Abstract

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) marks the third highly pathogenic coronavirus to spill over into the human population. SARS-CoV-2 is highly transmissible with a broad tissue tropism that is likely perpetuating the pandemic. However, important questions remain regarding its transmissibility and pathogenesis. In this review, we summarize current SARS-CoV-2 research, with an emphasis on transmission, tissue tropism, viral pathogenesis, and immune antagonism. We further present advances in animal models that are important for understanding the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2, vaccine development, and therapeutic testing. When necessary, comparisons are made from studies with SARS to provide further perspectives on coronavirus infectious disease 2019 (COVID-19), as well as draw inferences for future investigations.

Keywords: severe acute respiratory syndrome; coronavirus; COVID-19; SARS, SARS-CoV-2

Highlights

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 from China and the rapidity of a worldwide pandemic has promoted global collaboration, built on a body of work established from previous SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV outbreaks. These past experiences have aided the swiftness by which the research community has responded with an astonishing body of work.

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel virus in the Betacoronavirus genus and exhibits similarities to SARS-CoV in genome structure, tissue tropism, and viral pathogenesis. Yet, SARS-CoV-2 appears to be more transmissible and the diversity of immune responses are poorly understood.

Highly pathogenic coronaviruses display potent interferon (IFN) antagonism, which is evident in cases of severe COVID-19 with reduced IFN signaling, and an overaggressive immune response compounded by heightened cytokines/chemokines.

Animal models for SARS-CoV-2 recapitulate important aspects of human COVID-19 that are essential for evaluating current and prospective antiviral therapeutics and vaccine candidates.

The Emergence of a Third, Novel Coronavirus

Current State of the COVID-19 Pandemic

CoVs have caused three large-scale outbreaks over the past two decades: severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS), and now COVID-19. The origin of the COVID-19 pandemic was traced back to a cluster of pneumonia cases connected to a wet seafood market in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China [1]. Following the likely spillover of a zoonotic disease (see Glossary), further work confirmed the etiological agent to be a novel Betacoronavirus related to SARS-CoV [1,2]. The first patients developed symptoms on December 1, 2019 after which rapid human-to-human transmission and intercontinental spread later ensued, being declared a pandemic by the WHO in March 2020 [3]. Since then, ~35 million people have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, with >1 million deaths in 235 countries, areas, or territories [4]. Although SARS-CoV-2 appears to be less lethal than SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV, its transmissibility is higher. To find solutions to contain this raging pandemic, global research efforts have been quickly mobilized, each day resulting in new advances in basic and clinical research, therapy, diagnosis, vaccine and drug development, as well as epidemiology. Here, we conduct a comprehensive review of the current state of COVID-19 research, with a principal focus on the mechanisms of transmission and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 stemming from clinical and animal studies.

SARS-CoV-2 Characteristics

SARS-CoV-2 Genome and Structure

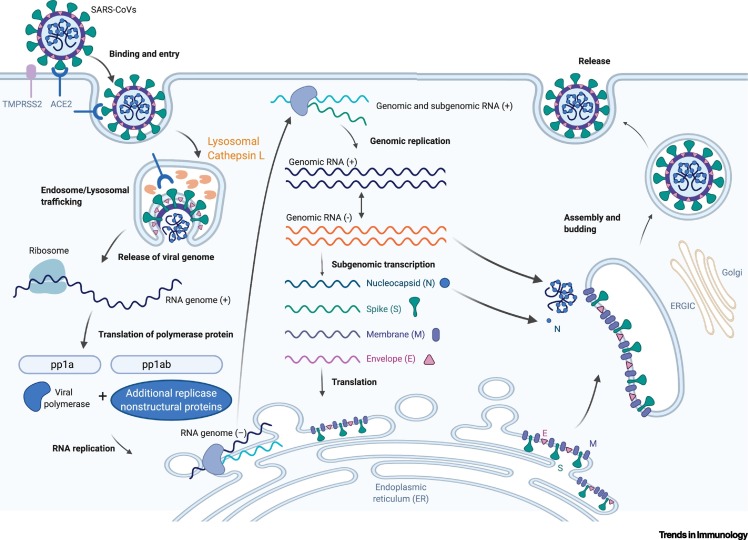

CoVs of the family Coronaviridae are enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses [5]. All of the highly pathogenic CoVs, including SARS-CoV-2, belong to the Betacoronavirus genus, group 2 [5]. The SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence shares ~80% sequence identity with SARS-CoV and ~50% with MERS-CoV [1,6]. Its genome comprises 14 open reading frames (ORFs), two-thirds of which encode 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp 1–16) that make up the replicase complex [6,7]. The remaining one-third encodes nine accessory proteins (ORF) and four structural proteins: spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N), of which Spike mediates SARS-CoV entry into host cells [8]. However, the S gene of SARS-CoV-2 is highly variable from SARS-CoV, sharing <75% nucleotide identity [1,6,9]. Spike has a receptor-binding domain (RBD) that mediates direct contact with a cellular receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), and an S1/S2 polybasic cleavage site that is proteolytically cleaved by cellular cathepsin L and the transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) (Figure 1 ) [1,9,10]. TMPRSS2 facilitates viral entry at the plasma membrane surface, whereas cathepsin L activates SARS-CoV-2 Spike in endosomes and can compensate for entry into cells that lack TMPRSS2 (Figure 1) [10]. Once the genome is released into the host cytosol, ORF1a and ORF1b are translated into viral replicase proteins, which are cleaved into individual nsps (via host and viral proteases: PLpro); these form the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (nsp12 derived from ORF1b) [8]. Here, the replicase components rearrange the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) into double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) that facilitate viral replication of genomic and subgenomic RNAs (sgRNA); the latter are translated into accessory and viral structural proteins that facilitate virus particle formation (Figure 1) [11,12].

Figure 1.

The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Lifecycle.

The SARS-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2) lifecycle commences by binding of the envelope Spike protein to its cognate receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Efficient host cell entry then depends on: (i) cleavage of the S1/S2 site by the surface transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2); and/or (ii) endolysosomal cathepsin L, which mediate virus–cell membrane fusion at the cell surface and endosomal compartments, respectively. Through either entry mechanism, the RNA genome is released into the cytosol, where it is translated into the replicase proteins (open reading frame 1a/b: ORF1a/b). The polyproteins (pp1a and pp1b) are cleaved by a virus-encoded protease into individual replicase complex nonstructural proteins (nsps) (including the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: RdRp). Replication begins in virus-induced double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) derived from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which ultimately integrate to form elaborate webs of convoluted membranes. Here, the incoming positive-strand genome then serves as a template for full-length negative-strand RNA and subgenomic (sg)RNA. sgRNA translation results in both structural proteins and accessory proteins (simplified here as N, S, M, and E) that are inserted into the ER–Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) for virion assembly. Finally, subsequent positive-sense RNA genomes are incorporated into newly synthesized virions, which are secreted from the plasma membrane [6,8,11,12]. Figure generated with BioRender.

Tissue Tropism of SARS-CoV-2

The establishment of viral tropism depends on the susceptibility and permissiveness of a specific host cell. During the SARS epidemic, patients often presented with respiratory-like illnesses that progressed to severe pneumonia, observations mirroring the disease course of COVID-19, suggesting that the lung is the primary tropism of SARS-CoV-2 [13]. Both CoVs were then found to bind the same entry receptor, ACE2 [1,14,15]. Of note, the key mutations in the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 Spike make additional close contacts with ACE2, correlating with higher binding affinity and perhaps increased infectivity [1,14,16]. The presence of a unique furin cleavage site at the S1/S2 junction of SARS-CoV-2 Spike is also suspected to enhance human transmission events, although this remains to be further investigated [17,18]. The currently predominant SARS-CoV-2 isolate worldwide carries a D614G mutation that is absent from its presumptive common ancestor, and is more infectious, likely underlying, in part, an increased human-to-human transmission efficiency [19., 20., 21.]. Although associated with an increased viral load in the upper respiratory tract (URT) of patients with COVID-19, the D614G variant does not correlate with disease severity, suggesting that pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 is linked to mechanisms that are more than just SARS-CoV-2 infectivity [21].

Once SARS-CoVs enter the host via the respiratory tract, airway and alveolar epithelial cells, vascular endothelial cells and alveolar macrophages are among their first targets of viral entry [22., 23., 24.]. These cells are probably ‘ground-zero’ for early infection and subsequent replication due to their expression of ACE2 [25]. Although ACE2 mRNA is detected in human and many mammalian (bat, ferret, cat, dog, etc.) lung biopsies, their expression is rather low compared with extrapulmonary tissues [26]. Thus, the permissiveness of these cells to SARS-CoVs may depend on additional, unappreciated cell-intrinsic factors that aid in efficient infection. First, viral entry may heavily depend on the expression of TMPRSS2, because nearly undetectable amounts of ACE2 still support SARS-CoV entry as long as TMPRSS2 is present [27]. Second, the mRNA expression of cellular genes, such as endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery gene members (including CHMP3, CHMP5, CHMP1A, and VPS37B) related to a pro-SARS-CoV-2 lifecycle is higher in a small population of human type II alveolar cells with abundant ACE2, relative to ACE2-deficient cells [28]. This suggests that SARS-CoV-2 hijacks a small population of type II alveolar cells with high expression of ACE2 and other proviral genes for its productive replication. Third, the lung, as the main tropism of SARS-CoVs, may be contingent on the regulation of ACE2 at the transcriptional and protein levels [24,25,29., 30., 31.]. For example, in human airway epithelial cells, ACE2 gene expression is upregulated by type I and II interferons (IFNs) [25,31] during viral infection. Lastly, compared with other SARS-CoVs, SARS-CoV-2 Spike contains a unique insertion of RRAR at the S1/S2 cleavage site [17,18]. This site can be precleaved by furin, thus reducing the dependence of SARS-CoV-2 on target cell proteases (TMPRSS2/cathepsin L) for entry [17,18] and potentially extending its cellular tropism, given that proteolytically active furin is abundantly expressed in human bronchial epithelial cells [32,33].

One of the distinctions between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 is the ability of the latter to efficiently infect the URT, such as nasopharyngeal (NP) and/or oropharyngeal (OP) tissues, possibly due to its higher affinity for ACE2, which is expressed in human nasal and oral tissues [23,25,34., 35., 36.]. The readily detectable titers of SARS-CoV-2 in the URT mucus of patients with COVID-19 during prodromal periods might help explain the more rapid and effective transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 relative to SARS-CoV [37].

Human CoVs often cause enteric infections, with variable degrees of pathogenicity [38]. Indeed, ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are abundantly expressed within the human and many other mammalian intestinal tracts, specifically the brush border of intestinal enterocytes [23,25,26,39]. Accordingly, gastrointestinal illness has been frequently reported in patients with COVID-19 [40,41], consistent with the recovery of SARS-CoV from stool samples of patients with SARS [42], suggesting a potential fecal–oral route of transmission for these two CoVs. Of note, ~20% of patients with COVID-19 examined have had detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA in feces, even after respiratory symptoms subsided, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 titers may be prolonged in the intestinal tract [41]. Although further testing is warranted, these data suggest the possibility that fecal–oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 occurs. Evidently, robust epidemiological studies are needed to conclusively demonstrate whether patients with COVID-19 recovering from respiratory illness are able to spread SARS-CoV-2.

Transmission Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2

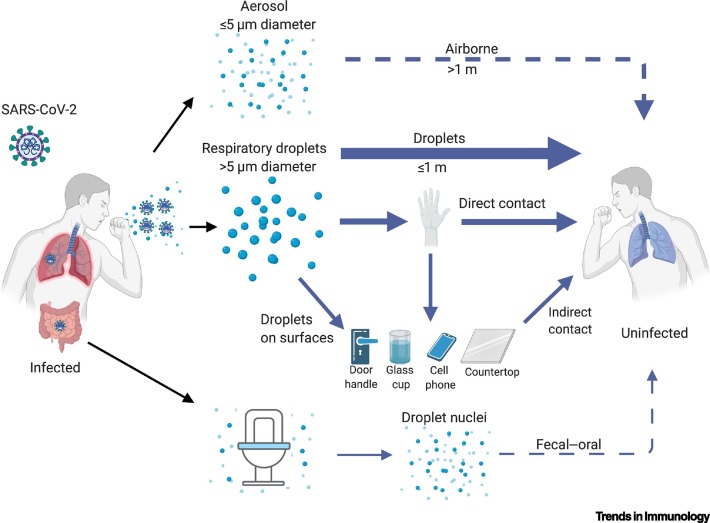

Human CoVs are transmitted primarily through respiratory droplets, but aerosol, direct contact with contaminated surfaces, and fecal–oral transmission were also reported during the SARS epidemic [43., 44., 45.]. Early reports of patients with cough, lung ground glass opacities, and symptom progression to severe pneumonia, suggested communicability of SARS-CoV-2 via the respiratory route (Figure 2 ) [1., 2., 3.]. Direct transmission by respiratory droplets is reinforced by productive SARS-CoV-2 replication in both the URT and lower respiratory tract (LRT), and the increasing number of reports indicating human-to-human spread among close contacts exhibiting active coughing (Figure 2) [35,46., 47., 48.]. So far, the basic reproduction number (R0) is ~2.2, based on early case tracking during the beginning of the pandemic, with a doubling time of 5 days [47,49]. Furthermore, there is now evidence for nonsymptomatic/presymptomatic spread of SARS-CoV-2, which is in contrast to the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV [50]. This finding underscores the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to colonize and replicate in the throat during early infection [37,51,52]. Based on these apparent disparities in virus transmission, one study modeled the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 in presymptomatic individuals, and indicated that the presymptomatic R0 has approached the threshold for sustaining an outbreak on its own (R0 >1); by contrast, the corresponding estimates for SARS-CoV were approximately zero [49]. Similarly, asymptomatic spread of SARS-CoV-2 has been documented throughout the course of the pandemic [48,51,53., 54., 55., 56.]. Understanding the relative importance of cryptic transmission to the current COVID-19 pandemic is essential for public health authorities to make the most comprehensive and effective disease control measures, which include mask-wearing, contact tracing, and physical isolation.

Figure 2.

Proposed Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Transmission Routes.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in numerous accounts of different transmission routes between humans. Droplet transmission (>5 μm) is the most pronounced and heavily implicated mode of transmission reported during the pandemic. Direct contact spread from one infected individual to a second, naïve person has also been considered a driver of human-to-human transmission, especially in households with close interactions between family members. The contagiousness of SARS-CoV-2 after disposition on fomites (e.g., door handles) is under investigation, but is likely a compounding factor for transmission events, albeit less frequently than droplet or contact-driven transmission. Both airborne and fecal–oral human-to-human transmission events were reported in the precursor SARS-CoV epidemic but have yet to be observed in the current crises. Solid arrows show confirmed viral transfer from one infected person to another, with a declining gradient in arrow width denoting the relative contributions of each transmission route. Dashed lines show the plausibility of transmission types that have yet to be confirmed. SARS-CoV-2 symbol in ‘infected patient’ indicates where RNA/infectious virus has been detected [43,44,47., 48., 49.,57,59,60]. Figure generated with BioRender.

For SARS-CoV-2, various modes of transmission have been proposed, including aerosol, surface contamination, and the fecal–oral route, representing confounding factors in the current COVID-19 pandemic; thus, their relative importance is still being investigated (Figure 2) [57]. Aerosol transmission (spread >1 m) was implicated in the Amoy Gardens outbreak during the SARS epidemic, but the inconsistency of these findings in other settings suggested that SARS-CoV was an opportunistic airborne infection [43,58]. Similarly, no infectious SARS-CoV-2 virions have been isolated, although viral RNA was detectable in the air of COVID-19 hospital wards [59]. Generation of experimental aerosols carrying SARS-CoV-2 (comparable to those that might be generated by humans) have offered the plausibility of airborne transmission, but the aerodynamic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 during a natural course of infection is still an area of intense inquiry [60]. Nonetheless, deposition of virus-laden aerosols might contaminate objects (e.g., fomites) and contribute to human transmission events [59,61]. Finally, fecal–oral transmission has also been considered as a potential route of human spread, but remains an enigma despite evidence of RNA-laden aerosols being found nearby toilet bowls, along with detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA in rectal swabs during the precursor epidemic of COVID-19 in China [41,59,62].

SARS-CoV-2 Pathogenesis

Clinical Presentation of COVID-19

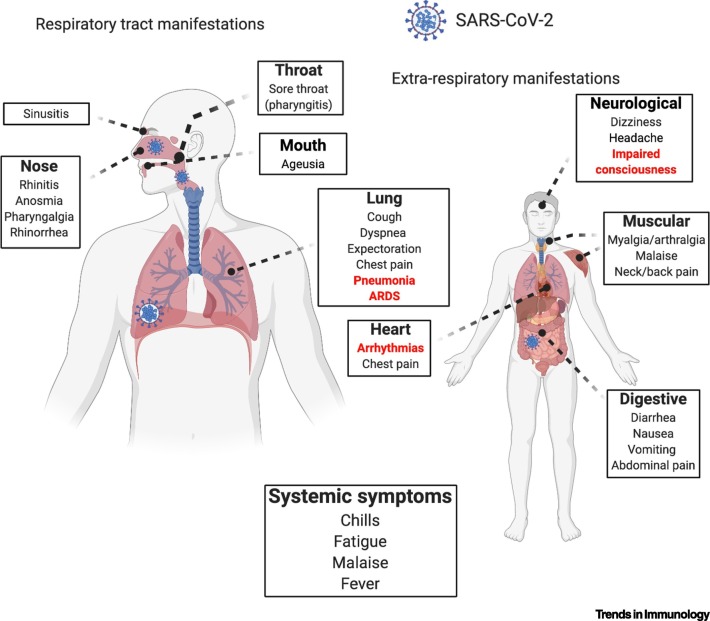

In general, common cold CoVs tend to cause mild URT symptoms and occasional gastrointestinal involvement (Figure 3 ). By contrast, infection with highly pathogenic CoVs, including SARS-CoV-2, causes severe ‘flu’-like symptoms that can progress to acute respiratory distress (ARDS), pneumonia, renal failure, and death [46,48,63,64]. The most common symptoms are fever, cough, and dyspnea, accounting for 83%, 82%, and 31% of patients with COVID-19 (N = 99), respectively, in one epidemiological study [65]. The incubation period in COVID-19 is rapid: ~5–6 days versus 2–11 days in SARS-CoV infections [38,47,48]. As the pandemic is progressing, it has become increasingly clear that COVID-19 encompasses not only rapid respiratory/gastrointestinal illnesses, but can also have long-term ramifications, such as myocardial inflammation [66]. Furthermore, severe COVID-19 is not restricted to the aged population as initially reported; children and young adults are also at risk [67]. From a diagnostic perspective, COVID-19 presents with certain ‘hallmark’ laboratory and radiological indices, which can be helpful in assessing disease progression (Table 1 ). Together, COVID-19 initially presents with ‘flu’-like symptoms and can later progress to life-threatening systemic inflammation and multiorgan dysfunction.

Figure 3.

Clinical Symptoms of Coronavirus Infectious Disease 2019 (COVID-19).

COVID-19 manifestations in humans have been described to incorporate multiple body systems with varying degrees of onset and severity. Both the upper respiratory tract and lower respiratory tract manifestations are often the most noticeable if a patient is not asymptomatic, in addition to systemic symptoms that are the most frequently reported regardless of disease severity. Red-highlighted signs/symptoms tend to be over-represented in severe patients, but common symptoms are also present in more advanced COVID-19. A severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus symbol denotes where a live virus and/or viral RNA has been isolated. Abbreviation: ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome [37,46,48,66,139]. Figure generated with BioRender.

Table 1.

Common Laboratory Indices and Radiological Findings from Patients with COVID-19

| Laboratory findings |

COVID-19 studya |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refs | [65] | [140] | [141] | [137] | [73] | [138] |

| Patient population | Middle-aged, hospitalized; N = 99 | Middle-aged, hospitalized/ICU; N = 1099 | Elderly, mild-severe N = 71 |

Middle-aged, hospitalized adults; N = 140 | Elderly, deceased; N = 82 | Young, mild disease; N = 46 |

| Ground-glass opacities | 14 | 56.4b | 100 | 99.3 | -- | 63 |

| Pneumonia (unilateral or bilateral)c | 100 | 91.1 | 73 | -- | 93.9 | -- |

| Lymphocytopenia | 35 (1.1–3.2 ×109/ml) | 83.2 (<1500/mm3) | 37 (<1200/μl) | 75.4 | 89.2 (<1.0 ×109/l) | 63 (<1.5×109/l) |

| Leukopenia | 9 (3.5–9.5x109/ml) | 33.7 (<4000/mm3) | 21 (<4000/μl) | 19.6 (3.5–9.5×109/ml) | 21.7 (<4×109/l) | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 12 (125–350×109/ml) | 36.2 (<150 000/mm3) | 10 (<15×104/μl) | -- | 24.3 (<100 ×109/l) | 21.7 (<150 ×109/l) |

| Neutrophilia | 38 (1.8–6.3×109/ml) | -- | -- | -- | 74.3 (>6.3 ×109/l) | -- |

| ↑d C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 86 (0–5) | 60.7 (≥10) | 59 (>10–30) | 91.9 (0–3) | 100 (>10) | 19.6 (≥10) |

| ↑ Alanine aminotransferase (U/l) | 28 (9–50) | 21.3 (>40) | 18 (>45) | -- | 30.6 (>40) | 15.2 (>40) |

| ↑ D-dimer (μg/l) | 36 (0–1.5) | 46.4 (≥500) | -- | 43.2 (0–243) | 97.1 (>550) | 15.2 (≥500) |

| ↑ Prothrombin time (s) | 5 (10.5–13.5) | -- | -- | -- | 100 (12.3–14.3)e | -- |

Values for each laboratory manifestation represent the percentage of patients with that clinical finding above or below the normal range (listed below in brackets); dashed lines indicate measurements not taken during referenced study.

Percentage of patients with lung ground-glass opacity on a chest CT scan (technique specifically denoted in original study).

Pneumonia was not always definitively mentioned in studies, albeit lung manifestations were commonly recorded.

↑ denotes an elevation of measured indices above reference value for those percentage of patients

Over the past 24 h, leading up to death, all 13 patients who were included for this metric had a prothrombin time of >12.1 s.

Age-Associated COVID-19 Severity

It is widely accepted that the aging process predisposes individuals to certain infectious diseases [68]. In the case of COVID-19, older age is associated with greater COVID-19 morbidity, admittance to the intensive care unit (ICU), progression to ARDS, higher fevers, and greater mortality rates [69., 70., 71.]. Moreover, lymphocytopenia, neutrophilia, elevated inflammation-related indices, and coagulation-related indicators have been consistently reported in older (≥65-years old) relative to young and middle-aged patients with COVID-19 (Table 1) [46,65,71., 72., 73., 74., 75.]. At the cellular level, a lower capacity of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells to produce IFN-γ and IL-2, as well as an impairment in T-cell activation from dendritic cells (DCs) in patients with acute COVID-19 (≥55-years old) could compromise an optimal adaptive immune response [76]. Based on examples from mice, a productive CD4+ T-cell response relies heavily on lung-resident DCs (rDCs) and abates SARS-CoV infection [77,78]. However, whether a reduction in the DC population in the lungs of older patients with more severe COVID-19 causes suboptimal T-cell activation during SARS-CoV-2 infection remains to be robustly investigated.

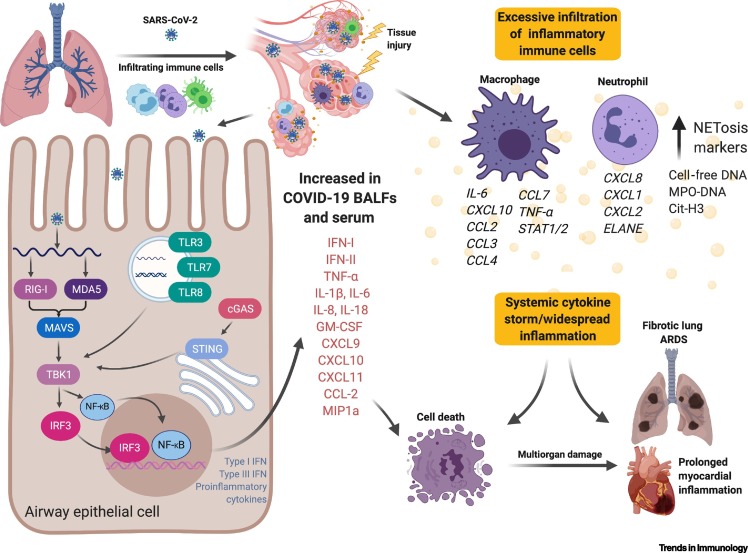

Higher proportions of proinflammatory macrophages and neutrophils have also been observed in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of COVID-19 patients with severe symptoms compared with those exhibiting mild symptoms (Figure 4 , Key Figure) [79]. Accordingly, proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and IL-8) are elevated in the BALF of patients with severe COVID-19, along with higher expression of inflammatory chemokines (e.g., CCL2) in macrophages relative to patients with nonsevere COVID-19 [79., 80., 81., 82.]. Indeed, similar inflammatory milieux have been associated with severe lung pathology in patients with SARS, along with the notable ‘cytokine storm’ that can present in patients critically ill with COVID-19 [71,83., 84., 85., 86., 87.]. These proinflammatory mediators can, in turn, perpetuate lung disease by elevating C-reactive protein (CRP) from the liver (Table 1) through signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)-IL-6 signaling [88]. Therefore, an increase in CRP concentrations can correlate with elevated serum IL-6 production observed in patients with COVID-19 [79,80,88]. From another angle, formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) inside microvessels is pronounced in patients with severe relative to mild COVID-19, implicating NETs as possible potentiators of COVID-19 pathogenesis [89]. The recruitment of these activated neutrophils and monocytes may be driven by pulmonary endothelial cell dysfunction through vascular leakage, tissue edema, endotheliitis, and possibly, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) pathways; indeed, a recent study demonstrated direct SARS-CoV-2 infection of vascular endothelial cells with concomitant accumulation of inflammatory mononuclear cells (e.g., neutrophils) in multiple organs (lung, heart, kidney, small bowel, and liver) in patients with severe COVID-19 (Figure 4) [90]. In fact, many patients with COVID-19 have met the DIC case definition based on elevated serum D-dimer amounts and prolonged prothrombin times [91,92]. Together, it is reasonable to assume that direct viral insult and immune cell recruitment escalate endothelial contractility and the loosening of gap junctions, thus promoting vascular leakage and the systemic impairment of the circulatory system in this pathology.

Figure 4.

Key Figure. A Brief Overview of Lung Pathology in Patients with Coronavirus Infectious Disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Following inhalation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) into the respiratory tract, the virus traverses deep into the lower lung, where it infects a range of cells, including alveolar airway epithelial cells, vascular endothelial cells, and alveolar macrophages. Upon entry, SARS-CoV-2 is likely detected by cytosolic innate immune sensors, as well as endosomal toll-like receptors (TLRs) that signal downstream to produce type-I/III interferons (IFNs) and proinflammatory mediators. The high concentration of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines amplifies the destructive tissue damage via endothelial dysfunction and vasodilation, allowing the recruitment of immune cells, in this case, macrophages and neutrophils. Vascular leakage and compromised barrier function promote endotheliitis and lung edema, limiting gas exchange that then facilitates a hypoxic environment, leading to respiratory/organ failure. The inflammatory milieu induces endothelial cells to upregulate leukocyte adhesion molecules, thereby promoting the accumulation of immune cells that may also contribute to the rapid progression of respiratory failure. Hyperinflammation in the lung further induces transcriptional changes in macrophages and neutrophils that perpetuate tissue damage that ultimately leads to irreversible lung damage. Recent evidence suggests that systemic inflammation induces long-term sequela in heart tissues [66,79,80,82,84,87,90,95]. Abbreviations: BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; IRF3, interferon regulatory factor 3; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; RIG-I, retinoic acid-inducible gene I; STAT1/2, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1/2; STING, Stimulator of interferon genes. Figure generated with BioRender.

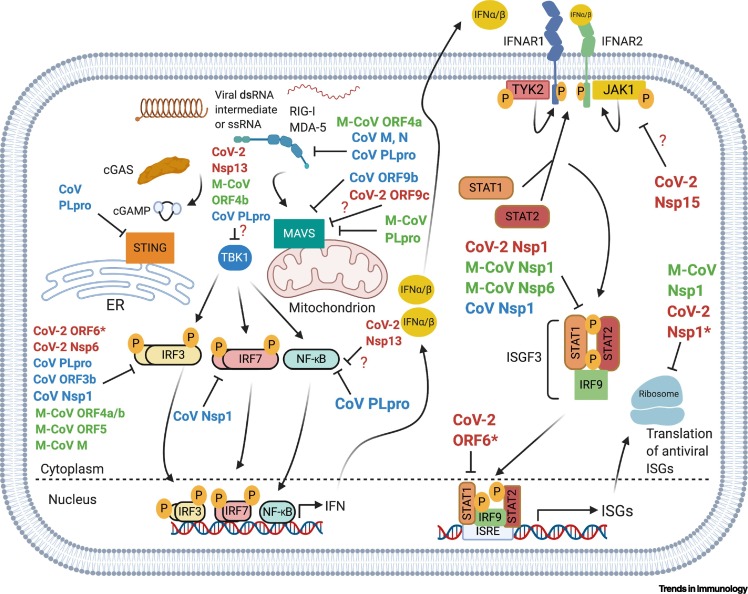

SARS-CoV-2 Innate Immune Evasion Strategies: Examples from other Betacoronavirus Infections

The recognition of virus infection begins with the detection of viral nucleic acid by host cell pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which signal downstream via recruited adaptor proteins, ubiquitin ligases, and kinases, culminating in transcription factors and ultimate expression of immune genes, including IFNs, cytokines, and chemokines (Figure 5 ). The IFN pathway is often a primary target of evasion due to its rapidity and potency in eliminating viral infection. CoVs have evolved multiple mechanisms to target the signaling components of several PRR-IFN pathways to survive in host cells (Figure 5). CoVs are highly sensitive to IFN and, therefore, act at several levels in these pathways to antagonize mammalian immune recognition, interfering with downstream signaling, or inhibiting specific IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) products [93]. Specifically, CoVs can avoid immune sensing by: (i) the formation of DMVs that sequester viral nucleic acid from being recognized by PRRs; and (ii) direct ablation of the functionality of immune signaling molecules by viral proteins [11,94]. The structural and functional conservation of these proteins across the Betacoronavirus and in nsps between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 suggest that some of these suppressive mechanisms are used by SARS-CoV-2 (see later) [1]. Indeed, patients with severe COVID-19 have reported an imbalanced immune response with high concentrations of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, but little circulating IFN-β or IFN-λ, resulting in persistent viremia [95]. Of note, among several respiratory viruses tested, SARS-CoV-2 has demonstrated to most potently suppress type I and type III IFN expression in both human bronchial epithelial cells and ferrets [81]. Thus, evasion of IFN signaling by SARS-CoV-2 and impaired IFN production in human peripheral blood immune cells might contribute to the productive viral replication, transmission, and severe pathogenesis during COVID-19, although further testing is warranted to fully dissect these putative evasion pathways [95].

Figure 5.

Evasion of the Pattern Recognition Receptor-Type I Interferon (PRR-IFN-I) Pathways by Coronaviruses (CoVs).

A simplified schematic of the canonical IFN response after sensing RNA viruses. Viral nucleic acid is first recognized by PRRs (e.g., retinoic acid-inducible gene I; RIG-I) that perpetuate signal transduction through an adaptor complex on the mitochondrial (mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein; MAVS) or endoplasmic reticulum (Stimulator of interferon genes; STING) membrane surface. Here, the PRR–adaptor interactions recruit kinases that converge into a large complex, leading to phosphorylation of interferon regulatory factor 3/7 (IRF3/7) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), transcription factors that enter the nucleus and transcribe IFN genes. Type-I and type-III IFNs then signal in an autocrine or paracrine manner through the Janus kinase 1 (JAK1)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 and 2 (STAT1/2) pathway, culminating in antiviral IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) transcription. Listed here are SARS-CoV (CoV), SARS-CoV-2 (CoV-2), and MERS-CoV (M-CoV) IFN-I antagonists, which render these viruses resistant to IFN responses. IFN-III is also implicated in exhibiting potent antiviral effects in lung/intestinal tissues, but the underlying evasion strategies of this pathway for these viruses are currently unknown. SARS-CoV proteins are highlighted in blue, while functions of SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV proteins are highlighted in red and green, respectively. ? denotes that a SARS-CoV-2 protein bound a member of that signaling pathway in [122], but further work is necessary to confirm its immunological mechanism. SARS-CoV-2 proteins with * denotes functional conservation with SARS-CoV [93., 94., 95., 96.,98,100., 101., 102., 103., 104., 105., 106., 107.]. Figure generated with BioRender.

With regard to functional conservation of viral proteins, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV nsps and accessory proteins circumvent viral RNA-sensing pathways at multiple stages [e.g., retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5; MDA-5) through proteasomal degradation and/or prevention of protein activation (Figure 5) [94]. Functional conservation between SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV PLpro (encoded by nsp3) proteins has been reported, where these proteins target the initial PRR signaling cascade at multiple levels of the pathway including, but not limited to, RIG-I, mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS), TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), and nuclear factor (NF)-κB (Figure 5) [96., 97., 98.]. The SARS-CoV PLpro also targets the DNA-sensing pathway at Stimulator of IFN genes (STING) (Figure 5); antagonizing this pathway might be important because mitochondrial stress during dengue virus infection triggers IFN-β production that is dependent on STING activation [99,100]. Recent evidence suggests the SARS-CoV-2 PLpro also inhibits IFN-I expression in human kidney epithelial cells, yet the mechanisms remain to be defined [101]. Moreover, nsp1 of highly pathogenic HCoVs, including SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, displays a pleiotropic effect, targeting several components of IFN-I signaling (Figure 5) [102,103]. This potent suppressive function of nsp1 also appears to be maintained in SARS-CoV-2, primarily through shutdown of translational machinery and prevention of immune gene expression [101,104,105]. Furthermore, because there are only five accessory genes in the MERS-CoV genome compared with eight and seven in the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 genomes, respectively, similar immunosuppressive mechanisms may exist but appear to be mediated via different proteins [106,107]. For example, SARS-CoVs ORF6 can inhibit IRF3 activation and STAT1 nuclear translocation, whereas this same effect is obtained by ORF4a/b and ORF5 of MERS-CoV (Figure 5) [106,107]. Coincidently, the apparent loss of these proteins may provide evidence for why MERS-CoV is more sensitive to IFN treatment than are SARS-CoVs in primary and continuous cells of the human airways [110]. The SARS-CoV-2 proteins appear to have stronger inhibitory effects than their counterparts in highly pathogenic SARS- and MERS-CoV [105]. In light of these findings, SARS-CoV-2 has replicated more efficiently than SARS-CoV in ex vivo human lung explants, possibly through the greater suppression of IFN-I/III cytokines [111]; further work will be needed to discern whether the suppressive nature of SARS-CoV-2 can impact virus transmission during early phases of COVD-19, when IFNs are typically important for virus control. The ‘common-cold’ CoVs (e.g., HCoV-229E) and murine hepatitis virus (MHV) also compensate for the loss of many supplementary immunosuppressive proteins through capping viral mRNAs via nsp16 2′-O-methyltransferase (2′-O-MTase), and mutants lacking this activity exhibit diminished replication and dissemination in mice [112]. Thus, further investigation is warranted to determine whether these evasion genes account for the increased virulence observed in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 (see Outstanding Questions).

Animal Models of SARS-CoV-2

Mouse Models

Given that SARS-CoV-2 uses the same ACE2 entry receptor as SARS-CoV, rapid deployment of mouse models for pathogenesis studies was well underway within weeks of the inception of the pandemic. However, various impediments remain for SARS-CoV-2 in productively infecting mice in these models, because it is unable to bind mouse ACE2 (mACE2) [113]. To overcome these prerequisites, several mouse models have been developed that recapitulate certain components of human COVID-19. One of these strategies is to genetically modify mice to express human ACE2 (hACE2) (humanized mice) under the epithelial cell-specific cytokeratin-18 (Krt 18) promoter [114], a universal chicken beta-actin promoter [115], or the endogenous mACE2 promoter [113]. All these mice are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, but phenotypic disease varies because of differential hACE2 tissue expression [113., 114., 115.]. For instance, Krt18-hACE2 and beta-actin-hACE2-transgenic mice rapidly succumb to SARS-CoV-2 infection with lung infiltration of inflammatory immune cells inducing severe pulmonary disease, accompanied by evident thrombosis and anosmia, which partially recapitulate human COVID-19 [116,117]. Given that the onset of severe histopathological changes occurs days after peak virus infection, these models recapture the delayed morbidity seen in patients with COVID-19 as a result of inflammatory cell infiltration [117]. Therefore, using humanized mouse models of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection might be useful for testing the efficacy of antiviral drugs, vaccines, and immune therapeutics that ablate hyperinflammation [116]. However, the broad expression of hACE2 in these models significantly expands SARS-CoV-2 tissue tropisms and might alter its pathogenic mechanisms [116,117]. For example, both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 infections lead to encephalitis in these mouse models, which is not common in patients with COVID-19 [115,117,118]. Given that most human SARS-CoV-2 infections are asymptomatic or mild, mice originally bearing mACE2 that is replaced by hACE2 may be more appropriate for assessing pathogenesis and tissue tropism [113]. This model develops mild lung pathology, with SARS-CoV-2 infection being restricted to the lung and intestine [113]. In addition to the transgenic modification, mice can also be sensitized to SARS-CoV-2 infection via transient transduction of adenovirus (Ad5)- or adeno-associated virus (AAV)-expressing hACE2 in respiratory tissues, akin to the approach used for MERS-CoV infection [108,109]. These mice develop viral pneumonia, weight loss, severe pulmonary pathology, and a high viral load in the lung, consistent with human COVID-19 [109]. This approach might be quickly adapted to many genetically modified mouse strains that could provide mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis and protective immune responses. However, this model is limited by the transient ectopic expression of hACE2 from the Ad5/AAV vector that can induce mild bronchial inflammation and expand cell tropism of SARS-CoV-2 and, thus, alter disease pathogenesis [119].

Rather than genetic modification in host animals, viruses can also be genetically modified and used in model animals [120,121]. For instance, in one study, serial passaging of SARS-CoV-2 in mice led to enrichment of a N501Y viral mutant that elicited interstitial pneumonia and inflammatory responses in both young and aged wild-type BALB/c mice [122]. Another mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 strain (MA10) carrying three mutations in the RBD of Spike protein caused severe lung pathology and ARDS in mice, characteristic of severe COVID-19 [123]. Despite the three mutations in the RBD of the mouse-adapted Spike, vaccination with full-length SARS-CoV-2 Spike elicited robust neutralizing antibody titers and complete protection against a secondary challenge with MA10 [123]; these findings suggest that this strain is applicable to pathogenesis studies, as well as antiviral drug and vaccine testing in rodents.

Nonhuman Primate Models

The role of nonhuman primates (NHP) in evaluating coronavirus pathogenesis cannot be understated. Depending on the NHP model utilized, clinical signs/symptoms may be mild or absent entirely [124., 125., 126.]. In rhesus macaques, several studies noted reduced appetite, transient fevers (1 day post infection: dpi) and mild weight loss without overt signs of respiratory distress or mortality [124., 125., 126.]. By contrast, cynomolgus macaques did not display any observational signs of disease in another study [125]. Although certain NHPs appear to only mimic mild disease (if any), rhesus macaques have exhibited high viral loads in nasal swabs, throat samples, and BALF early post inoculation, and viral RNA was still measurable by quantitative (q)PCR in the trachea and lung 21 dpi, highlighting the apparent tropism of SARS-CoV-2 for the URT and lingering viral nucleic acid in respiratory tissues after resolution of disease [51,124]. SARS-CoV-2 has also been detected in nasal swabs at 10 dpi in NHPs, consistent with the prolonged URT shedding of virus in patients with COVID-19 at ~9 dpi [51,124,125,127]. The tropism of SARS-CoV-2 for the LRT in NHPs has also been recapitulated by the development of multifocal lesions and interstitial pneumonia, supporting the hypothesis that lung injury is driven by increased infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages into the lung following viral infection [124., 125., 126.].

However, additional hallmarks of severe disease are absent in NHPs, particularly the characteristic systemic ‘cytokine storm’ present in patients with COVID-19; indeed, only transient elevations of serum inflammatory cytokines have been observed in NHPs, and have been reported to decline rapidly by 2 dpi [124]. Overall, these NHP models display mild disease accompanied by viral dissemination in the URT and LRT, leading to localized lung inflammation, but devoid of the sustained systemic inflammatory response that has been noted in patients with COVID-19. Thus, NHP models might be useful for studying mild COVID-19 characteristics, but provide little information on the pathogenic mechanism(s) of severe COVID-19. To partially overcome this issue, aged rhesus macaques (15-years old) have been tested following SARS-CoV-2 infection and have demonstrated shedding of the virus for longer periods of time (14 days), as well as increased radiological and histopathological changes, such as thickened alveolar septum and diffuse severe interstitial pneumonia, compared with young macaques (3–5-years old) [128]. Therefore, these studies highlight the importance of also considering age, as an additional variable, when selecting animal models that might closely, or accurately, recapitulate human disease.

Evaluating efficacious vaccine candidates in NHPs will also be important for understanding correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2. Accordingly, reports of antibody-dependent enhancement, as well as of non-neutralizing humoral responses to the conserved regions of SARS-CoV-2, raise concerns on our future ability to effectively administer an immunogen without inducing immunopathology [129,130]. Furthermore, upon viral challenge, lymphocytes have expanded in rhesus macaque models around 5 dpi with complementary B cell responses against SARS-CoV-2 Spike appearing 10–15 dpi in blood samples [124]; expansion of these adaptive immune compartments was analogous to those observed in patients with COVID-19 [37,124,131., 132., 133.]. Subsequent rechallenged rhesus macaque have presented a rapid anamnestic immune response characterized by significantly higher neutralizing antibody (NAb) titers compared with the primary infection macaques [126]. Thus, protective efficacy appears to depend primarily on NAb titers, at least in NHPs; so far, T-cell numbers have not substantially increased in the serum following rechallenge of these animals and, in a secondary study, CD4+ and CD8+ cytokine (e.g., IFN- γ) responses did not correlate with immune protection from DNA vaccines with different components of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein [126,134]. Although these animals have failed to manifest overt signs of infection and respiratory compromise, NHPs still represent the ‘gold standard’ for evaluating the protective efficacy of human-bound SARS-CoV-2 vaccines based on parallels to humans in terms of viral tropism, immunopathology, and correlates of protection [126]. Further research is urgently needed to explore the durability of immune responses to SARS-CoV-2, considering reports of waning immunity to other CoVs and the detection of pre-existing cross-reactive ’common-cold‘ CoV T-cells with SARS-CoV-2 in naïve humans (see Outstanding Questions) [135,136].

Concluding Remarks

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 as the most recent example of zoonotic virus spillovers into humans underscores the fundamental need for well-funded surveillance organizations. The unrivaled spread of SARS-CoV-2 urgently demands that the global science community acts in harmony to disseminate accurate and stipulatory knowledge, with an immediate potential to influence policy and public health strategies/interventions at the national and local levels. Studies stemming from previous CoVs have jumpstarted our basic understanding of SARS-CoV-2 biology and facilitated the rapid deployment of vaccine candidates into clinical trials. Although clinical symptoms of COVID-19 resemble some aspects of SARS and MERS, respectively, distinct and significant disparities exist in the transmissibility and immune responses to SARS-CoV-2. To modify therapeutics that protect against the full spectrum of disease (see Outstanding Questions), additional research will need to define the molecular mechanisms contributing to severe immunopathology in some patients, whereas others are completely protected from clinical symptoms. Prior work involving other CoVs, together with current and future studies of SARS-CoV-2, should provide society with the foundational knowledge to prepare for expected seasonal resurgences of SARS-CoV-2, as well as any potential spillover of additional CoVs into human populations; hopefully, current investigations will make important advances and contribute to increased knowledge and preparedness in this regard.

Outstanding Questions.

Which animal(s) serves as the natural reservoir of SARS-CoV-2?

Does active replication of SARS-CoV-2 in the URT contribute to enhanced transmissibility in humans?

Is intestinal SARS-CoV-2 infection a source of virus transmission?

Which SARS-CoV-2 proteins antagonize innate and adaptive immune responses? Do the SARS-CoV-2 proteins with more potent antagonistic immune functions increase virulence in humans compared with other HCoVs? Why do some recovered patients fail to develop neutralizing antibodies?

What are the host and/or viral factors driving inflammatory imbalances in severe COVID-19 cases?

What are the underlying mechanisms contributing to an inadequate IFN response to SARS-CoV-2?

What are the correlates of immune protection for SARS-CoV2 and will they provide sterilizing immunity?

Will candidate vaccines against SARS-CoV2 also be effective in older subpopulations (with or without comorbidities)?

Alt-text: Outstanding Questions

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant R01AI132526 to P.W.

Glossary

- Aerosol

suspension of fine solid or liquid droplets in the air (or a gas medium), such as dusts, mists, or fumes.

- Anamnestic immune response

memory immune response to a previously encountered antigen.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)

cell surface enzyme of endothelial, epithelial, and other cells, with a well-defined function in maintaining normal blood pressure.

- Anosmia

partial or complete loss of the sense of smell.

- Antibody-dependent enhancement

phenomenon by which antibodies against a virus are suboptimal to the virus and enhance its entry into host cells.

- Correlates of protection

quantifiable parameters, such as antibodies, indicating that a host is protected against microbial infection.

- Cytokine storm

severe immune reaction in which the body releases too many cytokines into the blood too quickly.

- D-dimer

fibrin degradation product in the blood after a clot is degraded by fibrinolysis.

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

condition in which blood clots form throughout the body and block small blood vessels, leading to multiorgan failure.

- Fecal-oral transmission

route of disease transmission by which an infectious agent in fecal materials is passed to the mouth of another.

- Fomite

inanimate object (clothes, utensil, furniture, etc.) that, when contaminated with an infectious agent, can transfer the infectious agent to a new host.

- Furin

proprotein convertase that cleaves a precursor protein into a biologically active state.

- Incubation period

timeframe elapsed between when a host is first exposed to an infectious agent and when signs or symptoms begin to appear.

- Lung ground glass opacity

nonspecific radiological description of an area of increased opacity in the lung through which vessels and bronchial structures are still visible.

- Neutralizing antibody (NAb)

antibody that binds a pathogen with high affinity and prevents the latter from exerting its biological effect.

- Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)

networks of extracellular fibers, comprising primarily DNA from neutrophils due to chromatin decondensation, which can ‘trap’ extracellular pathogens.

- Pattern recognition receptor

germline-encoded host sensor that recognizes a signature pattern in microbial molecules.

- Prodromal period

time immediately following the incubation period of a microbial infection in which a host begins to experience symptoms or changes in behavior/functioning.

- Prothrombin time

measurement of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation.

- Reproductive number (R0)

expected number of new disease cases generated by one case. R0 >1 indicates that the outbreak will expand; R0 <1 indicates that the outbreak will die out.

- Respiratory droplet

small aqueous droplet produced by exhalation, comprising saliva or mucus and other matter derived from respiratory tract surfaces.

- Zoonotic disease

infectious disease caused by a pathogen that has crossed a species barrier from animals to humans.

References

- 1.Zhou P. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peiris J. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . WHO; 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorbalenya A.E. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu R. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y.Z., Holmes E.C. A genomic perspective on the origin and emergence of SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2020;181:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlman S., Netland J. Coronaviruses post-SARS: update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:439–450. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu F. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann M. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snijder E.J. Ultrastructure and origin of membrane vesicles associated with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication complex. J. Virol. 2006;80:5927–5940. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02501-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu H.-Y., Brian D.A. Subgenomic messenger RNA amplification in coronaviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:12257–12262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000378107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peiris J. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361:1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wrapp D. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan R. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367:1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shang J. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:11727–11734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2003138117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmann M. A multibasic cleavage site in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for infection of human lung cells. Mol. Cell. 2020;78:779–784. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yurkovetskiy L. Structural and functional analysis of the D614G SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variant. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.032. Published online September 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q. The impact of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 spike on viral infectivity and antigenicity. Cell. 2020;182:1284–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korber B. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020;182:812–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jia H.P. ACE2 receptor expression and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection depend on differentiation of human airway epithelia. J. Virol. 2005;79:14614–14621. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14614-14621.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamming I. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 2004;203:631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuba K. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat. Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ziegler C.G.K. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell. 2020;181:1016–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun K. Atlas of ACE2 gene expression in mammals reveals novel insights in transmission of SARS-CoV-2. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.30.015644. Published online March 31, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shulla A. A transmembrane serine protease is linked to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor and activates virus entry. J. Virol. 2011;85:873–882. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02062-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Y. Single-cell RNA expression profiling of ACE2, the receptor of SARS-CoV-2. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020;202:756–759. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202001-0179LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imai Y. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S. Endocytosis of the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV spike protein together with virus receptor ACE2. Virus Res. 2008;136:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith J.C. Cigarette smoke exposure and inflammatory signaling increase the expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in the respiratory tract. Dev. Cell. 2020;53:514–529. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Follis K.E. Furin cleavage of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein enhances cell-cell fusion but does not affect virion entry. Virology. 2006;350:358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukassen S. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are primarily expressed in bronchial transient secretory cells. EMBO J. 2020;39 doi: 10.15252/embj.20105114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hui K.P.Y. Tropism, replication competence, and innate immune responses of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 in human respiratory tract and conjunctiva: an analysis in ex-vivo and in-vitro cultures. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30193-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.COVID-19 Investigation Team Clinical and virologic characteristics of the first 12 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States. Nat. Med. 2020;26:861–868. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0877-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu H. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020;12:8. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wölfel R. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su S. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H. The digestive system is a potential route of 2019-nCov infection: a bioinformatics analysis based on single-cell transcriptomes. Gut. 2020;69:1010–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cholankeril G. High prevalence of concurrent gastrointestinal manifestations in patients with SARS-CoV-2: early experience from California. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:775–777. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiao F. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–1833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leung W.K. Enteric involvement of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus infection. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu I.T.S. Evidence of airborne transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:1731–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Otter J.A. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: the possible role of dry surface contamination. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016;92:235–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y. Role of air distribution in SARS transmission during the largest nosocomial outbreak in Hong Kong. Int. J. Indoor Environ. Health. 2004;15:83–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang D. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Q. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chan J.F.W. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferrett L. Quantifying SARS-CoV-2 transmission suggests epidemic control with digital contact tracing. Science. 2020;368 doi: 10.1126/science.abb6936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arons M.M. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zou L. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pan Y. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:411–412. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mizumoto K. Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meng Heng. CT imaging and clinical course of asymptomatic cases with COVID-19 pneumonia at admission in Wuhan, China. J. Infect. 2020;81:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rothe C. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He G. The clinical feature of silent infections of novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in Wenzhou. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:1761–1763. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mukhra R. Possible modes of transmission of novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: a review. Acta Biomed. 2020;91 doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i3.10039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tomlinson B., Cockram C. SARS: experience at Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong. Lancet. 2003;361:1486–1487. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13218-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Y. Aerodynamic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in two Wuhan hospitals. Nature. 2020;582:557–560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doremalen N.v. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ong S.W.X. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. JAMA. 2020;323:1610–1612. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu Y. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat. Med. 2020;26:502–505. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ksiazek T.G. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guery B. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet. 2013;381:2265–2272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen N. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Puntmann V.O. Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557. Published online July 27, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chao J.Y. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized and critically ill children and adolescents with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at a tertiary care medical center in New York City. J. Pediatr. 2020;223:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nikolich-Zugich J. The twilight of immunity: emerging concepts in aging of the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:10–19. doi: 10.1038/s41590-017-0006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu J.T. Estimating clinical severity of COVID-19 from the transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China. Nat. Med. 2020;26:506–510. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0822-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chow R.D., Chen S. The aging transcriptome and cellular landscape of the human lung in relation to SARS-CoV-2. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.07.030684. Published online April 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang X. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Imai S.T.K. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in 104 people with SARS-CoV-2 infection on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:1043–1050. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30482-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang B. Clinical characteristics of 82 cases of death from COVID-19. PLoS ONE. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu C. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020;180:7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu K. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: a comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J. Infect. 2020;80:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou R. Acute SARS-CoV-2 infection impairs dendritic cell and T cell responses. Immunity. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.026. Published online August 4, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen J. Cellular immune responses to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infection in senescent BALB/c mice: CD4+ T cells are important in control of SARS-CoV infection. J. Virol. 2010;84:1289–1301. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01281-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao J. Evasion by stealth: inefficient immune activation underlies poor T cell response and severe disease in SARS-CoV-infected mice. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liao M. Single-cell landscape of bronchoalveolar immune cells in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0901-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Qin C. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:762–768. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blanco-Melo D. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181:1036–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen H. SARS-CoV-2 activates lung epithelia cell proinflammatory signaling and leads to immune dysregulation in COVID-19 patients by single-cell sequencing. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.08.20096024. Published online May 13, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ding Y. The clinical pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a report from China. J. Pathol. 2003;200:282–289. doi: 10.1002/path.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nicholls J.M. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1773–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ruan, Q. et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 46, 846-848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Moore J.B., June C.H. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19. Science. 2020;368:473–474. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Channappanavar R., Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017;39:529–539. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0629-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marnell L. C-reactive protein: ligands, receptors and role in inflammation. Clin. Immunol. 2005;117:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zuo Y. Neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. JCI Insight. 2020;5 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.138999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Varga Z. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhou F. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tang N. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Totura A.L., Baric R. SARS coronavirus pathogenesis: host innate immune responses and viral antagonism of interferon. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2:264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kindler E. Interaction of SARS and MERS coronaviruses with the antiviral interferon response. Adv. Viral Res. 2016;96:219–243. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hadjadj J. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Sci. Immunol. 2020;369:718–724. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Devaraj S.G. Regulation of IRF-3 dependent innate immunity by the Papain-like protease domain of the SARS coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:32208–32221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704870200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Frieman M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus papain-like protease ubiquitin-like domain and catalytic domain regulate antagonism of IRF3 and NF-κB signaling. J. Virol. 2009;83:6689–6705. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02220-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bailey-Elkin B.A. Crystal structure of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) papain-like protease bound to ubiquitin facilitates targeted disruption of deubiquitinating activity to demonstrate its role in innate immune suppression. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:34667–34682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.609644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Aarreberg L.D. Interleukin-1β induces mtDNA release to activate innate immune signaling via cGAS-STING. Mol. Cell. 2019;74:801–815. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sun L. Coronavirus papain-like proteases negatively regulate antiviral innate immune response through disruption of STING-mediated signaling. PLoS ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lei X. Activation and evasion of type I interferon responses by SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3810. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17665-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lokugamage K.G. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus protein nsp1 is a novel eukaryotic translation inhibitor that represses multiple steps of translation initiation. J. Virol. 2012;86:13598–13608. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01958-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lokugamage K.G. Middle East Respiratory syndrome coronavirus nsp1 inhibits host gene expression by selectively targeting mRNAs transcribed in the nucleus while sparing mRNAs of cytoplasmic origin. J. Virol. 2015;89:10970–109981. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01352-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Thoms M. Structural basis for translational shutdown and immune evasion by the Nsp1 protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;369:1249–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.abc8665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xia H. Evasion of type-I interferon by SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2020;33 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yang Y. The structural and accessory proteins M, ORF 4a, ORF 4b, and ORF 5 of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) are potent interferon antagonists. Protein Cell. 2013;4:951–961. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-3096-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kopecky-Bromberg S.A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus open reading frame (ORF) 3b, ORF 6, and nucleocapsid proteins function as interferon antagonists. J. Virol. 2007;81:548–557. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01782-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhao J. Rapid generation of a mouse model for Middle East respiratory syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:4970–4975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323279111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sun Jing. Generation of a broadly useful model for COVID-19 pathogenesis vaccination, and treatment. Cell. 2020;182:734–743. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zielecki F. Human cell tropism and innate immune system interactions of human respiratory coronavirus EMC compared to those of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 2013;87:5300–5304. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03496-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chu H. Comparative replication and immune activation profiles of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV in human lungs: an ex vivo study with implications for the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:1400–1409. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Züst R. Ribose 2′-O-methylation provides a molecular signature for the distinction of self and non-self mRNA dependent on the RNA sensor Mda5. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:137–143. doi: 10.1038/ni.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bao L. The pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 in hACE2 transgenic mice. Nature. 2020;583:830–833. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2312-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.McCray P.B. Lethal infection of K18-hACE2 mice infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 2007;81:813–821. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02012-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tseng C.-T.K. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection of mice transgenic for the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 virus receptor. J. Virol. 2007;81:1162–1173. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01702-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zheng J. K18-hACE2 mice for studies of COVID-19 treatments and pathogenesis including anosmia. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.07.242073. Published online August 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Winkler E.S. SARS-CoV-2 infection of human ACE2-transgenic mice causes severe lung inflammation and impaired function. Nat. Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0778-2. Published online August 24, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Netland J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J. Virol. 2008;82:7264–7275. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00737-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wold W.S., Toth K. Adenovirus vectors for gene therapy, vaccination and cancer gene therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2013;13:421–433. doi: 10.2174/1566523213666131125095046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Roberts A. A mouse-adapted SARS-coronavirus causes disease and mortality in BALB/c mice. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Dinnon K.H. A mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 model for the evaluation of COVID-19 medical countermeasures. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2708-8. Published online August 27, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gordon D.E. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature. 2020;583:459–468. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Leist S.R. A mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 induces acute lung injury (ALI) and mortality in standard laboratory mice. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.050. Published online September 23, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Munster V.J. Respiratory disease in rhesus macaques inoculated with SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;585:268–272. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2324-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rockx B. Comparative pathogenesis of COVID-19, MERS, and SARS in a nonhuman primate model. Science. 2020;368:1012–1015. doi: 10.1126/science.abb7314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chandrashekar A. SARS-CoV-2 infection protects against rechallenge in rhesus macaques. Science. 2020;369:812–817. doi: 10.1126/science.abc4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lawler J.V. Cynomolgus macaque as an animal model for severe acute respiratory syndrome. PLoS Med. 2006;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Yu P. Age-related rhesus macaque models of COVID-19. Anim. Models Exp. Med. 2020;3:93–97. doi: 10.1002/ame2.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tseng C.-T. Immunization with SARS coronavirus vaccines leads to pulmonary immunopathology on challenge with the SARS virus. PLoS ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Liu L. Anti-spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection. JCI Insight. 2019;4 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhao J. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. Published online March 28, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Long Q.X. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26:845–848. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mathew D. Deep immune profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals distinct immunotypes with therapeutic implications. Science. 2020;369 doi: 10.1126/science.abc8511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]