Old age represents an adverse prognostic factor in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). In fact, although in the last decades HL survival has improved also in patients above 60 years of age,1 lower 5-year overall survival (OS) rates (40-65%) and progression free survival (PFS)/freedom from treatment failure rates (44-60%) have been observed.2-4 Poor outcomes in older patients are likely due to several factors. First, elderly patients have more comorbidities which can lead to increased toxicity of chemotherapeutic regimens, can compromise dose-intensity or, in some cases, make the use of polychemotherapy impossible.5,6 Secondly, HL appears to have a different biology in older patients: in fact, an increased frequency of mixed cellularity subtype and Epstein Barr virus-related disease have been observed. Moreover, older patients often present with “B” symptoms.2 The treatment of relapsed/refractory (R/R) elderly HL patients is challenging. In a previous retrospective study from the German Hodgkin Study Group, responses and survival of patients above 60 years of age affected by R/R HL were analyzed. Best responses were observed with conventional chemoradiotherapy; in fact, complete response (CR) rates of 30%, 59% and 12% were registered after treatment with intensified salvage treatments, conventional chemotherapy and/or salvage radiotherapy, and palliative approaches, respectively; OS was 10 months, 41 months and 7 months, respectively.

Recent retrospective studies demonstrated the efficacy of brentuximab vedotin (BV) in older patients affected by R/R HL, although duration of response appeared to be quite short.8,9

We present a single-arm, open-label, multicenter, phase II clinical trial, aimed at evaluating the antitumor efficacy and safety of BV as first salvage therapy in elderly patients with R/R HL (FIL_BVHD01). Patients aged ≥60 years, who were not suitable for high dose chemotherapy, were eligible if affected by histologically confirmed CD30+ HL at first relapse or with primary refractory disease. The study involved five Italian Centers adhering to the Italian Lymphoma Foundation (Fondazione Italiana Linfomi, FIL) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of each participating site. Written informed consent was obtained from patients before any study procedure. The trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02227433, and given the EudraCT number 2013-004109-24.

Treatment consisted in 1.8 mg/kg BV administered as a single outpatient intravenous infusion on Day 1 of each 21-day treatment cycle, for a maximum of 16 cycles. The efficacy of single agent BV was measured by overall objective response rate (ORR, sum of CR and partial response [PR] rates). Secondary endpoints were CR rate, disease free survival (DFS), 1-year PFS, 1-year OS and safety and tolerability of BV. OS was calculated from the start of the treatment to the date of death due to any cause and was censored at the last date the patient was known to be alive. DFS was estimated for patients who achieved a CR as time to relapse or death as a result of lymphoma or acute toxicity of treatment from first documentation of response. PFS was calculated as the time from the beginning of treatment until lymphoma progression or death due to any cause. Responses were determined using the Revised Response Criteria for Malignant Lymphoma.10

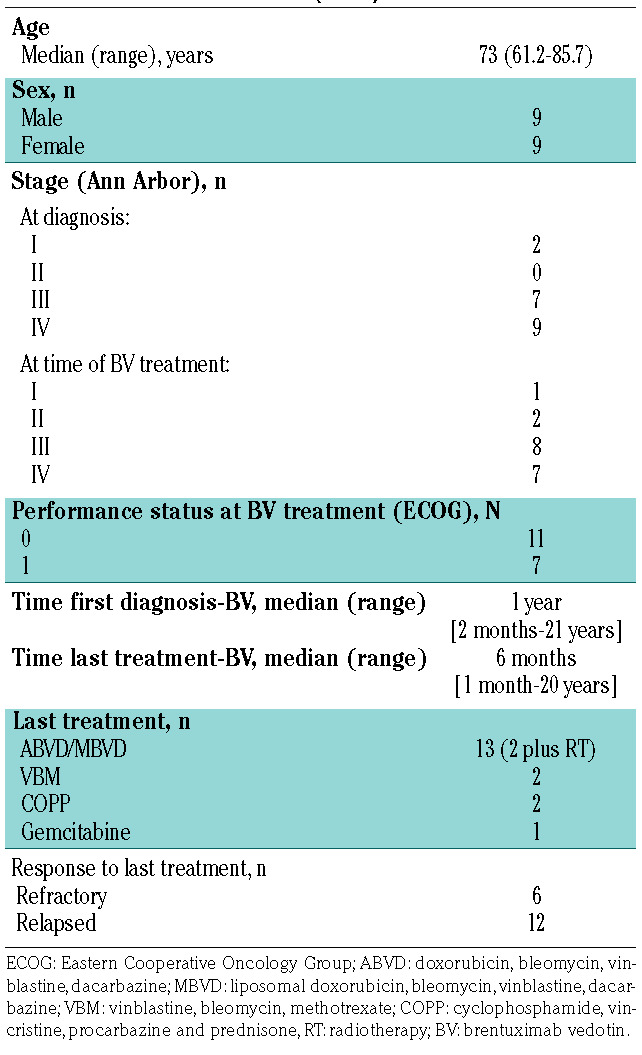

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics (n=18).

Any adverse event (AE) occurred during treatment was encoded according to NCI Common Terminology Criteria for AE v. 4.03. Demographics and patients’ characteristics were summarized by descriptive statistics and survival functions were estimated by using the Kaplan- Meier method. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 11 (StataCorp LP, TX, USA).

Twenty patients were enrolled. Eighteen patients were evaluable for safety analysis (two screening failures) and 17 for efficacy analysis (one patient was neither primary refractory nor at first relapse). Nine males and nine females with a median age of 73 years (range: 61.2-85.7) underwent BV therapy. The median time from diagnosis to BV treatment was 1 year and the median time from last the treatment to BV administration was 6 months. All patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients underwent a median of seven cycles of BV monotherapy (range: 1-16). Two patients (12%) completed the therapeutic program receiving the 16 scheduled cycles of treatment, seven patients discontinued treatment early due to lack of response or progression of the disease, seven for toxicity and one patient was lost to follow- up.

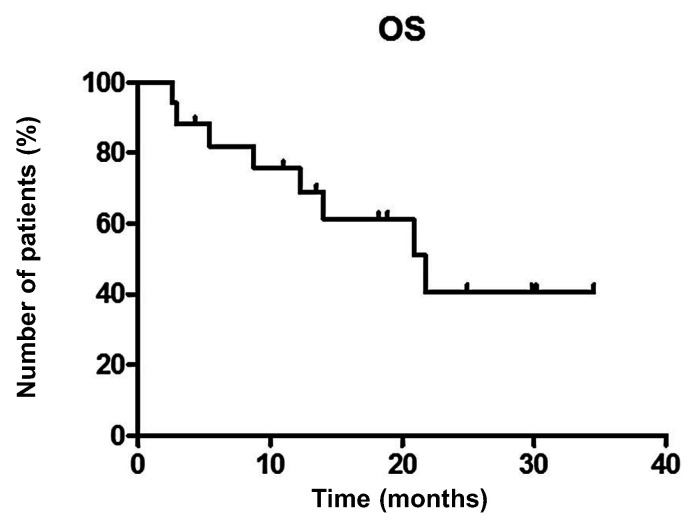

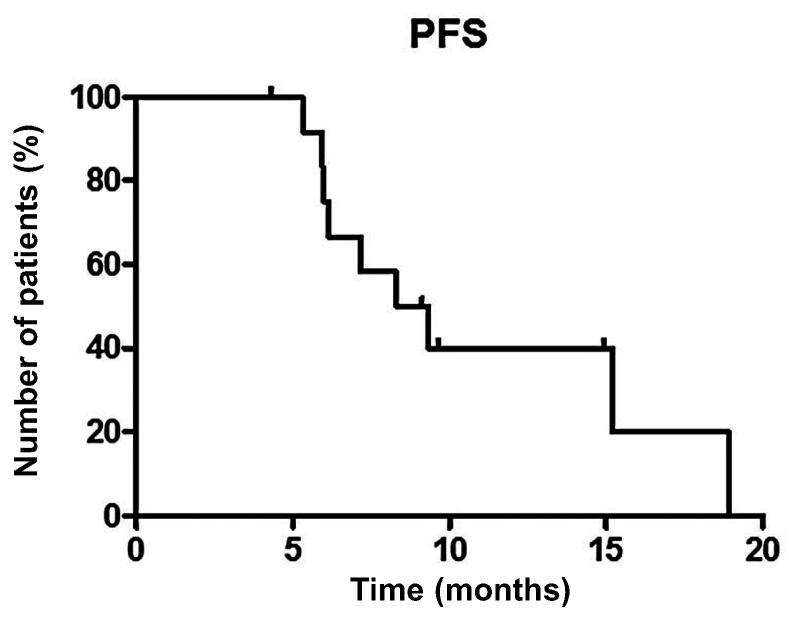

Best response was reached at fourth cycle of BV therapy. ORR was 52.9% (9 of 17 patients) with a CR rate of 23.5% (4 of 17 patients). With a median follow-up of 24.9 months, median PFS was 8.8 months and median OS was 21.7 months. 1-year PFS and OS were 40% and 68.8%, respectively (Figure 1-2). Median time to next treatment was 2 months. Median DFS was 3.9 months: among the four patients who achieved a CR, three relapsed (at 2.8, 3.4 and 4.4 months, respectively) while one patient is still in CR 16.4 months after the end of treatment.

Figure 1.

Patients’ overall survival (OS).

Figure 2.

Patients’ progression free survival (PFS).

The most common AE were hematological: five cases (27%) of neutropenia (one grade 1, two grade 2, two grade 3) and one grade 3 thrombocytopenia (5%) were observed. The most frequent extra-hematological toxicity was neuropathy, which occurred in six patients (33%) starting from cycle 2 (two grade 1, three grade 2, one grade 3). Three patients (16%) experienced hepatic toxicity (two grade 2, one grade 3), while skin rash occurred in four patients (22%) and gastric symptoms in three patients (16%). Overall, seven serious adverse events (SAE) and two suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSAR) were observed in nine patients (50%), six of them judged related to BV. SAE included three infectious complications, three cases of polyneuropathy, and one case of nausea/vomiting; SUSAR included one amylase and lipase elevation and one stroke. All SAE lead to treatment discontinuation.

Currently, no standard second-line treatment is available in this setting of elderly R/R HL. In some selected cases, high-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT can represent a curative option. Nevertheless, most of elderly patients are not eligible to high dose chemotherapy due to comorbidities or poor performance status. In such patients, a non-chemotherapeutic approach could represent the best treatment option.

Efficacy and safety of BV have been demonstrated also in older patients as first-line treatment approach: despite high ORR and CR rate (92% and 73%, respectively), responses were not durable: in fact, the median PFS was 10.5 months.11

Efficacy and safety of BV have been demonstrated also in older patients as first-line treatment approach: despite high ORR and CR rate (92% and 73%, respectively), responses were not durable: in fact, the median PFS was 10.5 months.11

In our study, we observed a lower ORR (52.9%) and PFS (8.8 months); these inferior outcomes could be due to the significantly higher median age of our patient population (73 vs. 66.7 years), with all the limitations to compare efficacy with effectiveness. We also observed a higher incidence of peripheral neuropathy (33.3%), which is indeed in line with data from the phase II pivotal trial (42%);12 this discrepancy could be explained by the retrospective nature of the Bröckelmann and colleagues’ study: it is possible that such AE were underreported.9 Of note, we observed a high rate of AE which led to hospitalization, which suggests that this subset of frail patients should be carefully monitored during treatment with BV.

To our knowledge, our study is the first trial evaluating efficacy and safety of BV in elderly patients affected by HL in the first relapse or refractory to first line treatment. The main limitations of the study are represented by the lack of a control group and the lack of frailty and geriatric assessment. However, one inclusion criteria was ECOG performance status ≤1 to guarantee the patient’s capacity to perform daily life activities.

We observed a low rate of durable responses in a population of patients who were not heavily pretreated. Moreover, only two patients (12%) were able to complete the 16 scheduled cycles of treatment; this could suggest that the optimal number of cycles for older patients should be lower. With regards to toxicity, results were unexpected on the basis of previous reports:11,12 earlier dose reductions of BV to improve tolerability should be considered. With a median age of 73, combination chemotherapy could still be considered in this population, or appealing strategies could include checkpoint inhibition alone or in combination with BV.13 However, the small sample size could have biased study results. Therefore, further studies are needed to identify the subset of patients who could benefit more from treatment with BV, and case-control studies are needed to compare BV with other therapeutic regimens in this specific population. Altogether, multicenter collaborations that integrate novel agents and incorporate formal assessments of functional status to tailor therapy on a patient-specific basis will be critical to the successful study of and improved outcomes for older patients with HL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the numerous clinicians and nurses at institutions and associated hospitals who treated the patients; and the patients who participated in this study.

Funding Statement

Funding. this study was partially supported by Takeda (ID X25008).

References

- 1.Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Ongoing improvement in long-term survival of patients with Hodgkin disease at all ages and recent catchup of older patients. Blood. 2008;111(6):2977-2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engert A, Ballova V, Haverkamp H, et al. Hodgkin's lymphoma in elderly patients: a comprehensive retrospective analysis from the German Hodgkin's Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5052-5060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landgren O, Algernon C, Axdorph U, et al. Hodgkin's lymphoma in the elderly with special reference to type and intensity of chemotherapy in relation to prognosis. Haematologica. 2003;88(4):438-444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evens AM, Helenowski I, Ramsdale E, et al. A retrospective multicenter analysis of elderly Hodgkin lymphoma: outcomes and prognostic factors in the modern era. Blood. 2012;119(3):692-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Spronsen DJ, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Lemmens VE, Peters WG, Coebergh JW. Independent prognostic effect of co-morbidity in lymphoma patients: results of the population-based Eindhoven Cancer Registry. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(7):1051-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Böll B, Goergen H, Behringer K, et al. Bleomycin in older early-stage favorable Hodgkin lymphoma patients: analysis of the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) HD10 and HD13 trials. Blood. 2016; 127(18):2189-2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Böll B, Goergen H, Arndt N, et al. Relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma in older patients: a comprehensive analysis from the German Hodgkin Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(35):4431-4437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gopal AK, Bartlett NL, Forero-Torres A, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in patients aged 60 years or older with relapsed or refractory CD30- positive lymphomas: a retrospective evaluation of safety and efficacy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(10):2328-2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bröckelmann PJ, Zagadailov EA, Corman SL, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma who are Ineligible for autologous stem cell transplant: A Germany and United Kingdom retrospective study. Eur J Haematol. 2017; 99(6):553-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):579-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forero-Torres A, Holkova B, Goldschmidt J, et al. Phase 2 study of frontline brentuximab vedotin monotherapy in Hodgkin lymphoma patients aged 60 years and older. Blood. 2015;126(26):2798-2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(18):2183-2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasenchak CA, Bordoni R, Yazbeck V, et al. Phase 2 study of frontline brentuximab vedotin plus nivolumab in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma aged ≥60 years. Blood. 2019;134(Suppl 1):237. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.