Abstract

The marine natural product latonduine A (1) shows F508del-cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) corrector activity in cell-based assays. Pull-down experiments, enzyme inhibition assays, and siRNA knockdown experiments suggest that the F508del-CFTR corrector activities of latonduine A and a synthetic analogue MCG315 (4) result from simultaneous inhibition of PARP3 and PARP16. A library of synthetic latonduine A analogs has been prepared in an attempt to separate the PARP3 and PARP16 inhibitory properties of latonduine A with the goal of discovering selective small-molecule PARP3 and PARP16 inhibitory cell biology tools that could confirm the proposed dual-target F508del-CFTR corrector mechanism of action. The structure activity relationship (SAR) study reported herein has resulted in the discovery of the modestly potent (IC50 3.1 μM) PARP3 selective inhibitor (±)-5-hydroxy-4-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzo[c]azepin-1-one (5) that shows 96-fold greater potency for inhibition of PARP3 compared with its inhibition of PARP16 in vitro and the potent (IC50 0.362 μM) PARP16 selective inhibitor (±)-7,8-dichloro-5-hydroxy-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzo[c]azepin-1-one (6) that shows 205-fold selectivity for PARP16 compared with PARP3 in vitro. At 1 or 10 μM, neither 5 or 6 alone showed F508del-CFTR corrector activity, but when added together at 1 or 10 μM each, the combination exhibited F508del-CFTR corrector activity identical to 1 or 10 μM latonduine A (1), respectively, supporting its novel dual PARP target mechanism of action. Latonduine A (1) showed additive in vitro corrector activity in combination with the clinically approved corrector VX809, making it a potential new partner for cystic fibrosis combination drug therapies.

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a lethal genetic disease most frequently caused by a F508del mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR), a chloride ion transport channel.1 Mutant F508del-CFTR is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) prior to being flagged for proteolytic degradation by the protein quality control machinery,2,3 thus preventing its trafficking to the plasma membrane and leading to the CF disease state. If the mutant F508del-CFTR protein reaches the plasma membrane, it is still somewhat functional as a chloride channel, and, therefore, an attractive approach to treating CF is the use of small-molecule “correctors” that rescue the trafficking of F508del-CFTR protein.4−6 Several chemical families of correctors have been discovered and some have progressed to evaluation in clinical trials,7−9 but to date no “corrector” has shown significant clinical benefit on its own. Ivacaftor is a “potentiator” that modulates the CFTR protein by increasing the open probability of the channel and allowing chloride ions to flow. It has shown clinical benefit for cystic fibrosis patients with CFTR channel gating issues such as the G551D mutation.9 Even though no single corrector alone has shown adequate clinical benefit, combinations of the first-generation correctors lumacaftor (VX809)7 and tezacaftor (VX-661)8 with the potentiator ivacaftor have been approved for clinical use under the trade names Orkambi (lumacaftor and ivacaftor) and Symdeko (tezacaftor and ivavaftor).9 To further enhance the effectiveness of these combination therapies, Vertex subsequently added the next-generation corrector elexacaftor (VX-445), which has a different mechanism of action than tezacaftor (VX-661), as a third component to give the triple drug combination elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor marketed as Trikafta (Kaftrio in U.K.).9 This triple drug combination featuring correctors with different mechanisms of action showed a significant increase in clinical benefit compared with Symdeko. To realize the full promise of the corrector approach to treating CF, there is still a need for additional potent and efficacious correctors belonging to new chemical scaffolds with unexploited protein targets that could be used as single agents or more likely in combination with other CFTR correctors and/or potentiators.7−9

We have previously reported the use of a phenotypic assay that measures the rescue of F508del-CFTR trafficking in baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells to screen a library of marine invertebrate crude extracts as part of a Forward Chemical Genetics program aimed at finding marine natural product trafficking correctors and identifying their molecular targets.10 This screen identified the novel sponge alkaloids latonduines A (1) and B (2) [2 was isolated as the methyl and ethyl ester artifacts 3a and 3b]11 as a new chemical family of correctors of F508del-CFTR trafficking with low nanomolar EC50 values in the screening assay. A biotinylated probe and a photoaffinity-click chemistry probe were used in pull-down experiments to show that adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribose polymerase (PARP) isoforms 1–5 were potential cellular protein targets of 1. Measurement of 1’s ability to inhibit the pure PARP isoforms 1, 2, 3, 4, 5a, and 5b in vitro demonstrated a preferential potency for PARP3 over the other isoforms of the family that were tested. siRNA knockdown of PARP3 reduced the amount of 1 that was required to produce a corrector effect, supporting the conclusion that 1 had an unprecedented corrector mechanism of action involving inhibition of PARP3.10

PARPs are a group of 17 enzymes that catalyze the attachment of ADP-ribose to a protein through the loss of nicotinamide from NAD+.12,13 PARPs 1–6 catalyze the attachment of polymeric chains of ADP-ribose of various lengths to different substrates within the cell, while all other members of the PARP family (PARPs 7–17) are either presumed or proven to attach ADP-ribose units one at a time. The PARP enzyme family has been linked to many important physiological roles in eukaryotic cells, including DNA repair, cell division, protein homeostasis, oxidative stress, and viral infection.14−17 Inhibitor development has focused primarily on PARPs 1 and 2, which are involved in the repair of single-strand breaks in DNA, recruiting DNA polymerase-β and DNA ligase-III, and in DNA base excision repair.18 These functions make PARPs 1 and 2 essential enzymes for the repair of DNA damage and the lack of PARP activity in cells was shown to cause increased sensitivity to ionizing radiation and alkylating reagents. Consequently, PARPs 1 and 2 are attractive drug targets and several PARP1/2 inhibitors including rucaparib,19 olaparib,20 and nilaparib21 have been approved for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

A follow-up structure activity relationship (SAR) study of the latonduine A CFTR corrector pharmacophore by our groups identified a more potent synthetic analogue MCG315 (4) and revealed that 1 and 4 were in vitro inhibitors of both PARP3 and PARP16.22 Pull-down studies with recombinant PARP16 showed that biotinylated latonduine A binds PARP16 directly and that this binding can be competed away by increasing amounts of latonduine A (1) or MCG315 (4). Molecular modeling indicated that 1 and 4 bind to the nicotinamide binding pockets on PARPs 3 and 16. Furthermore, it was shown using siRNA knockdowns of PARP3 and PARP16 that inhibition of both PARP isoforms resulted in a decrease in the concentration necessary for the F508del-CFTR trafficking corrector activity of 4.22 It was also found that 1 modulates the level of ribosylation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) activator inositol-requiring enzyme (IRE-1) and regulates its activity via inhibition of PARP16.

PARP16 is an ER membrane-associated protein, with an N-terminal cytosolic PARP catalytic domain, a hydrophobic transmembrane domain, and a C-terminal ER-luminal domain.23 PARP16 transduces ER stress from the C-terminal ER domain to the cytosolic domain and as such regulates the important protein kinases IRE-1-α and PERK through ADP-ribosylation, ultimately helping to regulate the unfolded protein response (UPR). Therefore, PARP16 plays an important role in cellular protein folding regulation and homeostasis.24 Given their role in F508del-CFTR trafficking as described above and in other important cellular processes, selective and potent inhibitors of PARP3 and PARP16 would be useful chemical biology tools and drug leads.25−29

We hypothesized that it would be possible by SAR modification

of

latonduine A (1) and MCG315 (4) to separate

the dual PARP3 and PARP16 inhibitory activities of the natural product

and MCG315 scaffolds to give selective PARP3 and PARP16 inhibitory

analogs. These selective inhibitors could then be used as chemical

biology tools to support our hypothesis that simultaneous small-molecule

inhibition of both PARP3 and PARP16 is required to generate the F508del-CFTR

correction phenotype. Herein, we describe the synthesis of analogues

of the previously identified F508del-CFTR trafficking correctors 1 and 4 that has resulted in the discovery of

the selective PARP3 inhibitor 5 and the selective PARP16

inhibitor 6 and their use to examine the requirement

for simultaneous inhibition of both PARP3 and PARP16 to produce functional in vitro F508del-CFTR correction.

Results and Discussion

Previous structure activity relationship studies of the latonduine pharmacophore leading to corrector 4 demonstrated that a phenyl ring was an effective bioisosteric replacement for the dibromopyrrole substructure in 1. These synthetic studies also revealed that the aminopyrimidine fragment in 1 was not required for strong corrector activity.22 Therefore, our current work focused on simple modifications of the 2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzo[c]azepin-1-one (7) core found in 4 constructed through Schmidt rearrangements30,31 and photochemical methodologies developed in the Suau32 and Mariano33 labs. These approaches were selected due to their facile entry into the desired core structure with multiple amendments from commercially available starting materials in a single or small number of synthetic steps.

We first turned our attention to the benzene ring fragment

of the

benzo[c]azepinone core, employing Schmidt rearrangement

conditions on a small number of commercially available substituted

3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (I)

starting materials, as shown in Scheme 1 and Table 1. If the rearrangement is carried out in concentrated HCl

as the solvent, the benzoazepinones II and III and the tetrazoles IV can be formed (Scheme 1 and Table 1).

Scheme 1. General Reaction Conditions and Products Formed via the Schmidt Rearrangement.

Table 1. Compounds Generated by the Schmidt Rearrangement together with Yields.

| R1, R2, R3 | II | III | IV |

|---|---|---|---|

| H, H, H | 7: 32% | 8: 16% | 9: 22% |

| H, NH2, H | 10: 51% | 11: 23% | |

| OMe, OMe, H | 12: 35% | 13: 15% | 14: 21% |

| F, H, H | 15: 33% | 16: 19% | 17: 14% |

| H, H, OH | 18: 36% | 19: 22% |

Next, we moved to explore the methodology that could expand or elaborate amendments of the azepinone core found in 1 and 4. Literature reports detail the use of a light-activated phthalimide ring expansion reaction to form substituted benzo[c]azepinediones.32,33 This reaction type involves the singlet excited state of a phthalimide with a tethered ethyl trimethyl silane V (Scheme 2A) or an unsubstituted phthalimide VIII with an alkene (Scheme 2B) to form an azetidine (VI or IX, respectively). The azetidine then undergoes transannular ring expansion to form a benzazepine-1,5-dione (VII or X), which could be further transformed.

Scheme 2. Light-Activated Phthalimide Ring Expansion Reactions.

Using methodology originally reported from the Mariano lab,33 phthalimides 20 and 23 were converted to the benzoazepinediones 21 and 24 (Scheme 3), which were then reduced to the alcohols 22 and 25 with NaBH4 (Scheme 3). Due to poor overall yields of this reaction route and difficulty in generating a diverse set of scaffolds containing the proper substituents for light-activated azetidine formation, we abandoned the Marino methodology for the second reaction pathway involving a free substituted alkene derivative.

Scheme 3. Photochemical Reactions of Phthalimides with Tethered Ethyl Trimethyl Silane Substituents, Followed by NaBH4 Reduction.

Using the methodology developed in the Suau

lab,32 we were able to produce the benzoazepinediones 26, 27, 29, and 30 in

low but

consistent yields from various vinyl aryl derivatives (Scheme 4 and Table 2). The ketones in 26, 27, 29, and 30 were reduced with

NaBH4, to generate the corresponding alcohols 5, 28, 6, and 31 as racemic

mixtures (Table 2).

The expected cis configuration of 6 was confirmed by

single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis (Supporting Information) and the cis configurations of 5, 28, and 31 were assigned by comparing their J4,5 values and 13C chemical shifts

for C-3, C-4, and C-5 to those measured for 6.

Scheme 4. Photochemical Reactions of Phthalimides with Alkenes Followed by NaBH4 Reduction.

Table 2. Compounds Synthesized by Photochemical Reactions of Phthalimides and Alkenes.

| R1 | R2 | XII | XIII |

|---|---|---|---|

| phenyl | H | 26: 22% | 5: 89% |

| 2-pyridyl | H | 27: 5% | 28: 89% |

| 2-pyridyl | Cl | 29: 2% | 6: 54% |

| 3,4-dimethoxy phenyl | H | 30: 1% | 31: 75% |

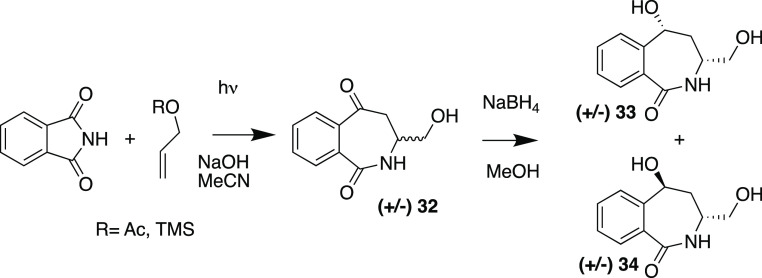

We also employed the protected allylic alcohols trimethylsilyl (TMS)-allyl ether and allyl acetate as reaction partners for photocyclization with phthalimide to provide 32 (Scheme 5). This reaction generated the opposite substitution pattern to the C-5 substitution seen for 26, 27, 29, and 30 (Table 2), instead installing a hydroxy methylene substituent preferentially at C-3 (Scheme 5). Reduction of 32 with NaBH4 gave the cis-33 and trans-34 diastereomers.

Scheme 5. Phthalimide and Protected Allylic Alcohol Photocyclization.

Latonduine A (1) and each of the synthetic analogues described above were tested for their ability to inhibit PARP1, PARP3, and PARP16 in vitro at 10 μM to evaluate their relative abilities to inhibit PARP3 and PARP16 that had been identified by siRNA knockdown experiments to be the likely protein targets responsible for the F508del-CFTR corrector activities of latonduine A (1) and MCG315 (4). The results shown in Table 3 give the percent enzyme inhibition (complete inhibition = 100%) relative to no inhibitor added (0%). Several of the compounds, including 7, 12, 17, 26, and 30, failed to inhibit any of the three test PARP isoforms tested by more than 26% and compounds 10 and 32 inhibited all three PARP isoforms by more than 50%. Another group including 9 and 25 showed >70% inhibition of both PARP3 and PARP16, but no inhibition of PARP1, similar to the inhibition pattern exhibited by latonduine A (1). Only compound 19 showed >30% inhibition of PARP1 and no inhibition of PARP3 or PARP16. These data demonstrate that modification of the core of 4 can generate analogues with different relative potencies for the various PARP family members.

Table 3. Inhibition of PARP1, PARP3, and PARP16 with Compounds at 10 μMa.

| PARP1 |

PARP3 |

PARP16 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | mean | SD (±) | N | mean | SD (±) | N | mean | SD (±) | N |

| 1 | 1 | 2.6 | 5 | 96 | 1.9 | 5 | 95 | 3.3 | 5 |

| 5 | 3 | 1.4 | 5 | 91 | 2.7 | 5 | 0 | 1.2 | 5 |

| 6 | 0 | 2.4 | 5 | 0 | 3.6 | 5 | 100 | 2.1 | 5 |

| 7 | 0 | 1.8 | 5 | 0 | 3.0 | 5 | 0 | 0.9 | 5 |

| 8 | 2 | 3.4 | 5 | 24 | 2.6 | 5 | 95 | 1.5 | 5 |

| 9 | 0 | 0.7 | 5 | 82 | 1.8 | 5 | 71 | 1.3 | 5 |

| 10 | 56 | 2.2 | 5 | 73 | 3.0 | 5 | 67 | 1.8 | 5 |

| 11 | 31 | 1.1 | 5 | 0 | 4.2 | 5 | 53 | 1.6 | 5 |

| 12 | 0 | 2.3 | 5 | 26 | 1.9 | 5 | 0 | 2.7 | 5 |

| 13 | 54 | 3.1 | 5 | 65 | 1.5 | 5 | 38 | 2.9 | 5 |

| 14 | 60 | 1.7 | 5 | 45 | 1.0 | 5 | 83 | 2.5 | 5 |

| 15 | 15 | 1.3 | 5 | 63 | 2.1 | 5 | 74 | 1.6 | 5 |

| 16 | 0 | 2.5 | 5 | 0 | 1.7 | 5 | 93.5 | 1.3 | 5 |

| 17 | 10 | 0.9 | 5 | 0 | 2.4 | 5 | 0 | 1.8 | 5 |

| 18 | 43 | 3.1 | 5 | 20 | 3.0 | 5 | 0 | 1.4 | 5 |

| 19 | 32 | 2.7 | 5 | 0 | 1.1 | 5 | 0 | 2.3 | 5 |

| 22 | 0 | 1.3 | 5 | 69 | 1.6 | 5 | 92 | 3.2 | 5 |

| 24 | 0 | 0.9 | 5 | 85 | 2.6 | 5 | 0 | 2.1 | 5 |

| 25 | 0 | 1.8 | 5 | 96 | 2.7 | 5 | 95 | 2.6 | 5 |

| 26 | 5 | 2.2 | 5 | 18 | 0.8 | 5 | 25 | 1.5 | 5 |

| 27 | 0 | 1.6 | 5 | 49 | 2.1 | 5 | 98 | 2.0 | 5 |

| 28 | 0 | 1.4 | 5 | 26 | 1.6 | 5 | 35 | 1.2 | 5 |

| 29 | 0 | 1.9 | 5 | 33 | 2.5 | 5 | 96 | 2.3 | 5 |

| 30 | 8 | 1.1 | 5 | 0 | 0.7 | 5 | 0 | 0.9 | 5 |

| 31 | 87 | 3.0 | 5 | 25 | 2.1 | 5 | 92 | 1.4 | 5 |

| 32 | 56 | 1.6 | 5 | 73 | 1.1 | 5 | 82 | 3.3 | 5 |

| 33 | 0 | 1.3 | 5 | 51 | 1.1 | 5 | 95 | 2.4 | 5 |

| 34 | 0 | 2.4 | 5 | 0 | 1.7 | 5 | 95 | 1.5 | 5 |

100 equals complete inhibition and zero (0) equals no inhibition.

The two analogs 5 and 6 are of particular interest as PARP inhibitors. Compound 5 showed good selectivity for inhibition of PARP3 (≈91% inhibition) relative to inhibition of PARP1 (≈3% inhibition) and PARP16 (0% inhibition) in the preliminary 10 μM screen. Prompted by this encouraging result, we measured dose response curves (Figure 1B) and IC50 values (Table 4) for the inhibition of all three PARP isoforms by 5. The IC50 data shows that 5 and latonduine A (1) have very similar potencies for inhibition of PARP1 (IC50: 1 24.3 μM; 5 20.1 μM) and PARP3 (IC50: 1 3.4 μM; 5 3.1 μM), but 5 is much less potent against PARP16 (IC50: 1 0.427 μM; 5 296.3 μM). Latonduine A (1) is ≈8-fold more potent against PARP16 than against PARP3, whereas 5 is 96-fold more potent against PARP3 than against PARP16. This represents a dramatic 768-fold increase in relative PARP3/PARP16 IC50 potency of 5 compared with latonduine A (1). Table 3 and Figure 1B illustrate that at 10 μM, compound 5 is a selective inhibitor of PARP3 relative to PARP16 and Table 5 shows that at the same concentration it does not significantly inhibit PARP2, PARP4, PARP5, TANKYRASE1, or TANKYRASE 2.

Figure 1.

Dose response curves for inhibition of PARP isoforms 1, 3, and 16 by latonduine A (1), 5, and 6 using a compound concentration gradient between 1 nM and 1 mM. (A) Latonduine A (1); (B) compound 5; and (C) compound 6. Data presented here as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 5).

Table 4. IC50s for Inhibitions of PARP1, PARP3, and PARP16 by Latonduine A (1), 5, and 6.

| compound | PARP1 (μM) | PARP3 (μM) | PARP16 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24.3 | 3.4 | 0.427 |

| 5 | 20.1 | 3.1 | 296.3 |

| 6 | 17.8 | 74.1 | 0.362 |

Table 5. Inhibition of a Panel of PARP Isoforms and Tankyrases by Latonduine A (1), 5, and 6 at 10 μMa.

| control |

latonduine A (1) |

5 |

6 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PARP | mean | SD (±) | N | mean | SD (±) | N | mean | SD (±) | N | mean | SD (±) | N |

| PARP1 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 5 | 31.1 | 4.7 | 5 | 27.3 | 2.9 | 5 | 18.7 | 1.1 | 5 |

| PARP2 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 5 | 21.6 | 2.1 | 5 | 14.7 | 1.1 | 5 | 10.3 | 2.0 | 5 |

| PARP3 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 5 | 83.7 | 1.4 | 5 | 95.6 | 2.4 | 5 | 25.8 | 1.2 | 5 |

| PARP4 | 0.2 | 2.1 | 5 | 18.3 | 1.5 | 5 | 16.5 | 1.6 | 5 | 11.5 | 0.9 | 5 |

| PARP5 | 0 | 3.3 | 5 | 9.9 | 0.4 | 5 | 16.4 | 1.9 | 5 | 8.9 | 1.5 | 5 |

| TAN1 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 5 | 11.7 | 2.2 | 5 | 4.7 | 2.3 | 5 | 11.1 | 1.4 | 5 |

| TAN2 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 5 | 10.1 | 1.5 | 5 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 5 | 4.8 | 0.6 | 5 |

0 equals no inhibition, 100 equals total inhibition.

In contrast, compound 6 showed strong inhibition of PARP16 but minimal inhibition of PARP1 and PARP3 in the preliminary 10 μM screen (Table 3). Therefore, we also measured dose response curves and IC50s for its inhibition of PARP1, PARP3, and PARP16. Figure 1C and Table 4 show that latonduine A (1) and 6 have potent and similar IC50 values for inhibition of PARP16 (IC50: 1 0.427 μM; 6 0.362 μM) and Figure 1C shows that 6 has strongly attenuated activity against PARP3 (IC50: 6 74.1 μM) resulting in 205-fold greater IC50 potency for PARP16 compared with PARP3. Figure 1C confirms that at 10 μM, 6 inhibits PARP16 almost completely but does not significantly inhibit PARP3 and Table 5 shows that it does not significantly inhibit PARP1, PARP2, PARP4, PARP5 TANKYRASE1, or TANKYRASE 2.

The data in Table 3 illustrates that through selective amendments on the core structure of 7, selective in vitro PARP3 and PARP16 inhibition can be found, as exhibited by 5 and 6. At 10 μM, the unsubstituted core 7 shows zero inhibition of PARP1, PARP3, or PARP16. Addition of a C-5 hydroxyl to give 22 generates significant PARP3 (69%) and PARP16 (92%) inhibition, without much selectivity. Compound 26 with C-5 ketone and C-4 phenyl substituents is a very weak inhibitor of both PARP3 and PARP16, but once the C-4 ketone in 26 is reduced to an alcohol, the PARP3 inhibition selectivity of 5 emerges. Chlorination at C-7 and C-8 of the benzene ring and oxidation of C-4 to a ketone convert the core 7 into a reasonably selective PARP3 inhibitor 24. Reduction of the C-4 ketone in 24 to an alcohol gives 25, which shows strong but not selective inhibition of both PARP3 and PARP16 and no inhibition of PARP1, much like latonduine A (1). Adding a pyrid-2-yl substituent to C-4 of 24 gives the ketone 29 that is a modest inhibitor of PARP3 and a strong inhibitor of PARP16, but reduction of the ketone in 29 produces the potent and highly selective PARP16 inhibitor 6. In both 5 and 6, the C-4 hydroxyl and C-5 aryl substituents are essential components of the selective PARP3 and PARP16 inhibitory pharmacophores.

With selective PARP3 and PARP16 inhibitors 5 and 6 in hand, we returned to the question of the mechanism of action proposed for the corrector activity of latonduine A (1). siRNA knockdown experiments targeting PARP3 and PARP16 suggested that simultaneous inhibition of both enzymes by latonduine A (1) and MCG315 (4) was required for corrector activity,10,22 but this had not been confirmed with small-molecule chemical biology probes or simultaneous siRNA knockdown experiments for latonduine A (1). The data for latonduine A (1), 5, and 6 in Table 3 and in Figure 1A–C reveals that at 10 μM latonduine A (1) inhibits both PARP3 and PARP16 by more than 95%, whereas at this concentration 5 only significantly inhibits PARP3 and 6 only significantly inhibits PARP16. Figure 2A shows the F508del-CFTR corrector activity in the high-throughput screening (HTS) cell-based assay upon treatment with (i) 10 μM latonduine A (1), (ii) 10 μM compound 5, (iii) 10 μM compound 6, (iv) 10 μM of both compounds 5 and 6, and (v) VX809 at 1 μM as a positive control.34 The results show that neither compound 5 or 6 alone gives F508del-CFTR correction but that a 1:1 combination of the two selective PARP inhibitors 5 and 6 generates F508del-CFTR trafficking correction virtually identical to latonduine A (1) alone in the HTS assay.

Figure 2.

Ability of compounds 5 and 6 when utilized in combination to correct F508del-CFTR. Panels (A) and (B) show HTS assay demonstrating changes in F508del-CFTR surface expression in the BHK cells after 24 h treatment with compounds 1, 5, and 6; the results and panel (C) show the FLIPR membrane potential (FMP) assay that measures CFTR channel functionality by monitoring membrane depolarization induced by forskolin + genistein (GST) when the cells are pretreated for 24 h. Panel (A), latonduine A (1), and compounds 5 and 6 are at 10 μM, while VX809 is at 1 μM. Panel (B), latonduine A (1) and compounds 5 and 6, and VX809 are all at 1 μM and CFTR172inh is used at 10 μM. Panel (C), latonduine A (1) and compounds 5 and 6, and VX809 are all at 1 μM and CFTR172inh is used at 10 μM. All data presented here as mean ± SEM (n = 5).

Figure 2B shows the results of a second HTS assay using all of the compounds 1, 5, 6, and VX809 at 1 μM, which is close to the IC50 values for inhibition of PARP3 by 1 and 5 and PARP16 by 1 and 6. At this concentration, once again neither 5 or 6 alone shows corrector activity, but when added together they produce corrector activity identical to latonduine A (1). The dose response data shows that at 1 μM latonduine A (1) inhibits PARP3 by 37% and PARP16 by 79%, whereas 5 inhibits PARP3 by 39% and 6 inhibits PARP16 by 81%. Therefore, the combination of 5 and 6 at 1 μM should give essentially identical inhibition of PARP3 and PARP16 as latonduine A (1) at 1 μM, consistent with the observed identical corrector activity. Figure 2B also shows that there is an additive corrector effect when latonduine A (1) and VX809 are added at 1 μM each, and an identical additive corrector effect is observed when 5, 6, and VX809 are combined each at 1 μM. VX809 is a chaperone whose mechanism of action involves direct binding to F508Del-CFTR.35 The additive in vitro effect of 1 or (5 + 6) with VX809 shown in Figure 2B is the expected outcome of treatment with combinations of correctors that have different mechanisms of action.9,34 The HTS assay measures surface CFTR protein, but it does not measure chloride channel activity. CFTR172inh is an inhibitor of chloride channel functionality.36Figure 2B shows that CFTR172inh has no impact on the correction of F508del-CFTR protein trafficking elicited by 1, 5, 6, and VX809 alone or by combinations of these compounds as measured in the HTS assay.

We used a FLIPR membrane potential (FMP) assay to measure functional correction of F508del-CFTR trafficking in the BHK cells expressing F508del-CFTR (Figure 2C).37 The cells were preloaded with a voltage-sensitive FLIPR fluorescent dye, which enters the plasma membrane of the cell and is quenched by the addition of a proprietary quencher to the medium. Activation of CFTR by forskolin depolarizes the plasma membrane and the dye moves via the chloride channel to the inner leaflet of the membrane, which relieves the quenching and increases the fluorescence, providing a measure of the CFTR function. Figure 2C shows that at 1 μM (i) latonduine A (1) generates functional CFTR correction, (ii) neither compound 5 and 6 alone gives functional correction, (iii) a combination of 5 and 6 gives functional correction identical to latonduine A (1), and (iv) latonduine A (1) plus VX809, or a combination of 5, 6, and VX809, both give additive functional correction. The CFTR inhibitor CFTR172inh is a channel blocker36 and does not have any effect on the trafficking of CFTR alone, as shown in Figure 2B. However, as shown in Figure 2C, it does block the CFTR functional correction resulting from treatment with (i) latonduine A (1) plus VX809, (ii) the combination of 5 and 6, or (iii) the combination of 5, 6, and VX809. This demonstrates that latonduine A (1) or a combination of 5 and 6 causes F508del-CFTR trafficking that is functional (as CFTR172inh blocks the function) and that both treatments are at least additive with VX809.

Conclusions

Evaluation of a small library of synthetic analogs of the marine natural product F508del-CFTR corrector latonduine A (1) has supported our hypothesis that it is possible by chemical modification of the natural product scaffold to separate its PARP3 and PARP16 inhibition activities to give enzyme-selective inhibitors. Compound 5 is modestly potent, but it shows approximately two orders of magnitude (96-fold) greater potency for inhibition of PARP3 (IC50 3.1 μM) compared with its inhibition of PARP16 (IC50 296.3 μM). This is a dramatic 768-fold increase in relative PARP3/PARP16 potency compared with latonduine A (1), completely reversing the 8-fold preference for PARP16 versus PARP3 exhibited by 1. Compound 6 is a potent (IC50 0.362 μM) PARP16 inhibitor that shows 205-fold selectivity for PARP16 compared with PARP3 (IC50 74.1 μM). At 10 μM, compounds 5 and 6 show essentially complete and selective inhibition of PARP3 and PARP16, respectively, but they do not show appreciable inhibition of PARP isoforms 1, 2, 4, 5, or TANKYRASES1 and 2, indicating broader selectivity.

The inhibitors 5 and 6 have been used at 1 and 10 μM to test our hypothesis that simultaneous inhibition of PARP3 and PARP16 is responsible for the observed F508del-CFTR trafficking corrector activity of the natural product latonduine A (1).10,22 HTS and FMP cell-based assays showed that neither 5 or 6 alone at either 1 or 10 μM elicited F508del-CFTR corrector activity, but that simultaneous treatment of the cells with combinations of 5 and 6 at both 1 and 10 μM each produced the same functional corrector effect generated by the treatment with 1 or 10 μM of latonduine A (1), respectively. These experiments support our hypothesis that latonduine A’s F508del-CFTR trafficking corrector activity involves a dual-target simultaneous inhibition of PARP3 and PARP16 and, furthermore, they show that this can be accomplished by administering a single dual-target inhibitor 1 or a combination of two selective single-target inhibitors 5 and 6. It is important to note that a phenotypic cell-based assay38 and the fortuitous dual-target activity of the natural product latonduine A (1) were essential for the discovery of this new dual-target PARP-mediated F508del-CFTR trafficking corrector mechanism of action.10,22

PARP16 is an enzyme of great interest for understanding several human disease states and consequently as a promising molecular target for developing drugs to treat these disease states.12−21 The work described herein has resulted in the discovery of a highly potent and PARP16 selective inhibitor (±)-7,8-dichloro-5-hydroxy-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzo[c]azepin-1-one (6) that is active in cells. We are not aware of potent and selective PARP16 inhibitors reported in the literature,25,26 so 6 should have utility as a chemical biology tool for the study of various PARP16-mediated biological processes in addition to F508del-CFTR trafficking correction.

The dual PARP3/PARP16 inhibition F508del-CFTR corrector mechanism of action of latonduine A (1) is unprecedented among known F508del-CFTR correctors.9,34 Approval of Trikafta for clinical treatment of CF has demonstrated that combinations of F508del-CFTR correctors with different mechanisms of action provide meaningful clinical benefit to patients.9,34 The additive in vitro corrector activity observed in this study with combinations of VX809 and either latonduine A (1) alone, or a one to one mixture of 5 and 6, suggests that dual PARP3/PARP16 inhibition, with members of the latonduine family, for example, should be considered as a promising addition to combination chemotherapies used to treat CF.

Experimental section

Experimental procedures for syntheses of analogs 5, 6, and 7. Details of the syntheses of all other analogs are in the Supporting Information.

General Experimental Procedures

All nonaqueous reactions were carried out in oven-dried Pyrex glassware under an Ar atmosphere unless otherwise noted. Air- and moisture-sensitive reagents were manipulated using airtight dry syringes. Anhydrous solvents were all obtained from commercial sources and all reagents were obtained from commercial sources without further purification. All 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 600 and 150 MHz, respectively, as indicated and referenced to the internal residual solvent peak denoted in the experimental description. Flash chromatography was performed using silica gel (230–400 mesh) with the solvent system indicated. All UV reactions were performed in a photoreactor with a water-cooled Pyrex filtered 450 W medium pressure mercury lamp. Merck type 5554 silica gel plates and Whatman MKC18F plates were used for analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) purifications were performed on a Waters 600E system controller liquid chromatograph attached to a Waters 996 photodiode array detector. All solvents used for HPLC were Fisher HPLC grade.

General Procedure for Schmidt Reaction

A vigorously stirring flask containing tetralone (0.5 g, 1 equiv) in concentrated HCl (0.3 M) was cooled to 0 °C. To this mixture was added in several small aliquots NaN3 (2 equiv) over 5 min. The mixture was left to stir open to air for 2 h at 0 °C and then allowed to slowly warm to room temp and stir for another 2 h. The reaction mixture was then poured over ice and treated with 2 mL of a 10% solution of ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN). Once the bubbling had ceased, the reaction mixture was neutralized with a saturated K2CO3 solution and the ice was allowed to melt. The reaction mixture was then extracted with (3 × ∼10 mL) EtOAc; the organic layers were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated to give crude products. Purification of the three possible products, namely, the tetrazole, and two regio-isomeric azepines, was accomplished using flash silica gel chromatography as described.

Preparation of 2,3,4,5-Tetrahydro-1H-benzo[c]azepin-1-one (7), 1,3,4,5-Tetrahydro-2H-benzo[b]azepin-2-one (8), and 6,7-Dihydro-5H-benzo[c]tetrazolo[1,5-a]azepine (9)

Starting with 3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (0.5 g, 3.4 mmol, 1 equiv), using the general procedure for the Schmidt reaction above, provides a crude mixture of the desired products. Purification using flash silica gel chromatography (eluting with stepwise gradient using 1:3, 1:1, 3:1, and 1:0 (EtOAc/Hex) (200 mL) (4 × 12 cm2 column)) gave the purified starting material (0.134 g), 6,7-dihydro-5H-benzo[c]tetrazolo[1,5-a]azepine (9) (0.153 g, 32.6%, BRSM), 4,5-dihydro-1H-benzo[b]azepin-2(3H)-one (8) (0.066 g, 16.4%, BRSM), and 2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzo[c]azepin-1-one (7) (0.089 g, 22.1%, BRSM).31

2,3,4,5-Tetrahydro-1H-benzo[c]azepin-1-one (7)

1H NMR (600 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.00 (bs, 1H), 7.48 (td, J = 7.4, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (t, J = 7.4, 1H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (dd, J = 7.2, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 2.89 (m, 2H), 2.72 (m, 2H), 1.86 (m, 2H); positive ion LRESIMS [M + H]+m/z 162.1 (calcd for C10H12NO, 162.1).31

4,5-Dihydro-1H-benzo[b]azepin-2(3H)-one (8)

1H NMR (600 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.57 (bs, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 2.77 (dd, J = 7.9, 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.22 (dd, J = 8.0, 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.16 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 173.8, 140.1, 135.1, 130.6, 128.2, 125.8, 122.5, 33.6, 31.1, 29.1; positive ion LRESIMS [M + H]+m/z 162.2 (calcd for C10H12NO, 162.1).31

6,7-Dihydro-5H-benzo[c]tetrazolo[1,5-a]azepine (9)

1H NMR (600 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.25 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (td, J = 7.5, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (t, J = 7.5, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 7.9, 1H), 4.70 (dd, J = 8.2, 6.3 Hz, 2H), 3.09 (dd, J = 7.9, 5.9 Hz 2H), 2.42 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 154.9, 141.6, 132.2, 131.3, 130.6, 127.9, 124.4, 50.0, 33.6, 26.7; positive ion LRESIMS [M + H]+m/z 187.0 (calcd for C10H11N4, 187.1).

Preparation of 9,10-Dimethoxy-6,7-dihydro-5H-benzo[c]tetrazolo[1,5-a]azepine (14)

Using the general procedure above for the Schmidt reaction with 6,7-dimethoxytetralone (0.5 g, 2.4 mmol). Purification of the crude reaction mixture by flash silica gel (eluting with 1:3, 1:1, 3:1, and 1:0 EtOAc/Hex, 200 mL each, 4 × 10 cm2 column) gave the purified starting material (0.164 g), 12 (0.077 g, 21.4%, BRSM), 13 (0.054 g, 15%, BRSM), and 14 (0.143 g, 35.4%, BRSM).

9,10-Dimethoxy-6,7-dihydro-5H-benzo[c]tetrazolo[1,5-a]azepine (14)

1H NMR (600 MHz, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-d6) δ 7.74 (s, 1H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 4.64 (dd, J = 7.0, 6.29 Hz, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.01 (dd, J = 6.0, 5.7, 2H), 2.24 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 153.6, 150.9, 147.3, 134.4, 114.2, 113.6, 112.0, 55.64, 55.62, 49.4, 32.4, 24.8; positive ion TOFHRESIMS [M + H]+m/z 247.1199 (calcd for C12H15N4O2, 247.1195).

General Procedure for Photochemical Reactions of Phthalimides and Free Alkenes

Following a procedure from Suau et al.,32 to a Pyrex Erlenmeyer flask containing 140 mL of ACN with 25 mL of H2O, were added phthalimide (1 g, 6.8 mmol) and NaOH (1 M, 2 mL). The reaction vessel was capped with a rubber septum, and styrene or substituted styrene derivative (2 equiv) was added and the reaction mixture was degassed using a stream of N2. The reaction was subsequently irradiated for 2 h in an ice bath, after which point the reaction was acidified using 1 M HCl. The mixture was then concentrated under reduced pressure and (∼50 mL) H2O was added. The mixture was then extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL). The organic layers were combined, washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The mixture was purified using flash silica gel chromatography, as described below.

Preparation of (±)-4-Phenyl-3,4-dihydro-1H-benzo[c]azepine-1,5(2H)-dione (26)

See above general procedure: product purified eluting with EtOAc/hexanes (1:1) to give 4-phenyl-3,4-dihydro-1H-benzo[c]azepine-1,5(2H)-dione (26) as white solid (0.370 g, 22%). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.58 (bt, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.29 (m, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.21 (dd, J = 9.0, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 3.65 (m, 1H), 3.53 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 204.9, 169.2, 138.2, 136.7, 132.5, 131.8, 129.3, 128.7, 128.3, 127.8, 127.3, 125.5, 61.2, 43.2; positive ion TOFHRESIMS [M + H]+m/z 252.120 (calcd for C16H14NO2, 252.1025).32

General Reaction Conditions for Sodium Borohydride Reduction of Azepinediones

To a stirred solution of azepinedione (1 equiv) was added NaBH4 (1.2 equiv) under an Ar atmosphere in absolute MeOH (∼2 mL). This was stirred while monitoring by TLC with another equivalent of NaBH4 added every 2 h. Once complete, consumption of the starting material had been achieved, H2O was added, and the reaction mixture was concentrated. The reaction was then partitioned between H2O (∼15 mL) and EtOAc (3 × 7 mL). The organic layers were combined, concentrated, and subjected to silica gel column chromatography as described below.

Preparation of (±)-5-Hydroxy-4-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzo[c]azepin-1-one (5)

Using the general procedure above: 26 (0.1 g, 0.396 mmol) and NaBH4 (0.018 g, 0.47 mmol) were added to a round-bottom flask in absolute MeOH. Crude reaction mixture was purified using silica gel chromatography (eluting with EtOAc/hexanes (9:1)) to give 5-hydroxy-4-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzo[c]azepin-1-one (5) as a white solid (0.089 g, 89%). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.20 (bs, 1H), 8.54 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (obs, 1H), 7.14 (bs, 3H), 6.85 (bd, J = 3.3 Hz, 2H), 5.33 (bs, 1H), 5.15 (bd, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (m, 1H), 3.13 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 3.18 (m, 1H), 2.91 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.3, 140.5, 139.2, 133.0, 130.3, 129.0, 128.3, 127.7, 127.6, 127.1, 126.5, 125.3, 70.1, 53.1, 45.2; positive ion HRESIMS [M + H]+m/z 254.1189 (calcd for C16H16NO2, 254.1181).

(±)-7,8-Dichloro-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-3,4-dihydro-1H-benzo[c]azepine-1,5(2H)-dione (29)

Using the general procedure above: substituting 2-vinyl pyridine (0.96 mL, 2 equiv) for styrene and 3,4-chlorophthalimide (1 g, 4.6 mmol) for phthalimide. Purified using flash silica gel chromatography (eluting with Hex/EtOAc (3:4), EtOAc, and 5% MeOH/EtOAc) to give 7,8-dichloro-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-3,4-dihydro-1H-benzo[c]azepine-1,5(2H)-dione (29) (0.032 g, 2.2%) as a bright yellow solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.77 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.99 (obs, 1H), 7.96 (s, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (dd, J = 7.3, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (bs, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.7, 163.6, 154.9, 142.9, 139.3, 135.8, 134.0, 133.6, 132.2, 131.3, 129.2, 119.3, 118.8, 106.8, 36.6; negative ion HRESIMS [M – H]−m/z 319.0035 (calcd for C15H9N2O2Cl2, 319.0041).

Preparation of (±)-7,8-Dichloro-5-hydroxy-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzo[c]azepin-1-one (6)

Using general procedure above: 29 (0.013 g, 0.04 mmol), NaBH4 (1.8 mg, 0.048 mmol), and absolute MeOH were added to a small glass vial. The crude product was purified using column chromatography (eluting with 5% MeOH/EtOAc) to give 7,8-dichloro-5-hydroxy-4-(pyridin-2-yl)-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzo[c]azepin-1-one (6) as a light yellow solid (7 mg, 54%). 1H NMR (600 MHz, MeOD-d4) δ 8.38 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.70 (td, J = 7.5, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (s, 1H), 7.24, (ddd, J = 7.5, 5.0, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 5.28 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (m, 1H), 3.50 (dd, J = 14.0, 11.0 Hz, 1H), 3.39 (dd, J = 14.0, 6.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, MeOD-d4) δ 170.8, 157.2, 147.6, 140.8, 135.9, 134.3, 131.7, 130.5, 129.3, 127.4, 124.3, 121.8, 69.6, 53.7, 42.9; positive ion HRESIMS [M + H]+m/z 323.0352 (calcd for C15H13N2O2Cl2, 323.0354).

HTS F508del-CFTR Correction Assay Protocol

The screen assay was undertaken as previously reported using BHK cells that stably express F508del-CFTR bearing three tandem hemagglutinin-epitope tags (3HA) in the fourth extracellular loop.5,39 BHK cells between passages 5–8 were seeded in 96-well plates (Corning half area, black-sided, clear bottom) at 20 000 cells per well and incubated with culture medium for 24 h at 37 °C. Each of the 80 wells was then treated with a different test compound (10 μM final concentration) for 24 h. The remaining 16 wells on each plate were used for controls. The compounds were dissolved in DMSO, which had no effect on trafficking when added at the same concentrations (data not shown). The cells were fixed in a paraformaldehyde solution (4%), washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and blocked with PBS containing fetal bovine serum (5%) for 1 h at 4–8 °C. The blocking solution was replaced with the primary antibody solution (15 μL) containing fetal bovine serum (FBS) (1%) and mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (Sigma, 1:150 dilution in PBS). The plates were sealed and left overnight at 4 °C. After three washes with PBS (100 μL), the cells were incubated for 1 h with secondary antibody solution (15 μL) containing FBS (1%) and antimouse IgG conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Sigma, 1:100 dilution in PBS). The cells were washed again three times with PBS (100 μL) and analyzed in a plate reader (Analyst HT96.384, Biosystems; 488 nm excitation, 510 nm emission). The mean fluorescence of the four untreated wells was used as the background signal when calculating the deviations of the 80 compound-treated wells. The compounds that consistently give signals that were three standard deviations above untreated controls (and were not intrinsically fluorescent) were considered hits.

PARP Enzymatic Assays

A selection of PARP enzymes was used in these studies: PARP1 (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY), PARP2 (Enzo Life Sciences), PARP3 (Enzo Life Sciences), PARP4 (Enzo Life Sciences), PARP-5a (BPS Bioscience; San Diego, CA), PARP-5b (BPS Bioscience), PARP-11 (BPS Bioscience), and PARP16 (the construct was a kind gift of Dr. Herwig Schuler, Karolinska Institute). The HT Universal Chemiluminescent PARP assay kit with histone-coated Strip Wells (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) was used to test PARP inhibition by latonduine as per the manufacturer’s instructions.10,22,40 PARP inhibitors PJ34 [2-(dimethylamino)-N-(6-oxo-5H-phenanthridin-2-yl)acetamide] and ABT888 (2-[(2R)-2-methylpyrrolidin-2-yl]-1H-benzimidazole-4-carboxamide) were obtained from SelleckChem (SelleckChem, Houston, TX). For testing of PARP16, a modified version of the assay was undertaken. Recombinant human full-length IRE-1 tagged with a 6× HIS tag was used as a substrate; all other PARPs tested used anchored-histone proteins provided in the kit. The manufacturer’s protocol was used except that a 1.5 mL tube was used rather than the 96-well plate provided. After the IRE-1 had incubated with the enzyme and reagents, nickel-agarose beads (10 mL) per reaction were added and incubated for 1 h. The rest of the protocol was performed on the IRE-1 bound to the beads. In the final step, the IRE-1-bound beads were transferred to a 96-well dish and were exposed to the two necessary chemiluminescent reagents for the reaction to occur.

FMP Functional F508del-CFTR Correction Assay Protocol

A voltage-sensitive assay was used to assay functional correction of F508del-CFTR in BHK expressing F508del-CFTR. The cells were preloaded with a derivative of the voltage-sensitive FLIPR fluorescent dye bis-(1,3-dibutylbarbituric acid) trimethine Oxonol ([DiBac4]) (https://www.google.com/patents/US6420183), which enters the plasma membrane of the cell and is quenched by the addition of a proprietary quencher to the medium. Activation of CFTR depolarizes the plasma membrane and the dye moves to the inner leaflet of the membrane, which relieves the quenching and increases fluorescence. The assays were performed in 96-well plates containing 25 000 cells per well in 100 μL of the medium. The cells were incubated with test compound (1 μM) for 24 h, washed with PBS, exposed to 70 μL of dye solution that also contained genistein (GST) (50 μM), and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Dye solution was prepared in low chloride buffer containing (mM) 160 sodium gluconate, 4.5 potassium chloride, 2 calcium chloride, 1 magnesium chloride, 10 mM d-glucose, and 10 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 7.4. After adding GST and mixing gently with the pipette, the 96-well plate was placed in a plate reader to read fluorescence. Forskolin (10 μM) was then added and the increase in signal was used to calculate the mean initial rate (i.e., Vmax) as a measure of CFTR function.34 The results are presented as a percentage of the VX809 response.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (R.J.A.), the Canadian Institute of Health Research (D.Y.T.), and Cystic Fibrosis Canada (D.Y.T.).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c02467.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Birault V.; Solari R.; Hanrahan J.; Thomas D. Y. Correctors of the basic trafficking of the mutant F508del-CFTR that causes cystic fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2013, 17, 353–360. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen T. J.; Loo M. A.; Pind S.; Williams D. B.; Goldberg A. L.; Riordin J. R. Multiple proteolytic systems, including the proteosome, contribute to CFTR processing. Cell 1995, 83, 129–135. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C. L.; Omura S.; Kopito R. R. “Degradation of CFTR by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cell 1995, 83, 121–127. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning G. M.; Anderson M. P.; Amara J. F.; Marshall J.; Smith A. E.; Welsh M. J. Processing of mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is temperature-sensitive. Nature 1992, 358, 761–764. 10.1038/358761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile G. W.; Robert R.; Zhang D.; Teske K. A.; Luo Y.; Hanrahan J. W.; Thomas D. Y. Correctors of protein trafficking defects identified by a novel high-throughput screening assay. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 1012–1020. 10.1002/cbic.200700027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Goor F.; Hadida S.; Grootenhuis P. D.; Burton B.; Stack J. H.; Straley K. S.; Decker C. J.; Miller M.; McCartney J.; Olsen E. R.; Wine J. J.; Frizzell R. A.; Ashlock M.; Negulescu P. A. Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 18843–18848. 10.1073/pnas.1105787108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy J. P.; Rowe S. M.; Accurso F. J.; Aitken M. L.; Amin R. S.; Ashlock M. A.; Ballmann M.; Boyle M. P.; Bronsveld I.; Campbell P. W.; De Boeck K.; Donaldson S. H.; Dorkin H. L.; Dunitz J. M.; Durie P. R.; Jain M.; Leonard A.; McCoy K. S.; Moss R. B.; Pilewski J. M.; Rosenbluth D. B.; Rubenstein R. C.; Schechter M. S.; Botfield M.; Ordonez C. L.; Spencer-Green G. T.; Vernillet L.; Wisseh S.; Yen K.; Konstan M. W. Results of a phase IIa study of VX-809, an investigational CFTR corrector Compound, in subjects with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del-CFTR mutation. Thorax 2012, 67, 12–18. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson S. H.; Pilewski J. M.; Griese M.; Cooke J.; Viswanathan L.; Tullis E.; Davies J. C.; Lekstrom-Himes J. A.; Wang L. T. Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in Subjects with Cystic Fibrosis and F508del/F508del-CFTR or F508del/G551D-CFTR. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 214–224. 10.1164/rccm.201704-0717OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Keating D.; Marigowda G.; Burr L.; Daines C.; Mall M. A.; McKone E. F.; Ramsey B. W.; Rowe S. M.; Sass L. A.; Tullis E.; McKee C.; Moskowitz S. M.; Robertson S.; Savage J.; Simard C.; Van Goor F.; Waltz D.; Xuan F.; Young T.; Taylor-Cousar J. L. VX-445–Tezacaftor–Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis and One or Two Phe508del Alleles. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1612–1620. 10.1056/NEJMoa1807120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Heijerman H. J. G. M.; McKone E. F.; Downey D. G.; Van Braeckel E.; Rowe S. M.; Tullis E.; Mall M. A.; Welter J. J.; Ramsey B. W.; McKee C. M.; Marigowda G.; Moskowitz S. M.; Waltz D.; Sosnay P. R.; Simard C.; Ahluwalia N.; Xuan F.; Zhang Y.; Taylor-Cousar J. L.; McCoy K. S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of the elexacaftor plus tezacaftor plus ivacaftor combination regimen in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del mutation: a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 1940–1948. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32597-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and; c Davies J. C.; Moskowitz S. M.; Brown C.; Horsley A.; Mall M. A.; McKone E. F.; Plant B. J.; Prais D.; Ramsey B. W.; Taylor-Cousar J. L.; Tullis E.; Uluer A.; McKee C. M.; Robertson S.; Shilling R. A.; Simard C.; Van Goor F.; Waltz D.; Xuan F.; Young T.; Rowe S. M. VX-659–Tezacaftor–Ivacaftor in patients with cystic fibrosis and one or two Phe508del alleles. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1599–1611. 10.1056/NEJMoa1807119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile G. W.; Keyzers R. A.; Teske K. A.; Robert R.; Williams D. E.; Linington R. G.; Gray C. A.; Centko R. M.; Yan Y.; Anjos S. M.; Sampson H. M.; Zhang D.; Liao J.; Hanrahan J. W.; Andersen R. J.; Thomas D. Y. Correction of F508del-CFTR Trafficking by the Sponge Alkaloid Latonduine Is Modulated by Interaction with PARP. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 1288–1299. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linington R. G.; Williams D. E.; Tahir A.; van Soest R.; Andersen R. J. Latonduines A and B, New Alkaloids Isolated from the Marine Sponge Stylissa carteri: Structure Elucidation, Synthesis, and Biogenetic Implications. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 2735–2738. 10.1021/ol034950b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loseva O.; Jemth A.-S.; Bryant H. E.; Schuler H.; Lehtio L.; Karlberg T.; Helleday T. PARP-3 is a mono-ADP-ribosylase that activates PARP-1 in the absence of DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 8054–8060. 10.1074/jbc.M109.077834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amé J.-C.; Spenlehauer C.; de Murcia G. The PARP superfamily. BioEssays 2004, 26, 882–893. 10.1002/bies.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petermann E.; Keil C.; Oei S. L. Importance of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases in the regulation of DNA-dependent processes. CMLS, Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 731–738. 10.1007/s00018-004-4504-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. J. O.; Ball S. S. R.; Bowater R. P.; Wormstone I. M. PARP-1 influences the oxidative stress response of the human lens. Redox Biol. 2016, 8, 354–362. 10.1016/j.redox.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales J. C.; Li L.; Fattah F. J.; Dong Y.; Bey E. A.; Patel M.; Gao J.; Boothman D. A. Review of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) mechanisms of action and rationale for targeting in cancer and other diseases. Crit. Rev. Eukaryotic Gene Expression 2014, 24, 15–28. 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2013006875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuny C. V.; Sullivan C. S. Virus-host interactions and the ARTD/PARP family of enzymes. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005453 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouleau M.; Patel A.; Hendzel M. J.; Kaufmann S. H.; Poirier G. G. PARP inhibition: PARP1 and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 293–301. 10.1038/nrc2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musella A. Z.; Bardhi E.; Marchetti C.; Vertechy L.; Santangelo G.; et al. Rucaparib: an emerging PARP inhibitor for treatment of ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2018, 66, 7–14. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA Approves Lynparza to Treat Advanced Ovarian Cancer; U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 2019, (Press release) 19 December 2014. Archived from the original on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Niraparib Receives FDA Fast Track Designation for the Treatment of Recurrent Platinum-Sensitive Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, or Primary Peritoneal Cancer; The European Society for Medical Onclogy (ESMO), Sept 5, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carlile G. W.; Robert R.; Matthes E.; Yang Q.; Solari R.; Hatley R.; Edge C. M.; Hanrahan J. W.; Andeersen R. J.; Thomas D. Y.; Birault V. Latonduine ananlogs restore F508del-cyctic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator trafficking through the modulation of poly-ADP ribose polymerase 3 and poly-ADP-polymerase 16 activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016, 90, 65–79. 10.1124/mol.115.102418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jwa M.; Chang P. PARP16 is a tail-anchored endoplasmic reticulum protein required for the PERK and IRE1α-mediated unfolded protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 1223–1230. 10.1038/ncb2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas S.; Chang P. New PARP targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 502–509. 10.1038/nrc3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsell A. G.; Ekblad T.; Karlberg T.; Low M.; Pinto A. F.; Treaugues L.; Moche M.; Cohen M. S.; Schuler H. Structural basis for potency and promiscuity I. poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and tankyrase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1262–1271. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Zhu C.; Song D.; Xia R.; Yu W.; Dang Y.; Fei Y.; Lu L.; Wu J. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate enhances ER stress-induced cancer cell apoptosis by directly targeting PARP16 activity. Cell Death Discovery 2017, 3, 17034 10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji M.; Wang L.; Xue N.; Lai F.; Zhang S.; Jin J.; Chen X. The development of a biotinylated NAD+-applied human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 3 (PARP3) enzymatic assay. SLAS DISCOVERY: Adv. Sci. Drug Discovery 2018, 23, 545–553. 10.1177/2472555218767843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif-Askari B.; Amrein L.; Aloyz R.; Panasci L. PARP3 inhibitors ME0328 and olaparib potentiate vinorelbine sensitization in breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 172, 23–32. 10.1007/s10549-018-4888-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtio L.; Jemth A.-S.; Collins R.; Loseva O.; Johansson A.; Markova N.; Hammarstro M.; Flores A.; Holmberg-Schiavone L.; Weigelt J.; Thomas Helleday T.; Schuler H.; Karlberg T. Structural Basis for Inhibitor Specificity in Human Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase-3. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 3108–3111. 10.1021/jm900052j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelte N. S.; Agback T.; et al. Benzocycloalkanones in the Schmidt Reaction. Acta Chem. Scand. 1964, 18, 191–194. 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.18-0191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald G. L.; Dahanukar V. H. Synthesis of 3-alkykl-8-substituted- and 4-hydroxy-8-substituted-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 H-2-benzapines. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1994, 31, 1609–1617. 10.1002/jhet.5570310656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suau R.; Sanchez-Sanchez C.; Garcia-Segura R.; Perez-Inestrosa E. Photocyclization of phthalimide anion to alkenes – a highly efficient, convergent method for [2]benzazepine synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 1903–1911. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Yoon U. C.; Mariano P. S. The synthetic potential of phthalimide SET photochemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 523–533. 10.1021/ar010004o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and; b Yoon U. C.; Oh S. W.; Lee S. M.; Cho S. J.; Gamlin J.; Mariano P. S. A Solvent Effect That Influences the Preparative Utility of N-(Silylalkyl)phthalimide and N-(Silylalkyl)maleimide Photochemistry. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 4411–4418. 10.1021/jo990087a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile G. W.; Yang Q.; Matthes E.; Liao J.; Radinovic S.; Miyamoto C.; Robert R.; Hanrahan J. W.; Thomas D. Y. A novel triple combination of pharmacological chaperones improves F508del-CFTR correction. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11404 10.1038/s41598-018-29276-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson R. P.; Dawson J. E.; Chong P. A.; Yang Z.; Millen L.; Thomas P. J.; Brouillette C. G.; Forman-Kay J. D. Direct binding of the corrector VX-809 to human CFTR NBD1: evidence of an allosteric coupling between the binding site and the NBD1:CL4 interface. Mol. Pharmacol. 2017, 92, 124–135. 10.1124/mol.117.108373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkman A. S.; Synder D.; Tratrantip L.; Thiagarajah J. R.; Anderson M. O. CFTR inhibitors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 3529–3541. 10.2174/13816128113199990321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Goor F.; Straley K. S.; Cao D.; Gonzalez J.; Hadida S.; Hazlewood A.; Joubran J.; Knapp T.; Makings L. R.; Miller M.; Neuberger T.; Olson E.; Panchenko V.; Rader J.; Singh A.; Stack J. H.; Tung R.; Grootenhuis P. D. J.; Negulescu P. Rescue of DeltaF508-CFTR trafficking and gating in human cystic fibrosis airway primary cultures by small molecules. Am. J. Physiol.: Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2006, 290, L1117–L1130. 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. E.; Andersen R. J. Biologically active marine natural products and their molecular targets discovered using a chemical genetics approach. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 617–633. 10.1039/C9NP00054B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile G. W.; Robert R.; Goepp J.; Matthes E.; Liao J.; Kus B.; Macknight S. D.; Rotin D.; Hanrahan J. W.; Thomas D. Y. Ibuprofen rescues mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator trafficking. J. Cystic Fibrosis 2015, 14, 16–25. 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinders R.; Ferry-Galow K.; Wang L.; Srivastava A. K.; Ji J.; Parchment R. E. Implementation of validated pharmacodynamic assays in multiple laboratories: challenges, successes, and limitations. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 2578–2586. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.