Abstract

Objective

To describe the implementation of telemedicine in a pediatric otolaryngology practice during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic.

Methods

A descriptive paper documenting the development and application of telemedicine in a tertiary academic pediatric otolaryngology practice.

Results

A total of 51 established patients were seen via telemedicine within the first 2 weeks of telemedicine implementation. Seven (7) patients were no shows to the appointment. The median patient age was 5 years old, with 55% male patients. Common diagnoses for the visits included sleep disordered breathing/obstructive sleep apnea (25%) and hearing loss (19.64%). Over half (50.98%) of visits were billed at level 4 visit code.

Discussion

The majority (88%) of visits during the first 2 weeks of telemedicine implementation in our practice were completed successfully. Reasons that patients did not schedule telemedicine appointments included preference for in person appointments, and lack of adequate device at home to complete telemedicine visit. Limitations to our telemedicine practice included offering telemedicine only to patients who had home internet service, were established patients, and English-speaking. Trainees were not involved in this initial implementation of telemedicine.

Conclusions

COVID-19 has driven the rapid adoption of telemedicine in outpatient medicine. Our group was able to institute an effective telemedicine practice during this time.

Keywords: Pediatric otolaryngology, Telemedicine, COVID-19, Healthcare access

1. Introduction

In recent years, interest in telemedicine has been focused on expanding access to healthcare for remote populations [1]. However, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has rapidly accelerated application of telemedicine in an effort to adhere to social distancing and “flatten the curve” of infection [2]. Otolaryngology is a field that relies heavily on decision-making fueled by physical exam findings. Therefore, in prior years, implementation of telemedicine has been challenging and marked by logistical and ethical dilemmas [[2], [3], [4]].

In the United States, March 2020 was the beginning of many statewide “shelter in place” or “stay at home” orders, providing challenges to accessing non-urgent outpatient medical care. In Georgia specifically, March 23, 2020 marked the start of a “shelter in place” order for the medically fragile, and on April 2, 2020, a statewide shelter in place order was announced.

An academic pediatric otolaryngology practice often deals with patients who are immunosuppressed or have chronic medical problems, putting them at higher risk of exposure and infection with COVID-19. These patients are also at risk of complications if their access to pediatric otolaryngology subspecialists is limited for several months. There is a particular subset of pediatric otolaryngology who require active medical management but do not necessarily require an in-person visit for treatment. Telemedicine may address the need to provide a way for these patients to be seen by pediatric otolaryngology specialists while still maintaining social distance.

Until recently, telehealth services were restricted to providers present at an “originating site” and included severe restrictions for billing these services, making them inefficient and cost-prohibitive. However, in mid-March, CMS changed billing for these services under the 1135 waiver and allowed medically necessary services to be delivered via telephone encounters, webcam encounters, or video cell phone technology which is HIPAA compliant. The encounters were also now able to be billed using evaluation and management (E/M) codes with the addition of place of service (POS) code and telephone modifier [5].

Our pediatric otolaryngology practice implemented telemedicine in an effort to provide healthcare to children and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this paper, we describe the early implementation of telemedicine in our practice.

2. Methods

This study was approved by the Children's Healthcare of Atlanta institutional IRB (STUDY00000599). Our practice decided to implement telemedicine in March 2020 in the midst of clinic closure during the COVID-19 pandemic. The first step towards operationalizing telemedicine involved analysis of particular chief complaints which were amenable to this platform. This list was developed by discussing the diagnoses among the providers involved in telemedicine and reaching group consensus in an online meeting. A list of these diagnoses is provided in Table 1 . This diagnosis list was meant as a reference when scheduling patients; however, physicians were free to include other diagnoses on a case-by-case basis.

Table 1.

Reference list of diagnoses amenable to pediatric otolaryngology telemedicine.

| Diagnosis | Additional Criteria Required for Telemedicine Eligibility |

|---|---|

| Neck mass | (1) Completed imaging (CT, US, MRI) |

| (2) Post-operative follow-up | |

| Recurrent acute otitis media | No associated subjective hearing loss complaints or speech delay |

| Hearing Loss | Current cochlear implant or hearing aid users without any recent reported change in hearing, follow up after imaging, lab work or diagnostic audiology |

| Chronic sinusitis | Failure of medical treatment with intranasal corticosteroid and/or antibiotics with symptoms > 3 months |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | Completed polysomnogram |

| Recurrent epistaxis | Not actively bleeding |

| Laryngomalacia | Follow-up only, no associated failure to thrive, acute respiratory distress |

| Dysphagia | (1) Follow-up only, no associated failure to thrive |

| (2) Prior flexible laryngoscopy, direct laryngoscopy/bronchoscopy, or modified barium swallow (MBS) |

Additional inclusion criteria included being an established patient within our practice, having access to an adequate internet connection, and having the ability to download the telemedicine application on their device. Due to constraints in signing “consent to treat” documents, new patients could not be seen via telemedicine during this time [5]. Additionally, patients requiring procedures, patients requiring audiological evaluation, or patients for whom treatment required physical exam which could not be completed via telemedicine (otoscopic, endoscopic) were triaged for urgent in-person appointments at our outpatient clinic. Due to difficulty coordinating interpretation services in the initial implementation phase, only patients who spoke English were eligible for telemedicine.

Physicians individually went through their established patients who were scheduled for appointments on or after March 17, 2020, which was the date all non-urgent clinic appointments were suspended at our institution, and identified patients who required urgent or time-sensitive in-person appointments, those who were telemedicine candidates, and those who were not telemedicine candidates and did not require urgent in-person appointments.

An administrative assistant then contacted patients marked as telemedicine candidates. Patients were required to opt-in to telemedicine appointments. Patients were then scheduled for telemedicine appointments with appointment slots in both Epic Hyperspace and AmWell® (American Well Corporation, Boston, MA) telehealth platform.

Usually, each physician in our practice has 1 day of clinic per week in our main clinic located in the city of Atlanta, and another clinic located within the metro Atlanta area. These community clinics range from 25 min–45 min driving distance from downtown Atlanta. Normal clinic appointment times are between 8 a.m. and 3:30 p.m. For telemedicine, patients were offered clinic appointments between 8 a.m. and 12 p.m. on the physician's original clinic day of the week for both clinic locations. Therefore, patients had more choice of days of the week (2 versus 1) when they could schedule their appointment. Additionally, if patients could not make the appointment times offered, physicians would chose to see patients at other times on a case by case basis.

Of note, there was education offered by our institution on telemedicine throughout the period of implementation. Weekly updates and mentoring about optimizing visits on the telemedicine platform were offered by Information Technology (IT), and the clinical director for telemedicine. Seminars on performing physical exam via telemedicine were also incorporated. Tips on how to document for billing purposes were also disseminated by administrators to physicians using telemedicine in our institution.

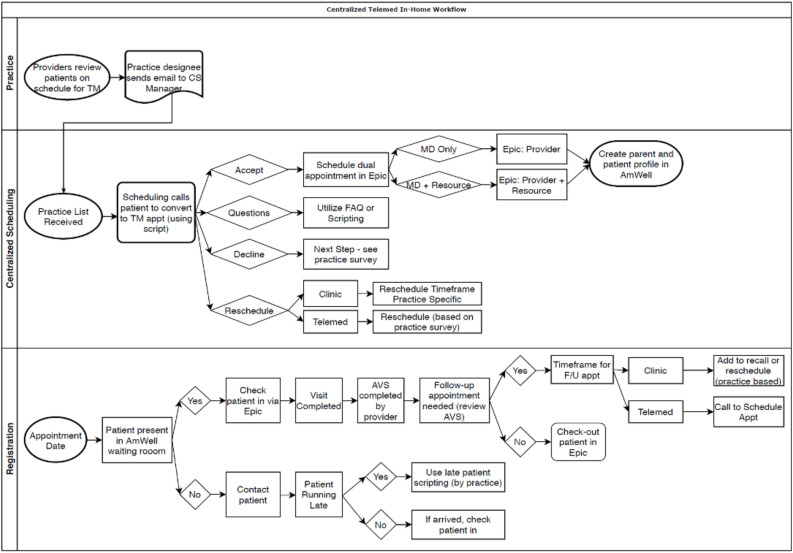

A record of telemedicine scheduling from April 1, 2020 to April 15, 2020 was extracted to provide descriptive information. This two-week time period was chosen for data collection for this study as representing the initial implementation time period for telemedicine within our practice. Information such as patient's demographics, appointment status (cancelled, completed, no show), reason for cancellation, and length of appointment were recorded. The process for scheduling, registering and completing the patient encounters is outlined in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Process map for scheduling and completing telemedicine encounter.

3. Results

A total of 247 established patients within the practice were screened by physicians for telemedicine candidacy. 76 patients were offered telemedicine appointments via telephone contact by an administrative assistant. Eighteen patients declined telemedicine appointments. Reasons for not scheduling a telemedicine appointment included preference for an in-person appointment, lack of adequate device for telemedicine visit, resolution of original medical concern, and no access to the internet. However, the frequency of these decisions was not quantified in this study.

Between April 1, 2020 and April 15, 2020, a total of 58 patients were scheduled for telemedicine visits. 51 patients, or 88%, successfully completed their telemedicine visits. Demographic details of patients seen during this time period are provided in Table 2 A. Chief complaint, diagnosis, and types of orders placed during visits are shown in Table 2B. Reasons that telemedicine visits were not completed included no show (7 patients) and internet connection issues. The patients who did not follow through on their scheduled telemedicine visit were contacted and rescheduled for a later date. When video connection issues were noted as the main barrier to successful telemedicine visit completion, physicians would end the telemedicine visit and convert to a telephone encounter visit. Diagnoses for which patients completed telemedicine visits were more diverse than the group originally developed by physicians detailed in Table 1.

Table 2.

(A) Demographics for complete telemedicine patient visits from April 1–15 2020. (B) Diagnosis and management during completed telemedicine visits from April 1–15 2020.

| Patient Information | Total (n = 51) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 28 (55%) |

| Female | 23 (45%) |

| Median age (years) | 5 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 48 (94%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (4%) |

| Not Disclosed | 1 (2%) |

| Race | |

| African American | 26 (51%) |

| White/Caucasian | 21 (41%) |

| Other races | 2 (4%) |

| Multiple Races | 2 (4%) |

| Median Time from Virtual Rooming of Patient to Checkout (minutes) | 24.6 |

| Chief Complaint/Visit Diagnosis | Cases | Type of Order Placed |

|---|---|---|

| Post-operative follow up | 14 (27.45%) | 1 Imaging |

| Chronic otitis media/eustachian tube dysfunction | 9 (17.65%) | 1 Imaging; 1 Surgery; 1 Lab |

| Hearing loss | 7 (13.73%) | 1 Imaging; 4 Surgery |

| Dysphagia | 4 (7.84%) | – |

| Multiple complaints | 4 (7.84%) | 1 Imaging |

| Sleep disordered breathing/Obstructive | ||

| Sleep Apnea | 3 (5.88%) | 1 Imaging |

| Neck mass | 3 (5.88%) | – |

| Nasal congestion | 2 (3.92%) | 1 Surgery |

| Craniofacial deformities | 2 (3.92%) | – |

| Laryngomalacia | 2 (3.92%) | 2 Imaging; 1 Surgery |

| VF paralysis | 1 (1.96%) | – |

Billing data from complete telemedicine visits is shown in Table 3 . About half (50.8%) of the visits were billed at a level 4 visit, and another one third (35.29%) were billed at a level 3. Coding was completed using level codes based on elements (history, exam and medical decision making) or time spent during the visit. Office-based Evaluation and Management (E/M) coding was used, varying from current procedural terminology (CPT) codes 99.212 to 99.215. Generally, physicians found that coding based on elements was superior to time-based coding. Documentation required for telemedicine included presenting site, hosting site and persons present at the visit. A telemedicine modifier −95 was added to the codes. Coding was performed by the physician at the conclusion of the visit, and verified by a billing and coding specialist. It is standard within our institution for all physician coding to be confirmed by a billing and coding specialist who compares adequacy of documentation to the level of service billed, and also adds modifiers to the visit if necessary.

Table 3.

Billing data for complete telemedicine patient visits from April 1–15, 2020.

| Number of visits (N) | Billing Level for visit |

|---|---|

| 26 (50.98%) | Level 4 |

| 18 (35.29%) | Level 3 |

| 5 (9.80%) | Level 2 |

| 2 (3.92%) | No charge |

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has required rapid adoption of new technologies to improve access to healthcare while maintaining social distancing. Our pediatric otolaryngology practice implemented telemedicine as a way to continue to provide care to our patients during this time. Most patients approached for telemedicine visits were amenable to completing patient care via this platform. Furthermore, over 88% of telemedicine visits were completed successfully. The high completion rate of telemedicine visits in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic implies that patients are responsive to telemedicine.

Our practice is planning a more comprehensive prospective study measuring patient and physician satisfaction with telemedicine in our practice. However, anecdotally, physicians felt that telemedicine visits were usually shorter than in person clinical visits. Additionally, some aspects of the pediatric otolaryngology physical exam such as oral cavity/oropharyngeal exam was noted to be easier to perform during video visits due to improved patient compliance. School age children were especially noted to be more at ease in a home environment versus an office environment, and thus more likely to follow physician and parent instructions to open their mouth sufficiently allowing for a more complete oral exam. This was also an advantage of a video telemedicine encounter as opposed to a telephone visit alone. Physicians did have some difficulties with internet/video connections during telemedicine visits. All physicians had access to a live technical support team to address these connection issues.

Anecdotally, patients commented that telemedicine visits were more efficient since they obviated the need to drive to the appointment and deal with nefarious Atlanta area traffic. Most of our patients have a median 1.5 h drive to our offices throughout the metro Atlanta area, with additional time added on during rush hour times of peak traffic. Additionally, the video technology allowed several family members located in different households to attend the visit with the physician remotely, which is often not possible for in person or telephone visits. Patients also enjoyed the ease of scheduling the appointment around their work schedules.

There are several limitations to our particular telemedicine practice that we are actively working to address. One limitation of the current study is not having a method to quantify the exact reasons 18 patients declined telemedicine appointments. Another significant barrier is that due to “consent to treat” requirements, our practice's telemedicine availability has been limited to established or post-operative patients. We are in the process of providing ways to triage new patients to the practice via telephone encounters, and expanding telemedicine to allow care to new patients. Additionally, our practice usually involves a high rate of non-English speaking patients, and we hope to integrate availability of translation services into our telemedicine platform in the future. We also hope to integrate tele-audiology services into our platform to allow patients who need audiograms to be able to be treated via telemedicine.

Due to the limitation of telemedicine to English speaking patients, and patients who have in-home internet connections, our current telemedicine platform may inadvertently restrict healthcare access to patients from higher socioeconomic groups. Our future efforts to increase and improve inclusion criteria for telemedicine should address these disparities. However, we caution practices who are thinking of implementing telemedicine to keep these limitations in mind and thoughtfully structure their programs to allow healthcare access for all groups.

Another constraint of our current telemedicine model is the inability to have trainees (residents/fellows) participate in telemedicine visits. However, this is another area where the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) is hoping to expand teaching in academic medicine. The Common Program Requirements allowing residents & fellows to be part of telemedicine visits were supposed to go into effect on July 1, 2020 [6]. However, in the context of COVID-19, these have been accelerated and now residents/fellows are allowed to use telemedicine in patient care as long as they are directly supervised by an attending physician supervisor through telecommunication technology [6]. We hope to allow our residents and fellows to be a part of telemedicine visits in the near future.

Future directions in our group involve efforts to analyze the effect of telemedicine on health disparities and access to healthcare through both retrospective and prospective studies. We also aim to provide objective data on physician and patient satisfaction with pediatric otolaryngology telemedicine care.

5. Conclusions

COVID-19 has disrupted the way people interact with each other, necessitating rapid implementation of new technologies to facilitate the need for social distancing. In this paper, we describe the successful implementation of a telemedicine platform in an academic pediatric otolaryngology setting. There is a significant time, financial, and personnel investment for any practice considering starting telemedicine. We hope this paper will provide some insight to other practices contemplating beginning telemedicine. We are actively working on several prospective studies quantitatively examining the financial, time and physician/patient satisfaction responses to telemedicine. Several limitations to our telemedicine platform exist including restriction to English speaking patients, patients with in home internet connections, and the inability to include trainees in patient care. These constraints are being actively addressed. Even after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine may allow for improved healthcare access for pediatric otolaryngology patients who have chronic medical problems requiring medical management but not necessitating an in-person visit.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge April Rains and Brian Potts for their contributions to the telemedicine implementation and provision of data. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Kokesh J., Ferguson A.S., Patricoski C. The Alaska experience using store-and-forward telemedicine for ENT care in Alaska. Otolaryngol. Clin. 2011;44(6):1359–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AC, Thomas E, Snoswell CL, et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Telemed. Telecare. Published online March 20, 2020:1357633X20916567. doi:10.1177/1357633X20916567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Weinstein R.S., Lopez A.M., Joseph B.A. Telemedicine, telehealth, and mobile health applications that work: opportunities and barriers. Am. J. Med. 2014;127(3):183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haegen TW, Cupp CC, Hunsaker DH. Teleotolaryngology: a retrospective review at a military tertiary treatment facility. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery. 130(5):511–518. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Calton B., Abedini N., Fratkin M. Telemedicine in the time of coronavirus. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.019. Published online March 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ACGME response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) ACGME. 2020 https://acgme.org/Newsroom/Newsroom-Details/ArticleID/10111/ACGME-Response-to-the-Coronavirus-COVID-19 Accessed April 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]