Abstract

Purpose

We evaluated the geometric and dosimetric-based distribution of mucosal and nodal recurrences in patients with metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma to cervical lymph nodes of unknown primary after intensity modulated radiation therapy using validated typology-indicative taxonomy.

Methods and Materials

We reviewed the data of 260 patients who were irradiated between 2000 and 2015 and had a median follow-up time for surviving patients of 61 months. The mucosal and nodal recurrences were manually delineated on computed tomography images demonstrating the recurrences. The images were overlaid on the treatment plan using deformable image registration. The locations of the recurrences were determined relative to the original planning target volumes and doses using centroid-based approaches. Subsequently, the pattern of failures were classified into 5 types based on combined spatial and dosimetric criteria: A (central high dose), B (peripheral high dose), C (central elective dose), D (peripheral elective dose), and E (extraneous dose). For patients with type A failure with simultaneous nontype A lesions, the overall pattern of failures was defined as type A.

Results

Thirty-two patients had mucosal or nodal recurrences. The most common clinical nodal stage was N2b (66%). Preradiation therapy neck dissections were performed in 6 patients. The median dose delivered to clinical tumor volume 1 was 66 Gy. The majority (84%) had total/partial pharyngeal mucosa elective irradiation. Twenty-three patients had nodal recurrences, 8 had mucosal recurrences, and 1 had both nodal and mucosal recurrences. Twenty-one patients (91%) had type A nodal failure, and 7 of the mucosal failures (89%) were type C.

Conclusions

The majority of nodal recurrences occurred within the high-dose area, demanding the need for identification of radioresistant areas within malignant nodes. Future studies should focus on either dose escalation of high-risk volumes or novel radiosensitizers.

Introduction

Metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma to cervical lymph nodes of unknown primary (HN-SCCUP) is an uncommon disease1 with no treatment consensuses owing to the lack of randomized trials. Research efforts have focused on the identification of patient- and tumor-related prognostic factors (ie, age, nodal disease burden, and pathologic grading).2, 3, 4 However, multi-institutional collaborations and large-volume studies are needed to optimize treatment plans, explore molecular biomarkers (eg, human papilloma virus/p16 status),5 and use the currently available image modalities6 to improve treatment outcomes of HN-SCCUP.

Currently, (chemo) radiation therapy (RT) alone or in combination with surgery is the upfront approach to manage HN-SCCUP. However, the sequence, the extent of irradiated volumes, and the optimal curative RT dose are still controversial.7,8 Although intensity modulated RT (IMRT) results in excellent rates of nodal control and disease-free survival,9,10 nodal and mucosal recurrences still occur.4,11,12 Comprehensive insight into the pattern of failure (POF) is restricted due to cohort heterogeneity and the small sample size of most studies.4,11,13,14 Additionally, the absence of validated image registration methods and failure typology that take into account the dose grid distribution are major limitations.

Consequently, our current analysis aims to map the POF, using a validated typology-indicative taxonomy15 among a large cohort of patients with HN-SCCUP treated by curative-intent IMRT at UT-MD Anderson Cancer Center. The specific aims of the current study are to evaluate the geometric- and dosimetric-based distribution of mucosal and regional recurrences in patients with HN-SCCUP using validated typology-indicative taxonomy and correlate the individual POF with patient-, tumor-, and treatment-related characteristics.

Methods and materials

Participants

Medical records of 260 patients with HN-SCCUP treated with curative IMRT at UT-MD Anderson Cancer Center between 2000 and 2015 were retrospectively reviewed under an approved institutional review board protocol, and overall outcomes were reported.10 The median follow-up time for surviving patients was 61 months (range, 0-176 months). Detailed images and plans data were retrieved for patients with evidence of mucosal or regional recurrences. Patients were excluded if either their original treatment plans or imaging of their recurrences were not available.

Intensity modulated radiation therapy treatment characteristics

IMRT was delivered using a linear accelerator producing 6 MV photons. The initial IMRT planning system, Corvus system (North American Scientific, Inc, Cranberry Township, PA) was used from 2000 to 2003. In 2003, we transitioned to the Pinnacle planning system (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA).

Treatment was delivered with a static gantry approach. The IMRT fields generally consisted of 9 static gantry beams with the following angles: 0, 40, 80, 120, 160, 200, 240, 280, and 320 for patients treated to both sides of the neck and 7 beams equidistant through a 190° arc for patients treated to only 1 side of the neck. No patient was treated with volumetric modulated arc therapy. General treatment strategies included defining 3 clinical target volumes (CTVs): CTV1 (which included gross nodal disease with a margin, or in postoperative situations the preoperative tumor bed with margin), CTV2 (neck volume at high risk of harboring microscopic disease but without clinical, radiographic, or pathologic evidence of nodal disease), and CTV3 (nodal volume and mucosa deemed at low risk of harboring subclinical disease).

Image collection and dosimetric characteristics

The diagnostic CT scans showing the first evidence of recurrence were collected. All recurrences were confirmed by histopathologic examination. Recurrent gross mucosal/nodal volumes were manually delineated on follow-up images that demonstrated the recurrences. The planning CT scans and RT plans were retrieved. The images were overlaid on the treatment plan using deformable image registration (VelocityAI 3.0.1, Velocity Medical Solutions, Atlanta, GA, 2004-2013).16

Pattern of failure classification

Recurrent gross mucosal/nodal volumes were determined relative to the original planning target volumes and dose using a centroid-based approach. Subsequently, the POFs were classified into 5 types based on combined spatial and dosimetric criteria previously validated:15 A (central high dose), B (peripheral high dose), C (central elective dose), D (peripheral elective dose), and E (extraneous dose). For patients with type A failure with simultaneous nontype A lesions, the overall POF was defined as type A.

Results

Patient and treatment characteristics

The actuarial 5-year neck control, distant metastases-free survival, and overall survival rates were 91%, 94%, and 84%, respectively. Fifty-five patients (21%) were dead at the time of analysis. Thirty-two patients with either neck or mucosal recurrences were included in the cohort of the current analysis. The most common clinical nodal stage (American Joint Committee on Cancer, seventh edition) was N2b (66%), followed by N2c and N3 (9% and 19%, respectively). Human papilloma virus/p16 status was positive in 8, negative in 7, and missing in 17 patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | All patients (N = 260) no. (%) |

Patients with nodal failures (n = 24)∗ no. |

Patients with mucosal failures (n = 9)∗ no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 221 (85) | 15 | 7 |

| Female | 39 (15) | 9 | 2 |

| Age, y | |||

| Median | 58 | 63.5 | 61 |

| Range | 19-84 | 51-83 | 54-68 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Smoker | 179 (69) | 17 | 9 |

| Never smoked | 77 (30) | 6 | 0 |

| Method of diagnosis | |||

| Fine needle aspiration | 119 (46) | 11 | 6 |

| Excisional biopsy | 119 (46) | 8 | 3 |

| Core biopsy | 22 (8) | 5 | 0 |

| Tonsillectomy | |||

| Yes | 143 (55) | 9 | 3† |

| Lymph node staging | |||

| Nx | 1 (<1) | ||

| N1 | 25 (10) | 1 | 0 |

| N2a | 40 (15) | 1 | 0 |

| N2b | 141 (54) | 15 | 6 |

| N2c | 31 (12) | 1 | 2 |

| N3 | 22 (8) | 6 | 1 |

| Size of largest lymph node, mean (range), cm | 3.2 (0.8-12) | 4 (1.7-12) | 3.5 (1-6) |

| Number of involved neck levels | |||

| 1 | 136 (52) | 11 | 2 |

| ≥2 | 123 (47) | 13 | 7 |

| Unknown | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 |

| Solitary lymph node | |||

| Yes | 69 (27) | 3 | 0 |

| No | 190 (73) | 21 | 9 |

| Human papillomavirus∖p16 | |||

| Positive | 90 (35) | 5 | 3 |

| Negative | 23 (9) | 6 | 1 |

| Distant metastasis | |||

| Yes | 16 (6) | 6‡ | 3§ |

One patient had both nodal and mucosal failures.

The history of tonsillectomy is unknown for 1 patient.

Three patients had distant metastasis after and 3 patients concurrent with neck failure.

Two patients had neck failure after and 1 patient had distant metastasis before mucosal failure.

Twelve patients had a tonsillectomy and 6 a neck dissection (ND) preradiation therapy. None of these patients had recurrence at the operated site before radiation. Eleven patients had induction chemotherapy (IC), and 10 patients received concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT). The median delivered radiation dose to CTV1 was 66 Gy, and the median number of fractions was 30. Elective mucosal radiation was delivered to 27 patients (84%). The entire pharynx and larynx were treated in 14 patients, and treatment was limited to the oropharynx and nasopharynx in 13 patients. For patients with neck recurrences, 5 patients had post-RT ND and 4 had positive pathologically confirmed lymph nodes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment characteristics

| Characteristics | No. (%) | Patients with nodal failures (n = 24)∗ no. |

Patients with mucosal failures (n = 9)∗ no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity modulated radiation therapy technique | |||

| Split | 180 (69) | 11 | 7 |

| Whole-field intensity modulated radiation therapy | 80 (31) | 13 | 2 |

| Mucosal site targeted | |||

| Entire pharyngolaryngeal mucosa | 78 (30) | 8 | 6 |

| Naso-, oropharynx | 167 (64) | 11 | 2 |

| Mucosa not targeted | 11 (4) | 5 | 1 |

| Not specified | 4 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Induction chemotherapy ± concurrent chemotherapy† | |||

| Yes | 63 (24) | 9 | 2 |

| Type of induction chemotherapy | |||

| Taxane + platinum based | 47 | 3 | 2 |

| Platinum + cetuximab based | 15 | 6 | 0 |

| Not specified | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Concurrent chemotherapy ± induction chemotherapy† | |||

| Yes | 65 (25) | 9 | 1 |

| Type of concurrent chemotherapy | |||

| Cisplatin based | 31 | 5 | 1 |

| Carboplatin based | 18 | 4 | 0 |

| Cetuximab | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Not specified | 4 | 0 | 0 |

One patient had both nodal and mucosal failures.

Four patients had induction chemotherapy + concurrent chemoradiotherapy, 5 patients had concurrent chemoradiotherapy only, and 5 patients had induction chemotherapy only.

Failure data

Twenty-three patients had regional recurrences, 8 had mucosal recurrences, and 1 patient had both mucosal and regional recurrences. Twenty patients (of the 24 patients with neck recurrences) had gross/residual disease before RT. The remaining 4 patients had pre-RT NDs, and all 4 had extranodal extension. Overall, a total of 41 recurrent gross target volumes (GTVs) were delineated because 5 patients had mutinodal recurrences. The median and mean times to develop neck recurrences were 17.3 and 16 months, respectively. The median and mean times to develop mucosal recurrences were 108.6 and 63.6 months, respectively (Fig 1).

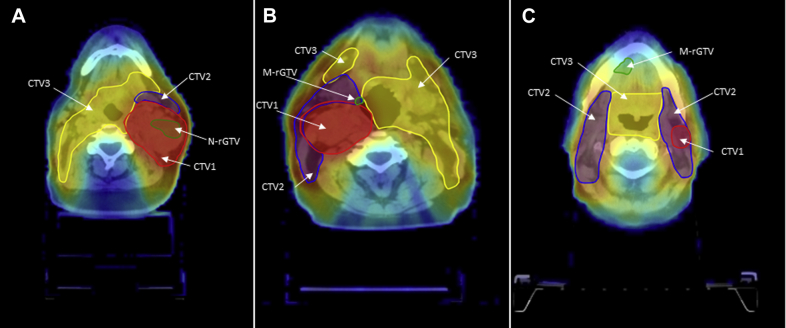

Figure 1.

Types of failures: (A) type A, central high dose (inside high-dose tumor volume and dose to 95% recurrent gross target volume [GTV] 95% dose prescribed to high-dose tumor volume); B) type C, central intermediate dose (inside intermediate dose tumor volume and dose to 95% recurrent GTV 95% dose prescribed to intermediate dose tumor volume; and C) type E, extraneous dose failure (recurrent GTV centroid originates outside all target volumes). Green, recurrent GTV; red, clinical target volume (CTV) 1; blue, CTV2; yellow, CTV3.

Of the 24 patients with neck recurrences, 21 were type A and 3 nontype A failures (2 type C and 1 type E failures, Table 3). Of the 21 patients with type A failure, 19 originally presented with stage ≥2b, 14 were smokers, and 6 had pre-RT excisional biopsies. Four patients had IC + CCRT, 5 had CCRT only, and 5 had IC only. The median prescribed dose was 68 Gy (range, 63-70 Gy) to CTV1.

Table 3.

Patients and treatment characteristics (type non-A nodal failure)

| Patient no. | Type of failure | Age (y) | Sex | Smoking status | Nodal stage | Size of largest lymph node | Solitary lymph node | Number of involved nodal groups | Induction chemotherapy | Concurrent chemoradiotherapy | Mucosal sites treated | Split/whole-field intensity modulated radiation therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C | 57 | Male | Smoker | N2b | Unknown | No | 1 | No | Yes | Partial mucosal coverage | Whole field |

| 2 | C | 64 | Male | Smoker | N2b | 3.2 cm | No | >1 | No | Yes | Whole mucosal coverage | Split |

| 3 | E | 66 | Male | Smoker | N3 | 6 cm | No | >1 | No | Yes | No coverage | Split |

Mucosal failures were distributed as follows: 7 type C and 2 type E. For the 2 patients who had type E failures, 1 patient received whole pharyngeal axis irradiation and the other patient did not receive any elective mucosal irradiation. Five mucosal recurrences were found within the oropharynx, 3 within the larynx and 1 within the oral cavity.

Of the 7 patients with type C mucosal failure, 3 had a tonsillectomy before RT. Five of those 7 patients were treated with whole pharyngeal RT and 2 with partial pharyngeal RT to a median dose of 54 Gy (range, 50-54 Gy). None of the patients received CCRT, and 1 patient received IC. The oropharynx was the failure site in 5 patients, and the supraglottis was the site of recurrence in 2 patients. Only 1 patient experienced both mucosal and nodal relapse outside the RT field (type E mucosal and nodal failures) after CCRT along with split-field IMRT with an RT dose of 60 Gy for the GTV and 54 Gy as an elective dose to adjacent lymph node groups in the unilateral neck after selective ND. Seven patients with neck recurrences (29%) had NDs as part of the treatment for their recurrent disease. Eight patients with mucosal disease (89%) had surgical salvage.

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to apply previously validated methodology15 for POF analysis on a cohort of patients with HN-SCCUP after IMRT, as part of curative-intent multimodal treatment. Our institutional experience and others have shown excellent disease-related outcomes, and the advent of IMRT has allowed for significant improvements in the therapeutic ratio, with reported failure rates of 5% to 10%.4,10,12,17 Nevertheless, a nonnegligible proportion of patients is expected to develop recurrent diseases.

Our data showed that the majority of nodal recurrences (either actual recurrence or persistent disease) were located within the irradiated tissues, with the vast majority in the high-dose region (type A). Although the recurrence rate is low overall because these were almost always type A recurrences, we hypothesize that a small subset of nodes have radioresistant cells. If this assumption is true, large-scale quantitative POF typology should be correlated with previously investigated biologic signatures to identify treatment resistant areas.

The incorporation of dosimetric gradients in POF analyses along with novel biomarkers may provide further elucidation in the biologic behavior of the disease and help to define personalized treatment strategies for patients with HN-SCCUP. Specifically, the human papilloma virus (HPV) status has been validated as a prognosticator, and several authors have suggested its role in treatment selection for de-intensification strategies.18,19 Although positron emission tomography/CT has a potential improvement for staging of head and neck cancer, metabolic-directed tumor segmentation is still investigational in nature.20,21 These novel approaches would ideally integrate the standard prognostic factors for HN-SCCUP, namely age, nodal stage (unilateral versus bilateral), nodal size, and extracapsular extension.22, 23, 24

Therefore, in the era of personalized medicine, POF typology could be used as a tool for patient stratification to shepherd the choice between unimodal versus multimodal therapies. Although the role of RT is well established, the benefit of elective ND for HN-SCCUP remains unclear.7,13 Likewise, there is still a debate about the role of chemotherapy, both in the adjuvant and concurrent setting.25 We individualize the usage of concurrent chemotherapy, and still consider preoperative ND for patients with a low nodal burden. If there are no adverse pathologic criteria, ND alone could be the treatment of choice after multidisciplinary discussion. High nodal burden (N3, multiple bulky diseases or radiologic evidence of extensive extracapsular extension) favors adding systemic agents before or during RT. CCRT is only used after ND in patients with extensive extracapsular extension. Additionally, dose intensification (GTV boosts) might be considered to overcome resistant arears.

We strongly believe that the application of our standardized methodology for the classification of POFs may help in the individualization and optimization of RT strategies in the HN-SCCUP setting. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to incorporate a discrete spatial component (centroid-based approach) into the dosimetric analysis of failures after IMRT for HN-SCCUP. Such an approach overcomes the classic definition of infield versus marginal versus out-of-field recurrence, which is biased by volume and time dependency. Furthermore, the investigation of dosimetric components allows for radiation oncologists to discriminate whether the failure was driven by intrinsic biologic radioresistance rather than amendable procedural errors (eg, patient setup).

As a retrospective series, standard caveats apply. Additionally, the rarity of the disease and the excellent rates of locoregional control are likely to prevent the collection of a larger number of cases by a single institution, which should be taken into account. This methodology could provide more accurate and reproducible information regarding the biologic characteristics of recurrent disease. Larger-scale applications of this approach are warranted to fully understand and predict the treatment outcomes after IMRT for HN-SCCUP. To this aim, preliminary efforts are underway for the creation of future cooperative networks interested in quantitative imaging analysis in the setting of radiation oncology.

Conclusions

This study was designed to describe the POF after IMRT for HN-SCCUP, using validated typology-indicative taxonomy. The majority of nodal recurrences occurred within the high-dose area in patients with HN-SCCUP. Thus, dose escalation of high-risk and biologically less favorable volumes, metabolic-directed tumor segmentation, and use of radiosensitizers in patients with HN-SCCUP need to be further studied.

Footnotes

Sources of support: Drs. Hutcheson, Mohamed, and Fuller received funding support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (1R01DE025248-01/R56DE025248-01). Drs. Hutcheson and Fuller are supported by the NIH/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Small Grants Program for Cancer Research (R03 CA188162). Dr. Fuller is an MD Anderson Cancer Center Andrew Sabin Family Fellow, and received project support in this role from the Andrew Sabin Family Foundation. Dr. Mohamed receive funding and/or salary support from the NIH, including Big Data to Knowledge Program of the NCI Early Stage Development of Technologies in Biomedical Computing, Informatics, and Big Data Science Award (1R01CA214825-01); NCI Early Phase Clinical Trials in Imaging and Image Guided Interventions Program (1R01CA218148-01; an NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant Pilot Research Program Award from the UT MD Anderson CCSG Radiation Oncology and Cancer Imaging Program [P30CA016672]) and an NIH/NCI Head and Neck Specialized Programs of Research Excellence Developmental Research Program Award (P50 CA097007-10). The family of Paul W. Beach was providing direct salary support for Dr. Kamal. Dr. Ng received grant funding from the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists and Radiological Society of North America.

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

Disclosures: Dr. Fuller has received direct industry grant funding and speaker travel from Elekta AB for unrelated technical projects. Dr. Rosenthal reports grants, personal fees, and reimbursement for accommodations and travel fees from Merck outside the submitted work. Dr. Fuller reports grants from GE Healthcare, Elekta AB, National Science Foundation, and NIH, and personal fees from The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Elekta AB, Oregon Health and Science University, the Greater Baltimore Medical Center, the University of Illinois Chicago, and The Translational Research Institute Australia, and royalties from Demos Medical Publishing outside of the submitted work. Dr. Sturgis reports nonfinancial support from Roche Diagnostics, and a research award providing reagents free of charge for human papillomavirus testing of oral rinse and mucosal swab studies of a clinical trial exploring screening for human papillomavirus-related cancers. The remaining authors made no disclosures. These entities played no role in designing the study; collecting, analyzing, or interpreting its data; writing the manuscript; or making the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

- 1.Strojan P., Ferlito A., Langendijk J.A. Contemporary management of lymph node metastases from an unknown primary to the neck: II. A review of therapeutic options. Head Neck. 2013;35:286–293. doi: 10.1002/hed.21899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snow G.B., Annyas A.A., van Slooten E.A., Bartelink H., Hart A.A. Prognostic factors of neck node metastasis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1982;7:185–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1982.tb01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grau C., Johansen L.V., Jakobsen J., Geertsen P., Andersen E., Jensen B.B. Cervical lymph node metastases from unknown primary tumours. Results from a national survey by the Danish Society for Head and Neck Oncology. Radiother Oncol. 2000;55:121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shoushtari A., Saylor D., Kerr K.L. Outcomes of patients with head-and-neck cancer of unknown primary origin treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:e83–e91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fotopoulos G., Pavlidis N. The role of human papilloma virus and p16 in occult primary of the head and neck: A comprehensive review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rusthoven K.E., Koshy M., Paulino A.C. The role of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in cervical lymph node metastases from an unknown primary tumor. Cancer. 2004;101:2641–2649. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aslani M., Sultanem K., Voung T., Hier M., Niazi T., Shenouda G. Metastatic carcinoma to the cervical nodes from an unknown head and neck primary site: Is there a need for neck dissection? Head Neck. 2007;29:585–590. doi: 10.1002/hed.20581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beldì D., Jereczek-Fossa B.A., D'Onofrio A. Role of radiotherapy in the treatment of cervical lymph node metastases from an unknown primary site: Retrospective analysis of 113 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1051–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank S.J., Rosenthal D.I., Petsuksiri J. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy for cervical node squamous cell carcinoma metastases from unknown head-and-neck primary site: M. D. Anderson cancer center outcomes and patterns of failure. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:1005–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamal M., Mohamed A.S.R., Fuller C.D. Outcomes of patients diagnosed with carcinoma metastatic to the neck from an unknown primary source and treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Cancer. 2018;124:1415–1427. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu H., Yao M., Tan H. Unknown primary head and neck cancer treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy: To what extent the volume should be irradiated. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen A.M., Li B.Q., Farwell D.G., Marsano J., Vijayakumar S., Purdy J.A. Improved dosimetric and clinical outcomes with intensity-modulated radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer of unknown primary origin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:756–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace A., Richards G.M., Harari P.M. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma from an unknown primary site. Am J Otolaryngol. 2011;32:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards T.M., Bhide S.A., Miah A.B. Total mucosal irradiation with intensity-modulated radiotherapy in patients with head and neck carcinoma of unknown primary: A pooled analysis of two prospective studies. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2016;28:e77–e84. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohamed A.S.R., Rosenthal D.I., Awan M.J. Methodology for analysis and reporting patterns of failure in the Era of IMRT: head and neck cancer applications. Radiat Oncol. 2016;11:95. doi: 10.1186/s13014-016-0678-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohamed A.S., Ruangskul M.N., Awan M.J. Quality assurance assessment of diagnostic and radiation therapy-simulation CT image registration for head and neck radiation therapy: Anatomic region of interest-based comparison of rigid and deformable algorithms. Radiology. 2015;274:752–763. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14132871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank S.J., Rosenthal D.I., Petsuksiri J. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy for cervical node squamous cell carcinoma metastases from unknown head-and-neck primary site: M. D. Anderson Cancer Center outcomes and patterns of failure. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:1005–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sivars L., Landin D., Grun N. Validation of human papillomavirus as a favourable prognostic marker and analysis of CD8+ tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and other biomarkers in cancer of unknown primary in the head and neck region. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:665–673. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroeder L., Boscolo-Rizzo P., Dal Cin E. Human papillomavirus as prognostic marker with rising prevalence in neck squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary: A retrospective multicentre study. Eur J Cancer. 2017;74:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank S.J., Chao K.S.C., Schwartz D.L., Weber R.S., Apisarnthanarax S., Macapinlac H.A. Technology insight: PET and PET/CT in head and neck tumor staging and radiation therapy planning. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:526–533. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deantonio L., Beldì D., Gambaro G. FDG-PET/CT imaging for staging and radiotherapy treatment planning of head and neck carcinoma. Radiat Oncol. 2008;3:29. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-3-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Axelsson L., Nyman J., Haugen-Cange H. Prognostic factors for head and neck cancer of unknown primary including the impact of human papilloma virus infection. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;46:45. doi: 10.1186/s40463-017-0223-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park G.C., Jung J.H., Roh J.L. Prognostic value of metastatic nodal volume and lymph node ratio in patients with cervical lymph node metastases from an unknown primary tumor. Oncology. 2014;86:170–176. doi: 10.1159/000358177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tribius S., Hoffmann A.S., Bastrop S. HPV status in patients with head and neck of carcinoma of unknown primary site: HPV, tobacco smoking, and outcome. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:1178–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackenzie K., Watson M., Jankowska P., Bhide S., Simo R. Investigation and management of the unknown primary with metastatic neck disease: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130:S170–S175. doi: 10.1017/S0022215116000591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]