Abstract

Neurodegeneration of the locus coeruleus (LC) in age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is well-documented. However, detailed studies of LC neurodegeneration in the full spectrum of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) proteinopathies comparing tauopathies (FTLD-tau) to TDP-43 proteinopathies (FTLD-TDP) are lacking. Here, we tested the hypothesis that there is greater LC neuropathology and neurodegeneration in FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP. We examined 280 patients including FTLD-tau (n=94), FTLD-TDP (n=135), and two reference groups: clinical/pathological AD (n=32) and healthy controls (HC,n=19). Adjacent sections of pons tissue containing the LC were immunostained for phosphorylated TDP-43 (ID3-p409/410), hyperphosphorylated tau (PHF-1), and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) to examine neuromelanin-containing noradrenergic neurons. Blinded to clinical and pathologic diagnoses, we semi-quantitatively scored inclusions of tau and TDP-43 both inside LC neuronal somas and in surrounding neuropil. We also digitally measured the percent area occupied of neuromelanin inside of TH-positive LC neurons and in surrounding neuropil to calculate a ratio of extracellular-to-intracellular neuromelanin as an objective composite measure of neurodegeneration. We found that LC tau burden in FTLD-tau was greater than LC TDP-43 burden in FTLD-TDP (z=−11.38,p<0.0001). Digital measures of LC neurodegeneration in FTLD-tau was comparable to AD (z=−1.84,p>0.05) but greater than FTLD-TDP (z=−3.85,p<0.0001) and HC (z=−4.12,p<0.0001). Both tau burden and neurodegeneration were consistently elevated in the LC across pathologic and clinical subgroups of FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP subgroups. Moreover, LC tau burden positively correlated with neurodegeneration in the total FTLD group (rho=0.24,p=0.001), while TDP-43 burden did not correlate with LC neurodegeneration in FTLD-TDP (rho=−0.01,p=0.90). These findings suggest that patterns of disease propagation across all tauopathies include prominent LC tau and neurodegeneration that are relatively distinct from the minimal degenerative changes to the LC in FTLD-TDP and HC. Antemortem detection of LC neurodegeneration and/or function could potentially improve antemortem differentiation of underlying FTLD-tauopathies from clinically similar FTLD-TDP proteinopathies.

Keywords: locus coeruleus, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, tauopathy, TDP-43

INTRODUCTION

The locus coeruleus (LC) is a bilateral pontine nucleus of catecholaminergic neurons that produces the primary source of norepinephrine for the central nervous system. Anatomical tracing studies indicate that LC afferents may be relatively few compared to the many LC efferents [3, 21]. More caudal noradrenergic neurons of the LC have efferents that descend into the spinal cord, while more rostral noradrenergic neurons innervate the brainstem, thalamus, cerebellum, and much of the cortex [3, 5, 21]. Due to its extensive interconnected network, alterations to the LC and its broad projections may disrupt numerous cognitive functions including arousal, attention, learning, and memory [6].

Postmortem examinations of the LC suggest that it is one of the first brain structures to accumulate hyperphosphorylated tau inclusions in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [13, 19, 70]. In addition to AD, the LC is also susceptible to the formation of tau neuropathology in select sporadic tauopathies and even normal aging, the accumulation of which may lead to cognitive or motor impairments [12, 20, 22, 27, 31, 43]. The LC may be an important site of tau spread given recent evidence from a mouse model inoculated with tau pathology in the LC that demonstrated the LC can seed tau formation and its transneuronal propagation to much of the greater cortex via major afferents and efferents of the LC [38]. LC neuropathology is often accompanied by neurodegeneration in AD as evidenced by neuronal loss [10, 23, 51, 71] and depigmentation of neuromelanin [33] in analyses of neuromelanin-containing neurons characteristic of the LC.

Despite well-documented tau pathology in the LC of some tauopathies including AD, the extent to which neuropathologic changes occur in the LC of patients neuropathologically diagnosed with frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) is far less understood. Specifically, there is a lack of comparative studies of the LC from patients with primary tauopathies (FTLD-tau) relative to FTLD patients with inclusions positive for transactive response DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43). The majority of prior studies on the LC were performed on small patient populations prior to modern nomenclature and nosology of FTLD neuropathology [16] and the discovery of TDP-43 as the main constituent of protein inclusions in the majority of tau-negative FTLD cases [57]. Furthermore, investigations of the LC in the FTLD spectrum have not yet used digital image analyses to detect and objectively quantify subtle neurodegenerative processes such as alterations to neuromelanin content in the human LC.

The differential involvement of the LC in FLTD has important implications for biomarker development, especially in the frontotemporal dementia (FTD) clinical spectrum where biomarkers are limited and FTD clinical syndromes poorly predict underlying pathology on an individual patient level [41]. Select studies of autopsy-confirmed tauopathies suggests that tau pathology and neurodegeneration are prominent in the LC [1, 20, 22, 27, 39, 43]. In contrast, relative sparing of the LC has been described in recent histopathological staging studies of FTLD patients with TDP-43 neuropathology (FTLD-TDP) that included advanced disease stages of dementia [14] or motor syndromes [11, 15], but a detailed study of the LC in FTLD-TDP is lacking. Therefore, we hypothesized that the LC would display greater neuropathologic change and neurodegeneration in all subgroups of FTLD-tau compared to all subgroups of FTLD-TDP. We tested this by performing a novel, large-scale comparative study evaluating the severity of neuropathology and neurodegeneration based on changes to neuromelanin content in the LC of the FTLD spectrum in comparison to reference groups of healthy aged controls and AD. We find that LC neurodegeneration is a prominent, unifying feature of tauopathies that is similar to AD but distinct from the minimal changes observed in the LC of FTLD-TDP and healthy controls. Our postmortem evidence of greater neurodegeneration of the LC in FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP suggests that antemortem detection of LC integrity by non-invasive neuroimaging of neuromelanin content, for example, could serve as a sensitive biomarker used to help differentiate these FTLD proteinopathies.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Patients

Patients were followed clinically at the clinical research cores at the Frontotemporal Degeneration Center, Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Comprehensive ALS Center, or Movement Disorder Center at Penn. Clinical diagnoses were designated prospectively based on published consensus guidelines [2, 30, 35, 53, 60]. For patients evaluated prior to modern clinical criteria, clinical phenotypes were assigned based on retrospective chart review. Autopsies were performed at University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research (CNDR) and the Hospital of University of Pennsylvania.

Brain tissue was processed as described previously [64]. In brief, fresh tissue was sampled at autopsy for neuropathological diagnosis in standardized regions, including transverse sections of the rostral pons containing the LC. Tissue was fixed overnight in 10% neutral buffered formalin or 70% ethanol with 150mmol NaCl, and paraffin-embedded blocks were cut into 6μm-thick sections. Neuropathologic diagnoses were made by neuropathologists (E.B.L. and J.Q.T.) using established criteria [16, 48, 52, 54] based on paraffin-embedded tissue sections stained with well-characterized antibodies to tau, amyloid-β, α-synuclein, and TDP-43 as described previously. Clinical and pathological data from autopsied cases meeting criteria for this investigation were obtained from the Penn Integrated Neurodegenerative Disease Database (INDD) and available tissue were collected from the CNDR Brain Bank at University of Pennsylvania [68]. All procedures, including autopsy and neuropathological examinations, in this study were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Patients selected for study had a primary neuropathological diagnosis of either FTLD-tau (n=94) which included Pick’s disease (PiD), corticobasal disease (CBD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), and unclassifiable tauopathies (Tau-U), or FTLD-TDP (n=135) which included FTLD-TDP Types A-E [46] and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Table 1). Patients were prospectively genotyped for pathogenic mutations on MAPT, C9orf72, GRN, and other FTD-associated genes based on a structured pedigree analysis described previously [67]. Carriers of each mutation (MAPT [n=6], C9orf72 [n=23], GRN [n=14], TBK [n=3], VCP [n=1]) met standard criteria for neuropathological subtype classification with the exception of select MAPT mutation carriers (n=4) characterized by relatively unique distributions and morphologies of tau inclusions and therefore grouped into the Tau-U subgroup. To focus our analyses on FTLD neuropathology, we excluded patients with SOD1 mutations. A minority of patients had secondary pathologic diagnoses that largely involved structures outside the brainstem (Table 1). Note that some FTLD-tau (n=51) and FTLD-TDP (n=72) patients met criteria for primary age-related tauopathy (PART) which can overlap with Not/Low-level AD neuropathologic change [18]. To examine LC neurodegeneration in our experimental FTLD groups in the context of aging and the AD spectrum, we included two clinicopathological reference groups. The AD group (n=32) consisted of patients clinically diagnosed with possible or probable AD during life and had a primary neuropathologic diagnosis of high or intermediate AD neuropathologic change [36, 54] with no secondary neuropathologic diagnosis. The healthy control (HC) group (n=19) included participants without dementia or neurologic disorders during life and an absence of a postmortem neurodegenerative pathologic diagnosis (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and pathologic characteristics.

| Cohort | Sex | Age at death (years) | Disease Duration (years) | Postmortem Interval (hours) | Mutation Status | (N) | Primary Neuropathologic Diagnoses | (N) | Secondary Neuropathologic Diagnoses | (N) | Thal Phase | (N) | Braak Stage | (N) | CERAD Score | (N) | AD Neuropathologic Change | (N) | Clinical Diagnoses | (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTLD-tau | 41/94 (43.6%) Female | 73 [68,80] ** | 7 [5,10] * | 12.5 [6.5,19] | MAPT | 6 | CBD | 20 | AGD | 1 | 0 | 44 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 61 | Not | 36 | AD | 2 |

| PiD | 12 | CVD | 3 | 1 | 23 | 1 | 34 | 1 | 16 | ALS | 3 | |||||||||

| PSP | 52 | HS | 1 | 2 | 17 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 12 | Low-level | 33 | bvFTD | 20 | |||||||

| Tau-U | 10 | LBD-A | 2 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | CBS | 18 | |||||||||

| LBD-B | 1 | N/A | 4 | N/A | 15 | N/A | 1 | Intermediate-level | 8 | DLB | 1 | |||||||||

| LBD-L | 2 | MCI | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| High-level | 2 | PD | 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| PPA | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||

| N/A | 15 | PSPS | 36 | |||||||||||||||||

| FTLD-TDP | 57/135 (42.2%) Female | 66 [61,74] | 6 [2,9] | 12 [6,17] | C9orf72 | 23 | TDP Type A | 22 | AGD | 5 | 0 | 39 | 0 | 45 | 0 | 96 | Not | 39 | AD | 7 |

| GRN | 14 | TDP Type B | 22 | CVD | 2 | 1 | 23 | 1 | 54 | 1 | 14 | ALS | 70 | |||||||

| TBK | 3 | TDP Type C | 18 | HS | 5 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 21 | 2 | 15 | Low-level | 26 | ALS-FTD | 6 | |||||

| VCP | 1 | TDP Type D | 1 | LBD-B | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 7 | bvFTD | 31 | |||||||

| TDP Type E | 1 | LBD-L | 1 | N/A | 60 | N/A | 8 | N/A | 3 | Intermediate-level | 9 | CBS | 3 | |||||||

| ALS | 71 | LBD-N | 1 | PPA | 18 | |||||||||||||||

| PSP | 1 | High-level | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| N/A | 60 | |||||||||||||||||||

FTLD = frontotemporal lobar degeneration; TDP = transactive response DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa; CERAD = Consortium to Establish a Repository for Alzheimer’s disease; MAPT = microtubule-associated protein tau; C9orf72 = short (p) arm of chromosome 9 open reading frame 72; GRN = granulin; TBK = tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor NF-kB activator (TANK)-binding kinase; VCP = valosin-containing protein. Neuropathologic diagnoses: CBD = corticobasal disease, PiD = Pick’s disease, PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy, Tau-U cases include unclassifiable tauopathies (n=7) and patients carrying a MAPT mutation on chromosome 17 (loci included: c.902C>T, p.P301L, c.796C>G, p.L266V,c.915+16C>T, p.?), AGD = argyrophilic grain disease, CVD = cerebrovascular disease, HS = hippocampal sclerosis, LBD = Lewy body disease (LBD subtypes include: A = amygdala-only, B = brainstem, L = limbic, N = neocortical). Clinical Diagnoses: AD = Alzheimer’s disease, ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, bvFTD = behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, CBS = corticobasal syndrome, DLB = dementia with Lewy Bodies, MCI = mild cognitive impairment, PD = Parkinson’s disease, PPA = primary progressive aphasia, PSPS = progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome. Data presented are patient frequency or median and interquartile ranges. Significant differences between FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP (*p<0.001, **p<0.0001)

Patients were excluded if pons tissue from autopsy was unavailable or if the pons tissue was torn in a way that precluded a reliable evaluation of the magnocellular nucleus of the LC. These stringent criteria resulted in a total of 280 cases (19 HC, 32 AD, 94 FTLD-tau, and 135 FTLD-TDP). In rare cases when bilateral LC nuclei were present in a single transverse section of pons (n=20), both LC nuclei were examined and data was averaged for use in respective analyses. Patient demographics and characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry

As described previously [64], pons tissue was processed at autopsy for diagnostics that involved immunostaining for hyperphosphorylated tau (mouse monoclonal antibody, PHF-1, 1:1000, gift from Dr. Peter Davies) and phosphorylated TDP-43 (rat antibody, ID3 p409/410, 1:1000, gift from Drs. M. Neumann and E. Kremmer) and used for semi-quantitative ratings of protein inclusion severity (see below). Paraffin-embedded pons tissue that contained the LC was cut into closely adjacent series of 6μm-thick sections for additional histochemical and immunohistochemical staining in the Penn Digital Neuropathology Lab. Histochemical staining included fresh hematoxylin for the visualization of cell organization without obscuring the rating of neuromelanin pigmentation in the LC. For the digital assessment of neuromelanin-containing noradrenergic neurons in the LC (see below), pons tissue was immunostained for tyrosine hydroxylase (rabbit antibody, TH, 1:1000, generated by the CNDR) using standard avidin–biotin complex methods without antigen retrieval and ImmPACT Vector Red Substrate (Vector Laboratories) as the chromogen. The immunostaining with TH and a magenta red chromogen permitted an unobstructed and selective digital quantification of red noradrenergic neurons readily discernible from the intrinsic brown pigment of neuromelanin. Available ethanol-fixed tissue in FTLD-tau cases was immunostained with a conformational-selective anti-tau antibody relatively specific to neurofibrillary tau in AD (mouse monoclonal antibody, GT-38, 1:1000) [28, 29] to detect the amount of age-related AD-type tau co-pathology which can be obscured by the use of antibodies for phospho-epitopes alone.

To determine the cellular localization of tau and TDP-43 inclusions in the LC, we performed a series of double-label immunofluorescence experiments using antibodies to phosphorylated tau (mouse monoclonal antibody, AT8, 1:1000, Millipore), phosphorylated TDP-43 (ID3 p409/410, 1:1000), and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, 1:1000) to visualize LC noradrenergic neurons using Alexa Fluor 488 and 594 species-specific conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes). Slides were treated with 0.3% Sudan Black solution to quench autofluoroscence and cover-slipped with Vectashield-DAPI mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). We included control slides with both secondary antibodies and one of each primary antibody to confirm no cross-reactivity between channels. A high-resolution Leica DMI6000B microscope was used to confirm signal localization with Leica LAS-X software. Digital images for immunofluorescence experiments were overlaid into a merged channel using ImageJ software (version 1.8).

Semi-quantitative assessment of neuropathology & neuromelanin in the LC

A gross examination of the pons to rate depigmentation of the LC on an ordinal scale (0=“None”, 1=“Mild”, 2=“Moderate”, 3=“Severe”) was prospectively performed in all cases at autopsy and obtained from the INDD for validation analyses. Semi-quantitative scoring of neuropathologic burden and microscopic neuronal pigment in the LC was completed using an ordinal rating scale (0–3) and blinded to patient characteristics and group designations for this study. Neuropathologic inclusion burden was evaluated in the FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP groups based on two metrics: 1) the extent of magnocellular inclusions in the somatic compartment (i.e., s-tau or s-TDP-43), and 2) the extent of neuritic and glial inclusions outside the somatic compartment of magnocellular neurons in the surrounding neuropil within the LC (i.e., ns-tau or ns-TDP-43). These individual ratings of neuropathology were averaged to calculate a composite measure of overall burden of each neuropathologic inclusion type in the LC. Composite measures of tau and TDP-43 burden in the LC were used in all main analyses and supplementary analyses. Levels of neuromelanin content in the LC are likely indicators of neurodegeneration [4, 45] and were evaluated on hematoxylin-stained slides based on two metrics: 1) intracellular depigmentation of neuromelanin, and 2) extracellular deposition of neuromelanin pigment. A composite measure of pigmented neuromelanin representing neurodegeneration of the LC was calculated by averaging the individual ratings of neuromelanin content. Individual and composite ratings of neurodegeneration were used to validate each digital measure of neuromelanin content using methods described previously (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2) [25, 40, 42].

Digital image analyses of neuromelanin to objectively measure neurodegeneration in the LC

To objectively evaluate LC neurodegeneration, we performed image analyses that digitally measured the amount of pigmented neuromelanin granules to produce continuous data of LC integrity for statistical comparisons. Both intracellular and extracellular neuromelanin were measured in pons tissue immunostained for TH using Vector Red, a magenta red chromogen utilized for its distinct color profile compared to the intrinsic brown color of neuromelanin and blue color of the hematoxylin counter stain. Tissue sections were imaged on a digital slide scanner (Aperio AT2, Leica Biosystem, Wetzlar, Germany) in the Penn Digital Neuropathology Lab at 40x magnification and images were analyzed using QuPath software (version 0.2.0-m5).

Neuromelanin was quantified within a standard region of interest (ROI) representing the magnocellular nucleus of the LC. An experienced neuroanatomist (D.T.O.) performed a systematic, manual segmentation of the LC ROI that was guided by the identification and inclusion of TH-reactive and neuromelanin-containing neurons [9, 56] and exclusion of nucleus subcoeruleus due to its inconsistent presence in available tissue across cases. The watershed cell segmentation tool in QuPath software was used to automatically identify and annotate TH-positive neurons within the LC ROI of each patient. Blinded to patient demographics, a trained investigator (C.P.), supervised by D.T.O. and D.J.I., examined each image and manually adjusted irregular neuronal contours as needed. These methods resulted in two main ROIs: the total LC ROI and the collective ROI of every annotated TH-positive neuron contained within the LC ROI. Next, neuromelanin granules were reliably detected within each ROI with two positive pixel count analyses: one developed for intracellular neuromelanin and one optimized for extracellular neuromelanin that excluded off-target artifacts in the cellular milieu. Both analyses employed a brown color vector specific to neuromelanin pigment and an optical density profile established by previously sampling a small subset of cases in each group, which were compared to blinded ordinal ratings of neuromelanin for validation (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2) as previously described [26].

Within each LC ROI, we calculated the percent area occupied (%AO) of neuromelanin as follows: intracellular neuromelanin was defined as the total number of neuromelanin-positive pixels occupying the somatic compartment of TH-positive neurons; extracellular neuromelanin was defined as the total number of neuromelanin-positive pixels occupying the area of the total LC ROI but outside TH-positive neurons. A ratio of extracellular neuromelanin-to-intracellular neuromelanin was calculated as a global composite measure of neuromelanin change in the LC where larger ratios represent more severe neurodegeneration due to more pigmented neuromelanin released into the surrounding neuropil from degenerated neurons.

Statistical Analyses

Data analyses were performed using SPSS (version 26.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Group size varied between some analyses based on availability and integrity of tissue for each marker of interest. Missing data from LC experiments due to unavailable or incomplete pons tissue are reported in all analyses. Demographics were compared using Chi-square analyses for categorical data and Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney U-tests for non-normally distributed continuous data. Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney U-tests were also used to compare non-parametric ordinal scores of neuropathologic inclusion burden and neuromelanin content between two pathologic or clinical groups. The Kruskal-Wallis test compared neuromelanin content across FTLD and reference groups. Spearman rank order correlation tested relationships between neuropathologic inclusion burden, neuromelanin content, and age at death. To account for age-related factors, we also performed multivariate logistic regression models to test the association between LC neuromelanin content and pathologic group membership while adjusting for age at death, sex, and AD tau Braak stage as covariates. Separate models were performed for each neuropathological group comparison (i.e., FTLD-tau vs. FTLD-TDP, FTLD-tau vs. HC, FTLD-tau vs. AD, FTLD-TDP vs. HC, FTLD-TDP vs. AD). All statistical tests were 2-sided and p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Demographic comparisons

All groups including FTLD (see Table 1 for summary of demographics) and reference groups (Supplementary Table 1) of HC and AD were well-matched for sex (χ(3)=4.49, p=0.21) and postmortem interval (H=6.36, p=0.095). Our FTLD-tau group had a longer disease duration (median=7, interquartile range (IQR)[5,10]; z=−3.0, p=0.003) and was significantly older (median=73, IQR[68,80]; z=−4.93, p<0.0001) than our FTLD-TDP group (median=6, IQR[2,9], median=66, IQR[61,74], respectively). The HC group was younger (median=61, IQR[56,68]) than the FTLD-TDP (z=−2.2, p=0.028) and FTLD-tau (z=−4.0, p<0.0001) and AD groups (median=79.5, IQR[70.75,84]; z=−4.28, p<0.0001). The AD group was older than the FTLD-tau group (z=−2.66, p=0.008), FTLD-TDP group (z=−5.35, p<0.0001), and HC group (z=−4.28, p<0.0001). The AD group had a similar disease duration (median=8, IQR[6,11]) compared to the FTLD-tau group (z=−1.6, p=0.11), but longer disease duration than the FTLD-TDP group (z=−3.42, p=0.001).

Neuropathologic inclusion burden in the LC

Tau neuropathology in the LC was observed in every examined FTLD-tau case which showed a predominately moderate-to-severe burden that often included pre-tangles and globose tangles in magnocellular neurons (s-tau inclusions) as well as diffuse tau inclusions in the form of neuritic threads, coiled-bodies, and astrocytic morphologies (ns-tau inclusions) (Fig. 1a). In contrast, TDP-43 neuropathology in the LC was of mostly mild severity and observed in only 67/116 cases (57.8%) of FTLD-TDP cases. TDP-43 inclusions frequently consisted of oligodendrocytic inclusions, grains, and dystrophic neurites (ns-TDP-43 inclusions), and much less often (15 individuals [11.1%]) appeared as skein-like or compact round neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (s-TDP-43 inclusions, Fig. 1b) similar in morphology to TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions in motor neurons of ALS [57].

Figure 1.

The distribution of neuropathology in the locus coeruleus of FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP. Fig. 1a Tau neuropathology visualized with PHF-1 in the locus coeruleus was observed in every FTLD-tau case with a predominately moderate-to-severe burden that often included pre-tangles (empty arrow) and globose tangles in magnocellular neurons (filled arrows) as well as diffuse tau inclusions in the form of neuritic threads, coiled-bodies, and astrocytic morphologies. Fig. 1b In contrast, TDP-43 neuropathology visualized with ID3 was infrequently observed in the locus coeruleus of FTLD-TDP patients, but when present, took the form of small grains, oligodendrocytic inclusions, or dystrophic neurites (open arrowheads) and less often (15 patients [11.1% of FTLD-TDP cohort]) compact round neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (closed arrowhead). Photomicrographs were acquired at 10x magnification with insets acquired at 40x magnification

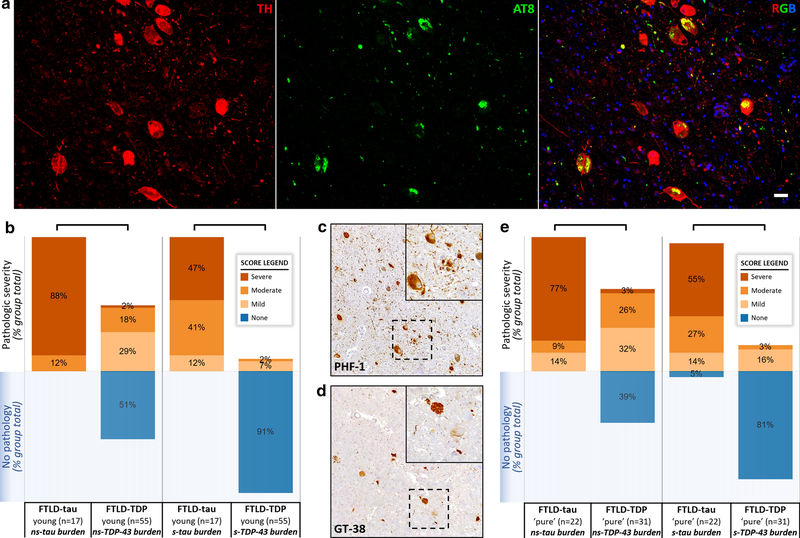

Cellular localization of tau and TDP-43 inclusions in the LC

To further characterize the cellular localization of tau and TDP-43 inclusions in the LC, double-label immunofluorescent experiments were performed in both groups. Most tau inclusions co-localized with TH-positive neuronal somas (s-tau) and neurites (ns-tau) in FTLD-tau, with some tau inclusions forming coiled-bodies and threads non-reactive to TH (Fig. 2a). In contrast, scant TDP-43 inclusions in FTLD-TDP rarely co-localized with TH-positive neurons and processes in the surrounding neuropil (ns-TDP-43), often exhibiting the size and morphology of small grains and oligodendrocytic inclusions (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Predominant localization of tau, but not TDP-43 inclusions, to TH-positive neurons in the locus coeruleus.

Fig. 2a Representative photomicrographs from double-label experiments in the locus coeruleus demonstrate that tau neuropathology visualized with AT8 was frequently localized to both the somatic and neuritic compartments of TH-positive neurons in a FTLD-tau case with PSP. Fig. 2b In contrast, TDP-43 neuropathology visualized with ID3 was in the morphology of small grains and oligodendrocytic inclusions that rarely co-localized with TH-positive neurons in the locus coeruleus of a FTLD-TDP Type A case. DAPI counterstain visualized all cell nuclei in the blue channel. Scale bars = 20μm

LC neuropathologic inclusion burden was greater in FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP

To determine if neuropathology accumulated differently in the LC of FTLD groups, we first compared the primary neuropathologic burden semi-quantitatively in the somatic compartment of LC magnocellular neurons (i.e., s-tau inclusions in FTLD-tau and s-TDP-43 inclusions in FTLD-TDP). A greater severity score of s-tau inclusions was found in FTLD-tau (median score=2, IQR=[2,3], n=82) compared to the rare s-TDP-43 inclusions in FTLD-TDP (median score=0, IQR=[0,0], n=116; z=−12.15, p<0.0001) (Fig. 2a). Next, we semi-quantitatively assessed the accumulation of neuropathology outside the somatic compartment of LC neurons in surrounding neurites and glia. Similarly, we found that the frequently severe ns-tau burden in FTLD-tau (median score=3, IQR=[2.75,3], n=82) were greater than the mostly mild ns-TDP-43 burden in FTLD-TDP (median score=1, IQR=[0,1]; z=−10.47, n=116; p<0.0001) (Fig. 2b). Composite scores of LC neuropathology (derived from the average of s-inclusion and ns-inclusion burden) recapitulated the above results such that there was a greater tau composite score in FTLD-tau (median score=2.5, IQR=[2,3], n=82) compared to the TDP composite score in FTLD-TDP (median score=0.5, IQR=[0,1], n=116; z=−11.38, p<0.0001). Thus, results herein display the composite scores of each neuropathologic burden.

Pathologic and clinical subgroup analyses of neuropathologic inclusion burden in FTLD spectrum

To confirm that a neuropathologic or clinical phenotypic subgroup was not driving the significant difference in neuropathologic burden between our main analysis comparing FTLD-tau to FLTD-TDP, we performed additional comparative analyses in FTLD subgroups. First, a pathologic subgroup analysis comparing 3R (i.e., PiD) to 4R (i.e., CBD, PSP) tauopathies found no significant differences in LC composite tau burden between 3R (median score=2.75, IQR=[2.38,3], n=10) and 4R tauopathies (median score=2.5, IQR=[2,3], n=63; z=−1.1, p=0.27), suggesting that high tau burden is a shared feature across heterogeneous FTLD-tauopathies (Fig. 3). Similarly, a clinical subgroup analysis within FTLD-tau comparing patients with primary motor syndromes (i.e., progressive supranuclear palsy [PSPS] and corticobasal syndrome [CBS]) to non-motor syndromes (i.e., behavioral variant FTD [bvFTD] and primary progressive aphasia [PPA]) showed that tau burden was not different between the motor subgroup (median score=2.5, IQR=[2,3], n=48) and non-motor subgroups (median score=2.5, IQR=[2,3], n=22; z=−0.45, p=0.65). In addition, tau burden in a subgroup of only PSPS patients (median score=2.5, IQR=[2,3], n=38) was not different than tau burden in the non-motor FTLD-tau subgroup (median score=2.5, IQR=[2,3], n=22; z=−0.44, p=0.66), suggesting that tau burden was consistently elevated across clinical phenotypes in the FTLD-tau group.

Figure 3.

Tau neuropathology is more common and severe in the locus coeruleus of FTLD-tau compared to TDP-43 in the locus coeruleus of FTLD-TDP.

Fig. 3a Semi-quantitative ratings of neuropathologic burden demonstrated that non-somatic (ns)-tau inclusion burden was greater in FTLD-tau (n=82) compared to ns-TDP-43 inclusion burden in FTLD-TDP (n=116; z=−10.47, p<0.0001). Fig. 3b Similarly, the semi-quantitative rating of somatic (s)-tau inclusion burden was greater in FTLD-tau (n=82) compared to s-TDP inclusion burden in FTLD-TDP (n=116; z=−12.15, p<0.0001). While all pathologic subtypes of FTLD-tau (i.e., CBD, PiD, PSP, Tau-U) consistently displayed elevated burdens of both ns-tau and s-tau inclusions, the TDP-43 burden in FTLD-TDP group was more heterogeneous, with a greater burden of ns-TDP inclusions in FTLD-TDP cases without clinical/pathologic ALS features compared to FTLD-TDP cases with ALS features (z=−4.86, p<0.0001; Fig. 3c,d). FTLD-TDP Types TDP-D (n=1) and TDP-E (n=1) not shown. Brackets indicate significant group-level differences between FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP (p<0.0001) or between FTLD-TDP subgroups with or without clinical/pathologic ALS features (*p<0.0001)

Next, we performed a subgroup analysis of the FTLD-TDP group that showed that FTLD-TDP patients with Types A-E combined (median score=0.5, IQR=[0.5,1], n=59) had a mild but significantly greater composite score of LC TDP-43 inclusions than pathologically-confirmed ALS patients with clinical ALS/ALS-FTD diagnoses (median score=0, IQR=[0,0.5], n=57; z=−4.99, p<0.0001) (Fig. 3). To confirm that the ALS subgroup was not driving differences in pathologic burden between FTLD groups, we excluded all pathologically/clinically-confirmed ALS patients and still found that the composite score of tau burden in FTLD-tau (median score=2.5, IQR=[2,3], n=82) was significantly greater than the composite score of TDP-43 burden in the remaining FTLD-TDP group (i.e., Types A-E combined) without pathologic/clinical ALS features (median score=0.5, IQR=[0.5,1], n=59; z=−9.23, p<0.0001).

Age-related neurofibrillary tau is not a major contributor to tau burden in LC for majority of FTLD-tau patients

Since the LC may be an early site of tau deposition in the aging and AD spectrum [12, 13], we sought to confirm that the high neuropathologic tau burden in FTLD-tau was relatively specific to non-AD tauopathies (i.e., FTLD-tau) and not a product of age-related tau accumulation that can be difficult to distinguish using tau phospho-epitope antibodies. First, we examined exceptionally young FTLD-tau patients with available LC tissue, including individuals with age at death in their thirties, and found severe tau neuropathology in LC neurons and surrounding neuropil in excess of the scant pre-tangle pathology expected for young individuals (Fig. 4a). We also performed a subanalysis of FTLD patients aged 65 years and younger at death. In these young-onset subgroups of FTLD-tau (median=62, IQR[57.5,64.5]) and FTLD-TDP (median=61, IQR[55,63]) with similar ages (z=−0.83, p=0.41), we found equivalently low Braak stages in both FTLD groups (median=0, IQR[0,1]; z=−1.08, p=0.28), but greater tau burden (median score=2.5, IQR[2.25,3]) in the LC of FTLD-tau (n=17) compared to TDP-43 burden (median score=0.5, [0,0.5]) in the LC of FTLD-TDP (n=55; z=−6.38, p<0.0001) (Fig. 4b). These findings in exceptionally young patients suggest that FTLD-type tau likely comprises most of the severe LC tau burden observed in FTLD-tau.

Figure 4.

Age-related neurofibrillary tau is not a major contributor to tau burden in the locus coeruleus for majority of FTLD-tau patients.

Fig. 4a Double-label experiment in the locus coeruleus of a FTLD-tau patient with a MAPT mutation displayed severe AT8-positive tau neuropathology in TH-positive neurons and in surrounding neuropil unexpected for age-related or AD-type tau neuropathology given their young age at death of 34. DAPI counterstain visualized all cell nuclei in the blue channel. Scale bar = 20μm. Fig. 4b In young-onset (≤65 years old at death) FTLD groups with equivalently low Braak stage, semi-quantitative ratings of neuropathologic burden demonstrated that non-somatic (ns)-tau inclusion burden was greater in young-onset FTLD-tau (n=17) compared to ns-TDP-43 inclusion burden in young-onset FTLD-TDP (n=55; z=−6.21, p<0.0001). Similarly, the semi-quantitative rating of somatic (s)-tau inclusion burden was greater in young-onset FTLD-tau (n=17) compared to s-TDP inclusion burden in young-onset FTLD-TDP (n=55; z=−7.64, p<0.0001), suggesting that age-related tau is an insignificant contributor to the severe tau burden in the locus coeruleus of FTLD-tau. Fig. 4c Age-related, AD-type tau visualized by the GT-38 antibody was infrequent, comprising a small subset of total pathologic tau as visualized with the PHF-1 antibody in an FTLD-tau patient with PSP (Fig. 4d). Photomicrographs in panels c and d were acquired at 10x magnification with insets acquired at 40x magnification. Fig. 4e After exclusion of FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP cases with mild-to-severe age-related tau co-pathology in the locus coeruleus, remaining cases with ‘pure’ FTLD-tau and ‘pure’ FTLD-TDP in the locus coeruleus still showed greater tau burden in FTLD-tau (n=22) compared to TDP-43 burden in FTLD-TDP (n=31; z=−5.75, p<0.0001). Significant group-level difference between FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP indicated by brackets (p<0.0001)

Next, we examined available adjacent LC tissue in the FTLD-tau group using the GT-38 conformation-selective tau antibody to detect AD-type tau pathology and found that it comprised a small subset of total tau visualized with PHF-1 (Fig. 4c,d). Additionally, age directly correlated with GT-38 tau burden (n=49, rho=0.57, p<0.0001) in FTLD-tau, suggesting that GT-38 was reliably detecting age-related tau pathology in the LC. We found GT-38-positive tau co-pathology in 53% of available FTLD-tau cases (26/49) in mostly mild severity (47% of available FLTD-tau cases). To further account for the age-related neurofibrillary tau in both FTLD groups, we performed a supplemental analysis that excluded patients with a mild-to-severe burden of GT-38-positive AD-type tau co-pathology in the LC of FTLD-Tau and patients with mild-to-severe PHF-1-positive tau co-pathology in the LC of FTLD-TDP. These remaining cases with relatively ‘pure’ FTLD-tau and ‘pure’ FTLD-TDP in the LC still showed a greater composite rating of tau burden in FTLD-tau (median score=3, IQR=[2,3], n=22) compared to the composite rating of TDP-43 burden in FTLD-TDP (median score=0.5, IQR=[0,1], n=31; z=−5.75, p<0.0001), suggesting that age-related tau pathology was not driving differences in neuropathologic burden between groups (Fig. 4e).

Finally, we compared Braak stage between FTLD-tau (n=44) and AD (n=15) subgroups with similar LC tau burden (only cases with relatively high moderate-to-severe LC tau burden were compared) and found that Braak stage was lower in the FTLD-tau group (median=B1, [B0,B1]) compared to the AD group (median=B3, IQR[B3,B3]; z=−5.94, p<0.0001), suggesting that age-related tau pathology was minimal in the LC of FTLD-tau patients with even high LC tau burden.

LC neuromelanin content

To measure LC integrity in a manner independent of protein inclusion burden, we first examined the amount of neuromelanin content in the LC to determine the extent of neurodegeneration by first semi-quantitatively rating the degree of neuronal depigmentation and extracellular deposition of neuromelanin in the LC blinded to patient diagnoses and group designation. The FTLD-tau group displayed greater ratings of depigmentation (median score=1, IQR=[0,1], n=79) and extracellular neuromelanin (median score=1, IQR=[1,2]) compared to the FTLD-TDP group (median score=0, IQR=[0,1], n=109, z=−4.03, p<0.0001; median score=1, IQR=[0,1]; z=−4.31, p<0.0001, respectively). These findings were consistent with gross ratings of LC pallor/depigmentation recorded prospectively at autopsy that showed more severe depigmentation of the LC in FTLD-tau (median score=0, IQR[0,1]; n=87) compared to FTLD-TDP patients (median score=0, IQR[0,0]; n=130, z=−4.23, p<0.0001).

Next, we performed digital image analyses to quantify the amount of LC neuromelanin pigment within TH-positive neurons and in the surrounding neuropil of the LC (Fig. 5a,b). Using previously described methods to validate our digital measurements [25, 40, 42], we found that each digital measure of neuromelanin content (i.e., %AO of intracellular and %AO of extracellular neuromelanin) correlated with our blinded ordinal ratings (i.e., depigmentation and extracellular pigment, respectively, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, the composite rating of neuromelanin content (i.e., averaged ratings of depigmentation and extracellular pigment) correlated with the ratio of the %AO of extracellular neuromelanin to the %AO of intracellular neuromelanin, henceforth referred to as the “ratio of neuromelanin content” representing a composite digital measure of neurodegeneration (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). Results herein display the ratio of digitally measured neuromelanin content, and Supplementary Tables 8–11 provide the results from all analyses that included individual digital metrics of %AO of intracellular and extracellular neuromelanin with largely similar results.

Figure 5.

Neuromelanin content in the locus coeruleus indicates greater neurodegeneration in FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP.

Fig. 5a Representative photomicrographs of the locus coeruleus from a FTLD-tau patient and a FTLD-TDP patient immunostained for TH using a red chromogen to identify noradrenergic neurons for digital analyses of intracellular neuromelanin content in addition to extracellular neuromelanin granules as small as microns in diameter. Fig. 5b Red overlay represents positive-pixel detection of neuromelanin for digital quantification. TH-positive neurons frequently had relatively less intracellular neuromelanin (black arrows) but more extracellular neuromelanin (empty arrows) in surrounding neuropil of the locus coeruleus in FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP. Scale bars = 20μm Fig. 5c The ratio of extracellular-to-intracellular neuromelanin detected locus coeruleus neurodegeneration in FTLD-tau (blue box, n=82) similar to an AD reference group (red bar, n=29), but was greater than what was measured in FTLD-TDP (green box, n=117) and a healthy control (HC) reference group (yellow bar, n=19). Fig. 5d Neurodegeneration remained higher in the locus coeruleus of ‘pure’ FTLD-tau compared to ‘pure’ FTLD-TDP, suggesting that individuals with co-morbid age-related neurofibrillary tau were not driving group-level differences. Fig. 5e Similarly, the ratio of neuromelanin content remained greater in young-onset (≤65 years old at death) FTLD-tau compared to young-onset FTLD-TDP with equivalently low Braak stages in both FTLD groups, further suggesting that FTLD-related tau is the likely contributor to the severe locus coeruleus neurodegeneration observed in FTLD-tau. Solid reference lines represent the medians and dotted lines represent the upper and lower quartiles for HC (yellow) and AD (red) reference groups. Significant group-level differences between FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP denoted by brackets (p<0.0001, Fig. 5c,e; p=0.03, Fig. 5d), group-level differences with HC reference group denoted by # (p<0.005, Fig. 5c,d), and group-level differences with AD reference group denoted by * (p<0.001)

LC neurodegeneration was greater in FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP

There was a statistically significant difference in neurodegeneration (ratio of neuromelanin content) between all groups as determined by a Kruskal-Wallis test (H=44.6, p<0.0001). Individual group comparisons showed that the ratio of neuromelanin content was larger in FTLD-tau (median=0.002, IQR=[0.001,0.004], n=82) compared to FTLD-TDP (median=0.001, IQR=[0.001,0.002], n=117; z=−3.85, p<0.0001), suggesting greater degeneration of TH-positive neuromelanin-containing neurons in FTLD-tau. As expected, the ratio of neuromelanin content was larger in FTLD-tau compared to HC (median=0.001, IQR=[0.0004,0.001 ], n=19; z=−4.12, p<0.0001). Likewise, the ratio of neuromelanin content was larger in AD (median=0.003, IQR=[0.002,0.005], n=29) than in FTLD-TDP (z=−5.02, p<0.0001). The AD and FTLD-tau groups did not show a significant difference in the ratio of LC neuromelanin content (z=−1.84, p>0.05). While neurodegeneration was significantly less in FTLD-TDP compared to FTLD-tau and AD, the low level of neurodegeneration was greater in FTLD-TDP compared to HC (z=−2.77, p=0.006) (Fig. 5c).

Pathologic and clinical subgroup analyses of neuromelanin content in FTLD spectrum

To determine if neurodegeneration was a consistent feature across pathologic and clinical subgroups of FTLD-tau, we compared the ratio of neuromelanin content between 3R and 4R tauopathies, and between motor and non-motor syndrome subgroups. First, the pathologic subgroup analysis of isoform-specific tauopathies found no significant difference in the ratio of neuromelanin content between 3R (median=0.002, IQR=[0.0008,0.004], n=9) and 4R (median=0.002, IQR=[0.0008,0.004], n=63; z=−0.32, p=0.75) groups, suggesting that neurodegeneration is a common feature of all forms of FTLD-tauopathies. Similarly, a clinical subgroup analysis within FTLD-tau comparing patients with primary motor syndromes (i.e., PSPS and CBS) to non-motor syndromes (i.e., bvFTD and PPA) showed that the ratio of neuromelanin content was not different between the motor subgroup (median=0.002, IQR=[0.0008,0.004], n=50) and non-motor subgroup (median=0.002, IQR=[0.001,0.004], n=21; z=−0.2, p=0.84). In addition, the ratio of neuromelanin content in a subgroup of only PSPS patients (median score=0.002, IQR=[0.001,0.004], n=42) was not different than LC neurodegeneration in the non-motor FTLD-tau subgroup (median=0.002, IQR=[0.001,0.004], n=21; z=−0.06, p=0.95), suggesting that elevated LC neurodegeneration is consistent across clinical syndromes and pathologic subtypes in the FTLD-tau group.

When we performed a subgroup analysis in the FTLD-TDP group, we found a significantly greater ratio of neuromelanin content in the LC of FTLD-TDP patients with Types A-E (median=0.002, IQR=[0.001,0.002], n=54) compared to pathologically-confirmed ALS patients with clinical ALS/ALS-FTD diagnoses (median=0.001, IQR=[0.001,0.002], n=63; z=−2.41, p=0.02). To minimize the possibility that the low neuropathologic burden and neurodegeneration in the pathologically- and clinically-confirmed ALS subgroup was driving the minimal neurodegeneration in the total FTLD-TDP compared to FLTD-tau, we performed an additional analysis that excluded pathologically/clinically-confirmed ALS patients from the FTLD-TDP group. We found the that ratio of neuromelanin content in FTLD-tau (median=0.002, IQR=[0.001,0.004], n=82) was still significantly greater than the ratio of neuromelanin content in the FTLD-TDP subgroup without pathologic and clinical ALS features (median=0.002, IQR=[0.001,0.002], n=54; z=−2.02, p=0.044).

To determine our results were not driven by AD-type tau co-pathology, we first examined FTLD subgroups with relatively ‘pure’ FTLD-tau and ‘pure’ FTLD-TDP (i.e., exclusion of FTLD cases with mild-to-severe AD-type tau co-pathology in the LC) and found a similar pattern of results. Specifically, the ratio of neuromelanin content was greater in ‘pure’ FTLD-tau (median=0.002, IQR=[0.0008,0.004], n=20) compared to ‘pure’ FTLD-TDP (median=0.001, IQR=[0.0005,0.002], n=34; z=−2.17, p=0.03, Fig. 5d). As expected, the ratio of neuromelanin content was larger in ‘pure’ FTLD-tau compared to HC (median=0.001, IQR=[0.0004,0.001], n=19; z=−2.98, p=0.003). Likewise, the ratio of neuromelanin content was larger in AD (median=0.003, IQR=[0.002,0.005], n=29) than in ‘pure’ FTLD-TDP (z=−4.22, p<0.0001). The AD and ‘pure’ FTLD-tau groups showed a comparable amount of neurodegeneration (z=−1.30, p>0.05), as did the neurodegeneration between the HC and ‘pure’ FTLD-TDP groups (z=−1.93, p>0.05) (Fig. 5d).

Next, we performed a subanalysis on age-matched FTLD patients aged 65 years and younger at death with equivalently low Braak stages in both FTLD groups and still found greater neurodegeneration (median=0.004, [0.002, 0.005]) in the LC of FTLD-tau (n=15) compared to neurodegeneration (median=0.001, [0.001, 0.002]) in the LC of FTLD-TDP (n=54; z=−3.81, p<0.0001) (Fig. 5e). Likewise, a comparison of FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP subgroups that excluded patients with co-morbid disease (Table 1) produced similar findings of greater LC neurodegeneration in the FTLD-tau subgroup (Supplementary Table 8).

Finally, we further accounted for potential age-related influences on LC neuromelanin content using multivariate logistic regression models including age, sex, and Braak stage as co-variates and found similar results to our univariate analyses between groups above. Whereas a greater ratio of neuromelanin content was associated with FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP (Beta=566.2, SE=123.6, p<0.0001) and with FTLD-tau compared to HC (Beta=1485.8, SE=491.4, p=0.002), the ratio of neuromelanin content was not associated with FTLD-tau compared to AD (Beta=−605.6, SE=502.4, p=0.228), suggesting that LC neurodegeneration is similar across tauopathies even after accounting for age-related demographics. Furthermore, the ratio of neuromelanin content was not significantly associated with FTLD-TDP in comparison to HC after adjusting for age-related demographics (Beta=824.4, SE=427.4, p=0.054; see Supplementary Tables 3–7 for full models).

Relationships between LC neuropathology and neurodegeneration

In the total FTLD group, the semi-quantitative composite rating of tau burden positively correlated with the ratio of neuromelanin content representing neurodegeneration in the LC (rho=0.24, p=0.001). Moreover, the composite rating of tau burden had an inverse correlation with the %AO intracellular neuromelanin in the total FTLD group (rho=−0.22, p=0.004) and FTLD-tau group (rho=−0.28, p=0.02). In contrast, neither TDP-43 nor tau co-pathologic burden correlated with any measure of neuromelanin content in the FTLD-TDP group (Supplementary Table 11). These relationships remained consistent in the ‘pure’ FTLD subgroups that excluded patients with co-morbid age-related tau such that the composite rating of tau burden had an inverse correlation with the %AO intracellular neuromelanin in the ‘pure’ FTLD-tau subgroup (rho=−0.56, p=0.01), whereas no pathologic burden correlated with measures of neuromelanin content in the ‘pure’ FTLD-TDP subgroup (Supplementary Table 11). Finally, we did not find any association between age at death and LC neurodegeneration in either FTLD-tau or FTLD-TDP (Supplementary Table 11), further suggesting that age did not drive group-level differences in LC neurodegeneration.

DISCUSSION

Despite the well-known susceptibility of the LC to neurodegeneration related to tau in AD [10, 13, 19, 23, 51, 62, 63, 70], the integrity of the LC has not been thoroughly investigated in the full FTLD spectrum where tau and TDP-43 proteinopathies characterize the majority of pathologic diagnoses associated with the clinical spectrum of FTD. The current investigation found converging evidence of severe tau accumulation associated with prominent and consistent neurodegeneration in the LC of the FTLD-tau spectrum, which was distinct from the minimal neuropathology and neurodegeneration measured in the LC within the FTLD-TDP spectrum. AD and FTLD-tau displayed comparable LC neurodegeneration suggesting that multiple tauopathies have a shared predilection for LC neurons that may contribute to noradrenergic neurodegeneration. These findings have important implications for potential models of disease spread in the clinically heterogeneous FTD spectrum where distinct FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP proteinopathies can cause similar FTD phenotypes such as bvFTD.

Previous studies have reported inconsistent patterns of neurodegeneration in the LC of FTD patients. This may be due, in part, to investigating groups insufficient in size that are incapable of capturing the clinical and pathologic heterogeneity characteristic of the FTD spectrum, or that underlying pathology was incompletely characterized or unknown in the examined clinical FTD groups. For instance, one investigation found a small reduction in LC neuronal density in FTD patients with unconfirmed neuropathologic diagnoses compared to healthy controls, but this difference did not remain after controlling for age [69]. Another study reported that LC neurodegeneration in FTD patients with unconfirmed neuropathologic diagnoses was less severe than patients with AD or PD/DLB [32]. Findings such as these may have been ambiguous because these FTD clinical groups likely contained patients with a mix of FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP neuropathology, obscuring the large group-wise differences within the FTLD spectrum that was evident in our well-powered, pathology-defined groups. In contrast, patients with autopsy-confirmed PiD, CBD, and PSP have shown that tau neuropathology and neurodegeneration are common to the LC [1, 22, 27, 39, 43]. This includes a recent comparative investigation that reported more tau inclusions in the LC of 4R tauopathies (i.e., CBD and PSP) compared to healthy controls and AD patients, but neuronal densities were similar to healthy controls [20]. Furthermore, large regional analyses have found preliminary evidence of a relatively intact LC in bvFTD [14] and ALS patients [15] with confirmed FTLD-TDP neuropathology, but a dedicated study of the LC in FTLD-TDP is lacking. The current comparative study expands these findings by including a large heterogeneous group of sporadic and familial forms of tauopathies to show that severe tau neuropathology and neurodegeneration are defining features of the LC shared among 3R and 4R tauopathies and distinct from FTLD-TDP and its subgroups.

Divergent patterns of neuropathology and neurodegeneration in the LC of FTLD-tau versus FTLD-TDP patients may reflect distinct patterns of disease spread and regional vulnerability in the FTLD spectrum. As expected for the widespread efferents and afferents of the LC, animal models demonstrate that injection of pre-formed fibrils of tau into neocortex, striatum, or hippocampus results in significant tau pathology in the LC [37], while the converse experiment involving injection of tau fibrils into the LC induces templated transmission of pathologic tau into distant, synaptically-connected cortical regions and noradrenergic neurodegeneration [38]. Therefore, regardless of where tau pathology may originate, the LC appears to be prone to prominent tau aggregation, which is consistent with the severe neurodegeneration and tau pathology localized to TH-positive neurons we found in the LC throughout our FTLD-tau group. In contrast, TDP-43 proteinopathies often spare brainstem regions including the LC [14, 15] and some evidence supports spreading via corticofugal pathways in some patients with ALS [11]. Our observations of scant TDP-43 inclusions that rarely co-localized with TH-positive neurons, coupled with insignificant neurodegeneration of the LC in FTLD-TDP, support these previous findings of minimal propagation of TDP-43 to the brainstem. While inferring patterns of disease spread from cross-sectional human autopsy data has its limitations, detailed comparative neuroanatomic studies such as this can inform animal and cell model work to elucidate mechanistic causes for disease progression in these distinct proteinopathies.

One potential interpretation of our results is that differences between FTLD groups could be strongly influenced by age-related neurofibrillary tau pathology in the LC that can be obscured by FTLD-type tau pathology using traditional phospho-tau-specific antibodies in FTLD. However, upon examination of tau reactivity using the GT-38 antibody that consistently detects AD-type tau pathology [28, 29], we found minimal GT-38 reactivity that correlated with age in the FTLD-tau group. Moreover, after exclusion of FTLD-tau cases with mild-to-severe GT-38-positive tau in the LC and FTLD-TDP cases with mild-to-severe co-morbid tau in the LC, tau burden was still significantly greater in the ‘pure’ FTLD-tau group compared to the TDP-43 burden in the ‘pure’ FTLD-TDP group (Fig. 4e). Likewise, greater LC neurodegeneration was observed in the relatively ‘pure’ FTLD-tau group compared to the ‘pure’ FTLD-TDP group (Fig. 5d). While tau neuropathology and neurodegeneration may occur in the LC of aged individuals with or without a tauopathy [49, 55, 58, 65], our findings suggest that primary FTLD tauopathies consistently produce moderate-to-severe levels of tau inclusions associated with cellular changes independent of age. The inclusion of young FTLD-tau patients in their 4th-to-6th decades of life that showed severe LC tau pathology despite low Braak stage (Table 1, Fig. 4a,b; Fig. 5e) further exemplifies the minimal impact of age-related tau neurodegeneration in the LC of these groups.

Neuromelanin is a byproduct of oxidative polymerization of catecholamines including norepinephrine [66] and virtually all noradrenergic neurons of the LC contain neuromelanin [24]. Neuromelanin content likely reflects neurodegenerative processes given that investigations of neuromelanin-rich brain regions such as the substantia nigra have shown that a rise in extracellular neuromelanin correlates with neuronal loss and neuroinflammatory processes [4, 45]. In addition, the amount of intracellular neuromelanin granules appears to vary across LC neurons in a way that may be dependent on age and disease status [34, 50]. These observations are consistent with pallor of the substantia nigra or locus coeruleus, gross evaluations routinely made by neuropathologists at autopsy that likely indicate a visible reduction in neuromelanin-containing neurons of the respective catecholaminergic brain structures. In fact, prospective ratings of LC pallor made from gross inspections at autopsy showed greater pallor/depigmentation on average in our FTLD-tau group compared to FTLD-TDP.

Neuromelanin content was further examined in a quantitative manner by performing digital image analyses to measure the severity of neurodegeneration in the context of neuropathologic burden. Digital analyses were validated with independent semi-quantitative ratings of depigmentation of the LC in adjacent sections (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2)[25, 40, 42]. We found that the ratio of extracellular-to-intracellular neuromelanin in the LC was greater in the FTLD-tau group compared to the FTLD-TDP group, suggesting that the relatively larger proportion of extraneuronal neuromelanin reflected greater neurodegeneration of the LC in FTLD-tau. After stratifying the FTLD-tau group for analyses of motor vs. non-motor clinical syndromes and 3R vs. 4R tauopathies, we found that tau burden and neurodegeneration remained equivalently high across clinical and pathologic subgroups, including a pathologically confirmed subgroup of PSP patients with clinical PSPS. These findings are in agreement with a recent study showing selective noradrenergic degeneration of the LC in PSP with clinical Richardson’s syndrome or atypical clinical variants [43].

Importantly, changes to neuromelanin content were related to greater tau burden in the total FTLD-tau group, but not TDP-43 burden in the total FTLD-TDP group, further implicating FTLD-tauopathy with neurodegeneration of the LC. To confirm our observations were specific to FTLD-tauopathies, we carefully examined age and other factors that could influence our measures of LC neurodegeneration. For example, the comparison of ‘pure’ FTLD groups excluding cases with co-morbid age-related tau in the LC suggested that LC neurodegeneration is a prominent feature of FLTD-tau (Fig. 4e). However, age-related factors may have influenced LC neurodegeneration in a way incompletely accounted for by immunohistochemical techniques using AD-specific antibodies such as GT-38. Thus, we performed additional analyses including a subanalysis of young-onset FTLD patients aged 65 and younger and found that LC tau pathology and neurodegeneration remained greater in FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP (Fig. 4b, 5e). Furthermore, this difference in LC neurodegeneration between FTLD groups was supported by additional multivariate regression models accounting for age-related demographics (Supplementary Tables 3–7). These multivariate models found that LC neurodegeneration is similar between FTLD-tau and AD groups, and LC neurodegeneration is comparable between FLTD-TDP and HC groups, supporting findings produced by comparing ‘pure’ FTLD subgroups with minimal AD tau pathology in the LC (Fig. 5d). Additionally, we compared Braak stages between FTLD-tau and AD patients with relatively high LC tau burden (moderate-to-severe LC tau scores) and found a lower Braak stage in the FTLD-tau group compared to the AD group. These findings further suggest that co-morbid age-related neurofibrillary tau pathology is minimal and an insignificant contributor to the LC neurodegeneration in the majority of our FTLD-tau group. Therefore, our results highlight a more direct link between LC neurodegeneration and FTLD-type tau pathology that was consistent with our total group-level differences. Finally, a small number of patients had mixed neuropathology (Table 1) that could potentially contribute to our findings. However, after excluding these patients with co-morbid disease, we found LC neurodegeneration remained greater in FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP subgroups (Supplementary Table 8). These data provide converging evidence that neither age-related nor co-morbid disease processes served significant roles in the LC pathology and neurodegeneration we observed between FTLD groups.

We found a mild level of LC neurodegeneration in the total FTLD-TDP group which was relatively intermediate to levels found in HC and FTLD-tau (Fig. 5c). The etiology of this relatively low level of neurodegeneration is not clear as we did not find a correlation of LC neurodegeneration with age, TDP-43 burden, or AD-type tau co-pathologic burden and LC neurodegeneration in the FTLD-TDP group (Supplementary Table 11). However, LC neuromelanin content was more similar between FTLD-TDP and HC groups after adjusting for age-related demographics (Supplementary Table 6). Therefore, mild age- or AD-related neurofibrillary tau may alone or together contribute, in part, to the mild level of neurodegeneration we measured in the total FTLD-TDP group considering we found no significant difference in LC neuromelanin content between the HC and ‘pure’ FTLD-TDP group that lacked age-related co-morbid tau burden in the LC (Fig. 5d). Another possibility is the observed heterogeneity within the FTLD-TDP group where we found that the ALS subgroup had less TDP-43 and neurodegeneration in the LC than the FTLD-TDP subgroup. This finding may suggest that TDP-43 neuropathology could spread in divergent patterns between those with ALS or FTLD-TDP without ALS by mechanisms that need further elucidation [14, 15, 61]. Interestingly, the ALS subgroup was also younger in comparison to the FTLD-TDP Types A-E subgroup (data not shown), which may have influenced the difference in pathologic burden and neurodegeneration in the LC found between FTLD-TDP subgroups. While it is possible that the current study did not capture other age-related factors potentially contributing to these patterns of LC integrity, we consistently found that LC neurodegeneration in the HC and FTLD-TDP groups were relatively minimal and distinct from the severe neurodegeneration observed across the FTLD-tau subgroups and AD group.

Given that current clinical criteria do not reliably predict underlying proteinopathies such as FTLD-tau and FLTD-TDP, the discovery of antemortem biomarkers are invaluable to help differentiate these proteinopathies early during life when personalized medicine approaches should be most effective [41]. One way to support this biomarker development is through postmortem investigations designed to identify a clinically relevant marker selectively vulnerable in one disease population (e.g., FTLD-tau) versus another (e.g., FTLD-TDP). The compromised LC in FTLD-tau patients, in contrast to the relative preservation of the LC in FTLD-TDP, may be the basis for such a biomarker if validated with non-invasive neuroimaging techniques such as those leveraging the inherent paramagnetic properties of neuromelanin [7, 8, 17, 44, 47, 59]. Once confirmed during life, LC integrity may play a key role in developing a sensitive, early biomarker used in combination with other neuroimaging, biofluid, and genetic analyses to improve diagnoses especially needed in the clinically heterogeneous spectrum of FTD.

The current study had several limitations. First, while we utilized a very large sample size (n=280), assessments of neuropathology and neurodegeneration were separately derived from single sections adjacent to one another due to limited availability of tissue per case. Investigations involving a large series of thicker tissue spanning a greater extent of the rostral-caudal axis of the LC would provide the means for more quantitative and even stereologic estimates of cellular and neuropathologic changes. However, detailed stereological approaches become prohibitive in statistically well-powered studies requiring this large size and scope. Second, analyses of some subgroups were limited to some extent by postmortem sample sizes acquired from rare cohorts representing over 30 years of coordinated brain banking efforts across clinical subspecialties to uniquely capture the full spectrum of clinical and pathologic heterogeneity characteristic of FTLD. As a result, the current study included a diverse and representative sampling of FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP groups that were well-powered to detect prominent differences in neuropathology and neurodegeneration between FTLD groups and subgroups.

In conclusion, our investigation revealed novel, converging evidence of a significant amount of tau neuropathology and neurodegeneration in the LC of FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP where LC neurodegeneration was associated with FTLD-type tau inclusions and not TDP-43 pathology. These observations were evident regardless of the subtype of FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP. Thus, preferential LC neurodegeneration in FTLD-tau compared to FTLD-TDP may inform selective diagnostic biomarkers and potential therapies for symptom management in living patients with FTD. Future comparative studies of other cell populations may highlight other important distinctions between FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP that could inform diagnostics and ultimately treatments for this incurable spectrum of neurodegenerative conditions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We greatly appreciate the technical assistance provided by John Robinson, Theresa Schuck, and Alejandra Bahena. We thank Dr. Peter Davies for his generous gift of the PHF-1 antibody and Drs. M. Neumann and E. Kremmer for their generous gift of the ID3 p409–410 antibody. We also thank the patients and families who participated in the brain donation program, for without their deeply meaningful contribution to research, this study would not be possible.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from NIH grants R01-NS109260, P30-AG10124, P01-AG017586-01, R01-AG054519-02, R01-AG038490, U01-AG052943, U19-AG062418, Penn Institute on Aging, the Wyncote Foundation, and former P50-NS053488 and P01-AG032953.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

DECLARATIONS

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of University of Pennsylvania Internal Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Availability of data and materials: The datasets collected and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arima K, Akashi T (1990) Involvement of the locus coeruleus in Pick’s disease with or without Pick body formation. Acta Neuropathol 79: 629–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong MJ, Litvan I, Lang AE, Bak TH, Bhatia KP, Borroni B, Boxer AL, Dickson DW, Grossman M, Hallett M, et al. (2013) Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology 80: 496–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aston-Jones G, Ennis M, Pieribone VA, Nickell WT, Shipley MT (1986) The brain nucleus locus coeruleus: restricted afferent control of a broad efferent network. Science 234: 734–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beach TG, Sue LI, Walker DG, Lue LF, Connor DJ, Caviness JN, Sabbagh MN, Adler CH (2007) Marked microglial reaction in normal aging human substantia nigra: correlation with extraneuronal neuromelanin pigment deposits. Acta Neuropathol 114: 419–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benarroch EE (2009) The locus ceruleus norepinephrine system: functional organization and potential clinical significance. Neurology 73: 1699–1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD (2003) The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Rev 42: 33–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betts MJ, Cardenas-Blanco A, Kanowski M, Jessen F, Düzel E (2017) In vivo MRI assessment of the human locus coeruleus along its rostrocaudal extent in young and older adults. NeuroImage 163:150–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betts MJ, Kirilina E, Otaduy MCG, Ivanov D, Acosta-Cabronero J, Callaghan MF, Lambert C, Cardenas-Blanco A, Pine K, Passamonti L, et al. (2019) Locus coeruleus imaging as a biomarker for noradrenergic dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain 142: 2558–2571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogerts B (1981) A brainstem atlas of catecholaminergic neurons in man, using melanin as a natural marker. The Journal of Comparative Neurology 197: 63–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bondareff W, Mountjoy CQ, Roth M (1981) Selective loss of neurones of origin of adrenergic projection to cerebral cortex (nucleus locus coeruleus) in senile dementia. Lancet 1: 783–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braak H, Brettschneider J, Ludolph AC, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Del Tredici K (2013) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—a model of corticofugal axonal spread. Nat Rev Neurol 9: 708–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braak H, Del Tredici K (2010) The pathological process underlying Alzheimer’s disease in individuals under thirty. Acta Neuropathol 121: 171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K (2011) Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 70: 960–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Irwin DJ, Grossman M, Robinson JL, Toledo JB, Fang L, Van Deerlin VM, Ludolph AC, Lee VMY, et al. (2014) Sequential distribution of pTDP-43 pathology in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). Acta Neuropathol 127: 423–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Toledo JB, Robinson JL, Irwin DJ, Grossman M, Suh E, Van Deerlin VM, Wood EM, Baek Y, et al. (2013) Stages of pTDP-43 pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 74: 20–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IRA, Neumann M, Lee VMY, Hatanpaa KJ, White CL, Schneider JA, Grinberg LT, Halliday G, et al. (2007) Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol 114: 5–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clewett DV, Lee T-H, Greening S, Ponzio A, Margalit E, Mather M (2016) Neuromelanin marks the spot: identifying a locus coeruleus biomarker of cognitive reserve in healthy aging. Neurobiol Aging 37: 117–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crary JF, Trojanowski JQ, Schneider JA, Abisambra JF, Abner EL, Alafuzoff I, Arnold SE, Attems J, Beach TG, Bigio EH, et al. (2014) Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol 128: 755–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehrenberg AJ, Nguy AK, Theofilas P, Dunlop S, Suemoto CK, Di Lorenzo Alho AT, Leite RP, Diehl Rodriguez R, Mejia MB, Rub U, et al. (2017) Quantifying the accretion of hyperphosphorylated tau in the locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe nucleus: the pathological building blocks of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropath Appl Neuro 29: 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eser RA, Ehrenberg AJ, Petersen C, Dunlop S, Mejia MB, Suemoto CK, Walsh CM, Rajana H, Oh J, Theofilas P, et al. (2018) Selective Vulnerability of Brainstem Nuclei in Distinct Tauopathies: A Postmortem Study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 77: 149–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foote SL, Bloom FE, Aston-Jones G (1983) Nucleus locus ceruleus: new evidence of anatomical and physiological specificity. Physiol Rev 63: 844–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forno LS, Eng LF, Selkoe DJ (1989) Pick bodies in the locus ceruleus. Acta Neuropathol 79: 10–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.German DC, Manaye KF, White CL, Woodward DJ, McIntire DD, Smith WK, Kalaria RN, Mann DMA (1992) Disease-specific patterns of locus coeruleus cell loss. Ann Neurol 32: 667–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.German DC, Walker bS, Manaye K, Smith WK, Woodward DJ, North AJ (1988) The human locus coeruleus: computer reconstruction of cellular distribution. J Neurosci 8: 1776–1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giannini LAA, Xie SX, McMillan CT, Liang M, Williams A, Jester C, Rascovsky K, Wolk DA, Ash S, Lee EB, Trojanowski JQ, Grossman M, Irwin DJ (2019) Divergent patterns of TDP-43 and tau pathologies in primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 85: 630–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giannini LAA, Xie SX, Peterson C, Zhou C, Lee EB, Wolk DA, Grossman M, Trojanowski JQ, McMillan CT, Irwin DJ (2019) Empiric Methods to Account for Pre-analytical Variability in Digital Histopathology in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Front Neurosci 13: 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibb WR, Luthert PJ, Marsden CD (1989) Corticobasal degeneration. Brain 112 ( Pt 5): 1171–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibbons GS, Banks RA, Kim B, Changolkar L, Riddle DM, Leight SN, Irwin DJ, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY (2018) Detection of Alzheimer Disease (AD)-Specific Tau Pathology in AD and NonAD Tauopathies by Immunohistochemistry With Novel Conformation-Selective Tau Antibodies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 77: 216–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibbons GS, Kim S-J, Robinson JL, Changolkar L, Irwin DJ, Shaw LM, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ (2019) Detection of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) specific tau pathology with conformation-selective anti-tau monoclonal antibody in co-morbid frontotemporal lobar degeneration-tau (FTLD-tau). Acta Neuropathol Commun 7: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, Ogar JM, Rohrer JD, Black S, Boeve BF, Manes F, Dronkers N, Vandenberghe R, Rascovsky K, Patterson K, Miller B, Knopman D, Hodges J, Mesulam M, Grossman M (2011) Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 76: 1006–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grudzien A, Shaw P, Weintraub S, Bigio E, Mash DC, Mesulam MM (2007) Locus coeruleus neurofibrillary degeneration in aging, mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 28: 327–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haglund M, Friberg N, Danielsson EJD, Norrman J, Englund E (2016) A methodological study of locus coeruleus degeneration in dementing disorders. Clin Neuropathol 35: 287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haglund M, Sjöbeck M, Englund E (2006) Locus ceruleus degeneration is ubiquitous in Alzheimer’s disease: Possible implications for diagnosis and treatment. Neuropathology 26: 528–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirsch E, Graybiel AM, Agid YA (1988) Melanized dopaminergic neurons are differentially susceptible to degeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Nature 334: 345–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Höglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M, Kurz C, Josephs KA, Lang AE, Mollenhauer B, Müller U, Nilsson C, Whitwell JL, et al. (2017) Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: The movement disorder society criteria. Mov Disord 32: 853–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Carrillo MC, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, et al. (2012) National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 8: 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iba M, Guo JL, McBride JD, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY (2013) Synthetic tau fibrils mediate transmission of neurofibrillary tangles in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s-like tauopathy. J Neurosci 33: 1024–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iba M, McBride JD, Guo JL, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY (2015) Tau pathology spread in PS19 tau transgenic mice following locus coeruleus (LC) injections of synthetic tau fibrils is determined by the LC’s afferent and efferent connections. Acta Neuropathol 130: 349–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irwin DJ, Brettschneider J, McMillan CT, Cooper F, Olm C, Arnold SE, Van Deerlin VM, Seeley WW, Miller BL, Lee EB, et al. (2016) Deep clinical and neuropathological phenotyping of Pick disease. Ann Neurol 79: 272–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Irwin DJ, Byrne MD, McMillan CT, Cooper F, Arnold SE, Lee EB, Van Deerlin VM, Xie SX, Lee VMY, Grossman M, et al. (2016) Semi-Automated Digital Image Analysis of Pick’s Disease and TDP-43 Proteinopathy. J Histochem Cytochem 64: 54–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irwin DJ, Cairns NJ, Grossman M, McMillan CT, Lee EB, Van Deerlin VM, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ (2014) Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: defining phenotypic diversity through personalized medicine. Acta Neuropathol 129: 469–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, Xie SX, Rascovsky K, Van Deerlin VM, Coslett HB, Hamilton R, Aguirre GK, Lee EB, Lee VMY, et al. (2018) Asymmetry of post-mortem neuropathology in behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain 141: 288–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaalund SS, Passamonti L, Allinson KSJ, Murley AG, Robbins TW, Spillantini MG, Rowe JB (2020) Locus coeruleus pathology in progressive supranuclear palsy, and its relation to disease severity. Acta Neuropathol Commun 8: 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keren NI, Lozar CT, Harris KC, Morgan PS, Eckert MA (2009) In vivo mapping of the human locus coeruleus. NeuroImage 47: 1261–1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langston JW, Forno LS, Tetrud J, Reeves AG, Kaplan JA, Karluk D (1999) Evidence of active nerve cell degeneration in the substantia nigra of humans years after 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine exposure. Ann Neurol 46: 598–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]