Highlights

-

•

Sooting tendencies rankings among different fuels depend on flame conditions.

-

•

Sooting limits of C5–C8 n-alkane is comparable, regardless of carbon-chain length.

-

•

Effects of branched fuel structures on sooting tendency kinetically explained.

-

•

Cyclopentane has even stronger sooting propensity than cyclohexane.

Keywords: Soot formation, Sooting tendency, Counterflow diffusion flame, Cycloalkanes, Alkanes

Abstract

In this work, sooting tendencies of various vaporized C5-C8 alkanes, alkenes, cycloalkanes were investigated in a counterflow diffusion flame (CDF) configuration. Mie scattering and laser induced incandescence (LII) were respectively employed to measure the sooting limits and soot volume fraction, both of which were used as quantitative sooting tendency indices of the flames. Research foci were paid to analyze the impacts of fuel molecular structure on sooting tendencies, ranging from the length of the carbon chain, fuel unsaturation, presence and position of the branched chain as well as the cyclic ring structure. It was found that the present CDF-based sooting tendency data did not always agree with existing literature results that were obtained from either coflow or premixed flame experiments, indicating the importance of considering flame conditions when assessing fuel sooting tendencies. Several interesting observations were made; in particular, our results showed that the sooting limits of C5-C8n-alkane is comparable, regardless of the carbon-chain length, indicating an interesting fuel similarity pertinent to sooting tendency. In addition, we found that cyclopentane, with a five-membered ring, has even stronger sooting propensity than the six-membered cyclohexane; this trend occurs because cyclopentane prefers to decompose to more odd-carbon radicals of cyclopentadienyl and allyl, which are efficient aromatic precursors. Our results are expected to serve as necessary complements to existing sooting index data for a deeper understanding of the correlation between fuel molecular structures and their sooting tendencies.

1. Introduction

Emission of soot particles originating from incomplete combustion of hydrocarbon fuels are known to negatively affect our living conditions. The adverse effects include, but are not limited to, global warming [1,2], air pollution [3], and human health issues. Perhaps not surprisingly, there is recent evidence that suggests air PM pollution is positively correlated with the transmission efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 as well as the case fatality rate of patients who contracted this virus [4,5]. These negative issues pertinent to soot emissions necessitate the development of efficient soot mitigation techniques, which in turn requires a deep understanding of the soot formation processes.

Decades of research has shown that soot formation involves rather complicated physicochemical processes ranging from gas-phase/surface chemistry to particle dynamics [6], [7], [8], [9]. Considerable research efforts have been paid to understand the driving mechanism of soot formation [10], [11], [12] and its dependence on various combustion parameters such as pressure [13], [14], [15], [16], temperature [15,17,18], strain rate [13,19,20] and fuel molecular structures [21], [22], [23], [24]. Due to the diversity of fuel types and the complexity of detailed fuel chemistry, the relationship between fuel structure and soot formation is probably the least understood. Nevertheless, it has been well established that fuel structure is a critical factor in affecting soot evolution and thus the fuel's chemical propensity to soot (i.e., sooting tendency). Fundamentally, different fuels would produce different pools of intermediate radicals, which would notably affect the formation of molecular soot precursors as well as the subsequent soot growth processes [21].

Obviously, the sooting tendency of a particular fuel has a direct impact on the soot emissions of practical combustion devices utilizing the very fuel [25]. The needs to design clean fuels and to develop low-emission combustion techniques motivate research efforts to establish robust quantitative sooting indices for different fuels. Since measurements in practical devices are apparatus-dependent and fuel-consuming [26], researchers typically chose to develop sooting indices based on well-controlled laboratory flames. Existing soot indices include the critical equivalence ratio (or C/O ratio) where soot starts to appear in premixed flames [27] or in a micro flow reactor (with maximum temperature below 1500 K) [28,29], the smoke point (SP) and threshold soot index (TSI) as determined from the critical flame height at which soot begins to emit from the flame tip in a wick-fed lamp or coflow burner [30], [31], [32], and the yield sooting index (YSI) based on the measurement of peak soot volume fraction in a methane/air coflow diffusion flames by doping small amounts of target fuel [33,34]. Several numerical predictive models pertinent to YSI have also been developed [25,[35], [36], [37], [38]]. Moreover, Barrientos et al. [39] extended the TSI methodology and developed oxygen extended sooting index (OESI) to capture the sooting tendency of oxygenated fuels; Lemarie et al. [40] proposed the fuel equivalent sooting index (FESI) to characterize sooting tendency in turbulent spray flames.

These available sooting index data (e.g., YSI and TSI) significantly expands our knowledge and deepens our understanding on fuel sooting propensities. Nevertheless, it is important to note that flame configuration also has a role to play in determining the relative ranking of sooting tendencies among different fuels, which is understandable considering the whole processes of fuel decomposition, formation of molecular soot precursors as well as soot evolution are highly dependent on flame thermal and flow conditions. The widely-used YSI and TSI indices were developed based on either coflow or smoke point flame; these flames behave like a soot formation/oxidation (SFO) flame [41,42] where soot once formed (in the fuel-rich region) will be transported to the high-temperature oxidizing reaction zone to get oxidized. Therefore, the TSI or YSI for a specific fuel essentially represents the net effects of soot formation and oxidation. However, it may be sometimes useful to compare fuel's sooting propensity in the absence of soot oxidation. For instance, pure fuel endothermic pyrolysis occurs in engines for hypersonic aircrafts or rockets [43], where the fuels are used as heat sink to cool the engine structures/subsystems [43,44]. However, the undesired formation of carbonaceous deposits (coking) also occurs in the meantime, and becomes a major limitation for the implementation of fuel cooling technologies [45], [46], [47]. In this regard, focusing on the fuel pyrolysis/soot formation process may be helpful for understanding and resolving the coking issue under fuel pyrolytic conditions. In addition, it is the authors’ opinion that sooting tendency results obtained in soot inception/formation process (without soot oxidation) also complemented YSI data in several aspects. First, since sooting limit represents a critical flame condition where soot starts to appear, it provides a direct measure to predict whether a fuel can form soot under given flame conditions. With a comprehensive knowledge of sooting limits, it is possible to control soot formation at the very beginning and develop soot-free combustion techniques. Second, understanding fuel's sooting propensity in isolated stages of soot evolution (i.e. soot inception, growth or oxidation) helps to determine which stage is most critical to final soot emissions, thus benefiting the design of soot-inhibiting techniques. Third, from a scientific viewpoint, understanding the correlation between sooting tendency and fuel molecular structures in different environments may also enrich our fundamental understanding on the soot formation mechanism.

In such case, it would be beneficial to conduct sooting tendency studies using a counterflow flame configured as the soot formation (SF) type, in which soot particles incepted in the fuel-rich zone continue to grow while being transported away from the oxidizing reaction zone so that oxidation of soot particles are not present. Note the flame and sooting structures of CDFs of both the SF and SFO types have been detailed in a recent review [8] and are thus not elaborated here.

Additional merits of using CDF to study sooting tendencies include the flexibility to study strain rate effect [19], and the ease of data analysis thanks to the quasi-1D nature of CDFs [8]. Therefore, it is our belief that the CDF-based sooting index could serve as necessary complements to the coflow-based data. Although not abundant, several sooting tendency studies have been performed in CDFs, through the measurement of either peak soot volume fraction [48], [49], [50] or critical sooting condition (i.e. sooting limit) [51,52]. In a previous study [19], we also investigated the sooting tendencies of various C1–C4 gaseous fuels in CDFs, and proposed an alternative sooting index for rating sooting tendency of different fuels, i.e. , the sooting temperature index (STI) defined as the critical flame temperature at sooting limit condition; a sooting sensitivity index (SSI) was also introduced to describe the strain rate effects on sooting tendency.

In the present work, we intend to investigate the sooting tendency of C5–C8 alkanes, alkenes and cycloalkanes in CDFs. Petroleum-derived fuels generally contain a wide range of hydrocarbons featured with different chemical functional groups, such as linear and branched alkanes, alkene, cycloalkanes and aromatics [53], [54], [55]. Studying the relationship between fuel structure and its sooting tendency is therefore of practical significance. While McEnally and coworkers have performed a comprehensive YSI measurements for various alkanes, alkene, cycloalkanes, aromatics, alcohols and esters in coflow flames [25,34,56,57], the relevant sooting tendency information are rather scarce in CDFs, especially for heavier liquid fuels (e.g. with carbon atom larger than 5). As will be detailed later, our CDF-based results do not always agree with the YSI data, suggesting the necessity of performing sooting tendency studies in various complementing thermochemical conditions.

The present work is focused on the understanding of the effects of fuel structure on sooting tendency, ranging from the effects of carbon-chain length (comparing C5–C8 n-alkanes), fuel unsaturation (comparing n-hexane and 1-hexene), isomers effects (comparing selected C6H14 isomers of 2-methylpentane, 3-methylpentane, 2,3-dimethylbutane) and the cyclic ring structure (comparing cyclopentane, cyclohexane and methylcyclohexane). Numerical modelling studies were also performed to help understand the kinetic mechanism that lead to the experimental observations.

In the following sections, we shall firstly introduce the experimental setup of light scattering and laser induced incandescence (LII). Subsequently, the numerical approach for kinetic modelling was briefly described. Results on the sooting tendency trend of C5–C8 n-alkanes, selected C6 species and cycloalkanes were then discussed. Finally, major findings of this work were highlighted.

2. Experiments

2.1. Counterflow burner assembly

The counterflow burner consists of two vertically placed nozzles; each nozzle has a diameter of 10 mm and the separation distance between them was 8 mm. The fuel and oxidizer stream were introduced from the lower and upper nozzles, respectively, with the same nozzle exit velocity (V 0). Nitrogen was provided as the shield gas to minimize the disturbance of surrounding air. The flow rates of gaseous species (including N2 and O2) were controlled by calibrated thermally-based mass flow controllers (MKS GE50A), while those of C5–C8 liquid fuels were controlled by a high-precision syringe pump (KDS 230); appropriate dynamic range of these flow controllers were chosen for sufficient resolution and accuracy of the flow rates. The liquid fuel was firstly evaporated in a commercially evaporation system with N2 as the carrier gas and was then transferred to the bottom burner, which, along with the whole fuel transfer lines, was heated to avoid fuel re-condensation. The initial temperature of fuel and oxidizer stream were controlled at 473 K and 293 K, respectively.

2.2. Sooting limits measurement

A light scattering/extinction system was set up to obtain the sooting limits (i.e., critical conditions for soot formation in terms of fuel and oxygen mole fraction, to be detailed later). A more complete description of the optical layout can be found elsewhere [19], while a schematic is shown in Fig. 1 . As can be seen, a 514.5 nm Argon-ion laser was used as light source. The laser beam was firstly expanded before being refocused to reduce beam diameter at the flame region, contributing to improve the spatial resolution of the measurements. A photodiode (Thorlabs, DET100A) assembled with an integrating sphere was used to detect the attenuated beam for extinction measurement, and a photomultiplier tube (PMT) placed at 90° to the incident beam path was employed to detect the scattering signal. The convex lens, linear polarizer, pinhole (50 μm) and narrow band filter (FWHM =1 nm) in front of the PMT were used to direct the scattered light to the PMT and reject background illumination. A lock-in amplifier (SRS SR830) with the reference signal provided by a mechanical chopper (SRS SR540) was used to condition the scattering signal for efficient noise rejection. Note the scattering setup has been confirmed to be free from interference of spurious light reflected from other surfaces.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the light scattering and extinction setup (MR: silver Mirror; HW: half-wave plate; CCL: concave lens; CVL: convex lens; IS: integrating sphere; PD: photodiode; PH: pinhole; PZ: polarizer; BF: band-pass filter; PMT: photomultiplier tube).

Sooting limits in this work are defined as the critical X F/X O (defined as the fuel/oxygen mole fraction in the N2-diluted fuel/oxidizer stream) where soot starts to appear, determined by comparing the Rayleigh scattering signals from the gas molecules and Mie scattering singnals from the soot particles [19,52]. The procedure was illustrated in Fig. 2 where experimental scattering intensity profiles are shown for n-hexane flame at (a) X F = 0.8 with different X O and (b) X O = 1.0 with different X F; the scattering intensity reported in Fig. 2a and b were all obtained by multiplying the raw PMT signal intensity with the same scaling factor. Fig. 2a shows that at a non-sooting condition (X O = 0.28), the Rayleigh scattering intensity shows a decreasing trend from the fuel to the oxidizer side; this trend occurs because the fuel molecules have larger scattering cross-section than the oxidizer gases. When soot starts to form (X O = 0.285), a local peak appears due to the stronger Mie scattering from soot particles. With further increase in X O (X O = 0.29), the Mie scattering intensity starts to increase rapidly. Thus, the sooting limit is defined as X O,cr = 0.285. Such case corresponds to a SF flame where the flame front is located on the oxidizer side of stagnation plane. The formed soot will be transported towards the stagnation plane, away from the high temperature flame region zone with limited oxidation; Similarly, for a fixed X O of 1.0, the sooting limit of X F,cr = 0.135 can be determined from Fig. 2b. This kind of flame can be classified as of SFO type for which the flame region was located on the fuel side of stagnation plane, meaning that soot particles, after being incepted, will be directed towards the flame region and get oxidized. Since the interval of X F or X O is 0.5% (0.005), the experimental uncertainty of sooting limits (in terms of X O,cr and X F,cr) is expected to be within ±0.25%.

Fig. 2.

Scattering intensity profiles for n-hexane (a) SF flames with XF = 0.8 at several XO case and (b) SFO flames with XO = 1.0 at several XF condition (V0 = 45 cm/s).

All sooting limits were measured at the nozzle velocity of V 0 = 45 cm/s. It is worthwhile to point out here that by varying the fuel/oxygen mole fractions (X F or X O) or fuel types, the strain rate would also be changed due to the variation of fuel/oxidizer stream density [58]. Nevertheless, we have confirmed that the variation is rather small and has negligibly small effects on the observed difference in sooting tendency among the tested fuels.

2.3. LII measurements

Besides sooting limits, LII measurements were also performed to compare sooting tendency using the index of peak in-flame soot volume fraction (SVF). This yield-based sooting index may provide complementary information to the above-discussed sooting limits, as the latter is more relevant to the limiting soot onset conditions.

Regarding the LII setup, a 10 Hz pulsed Nd-YAG laser with a fundamental emission at 1064 nm was used [50,59,60]. The laser beam was manipulated by a series of cylindrical lens to form a laser sheet (8 mm high) at the burner center. The LII signals were collected by an intensified CCD camera after passing through a band-pass filter with a center wavelength of 400 nm (FWHM = 40 nm). The camera gate open time was synchronized to the incident laser and the gate width was set to 80 ns. The LII signals were averaged from 600 laser shots to improve signal to noise ratio, with an estimated measurement uncertainty of less than 5%.

LII signals were calibrated by performing additional light extinction measurements with a near-infrared laser beam (λ = 980 nm). The purpose of using a near-infrared laser wavelength was to minimize the interference of light absorption by PAHs. In deriving the absolute SVF, we used the soot refractive index value of m = 1.57−0.56i [42,61].

In addition, we performed tomographic inversion [62] to obtain the local light extinction coefficient K ext from the line-of-sight integrated data. More details concerning the data processing procedure can be found in our previous studies [42,63]. In our setup, the calibration factor was 10,000 LII signal counts to an SVF of 0.363 ppm. The systemic uncertainty of absolute SVF was estimated to be around 20%, which primarily originates from the uncertainty in the soot refraction index m [64,65]. However, since this systematic uncertainty is highly likely to be the same for all the tested fuels, it has no effects on the relative comparisons of SVF among different fuels. On the other hand, the random uncertainty of SVF was estimated to be less than 5% (through over 600 repeated LII measurements).

The LII measurements were performed for all target fuels at identical flame condition of X F = 0.35 and X O = 0.3, with V 0 = 20 cm/s. The purpose of using a lower nozzle velocity (V 0 = 20 cm/s) in LII measurements than that of scattering experiments (V 0 = 45 cm/s) is to achieve moderately sooting flames for all the target fuels. Note since no cross-comparison was made between sooting limits and SVF (as they represent totally different sooting condition), the nozzle velocities need not necessarily to be the same for scattering or LII measurements.

3. Numerical approach

Kinetic modelling with detailed fuel pyrolysis and oxidation chemistry were performed to help understand the experimentally observed sooting tendency results. The main objective was to elucidate the fuel structure-dependent pathways of fuel decomposition and soot precursors (e.g., benzene) formation, which are expected to provide essential insights into the relationship between fuel structure and sooting propensity. This approach was rationalized since for aliphatic fuels such as those investigated in this work, benzene formation is thought to be the rate-limiting step to the subsequent polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) and soot formation process [66], [67], [68].

All simulations were performed with the Closed Homogeneous Reactor (CHR) model in the CHEMKIN-PRO package [69]. The simulations were set at a thermodynamic condition ofP = 1 atm and T = 1500 K, for mixture of 10% fuel and 90% Ar. The chosen temperature of T = 1500 K represents the local thermal environments where fuel pyrolysis processes takes place in a CDF, although the maximum flame temperature would be considerably higher [70]. Such approach of relying on the fuel pyrolysis and soot precursor formation pathways analyses in 0-D reactor to provide kinetic insights into the observed sooting tendency trend in diffusion flames has also been widely used by other researchers [71,72]. Since no single mechanism exists with the capability to describe the decomposition chemistry of all the target C5–C8 fuels, the chemical kinetic mechanism JertSurF 2.0 [73] was used for C5–C8 n-alkanes, while the mechanism developed by Zhang et al. [74] and Tian et al. [75] were employed for selected C6 fuels (hexane isomers/1-hexene) and cycloalkanes, respectively. Note we actually used the same kinetic model to analyze each individual fuel structure effect (carbon-chain length, isomers/fuel unsaturation or cyclic ring structure), meaning no comparisons were made between data obtained from different mechanisms.

Note the present experiments and simulations were performed for all the fuels under the same temperature boundary conditions. Although the differences in fuel types would induce variation of flame temperature which may in turn affect soot formation, we have confirmed that the temperature difference among the tested fuels is rather small which is believed to have negligible small effects on their sooting tendencies. Therefore, we would like to attribute the observed ranking of sooting tendency to the difference of fuel structure.

4. Results and discussion

In this section, experimental data and kinetic analyses were first presented for C5–C8 n-alkanes to understand the effects of carbon-chain length on sooting tendency for normal alkane fuels. Subsequently, the sooting tendency of selected C6 fuels were compared to study the effects of fuel unsaturation, position and number of side chains. Finally, the effects of cyclic ring size and the presence of ring-attached side chains were discussed for selected cycloalkanes.

4.1. Sooting tendency of C5–C8n-alkanes

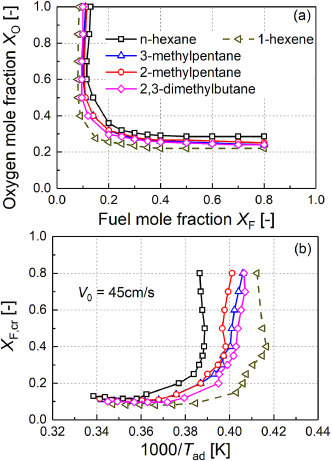

Fig. 3 shows the sooting limits of C5–C8 n-alkanes in the X F-X O plane. The symbols represent sooting limit conditions, i.e. the critical X o,cr (X F,cr) at a fixed X F (X O). Note the flame condition of X F = 1.0 is absent because a carrier gas is a necessity in the fuel stream for vaporization of liquid fuels. The solid lines connecting the symbols divide the X F–X O plane into two regions: the upper-right zone being the sooting region and the remaining areas non-sooting. The flame location (relative to stagnation plane) is dependent on X F and X O; the criterion for flame located at the stagnation plane is , in which Y is the mass fraction, Le is the Lewis number, the subscripts O and F represent the oxidizer and the fuel, respectively. The criterion is plotted as the green dot dash line for n-hexane and the RHS (LHS) of the line corresponds to SF (SFO) flame [52].

Fig. 3.

Sooting limit map of C5–C8n-alkanes measured at V0 = 45 cm/s

Before comparing the sooting tendency trend of the C5–C8 n-alkanes, we would like to further eloborate on the general features of the sooting limit map, which provides rich information for a deep understanding of the sooting characteristics in counterflow flames. First, for SF flame with large X F, the critical X o,cr increases quite slowly as X F decreases from X F = 0.8 to 0.4, in such a way that the sooting limit curve has a nearly horizontal boundary. As X F further decreases to 0.2, the critical X o,cr starts to increase sharply. Second, in the SF flame regime, the sooting limit curve closely follows the adiabatic flame temperature (iso-AFT) line (T ad = 2580 and 2890 K were shown, which were calculated for n-hexane using equilibrium calculation in CHEMKIN-PRO using the mechanism of JetSurF 2.0 [73]). This suggests that flame temperature plays a critical role in determining the sooting limits of SF flames, The reason for that has to do with the lacking of soot oxidation process in SF flames, where the temperature-dependent fuel pyrolysis and soot precursor formation processes exert dominant effects. On the other hand, for SFO flames, the sooting limit curves deviate noticeably from the iso-AFT line, which can be explained by the fact sooting limits of SFO flames is also influenced by the oxidation process in addition to flame temperature. Third, we noticed that the sooting limit curves bent slightly towards larger X F in the large X O regime. In other words, there exists two corresponding X O,cr for a given X F, indicating an non-monotonic variation of sooting tendency with X O. This interesting phenomena has been previously observed [19,41,52,76], and was successfully explained in our previous work [42]. Briefly speaking, the observed non-monotonic variation of soot concentration with the increase of X O is caused by the competing effects of soot inception, soot surface growth, and soot oxidation process [42]. In particular, increasing X O would lead to the reduction of soot inception rates and the enhancement of soot oxidation, both of which tend to inhibit soot formation. However, increases of X O would also enhance the soot surface growth rate which, on the contrary, enhances soot formation.

Generally speaking, fuels with stronger sooting propensity would have correspondingly larger sooting region in the X F-X O plane [19]. However, it was found in Fig. 3 that the sooting limit curve boundary of the C5–C8 n-alkanes is close to each other, especially in the soot formation flame region (large X F). This indicates that these n-alkanes has comparable sooting tendency, being insensitive to the carbon-chain length. Presumably, this trend occurs because the dominant reaction pathways and rates towards soot formation are similar among the C5–C8 n-alkanes. This kind of fuel similarity pertinent to sooting tendency is rather interesting, as it may help to simplify the description and prediction of sooting tendency for heavier alkanes. However, this conclusion cannot be projected to smaller alkane, as it has been reported in [19] that the sooting region of smaller C1–C4 n-alkanes in the X F–X O plane was noticeably expanded with the increase of carbon atoms. The different sooting propensity among smaller alkanes (e.g. between methane and propane) may be due to the different pathways to form soot precursors and soot. This point will be further elucidated later on.

Considering the significant effects of flame temperature on sooting characteristics [17,77], it is interesting to further examine the relationship between the present sooting limits (X O,cr, X F,cr) and flame temperature. To this end, we plotted the X F,cr and X O,cr in relation to the adiabatic flame temperature (T ad) in Fig. 4 . Note the value of T ad at corresponding (X O,cr, X F,cr) is not necessarily the real temperature where soot just appears, but is used here as a quantitative indicator of the sooting tendency of a fuel (as will be explained below). It is shown in Fig. 4a that, the limiting temperature of SF flames at sooting limit condition remains nearly constant over a wide range of X F,cr; this implies that there exists a limiting threshold temperature for soot onset (T cr,SF) for SF flames: the flame will be sooting if it has a higher temperature than T cr,SF. On the other hand, Fig. 4b shows an approximately linear dependence of log X O,cr on 1/T ad; the flame temperature of SFO flames increases with increasing X O,cr.

Fig. 4.

(a) Critical fuel mole fraction XF,cr and (b) critical oxygen mole fraction XO,cr in relation to adiabatic flame temperature (Tad) for C5–C8n-alkanes (V0 = 45 cm/s).

More importantly, it has been demonstrated [19,52] that the limiting threshold temperature T cr,SF of SF flames is fuel structure-sensitive and, could be used as an quantitative sooting index. That is, fuels with lower T cr,SF generally have stronger sooting propensity. In addition, it was suggested in Ref. [19] that T cr,SF can be defined as the temperature at X F,cr = 1.0 for gaseous fuels or at a diluted X F,cr for liquid fuels, when a carrier gas is needed to achieve vaporization. Here, we artificially defined the T cr,SF as the temperature of SF flames at X F,cr = 0.6. In this regard, we may also conclude from Fig. 4a that the large n-alkanes have comparable limiting sooting temperature, especially for C6–C8 n-alkanes (n-pentane has relatively smaller value). This temperature-based sooting index was in agreement with the sooting region in X F-X O plane, both supporting the fuel similarity in sooting tendency for large n-alkanes, regardless of their carbon-chain length.

Nevertheless, the present CDF-based sooting limits seem to different from the coflow-based YSI data [34], which was seen to increase steadily with carbon-chain length for C5–C8 n-alkanes (n-pentane: YSI -8.9, n-hexane: YSI 0, n-heptane: YSI 8.7, n-octane: YSI 18.9). Such disagreement is likely due to the different sooting index used for ranking the sooting tendency. Note the present sooting limits essentially represent a critical condition where soot just appears, which is more relevant to soot inception process. In contrast, the YSI data is a measure of soot volume fraction in which soot growth and oxidation process (besides soot inception) also take important roles.

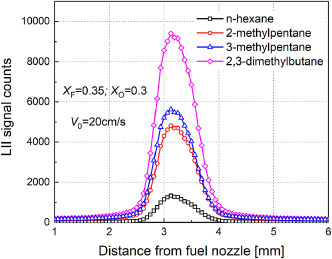

To validate whether the choice of sooting index matters, we also performed additional LII measurements at identical flame condition of X F = 0.35 and X O = 0.3 (SF flames); the peak LII intensity was used as yields-based index for ranking fuel's sooting tendency (called LII-based sooting index), which represents the effects of both soot inception and soot growth process. The LII data shown in Fig. 5 confirm that longer n-alkane has slightly higher soot yields, being consistent with the YSI data. These observations suggest that the LII-based sooting index is more sensitive to carbon-chain length as compared to the sooting limits. However, it is the authors’ opinion that the sooting limits may complement the YSI data in representing the fuel's chemical propensity to form soot, by focusing on critical sooting conditions and excluding interference from the soot oxidation process.

Fig. 5.

Measured LII intensity profiles for C5–C8n-alkanes (XF = 0.35 and XO = 0.3)

What remains unclear is why these large n-alkanes has comparable sooting limits (i.e. sooting propensity), in spite of the difference in carbon-chain length. To this end, mechanistic analyses were performed to focus on the fuel decomposition and benzene formation pathway. The simulation results on fuel pyrolysis process with the Closed Homogeneous Reactor model (see Fig. 6 ) showed that these large n-alkanes in the same chemical family essentially undergo similar fuel decomposition and benzene formation process. Specifically, fuel consumption was initiated by the C-C fission and H-atom abstraction reactions; this process produces a wide range of n-alkyl radicals, which were subsequently decomposed to produce ethylene and other larger alkenes. These alkenes then grow (in the case of ethylene) or decompose (for large alkenes) to produce benzene precursors such as propargyl (C3H3) and C4 species, which determined the benzene formation rate via the reaction of C3H3 + C3H3 and C4+ C2.

Fig. 6.

Schematic decomposition pathways of C5-C8n-alkane. Calculated using the JetsurF 2.0 mechanism [73] for mixtures 10% fuel+90% Ar at condition of T = 1500 K and P = 1 atm. Fuel consumption rate is approximately 80%. The numbers indicate the percent contribution to the consumption of the source species.

In addition, since all the C-C bond and C-H bond in these large n-alkanes has quantitatively similar bond strength, the C—C fission (or H-abstraction reaction) occurs at a comparable rate [21]. The simulations showed that at fuel consumption rate of 80%, the percentage contribution of C-C fission (or H-abstraction reaction) is at similar level of 32–38% (68–62%). Consequently, the rate to produce intermediate alkenes and thus benzene precursors are also quantitatively similar for these alkanes. Specifically, since ethylene takes the most proportion among various decomposed alkenes (more than 80%, regardless of carbon-chain length), the pathway of ethylene reacting with C1 and C2 species to form benzene precursors C3H3 and C4 become dominant. Note although longer n-alkanes tend to produce larger alkenes beyond ethylene, its effects on the overall sooting limits is relatively small. Nevertheless, it should be pointed out here that the slightly higher amounts of intermediate large alkenes from longer n-alkane may explain why larger n-alkane produce evidently more soot in the LII experiments [34].

Hence, we may tentatively conclude that the comparable sooting limits among the C5–C8 n-alkanes is due to their similar fuel decomposition and benzene formation pathways and rates. On the other hand, the notable difference in sooting propensity among smaller n-alkanes (e.g. methane and propane) [19] may be attributed to the different fuel decomposition activity. This is because the C—H bond for methane (438 kJ/mol) is much larger than the C-C bond energy of propane (371 kJ/mol), making it much more difficult to break to produce initial methyl radical (CH3). Moreover, the growth of CH3 to form benzene precursors also requires relatively slower addition reactions towards important C2 and C3 species for methane than that of propane.

4.2. Sooting tendency of selected C6 fuels

Now we move on to discuss the effects of fuel unsaturation (the C=C double) and isomers effects (the position and numbers of side-chains) on sooting tendency, by comparing n-hexane/1-hexene and n-hexane/C6H14 isomers including 2-methylpentane, 3-methylpentane, 2,3-dimethylbutane, respectively. Fig. 7 shows the sooting limits (X F,cr, X O,cr) in X F-X O plane for these selected C6 fuels. Also included is the relation of critical X F,cr to the calculated adiabatic flame temperature (T ad) to compare their sooting tendencies through the alternative index of limiting sooting temperature (T cr,SF).

Fig. 7.

(a) sooting limit map for selected C6 fuels and (b) the critical fuel mole fraction XF,cr in relation to adiabatic flame temperature (Tad) at V0 = 45 cm/s.

Fig. 7 shows that 1-hexene has noticeably larger sooting region and smaller T cr,SF than n-hexane, indicating the stronger sooting propensity of 1-hexene. This result is not surprising as many other sooting tendency studies [19,34,39,56,78] also reported that the unsaturated fuel (esters, oxygenates) with the C=C double bond is more sooting than their saturated counterparts. However, mechanism investigations into the effects of C=C double bond is relatively limited.

To obtain further information on how the presence of C=C double bond in the fuel molecules could lead to higher sooting tendency, the fuel decomposition pathways of 1-hexene were numerically investigated and compared with those of n-hexane. As can be seen in Fig. 8 , the predominant decomposition route of 1-hexene is the unimolecular dissociation via allylic C–C fission (i.e., the bond between C3 and C4), which accounts for 86% of total 1-hexene consumption. As a result of the allylic C–C fission, large amounts of n-propyl (nC3H7) and allyl radical (aC3H5) were produced; similar pyrolysis result of 1-hexene were reported in the literature [79]. In contrast, n-hexane is primarily decomposed via C-C fission and H-abstraction reaction, producing various n-alkyl radicals (such as PC4H9, nC3H7 and C2H5) which were then converted to ethylene. Due to the large amounts of the decomposition products of aC3H5, it is relatively easy for 1-hexene flame, as compared to n-hexane, to produce the important benzene precursor of C3H3 via the dehydrogenation of aC3H5 (aC3H5→aC3H4/PC3H4→C3H3). On the other hand, the decomposition product of nC3H7 are mostly (~ 60%) converted to unsaturated C2H4 and C3H6, which also in turn contribute to C3H3 formation. Although not shown, the maximum concentration of C3H3 from 1-hexene decomposition is more than twice than that from n-hexane, leading to its much higher benzene production rates (via C3H3+C3H3). This fact may explain why 1-hexene has stronger sooting propensity than n-hexane.

Fig. 8.

Fuel decomposition pathways of n-hexane, 1-hexene and 2,3-dimethylbutane. Calculated using the mechanism of Zhang et al. [74] at condition of T = 1500 K and P = 1 atm for mixture of 10% fuel+90% Ar. Fuel consumption rate is approximately 80%. The numbers indicate the percent contribution to the consumption of the source species.

With respect to the isomeric effects for hexane, it can be found from Fig. 7 that all the branched C6H14 isomers were more sooting than the straight chain n-hexane. While among these C6H14 isomers, the difference in the sooting limit curve boundary and T cr,SF is not quite evident; but a general trend of smallest T cr,SF for 2,3-dimethylbutane can be observed, followed by 3-methylpentane and 2-methylpentane. On the other hand, the LII-based sooting index in Fig. 9 shows that 2,3-dimethylbutane with two methyl-branch has significantly larger soot volume fraction than mono-branched one; while the difference in soot yields between 2-methylpentane and 3-methylpentane is much smaller (with 3-methylpentane being slightly larger). The present LII results show that the sooting tendency of C6 alkane tends to increase with the number of methyl-branch, but are not very sensitive to the specific position of the branch, which agree with the literature-based YSI data [34].

Fig. 9.

Measured LII intensity profiles for n-hexane and its isomers (XF = 0.35 and XO = 0.3) at V0 = 20 cm/s.

The fuel decomposition pathways of 2,3-dimethylbutane is included in Fig. 8 to elucidate the reason why more branched C6 alkane has stronger sooting propensity than straight-chained counterpart. The kinetic simulation shows that 2,3-dimethylbutane is likely to produce large amounts of iso-propyl (IC3H7), which were then decompose primarily to C3H6; this situation differs significantly from n-hexane decomposition which mainly produce nC3H7 and then C2H4. Quantitatively, the ratio in maximum concentration of C3H6 to C2H4 is 0.9 for 2,3-dimethylbutane, larger than the ratio of ~0.44 for mono-branched C6H14 and 0.14 for straight-chained n-hexane. Consequently, the formation rate of benzene precursor C3H3 in 2,3-dimethylbutane is governed by the C3H6 initiated reactions (via dehydrogenation of C3H6 to form C3H3), which is faster than the C2H4-dominated pathway (C2H4 + C1 species) in n-hexane.

4.3. Sooting tendency of cycloalkanes

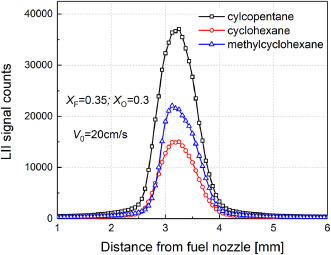

In this section, the sooting tendency of selected cycloalkanes, i.e. cyclopentane (cC5H10), cyclohexane (cC6H12) and methylcyclohexane (cC7H14), were compared to investigate the effects of cyclic ring size (comparing cC5H10 and cC6H12) and the presence of ring-attached side chain (comparing cC6H12 and cC7H14). Fig. 10 a compares the sooting limits in X F-X O plane for these cycloalkanes; their sooting region does not show significant difference, expect that the sooting limit curve of cC5H10 (cC7H14) slightly expands towards large X F (X O) region. Interestingly, if we plot the critical X F,cr with respect to T ad in Fig. 10b, it is easy to see that cC5H10 has smaller limiting sooting temperature (i.e. T SF,cr at X F = 0.6) than cC7H14 or cC6H12, indicating the sooting tendency trend of cC5H10 > cC7H14 > cC6H12. This trend is consistent with the LII-based sooting index shown in Fig. 11 , in which the peak LII intensity also shows the order of cC5H10 > cC7H14 > cC6H12.

Fig. 10.

(a) sooting limit map and (b) the critical fuel mole fraction XF,cr in relation to adiabatic flame temperature for cyclopentane, cyclohexane, methylcyclohexane (V0 = 45 cm/s)

Fig. 11.

Measured LII intensity profiles for Cyclopentane, Cyclohexane and Methylcyclohexane (XF = 0.35 and XO = 0.3) at V0 = 20 cm/s

It is noticed that the stronger sooting propensity of cC7H14 than cC6H12 obtained in the present CDFs agree with the coflow-based smoke point data [80] and YSI data [34]. However, disagreement appears with respect to the relative sooting tendency trend of cC5H10 and cC6H12. Specifically, the present sooting limits/LII data was consistent with the smoke point data [80], which reported the sooting tendency trend of cC5H10 (33.1 mm) > cC6H12 (51.9 mm). Note the fuels with smaller smoke point (i.e. the critical flame height at which soot begins to emit from the flame tip) has stronger sooting propensity. However, the YSI data [34] indicated an opposing sooting tendency trend of cC5H10 (YSI 14.0) < cC6H12 (YSI 19.1). One possible reason for such disagreement may be the potential chemical cross-linking effects between methane and the dopant fuel during YSI measurement [34], which is different from our works and the smoke point measurements [80] in which pure fuel was used. However, it is difficult to explicitly point out the origins of such disagreement which, of course, deserves further investigations.

In this work, we are more interested in the reason why the five-membered cC5H10, despite of its smaller ring size, is more sooting than the six-membered cC6H12. To uncover the underlying mechanism, we performed fuel decomposition pathway analyses for cC5H10 and cC6H12, using the mechanism developed by Tian et al. [75] with the CHR model. As far as the authors aware of, this may be the first study trying to elucidate the mechanism why an increase in ring size conversely reduce the sooting tendency of cycloalkanes in CDFs.

Similar to alkanes, benzene formation also play a critical role to the subsequent PAH and soot formation rate for cycloalkanes [21,81]. The results in Fig. 12 shows that cC5H10 decomposition produces higher amounts of benzene than that of cC6H12, being consistent with their observed sooting tendency trend. Further ROP-based analyses revealed that benzene formation during cC5H10 and cC6H12 decomposition is dominated by the route of C3H3 + C3H3. Since cC5H10 decomposition produces higher amounts of C3H3 than cC6H12 (see Fig. 12), the higher benzene formation tendency of cC5H10 can be easily understood.

Fig. 12.

Time profiles of benzene (C6H6) and propargyl (C3H3) mole fraction calculated using the mechanism of Tian et al. [75] at T = 1500 K and P = 1 atm for mixture of 10% fuel + 90% Ar.

Fundamentally, the difference in C3H3 production between cC5H10 and cC6H12 decomposition is related to the fuel structure dependent decomposition pathways. As shown in Fig. 13 , the fuel consumption processes of cC5H10 and cC6H12 do share a similar route via the ring-opening isomerization to alkenes which then primarily translate to aC3H5 and n-alkyl. However, difference appears in the other decomposition route from the ring structure of cC5H9 and cC6H11. Specifically, the subsequent decomposition of cC5H9 prefers to produce odd-carbon radicals of cyclopentadienyl (C5H5) and aC3H5, which then convert primarily to C3H3 via the reaction of C5H5 = C3H3 + H2 and the dehydrogenation of aC3H5, respectively. In contrast, cC6H11 tends to produce C4 and C2 species; this indeed makes cC6H12 have higher benzene formation rate via the reaction of C4 + C2 than cC5H10, however, it only plays a secondary role to total benzene formation. Consequently, cC5H10 has faster C3H3 and benzene formation rate than cC6H12, leading to the stronger sooting propensity of cC5H10.

Fig. 13.

Fuel decomposition pathways for cyclopentane and cyclohexane calculated using the mechanism of Tian et al. [75] at T = 1500 K and P = 1 atm for mixture of 10% fuel+90% Ar. Fuel consumption rate is approximately 80%. The numbers indicate the percent contribution to the consumption of the source species.

The above discussions concerning the benzene formation chemistry provide reasonable explanations for the observed sooting tendency between cC5H10 and cC6H12. However, Further investigations by comparing their PAH growth/soot evolution process is also required. For instance, it has been suggested that the PAH formation pathway via the self-combination of C5H5 (to form naphthalene) may also play a role to soot formation of cC5H10 flames [82,83]. Unraveling the possible roles of the C5H5 related PAH pathways would help to provide a more comprehensive understanding for the observed sooting tendency among the cycloalkanes.

4.4. Concluding remarks

This work experimentally investigated the sooting tendency of liquid C5–C8 alkanes, alkenes and cycloalkanes in counterflow diffusion flames, using both the sooting limits and soot volume fraction as quantitative sooting indices. The main objective is to clarify the fuel structure effects (including carbon-chain length, isomers, fuel unsaturation and cyclic ring structure) on sooting tendency, with the help of numerical analyses on the fuel decomposition/soot precursor formation pathways. Major conclusions and findings are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

The larger C5-C8 n-alkanes has comparable sooting limits among each other, in contrast to the smaller C1–C4 n-alkane in which notable difference in their sooting limits were previously observed. This result indicates a rather interesting fuel similarity with respect to sooting tendency among these large n-alkanes. This trend occurs because the sooting limits is mostly related to the specific fuel decomposition and benzene formation pathways, which is essentially similar for the C5–C8 n-alkane regardless of their carbon-chain length. This may help to simplify the prediction on sooting tendency of large n-alkanes.

-

(2)

The presence of fuel unsaturation in 1-hexene leads to its stronger sooting tendency than n-hexane, as 1-hexene tend to produce more amounts of allyl radical and therefore has faster benzene precursor (C3H3) formation rate. On the other hand, all the branched C6H14 (2-methylpentane, 3-methylpentane, 2,3-dimethylbutane) has larger sooting propensity than n-hexane; while the sooting tendency of C6H14 isomers increased with the number of methyl-branch, but is not very sensitive to the position of methyl-branch. Numerical pathway analyses revealed that more branched C6H14 decomposes larger amounts of C3H6 than the straight one (which primarily produces C2H4), thus leading to its higher sooting tendency.

-

(3)

The present CDF-based sooting limits and LII data shows that the five-membered cyclopentane has even stronger sooting propensity than the six-membered cyclohexane. Numerical pathway analyses showed that, compared to the decomposition of cyclohexane which primarily produces C4 species, cyclopentane tends to decompose to more odd-carbon radicals (such as allyl and cyclopentadienyl radical) and thus has faster benzene formation rate and stronger sooting tendency. Note our result is inconsistent with the coflow-based YSI data in which a higher sooting tendency of cyclohexane than cyclopentane was reported. This result suggests the necessity of evaluating fuel's sooting tendency in different flame environments.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51606136, 51976142).

References

- 1.Bond T.C., Doherty S.J., Fahey D.W., Forster P.M., Berntsen T., Deangelo B.J. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: a scientific assessment. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2013;118:5380–5552. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiore A.M., Naik V., Leibensperger E.M. Air quality and climate connections. J Air Waste Manag. 2015;65:645–685. doi: 10.1080/10962247.2015.1040526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang R.-J., Zhang Y., Bozzetti C., Ho K.-F., Cao J.-J., Han Y., Daellenbach K.R., Slowik J.G., Platt S.M., Canonaco F., Zotter P., Wolf R., Pieber S.M., Bruns E.A., Crippa M., Ciarelli G., Piazzalunga A., Schwikowski M., Abbaszade G., Schnelle-Kreis J., Zimmermann R., An Z., Szidat S., Baltensperger U., Haddad I.E., Prévôt A.S.H. High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China. Nature. 2014;514:218–222. doi: 10.1038/nature13774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao Y., Pan J., Wang W., Liu Z., Kan H., Qiu Y., Meng X., Wang W. Association of particulate matter pollution and case fatality rate of COVID-19 in 49 Chinese cities. Sci Total Environ. 2020;741 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zoran M.A., Savastru R.S., Savastru D.M., Tautan M.N. Assessing the relationship between surface levels of PM2.5 and PM10 particulate matter impact on COVID-19 in Milan, Italy. Sci Total Environ. 2020;738 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Anna A. Combustion-formed nanoparticles. Proc Combust Inst. 2009;32:593–613. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H. Formation of nascent soot and other condensed-phase materials in flames. Proc Combust Inst. 2011;33:41–67. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y., Chung S.H. Soot formation in laminar counterflow flames. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2019;74:152–238. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karataş A.E., Gülder Ö.L. Soot formation in high pressure laminar diffusion flames. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2012;38:818–845. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen D., Luo K.H. Reactive sites on the surface of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon clusters: a numerical study. Combust Flame. 2020;211:362–373. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen D., Akroyd J., Mosbach S., Kraft M. Surface reactivity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon clusters. Proc Combust Inst. 2015;35:1811–1818. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansson K.O., Head-Gordon M.P., Schrader P.E., Wilson K.R., Michelsen H.A. Resonance-stabilized hydrocarbon-radical chain reactions may explain soot inception and growth. Science. 2018;361:997–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.aat3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarnacki B.G., Chelliah H.K. Sooting limits of non-premixed counterflow ethylene/oxygen/inert flames using LII: effects of flow strain rate and pressure (up to 30 atm) Combust Flame. 2018;195:267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue X., Singh P., Sung C.-J. Soot formation in counterflow non-premixed ethylene flames at elevated pressures. Combust Flame. 2018;195:253–266. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gleason K., Carbone F., Gomez A. Pressure and temperature dependence of soot in highly controlled counterflow ethylene diffusion flames. Proc Combust Inst. 2019;37:2057–2064. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang S., Li Z., Gao J., Ma X., Xu H., Shuai S. PAHs and soot formation in laminar partially premixed co-flow flames fuelled by PRFs at elevated pressures. Combust Flame. 2019;206:363–378. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gleason K., Carbone F., Gomez A. Effect of temperature on soot inception in highly controlled counterflow ethylene diffusion flames. Combust Flame. 2018;192:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sirignano M., Ghiassi H., D'Anna A., Lighty J.S. Temperature and oxygen effects on oxidation-induced fragmentation of soot particles. Combust Flame. 2016;171:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y., Chung S.H. Effect of strain rate on sooting limits in counterflow diffusion flames of gaseous hydrocarbon fuels: sooting temperature index and sooting sensitivity index. Combust Flame. 2014;161:1224–1234. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huijnen V., Evlampiev A.V., Somers L.M.T., Baert R.S.G., de Goey L.P.H. The effect of the strain rate on PAH/soot formation in laminar counterflow diffusion flames. Combust Sci Technol. 2010;182:103–123. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McEnally C.S., Pfefferle L.D., Atakan B., Kohse-Höinghaus K. Studies of aromatic hydrocarbon formation mechanisms in flames: progress towards closing the fuel gap. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2006;32:247–294. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou L., Dam N.J., Boot M.D., de Goey L.P.H. Investigation of the effect of molecular structure on sooting tendency in laminar diffusion flames at elevated pressure. Combust Flame. 2014;161:2669–2677. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruwe L., Moshammer K., Hansen N., Kohse-Höinghaus K. Influences of the molecular fuel structure on combustion reactions towards soot precursors in selected alkane and alkene flames. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2018;20:10780–10795. doi: 10.1039/c7cp07743b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang Q., Wang M., You X. Effects of fuel structure on structural characteristics of soot aggregates. Combust Flame. 2019;199:301–308. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das D.D., St. John P.C., McEnally C.S., Kim S., Pfefferle L.D. Measuring and predicting sooting tendencies of oxygenates, alkanes, alkenes, cycloalkanes, and aromatics on a unified scale. Combust Flame. 2018;190:349–364. [Google Scholar]

- 26.St. John P.C., Kairys P., Das D.D., McEnally C.S., Pfefferle L.D., Robichaud D.J. A quantitative model for the prediction of sooting tendency from molecular structure. Energy Fuel. 2017;31:9983–9990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang Q., Wang M., You X. Measurements of sooting limits in laminar premixed burner-stabilized stagnation ethylene, propane, and ethylene/toluene flames. Fuel. 2019;235:178–184. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanafi M.H.B.M., Nakamura H., Hasegawa S., Tezuka T., Maruta K. Effects of n-butanol addition on sooting tendency and formation of C1–C2 primary intermediates of n-heptane/air mixture in a micro flow reactor with a controlled temperature profile. Combust Sci Technol. 2018;190:2066–2081. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubey A.K., Tezuka T., Hasegawa S., Nakamura H., Maruta K. Study on sooting behavior of premixed C1–C4n-alkanes/air flames using a micro flow reactor with a controlled temperature profile. Combust Flame. 2016;174:100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson R.J., Botero M.L., Ness C.J., Morgan N.M., Kraft M. An improved methodology for determining threshold sooting indices from smoke point lamps. Fuel. 2013;111:120–130. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gómez A., Soriano J.A., Armas O. Evaluation of sooting tendency of different oxygenated and paraffinic fuels blended with diesel fuel. Fuel. 2016;184:536–543. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubio-Gomez G., Corral-Gomez L., Soriano J.A., Gomez A., Castillo-Garcia F.J. Vision based algorithm for automated determination of smoke point of diesel blends. Fuel. 2019;235:595–602. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McEnally C., Pfefferle L. Improved sooting tendency measurements for aromatic hydrocarbons and their implications for naphthalene formation pathways. Combust Flame. 2007;148:210–222. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McEnally C.S., Pfefferle L.D. Sooting tendencies of oxygenated hydrocarbons in laboratory-scale flames. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:2498–2503. doi: 10.1021/es103733q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao Z., Zou X., Huang Z., Zhu L. Predicting sooting tendencies of oxygenated hydrocarbon fuels with machine learning algorithms. Fuel. 2019;242:438–446. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kathrotia T., Riedel U. Predicting the soot emission tendency of real fuels – a relative assessment based on an empirical formula. Fuel. 2020;261 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon H., Shabnam S., van Duin A.C.T., Xuan Y. Numerical simulations of yield-based sooting tendencies of aromatic fuels using ReaxFF molecular dynamics. Fuel. 2020;262 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwon H., Jain A., McEnally C.S., Pfefferle L.D., Xuan Y. Numerical investigation of the pressure-dependence of yield sooting indices for n-alkane and aromatic species. Fuel. 2019;254 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrientos E.J., Lapuerta M., Boehman A.L. Group additivity in soot formation for the example of C-5 oxygenated hydrocarbon fuels. Combust Flame. 2013;160:1484–1498. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lemaire R., Lapalme D., Seers P. Analysis of the sooting propensity of C-4 and C-5 oxygenates: comparison of sooting indexes issued from laser-based experiments and group additivity approaches. Combust Flame. 2015;162:3140–3155. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang K.T., Hwang J.Y., Chung S.H., Lee W. Soot zone structure and sooting limit in diffusion flames: comparison of counterflow and co-flow flames. Combust Flame. 1997;109:266–281. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu L., Yan F., Zhou M., Wang Y., Chung S.H. Experimental and soot modeling studies of ethylene counterflow diffusion flames: non-monotonic influence of the oxidizer composition on soot formation. Combust Flame. 2018;197:304–318. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards* T.I.M. Cracking and deposition behavior of supercritical hydrocarbon aviation fuels. Combust Sci Technol. 2006;178:307–334. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Long L., Zhou W., Qiu Y., Lan Z. Coking and gas products behavior of supercritical n-decane over NiO nanoparticle/nanosheets modified HZSM-5. Energy. 2020;192 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jia Z., Wang Z., Cheng Z., Zhou W. Experimental and modeling study on pyrolysis of n-decane initiated by nitromethane. Combust Flame. 2016;165:246–258. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X., Song Q., Wu Y., Li X., Li T., Zeng X. Modelling and numerical simulation of n-heptane pyrolysis coking characteristics in a millimetre-sized tube reactor. Combust Flame. 2019;201:44–56. [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeWitt M.J., Edwards T., Shafer L., Brooks D., Striebich R., Bagley S.P., Wornat M.J. Effect of aviation fuel type on pyrolytic reactivity and deposition propensity under supercritical conditions. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2011;50:10434–10451. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiong G., Xie J., Chen L., Wang W., Zhou L. Sooting tendency of n-heptane/anisole blends in laminar counter-flow flames with oxygen enrichment. Fuel. 2019;255 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xue X., Hui X., Vannorsdall P., Singh P., Sung C.-J. The blending effect on the sooting tendencies of alternative/conventional jet fuel blends in non-premixed flames. Fuel. 2019;237:648–657. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y., Park S., Sarathy S.M., Chung S.H. A comparative study on the sooting tendencies of various 1-alkene fuels in counterflow diffusion flames. Combust Flame. 2018;192:71–85. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Z., Amin H.M.F., Liu P., Wang Y., Chung S.H., Roberts W.L. Effect of dimethyl ether (DME) addition on sooting limits in counterflow diffusion flames of ethylene at elevated pressures. Combust Flame. 2018;197:463–470. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joo P.H., Wang Y., Raj A., Chung S.H. Sooting limit in counterflow diffusion flames of ethylene/propane fuels and implication to threshold soot index. Proc Combust Inst. 2013;34:1803–1809. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dooley S., Won S.H., Chaos M., Heyne J., Ju Y., Dryer F.L., Kumar K., Sung C.-J., Wang H., Oehlschlaeger M.A., Santoro R.J., Litzinger T.A. A jet fuel surrogate formulated by real fuel properties. Combust Flame. 2010;157:2333–2339. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sarathy S.M., Farooq A., Kalghatgi G.T. Recent progress in gasoline surrogate fuels. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2018;65:67–108. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lemaire R., Faccinetto A., Therssen E., Ziskind M., Focsa C., Desgroux P. Experimental comparison of soot formation in turbulent flames of diesel and surrogate diesel fuels. Proc Comb Inst. 2009;32:737–744. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Das D.D., McEnally C.S., Pfefferle L.D. Sooting tendencies of unsaturated esters in nonpremixed flames. Combust Flame. 2015;162:1489–1497. [Google Scholar]

- 57.McEnally C.S., Pfefferle L.D. Sooting tendencies of nonvolatile aromatic hydrocarbons. Proc Combust Inst. 2009;32:673–679. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chelliah H.K., Law C.K., Ueda T., Smooke M.D., Williams F.A. An experimental and theoretical investigation of the dilution, pressure and flow-field effects on the extinction condition of methane-air-nitrogen diffusion flames. Symp (Int) Combust. 1991;23:503–511. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu L., Yan F., Wang Y., Chung S.H. Chemical effects of hydrogen addition on soot formation in counterflow diffusion flames: dependence on fuel type and oxidizer composition. Combust Flame. 2020;213:14–25. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan F., Xu L., Wang Y., Park S., Sarathy S.M., Chung S.H. On the opposing effects of methanol and ethanol addition on PAH and soot formation in ethylene counterflow diffusion flames. Combust Flame. 2019;202:228–242. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smyth K.C., Shaddix C.R. The elusive history of m~= 1.57–0.56i for the refractive index of soot. Combust Flame. 1996;107:314–320. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dasch C.J. One-dimensional tomography: a comparison of Abel, onion-peeling, and filtered backprojection methods. Appl Opt. 1992;31:1146–1152. doi: 10.1364/AO.31.001146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yan F., Zhou M., Xu L., Wang Y., Chung S.H. An experimental study on the spectral dependence of light extinction in sooting ethylene counterflow diffusion flames. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2019;100:259–270. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thomson K.A., Gülder Ö.L., Weckman E.J., Fraser R.A., Smallwood G.J., Snelling D.R. Soot concentration and temperature measurements in co-annular, nonpremixed CH4/air laminar flames at pressures up to 4 MPa. Combust Flame. 2005;140:222–232. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kruse S., Wick A., Medwell P., Attili A., Beeckmann J., Pitsch H. Experimental and numerical study of soot formation in counterflow diffusion flames of gasoline surrogate components. Combust Flame. 2019;210:159–171. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang J., Sun W., Wang G., Fan X., Lee Y.-Y., Law C.K. Understanding benzene formation pathways in pyrolysis of two C6H10 isomers: cyclohexene and 1,5-hexadiene. Proc Combust Inst. 2019;37:1091–1098. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hansen N., Kasper T., Yang B., Cool T.A., Li W., Westmoreland P.R. Fuel-structure dependence of benzene formation processes in premixed flames fueled by C6H12 isomers. Proc Combust Inst. 2011;33:585–592. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang H.R., Eddings E.G., Sarofim A.F., Westbrook C.K. Fuel dependence of benzene pathways. Proc Combust Inst. 2009;32:377–385. [Google Scholar]

- 69.CHEMKIN-PRO 15131, Reaction design, San Diego, CA, 2013.

- 70.Yoon S.S., Lee S.M., Chung S.H. Effect of mixing methane, ethane, propane, and propene on the synergistic effect of PAH and soot formation in ethylene-base counterflow diffusion flames. Proc Combust Inst. 2005;30:1417–1424. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Etz B.D., Fioroni G.M., Messerly R.A., Rahimi M.J., St. John P.C., Robichaud D.J. Elucidating the chemical pathways responsible for the sooting tendency of 1 and 2-phenylethanol. Proc Combust Inst. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.proci.2020.06.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim S., Fioroni G.M., Park J.-W., Robichaud D.J., Das D.D., John P.C.S. Experimental and theoretical insight into the soot tendencies of the methylcyclohexene isomers. Proc Combust Inst. 2019;37:1083–1090. [Google Scholar]

- 73.H. Wang, E. Dames, B. Sirjean, D. A. Sheen, R. Tango, A. Violi, J. Y. W. Lai, F. N. Egolfopoulos, D. F. Davidson, R. K. Hanson, C. T. Bowman, C. K. Law, W. Tsang, N. P. Cernansky, D. L. Miller, R. P. Lindstedt, A high-temperature chemical kinetic model of n-alkane (up to n-dodecane), cyclohexane, and methyl-, ethyl-, n-propyl and n-butyl-cyclohexane oxidation at high temperatures, JetSurF version 2.0, September 19, 2010 (http://web.stanford.edu/group/haiwanglab/JetSurF/JetSurF2.0/index.html).

- 74.Zhang K., Banyon C., Burke U., Kukkadapu G., Wagnon S.W., Mehl M. An experimental and kinetic modeling study of the oxidation of hexane isomers: developing consistent reaction rate rules for alkanes. Combust Flame. 2019;206:123–137. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tian Z., Tang C., Zhang Y., Zhang J., Huang Z. Shock tube and kinetic modeling study of cyclopentane and methylcyclopentane. Energy Fuel. 2015;29:428–441. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hwang J.Y., Chung S.H. Growth of soot particles in counterflow diffusion flames of ethylene. Combust Flame. 2001;125:752–762. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang W., Xu L., Yan J., Wang Y. Temperature dependence of the fuel mixing effect on soot precursor formation in ethylene-based diffusion flames. Fuel. 2020;267 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kholghy M.R., Weingarten J., Sediako A.D., Barba J., Lapuerta M., Thomson M.J. Structural effects of biodiesel on soot formation in a laminar coflow diffusion flame. Proc Combust Inst. 2017;36:1321–1328. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fan X., Wang G., Li Y., Wang Z., Yuan W., Zhao L. Experimental and kinetic modeling study of 1-hexene combustion at various pressures. Combust Flame. 2016;173:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ladommatos N., Rubenstein P., Bennett P. Some effects of molecular structure of single hydrocarbons on sooting tendency. Fuel. 1996;75:114–124. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li W., Law M.E., Westmoreland P.R., Kasper T., Hansen N., Kohse-Höinghaus K. Multiple benzene-formation paths in a fuel-rich cyclohexane flame. Combust Flame. 2011;158:2077–2089. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nick W.J.P., Marinov M., Westbrook C.K., Vincitore A.M., Castaldi M.J., Senkan S.M. Aromatic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon formation in a laminar premixed n-butane flame. Combust Flame. 1998;114:192–213. [Google Scholar]

- 83.McEnally C.S., Pfefferle L.D. An experimental study in non-premixed flames of hydrocarbon growth processes that involve five-membered carbon rings. Combust Sci Technol. 1998;131:323–344. [Google Scholar]