Abstract

New classification systems based on molecular features have been introduced to improve precision medicine for prostate cancer (PCa). This review covers the increasing risk of PCa and the differences in response to targeted therapy that are related to specific gene variations. We believe that genomic evaluations will be useful for guiding PCa risk stratification, screening, and treatment. We searched the PubMed and MEDLINE databases for articles related to genomic testing for PCa that were published in 2020 or earlier. There is increasing evidence that germline mutations in DNA repair genes, such as BRCA1/2 or ATM, are closely related to the development and aggressiveness of PCa. Targeted prostate-specific antigen screening based on the presence of germline alterations in DNA repair genes is recommend to achieve an early diagnosis of PCa. In cases of localized PCa, even if it has a favorable risk classification, patients under active surveillance with these gene alterations are likely to develop aggressive PCa. Thus, active treatment may be preferable to active surveillance for these patients. In cases of metastatic castration–resistant PCa, BRCA1/2 and DNA mismatch repair genes may be useful biomarkers for predicting the response to androgen receptor–targeting agents, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors, platinum chemotherapy, prostate-specific membrane antigen–targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and radium-223. Genomic evaluations may allow for risk stratification of patients with PCa based on their molecular features, which may help guide precision medicine for treating PCa.

Keywords: Castration resistant, Genetic testing, Prostate cancer, Prostatic neoplasms, Screening, Treatment

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is common among men, and its incidences have been increasing during recent decades [1]. Similar to ovarian and breast cancers, a significant proportion of PCa cases are related to genetic factors [2,3]. Thus, there has been increasing discussion regarding genomic evaluations for PCa, as 8–12% of patients with PCa have germline mutations in tumor suppressor genes [4]. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has traditionally guided the diagnosis and treatment of PCa, although there is a need for new biomarkers to guide the early detection of PCa and the selection of effective treatment for advanced PCa [5].

The genomic landscapes for localized PCa and advanced PCa have recently been published. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network reported results for whole-exome sequencing of localized PCa (26% of the cohort had a Gleason score of 8) and noted that harmful germline or somatic mutations were relatively common in DNA damage repair genes (BRCA1, BRCA2, CDK12, ATM, FANCD2, and RAD51C) [6]. Whole-exome sequencing was also performed for the first time to provide genomic information regarding advanced PCa [7]. Robinson et al. [8] performed an integrated genomic analysis of 150 patients with metastatic castration–resistant PCa (mCRPC), which revealed frequent aberrations in AR (62.7%), TP53 (53.3%), and PTEN (40.7%). Furthermore, they found that the rates of aberrations in AR and TP53 were higher for CRPC than for primary PCa and that CRPC was associated with frequent alterations of DNA repair genes, such as BRCA1/2 or ATM. Thus, genomic evaluations may be useful for the early detection of PCa, identifying high-risk PCa, and selecting appropriate treatment strategies [4,9,10].

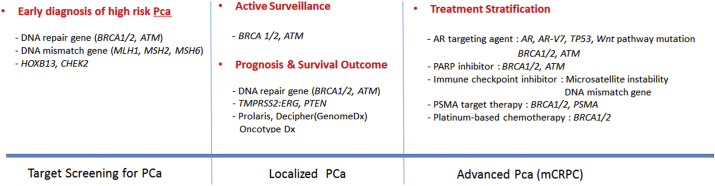

Information from genomic testing is provided to patients and their physicians, which makes it important to understand its clinical implications. Therefore, we performed this review to investigate the clinical implications of genomic evaluations for PCa risk stratification, screening, and treatment (Fig. 1). The PubMed and MEDLINE databases were searched for articles related to genomic testing for PCa that were published in 2020 or earlier.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram showing clinical application of the genomic evaluation for prostate cancer screening and treatment.

2. Genomic evaluations in PCa screening

Screening strategies have been developed to identify PCa and improve survival outcomes, while avoiding overdiagnosis and overtreatment [11]. Recent studies have indicated that alterations in PCa susceptibility gene increase the risk of PCa (Table 1). In particular, high-grade malignant PCa frequently occurs at an early age in patients with alterations in DNA repair genes, such as BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, CHEK2, HOXB13, PALB2, and RAD51D [12, 13, 14].

Table 1.

Implications of molecular biomarkers for screening and treatment of localized prostate cancer.

| Author (year) | No. of patients (n) | Surrogate marker | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCa screening | |||

| Leongamornlert et al. (2012) [15] | 913 | Germline BRCA1 mutation | Increased risk of PCa. |

| Edward et al. (2003) [18] | 263 | Germline BRCA2 mutation | Increased risk of PCa at an early age |

| Agalliu et al. (2007) [19] | 290 | Protein-truncating BRCA2 mutation | Increased risk of early-onset PCa |

| Kote-Jarai et al. (2011) [20] | 1864 | Germline BRCA2 mutation | Increased risk of PCa by age 65 |

| Ewing et al. (2012) [23] | 5083 | HOXB13 G84E variant | Increased risk of hereditary PCa |

| Karlsson et al. (2014) [25] | 9696 | Germline HOXB13 G84E mutation | Increased risk of PCa. |

| Naslund-Koch et al. (2016) [26] | 86975 | CHEK2∗1100delC germline mutation | Increased risk of PCa. |

| Page et al. (2019) [31] | 3027 | Germline BRCA2 mutation | Increased risk of PCa, younger age of diagnosis, clinically significant tumors. |

| Nyberg (2020) [29] | 823 | Germline BRCA1/2 mutation | Increased risk of aggressive PCa. |

| Active surveillance | |||

| Carter et al. (2019) [42] | 1211 | Germline BRCA1/2, ATM mutation | Increased risk of grade reclassification and aggressive PCa. |

| Prognosis | |||

| Castro et al. (2015) [43] | 1302 | Germline BRCA mutation | BRCA carriers treated with RT have significantly shorter MFS and CSS than those who underwent RP. |

| Castro et al. (2013) [21] | 2019 | Germline BRCA1/2 mutation | Increased risk of aggressive PCa with a nodal involvement and distant metastasis. |

| Leinonen et al. (2013) [49] | 284 | PTEN loss, TMPRSS2:ERG | Shorter progression-free survival |

| Wu et al. (2020) [41] | 1694 | Germline ATM, BRCA2, MSH2 mutations | Associated with grade group 5 PCa |

CSS, cancer-specific survival; MFS, metastasis free survival; PCa, prostate cancer; RP, radical prostatectomy; RT, radiation therapy.

2.1. BRCA1 and BRCA2

Alterations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are associated with the development of melanoma, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer. Alterations in BRCA1 (chromosome 17q21) are associated with a 1.8–4.5 times higher risk of developing PCa by the age of 65 years, while alterations in BRCA2 (chromosome 13q12.3) are associated with a 2.5–8.6 times higher risk of developing PCa [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Moreover, PCa with BRCA1 or BRCA2 alterations is more likely to involve a Gleason score of ≥8 (vs. sporadic PCa) and is reportedly associated with high incidences of lymph node involvement and metastasis [21].

2.2. ATM

The ATM gene is involved in the DNA damage response, and germline alterations in ATM are associated with an increased risk of developing PCa or metastasis (vs. sporadic PCa) [22].

2.3. HOXB13

Homeobox B13 (HOXB13, chromosome 17q21.32) is a tumor suppressor gene that has very high penetrance characteristics. Approximately, 60% of men with HOXB13 mutations will develop PCa by the age of 80 years [23, 24, 25].

2.4. CHEK2

The CHEK2 gene encodes a cell cycle checkpoint protein kinase that regulates TP53 and DNA repair. Germline alterations in CHEK2 are associated with increased risks of breast, colon, thyroid, kidney, and prostate cancers [26].

2.5. DNA mismatch repair genes

The mismatch repair genes include MLH1 (chromosome 3p21.3), MSH2 (chromosome 2p21), and MSH6 (chromosome 2p16). Mutations in these genes are associated with Lynch syndrome, which is a hereditary multicancer syndrome that is characterized by nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Furthermore, carriers of mutations in these genes have a 3.67 times higher risk of PCa (95% confidence interval: 2.3–6.6×), relative to noncarriers [14].

Approximately, 5–10% of PCa cases involve hereditary PCa, in which genetic variations are passed on to the patient's offspring [14]. Although there is no consensus regarding PCa screening and management in this high-risk population, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend genetic testing if a man has a family history of hereditary breast cancer, ovarian cancer, PCa, or Lynch syndrome [27]. Furthermore, guidelines for the early detection of PCa recommend screening from the age of 45 years if the patient has BRCA1 alterations, BRCA2 alterations, or a family history of hereditary breast or ovarian cancers. Prostate biopsy is also recommended if the patient has suspicious examination findings or a PSA concentration of ≥3 ng/mL [27,28].

Many studies have also indicated that carriers of BRCA2 alterations are more likely to develop aggressive and metastatic PCa at a young age, relative to noncarriers [20,21,29]. Thus, targeted screening based on BRCA1 or BRCA2 status has been recognized as useful for achieving an early diagnosis of PCa. The IMPACT study has been underway since 2014 to confirm the role of BRCA1 or BRCA2 in PCa screening [30,31] and was the first prospective study to use germline genetic markers for identifying men with a high risk of PCa. The preliminary results revealed that targeted PSA screening based on the BRCA genotype can achieve early detection of aggressive PCa, as carriers of BRCA2 alterations were diagnosed with PCa at a younger age than noncarriers (61 years vs. 64 years; P = 0.04) and had a higher rate of clinically significant cancer (77% vs. 4%; P = 0.01). Although systematic PSA screening is useful for men with BRCA2 alterations, the significance of BRCA1 alterations is less clear and we await the final results to help guide the development of an optimal screening strategy [30,31].

3. Genomic evaluations for localized PCa

In the era of PSA screening, most men present with localized and potentially curable PCa. However, there is a broad spectrum of localized PCa cases, ranging from entirely indolent to cancer that requires aggressive treatment. Furthermore, approximately 30% of men will experience recurrence despite receiving radiotherapy or surgery for PCa [32]. Fraser et al. have reported that no single gene was mutated at a frequency of >10% in localized PCa [33], although alterations in DNA damage repair genes are closely related to aggressive behavior of localized PCa and cancer-specific mortality [20,21,34]. Moreover, patients with PCa that involves inherited mutations in BRCA1/BRCA2 or ATM are more likely to die because of PCa at a young age [11]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines have also addressed genetic testing for men with PCa (Gleason score of ≥7) and specific family history features [27]. Therefore, better understanding of the genetic factors that drive aggressive PCa may help identify subtypes of localized PCa and guide effective treatment selection.

3.1. Active surveillance

Active surveillance (AS) is one option for patients with a favorable PCa risk profile [35,36], although it can be difficult to select AS candidates because poor outcomes are still observed among patients with a favorable PCa risk profile. Furthermore, patients may miss the opportunity to receive effective treatments in a timely manner if they are misclassified at the time of diagnosis [37]. Therefore, it is very important to accurately identify patients with a high risk of developing lethal PCa during AS. Many nomograms based on clinical data have been developed to predict the course of PCa [38, 39, 40], although the addition of genomic information may help more accurately identify indolent and lethal PCa. Wu et al. [41] reported that germline pathogenic mutations in DNA repair genes were strongly associated with PCa in grade group (GG) 5, and the risk of reclassification increased when patients with these germline mutations were undergoing AS (Table 1). Carter et al. [42] also reported that men undergoing AS with inherited mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATM were more likely to have aggressive PCa and that carriers of BRCA2 mutations had a 5 times higher risk of reclassification from GG 1 to GG > 3 (vs. noncarriers). Therefore, when selecting patients for AS, urologists should consider the presence of germline alterations in BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATM, as these patients may be more likely to develop aggressive PCa.

3.2. The response of BRCA mutant carriers to conventional treatments for localized PCa

A recent study of localized PCa revealed a difference in the survival rate after radical prostatectomy or external beam radiation therapy according to the presence or absence of BRCA1 or BRCA2 alterations [21,43]. For example, relative to noncarriers, carriers of germline BRCA2 mutations had significantly lower metastasis-free survival rates at 5 years (94% vs. 72%) and at 10 years (84% vs. 50%, p < 0.001). Moreover, carriers had significantly lower cancer-specific survival (CSS) rates at 5 years (94% vs. 76%) and at 10 years (84% vs. 61%, p < 0.001). However, it is interesting that there was no significant difference in the CSS rates after radical prostatectomy between BRCA2 mutation carriers and noncarriers, although a significant difference in CSS after radiotherapy was observed between BRCA2 mutation carriers and noncarriers [43]. Thus, the poorer survival outcomes for carriers of germline BRCA2 mutations may be more relevant among patients who receive radiotherapy [44]. Nevertheless, that study only evaluated a small sample of patients and that their characteristics were not balanced.

3.3. Molecular biomarkers not related to DNA repair genes

Treatment decisions for localized PCa can also be guided by evaluation of the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion gene, PTEN status, the Prolaris test for cell cycle progression genes, the Decipher test (GenomeDx), and the Oncotype DX Genomic Prostate Score [5,45]. A meta-analysis of 5,074 patients who underwent radical prostatectomy revealed that the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion gene was not associated with biochemical recurrence (BCR) or mortality [46]. However, fusion status is considered a key genomic event that should be taken into consideration when the prognostic value of genomic biomarkers is being investigated [45,47,48]. For example, loss of PTEN is associated with a high risk of BCR but is only associated with shorter progression-free survival in ERG-positive cases [49,50]. Genomic panels include the Prolaris test (46 genes), the Decipher genetic test (GenomeDX, 22 genes), and the Oncotype DX Genomic Prostate Score (17 genes), which can be used to predict the risk of BCR and metastatic progression after radical prostatectomy [51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58]. A recent study evaluated whether results from the Prolaris test influenced the treatment selection for patients diagnosed with localized PCa, which revealed that the treatment was changed in 65% of the cases based on the genomic evaluation, with a lower treatment burden in 40% of the cases [59]. These results indicate that genomic evaluations can significantly influence treatment selection.

4. Genomic evaluation for mCRPC

Treatment for mCRPC has improved significantly over the last decade, although there remains controversy regarding the optimal treatment selection algorithms, based on the substantial heterogeneity in treatment responses [60]. Therefore, it would be useful to identify biomarkers for predicting treatment responses, and substantial effort has been dedicated to achieving treatment stratification through genomic evaluations (Table 2). Given the implications for treatment selection, some experts have suggested routine genomic evaluations for all men with mCRPC [4,9,22]. Furthermore, approximately 90% of patients with mCRPC harbor clinically actionable molecular alterations, which frequently involve AR (62%), the ETS family (56.7%), TP53 (53.3%), and PTEN (40.7%). In addition, aberrations have been observed in the PI3K pathway (49%), the DNA repair pathway (19%), CDK inhibitors (7%), and the Wnt pathway (5%). Finally, aberrations in BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATM have been observed in approximately 20% of patients with mCRPC [8].

Table 2.

Implications of molecular biomarkers for treatment of mCRPC.

| Author (year) | No. of patients (n) | Surrogate marker | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| AR-targeting agent | |||

| Antonarakis et al. (2014) [63] | 62 | CTC-based AR-V7 | Increased risk of resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone |

| De Laere et al. (2019) [68] | 168 | CTC-based TP53 alteration | TP53 alteration is superior to any AR-derived marker in predicting AR-targeting agent responsiveness |

| Isaacsson et al. (2020) [70] | 137 | Somatic Wnt-activating mutations | Decrease the effectiveness of abiraterone and enzalutamide |

| Chung et al. (2019) [69] | 37 | CTC-based AR, AR-V7, PSCA, NKX3.1, Wnt5b, PSA | Decrease the effectiveness of abiraterone and enzalutamide |

| Annala et al. (2017) [71] | 319 | Germline ctDNA-based DNA repair defects | Attenuated responses to abiraterone and enzalutamide |

| Antonarakis et al. (2018) [72] | 172 | Germline BRCA1/2, ATM | Increase the effectiveness of abiraterone and enzalutamide |

| PARP inhibitor | |||

| Mateo et al. (2015) [76] | 50 | BRCA1/2, ATM, CHEK2, PALB2, FANCA and HDAC2 alteration | Increased responses to PARP inhibitors olaparib |

| Abida et al. (2020) [77] | 78 | ATM, CDK12, CHEK2 | Limited responses to PARP inhibitor rucaparib |

| Marshall et al. (2019) [78] | 23 | Germline or somatic ATM mutation | Do not respond as well as men with BRCA1/2 mutation |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitor | |||

| Le et al. (2017) [79] | 86 | Germline mismatch repair deficiency (MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and MLH1) | Sensitive to immune checkpoint blockade |

| Antonarakis et al. (2019) [80] | 127 | MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2 | Anecdotal sensitivity to PD-1 inhibitors, pembrolizumab |

| PSMA target therapy | |||

| Paschalis et al. (2019) [85] | 60 | DNA repair defects | High mPSMA expression and may respond better to PSMA targeting treatments |

| Crumbaker et al. (In press) [86] | Case report | Biallelic BRCA2 inactivation | Exceptional response to PSMA target therapy |

| Platinum-based chemotherapy | |||

| Cheng et al. (2016) [89] | Case series | Biallelic BRCA2 inactivation | Increased response to platinum-based chemotherapy |

| Pomerantz et al. (2017) [90] | 141 | Germline BRCA2 | Increased response to platinum-based chemotherapy |

| Zafeiriou et al. (2019) [91] | Case series | DNA repair defects (BRCA2, ATM) | Increased response to platinum-based chemotherapy |

| Radium-223 | |||

| Isaacsson et al. (2019) [95] | 190 | BRCA2, ATM, CHEK2, ATR, FANCI, FANCL and PALB2) | Increased response to radium-223 |

| Van et al. (2020) [96] | 93 | DNA repair defects (BRCA2, ATM, CDK12) | Increased response to radium-223 |

CTC, circulating tumor cell; mCRPC, metastatic castration–resistant PCa; PCa, prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PSCA, prostate stem cell antigen.

4.1. Androgen axis agents

Androgen receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSIs), such as abiraterone or enzalutamide, are options for treating patients with mCRPC. However, approximately 30–40% of these patients do not respond to ARSI treatment or develop resistance within a brief period of time [61, 62, 63]. The AR variant 7 (AR-V7) has been suggested as a biomarker for predicting response to ARSI treatment, although AR-V7–positive patients account for only a small percentage of ARSI nonresponders and subsets of AR-V7–positive patients do respond to ARSI treatment [64,65]. Given the lack of clear data, a recent consensus statement indicated that there is insufficient evidence to support the implementation of AR-V7 testing in clinical practice [66,67]. Nevertheless, inactivation of TP53 is superior to any AR-derived biomarker for predicting ARSI responsiveness, and it has been reported that the TP53 status can be used to predict a good or poor prognosis for 50–55% of patients with mCRPC undergoing ARSI treatment [68].

In addition to AR signaling–based markers, genes related to the Wnt pathway, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and stemness have potential clinical relevance in PCa [69,70]. Furthermore, the response to ARSI treatment may vary according to the presence of germline alterations in DNA repair genes [71,72], which occur in 8–12% of patients with mCRPC [3,8,22]. Patients with BRCA2 germline mutations are also generally known to have a poor prognosis, and Annala et al. [71] have suggested that carriers of these mutations with mCRPC also experience a poor response to therapies targeting the AR signaling axis. However, conflicting evidence has also been published, as carriers of germline BRCA/ATM alterations had a better response to ARSI treatment, relative to noncarriers [72]. Thus, further studies are needed to address these conflicting results.

4.2. Poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (olaparib and rucaparib)

In 2005, a novel inhibitor of poly[adenosine diphosphate-ribose] polymerase (KU-0059436) was reported to specifically kill cell lines with silenced or lost BRCA1/2 expression [73,74]. The US Food and Drug Administration subsequently approved the use of olaparib (a poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor) for treating patients with mCRPC who harbored BRCA1, BRCA2, or ATM alterations and had previously received taxane-based chemotherapy or ARSI treatment. Several landmark studies demonstrated that PARP inhibitors were associated with an increased response rate in men with mCRPC harboring BRCA1/2 alterations [75,76]. The TOPARP-A trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01682772) also revealed that 88% of patients with BRCA1/2 alterations responded to PARP inhibitors, although only 6% of patients without these alterations responded to PARP inhibitors. Nevertheless, preliminary results from the TRITON2 study revealed that men with mCRPC harboring ATM mutations did not respond as well to rucaparib as men harboring BRCA1/2 alterations [77]. Similarly, patients with mCRPC and ATM mutations had a lower rate of response to olaparib treatment than patients with BRCA1/2 mutations [78]. Therefore, alternative treatments are needed for patients with ATM mutations.

4.3. Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Patients with several cancers, including Lynch syndrome, are known to be sensitive to immune checkpoint inhibitors if they have microsatellite instability or DNA mismatch repair gene alterations [79]. The US Food and Drug Administration has recently approved the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab, for treating solid tumors with mismatch repair deficiency, which suggests that genomic evaluations have become an essential step in guiding cancer treatment [9,79]. Antonarakis et al. [80] have also anecdotally reported that patients with mismatch repair gene–mutated advanced PCa appear to respond to PD-1 inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab. However, the role of PD-1/PDL-1 in mCRPC remains unclear, and there is limited evidence regarding an exceptional response in the presence of microsatellite instability [14].

4.4. PSMA-targeted treatment

Radiolabeled anti-PSMA therapies, such as 177 Lu-PSMA-617, are well tolerated and lead to a 50% reduction in PSA concentrations in 30–60% of patients with mCRPC, although 30% of patients do not respond to anti-PSMA treatment at all [81, 82, 83, 84]. Interestingly, patients with mCRPC and DNA repair gene alterations have much higher membranous PSMA expression than those without alterations, which may help identify patients who are more likely to respond to anti-PSMA treatment [85,86].

4.5. Platinum-based chemotherapy

Platinum chemotherapy is rarely used to treat PCa, except in cases involving neuroendocrine differentiation [87]. However, previous studies have shown that BRCA1/2 alterations may predict the response to platinum-based chemotherapy in cases of breast and ovarian cancer [87,88]. Even in patients with mCRPC, germline alterations in DNA repair genes are associated with the response to platinum-based chemotherapy, especially in patients with mCRPC and BRCA2 alterations [89, 90, 91].

4.6. Radium-223

Radium-223 is an alpha particle emitter that is a therapeutic option for patients with mCRPC and symptomatic bone metastases and no visceral metastases [92]. It selectively targets the bone microenvironment and emits high-energy alpha particles that cause double-strand DNA breaks [91,93], which exert potent localized cytotoxic effects [94]. Patients harboring aberrations in DNA repair genes experience a greater benefit from radium-223, relative to patients without these mutations [95,96].

5. Conclusion

There is accumulating evidence that germline alterations in DNA repair genes, including BRCA1/2 and ATM, are associated with increased risks of developing early onset and/or high-risk PCa. These molecular markers may have a profound influence on the diagnosis and treatment of PCa, especially in terms of selecting and sequencing targeted therapy for patients with mCRPC. While these markers have not been incorporated into clinical decision-making processes at this time, genomic evaluations may help guide these processes in borderline cases where additional information would be useful.

Conflicts of interest

All the authors declare no potential conflict of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) , which is funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2018R1C1B6004574), South Korea.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Canc J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liss M.A., Chen H., Hemal S., Krane S., Kane C.J., Xu J. Impact of family history on prostate cancer mortality in white men undergoing prostate specific antigen based screening. J Urol. 2015;193:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leongamornlert D., Saunders E., Dadaev T., Tymrakiewicz M., Goh C., Jugurnauth-Little S. Frequent germline deleterious mutations in DNA repair genes in familial prostate cancer cases are associated with advanced disease. Br J Canc. 2014;110:1663–1672. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhen J.T., Syed J., Nguyen K.A., Leapman M.S., Agarwal N., Brierley K. Genetic testing for hereditary prostate cancer:Current status and limitations. Cancer. 2018;124:3105–3117. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGrath S., Christidis D., Perera M., Hong S.K., Manning T., Vela I. Prostate cancer biomarkers: Are we hitting the mark? Prostate Int. 2016;4:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.prnil.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network The molecular taxonomy of primary prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;163:1011–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grasso C.S., Wu Y.M., Robinson D.R., Cao X., Dhanasekaran S.M., Khan A.P. The Mutational Landscape of Lethal Castrate Resistant Prostate Cancer. Nature. 2012;487:239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson D., Van Allen E.M., Wu Y.-M., Schultz N., Lonigro R.J., Mosquera J.-M. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giri V.N., Knudsen K.E., Kelly W.K., Abida W., Andriole G.L., Bangma C.H. Role of Genetic Testing for Inherited Prostate Cancer Risk: Philadelphia Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference 2017. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:414–424. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das S., Salami S.S., Spratt D.E., Kaffenberger S.D., Jacobs M.F., Morgan T.M. Bringing Prostate Cancer Germline Genetics into Clinical Practice. J Urol. 2019;202:223–230. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loeb S., Bjurlin M.A., Nicholson J., Tammela T.L., Penson D.F., Carter H.B. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65:1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.12.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Na R., Zheng S.L., Han M., Yu H., Jiang D., Shah S. Germline Mutations in ATM and BRCA1/2 Distinguish Risk for Lethal and Indolent Prostate Cancer and are Associated with Early Age at Death. Eur Urol. 2017;71:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grindedal E.M., Møller P., Eeles R., Stormorken A.T., Bowitz-Lothe I.M., Landrø S.M. Germ-line mutations in mismatch repair genes associated with prostate cancer. Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers prev. 2009;18:2460–2467. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan S., Jenkins M.A., Win A.K. Risk of prostate cancer in Lynch syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers prev. 2014;23:437–449. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leongamornlert D., Mahmud N., Tymrakiewicz M., Saunders E.T., Dadaev T., Castro E. Germline BRCA1 mutations increase prostate cancer risk. Br J Canc. 2012;106:1697–1701. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson D., Easton D.F. Cancer incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1358–1365. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.18.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Asperen C.J., Brohet R.M., Meijers-Heijboer E.J., Hoogerbrugge N., Verhoef S., Vasen H.F. Cancer risks in BRCA2 families: estimates for sites other than breast and ovary. J Med Genet. 2005;42:711–719. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards S.M., Kote-Jarai Z., Meitz J., Hamoudi R., Hope Q., Osin P. Two percent of men with early-onset prostate cancer harbor germline mutations in the BRCA2 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1–12. doi: 10.1086/345310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agalliu I., Karlins E., Kwon E.M., Iwasaki L.M., Diamond A., Ostrander E.A. Rare germline mutations in the BRCA2 gene are associated with early-onset prostate cancer. Br J Canc. 2007;97:826–831. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kote-Jarai Z., Leongamornlert D., Saunders E., Tymrakiewicz M., Castro E., Mahmud N. BRCA2 is a moderate penetrance gene contributing to young-onset prostate cancer: implications for genetic testing in prostate cancer patients. Br J Canc. 2011;105:1230–1234. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castro E., Goh C., Olmos D., Saunders E., Leongamornlert D., Tymrakiewicz M. Germline BRCA mutations are associated with higher risk of nodal involvement, distant metastasis, and poor survival outcomes in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1748–1757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pritchard C.C., Mateo J., Wals h MF., De Sarkar N., Abida W., Beltran H. Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ewing C.M., Ray A.M., Lange E.M., Zuhlke K.A., Robbins C.M., Tembe W.D. Germline mutations in HOXB13 and prostate-cancer risk. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:141–149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacInnis R.J., Severi G., Baglietto L., Dowty J.G., Jenkins M.A., Southey M.C. Population-based estimate of prostate cancer risk for carriers of the HOXB13 missense mutation G84E. PloS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054727. e54727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlsson R., Aly M., Clements M., Zheng L., Adolfsson J., Xu J. A population-based assessment of germline HOXB13 G84E mutation and prostate cancer risk. Eur Urol. 2014 Jan;65(1):169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naslund-Koch C., Nordestgaard B.G., Bojesen S.E. Increased risk for other cancers in addition to breast cancer for CHEK2∗1100delC heterozygotes estimated from the Copenhagen General Population Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1208–1216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daly M.B., Pilarski R., Berry M., Buys S.S., Farmer M., Friedman S. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Genetic Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian (Version 2.2017) J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:9–20. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carroll P.R., Parsons J.K., Adriole G., Bahnson R.R., Castle E.P., Catalona W.J. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Prostate Cancer Early Detection, Version 2.2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:509–519. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nyberg T., Frost D., Barrowdale D., Evans D.G., Bancroft E., Adlard J. Prostate Cancer Risks for Male BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: A Prospective Cohort Study. Eur Urol. 2020;77:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bancroft E.K., Page E.C., Castro E., Lilja H., Vickers A., Sjoberg D. Targeted prostate cancer screening in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the initial screening round of the IMPACT study. Eur Urol. 2014;66:489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Page E.C., Bancroft E.K., Brook M.N., Assel M., Hassan Al Battat M., Thomas S. Interim Results from the IMPACT Study: Evidence for Prostate-specific Antigen Screening in BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. Eur Urol. 2019;76:831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buyyounouski M.K., Pickles T., Kestin L.L., Allison R., Williams S.G. Validating the interval to biochemical failure for the identification of potentially lethal prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1857–1863. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fraser M., Sabelnykova V.Y., Yamaguchi T.N., Heisler L.E., Livingstone J., Huang V. Genomic hallmarks of localized, non-indolent prostate cancer. Nature. 2017;541:359–364. doi: 10.1038/nature20788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallagher D.J., Gaudet M.M., Pal P., Kirchhoff T., Balistreri L., Vora K. Germline BRCA mutations denote a clinicopathologic subset of prostate cancer. Clin Canc Res. 2010;16:2115–2121. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanda M.G., Cadeddu J.A., Kirkby E., Chen R.C., Crispino T., Fontanarosa J. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline. Part I. Risk stratification, shared decision making, and care options. J Urol. 2018;199:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen R.C., Rumble R.B., Loblaw D.A., Finelli A., Ehdaie B., Cooperberg M.R. Active surveillance for the management of localized prostate cancer (Cancer Care Ontario Guideline): American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2182–2190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto T., Musunuru B., Vesprini D., Zhang L., Ghanem G., Loblaw A. Metastatic prostate cancer in men initially treated with active surveillance. J Urol. 2016;195:1409–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chun F.K., Haese A., Ahyai S.A., Walz J., Suardi N., Capitanio U. Critical assessment of tools to predict clinically insignificant prostate cancer at radical prostatectomy in contemporary men. Cancer. 2008;113:701–709. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung J.S., Choi H.Y., Song H.R., Byun S.S., Seo S.I., Song C. Nomogram to predict insignificant prostate cancer at radical prostatectomy in Korean men: a multi-center study. Yonsei Med J. 2011;52:74–80. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2011.52.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shukla-Dave A., Hricak H., Akin O., Yu C., Zakian K.L., Udo K. Preoperative nomograms incorporating magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy for prediction of insignificant prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012;109:1315–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Y., Yu H., Li S., Wiley K., Zheng S.L., LaDuca H. Rare Germline Pathogenic Mutations of DNA Repair Genes Are Most Strongly Associated with Grade Group 5 Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2020;3:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carter H.B., Helfand B., Mamawala M., Wu Y., Landis P., Yu H. Germline Mutations in ATM and BRCA1/2 Are Associated with Grade Reclassification in Men on Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;75:743–749. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castro E., Goh C., Leongamornlert D., Saunders E., Tymrakiewicz M., Dadaev T. Effect of BRCA mutations on metastatic relapse and cause-specific survival after radical treatment for localised prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mateo J., Boysen G., Barbieri C.E., Bryant H.E., Castro E., Nelson P.S. DNA Repair in Prostate Cancer: Biology and Clinical Implications. Eur Urol. 2017;71:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boström P.J., Bjartell A.S., Catto J.W., Eggener S.E., Lilja H., Loeb S. Genomic Predictors of Outcome in Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:1033–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pettersson A., Graff R.E., Bauer S.R., Pitt M.J., Lis R.T., Stack E.C. The TMPRSS2:ERG rearrangement, ERG expression, and prostate cancer outcomes: a cohort study and meta-analysis. Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1497–1509. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karnes R.J., Cheville J.C., Ida C.M., Sebo T.J., Nair A.A., Tang H. The ability of biomarkers to predict systemic progression in men with high-risk prostate cancer treated surgically is dependent on ERG status. Canc Res. 2010;70:8994–9002. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gasi Tandefelt D., Boormans J.L., van der Korput H.A., Jenster G.W., Trapman J. A 36-gene signature predicts clinical progression in a subgroup of ERG-positive prostate cancers. Eur Urol. 2013;64:941–950. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leinonen K.A., Sarama ¨ki O.R., Furusato B., Kimura T., Takahashi H., Egawa S. Loss of PTEN is associated with aggressive behavior in ERG-positive prostate cancer. Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:2333–2344. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0333-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshimoto M., Joshua A.M., Cunha I.W., Coudry R.A., Fonseca F.P., Ludkovski O. Absence of TMPRSS2:ERG fusions and PTEN losses in prostate cancer is associated with a favorable outcome. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1451–1460. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cooperberg M.R., Simko J.P., Cowan J.E., Reid J.E., Djalilvand A., Bhatnagar S. Validation of a cell-cycle progression gene panel to improve risk stratification in a contemporary prostatectomy cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1428–1434. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.4396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bishoff J.T., Freedland S.J., Gerber L., Tennstedt P., Reid J., Welbourn W. Prognostic utility of the cell cycle progression score generated from biopsy in men treated with prostatectomy. J Urol. 2014;192:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Erho N., Crisan A., Vergara I.A., Mitra A.P., Ghadessi M., Buerki C. Discovery and validation of a prostate cancer genomic classifier that predicts early metastasis following radical prostatectomy. PloS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066855. e66855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ross A.E., Feng F.Y., Ghadessi M., Erho N., Crisan A., Buerki C. A genomic classifier predicting metastatic disease progression inmenwith biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17:64–69. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2013.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karnes R.J., Bergstralh E.J., Davicioni E., Ghadessi M., Buerki C., Mitra A.P. Validation of a genomic classifier that predictsmetastasis following radical prostatectomy in an at risk patient population. J Urol. 2013;190:2047–2053. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Den R.B., Feng F.Y., Showalter T.N., Mishra M.V., Trabulsi E.J., Lallas C.D. Genomic prostate cancer classifier predicts biochemical failure and metastases in patients after postoperative radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89:1038–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klein E.A., CooperbergMR, Magi-Galluzzi C., Simko J.P., Falzarano S.M., Maddala T. A 17-gene assay to predict prostate cancer aggressiveness in the context of Gleason grade heterogeneity, tumor multifocality, and biopsy undersampling. Eur Urol. 2014;66:550–560. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cullen J., Rosner I.L., Brand T.C., Zhang N., Tsiatis A.C., Moncur J. A biopsy-based 17-gene Genomic Prostate Score predicts recurrence after radical prostatectomy and adverse surgical pathology in a racially diverse population of men with clinically low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crawford E.D., Scholz M.C., Kar A.J., Fegan J.E., Haregewoin A., Kaldate R.R. Cell cycle progression score and treatment decisions in prostate cancer: results from an ongoing registry. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:1025–1031. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.899208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lorente D., Mateo J., Perez-Lopez R., de Bono J.S., Attard G. Sequencing of agents in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e279–e292. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Bono J.S., Logothetis C.J., Molina A., Fizazi K., North S., Chu L. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scher H.I., Fizazi K., Saad F., Taplin M.E., Sternberg C.N., Miller K. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Antonarakis E.S., Lu C., Wang H., Luber B., Nakazawa M., Roeser J.C. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1028–1038. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scher H.I., Graf R.P., Schreiber N.A., McLaughlin B., Lu D., Louw J. Nuclear-specific AR-V7 protein localization is necessary to guide treatment selection in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71:874–882. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bernemann C., Schnoeller T.J., LuedekeM, Steinestel K., BoegemannM, Schrader A.J. Expression of AR-V7 in circulating tumour cells does not preclude response to next generation androgen deprivation therapy in patients with castration resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steinestel J., Bernemann C., Schrader A.J., Lennerz J.K. Re: Antonarakis ES, Lu C, et al. Re: Emmanuel S. Antonarakis, Changxue Lu, Brandon Luber, et al. Clinical significance of androgen receptor splice variant-7mRNA detection in circulating tumor cells of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with first- and second-line abiraterone and enzalutamide. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2149–56: AR-V7 testing:what's in it for the patient? Eur Urol. 2017;72:e168–e169. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gillessen S., Attard G., Beer T.M., Beltran H., Bossi A., Bristow R. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer: the report of the Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference APCCC 2017. Eur Urol. 2018;73:178–211. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Laere B., Oeyen S., Mayrhofer M., Whitington T., van Dam P.J., Van Oyen P. TP53 Outperforms Other Androgen Receptor Biomarkers to Predict Abiraterone or Enzalutamide Outcome in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin Canc Res. 2019;25:1766–1773. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chung J.S., Wang Y., Henderson J., Singhal U., Qiao Y., Zaslavsky A.B. Circulating Tumor Cell-Based Molecular Classifier for Predicting Resistance to Abiraterone and Enzalutamide in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Neoplasia. 2019;21:802–809. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Isaacsson Velho P., Fu W., Wang H., Mirkheshti N., Qazi F., Lima F.A.S. Wnt-pathway Activating Mutations Are Associated with Resistance to First-line Abiraterone and Enzalutamide in Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2020;77:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Annala M., Struss W.J., Warner E.W., Beja K., Vandekerkhove G., Wong A. Treat-ment outcomes and tumor loss of heterozygosity in germline DNA repair-deficient prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;72:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Antonarakis E.S., Lu C., Luber B., Liang C., Wang H., Chen Y. Germline DNA-repair gene mutations and outcomes in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving first-line abiraterone and enzalutamide. Eur Urol. 2018;74:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Farmer H., McCabeN, Lord C.J., Tutt A.N., Johnson D.A., Richardson T.B. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bryant H.E., Schultz N., Thomas H.D., Parker K.M., Flower D., Lopez E. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–917. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kaufman B., Shapira-Frommer R., Schmutzler R.K., Audeh M.W., Friedlander M., Balmaña J. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:244–250. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mateo J., Carreira S., Sandhu S., Miranda S., Mossop H., Perez-Lopez R. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1697–1708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abida W., Campbell D., Patnaik A., Shapiro J.D., Sautois B., Vogelzang N.J. Non-BRCA DNA Damage Repair Gene Alterations and Response to the PARP Inhibitor Rucaparib in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Analysis From the Phase II TRITON2 Study. Clin Canc Res. 2020 Jun 1;26(11):2487–2496. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Marshall C.H., Sokolova A.O., McNatty A.L., Cheng H.H., Eisenberger M.A., Bryce A.H. Differential Response to Olaparib Treatment Among Men with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Harboring BRCA1 or BRCA2 Versus ATM Mutations. Eur Urol. 2019;76:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Le D.T., Durham J.N., Smith K.N., Wang H., Bartlett B.R., Aulakh L.K. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Antonarakis E.S., Shaukat F., Isaacsson Velho P., Kaur H., Shenderov E., Pardoll D.M. Clinical Features and Therapeutic Outcomes in Men with Advanced Prostate Cancer and DNA Mismatch Repair Gene Mutations. Eur Urol. 2019;75:378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eiber M., Fendler W.P., Rowe S.P., Calais J., Hofman M.S., Maurer T. Prostate-specific membrane antigen ligands for imaging and therapy. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(Suppl. 2):67s–76s. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.186767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rahbar K., SchmidtM, Heinzel A., Eppard E., Bode A., Yordanova A. Response and tolerability of a single dose of 177Lu-PSMA-617 in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a multicenter retrospective analysis. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1334–1338. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.173757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ahmadzadehfar H., Wegen S., Yordanova A., Fimmers R., Kürpig S., Eppard E. Overall survival and response pattern of castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer to multiple cycles of radioligand therapy using [(177)Lu]Lu-PSMA-617. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag. 2017;44:1448–1454. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3716-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rahbar K., Ahmadzadehfar H., Kratochwil C., Haberkorn U., Schäfers M., Essler M. German multicenter study investigating 177Lu-PSMA-617 radioligand therapy in advanced prostate cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:85–90. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.183194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Paschalis A., Sheehan B., Riisnaes R., Rodrigues D.N., Gurel B., Bertan C. Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen Heterogeneity and DNA Repair Defects in Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;76:469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Crumbaker M., Emmett L., Horvath L.G., Joshua A.M. Exceptional response to 177Lutetium prostate-specific membrane antigen in prostate cancer harboring DNA repair defects. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1200/PO.18.00237. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beltran H., Tomlins S., Aparicio A., Arora V., Rickman D., Ayala G. Aggressive variants of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Canc Res. 2014;20:2846–2850. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tan D.S., Rothermundt C., Thomas K., Bancroft E., Eeles R., Shanley S. ‘‘BRCAness’’ syndrome in ovarian cancer: a case-control study describing the clinical features and outcome of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5530–5536. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cheng H.H., Pritchard C.C., Boyd T., Nelson P.S., Montgomery B. Biallelic inactivation of BRCA2 in platinum-sensitive, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2016;69:992–995. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pomerantz M.M., Spisak S., Jia L., Cronin A.M., Csabai I., Ledet E. The association between germline BRCA2 variants and sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy among men with metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:3532–3539. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zafeiriou Z., Bianchini D., Chandler R., Rescigno P., Yuan W., Carreira S. Genomic Analysis of Three Metastatic Prostate Cancer Patients with Exceptional Responses to Carboplatin Indicating Different Types of DNA Repair Deficiency. Eur Urol. 2019;75:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Parker C., Nilsson S., Heinrich D., Helle S.I., O'Sullivan J.M., Fossa S.D. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213–223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Suominen M.I., Fagerlund K.M., Rissanen J.P., Konkol Y.M., Morko J.P., Peng Z. Radium-223 inhibits osseous prostate cancer growth by dual targeting of cancer cells and bone microenvironment in mouse models. Clin Canc Res. 2017;23:4335–4346. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nilsson S., Larsen R.H., Fossa S.D., Balteskard L., Borch K.W., Westlin J.E. First clinical experience with alpha-emitting radium-223 in the treatment of skeletal metastases. Clin Canc Res. 2005;11:4451–4459. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Isaacsson Velho P., Qazi F., Hassan S., Carducci M.A., Denmeade S.R., Markowski M.C. Efficacy of Radium-223 in Bone-metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer with and Without Homologous Repair Gene Defects. Eur Urol. 2019;76:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.van der Doelen M.J., Isaacsson Velho P., Slootbeek P.H.J., Pamidimarri Naga S., Bormann M., van Helvert S. Impact of DNA damage repair defects on response to radium-223 and overall survival in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Canc. 2020;136:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]