Abstract

Following his inauguration in late 2013, President Rouhani aimed to boost quality and equity in the health care delivery system. To fulfill this aim, a set of interventions, called Health Transformation Plan (HTP), were implemented. So far, it has been a heated debate whether HTP breathes a spirit of a new reform. HTP has targeted long-standing historical deficits of the Iranian health system as well as urgent problems, both of which have been, to some extent, resolved. To decrease Out-Of-Pocket (OOP) health expenditures, HTP has presented new financing mechanisms to expand a safety net to Iranian citizens fundamentally. HTP also encompassed interventions to overcome problems in the provision of health care by recruitment of health workforces, establishing new health facilities, and expanding primary health care to urban and peri-urban areas. Furthermore, performance indicators including access, quality, and patient satisfaction have been affected. Given these changes, HTP is entitled to be a health system reform. However, a new agenda within HTP is required so that the Iranian health system can obtain better value for money that is to be spending on it.

Keywords: Health care reform, health system, health system strengthening, Universal health coverage

Introduction

Strengthening health systems has become a priority for countries over the past decade.[1,2] Iran has embarked on various initiatives to strengthen the health system to accomplish equitable accessible health care for Iranian citizens.[3,4] Neither of health reform initiatives have emerged during presidential campaigns, except President Rouhani's campaign. Following his inauguration in late 2013, he chose the Ministry of Health and Medical Education's (MOHME) plan for health and allocated more public funds into it. The plan was proposed for better subsidies' allocation to achieve universal health coverage.[5] This plan was essentially a set of instructions, Health Transformation Plan (HTP), to respond to critical challenges the health system had, including a high share of Out-Of-Pocket (OOP) expenditures, poor quality of care in public hospitals,[6,7] and insufficient provisioning of medicines.[8]

Following HTP implementation, it has been debated whether HTP could be entitled as a reform or if it was an urgent remedy for crises driven by increasingly uncontrolled household's health expenditures. There are different opinions on the essence of HTP. On the one hand, proponents advocate that it has contributed to paving the way toward transforming the country's health system. On the other hand, critics believe that while HTP has accomplished its objectives to some extent, it has failed to include a number of key interventions and to fundamentally transform the health system by touching upon key functions.

In this manuscript, we describe how historical deficits in the Iranian health system, accompanied by political change, have led to a course of events that opened a window to design and implement HTP. We also examined the interventions of HTP as well as its short-term achievements and analyzed how HTP has brought up changes in the functions of the health system to improve health system performance's goals. To do this, a qualitative documentary analysis was conducted. Key documents related to HTP were identified, validated, and reviewed. Kingdon's Multiple Streams framework[9] and the Control Knobs framework[10] were selected to explain how HTP came onto the policy agenda and to evaluate changes made by HTP, respectively. To data analysis, the latent content analysis was employed.[11]

Historical Challenges of the Iranian Health System

The Iranian health system has suffered from caveats that have undermined the performance of the health system.[12,13] The stewardship role of MOHME remains weak in terms of regulating providers' behaviors and oversight on the entire health system.[14] For instance, the private sector was one of the main health care providers, which provided around 80% of outpatient care and 20% of inpatient care. However, this sector was largely unregulated.[15] The dual practice of medical professionals was a common phenomenon.[16]

Concerning financing, the health system suffered from a lack of sustainable financial resources. In general, individual contributions to health care costs were regressive and unfair[17] (18.5% did not have any health insurance coverage).[18] Furthermore, the share of General Government Health Expenditure (GGHE) was low [around 33.3%–39.1% of total health expenditure (THE)] and OOP was high (more than 50% of THE, even 58.2% in 2010).[19] The phenomenon of provider-induced demand was highly prevalent. It showed that the health market was mainly run by OOP payments and driven by providers.[20] It was also estimated that the share of informal payments for health care was around 15% of THE.[13,21,22] Risk pooling was also fragmented by having several insurance funds in place.[17,23] Despite the fact that a standard health insurance policy has been agreed upon,[24] health insurance funds have been offering health insurance schemes with varying benefit packages.[23] The benefit package was not defined by setting priorities for needs, a cost-effective analysis,[17] or even acknowledging the Gross Domestic Production (GDP) per capita. The contribution calculation methods used (the payroll tax and the fixed premium) were mainly regressive[17] and could not fully cover the costs of this wide benefit package. As a result, the Health Insurances Organizations could not reimburse providers on time, especially hospitals which had long-term delay for their payments. The inability for on-time reimbursement motivated providers to ask for informal payments, and to induce patients to demand more health care services. Moreover, payment to health care providers is based on known inefficient retrospective methods (e.g., fee-for-service).[25]

In regards to the organization of care, there had been no consensus on good-practice health care delivery models for peri-urban and urban areas.[26] Despite a long-time emphasis on gatekeeping and the referral system, care coordination between providers within and between levels was lacking.[27,28] Health care resources have been either in short supply or have been unequally distributed between health needs and geographical regions.[29,30] Moreover, decisions on the use of medicine and health technologies have rarely been taken based on Health Technology Assessment.[31,32,33] Standard practice guidelines have not been completely developed or in the case of development,[34] they were not implemented, resulting in huge clinical and economic consequences.

These deficiencies of the health system were further exacerbated by epidemiologic transitions from communicable diseases to chronic and lifestyle-based diseases, rises in medical expenditures and patient expectations. About 80% of the burden of disease belongs to chronic diseases and long-term conditions.[35,36]

In the two years leading up to 2013, the country's economic circumstances were dramatically changed, due to international sanctions imposed on the finance and oil industry and some of the managerial issues as well. Consequently, the government's incomes significantly dropped[37,38] and the cabinet decided to allocate limited existed resources to its high priorities sectors. Unfortunately, health was not in priorities[39] which in turn led to inadequate resources allocated to the health sector [Table 1].

Table 1.

Health financing indicators of I.R. Iran

| Year | Total health expenditure % GDP | THE per capita (PPP) | GGHE per capita (PPP) | OOP per capita (PPP) | Public expenditure on health % THE | Private expenditure on health %THE | Share of OOP from THE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 7.1 | 1233 | 416 | 717 | 33.7 | 66.3 | 58.2 |

| 2011 | 6.8 | 1233 | 433 | 691 | 35.1 | 64.9 | 56.0 |

| 2012 | 6.5 | 1245 | 382 | 627 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 54.8 |

Under this circumstance, no comprehensive scheme has been in place to protect people against rising costs of care; consequently, patients should be able to incur most costs in health care. High share of OOP has been historically present in the country; however, in years close to HTP, OOP share has reached on 58.2%, 56.0%, and 54.8% in 2010, 2011, and 2012, respectively [Table 1].[19,40] The high share of OOP from household incomes had led to a rise in the percentage of catastrophic expenditure. The percentage of population affected by this catastrophic expenditure had been stable above 2% over years prior to HTP and with 2.5% at its highest in 2013.[19,41] In addition, most people had to pay more for their own essential needs (e.g., food, housing, etc.) instead of health needs,[42] resulting in less utilization of health services.[43] At the same time, the share of GGHE decreased.[19,40] These all led to a significant decrease in THE per capita and the share of THE as GDP [Table 1], while accompanied by the health care inflation rate increase,[44] that intensified the underutilization of health services.

Moreover, there was a steep rise in prices for medical services, medicine, and medical devices at a consumption level. The currency crisis has also led to the loss of monetary value that reduced households' availability to purchase goods and services, especially expensive medicine and medical devices.[45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] In 2012, the share of medicine from household health expenditure had an increase by 50% and reached around 29%, the ever-highest share throughout the last two decades.[42]

The economy, weakened by sanctions, had not only led the country to inadequate health resources but also caused insufficient and interrupted imports of medicine and medical devices. Consequently, some patients (such as people with hemophilia or different types of cancers) had difficulty with on-time access to their specific medicine.[53] These events had led to public discontent with the health system and a heated debate on the responsibility of the state to protect citizens.[54]

A window of opportunity

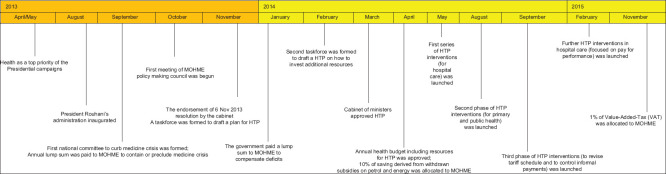

Besides the commitment that was provided by the new government, there was support from the Supreme leader launching the General Health Policies (GHPs), in which strategic directions were taken for the health system.[55] Moreover, the parliament strongly supported those health issues and enacted required laws for them. Following the announcement of the president's priorities, MOHME took immediate action to tackle the most urgent issues discussed above. The first national committee was formed to curb the medicine crisis in September 2013 [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Chronological order of Health System Transformation Plan development

After recovering the pharmaceutical market, in November 2013, the cabinet of ministers decided to form a taskforce to draft a transformation plan for the health sector and coordinate all governmental organizations to fulfill this plan. After about 6 months of provisioning, HTP for diagnostic and therapeutic services was initiated in May 2014, and, in August 2014, HTP was officially initiated for primary and public health.

Funding sources, interventions, and short-term achievements of HTP

HTP was a set of comprehensive interventions supported by new funding resources (3 billion USD was allocated for HTP implementation only in the first year) [Panel 1]. Main interventions included programs to increase the sustainability of health financing to expand health insurance coverage, increase protection against financial risk and to improve access and quality of health care [Table 2]. Supplementary 1 provides more details about interventions.

Panel 1.

Items of health budget’s growth

| The government paid a lump sum to MOHME to fill in the gap of local and foreign currency in order to contain or preclude crisis arising from the shortage of medicine in 2013 (550 USD million) and subsequent years; |

| The government paid a lump sum to MOHME to compensate budget deficits in 2013 (715 USD million); |

| MOHME’s annual budget was grown by 37.8% in 2014; |

| Iranian Health Insurance Organization (IHIO) had budget growth as much as 66% in 2014; |

| IHIO by law was entitled to increase the premium to from 5% of total income to 6%; |

| 1% of Value-Added-Tax (VAT) and 10% of saving originated from the public subsidy program was allocated to MOHME in 2014. The former has remained intact so far, but the later was not completely allocated after 2014. |

Table 2.

HTP’s aims, interventions, and short-term achievements

| Aim | Interventions | Mechanism¥ | Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increase the sustainability of health financing | Introduce new sustained funding sources, i.e., 1% value-added tax, 10% of saving originated from public subsidy program and increase current funding sources, i.e., public budget for the health sector | F | GGHE as a percent of THE increased from 33·3% in 2012 to 51·3% in 2015[19,40] |

| GDP per capita spent on the health sector increased from 6·5% in 2012 to around 8.1% in 2015[19,40] | |||

| Expand health insurance coverage | Expand health insurance coverage to the population with no basic health insurance | F | Number of people with health insurance increased from 83·3%[18]to 93.1% in 2015[56] |

| Increase financial risk protection | Reduce copayments for both inpatient and outpatient care in the public sector | F | OOP rate decreased from 54·8% in 2012 to 38·1% in 2015[19,40] |

| Reimbursement programs to bear costs of special conditions, high cost, and incurable diseases, e.g., cancers, multiple sclerosis, organ transplantation | F | Percentage of the population affected by catastrophic expenditures remained unchanged, ranging from 2.5%-2.4% during 2013-2015[19] | |

| Control and eliminate informal payments through revising tariff schedule with the participation of Iranian Medical | P, B, R | ||

| Council and professional associations and establishing a new legal mechanism to deal with offenders | The informal payments for inpatient services decreased, particularly in the public sector[57] | ||

| Control the price of medicines and medical equipment (capital and consumable) | R | ||

| Improve access and quality | Change the payment mechanisms and pay for performance mechanism | P | Hospital density (per 10000 people) increased from 13·4 in 2013 to 15·7 in 2015[58] |

| Increase the number of health workforce by filling in unoccupied medical professional positions or making changes in the contracts in public health care settings | O | There is one health workforce per 118 people †[58] | |

| Establish new public clinics, hospital beds, and primary health care settings | O | ||

| Introduce/develop new and revise the current primary health care programs | O | ||

| Empower the health workforces | O | List of readily available medicine in public hospitals’ drug store increased from around 340 in 2013 to around 750 in 2015 and from around 350 in 2013 to 450 in 2015 in primary health care facilities[58] | |

| Improve the use of health information technology (IT) through scaling up the national IT health systems | O | 77% of patients were satisfied with inpatient services in public hospitals †[59] | |

| Improve the quality of amenities, e.g., buildings, beds, decoration in public hospital and health facilities | O | 78% of inpatient service users and 74% of outpatient service users were satisfied with these services †[59] | |

| Improve environmental and occupational health | O | ||

| Resolve the shortage of medicines and consumable medical devices/supplies | O | ||

| Support the local production of medicines | R, B | ||

| Improve community participation in health promotion | R, B | ||

| Promote natural delivery | B |

¥Mechanism refers to the health system’s control knobs that create desired effects. F: Financing, P: Payment, B: Behavior, R: Regulation, O: Organization; †Data for the base year is not available or validated

Discussion

HTP has presented a set of problem-based interventions that could tackle some of the problems of the health system. In this regard, the extent of reduction in the number of uninsured individuals, copayments, and OOP is highly remarkable.[41,60] Furthermore, HTP could operate the control knobs of health systems and create improvements in key performance indicators, as expected from a reform.[10,61]

The main interventions in the finance systems, i.e., the health sector's share from VAT and cut costs on subsidies from the health sector's share, will remain intact in future administrations as those have been passed into law in the Iranian parliament.[62] However, health care financing still suffers from inefficient risk pooling arrangements, a factor that has a vital role in fair and sustainable resource mobilization and allocation.[63]

Interventions in payments systems within HTP (e.g., new tariff schedule, further supervision to health care provider's behavior in close cooperation with formal supervisory organizations and the public, and pay per performance) have reportedly reduced informal payment significantly. However, these interventions might be perceived as initial efforts to cut financial relationships between physicians and patients. Investigations on the long-term impacts of these interventions can only respond to such concerns. If the new tariff schedule has been formulated based on evidence and considering the technical issues involving all stakeholders,[64] then it might be entitled to a reform. All of these should not ignore the major caveat of payment methods; Iran needs to shift from the uncapped fee-for-service to more effective prospective payment methods.[65,66]

In regards to its organizing systems, HTP has designed a new organized structure for primary health care in peri-urban areas, where no organized primary care system has been in place during the last decades. It also has upgraded the structure of primary health care in urban areas. The health workforce recruitment, new buildings, renovated facilities, and modernized machineries across the country have improved access and quality of care. These interventions would last for at least several years, which in turn may result in improving access to services, and in long-term impact on the state of the population's health.[67,68] Furthermore, within HTP, noncommunicable disease programs with ongoing risk control factors were initiated. Altogether, these interventions on organizing health care might be considered as a reform, similar to those that were experienced by neighborhood countries.[69] However, there are still important areas in organizing health care that remain unchecked, such as the referral system, care integration, and health care provision for people that are disadvantaged.

Conclusions

HTP has been the main social plan of Rouhani's administration, which to some extent resolved urgent challenges such as the high rise of OOP. It has effectively touched upon several key functions of the health system, particularly financing the health sector. It carried other essential ingredients for health system reform and has made new arrangements that enabled the country not only to balance the health budget but also to provide risk protection for the entire population and to improve access, quality, equity, and satisfaction. Thus, what has been done under HTP can be considered as a health care reform, even though the significant impact of HTP was increasing the financial resources for the health sector.

It is also worth noting that HTP was started while the country was suffering from a critical economic situation. It was not only able to tackle the urgent challenges of the health system but also was able to some extent meet its main goals. Thus, it is not to be expected for HTP to be fully implemented from beginning to end in four years. As shown by other countries' experiences, making reforms to UHC takes a long time.[70] Therefore, Iran should embark on a new agenda within HTP to make the health sector more efficient as to ultimately convince the government and the public that the highest cost is worth the value.

Last but not the least, since the health system is entirely affected by contextual (e.g., economic, social, political situation of the country) and global (e.g., pandemic or armed conflicts) circumstances, making the health system more resilient is crucial. Otherwise, other dramatic changes (like further sanctions or economic shocks) can ruin all efforts done under HTP to improve the health system performance.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

IH is the Acting Minister. MH, AS, and RD were deputies of the minister in the 11th government of the IR Iran. HSS was the academic staff of Iran's National Institute for Health Research until December 2019. MM, EA, and AO are the academic staff of Iran's National Institute for Health Research, where RM was its head until May 2018.

References

- 1.Kutzin J, Sparkes SP. Health systems strengthening, universal health coverage, health security and resilience. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94:2. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.165050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamara H, Jeremy S. The emergence of global attention to health systems strengthening. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28:41–50. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sajadi HS, Majdzadeh R. From primary health care to universal health coverage in the Islamic Republic of Iran: A journey of four decades. Arch Iran Med. 2019;22:262–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heshmati B, Joulaei H. Iran's health-care system in transition. Lancet. 2016;387:29–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mousavi SM, Sadeghifar J. Universal health coverage in Iran. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e305–6. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)00068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moradi-Lakeh M, Vosoogh-Moghaddam A. Health sector evolution plan in Iran; equity and sustainability concerns. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4:637–40. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajizadeh M, Nghiem HS. Out-of-pocket expenditures for hospital care in Iran: Who is at risk of incurring catastrophic payments? Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2011;11:267–85. doi: 10.1007/s10754-011-9099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Namazi S. Sanctions and medical supply shortages in Iran. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 31]. Available from: http://gozaresh-nakhandeir/ref/3/27/sanctions_medical_supply_shortages_in_iranpdf .

- 9.Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies. 2nd ed. New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts M, Hsiao W, Berman P, Reich M. Getting Health Reform Right: A Guide to Improving Performance and Equity. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nurs Plus Open. 2016;2:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lankarani KB, Alavian SM, Peymani P. Health in the Islamic Republic of Iran, challenges and progresses. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2013;27:42–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vosoogh Moghaddam A, Damari B, Alikhani S, Salarianzedeh M, Rostamigooran N, Delavari A, et al. Health in the 5th 5-years development plan of Iran: Main challenges, general policies and strategies. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42:42–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damari B, Vosoogh-Moghaddam A, Delavari A. How does the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran protect the public benefits.Analysis of stewardship function and the way forward? Hakim Health Sys Res. 2015;18:94–104. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajabi F, Esmailzadeh H, Rostamigooran N, Majdzadeh R, Doshmangir L. Future of health care delivery in Iran, opportunities and threats. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(Suppl 1):23–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bazyar M, Rashidian A, Jahanmehr N, Behzadi F, Moghri J, Doshmangir L. Prohibiting physicians' dual practice in Iran: Policy options for implementation. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33:e711–20. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibrahimipour H, Maleki MR, Brown R, Gohari M, Karimi I, Dehnavieh R. A qualitative study of the difficulties in reaching sustainable universal health insurance coverage in Iran. Health Policy Plann. 2011;26:485–95. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rashidian A, Khosravi A, Khabiri R, Khodayari-Moez E, Elahi E, Arab M, et al. Islamic Republic of Iran's Multiple Indicator Demograpphic and Healh Survey (IrMIDHS) 2010. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 31]. Available from: http://nihr.tums.ac.ir/UpFiles/Documents/d057 8878-.a152-.4245-.acd1-.ea32f0a3f3b9.pdf .

- 20.Davari M, Haycox A, Walley T. Health care financing in iran; is privatization a good solution? Iran J Public Health. 2012;41:14–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nekoeimoghadam M, Esfandiari A, Ramezani F, Amiresmaili M. Informal payments in health care: A case study of Kerman province in Iran. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2013;1:157–62. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2013.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsa M, Aramesh K, Nedjat S, Kandi MJ, Larijani B. Informal payments for health care in Iran: Results of a qualitative study. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:79–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bazyar M, Rashidian A, Kane S, Mahdavi MR, Sari AA, Doshmangir L. Policy options to reduce fragmentation in the pooling of health insurance funds in Iran. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5:253–8. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 31]. Available from: https://meybod.ac.ir/userfiles/financial/files/financial_4.pdf .

- 25.Bastani P, Doshmangir L, Samadbeik M, Dinarvand R. Requirements and incentives for implementation of pharmaceutical strategic purchasing in Iranian health system: A qualitative study. Glob J Health Sci. 2016;9:163–70. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takian A, Rashidian A, Kabir MJ. Expediency and coincidence in re-engineering a health system: An interpretive approach to formation of family medicine in Iran. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26:163–73. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majdzadeh R. Family physician implementation and preventive medicine; opportunities and challenges. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:665–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moghadam MN, Sadeghi V, Parva S. Weaknesses and challenges of primary health care system in Iran: A review. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2012;27:e121–31. doi: 10.1002/hpm.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akbari Sari A, Rezaei S, Rad EH, Dehghanian N, Chavehpour Y. Regional disparity in physical resources in the health sector in Iran: A comparison of two time periods. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:848–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sefiddashti SE, Arab M, Ghazanfari S, Kazemi Z, Rezaei S, Karyani AK. Trends of geographic inequalities in the distribution of human resources in health care system: The case of Iran. Electron Physician. 2016;8:2607–13. doi: 10.19082/2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davari M, Haycox A, Walley T. The Iranian health insurance system; past experiences, present challenges and future strategies. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41:1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palesh M, Fredrikson S, Jamshidi H, Jonsson PM, Tomson G. Diffusion of magnetic resonance imaging in Iran. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2007;23:278–85. doi: 10.1017/S0266462307070377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palesh M, Tishelman C, Fredrikson S, Jamshidi H, Tomson G, Emami A. “We noticed that suddenly the country has become full of MRI”.Policy makers' views on diffusion and use of health technologies in Iran. Health Res Policy Syst. 2010;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baradaran-Seyed Z, Nedjat S, Yazdizadeh B, Nedjat S, Majdzadeh R. Barriers of clinical practice guidelines development and implementation in developing countries: A case study in Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:340–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mokdad AH, Forouzanfar MH, Daoud F, El Bcheraoui C, Moradi-Lakeh M, Khalil I, et al. Health in times of uncertainty in the eastern Mediterranean region, 1990-2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e704–13. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 31]. Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-.compare/

- 37.Farzanegan MR, Khabbazan MM, Sadeghi H. Palgrave Macmillan: New York; 2016. Economic Welfare and Inequality in Iran; pp. 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katzman K. Iran sanctions. Curr Politics Econ Middle East. 2014;5:41. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sajadi HS, Hosseini M, Dehghani A, Khodayari R, Zandiyan H, Hosseini SS. The policy analysis of iran's health transformation plan in therapeutic services. Hakim Health Sys Res. 2018;21:71–88. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goudarzi Z, Mobinizadeh MR, Olyaeemanesh AR, Tabatabaei M, Maanavi S, Majdzadeh M. Health System Financing in Iran. In: Harirchi I, Majdzadeh M, Ahmadnezhad E, Abdi Z, editors. Observatory on Health System. Tehran: National Institute for Health Res; [Google Scholar]

- 41. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 31]. Available from: http://nihr.tums.ac.ir/UpFiles/Documents/4baaf 672-.84e4-.4551-.89ef-.10af46d2fe78.pdf .

- 42. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 31]. Available from: https://www.amar.org.ir/english/Statistics-.by-.Topic/Household-.Expenditure-.and-.Income .

- 43.Iranian Health Insurance Organization. The performance report of Iranian Health Insurance Organization in 2012. Tehran: Iranian Health Insurance Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 31]. Available from: https://www.amar.org.ir/english/Statistics-.by-.Topic/Household-.Expenditure-.and-.Income .

- 45.Gorji A. Sanctions against Iran: The impact on health services. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43:381–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karimi M, Haghpanah S. The effects of economic sanctions on disease specific clinical outcomes of patients with thalassemia and hemophilia in Iran. Health Policy. 2015;119:239–43. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohammadi D. US-led economic sanctions strangle Iran's drug supply. Lancet. 2013;381:279. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Setayesh S, Mackey TK. Addressing the impact of economic sanctions on Iranian drug shortages in the joint comprehensive plan of action: Promoting access to medicines and health diplomacy. Global Health. 2016;12:31. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0168-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shahabi S. International sanctions: Sanctions in Iran disrupt cancer care. Nature. 2015;520:157. doi: 10.1038/520157b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shahabi S, Fazlalizadeh H, Stedman J, Chuang L, Shariftabrizi A, Ram R. The impact of international economic sanctions on Iranian cancer health care. Health Policy. 2015;119:1309–18. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shariatirad S, Maarefvand M. Sanctions against Iran and the impact on drug use and addiction treatment. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24:636–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheraghali AM. Impacts of international sanctions on Iranian pharmaceutical market. DARU J Pharm Sci. 2013;21:64. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-21-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Danaei G, Harirchi I, Sajadi HS, Yahyaei F, Majdzadeh R. The harsh effects of sanctions on Iranian health. Lancet. 2019;394:468–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31763-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Emami Razavi SH. Health system reform plan in Iran: Approaching universal health coverage. Hakim Health Sys Res. 2016;18:329–35. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marandi SA. The health landscape of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Med J Islamic World Acad Sci. 2016;109:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 31]. Available from: http://nihr.tums.ac.ir/UpFiles/Documents/ecedcf50-.7101-.4627-.91d9-.004139d317aa.pdf .

- 57.Piroozi B, Rashidian A, Moradi G, Takian A, Ghasri H, Ghadimi T. Out-of-pocket and informal payment before and after the health transformation plan in Iran: Evidence from hospitals located in Kurdistan, Iran. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2017;6:573–86. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 31]. Available from: http://behdasht.gov.ir/uploads/amalkard.pdf .

- 59.Ahmadnezhad E, Abdi Z, Majdzadeh M. Assessment of Health System toward Universal Health Coverage. In: Harirchi I, Majdzadeh M, Ahmadnezhad E, Abdi Z, editors. Observatory on Health System. Tehran: National Institute for Health Research; 2017. pp. 149–61. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hsu J, Majdzadeh R, Harirchi I, Soucat A. Health system transformation in the Islamic Republic of Iran: An assessment of key health financing and governance issues. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Senkubuge F, Modisenyane M, Bishaw T. Strengthening health systems by health sector reforms. Global health action. 2014;7:23568. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Islamic Republic of Iran Parliament The sixth Economic, Social and Cultural Development Plan. Tehran: Jahade Daneshgahi; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thomson S, Foubister T, Figueras J, Kutzin J, Permanand G, Bryndová L Addressing Financial Sustainability in Health Systems Copenhagen. World Health Organization. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aryankhesal A, Meydari A, Naghdi S, Ghiasvand H, Baghri Y. Pitfalls of revising physicians' relative value units (RVUs) in Iran: A qualitative study on medical practitioners' perspective. Health Scope. 2018 (In Press) [Google Scholar]

- 65.Babashahy S, Baghbanian A, Manavi S, Akbari Sari A, Olyaee Manesh A, Ghaffari S, et al. Insight into provider payment mechanisms in health care industry: A case of Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2016;45:693–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sajadi HS, Ehsani-Chimeh E, Majdzadeh R. Universal health coverage in Iran: Where we stand and how we can move forward. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2019;33:46–51. doi: 10.34171/mjiri.33.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heydari MR, Kalateh Sadati A, Bagheri Lankarani K, Imanieh MH, Baghi H, Lolia MJ. The evaluation of urban community health centers in relation to family physician and primary health care in Southern Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46:1726–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Imanieh MH, Sadati AK, Moghadami M, Hemmati A. Introducing the urban community health center (UCHC) as a nascent local model: Will it be a linchpin in the health sector reform in Iran? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4:331–2. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Atun R, Aydın S, Chakraborty S, Sümer S, Aran M, Gürol I, et al. Universal health coverage in Turkey: Enhancement of equity. Lancet. 2013;382:65–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61051-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reich MR, Harris J, Ikegami N, Maeda A, Cashin C, Araujo EC, et al. Moving towards universal health coverage: Lessons from 11 country studies. Lancet. 2016;387:811–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]