Abstract

Intimate relationship functioning depends upon the ability to accommodate one’s partner and to inhibit retaliatory and aggressive impulses when disagreements arise. However, accommodation and inhibition may be difficult when self-control strength is weak or depleted by prior exertion of self-control. The present study considered whether state self-control depletion prospectively predicts male and female self-reports of anger with partner and arguing with partner. Consistent with the I3 Model (Finkel, 2014), we also considered whether the association between elevated anger and arguing (i.e., instigation) and partner aggression was stronger when state self-control (i.e., inhibition) was depleted or among people high in negative urgency. In this ecological momentary assessment (EMA) study, heavy drinking married and cohabiting heterosexual couples (N=191) responded to 3 randomly signaled reports each day for 30 days. Depletion predicted anger and arguing with partner both cross-sectionally and prospectively for men and women. However, after controlling for prior levels of anger and arguing, these effects were diminished and supplemental analyses revealed that anger and arguing with partner predicted subsequent depletion. Specific to aggression, anger and arguing were strongly associated with concurrent reports of partner aggression perpetration and victimization (verbal and/or physical). However, neither state self-control depletion nor negative urgency moderated these effects. Overall, results suggest a modest impact of depletion on daily couple functioning as well as a potential cyclical effect of arguing on depletion.

Keywords: self-control, aggression, anger, ecological momentary assessment, sexual partners, self-report, impulsive behavior

Intimate partnerships offer numerous opportunities for joy, connection, and support, but also for anger, provocation, and irritation. Relationship functioning depends upon the ability to accommodate one’s partner and to inhibit retaliatory and aggressive impulses, efforts that require self-control. According to the self-control strength model (Baumeister, Vohs, & Tice, 2007; Muraven & Baumeister, 2000), when state self-control strength is weak or depleted by prior self-control efforts, it is difficult to exert additional self-control in the face of new demands. Within an intimate relationship, depleted self-control may impair the ability to accommodate one’s partner when disagreements arise and to inhibit impulses (e.g., to yell or swear). The present study used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) within a study of intimate couples to examine whether depleted state self-control strength prospectively predicts anger toward partner and arguing with partner over the next few hours. We also considered whether the relationship between anger and arguing and subsequent perpetration of aggression toward partner is moderated by either state self-control depletion or by negative urgency, a trait representing difficulty inhibiting impulses when experiencing negative affect.

Self-Control and Intimate Relationship Functioning

Even within a well-functioning intimate relationship, it is inevitable that disagreements will arise, and that partners will sometimes behave in an inconsiderate or less than thoughtful manner toward each other. Retaliating in response to these provocations can lead to escalating conflict and have negative consequences for the relationship. However, inhibiting the urge to retaliate requires self-control. Self-control has been defined as “the capacity for altering one’s own responses…to support the pursuit of long-term goals” (Baumeister, Vohs, & Tice, 2007, p. 351). Conversely, impulsivity is the tendency to select a stimulus-evoked response rather than a response that considers future consequences (Nigg, 2017). People with low trait self-control are more likely to act on impulses (Friese & Hofmann, 2009). For example, when faced with a disagreement with one’s partner, a person low in trait self-control (or high in impulsivity) is less likely than one high in self-control to accommodate the partner (Gomillion, Lamarche, Murray, & Harris, 2014) and more likely to express anger (Blake, Hopkins, Sprunger, Eckhardt, & Denson, 2018). Low trait self-control and high trait impulsivity have been associated with higher levels of intimate partner aggression in survey (Baker, Klipfel, & van Dulmen, 2018; Finkel, DeWall, Slotter, Oaten, & Foshee, 2009), laboratory analog (Blake, Hopkins, Sprunger, Eckhardt, & Denson, 2018; Scott, DiLillo, Maldonado, & Watkins, 2015), and daily report studies (Stappenbeck, Gulati, & Fromme, 2016). Partner aggression is particularly likely to occur in couples in which both partners have low dispositional self-control (Quigley et al., 2018).

The ability to inhibit a response also depends on state self-control strength, which fluctuates over time in response to momentary demands. Under most circumstances, self-control strength is sufficient to overcome urges that arise in daily life (e.g., to eat; Hofmann, Baumeister, Forster, & Vohs, 2012). However, exerting self-control to inhibit urges earlier in the day impairs the ability to resist desires later in the day (Hofmann, Vohs, & Baumeister, 2012). Depleted self-control contributes to impairment in social interaction (e.g., Vohs, Baumeister, & Ciarocco, 2005). Experimental studies demonstrate that after completing a depleting laboratory task, participants display more aggression toward another person in response to provocation (DeWall, Baumeister, Stillman, & Gailliot, 2007; DeWall, Finkel, & Denson, 2011; Osgood & Muraven, 2016; Stucke & Baumeister, 2006). Specific to intimate relationships, depleted participants were less likely to accommodate their partner (Finkel & Campbell, 2001) and more likely to aggress toward their partner following provocation (Finkel et al., 2009) compared with participants who had not been depleted by laboratory tasks.

Self-Control and Intimate Relationship Functioning in Daily Life

Recent reviews and replications have cast some doubt on the reliability and interpretation of the depletion effect as demonstrated by experimental studies (Carter, Kofler, Forster, & McCullough, 2015; Hagger & Chatzisarantis, 2016). One way to move beyond this controversy is to consider the real-world implications of depletion (Friese, Loschelder, Gieseler, Frankenbach, & Inzlicht, 2019). Few studies to date have examined depletion in naturalistic contexts and to our knowledge, just two have considered the effects of depletion on relationship functioning or aggression.

In one such study, Buck and Neff (2012) hypothesized that experiencing stressful events would hinder daily relationship functioning by interfering with the capacity to exert self-control. In a 14-day diary study of newlywed couples, they found that both men and women reported more negative behaviors toward their partners (e.g., showed anger toward spouse; criticized/blamed spouse) on days in which they experienced more stressors than usual. In itself this would not support the self-control strength model; however, indirect effects models showed that the effect of stress on the expression of negative behaviors was mediated via self-reported depletion (e.g., “I exerted a lot of willpower to get through the workday”, “I felt tired”; Finkel & Campbell, 2001). Depletion was not associated with positive behaviors toward spouse. Thus, consistent with theory, depletion did not impact all relationship behaviors, but rather was specific to the regulation of negative, arguably aggressive behaviors.

Crane, Testa, Derrick, and Leonard (2014) also considered whether each partner’s daily level of self-control depletion was positively related to partner-specific anger and arguing on that day. Using the Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM), Crane and colleagues considered the effects of one’s own (Actor) depletion as well as the effects of the partner’s depletion. A depleted partner may behave in a more provocative or irritable manner, contributing to arguing and anger in the other. On days in which one’s own self-reported level of depletion (“stressed” and “overwhelmed”) was higher than one’s own average, both men and women reported more arguing with partner, an effect that was exacerbated on days of high partner depletion. In analyses of partner-specific anger, there was also a significant A x P depletion effect as well as independent Actor and Partner depletion effects.

These two studies provide preliminary evidence that state self-control strength influences daily relationship functioning; however, both studies were limited by their use of once-daily reports in which depletion and daily relationship functioning were measured at the same time. Although both studies tested the theoretically-derived hypothesis that depletion predicts relationship outcomes, temporal ordering cannot be established with once-daily assessments. Depletion may be a consequence of arguments rather than the reverse. In a recent EMA study, interpersonal conflicts predicted subsequent depletion (Baumeister, Wright, & Carreon, 2019), presumably because people exert self-control to manage anger and inhibit aggressive responses during a conflict or argument. Hence, properly examining the impact of state self-control depletion on subsequent relationship functioning requires more frequent measurement intervals and consideration of the temporal ordering of independent and dependent variables.

Partner Aggression and Self-Control within the I3 Model

The self-control strength model fits well within the I3 Model, a meta-theory in which partner aggression is viewed as a failure of self-regulation (Finkel, 2014; Finkel et al., 2009). According to this influential theory, aggression is a function of three processes: impellance (dispositional tendency toward aggression), instigation (e.g., provocation), and (lack of) inhibition. Aggression is most likely to occur when there is a “Perfect Storm” of high impellance, high instigation, and low inhibition. It is common for partners to accommodate each other in disagreements and to inhibit acting on their aggressive urges (Finkel & Campbell, 2001; Finkel et al., 2009). Indeed, people are more likely to experience aggressive impulses when provoked by their partner than they are to act on those impulses (Finkel et al., 2009). However, the ability to inhibit aggressive urges when provoked is impaired when self-control strength is depleted through an experimental task (Barlett, Oliphant, Gregory, & Jones, 2016; DeWall et al., 2011; Finkel et al., 2009), providing support for predictions derived from the I3 model. To our knowledge no naturalistic studies have considered whether partner aggression following provocation is more likely when state self-control is depleted.

According to the I3 Model (Finkel, 2014), those who are chronically low in inhibition strength (e.g., low trait self-control, high impulsivity) are more likely to aggress following provocation than those with better inhibitory strength. A recent experimental study provides support for this hypothesis (Subramani, Parrott, Latzman, & Washburn, 2018). Within the context of daily relationship functioning, trait negative urgency seems particularly relevant to understanding the ability to exert self-control when arguing with or provoked by partner. Negative urgency is the tendency to act impulsively when experiencing negative affect (Cyders & Smith, 2008; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Individuals high in negative urgency are more reactive to stressful situations (Owens, Amlung, Stojek, & MacKillop, 2018), more likely to display reactive aggression (Gagnon & Rochat, 2017; Hecht & Latzman, 2015), and more likely to perpetrate physical aggression toward their intimate partners (Derefinko, DeWall, Metze, Walsh, & Lynam, 2011; Leone, Crane, Parrott, & Eckhardt, 2016); Scott, DiLillo, Maldonado, & Watkins, 2015).

The Present Study

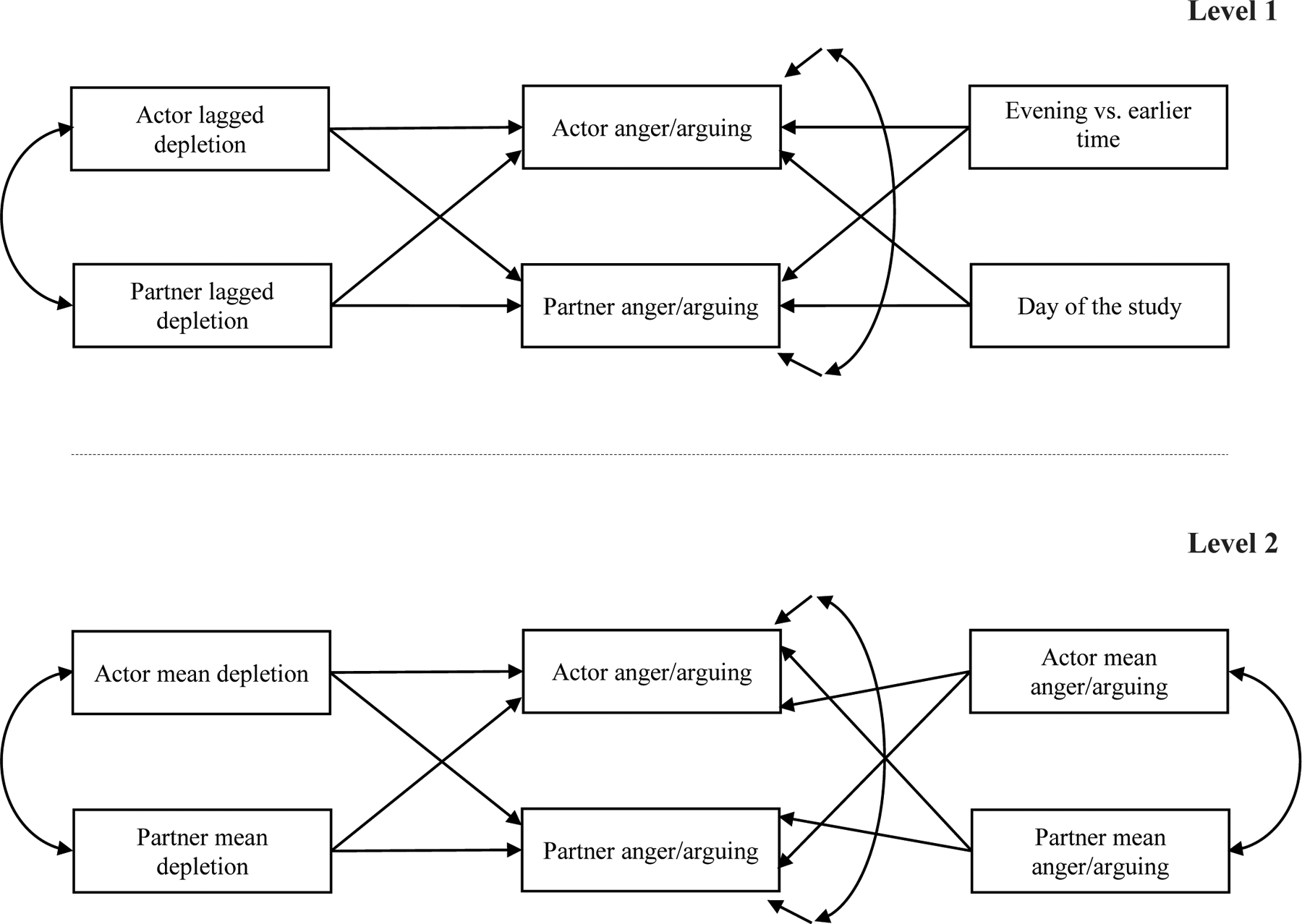

The present study was designed to examine the effects of state self-control on anger, arguing, and aggression directed toward one’s intimate partner, within a sample of young community couples at elevated risk of aggression. EMA methods were used to collect independent self-reports of the variables of interest, three times daily. We hypothesized that state self-control depletion will prospectively and positively predict self-reported anger toward and arguing with partner within the next few hours (reported at the next EMA). The availability of independent reports from each partner allowed us to consider not only Actor but also Partner depletion effects within the Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). As depicted in Figure 1, interacting with a partner whose self-control capacity is depleted may contribute to anger and arguing, independent of the actor’s own self-control strength.

Figure 1.

Level 1 and Level 2 predictors of Actor and Partner Anger and Arguing

We also considered whether state self-control contributes to the occurrence of partner aggression episodes. We expected that aggression episodes would be relatively rare, and would occur primarily during periods of elevated anger and arguing with partner. Consistent with the “Perfect Storm” perspective derived from the I3 Model (Finkel, 2014), we hypothesized that the relationship between anger/arguing (i.e., provocation) and aggression would be stronger when state self-control is depleted, since depletion weakens the ability to inhibit aggressive impulses. Similarly, we hypothesized that the relationship between provocation and aggression would be stronger for individuals high as opposed to low in trait negative urgency, since these individuals tend to act impulsively when experiencing negative emotion such as anger. In order to test hypotheses among couples at elevated risk of partner aggression (i.e., high impellance), we restricted the sample to couples with a history of partner aggression and heavy episodic drinking.

Method

Recruitment and Participants

Participants included 191 married or cohabiting heterosexual community couples from a medium-sized metropolitan area in the Northeast. Most couples were recruited through Facebook ads seeking couples, ages 21–35, who drink alcohol (160/191, 83.8%). Clicking the ad allowed respondents to complete a brief online screener (assessing age, relationship status, and alcohol use) and, if eligible and interested, to provide contact information. A small proportion were referred by previous participants (31/191, 16.2%). All couples were screened fully for eligibility by telephone. If the first partner met eligibility criteria, the second partner was also screened independently for eligibility and interest.

To be eligible, both partners had to be between 21 and 35 years old, married or cohabiting for at least 6 months, and currently living together. Both partners had to report perpetrating or receiving verbal aggression within the past year (e.g., yelled) or at least one partner had to report perpetrating or receiving physical aggression (pushed/shoved, threw something at partner, other physical aggression) in the past year. In addition, both partners were required to drink at least twice weekly, with at least two episodes of heavy episodic drinking (4+ drinks for women, 5+ for men) per month. These criteria were designed to yield a sample at higher than average risk of intimate partner aggression (Cafferky, Mendez, Anderson, & Stith, 2018), that is, high in impellance in the language of the I3 Model (Finkel, 2014). Because psychopathology or stimulant use may increase violence, couples were excluded if either reported psychiatric treatment or use of cocaine or stimulants. Pregnant women were excluded. For safety reasons, couples were excluded if either partner reported intimate partner aggression (IPA) that caused fear for one’s life or required medical care; they were provided referral information. Of 609 couples screened by telephone, 252 met eligibility criteria and 197 began the 30-day EMA study. Among couples who met initial online screener eligibility (age, relationship status, drinking) and were screened by telephone, the most common reason for ineligibility was absence of partner aggression. In order to analyze the data as distinguishable dyads (Kashy & Donnellan, 2012; Kenny et al., 2006), 6 same-sex couples were excluded from this analysis.

Most couples were cohabiting (61.5%) rather than married (38.5%), with average length of cohabitation (or marriage) of 3.88 years (range = 0.33 – 15.17, SD = 3.12). Men averaged 29.03 (SD = 3.56) and women 27.81 (SD = 3.39) years of age. Most participants self-identified as European-American (350/382, 91.6%), were employed full- or part-time (94.8% of men and 88.5% of women) and had a bachelor’s degree or higher (59.2% of men, 77.0% of women). Median personal income was $35,000 - $44,999 for both men and women.

Procedures

Eligible couples completed an in-person orientation. Partners were escorted to separate, private interview rooms for informed consent procedures and completion of baseline questionnaires. Couples were reunited for instruction on how to make independent, confidential reports on a secure web-based portal via smartphone. Each partner completed a practice report in the presence of the interviewer and had the opportunity to ask questions. Most (358/382, 93.7%) used their own phone, but participants could borrow a study-provided phone if necessary. Participants were instructed to respond to three random prompts each day for 30 consecutive days. Each report took about 5 minutes to complete and could be delayed by up to 60 minutes if necessary. Random prompts were typically sent between 10 AM – 2 PM, 2 PM – 6 PM, and 6 PM – 10 PM, with no less than 2 hours between them. In a small number of cases, times of the reports were adjusted to conform to work schedules (e.g., night shift). Participants were compensated $50 for completion of baseline questionnaires plus $1 for each random report completed and a bonus based on random report completion rate (e.g., 90% complete reports yielded $140 bonus). All procedures were approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board.

Baseline Measures

Impulsivity.

Participants completed the UPPS Impulsivity Scale (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Of relevance for this study was the Negative Urgency subscale, consisting of 12 items, measured on a 0 (disagree strongly) to 3 (agree strongly) scale. These included “I have trouble controlling my impulses” and “In the heat of an argument I will say things I later regret”. The subscale consisting of the mean of these items had good reliability (α = 0.89 for men and α = 0.88 for women).

Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA)

Three times daily, participants completed brief EMA reports which took an average of 3.13 minutes (SD = 3.83) to complete. Reports included state self-control depletion, positive and negative affect, and current couple functioning, described below. Items were measured on 0 (not at all) to 6 (very much) scales.

State self-control strength (depletion) was assessed using four items, adapted from Ciarocco, Twenge, Muraven, and Tice (2010), including “I’m having trouble concentrating right now”, “I’m having a hard time controlling my urges,” “If I were tempted by something right now it would be hard to resist”, and “If I were given a difficult task right now I would give up”. Higher scores indicate greater depletion. The four items, averaged, formed a reliable scale (α = 0.80).

Positive and negative affect.

Each EMA included 2 items assessing positive (happy, energetic; r = 0.46) and 3 items assessing negative affect (angry, sad, anxious; α = 0.75).

Couple functioning.

Four items assessed current relationship functioning: “How angry or irritated do you feel toward your partner right now?”, “Since your last report how much did you argue with your partner?”, “How close do you feel toward your partner right now?”, and “Since your last report, how well have you been getting along with your partner?” Items were assessed using 7-point scales ranging from not at all (0) to very much/very well (6). The anger and argue items (combined) constituted our primary outcome variable.

At each report, participants were asked “Since your last report, did you and your partner have a conflict, argument, or disagreement (either major or minor)?” If they responded affirmatively, they were asked what time the conflict occurred followed by a series of 10 yes/no questions, derived from the Conflict Tactics Scales (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996), assessing verbal and physical aggression perpetration and victimization (see Testa & Derrick, 2014). Items included yelled, made threats, insulted, pushed/grabbed/shoved, and threw/kicked/hit something. Each was asked in reference to perpetration (e.g., “I yelled at my partner”) and victimization (“My partner yelled at me”). A positive response to one or more items indicative of any type of aggression toward partner was classified as an episode of aggression perpetration. Similarly, a positive response to an item indicating receipt of aggression from partner was classified as an episode of victimization.

Analytic Strategy

Given the interdependent nature of partners’ reports within couples, we modeled equations for men and women simultaneously using multivariate multilevel modeling using Bayesian estimation within MPlus Version 8.2 (Gelman et al., 2014; Muthén & Muthén, 2017). The Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM, Kenny et al., 2006) permitted modeling of the effects of each person’s own depletion (Actor paths) and the effects of partner’s depletion (Partner paths) on each person’s report of anger and arguing with partner.

To test the primary hypothesis, at Level 1 (the event level), we included the lagged depletion variable from the prior EMA report, person mean centered, for self (Actor) and Partner. Hence, elevations in depletion represent deviations from one’s own mean. We also included time of report (uncentered, 1 = 5 PM-midnight; 0 = all other hours) to account for potential diurnal effects (e.g., partner conflicts are more likely to occur in the evening, Testa et al., 2018). Day of the study (1 – 30, grand mean centered) was entered at Level 1 to control for potential change in outcomes over time. At Level 2 (the couple level), we controlled for each partner’s mean anger/arguing (or total aggression events in the aggression analyses) and mean depletion over the study days, allowing us to account for between-person effects and to distinguish within-person effects of depletion from between-person effects. All Level-2 variables were grand mean centered (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). Level 1 and Level 2 effects for the primary hypothesis are depicted in Figure 1.

To test hypotheses with aggression as the outcome, we used a similar method. At Level 1, we included each partner’s anger/arguing from the same report and depletion from the prior report. In the first of these analyses, we also included a Level 1 interaction term to test whether depletion X anger/argue increased the likelihood of aggression. Alternatively, we included a cross-level interaction to consider whether negative urgency interacted with anger/argue to increase the likelihood of aggression.

Results

Descriptive Data

Compliance with EMA was excellent; 31,279 EMA reports (91.0%) were completed out of a possible total 34,380 reports (382 individuals × 30 days × 3 random reports per day). Men completed 81.69/90 reports (90.8%) and women completed 83.64/90 (92.9%). On average, reports were completed at 11.36 (SD = 1.51), 15.59 (SD = 1.50) and 19.66 (SD = 1.57) hours, or roughly 11:30 AM, 3:30 PM and 7:40 PM. Completion rates were virtually identical for morning, afternoon, and evening reports. Within each report, depletion, positive affect, negative affect, arguments, and anger were correlated in expected ways and within-couple measures were modestly positively correlated (see Table 1). Arguments with partner and anger toward partner (r = 0.61) were combined for use in analyses, although the pattern of results was the same when examined separately.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations among Primary Variables

| Variable | Descriptive Statistics | Correlations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Depletion | Positive affect | Negative affect | Argue with partner | Anger with partner | Negative urgency | |

| M | 1.20 | 3.65 | 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 1.16 | ||

| SD | 1.28 | 1.40 | 1.08 | 1.18 | 1.16 | 0.58 | ||

| Depletion | 1.32 | 1.34 | 0.14** | −0.35** | 0.55** | 0.26** | 0.32** | 0.33** |

| Positive affect | 3.48 | 1.37 | −0.31** | 0.23** | −0.39** | −0.20** | −0.25** | −0.22** |

| Negative affect | 0.90 | 1.16 | 0.47** | −0.44** | 0.14** | 0.39** | 0.46** | 0.31** |

| Argue with partner | 0.51 | 1.19 | 0.17** | −0.18** | 0.32** | 0.32** | 0.61** | 0.16** |

| Anger with partner | 0.56 | 1.25 | 0.22** | −0.26** | 0.43** | 0.61** | 0.23** | 0.18** |

| Negative urgency | 1.36 | 0.57 | 0.23** | −0.16** | 0.19** | 0.10** | 0.12** | 0.14** |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Note: Correlations among male-reported variables are above the diagonal, and the correlations among female-reported variables are below the diagonal. Values on the diagonal are the correlations between the partners in the couple. Descriptive statistics at the top are for males and at the side for females.

Does Self-Control Depletion Predict Subsequent Partner-Specific Anger and Arguing?

The study was designed to test the hypothesis that Actor and Partner depletion increase levels of anger and arguing with partner reported at the next assessment, that is, prospectively. As shown in Table 2, Model 1, there were significant positive lagged effects of Actor and Partner depletion on anger/arguing for both men and women. The A x P interaction term was not significant and did not alter any effects depicted, hence it is not displayed. The analysis accounted for the mean levels of Actor and Partner depletion across the 30 days and for mean levels of anger/arguing at Level 2. Consistent with prior studies, at Level 1 we found higher levels of anger and arguing after 5 PM and lower levels on later days of the study (Testa et al., 2018). We also conducted analyses using reports of depletion and anger/arguing made at the same time (not shown) and found significant positive Actor and Partner depletion effects, replicating the cross-sectional findings of Crane et al. (2014).

Table 2.

Anger and Arguing as a Function of Actor and Partner Depletion at the Previous Report

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Male-reported anger/arguing | Female-reported anger/arguing | Male-reported anger/arguing | Female-reported anger/arguing | ||||

| Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 0.541 (0.010)*** | [0.523, 0.559] | 0.515 (0.011)*** | [0.497, 0.536] | 0.535 (0.008)*** | [0.523, 0.555] | 0.512 (0.010)*** | [0.490, 0.528] |

| Level 1 | ||||||||

| Actor depletion | 0.068 (0.009)*** | [0.050, 0.086] | 0.054 (0.010)*** | [0.035, 0.072] | 0.034 (0.009)*** | [0.017, 0.051] | 0.018 (0.009)* | [0.000, 0.037] |

| Partner depletion | 0.023 (0.009)** | [0.006, 0.041] | 0.037 (0.010)*** | [0.017, 0.056] | 0.005 (0.009) | [−0.011, 0.022] | 0.011 (0.009) | [−0.007, 0.030] |

| Evening vs. earlier time1 | 0.031 (0.014)* | [0.003, 0.059] | 0.058 (0.016)*** | [0.026, 0.088] | 0.043 (0.014)** | [0.015, 0.068] | 0.071 (0.015)*** | [0.042, 0.103] |

| Day of the study2 | −0.006 (0.001)*** | [−0.008, −0.005] | −0.005 (0.001)*** | [−0.007, −0.004] | −0.005 (0.001)*** | [−0.007, −0.003] | −0.004 (0.001)*** | [−0.006, −0.002] |

| Actor prior block anger/arguing3 | 0.178 (0.009)*** | [0.159, 0.196] | 0.215 (0.009)*** | [0.198, 0.233] | ||||

| Partner prior block anger/arguing | 0.086 (0.008)*** | [0.070, 0.103] | 0.083 (0.010)*** | [0.063, 0.102] | ||||

| Level 2 | ||||||||

| Actor mean of depletion over 30 days | 0.002 (0.010) | [−0.013, 0.023] | 0.005 (0.009) | [−0.013, 0.019] | 0.004 (0.009) | [−0.014, 0.020] | 0.000 (0.008) | [−0.014, 0.018] |

| Partner mean of depletion over 30 days | 0.004 (0.007) | [−0.014, 0.015] | 0.008 (0.010) | [−0.011, 0.028] | 0.000 (0.008) | [−0.016, 0.014] | 0.010 (0.011) | [−0.010, 0.031] |

| Actor mean of anger/arguing over 30 days | 0.988 (0.017)*** | [0.954, 1.015] | 0.984 (0.017)*** | [0.952, 1.024] | 0.985 (0.018)*** | [0.948, 1.019] | 0.990 (0.016)*** | [0.958, 1.018] |

| Partner mean of anger/arguing over 30 days | −0.005 (0.015) | [−0.032, 0.029] | −0.016 (0.017) | [−0.045, 0.018] | 0.000 (0.014) | [−0.027, 0.029] | −0.009 (0.018) | [−0.046, 0.025] |

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

Time (0 = 1 AM to 4 PM; 1 = 5 PM to 12 AM)

Day of the study (1–30)

The lagged dependent variable

To make the analysis more conservative, in addition to controlling for mean levels of anger/arguing at Level 2, we controlled for anger/arguing with partner reported at the previous report. We reasoned that a given level of relationship discord may persist over several hours and potentially may contribute to later depletion (Baumeister et al., 2019). As shown in Table 2, Model 2, lagged Actor and Partner anger/arguing had robust positive effects on later anger/arguing. Inclusion of these terms reduced the lagged effects of depletion on later anger/arguing. The Actor lagged depletion effect remained significant for both male and female reports but the Partner depletion effect was reduced to non-significance for males and females.

The weakened effect of depletion on later anger/arguing after accounting for the robust effect of earlier anger/arguing suggests that arguing may lead to depletion, which in turn predicts later arguing. To explore this possibility, we regressed depletion on anger/arguing. As shown in Table 3, there were robust positive effects of Actor anger and arguing on depletion for both males and females. That is, depletion was higher when the participant reported higher levels of anger and arguing with partner in the period preceding the report. The effect remained when we controlled for prior level of depletion.

Table 3.

Depletion as a Function of Actor and Partner Anger and Arguing at the Previous Report

| Variable | Male-reported depletion | Female-reported depletion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 1.149 (0.009)*** | [1.133, 1.167] | 1.295 (0.008)*** | [1.278, 1.308] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Actor anger/arguing | 0.075 (0.009)*** | [0.057, 0.093] | 0.065 (0.009)*** | [0.048, 0.082] |

| Partner anger/arguing | −0.012 (0.008) | [−0.029, 0.004] | 0.001 (0.010) | [−0.018, 0.020] |

| Evening vs. earlier time1 | 0.128 (0.014)*** | [0.100, 0.156] | 0.096 (0.014)*** | [0.069, 0.123] |

| Day of the study2 | −0.003 (0.001)*** | [−0.005, −0.001] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.002] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Actor mean of anger/arguing over 30 days | 0.005 (0.017) | [−0.035, 0.037] | −0.004 (0.016) | [−0.038, 0.023] |

| Partner mean of anger/arguing over 30 days | −0.004 (0.019) | [−0.051, 0.030] | 0.009 (0.017) | [−0.024, 0.047] |

| Actor mean of depletion over 30 days | 0.995 (0.010)*** | [0.973, 1.013] | 0.996 (0.009)*** | [0.981, 1.015] |

| Partner mean of depletion over 30 days | −0.001 (0.008) | [−0.016, 0.015] | −0.004 (0.009) | [−0.021, 0.015] |

p < .001

p < .01,

p < .05

Time (0 = 1 AM to 4 PM; 1 = 5 PM to 12 AM)

Day of the study (1–30)

Does Depletion Contribute to Partner Aggression?

We next considered whether depletion contributes to partner aggression episodes. Of 31,279 EMA reports, 2,463 conflict events were reported, 1,426 by women and 1,037 by men. Of these, 949 conflicts included aggression perpetration. Most aggressive events included verbal aggression only (881/949, 92.8%); the rest included verbal and physical (60) or physical only (8). Although just 3.0% of reports included an episode of aggression, most participants (268/382, 70.2%) reported at least one aggressive episode over the course of the study. As expected, reports that included aggression perpetration included much higher self-reported anger and arguing (M = 3.03, SD = 1.68) compared with reports that did not include aggression (M = 0.46, SD = 0.95), t(31,146) = 79.442, p < .001) and significantly higher depletion (M = 1.79, SD = 1.52) compared with reports without aggression (M = 1.24, SD = 1.30), t(31,147) =12.675, p < .001).

Anger and arguing with partner represent instigation or provocation, which is a key precursor to aggression within the I3 Model. We hypothesized that the relationship between instigation and aggression would be stronger at times when inhibition is weak, that is, when self-control is depleted. Table 4, Model 1 depicts the results of this analysis. As expected, there was a robust positive effect of anger/arguing on aggression. However, the main effect of prior report state depletion on aggression was not significant nor was the hypothesized interaction between depletion and anger/arguing.

Table 4.

Aggression Perpetration as a Function of Actor and Partner Depletion at the Previous Report

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Male-reported perpetration | Female-reported perpetration | Male-reported perpetration | Female-reported perpetration | ||||

| Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 2.784 (0.084)*** | [2.629, 2.946] | 2.421 (0.049)*** | [2.336, 2.518] | 2.656 (0.061)*** | [2.536, 2.773] | 2.323 (0.045)*** | 2.258, 2.443] |

| Level 1 | ||||||||

| Actor depletion | −0.111 (0.058) | [−0.224, 0.009] | −0.024 (0.037) | [−0.098, 0.047] | ||||

| Partner depletion | −0.031 (0.050) | [−0.128, 0.070] | 0.023 (0.038) | [−0.052, 0.097] | ||||

| Evening vs. earlier time1 | −0.068 (0.076) | [−0.215, 0.084] | −0.047 (0.059) | [−0.161, 0.072] | −0.118 (0.066) | [−0.251, 0.014] | −0.087 (0.054) | [−0.194, 0.026] |

| Day of the study2 | −0.001 (0.004) | [−0.010, 0.007] | −0.009 (0.003)** | [−0.015, −0.002] | −0.003 (0.004) | [−0.011, 0.005] | −0.009 (0.003)** | [−0.015, −0.003] |

| Actor anger/arguing | 0.507 (0.036)*** | [0.436, 0.579] | 0.592 (0.027)*** | [0.538, 0.645] | 0.542 (0.046)*** | [0.453, 0.635] | 0.491 (0.043)*** | [0.410, 0.580] |

| Partner anger/arguing | 0.193 (0.033)*** | [0.127, 0.259] | 0.242 (0.031)*** | [0.181, 0.301] | 0.165 (0.053)** | [0.064, 0.272] | 0.271 (0.040)*** | [0.192, 0.347] |

| Actor depletion X Actor anger/arguing | 0.017 (0.017) | [−0.017, 0.051] | −0.009 (0.012) | [−0.032, 0.014] | ||||

| Partner depletion X Partner anger/arguing | −0.005 (0.016) | [−0.036, 0.025] | −0.012 (0.014) | [−0.040, 0.017] | ||||

| Actor urgency X Actor anger/arguing | −0.007 (0.033) | [−0.071, 0.058] | 0.041 (0.026) | [−0.011, 0.092] | ||||

| Partner urgency X Partner anger/arguing | −0.001 (0.031) | [−0.067, 0.057] | −0.045 (0.026) | [−0.093, 0.008] | ||||

| Level 2 | ||||||||

| Actor mean of depletion over 30 days | −0.012 (0.081) | [−0.154, 0.153] | 0.051 (0.039) | [−0.025, 0.126] | ||||

| Partner mean of depletion over 30 days | 0.040 (0.050) | [−0.065, 0.136] | 0.101 (0.051) | [0.000, 0.206] | ||||

| Actor total perpetration episodes over 30 days | 0.189 (0.020)*** | [0.150, 0.231] | 0.172 (0.011)*** | [0.150, 0.192] | 0.187 (0.017)*** | [0.159, 0.225] | 0.154 (0.010)*** | [0.133, 0.172] |

| Partner total perpetration episodes over 30 days | 0.009 (0.016) | [−0.020, 0.042] | −0.029 (0.017) | [−0.066, 0.003] | −0.001 (0.013) | [−0.027, 0.025] | −0.022 (0.016) | [−0.052, 0.009] |

| Actor mean of anger/arguing over 30 days | −0.184 (0.114) | [−0.448, 0.027] | −0.199 (0.079)** | [−0.354, −0.051] | 0.034 (0.077) | [−0.111, 0.187] | −0.250 (0.073)*** | [−0.368, −0.079] |

| Partner mean of anger/arguing over 30 days | 0.047 (0.092) | [−0.137, 0.225] | −0.063 (0.087) | [−0.241, 0.109] | −0.016 (0.086) | [−0.185, 0.156] | 0.065 (0.057) | [−0.078, 0.154] |

| Actor urgency | −0.068 (0.094) | [−0.239, 0.138] | −0.030 (0.055) | [−0.134, 0.084] | ||||

| Partner urgency | −0.027 (0.078) | [−0.159, 0.152] | 0.015 (0.069) | [−0.118, 0.155] | ||||

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

Time (0 = 1 AM to 4 PM; 1 = 5 PM to 12 AM)

Day of the study (1–30)

We then considered whether negative urgency at Level 2 moderates the effect of anger/arguing at Level 1 (i.e., provocation) on aggression, testing the hypotheses that individuals high as opposed to low in this trait are more likely to aggress when experiencing negative emotions. As shown in Table 4, Model 2, the cross-level negative urgency X anger/arguing interaction terms did not contribute to prediction of aggression; provocation was no more likely to result in aggression for individuals high in negative urgency. To ensure that results were robust, we repeated all Table 4 analyses substituting victimization for perpetration; the pattern of results was unchanged1.

Discussion

This EMA study is among the first to consider the impact of fluctuating levels of state self-control depletion on couple functioning throughout the day. Findings replicated earlier studies that have shown positive associations between depletion and poorer couple outcomes at the daily (i.e., cross-sectional) level (Buck & Neff, 2012; Crane et al., 2014). Using thrice-daily random reports, we also demonstrated positive prospective Actor and Partner depletion effects. Elevated depletion (relative to one’s own mean) at one assessment positively predicted anger and arguing with partner at the next assessment. Findings supported the hypothesis, derived from the self-control strength model, that when self-regulatory resources are taxed in the course of daily life, couple functioning suffers in the short term. Depleted self-control, presumably by impairing the ability to inhibit urges (Hofmann, Vohs, & Baumeister, 2012) and by intensifying subsequent emotions and impulses (Wagner & Heatherton, 2014), resulted in heightened anger and arguing with partner over the next few hours.

These findings are not the end of the story, however. When we controlled for levels of anger and arguing reported at the previous assessment, the independent effects of depletion on later anger and arguing were diminished. Actor depletion effect remained significant but Partner effects disappeared. The robust relationship between prior anger/arguing and later anger/arguing shows that couple functioning does not “reset” quickly, but rather lingers over several hours. Further, in exploring this finding we found, consistent with Baumeister et al. (2019), that anger and arguing positively predicted later depletion. Arguing with one’s partner is likely to involve regulation of emotion and inhibition of angry and aggressive responses, contributing to subsequent depletion (Wagner & Heatherton, 2014). Consequently, when depleted, it is more difficult to avoid arguments later in the day, suggesting a positive feedback loop with respect to arguing and depletion.

As expected, anger and arguing were robustly and positively associated with the occurrence of aggression. Within the I3 Model, anger and arguing may be viewed as representing provocation, a key condition for aggression. Among this sample of heavy drinking couples with a history of recent partner aggression (i.e., high impellance), we found no evidence that state self-control depletion interacted with provocation to predict aggression. We also failed to find evidence that the provocation – aggression relationship was stronger for impulsive people, that is, those high in negative urgency. Support for these predictions derived from the I3 Model has come largely from controlled experimental studies in which behavioral aggression options were limited (e.g., to choosing a level of white noise to administer to partner; Watkins, DiLillo, Hoffman, & Templin, 2015). In daily life partners have more behavioral options; for example, they may opt to remove themselves from a conflictual situation by leaving the house. It is also possible that the strong effects of anger and arguing on aggression made it difficult to detect small moderation effects which were hypothesized to involve changing the strength of the relationship rather than the direction.

Limitations

The availability of up to 90 independent random reports obtained over 30 days from a large sample of community couples is a unique strength of the study, allowing us to examine whether findings obtained primarily through controlled, experimental studies are observable in daily life. However, to make this in vivo data collection feasible, we had to make several difficult methodological decisions which may have impacted findings. First, the study depended upon self-reports of fleeting states such as feelings of depletion. Although we chose items from prior measures, in consultation with experts, there is some question about the ability of individuals to recognize and self-report their experiences of self-control depletion (e.g., Baumeister & Vohs, 2016; Muraven & Slessareva, 2003). It is encouraging that findings replicated earlier daily report studies that used different depletion items (Buck & Neff, 2012; Crane et al., 2014). To reduce participant burden, we obtained reports three times daily, with several hours in between assessments. However, if depletion effects are relatively short-lived, we may have had too few measurements to detect the hypothesized effects. Also, depletion measures were person-mean centered, meaning that we conceptualized high depletion as relative to the mean level for that person. It is possible that depletion does not have the expected effects until a certain (unknown) objective threshold is reached. We note that although self-control is thought to be replenished by sleep (Baumeister et al., 2019), we found the same pattern of results when data were analyzed separately for morning, afternoon, and evening reports. It was somewhat surprising that evening depletion predicted morning reports of arguing, although it is plausible that the arguing occurred the evening before, after the final report of the day.

Our method of assessing aggression required that participants indicate that they had experienced an episode of partner conflict; consistent with prior studies (e.g., Testa & Derrick, 2014; Testa et al., 2018). That is, aggression items were asked only if a conflict was reported. This method may have underestimated the occurrence of partner aggression, thereby limiting our ability to detect hypothesized depletion, negative urgency, and moderation effects. A more sensitive measure of aggression, for example using a series of behaviorally specific items at each assessment, would be advisable for future research. Finally, results were based on a sample of young, primarily European-American, heavy drinking couples in a single metropolitan area and may not generalize.

Conclusions

Using self-report EMA data to test real-world dyadic processes is complicated by the lack of control possible in experimental research and limitations of self-report measures. It will be important for future research to consider these methodological and measurement issues in designing the most sensitive tests of real-world depletion effects on relationship functioning. Naturalistic research on depletion and relationship functioning is in its infancy, making clinical implications tentative. Nonetheless, findings support a role for self-control depletion in understanding daily relationship functioning. Depleted self-control contributes to anger and arguing with partner in the short-term. Although depletion did not increase the likelihood that anger and arguing would result in aggression, depletion may be said to have an indirect effect on aggression, in that anger and arguing was a strong precursor of aggressive episodes. Moreover, anger and arguing with one’s partner contributes to depletion, which may contribute to deteriorating relationship quality over time (via subsequent anger and arguing), as well as to negative effects on other domains.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grant R01AA022946 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

At each EMA, participants reported whether they had consumed alcohol since the last report. To ensure that the occurrence of a drinking episode does not confound the depletion effects examined here, we re-ran all analyses (Tables 2 – 4) including self-reported drinking as a Level 1 covariate. Results were unchanged, thus, drinking episodes do not account for the effects.

Contributor Information

Maria Testa, Department of Psychology, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, U.S.A.

Weijun Wang, Department of Psychology, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, U.S.A.

Jaye L. Derrick, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Texas, U.S.A.

Cory Crane, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY, U.S.A.

Kenneth E. Leonard, Clinical and Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, U.S.A.

R. Lorraine Collins, Department of Community Health and Health Behavior, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, U.S.A.

Courtney Hanny, Department of Psychology, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, U.S.A.

Mark Muraven, Department of Psychology, University at Albany, State University of New York, U.S.A.

References

- Baker EA, Klipfel KM, & van Dulmen MHM (2018). Self-control and emotional and verbal aggression in dating relationships: A dyadic understanding. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33, 3551–3571. 10.1177/0886260516636067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlett C, Oliphant H, Gregory W, & Jones D (2016). Ego-depletion and aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 42(6), 533–541. doi: 10.1002/ab.21648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, & Vohs KD (2016). Misguided effort with elusive implications. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 574–575. doi: 10.1177/1745691616652878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, & Tice DM (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 351–355. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Wright BRE, & Carreon D (2019). Self-control ‘in the wild’: Experience sampling study of trait and state self-regulation. Self and Identity, 18, 494–528. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2018.1478324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake KR, Hopkins RE, Sprunger JG, Eckhardt CI, & Denson TF (2018). Relationship quality and cognitive reappraisal moderate the effects of negative urgency on behavioral inclinations toward aggression and intimate partner violence. Psychology of Violence, 8, 218–228. doi: 10.1037/vio0000121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buck AA, & Neff LA (2012). Stress spillover in early marriage: The role of self-regulatory depletion. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 698–708. 10.1037/a0029260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferky BM, Mendez M, Anderson JR, & Stith SM (2018). Substance use and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Violence, 8(1), 110–131. doi: 10.1037/vio0000074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EC, Kofler LM, Forster DE, & McCullough ME (2015). A series of meta-analytic tests of the depletion effect: Self-control does not seem to rely on a limited resource. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144, 796–815. doi: 10.1037/xge0000083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen P, Cole JC, & Field M (2012). Ego depletion increases ad-lib alcohol consumption: Investigating cognitive mediators and moderators. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20, 118–128. 10.1037/a0026623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarocco NJ, Twenge J, Muraven M, & Tice D (2010). The state self-control capacity scale: Reliability, validity, and correlations with physical and psychological stress. San Diego State University; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Testa M, Derrick JL, & Leonard KE (2014). Daily associations among self-control, heavy episodic drinking, and relationship functioning: An examination of actor and partner effects. Aggressive Behavior, 40, 440–450. doi: 10.1002/ab.21533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, & Smith GT (2008). Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin, 134(6), 807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derefinko K, DeWall CN, Metze AV, Walsh EC, & Lynam DR (2011). Do different facets of impulsivity predict different types of aggression? Aggressive Behavior, 37, 223–233. 10.1002/ab.20387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall CN, Baumeister RF, Stillman TF, & Gailliot M (2007). Violence restrained: Effects of self-regulation and its depletion on aggression. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 62–76. 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall CN, Finkel EJ, & Denson TF (2011). Self-control inhibits agression. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5, 458–472. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00363.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Tofighi D (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ (2014). The I3 Model: Metatheory, theory, and evidence. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 1–104. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800052-6.00001-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, & Campbell KW (2001). Self-control and accommodation in close relationships: An interdependence analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 263–277. 10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, DeWall CN, Slotter EB, McNulty JK, Pond RS, & Atkins DC (2012). Using I3 theory to clarify when dispositional aggressiveness predicts intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 533–549. 10.1037/a0025651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, DeWall CN, Slotter EB, Oaten M, & Foshee VA (2009). Self-regulatory failure and intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 483–499. 10.1037/a0015433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese M, & Hofmann W (2009). Control me or I will control you: Impulses, trait self-control, and the guidance of behavior. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 795–805. 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friese M, Loschelder DD, Gieseler K, Frankenbach J, & Inzlicht M (2019). Is ego depletion real? An analysis of arguments. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(2), 107–131. doi: 10.1177/1088868318762183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon J, & Rochat L (2017). Relationships between hostile attribution bias, negative urgency, and reactive aggression. Journal of Individual Differences, 38(4), 211–219. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001/a000238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, & Rubin DB (2014). Bayesian data analysis (Vol. 2). Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Gomillion S, Lamarche VM, Murray SL, & Harris B (2014). Protected by your self-control: The influence of partners’ self-control on actors’ responses to interpersonal risk. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(8), 873–882. doi: 10.1177/1948550614538462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagger MS, & Chatzisarantis NLD (2016). A multilab preregistered replication of the ego-depletion effect. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 546–573. doi: 10.1177/1745691616652873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagger MS, Wood C, Stiff C, & Chatzisarantis NLD (2010). Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 495–525. doi: 10.1037/a0019486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht LK, & Latzman RD (2015). Revealing the nuanced associations between facets of trait impulsivity and reactive and proactive aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Baumeister RF, Forster G, & Vohs KD (2012). Everyday temptations: An experience sampling study of desire, conflict, and self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 1318–1335. 10.1037/a0026545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Vohs KD, & Baumeister RF (2012). What people desire, feel conflicted about, and try to resist in everyday life. Psychological Science, 23, 582– 588. 10.1177/0956797612437426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, & Donnellan MB (2012). Conceptual and methodological issues in the analysis of data from dyads and groups In Deaux K & Snyder M (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook Of Personality and Social Psychology (pp. 209–238): Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2006). Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leone RM, Crane CA, Parrott DJ, & Eckhardt CI (2016). Problematic drinking, impulsivity, and physical IPV perpetration: A dyadic analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(3), 356–366. doi: 10.1037/adb0000159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, & Baumeister RF (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126, 247–259. 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, & Slessareva E (2003). Mechanism of self-control failure: Motivation and limited resources. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 894–906. 10.1177/0146167203029007008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus Users’ Guide: Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT (2017). On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(4), 361–383. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood JM, & Muraven M (2016). Does counting to ten increase or decrease aggression? The role of state self-control (ego-depletion) and consequences. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 46, 105–113. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owens MM, Amlung MT, Stojek M, & MacKillop J (2018). Negative urgency moderates reactivity to laboratory stress inductions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(4), 385–393. doi: 10.1037/abn0000350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley BM, Levitt A, Derrick JL, Testa M, Houston RJ, & Leonard KE (2018). Alcohol, self-regulation and partner physical aggression: Actor-partner effects over a three-year time frame. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12 (article ID 30). doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JP, DiLillo D, Maldonado RC, & Watkins LE (2015). Negative urgency and emotion regulation strategy use: Associations with displaced aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 41, 502–512. 10.1002/ab.21588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellahewa DA, & Mullan B (2015). Health behaviours and their facilitation under depletion conditions: The case of snacking. Appetite, 90, 194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck CA, Gulati NK, & Fromme K (2016). Daily associations between alcohol consumption and dating violence perpetration among men and women: Effects of self-regulation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77, 150–159. 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, & Sugarman DB (1996). The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17, 283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stucke TS, & Baumeister RF (2006). Ego depletion and aggressive behavior: Is the inhibition of aggression a limited resource? European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 1–13. 10.1002/ejsp.285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subramani OS, Parrott DJ, Latzman RD, & Washburn DA (2018). Breaking the link: Distraction from emotional cues reduces the association between trait disinhibition and reactive physical aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 45(2), 151–160. doi: 10.1002/ab.21804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, & Derrick JL (2014). A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol use and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28, 127–138. Doi: 10.1037/a0032988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Derrick JL, Wang W, Leonard KE, Kubiak A, Brown WC, & Collins RL (2018). Does marijuana contribute to intimate partner aggression? Temporal effects in a community sample of marijuana-using couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79, 432–440. 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, & Ciarocco NJ (2005). Self-regulation and self-presentation: Regulatory resource depletion impairs impression management and effortful self-presentation depletes regulatory resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 632–657. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DD, & Heatherton TF (2014). Emotion and self-regulation failure In Gross JJ (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation, 2nd ed. (pp. 613–628). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LE, DiLillo D, Hoffman L, & Templin J (2015). Do self-control depletion and negative emotion contribute to intimate partner aggression? A lab-based study. Psychology of Violence, 5, 35–45. doi: 10.1037/a0033955 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, & Lynam DR (2001). The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 669–689. 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]