Abstract

Objective

The standard data-collection procedure in the Norwegian national patient experience survey programme is post-discharge mail surveys, which include a pen-and-paper questionnaire with the option to answer electronically. A purely electronic protocol has not previously been explored in Norway. The aim of this study was to compare response rates, background characteristics, data quality and main study results for a survey of patient experiences with general practitioners (GPs) administered by the standard mail data-collection procedure and a web-based approach.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Setting

GP offices in Norway.

Participants

The sample consisted of 6999 patients aged 16 years and older registered with a GP in November 2018.

Intervention

Based on a three-stage sampling design, 6999 patients of GPs aged 16 or older were randomised to one of two survey administration protocols: Group A, who were mailed an invitation with both a pen-and-paper including an electronic response option (n=4999) and Group B, who received an email invitation with electronic response option (n=2000).

Main outcome measures

Response rates, background characteristics, data quality and main study results.

Results

The response rate was markedly higher for the mail survey (42.6%) than for the web-based survey (18.3%). A few of the background variables differed significantly between the two groups, but the data quality and patient-reported experiences were similar.

Conclusions

Web-based surveys are faster and less expensive than standard mail surveys, but their low response rates and coverage problems threaten their usefulness and legitimacy. Initiatives to increase response rates for web-based data collection and strategies for tailoring data collection to different groups should be key elements in future research.

Keywords: primary care, statistics & research methods, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The current study is the first to explore a purely electronic protocol in the national programme of patient experience surveys in Norway.

No previous surveys in the national programme have tested coverage and the quality of the email addresses in the national register for contact information.

The study did not use other available digital contact methods than email addresses, and the generalisability to health systems with different infrastructures and digital maturities is uncertain.

The study included adults evaluating their general practitioners, and the results might not be generalisable to other patient groups and healthcare settings.

Introduction

Norway introduced the regular general practitioner (GP) scheme in 2001. All inhabitants registered in the National Registry as Norwegian residents have the right to a GP/family doctor. Migrants eligible to stay in Norway for more than 6 months are entitled to enrol in the scheme. GPs in Norway play a key role in the provision of healthcare, and are often the first point of contact to acquire health services for most medical problems.1 In 2018, The Ministry of Health and Care Services decided to evaluate the GP scheme, and part of this evaluation comprised a national patient experience survey.

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) is responsible for conducting national patient experience surveys in Norway. Norway has a national programme for monitoring and reporting on the quality of healthcare using patient experience surveys. The purpose of this programme is to measure user experiences with healthcare systematically, with the obtained data used as a basis for interventions aimed at improving the quality of healthcare, healthcare management, patient choice and public accountability. The standard data-collection procedure in the national surveys is post-discharge mail surveys, which include a pen-and-paper questionnaire and an option to answer electronically.

The results from previous studies of survey-mode preferences in different patient populations both in Norway and other countries indicate that web mode surveys have lower response rates than other modes.2–11 In the national patient experience survey among patients visiting GPs in 2014 in Norway, only 18% of respondents answered electronically.4 However, the potential advantages of lower costs and shorter data-collection periods are important arguments for performing further research into web-based surveys. Also, the expansion of internet access and use may have changed the potential of the internet as an effective way to conduct such surveys.

When comparing the standard mail survey mode of data collection with web-based data collection the characteristics of non-respondents and respondents in both groups should be explored. The literature on the effects of background characteristics on the responses to different data collection methods are inconsistent.2–10 Non-response bias has been studied in four patient populations in Norway through follow-up telephone interviews with non-respondents,12–15 including non-respondents in a survey on patient experiences with GPs.15 The results have shown minor differences between the postal respondents from the national surveys and the postal non-respondents who have provided answers through follow-up interviews. In general, the impact of non-response bias in the large-scale surveys has been considered relatively small.

The use of internet in the general population is growing. In 2018, 90% of all Norwegian citizens used the internet on a daily basis.16 In all age groups under 60 years, between 90% and 99% reported using the internet daily, but corresponding results for those between 60 and 69 years was 81% and 67% for those aged 70 years or more. Seventeen per cent of the citizens aged 70 years or more reported that they never used the internet. Potential differences in population coverage between paper-based and web-based questionnaires and the risk of selection bias from using the internet for questionnaire surveys has been reduced, but a major concern with protocols that use only digital responses continues to be leaving out people without available digital contact information.

A purely electronic protocol for patient experience surveys has not previously been explored in the national programme for monitoring and reporting on healthcare quality in Norway. A main limitation of previous studies has been the lack of email addresses in the sample frame, with the implication that even the electronic group had to be invited by a postal invitation, adding to costs and precluding the possibility of testing a comprehensive electronic data collection option. The establishment of a national register with electronic contact information opens new possibilities regarding electronic and web-based surveys. A total of 88% of the population was registered in the national register for contact information in November 2018.17 So far, this register has not been used in our national patient experience surveys.

The aim of the current study was to compare the standard mail survey mode of data collection with exclusively web-based data collection in Norway. The sample was randomised to one of two survey administration protocols: patients in Group A were mailed an invitation with both pen-and-paper and electronic response options, while those in Group B received an email invitation with an electronic response option only (using email addresses obtained from the national register). The response rates, data quality, background characteristics and main study results were compared between the two groups.

Methods

Data

The sample consisted of patients aged 16 years and older registered with a GP in November 2018. The preconditions for the sampling frame were to report the results on a national level and to be able to estimate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) on the GP practice level. With the patient sample size chosen, we explored how the ICC varied dependent on the number of GPs at the practice level and found that at least four GPs were needed per GP practice to reach an acceptable ICC, and that not much was gained by including more GPs per practice. The sampling plan had a three-stage design. First, regular GP practices were randomly selected after stratification by the number of GPs per practice and municipality type. Second, all the GPs were included in the selected practices that had up to four GPs, while four of them were randomly selected in the practices that had five or more GPs. Third, we randomly selected 14 adult patients from the list of patients for each GP.

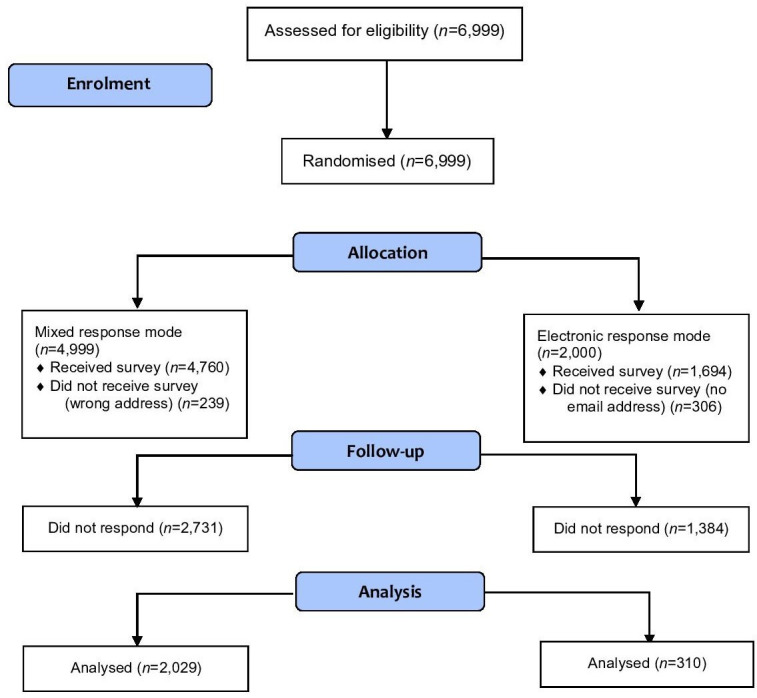

This study included a total of 6999 patients. Patients were randomised to 1 of 2 survey administration protocols: 4999 patients to the main sample (Group A) and 2000 patients to a subsample (Group B) (figure 1). The current study was the first to explore a purely electronic protocol in the national programme of patient experience surveys in Norway. The quality of the patient contact information collected from the national register was also previously unexplored. Considering the commission of achieving nationally representative results and the uncertainty regarding the responses from a purely electronic protocol, we evaluated the risk of randomising the total sample in two groups as too high and chose to include fewer patients in the subsample.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram.

Patients in Group A were mailed an invitation with both pen-and-paper and electronic response options. The invitation included a cover letter describing the purpose of the study, a paper questionnaire, a prepaid envelope and information and a login code to be able to respond electronically. The patients in Group B received an email invitation with an electronic response option only. The email invitation included information about the purpose of the study, a link to the online survey and a login code. Two reminders were sent to non-respondents in both samples using the same contact mode as the first invitation. The first reminder was sent to both groups around 3 weeks after the first contact. The second reminder was sent around 6 weeks after the first contact. All reminders to Group A were sent by mail and included a new invitation, the paper questionnaire, the postage-paid envelope and the login code to enable electronic responses. Group B were sent a new email invitation with a link to the survey and a login code in both reminders.

Background data about the patients were obtained from public registries, including gender, age, the number of years on the patient list of a GP, and the number of consultations during the past 24 months. Email addresses were collected from the national register for contact information, which is operated by the Agency for Public Management and eGovernment.

Measures

The Norwegian Patient Experiences with General Practitioner Questionnaire was applied. This instrument was developed and validated according to the standard scientific procedures of the national patient-reported experience programme in Norway.5 10

A national validation study identified five scales that covered important aspects of the GP service relating to accessibility, evaluations of the GP and auxiliary staff, cooperation between the GP and other services, and patient enablement. We included 17 additional items that were relevant for evaluating the GP scheme. The questionnaire used in the randomised study consisted of 47 questions on six pages. Thirty-seven questions addressed experiences with the GP service, while ten were background questions. Most of the questions related to the user-reported experiences were answered in a 5-point response format ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘to a very large degree’. Single item and index scores were transformed linearly from the 1 to 5 scale to a scale of 0–100. An additional page was included to allow the respondents to write comments related to experiences with their GPs and suggestions for future changes to the GP scheme.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were included in the development process of the instrument, securing the inclusion of the most important topics for patients. To identify important topics, we assessed reviews of the literature and consulted a reference group comprising GPs, researchers and representatives from health authorities and patient organisations throughout the process of questionnaire development. Cognitive interviews with patients were used to test the questionnaire. First, eight face-to-face interviews and nine telephone interviews were conducted. After an extensive revision, we conducted another 11 face-to-face interviews with patients. The revised version was tested in a pilot study.

Statistical analysis

The survey response rate by group was calculated as the proportion of eligible patients (ie, those who had not changed address, died, or were otherwise ineligible) who returned a completed survey (American Association for Public Opinion Research response rate 4.0).18

Items were assessed for levels of missing data, ceiling effects, and internal consistency. The internal consistency reliability of the five scales was assessed using the item-total correlation and Cronbach’s alpha. The item-total correlation coefficient quantifies the strength of an association between an item and the remainder of its indicator, with a coefficient of 0.4 considered acceptable.19 Cronbach’s alpha assesses the overall correlation between items within an indicator, and an alpha value of 0.7 is considered satisfactory.19 20 We set the cut-off criterion for ceiling effects to 50%; that is, an item was considered acceptable if fewer than 50% of the respondents chose the most-favourable response option.21 22

Differences in respondent characteristics between Group A and Group B were tested using Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables and independent-samples t-tests for continuous variables. Differences between the two groups regarding patient-reported experiences were tested using t-tests.

Differences in respondent characteristics between respondents and non-respondents in Group A and respondents and non-respondents in Group B were tested using Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables and independent-samples t-tests for continuous variables. Variables available on non-respondents were gender, age, time on the list of the GP, number of consultations during the past 24 months and number of diagnosis during the past 24 months.

All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (V.25.0).

Results

The overall response rate was 42.6% in Group A and 18.3% in Group B (table 1). 15% of the patients in the electronic arm lacked a valid email address in the national register, and 5% of the patients in the standard mail survey mode lacked a valid mailing address (figure 1). Most of the respondents (70.9%) in Group A answered on paper (table 1). The initial response rate was around 10% lower for Group B than for group A, with the remaining difference being related to reduced effects of both the first and second reminders.

Table 1.

Respondents before and after each reminder in the two randomised groups, and final response rates

| Group A (n=4760) | Group B (n=1694) | |

| Respondents before reminder | ||

| Electronic, n | 272 | 117 |

| Paper, n | 560 | – |

| Response rate, % | 17.5 | 6.9 |

| Respondents after first reminder | ||

| Electronic, n | 171 | 126 |

| Paper, n | 533 | – |

| Increase in response rate, % | 14.8 | 7.4 |

| Respondents after second reminder | ||

| Electronic, n | 148 | 67 |

| Paper, n | 345 | – |

| Increase in response rate, % | 10.4 | 4.0 |

| Total | ||

| Electronic, n (%) | 591 (29.1) | 310 |

| Paper, n (%) | 1438 (70.9) | |

| Response rate, % | 42.6 | 18.3 |

The levels of missing data, proportion of responses in the ‘not applicable’ option, ceiling effects and internal consistency for the items are presented in table 2. The levels of missing data ranged from 1.6% to 18.7% in Group A, and from 0.0% to 17.1% in Group B. The proportions of responses in the ‘not applicable’ category ranged from 3.0% to 29.4% in Group A, and from 1.6% to 31.9% in Group B, and were higher in Group A than in Group B for all items except for two on the enablement scale and the items on the coordination and cooperation scale. All scales and items were below the ceiling-effect criterion of 50% in Group A, but two items exceed the criterion in Group B: one about whether the GP takes the patient seriously (52.2%) and the other about whether the GP communicates in a way that the patient can understand (56.0%). Cronbach’s alpha values were similar in the two groups for four of the five indicators, but was lower (and below the criterion of 0.7) for the accessibility indicator in Group B. The remaining Cronbach’s alpha values were above 0.7.

Table 2.

Comparison of missing data, ceiling effects and internal consistency between the two randomised groups

| Scale and item* | Group A | Group B | ||||||

| Missing data (%) | Not applicable (%) | Ceiling effects (%) | Cronbach’s alpha/item-total correlation | Missing data (%) | Not applicable (%) | Ceiling effects (%) | Cronbach’s alpha/item-total correlation | |

| GP | 0.924 | 0.935 | ||||||

| Do you feel that your GP takes you seriously? | 5.0 | 3.4 | 48.0 | 0.762 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 52.2 | 0.813 |

| Do you feel that your GP spends enough time with you? | 4.9 | 3.2 | 28.9 | 0.702 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 32.7 | 0.745 |

| Do you feel that your GP talks to you in a way you understand? | 5.1 | 3.0 | 48.9 | 0.737 | 0.3 | 2.3 | 56.0 | 0.735 |

| Do you feel that your GP is professionally competent? | 5.2 | 4.0 | 41.8 | 0.752 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 43.1 | 0.805 |

| Do you feel that your GP shows interest in your situation? | 5.3 | 3.5 | 39.5 | 0.818 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 39.9 | 0.853 |

| Do you feel that your GP includes you as much as you would like in decisions concerning you? | 5.7 | 7.7 | 37.2 | 0.769 | 0.3 | 6.5 | 41.9 | 0.803 |

| Does your GP provide you with sufficient information about your health problems and their treatment? | 5.6 | 7.3 | 32.7 | 0.811 | 0.3 | 6.1 | 34.1 | 0.835 |

| Does your GP provide you with sufficient information about the use and side effects of medication? | 5.4 | 16.3 | 21.0 | 0.631 | 0.0 | 16.5 | 24.3 | 0.655 |

| Does your GP refer you to further examinations or a specialist when you feel you need it? | 5.1 | 10.6 | 43.2 | 0.646 | 0.3 | 10.6 | 49.3 | 0.633 |

| Organisation and auxiliary staff | 0.868 | 0.851 | ||||||

| Do you feel that your GP’s practice is well organised? | 5.2 | 4.1 | 26.6 | 0.681 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 25.8 | 0.615 |

| Do you feel the other employees are helpful and competent? | 4.9 | 3.6 | 36.1 | 0.813 | 0.3 | 2.9 | 31.7 | 0.806 |

| Are you treated with courtesy and respect at the reception? | 4.8 | 3.2 | 40.9 | 0.752 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 39.5 | 0.750 |

| Accessibility | 0.774 | 0.688 | ||||||

| Was the waiting time for your last urgent appointment acceptable? | 18.7 | – | 36.2 | 0.631 | 17.1 | – | 33.5 | 0.525 |

| Is this waiting time for appointments that are not urgent acceptable? | 12.3 | – | 18.0 | 0.631 | 6.8 | – | 11.4 | 0.525 |

| Enablement | 0.906 | 0.925 | ||||||

| Does contact with your GP make you better able to understand your health problems? | 1.6 | 16.6 | 19.5 | 0.803 | 1.0 | 15.8 | 26.0 | 0.836 |

| Does contact with your GP make you better able to cope with your health problems? | 1.6 | 19.7 | 16.3 | 0.852 | 0.6 | 20.3 | 21.2 | 0.875 |

| Does contact with your GP better help you to stay healthy? | 1.6 | 19.8 | 15.1 | 0.786 | 0.3 | 20.6 | 21.6 | 0.833 |

| Coordination and cooperation | 0.875 | 0.876 | ||||||

| Do you feel that your GP is good at coordinating the range of health services available to you? | 5.9 | 26.9 | 28.1 | 0.779 | 0.6 | 30.6 | 34.7 | 0.790 |

| Do you feel that your GP cooperates well with other services you need? | 5.7 | 29.4 | 29.0 | 0.779 | 0.6 | 31.9 | 29.7 | 0.790 |

*All items were scored on a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘to a very large degree’).

GP, general practitioner.

Table 3 compares the background characteristics of the respondents in the two survey administration protocols. Respondent age, time since previous contact and education level differed significantly between the two groups, yet there were no significant differences in gender, number of years on the list of the GP, number of consultations, number of diagnosis codes during the past 24 months, number of unique diagnosis codes the past 24 months, self-perceived physical health, self-perceived mental health, long-standing health problems or geographic origin. The proportion of patients aged 30–49 years was higher in Group B than in Group A (37.4% compared with 23.8%). In Group A, 31.8% of the patients were aged ≥67 years, a much higher proportion than in Group B where the corresponding proportion was 19.4%. The respondents in Group B were more likely to report that they had been in contact with their GP during the previous month than respondents in Group A. There was a significant tendency for those who responded to the email invitation to have a higher education level than those who responded to the mailed invitation: 61.5% of those in Group B reported being educated to the university level, compared with 47.0% in Group A.

Table 3.

Comparison of respondent characteristics between the two randomised groups

| Group A | Group B | P value* | |

| Gender, female | 55.9 (1135) | 59.7 (185) | 0.216 |

| Age group | <0.001 | ||

| 16–19 years | 2.4 (49) | 2.3 (7) | |

| 20–29 years | 7.8 (158) | 9.4 (29) | |

| 30–49 years | 23.8 (482) | 37.4 (116) | |

| 50–66 years | 34.2 (694) | 31.6 (98) | |

| ≥67 years | 31.8 (646) | 19.4 (60) | |

| Time on the list of the GP | 0.526 | ||

| <1 year | 9.4 (191) | 8.4 (26) | |

| 1–2 years | 19.4 (392) | 21.3 (66) | |

| 3–4 years | 14.5 (293) | 16.1 (50) | |

| 5–10 years | 20.4 (414) | 22.3 (69) | |

| ≥11 years | 36.3 (735) | 31.9 (99) | |

| Number of consultations during past 12 months | 0.672 | ||

| 0 | 9.3 (186) | 10.1 (31) | |

| 1 | 15.7 (314) | 15.3 (47) | |

| 2–5 | 55.7 (1114) | 52.1 (160) | |

| 6–12 | 16.2 (323) | 19.2 (59) | |

| ≥13 | 3.1 (63) | 3.3 (10) | |

| Number of diagnosis codes during past 24 months | 13.8±13.5 | 12.6±10.7 | 0.083 |

| Number of unique diagnosis codes during past 24 months | 4.7±3.2 | 4.6±2.8 | 0.51 |

| Time since previous contact | 0.042 | ||

| <1 month | 36.5 (716) | 42.1 (128) | |

| 1–3 months | 32.0 (628) | 23.7 (72) | |

| 4–6 months | 13.5 (266) | 15.1 (46) | |

| 7–12 months | 9.7 (191) | 8.9 (27) | |

| >12 months | 8.3 (163) | 10.2 (31) | |

| Self-perceived physical health | 0.951 | ||

| Very poor | 1.3 (27) | 1.6 (5) | |

| Quite poor | 5.3 (108) | 5.2 (16) | |

| Both poor and good | 23.8 (481) | 22.4 (69) | |

| Quite good | 48.3 (975) | 50.3 (155) | |

| Very good | 21.2 (429) | 20.5 (63) | |

| Self-perceived mental health | 0.475 | ||

| Very poor | 1.1 (22) | 1.9 (6) | |

| Quite poor | 3.0 (60) | 3.9 (12) | |

| Both poor and good | 15.5 (313) | 15.6 (48) | |

| Quite good | 41.7 (842) | 38.0 (117) | |

| Very good | 38.7 (781) | 40.6 (125) | |

| Long-standing health problems | 0.625 | ||

| 0 | 35.7 (708) | 37.5 (115) | |

| 1 | 32.9 (653) | 34.9 (107) | |

| 2 | 19.3 (383) | 16.9 (52) | |

| 3 | 12.1 (241) | 10.7 (33) | |

| Education level | <0.001 | ||

| Elementary school | 15.6 (309) | 7.1 (22) | |

| High school | 37.4 (740) | 31.4 (97) | |

| University, 0–4 years | 25.6 (505) | 35.3 (109) | |

| University, >4 years | 21.4 (422) | 26.2 (81) | |

| Geographic origin | 0.205 | ||

| Norway | 88.6 (1756) | 89.9 (276) | |

| Asia (incl. Turkey), Africa, or Latin America | 4.8 (95) | 3.3 (10) | |

| Eastern Europe (all countries, independent of EU membership) | 3.5 (70) | 2.3 (7) | |

| Western Europe, North America or Oceania | 3.0 (60) | 4.6 (14) | |

*Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables and independent-samples t-tests for continuous variables. Data are n (%) or mean±SD values.

EU, The European Union; GP, general practitioner.

Significant differences were found between Group A and Group B within respondents and non-respondents with respect to gender and age (table 4). In both groups, non-respondents tended to be more likely to be men and to be younger than respondents. Significant differences were also found for time on the list of the GP, number of consultations during the past 24 months and the two variables about number of diagnosis the last 2 years for Group A. Respondents tended to have been longer on the GPs list, and to have a higher number of consultations and diagnosis during the last 2 years. We found no additional differences between respondents and non-respondents in Group B.

Table 4.

Comparison of respondent characteristics between the two randomised groups

| Group A | Group B | |||||

| Respondents | Non-respondents | P value* | Respondents | Non-respondents | P value* | |

| Gender, female | 55.9 (1135) | 46.1 (1259) | <0.001 | 59.7 (185) | 49.8 (689) | 0.002 |

| Age group | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 16–19 years | 2.4 (49) | 7.3 (200) | 2.3 (7) | 6.4 (88) | ||

| 20–29 years | 7.8 (158) | 20.7 (566) | 9.4 (29) | 17.6 (243) | ||

| 30–49 years | 23.8 (482) | 39.5 (1080) | 37.4 (116) | 38.8 (537) | ||

| 50–66 years | 34.2 (694) | 21.2 (579) | 31.6 (98) | 26.0 (360) | ||

| ≥67 years | 31.8 (646) | 11.2 (306) | 19.4 (60) | 11.3 (156) | ||

| Time on the list of the GP | <0.001 | 0.739 | ||||

| <1 year | 9.4 (191) | 10.5 (288) | 8.4 (26) | 9.6 (133) | ||

| 1–2 years | 19.4 (392) | 24.3 (664) | 21.3 (66) | 23.3 (322) | ||

| 3–4 years | 14.5 (293) | 15.3 (419) | 16.1 (50) | 13.7 (189) | ||

| 5–10 years | 20.4 (414) | 20.9 (570) | 22.3 (69) | 22.3 (309) | ||

| ≥11 years | 36.3 (735) | 28.9 (790) | 31.9 (99) | 31.1 (431) | ||

| Number of consultations during past 24 months | 10.8±11.3 | 7.6±10.7 | <0.001 | 9.6±9.2 | 8.4±11.5 | 0.077 |

| Number of diagnosis codes during past 24 months | 13.8±13.5 | 11.3±14.1 | <0.001 | 12.6±10.7 | 12.2±14.9 | 0.611 |

| Number of unique diagnosis codes during past 24 months | 4.7±3.2 | 4.1±3.1 | <0.001 | 4.6±2.8 | 4.2±3.2 | 0.107 |

*Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables and independent-samples t-tests for continuous variables. Data are n (%) or mean±SD values.

GP, general practitioner.

Differences in patient-reported experiences between the two groups were small, varying from only 0.3 (GP is competent) to 3.5 (waiting time for appointments that are not urgent is acceptable) on a scale from 0 to 100 (table 5). There were no significant differences in the 5 indicators between the 2 groups, and only 1 of the 24 items was significantly different: the score for the item about the helpfulness and competence of other employees at GP practices was significantly higher in Group A than in Group B (p=0.046).

Table 5.

Comparison of patient-reported experiences between the two randomised groups

| Scale and item* | Group A | Group B | P value |

| GP | 78.3±16.8 | 78.8±17.8 | 0.651 |

| Do you feel that your GP takes you seriously? | 83.1±19.8 | 84.1±20.3 | 0.429 |

| Do you feel that your GP spends enough time with you? | 73.8±22.8 | 73.3±25.8 | 0.707 |

| Do you feel that your GP talks to you in a way you understand? | 84.6±17.7 | 85.8±19.1 | 0.275 |

| Do you feel that your GP is professionally competent? | 82.1±18.0 | 81.8±19.4 | 0.747 |

| Do you feel that your GP shows interest in your situation? | 79.7±20.5 | 78.7±22.2 | 0.435 |

| Do you feel that your GP includes you as much as you would like in decisions concerning you? | 79.0±20.3 | 80.0±21.3 | 0.452 |

| Does your GP provide you with sufficient information about your health problems and their treatment? | 76.6±21.2 | 76.1±22.2 | 0.708 |

| Does your GP provide you with sufficient information about the use and side effects of medication? | 65.0±26.9 | 67.1±26.0 | 0.241 |

| Does your GP refer you to further examination or a specialist when you feel you need it? | 81.4±20.2 | 82.0±22.2 | 0.712 |

| Organisation and auxiliary staff | 78.2±17.7 | 77.1±18.2 | 0.322 |

| Do you feel that your GP’s practice is well organised? | 75.2±20.2 | 74.8±20.4 | 0.735 |

| Do you feel the other employees are helpful and competent? | 79.3±19.2 | 76.9±20.8 | 0.046 |

| Are you treated with courtesy and respect at the reception? | 80.9±19.7 | 79.9±20.7 | 0.430 |

| Accessibility | 63.6±27.8 | 61.8±25.5 | 0.264 |

| Was the waiting time for your last urgent appointment acceptable? | 69.5±30.6 | 69.1±30.4 | 0.828 |

| Is this waiting time for appointments that are not urgent acceptable? | 58.3±30.0 | 54.8±28.5 | 0.051 |

| Enablement | 65.2±22.1 | 66.0±24.3 | 0.601 |

| Does contact with your GP make you better able to understand your health problems? | 68.1±23.0 | 68.7±25.1 | 0.703 |

| Does contact with your GP make you better able to cope with your health problems? | 64.9±24.0 | 65.9±25.6 | 0.560 |

| Does contact with your GP better help you to stay healthy? | 62.7±25.0 | 64.5±26.7 | 0.303 |

| Coordination and cooperation | 74.3±21.0 | 74.9±21.5 | 0.644 |

| Do you feel that your GP is good at coordinating the range of health services available to you? | 75.0±21.2 | 77.7±20.5 | 0.079 |

| Do you feel that your GP cooperates well with other services you need? | 74.3±22.6 | 73.0±24.5 | 0.434 |

Scale values are in bold

*All scales and items are scored from 0 to 100, where 100 is the best possible patient experience. Data are mean±SD values.

GP, general practitioner.

Discussion

This study compared response rates, background characteristics, data quality and main study results between two randomised data-collection groups in a national survey of patient experiences with GPs. Patients in Group A were mailed an invitation with both pen-and-paper and electronic response options, while those in Group B received an email invitation with an electronic response option only. The response rate was 2.3-fold higher for the mail protocol than for the web-based protocol, but the patient-reported experiences were similar in the two groups.

The current study of patient experiences with GPs is the first to explore a purely electronic protocol in the national programme for monitoring and reporting on healthcare quality using patient experience surveys in Norway. Web-based surveys have many advantages, including direct links to survey sites, ease of distribution, ease of receiving responses and lower costs, but a major concern is that they exclude those without an email address or with poor access to the internet. The existence of a national register in Norway with electronic contact information presents a major opportunity for large-scale surveys of patient experiences. The vast majority of the Norwegian population is included in the national register and use the internet on a daily basis, reducing potential variations in the population coverage between paper-based and web-based questionnaires and the risk of selection bias from using the internet for questionnaire surveys. However, as many as 15% of the patients in the electronic arm lacked a valid email address in the national registry, the corresponding number we could not reach in the standard mail data-collection was 5%. Furthermore, only 18% of the contacted sample in the web-based approach responded.

The results are consistent with a number of previous studies reporting that mail surveys achieve higher response rates than electronic and web-based approaches.2–11 A recent Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey produced similar results when comparing protocols based on web responses via an email invitation and mail.7 The mail protocol yielded more than twice the response rate of the web approach. A study of patient experiences with individual physicians showed that response rates were higher using mail (51%) than web (15%).9 In a study of patient experiences with outpatient clinics 14% responded to the web-based survey and 33% responded to the mail survey.8 When considering the completeness of the responses, we found that the web-based questionnaire had fewer missing values than the mail protocol, which is in line with previous studies. The levels of ceiling effects and internal consistency were similar in the two groups.

Despite the marked differences in response rates, the results showed minor differences in the level of patient reported experiences between the standard mail data-collection procedure and a web-based approach. There were no significant differences in the five indicators between the two groups, and only one single item score was significantly different between the two groups. These results are in line with other findings, that have shown only marginal differences in patient experiences and satisfaction between patients in web-based and other modes.2 3 7–9 There might be several reasons for the high correlation between the response modes. The surveys were designed to be as similar as possible, including the invitation letter, the content, layout and structure of the questionnaire and the timing of the first contact and reminders. The invitations to the patients in Group A and Group B were sent the same week and non-respondents in both groups received two reminders.

The response rate alone is a poor predictor of non-response bias, and previous studies have failed to find a consistent association between response rates and sample representativeness.23 24 However, low response rates threaten the legitimacy of surveys in both the clinical and public domains, and reduce the ability of surveys to identify important differences in patient-reported experiences between providers and over time.2 3 Future research needs to focus on effective initiatives for increasing response rates in web-based protocols, including sending multiple reminders using a combination of emails, messages on mobile phones and other available platforms. For example, the national infrastructure in Norway provides the possibility for secure digital mailboxes for all Norwegian inhabitants, which could be used for contacting digitally active patients.

The current study showed that a lower education level and higher age were associated with a mail preference. In the current study, we found that respondents invited by email were younger, more educated, and more likely to have had more recent contact with their GP. We found no significant intergroup differences in the remaining nine background variables. There are several methods for assessing non-response bias, including comparison of respondents and non-respondents on background variables.25 When we compared respondents with non-respondents, we found that men and younger patients were underrepresented as respondents in both groups. These differences are normally handled by non-response weighting, but such weights are only able to compensate for variables available in the sampling frame. We did not conduct further analysis of non-respondents, but previous follow-up studies of non-respondents in Norway indicate small additional bias.12–15 However, none of these have included a purely digital protocol, which warrant future non-response research for digital protocols. The coverage challenges for the digital sampling frame should be part of this research, as 12% of the population was not registered in the register, and 15% of the registered persons lacked a valid email address. This coverage challenge is an additional weakness of purely digital approaches and should be compensated with other response options for those excluded.

The effects of background characteristics reported in the literature are inconsistent.2–10 The results from two previous randomised studies showed similar background characteristics for respondents in different randomised groups.2 3 However, the respondents in those surveys were all contacted by mail. Future research should assess how the national infrastructure in Norway could be used to tailor the mode of data collection to different groups, such as by providing a range of data-collection modes from purely electronic strategies (for respondents with high education levels) to a mail-based mixed mode (to older respondents and those with low education levels).

Combined with the low response rates achieved for web-based protocols in this and other studies, future representative and high-quality surveys should include the opportunity to answer on pen-and-paper questionnaires. This could be implemented in a mixed-mode design that provides respondents with the option to choose how they want to respond, making it possible for patients without internet access or enough computer skills to also participate.

A limitation of this study is that it only included adults evaluating their GPs in Norway, and so the results might not be generalisable to other healthcare settings and countries. In particular, the national infrastructure and the digital maturity of the population in Norway might differ from the characteristics of other countries. However, the results should be applicable to health systems with similar infrastructures and digital maturities, and to countries working to establish regional or national digital infrastructures. The survey was not linked to a specific contact with the GP or GP office, or actual use for example, the last 6 months, which might have resulted in lower response rates and implies that we were unable to make any assumptions about specific contacts. Differences in respondent characteristics between respondents and non-respondents in both groups were tested, but not differences in patient reported experiences since we lacked a follow-up study of non-respondents. However, the impact of non-response bias in previous large-scale surveys have been relatively small.12–15

Conclusions

Administering a survey of patient experiences with GPs using a web-based protocol produced results that were very similar to those obtained using the standard mail-mode data-collection procedure used in the national surveys but had a much lower response rate. Furthermore, respondents in the digital group were younger, more educated, and had more recent experiences with their GPs. Men and younger patients were underrepresented as respondents in both groups. Web-based surveys are faster and cheaper than standard mail surveys, but their low response rates threaten their legitimacy. Initiatives to increase response rates for web-based data collection and strategies for tailoring data collection to different groups should be key elements in future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Inger Opedal Paulsrud from the NIPH for her help in conducting the survey, including performing administrative and technical tasks for the data collection. We would also like to thank Sylvia Drange Sletten, Marius Troøyen and Sindre Møgster Braaten from the NIPH for help developing the system for web-based data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: The Ministry of Health and Care Services initiated the study. HHI planned the study in consultation with OB and OH, HHI performed the statistical analyses with OB and OH and drafted the manuscript. OB and OH participated in the planning process, critically revised the manuscript draft and approved the final version of the manuscript. HHI was the project manager for the survey. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received grant from the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services (17/4584-12).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Data Protection Officer at the NIPH recommended that the study be approved, and it was formally approved by the research director of the division for health services at the NIPH. Number of approval: 20065. The Norwegian Directorate of Health approved the use of data about non-respondents in the nonresponse analysis, except those of patients who withdrew themselves from the study. Number of approval: 18/7876. Return of the questionnaire represented patient consent in the study, which is the standard procedure in all patient experience surveys conducted by the NIPH.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. The data set generated and/or analysed during this study is not publicly available due to the need to protect personal data.

References

- 1.Eide TB, Straand J, Rosvold EO. Patients' and GPs' expectations regarding healthcare-seeking behaviour: a Norwegian comparative study. BJGP Open 2018;2:bjgpopen18X101615. 10.3399/bjgpopen18X101615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjertnaes OA, Iversen HH. User-experience surveys with maternity services: a randomized comparison of two data collection models. Int J Qual Health Care 2012;24:433–8. 10.1093/intqhc/mzs031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjertnaes O, Iversen HH, Skrivarhaug T. A randomized comparison of three data collection models for the measurement of parent experiences with diabetes outpatient care. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:95. 10.1186/s12874-018-0557-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmboe O, Bjertnæs OA. Patient experiences with Norwegian hospitals in 2015. results following a national survey. PasOpp-report 147; 2016. ISSN 1890-1565. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmboe O, Danielsen K, Iversen HH. Development of a method for the measurement of patient experiences with regular general practitioners. PasOpp-report 1; 2015. ISSN 1890-1565. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danielsen K, Holmboe O, Hansen SL. Patient experiences with Norwegian primary care out-of-hours clinics. PasOpp-report 1; ISSN 1890-1565. Oslo: Results from a survey among the “Vakttårn” clinics. Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler FJ, Cosenza C, Cripps LA, et al. . The effect of administration mode on CAHPS survey response rates and results: a comparison of mail and web-based approaches. Health Serv Res 2019;54:714–21. 10.1111/1475-6773.13109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergeson SC, Gray J, Ehrmantraut LA, et al. . Comparing Web-based with Mail Survey Administration of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) Clinician and Group Survey. Prim Health Care 2013;3:1000132. 10.4172/2167-1079.1000132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez HP, von Glahn T, Rogers WH, et al. . Evaluating patients' experiences with individual physicians: a randomized trial of MAIL, Internet, and interactive voice response telephone administration of surveys. Med Care 2006;44:167–74. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196961.00933.8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmboe O, Iversen HH, Danielsen K, et al. . The Norwegian patient experiences with GP questionnaire (PEQ-GP): reliability and construct validity following a national survey. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016644. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iversen HH, Bjertnaes O, Helland Y, et al. . The adolescent patient experiences of diabetes care questionnaire (APEQ-DC): reliability and validity in a study based on data from the Norwegian childhood diabetes registry. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2019;10:405–16. 10.2147/PROM.S232166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guldvog B, Hofoss D, Pettersen KI, et al. . Ronning OM: PS-RESKVA -pasienttilfredshet i sykehus [PS-RESKVA -patient satisfaction in hospitals]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1998;118:386–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahle KA, Iversen H, Sjetne IS, et al. . Do non-respondents' characteristics and experiences differ from those of respondents? Poster at the the 25th International Conference by the Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua), Copenhagen, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iversen H, Dahle KA, Holmboe O. Using telephone interviews to explore potential non-response bias in a national postal survey.. Poster at the the 26th International Conference by the Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua), Dublin, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danielsen K, Iversen HH, Holmboe O. Telephone interviews to assess non-response bias in a postal user experience survey. Eur J Public Health 2015;25 10.1093/eurpub/ckv175.040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kompetanse Norge Befolkningens bruk AV digitale verktøy. Available: https://www.kompetansenorge.no/statistikk-og-analyse/grunnleggende-digital-ferdigheter/befolkingens-bruk-av-digitale-verktoy/#_ [Accessed 10 Jun 2020].

- 17.Digitaliseringsdirektoratet Befolkningens bruk AV digitale verktøy. Kontakt- OG reservasjonsregisteret. Available: https://samarbeid.difi.no/statistikk/kontakt-og-reservasjonsregisteret_ [Accessed 10 Jun 2020].

- 18.AAPOR Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. 9th edn The American Association for Public Opinion Research, 2016. https://www.aapor.org/Standards-Ethics/Standard-Definitions-(1).aspx [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3rd edn New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guildford, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjertnaes OA, Lyngstad I, Malterud K, et al. . The Norwegian EUROPEP questionnaire for patient evaluation of general practice: data quality, reliability and construct validity. Fam Pract 2011;28:342–9. 10.1093/fampra/cmq098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiz MA, Pardo A, Rejas J, et al. . Development and validation of the "Treatment Satisfaction with Medicines Questionnaire" (SATMED-Q). Value Health 2008;11:913–26. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00323.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groves RM, Peytcheva E. The impact of nonresponse rates on nonresponse bias: a meta-analysis. Public Opin Q 2008;72:167–89. 10.1093/poq/nfn011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groves RM. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opin Q 2006;70:646–75. 10.1093/poq/nfl033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halbesleben JRB, Whitman MV. Evaluating survey quality in health services research: a decision framework for assessing nonresponse bias. Health Serv Res 2013;48:913–30. 10.1111/1475-6773.12002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.