Abstract

Periodontitis has been associated with an increased risk of and mortality associated with human colorectal cancer (CRC). Current evidence attributes such an association to the direct and indirect effects of virulence factors belonging to periodontal pathogens, to inflammatory mediators and to genetic factors. The aims of the study were to assess the existence of a genetic linkage between periodontitis and human CRC, to identify genes considered predominant in such a linkage, thus named leader genes, and to determine pathogenic mechanisms related to the products of leader genes. Genes linking periodontitis and CRC were identified and classified in order of predominance, through an experimental investigation, performed via computer simulation, employing the leader gene approach. Pathogenic mechanisms relating to leader genes were determined through cross-search databases. Of the 83 genes linking periodontitis and CRC, 12 were classified as leader genes and were pathogenically implicated in cell cycle regulation and in the immune-inflammatory response. The current results, obtained via computer simulation and requiring further validation, support the existence of a genetic linkage between periodontitis and CRC. Cell cycle dysregulation and the alteration of the immuno-inflammatory response constitute the pathogenic mechanisms related to the products of leader genes.

Keywords: periodontitis, colorectal cancer, bioinformatics

1. Introduction

Periodontitis, as defined by Tonetti et al. and by Lang et al., is a “multifactorial microbially-associated inflammatory disease” affecting tooth-supporting structures and, ultimately, leading to tooth loss [1,2,3].

In the last decade, a growing body of evidence has reported the association between periodontitis and a variety of systemic inflammatory conditions and diseases, including atherosclerosis, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [4,5,6]. Most notably, recent findings have also associated periodontitis with solid cancers, such as malignant neoplasms of the prostate, breast, lung, pancreas, and kidney [6,7]. Moreover, periodontitis has been associated with an increased risk of colorectal adenoma and colorectal cancer (CRC) development [8,9] and to an increased mortality from CRC [10].

Human colorectal cancer accounts for approximately ten percent of new cancer cases worldwide in males and 9.2% in females [11]. Considering the high mortality rate of CRC (eight percent and nine percent of cases, corresponding to 700,000 estimated deaths/year) [11], together with the associated morbidity, progress in treatment customization [12] and, above all, in primary and secondary prevention, indicates the importance of new insights into CRC etiopathogenesis [13].

Several environmental factors [12] involved in CRC carcinogenesis have been identified: unhealthy behaviors, such as consumption of red meat and alcohol, smoking, reduced physical activity, IBD [14] (comprising Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) [15], and certain diseases and conditions, such as type 2 diabetes and obesity, which are related to systemic inflammation [16,17]. Indeed, it has been suggested that systemic inflammation may be critical to the development of CRC 13,16, and may link CRC with obesity, IBD, and periodontitis [6,7,18]. In particular, inflammatory mediators, which increase locally and systemically in periodontitis [10,19], together with carcinogens (i.e., nitrosamines), as well as microbial-associated virulence factors from periodontal pathogens, may underlie the association between human CRC and periodontitis.

In addition to environmental factors, genetic susceptibility and/or family history [12] have been recognized as important in ten percent of human CRC cases. The role of genetic factors [20] has been also demonstrated in periodontitis. Therefore, a genetic linkage between periodontitis and CRC has been hypothesized and was investigated in this study.

The primary aim of the present study was to assess, through an experimental investigation performed via computer simulation, the genetic linkages between periodontitis and human colorectal cancer, identifying all the genes involved in such an association, ranking them into cluster in descending order of relevance in such an association, and, finally, pointing out those genes presumed to be “leader” in the association between these disorders. Leader genes, which are considered to be predominant in the genetic determination of complex multi-factorial disorders, or in the genetic linkage between two disorders, as in the association between periodontitis and CRC, may reveal molecular targets for further investigations and focused therapies [20,21].

The secondary aim of the study was to characterize, through a review of current scientific evidence, the main function of leader gene products, their involvement in biological processes, and their role in the onset and progression of CRC and periodontitis, and to determine the putative pathogenic mechanisms associating periodontitis and CRC. Those preliminary data may highlight the possible clinical implications of the genetic linkages between periodontitis and human colorectal cancer and pave the way for targeted molecular experimentations [20,21].

2. Experimental Section

The present experimental study, being performed on computer, did not require either ethical approval or informed consent and was concluded on the 3 April 2019.

2.1. Analysis of the Genetic Linkage between Periodontitis and Human Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

A bioinformatic method, called leader gene approach [20], was employed to identify genes potentially involved in the association between periodontitis and CRC and especially those presumed to be predominant or “leader” in the genetic linkage between the two disorders.

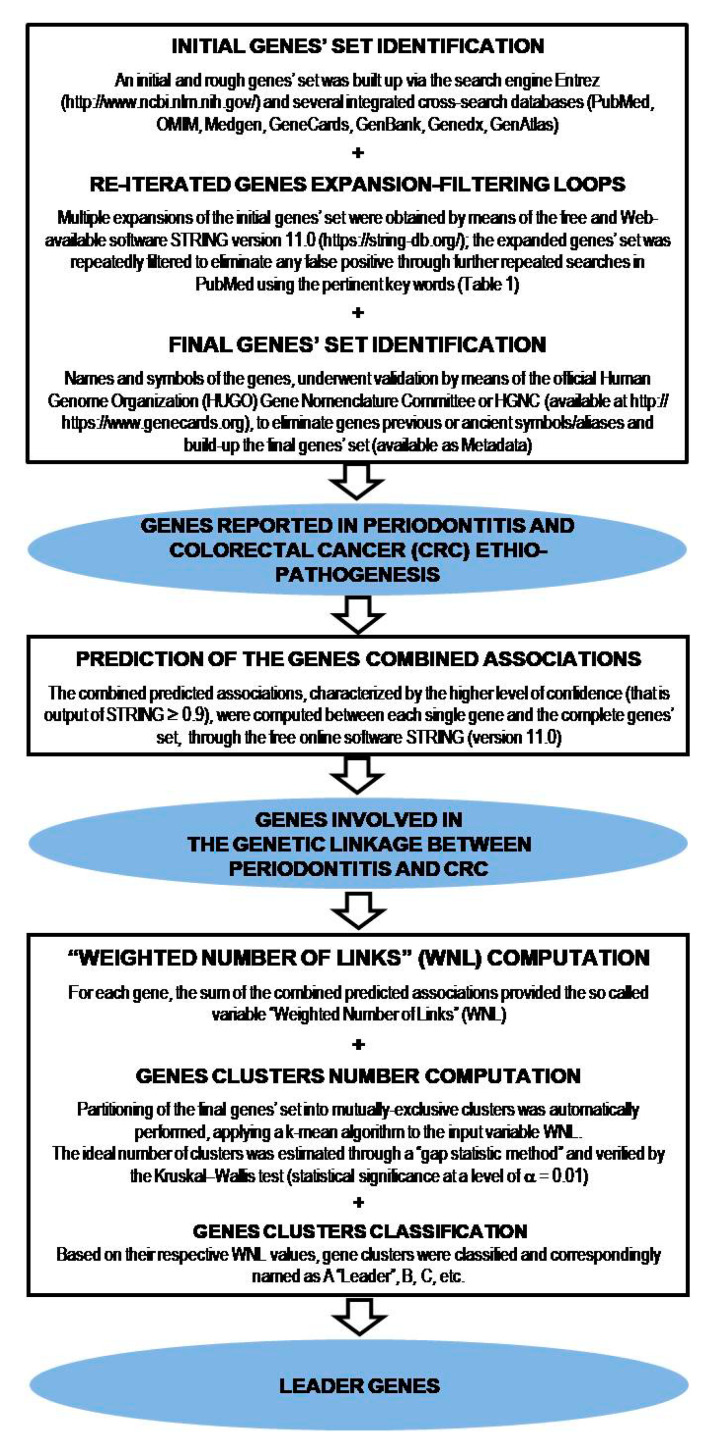

The multi-step procedure, requiring freely available databases and a specific software program for each of the steps involved, is detailed in Figure 1 and summarized below.

Figure 1.

Step by step description of the gene clustering analysis procedure, performed via computer simulation, to investigate the existence of a genetic linkage between periodontitis and human colorectal cancer, and to identify leader genes.

Preliminarily, an initial set of genes involved in the above-mentioned phenomenon was built up through various integrated cross-search databases (PubMed, OMIM, Medgen, GeneCards, GenBank, Genedx, GenAtlas) using the search engine Entrez (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Repeated genes expansions, obtained through the web-available software STRING version 11.0 (https://string-db.org/) ELIXIR infrastructure, Hinxton, UK, and subsequent expanded genes filtrations to eliminate any false positive, through a further search with PubMed, all together defined as “expansion-filtering loops”, were performed.

The following key words, achieved by studies investigating either colorectal cancer or periodontitis or both of them [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], were employed in the literature search and were logically combined with the Boolean operators AND, OR, NOT.

The name as well as the symbol of each gene, derived by the above-mentioned databases, underwent validation by means of the official Human Genome Organization (HUGO) Gene Nomenclature Committee, or HGNC (available at https://www.genecards.org), in order to eliminate previous symbols or aliases.

The combined predicted associations, characterized by the higher level of confidence (that is a result with a score ≥ 0.9), were computed between each single gene and the complete gene dataset, through the free online software STRING (Version 11.0) [22]. The sum of these combined predicted associations scores provided the so-called the “Weighted Number of Links” (WNL) for each gene.

Automatic computations were performed on the whole data related to the genes included in the study. A k-mean algorithm was applied to the input variable WNL, and a partitioning of the overall dataset of genes into mutually-exclusive clusters was automatically performed and a “gap statistic method” was used to estimate the ideal number of clusters for the clusters from 2 to 12, as reported in Figure 1. Significant differences among WNLs of cluster groups obtained by the gap statistic method, were found by the Kruskal-Wallis test (statistical significance at a level of α = 0.01), verifying the accurate estimate of the number of clusters.

The resulting gene clusters were classified and correspondingly named as A, B, C, etc., based on their respective value of WNL centroid. The first genes cluster was identified as a ”leader” genes cluster, hypothesizing their possible central role in the phenomenon; in contrast, the last genes cluster, identified as ”orphans” genes, included genes without identified predicted associations (WNL = 0).

2.2. Determination of the Putative Pathogenic Mechanisms Associating Periodontitis and CRC

Leader genes characterization was performed, via the free online software STRING (Version 11.0) [22], to assess the main function of leader gene products and their involvement in biological processes. A further literature search, using the keywords reported in Table 1, was conducted on PubMed/MEDLINE and ScienceDirect search engines (using the same key words reported in Table 1), to investigate the role of leader genes in the onset and in the progression of CRC as well as of periodontitis and to highlight their putative pathogenic mechanisms in the genetic linkage between periodontitis and CRC.

Table 1.

The following key words, achieved by studies investigating either colorectal cancer or periodontitis or both of them [16,18,19,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], were employed in the literature search and were logically combined with the boolean operators AND, OR, NOT.

| Key Words | |

|---|---|

| (1) | gene AND human |

| (2) | cancer |

| (3) | carcinoma |

| (4) | 2 OR 3 |

| (5) | colon |

| (6) | colonic |

| (7) | rectal |

| (8) | CRC |

| (9) | 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 |

| (10) | periodontitis |

| (11) | periodontal disease |

| (12) | periodontal inflammation |

| (13) | gingivitis |

| (14) | periodontal disruption |

| (15) | 10 OR 11 OR 12 OR 13 OR 14 |

| (16) | 1 AND 4 AND 9 AND 15 |

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Genetic Linkage between Periodontitis and Human Colorectal Cancer

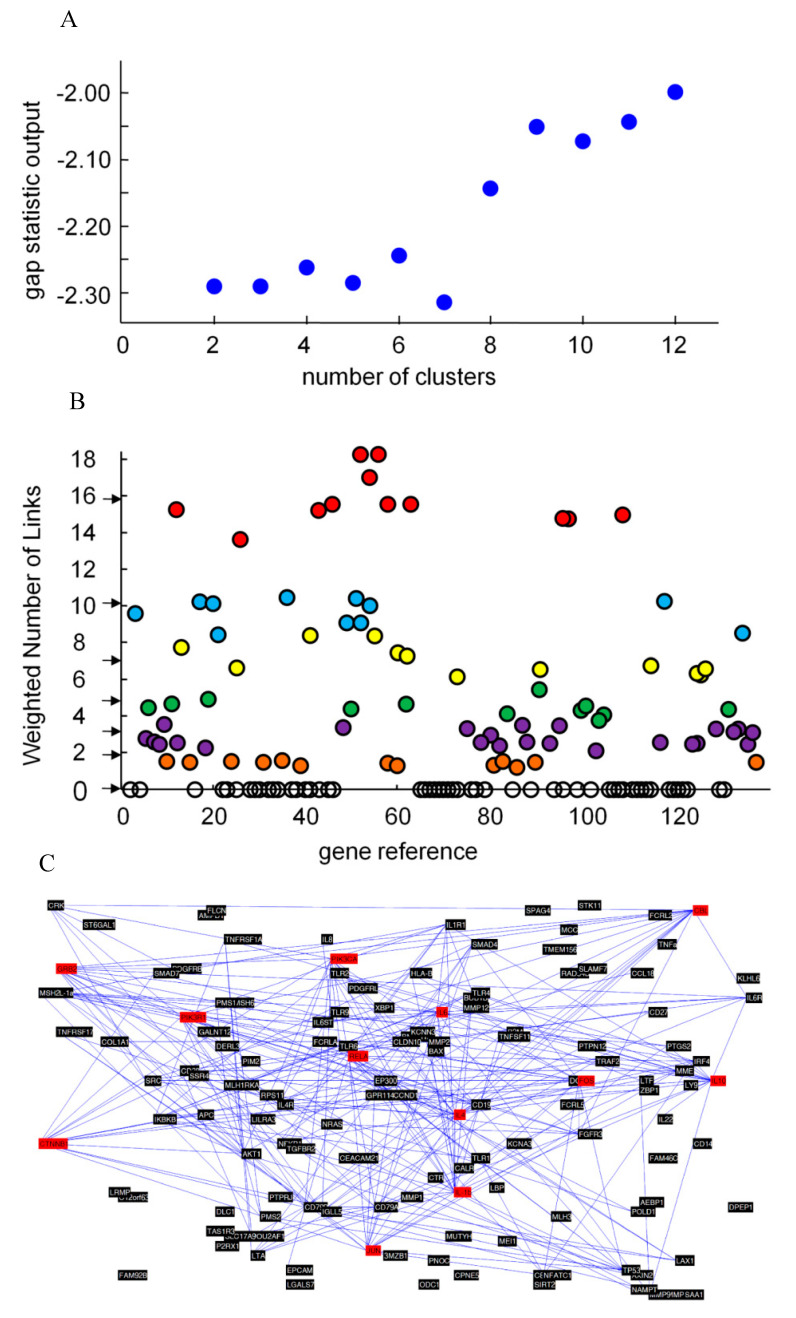

The final set of genes was composed of 137 genes. A complete description of the identified genes, including acronyms, identification numbers, validated names, cluster assignment, and their involvement in biological processes, is shown in Table A1. In compliance with the estimated optimal number of clusters, shown in Figure 2A, the 137 identified genes were divided into 7 clusters, designated as A, B, C, D, E, F, and orphan genes clusters.

Figure 2.

A–C. Data analysis for colorectal cancer and periodontal disease: (A) plot of the gap statistic method for estimating the number of clusters; (B) WNL for genes involved in the phenomenon. Black arrows are the centroids of the cluster groups: leader genes (in red); cluster B genes (in light blue); cluster C genes (in yellow); cluster D genes (in green); cluster E genes (in purple); cluster F genes (in orange); and ‘orphan’ genes (in clear); (C) final map of interactions of 137 genes involved in the genetic linkage between periodontitis and CRC according to STRING: leader genes are red; the lines that connect single genes represent predicted functional associations among proteins in the confidence view.

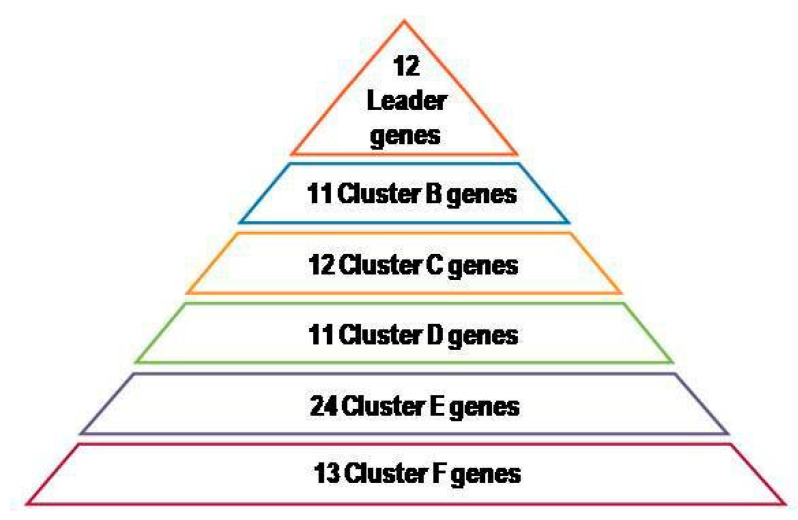

WNL computation is reported in Figure 2B. Depending on the WNL score, 54 genes, lacking combined predicted interactions (WNL = 0), were assumed not to be involved in the genetic linkage between periodontitis and CRC, and were, consequently, designated as orphan genes and excluded from the study; the remaining 83 genes, showing a WNL > 0 and the combined predicted interactions mapped in Figure 2C, were hierarchically grouped in descending order of WNL to the six clusters named from A to F, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Gene classification in the seven clusters, designated from A to F, based on the number of predicted interactions of genes, excluding the last orphan genes cluster with no predicted interactions.

In particular, the 12 genes, belonging to cluster A and defined as leader genes, were: E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (CBL), catenin beta-1 (CTNNB1), proto-oncogene c-Fos (FOS), growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (GRB2), interleukins 1B, 4, 6, 10 (IL1B, IL4, IL6, IL10), transcription factor AP-1 (JUN), phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha isoform (PIK3CA), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulatory subunit alpha (PIK3R1), and RELA proto-Oncogene NFKB subunit or transcription factor p65 (RELA).

CBL encodes for an enzyme targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation.

CTNNB1 encodes for β-catenin, a subunit of the adherens junctions complex, regulating cell growth and adhesion and Wnt responsive genes (i.e., c-Myc) expression, leading to cell cycle progression.

FOS is an oncogene encoding for the c-Fos protein, which heterodimerizes with c-Jun, encoded by JUN (Transcription factor AP-1), to form the transcription factor AP-1, involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and cancerous transformation.

GRB2 gene encodes for a protein binding the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, activating several signaling pathways.

IL1B, IL4, IL6, IL10 are active in immune-regulation and inflammation, as discussed below.

PIK3CA and PIK3R1 are centrally involved in several cancers.

RELA (p65), along with NFKB1 (p50), make-up the NFKB complex, which regulates the transcription of several genes encoding for pro-inflammatory cytokines https://www.genecards.org) [22].

3.2. Determination of the Putative Pathogenic Mechanisms Associating Periodontitis and CRC

The characterization of the 12 leader genes in the genetic linkage between periodontitis and human colorectal cancer is reported in Table 2. Identified leader genes were involved in cell signaling (i.e., CTNNB1, CBL, GRB2, PIK3CA, PIK3R1), transcriptional pathways (i.e., JUN, RELA), cell proliferation/differentiation (i.e., FOS), and immuno-inflammatory processes (i.e., IL1B, IL4, IL6, IL10). Current evidence of the role of leader genes in CRC and in periodontitis onset and progression, as well as the putative pathogenic mechanisms is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of the leader genes identified in the genetic linkage between periodontitis and human colorectal cancer: leader genes product(s) main function’, as per the free online software STRING (version 11.0) [22]; role in CRC development and progression; role in periodontitis onset and progression; putative pathogenic mechanisms related to the effects of the products of leader genes.

| Leader Genes | Main Function | Role in CRC | Role in Periodontitis | Putative Pathogenic Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTNNB1 | Cell signaling | Mutated in up to 90% of colonic tumors; responsible for initial tissue dysplastic transformation [22]; encodes for β-catenin, a subunit of the adherens junctions complex, regulating cell growth and adhesion and Wnt responsive genes (i.e., c-Myc) expression, leading to cell cycle progression. | Its product, β-catenin, is detectable in periodontal ligament cell nuclei in mice, potentially influencing periodontal ligament homeostasis [23]; regulates Wnt responsive genes. Wnt stimulus induces osteogenic lineage commitment [23], while Wnt depletion is involved in alveolar bone loss. | Cell cycle dysregulation |

| FOS | Gene(s) transcription, cell signaling, cell proliferation and differentiation | rs7101 and rs1063169 FOS single nucleotide polymorphisms are considered at higher risk of CRC onset [24] and its expression increases in CRC lesions [25]. In addition, a different member of the FOS family, named Fra-1, is over-expressed in colonic cancer cells, particularly in those acquiring motility and invasive ability [25]. Moreover, FOS may participate in the inflammatory microenvironment associated with CRC [25]. | May be implicated in periodontitis development and progression through the interaction with prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2, affecting the T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling [26]. | Cell cycle dysregulation |

| JUN | Gene(s) transcription, cell signaling, cell proliferation, and differentiation inflammation | Its product, c-Jun, heterodimerizes with c-Fos protein, encoded by FOS, to form the transcription factor AP-1 (see above). Involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and malignant transformation [24,27]. | Its product, c-Jun, heterodimerizes with c-Fos protein, encoded by FOS, to form the transcription factor AP-1 (see above). Involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and malignant transformation [24,27]. | Cell cycle dysregulation |

| GRB2 | Cell signaling | Its products stimulate colonic cell proliferation [28]; in particular, the Grb2-associated binding protein 2 (Gab2) has been found responsible for epithelial mesenchymal transition and consequent CRC metastasis development [29]. | Its products bind to the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor. EGF signaling in the periodontal tissue, indirectly affected by GRB2 expression, is considered essential in tissue regeneration; thus, its interruption may affect healing and regeneration processes. Indeed, EGF ligand alterations, secondary to the effect of the peptidylarginine deiminase enzyme, released by porphyromonasgingivalis, interfere with EGF signaling, and, potentially, favor periodontitis progression [30]. |

Cell cycle dysregulation |

| PIK3CA | Cell proliferation, cell survival | The most frequently mutated gene in breast cancer and is centrally involved in other malignancies [22]. | n.a. | Cell cycle dysregulation |

| PIK3R1 | Cell signaling | Phosphorylated by PIK3CA, it is downregulated in CRC cells [31]. | It is considered as a marker of severe periodontitis [32]. | Cell cycle dysregulation |

| IL6 | Inflammation | Induces CRC cell growth and invasion; and higher levels of IL6 have been detected in the serum from CRC patients compared to controls [33]. | Stimulates osteoclastogenesis [34], has been found associated with chronic as well as aggressive periodontitis and, together with IL6R, IL6ST, IL4R, and IL1R1 may link periodontitis to other diseases [20]. | Immuno-inflammatory response |

| IL1B | Immune response | In CRC cells it is produced in higher concentrations compared to healthy surrounding tissues, possibly activating the NFKB signaling pathway [35]. | IL1-889 C/T gene polymorphism has been associated with severe periodontitis [34] and its role in periodontitis pathogenesis has long been advocated [36]. | Immuno-inflammatory response |

| IL4 | Immuno-inflammatory process | Produced by activated T helper 2 lymphocytes, may reduce cancer-directed response operated by the immune system, encouraging cancer invasion and metastasis. Through its binding to Type II IL-4 receptor α (IL-4Rα) and JAK/STAT signaling activation, it favors survival of cancer cells and immunosuppression, so that a dysregulation in IL-4 signaling or IL-4Rα gene polymorphisms may be associated with cancer, including CRC [37]. | Plays a protective role in periodontitis progression, reducing alveolar bone loss. Consequently, IL4 gingivo-crevicular fluid levels are higher in periodontally healthy subjects and after non-surgical periodontal treatment. In addition, the IL4-590 C/T polymorphism has been reported as potentially associated with an increased risk of periodontitis development [38]. | Immuno-inflammatory response |

| IL10 | Gene(s) transcription | Its deficiency favors IBD malignant transformation to CRC [4,39], through the so called “inflammation-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence”, an alternative to the well-known “adenoma-carcinoma sequence” [2]. | Anti-inflammatory cytokine, down-regulating monocyte-macrophage response. Its gene polymorphism has been associated with periodontitis development in Caucasians [34]. | Immuno-inflammatory response |

| RELA | Cell signaling | Its expression is higher in malignant compared to healthy colonic cells, as well as in breast, liver, pancreatic, and gastric cancers, although its role in cancerogenesis, as well as in periodontitis, is still not fully elucidated [40]. | It is also classified as leader gene in periodontitis probably because it is functionally related to NFKB pro-inflammatory activity [22]. | Immuno-inflammatory response |

| CBL | Cell signaling | It may be related to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and CRC [41], as well as to atherogenesis, and neurodegenerative and autoimmune diseases, by a de-regulation in the ubiquitin–proteasome system, with subsequent NFKB activation and immuno-inflammatory response enhancement. | No evidence is available relating CBL to periodontitis [20]. | Immuno-inflammatory response |

4. Discussion

Periodontitis and human colorectal cancer are complex multi-factorial disorders, dealing with a multitude of genes, which are interconnected by several heterogeneous networks, and whose products are involved in a wide range of biological pathways [20]. In view of this fact, the present experimental investigation of the genetic linkages between periodontitis and CRC was conducted through a bioinformatic method, called “leader gene approach” [20]. This multi-step procedure, as described above, is especially useful in identifying the highest priority genes in the investigated phenomenon [20,21] and provides the necessary synthesis and analysis of the overwhelming amount of raw bioinformatic data generated. Ranking genes hierarchically and identifying leader genes consistently revealed those genes, and their related products, which are mainly involved in the genetic linkage between periodontitis and CRC (Table 2). Such bioinformatic data were subsequently integrated with current evidence to reveal cellular functions and biological processes carried out by the gene products, and were interpreted in view of the available clinical and experimental findings to determine the putative pathogenic mechanisms associating periodontitis with CRC.

4.1. Genetic Linkages between Periodontitis and Human Colorectal Cancer: Leader Genes and Putative Pathogenic Mechanisms

Among the 137 genes (complete final gene dataset available as metadata) reported in periodontitis and CRC ethio-pathogenesis, 83 were involved and 12 (“cluster A” or “leader” genes) were considered to play a predominant role in the genetic linkage between both disorders. Notably, four of the cluster A genes, specifically, CBL, GRB2, PIK3R1, and RELA, were also ranked among the five leader genes previously identified in periodontitis [20]. Nuclear factor kappa B p105 subunit (NFKB1), instead, which is considered as a leader gene in periodontitis, was assigned to cluster C in the present study. These results may support the existence of a possible genetic linkage between periodontitis and CRC.

The characterization of the currently identified leader genes, reported in Table 2, revealed their involvement in several biological processes, such as cell signaling (i.e., CTNNB1, CBL, GRB2, PIK3CA, PIK3R1), transcriptional pathways (i.e., JUN, RELA), cell proliferation/differentiation (i.e., FOS) and immuno-inflammatory processes (i.e., IL1B, IL4, IL6, IL10; see Table 2) [22]. Evidence supporting the role exerted by leader genes in both CRC and periodontitis pathogenesis [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], reported in Table 2, suggested that the pathogenic mechanisms underlying the association between periodontitis and CRC may be mainly related to the effect of the products of the leader genes on cell cycle dysregulation and on alteration of the immuno-inflammatory response.

Leader genes acting in cell cycle regulation, such as CTNNB1, FOS, JUN, GRB2, PIK3CA, and PIK3R1, may affect homeostasis in both colonic cells and periodontal tissues, causing, if dysregulated, colonic cell proliferation and malignant transformation, on the one hand, and periodontitis development and progression, on the other, as described in Table 2 [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

Leader genes affecting the immune-inflammatory response, such as IL1B, IL4, IL6, IL10, CBL, and RELA, may underlie a possible bi-directional relationship between the disorders, as described below [20,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Moreover, in addition to leader genes affecting the immune-inflammatory response, NFKB, which has been ranked among cluster C genes and is functionally related to RELA, regulates the transcription of several genes, also encoding for pro-inflammatory cytokines. NFKB is constitutively inactivated and its activation, with subsequent immuno-inflammatory response alteration, may be due to a dysregulation in the ubiquitin–proteasome system, which is a mechanism of intracellular protein degradation, occurring in atherogenesis, neurodegenerative and autoimmune diseases, and, possibly, in IBD and CRC [41,42]. Current knowledge about the role of the cellular ubiquitin–proteasome system dysregulation, and subsequent NFKB activation in periodontitis, is still limited, but it may explain the presence of the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (CBL) gene among the leader genes in the genetic linkage between periodontitis and CRC, although no evidence is available relating CBL to periodontitis [20].

4.2. Genetic Linkages between Periodontitis and Human Colorectal Cancer: Cytokines and Systemic Inflammation

Periodontal tissue destruction, occurring in periodontitis, is microbially initiated and sustained by the dysregulation of the immune-inflammatory processes [5]. A body of evidence has shown that cytokines produced in inflamed periodontal tissues, together with virulence factors from periodontal pathogens and oral microbial agents, may gain access to the circulation, and, consequently, induce systemic inflammation [5,43]. Accordingly, it has been proposed that non-resolving periodontal inflammation may affect systemic inflammatory diseases and that cytokines may be considered as a possible pathogenic link between periodontitis and various systemic diseases, including IBD and CRC [4,5,6,7,38,44].

It is well known that IBD has oral mucosal manifestations, such as pyostomatitis vegetans and aphthous stomatitis, and it has been reported that subjects suffering from Crohn’s disease show a higher risk of periodontitis compared to non-IBD subjects [8,45]. In addition, evidence suggests that periodontal pathogens, especially Fusobacterium nucleatum, may be involved in IBD [9,10] and colorectal adenomas [46], and that cytokines induced by periodontal pathogens and released in periodontitis may predispose to neoplastic transformation of chronic colitis, favoring colorectal carcinogenesis [12,46,47]. In more detail, oral fusobacterium nucleatum, which is abundant in the oral cavity and increased in periodontal pockets, is mobile and caplable to bind, through the Fusobacterium adhesin A (FadA), both to vascular endothelial-cadherins, gaining access to systemic circulation, and to (E)-cadherin on epithelial cells, stimulating the growth of tumor cells. Binding to (E)-cadherins on colorectal adenoma and cancer cells, FadA, which is only detectable on oral Fusobacterium species, activates the transcriptions of those oncogenes regulated by b-catenin, which is the product of the leader gene CTNNB1, and of some genes involved into the immune-inflammatory response, including IL6, which is presently ranked as a leader gene, and NFKB, belonging to cluster C genes [46]. From this standpoint, periodontitis may be considered as a possible risk factor for CRC genesis in IBD subjects, as it accounts for poor metabolic control in diabetic patients [48]. Such an inter-relationship may rely on the fact that both IBD and periodontitis share a multifactorial etiology, as well as the pathogenic mechanisms affecting the local immuno-inflammatory response, which leads to the genesis of a systemic inflammation [45]. Analogously, it may be supposed that those periodontal cytokines, which are listed among leader genes products, may enhance colonic tumor-associated inflammation, and may subsequently be considered as a risk factor for cancer progression in CRC subjects. As a counterpart, along with the tumor-associated inflammatory environment, CRC cells themselves release inflammatory mediators, which self-sustain neoplastic cell growth and enhance the cancerous cells’ interactions with the surrounding stroma and immune cells, favoring, in turn, CRC progression and invasion [13,49]. Since CRC inflammatory mediators have been identified as leader genes in the present study, it may be hypothesized, as previously proposed for cytokines released in diabetes [43], that CRC cytokines may negatively affect periodontitis onset and development, altering the immune-inflammatory response in periodontal tissues.

4.3. Genetic Linkages between Periodontitis and Human Colorectal Cancer: Possible Clinical Implications

The findings discussed, certainly requiring validation by larger studies, may provide preliminary data for further research, especially considering the beneficial clinical applications potentially offered by the insight into the mechanisms associating periodontitis and CRC. Indeed, if the results presented, which suggest a central role for cytokines and systemic inflammation in the genetic bi-directional linkage between periodontitis and CRC, are validated, periodontitis management may be included in CRC prevention and treatment plans. Complex multi-factorial disorders, such as periodontitis and CRC, significantly impact on the quality of life, present life-threatening risks, and imply a heavy burden on society. Therefore, highlighting the genetic traits of such disorders may pave the way for primary prevention strategies, which are essential to reduce the biological impact as well as the healthcare costs of these disorders. The improved understanding of the putative pathogenic mechanisms associating periodontitis with CRC may encourage a multidisciplinary approach, which is strongly advocated for such complex multifactorial disorders.

From this standpoint, oral health professionals may also become part of CRC screening plans, introducing, in their daily practice, general health promotion and disease prevention goals, and including risk assessment for both oral and systemic diseases. CRC screening might be improved by the provision of broader dental health records, with the potential to identify subjects at risk for CRC development for referral to a physician. In addition, based on the definition of oral health as a component of general health affecting the quality of life [50], oral health professionals may widen their activity in an interprofessional setting, providing oral and periodontal evaluation and necessary treatments, in CRC subjects referred by other health professionals, integrating the patient’s medical care in therapeutic and follow-up plans.

Periodontal treatment may be proposed as a CRC primary prevention strategy, in subjects considered at higher risk for CRC development, such as those suffering from IBD, in order to decrease the systemic inflammation and the related pro-carcinogenic environment. However, threshold values of cytokines in inflamed periodontal tissues, capable of inducing systemic inflammation and subsequently increasing the risk for colorectal cancer genesis, in IBD subjects have not yet been defined. Furthermore, the quantitative assessment of periodontal cytokines is even more complicated than the qualitative one, since it may actually be biased by the accidental detection of inflammatory mediators possibly derived from mucosal inflammation and orally administered drugs, in whole saliva analysis, and by the need for full mouth sampling, in gingival crevicular fluid analysis [51]. For these reasons, identifying those IBD subjects potentially exposed to a higher risk of systemic inflammation induced by periodontitis, and of consequent malignant transformation of chronic colitis, may be impracticable. Thus, periodontitis prevention and treatment, which potentially reduces systemic inflammation and, consequently, decreases the risk for malignant transformation of chronic colitis, may be routinely included in all IBD subjects’ treatment plans. Moreover, periodontal treatment, reducing the periodontal microbial load and the related cytokine levels, may decrease the systemic spread of inflammatory mediators and of Fusobacterium nucleatum, specifically, presumed to be associated with CRC, beyond IBD, lesions [41,46], and to favor tumor-associated environment, and may, therefore, constitute a secondary and/or tertiary prevention strategy in subjects affected by CRC.

5. Conclusions

Four out of the five leader genes previously identified for periodontitis (CBL, GRB2, PIK3R1, and RELA) were also listed as leader genes in the investigated phenomenon, carefully supporting the genetic linkages between CRC and periodontitis, and suggesting the need for a multi-disciplinary approach, also involving oral health professionals, to CRC subject management.

IL1B, IL4, IL6, IL10 were also ranked among leader genes, suggesting a central role for systemic inflammation in the genomic relationship between CRC and periodontitis; in particular, periodontitis may be linked to IBD, and, in turn, to CRC, both affecting the inflammatory pro-carcinogenic and tumor-associated environment and acting in an indirect way in the “inflammation-dysplasia” carcinogenic sequence, favoring colorectal cancer development. In this perspective, periodontitis management may be proposed as a CRC primary prevention strategy, especially in patients considered at higher risk for CRC development, such as IBD subjects. Indeed, periodontal therapy would reduce the periodontal microbial charge, and, consequently, the systemic widespread of bacterial toxins and of periodontal pathogens them-selves, including Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum, supposed to be associated with IBD and CRC lesions. Moreover, periodontal treatment and healthy periodontal conditions would indirectly decrease the systemic inflammation and the related CRC pro-carcinogenic environment, as a part of the CRC treatment strategy.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Identified genes acronyms, identification numbers, validated names, cluster assignment, and biological process(es) involvement description, as per the free online software STRING (version 11.0) [22].

| Gene Acronym | Gene Identification Number | Gene Official Name | Protein Main Function/Biological Process (Es) Involvement | Gene Cluster Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBL | 12 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase CBL | Cell signaling | A |

| CTNNB1 | 26 | Catenin beta-1 | Cell signaling | A |

| FOS | 43 | Proto-oncogene c-Fos | Gene (s) transcription, cell signaling, cell proliferation, and differentiation | A |

| GRB2 | 46 | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Binding Protein GRB2 | Cell signaling | A |

| IL1B | 52 | Interleukin 1 beta | Inflammation | A |

| IL4 | 54 | Interleukin 4 | Immune response | A |

| IL6 | 56 | Interleukin 6 | Immuno-inflammatory process | A |

| IL10 | 58 | Interleukin 10 | Inflammation | A |

| JUN | 63 | Transcription factor AP-1 | Gene(s) transcription | A |

| PIK3CA | 96 | Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha isoform | Cell proliferation, cell survival | A |

| PIK3R1 | 97 | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulatory subunit alpha | Cell signaling | A |

| RELA | 109 | RELA Proto-Oncogene, NF-KB Subunit or Transcription factor p65 | Sub-unit of the transcription factor NF-kappa-B | A |

| AKT1 | 2 | RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase | Cell proliferation, cell survival, angiogenesis | B |

| CD19 | 16 | B-lymphocyte antigen CD19 | Immune response | B |

| CD79A | 19 | B-cell antigen receptor complex-associated protein alpha chain | Immune response | B |

| CD79B | 20 | B-cell antigen receptor complex-associated protein beta chain | Immune response | B |

| EP300 | 35 | Histone acetyl transferase p300 | Regulates genes transcription via chromatin remodeling | B |

| IGLL5 | 48 | Immunoglobulin lambda like polypeptide 5 | Associated with solitary osseous plasmacytoma | B |

| IKBKB | 50 | Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta | Cell signaling (NF- kappa-B pathway) | B |

| IL-1a | 51 | Interleukin-1 alpha | Immuno-inflammatory process | B |

| IL1R1 | 53 | Interleukin-1 receptor type 1 | Cell signaling | B |

| SRC | 117 | Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src | Gene(s) transcription, immune response, cell cycle regulation, cell adhesion, and migration | B |

| TP53 | 134 | Cellular tumor antigen p53 | Cell cycle regulation | B |

| CCND1 | 13 | G1/S-specific cyclin-D | Cell cycle regulation | C |

| CRK | 25 | Adapter molecule crk | Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, cell motility | C |

| FGFR3 | 41 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 | Cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, and skeleton development | C |

| IL4R | 55 | Interleukin-4 receptor subunit alpha | Immune response | C |

| IL6R | 60 | Interleukin-6 receptor subunit alpha | Immuno-inflammatory process | C |

| IRF4 | 62 | Interferon regulatory factor 4 | Immune response, dendritic cell differentiation | C |

| LTA | 73 | Lymphotoxin-alpha | Immune response | C |

| NFKB1 | 91 | Nuclear factor NF-kappa-B p105 subunit | Cell signaling, immuno-inflammatory process, cell cycle regulation, and differentiation, tumorigenesis | C |

| SMAD4 | 115 | Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 | Muscle physiology | C |

| TLR2 | 125 | Toll-like receptor 2 | Immune response | C |

| TLR4 | 126 | Toll-like receptor 4 | Immune response | C |

| TLR6 | 127 | Toll-like receptor 6 | Immune response | C |

| AURKA | 5 | Aurora kinase A | Cell cycle regulation | D |

| B2M | 10 | Beta-2-microglobulin | Immune response | D |

| CD38 | 18 | ADP-ribosylcyclase/cyclic ADP-ribosehydrolase 1 | Synthesizes the second messengers cyclic ADP-ribose and nicotinate-adenine dinucleotide phosphate | D |

| IGJ | 49 | Immunoglobulin J chain | Immune response | D |

| IL6ST | 61 | Interleukin-6 receptor subunit beta | Cell signaling, immune response, hematopoiesis, pain control, bone metabolism | D |

| MMP9 | 83 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 | Extracellular matrix degradation, leukocyte migration, bone osteoclastic resorption | D |

| NFATC1 | 90 | Nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic 1 | Immuno-inflammatory process, osteoclastogenesis | D |

| PMS1 | 99 | PMS1 protein homolog 1 | DNA repair | D |

| PMS2 | 100 | Mismatch repair endonuclease PMS2 | DNA repair | D |

| POU2AF1 | 103 | POU domain class 2-associating factor | Immune response | D |

| PTGS2 | 104 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 | Inflammation | D |

| TNFRSF1A | 131 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A | (Pro) Apoptosis | D |

| APC | 4 | Adenomatous polyposis coli protein | Tumor suppressor (Wnt pathway) | E |

| AXIN2 | 6 | Axin-2 | Cell signaling (Wnt pathway) | E |

| BAX | 7 | Apoptosis regulator BAX | (Pro) Apoptosis | E |

| BMPR1A | 8 | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type-1A | Chondrocyte differentiation, Adipogenesis | E |

| CALR | 11 | Calreticulin | Cell endoplasmic reticulum formation | E |

| CD27 | 17 | CD27 antigen | Immune response | E |

| HLA-B | 47 | HLA class I histocompatibility antigen, B-7 alpha chain | Immune response | E |

| LTF | 74 | Lactotransferrin | Immuno-inflammatory process, protection against cancer development and metastasis | E |

| MLH1 | 77 | DNA mismatch repair protein Mlh1 | DNA repair | E |

| MME | 79 | Neprilysin | Opioid peptides, angiotensin-2, -1, -9 and atrial natriuretic factor degradation | E |

| MMP2 | 81 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 | Inflammation, tissue repair, angiogenesis, tumor invasion | E |

| MSH2 | 86 | DNA mismatch repair protein Msh2 | DNA repair | E |

| MSH6 | 87 | DNA mismatch repair protein Msh6 | DNA repair | E |

| NRAS | 96 | GTPase NRas | Binds GDP/GTP and possesses intrinsic GTPase activity | E |

| PDGFRB | 94 | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta | Tyrosine-protein kinase acting as cell-surface receptor, playing an essential role in blood vessel development | E |

| POLD1 | 102 | DNA Polymerase Delta 1 Catalytic Subunit | Plays a crucial role in high fidelity genome replication, requiring the presence of accessory proteins POLD2, POLD3, and POLD4 for full activity | E |

| SMAD7 | 116 | Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 7 | TGF-beta inhibition | E |

| TGFBR2 | 123 | TGF-beta receptor type-2 | Cell cycle regulation (epithelial and hematopoietic cells), cell proliferation and differentiation (mesenchymal cells) Immune response | E |

| TLR1 | 124 | Toll-like receptor 1 | Immune response | E |

| TLR9 | 128 | Toll-like receptor 9 | Immune response | E |

| TNFRSF17 | 132 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 17 | Immune response | E |

| TNFSF11 | 133 | Tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 11 | Immune response | E |

| TRAF2 | 135 | TNF receptor-associated factor 2 | NF-kappa-B and JNK activation, cell survival and apoptosis regulation, immune response | E |

| XBP1 | 136 | X-box-binding protein 1 | Cardiac, hepatic, and secretory tissue development | E |

| BUB1B | 9 | Mitotic checkpoint serine/threonine-protein kinase BUB1 beta | Cell cycle regulation | F |

| CCL18 | 14 | C-C motif chemokine 18 | Immune response | F |

| COL1A1 | 23 | Collagen alpha-1 (I) chain | Member of group I collagen | F |

| DCC | 30 | Netrin receptor DCC | Nervous system development | F |

| EPCAM | 34 | EPCAM Epithelial cell adhesion molecule | Immune response | F |

| FCRLA | 38 | Fc receptor-like A | Immune response | F |

| IL8 | 57 | Interleukin-8 | Immune response | F |

| IL22 | 59 | Interleukin-22 | Inflammation | F |

| MMP1 | 80 | Matrix metalloproteinase-1 | Types I, II, III, VII, and X collagens degradation | F |

| MMP7 | 82 | Matrix metalloproteinase-7 | Casein, type I, III, IV, and V gelatins and fibronectin degradation | F |

| MZB1 | 85 | Marginal zone B- and B1-cell-specific protein | Immune response | F |

| NAMPT | 89 | Nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase | Immune response, anti-diabetic function | F |

| ZBP1 | 137 | Z-DNA-bindin gprotein 1 | Immune response | F |

| AEBP1 | 1 | Adipocyte enhancer-binding protein 1 | Adipocyte proliferation, enhanced macrophage inflammatory responsiveness | Orphan |

| AMPD1 | 3 | AMP deaminase 1 | Energy metabolism | Orphan |

| CD14 | 15 | Monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 | Immune response | Orphan |

| CEACAM21 | 21 | Carcinoembryonic Antigen Related Cell Adhesion Molecule 21 | Immune response | Orphan |

| CLDN10 | 22 | Claudin-10 | Cell adhesion | Orphan |

| CPNE5 | 24 | Copine-5 | Melanocytes formation | Orphan |

| CTR | 27 | Calcitonin receptor | Receptor for calcitonin | Orphan |

| C12orf63 | 28 | Cilia- and flagella-associated protein 54 | Cilia and flagella assembly | Orphan |

| C8orf80 | 29 | Nuclear GTPase, Germinal Center Associated | Genome stability | Orphan |

| DERL3 | 31 | Derlin-3 | Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced pre-emptive quality control | Orphan |

| DLC1 | 32 | Rho GTPase-activating protein 7 | Cell proliferation and migration | Orphan |

| DPEP1 | 33 | Dipeptidase 1 | Immuno-inflammatory process | Orphan |

| FAM46C | 36 | Nucleotidyl transferase FAM46C | RNA polymerization | Orphan |

| FAM92B | 37 | Protein FAM92B | Ciliogenesis | Orphan |

| FCRL2 | 39 | Fc receptor-like protein 2 | Immune response, B-cells tumorigenesis | Orphan |

| FCRL5 | 40 | Fc receptor-like protein 5 | Immune response | Orphan |

| FLCN | 42 | Folliculin | Tumor suppression | Orphan |

| GALNT12 | 44 | Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase 12 | Oligosaccharide biosynthesis | Orphan |

| GPR114 | 45 | Adhesion G-protein coupled receptor G5 | Cell signaling | Orphan |

| KCNA3 | 64 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member 3 | Mediates the voltage-dependent potassium ion permeability of excitable membranes | Orphan |

| KCNN3 | 65 | Small conductance calcium-activated potassium channel protein 3 | Forms a voltage-independent potassium channel activated by intracellular calcium | Orphan |

| KLHL6 | 66 | Kelch-like protein 6 | Immune response | Orphan |

| LAX1 | 67 | Lymphocyte trans membrane adapter 1 | Immune response | Orphan |

| LBP | 68 | Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein | Immune response | Orphan |

| LGALS7 | 69 | Galectin-7 | Cell growth control | Orphan |

| LILRA3 | 70 | Leukocyte Immunoglobulin Like Receptor A3 | Immune response | Orphan |

| LY9 | 71 | T-lymphocyte surface antigen Ly-9 | Immune response | Orphan |

| LRMP | 72 | Lymphoid-restricted membrane protein | Immune response | Orphan |

| MCC | 75 | Colorectal mutant cancer protein | Tumor suppression | Orphan |

| MEI1 | 76 | Meiosis inhibitor protein 1 | Meiosis | Orphan |

| MLH3 | 78 | DNA mismatch repair protein Mlh3 | DNA repair | Orphan |

| MMP12 | 84 | Macrophage metalloelastase | Tissue remodeling | Orphan |

| MUTYH | 88 | Adenine DNA glycosylase | DNA repair | Orphan |

| ODC1 | 93 | Ornithine decarboxylase | DNA replication, cell proliferation, and apoptosis | Orphan |

| PDGFRL | 95 | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-like protein | Associated with colorectal cancer and other malignancies | Orphan |

| PIM2 | 98 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase pim-2 | Cell proliferation, cell survival | Orphan |

| PNOC | 107 | Prepronociceptin | Nociception, neuronal development | Orphan |

| PTPN12 | 105 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 12 | Cell signaling | Orphan |

| PTPRJ | 106 | Receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase eta | Cell proliferation and differentiation, cell adhesion and migration, platelet activation, and thrombosis | Orphan |

| P2RX1 | 107 | P2X purinoceptor 1 | Synaptic transmission | Orphan |

| RAD54B | 108 | DNA repair and recombination protein RAD54B | DNA repair | Orphan |

| RPS11 | 110 | Ribosomal protein S11 | 40S sub-unit ribosomal protein | Orphan |

| SAA1 | 111 | Serumamyloid A-1 protein | Inflammation | Orphan |

| SIRT2 | 112 | NAD-dependent protein deacetylase sirtuin-2 | Cell cycle regulation | Orphan |

| SLAMF7 | 113 | SLAM family member 7 | Immune response | Orphan |

| SLC17A9 | 114 | Solute carrier family 17 member 9 | ATP storage and exocytosis | Orphan |

| SPAG | 118 | RNA polymerase II-associated protein 3 | RNA polymerization | Orphan |

| SSR4 | 119 | Translocon-associated protein subunit delta | Retention of ER resident proteins regulation | Orphan |

| STK11 | 120 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase STK11 | Tumor suppression | Orphan |

| ST6GAL1 | 121 | Beta-galactoside alpha-2,6-sialyltransferase 1 | Transfers sialic acid from CMP-sialic acid to galactose-containing acceptor substrates | Orphan |

| TAS1R3 | 122 | Taste receptor type 1 member 3 | Umami taste stimulus response | Orphan |

| TMEM156 | 129 | Transmembrane protein 156 | Transmembrane protein | Orphan |

| TNFa | 130 | Tumor necrosis factor | Cell proliferation and differentiation, tumor cells death | Orphan |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.D.S., P.T., V.P., and L.S.; methodology, F.D.S., P.T., V.P., and L.S.; software, P.T.; validation, X.X., Y.Y., and Z.Z.; formal analysis, P.T.; investigation, F.D.S. and P.T.; resources, F.D.S.; data curation, F.D.S., P.T., V.P., F.C., D.L., and L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.D.S., P.T., and L.S.; writing—review and editing, F.D.S., P.T., V.P., F.C., D.L., and L.S.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tonetti M.S., Greenwell H., Kornman K.S. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J. Periodontol. 2018;89:159–172. doi: 10.1002/JPER.18-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lang N.P., Bartold P.M. Periodontal health. J. Periodontol. 2018;89:9–16. doi: 10.1002/JPER.16-0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sbordone L., Sbordone C., Filice N., Menchini-Fabris G., Baldoni M., Toti P. Gene clustering analysis in human osseous remodeling. J. Periodontol. 2009;80:1998–2009. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soory M. Association of periodontitis with rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerosis: Novel paradigms in etiopathogeneses and management? Open Access. Rheumatol. 2010;2:1–6. doi: 10.2147/OARRR.S10928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapple I.L.C., Genco R., Working group 2 of the joint EFP/AAP workshop Diabetes and periodontal diseases: Consensus report of the Joint EFP. J. Periodontol. 2013;84:106–112. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.1340011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michaud D.S., Liu Y., Meyer M., Chung M. Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and cancer risk in male health professionals: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:550–558. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70106-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee D., Jung K.U., Kim H.O., Kim H., Chun H.K. Association between oral health and colorectal adenoma in a screening population. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e12244. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Momen-Heravi F., Babic A., Tworoger S.S., Zhang L., Wu K. Periodontal disease, tooth loss and colorectal cancer risk: Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Int. J. Cancer. 2017;140:646–652. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hussan H., Clinton S.K., Roberts K., Bailey M.T. Fusobacterium’s link to colorectal neoplasia sequenced: A systematic review and future insights. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017;23:8626–8650. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren H.G., Luu H.N., Cai H., Xiang Y.B. Oral health and risk of colorectal cancer: Results from three cohort studies and a meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2016;27:1329–1336. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Dikshit R., Eser S. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136:359–386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo Y., Bao Y., Ma M., Yang W. Identification of Key Candidate Genes and Pathways in Colorectal Cancer by Integrated Bioinformatical Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:722. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krzystek-Korpacka M., Diakowska D., Kapturkiewicz B., Bebenek M., Gamian A. Profiles of circulating inflammatory cytokines in colorectal cancer (CRC), high cancer risk conditions, and health are distinct. Possible implications for CRC screening and surveillance. Cancer Lett. 2013;337:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triantafillidis J.K., Nasioulas G., Kosmidis P.A. Colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease: Epidemiology, risk factors, mechanisms of carcinogenesis and prevention strategies. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2727–2737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abraham C., Cho J.H. Inflammatory bowel disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:2066–2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li S.K.H., Martin A. Mismatch repair and colon cancer: Mechanisms and therapies explored. Trends. Mol. Med. 2016;22:274–289. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flood A., Rastogi T., Wirfält E., Mitrou P., Reedz J., Subar A., Kipnis V., Mouw T., Hollenbeck A., Leitzmann M., et al. Dietary patterns as identified by factor analysis and colorectal cancer among middle-aged Americans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;88:176–184. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.1.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersen P.E., Ogawa H. The global burden of periodontal disease: Towards integration with chronic disease prevention and control. Periodontology 2000. 2012;60:15–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han B., Fengm D., Yu X., Zhang Y., Liu Y. Identification and Interaction Analysis of Molecular Markers in Colorectal Cancer by Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018;24:6059–6069. doi: 10.12659/MSM.910106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Covani U., Marconcini S., Giacomelli L., Sivozhelevov V., Barone A., Nicolini C. Bioinformatic prediction of leader genes in human periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2008;79:1974–1983. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bragazzi N., Nicolini C. A Leader Genes Approach-based Tool for Molecular Genomics: From Gene-ranking to Gene-network Systems Biology and Biotargets Predictions. J. Comput. Sci. Syst. Biol. 2013;6:1760974. doi: 10.4172/jcsb.1000113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Lyon D., Junge A. STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acid. Res. 2019;47:607–613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim W.H., Liu B., Cheng D., Williams B.O. Wnt signalling regulates homeostasis of the periodontal ligament. J. Periodontal Res. 2014;49:751–759. doi: 10.1111/jre.12158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen H., Ji L., Liu X., Zhong J. Correlation between the rs7101 and rs1063169 polymorphisms in the FOS noncoding region and susceptibility to and prognosis of colorectal cancer. Med. Baltim. 2019;98:e16131. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kou Y., Zhang S., Chen X., Hu S. Gene expression profile analysis of colorectal cancer to investigate potential mechanisms using bioinformatics. Onco Targ. Ther. 2015;8:745–752. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S78974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song L., Yao J., He Z., Xu B. Genes related to inflammation and bone loss process in periodontitis suggested by bioinformatics methods. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:105. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0086-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu E., Mueller E., Oliviero S., Papaioannou V.E., Johnson R., Spiegelman B.M. Targeted disruption of the c-fos gene demonstrates c-fos-dependent and -independent pathways for gene expression stimulated by growth factors or oncogenes. EMBO J. 1994;13:3094–3103. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinberg B.A., Hartley M.L., Salem M.E. Precision Medicine in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Relevant Carcinogenic Pathways and Targets-PART 1: Biologic Therapies Targeting the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Oncol. Williston Park. 2017;31:539–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang H., Dong L., Gong F., Gu Y., Zhang H. Inflammatory genes are novel prognostic biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018;42:368–380. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pyrc K., Milewska A., Kantyka T., Sroka A., Maresz K. Inactivation of epidermal growth factor by Porphyromonasgingivalis as a potential mechanism for periodontal tissue damage. Infect. Immun. 2013;81:55–64. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00830-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng Q., Lei F., Chang Y., Gao Z. An oncogenic gene, SNRPA1, regulates PIK3R1, VEGFC, MKI67, CDK1 and other genes in colorectal cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;117:109076. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki A., Ji G., Numabe Y., Ishii K., Muramatsu M., Kamoi K. Large-scale investigation of genomic markers for severe periodontitis. Odontology. 2004;92:43–47. doi: 10.1007/s10266-004-0035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balkwill F. TNF-alpha in promotion and progression of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:409–416. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Da Silva M.K., de Carvalho A.C.G., Alves E.H.P., Silva F., Pessoa L., Vasconcelos D. Genetic Factors and the Risk of Periodontitis Development: Findings from a Systematic Review Composed of 13 Studies of Meta-Analysis with 71,531 Participants. Int. J. Dent. 2017;2017:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2017/1914073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hai Ping P., Feng Bo T., Li L., Hui Y.N., Hong Z. IL-1β/NF-kb signalling promotes colorectal cancer cell growth through miR-181a/PTEN axis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016;601:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkins L.M., Kaye E.K., Wang H.Y., Rogus J., Doucette-Stamm L. Influence of Obesity on Periodontitis Progression Is Conditional on Interleukin-1 Inflammatory Genetic Variation. J. Periodontol. 2017;88:59–68. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.160408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shamoun L., Skarstedt M., Andersson R.E., Wagsater D., Dimberg J. Association study on IL-4, IL-4Rα and IL-13 genetic polymorphisms in Swedish patients with colorectal cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2018;487:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan Y., Weng H., Shen Z.H., Wu L., Zeng X.T. Association between interleukin-4 gene -590 c/t, -33 c/t, and 70-base-pair polymorphisms and periodontitis susceptibility: A meta-analysis. J. Periodontol. 2014;85:354–362. doi: 10.1902/jop.2014.140317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Spirito F., Sbordone L., Pilone V., D’Ambrosio F. Obesity and periodontal disease: A narrative review on current evidence and putative molecular links. Open Dent. J. 2019;13:526–536. doi: 10.2174/1874210601913010526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu L.L., Yu H.G., Yu J.P., Luo H.S., Xu X.M. Nuclear factor—kB p65 (RelA) transcription factor is constitutively activated in human colorectal carcinoma tissue. World, J. Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3255–3260. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuchida S., Satoh M., Takiwaki M., Nomura F. Ubiquitination in Periodontal Disease: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1476. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jepsen S., Caton J.G., Albandar J.M., Bissada N.F., Bouchard P., Cortellini P., Demirel K., de Sancitis M., Ercoli C., Fan J., et al. Periodontal Manifestations of Systemic Diseases and Developmental and Acquired Conditions: Consensus Report of Workgroup 3 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018;89:237–248. doi: 10.1002/JPER.17-0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoon A.J., Cheng B., Philipone E., Turner R., Lamster I.B. Inflammatory Biomarkers in Saliva: Assessing the Strength of Association of Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Status with the Oral Inflammatory Burden. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012;39:434–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Germini D.E., Franco M.I.F., Fonseca F.L.A., de Sousa Gehrke F., da Costa Aguiar Alves Reis B., Cardili L., Oshima C.T.F., Theodoro T.R., Waisberg J. Association of expression of inflammatory response genes and DNA repair genes in colorectal carcinoma. Tumour. Biol. 2019;41 doi: 10.1177/1010428319843042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kojima M., Morisaki T., Sasaki N., Nakano K., Mibu R., Tanaka M., Katano M. Increased nuclear factor-kB activation in human colorectal carcinoma and its correlation with tumor progression. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:675–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lauritano D., Sbordone L., Nardone M., Iapichino A., Scapoli L., Carinci F. Focus on periodontal disease and colorectal carcinoma. Oral Implantol. 2017;10:229–233. doi: 10.11138/orl/2017.10.3.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu J.M., Shen C.J., Chou Y.C., Hung C.F., Tian Y.F. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with periodontal disease severity: A nationwide, population-based cohort study. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:349–352. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-2965-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor G.W., Borgnakke W.S. Periodontal Disease: Associations with Diabetes, Glycemic Control and Complications. Oral Dis. 2008;14:191–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chi Y.C., Chen J.L., Wang L.H., Chang K., Wu C.L. Increased risk of periodontitis among patients with Crohn’s disease: A population-based matched-cohort study. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:1437–1444. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glick M., Williams D.M., Kleinman D.V., Vujicic M., Watt R.G., Weyant R.J. A New Definition for Oral Health Developed by the FDI World Dental Federation Opens the Door to a Universal Definition of Oral Health. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017;151:229–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barros S.P., Williams R., Offenbacher S., Morelli T. Gingival Crevicular as a Source of Biomarkers for Periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000. 2016;70:53–64. doi: 10.1111/prd.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]