Abstract

Background

This longitudinal study aimed to examine the changes in psychological distress of the general public from the early to community-transmission phases of the COVID-19 pandemic and to investigate the factors related to these changes.

Methods

An internet-based survey of 2,400 Japanese people was conducted in two phases: early phase (baseline survey: February 25–27, 2020) and community-transmission phase (follow-up survey: April 1–6, 2020). The presence of severe psychological distress (SPD) was measured using the Kessler’s Six-scale Psychological Distress Scale. The difference of SPD percentages between the two phases was examined. Mixed-effects ordinal logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the factors associated with the change of SPD status between the two phases.

Results

Surveys for both phases had 2,078 valid respondents (49.3% men; average age, 50.3 years). In the two surveys, individuals with SPD were 9.3% and 11.3%, respectively, demonstrating a significant increase between the two phases (P = 0.005). Significantly higher likelihood to develop SPD were observed among those in lower (ie, 18,600–37,200 United States dollars [USD], odds ratio [OR] 1.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.10–3.46) and the lowest income category (ie, <18,600 USD, OR 2.12; 95% CI, 1.16–3.86). Furthermore, those with respiratory diseases were more likely to develop SPD (OR 2.56; 95% CI, 1.51–4.34).

Conclusions

From the early to community-transmission phases of COVID-19, psychological distress increased among the Japanese. Recommendations include implementing mental health measures together with protective measures against COVID-19 infection, prioritizing low-income people and those with underlying diseases.

Key words: K6, novel coronavirus, mental health, general population

INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus infection that started in Wuhan, China, has spread throughout the world, and the World Health Organization (WHO) has officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic. As of June 15, 2020, the total number of infected individuals has exceeded 7 million, while the number of deaths has reached 400,000.1 The rapid spread of COVID-19 has created fear and anxiety about contracting the virus.2,3 It has also caused a lack of access to medical care and restrictions in daily life, in addition to having a major economic impact due to the suspension of businesses and unemployment.4–6 It has been noted that these circumstances might not only affect physical health but also lead to the deterioration of mental health, which in turn, would make the implementation of preventive actions, such as refraining from going out and social distancing, more challenging. We believe that this will result in a vicious cycle that will ultimately lead to the spread of the infection. In addition to maintaining the mental wellbeing of individuals, mental health measures are important for early suppression of transmission of the infection.3,7

To consider the need for mental health measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is necessary to first formulate an epidemiological description of the severity of related mental health problems. According to the results of a recent cross-sectional survey in China, 16–28% of citizens reported anxiety and depression.8 However, since other cross-sectional studies were unable to compare these data with pre-COVID-19 levels, the magnitude of its impact is unknown. To clarify the pandemic’s impact on the general public’s mental health, a longitudinal study that would allow tracking of subjects from the early phase before the pandemic is necessary.9 A study by Wang et al included a survey at two time points to determine the impact of mental health; however, their study recruited different individuals in each of the two surveys, so they could not assess inter-personal changes in psychological distress.10 To the best of our knowledge, no longitudinal studies have yet investigated the same individuals at two time points.

Furthermore, when devising mental health actions, it is necessary to identify the specific characteristics of individuals who are at a higher risk. It has been pointed out that older people with underlying diseases, those with mental health problems before the pandemic, children, and medical workers might be at high risk for the deterioration of mental health.5 In China, gender, age, and educational background were cited as relevant factors.8,11,12 Since only cross-sectional studies have been conducted, it is difficult to determine whether individuals’ mental health deteriorated after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, or whether their mental health was poor prior to the pandemic.

With this in mind, the purpose of this study was to: i) investigate the degree of change in mental health at the population level, and ii) identify the high-risk groups prone to mental health deterioration during the phases of the pandemic through a longitudinal study.

METHODS

Study sample and data collection

This longitudinal study was based on an internet-based survey. The details of this study are only briefly addressed here, since the subject extraction method was described in more detail in our previous study.13 In the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan, a baseline survey was conducted during February 25–27, 2020. The participants were recruited from MyVoice Communication, Inc., a Japanese Internet research service company with approximately 1.12 million registered participants as of January 2020. Its aim was to collect data from 2,400 men and women aged 20–79 years (sampled by sex and 10-year age groups; n = 200 in each of the 12 groups), who were living near the Tokyo metropolitan area across seven prefectures (ie, Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, Chiba, Ibaraki, Tochigi, and Gunma). As of January 2019, the Tokyo metropolitan area, with a total area of 32,433.4 km2, is home to approximately 35% of Japan’s total population of 43,512,238. The company invited registrants to participate in the survey by email on February 25, 2020 (n = 8,156). The questionnaires were placed in a secured area of a website, and potential respondents received a specific URL in their invitation email. Once 200 participants in each group had voluntarily responded to the questionnaire, the company stopped accepting responses from that group, and after collecting 200 responses from all groups, the survey was concluded on February 27.

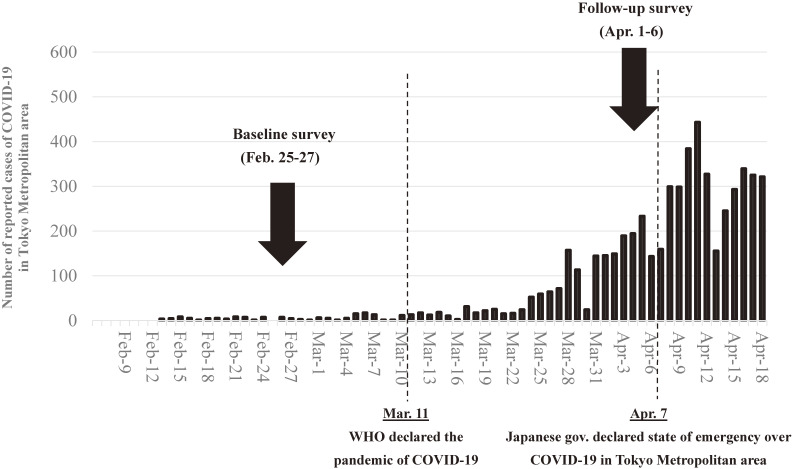

On April 1, Japan reported 2,178 COVID-19 cases, representing a rapid increase in the number of patients, mainly in Tokyo1 On the same day, 2,400 respondents from the baseline survey were sent an invitation email to participate in a follow-up survey. The questionnaires were placed in a secured section of a website, and the potential respondents received a specific URL in their invitation email. All 2,400 baseline survey respondents voluntarily responded to the questionnaire, and the cutoff date for completion of the survey was April 6. On April 7, the Japanese government declared a state of emergency.14 This study used the data of participants who answered both the baseline and follow-up surveys (n = 2,078) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Date of surveys with COVID-19 epidemic curve in Tokyo Metropolitan area.

As an incentive, participants of both the baseline and follow-up surveys were allotted reward points valued at 50 Japanese yen (JPY) (approximately 0.5 United States dollars [USD] based on the prevailing exchange rate in April 2020).

Measurement

Assessment of severe psychological distress

In both the baseline and follow-up surveys, the Kessler’s Six-scale Psychological Distress Scale (K6) was used to measure severe psychological distress (SPD).15 The K6 is broadly used in epidemiological studies to assess depression or suicide prevention,16–19 since it measures psychological distress in the general population using six simple items. Each item measures the extent of general nonspecific psychological distress using a 5-point response: 0 “none of the time,” 1 “a little of the time,” 2 “some of the time,” 3 “most of the time,” and 4 “all of the time”; thus, the total scores ranged from 0 to 24. The K6 was translated into Japanese, and a previous study of 164 Japanese adults showed its internal consistency in relation to reliability (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.849) and validity (100% sensitivity and 69.3% specificity for screening mood and anxiety disorder).20 This study used an established protocol to define a score of 13 or above to indicate SPD.21

Assessment of sociodemographic factors

In the baseline survey, participants reported their sex, age, residential area (Northern Kanto area [Ibaraki, Tochigi, and Gumma Prefectures], Saitama Prefecture, Chiba Prefecture, Kanagawa Prefecture, Tokyo Metropolis), working status (working, not working); marital status (single, divorced, separated, married), living arrangements (alone, with others but without children, with children aged 18 years or older, with others and children under 18 years), annual personal income (less than 2 million JPY [approximately 18,600 USD], 2–<4 million JPY [18,600–<37,200 USD], 4–6 million JPY [37,200–<55,800 USD], 6 million JPY or more [≥55,800 USD]); smoking (smokers, ex-smokers, non-smokers), alcohol consumption (never, seldom [1–4 times/week], often [5–7 times/week]), daily walking time (less than 30 mins, 30–59 mins, ≥60 mins), regular annual vaccination (yes, no), and past medical history (hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, respiratory disease, kidney disease, cancer). In addition, the research company provided categorized data on educational attainment (junior or high school graduate, junior college graduate, university graduate or above, others).

Statistical analysis

In the baseline and follow-up surveys, the K6 score was calculated and the t-test was used to determine the difference between the two time points among each individual factors. In addition, McNemar’s test was used to examine the percentage of people who scored 13 or more in the K6. To assess the associated factors for changing SPD status between baseline and follow-up surveys, mixed-effects ordinal logistic regression analyses were performed by nesting each participant.22 In this analysis, fixed effects for all individual factors were estimated after adjusting total K6 score at baseline. All variables were placed in the model at the same time. All analyses were performed using Stata software version 15 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan (No: T2019-0234). Informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants and their SPD percentages during the baseline and follow-up surveys. Of the 2,078 participants, 1,029 (49.3%) were men and the average age was 50.3 (standard deviation [SD], 15.3) years. Approximately 37.2% were workers, of whom 19.1% were living alone. The majority were university graduates or had higher educational attainment. The average K6 scores in the baseline and follow-up surveys were 4.79 (SD, 5.3 points) and 5.60 (SD, 5.4 points), respectively, indicating a significant increase (P < 0.001). The percentage of SPD (K6 ≥13) was 9.34% and 11.31% in the baseline and follow-up surveys, respectively, indicating a 2% increase (P = 0.005).

Table 1. Differences in psychological distress by individual factor.

| n | % | K6 score (range: 0–24) |

Proportion of severe psychological distress (K6 score ≥13) |

|||||||||

| Baseline survey (February 25–27, 2020) |

Follow-up survey (April 1–7, 2020) |

Pa | Baseline survey (February 25–27, 2020) |

Follow-up survey (April 1–7, 2020) |

Pb | |||||||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | n | (%) | n | (%) | |||||

| Overall | 2,078 | 4.79 | 5.30 | 5.60 | 5.44 | <0.001 | 194 | 9.34% | 235 | 11.31% | 0.005 | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1,024 | 49.3% | 4.68 | 5.33 | 5.45 | 5.60 | <0.001 | 97 | 9.47% | 113 | 11.04% | 0.120 |

| Female | 1,054 | 50.7% | 4.90 | 5.28 | 5.74 | 5.27 | <0.001 | 97 | 9.20% | 122 | 11.57% | 0.016 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 20–29 years | 288 | 13.9% | 6.62 | 6.28 | 7.24 | 6.46 | 0.049 | 49 | 17.01% | 56 | 19.44% | 0.297 |

| 30–39 years | 358 | 17.2% | 6.42 | 6.41 | 7.16 | 6.16 | 0.011 | 61 | 17.04% | 60 | 16.76% | 0.895 |

| 40–49 years | 366 | 17.6% | 5.36 | 5.24 | 6.19 | 5.49 | <0.001 | 37 | 10.11% | 51 | 13.93% | 0.048 |

| 50–59 years | 356 | 17.1% | 4.25 | 4.77 | 5.08 | 4.89 | <0.001 | 25 | 7.02% | 30 | 8.43% | 0.336 |

| 60–69 years | 363 | 17.5% | 3.43 | 3.98 | 4.22 | 4.38 | <0.001 | 13 | 3.58% | 23 | 6.34% | 0.499 |

| 70–79 years | 347 | 16.7% | 2.97 | 3.66 | 3.95 | 4.15 | <0.001 | 9 | 2.59% | 15 | 4.32% | 0.058 |

| Residential area | ||||||||||||

| Northern Kanto (Ibaraki, Tochigi, Gumma Prefectures) | 189 | 9.1% | 5.01 | 5.43 | 5.98 | 5.57 | <0.001 | 20 | 10.58% | 23 | 12.17% | 0.439 |

| Saitama Prefecture | 336 | 16.2% | 4.90 | 5.52 | 5.71 | 5.88 | 0.001 | 37 | 11.01% | 43 | 12.80% | 0.317 |

| Chiba Prefecture | 300 | 14.4% | 4.44 | 5.05 | 5.04 | 5.04 | 0.019 | 25 | 8.33% | 26 | 8.67% | 0.862 |

| Tokyo Metropolis | 801 | 38.5% | 4.89 | 5.30 | 5.70 | 5.40 | <0.001 | 68 | 8.49% | 95 | 11.86% | 0.003 |

| Kanagawa Prefecture | 452 | 21.8% | 4.69 | 5.27 | 5.53 | 5.36 | <0.001 | 44 | 9.73% | 48 | 10.62% | 0.555 |

| Working status | ||||||||||||

| No | 773 | 37.2% | 4.48 | 5.14 | 5.39 | 5.35 | <0.001 | 64 | 8.28% | 83 | 10.74% | 0.012 |

| Yes | 1,305 | 62.8% | 4.98 | 5.39 | 5.72 | 5.49 | <0.001 | 130 | 9.96% | 152 | 11.65% | 0.080 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Single, divorced, separated | 869 | 41.8% | 5.87 | 5.91 | 6.48 | 6.14 | <0.001 | 125 | 14.38% | 141 | 16.23% | 0.127 |

| Married | 1,209 | 58.2% | 4.02 | 4.67 | 4.96 | 4.78 | <0.001 | 69 | 5.71% | 94 | 7.78% | 0.015 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||||||||

| Living alone | 396 | 19.1% | 5.14 | 5.42 | 5.81 | 5.68 | 0.005 | 45 | 11.36% | 52 | 13.13% | 0.336 |

| Living with others but without children | 991 | 47.7% | 4.99 | 5.52 | 5.80 | 5.72 | <0.001 | 100 | 10.09% | 128 | 12.92% | <0.001 |

| Living with children aged ≥18 years | 349 | 16.8% | 3.39 | 3.86 | 4.36 | 4.29 | <0.001 | 12 | 3.44% | 19 | 5.44% | 0.127 |

| Living with children aged <18 years | 342 | 16.5% | 5.25 | 5.56 | 6.01 | 5.19 | 0.005 | 37 | 10.82% | 36 | 10.53% | 0.879 |

| Education (years) | ||||||||||||

| Junior or high school graduate (≤12 years) | 490 | 23.6% | 5.16 | 5.56 | 6.12 | 5.88 | <0.001 | 56 | 11.43% | 68 | 13.88% | 0.101 |

| Junior college graduate (13–15 years) | 441 | 21.2% | 4.67 | 4.75 | 5.56 | 5.09 | <0.001 | 33 | 7.48% | 43 | 9.75% | 0.114 |

| University graduate or above (≥16 years) | 1,122 | 54.0% | 4.64 | 5.34 | 5.38 | 5.36 | <0.001 | 101 | 9.00% | 122 | 10.87% | 0.050 |

| Other | 25 | 1.2% | 6.56 | 6.92 | 5.40 | 5.73 | 0.383 | 4 | 16.00% | 2 | 8.00% | 0.317 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||||

| Smoker | 311 | 15.0% | 4.81 | 5.30 | 5.70 | 5.50 | <0.001 | 29 | 9.32% | 37 | 11.90% | 0.206 |

| Ex-smoker | 303 | 14.6% | 4.21 | 4.97 | 4.77 | 5.05 | 0.039 | 23 | 7.59% | 29 | 9.57% | 0.273 |

| Non-smoker | 1,464 | 70.5% | 4.91 | 5.36 | 5.74 | 5.49 | <0.001 | 142 | 9.70% | 169 | 11.54% | 0.025 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||

| None | 882 | 42.4% | 5.10 | 5.70 | 5.78 | 5.62 | <0.001 | 103 | 11.68% | 105 | 11.90% | 0.838 |

| Seldom (1–4 days/week) | 741 | 35.7% | 4.74 | 5.05 | 5.71 | 5.31 | <0.001 | 62 | 8.37% | 84 | 11.34% | 0.009 |

| Often (5–7 days/week) | 455 | 21.9% | 4.27 | 4.85 | 5.06 | 5.25 | <0.001 | 29 | 6.37% | 46 | 10.11% | 0.015 |

| Walking time, mins/day | ||||||||||||

| <30 | 1,047 | 50.4% | 5.10 | 5.51 | 5.89 | 5.63 | <0.001 | 116 | 11.08% | 138 | 13.18% | 0.039 |

| 30–59 | 687 | 33.1% | 4.39 | 4.88 | 5.33 | 5.18 | <0.001 | 50 | 7.28% | 66 | 9.61% | 0.052 |

| ≥60 | 344 | 16.6% | 4.66 | 5.41 | 5.23 | 5.30 | 0.034 | 28 | 8.14% | 31 | 9.01% | 0.602 |

| Regular vaccinations | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1,159 | 55.8% | 4.85 | 5.50 | 5.48 | 5.54 | <0.001 | 119 | 10.27% | 136 | 11.73% | 0.119 |

| No | 919 | 44.2% | 4.72 | 5.04 | 5.74 | 5.31 | <0.001 | 75 | 8.16% | 99 | 10.77% | 0.014 |

| Annual personal income, United States dollars | ||||||||||||

| <18,600 | 936 | 45.0% | 6.03 | 6.03 | 6.22 | 5.72 | <0.001 | 106 | 11.32% | 129 | 13.78% | 0.028 |

| 18,600–<37,200 | 531 | 25.6% | 4.61 | 5.06 | 5.25 | 5.41 | 0.004 | 54 | 10.17% | 60 | 11.30% | 0.453 |

| 37,200–<55,800 | 312 | 15.0% | 4.24 | 4.86 | 5.44 | 5.01 | <0.001 | 22 | 7.05% | 26 | 8.33% | 0.479 |

| ≥55,800 | 299 | 14.4% | 4.15 | 4.90 | 4.43 | 4.72 | 0.006 | 12 | 4.01% | 20 | 6.69% | 0.074 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||||

| Hypertension | 395 | 19.0% | 4.24 | 4.79 | 4.94 | 4.86 | <0.001 | 26 | 6.58% | 33 | 8.35% | 0.178 |

| Diabetes | 123 | 5.9% | 4.55 | 4.88 | 4.53 | 5.23 | 0.936 | 10 | 8.13% | 12 | 9.76% | 0.480 |

| Heart disease | 62 | 3.0% | 4.89 | 5.02 | 6.42 | 5.76 | 0.003 | 5 | 8.06% | 10 | 16.13% | 0.059 |

| Stroke | 20 | 1.0% | 6.00 | 7.18 | 6.25 | 7.27 | 0.536 | 4 | 20.00% | 4 | 20.00% | 1.000 |

| Respiratory disease | 89 | 4.3% | 6.36 | 5.68 | 7.67 | 6.30 | 0.006 | 16 | 17.98% | 22 | 24.72% | 0.157 |

| Kidney disease | 10 | 0.5% | 7.30 | 7.18 | 8.20 | 7.13 | 0.430 | 1 | 10.00% | 2 | 20.00% | 0.317 |

| Cancer | 43 | 2.1% | 5.33 | 5.35 | 5.86 | 5.13 | 0.477 | 2 | 4.65% | 3 | 6.98% | 0.564 |

K6, Kessler’s Six-scale Psychological Distress Scale; SD, standard deviation.

aP-value was calculated using paired t-test.

bP-value was calculated using McNemar’s test.

Bold values denote statistical significance at P < 0.05.

Table 2 shows the results of a mixed-effects ordinal logistic regression analysis. Compared to those with higher income (ie, ≥55,800 USD of annual personal income), significantly high likelihood to develop SPD were observed among those in lower (ie, 18,600–37,200 USD, odds ratio [OR] 1.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.10–3.46) and the lowest income category (ie, <18,600 USD, OR 2.12; 95% CI, 1.16–3.86). Furthermore, those with respiratory diseases were more likely to develop SPD (OR 2.56; 95% CI, 1.51–4.34).

Table 2. Individual factors associated with development of severe psychological distress: mixed-effect ordinal logistic regression results.

| ORa | 95% CI | P | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 0.87 | (0.63–1.20) | 0.389 |

| Age | |||

| 20–29 years | 1.26 | (0.73–2.16) | 0.403 |

| 30–39 years | 1.22 | (0.73–2.05) | 0.449 |

| 40–49 years | 1.39 | (0.84–2.32) | 0.202 |

| 50–59 years | 1.00 | ||

| 60–69 years | 1.04 | (0.59–1.83) | 0.899 |

| 70–79 years | 0.79 | (0.40–1.56) | 0.497 |

| Residential area | |||

| Northern Kanto (Ibaraki, Tochigi, or Gumma Prefectures) | 1.01 | (0.62–1.65) | 0.963 |

| Saitama Prefecture | 1.22 | (0.82–1.82) | 0.321 |

| Chiba Prefecture | 1.02 | (0.65–1.59) | 0.942 |

| Tokyo Metropolitan | 1.00 | ||

| Kanagawa Prefecture | 1.13 | (0.79–1.63) | 0.507 |

| Working status | |||

| No | 1.11 | (0.77–1.59) | 0.590 |

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Never married, divorced, or separated | 1.06 | (0.71–1.60) | 0.767 |

| Married | 1.00 | ||

| Living arrangement | |||

| Living alone | 1.08 | (0.74–1.60) | 0.682 |

| Living with others but without children | 1.00 | ||

| Living with children aged ≥18 years | 0.94 | (0.55–1.59) | 0.811 |

| Living with children aged <18 years | 0.85 | (0.52–1.36) | 0.491 |

| Education (years) | |||

| Junior or high school (≤12 years) | 0.98 | (0.69–1.39) | 0.914 |

| College (13–15 years) | 0.99 | (0.68–1.45) | 0.967 |

| University or higher (≥16 years) | 1.00 | ||

| Others | 0.29 | (0.07–1.26) | 0.098 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current | 1.00 | ||

| Quit | 1.17 | (0.78–1.74) | 0.446 |

| Never | 1.21 | (0.78–1.87) | 0.388 |

| Drinking alcohol | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Seldom (1–4 days/week) | 1.11 | (0.81–1.52) | 0.517 |

| Often (5–7 days/week) | 1.16 | (0.78–1.74) | 0.458 |

| Walking time, min/day | |||

| <30 | 1.47 | (0.96–2.24) | 0.075 |

| 30–59 | 1.27 | (0.80–2.00) | 0.306 |

| ≥60 | 1.00 | ||

| Vaccinated regularly | |||

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| No | 1.09 | (0.68–1.73) | 0.724 |

| Annual personal income, United States dollars | |||

| <18,600 | 2.12 | (1.16–3.86) | 0.014 |

| 18,600–<37,200 | 1.95 | (1.10–3.46) | 0.022 |

| 37,200–<55,800 | 1.19 | (0.65–2.17) | 0.572 |

| ≥55,800 | 1.00 | ||

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 0.82 | (0.53–1.27) | 0.374 |

| Diabetes | 1.27 | (0.67–2.43) | 0.460 |

| Heart disease | 1.71 | (0.74–3.97) | 0.210 |

| Stroke | 1.30 | (0.26–6.50) | 0.746 |

| Respiratory disease | 2.56 | (1.51–4.34) | <0.001 |

| Kidney disease | 0.64 | (0.08–5.03) | 0.668 |

| Cancer | 0.34 | (0.09–1.31) | 0.117 |

| Baseline K6 score | 1.43 | (1.39–1.48) | <0.001 |

K6, Kessler’s Six-scale Psychological Distress Scale; OR, odds ratio.

Bold values denote statistical significance at the P < 0.05 level.

aOdds ratios were calculated with adjustment for all other variables (ie, gender, age, residential area, working status, marital status, living arrangement, education, smoking status, drinking alcohol, walking time, regular vaccination, annual personal income, comorbidities and K6 score at baseline).

DISCUSSION

Summary of findings

We set out to determine the degree of change in the psychological distress of the general population in the Kanto region between the early and transmission phases of COVID-19, and the characteristics of those who displayed a significant change. The results demonstrated that the mental health of the general population had significantly deteriorated from the early phase to transmission phase. The degree of deterioration was more remarkable among those with respiratory diseases and those with low incomes.

Overall impact

This study was able to confirm the degree of deterioration and determine causal factors. In an interview survey conducted in the United Kingdom on the general population and psychiatric patients, the causes for the deterioration of mental health were identified as: i) anxiety caused by uncertainty, ii) increased sense of isolation due to social distancing policy, iii) diminished medical access, and iv) family relations (eg, family concerns, domestic violence).23 In fact, there is evidence that suicide deaths increased due to the 1918–19 influenza pandemic.24 Therefore, it can be suggested that mental health measures should be implemented together with other protective measures against COVID-19 infection.

High-risk groups

In this study, a high degree of deterioration was observed among low-income individuals, which we believe may have been affected by a decrease in income between the two phases. On March 28, 2020, the Japanese government introduced the “Basic Policy for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control”.25 This policy strongly urged the public to refrain from going outside unless it was absolutely necessary, to reduce social interaction, and to work remotely as much as possible. This also included the suspension of services involving the congregation of people; therefore, various businesses, such as fitness facilities, restaurants, and concert venues, closed temporarily. Speculatively, a majority of those who work at such facilities are part-time or temporary workers, most often individuals with low incomes. It is possible that the suspension of these businesses may have greatly reduced their income or even led to their dismissal, thus posing a threat to their daily lives.

In the past, the number of suicides increased in central Hong Kong due to the economic impact during the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).26 Similarly, there was a concern that suicide cases might increase during the COVID-19 pandemic for various reasons, including economic loss.6 It is still uncertain what the future holds for Japan. Many countries are providing financial support to cover the loss of income due to the pandemic. As this study has shown a deterioration in mental health earlier than others, it may be important to provide such financial support at an early stage for low socio-economic status groups.

Impact on people with underlying diseases

It has been pointed out that the mental health of those with underlying diseases might further deteriorate.5 This study revealed that mental health worsened in people with respiratory diseases, among other underlying diseases. This may have been caused by the fear of the possibility of becoming severely ill as a result of infection. Another reason may be that during the shift from the early phase to the transmission phase, medical facilities had no choice but to concentrate on coronavirus treatment, causing limited access for these patients. Providing support, such as by expanding online medical consultations, for those with respiratory diseases may be necessary to enable patients to continue treatment without anxiety.

Strengths and limitations

There are some limitations to our study that should be considered. First, selection bias in the web-based internet survey could have been introduced. According to a 2019 white paper, regular internet-users were younger age and had higher income compared to non-users.27 Older adults in the present study may have a higher income than average. In addition, loss to follow-up occurred more frequently among youth, never smokers, those who live with children aged >18 years, and those who do not take vaccines regularly (data not shown), which may cause selection bias. Second, the results may not be directly applicable to the Japanese population due to limited representativeness. Age- and gender-stratified sampling causes different distributions of individual characteristics, compared to Japanese population. In addition, the study participants were recruited from the Tokyo metropolitan area only. Furthermore, the level of psychological distress among younger age-groups was higher than the national average.28 Taken together, future research would be needed to investigate the change of psychological distress, especially among youth in non-Tokyo areas. Third, no data on current or past history of medication for mental health were obtained for this study. If a certain number of participants started medication during the period of the two surveys, the results may be biased. Finally, the sample size is not sufficiently large; hence, this study may overlook the true association due to lower statistical power. For example, those with heart disease or kidney disease showed no significant association, despite the high point estimates. Future studies with larger sample sizes would be preferable.

Conclusion

From the early to the community-transmission phases of COVID-19, mental health among Japanese people deteriorated. Therefore, it can be suggested that mental health measures be implemented together with protective measures against COVID-19 infection. In particular, high priority should be given to low-income people and those with underlying diseases, who may be prone to deterioration of mental health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from Meiji Yasuda Life Foundation of Health and Welfare. We thank Dr Koh Yong Mo at LightStone Corp for his beneficial comment for authors. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Published 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- 2.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng S, Shi J, Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower society. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):e37–e38. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30309-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly BD. Covid-19 (Coronavirus): Challenges for Psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;217(1):352–353. 10.1192/bjp.2020.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510–512. 10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):468–471. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong L, Bouey J. Public mental health crisis during COVID-19 pandemic, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1616–1618. 10.3201/eid2607.200407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52(March):102066. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary Research Priorities for the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Call for Action for Mental Health Science Elsevier; 2020. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:40–48. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian F, Li H, Tian S, Yang J, Shao J, Tian C. Psychological symptoms of ordinary Chinese citizens based on SCL-90 during the level I emergency response to COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112992. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Machida M, Nakamura I, Saito R, et al. Adoption of personal protective measures by ordinary citizens during the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:139–144. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. Responses on the Coronavirus Disease 2019. http://japan.kantei.go.jp/ongoingtopics/_00013.html, 2020. Published 2020.

- 15.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han B, Gfroerer JC, Colpe LJ, Barker PR, Colliver JD. Serious psychological distress and mental health service use among community-dwelling older U.S. adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(3):291–298. 10.1176/ps.62.3.pss6203_0291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pratt LA. Serious psychological distress, as measured by the K6, and mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(3):202–209. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kikuchi H, Takamiya T, Odagiri Y, Ohya Y, Shimomitsu T, Inoue S. Mental illness and a high-risk, elderly Japanese population: Characteristic differences related to gender and residential location. Psychogeriatrics. 2013;13(4):229–236. 10.1111/psyg.12026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanji F, Tomata Y, Zhang S, Otsuka T, Tsuji I. Psychological distress and completed suicide in Japan: A comparison of the impact of moderate and severe psychological distress. Prev Med (Baltim). 2018;116:99–103. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17(3):152–158. 10.1002/mpr.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, Andrews G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychol Med. 2003;33(2):357–362. 10.1017/S0033291702006700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. A random-effects ordinal regression model for multilevel analysis. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):933–944. 10.2307/2533433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Academy of Medical Sciences. Survey results: Understanding people’s concerns about the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. http://www.acmedsci.ac.uk/COVIDmentalhealthsurveys. Published 2020. Accessed April 26, 2020.

- 24.Wasserman IM. The impact of epidemic, war, prohibition and media on suicide: United States, 1910–1920. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992;22(2):240–254. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1992.tb00231.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Basic policies for novel coronavirus disease control by the government of Japan. 2020. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000617686.pdf.

- 26.Yip PSF, Cheung YT, Chau PH, Law YW. The impact of epidemic outbreak: The case of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and suicide among older adults in Hong Kong. Crisis. 2010;31(2):86–92. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication of Japan (MIC). White Paper on Information and Communications in Japan 2019; 2019. https://www.soumu.go.jp/johotsusintokei/whitepaper/eng/WP2019/2019-index.html. Accessed July 11, 2020.

- 28.The Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions, 2010 2011. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa10/dl/gaikyou.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2020.