Abstract

Background

Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine have been proposed as treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) on the basis of in vitro activity and data from uncontrolled studies and small, randomized trials.

Methods

In this randomized, controlled, open-label platform trial comparing a range of possible treatments with usual care in patients hospitalized with Covid-19, we randomly assigned 1561 patients to receive hydroxychloroquine and 3155 to receive usual care. The primary outcome was 28-day mortality.

Results

The enrollment of patients in the hydroxychloroquine group was closed on June 5, 2020, after an interim analysis determined that there was a lack of efficacy. Death within 28 days occurred in 421 patients (27.0%) in the hydroxychloroquine group and in 790 (25.0%) in the usual-care group (rate ratio, 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.97 to 1.23; P=0.15). Consistent results were seen in all prespecified subgroups of patients. The results suggest that patients in the hydroxychloroquine group were less likely to be discharged from the hospital alive within 28 days than those in the usual-care group (59.6% vs. 62.9%; rate ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83 to 0.98). Among the patients who were not undergoing mechanical ventilation at baseline, those in the hydroxychloroquine group had a higher frequency of invasive mechanical ventilation or death (30.7% vs. 26.9%; risk ratio, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.27). There was a small numerical excess of cardiac deaths (0.4 percentage points) but no difference in the incidence of new major cardiac arrhythmia among the patients who received hydroxychloroquine.

Conclusions

Among patients hospitalized with Covid-19, those who received hydroxychloroquine did not have a lower incidence of death at 28 days than those who received usual care. (Funded by UK Research and Innovation and National Institute for Health Research and others; RECOVERY ISRCTN number, ISRCTN50189673; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04381936.)

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19), emerged in China in late 2019 from a zoonotic source.1 The majority of Covid-19 infections are either asymptomatic or result in only mild disease. However, in a substantial proportion of infected persons, the infection leads to a respiratory illness requiring hospital care,2 which can progress to critical illness with hypoxemic respiratory failure and lead to prolonged ventilatory support.3-6 Among the patients with Covid-19 who have been admitted to hospitals in the United Kingdom, the case fatality rate is approximately 30%.7

Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, two 4-aminoquinoline drugs that were developed more than 70 years ago and have been used to treat malaria and rheumatologic conditions, have been proposed as treatments for Covid-19. Chloroquine has been shown to have in vitro activity against a variety of viruses, including SARS-CoV-2 and the related SARS-CoV-1.8-13 The exact mechanism of antiviral action is uncertain, but these drugs increase the pH of endosomes that the virus uses for cell entry and also interfere with the glycosylation of angiotensin-converting–enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is the cellular receptor of SARS-CoV, and of associated gangliosides.10,14 The 4-aminoquinoline levels that are required to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro are higher than the free plasma levels that have been observed in the prevention and treatment of malaria.15 These drugs generally have an acceptable side-effect profile and are inexpensive and widely available. After oral administration, they are rapidly absorbed, even in severely ill patients. Therapeutic hydroxychloroquine levels could be expected to be reached in human lung tissue shortly after an initial loading dose.

In small preclinical studies of SARS-CoV-2 infection in animals, prophylaxis or treatment with hydroxychloroquine had no beneficial effect on clinical disease or viral replication.16 A clinical benefit and an antiviral effect from the administration of these drugs alone or in combination with azithromycin in patients with Covid-19 have been reported in some observational studies17-21 but not in others.22-24 The results of a few small trials of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for the treatment of Covid-19 have been inconclusive, whereas one larger randomized, controlled trial involving patients who were hospitalized with mild-to-moderate Covid-19 showed that hydroxychloroquine (at a dose of 400 mg twice daily, with or without azithromycin) did not improve clinical status at day 15, as compared with usual care.25-29 Here, as part of the controlled, open-label Randomized Evaluation of Covid-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, we report the results of a comparison between hydroxychloroquine and usual care involving patients hospitalized with Covid-19.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

The RECOVERY trial is an investigator-initiated platform trial to evaluate the effects of potential treatments in patients hospitalized with Covid-19. The trial is being conducted at 176 hospitals in the United Kingdom. (Details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.) The investigators were assisted by the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network, and the trial is coordinated by the Nuffield Department of Population Health at the University of Oxford, the trial sponsor. Although patients are no longer being enrolled in the hydroxychloroquine, dexamethasone, and lopinavir–ritonavir groups, the trial continues to study the effects of azithromycin, tocilizumab, convalescent plasma, and REGN-COV2 (a combination of two monoclonal antibodies directed against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein). Other treatments may be studied in the future. The hydroxychloroquine that was used in this phase of the trial was supplied by the U.K. National Health Service (NHS).

Hospitalized patients were eligible for the trial if they had clinically-suspected or laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and no medical history that might, in the opinion of the attending clinician, put patients at substantial risk if they were to participate in the trial. Initially, recruitment was limited to patients who were at least 18 years of age, but the age limit was removed as of May 9, 2020.

Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients or from a legal representative if they were too unwell or unable to provide consent. The trial was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation and was approved by the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the Cambridge East Research Ethics Committee. The protocol with its statistical analysis plan are available at NEJM.org, with additional information in the Supplementary Appendix and on the trial website at www.recoverytrial.net.

The initial version of the manuscript was drafted by the first and last authors, developed by the writing committee, and approved by all members of the trial steering committee. The funders had no role in the analysis of the data, in the preparation or approval of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The first and last members of the writing committee vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol and statistical analysis plan.

Randomization and Treatment

We collected baseline data using a Web-based case-report form that included demographic data, level of respiratory support, major coexisting illnesses, the suitability of the trial treatment for a particular patient, and treatment availability at the trial site. Using a Web-based unstratified randomization method with the concealment of trial group, we assigned patients to receive either the usual standard of care or the usual standard of care plus hydroxychloroquine or one of the other available treatments that were being evaluated. The number of patients who were assigned to receive usual care was twice the number who were assigned to any of the active treatments for which the patient was eligible (e.g., 2:1 ratio in favor of usual care if the patient was eligible for only one active treatment group, 2:1:1 if the patient was eligible for two active treatments, etc.).

For some patients, hydroxychloroquine was unavailable at the hospital at the time of enrollment or was considered by the managing physician to be either definitely indicated or definitely contraindicated. Patients with a known prolonged corrected QT interval on electrocardiography were ineligible to receive hydroxychloroquine. (Coadministration with medications that prolong the QT interval was not an absolute contraindication, but attending clinicians were advised to check the QT interval by performing electrocardiography.) These patients were excluded from entry in the randomized comparison between hydroxychloroquine and usual care.

In the hydroxychloroquine group, patients received hydroxychloroquine sulfate (in the form of a 200-mg tablet containing a 155-mg base equivalent) in a loading dose of four tablets (total dose, 800 mg) at baseline and at 6 hours, which was followed by two tablets (total dose, 400 mg) starting at 12 hours after the initial dose and then every 12 hours for the next 9 days or until discharge, whichever occurred earlier (see the Supplementary Appendix).15 The assigned treatment was prescribed by the attending clinician. The patients and local trial staff members were aware of the assigned trial groups.

Procedures

A single online follow-up form was to be completed by the local trial staff members when each trial patient was discharged, at 28 days after randomization, or at the time of death, whichever occurred first. Information was recorded regarding the adherence to the assigned treatment, receipt of other treatments for Covid-19, duration of admission, receipt of respiratory support (with duration and type), receipt of renal dialysis or hemofiltration, and vital status (including cause of death). Starting on May 12, 2020, extra information was recorded on the occurrence of new major cardiac arrhythmia. In addition, we obtained routine health care and registry data that included information on vital status (with date and cause of death) and discharge from the hospital.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality within 28 days after randomization; further analyses were specified at 6 months. Secondary outcomes were the time until discharge from the hospital and a composite of the initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation including extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or death among patients who were not receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at the time of randomization. Decisions to initiate invasive mechanical ventilation were made by the attending clinicians, who were informed by guidance from NHS England and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Subsidiary clinical outcomes included cause-specific mortality (which was recorded in all patients) and major cardiac arrhythmia (which was recorded in a subgroup of patients). All information presented in this report is based on a data cutoff of September 21, 2020. Information regarding the primary outcome is complete for all the trial patients.

Statistical Analysis

For the primary outcome of 28-day mortality, we used the log-rank observed-minus-expected statistic and its variance both to test the null hypothesis of equal survival curves and to calculate the one-step estimate of the average mortality rate ratio in the comparison between the hydroxychloroquine group and the usual-care group. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed to show cumulative mortality over the 28-day period. The same methods were used to analyze the time until hospital discharge, with censoring of data on day 29 for patients who had died in the hospital. We used the Kaplan–Meier estimates to calculate the median time until hospital discharge. For the prespecified composite secondary outcome of invasive mechanical ventilation or death within 28 days (among patients who had not been receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization), the precise date of the initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation was not available, so the risk ratio was estimated instead. Estimates of the between-group difference in absolute risk were also calculated.

All the analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Prespecified analyses of the primary outcome were performed in six subgroups, as defined by characteristics at randomization: age, sex, race, level of respiratory support, days since symptom onset, and predicted 28-day risk of death. (Details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.)

Estimates of rate and risk ratios are shown with 95% confidence intervals without adjustment for multiple testing. The P value for the assessment of the primary outcome is two-sided. The full database is held by the trial team, which collected the data from the trial sites and performed the analyses, at the Nuffield Department of Population Health at the University of Oxford.

The independent data monitoring committee was asked to review unblinded analyses of the trial data and any other information that was considered to be relevant at intervals of approximately 2 weeks. The committee was then charged with determining whether the randomized comparisons in the trial provided evidence with respect to mortality that was strong enough (with a range of uncertainty around the results that was narrow enough) to affect national and global treatment strategies. In such a circumstance, the committee would inform the members of the trial steering committee, who would make the results available to the public and amend the trial accordingly. Unless that happened, the steering committee, investigators, and all others involved in the trial would remain unaware of the interim results until 28 days after the last patient had been randomly assigned to a particular treatment group.

On June 4, 2020, in response to a request from the MHRA, the independent data monitoring committee conducted a review of the data and recommended that the chief investigators review the unblinded data for the hydroxychloroquine group. The chief investigators and steering committee members concluded that the data showed no beneficial effect of hydroxychloroquine in patients hospitalized with Covid-19. Therefore, the enrollment of patients in the hydroxychloroquine group was closed on June 5, 2020, and the preliminary result for the primary outcome was made public. Investigators were advised that any patients who were receiving hydroxychloroquine as part of the trial should discontinue the treatment.

Results

Patients

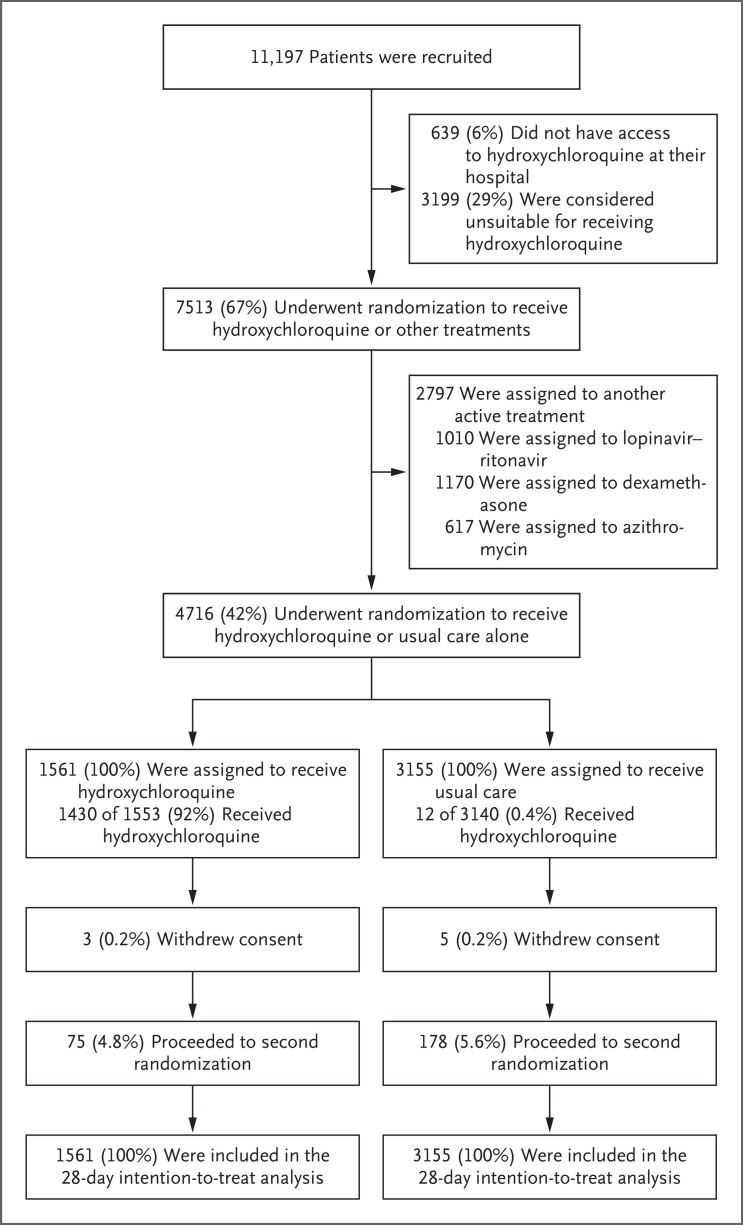

From March 25 to June 5, 2020, a total of 11,197 patients underwent randomization; of these patients, 7513 (67%) were eligible to receive hydroxychloroquine (i.e., the patient had no known indication for or contraindication to hydroxychloroquine, and the drug was available in the hospital at the time) (Figure 1). Of the eligible patients, 1561 were assigned to receive hydroxychloroquine and 3155 were assigned to receive usual care; the remainder of the patients were randomly assigned to one of the other treatment groups.

Figure 1. Enrollment and Outcomes in the RECOVERY Trial.

The enrollment number that is shown is the total number of patients in the RECOVERY platform trial during the period in which adult patients could be recruited for the comparison between hydroxychloroquine and usual care. Patients could have more than one reason for not participating in the hydroxychloroquine trial. At the time of this analysis, data from the trial follow-up form were available for 1553 of 1561 patients (99.5%) in the hydroxychloroquine group and for 3140 of 3155 patients (99.5%) in the usual-care group. The subgroup of patients who later underwent a second randomization to tocilizumab versus usual care in the RECOVERY trial included 37 of 1561 patients (2.4%) in the hydroxychloroquine group and 89 of 3155 patients (2.8%) in the usual care group. In addition, 6 patients were randomly assigned to receive either convalescent plasma or usual care alone (1 patient [0.1%] in the hydroxychloroquine group and 5 patients [0.2%] in the usual-care group) in accordance with protocol version 6.0. Among the 167 sites at which at least 1 patient was assigned to receive hydroxychloroquine, the median number of patients who underwent randomization was 20 (interquartile range, 11 to 41).

The mean (±SD) age of the patients in this trial was 65.4±15.3 years (Table 1 and Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). A total of 38% of the patients were female; 18% were Black or Asian or had a minority ethnic background. No children were enrolled. A history of diabetes was present in 27% of patients, heart disease in 26%, and chronic lung disease in 22%, with 57% having at least one major coexisting illness that was recorded. In this analysis, 90% of the patients had laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, with the result not known for less than 1%. At randomization, 17% were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation including extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, 60% were receiving oxygen only (with or without noninvasive ventilation), and 24% were receiving neither.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline.*.

| Characteristic | Hydroxychloroquine (N=1561) |

Usual Care (N=3155) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean ±SD | 65.2±15.2 | 65.4±15.4 |

| Distribution — no. (%) | ||

| <70 yr | 925 (59.3) | 1873 (59.4) |

| ≥70 to <80 yr | 342 (21.9) | 630 (20.0) |

| ≥80 yr | 294 (18.8) | 652 (20.7) |

| Sex — no. (%) | ||

| Male | 960 (61.5) | 1974 (62.6) |

| Female† | 601 (38.5) | 1181 (37.4) |

| Race or ethnic group — no. (%)‡ | ||

| White | 1181 (75.7) | 2298 (72.8) |

| Black, Asian, or minority ethnic group | 264 (16.9) | 593 (18.8) |

| Unknown | 116 (7.4) | 264 (8.4) |

| Median no. of days since symptom onset (IQR)§ | 9 (5–14) | 9 (5–13) |

| Median no. of days since hospitalization (IQR) | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–5) |

| Respiratory support — no. (%) | ||

| No oxygen received | 362 (23.2) | 750 (23.8) |

| Oxygen only | 938 (60.1) | 1873 (59.4) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 261 (16.7) | 532 (16.9) |

| Previous disease — no. (%) | ||

| Any of the listed conditions | 882 (56.5) | 1807 (57.3) |

| Diabetes | 427 (27.4) | 856 (27.1) |

| Heart disease | 422 (27.0) | 789 (25.0) |

| Chronic lung disease | 334 (21.4) | 712 (22.6) |

| Tuberculosis | 4 (0.3) | 9 (0.3) |

| HIV infection | 8 (0.5) | 13 (0.4) |

| Severe liver disease¶ | 18 (1.2) | 46 (1.5) |

| Severe kidney impairment‖ | 111 (7.1) | 261 (8.3) |

| SARS-CoV-2 test result — no. (%) | ||

| Positive | 1399 (89.6) | 2867 (90.9) |

| Negative | 156 (10.0) | 275 (8.7) |

| Unknown | 6 (0.4) | 13 (0.4) |

Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding. HIV denotes human immunodeficiency virus, IQR interquartile range, and SD standard deviation.

Among the women, 2 in the hydroxychloroquine group and 4 in the usual-care group were pregnant.

Race or ethnic group is reported as it was recorded in the patient’s electronic health record.

Data regarding the number of days since symptom onset were missing for 9 patients in the hydroxychloroquine group and 9 patients in the usual-care group.

Severe liver disease was defined as a diagnosis that resulted in ongoing specialist care.

Severe kidney impairment was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 of body-surface area.

A total of 1430 patients in the hydroxychloroquine group (92%) received at least one dose (Table S2). The median duration of treatment was 6 days (interquartile range, 3 to 10 days). In addition, 12 patients (0.4%) in the usual-care group received hydroxychloroquine. The frequency of use of azithromycin or other macrolide drug during the follow-up period was similar in the hydroxychloroquine group and the usual-care group (18.6% vs. 20.3%), as was the use of dexamethasone (9.1% vs. 9.2%). Remdesivir was administered to less than 0.1% of the patients in each group.

Primary Outcome

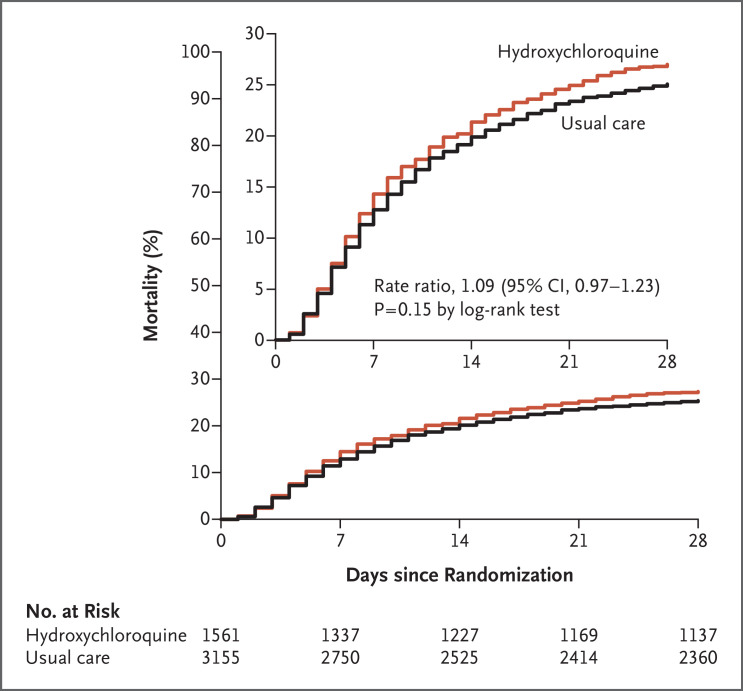

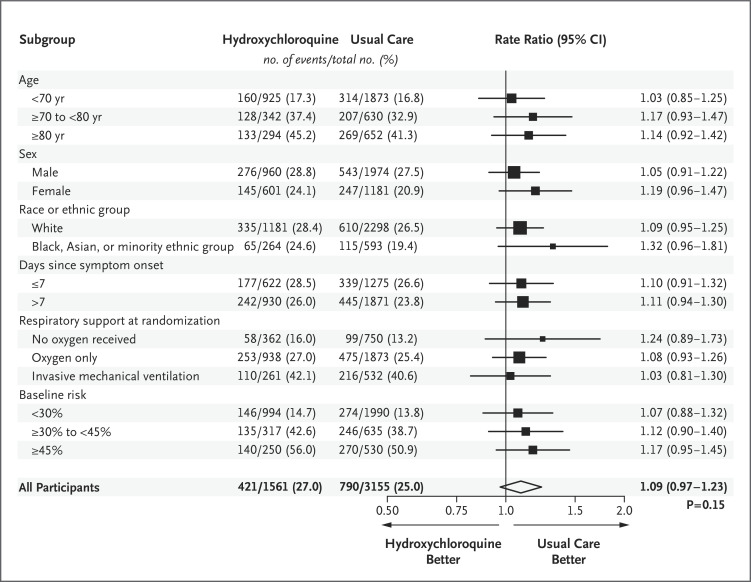

Death at 28 days occurred in 421 of 1561 patients (27.0%) in the hydroxychloroquine group and in 790 of 3155 patients (25.0%) in the usual-care group (rate ratio, 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.97 to 1.23; P=0.15) (Figure 2). Similar results were seen across all six prespecified subgroups (Figure 3). In a post hoc exploratory analysis that was restricted to the 4266 patients (90.5%) with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result, the result was similar to the overall result (rate ratio, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.23).

Figure 2. Mortality at 28 Days.

Death at 28 days (the primary outcome) occurred in 421 patients (27.0%) in the hydroxychloroquine group and in 790 (25.0%) in the usual-care group. The inset shows the same data on an expanded y axis.

Figure 3. Mortality at 28 Days, According to Subgroup.

The size of the squares representing rate ratios is proportional to the amount of statistical information that was available for each comparison. The method that was used for calculating the baseline-predicted risk in each subgroup is described in the Supplementary Appendix. Race or ethnic group was recorded in the patient’s electronic health record.

Secondary Outcomes

Patients in the hydroxychloroquine group had a longer duration of hospitalization than those in the usual-care group (median, 16 days vs. 13 days) and a lower probability of discharge alive within 28 days (59.6% vs. 62.9%; rate ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83 to 0.98) (Table 2). Among the patients who were not undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation at baseline, the number of patients who had progression to the prespecified composite secondary outcome of invasive mechanical ventilation or death was higher among those in the hydroxychloroquine group than among those in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.27).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| Outcome | Hydroxychloroquine (N=1561) |

Usual Care (N=3155) |

Rate or Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| no./total no. (%) | |||

| Primary outcome: 28-day mortality | 421/1561 (27.0) | 790/3155 (25.0) | 1.09 (0.97–1.23)* |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Discharge from hospital in ≤28 days | 931/1561 (59.6) | 1983/3155 (62.9) | 0.90 (0.83–0.98)* |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation or death† | 399/1300 (30.7) | 705/2623 (26.9) | 1.14 (1.03–1.27)‡ |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 128/1300 (9.8) | 225/2623 (8.6) | 1.15 (0.93–1.41) |

| Death | 311/1300 (23.9) | 574/2623 (21.9) | 1.09 (0.97–1.23) |

The between-group difference was calculated as a rate ratio.

Patients who were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization were excluded from this analysis.

The between-group difference was calculated as a risk ratio.

Other Prespecified Outcomes

There was no difference between the hydroxychloroquine group and the usual-care group in 28-day mortality that was ascribed to Covid-19 (24.0% vs. 23.5%). However, patients in the hydroxychloroquine group had a greater risk of death from cardiac causes (mean [±SE] excess, 0.4±0.2 percentage points) and from non–SARS-CoV-2 infection (mean excess, 0.4±0.2 percentage points) (Table S3). Data regarding the occurrence of new major cardiac arrhythmia were collected for 735 of 1561 patients (47.1%) in the hydroxychloroquine group and 1421 of 3155 patients (45.0%) in the usual-care group, after collection of this information was added to the follow-up form on May 12, 2020. Among these patients, there were no significant differences between the hydroxychloroquine group and the usual-care group in the frequency of supraventricular tachycardia (7.6% vs. 6.0%), ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation (0.7% vs. 0.4%), or atrioventricular block requiring intervention (0.1% vs. 0.1%) (Table S4). There was one report of a serious adverse reaction that was deemed by investigators to be related to hydroxychloroquine: a case of torsades de pointes, from which the patient recovered without undergoing intervention. Among the patients who were not receiving renal dialysis or hemofiltration at randomization, the percentage who went on to receive such treatment during the follow-up period was the same in the hydroxychloroquine group and the usual-care group (7.9% vs. 7.9%) (Table S5).

Discussion

In this analysis of the RECOVERY trial, we determined that hydroxychloroquine was not an effective treatment for patients hospitalized with Covid-19. The lower boundary of the confidence limit for the primary outcome ruled out any reasonable possibility of a meaningful mortality benefit. The results were consistent across subgroups according to age, sex, race, time since illness onset, level of respiratory support, and baseline-predicted risk. In addition, the results suggest that the patients who received hydroxychloroquine had a longer duration of hospitalization and, among those who were not undergoing mechanical ventilation at baseline, a higher risk of invasive mechanical ventilation or death than those who received usual care.

The RECOVERY trial is a large, pragmatic, randomized, controlled platform trial designed to assess the effect of potential treatments for Covid-19 on 28-day mortality. Approximately 15% of the patients who were hospitalized with Covid-19 in the United Kingdom during the trial period were enrolled, and the percentage of patients in the usual-care group who died was consistent with the hospitalized case fatality rate among hospitalized patients in the United Kingdom and elsewhere.7,30,31 Only essential data were collected at hospital sites, with additional information (including long-term mortality) ascertained through linkage with routine data sources. We did not collect information on physiologic, electrocardiographic, laboratory, or virologic measurements.

Hydroxychloroquine has been proposed as a treatment for Covid-19 largely on the basis of its in vitro SARS-CoV-2 antiviral activity and on data from observational studies reporting effective reduction in viral loads. However, the 4-aminoquinoline drugs are relatively weak antiviral agents.15 The demonstration of therapeutic efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in severe Covid-19 would require rapid attainment of efficacious levels of free drug in the blood and respiratory epithelium.32 Thus, to provide the greatest chance of providing benefit in life-threatening Covid-19, the dose regimen in our trial was designed to result in rapid attainment and maintenance of plasma levels that were as high as safely possible.15 These levels were predicted to be at the upper end of those observed during steady-state treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with hydroxychloroquine.33 Our dosing schedule was based on pharmacokinetic modeling of hydroxychloroquine that referenced a SARS-CoV-2 50% effective concentration of 0.72 μM, as scaled to whole-blood levels and on the assumption that cytosolic levels in the respiratory epithelium are in dynamic equilibrium with blood levels.8,15,34

The primary concern with short-term, high-dose 4-aminoquinoline regimens is cardiovascular toxicity. Hydroxychloroquine causes predictable prolongation of the corrected QT interval on electrocardiography, which is exacerbated by coadministration with azithromycin, as widely prescribed in Covid-19 treatment.16-18 Although torsades de pointes has been described, serious cardiovascular toxicity has been infrequently reported, despite the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease in hospitalized patients, the common occurrence of myocarditis in Covid-19, and the extensive use of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin together. The exception is a Brazilian study that was stopped early because of cardiotoxicity. However, in that study, chloroquine was administered at a base dose of 600 mg twice daily for 10 days, a higher total dose than those that were used in other trials, including the RECOVERY trial.35,36 Pharmacokinetic modeling in combination with information regarding blood levels and mortality from a case series involving 302 patients with chloroquine overdose predicts that a chloroquine regimen that was equivalent to the hydroxychloroquine regimen used in our trial should have an acceptable safety profile.36 There was a small absolute excess of cardiac mortality of 0.4 percentage points in the hydroxychloroquine group on the basis of very few events, but we did not observe excess mortality in the first 2 days of treatment with hydroxychloroquine, the time when early effects of dose-dependent toxicity might be expected. Furthermore, the data presented here did not show any excess in ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation in the hydroxychloroquine group.

These findings indicate that hydroxychloroquine is not an effective treatment for hospitalized patients with Covid-19 but do not address its use as prophylaxis or in patients with less severe SARS-CoV-2 infection managed in the community. A review of Covid-19 treatment guidelines that was produced early in the pandemic showed that chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine was recommended in China, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and South Korea.37 In the United States, the use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine was permitted in certain hospitalized patients under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). A retrospective cohort study involving 1376 patients with Covid-19 who were admitted to the hospital in New York City in March and April 2020 showed that 59% of the patients received hydroxychloroquine.22,38 Since our preliminary results were made public on June 5, 2020, the FDA has revoked the EUA for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine,39 and the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Institutes of Health have ceased trials of its use in hospitalized patients on the grounds of a lack of benefit. The WHO has released preliminary results from the SOLIDARITY trial on the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 that are consistent with the results from the RECOVERY trial.40

Acknowledgments

We thank the thousands of patients who participated in this trial; the doctors, nurses, pharmacists, other allied health professionals, and research administrators at 176 NHS hospitals across the United Kingdom who were assisted by the NIHR Clinical Research Network, NHS DigiTrials, Public Health England, the Department of Health and Social Care, the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre, Public Health Scotland, National Records Service of Scotland, the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage at University of Swansea, and the NHS in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland; and the members of the independent data monitoring committee: Peter Sandercock, Janet Darbyshire, David DeMets, Robert Fowler, David Lalloo, Ian Roberts, and Janet Wittes.

Protocol

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

Data Sharing Statement

The members of the writing committee (Peter Horby, F.R.C.P., Marion Mafham, M.D., Louise Linsell, D.Phil., Jennifer L. Bell, M.Sc., Natalie Staplin, Ph.D., Jonathan R. Emberson, Ph.D., Martin Wiselka, Ph.D., Andrew Ustianowski, Ph.D., Einas Elmahi, M.Phil., Benjamin Prudon, F.R.C.P., Tony Whitehouse, F.R.C.A., Timothy Felton, Ph.D., John Williams, M.R.C.P., Jakki Faccenda, M.D., Jonathan Underwood, Ph.D., J. Kenneth Baillie, M.D., Ph.D., Lucy C. Chappell, Ph.D., Saul N. Faust, F.R.C.P.C.H., Thomas Jaki, Ph.D., Katie Jeffery, Ph.D., Wei Shen Lim, F.R.C.P., Alan Montgomery, Ph.D., Kathryn Rowan, Ph.D., Joel Tarning, Ph.D., James A. Watson, D.Phil., Nicholas J. White, F.R.S., Edmund Juszczak, M.Sc., Richard Haynes, D.M., and Martin J. Landray, Ph.D.) assume responsibility for the overall content and integrity of this article.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service (NHS), the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This article was published on October 8, 2020, at NEJM.org.

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Supported by a grant (MC_PC_19056) to the University of Oxford from UK Research and Innovation and the NIHR and by core funding provided by NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, Wellcome, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Department for International Development, Health Data Research UK, the Medical Research Council Population Health Research Unit, the NIHR Health Protection Unit in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections, and NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Support Funding. Tocilizumab was provided free of charge for this study by Roche. AbbVie contributed some supplies of lopinavir–ritonavir for use in the trial. The hydroxychloroquine that was used in the trial was supplied by the NHS.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020;382:727-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verity R, Okell LC, Dorigatti I, et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:669-677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 2020;395:507-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao J, Tu W-J, Cheng W, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 102 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:748-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:846-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knight SR, Ho A, Pius R, et al. Risk stratification of patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: development and validation of the 4C Mortality Score. BMJ 2020;370:m3339-m3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res 2020;30:269-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 2020;395:565-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vincent MJ, Bergeron E, Benjannet S, et al. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J 2005;2:69-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou P, Yang X-L, Wang X-G, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020;579:270-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keyaerts E, Vijgen L, Maes P, Neyts J, Van Ranst M. In vitro inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus by chloroquine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;323:264-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigo C, Fernando SD, Rajapakse S. Clinical evidence for repurposing chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as antiviral agents: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020;26:979-987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fantini J, Chahinian H, Yahi N. Synergistic antiviral effect of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in combination against SARS-CoV-2: what molecular dynamics studies of virus-host interactions reveal. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020;56:106020-106020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White NJ, Watson JA, Hoglund RM, Chan XHS, Cheah PY, Tarning J. COVID-19 prevention and treatment: a critical analysis of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine clinical pharmacology. PLoS Med 2020;17(9):e1003252-e1003252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenke K, Jarvis MA, Feldmann F, et al. Hydroxychloroquine proves ineffective in hamsters and macaques infected with SARS-CoV-2. June 11, 2020. (https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.10.145144v1). preprint.

- 17.Gautret P, Lagier J-C, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020;56:105949-105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Gautret P, Lagier J-C, Parola P, et al. Clinical and microbiological effect of a combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in 80 COVID-19 patients with at least a six-day follow up: a pilot observational study. Travel Med Infect Dis 2020;34:101663-101663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Million M, Lagier JC, Gautret P, et al. Early treatment of COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin: a retrospective analysis of 1061 cases in Marseille, France. Travel Med Infect Dis 2020;35:101738-101738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends 2020;14:72-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu B, Li C, Chen P, et al. Low dose of hydroxychloroquine reduces fatality of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Sci China Life Sci 2020. May 15 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geleris J, Sun Y, Platt J, et al. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2411-2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahévas M, Tran V-T, Roumier M, et al. Clinical efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with covid-19 pneumonia who require oxygen: observational comparative study using routine care data. BMJ 2020;369:m1844-m1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molina JM, Delaugerre C, Le Goff J, et al. No evidence of rapid antiviral clearance or clinical benefit with the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with severe COVID-19 infection. Med Mal Infect 2020;50:384-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang W, Cao Z, Han M, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with mainly mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019: open label, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2020;369:m1849-m1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang M, Tang T, Pang P, et al. Treating COVID-19 with chloroquine. J Mol Cell Biol 2020;12:322-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, Liu D, Liu L, et al. A pilot study of hydroxychloroquine in treatment of patients with moderate COVID-19. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2020;49:215-219. (In Chinese.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Z, Hu J, Zhang Z, et al. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: results of a randomized clinical trial. April 10, 2020. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.22.20040758v3). preprint.

- 29.Cavalcanti AB, Zampieri FG, Rosa RG, et al. Hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin in mild-to-moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mekonnen Abate S, Ahmed Ali S, Mantfardo B, Basu B. Rate of intensive care unit admission and outcomes among patients with coronavirus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020;15(7):e0235653-e0235653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armstrong RA, Kane AD, Cook TM. Outcomes from intensive care in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Anaesthesia 2020;75:1340-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Austin D, Okour M. Evaluation of potential therapeutic options for COVID-19. J Clin Pharmacol 2020;60:976-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carmichael SJ, Charles B, Tett SE. Population pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Drug Monit 2003;25:671-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, et al. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:732-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borba MGS, Val FFA, Sampaio VS, et al. Effect of high vs low doses of chloroquine diphosphate as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(4):e208857-e208857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson JA, Tarning J, Hoglund RM, et al. Concentration-dependent mortality of chloroquine in overdose. Elife 2020;9:e58631-e58631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dagens A, Sigfrid L, Cai E, et al. Scope, quality, and inclusivity of clinical guidelines produced early in the covid-19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ 2020;369:m1936-m1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lenzer J. Covid-19: US gives emergency approval to hydroxychloroquine despite lack of evidence. BMJ 2020;369:m1335-m1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Letter from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration re: revocation of the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) letter of March 20, 2020. June 15, 2020. (https://www.fda.gov/media/138945/download).

- 40.World Health Organization. WHO discontinues hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/ritonavir treatment arms for COVID-19. July 4, 2020. (https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/04-07-2020-who-discontinues-hydroxychloroquine-and-lopinavir-ritonavir-treatment-arms-for-covid-19).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.