Abstract

Based on the data of the 2015 China General Social Survey (CGSS), this article empirically analyzed the influence of gender concept, work pressure, and work flexibility on work–family conflict (work interfering family (WIF) and family interfering work (FIW)) from three perspectives (gender, age, and urban and rural areas in China) and tested its significance. The empirical results show that individuals holding the concept of gender inequality produced lower WIF and FIW, which only exists between sexual relations, older working people, and urban and rural areas. Multicultural exchange and integration only made it easier for working people under the age of 30 to accept the concept of gender equality, but it increased their WIF and FIW. Second, with the development of the economy and society of China, the work pressure of workers is the most important factor causing WIF and FIW. Lastly, in order to cope with the pressure of employment and the cost of living, it is difficult to ease the conflict between work and family.

Keywords: work interfere family, family interfere work, gender concept, work pressure, dominance analysis

Work and family are the most important areas of life for adults. Work–family conflict refers to the incongruity between work and family life, and the role of conflict and stress caused by it. It may also reflect as the conflict between the time we put for family and work, or people feel the stress and anxiety from both work and family, or in the form of behavior that cannot conform to the expectation (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). Work–family conflict is mutual (Frone et al., 1992; Gutek et al., 1991), including work interfering family (WIF) and family interfering work (FIW). With the development of China’s social economy, the conflict between work and family has been increasingly intensified among adults. The conflict between work and family leads to obvious negative emotions of individuals, which will decrease the subjective well-being of adults (Yang, 2016). These negative emotions can cause family conflicts and reduce one’s work efficiency. The conflict between work and family is of two types, that is, WIF and FIW. In China, the traditional gender concepts held by individuals, the work pressure, and work flexibility faced by workers are important aspects that affect the conflict between work and family.

Chinese traditional gender cultural concepts have influenced economic and social development for thousands of years. Although in recent years China has been constantly communicating and integrating with the world culture, it cannot change people’s cognition of traditional gender concepts at different age levels. In China’s urban and rural areas, gender differences are more obvious (Yang, 2017). More families believe that men should engage in social work with higher status, while women’s duty is to take better care of the family (Zhang & Lin, 2014). From 1990 to 2019, the Chinese male labor participation rate was reduced by 9%, and the female labor participation rate is reduced to 13% (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2020). Despite the discrimination of men and women employment, women face a higher rate of work and family conflict than men. Thus, women likely quit the labor market and return to the family because of the Chinese traditional gender concept.

Work stress and flexibility can have an impact on work–family conflict. Work stress comes from two parts: on the one hand, individuals give themselves internal pressure to obtain more labor income and higher positions. Nevertheless, the employment situation in China and enterprises and organizations exert external pressure on individuals (Lin et al., 2015). If individuals fail to process this kind of work pressure, it will reduce their satisfaction with work and loyalty toward the company. In some cases, this kind of pressure will even be passed on to the family, resulting in family discord and conflicts between work and family (Wu et al., 2003). Working flexibility has an inconsistent effect on alleviating work–family conflict among Chinese working people. It also puts forward higher requirements for work flexibility, especially for the workers who need to take care of the children and the elderly; greater flexibility of the work will be more conducive to the fulfillment of their responsibility of taking care of the family. So once work flexibility is decreased, it may lead to the conflict between family and work. But this study is slightly different from it.

This article uses the 2015 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) microsurvey data, combined with personal characteristics and economic characteristics as control factors, explores gender, job stress, job flexibility on the relationship between work and family conflict from the perspective of gender differences, different age groups, and urban and rural areas. Dominance analysis was used to test the importance of gender concept, work pressure, and work flexibility on the work–family conflict.

From a global point of view, the issue of work–family conflict has been concerned by western scholars since the middle of the 20th century (Frone et al., 1992). With the development of the Chinese economy and society, the contradiction between work and family became prominent gradually (Zhang & Shi, 2019). The research on this issue in the context of China is short but developing rapidly.

Previous Chinese research studies mainly focused on the impact of individual characteristics, family characteristics, social support, and other aspects of the conflict between work and family. Personal and family characteristics mainly include age, profession, marital status, mental and physical health, family size, family income, and the age of the youngest child in the family (Song & Guo, 2016; Wang et al., 2012). Social support includes organizational support, management support, colleague support, family support, and spouse support (Chen & Yu, 2011; Li & Gao, 2011; Tian & Zhang, 2018). And the influence of conflict between work and family on satisfaction (Dou et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2017) and work performance (Tian & Qin, 2013; Zhao et al.,2019). In addition, there are some research studies that discussed the impact of gender perceptions, work stress, and work flexibility on work–family conflict.

The gender difference in the impact of gender concept on work–family conflict is not only the focus of western scholars but also the focus of Chinese studies. The gender concept varies based on the cultural background of the country, and the difference of traditional gender concepts will have the opposite impact on the conflict between individual work and family. Studies in Sweden and Israel, for example, have reported that gender equality makes individuals feel more intensely about work-family conflict (Grnlund, 2007; Somech & Drach-Zahavy, 2007). However, in the United States, the conclusion of this is the opposite (Davis, 2011). Under Chinese cultural background, the Chinese traditional gender concept is deeply ingrained, although the Chinese government advocates and promotes the idea of gender equality, and the female social status has been improved (Ren et al., 2019). But there are a lot of people who still have a transitional idea about recognizing the freedom of work to women and yet still require them to be responsible for families (Zhang & Shi, 2019). This has led some women to play the role of “householder” and “breadwinner” at the same time. In terms of undertaking housework, although the concept of gender equality prompts men to participate in more housework, women still spend far more time on housework than men under the same subjective and objective conditions (Yang et al., 2015). Therefore, the concept of gender equality may not only ease women’s troubles but also makes them bear the burden of work and family at the same time, which aggravates the contradiction between work and family for Chinese women (Wang et al., 2009).

Work stress and flexibility are the most important aspects that cause a contradiction between work and family. After summarizing this type of study, studies from Belgium, United States, Netherlands, South Korea, and other countries have a consistent conclusion that the great work pressure and less work flexibility will lead to greater work–family conflict (Allen et al., 2013; Han et al., 2015; Kelly & Tranby, 2011; Nomaguchi, 2012; Schooreel & Verbruggen, 2016; Tummers & Bronkhorst, 2014; Winslow, 2005). In China, work pressure and work flexibility not only affect the health and well-being of individuals but also affect the family’s decision-making. For example, young people are discouraged from having a second child due to work pressure and inflexibility (Zhang & Shi, 2019). As China’s employment pressure and structural employment conflict continue to escalate, the increasing work pressure of the younger generation has broken the balance between working families. At the same time, work inflexibility also gives some resistance to ease family conflicts (Jiang, 2015).

Methods

Survey and Data

This article uses the 2015 China General Social Survey (CGSS) microsurvey data to study the relationship between gender concepts, work pressure, and work–family conflict in the context of China. CGSS is the earliest national, comprehensive, and continuous academic investigation project in China. CGSS joined the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) in 2007 and participated in the development of the international comparative standard module for social surveys, which laid the data foundation for this study.1 Before 2015, the CGSS data survey also covered issues related to work–family conflict, using two questions to measure work–family conflict.2 In 2015, the ISSP survey module was included in the Chinese survey for the first time, and the original problems were combined into one problem to measure work–family conflict, which not only solved the problem of weight division of measurement variables and data response deviation but also improved the accuracy of response problems. Therefore, the CGSS data of 2015 is more representative. In this article, the data were strictly screened. On the basis of controlling the working age between 18 and 60 years, only samples answering gender concepts, work–family conflict, and work flexibility were retained, and 717 valid data were finally selected.3

Measures

WIF and FIW

According to the bidirectional characteristics of working families, this article selects WIF and FIW as the explained variables.4 The answer options were coded backward, which means the higher the score, the greater the work–family conflict.

Core Explanatory Variables

The core explanatory variables included gender perception, work stress, and work flexibility. Each core explanatory variable is measured by multiple survey questions.5 This article adopts a unified approach to process these three core explanatory variables. First, the results of the index options used to measure gender perceptions and work stress are reverse coded. The results of the first indicator option in the measurement of work flexibility are coded positively, and the results of the last two indicator options are reverse coded. Second, the method of principal component analysis is used to determine the principal component and principal component characteristic root and calculated the comprehensive score. Third, the final score was obtained by a weighted average. The higher the score, the more equal the gender concept, the greater the work pressure, and more flexibility in the work.

The male sample was assigned a value of 1, while the female sample was assigned a value of 2. It was reported that the mean value of the female sample’s gender concept was 0.7753, and the mean value of the male sample’s gender concept was 0.7123. Women were more willing to accept the concept of gender equality than men. According to different age structures, the mean values of age and gender in each group were 0.7880, 0.7763, 0.7390, and 0.6520, respectively, for 18–30 years, 31–40 years, 41–50 years, and 51–60 years group; the older the age, the less recognition of gender equality. The urban sample was assigned a value of 1, while the rural sample was assigned a value of 2. The mean values of urban and rural gender concepts were 0.7751 and 0.6674, respectively. Rural workers were more likely to hold the concept of gender inequality than urban workers.

The mean value of work stress of the male sample was 1.0797, and the mean value of work stress of the female sample was 1.0152, that is, men are taking more work stress than women. The mean values of the working pressure of the age group 18–30 years, 31–40 years, 41–50 years, and 51–60 years were 0.9900, 1.1296, 1.0289, and 1.0544, respectively. The mean values of the working pressure in rural and urban areas were 1.2065 and 0.9828, respectively.

Laborers think that the flexibility of work is generally low, with an average of 0.4990. The mean value of the work flexibility of the male sample was 0.5131 and that of the female sample was 0.4852. Men are subjectively more flexible than women. The average values of working flexibility of the age group 18–30 years, 31–40 years, 41–50 years, and 51–60 years were 0.4741, 0.4706, 0.5283, and 0.5246, respectively. Multiple factors, such as supporting a family, raising children, and taking care of parents, made workers of the age group 31–40 years believe that their working form is the least flexible. Rural and urban average work flexibility values are 0.4765 and 0.5546, respectively, with rural workers believing they were more flexible.

Control Variables

Some important control variables are also selected, including family characteristics and individual characteristics. Family characteristics include family income and family size. The higher the value is, the higher the family income and the larger the family size is. The average logarithm of family income reaches 10.126. The family size is basically 3–4 people.6 Five variables of individual characteristics were selected: age, education level, marital status, occupation, and self-rated health. The higher the value, the higher the education level, have spouse, job stability, and better self-rated health.7

Statistical Analysis

The average age is around 42, which is basically the median age. Sixty-six percent of the subjects had low-secondary education. The sample of male and female was balanced. Married workers made up 84% of the sample. More jobs[AU6: Please check the sentence beginning “ More jobs mean. . .”.] mean rated their health very highly. Table 1 reports a basic statistical description of all variables.

Table 1.

Statistical Description of All Variables.

| Variable | Sample size | Mean value | SD | Lowest value | Highest value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work interfere family | 717 | 2.226 | 0.949 | 1 | 5 |

| Family interfere work | 717 | 2.040 | 0.847 | 1 | 5 |

| Gender concept | 717 | 0.756 | 0.229 | 0.25 | 1.25 |

| Work pressure | 717 | 1.047 | 0.277 | 0.333 | 1.73 |

| Work flexibility | 717 | 0.499 | 0.211 | 0.224 | 1.208 |

| Family income | 717 | 10.126 | 2.988 | 0 | 14.221 |

| Family income squared | 717 | 111.446 | 37.263 | 0 | 202.236 |

| Family size | 717 | 1.244 | 0.878 | 0 | 8 |

| Age | 717 | 40.123 | 10.453 | 18 | 60 |

| Age squared | 717 | 1718.954 | 842.896 | 324 | 3600 |

| Education level | 717 | 2.130 | 0.726 | 1 | 3 |

| Marital status | 717 | 0.844 | 0.363 | 0 | 1 |

| Professions | 717 | 0.494 | 0.429 | 0 | 1 |

| Self-rated health level | 717 | 3.951 | 0.896 | 1 | 5 |

| Gender | 717 | 1.505 | 0.500 | 1 | 2 |

| Urban and rural | 717 | 1.287 | 0.452 | 1 | 2 |

Source. Data of 2015 Chinese General Social Survey.

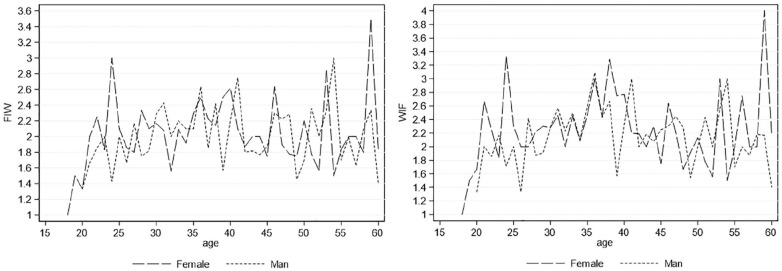

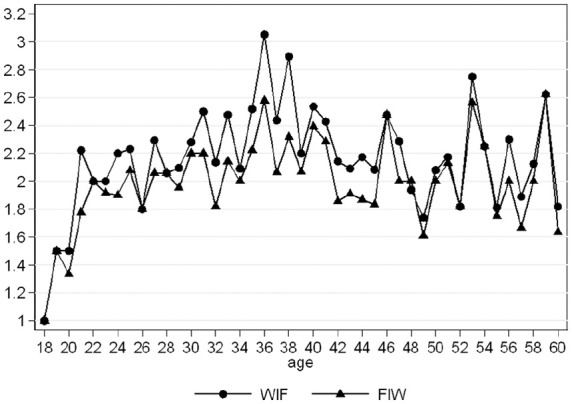

This article further discusses the overall sample, gender differences, urban and rural areas, the WIF value, and FIW value of the data of various age stages, which more intuitively reflects the changing trend of conflicting work and family at different ages. Figure 1 reports the changes in WIF and FIW of the whole sample of individuals of different ages. The WIF and FIW values of the working-age population of 18–52 in China have obvious inverted U-shaped characteristics. The WIF and FIW values of individuals aged 36–38 have reached the maximum, which is consistent with the actual situation in China. Many individuals at this age are in the stage of “there are elderly people in the family who need to be cared for and children who need to be fed.” Individuals need to work hard to obtain higher income and better promotion opportunities, and they also need more time to take care of their children and parents. Negative emotions brought about by work pressure will be transferred to families, and the pressure of family taking care of children and shoulder the pension will also be brought into the work (Ju, 2016), thus resulting in a high conflict between work and family. It is also noted that the WIF and FIW values of individuals at the age of 18 are extremely low. According to the Chinese higher education quality report released by the Chinese ministry of education, the gross enrolment rate of universities reached 40% in 2015 and will exceed to 50% in 2019 (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 2016). It can be seen that individuals at this age are more likely to be at school than at work and, therefore, experience relatively little conflict. In addition, for individual 52 to 58 years old, WIF and FIW values were higher, while the children as an adult, parents need to take into account the burden of the family with the lighter, but due to the “pay high price” for children to buy a house, Chinese traditional customs such as constraints, parents in their late years, the work pressure increase instead of a drop, it makes the conflict still in a high position.

Figure 1.

Work interfering family (WIF) and family interfering work (FIW) results at different ages.

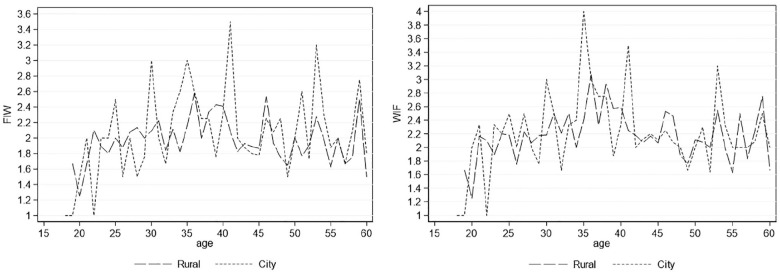

Figure 2 reports the results of WIF and FIW for men and women at different ages. From the different gender groups, it was identified that the WIF and FIW values of women were much higher than those of men at the age of 25 and 59, and they tended to the maximum values. The reason is that in their mid-20s when women are facing job searching or employment, many are already taking on the responsibility of raising children. In terms of taking care of children, women often spend more time and energy than men. In addition, the pressure from the mainstream values of taking care of both family and work will make it difficult for women to cope with such a situation, which will lead to greater conflicts between work and family for women. And the person at the age of 59 years, the family structure is commonly three generations together, influenced by Chinese traditional idea of family, grandparents taking care of grandchildren is very common (Cheng et al., 2017). Normally, grandmother spends far more time and energy on the grandchildren than grandfather (Gross, 2011), so this can make the women at this age take on more psychological distress and pressure from life, and therefore feel stronger in the conflict.

Figure 2.

Variation in the trends of family interfering work (FIW) and work interfering family (WIF) in men and women of different ages.

In addition, it can be seen from the urban–rural grouping in Figure 3 that the results of WIF and FIW in urban and rural areas in China are significantly different. The WIF and FIW values in cities vary greatly with age, and the two types of conflict are much higher in most age groups than in rural areas. WIF normally reaches its maximum at the age of 35, and the FIW normally reaches its maximum at the age of 40–42. This is consistent with China’s current situation and is closely related to China’s urbanization. The rural population came into cities, which increased the urban life pressure gradually, especially in the urban young people aged 18–34; they are facing greater life pressure, causing a greater conflict of family and work.

Figure 3.

Trends of work interfering family (WIF) and family interfering work (FIW) of individuals of different ages in rural and urban areas.

Analysis

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Analysis

This article uses OLS to analyze the relationship between gender concepts, work stress, and work–family conflict empirically. As presented in Tables 2 and 3, model (1)–model (3) are the empirical results of WIF in terms of gender, age, and urban–rural grouping. Column (4)–row (6) is listed as the empirical results of FIW under gender, age, and urban–rural grouping. The empirical results show the following main conclusions.

Table 2.

Ordinary Least Squares Regression Results of Work Interfering Family.

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | 18–30 age | 31–40 age | 41–50 age | 51–60 age | Urban | Rural | |

| Gender concept | 0.559** | 0.739*** | –0.302 | 0.803*** | 0.905*** | 1.061*** | 0.528*** | 0.858*** |

| (2.47) | (3.37) | (–0.99) | (2.80) | (3.30) | (2.69) | (3.07) | (2.68) | |

| Work pressure | 1.212*** | 1.331*** | 0.911*** | 1.806*** | 0.911*** | 1.046*** | 1.564*** | 0.754*** |

| (6.04) | (6.77) | (2.78) | (6.83) | (3.95) | (3.38) | (9.94) | (2.61) | |

| Work flexibility | –0.306 | 0.009 | 0.099 | 0.046 | 0.233 | –0.717** | 0.217 | –0.406 |

| (–1.30) | (0.04) | (0.24) | (0.13) | (0.87) | (–2.21) | (0.99) | (–1.56) | |

| Family income | 0.018 | 0.135* | 0.297*** | –0.032 | 0.102 | 0.053 | 0.093 | 0.145 |

| (0.24) | (1.93) | (3.13) | (–0.32) | (1.06) | (0.50) | (1.59) | (1.52) | |

| Family income squared | –0.000 | –0.011* | –0.025*** | 0.001 | –0.006 | –0.002 | –0.007 | –0.013 |

| (–0.09) | (–1.80) | (–3.11) | (0.17) | (–0.76) | (–0.27) | (–1.38) | (–1.63) | |

| Family size | –0.015 | –0.015 | –0.126 | 0.027 | 0.111 | –0.103 | 0.016 | –0.014 |

| (–0.23) | (–0.24) | (–1.50) | (0.25) | (1.12) | (–1.17) | (0.30) | (–0.16) | |

| Education level | 0.004 | 0.138 | –0.012 | 0.049 | –0.013 | –0.140 | 0.066 | –0.062 |

| (0.04) | (1.56) | (–0.09) | (0.38) | (–0.12) | (–0.95) | (0.95) | (–0.49) | |

| Marital status | 0.244* | 0.354** | 0.385*** | 0.127 | 0.033 | 0.420 | 0.285*** | 0.282 |

| (1.78) | (2.36) | (2.61) | (0.51) | (0.13) | (1.54) | (2.63) | (1.21) | |

| Professions | 0.106 | 0.137 | 0.127 | 0.272* | 0.097 | –0.228 | 0.238*** | –0.092 |

| (0.88) | (1.15) | (0.80) | (1.68) | (0.63) | (–0.98) | (2.61) | (–0.43) | |

| Self-rated health level | 0.006 | 0.021 | –0.117 | –0.075 | 0.097 | –0.008 | –0.022 | 0.067 |

| (0.11) | (0.36) | (–1.24) | (–0.98) | (1.32) | (–0.10) | (–0.48) | (0.95) | |

| N | 355 | 362 | 156 | 209 | 217 | 135 | 511 | 206 |

Note. The t value is in parenthesis. “*” represents significant at the 10% level; “**” represents significant at the 5% level; and “***” represents significant at the 1% level. The results of constant terms are not reported due to page reasons.

Table 3.

Ordinary Least Squares Regression Results of Family Interfering Work.

| (4) |

(5) |

(6) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | 18–30 age | 31–40 age | 41–50 age | 51–60 age | Urban | Rural | |

| Gender concept | 0.577*** | 0.372* | –0.261 | 0.743*** | 0.596** | 0.636* | 0.307** | 0.851*** |

| (2.79) | (1.89) | (–0.97) | (2.88) | (2.36) | (1.76) | (2.01) | (2.79) | |

| Work pressure | 0.769*** | 1.059*** | 0.434 | 1.325*** | 0.618*** | 0.921*** | 1.035*** | 0.705** |

| (4.18) | (6.03) | (1.52) | (5.56) | (2.90) | (3.25) | (7.37) | (2.56) | |

| Work flexibility | –0.039 | 0.362* | 0.448 | 0.432 | 0.666*** | –0.743** | 0.625*** | –0.250 |

| (–0.18) | (1.74) | (1.24) | (1.31) | (2.69) | (–2.51) | (3.20) | (–1.01) | |

| Family income | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.205** | –0.114 | 0.093 | –0.024 | 0.024 | 0.055 |

| (0.30) | (0.26) | (2.46) | (–1.28) | (1.05) | (–0.25) | (0.46) | (0.61) | |

| Family income squared | –0.001 | –0.002 | –0.017** | 0.007 | –0.007 | 0.003 | –0.002 | –0.005 |

| (–0.18) | (–0.29) | (–2.41) | (0.98) | (–0.90) | (0.40) | (–0.42) | (–0.65) | |

| Family size | –0.013 | –0.026 | –0.120 | 0.007 | 0.060 | –0.018 | –0.040 | 0.037 |

| (–0.20) | (–0.47) | (–1.63) | (0.07) | (0.65) | (–0.22) | (–0.85) | (0.44) | |

| Education level | –0.026 | 0.032 | –0.134 | –0.008 | –0.091 | –0.089 | –0.007 | –0.030 |

| (–0.34) | (0.41) | (–1.11) | (–0.06) | (–0.93) | (–0.66) | (–0.11) | (–0.25) | |

| Marital status | 0.338*** | 0.242* | 0.319** | 0.034 | 0.486** | 0.597** | 0.302*** | 0.261 |

| (2.69) | (1.81) | (2.47) | (0.15) | (2.15) | (2.39) | (3.12) | (1.18) | |

| Professions | –0.006 | –0.016 | –0.035 | 0.032 | 0.110 | –0.262 | 0.044 | 0.041 |

| (–0.06) | (–0.15) | (–0.25) | (0.22) | (0.77) | (–1.24) | (0.55) | (0.20) | |

| Self-rated health level | –0.081* | –0.024 | –0.173** | –0.098 | –0.010 | –0.108 | –0.061 | –0.051 |

| (–1.71) | (–0.45) | (–2.10) | (–1.43) | (–0.14) | (–1.49) | (–1.52) | (–0.76) | |

| N | 355 | 362 | 156 | 209 | 217 | 135 | 511 | 206 |

Note. The t value is in parenthesis. “*” represents significant at the 10% level; “**” represents significant at the 5% level; and “***” represents significant at the 1% level. The results of constant terms are not reported due to page reasons.

The stronger the idea of gender equality, the greater the conflict between work and family. The empirical results of gender grouping show that people who hold gender equality are more eager to be recognized in work and family. Once they cannot obtain the satisfaction of work and family at the same time, they often have more troubles and stress, which increases the conflict between personal work and family. The traditional gender concept in China emphasizes that “men should be the main breadwinner and women should be the one taking care of the family,” that is, men should pay more attention to work and women should pay more attention to family. With the change of the concept of gender, women are more likely to seek recognition in the field of work than men. In addition, gender discrimination tends to occur against women in the field of work, so women need to spend more time and energy to prove themselves (Cheng & He, 2016). Nevertheless, men are more likely to expect family approval. Therefore, the more equal the gender concept is, men feel more FIW than women, and women have a higher level of WIF than men.

The empirical results of age groups show that the elderly are deeply influenced by traditional gender concepts. In the age groups of 31–40 years, 41–50 years, and 51–60 years, the more equal gender concepts caused a stronger conflict between WIF and FIW, and the regression coefficient also reflects this feature. For young people aged 18–30, gender equality awareness and education have greatly shaken their traditional gender concepts (Gu, 2018). The awareness of gender equality is generally accepted by the new generation. If they tend to position their roles and responsibilities in a single field, they will find it difficult to adapt to the increasing demands on their time and energy in another field (Zhang & Shi, 2019). So at this age, the more traditional the gender beliefs you hold, the greater the conflict between work and family.

The empirical results of urban and rural subgroups show that there are a large number of Chinese urban and rural residents aged between 18 and 60 who hold the concept of gender inequality. Overall, gender inequality will still ease the conflict between WIF and FIW. However, the speed of economic development and cultural integration in urban areas is much faster than that in rural areas. Comparatively speaking, residents in urban areas are more likely to accept the concept of gender equality, and so the impact of gender inequality on WIF and FIW in urban areas is lower than that in rural areas.

Work pressure is an important factor affecting WIF and FIW. The higher the work pressure is, the higher the WIF and FIW values. From the empirical results of gender division, we identified that work and family conflict of women is higher than men. Although the government has helped some women to find jobs, China’s overall structural unemployment problem is still prominent. In particular, the number of women employed in knowledge-intensive high-tech industries is far lower than that of men, and women are excessively engaged in traditional labor-intensive industries. Most women struggle to balance the conflict between work and family when they are facing physical, psychological pressure, and the pressure of work hours. Therefore, women’s work pressure has a greater impact on WIF and FIW than men (Xu & Qi, 2016).

The people who feel the most work pressure are mainly from the age group of 31–40. At this age, the workers are taking more responsibilities for supporting the elderly and raising children and hence feel more work pressure subjectively. Therefore, the work pressure in this age group has the highest impact on WIF and FIW, which is consistent with the previous analysis.

In urban and rural groups, the work pressure has a significant effect on WIF and FIW. The urban life makes the work pace faster, and the urban workers feel more work pressure subjectively, which has a greater impact on WIF and FIW in urban areas than in rural areas. Thus, it can be seen that personal subjective feelings, the high-pressure employment environment in China, and the work pressure brought by the incentive at the enterprise level have played an important role in the conflict between work and family.

Another important conclusion of this study is that the effects of work flexibility on WIF and FIW of the working-age population are significantly different in terms of gender, age, and urban–rural conditions. The more flexible the work is, the more beneficial it is for men to ease and balance the conflict between work and family. However, even with the increase in job flexibility, women still face more conflict between work and family, which shows that family is still the focus of women.

The empirical results of different age groups show that the increased flexibility of the work has little significance in easing the effect of WIF and FIW. This is contrary to the previous description and reflects the change in the conflicting effects of work flexibility on work and family in the context of China’s current economic and social development. Only for workers aged 51–60, the more flexible the work is, the less conflict between work and family, but this age group is about to retire and does not have a greater demand for promotion. However, workers aged 18–30, 31–40, and 41–50 are more motivated to pursue work identity, in order to increase their income and obtain higher status in the company and for other personal purposes, such as a mortgage, education expenditure for children, and medical expenditure for parents. This is an important characteristic obtained in this study.

At last, China’s working-age population in urban areas seeks a better quality of life than in rural areas. As a result, the cost of living of the working-age population in China’s urban areas is also under great pressure (Fan & Zhou, 2018). Even with high job flexibility, the pressure of living in the city will force them to seek more part-time jobs in their spare time to make up for the cost of living. So having job flexibility does not reduce the conflict between work and family. In rural areas of China, agriculture is still the main mode of production, and the work form is relatively flexible, which will reduce the conflict between work and family essentially.

Dominance Analysis

Based on the OLS analysis, this article focuses more on the relative importance of gender perception, work pressure, and work flexibility to WIF and FIW among all variables and adopts the dominance analysis method proposed by Budescu and David (1993) as a robustness test to verify the accuracy of the above empirical results. Dominance analysis allows us to separate each explanatory variable’s contribution to R2 of the whole model or adjustment to R2, allowing us to compare the relative importance (RI) of each variable. Based on gender differences, age groups, and urban–rural areas, the RI of all variables was analyzed. The result obtained from the analysis after standardization is the sum of the contributions of all explanatory variables which is equal to 1.

The following conclusions can be drawn from the RI analysis. Based on gender differences (Table 4), first, gender perception is an important explanatory variable of WIF and FIW. No matter for male or female, the interpretation of gender concept to WIF is strong. But the interpretation of gender concept for male FIW is stronger than that of the female. Second, work pressure is the first explanatory factor affecting WIF and FIW under gender difference, and the contribution to interpretation R2 is the highest, reaching up to 73.49%. Third, the work flexibility of females has a stronger interpretation for FIW, and work flexibility of males has a stronger interpretation for WIF. But overall, work flexibility was only the main explanatory factor for male WIF and female FIW. Finally, in addition to the traditional concept of gender, the Chinese family structure also plays an important role in WIF and FIW.

Table 4.

Results of Relative Importance at Different Gender.

| Work interfering family |

Family interfering work |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Gender concept | 10.30%(2) | 13.22% (2) | 16.53% (3) | 3.68% (5) |

| Work pressure | 73.49% (1) | 66.59% (1) | 48.75% (1) | 70.96% (1) |

| Work flexibility | 1.85% (5) | 0.45% (10) | 0.76% (9) | 8.72% (2) |

| Family income | 1.07% (8) | 3.70% (4) | 1.00% (8) | 0.49% (9) |

| Family income squared | 1.24% (6) | 2.77% (6) | 1.35% (7) | 0.65% (8) |

| Family size | 0.72% (9) | 0.48% (9) | 1.99% (6) | 1.30% (7) |

| Education level | 3.09% (4) | 2.91% (5) | 4.18% (5) | 4.36% (4) |

| Marital status | 6.90% (3) | 6.41% (3) | 18.62% (2) | 6.03% (3) |

| Professions | 1.20% (7) | 2.27% (7) | 0.76% (10) | 0.35% (10) |

| Self-rated health level | 0.14% (10) | 1.21% (8) | 6.06% (4) | 3.45% (6) |

Based on different age groups (Table 5), first, the influence of gender concept on WIF and FIW in the 18–30 age group is very small, accounting for only about 3%. In contrast, in the age range of 30–60 years, the gender concept plays a significant role in the influence of WIF, contributing 23.81% to R2 at the highest. Second, in all age groups, work stress was still the most important factor in the generation of WIF and FIW, contributing the most to the interpretation of R2 which is up to 77.47%. The interpretation of work stress on WIF and FIW is far greater than other explanatory variables. Third, the importance of work flexibility for WIF and FIW in different age groups is significantly different, and work flexibility is more important for WIF and FIW in older workers, which is consistent with the empirical analysis results. There is no general conclusion about the importance of the remaining factors for WIF and FIW by age group.

Table 5.

Results of Relative Importance at Different Age.

| Work interfering family | Family interfering work | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–30 age | 31–40 age | 41–50 age | 51–60 age | 18–30 age | 31–40 age | 41–50 age | 51–60 age | |

| Gender concept | 2.58% (8) | 11.15% (2) | 23.81% (2) | 20.26% (2) | 3.12% (10) | 14.11% (2) | 8.57% (4) | 6.96% (5) |

| Work pressure | 37.26% (1) | 77.47% (1) | 48.36% (1) | 43.62% (1) | 22.34% (1) | 62.99% (1) | 33.95% (1) | 37.69% (1) |

| Work flexibility | 0.17% (10) | 0.64% (10) | 5.39% (5) | 14.70% (3) | 5.55% (7) | 6.87% (3) | 26.74% (2) | 18.11% (2) |

| Family income | 14.95% (3) | 0.81% (7) | 5.54% (4) | 1.42% (8) | 10.17% (5) | 3.84% (5) | 2.85% (7) | 0.64% (9) |

| Family income squared | 14.91% (4) | 0.88% (6) | 3.64% (6) | 1.72% (7) | 9.74% (6) | 2.99% (6) | 2.08% (8) | 1.15% (8) |

| Family size | 3.77% (7) | 0.64% (9) | 6.54% (3) | 2.54% (6) | 3.63% (8) | 0.85% (8) | 6.00% (6) | 0.50% (10) |

| Education level | 4.76% (5) | 1.64% (5) | 2.80% (8) | 7.87% (4) | 12.74% (3) | 2.18% (7) | 8.26% (5) | 6.21% (6) |

| Marital status | 16.67% (2) | 0.75% (8) | 0.10% (10) | 5.70% (5) | 17.72% (2) | 0.34% (10) | 10.07% (3) | 16.68% (3) |

| Professions | 0.99% (9) | 3.52% (3) | 0.71% (9) | 1.41% (9) | 3.23% (9) | 0.65% (9) | 0.76% (9) | 3.06% (7) |

| Self-rated health level | 3.94% (6) | 2.50% (4) | 3.11% (7) | 0.76% (10) | 11.76% (4) | 5.18% (4) | 0.74% (10) | 9.00% (4) |

Based on the urban and rural conditions (Table 6), first, the influence of gender concept has a great interpretation on urban and rural WIF, while gender concept has a stronger explanatory ability on rural FIW than on urban. Second, work pressure is still the primary factor affecting the WIF and FIW of workers in urban areas. But in rural areas, the explanatory ability of gender concepts for WIF and FIW exceeds the work pressure. Third, work flexibility has less ability to explain WIF for urban workers, but work flexibility has become the main factor of FIW for urban workers. In rural areas, the situation is the opposite.

Table 6.

Results of Relative Importance at Urban–Rural Areas.

| Work interfering family |

Family interfering work |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | |

| Gender concept | 5.74% (2) | 31.73% (1) | 2.58% (6) | 35.53% (1) |

| Work pressure | 76.96% (1) | 31.20% (2) | 63.35% (1) | 34.92% (2) |

| Work flexibility | 1.35% (8) | 9.05% (3) | 13.61% (2) | 3.81% (6) |

| Family income | 2.33% (5) | 5.75% (6) | 0.64% (10) | 1.49% (9) |

| Family income squared | 1.68% (7) | 8.39% (4) | 0.70% (9) | 2.39% (8) |

| Family size | 0.59% (10) | 0.73% (9) | 0.99% (7) | 4.78% (5) |

| Education level | 1.78% (6) | 3.50% (7) | 3.64% (4) | 3.15% (7) |

| Marital status | 5.52% (3) | 6.04% (5) | 10.19% (3) | 7.84% (3) |

| Professions | 3.21% (4) | 0.56% (10) | 0.83% (8) | 0.89% (10) |

| Self-rated health level | 0.85% (9) | 3.05% (8) | 3.47% (5) | 5.21% (4) |

Discussion

Based on the background of Chinese culture, this article used CGSS data to test the relationship between gender, work pressure, work flexibility, and WIF and FIW from the perspectives of gender difference, different age groups, and urban and rural areas. The importance of gender perception, work pressure, and work flexibility to WIF and FIW was analyzed through RI analysis. The main conclusions are as follows.

First, the people holding the concept of gender equality will receive stronger conflict between work and family. Women experience higher levels of WIF than men, and men experience higher levels of FIW than women. The concept of gender equality only affects workers born after 1985 (age 30), but it is difficult to change the older workers’ cognition of traditional gender concepts. Thus, the role of WIF and FIW in reducing older Chinese workers through gender equality is very limited. In particular, the development of multicultural communication in China’s rural areas is slow, and the gender equality concept has a stronger interference on WIF and FIW of rural laborers.

Second, with the development of China’s economy and society, work pressure has gradually become the most important factor affecting the WIF and FIW of workers. Work pressure has brought challenges to the balance between work and family. At present, China’s severe employment situation, different organizational atmosphere and styles of enterprises, and strict requirements of individuals on themselves put great work pressure on individuals, which leads to strong conflicts between work and family.

Third, work flexibility does not play a significant role in alleviating WIF and FIW. In particular, even with more flexible work arrangements, WIF and FIW for women, WIF for those aged 18–50, FIW for those aged 18–40, and WIF and FIW for urban workers were not reduced. A series of purposes, such as the cost of living, payment of loans, and obtaining a higher position, make the workers need to pay more efforts in their work. Whether the working form is flexible or not is still not the main consideration for the current workers in employment and dimission.

Finally, through the analysis of relative importance, the differences in gender concepts and the degree of work pressure are the most important factors that cause WIF and FIW in Chinese workers. Under different conditions, the importance of work flexibility to WIF and FIW also has significant differences, which is consistent with the conclusion of empirical analysis.

Limitations

It is true that there are differences in the economic and social development of China’s 31 provinces, and the differences in living conditions and economic foundations between urban and rural areas are more obvious. However, due to the problem of data samples, it is hard to distinguish the influence of gender concepts and work pressure on WIF and FIW in different regions in detail. At the same time, because the modern Chinese people hold the concept that “males should be engaged in work and female should take care of the family,” women will face more employment discrimination and receive low support from the family. Gender concepts, work pressure, and work–family conflicts have different impacts on the well-being of men and women. Although personal health can affect WIF and FIW, the results are not significant. It is difficult to establish a reverse causality between them.

Conclusion

Gender concepts and work pressure have a crucial impact on the WIF and FIW of Chinese workers. Gender concepts and work pressure have different effects on WIF and FIW of individuals of different genders, urban and rural areas, and different ages, and each has its own characteristics. By reducing the work pressure of workers in the enterprise, the conflict between work and family can be effectively reduced. The change in gender concepts from tradition to equality may have a relatively limited effect on reducing the work–family conflicts of Chinese people and to a certain extent may also enhance and consolidate the concepts of gender equality among Chinese people. Although the well-being of individuals is more conducive to relieving WIF and FIW, it is difficult to distinguish the difference between the negative effects of work and family conflicts on the well-being of men and women.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Chen Shi, studying at Villanova University, for correcting the grammar in this paper.

ISSP is a multinational collaborative research project to promote the standardization and internationalization of social science research and to establish a shared social science database. Currently, the project involves 48 countries or regions around the world. The project has set up a special sub-database of “family gender role change,” which includes family values, gender concepts, gender division of labor, and other contents.

Use measures like “I’m tired when I get home from work and can’t do the chores that need to be done” and “I spend most of my time at work and have a hard time fulfilling my family responsibilities.” Use measures like “I can’t do my job well because I’m tired of doing housework” and “I have a hard time focusing on work because of my family responsibilities.”

In the study of Chinese gender concepts, working pressure and the process of work–family conflict, work characteristics of the selected variables and work–family conflict belongs to the CGSS database D module; D module is adopted by the multistage stratified probability proportionate to size (PPS); the module does not require all respondents answered, only need to answer, according to 1/6 of the sampling probability.

WIF: “Do the following things happen a lot at work? (1) your work interferes with family life”; FIW: “do the following things happen a lot at work? (2) your family life gets in the way of your work.” Answer options include always/often/sometimes/almost/never/can’t answer. The “unable to answer” option is deleted from the data, and the value of each question option is 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively.

By four questions to measure gender notions: “Do you agree with the following: (1) A man should focus on career and women should focus on family; (2) the ability of men born better than women; (3) women marry a good husband is better than good at one’s work; (4) during the economic recession, should first fire female employees,” answer options include not agree/not agree/doesn’t matter/agree/completely agree/cannot answer. The “unable to answer” option is deleted from the data, and the value of each question option is 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 in turn. Measure work stress by asking three questions: “How often do the following things happen at work? (1) doing heavy physical work; (2) feeling stressed out at work; and (3) working on weekends.” The “unable to answer” option is deleted from the data, and the value of each question option is 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 in turn. Work flexibility is measured by three questions: (1) “Which of the following best fits your work schedule?” The answer options include: my work hours are regulated by my company, I can’t decide by myself/within certain limits, I am free to decide when I go to work and when I leave work. (2) “Which of the following best fits into your daily work routine?” The answer options include: I am free to decide how to arrange my daily work/within certain limits, I can decide how to arrange my daily work/I don’t have the freedom to decide what I want to do every day. (3) “Is working from home during normal working hours a common occurrence in your job?”Answer options include: always/often/sometimes/hardly/never/unanswerable. The values to the options in question (1) are 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The values to the options (2) and (3) are 3, 2, 1, and 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, respectively.

(1) How much is your total family income in 2014? and (2) How many children do you have?

(1) How old are you?; (2) What is your highest education level so far?; (3) What is your current marital status? (4) Does your current job have a written labor contract with your employer or employer? and (5) What do you think of your current state of physical health? Among them, the education level is divided into three levels, which had no education; literacy class/school/junior high school is divided into low education level and the assignment is 1; ordinary high school/secondary vocational high school/technical school/college (adult higher education college/university) was divided into secondary education (regular higher education level and the assignment of 2); university degree (adult higher education)/university (formal higher education)/graduate and above is divided into higher education level and the value of 3; unmarried/separated but undivorced/divorced/widowed were classified as spouseless assisted families with a value of 0; cohabitation/first marriage spouse/remarried spouse were classified as spouse-assisted families with a value of 1. Assign a value of 0 to the labor contract not signed, a value of 1 to the labor contract signed with or without a fixed term, and a value of 1 to the labor contract signed with a fixed term. Health status options include very unhealthy/relatively unhealthy/average/relatively healthy/very healthy, with values of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, in order.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this project was provided by the National Social Science Fund: Demographic structure transformation, pension parameter adjustment and fair economic growth in China (17BJL097).

ORCID iD: H. M. Wang  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9290-7536

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9290-7536

References

- Allen T. D., Johnson R. C., Kiburz K. M., Shockley K. M. (2013). Work-family conflict and flexible work arrangements: Deconstructing flexibility. Personnel Psychology, 66(2), 345–376. [Google Scholar]

- Budescu D. V., David V. (1993). Dominance analysis: A new approach to the problem of relative importance of predictors in multiple regression. Psychological Bulletin, 114(3), 542–551. [Google Scholar]

- Chen F. Y., Yu W. (2011). Research on supervisor support to work-family conflict and job performance for frontline employees in hotel industry(in Chinese). Tourism Forum, 4(6), 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y. X., He Q. (2016). Women’s fertility desire and female rights protection under the background of universal two-child policy(in Chinese). Journal of China Institute of Industrial Relations, 30(4), 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z. W., Ye X. J. Z., Chen G. (2017). Association between grandparenting, living arrangements and depressive symptoms among middle: Aged and older Adults(in Chinese). Population and Development, 23(2), 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Davis S. N. (2011). Support, demands, and gender ideology: Exploring work-family facilitation and work-family conflict among older workers. Marriage & Family Review, 47(6), 363–382. [Google Scholar]

- Dou J. F., Zhang M., Qiao Y. B., Yang B. Y. (2017). Moderation effect of work-family centrality on relationship between work-family conflict and satisfaction for male managers(in Chinese). Technology Economics, 36(1), 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fan M., Zhou W. T. (2018). Factors causing overwork and the estimation of their contributions: Based on the method of dependent variable variance decomposition(in Chinese). Journal of China University of Labor Relations, 32(2), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Frone M. R., Russell M., Cooper M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus J. H., Beutell N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Grnlund A. (2007). More control, less conflict? Job demand-control, gender and work -family conflict. Gender Work and Organization, 14(5), 476–497. [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J. (2011). Handbook of emotion regulation(in Chinese). Shanghai People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Gu H. (2018). Women’s social status inconsistency in contemporary society and the revelation (in Chinese). Contemporary Youth Research, 3, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gutek B. A., Searle S., Klepa L. (1991). Rational versus gender role explanations for work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(4), 560–568. [Google Scholar]

- Han S. S., Han J. W., Choi E. H. (2015). Effects of nurses’ job stress and work-family conflict on turnover intention: Focused on the mediating effect of coping strategies. Asian Women, 31(3), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Jia Y., Tao J. (2017). Impact of abusive supervision on work-family conflict and family satisfaction of employees: The effect of emotional intelligence(in Chinese). Collected Essays on Finance and Economics, 4, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. (2020). Labor force participation rate, male and female. https://data.worldbank.org.cn/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.MA.ZS?end=2019&locations=CN&start=1990&view=chart

- Jiang H. Y., Yang J., Sun P. Z., Chen Y. (2018). Effect of job resources on employees’ turnover intention: The mediating role of work-family conflict and moderating role of proactive personality(in Chinese). Soft Science, 32(10), 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J. J. (2015). Gender difference and influence factors of work-family balance(in Chinese). Zhejiang Academic Journal, 3, 2019–2224. [Google Scholar]

- Ju L. (2016). Abusive supervision and work-family conflict: A moderated mediation model(in Chinese). Jinan Journal (Philosophy & Social Science Edition), 38(6), 52–63+130. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly E. L., Tranby M. E. (2011). Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: Schedule control in a white-collar organization. American Sociological Review, 76(2), 265–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Y., Gao J. (2011). An empirical study based on middle professional manager: The relations among work-family conflict, perceived supervisory support and job satisfaction(in Chinese). Science of Science and Management of S.& T., 32(2), 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. M., Liu H., Wang S. Y. (2015). Relationship between work boundary strength and employee’s work stress: Based on person-environment fit theory (in Chinese). China Industrial Economics, 3, 122–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Hu X. M., Huang X. L., Zhuang X. D., Hao Y. T. (2017). The relationship between job satisfaction, work stress, work-family conflict, and turnover intention among physicians in Guangdong, China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 7(5), e014894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2016). Higher education quality report: China’s gross enrollment rate of higher education has reached 40%, higher than the global average level [Press release]. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/xw_fbh/moe_2069/xwfbh_2016n/xwfb_160407/160407_mtbd/201604/t20160408_237163.html

- Nomaguchi K. M. (2012). Marital status, gender, and home-to-job conflict among employed parents. Journal of Family Issues, 33(3), 271–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z. P., Xiong C., Zhou Z. (2019). China fertility report 2019 (in Chinese). Development Research, 6, 20–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schooreel T., Verbruggen M. (2016). Use of family-friendly work arrangements and work-family conflict: Crossover effects in dual-earner couples. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(1), 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somech A., Drach-Zahavy A. (2007). Strategies for coping with work-family conflict: The distinctive relationships of gender role ideology. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(1), 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song P., Guo G. M. (2016). Relationship between work-family conflict and subjective well-being on new generation of migrant workers(in Chinese). Journal of Northwest A&F University (Social Science Edition), 16(1), 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Qin J. (2013). Entrepreneurship-family conflict and the initial performance of Nascent Entrepreneur (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Management, 10(6), 853–861. [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Zhang Y. L. (2018). Work-family conflict in an entrepreneurship context: A role transition perspective (in Chinese). Journal of Management Sciences in China, 21(5), 90–110. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers L. G., Bronkhorst B. A. C. (2014). The impact of leader-member exchange (lmx) on work-family interference and work-family facilitation. Personnel Review, 43(4), 573–591. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. F., Jia S. H., Li S. X. (2009). The mediating effect between gender and work-family conflict (in Chinese). Journal of Psychological Science, 32(5), 1221–1223+1227. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Liu L., Wang J., Wang L. (2012). Work-family conflict and burnout among Chinese doctors: The mediating role of psychological capital. Journal of Occupational Health, 54(3), 232–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow S. (2005). Work-family conflict, gender, and parenthood, 1977–1997. Journal of Family Issues, 26(6), 727–755. [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. L., Feng Y., Fan W. (2003). The stressors in professional women’s work-family conflict (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 1, 43–46+56. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Qi J. J. (2016). Work-family conflict, gender role, and job satisfaction: An analysis of the phase Ⅲ Chinese women social status survey(in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Sociology, 36(3), 192–215. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. H. (2016). Improve child care services to promote women’s work and family balance (in Chinese). Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies, 2, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. H. (2017). The continuation and changes of chinese gender concepts in the past 20 years (in Chinese). Shandong Social Sciences, 11, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. H., Zhang J. J., Wu M. (2015). Gender differences in study time: China 1990–2010 (in Chinese). Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies, 6, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. N., Shi H. J. (2019). Gender ideology, gender inequality context and gender gap in work-family conflict: Evidence from international social survey programme(in Chinese). Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies, 3, 26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. X., Lin D. S. (2014). Gender disparities between income and rate of return to education of migrant workers (in Chinese). Peking University Education Review, 12(3), 121–140+192. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F. Q., Chen Y., Hu W. (2019). Research on impact of WFB-HRP on job performance in Chinese context: Effect of family-work facilitation & psychological capital (in Chinese). Nankai Business Review, 22(6), 165–175. [Google Scholar]