrosis in mice. The Journal of Pathology 190, 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner CA, Rutagarama P, Ahmad T, Sundar IK, Elder A, Rahman I, 2016. Electronic cigarette aerosols and copper nanoparticles induce mitochondrial stress and promote DNA fragmentation in lung fibroblasts. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 477, 620–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil A, Brose L, Calder R, Hitchman S, Hajek P, McRobbie H, 2015. E-cigarettes: an evidence update. A report commissioned by Public Health England. Public Health England 111. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado N, Ito K, Barnes PJ, 2015. Accelerated ageing of the lung in COPD: new concepts. Thorax 70, 482–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milara J, Peiró T, Serrano A, Cortijo J, 2013. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition is increased in patients with COPD and induced by cigarette smoke. Thorax 68, 410–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirbolouk M, Charkhchi P, Kianoush S, Uddin I, Orimoloye O, Jaber R, Bhatnagar A, Benjamin E, Hall M, DeFilippis A, Maziak W, Nasir K, Blaha M, 2018. Prevalence and distribution of e-cigarette use among US adults: behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2016. Annals of Internal Medicine 169, 429–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno S, Bogaard H, Ishizaki T, Toga H, 2015. Role of p53 in lung tissue remodeling. World Journal of Respirology 5, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Olfert IM, De Vallance E, Hoskinson H, Branyan KW, Clayton S, Pitzer CR, Sullivan DP, Breit MJ, Wu Z, Klinkhachorn P, Mandler WK, Erdreich BH, Ducatman BS, Bryner RW, Dasgupta P, Chantler PD, 2018. Chronic exposure to electronic cigarettes results in impaired cardiovascular function in mice. Journal of Applied Physiology 124, 573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper M, Baker T, Benowitz N, Jorenby D, 2019. Changes in Use Patterns Over 1 Year Among Smokers and Dual Users of Combustible and Electronic Cigarettes. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polosa R, Cibella F, Caponnetto P, Maglia M, Prosperini U, Russo C, Tashkin D, 2017. Health impact of E-cigarettes: A prospective 3.5-year study of regular daily users who have never smoked. Scientific Reports 7, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, Zhen L, Srisuma SS, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Petrache I, Tuder RM, Biswal S, 2004. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke–induced emphysema in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 114, 1248–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S, De Souza AR, Zago M, Iu M, Guerrina N, Gomez A, Matthews J, Baglole CJ, 2017. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-dependent regulation of pulmonary miRNA by chronic cigarette smoke exposure. Scientific reports 7, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanner T, Grimsrud TK, 2015. Nicotine: Carcinogenicity and effects on response to cancer treatment a review. Frontiers in Oncology 5, 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn C, Gindi R, 2015. Electronic cigarette use among adults: United States, 2014. 2014, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal S, Walters E, 2013. Role of epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Respiratory Research 14, 120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussan TE, Gajghate S, Thimmulappa RK, Ma J, Kim JH, Sudini K, Consolini N, Cormier SA, Lomnicki S, Hasan F, Pekosz A, Biswal S, 2015. Exposure to electronic cigarettes impairs pulmonary anti-bacterial and anti-viral defenses in a mouse model. PLoS ONE 10, e0116861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- T. Harju RK-W, Sirviö R, Pääkkö P, Crapo JD, Oury TD, Soini Y, Kinnula VL, 2004. Manganese superoxide dismutase is increased in the airways of smokers' lungs. European Respiratory Journal 24, 765–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu AT, Taylor KM, Holman MR, Ding YS, Hearn B, Watson CH, 2015. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the mainstream smoke of popular US cigarettes. Chem Res Toxicol 28, 1616–1626.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C-D, Chen N, Huang L, Wang J-R, Chen Z-Y, Jiang Y-M, He Y-Z, Ji Y.-L J B.r.i., 2015. Impact of CYP1A1 polymorphisms on susceptibility to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis DN, Popovech MA, Gany F, Hoffman C, Blum JL, Zelikoff JT, 2014. Toxicity of Gutkha, a Smokeless Tobacco Product Gone Global: Is There More to the Toxicity than Nicotine? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11, 919–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J-P, Chang LW, Yao H-T, Chang H, Tsai H-T, Tsai M-H, Yeh T-K, Lin P, 2009. Involvement of oxidative stress and activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in elevation of CYP1A1 expression and activity in lung cells and tissues by arsenic: an in vitro and in vivo study. Toxicological sciences 107, 385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, He J, Xia J, Chen Z, Chen X, 2012. Delayed apoptosis by neutrophils from COPD patients is associated with altered bak, bcl-xl, and mcl-1 mRNA expression. Diagnostic Pathology 7, 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XL, Xing RG, Chen L, Liu CR, Miao ZG, 2016. PI3K/Akt signaling is involved in the pathogenesis of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Molecular Medicine Reports 14, 5699–5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Zhuo X, Xie F, Kluetzman K, Shu Y, Ding X, 2010. Role of CYP2A5 in the Clearance of Nicotine and Cotinine: Insights from Studies on a Cyp2a5-null Mouse Model. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 332, 578–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Cromie MM, Cai Q, Lv T, Singh K, Gao W, 2014. Curcumin and vitamin E protect against adverse effects of benzo[a]pyrene in lung epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 9, e92992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W, Zou Y, Zhao Z, Li B, Ran P, 2013. Nicotine-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition via Wnt/-catenin signaling in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 304, 199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]