Abstract

In recent years, three-dimensional (3D) printing has markedly enhanced the functionality of bioreactors by offering the capability of manufacturing intricate architectures, which changes the way of conducting in vitro biomodeling and bioanalysis. As 3D-printing technologies become increasingly mature, the architecture of 3D-printed bioreactors can be tailored to specific applications using different printing approaches to create an optimal environment for bioreactions. Multiple functional components have been combined into a single bioreactor fabricated by 3D-printing, and this fully functional integrated bioreactor outperforms traditional methods. Notably, several 3D-printed bioreactors systems have demonstrated improved performance in tissue engineering and drug screening due to their 3D cell culture microenvironment with precise spatial control and biological compatibility. Moreover, many microbial bioreactors have also been proposed to address the problems concerning pathogen detection, biofouling, and diagnosis of infectious diseases. This review offers a reasonably comprehensive review of 3D-printed bioreactors for in vitro biological applications. We compare the functions of bioreactors fabricated by various 3D-printing modalities and highlight the benefit of 3D-printed bioreactors compared to traditional methods.

Keywords: Cell culture, Bacteria, Three-dimensional-printed chip, Three-dimensional-printed devices, Three-dimensional-printed bioreactors

1 Introduction

1.1 Bioreactor

Bioreactors are essential tools that not only guide and support the development of in vitro live tissues but also act as culture vessels to study the biological response of the tissues to physiologically relevant conditions[1]. In the context of this review, bioreactors refer to devices for cellular and biochemical assays. The design and configuration of a bioreactor should complement the requirements of biological systems. For example, bioreactors for the study of vascularization and cardiac regeneration are coupled with the pulsatile flow to augment cell differentiation and maturation[2]. Similarly, bioreactors for lung tissue models are often linked to airflow setup to imitate native lung functions[3]. In addition, various operational parameters related to the flexibility, design, and other characteristics of bioreactors greatly influence the biological performance of bioreactors[4]. In the past few years, modeling and applications of bioreactors have evolved in various fields of research. Due to their enormous versatility, bioreactors have been employed in many industries, including biological, biomedical, pharmaceutical, food, wastewater treatment, chemical, and fermentation[5]. This review focuses on biological applications in detail.

1.2 Three-dimensional (3D)-printed bioreactor

Conventional bioreactors grant operators the convenience of controlling the environment and experimental manipulation of two-dimensional tissue models[6]. However, their incompatibility with in vivo systems and their inability to reflect true cell traits and tissue morphology has necessitated 3D systems which exhibit better spatial distribution and structurally complex tissue architecture. Nevertheless, it is challenging to produce 3D bioreactors with complex geometry using conventional manufacturing methods[7].

Additive manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D-printing technology, has shown enormous potential in the fabrication of complex, low-cost, and custom-designed structures constructed by depositing a layer on top of earlier printed layers[5]. Over the past three decades, several 3D-printing strategies have been established with a focus on the fabrication of bioreactors of various shapes and sizes[8,9]. Through 3D-printing, specialized bioreactors can be engineered with high performance in terms of experimental throughput, liquid controllability, and stability[10]. 3D-printing not only grants freedom to optimize new bioreactor designs but also enhances cellular functionality and suitability of bioreactor for specific applications such as in vitro culturing and testing[11].

In view of this article, any 3D-printed culture apparatus, including chip, culture chamber, or filters that directly contact the cells, are considered as 3D-printed bioreactors. Moreover, various customized components and accessories of bioreactors such as culture tube holders, test parts, chamber inserts, and sensors fabricated with various 3D-printing modalities have been discussed. Several bioreactor models were designed to encourage the flow of culture medium for even distribution of nutrients throughout the culture vessel. The fluid flow in bioreactors could be manipulated at the micro-level by coupling bioreactors with microfluidic networks. The compartmentalized microfluidic devices with interconnected microchannels created cellular environments confined in a culture vessel that directed fluid flow through the cell culture[12,13]. In addition, these devices were shown to emulate physiological relevance by creating in vitro microenvironments on the same scale of cells. However, devices with challenging functionalities and dimensional specifications, such as channel height and aspect ratio, are difficult to achieve by conventional microfluidic techniques. Recent advancements have led to the development of 3D-microfluidics with intricate detailing, greater accuracy, and better resolution[14] using 3D-printing techniques.

1.3 Methods for fabricating 3D-printed bioreactors

Features of 3D-printed devices rely primarily on the chosen printing method. Some applications only 3D-printed the substrate in cell culture for in vitro analysis, whereas other applications embedded living cells into biocompatible printable materials (bio-inks)[15]. In this review, we primarily focus on the 3D-printed bioreactors for in vitro studies, not including the direct printing of cells. Various 3D-printing methods have been used to fabricate 3D structures and devices based on various printing techniques including selective laser melting (SLM), direct metal laser sintering (DMLS), fused deposition modeling (FDM), fused filament fabrication (FFF), inkjet, PolyJet, material jetting, stereolithography (SLA), digital light processing (DLP), micro-SLA (μSLA), and multiphoton lithography, each with their own advantages and disadvantages[16]. These 3D-printing processes are also used to fabricate bioreactors. However, none of these 3D-printing processes are ideal due to their specific limitations such as biocompatibility issues, difficulty in removing support materials, low printing resolution, poor dimensional accuracy, and rough surface texture[17-19]. Considerations for the choice of 3D-printing methods are shown in Tables 1 and 2. 3D-printing process can be selected based on the manufacturing capability of the printer and the type of material used by printer[20,21]. However, 3D-printing process can be also selected according to the given main design requirements of bioreactor, including functionality and visual appearances[9,18].

Table 1.

3D-printed bioreactors used in mammalian cell culture applications for assessing of cell viability, cell encapsulation, cell/tissue models, cell imaging, cell therapy, and organ-on-chip applications.

| Printing technique | Printer model | Possible reason for choice of printer | Material | 3D construct developed | Application | Cells used | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell viability | |||||||

| SLA | ILIOS 3D-printer | High precision, transparency | PEG-DA-250 resin | Transparent disks | Bioreactor for studying resin compatibility on cells | Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-K1), Primary hippocampal neurons | [18] |

| SLA | Form 1+3D-printer | High accuracy, high resolution | Photocurable liquid resin | Cylindrical test parts | Bioreactor accessory for studying resin compatibility on cells | Zebrafish | [17] |

| FDM | Dimension Elite 3D-printer | Affordable, easily available | ABS | ||||

| Material jetting | Objet350 Connex 3D-printer | Dimensional accuracy | Objet Vero Clear | Microfluidic chip | Bioreactor for resin compatibility on cells | Bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells | [31] |

| Cell encapsulation | |||||||

| SLA | Commercial 3D-printer (Proto Labs) | High accuracy | 3D Systems Accura® 60 | Pump-free perfusion cell culture device | Bioreactor for cell encapsulation | Oral squamous cell carcinoma tumor, Liver cells | [32] |

| Material jetting | Objet260 Connex3 3D-printer | Dimensional accuracy | VeroClear-RGD810 | ||||

| Cell/tissue models | |||||||

| SLA | Commercial 3D-printer (EnvisionTEC) | Structural robustness | Eshell 300 | Chamber and insert | Bioreactor accessory for tissue interactions | Human bone marrow stem cell | [33] |

| Testing of therapeutics | |||||||

| Material jetting | Objet Connex 350 3D-printer | Droplet precision | Objet Vero White Plus | Device | Bioreactor for cell toxicity+drug transport | Endothelial cells | [34] |

| Material jetting | Objet Connex 350 3D-printer | Geometrical precision | Objet VeroClear | Microfluidic chip | Bioreactor for drug metabolism | Red blood cells | [13] |

| Material extrusion | MakerBot Replicator 2X 3D-printer | Good mechanical properties | ABS | Cartridges | Accessory item for cell toxicity | Human embryonic kidney cells | [35] |

| Organ-on-a-chip | |||||||

| Material jetting | Objet30 Pro 3D-printer | Rigidity, transparency | Objet VeroClear | Modular chamber | Bioreactor for blood-brain-barrier environment | Endothelial cells, rat primary astrocytes | [36] |

| SLA | Cellbricks 3D-bioprinter | High resolution | Gelatin and polyethylene glycol | Liver lobule | Bioreactor for characterization of liver organoid under static conditions | Human hepatoma cell line, human stellate cells | [37] |

| SLA | Perfactory 3 Mini-Multi Lens 3D-printer | High resolution | PIC100 resin | 3D vessel | Bioreactor that mimics healthy and stenotic blood vessels | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells | [38] |

| Material extrusion | MakerBot Replicator 2 3D-printer | Affordable, geometrical precision | Polylactic acid | Input/output multiplexer | Bioreactor for endocrine tissue function | Endocrine cells | [39] |

| Material extrusion | ROSTOCK MAX V2 Desktop 3D-printer | Affordable, geometrical precision | Polymer | Molds | Bioreactor for bone metastasis | MC3T3-E1 cells | [40] |

| Material extrusion | Printrbot Simple Metal 3D-printer | Affordable, geometrical precision | Thermoplastic | Conformal device | Bioreactor for whole organ biomarker profiling | Microfluidic devices that interface with surface of whole organs | [41] |

| Material extrusion | Custom microextrusion-based 3D-printer | Micro-extrusion | Silicone, sodium polyacrylate hydrogel | ||||

| Cell observation | |||||||

| DLP | Micro Plus Hi-Re 3D-printer | High resolution | HTM140 | Microscopy chamber | Bioreactor accessory for multidimensional imaging | Human cell lines infected by membrane-GFP lentivirus, nuclear-tdTomato | [42] |

| DLP | EnvisionTEC Perfactory 3D-printer | High resolution | Eshell® 300 | Fluidic culture chamber | Bioreactor for cell imaging | hMSCs | [43] |

| SLA | 3D Systems Viper SLA system | Affordable, high accuracy, high resolution | WaterShed XC 11122 resin | Cell perfusion system (valves and pumps) | Bioreactor for cellular calcium imaging | CHO-K1 cells | [44] |

| SLA | PicoPlus 27 3D-printer | High accuracy, high resolution | Polypropylene/acrylnitril-butadien-styrol | Semiconductor-based biosensors | Bioreactor for cell growth and metabolism imaging, resin compatibility on cells | CHO-K1 cells | [45] |

3D: Three-dimensional, FDM: Fused deposition modeling, SLA: Stereolithography, DLP: Digital light processing, ABS: Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene

Table 2.

3D-printed devices for various microbial applications such as long-term microbial culture, pathogen detection, pathogen phenotype study, antibacterial assays, and 3D-printing of bacteria and biofilms.

| Printing technique | Printer model | Possible reason for choice of printer | Material | 3D construct developed | Application | Bacteria used | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term microbial culture | |||||||

| FDM | Fortus 250 mc 3D-printer | Good mechanical properties | ABS plus | Culture tube holder | Accessory item for bacterial growth monitoring | E. coli, S. aureus | [20] |

| SLA | Form 2 3D-printer | High resolution, high accuracy | STL 3D-printed resins | Culture millifluidic disks | Bioreactor for biotoxicity of 3D-printing resin on bacteria | P. putida | [48] |

| SLA | Form 1+ 3D-printer | Affordable, high resolution, high accuracy | Formlabs: ClearV2 and flexible, Shapeways: Elastoplastic, extreme detail, frosted acrylic, white strong, and flexible | Culture tubes | Accessory item for microbial liquid culture | E. coli | [49] |

| Material jetting | Connex350 3D-printer | High precision | Stratasys: MED610, VeroClear, TangoBlack, Tango Plus | ||||

| Pathogen detection | |||||||

| Material extrusion | Profi3Dmaker 3D-printer | Affordable, optimal printing quality | ABS | Chip | Bioreactor for colorimetric detection | S. aureus, E. coli, S. typhimurium, L. rhamnosus, Methicillin-resistant S. aureus | [50] |

| Material extrusion | Easy 3D Maker 3D-printer | Affordable, geometrical precision | Polylactide | Bead-based microfluidic chip | Bioreactor for electrochemical detection | Influenza virus | [51] |

| Material extrusion | UPBOX+ 3D-printer | Affordable, optimum resolution | ABS | Smartphone platform | Accessory item for detection of viable algae in fresh and marine water | C. reinhardtii, M. aeruginosa, Amphiprora sp., and C. closterium | [52] |

| Material jetting | 3D Systems ProJet 3000UHD 3D-printer | Ultra-high resolution | VisiJet EX200 polymer | Finger actuated microfluidic device | Bioreactor for colorimetric detection | E. coli | [53] |

| Material jetting | Stratasys Objet24 3D-printer | High precision | Vero White Plus | Microfluidic chip | Bioreactor for colorimetric detection | E coli | [54] |

| Material jetting | Objet30 Pro 3D-printer | Accuracy, versatility | Vero™ Black material | Micro-millifluidic bioreactor | Bioreactor for microalgal culture | D. tertiolecta | [55] |

| SLA | 3D Systems Viper SLA system | High resolution, high accuracy | DSM Somos WaterShed XC 11122 | Cylindrical microchannel device | Bioreactor for detection by ATP bioluminescence assay | Salmonella | [56] |

| SLA | 3D Systems Viper SLA system | High resolution, high accuracy | DSM Somos WaterShed XC 11122 resin | Helical microchannel device | Bioreactor for detection and separation by ATP bioluminescence assay | E. coli | [7] |

| DLP | Carima DP 110 3D-printer | Dimensional precision, good reproducibility | Acrylic resin | Trapezoidal-shaped concentration chamber | Bioreactor for detection by ATP luminescence assay | E. coli | [57] |

| DLP | Carima IM-96 3D-printer | Dimensional precision | Photocurable resin | Millifluidic device | Bioreactor for detection in blood by PCR and qPCR | E. coli and S. aureus | [8] |

| Ink jetting | Fuji Dimatix printer | Controllability, efficiency | Polyethylene terephthalate | Microfluidic device | Bioreactor for electrochemical detection | Salmonella | [58] |

| Ink jetting | Epson ET-2550 EcoTank® printer | Low-cost | Conductive inks based on silver nanoparticles and transparent and flexible polyethylene terephthalate sheets | Interdigitated electrode sensor | Accessory item for electrochemical detection of bacteriophages contamination | L. lactis subsp. Lactis and its phage | [25] |

| FDM | Prusa MovtecH model open-source 3D-printer | Rapid fabrication | ABS | T-junction device | Bioreactor for bacterial detection | E. coli | [59] |

| Pathogen phenotype analysis | |||||||

| Material jetting | ProJet™ MJP 2500 Plus 3D-printer | High resolution | VisiJet M2 RCL, 3D Systems | Microfluidic chip | Bioreactor for live/dead bacterial cell differentiation with propidium monoazide pretreatment | E. coli | [60] |

| SLA | Form 2 3D-printer | Affordable, high resolution | Resin | Incubation/diffusion chamber | Bioreactor for pathogen phenotype analysis in soil matrices | B. cereus, E. coli | [61] |

| Wastewater treatment | |||||||

| SLA | 028 J Plus 3D-printer | High resolution | Urethane-acrylate based resin with 20% silica-alumina powder | Magnetic cylindrical (planar and spiral) microrobots | Bioreactor for antibacterial activity, biocompatibility | S. aureus | [26] |

| SLA | Form 1 3D-printer | Affordable, high resolution, high accuracy | Formlabs Clear FLGPCL02 | 40-mL anaerobic digester | Bioreactor for wastewater treatment | Microbial inoculum | [62] |

| SLS | FARSOON 251 3D-printer | Good mechanical properties | Nylon FS3200PA | Bio-carrier sphere | Biofilm reactor for wastewater treatment | Biofilm | [21] |

| Material jetting | Objet30 3D-printer | High resolution | Acrylate-based monomer resin | Gyroid media carrier | Biofilm reactor for wastewater treatment | Biofilm of nitrifying bacteria | [63] |

3D: Three-dimensional, FDM: Fused deposition modeling, E. coli: Escherichia coli, S. aureus: Staphylococcus aureus, S. typhimurium: Salmonella typhimurium, P. putida: Pseudomonas putida, L. rhamnosus: Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Methicillin-resistant S. aureus: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, C. reinhardtii: Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, M. aeruginosa: Microcystis aeruginosa, D. tertiolecta: Dunaliella tertiolecta, C. closterium: Cylindrotheca closterium, L. lactis: Lactococcus lactis, B. cereus: Bacillus cereus, ABS: Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene

Different laser sintering approaches such as SLM and DMLS are highly reproducible AM techniques used to fabricate porous and 3D uniform metal structures with distinct cavities, and precisely control geometric parameters down to several hundred microns using laser power as low as 90 W[22,23]. Extrusion printing and its common variants such as FDM and FFF extrude molten polymer in a layer-by-layer manner to construct 3D objects[17,24]. This 3D-printing technique is cost-effective and could be easily adopted as a viable manufacturing option to create 3D constructs with high resolution, structural integrity, and transparency. Jetting-based methods, including inkjet, PolyJet, and material jetting deposit fluidic materials in a controlled fashion through a nozzle onto a 3D platform and are used to create highly complex constructs[25]. These direct cell printing techniques will not be discussed in this review. Another widely used 3D-printed method is the vat photopolymerization, including SLA and DLP, which prints by curing photosensitive resins with ultraviolet light[17,26]. SLA uses a laser beam that scans line-by-line to cure the photosensitive resin, whereas DLP uses a digital light projector to cure each layer of photoreactive resin in one go. Compared to DLP, SLA-based printers offer a higher spatial resolution, resulting in structures with dimensions <10 μm. μSLA-based systems that utilize two-photon optics further improve the resolution to submicrons[17]. The resulting ultrafine features may influence the mechanistic properties of cells in tissues. Nevertheless, resins used for SLA printers often contain methacrylate and/or acrylate monomers that have a reputation to be cytotoxic[17].

2 3D-printed bioreactor for biological applications

3D-printing is a rapidly evolving technology that provides an opportunity to fabricate complex 3D structures for biological applications[5,27]. It is an important tool for translational research that focuses on the in vitro biology and disease models in bioreactors. The increasing accessibility to 3D-printing has spurred substantial efforts toward many creative developments of 3D-printed bioreactors for the cultivation of mammalian as well as microbial cells. Various bioreactors have been fabricated with 3D-printing to study the response of these cells to the smallest details of their local environments such as substrate geometric arrangement, chemistry, and mechanics[28,29].

Much of our understanding of fundamental cellular mechanisms is garnered from the aberrant interactions of cells on 2D substrates. As we move toward more-compliant microenvironment, it is vital to demystify exactly what factors are operative in 3D systems rather than simply considering a dimensionality factor at play[30]. The increased capabilities of 3D-printers have resulted in well-architecture constructs with fine features and application-specific geometries. The key challenge here lies in achieving the geometry that provides the correct degree of biomimicry, mechanical and chemical cues needed for sufficient cell-cell signaling, cell development, and gene expression. Indeed, surface parameters such as porosity, roughness, and curvature are tunable according to experimental needs, and their effect on the collective cell behavior including adhesion, growth, alignment, proliferation, and differentiation has been demonstrated as well. Ideally, the role of 3D-printing is to provide cells a suitable environment supporting their transition into functional tissue in vitro. With 3D-printing, we are able to fabricate bioreactors of different sizes and shapes and introduce cells into the bioreactors post-printing for in vitro testing. Overall, this article aims to cover 3D-printed bioreactors for the in vitro study of both mammalian and bacterial cell culture.

2.1 3D-printed bioreactor for mammalian cell culture

3D-printed bioreactors used in mammalian cell culture applications for assessment of cell viability, cell encapsulation, cell/tissue models, cell imaging, testing of therapeutics, and organ-on-chip applications are discussed below and summarized in Table 1.

2.1.1 Cell viability in 3D-printed bioreactors

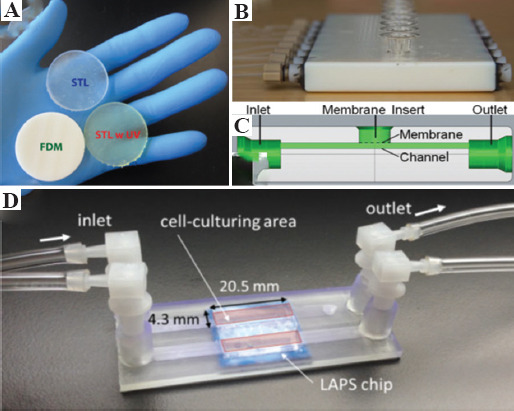

Bioreactors are an indispensable tool for maintaining cellular microenvironment to promote cell viability, growth, and proliferation. The biocompatibility of cells with the materials used for 3D-printing also affects cell viability and survivability. Biocompatibility could be achieved with post-printing modification and has already been reviewed earlier[46]. The compatibility of zebrafish larvae on parts 3D-printed by FDM (using acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, [ABS]) and SLA (using photocurable liquid resin) (Figure 1A) indicated that materials used for FDM were less toxic compared to SLA evidenced by significantly lower rates of malformations. Following the UV treatment of SLA parts, the toxicity was significantly reduced but not completely eliminated[17]. In contrast, a concurrent study indicated the potential of transparent PEG-DA-250 resin disks (printed by SLA) for supporting the long-term culture of adherent CHO-K1 cells and primary hippocampal neurons[18]. Elsewhere, bovine endothelial cells were immobilized on a 3D transparent microfluidic chip made from photocurable resins by material jetting. Owing to unknown resin properties, the internal channels of the chip were coated with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and polystyrene, respectively. Cell adherence and survival were favorable to PDMS, in comparison to polystyrene-coated, polished, and untreated samples[31].

Figure 1.

(A) Resin disks three-dimensional (3D)-printed by fused deposition modeling, stereolithography (SLA), and SLA w UV used for testing resin toxicity on zebrafish (40 mm diameter and 4 mm height)[17]. (B) 3D-printed device design showing adapters for syringe-based pumps, channels, membrane insertion port, and outlets. (C) The side view schematic of the 3D-printed device to understand the channel and fluid to flow under the membrane. The membrane is manually inserted into the port on top of the device. Finally, there is an outlet to allow fluid to leave the device[34]. (D) Potentiometric sensor-based biosensor chip showing inlet, outlet, and sensing area (20.5 mm × 4.3 mm) with attached microfluidic channels[45].

2.1.2 3D-printed bioreactor for cell encapsulation

A pump-free perfusion device was fabricated by SLA (3D Systems Accura 60) and material jetting (VeroClear-RGD810) for immobilizing multicellular spheroids and maintaining their viability. Even though SLA resulted in cell-immobilizing microstructures with smoother surfaces, good spheroid functionality, and prolonged viability compared to PolyJet printing, the inferior optical properties restricted sample visualization by microscopy[32]. Despite a conducive capsule housing for cell culture, it remains a challenging task to entrap certain cell models with biocompatible substrates and mandates optical transparency of capsules due to their suitability for cell imaging.

2.1.3 3D-printed bioreactor for cell/tissue models

In addition to providing a complex yet controlled ambient for cell viability and cell encapsulation through spatial and temporal control of cell growth, the increasing versatility of 3D-printing also enables the development of tissue culture constructs that mimic specific biological functions and capture cell-tissue interactions inside the culture system. For example, the pathogenesis associated with a tissue can be studied. A 3D-printed multichambered bioreactor fabricated with non-cytotoxic Eshell 300 resin using SLA was fitted into a microfluidic base, creating tissue-specific environments for the study of interactions between chondral and osseous tissues during osteochondral differentiation[33]. This system provided opportunities to investigate the tissue physiology and the role of each tissue in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis.

2.1.4 3D-printed bioreactor for testing of therapeutics

3D-printed bioreactors are also useful in the clinical translation and commercialization of standardized cell-based products for cell-based therapies and drug-testing. A reusable material jetted (Objet Connex 350) fluidic device incorporated a porous polycarbonate membrane not only enabled molecular transport and drug migration through the membrane (Figure 1B and C) but also indicated drug susceptibility of mammalian cells[34]. Moreover, collecting analytes while simultaneously measuring the release stimulus was also possible with this 3D-printed bioreactor[13]. Electrodes and other additional functionalities such as membrane inserts and fluidic interconnects were integrated to ensure signal detection and flow control. A compact ready-to-use material extruded (MakerBot Replicator 2X) cartridge containing assay reagents was integrated with genetically engineered sentinel cells and interfaced with a custom-developed smartphone Tox-App for rapid quantification of cellular toxicity[35].

2.1.5 3D-printed bioreactor for organ-on-chip applications

An organ-on-a-chip device fabricated by 3D-printing aims to assemble organ models in 3D specific architecture on a microfluidic chip. By virtue of precise geometrical features attained by 3D-printing coupled with controlled flow dynamics and imaging compatibility of microfluidics, a continuous perfusion model had been developed to imitate the blood-brain barrier environment[36]. This setup consisted of a porous membrane that allowed coculture of different cell types across the membrane and a 3D-printed cell insert module that accommodated cell monolayers which formed a fully functional closed-loop perfusion model. This 3D-printed bioreactor was able to overcome the limitations faced by static culture models and demonstrated the synergy between microfluidics and 3D-printing[47]. Similarly, a 3D bone-on-a-chip device used coculture strategies to study disease mechanisms of the metastasis of breast cancer cells to bone marrow[40]. In the study, transparent PDMS chambers for cell growth casted from a 3D-printed mold (Rostock MAX V2 Desktop printer) were separated from the media reservoir by a membrane. 3D-printing of this geometrical design enabled frequent monitoring of interactions between cancer cells and the bone matrix in vitro and eliminated the need to take bone metastasis samples from patients.

Another study demonstrated the use of a perfusion-type liver organoid model using a sinusoidal liver lobule on a chip 3D-printed by SLA (Cellbricks bioprinter) with polyethylene glycol and gelatin containing bio-inks[37]. Cells cultured within the liver organoid model revealed high-yield protein expression compared to monolayer cultures. This in vitro model in 3D-printed bioreactor ensured hepatocyte functionality and could be modified to accommodate nutritional supply for larger tissue models to explore the mechanistic properties. The organ-on-a-chip systems could also be personalized by integrating additional systems to emulate the complexities of an organ. To design a 3D arterial thrombosis model, anatomical models were obtained from imaging scans and converted into a printable 3D model. The molds for chips with miniaturized healthy and stenotic vasculatures were then developed using a Perfactory 3 SLA 3D-printer with PIC100 resin. The vascular structures incorporated on-chip successfully mimicked vessel environments, showing human blood flow at physiologically relevant conditions and with artificially induced thrombosis[38]. Another system non-invasively interfaced a 3D-printed microfluidic device with a porcine kidney model to isolate and profile biomarkers from whole organs in real-time. From the cortex of the kidney, relevant metabolic and pathophysiological biomarkers were transported to the microfluidic device by virtue of the fluid flow in the microchannel. Hence, the 3D organ-on-a-chip could perhaps overcome the drawbacks of whole organ structures[41]. For a complex organ model, a multi-channel perfusion-type chamber was developed to assess endocrine secretions, due to their multiple inlet and outlet needs[39]. The device warranted precise control of nutrient inputs, hormone outputs, and permitted observation by fluorescence imaging.

2.1.6 3D-printed bioreactor to facilitate cell observation

The visualization of real-time cellular response to a 3D culture environment through imaging facilitates the monitoring of specific cellular processes. Another research group proposed a multidimensional observation chamber (the UniveSlide) with an SLA 3D-printed frame for medium/high throughput long-term imaging in controlled culture environments, which was also compatible with different microscopy techniques[42]. Moreover, this all-in-one device may be suitable for automatized multi-position imaging of thick samples. The use of agarose gel with imprinted microwells as a base support frame was a convenient addition for trapping cells and subsequent 3D viewing. A 3D-printed fluidic culture chamber was used to dynamically culture hMSCs, study the mechanical behavior of the cells in a controlled microenvironment, and visualize cells within 3D-printed constructs without sectioning using imaging techniques such as confocal or fluorescence laminar optical tomography[43]. Bioreactor accessories such as 3D-printed valves and pumps used for cell culture were also fabricated with SLA (3D Systems Viper system) using WaterShed XC 11122 resin. This study demonstrated controlled adenosine triphosphate (ATP) stimulation of live cells in an incubation chamber for observation of Ca2+ response[44]. Recently, a semiconductor-based biosensor chip was fabricated using Asiga Pico Plus 27 by DLP (Figure 1D) to facilitate the observation of cell metabolism on the microfluidics-based light-addressable potentiometric sensor chip[45].

2.2 3D-printed bioreactor for microbial cell culture applications

In the recent past, several studies have attempted to unravel the gaps of our understanding of bacteria survival mechanisms in complex microenvironments. AM offers an opportunity to reproduce the geometry of actual environments. The focal point of this section revolves around the use of 3D-printed bioreactors for various microbial applications such as long-term microbial culture, pathogen detection, pathogen phenotypic study, and antibacterial assays, which are summarized in Table 2.

2.2.1 3D-printed bioreactor for long-term microbial culture

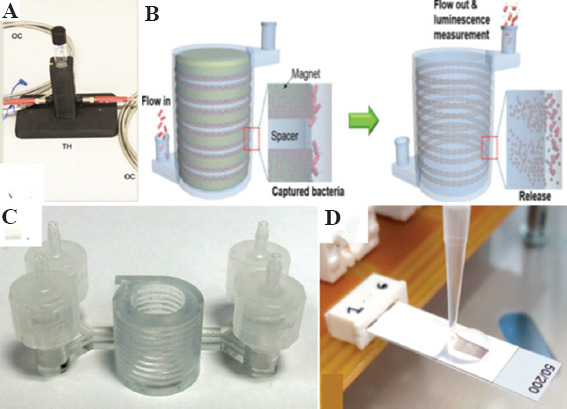

Tracking the bacterial cell growth for a prolonged period provides crucial information on cell survival and proliferation conditions in addition to their nutrition and energetic physiology[64]. A number of bioreactors were built by 3D-printing to assist in monitoring the growth of bacteria in liquid cultures. A customized FDM-printed culture tube holder (Figure 2A) was interfaced with a mini-spectrophotometer connected to a light source through optical fibers to monitor bacteria growth in liquid culture through turbidimetric measurement[20]. Elsewhere, 3D-printed bioreactors built by SLA and material jetting were used for long-term culture that mimicked the shape and dimensions of a standard commercial polystyrene tube[49]. Ten different 3D-printable resin materials were tested, of which only MED610 (ISO-certified biocompatible), VeroClear, and Frosted Acrylic exhibited no significant bacteria growth inhibition. Other materials were unsuitable because of rapid media evaporation (elastoplastic), sticky residue formation (Extreme Detail), deposition of particles inside the bioreactor after storage (White Strong and Flexible), physical instability (TangoBlack), and drastically reduced growth rates of bacteria cells (ClearV2, Flexible and Tango Plus). In a later study, an SLA-printed bioreactor in the form of a disk (Formlabs) was tested for biotoxicity effects of resins on bacteria and suggested a dose-response relationship to resin[48].

Figure 2.

(A) Three-dimensional (3D)-printed culture tube holder for monitoring the bacterial growth of liquid microbial cultures (OC: Optical cable; TH: Tube holder)[49]. (B) 3D-printed magnet-spacer assembly showing bacterial separation by 3D immunomagnetic flow assay[58]. (C) 3D-printed vertically designed cylindrical chamber was developed for bioluminescent bacterial detection[7]. (D) Inkjet-printed interdigitated electrode sensor for phage detection[26].

2.2.2 3D-printed bioreactor for pathogen detection

Undesired pathogen contamination in water, food, and blood poses a great public health threat. Rapid detection and separation of bacterial pathogens are therefore necessary in the field of food industry, clinical diagnostics, and environment quality control to ensure safety[65]. To monitor and quantify the presence of microbes, the design and fabrication of new 3D-printed diagnostic devices have been the focus of these areas. Considering the importance of an appropriate pathogen detection system, several studies had combined the 3D-printed bioreactors with detection methods such as calorimetry, bioluminescence, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), electrochemical, and contactless conductivity for bacteria sensing. Colorimetric detection is a rapid, easy-to-operate technique capable of simple visual detection. A material extrusion-based 3D-printed chip using ABS was made from Profi3Dmaker for bacteria culture, DNA isolation, and colorimetric detection of mecA genes, specific to the presence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The entire chip was placed in a thermostatic box for maintaining a homogenous magnetic field and facilitating non-crosslinking aggregation of nanoparticle probes with bacterial DNA for in vitro diagnostic applications[50]. Another study used a manually actuated miniature 3D-printed device fabricated using VisiJet EX200 polymer by material jetting for rapid on-site multiplexed bacterial detection using calorimetric measurement[53]. The finger-actuated pumping membrane seated on the pumping chamber was connected to individual enrichment/detection chambers through serpentine channels for bacteria detection in drinking water. Upon depressing and releasing the membrane, a vacuum pressure filled in each chamber and sucked in the sample. The lowest detection limit of 1e6 colony forming units (CFU)/mL was observed in approximately 6 hours. Furthermore, these pathogen detection devices were also connected to accessories for colorimetric readout, which would improve the limit of detection[54].

Some groups have resorted to combined ATP bioluminescence and magnetic particle-based immunomagnetic separation for bacteria sensing. This is a more rapid and efficient approach for increasing the sensitivity and specificity of pathogen identification. A 3D-printed bioreactor with cylindrical hollow microchannel and high-capacity efficient magnetic O-shaped separator (HEMOS) was designed for Salmonella detection in large-volume samples (Figure 2B). The magnet-spacer feature in the central area of HEMOS maximized the magnetic field, thereby allowing ultra-rapid capture of 10 CFU/mL of nanocluster-immobilized bacteria within 3 min[56]. Similarly, a 3D-printed bioreactor with helical chambers (Figure 2C) was developed for bioluminescent Escherichia coli (E. coli) detection in milk[7]. The device enabled sheath inlet flow for improved size-dependent separation of bacteria-nanocluster complexes in the helical microchannel. A number of studies employed 3D-printed millifluidic platforms to process samples larger than 1 mL. At sub-millimeter scale, recyclable, 3D-printed trapezoidal preconcentration chamber built by DLP (acrylic resin) was used to isolate E. coli in blood samples[57]. Another 3D-printed millifluidic device preconcentrated bacterial DNA by sequential isolation using magnetic silica beads was also developed for improved pathogen detection in blood. This method extracted bacterial DNA in 10 mL of buffer and 10% blood within 30 min and detected as low as 1 CFU bacterial using either PCR or quantitative PCR[8].

Electrochemical detection has also been accepted as a powerful tool for bacterial and viral detection in 3D-printed biomarkers by identifying disease-related biomarkers and environmental hazards. A pump-free bioreactor used for electrochemical detection of Salmonella consisted of two flexible polyethylene terephthalate layers with sintered inkjet-printed electrodes directly bonded to the channel-containing layer, forming a sealed microfluidic device[58]. This high throughput device accommodated immunomagnetic bacterial separation. Similarly, a material-extruded bead-based microfluidic chip with a three-electrode setup was used for the detection of influenza hemagglutinin[51]. Elsewhere, a prototype system with real-time impedance measurements was used to detect phage infection of cultured Lactococcus lactis[25]. The two standard microbiological testing methods used for comparison were based on plaque assay and turbidity measurements. Only the inkjet-based biosensor system showed a greater sensitivity to phage infection with a response within the first 3 h of phage inoculation. Another study described a T-junction microfluidic device with integrated sensing electrodes developed by FDM (using ABS) for label-free counting of E. coli cells incorporated in spherical oil droplets. Cells were counted using a single-step contactless conductivity system and quantified by plate counting method. This approach offered noticeable advantages as a single-step method with minimal incubation time before detection[59]. Studies have also explored the use of 3D-printed bioreactors for the culture of microbes other than bacteria, such as algae. A material jetted milli-microfluidic device (Vero™ Black material) with growth chambers, microchannels, and semi-integrated optical detection system was used for algal culture[55]. Even though the growth was unsuccessful due to poor microalgal retention resulting from photopolymer incompatibility with cells, other metrics observed during the culture offered a mechanical perspective that indicated the 3D-printed architecture posed promising advantages in comparison to other complex microfabrication processes. Another group developed a 3D-printed smartphone platform integrated with an optoelectrowetting-operated microfluidic device for on-site detection of viable algae cells[52]. The collected data were wirelessly transmitted to a central host for real-time monitoring of water quality with reduced analysis time. Given its sensitivity, this chip allowed sample preparation methods such as droplet immobilization and mixing, target cell counting, and fluorescent detection.

2.2.3 3D-printed bioreactor for pathogen phenotypic analysis

Profiling pathogen phenotypes is important in decoding the virulence and interaction of pathogen with its surroundings. A propidium monoazide (PMA) pretreatment was carried out in a 3D-printed bioreactor to efficiently discriminate live waterborne bacterial pathogens in natural pond water samples[60]. The material jetted bioreactor was designed with an inlet, splitter, and mixers for proper sample-PMA mixing followed by incubation in serpentine channels containing herringbone structures for alternating dark and light incubation. The results obtained from this 3D-printed bioreactor suggested the need for species-specific optimization of pretreatment performance. Elsewhere, an SLA-printed incubation/diffusion chamber was designed for culturing bacteria from soil samples to study their interaction dynamics. The chamber facilitated diffusion of soil components with target cells and also allowed single-cell and ensemble bacterial phenotypic analyses[61].

2.2.4 3D-printed bioreactor for wastewater treatment

Several 3D-printed bioreactors have demonstrated great potential in water treatment applications that were difficult to be achieved by conventional wastewater treatment systems. Cylindrical microrobots printed by SLA conveyed excellent water purification capability and great biocompatibility with mammalian cells[26]. Other intricate 3D-printed bioreactor designs, including fullerene-shaped bio-carriers[21] and gyroid-shaped carrier[63], have been shown to stimulate microbial assemblages for improved organic matter removal and better performance of biofilm reactors. Other studies employed SLA-printed miniature anaerobic digester reactors as a process screening tool for sustainable treatment of wastewater and biowaste[62].

3 Conclusions and future directions

In recent years, significant advances have been made in 3D-printed bioreactor technologies. Bioreactors have been tailored to easy online monitoring and automated bioprocesses, thereby closing the gap between conventional bioreactors and their miniature 3D-printed counterparts. However, in addition to their basic functions, other design aspects, such as flexible operation and process optimization, should be taken into account, especially for devices used to study complex physiological phenomena. It is noteworthy to mention that there has been limited clinical translation of 3D-printed bioreactors. This could be attributed to the lack of optimized protocols that are fine-tuned to respective 3D-printing methods and materials. The reproducibility of certain 3D-printing processes is suboptimal.

At present, 3D-printing research for in vitro biological applications focuses mostly on relatively simple systems that only incorporate a limited number of cells and cell types. Future studies should aim to attend to relatively complex tissues and organs. Moreover, several concerns such as 3D-printing compatible design, removal of support structures, the choice of appropriate cell lines, better cocultivation concepts, establishment of optimal conditions, and protocol standardization remain to be resolved and should be the focus of future research. With advances in various aspects of 3D-printing, one would be able to design and manufacture customized bioreactors with tailored functionalities using 3D-printing in laboratory settings, which would significantly drive future biomedical research by offering on-demand in vitro testing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors are thankful for the support by HP-NTU Digital Manufacturing Corporate Lab, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors. This research was conducted in collaboration with HP Inc. and supported/partially supported by the Singapore Government through the Industry Alignment Fund-Industry Collaboration Projects Grant.

References

- 1.Wang D, Liu W, Han B, et al. The Bioreactor:A Powerful Tool for Large-scale Culture of Animal Cells. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2005;6:397–403. doi: 10.2174/138920105774370580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Govoni M, Lotti F, Biagiotti L, et al. An Innovative Stand-alone Bioreactor for the Highly Reproducible Transfer of Cyclic Mechanical Stretch to Stem Cells Cultured in a 3D Scaffold. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2014;8:787–93. doi: 10.1002/term.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimizu T, Sekine H, Yamato M, et al. Cell Sheet-based Myocardial Tissue Engineering:New Hope for Damaged Heart Rescue. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:2807–14. doi: 10.2174/138161209788923822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozturk SS. Engineering Challenges in High Density Cell Culture Systems. Cytotechnology. 1996;22:3–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00353919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capel AJ, Rimington RP, Lewis MP, et al. 3D Printing for Chemical, Pharmaceutical and Biological Applications. Nat Rev Chem. 2018;2:422–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hjertager BH, Morud K. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation of Bioreactors. J Mod Identif Control. 1995;16:177–91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee W, Kwon D, Choi W, et al. 3D-printed Microfluidic Device for the Detection of Pathogenic Bacteria Using Size-based Separation in Helical Channel with Trapezoid Cross-section. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7717. doi: 10.1038/srep07717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim Y, Lee J, Park S. A 3D-printed Millifluidic Platform Enabling Bacterial Preconcentration and DNA Purification for Molecular Detection of Pathogens in Blood. Micromachines. 2018;9:472. doi: 10.3390/mi9090472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alessandri K, Feyeux M, Gurchenkov B, et al. A 3D Printed Microfluidic Device for Production of Functionalized Hydrogel Microcapsules for Culture and Differentiation of Human Neuronal Stem Cells (hNSC) Lab on a Chip. 2016;16:1593–604. doi: 10.1039/c6lc00133e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bancroft GN, Sikavitsas VI, Mikos AG. Design of a Flow Perfusion Bioreactor System for Bone Tissue-engineering Applications. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:549–54. doi: 10.1089/107632703322066723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards DJ, Tan Y, Jia J, et al. 3D Printing for Tissue Engineering. Israel J Chem. 2013;53:805–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasirayi G, Auger V, M Scott S, et al. Microfluidic Bioreactors for Cell Culturing:A Review. Micro Nanosyst. 2011;3:137–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erkal JL, Selimovic A, Gross BC, et al. 3D Printed Microfluidic Devices with Integrated Versatile and Reusable Electrodes. Lab Chip. 2014;14:2023–32. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00171k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rupal BS, Garcia EA, Ayranci C, et al. 3D Printed 3D-Microfluidics:Recent Developments and Design Challenges. J Integr Des Proc Sci. 2018;22:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ball O, Nguyen BN, Placone JK, et al. 3D Printed Vascular Networks Enhance Viability in High-volume Perfusion Bioreactor. Ann Biomed Eng. 2016;44:3435–45. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1662-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ngo TD, Kashani A, Imbalzano G, et al. Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing):A Review of Materials, Methods, Applications and Challenges. Compos B Eng. 2018;143:172–96. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oskui SM, Diamante G, Liao C, et al. Assessing and Reducing the Toxicity of 3D-Printed Parts. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2015;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urrios A, Parra-Cabrera C, Bhattacharjee N, et al. 3D-printing of Transparent Bio-microfluidic Devices in PEG-DA. Lab Chip. 2016;16:2287–94. doi: 10.1039/c6lc00153j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiménez M, Romero L, Domínguez IA, et al. Additive Manufacturing Technologies:An Overview about 3D Printing Methods and Future Prospects. Complexity 2019. 20192019:9656938. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maia MR, Marques S, Cabrita AR, et al. Simple and Versatile Turbidimetric Monitoring of Bacterial Growth in Liquid Cultures Using a Customized 3D Printed Culture Tube Holder and a Miniaturized Spectrophotometer:Application to Facultative and Strictly Anaerobic Bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1381. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong Y, Fan SQ, Shen Y, et al. A Novel bio-carrier Fabricated Using 3D Printing Technique for Wastewater Treatment. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12400. doi: 10.1038/srep12400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qing Y, Li K, Li D, et al. Antibacterial Effects of Silver Incorporated Zeolite Coatings on 3D Printed Porous Stainless Steels. Mater Sci Eng C. 2019;108:110430. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bassous NJ, Jones CL, Webster TJ. 3-D Printed Ti-6Al-4V Scaffolds for Supporting Osteoblast and Restricting Bacterial Functions without Using Drugs:Predictive Equations and Experiments. Acta Biomater. 2019;96:662–73. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan AJ, San Jose LH, Jamieson WD, et al. Simple and Versatile 3D Printed Microfluidics Using Fused Filament Fabrication. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosati G, Cunego A, Fracchetti F, et al. Inkjet Printed Interdigitated Biosensor for Easy and Rapid Detection of Bacteriophage Contamination:A Preliminary Study for Milk Processing Control Applications. Chemosensors. 2019;7:8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernasconi R, Carrara E, Hoop M, et al. Magnetically Navigable 3D Printed Multifunctional Microdevices for Environmental Applications. Addi Manufact. 2019;28:127–35. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerman MJ, Lembong J, Gillen G, et al. 3D Printing in Cell Culture Systems and Medical Applications. Appl Phys Rev. 2018;5:041109. doi: 10.1063/1.5046087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, et al. Geometric Control of Cell Life and Death. Science. 1997;276:1425–8. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang Y. Tissue Cells Feel and Respond to the Stiffness of their Substrate. Science. 2005;310:1139–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker BM, Chen CS. Deconstructing the Third Dimension how 3D Culture Microenvironments Alter Cellular Cues. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3015–24. doi: 10.1242/jcs.079509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gross BC, Anderson KB, Meisel JE, et al. Polymer Coatings in 3D-printed Fluidic Device Channels for Improved Cellular Adherence Prior to Electrical Lysis. Anal Chem. 2015;87:6335–41. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b01202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ong LJ, Islam A, DasGupta R, et al. A 3D Printed Microfluidic Perfusion Device for Multicellular Spheroid Cultures. Biofabrication. 2017;9:045005. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/aa8858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin H, Lozito TP, Alexander PG, et al. Stem Cell-based Microphysiological Osteochondral System to Model Tissue Response to Interleukin-1? Mol Pharm. 2014;11:2203–12. doi: 10.1021/mp500136b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson KB, Lockwood SY, Martin RS, et al. A 3D Printed Fluidic Device that Enables Integrated Features. Anal Chem. 2013;85:5622–6. doi: 10.1021/ac4009594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cevenini L, Calabretta MM, Tarantino G, et al. Smartphone-interfaced 3D Printed Toxicity Biosensor Integrating Bioluminescent “Sentinel Cells”. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2016;225:249–57. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang YI, Abaci HE, Shuler ML. Microfluidic Blood Brain Barrier Model Provides In Vivo-Like Barrier Properties for Drug Permeability Screening. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2017;114:184–94. doi: 10.1002/bit.26045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grix T, Ruppelt A, Thomas A, et al. Bioprinting Perfusion-enabled Liver Equivalents for Advanced Organ-on-a-chip Applications. Genes. 2018;9:176. doi: 10.3390/genes9040176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Costa PF, Albers HJ, Linssen JE, et al. Mimicking Arterial Thrombosis in a 3D-Printed Microfluidic In Vitro Vascular Model Based on Computed Tomography Angiography Data. Lab Chip. 2017;17:2785–92. doi: 10.1039/c7lc00202e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X, Brooks JC, Hu J, et al. 3D-templated, Fully Automated Microfluidic Input/Output Multiplexer for Endocrine Tissue Culture and Secretion Sampling. Lab Chip. 2017;17:341–9. doi: 10.1039/c6lc01201a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hao S, Ha L, Cheng G, et al. A Spontaneous 3D Bone-on-a-chip for Bone Metastasis Study of Breast Cancer Cells. Small. 2018;14:1702787. doi: 10.1002/smll.201702787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh M, Tong Y, Webster K, et al. 3D Printed Conformal Microfluidics for Isolation and Profiling of Biomarkers from Whole Organs. Lab Chip. 2017;17:2561–71. doi: 10.1039/c7lc00468k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alessandri K, Andrique L, Feyeux M, et al. All-in-one 3D Printed Microscopy Chamber for Multidimensional Imaging, the UniverSlide. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42378. doi: 10.1038/srep42378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lembong J, Lerman MJ, Kingsbury TJ, et al. A Fluidic Culture Platform for Spatially Patterned Cell Growth, Differentiation, and Cocultures. Tissue Eng A. 2018;24:1715–32. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2018.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Au AK, Bhattacharjee N, Horowitz LF, et al. 3D-printed Microfluidic Automation. Lab Chip. 2015;15:1934–41. doi: 10.1039/c5lc00126a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takenaga S, Schneider B, Erbay E, et al. Fabrication of Biocompatible Lab-on-chip Devices for Biomedical Applications by Means of a 3D-Printing Process. Phys Status Solidi. 2015;212:1347–52. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y. Post-printing Surface Modification and Functionalization of 3D-Printed Biomedical Device. Int J. Bioprint. 2017;3:93–9. doi: 10.18063/IJB.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y. Three-dimensional-printing for Microfluidics or the Other Way Around? Int J Bioprint. 2019;5:61–73. doi: 10.18063/ijb.v5i2.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kadiak A. Advanced Manufacturing and Microenvironment Control for Bioengineering Complex Microbial Communities. 2017 Available from:https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1340 .

- 49.Walsh ME, Ostrinskaya A, Sorensen MT, et al. 3D-Printable Materials for Microbial Liquid Culture. 3D Print Addit Manufact. 2016;3:113–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chudobova D, Cihalova K, Skalickova S, et al. 3D-printed Chip for Detection of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Labeled with Gold Nanoparticles. Electrophoresis. 2015;36:457–66. doi: 10.1002/elps.201400321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krejcova L, Nejdl L, Rodrigo MAM, et al. 3D Printed Chip for Electrochemical Detection of Influenza Virus Labeled with CdS Quantum Dots. Biosens Bioelectron. 2014;54:421–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sweet EC, Liu N, Chen J, et al. Entirely-3D Printed Microfluidic Platform For On-site Detection of Drinking Waterborne Pathogens. IEEE 32ndInternational Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems. 2019:79–82. IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng L, Cai G, Wang S, et al. A Microfluidic Colorimetric Biosensor for Rapid Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Using Gold Nanoparticle Aggregation and Smart Phone Imaging. Biosens Bioelectron. 2019;124:143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee W, Kwon D, Chung B, et al. Ultrarapid Detection of Pathogenic Bacteria Using a 3D Immunomagnetic Flow Assay. Anal Chem. 2014;86:6683–8. doi: 10.1021/ac501436d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park C, Lee J, Kim Y, et al. 3D-printed Microfluidic Magnetic Preconcentrator for the Detection of Bacterial Pathogen Using an ATP Luminometer and Antibody-conjugated Magnetic Nanoparticles. J Microbiol Methods. 2017;132:128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen J, Zhou Y, Wang D, et al. UV-nanoimprint Lithography as a Tool to Develop Flexible Microfluidic Devices for Electrochemical Detection. Lab Chip. 2015;15:3086–94. doi: 10.1039/c5lc00515a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cox CA. A Multi-Channel 3D-Printed Bioreactor for Evaluation of Growth and Production in the microalga Dunaliella sp. 2016 Available from:https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2560 .

- 58.Lee S, Thio SK, Park SY, et al. An Automated 3D-printed Smartphone Platform Integrated with Optoelectrowetting (OEW) Microfluidic Chip for on-site Monitoring of Viable Algae in Water. Harmful Algae. 2019;88:101638. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2019.101638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duarte LC, Figueredo F, Ribeiro LE, et al. Label-free Counting of Escherichia coli Cells in Nanoliter Droplets Using 3D Printed Microfluidic Devices with Integrated Contactless Conductivity Detection. Anal Chim Acta. 20191071:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2019.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu Y, Huang X, Xie X, et al. Propidium Monoazide Pretreatment on a 3D-Printed Microfluidic Device for Efficient PCR Determination of “Live Versus Dead'microbial Cells. Environ Sci. 2018;4:956–63. doi: 10.1039/c8ew00058a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilson L, Iqbal K M, Simmons-Ehrhardt T, et al. Customizable 3D Printed Diffusion Chambers for Studies of Bacterial Pathogen Phenotypes in Complex Environments. J Microbiol Methods. 2019;162:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Achinas S, Euverink GJ. New Advances on Fermentation Processes. IntechOpen; London: 2019. Development of an Anaerobic Digestion Screening System Using 3D-Printed Mini-Bioreactors. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elliott O, Gray S, McClay M, et al. Design and Manufacturing of High Surface Area 3D-Printed Media for Moving Bed Bioreactors for Wastewater Treatment. J Contemp Water Res Educ. 2017;160:144–56. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koch AL. Willy, Hoboken; New Jersey: 2009. Microbial Growth Measurement, Methods. Encyclopedia of Industrial Biotechnology:Bioprocess, Bioseparation, and Cell Technology; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Okoh AI, Odjadjare EE, Igbinosa EO, et al. Wastewater Treatment Plants as a Source of Microbial Pathogens in Receiving Watersheds. Afr J Biotechnol. 2007;6:2932–44. [Google Scholar]