Abstract

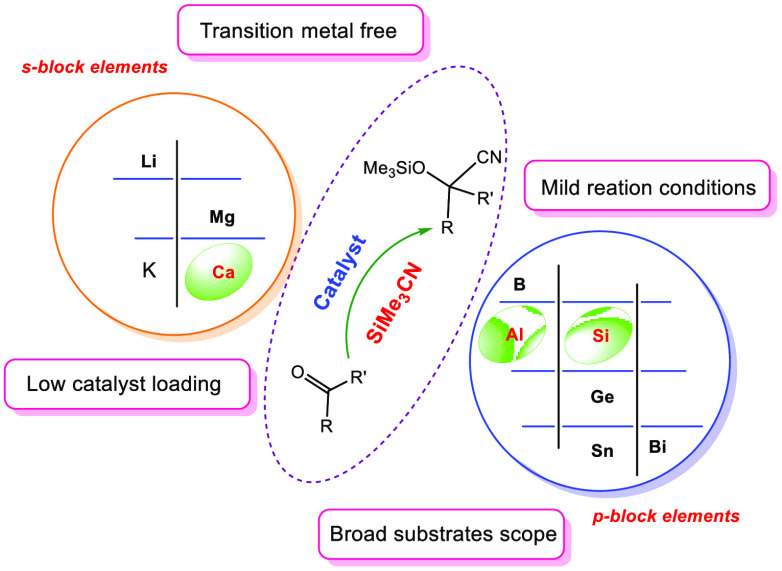

The past few decades have seen remarkable headways in the structural and reaction chemistry of compounds with heavier main-group elements. In recent years, there is an ongoing effort to derive catalytic chemistry involving main-group compounds, driven by their lower costs and higher terrestrial abundances. Here, a survey on the state-of-the-art in the development of cyanosilylation methodology by compounds with heavier main-group elements has been given. Once dominated by transition metals, the field has matured to embrace the majority of the main-group elements including aluminum, silicon, and calcium. Of particular focus will be how the mechanism of cyanosilylation involving compounds with main-group elements differs from those of transition metals.

1. Introduction

Developing earth-abundant, nontransition metal catalysts for high-value chemical transformations is at the fore of academic and industrial research. The cyanosilylation of carbonyl compounds is an important transformation to access a wide range of biologically important compounds such as β-amino alcohols, α-hydroxy acids, α-hydroxy ketones, and α-amino acids.1a Trimethylsilyl cyanide (Me3SiCN) is extensively used as a cyanide source for the cyanosilylation of unsaturated bonds because of the toxicity and difficulty of using HCN. A large number of catalysts have been reported for the addition of the Me3SiCN to carbonyls. However, the majority of these catalysts are based on transition metals or inorganic solid acids and bases.1 Because of the inherent availability, sustainability, low cost, and low toxicity of main-group elements, they engender the lowest environmental and societal impact, thereby holding a unique position in contemporary chemical synthesis. Therefore, the development of efficient homogeneous catalysts based on the main-group elements for the cyanosilylation of the carbonyl compounds with Me3SiCN is a very important subject in current research, and several efficient main-group catalysts have been developed thus far. In this Mini-Review, a periodic group-wise survey of this rapidly growing field will be detailed. It would be a mammoth task to report every single reaction; hence, only work that was published since 2010 and involved a main-group compound as a single site catalyst is considered. However, for the sake of completion of the topic, cyanosilylation with few bifunctional homogeneous catalysts have been incorporated. Apart from these, there are also few reports on catalyst free cyanosilylation of aldehydes2 or electrochemical cyanosilylation of aldehydes,3 however these works fall outside the scope of this Mini-Review. As the substrate scope is more or less same for all the catalysts, it will not be discussed, unless there are some special cases. At the end of the Mini-Review, a comparison table for the cyanosilylation of acetophenone by various main-group based catalysts has been provided.

2. Cyanosilylation with s-Block Compounds

2.1. By Alkali Metals

The understanding of the s-block compounds is still early in development, and there is increasing interest in exploring them in highly demanding cyanosilylation reactions. Group 1 complexes have been less explored because of their high reactivity and tendency to be involved in aggregation behavior. Nevertheless, they have one advantage over their adjacent neighbors in that they do not involve in Schlenk equilibrium, which is a major impediment in alkaline earth metal chemistry. As most of the main-group catalysts are synthesized from the corresponding lithium reagents, the direct use of lithium compounds as catalysts could avoid such additional transformations (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Compounds with s-Block Elements Used for Cyanosilylation of Aldehydes and Ketones.

Dipp = 2,6-iPr2C6H3, Xyl = 2,6-Me2C6H3, Ad = adamantyl.

Recently, our group reported the use of readily available organolithium compounds (1–3) as catalysts for cyanosilylation of both aldehydes and ketones with moderate to good conversion at room temperature.4 An equimolar amount of aldehydes or ketones with Me3SiCN in the presence of 0.1 mol % of lithium compounds (1–3) are able to ensure the formation of the required cyanohydrin products. The reaction time for ketones is approximately 2 h, while for aldehydes, it is only 1 h. Subsequent to our publication, the research group of Panda has reported a catalyst consisting of a N-adamantyl-iminipyrrolyl ligand supported potassium (4) for cyanosilylation of aldehydes and ketones.5 Compounds 1–4 are tolerant toward various electron-donating and electron-withdrawing functional groups. In the case of cinnamaldehyde, 1,2 addition of Me3SiCN takes place selectively over the Michael addition product at ambient reaction condition. Quantitative conversion of benzophenone to its corresponding cyanohydrin was accomplished by 1–3 in only 2 h, which is a result that is not achieved by any other main-group catalyst so far.

2.2. By Alkaline Earth Metals

The elements from group 2 have drawn attention as catalysts because of the striking similarity of their ionic radii with the trivalent lanthanides [Ca(II): 1.00, Yb(III): 1.03, Sr(II): 1.18, Sm(III): 1.15, Eu(III): 1.14)], which frequently resulted in comparable reactivities, such as (a) insertion into the polar bond and (b) σ-bond metathesis. The advantage of these two steps over the oxidative addition and reductive elimination is that they do not require the alteration of the oxidation state of the central element of the catalyst.

In 2007, the group of Jones reported a unique magnesium compound, {(ArNacnac)Mg}2 where the formal oxidation state of the magnesium atom is +1.6 In order to discover the catalytic worth of such magnesium(I) dimer, Ma and co-workers recently explored the cyanosilylation reaction of ketones with a β-diketiminate stabilized magnesium(I) compound, {(XylNacnac)Mg}2 (5) (Xyl = 2,6-Me2C6H3) under mild reaction conditions.7 To examine the role of the substituent in influencing the catalytic performance, they have replaced the xylyl moiety with more popular Mes (2,4,6-Me3C6H2) and Dipp (2,6-iPr2C6H3)] substituents; however, the catalytic activity declines from Xyl to Mes to Dipp. This implies that the catalytic activity decreases with the increase of steric bulk on the nitrogen atoms. Also, 5 is only effective for ketones with the electron donating substituents such as −OMe, −CH3, −NH2. Subsequently, Ma and co-workers used a NCN-pincer ligand-based bimetallic magnesium complex [NCN-MgBr2][Li(THF)4] (6) for cyanosilylation of aldehydes;8 however, the catalyst is relatively less effective for ketones. In fact, the authors have noted while cyanosilylation of aliphatic aldehydes (1-pentanal, 5-chloropentanal, and cyclohexylaldehydes) was over in 15 min, aromatic aldehydes with both electron-donating and -withdrawing substituents require ∼3 h for the productive conversion.

The claim that the magnesium(I) compound behaves as a single-site catalyst for hydroboration or cyanosilylation sparks a controversy as it implies that the magnesium(I) compound is regenerated after the catalyzed reactions are over. This also implies that such compounds with low-valent main-group elements can undergo reductive elimination, which was considered as a formidable task. The group of Jones demonstrated that the magnesium(I) compounds are not the bonafide catalysts for the hydroboration reaction.9 In the same line, it can also be surmised that the magnesium(I) compounds are perhaps not the true catalysts or precatalysts for the cyanosilylation, and more studies are required to know the nature of the species that is doing the catalysis.

Before the report of the Mg compounds as cyanosilylation catalysts, we have shown that a benz-amidinato calcium iodide, [PhC(NiPr)2CaI] (7) functions as a catalyst for the cyanosilylation of a variety of aldehydes and ketones.10 Compound 7 was prepared in a single step by reacting a lithiated N,N-diisopropylcarbodiimide with calcium iodide.11 Although 7 can reduce most of the aldehydes with Me3SiCN, it was found to be more effective for ketones with electron-withdrawing substituents such as −NO2, −CN, and so on. This is in contrast to 5, which shows more efficiency for ketones with electron-donating substituents. 7 can also reduce benzophenone to the corresponding cyanosilylated product in 82% yield, but the TOF is less than those of 1–3. Advantages of this catalytic system include the use of earth abundant calcium, presenting low toxicity as well as low cost, easy preparation of the catalyst, and mild conditions employed (25–35 °C).

To explore the reaction mechanism, DFT studies are performed (Scheme 2). In the first step, the Ca catalyst forms a weak donor–acceptor adduct with Me3SiCN (Int_7A), which was characterized by the changes in the IR (2067.7 cm–1; Me3SiCN: 2092 cm–1) and 29Si NMR (7.4 ppm; Me3SiCN: −11.9 ppm) spectra. No formation of Me3SiI was detected by NMR spectroscopy, which is also supported by the DFT calculations (ΔG# = 33.1 kcal/mol). In the next step, aldehydes or ketones attack the Si atom of Me3SiCN, leading to the product formation via σ-bond metathesis. The change of free energy of the reaction was calculated to be 28.1 kcal/mol, supporting why the catalysis occurs at room temperature.

Scheme 2. Mechanism for Ca-Catalyzed Cyanosilylation.

Calculations are done at the PBE/QZVP level of theory with DFT.

3. Cyanosilylation with p-Block Compounds

Examples of active catalysts based on p-block elements have lagged behind their transition metal counterparts, although some systems based on remarkably simple Lewis acids such as B, Al, Si, and Ge have recently been documented.

3.1. Cyanosilylation by Compounds with Group 13 Elements

3.1.1. Boron-Based Catalyst

In 2009, Kadam and Kim divulged the potential of tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane [B(C6F5)3] (8) for the cyanosilylation of aldehydes and ketones under neat conditions at room temperature with very low catalyst loading (0.5 mol %) in a short reaction time (10 min for acetophenone).12 Higher catalyst loading (4 mol %) and longer reaction time (1 h) were required when the reaction was performed in acetonitrile. The reaction was not very efficient in other solvents like tetrahydrofuran, chloroform, and dichloromethane.

3.1.2. Aluminum-Based Catalyst

Aluminum is the third most abundant element in the Earth’s crust. Hence, the use of well-defined aluminum species as catalysts is highly desirable. Although cyanosilylation of aldehydes and ketones have witnessed the use of aluminum as a Lewis acidic site in bifunctional or multifunctional catalysts,1b there was no report of an aluminum compound as a single-component catalyst for this transformation. It is only recently that Roesky et al. have reported LAl(III)H(OTf) (L= HC(CMeN-Dipp)2) (9) as a catalyst for the cyanosilylation of aldehydes and ketones (Scheme 3).13 The presence of the OTf group increases the Lewis acidic character, which is reflected from the NPA analysis (LAlH2: 1.41e vs 8: 1.81e). Subsequently, they have replaced the OTf group with other N, O, and S-bonded ligands and prepared 10–13;14 however, the catalytic efficiency was found to be the best for 9, implying the higher Lewis acidity of the Al is better for the catalysis.

Scheme 3. Cyanosilylation of Aldehydes and Ketones by Al-Based Compounds.

Subsequently, Nagendran tested the ability of a well-defined Al cation supported by the aminotroponate (AT) ligands [(AT)Al(DMAP)]+[OTf]− (14) as a cyanosilylation catalyst.15 Compound 14 was prepared by reacting [(AT)AlOTf] (14′) with N,N-dimethyl amino pyridine (4-DMAP), which led to the cleavage of the OTf moiety from the Al atom and 4-DMAP coordinates to the cationic Al atom with OTf as a counteranion. Smooth cyanosilylation of aldehydes and ketones takes place with 1 to 2 mol % of the catalyst loading in just 5 to 30 min at room temperature. The better catalytic performance of 14 over 9–13 can be attributed to the high NPA charge on the Al atom (2.03e) and semibulky nature of the aminotroponate ligands that allow the coordination of the catalyst to the substrate. Compound 14′ can also catalyze cyanosilylation of benzaldehyde, but with higher catalyst loading and longer reaction time, underscoring the significance of the generation of the cationic center at aluminum for achieving better catalytic activity.

The Al atom in 14 is five-coordinate. It can be assumed that a low-coordinate Al cation may act as a better catalyst because the substrate binding might be easier. Singh and co-workers prepared an electronically unsaturated three coordinated Al cation (15), which has a Lewis acidity comparable to that of B(C6F5)3 according to the Gutmann–Becket method. Compound 15 catalyzes cyanosilylation of aldehydes and ketones under mild and solvent-free conditions in a very short reaction time (5 min) with a 0.05 mol % catalyst loading (except for 4-pyridinecarboxaldehyde).16 The propensity of the adduct formation between pyridine N of 4-pyridinecarboxaldehyde and Al center can be reckoned why the cyanosilylation was not successful. However, with increasing catalyst loading to 1.5 mol % and reaction time (1 h), the corresponding cyanohydrin was afforded in 87% yield.

A general mechanism for the cyanosilylation of aldehydes and ketones by all aluminum compounds (9–15) is given in Scheme 4. In the first step, every Al catalyst forms a weak donor–acceptor adduct with Me3SiCN, thus activating the Si–C bond. In the next step, the oxygen atom of aldehyde or ketone attacks the Si center, leading to the cleavage of the Al–N bond and formation of the cyanohydrin.

Scheme 4. A General Mechanism for Cyanosilylation of Aldehydes and Ketones by Al-Based Compounds.

X = substituent/counter-anion.

The group of Zhou developed an orthogonal activation strategy with a three-component catalyst system consisting of a salen-aluminum complex (16) phosphorane and phosphine oxide for the enantioselective cyanosilylation (Scheme 5) of simple ketones and conjugated enanones with a broad scope.17 They have used phosphorane as a cocatalyst to enhance the electrophilicity on the Al center in 16. No reaction takes place in the presence of either 15 or Ph3PO at room temperature. This supports that the phosphorane does not work as a catalyst, but only as the cocatalyst. On the other hand, phosphorane was found to be more efficient than N-oxides, tertiary amine, pyridines, phosphine oxides, and tertiary phosphine. The function of Ph3PO was to secure high reactivity and enantioselectivity. In 2016, the same group has utilized a unique bifunctional cyanating reagent, Me2(CH2Cl)SiCN and catalyst 16 in the presence of a phosphorane for the synthesis of tertiary alcohols via catalytic enantioselective cyanosilylation of a chloromethyl ketone moiety (Scheme 6).18 The bifunctional reagent, Me2(CH2Cl)SiCN exhibited improved results in cyanosilylation than Me3SiCN.

Scheme 5. Orthogonal Activation of Both Chiral Catalyst 16 and Me3SiCN by Zhou’s Group (2016) Using Phosphorane and Ph3PO.

Scheme 6. One-Pot Synthesis of Tertiary Alcohol via Cyanosilylation Using Bifunctional Cyanating Reagent, Me2(CH2Cl)SiCN.

3.2. Cyanosilylation by Compounds with Group 14 Elements

3.2.1. Silicon-Based Catalyst

Among all main-group elements, silicon holds a unique position, offering the lowest environmental and societal impact as it is the second most abundant element, nontoxic, and environmentally benign. The journey of silicon compound as a cyanosilylation catalyst began in 2015 when Bergmann and Tilley showed that bis(perfluorocatecholato)-silane (17) can catalyze the cyanosilylation of p-nitrobenzaldehyde at 45 °C and the desired cyanohydrin was formed in 93% yield (Scheme 7).19 However, they did not elaborate the substrate scope for the cyanosilylation.

Scheme 7. Cyanosilylation of Aldehydes by Neutral Silicon, Germanium, and Tin Compounds.

We have reported that benz-amidinato chlorosilane, (PhC(NtBu)2SiH(CH3)Cl) (18) can catalyze cyanosilylation of aldehydes.20 Initially, we have shown that 18 reacts with Me3SiCN to form (PhC(NtBu)2SiH(CH3)CN) (19) along with the liberation of Me3SiCl, which was confirmed from the appearance of a peak at 32 ppm in the 29Si NMR spectrum. Benzaldehyde reacts with 19 to form (PhC(NtBu)2SiH(CH3)OCH(Ph)CN) (20) through insertion into the Si–CN bond. 20 reacts with Me3SiCl that leads to the desired cyanohydrin with concomitant regeneration of 18. Both 18 and 19 were structurally authenticated exhibiting penta-coordinate silicon atoms. Subsequently, we were able to apply these stoichiometric transformations in a catalytic process (Scheme 8, left). However, the efficiency of the catalyst is limited to only aldehydes. Presumably, the higher coordination around the silicon center makes it less Lewis acidic and also provides a more steric hindrance toward substrate binding, thereby preventing the ketone cyanosilylation.

Scheme 8. Above: Mechanism of Cyanosilylation Catalyzed by 18 (Left) and 21 (Right); Below: Molecular Structures of 18 (Left), 19 (Middle), and 21 (Right).

3.2.2. Germanium- and Tin-Based Catalysts

The first main-group compound that has been attributed to catalyzing the cyanosilylation of aldehydes was a cyanogermylene (21) developed by Nagendran and Siwatch.21 However, the substrate scope was limited to isobutaraldehyde, propionaldehyde, and 2-phenylpropionaldehyde. Nonetheless, they have demonstrated that 21 first reacts with aldehydes (RCHO) to form the corresponding germylene alkoxide complexes, which subsequently reacts with Me3SiCN to form the desired cyanohydrins via σ-bond metathesis along with the regeneration of 21 (Scheme 8, right). This result has spurred significant interest in the development of catalysts based on heavier main-group elements not only for cyanosilylation but also for other organic transformations.

Very recently, the groups of Khan have demonstrated the catalytic applications of N-heterocyclic germylene (22) and stannylene (23) for cyanosilylation (Scheme 7) of the aromatic aldehydes.22 In fact, 23 was a rare tin-based catalyst used for the cyanosilylation reaction. It is of note here that a tin-compound catalyzed asymmetric cyanosilylation of aldehydes was reported by Kobayashi in 1991, but it requires 30% catalyst loading, the substrate scope is limited to only aliphatic aldehydes, and it could not catalyze the formation of cyanohydrin from benzaldehyde.2323 was found to be more competent than 22 due to the higher Lewis acidity of Sn. Khan and co-workers performed DFT studies to understand the mechanism and validated it with the NMR studies of the intermediates. The mechanism is very similar to the Ca/Al-catalyzed cyanosilylation, where initially nitrile coordinates to the metal with subsequent nucleophilic attack by the carbonyl carbon. The change of free-energy barrier is 29.5 kcal/mol for 22 and 24.4 kcal/mol for 23, endorsing the better efficiency of the latter. However, 22 and 23 were unable to catalyze the cyanosilylation of ketones, and this is apparently due to the presence of the two neopentyl groups on the nitrogen atoms that shield the metal center.

3.3. Cyanosilylation by Compounds with Group 15 Elements

3.3.1. Phosphorus-Based Catalyst

Zhou and co-workers recently reported a carbonyl-stabilized N,N-diethylacetamide derived phosphorus ylide (24) as an efficient Lewis base catalyst for the cyanosilylation of aldehydes and ketones through the desilylative nucleophilic activation of TMSCN, with catalyst loading down to 0.005 mol %.24 The reaction was smooth under solvent-free conditions, although the reaction rate was slightly lower for ketones when the reaction was conducted in acetonitrile.

3.3.2. Bismuth-Based Catalyst

In 2013, Roesky and co-workers synthesized a Bi-based siloxanes with a cube cage core of Si4O8Bi4 (25), which showed a good catalytic efficiency for the cyanosilylation (Scheme 9) of aldehydes and ketones.25 They proposed that the Bi metals interact with the oxygen atom of the aldehydes and ketones first, leading to enhance the electrophilic character of the carbonyl carbon. In the second step, a nucleophilic attack from the N-donor cite of the Me3SiCN to the C=O carbon atom occurs. However, no mechanistic insight was provided.

Scheme 9. Phosphorus- and Bismuth-Based Bifunctional Catalysts for Cyanosilylation of Aldehydes and Ketones.

4. Conclusion

Main-group element containing catalysts are now more accessible thanks to spectacular developments in the synthetic methodologies. Once dominated by the structure and bonding of main-group compounds, the field has started to find application in catalysis. Cyanosilylation of aldehydes by 21 was one of the first examples of a catalytic transformation by a compound with a heavier main-group element. Since then, the field has grown to include the majority of the main-group elements within a span of five years. The catalysis based on Si, Al, and Ca is of precise interest as they are the second, third, and fifth most abundant elements, respectively in the Earth’s crust. A comparison of the catalytic performance of several main-group based catalysts for the cyanosilylation of acetophenone was tabulated (Table 1). Notably, much of the catalytic chemistry that has thus far been described for main-group compounds is quite distinct from that of known transition-metal chemistry. For example, the catalysts based on main-group elements do not involve in oxidative addition/reductive elimination but rather undergo σ-bond metathesis. This difference is due to the immutable oxidation state of main-group elements versus transition metals. The development of chiral cyanosilylation by 15 has brought us closer to the transition metal free asymmetric catalysis, and we are confident that next two decades will see more exciting progress in this field.

Table 1. A Comparison for Cyanosilylation of Acetophenone Using Catalysts 1–25.

| entry | catalyst | catalyst loading (mol %) | time | yield (%) | TOF (min–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 h | 93 | 7.75 |

| 2 | 2 | 0.1 | 2 h | 96 | 8.00 |

| 3 | 3 | 0.1 | 2 h | 98 | 8.166 |

| 4 | 4 | 3.0 | 1 h | 99 | 0.55 |

| 5 | 5 | 0.1 | 1 h | 99 | 16.5 |

| 6 | 6 | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | 7 | 3.0 | 2 h | 63 | 0.175 |

| 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 8 min | 97 | 24.25 |

| 9 | 9 | 2.0 | 6 h | 51 | 0.071 |

| 10 | 10–13 | - | - | - | - |

| 11 | 14 | 2.0 | 30 min | 95 | 1.583 |

| 12 | 15 | 0.05 | 5 min | 96 | 384 |

| 13 | 16 Co-catalyst: phosphorane | 10 | 72 h | 56 | 0.001 |

| 14 | 17,18,21–23 | - | - | - | |

| 18 | 24 | 0.2 | 5 h | 99 | 1.65 |

| 19 | 25 | 0.2 | 1.5 h | 99 | 5.5 |

Acknowledgments

S.S.S is thankful to Department of Science and Technology (DST) for Ramanujan Research Grant (SB/S2/RJN-073/2014). S.P. thanks the DST, of India for an INSPIRE Fellowship (IF160314). G.K. thanks the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), India for a research fellowship. We warmly thank our students and co-workers whose names are cited in the references, for their many intellectual and experimental contributions.

Biographies

Sanjukta Pahar obtained her B.Sc. from Calcutta University in 2013 and MSc from IIT Madras in 2015. Subsequently, she joined the research group of Dr. Sakya S. Sen, at the CSIR National Chemical Laboratory, Pune, India. She works on the donor–acceptor stabilization of compounds with low coordinate group 13 and 14 elements.

Gargi Kundu obtained her B.Sc. from Jadavpur University in 2015 and MSc from IIT Madras in 2017. Subsequently, she joined the research group of Dr. Sakya S. Sen, at the CSIR National Chemical Laboratory, Pune, India. Her research interest is the activation of small molecules by carbenes and related compounds.

Sakya S. Sen did his Ph.D. training with Professor Herbert W. Roesky at the University of Göttingen, Germany studying low-valent silicon chemistry and received his Ph.D. in 2010 with a summa kum laude grade. Postdoctoral work followed (2011-2013), working with Professor Holger Braunschweig at the University of Würzburg, Germany, on novel boron compounds, supported by a fellowship from the AvH Foundation. In 2014, he was appointed as a senior scientist at CSIR-NCL, Pune, where he is currently serving as a Principal Scientist since 2018. Dr. Sen is the recipient of CSIR-Young Scientist Award in 2017, INSA Young Scientist medal in 2018, Merck Young Scientist Award, 2019. He is a young associate of Indian Academy of Sciences (2017-2020). He has been selected as a ChemComm Emerging Investigator 2018 and Early Career Advisory Board Member of ACS Catalysis (2019-2021).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- a North M.; Usanov D. L.; Young C. Lewis Acid Catalyzed Asymmetric Cyanohydrin Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 5146–5226. 10.1021/cr800255k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Prakash G. K. S.; Vaghoo H.; Panja C.; Surampudi V.; Kultyshev R.; Mathew T.; Olah G. A. Effect of carbonates/phosphates as nucleophilic catalysts in dimethylformamide for efficient cyanosilylation of aldehydes and ketones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 3026–3030. 10.1073/pnas.0611309104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Khan N. H.; Kureshy R. I.; Abdi S. H. R.; Agrawal S.; Jasra R. V. Metal Catalyzed Asymmetric Cyanation Reactions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 593–623. 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Luo M.; Yao W.; Ma M.; Pullarkat S. A.; Xu L.; Leung P.-H. Catalyst-free and Solvent-free Cyanosilylation and Knoevenagel Condensation of Aldehydes. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 1718–1722. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.; Shen Y.; Xiao Z.; Liu C.; Yuan K.; Ding Y. The Direct Trifluoromethylsilylation and Cyanosilylation of Aldehydes via an Electrochemically Induced Intramolecular Pathway. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 2435–2438. 10.1039/C9CC08975F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisai M. K.; Das T.; Vanka K.; Sen S. S. Easily Accessible Lithium Compounds Catalyzed Mild and Facile Hydroboration and Cyanosilylation of Aldehydes and Ketones. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 6843–6846. 10.1039/C8CC02314J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harinath A.; Bhattacharjee J.; Nayek H. P.; Panda T. K. Alkali Metal Complexes as Efficient Catalysts for Hydroboration and Cyanosilylation of Carbonyl Compounds. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 12613–12622. 10.1039/C8DT02032A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S. P.; Jones C.; Stasch A. Stable Magnesium(I) Compounds with Mg–Mg Bonds. Science 2007, 318, 1754–1757. 10.1126/science.1150856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Luo M.; Li J.; Pullarkat S. A.; Ma M. Low–valent Magnesium(I)–Catalyzed Cyanosilylation of Ketones. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3042–3044. 10.1039/C8CC00826D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Yu T.; Luo M.; Xiao Q.; Yao W.; Xu L.; Ma M. Efficient and Selective Aldehyde Cyanosilylation Catalyzed by Mg-Li Bimetallic Complex. J. Organomet. Chem. 2018, 874, 83–86. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.08.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. D. L.; Matthews A. J. R.; Jones C. The Complex Reactivity of β-diketiminato Magnesium(I) Dimers towards Pinacolborane: Implications for Catalysis. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 5785–5792. 10.1039/C9DT01085H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S.; Dixit R.; Vanka K.; Sen S. S. Beyond Hydrofunctionalization: A well-Defined Calcium Compound Catalyzed Mild and Efficient Carbonyl Cyanosilylation. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 1269–1273. 10.1002/chem.201705795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S.; Swamy V. S. V. S. N.; Gonnade R. G.; Sen S. S. Benz-amidinato Stabilized a Monomeric Calcium Iodide and a Lithium Calciate(II) Cluster featuring Group 1 and Group 2 Elements. Chemistry Select 2016, 1, 1066–1071. 10.1002/slct.201600285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadam S. T.; Kim S. S. Metal and Solvent-free Cyanosilylation of Carbonyl Compounds with Tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 23, 119–123. 10.1002/aoc.1479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Zhong M.; Ma X.; De S.; Anusha C.; Parameswaran P.; Roesky H. W. An Aluminum Hydride That Functions like a Transition-Metal Catalyst. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10225–10229. 10.1002/anie.201503304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Yi; Zhong M.; De S.; Mondal T.; Koley D.; Ma X.; Zhang D.; Roesky H. W. Addition Reactions of Me3SiCN with Aldehydes Catalyzed by Aluminum Complexes Containing in their Coordination Sphere O, S, and N Ligands. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 6932–6938. 10.1002/chem.201505162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M. K.; Sinhababu S.; Mukherjee G.; Rajaraman G.; Nagendran S. A Cationic Aluminium Complex: An Efficient Mononuclear Main Group Catalyst for the Cyanosilylation of Carbonyl Compounds. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 7672–7676. 10.1039/C7DT01760J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat S.; Bhandari M.; Prashanth B.; Singh S. Three Coordinated Organoaluminum Cation for Rapid and Selective Cyanosilylation of Carbonyls under Solvent-Free Conditions. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 2407–2411. 10.1002/cctc.202000309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X.-P.; Cao Z.-Y.; Wang X.; Chen L.; Zhou F.; Zhu F.; Wang C.-H.; Zhou J. Activation of Chiral (Salen)AlCl Complex by Phosphorane for Highly Enantioselective Cyanosilylation of Ketones and Enones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 416–425. 10.1021/jacs.5b11476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X.-P.; Zhou J. Me2(CH2Cl)SiCN: Bifunctional Cyanating Reagent for the Synthesis of Tertiary Alcohols with a Chloromethyl Ketone Moiety via Ketone Cyanosilylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8730–8733. 10.1021/jacs.6b05601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman-Martin A. L.; Bergman R. G.; Tilley T. D. Lewis Acidity of Bis(perfluorocatecholato)silane: Aldehyde Hydrosilylation Catalyzed by a Neutral Silicon Compound. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5328–5331. 10.1021/jacs.5b02807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy V. S. V. S. N.; Bisai M. K.; Das T.; Sen S. S. Metal Free Mild and Selective Aldehyde Cyanosilylation by a Neutral Penta-Coordinate Silicon Compound. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 6910–6913. 10.1039/C7CC03948D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siwatch R. K.; Nagendran S. Germylene Cyanide Complex: A Reagent for the Activation of Aldehydes with Catalytic Significance. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20, 13551–13556. 10.1002/chem.201404204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta R.; Das S.; Hiwase S.; Pati S. K.; Khan S. N-Heterocyclic Germylene and Stannylene Catalyzed Cyanosilylation and Hydroboration of Aldehydes. Organometallics 2019, 38, 1429–1435. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S.; Tsuchiya Y.; Mukaiyama T. Enantioselective Addition Reaction of Trimethylsilyl Cyanide with Aldehydes Using a Chiral Tin(II) Lewis Acid. Chem. Lett. 1991, 20, 541–544. 10.1246/cl.1991.541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W.-B.; Zeng X.-P.; Zhou J.. Carbonyl-Stabilized Phosphorus Ylide as an Organocatalyst for Cyanosilylation Reactions Using TMSCN. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 10.1021/acs.joc.9b03347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Wang J.; Wu Y.; Zhu H.; Samuel P. P.; Roesky H. W. Synthesis of Metallasiloxanes of group 13–15 and their Application in Catalysis. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 13715–13722. 10.1039/c3dt51408k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]