Highlights

-

•

We have developed a rapid, accurate, and highly reproducible plaque reduction microneutralization (PRMNT) assay for SARS-CoV-2.

-

•

Our PRMNT assay allows to identify and characterize antibodies with neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2.

-

•

Likewise, our PRMNT assay can be used to find compounds with antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2.

-

•

The PRMNT assay can be developed using peroxidase or infrared staining readouts.

-

•

Our PRMNT assay can be adapted to HTS settings to interrogate complex library of SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Neutralization, Monoclonal antibodies, Polyclonal antibodies, Neutralizing antibodies, Antivirals, Plaque reduction microneutralization assay

Abstract

Towards the end of 2019, a novel coronavirus (CoV) named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), genetically similar to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), emerged in Wuhan, Hubei province of China, and has been responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in humans. Since its first report, SARS-CoV-2 has resulted in a global pandemic, with over 10 million human infections and over 560,000 deaths reported worldwide at the end of June 2020. Currently, there are no United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved vaccines and/or antivirals licensed against SARS-CoV-2. The high economical and health impacts of SARS-CoV-2 has placed global pressure on the scientific community to identify effective prophylactic and therapeutic treatments for SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated COVID-19 disease. While some compounds have been already reported to reduce SARS-CoV-2 infection and a handful of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been described that neutralize SARS-CoV-2, there is an urgent need for the development and standardization of assays which can be used in high through-put screening (HTS) settings to identify new antivirals and/or neutralizing mAbs against SARS-CoV-2. Here, we described a rapid, accurate, and highly reproducible plaque reduction microneutralization (PRMNT) assay that can be quickly adapted for the identification and characterization of both neutralizing mAbs and antivirals against SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, our MNA is compatible with HTS settings to interrogate large and/or complex libraries of mAbs and/or antivirals to identify those with neutralizing and/or antiviral activity, respectively, against SARS-CoV-2.

1. Introduction

A new variant of coronavirus (CoV) emerged around December of 2019 causing multiple hospitalizations in Wuhan, China (Bogoch et al., 2020; Choy et al., 2020). Ever since its first emergence, this novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been responsible for pneumonia leading to death among hospitalized patients all around the world. The transboundary spread of this coronavirus-associated acute respiratory disease, designated as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare the disease as a global pandemic on March 11th, 2020 (Organization). Besides the public health significance, COVID-19 has also disrupted the functioning of the global supply chain, bringing to a halt major economic activities all around the world.

SARS-CoV-2 is a close relative of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in the Coronaviridae family and has a single-stranded, non-segmented, positive-sense RNA genome (Schoeman and Fielding, 2019). Like other CoVs, SARS-CoV-2 encodes four conserved structural membrane (M), envelope (E), nucleoprotein (NP), and spike (S) proteins, all of which play an important role in viral replication (Masters, 2006; Mortola and Roy, 2004; Schoeman and Fielding, 2019; Wang et al., 2017). Of the four structural proteins, the S protein determines tissue tropism and host susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. An early aspect of SARS-CoV-2 replication in a susceptible host is the complex interaction between the viral S protein and the host cell surface receptor, the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). This intricate association enables viral fusion to the host cell membrane facilitating virus entry, an important requisite for successful virus replication. Owing to their importance in facilitating virus entry, the S protein has been a major target of neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) that are currently being produced against SARS-CoV-2.

Due to the high impact of COVID-19 and the lack of commercially available vaccines and/or NAbs, many United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved or repurposed drugs are currently being suggested for the treatment of clinically-infected COVID-19 patients (Elfiky, 2020; Park et al., 2020b; Xu et al., 2020). As scientist and clinicians race to identify drugs for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated COVID-19 disease, some have been used in clinical settings with no supporting evidence of antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 (Reihani et al., 2020). The majority of these compounds are being recommended based on their ability to target specific steps of the replication cycle of similar viruses or, as seen in some cases, based on their ability to inhibit protozoan parasites (Yao et al., 2020). Apart from the lack of effective antiviral or immunotherapeutic activity against SARS-CoV-2, administration of certain antiviral compounds in COVID-19 patients has been a subject of safety concern among many clinicians. For instance, at high doses, chloroquine is extremely toxic causing death as a result of cardiac arrhythmias (Juurlink, 2020; Riou et al., 1988), and in the current pandemic, cases of chloroquine poisoning have been reported in Nigeria due to the abuse of the drug for treating COVID-19 patients (Chary et al., 2020). As a result, there is an urgent need for assays that can be used to screen the increasing lists of potential antiviral compounds and/or NAbs for an effective and safe anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity. Herein, we described a rapid approach that can be easily adapted for evaluating the potency and safety of a wide array of antiviral compounds and/or NAbs against SARS-CoV-2 in an in vitro setting.

2. Materials

2.1. Supplies and reagents

-

1

Vero E6 cells (BEI Resources, catalog # NR-596).

-

2

SARS-CoV-2 isolate USA-WA1/2020 (BEI Resources, catalog # NR-52,281).

-

3

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium, DMEM (Corning, catalog # 15−013-CV).

-

4

Penicillin-Streptomycin l-glutamine 100x, PSG (Corning, catalog # 30−009-CI).

-

5

Fetal bovine serum, FBS (Avantor Seradigm, catalog # 1500−500).

-

6

Agar, 2% (Oxoid, catalog # LP0028).

-

7

Bovine serum albumin, 35 % (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich, catalog # A7409).

-

8

BSA, 2.5 % (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog # A9647).

-

9

DMEM/F-12 powder (Gibco, catalog # 12400−024).

-

10

Cell culture grade water (Corning, catalog # 25−055-CV).

-

11

Sodium bicarbonate, 5% (Sigma, catalog # S-5761).

-

12

DEAE-Dextran, 1% (MP Biomedicals, catalog # 195,133).

-

13

Crystal violet, 1% (Fisher Scientific, catalog # C581−100).

-

14

Avicel PH-101, 1% (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog # 11,365).

-

15

Formalin solution, neutral buffered, 10 % (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog # HT501128−4 L).

-

16

Triton X-100, 0.5 % (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog # X100−500ML).

-

17

Mouse anti-SARS-1 nucleoprotein (NP) mAb 1C7 generated at the Center for Therapeutic Antibody Development at The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (ISMMS) (Millipore Sigma, catalog # ZMS1075).

-

18

Remdesivir (AOBIOUS, catalog # AOB36496).

-

19

Human monoclonal antibody (hmAb) 1207B4 produced in house.

-

20

VECTASTAIN® ABC-HRP Kit, Peroxidase (POD) (Mouse IgG) (Vector Laboratory, catalog # P-4002).

-

21

DAB Substrate Kit, POD (HRP), with Nickel (Vector Laboratory, catalog # SK-4100).

-

22

IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (LI−COR, catalog # 926–32210).

-

23

DRAQ5™ Fluorescent Probe Solution 5 mM (Thermo scientific, catalog # 62,251).

-

24

6-well cell culture plate (Greiner Bio-One, catalog # 657,160).

-

25

96-well cell culture plate (Greiner Bio-One, catalog # 655,180).

-

26

Polystyrene tissue culture flask (Corning, catalog # 431,081).

-

27

Polypropylene sterile conical tube, 15 mL (Greiner Bio-One, catalog # 188,261).

-

28

Polypropylene sterile conical tube, 50 mL (Greiner Bio-One, catalog # 227,270).

-

29

Serological pipette, 5 mL (Greiner Bio-One, catalog # 606 180).

-

30

Serological pipette,10 mL (Greiner Bio-One, catalog # 607 180).

-

31

Serological pipette, 25 mL (Greiner Bio-One, catalog # 760 180).

-

32

Universal pipette tip, 20 μL (VWR, catalog # 76322−134).

-

33

Universal pipette tip, 200 μL (VWR, catalog # 76322−150).

-

34

Universal pipette tip, 1000 μL (VWR, catalog # 16466−008).

-

35

Microcentrifuge tube, 1.5 mL (VWR, catalog # 89000−028).

-

36

Sterile basin (VWR, catalog # 89094−680).

-

37

CO2 incubator (PHCbi, model # MCO-170AICUVDL).

-

38

CTL ImmunoSpot plate reader and counting software (Cellular Technology Limited).

-

39

Odyssey Sa Infrared Imaging System (LI−COR, model # 9260).

-

40

GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., version 8.0).

2.2. Media type and recipes

-

41

Cell-maintenance media (DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1% PSG).

-

42

Post-infection media (DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS and 1% PSG).

-

43

Infection media (DMEM supplemented with 1% PSG).

-

44

DMEM/F-12/Agar mixture (DMEM-F12 with 1% DEAE-Dextran, 2% agar, and 5% NaHCO3).

-

45

Plaque reduction microneutralization (PRMNT) media (Post-infection media with 1% Avicel).

2.3. Biosafety recommendations

Although SARS-CoV-2 has been temporarily classified as a category B pathogen, biosafety caution applicable to the category A pathogens are strongly recommended when handling this pathogen. Manipulation of SARS-CoV-2 should only be carried out in a biosafety level 3 (BSL3) facility with an appropriate engineering system designed to produce negative air pressure and enhance the safety of laboratory workers. All individuals working with SARS-CoV-2 must have undergone proper biosafety training to work at BSL3 laboratories and be cleared proficient to carry out procedures requiring working with the virus. Cell culture procedures are carried out in BSL2 and moved to BSL3 when ready for viral infection.

2.4. Cells

Vero E6 cells, which have been demonstrated to be permissive to SARS-CoV-2, is the preferred cell type for the assays described in this protocol (Imai et al., 2020). Other cell types such as Vero E6 transfected to express transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2), a serine protease which activates SARS-CoV-2 infection (Matsuyama et al., 2020), can also be used. An important consideration when choosing a cell line for this assay is the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to efficiently infect and replicate in the cell line. It is important to seed cells a day before the assay to achieve approximately ∼85−95% confluency. Vero E6 cells are maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1% PSG. We recommend using fresh Vero E6 cells, between passage 1–10 as we have found that these cells grow better, and are more viable at low passage. It is equally important to make sure the cells are free from any contaminants including mycoplasma.

2.5. Virus

For the experiments described in this manuscript we used the SARS-CoV-2 isolate USA-WA1/2020 available from BEI Resources. For the proposed experiments, we recommend using ∼100−200 plaque forming units (PFU)/well for a 96-well plate. Higher concentrations of the virus may affect the sensitivity of the assay while using lower viral concentrations may result in reduced number of plaques/well. Following the experimental conditions described in this manuscript, you would expect to have ∼100−200 positive staining cells/well at 24 h p.i.

2.6. Serum or plasma samples

It is important to heat-inactivate serum or plasma samples from COVID-19 patients or SARS-CoV-2-infected animals at 56 °C for 1 h before performing the PRMNT assay. While we have not conducted side-by-side experiments to compare serum and plasma from same individuals to assess potential differences in the results in our assays, we recommend to heat inactivate the samples to destroy potential components that could cause stress to the cells, especially with plasma samples. Heat-inactivation is also important to destroy complement proteins or residual SARS-CoV-2 particles that may be present in serum/plasma samples. The experimental procedures to inactivate the virus should be confirmed and approved by each institutional biosafety committee (IBC). It has been reported that complement deposition on virus envelope may lead to infection-enhancement which may mask the neutralizing effects of Abs contained in serum or plasma samples (Montefiori, 1997). For serum samples or plasma samples, we recommend starting with a 1:100 dilution to avoid potential impurities that may affect the sensitivity of the assay. In the case of mAbs, we recommend starting with 10 μg. However, this will depend on the neutralizing capability of the mAb. We used a hmAb, 1207B4, for the purposes of this study.

2.7. Drugs

The drug used in this study is remdesivir, a nucleoside analog which interferes with the replication of viral genome by inhibiting viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) (Gordon et al., 2020). Any other antiviral drug or compound with potential antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 can equally be used in the assays described below.

2.8. Controls

It is important to design the described PRMNT assays by including proper positive and negative controls. A mAb with a known neutralizing titer or serum and/or plasma samples from convalescent SARS-CoV-2 patients that contains known NAbs can be used as positive controls. In the case of the antiviral drugs, we recommend to use remdesivir since it has been shown to have antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 (Choy et al., 2020; Ferner and Aronson, 2020). We recommend the use of serum/plasma sample from a normal healthy donor as a negative control. An additional recommended control to validate the immunostaining with the NP 1C7 mAb is to include cells without viral infection.

2.9. General procedure

All cell cultures procedures and antibody/antiviral dilutions are generally performed in the BSL2 before transfer to the BSL3 facility on the day of virus infection. For PRMNT assay, the amount of virus per well can be optimized based on the virus titer in the stock. Be careful not to touch the cells in the 96-well plate with pipette tips at all times during the experiment and assay development. During the inactivation procedure, it is important to ensure that the entire plate and its lid are fully submerged in 10 % formalin solution for proper inactivation. After the inactivation procedure, plates can be transferred from BSL3 to the BSL2 for immunostaining and development.

3. Methods

3.1. Preparation of SARS-CoV-2 stock

-

1

A day before viral infection, seed Vero E6 cells in a T-225 cell culture flask in cell-maintenance media to attain ∼85 %-95 % confluency (∼2.6 × 107-2.9 × 107 cells) on the day of infection and place them in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

-

2

Thaw the stock virus and prepare an infection media containing the virus inoculum at a MOI of 0.001.

-

3

Remove cell maintenance media and replace with infection media containing the virus in a total volume of 10 mL. Place the tissue culture flasks of infected cells in Ziploc bags and transport them on a flat tray to the humidified incubator and incubate at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. Note: Shake the flasks, gently, every 10 min to prevent cells from drying out during a 1 h incubation time-point (TP).

-

4

After 1 h of virus adsorption, in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2, remove the virus inoculum and replace with ∼40 mL of post-infection media.

-

5

Incubate for 72 h in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Note: SARS-CoV-2 behaves differently compared to most other viruses in that the presence of cytopathic effect (CPE) does not correlate with increased virus titer. For our virus stock, we carried out a multistep growth kinetics to determine the best time with the highest virus yield. In our hands, this correlated nicely with low CPE at ∼72 h of incubation.

-

6

Freeze-thaw the flask containing the tissue culture supernatant (TCS) once, followed by centrifugation at 2000 g for 10 min at 4 °C.

-

7

Aliquot the TCS in 500 μL volumes, and store at - 80 °C until further use.

3.2. Determining the infectious virus titer by plaque assay

-

1

The day before infection, prepare Vero E6 cells (6-well plate format,1 × 106 cells /well, duplicate) in cell-maintenance media and place them in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

-

2

Prepare 10-fold serial dilutions of the SARS-CoV-2 stock in infection media. Briefly, pipette 450 μL of infection media and add 50 μL of the virus stock in the first tube. Transfer 50 μL from tube #1 (10−1 dilution) to tube #2 (10-2 dilution) and continue doing serial dilutions. Note: It is important to change the tips between viral dilutions to prevent the transfer of virus particles from a lower to higher diluted infection medium.

-

3

After the removal of maintenance media from Vero E6 culture wells, infect cells with 200 μL of each of the SARS-CoV-2 dilution. Place the plates of infected cells in a Ziploc bag and transport them on a flat tray to the humidified incubator and incubate for 1 h at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2.

-

4

To prevent cells from drying and to also facilitate virus adsorption, shake the plates gently every 10 min.

-

5

After 1 h of viral adsorption, remove the virus inoculum and overlay the cells with DMEM/F-12/Agar mixture. Note: Ensure that at the start of the infection, the 2% agar is melted in a microwave and the temperature brought down to approximately 42 °C when mixing with warm DMEM/F-12. Note: It is important to keep the agar cool enough not to burn the cells, and at the same time warm enough not to solidify in the process of pipetting.

-

6

Allow the agar to solidify and invert the plates to prevent the accumulation of moisture during incubation.

-

7

Incubate the cells for 72 h in a humidified incubator at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2.

-

8

At 72 h post-infection (h p.i.), fix infected cells in 10 % formalin solution for 24 h. Note: After 24 h fixation with 10 % formalin solution, plates can be moved from the BSL3 to the BSL2 to complete the viral titration.

-

9

Perform immunostaining using the cross-reactive SARS-CoV NP mAb 1C7, at a working concentration of 1 μg/mL. The procedure for performing immunostaining is presented in detail later in this paper. Note: Alternatively, cells can also be stained with 1% crystal violet for plaque visualization. Count the number of plaques, and calculate the virus titer in plaque forming units per mL (PFU/mL).

3.3. A plaque reduction microneutralization (PRMNT) assay to identify Abs with neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2

This assay can be used to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing activity by mAbs, polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) or by an Ab-containing sample such as serum plasma from mammalian host species. Since serial dilutions of the Ab containing samples are used, the PRMNT assay measures the neutralizing activity of Abs in a concentration dependent manner. The ability of a NAbs to inhibit virus infection is manifested in the reduced capacity of the virus to produce visible plaques when compared to virus-only infected control cells. The PRMNT assay is similar to a plaque reduction neutralization (PRNT) assay with the only difference that the PRMNT utilizes 96-well plates. Although in this manuscript we describe the use of PRMNT in 96-well plates, similar experimental approaches can be miniaturized and conducted in 384-well cell culture plates for HTS purposes.

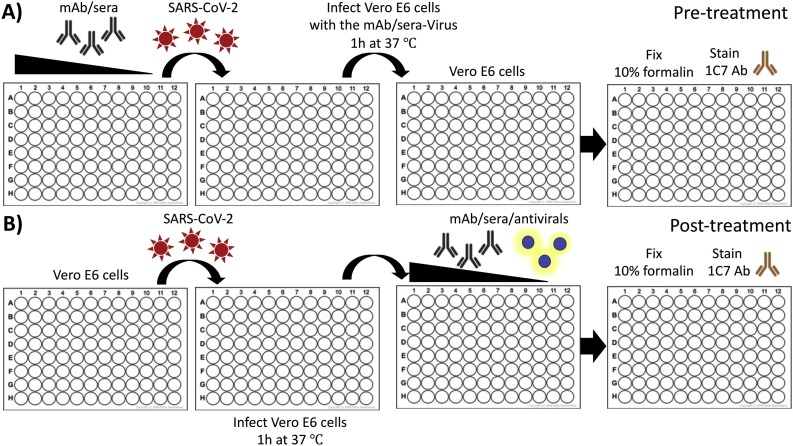

The process of entry into a susceptible host cell is an important determinant of infectivity and pathogenesis of viruses, including CoVs (Li, 2016; Perlman and Netland, 2009). SARS-CoV-2 relies on the ability of its S glycoprotein to bind to the ACE2 receptor through its receptor-binding domain (RBD) driving a conformational change that culminates in the fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane, facilitating cell entry (Shang et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 S is made up of 2 subunits, S1 and S2. During pre-treatment (Fig. 1 A), mAbs, or Ab containing samples, are pre-incubated with SARS-CoV-2 at 37 °C for 1 h. This enables the Abs to bind to the S protein blocking virus attachment, and subsequently interfering with the process of virus entry. While some SARS-CoV-2-induced NAbs can preferentially bind to either the S1 or S2 subunit of the S protein, others can bind, with a high affinity, to the RBD located within the S1 subunit (Wang et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). After 1 h of incubation, the Ab-virus mixture is then transferred to a confluent monolayer of Vero E6 cells and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. During this period, the unbound virus particles are able to attach to cells and initiate virus replication which can be determined by staining for SARS-CoV-2. In the post-treatment condition (Fig. 1B), virus adsorption is allowed to progress for 1 h at 37 °C prior to the addition of Abs. This gives an opportunity for the virus to initiate viral entry by binding to the cell surface receptor. NAb incubated with the infected cells may interfere with active viral replication partly by blocking later steps of the virus entry into the cell or by inhibiting the cell-to-cell spread of virus progeny. In both pre- and post-treatment conditions, the extent of virus neutralization can be visualized upon staining with a cross-reactive anti-SARS-CoV NP mAb (1C7), and the neutralization titer 50 (NT50) is calculated using a sigmoidal dose-response curve. The NT50 of an Ab is the dilution which inhibited viral replication in 50 % of the infected cells. While the pre-treatment PRMNT assay can be described, to some extent, as a prophylactic assessment of a NAb, the post-treatment PRMNT assay offers a therapeutic evaluation of the neutralizing activity of Abs against SARS-CoV-2. In addition, while the pre-treatment PRMNT assay focuses on identifying NAbs targeting the SARS-CoV-2 S RBD, the post-treatment PRMNT assay also allow the identification of Abs targeting other regions on the viral S glycoprotein involved in the fusion event (e.g. S2), or Abs affecting other steps in the replication cycle of the virus (e.g. virus assembly and/or budding). In general, a potent SARS-CoV-2 NAb will show a low NT50 titer while a weak NAb will give a high NT50 value. This protocol precludes the necessity for a cytotoxicity assay since Abs are not known to produce cytotoxic effects in cell cultures. However, a potential toxic effect of the NAbs can be determined when developing the assay with the infrared staining described later in this paper.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the PRMNT assay to identify SARS-CoV-2 NAbs: Confluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells are infected with SARS-CoV-2 (∼100-200 PFU/well) that are either co-incubated (A) or not (B) with NAbs/antivirals-containing samples. After 1 h adsorption of the virus, infected cells are incubated with post-infection media containing 1% Avicel alone (A) or with serially diluted NAbs/antivirals-containing samples (B). At 24 h p.i., cells are then fixed with 10 % formalin solution and immunostained with a SARS-CoV cross-reactive NP mAb.

3.3.1. Pre-treatment PRMNT assay

-

1

Seed ∼1 × 104 Vero E6 cells/well the day before virus infection in 96-well plates using cell maintenance media.

-

2

On the day of infection, check the confluency of the Vero E6 cells under a light microscope. The optimal cell confluency should be ∼85–95 %.

-

3

Prepare a 2-fold serial dilution of the Ab (or Ab containing sample) in an empty, sterile 96-well plate using infection media. Briefly, add 50 μL of infection media to columns 2–12, and add 100 μL of the desired starting concentration of each Ab, or Ab containing sample, to column 1. Transfer 50 μL of Ab from column 1 to column 2, and mix ∼10 times using a multi-channel pipette. Repeat this process from column 2 to column 10, changing the tips between dilutions to prevent transfer of residual Ab. Discard 50 μL from the solution in column 10 after dilution so that each well of the 96-well plate has 50 μL of diluted Ab. Columns 11 and 12 are included as internal controls, as virus-only and mock-only, respectively. Each Ab is tested in triplicate. The unused rows G and H can either be left empty or used, as part of triplicate row of cells, for another sample. Note: Although our protocol outlines a 2-fold dilution scheme of Abs, a higher dilution scheme (such as 3- or 5-fold dilutions) can also be used for potent NAbs.

-

4

In the BSL3, prepare ∼100−200 PFU/well of SARS-CoV-2 in an infection media in the biosafety cabinet. From the virus stock, calculate ∼1.0–2.0 x 104 PFU and mix in 5 mL (for one 96-well plate) of infection media. Note: The amount of virus per well can be further optimized based on the virus titer in the stock.

-

5

Add 50 μL of SARS-CoV-2 to columns 1–11 of the Ab plate and incubate the mixture for 1 h at 37 °C. Virus should be added starting at column 11, and sequentially up to column 1 to avoid any carry-over from high to low sample concentration wells. Tap the plate gently to mix the sample with the virus.

-

6

After incubation, remove cell maintenance media from the Vero E6 96-well plate. Transfer 50 μL of the Ab sample-virus mixture from the 96-well plate to the corresponding Vero E6 in 96-well plate using a multi-channel pipette. Incubate for 1 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator to allow virus adsorption.

-

7

After 1 h, remove the virus inoculum and overlay with post-infection media containing 1% Avicel. Incubate the infected Vero E6 cells for 24 h at 37 °C in the 5% CO2 incubator.

-

8

At 24 h post-infection (h p.i.), remove the infection media and fix/inactivate the plate in 10 % formalin solution for 24 h at 4 °C.

3.3.2. Post-treatment PRMNT assay

-

1

Vero E6 cells are maintained as described in the previous pre-treatment protocol.

-

2

Seed ∼1 × 104 Vero E6 cells/well the day before virus infection in 96-well plates. Note: The seeding density of Vero E6 in 96-well is ∼1 × 104 cells/well while cells at confluency is ∼4 × 104 cells/well.

-

3

On the day of infection, check the confluency of the Vero E6 cells under a light microscope. The optimal cell confluency is between 85–95 %.

-

4

Prepare a 2-fold serial dilution of the Ab or Ab containing sample in an empty, sterile 96-well cell culture plate using a post-infection media as previously described. Add 50 μL of 2% Avicel in post-infection media to each well containing the diluted Ab or media-only and no-virus control wells (columns 11 and 12, respectively) to give a final concentration of 1% Avicel in each well.

-

5

In the BSL3, prepare ∼100−200 PFU/well of SARS-CoV-2 in infection media in the biosafety cabinet. From the virus stock, calculate 1.0–2.0 x 104 PFU and mix in 5 mL (for one 96-well plate) of infection media.

-

6

Add 50 μL of virus inoculum to each well of the cell-cultured Vero E6 96-well plate from column 1–11, and incubate for 1 h at 37 °C in the CO2 incubator for virus adsorption.

-

7

After 1 h adsorption, remove the virus inoculum and replace with 100 μL of post-infection media containing the serially-diluted Ab with 1% Avicel.

-

8

Incubate the cells for 24 h at 37 °C in the CO2 incubator.

-

9

At 24 h p.i., remove media and fix/inactivate the plate in 10 % formalin solution for 24 h at 4 °C.

3.4. PRMNT assay to identify compounds with antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2

Several antiviral compounds are currently being evaluated for their effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 (Buonaguro et al., 2020; Elfiky, 2020; Park et al., 2020b; Xu et al., 2020). Different antiviral compounds target different steps of the viral replication cycle which provides the basis for the use of a PRMNT assay for antiviral screening. Hydroxychloroquine, a potential antiviral compound has been suggested to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 by blocking fusion to the cell membrane, (Fox, 1993; Yao et al., 2020). Other compounds in clinical trials, such as remdesivir, target the viral RdRp which is involved in SARS-CoV-2 replication (Buonaguro et al., 2020). This protocol can be adopted to screen the inhibitory effect and concentration of anti-SARS-CoV-2 compounds irrespective of the viral replication step. Although this protocol describes the antiviral activity in post-infection conditions, an alternative assay where the antiviral drug is provided before viral infection will help to provide information on the pre-entry mechanism of antiviral activity of the compound. The antiviral activity is determined by assessing the effective concentration that inhibits virus replication in Vero E6 cells (96-well plates, ∼4 × 104 Vero E6 cells/well at confluency, triplicate) following viral incubation for 24 h. It is important to include as a positive control in this antiviral PRMNT assay a drug with a known antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2, such as remdesivir (Elfiky, 2020). Unlike NAbs, some compounds could have cytotoxic effects. As a result, it becomes imperative to carry-out a cytotoxicity test (e.g. MTT assay) to evaluate for potential cytotoxicity of a given compound. Vero E6 cells for an MTT assay can be seeded on the same day as the cells for PRMNT assay so that the experiments can be conducted in parallel. Alternatively, our infrared staining technique can be used, concurrently, to evaluate cell viability in the same cells, in 96-well plates, used for PRMNT assay.

3.4.1. A PRMNT assay to identify SARS-CoV-2 antivirals

-

1

Vero E6 cells are maintained as described in the previous protocol.

-

2

Seed ∼1 × 104 Vero E6 cells/well the day before the virus infection in 96-well plates, using triplicate rows for each of the drugs that will be tested.

-

3

On the day of infection, check the confluency of the Vero E6 cells under a light microscope. The optimal cell confluency is between ∼85–95 %.

-

4

Prepare a 2-fold serial dilution of the antiviral in an empty, sterile 96-well cell culture plates using post-infection media. Briefly, add 50 μL of infection media to columns 2–12, and add 100 μL of 2X of the desired starting concentration of each antiviral to column 1. The starting concentration of the antiviral will, generally, depend on the type of drug being evaluated. We normally use a starting concentration of 50 μM for antivirals. Transfer 50 μL of antiviral from column 1 to column 2, and mix ∼ 10 times using a multi-channel pipette. Repeat this process from column 2 to column 10, changing the tips between dilutions to prevent transfer of residual antiviral. Discard 50 μL from the solution in column 10 after dilution so that each well of the 96-well plate has 50 μL of either diluted antiviral or no antiviral (for columns 11 and 12). Columns 11 and 12 are included as virus-only and mock-only control wells, respectively.

-

5

Add 50 μL of post-infection media containing 2% Avicel to each well in the 96-well plate.

-

6

Prepare ∼100−200 PFU/well of virus in post-infection media in the biosafety cabinet. From the virus stock, calculate ∼1.0–2.0 × 104 PFU and mix in 5 mL (for one 96-well plate) of infection media.

-

7

Remove media from the Vero E6 cells in the 96-well plate and add 50 μL of SARS-CoV-2 to columns 1–11. Incubate the plate for 1 h at 37 °C in the CO2 incubator to allow viral adsorption.

-

8

After viral adsorption, remove viral inoculum from the 96-well plate. Transfer 100 μL of the serially diluted sample containing 1% Avicel to the corresponding wells in the cell-cultured Vero E6 96-well plate using a multi-channel pipette.

-

9

Incubate infected Vero E6 cells in the 96-well plate for 24 h at 37 °C in the CO2 incubator.

-

10

At 24 h p.i., remove media and fix/inactivate the plates for 24 h at 4 °C with 10 % formalin solution.

3.5. Development of the PRMNT assays

For development of the PRMNT assays described above, we have optimized two different protocols with comparatively similar results: the peroxidase and the infrared staining techniques. The infrared staining technique holds the advantage of its capability to measure cell viability in addition to measuring antiviral activity. In the case of the peroxidase staining, a separate assay is needed to assess cell toxicity of NAbs or antiviral compounds. Both assays rely on the use of the SARS-CoV cross-reactive NP mAb, 1C7 (Amanat et al., 2020) but any other mAb targeting a SARS-CoV-2 viral antigen can be used in the peroxidase and the infrared staining described below.

3.5.1. Peroxidase staining

-

1

Once the plates are in the BSL2 after inactivation, remove residual formalin solution by gentle wash with double distilled water (DDW) before staining.

-

2

Gently wash the cells three times with 100 μL/well of PBS.

-

3

Permeabilize the cells with 100 μL/well of 0.5 % Triton X-100 dissolved in PBS, and incubate at room temperature (RT) for 15 min in the biosafety cabinet. Note: If you use an Ab against a viral surface protein (e.g. S), you can skip this permeabilization step.

-

4

Wash the cells with 100 μL/well of PBS, three times, and block with 100 μL/well of 2.5 % BSA in PBS. Incubate cells at 37 °C for 1 h.

-

5

Prepare primary Ab solution (anti-NP mAb, 1C7, 1 μg/mL) in 1% BSA, in PBS. Add 50 μL/well of primary Ab solution and incubate at 37 °C for 1 h.

-

6

After incubation with the primary Ab, wash each well three times with 100 μL/well of PBS.

-

7

Prepare the biotinylated anti-mouse Ab (VECTASTAIN® ABC-HRP Kit, Peroxidase (Mouse IgG); Vector Laboratory) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For one 96-well plate, add 75 μL of normal blocking serum stock and 25 μL of biotinylated secondary Ab stock to 5 mL of PBS. Add 50 μL/well of biotinylated Ab solution to each well, and incubate for 30 min at 37 °C.

-

8

Next, wash each well three times with 100 μL/well of PBS to remove biotinylated Ab solution thoroughly. Prepare VECTASTAIN ABC Reagent by following manufacturer’s instructions (VECTASTAIN® ABC-HRP Kit, Peroxidase (Mouse IgG); Vector Laboratory). For one 96-well plate, add 50 μL each of Reagent A (Avidin, ABC) and Reagent B (Biotinylated HRP, ABC) to 5 mL of PBS. Then, add 50 μL/well of VECTASTAIN ABC Reagent and incubate for 30 min at 37 °C.

-

9

Wash cells three times with 100 μL/well of PBS. Remove PBS, and dry the plate by gently blotting on paper towels. Prepare developing solution by following manufacturer’s instructions (DAB Substrate Kit, Peroxidase (HRP), with Nickel; Vector Laboratory).

-

10

Add 50 μL of developing solution to each well and wait for ∼3−5 min to visualize viral plaques.

-

11

Stop the reaction by removing the developing solution, and wash with PBS. It is important not to wait for too long once the plaques are discernible to prevent the entire cells from turning black.

-

12

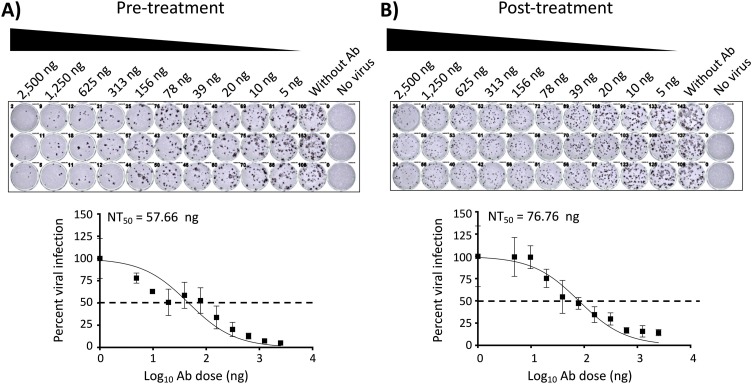

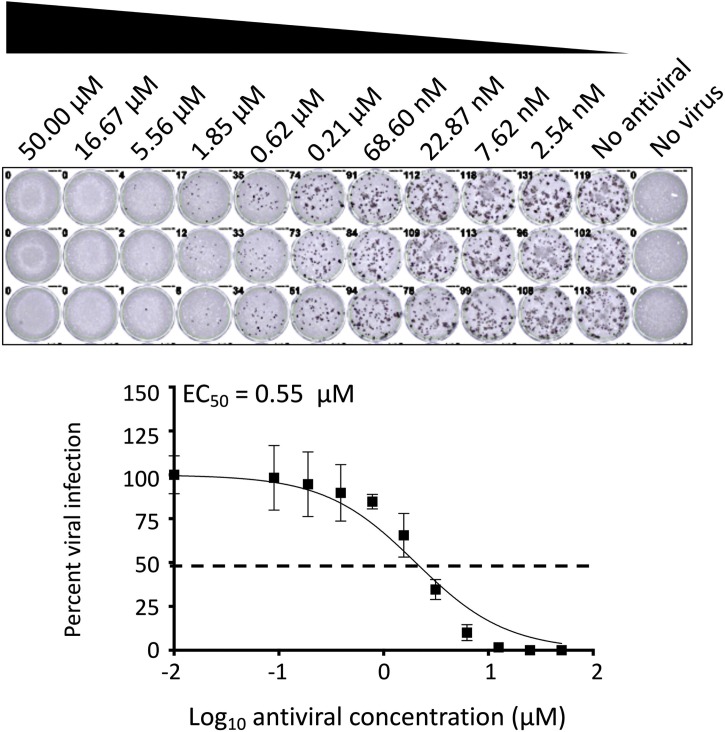

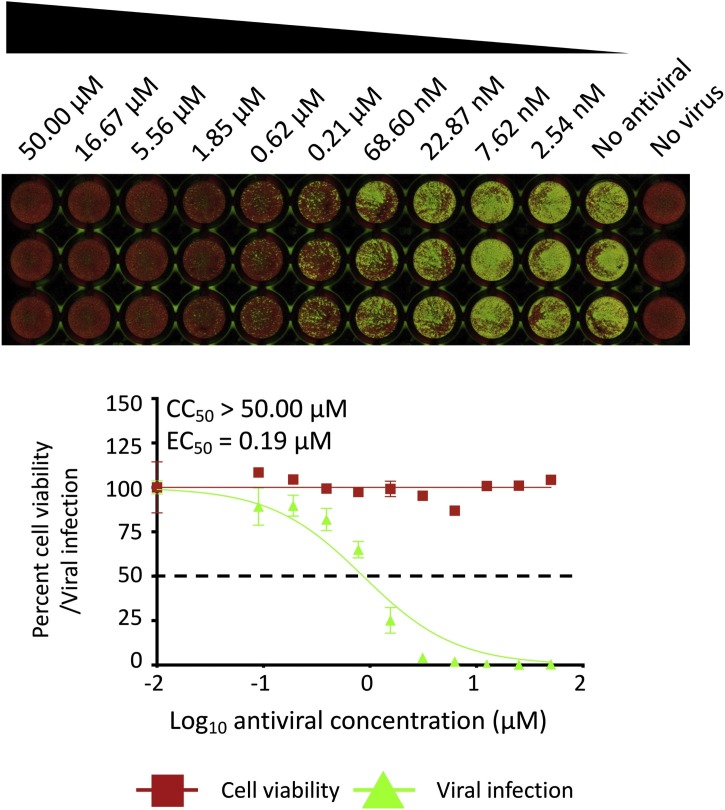

Take images and measure the stained positive cells using a CTL ImmunoSpot plate reader and counting software (Cellular Technology Limited, Cleveland, OH, USA). The formula to calculate percent viral infection for each concentration is given as [(Average # of plaques from each treated wells – average # of plaques from “no virus” wells)/(average # of plaques from “virus only” wells - average # of plaques from “no virus” wells)] x 100. A non-linear regression curve fit analysis over the dilution curve can be performed using GraphPad Prism to calculate NT50 or effective concentration 50 (EC50) of the Ab or antiviral (Fig. 2, Fig. 4 , respectively). Statistical evaluation using Friedman test for multiple comparisons failed to identify a difference between each replicates of assay (P value > 0.05 for each pair). The mean NT50 of pre-treatment was 57.66 ng from three independent biological replicates of 46.56 ng, 85.46 ng and 40.97 ng (Fig. 2A, P value = 0.7103) and the mean NT50 of post-treatment was 76.76 ng from three independent biological replicates of 94.74 ng, 79.50 ng and 56.03 ng (Fig. 2B, P value = 0.0924), respectively for mAb. The mean EC50 of viral inhibitor was 0.55 μM from 0.33 μM, 0.48 μM, and 0.84 μM (Fig. 4, P value = 0.1873) from three independent experiments.

Fig. 2.

PRMNT assay to identify SARS-CoV-2 NAbs, peroxidase staining. A) Pre-treatment: A 2-fold serially diluted NAb-containing sample was pre-incubated with SARS-CoV-2 (∼100-200 PFU/well) for 1 h at 37°C. After 1 h pre-incubation, confluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells were then infected with the sample-virus mixture for 1 h at 37°C. After 1 h of virus adsorption, the inoculum was removed and replaced with post-infection media containing 1% Avicel. B) Post-treatment: confluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 (∼100-200 PFU/well). After 1 h of virus adsorption, the inoculum was removed and replaced with post-infection media containing 1% Avicel with 2-fold serially diluted NAb-containing sample. A and B) At 24 h p.i., cells were fixed with 10 % formalin solution, immunostained with 1 μg/mL of a SARS-CoV cross-reactive NP mAb (1C7), and developed by POD anti-mouse Ab. The neutralizing titer 50 (NT50) was calculated as the highest dilution of the NAb-containing sample that prevents 50 % plaque formation in infected cells, determined by a sigmoidal dose response curve. Dotted line indicates 50 % neutralization. Data were expressed as mean and SD from triplicate wells.

Fig. 4.

A PRMNT assay to identify SARS-CoV-2 antivirals, peroxidase staining: Confluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 (∼100-200 PFU/well). After 1 h of virus adsorption, media was replaced with fresh infection media containing 1% Avicel and 2-fold serially diluted antiviral compound. At 24 h p.i., cells were fixed with 10 % formalin solution, immunostained with 1 μg/mL of a SARS-CoV cross-reactive NP mAb (1C7), and developed by POD anti-mouse Ab. The effective EC50 was calculated as the highest dilution of the antiviral that prevents 50 % plaque formation in infected cells, determined by a sigmoidal dose response curve. Dotted line indicates 50 % neutralization. Data were expressed as mean and SD from triplicate wells.

3.5.2. Infrared staining

-

1

Follow steps 1–6 as described for peroxidase staining.

-

2

After 1 h of incubation with primary Ab (1C7, 1 μg/mL), wash cells three times with 100 μL/well of PBS. Next, prepare secondary Ab (IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse IgG, 1:1,000 dilution) to stain virus-infected cells, and DRAQ5™ Fluorescent Probe Solution (1:4,000 dilution) to stain the nucleus using 1% BSA in PBS, and incubate for 1 h at RT.

-

3

Wash the cells three times with 100 μL/well of PBS to remove the secondary Ab and DRAQ5 thoroughly. Add 100 μL/well of PBS.

-

4

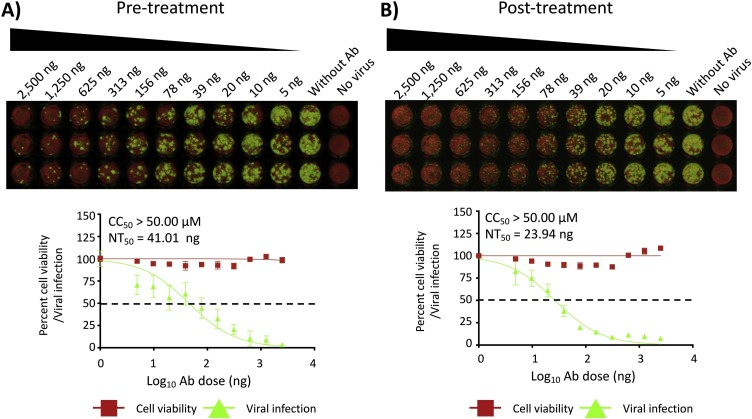

Obtain images and measure signal values of the stained positive cells with 700 nm (800CW, measuring viral infection) and 800 nm (DRAQ5, measuring cell viability) using Odyssey Sa Infrared Imaging System (LI−COR Biosciences, NE, USA). The formula to calculate percent viral infection (800 nm measurement) or cell viability (700 nm measurement) for each concentration is given as [(Average signal intensity from each treated wells – average signal intensity from “no virus” wells)/(average signal intensity from “virus only” wells - average signal intensity from “no virus” wells)] x 100. A non-linear regression curve fit analysis over the dilution curve can be performed using GraphPad Prism to calculate NT50 or EC50 of the Ab or antiviral (Fig. 3, Fig. 5 , respectively). Statistical evaluation using Friedman test for multiple comparisons failed to identify a difference between each replicates of assay (P value > 0.05 for each pair). The mean NT50 of pre-treatment was 41.01 ng from three independent biological replicates of 38.89 ng, 45.48 ng and 38.68 ng (Fig. 3A, P value = 0.6013) and the mean NT50 of post-treatment was 23.94 ng from three independent biological replicates of 29.63 ng, 26.62 ng and 15.57 ng (Fig. 3B, P value = 0.7103), respectively for mAb. The mean EC50 of viral inhibitor was 0.19 μM from 0.19 μM, 0.18 μM, and 0.20 μM (Fig. 5, P value = 0.1352) from three independent experiments.

Fig. 3.

PRMNT assay to identify SARS-CoV-2 NAbs, infrared staining. A and B) Confluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells were infected, fixed and stained with the primary NP 1C7 mAb as described in Fig. 2. After incubation with the primary Ab, cells were incubated, for 1 h, with IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse IgG secondary Ab, and DRAQ5™ Fluorescent Probe Solution for nuclear staining. Cells were then imaged using an Odyssey Sa infrared imaging system. The neutralizing titer 50 (NT50) was calculated as the highest dilution of the NAb-containing sample that prevents 50 % plaque formation in infected cells, determined by a sigmoidal dose response curve. Dotted line indicates 50 % neutralization. Data were expressed as mean and SD from triplicate wells.

Fig. 5.

A PRMNT assay to identify SARS-CoV-2 antivirals, infrared staining: Confluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells were infected, fixed, and stained with the primary NP 1C7 mAb as described in Fig. 3. After incubation with the primary Ab, cells were incubated, for 1 h, with IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse IgG secondary Ab, and DRAQ5™ Fluorescent Probe Solution for nuclear staining. Cells were then imaged using an Odyssey Sa infrared imaging system. The EC50 was calculated as the highest dilution of the antiviral that prevents 50 % plaque formation in infected cells, determined by a sigmoidal dose response curve. Dotted line indicates 50 % neutralization. Data were expressed as mean and SD from triplicate wells.

4. Discussion

As COVID-19 cases continue to increase across the globe, there is an urgent need to identify effective and safe prophylactics and/or therapeutics for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. In this study, we described robust assays and staining techniques which can be employed to evaluate the neutralizing and/or antiviral activity of Abs and/or antivirals, respectively, against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro.

The PRMNT assay described here measures the neutralization effect of Abs or the antiviral activity of compounds against SARS-CoV-2 in similar manner to what we have previously described with other viruses, including, among others, influenza (Baker et al., 2015; Bauman et al., 2013; Martinez-Sobrido et al., 2010; Nogales et al., 2019, 2015; Nogales et al., 2018, 2016; Park et al., 2020a; Piepenbrink et al., 2019; Rodriguez et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2016), mammarenaviruses (Brouillette et al., 2018; Ortiz-Riano et al., 2014; Robinson et al., 2016; Rodrigo et al., 2011), and Zika virus (Park et al., 2019). Although the assay described here was adapted to 96-well plate format, it can be adjusted to 384-well plate format for HTS of SARS-CoV-2 antivirals and/or NAbs. Many factors, including virus isolate, virus titer, cell condition or confluency, nature of samples, and incubation period can affect the outcome of this assay (Amanat et al., 2020). It is important to optimize these conditions so as to be able to generate accurate and reproducible data between different laboratories.

To restrict virus spread in infected cells, it is paramount to incubate the infected cells with post-infection media containing 1% Avicel. Incubation without Avicel will enhance a rapid cell-to-cell spread of virus resulting in higher NT50 or EC50. Although this assay works best in our hands using 1% Avicel, other reagents, such as 0.75 % carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) can also be used (Oladunni et al., 2019).

Both the peroxidase and the infrared staining described here measures the level of SARS-CoV-2 infection based on the staining SARS-CoV-2 NP. However, the staining techniques can also be adapted for Abs that recognizes other SARS-CoV-2 proteins. While both staining techniques are comparable with regards to NT50 and EC50 values, the infrared staining offers the advantage of measuring virus replication and cell viability in a single assay, saving time and reagents needed to separately evaluate cytotoxicity.

In conclusion, the assays described in this manuscript have unique features that would be useful to advance SARS-CoV-2 research. Contrary to similar published approaches (Amanat et al., 2020), our assays use two different readouts (POD and infrared) and both can be quantified using an ELISPOT plate reader (POD) or a LICOR imaging (infrared). Moreover, our assay can be used to identify antivirals and/or neutralizing antibodies in both pre- and post-treatment conditions. Importantly, the use of an ELISPOT plate reader (POD) or the LICOR imaging (infrared) provides the opportunity for quantifiable data on the antiviral or neutralizing activity of compounds or antibodies, respectively. They also provide with statistical data, including the EC50 of a given antiviral compound or the NT50 of antibodies. Notably, the experimental approach using the infrared staining (LICOR imaging) allows to assess, within the same assay, the potential toxicity of antivirals and/or neutralizing antibodies. Finally, the assays described here provide with reliable results after 24 h post-infection, reducing the time to identify antivirals or antibodies with inhibitory or neutralizing activities, respectively, against SARS-CoV-2.

Declaration of Competing Interest

J.G.P., F.S.O., M.P., M.W., J.K., and L.M.S. are listed as inventors on a pending patent application describing the SARS-CoV-2 antibody 1207B4.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank BEI Resources for providing the SARS-CoV-2 USA-WA1/2020 isolate (NR-52281). We want to thank Maritza Quintero for her technical assistance with the infrared staining with the Odyssey Sa Infrared Imaging System. We would also like to thank members at our institutes for their efforts in keeping them fully operational during the COVID-19 pandemic and the IBC committee for reviewing our protocols in a time efficient manner. We would like to dedicate this manuscript to all COVID-19 victims and to all heroes battling this disease.

References

- Amanat F., White K.M., Miorin L., Strohmeier S., McMahon M., Meade P., Liu W.C., Albrecht R.A., Simon V., Martinez-Sobrido L., Moran T., Garcia-Sastre A., Krammer F. An in vitro microneutralization assay for SARS-CoV-2 serology and drug screening. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2020;58:e108. doi: 10.1002/cpmc.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S.F., Nogales A., Santiago F.W., Topham D.J., Martinez-Sobrido L. Competitive detection of influenza neutralizing antibodies using a novel bivalent fluorescence-based microneutralization assay (BiFMA) Vaccine. 2015;33:3562–3570. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman J.D., Patel D., Baker S.F., Vijayan R.S., Xiang A., Parhi A.K., Martinez-Sobrido L., LaVoie E.J., Das K., Arnold E. Crystallographic fragment screening and structure-based optimization yields a new class of influenza endonuclease inhibitors. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:2501–2508. doi: 10.1021/cb400400j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogoch I.I., Watts A., Thomas-Bachli A., Huber C., Kraemer M.U.G., Khan K. Potential for global spread of a novel coronavirus from China. J. Travel Med. 2020:27. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillette R.B., Phillips E.K., Patel R., Mahauad-Fernandez W., Moller-Tank S., Rogers K.J., Dillard J.A., Cooney A.L., Martinez-Sobrido L., Okeoma C., Maury W. TIM-1 mediates dystroglycan-independent entry of Lassa virus. J. Virol. 2018:92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00093-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonaguro L., Tagliamonte M., Tornesello M.L., Buonaguro F.M. SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase as target for antiviral therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2020;18:185. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02355-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chary M.A., Barbuto A.F., Izadmehr S., Hayes B.D., Burns M.M. COVID-19: therapeutics and their toxicities. J. Med. Toxicol. 2020;16:284–294. doi: 10.1007/s13181-020-00777-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy K.T., Wong A.Y., Kaewpreedee P., Sia S.F., Chen D., Hui K.P.Y., Chu D.K.W., Chan M.C.W., Cheung P.P., Huang X., Peiris M., Yen H.L. Remdesivir, lopinavir, emetine, and homoharringtonine inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2020;178 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfiky A.A. Ribavirin, remdesivir, Sofosbuvir, Galidesivir, and Tenofovir against SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp): a molecular docking study. Life Sci. 2020;253 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferner R.E., Aronson J.K. Remdesivir in covid-19. BMJ. 2020;369:m1610. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox R.I. Mechanism of action of hydroxychloroquine as an antirheumatic drug. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;23:82–91. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(10)80012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C.J., Tchesnokov E.P., Feng J.Y., Porter D.P., Gotte M. The antiviral compound remdesivir potently inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:4773–4779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC120.013056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai M., Iwatsuki-Horimoto K., Hatta M., Loeber S., Halfmann P.J., Nakajima N., Watanabe T., Ujie M., Takahashi K., Ito M., Yamada S., Fan S., Chiba S., Kuroda M., Guan L., Takada K., Armbrust T., Balogh A., Furusawa Y., Okuda M., Ueki H., Yasuhara A., Sakai-Tagawa Y., Lopes T.J.S., Kiso M., Yamayoshi S., Kinoshita N., Ohmagari N., Hattori S.I., Takeda M., Mitsuya H., Krammer F., Suzuki T., Kawaoka Y. Syrian hamsters as a small animal model for SARS-CoV-2 infection and countermeasure development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009799117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juurlink D.N. Safety considerations with chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in the management of SARS-CoV-2 infection. CMAJ. 2020;192:E450–E453. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F. Structure, function, and evolution of coronavirus spike proteins. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2016;3:237–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Sobrido L., Cadagan R., Steel J., Basler C.F., Palese P., Moran T.M., Garcia-Sastre A. Hemagglutinin-pseudotyped green fluorescent protein-expressing influenza viruses for the detection of influenza virus neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 2010;84:2157–2163. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01433-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters P.S. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2006;66:193–292. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S., Nao N., Shirato K., Kawase M., Saito S., Takayama I. Enhanced isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by TMPRSS2-expressing cells. PNAS. 2020;117:7001–7003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002589117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montefiori D.C. Role of complement and Fc receptors in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 1997;18:371–390. doi: 10.1007/BF00813504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortola E., Roy P. Efficient assembly and release of SARS coronavirus-like particles by a heterologous expression system. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales A., Baker S.F., Martinez-Sobrido L. Replication-competent influenza A viruses expressing a red fluorescent protein. Virology. 2015;476:206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales A., Rodriguez-Sanchez I., Monte K., Lenschow D.J., Perez D.R., Martinez-Sobrido L. Replication-competent fluorescent-expressing influenza B virus. Virus Res. 2016;213:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales A., Piepenbrink M.S., Wang J., Ortega S., Basu M., Fucile C.F., Treanor J.J., Rosenberg A.F., Zand M.S., Keefer M.C., Martinez-Sobrido L., Kobie J.J. A highly potent and broadly neutralizing H1 influenza-specific human monoclonal antibody. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:4374. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22307-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales A., Avila-Perez G., Rangel-Moreno J., Chiem K., DeDiego M.L., Martinez-Sobrido L. A novel fluorescent and bioluminescent bireporter influenza a virus to evaluate viral infections. J. Virol. 2019:93. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00032-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oladunni F.S., Sarkar S., Reedy S., Balasuriya U.B.R., Horohov D.W., Chambers T.M. Equid herpesvirus 1 targets the sensitization and induction steps to inhibit the type I interferon response in equine endothelial cells. J. Virol. 2019:93. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01342-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization W.H. 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report-51.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=1ba62e57_10 [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Riano E., Ngo N., Devito S., Eggink D., Munger J., Shaw M.L., de la Torre J.C., Martinez-Sobrido L. Inhibition of arenavirus by A3, a pyrimidine biosynthesis inhibitor. J. Virol. 2014;88:878–889. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02275-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.G., Avila-Perez G., Madere F., Hilimire T.A., Nogales A., Almazan F., Martinez-Sobrido L. Potent inhibition of zika virus replication by aurintricarboxylic acid. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:718. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.G., Avila-Perez G., Nogales A., Blanco-Lobo P., de la Torre J.C., Martinez-Sobrido L. Identification and characterization of novel compounds with broad-spectrum antiviral activity against influenza A and B viruses. J. Virol. 2020:94. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02149-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.J., Yu K.M., Kim Y.I., Kim S.M., Kim E.H., Kim S.G., Kim E.J., Casel M.A.B., Rollon R., Jang S.G., Lee M.H., Chang J.H., Song M.S., Jeong H.W., Choi Y., Chen W., Shin W.J., Jung J.U., Choi Y.K. Antiviral efficacies of FDA-Approved drugs against SARS-CoV-2 infection in ferrets. mBio. 2020:11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01114-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman S., Netland J. Coronaviruses post-SARS: update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:439–450. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piepenbrink M.S., Nogales A., Basu M., Fucile C.F., Liesveld J.L., Keefer M.C., Rosenberg A.F., Martinez-Sobrido L., Kobie J.J. Broad and protective influenza B virus neuraminidase antibodies in humans after vaccination and their clonal persistence as plasma cells. mBio. 2019:10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00066-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reihani H., Ghassemi M., Mazer-Amirshahi M., Aljohani B., Pourmand A. Non-evidenced based treatment: an unintended cause of morbidity and mortality related to COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou B., Barriot P., Rimailho A., Baud F.J. Treatment of severe chloroquine poisoning. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;318:1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198801073180101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J.E., Hastie K.M., Cross R.W., Yenni R.E., Elliott D.H., Rouelle J.A., Kannadka C.B., Smira A.A., Garry C.E., Bradley B.T., Yu H., Shaffer J.G., Boisen M.L., Hartnett J.N., Zandonatti M.A., Rowland M.M., Heinrich M.L., Martinez-Sobrido L., Cheng B., de la Torre J.C., Andersen K.G., Goba A., Momoh M., Fullah M., Gbakie M., Kanneh L., Koroma V.J., Fonnie R., Jalloh S.C., Kargbo B., Vandi M.A., Gbetuwa M., Ikponmwosa O., Asogun D.A., Okokhere P.O., Follarin O.A., Schieffelin J.S., Pitts K.R., Geisbert J.B., Kulakoski P.C., Wilson R.B., Happi C.T., Sabeti P.C., Gevao S.M., Khan S.H., Grant D.S., Geisbert T.W., Saphire E.O., Branco L.M., Garry R.F. Most neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies target novel epitopes requiring both Lassa virus glycoprotein subunits. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11544. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo W.W., de la Torre J.C., Martinez-Sobrido L. Use of single-cycle infectious lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus to study hemorrhagic fever arenaviruses. J. Virol. 2011;85:1684–1695. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02229-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez L., Nogales A., Martinez-Sobrido L. Influenza a virus studies in a mouse model of infection. J. Vis. Exp. 2017 doi: 10.3791/55898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeman D., Fielding B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol. J. 2019;16:69. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang J., Wan Y., Luo C., Ye G., Geng Q., Auerbach A. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020;117:11727–11734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2003138117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Zheng X., Gai W., Zhao Y., Wang H., Wang H., Feng N., Chi H., Qiu B., Li N., Wang T., Gao Y., Yang S., Xia X. MERS-CoV virus-like particles produced in insect cells induce specific humoural and cellular imminity in rhesus macaques. Oncotarget. 2017;8:12686–12694. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Li W., Drabek D., Okba N.M.A., van Haperen R., Osterhaus A., van Kuppeveld F.J.M., Haagmans B.L., Grosveld F., Bosch B.J. A human monoclonal antibody blocking SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2251. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16256-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Wang A., Liu M., Wang Q., Chen J., Xia S., Ling Y., Zhang Y., Xun J., Lu L. 2020. Neutralizing Antibody Responses to SARS-CoV-2 in a COVID-19 Recovered Patient Cohort and Their Implications. [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Shi P.Y., Li H., Zhou J. Broad Spectrum Antiviral agent niclosamide and its therapeutic potential. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020;6:909–915. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Baker S.F., Gonzalez M.E., Topham D.J., Martinez-Sobrido L., Zand M., Holden-Wiltse J., Wu H. An improved method for estimating antibody titers in microneutralization assay using green fluorescent protein. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2016;26:409–420. doi: 10.1080/10543406.2015.1052475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X., Ye F., Zhang M., Cui C., Huang B., Niu P., Liu X., Zhao L., Dong E., Song C., Zhan S., Lu R., Li H., Tan W., Liu D. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]