Dear Editor,

Previous studies have found approximately a 30% cumulative incidence for thrombosis in critically unwell patients, almost all whom already present impaired platelets function and activity, with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit (ICU) [1, 2]. We aimed to explore the association between platelet-related laboratory indicators and prognosis in critically ill patients with COVID-19.

All the severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients (Table 1) diagnosed in Huangshi City, Hubei Province, China, till 6 March, 2020, were recruited in this study which were distributed in the three hospitals including Huangshi Central Hospital, Huangshi Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and Daye People’s Hospital. Laboratory examinations including routine blood tests, lymphocyte subsets, inflammatory or infection-related biomarkers, cardiac, renal, liver and coagulation function tests were obtained at admission and during hospitalization. The baseline laboratory measures with over 40% missing value were excluded from the analysis. Death in 28 days after admission to the hospital was the primary end point of this study. Patients discharge from hospital within 28 days or kept in hospitalization after 28 days were considered as censored outcome. Time-to-event outcome was defined for the following statistical models.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at hospitalization of severe or critically ill COVID-19 patients

| Characteristics | NMissing (%) | Total (n = 112) | Survived (n = 81) | Dead (n = 31) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [mean (SD)] | 61.0 (14.9) | 57.1 (13.8) | 71.0 (13.0) | |

| Male [n (%)] | 73 (65.2) | 54 (66.7) | 19 (61.3) | |

| Vital signs [mean (SD)] | ||||

| Temperature (°C) | 2 (1.8) | 37.3 (0.8) | 37.3 (0.8) | 37.2 (0.8) |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 29 (25.9) | 89.4 (17.7) | 87.1 (16.7) | 94.4 (19.0) |

| Respiratory rate (Breaths/min) | 5 (4.5) | 24.8 (5.6) | 25.1 (5.9) | 24.1 (4.9) |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | ||||

| Diastolic | 5 (4.5) | 73.2 (13.7) | 73.3 (14.7) | 72.8 (11.0) |

| Systolic | 5 (4.5) | 124.9 (17.3) | 124.0 (18.0) | 127.0 (15.7) |

| Symptoms [n (%)] | ||||

| Fever | 91 (81.2) | 67 (82.7) | 24 (77.4) | |

| Cough | 86 (76.8) | 62 (76.5) | 24 (77.4) | |

| Chest tightness | 73 (65.2) | 56 (69.1) | 17 (54.8) | |

| Fatigue | 65 (58.0) | 54 (66.7) | 11 (35.5) | |

| Shortness of breath | 34 (30.4) | 21 (25.9) | 13 (41.9) | |

| Phlegm | 28 (25.0) | 20 (24.7) | 8 (25.8) | |

| Dyspnea | 25 (22.3) | 14 (17.3) | 11 (35.5) | |

| Diarrhea | 19 (17.0) | 15 (18.5) | 4 (12.9) | |

| Headache | 9 (8.0) | 7 (8.6) | 2 (6.5) | |

| Myalgia | 6 (5.4) | 5 (6.2) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Sore throat | 5 (4.5) | 4 (4.9) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 5 (4.5) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Imaging abnormalitya | 18 (16.1) | 13 (16.0) | 5 (16.1) | |

| No. of symptoms [n (%)] | ||||

| 0 | 2 (1.8) | 2 (6.5) | ||

| 1 | 4 (3.6) | 4 (4.9) | ||

| 2 | 15 (13.4) | 10 (12.3) | 5 (16.1) | |

| 3 | 20 (17.9) | 15 (18.5) | 5 (16.1) | |

| 4 | 30 (26.8) | 23 (28.4) | 7 (22.6) | |

| 5 | 23 (20.5) | 16 (19.8) | 7 (22.6) | |

| 6 | 12 (10.7) | 8 (9.9) | 4 (12.9) | |

| ≥ 7 | 6 (5.4) | 5 (6.2) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Comorbidities [n (%)] | ||||

| Hypertension | 40 (35.7) | 26(32.1) | 14 (45.2) | |

| Respiratory failure | 27 (24.1) | 16 (19.8) | 11 (35.5) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 17 (15.2) | 10 (12.3) | 7 (22.6) | |

| Diabetes | 21 (18.8) | 15 (18.5) | 6 (19.4) | |

| Acute lung injury | 14 (12.5) | 9 (11.1) | 5 (16.1) | |

| COPDb | 5 (4.5) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 3 (2.7) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Hepatic injury | 3 (2.7) | 3 (3.7) | ||

| Septic shock | 3 (2.7) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Cerebral infarction | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Acute kidney injury | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Sepsis | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| N of comorbidities [n (%)] | ||||

| 0 | 46 (41.1) | 36 (44.4) | 10 (32.3) | |

| 1 | 26 (23.2) | 20 (24.7) | 6 (19.4) | |

| 2 | 19 (17.0) | 13 (16.0) | 6 (19.4) | |

| 3 | 13 (11.6) | 7 (8.6) | 6 (19.4) | |

| 4 | 4 (3.6) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (6.5) | |

| 5 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| ≥ 6 | 3 (2.7) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Worst severity in hospital | ||||

| Severe | 63 | 63 | 0 | |

| Critical illness [n (%)] | 49 | 18 | 31 | |

SD standard deviation

aIncluding chest radiography and computed tomography (CT)

bChronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The platelet-related indicators included platelet count (PLT), mean platelet volume (MPV), platelet distribution width (PDW), thrombocytocrit (PCT), and platelet large cell ratio (P-LCR). Baseline indicators were dichotomized by the median to low and high groups. For each platelet-related indicator with repeated examinations during hospitalization, trajectory analysis was performed to cluster the patients based on the dynamic time-series trend of the corresponding indicator, using R package traj [3]. According to the requirement of the method, patients during hospitalization with less than four observations of the specific indicator were classified as a separate cluster. Cox proportional hazards model with adjustment for age, gender, number of comorbidities were applied to test the association between dynamic trajectory of platelet-related indicators and overall survival of COVID-19 patients.

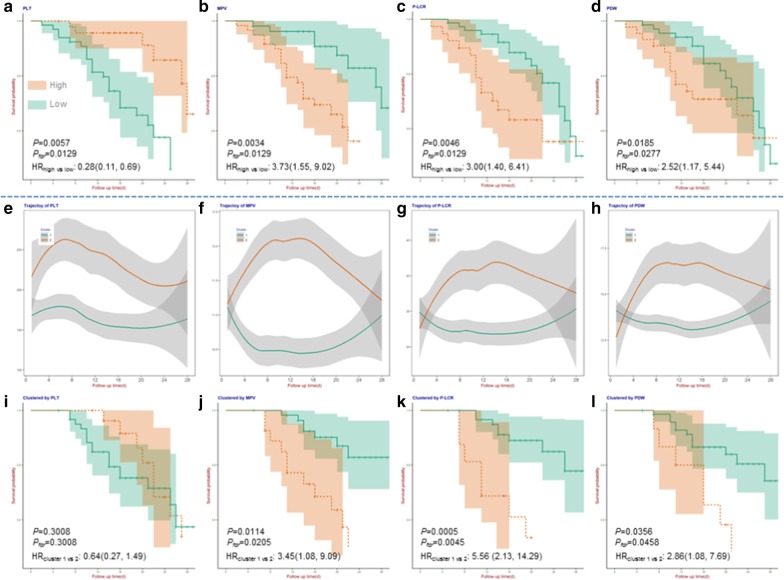

The patients at admission with high PLT (HR 0.28; 95% CI 0.11–0.69; P = 0.0057; Fig. 1a) were associated with the preferred survival; however, patients with high PDW (HR 2.52; 95% CI 1.17–5.44; P = 0.0185; Fig. 1b), high MPV (HR 3.73; 95% CI 1.55–9.02; P = 0.0034; Fig. 1c), or high P-LCR (HR 3.00; 95% CI 1.40–6.41; P = 0.0046; Fig. 1d) were significantly associated with the worse survival. On the other hand, dynamic trajectory of PLT couldn’t distinguish patients’ survival (Fig. 1e). However, a similar dynamic trajectory pattern with rapid acceleration in the first 2 weeks followed by a considerable deceleration, was identified for MPV, PLCR, and PDW; patients with such pattern were significantly associated with about 2 to 5 times increased death hazard (Fig. 1f–h). All the above results remained significant after false discovery rate (FDR) control.

Fig. 1.

Platelet-related indicators and their dynamic changes that associated with prognosis of severe or critically ill COVID-19 patients. a association between baseline platelet count (PLT) and prognosis of patients; b association between baseline mean platelet volume (MPV) and prognosis of patients; c association between baseline platelet large cell ratio (P-LCR) and prognosis of patients; d association between baseline platelet distribution width (PDW) and prognosis of patients; e trajectory of PLT; f trajectory of MPV; g trajectory of P-LCR; h trajectory of PDW; i association between trajectory of PLT and prognosis of patients; j association between trajectory of MPV and prognosis of patients; k association between trajectory of P-LCR and prognosis of patients; l association between trajectory of PDW and prognosis of patients. Thrombocytocrit (PCT) was not significant after false discovery rate control (P = 0.0545), and the trajectory of PCT was not available because the majority of patients lacked follow-up nodes

The findings of this study were accordant with several evidences suggesting platelets as well as related indicators participating in inflammation and prothrombotic responses in many viral infections [4]. The damage to endothelial cells leads to activation, aggregation, and retention of platelets, and the formation of thrombus at the injured site, which may cause a depletion of platelets and megakaryocytes, resulting in decreased platelets production and increased consumption. In addition to their traditional role in thrombosis and hemostasis, platelets mediate key aspects of inflammatory and immune processes [5]. Platelets have been reported to express surface receptors able to mediate binding and entry of various viruses [6]. In brief, paying close attention to the dynamics of platelet-related indicators of COVID-19 patients will undoubtedly improve our knowledge on diseases progression, but could also bring the improvement in therapeutic options for severe or critically ill patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the medical staff for their efforts in collecting the data used in this study, and all the patients who consented to donate their data for analysis and the all medical staff members who are on the front line of caring for patients.

Authors’ contributions

Y.W. and J.H conducted drafting of the manuscript. Y.W., J.H., and F.C. performed statistical analysis and interpretation. Samples and data collection was done by J.C. and W.G. Study conception and supervision were done by X.L., W.G. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81770440 and 81970218 to XL, 81970217 to WG, 82041024 to FC, 81973142 to YW).

Availability of data and materials

Dr. X. Lu had full access to all of the data in the study. After publication, the data will be made available to others on reasonable requests after approval from the author (luxiang66@njmu.edu.cn).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of the hospitals (Huangshi Central Hospital, Huangshi Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and Daye People’s Hospital) waived the written informed consent from patients with COVID-19, and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care.

Consent for publication

The informed consents of patients were waived by the Ethics Commission of the hospitals (Huangshi Central Hospital, Huangshi Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and Daye People’s Hospital) for the rapid emergence of this epidemic.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jieyu He and Yongyue Wei contributed equally to the work.

Contributor Information

Wei Gao, Email: gaowei84@njmu.edu.cn.

Xiang Lu, Email: luxiang66@njmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, Kaptein FHJ, van Paassen J, Stals MAM, Huisman MV, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas W, Varley J, Johnston A, Symington E, Robinson M, Sheares K, Lavinio A, Besser M. Thrombotic complications of patients admitted to intensive care with COVID-19 at a teaching hospital in the United Kingdom. Thromb Res. 2020;191:76–77. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leffondré K, Abrahamowicz M, Regeasse A, Hawker GA, Badley EM, Belzile E. Statistical measures were proposed for identifying longitudinal patterns of change in quantitative health indicators. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(10):1049–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hottz ED, Bozza FA, Bozza PT. Platelets in immune response to virus and immunopathology of viral infections. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:121. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo L, Rondina MT. The era of thromboinflammation: platelets are dynamic sensors and effector cells during infectious diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2204. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chabert A, Hamzeh-Cognasse H, Pozzetto B, Cognasse F, Schattner M, Gomez RM, Garraud O. Human platelets and their capacity of binding viruses: meaning and challenges? BMC Immunol. 2015;16:26. doi: 10.1186/s12865-015-0092-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Dr. X. Lu had full access to all of the data in the study. After publication, the data will be made available to others on reasonable requests after approval from the author (luxiang66@njmu.edu.cn).