Key Points

Question

What are the patient-reported outcomes of risankizumab treatment for moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis in UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2?

Findings

Data from 997 patients who were randomized 3:1:1 to risankizumab, ustekinumab, and placebo in 2 replicate 52-week clinical trials showed a superior and statistically significant effect of risankizumab compared with placebo and ustekinumab in relieving and eliminating plaque psoriasis symptoms, improving health-related quality of life, and reducing psychological distress, with both a quick onset and sustaining of benefits over the long term.

Meaning

Risankizumab is an efficacious novel biologic treatment with meaningful improvements in symptoms, mental health, and quality of life for patients with psoriasis.

This secondary analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials compares patient-reported outcomes of treatment with risankizumab vs ustekinumab and placebo in psoriasis symptoms, health-related quality of life, and mental health among patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

Abstract

Importance

Demonstrating the value of therapies from a patient’s perspective is increasingly important for patient-centered care.

Objective

To compare patient-reported outcomes (PROs) with risankizumab vs ustekinumab and placebo in psoriasis symptoms, health-related quality of life (HRQL), and mental health among patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2 studies were replicate 52-week phase 3, randomized, multisite, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active comparator-controlled trials conducted in 139 sites (including hospitals, academic medical centers, clinical research units, and private practices) globally in Asia-Pacific, Japan, Europe, and North America. Adults (≥18 years) with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis with body surface area (BSA) involvement of 10% or more, Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) scores of 12 or higher, and static Physician’s Global Assessment (sPGA) scores of 3 or higher were included.

Interventions

In each trial, patients were randomly assigned (3:1:1) to 150 mg of risankizumab, 45 mg or 90 mg of ustekinumab (weight-based per label) for 52 weeks, or matching placebo for 16 weeks followed by risankizumab.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Integrated data from 2 trials were used to compare Psoriasis Symptom Scale (PSS) (total score and item scores for pain, redness, itchiness, and burning), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), 5-level EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D-5L), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), at baseline, week 16, and week 52.

Results

A total of 997 patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis were analyzed. Across all arms, the mean age was 47.2 to 47.8 years and 68.3% (136/199 for ustekinumab) to 73.0% (146/200 for placebo) were men. Patients’ characteristics and PROs were comparable across all treatment arms at baseline (n = 598, 199, 200 for risankizumab, ustekinumab, and placebo, respectively). At week 16, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with risankizumab than those treated with ustekinumab or placebo achieved PSS = 0, indicating no psoriasis symptoms (30.3% [181/598], 15.1% [30/199], 1.0% [2/200], both P < .001), and DLQI = 0 or 1 indicating no impact on skin-related HRQL (66.2%, 44.7%, 6.0%, P < .001). Significantly greater proportions of patients treated with risankizumab achieved minimally clinically important difference (MCID) than ustekinumab or placebo for DLQI (94.5% [516/546], 85.1% [149/175], 35.6% [64/180]; both P < .001), EQ-5D-5L (41.7% [249/597] vs 31.5% [62/197], P = .01; vs 19.0% [38/200], P < .001), and HADS (anxiety: 69.1% [381/551] vs 57.1% [104/182], P = .004; vs 35.9% [66/184], P < .001; depression: 71.1% [354/598] vs 60.4% [96/159], P = .01; vs 37.1% [59/159], P < .001). At week 52, improvements in patients treated with risankizumab compared with those treated with ustekinumab were sustained for PSS, DLQI, and EQ-5D-5L.

Conclusions and Relevance

Risankizumab significantly improved symptoms of moderate to severe psoriasis, improved HRQL, and reduced psychological distress compared with ustekinumab or placebo.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT02684370 (UltIMMa-1) and NCT02684357 (UltIMMa-2)

Introduction

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated systemic disease, affecting between 1% and 4% of the population in developed countries.1,2,3 It is characterized by patches of inflamed and thick skin covered with dry and silvery scales (plaques) that are typically accompanied by a burning sensation, itching, and pain.4,5 The visual manifestation of plaques frequently results in patient psychological distress, a sense of stigmatization, social isolation, and embarrassment.4,5,6 Its physical and psychosocial burden can substantially compromise social functioning, work and daily activity, and health-related quality of life (HRQL) of many patients with psoriasis, particularly those with moderate to severe disease.5,7,8,9 Since the introduction of biologics for moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis over a decade ago, novel innovative therapies have continued raising the standards for efficacy outcomes, not only for a higher level of plaque clearance, but also a meaningful improvement in patients’ HRQL.10,11,12,13,14

Risankizumab, an interleukin (IL)-23 inhibitor, is a novel humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody approved in the US and Europe.15 Two phase 3, replicate clinical trials demonstrated risankizumab’s superior efficacy to ustekinumab, an IL-12/23 inhibitor, in achieving complete or near-complete skin clearance in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis while maintaining a favorable safety profile similar to ustekinumab.15 Several patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments were included in the trials; the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and the Psoriasis Symptom Scale (PSS) at week 16 were ranked as secondary end points. The present study reported treatment efficacy over time from a patient’s perspective through PROs in these 2 phase 3 trials.

Methods

Data Source

This study combined data from UltIMMa-1 (NCT02684370)16 and UltIMMa-2 (NCT02684357),17 2 replicate, 52-week, randomized, multisite, double-blind, placebo-controlled, and active comparator-controlled phase 3 clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of risankizumab vs placebo and ustekinumab. Protocols for each trial are available in Supplement 1 (UltIMMa-1) and Supplement 2 (UltIMMa-2). To be eligible for the study, patients were required to be adults with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis who had at least 10% of affected body surface area (BSA), a Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) score of 12 or higher, and a static Physician’s Global Assessment (sPGA) score of 3 or higher. Between February 24, 2016, and August 31, 2016 (for UltIMMa-1) and March 1, 2016, and August 30, 2016 (for UltIMMa-2), patients were randomized 3:1:1 to risankizumab or ustekinumab for 52 weeks, or to placebo for 16 weeks followed by risankizumab thereafter.15 All aspects of this study were approved by institutional review boards or independent ethics committee at each study site; written informed consent was obtained for each participant prior to the study’s initiation. A detailed description of the trial design and report of efficacy and safety outcomes is available in Gordon et al.15,16,17

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Owing to their clinical relevance, the trials included the following instruments that capture different aspects of patients’ perspectives: a PRO instrument on psoriasis symptoms, the PSS;18 2 HRQL-related instruments, the DLQI19 and the 5-level EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D);20 and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).21 Other than the PSS, this study reported PROs at baseline, week 16, and week 52.

Psoriasis Symptom Scale

The PSS is a recently developed and validated PRO instrument measuring the severity of 4 types of psoriasis symptoms, including pain, itching, redness, and burning, over a 24-hour recall period.18,22 Each symptom item is reported on a 5-point scale from 0 to 4, with 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, 4 = very severe. The 4 individual item scores are summed to give a total score ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 16 (very severe symptoms). This study reported PSS scores at baseline, every 4 weeks until week 16 (the primary trial end point timing), and every 6 weeks until week 52 (the end of the trials).

Dermatology Life Quality Index

The DLQI is a 10-item questionnaire measuring the effect of dermatological diseases on patients over the last week. The 10 items, each scored 0 to 3, concern symptoms (itchy/sore/painful/stinging), feelings (embarrassed/self-conscious), daily activities (shopping/home/garden), choice of clothes, social or leisure activities, sport, work/school, personal relationships, sexual difficulties, and problem with taking a treatment.19 The DLQI total score is the sum of each individual item score and ranges from 0 or 1 (no effect on HRQL) to 30 (extremely large effect on HRQL).23

Five-Level EuroQoL-5D

The EQ-5D-5L is a preference-based generic questionnaire for assessing HRQL pertaining to 5 dimensions of health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression).20 Each dimension of health has 5 levels of severity (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, or extreme problems) and their responses are converted into a utility score ranging from 0 (death) to 1 (full health) through an established algorithm to reflect the level of a patient’s well-being.24

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The HADS consists of 2 scales, anxiety and depression, to assess psychological distress in nonpsychiatric patients.21 The questionnaire comprises 14 items, 7 for each scale, with a score ranging from 0 (no distress) to 21 (high distress). A score of 8 points is used as the threshold to identify patients who have symptoms of anxiety or depression.25

Statistical Analysis

Baseline patient demographics, disease characteristics, comorbidities, and PRO scores were summarized descriptively with mean (SD) for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables.

The proportions of responders for each PRO instrument were reported. To align with clinical assessments, 2 definitions of responders were used for the PSS total score (1) PSS = 0 (psoriasis symptom free), and (2) PSS = 0/1 (psoriasis symptom free or having mild problems for no more than 1 type of symptom). Two definitions of responders were used for the DLQI total score (1) DLQI = 0/1 (little to no effect on life); and (2) a meaningful reduction of 4 or more points from baseline, the threshold for DLQI’s minimally clinically importance difference (MCID).26 For EQ-5D-5L, responders were defined as a meaningful improvement from baseline that met or exceeded the MCID of 0.10 points.27 For each HADS scale, responders were defined when a meaningful reduction from baseline of 1.5 points or more (the MCID threshold)28 was observed. In addition, the proportion of patients on either scale with a score lower than 8 was estimated.24 Patients whose DLQI, EQ-5D-5L, or HADS scores were lower than the respective MCID threshold at baseline were excluded from MCID-based responder analyses. Pairwise comparisons between treatment arms were conducted using χ2 tests. Missing values for categorical outcomes (PSS = 0, PSS = 0/1, DLQI = 0/1, HADS <8) were handled with nonresponder imputation (NRI), and for continuous outcomes (DLQI, EQ-5D-5L, HADS) with last observation carried forward (LOCF).

Multivariable logistic regression models were conducted for PRO responses at week 52, controlling for age, sex (female vs male), race (White vs non-White), body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), baseline PASI score, smoking status (current smoker vs ex-smoker vs never smoked), psoriasis duration since diagnosis, PRO baseline value, and prior exposure to any biologic. All analyses were conducted for patients who received the same treatment over time.

Statistical analysis plans for each trial are detailed in Supplement 3 (for UltIMMa-1) and Supplement 4 (for UltIMMa-2).

Results

Baseline Patient Characteristics

A total of 997 patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis from UltiMMA-1 and UltiMMA-2 were included, with 598 randomized to risankizumab, 199 to ustekinumab, and 200 to placebo (eFigure 1 in Supplement 5). Baseline demographic and disease characteristics, comorbidities, and PROs across treatment arms are shown in Table 1. More than two-thirds of the patients were men (68.3% for ustekinumab [136/199] to 73.0% for placebo [146/200]); the mean age was between 47.2 to 47.8 years and mean BMI was between 30.2 to 30.5 across the arms. More than one-third of the patients had prior exposure to a biologic agent (ranging between 36.7% for ustekinumab [73/199] to 41.0% for placebo [82/200]).

Table 1. Patient Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Risankizumab (n = 598) | Ustekinumab (n = 199) | Placebo (n = 200) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Women, No. (%) | 183 (30.6) | 63 (31.7) | 54 (27.0) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 47.2 (13.6) | 47.5 (14.1) | 47.8 (13.5) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White, No. (%) | 455 (76.1) | 165 (82.9) | 158 (79.0) |

| Black or African American, No. (%) | 20 (3.3) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) |

| Asian, No. (%) | 111 (18.6) | 26 (13.1) | 35 (17.5) |

| Other, No. (%) | 12 (2.0) | 5 (2.5) | 4 (2.0) |

| Hispanic, No. (%) | 67 (11.2) | 24 (12.1) | 31 (15.5) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 90.0 (22.4) | 90.4 (22.2) | 90.5 (20.1) |

| Weight ≤100 kg, No. (%) | 429 (71.7) | 143 (71.9) | 143 (71.5) |

| Weight >100 kg, No. (%) | 169 (28.3) | 56 (28.1) | 57 (28.5) |

| BMI,a mean (SD) | 30.5 (7.0) | 30.4 (6.8) | 30.2 (6.2) |

| Disease characteristics | |||

| PASI, mean (SD) | 20.6 (7.7) | 19.2 (6.4) | 19.7 (7.0) |

| BSA involvement (%), mean (SD) | 26.2 (15.6) | 23.0 (13.6) | 26.0 (16.6) |

| Psoriasis duration since diagnosis, mean (SD), y | 18.1 (12.6) | 17.3 (11.2) | 19.1 (13.3) |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L, mean (SD) | 5.7 (8.5) | 5.3 (8.5) | 5.9 (9.5) |

| sPGA score, mean (SD) | 3.2 (0.4) | 3.2 (0.4) | 3.2 (0.4) |

| sPGA moderate, No. (%) | 484 (80.9) | 166 (83.4) | 163 (81.5) |

| sPGA severe, No. (%) | 114 (19.1) | 33 (16.6) | 37 (18.5) |

| Any previous biologic therapy, No. (%) | 222 (37.1) | 73 (36.7) | 82 (41.0) |

| TNF inhibitor, No. (%) | 134 (22.4) | 43 (21.6) | 48 (24.0) |

| Non-TNF inhibitor, No. (%) | 129 (21.6) | 48 (24.1) | 49 (24.5) |

| Patient-reported outcomes, mean (SD) | |||

| PSS total score | 8.1 (3.8) | 8.5 (3.7) | 8.1 (3.5) |

| PSS pain | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.1) |

| PSS redness | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.5 (0.9) |

| PSS itchiness | 2.4 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.0) |

| PSS burning | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.2) |

| DLQI total score | 13.3 (7.2) | 12.7 (7.0) | 12.6 (6.5) |

| EQ-5D-5L | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) |

| HADS anxiety scale | 7.2 (4.1) | 7.3 (4.3) | 6.9 (3.9) |

| Symptomatic anxiety (>8), No. (%) | 244 (40.8) | 83 (41.7) | 77 (38.5) |

| HADS depression scale | 5.3 (3.8) | 5.3 (4.0) | 5.3 (3.9) |

| Symptomatic depression (>8), No. (%) | 150 (25.1) | 56 (28.1) | 54 (27.0) |

| Comorbidities, No.(%) | |||

| Angina pectoris | 5 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.0) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 6 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 87 (14.6) | 28 (14.1) | 27 (13.5) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 139 (23.4) | 53 (26.8) | 50 (25.3) |

| Hypertension | 182 (30.5) | 72 (36.5) | 49 (24.5) |

| Myocardial infarction | 14 (2.3) | 9 (4.5) | 2 (1.0) |

| Obesity | 298 (49.8) | 93 (46.7) | 97 (48.5) |

| Psoriatic arthritis (diagnosed or suspected) | 159 (26.6) | 50 (25.1) | 68 (34.0) |

| Stroke | 7 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Transient ischemic attack | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EQ-5D-5L, 5-level EuroQoL-5D; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PSS, Psoriasis Symptom Scale; sPGA, static Physician's Global Assessment; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Psoriasis Symptom Scale (PSS)

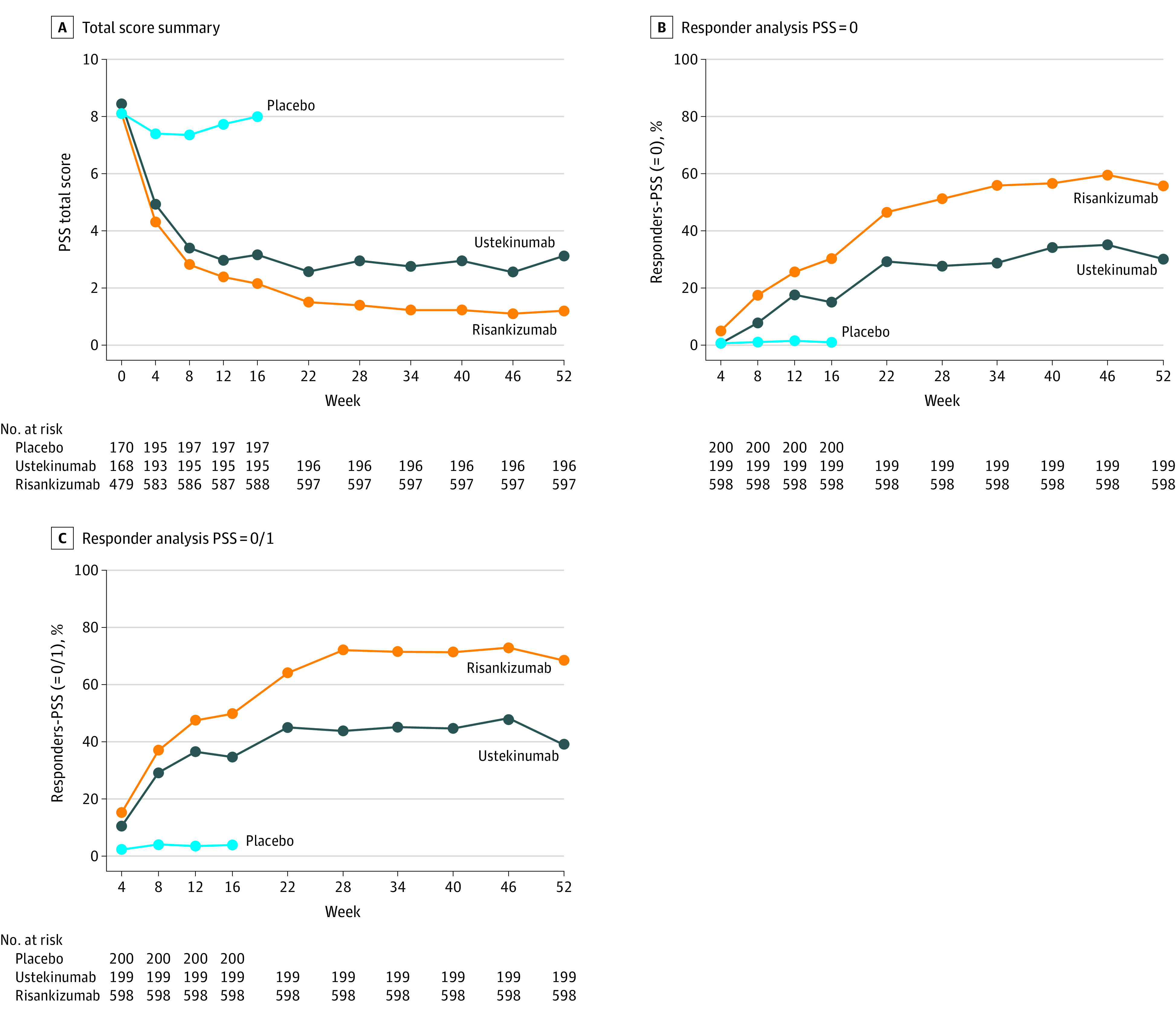

At baseline, the mean PSS scores were between 8.1 to 8.5 across treatment arms. After treatment, patients in the risankizumab arm had significantly lower PSS total scores compared with those in the placebo arm at week 4 through week 16 (4.3, 2.8, 2.4, and 2.2 vs. 7.4, 7.4, 7.7, and 8.0, respectively; all P < .001) and patients treated with ustekinumab at week 4 through week 52 (Figure 1A). At week 16, the mean (SD) of the PSS scores were 2.2 (2.5), 3.2 (3.3), and 8.0 (4.4) for patients treated with risankizumab, ustekinumab, and placebo, respectively (all P < .001); at week 52, the mean (SD) PSS scores were 1.2 (2.2) and 3.1 (3.6) for those treated with risankizumab and ustekinumab, respectively (P < .001).

Figure 1. Total Psoriasis Symptom Scale (PSS) Score Analyses.

A, PSS Total score summary.Mean values are shown. The PSS total scores were exploratory outcomes in the trials. The last observation carried forward imputation was adopted for missing data. Risankizumab-treated patients had significantly lower PSS total scores compared with placebo-treated patients at week 4 through week 16 (P < .001) and ustekinumab-treated patients at week 4 through week 52 (P = .01 at week 4, P = .01 at week 8, P = .008 at week 12, and P < .001 at all other time points). B, PSS = 0 Responder Analysis. The nonresponder imputation (NRI) approach was used. PSS = 0 at week 16 was a ranked secondary outcome; all other time points were exploratory outcomes. A significantly greater proportion of risankizumab-treated patients achieved PSS = 0, compared with patients treated with placebo (P = .008 at week 4, P < .001 at all other time points) and those treated with ustekinumab (P = .02 at week 4, P = .03 at week 12, and P < .001 at all other time points). C, PSS = 0/1 responder analysis. NRI approach was used. PSS = 0/1 was an exploratory outcome. From week 12 through week 52, a significantly greater proportion of risankizumab-treated patients achieved PSS = 0/1 compared with ustekinumab-treated patients (P = .01 at week 12 and P < . 001 at week 16 through week 52).

At all time points beyond baseline, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with risankizumab achieved PSS = 0, compared with those treated with placebo (P < .001) and those treated with ustekinumab (P = .02 at week 4, P = 0.03 at week 12; P < .001 at all other time points; PSS = 0 at week 16 was a ranked secondary outcome compared with placebo, all other time points were exploratory outcomes) (Figure 1B). From week 12 through week 52, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with risankizumab achieved PSS = 0/1 compared with those treated with ustekinumab (P = .01 at week 12 and P < .001 at week 16 through 52; PSS = 0/1 was an exploratory outcome). At all time points beyond baseline, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with risankizumab achieved PSS = 0/1 compared with placebo (P < .001) (Figure 1C). Compared with patients treated with ustekinumab, 15.2% (49.8% [298/598] for risankizumab, 34.7% [69/199] for ustekinumab) more at week 16 and 29.2% (68.4% [409/598] for risankizumab, 39.2% [78/199] for ustekinumab) more at week 52 of those treated with risankizumab.

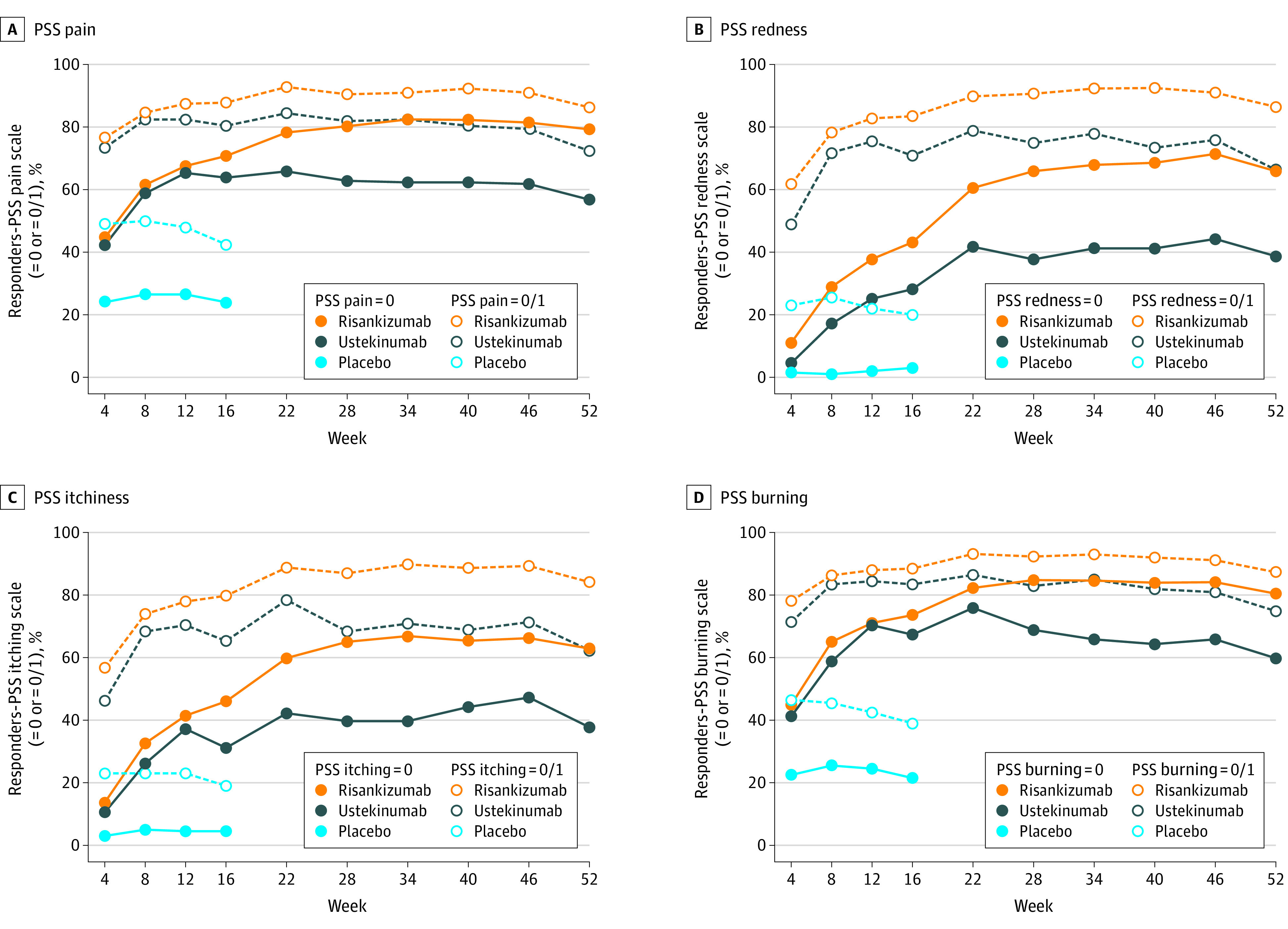

In terms of psoriasis symptoms for pain, redness, itchiness, and burning, significantly greater proportions of patients treated with risankizumab achieved a score of 0 (symptom free) or 1 (mild symptom) on each of the PSS items at week 4 through week 16 compared with those treated with placebo (P < .001) (Figure 2; exploratory outcomes). Compared with patients treated with ustekinumab, a significantly greater proportion of those treated with risankizumab achieved PSS pain = 0 (P < .001 from week 22 onward), PSS redness = 0 (P = .009 at weeks 4, 8, 12 and P < .001 at all other time points), PSS itchiness = 0 (P < .001 from week 16 onward), and PSS burning = 0 (P < .001 from week 28 onward) (Figure 2). The difference between the treatment arms was less pronounced when the threshold was lowered to allow achievement of symptom score = 0/1, though significant differences largely remain.

Figure 2. Psoriasis Symptom Scale (PSS) Items Scales Responder Analyses (Exploratory Outcomes)a.

A, PSS pain. B, PSS redness. C, PSS itchiness. D, PSS burning.

aSignificantly greater proportions of patients treated with risankizumab achieved a score of 0 or 1 on each of the PSS items at week 4 through week 16 compared with placebo. Compared with patients treated with ustekinumab, a significantly greater proportion of those treated with risankizumab achieved PSS pain = 0 (P < .001 from week 22 onward), PSS redness = 0 (P = .01 at week 4, P = .001 at week 8, P = .001 at week 12, and P < .001 at all other time points, PSS itchiness = 0 (P < .001 from week 16 onward), and PSS burning = 0 (P < .001 from week 28 onward).

Findings from the multivariable analyses at week 52 were consistent with unadjusted results for PSS = 0 (odds ratio [OR], 2.69; P < .001) and PSS = 0/1 (OR, 3.10; P < .001) for patients treated with risankizumab vs those treated with ustekinumab (Table 2; all exploratory outcomes). In addition to treatment exposure, the factors significantly associated with PSS = 0 or PSS = 0/1 response were race, BMI, and baseline PSS total score. Prior biologic use was also a significant factor for PSS = 0/1 response but was not for PSS = 0 response.

Table 2. Multivariable Responder Analyses at Week 52 (Exploratory Outcomes)a.

| Variable | PSS = 0 | PSS = 0/1 | DLQI MCID = 4 | DLQI = 0/1 | EQ-5D-5L MCID = 0.10 | Anxiety scale MCID = 1.5 | Depression scale MCID = 1.5 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | P value | Odds ratio | P value | Odds ratio | P value | Odds ratio | P value | Odds ratio | P value | Odds ratio | P value | Odds ratio | P value | |

| Intercept | 3.60 | .03 | 5.36 | .008 | 0.44 | .48 | 5.60 | .003 | 6226.71 | <.001 | 0.45 | .20 | 0.85 | .81 |

| Risankizumab vs ustekinumab | 2.69 | <.001 | 3.10 | <.001 | 5.27 | <.001 | 3.89 | <.001 | 1.80 | .01 | 1.25 | .25 | 1.15 | .51 |

| Age | 0.99 | .21 | 0.99 | .40 | 1.00 | .85 | 0.99 | .25 | 0.98 | .03 | 1.00 | .83 | 0.99 | .10 |

| Sex (female vs male) | 0.87 | .44 | 0.86 | .45 | 1.47 | .26 | 1.41 | .05 | 1.01 | .96 | 1.13 | .50 | 0.85 | .43 |

| Race (White vs non-White) | 1.55 | .04 | 1.58 | .04 | 2.70 | .02 | 1.70 | .01 | 0.84 | .47 | 0.64 | .05 | 1.57 | .05 |

| BMIb | 0.96 | <.001 | 0.96 | .002 | 1.01 | .73 | 0.96 | <.001 | 0.97 | .04 | 0.98 | .08 | 0.97 | .02 |

| Baseline PASI | 1.00 | .70 | 1.01 | .44 | 1.01 | .64 | 1.00 | .90 | 1.04 | .005 | 1.02 | .08 | 1.05 | <.001 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||||||

| Current vs ex-smoker | 0.70 | .10 | 0.97 | .89 | 0.59 | .25 | 1.06 | .81 | 1.44 | .16 | 1.62 | .04 | 1.77 | .02 |

| Current vs never smoked | 0.86 | .44 | 0.86 | .47 | 0.72 | .43 | 1.18 | .41 | 1.25 | .32 | 1.03 | .88 | 1.06 | .76 |

| Psoriasis duration | 1.01 | .19 | 1.00 | .54 | 0.99 | .72 | 1.00 | .59 | 0.98 | .07 | 0.99 | .36 | 0.99 | .41 |

| Study (UltIMMa-2 vs UltIMMa-1) | 0.97 | .88 | 1.14 | .46 | 0.68 | .26 | 0.75 | .09 | 1.01 | .96 | 0.76 | .11 | 0.77 | .16 |

| Prior biologic use (0 vs ≥1) | 0.83 | .30 | 0.64 | .02 | 0.53 | .07 | 0.75 | .10 | 0.94 | .76 | 1.58 | .01 | 1.03 | .87 |

| PRO baseline value | 0.93 | .003 | 0.90 | <.001 | 1.16 | <.001 | 0.94 | <.001 | 0 | <.001 | 1.26 | <.001 | 1.25 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EQ-5D-5L, 5-level EuroQoL-5D; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MCID, Minimal Clinically Important Difference; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PRO, patient-reported outcome; PSS, Psoriasis Symptom Scale; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Odds ratios, coefficient estimates, and P values were estimated from multivariable logistic regression models controlling for age, sex (female vs male), race (White vs non-White), BMI, baseline PASI score, smoking status (current smoker vs ex-smoker vs never smoked), psoriasis duration since diagnosis, study indicator, prior biologic use (0 vs ≥1), and baseline value.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Dermatology Life Quality Index

At baseline, the mean DLQI scores were between 12.6 to 13.3 across treatment arms. A significantly greater proportion of patients treated with risankizumab were DLQI responders under the MCID criterion (exploratory outcomes), compared with placebo at week 16 (94.5% [516/546] vs 35.6% [64/180], P < .001) and with ustekinumab at week 16 (94.5% [516/546] vs 85.1% [149/175], P < .001) and week 52 (96.3% [526/546] vs 84.6% [148/175], P < .001). In addition, a significantly greater proportion of those treated with risankizumab achieved DLQI = 0/1 (ranked secondary outcome) compared with placebo at week 16 (66.2% [396/598] vs 6.0% [12/200], P < .001) and those treated with ustekinumab at week 16 (66.2% [396/598] vs 44.7% [89/199], P < .001) and week 52 (73.1% [437/598] vs 45.7% [91/199], P < .001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Responder Analyses for DLQI, EQ-5D-5L, and HADS.

| Variable | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Week 16 | Week 52 | |

| MCID-based DLQI responders (exploratory outcomes) | ||

| Risankizumab | 94.5 | 96.3 |

| Ustekinumab | 85.1 | 84.6 |

| Placebo | 35.6 | NA |

| P value risankizumab vs ustekinumab | <.001 | <.001 |

| P value risankizumab vs placebo | <.001 | NA |

| DLQI = 0/1 responders (ranked secondary outcomes) | ||

| Risankizumab | 66.2 | 73.1 |

| Ustekinumab | 44.7 | 45.7 |

| Placebo | 6.0 | NA |

| P value risankizumab vs ustekinumab | <.001 | <.001 |

| P value risankizumab vs placebo | <.001 | NA |

| MCID-based EQ-5D-5L responders (exploratory outcomes) | ||

| Risankizumab | 41.7 | 44.4 |

| Ustekinumab | 31.5 | 32.0 |

| Placebo | 19.0 | NA |

| P value risankizumab vs ustekinumab | .01 | .002 |

| P value risankizumab vs placebo | <.001 | NA |

| MCID-based HADS anxiety scale responders (exploratory outcomes) | ||

| Risankizumab | 69.1 | 65.5 |

| Ustekinumab | 57.1 | 60.4 |

| Placebo | 35.9 | NA |

| P value risankizumab vs ustekinumab | .004 | .25 |

| P value risankizumab vs placebo | <.001 | NA |

| MCID-based HADS depression scale responders (exploratory outcomes) | ||

| Risankizumab | 71.1 | 68.9 |

| Ustekinumab | 60.4 | 66.7 |

| Placebo | 37.1 | NA |

| P value risankizumab vs ustekinumab | .01 | .67 |

| P value risankizumab vs placebo | <.001 | NA |

| HADS anxiety scale (<8) (exploratory outcomes) | ||

| Risankizumab | 82.1 | 81.6 |

| Ustekinumab | 73.2 | 79.8 |

| Placebo | 61.5 | NA |

| P value risankizumab vs ustekinumab | .009 | .65 |

| P value risankizumab vs placebo | <.001 | NA |

| HADS depression scale (<8) (exploratory outcomes) | ||

| Risankizumab | 89.3 | 89.8 |

| Ustekinumab | 85.4 | 89.4 |

| Placebo | 70.5 | NA |

| P value risankizumab vs ustekinumab | .17 | .98 |

| P value risankizumab vs placebo | <.001 | NA |

Abbreviations: DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EQ-5D-5L, 5-level EuroQoL-5D; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; NA, not applicable.

Findings from the multivariable analyses were consistent with unadjusted results for MCID-based response at week 52 (OR, 5.27; P < .001), and for DLQI = 0/1 response at week 52 (OR, 3.89; P < .001) for patients treated with risankizumab vs those treated with ustekinumab (Table 2; all exploratory outcomes). In addition to treatment exposure, the factors significantly associated with MCID-based DLQI response included race and baseline DLQI total score; the factors significantly associated with DLQI = 0/1 response included race, BMI, and baseline DLQI total score.

Five-Level EQ-5D-5L

At baseline, the mean EQ-5D-5L scores were 0.8 across treatment arms. A greater proportion of patients treated with risankizumab were EQ-5D-5L responders under the MCID criterion, compared with placebo at week 16 (41.7% [249/597] vs 19.0% [38/200], P < .001) and those treated with ustekinumab at week 16 (41.7% [249/597] vs 31.5% [62/197], P = .01) and week 52 (44.4% [265/597] vs 32.0% [63/197], P = .003) (Table 3; exploratory outcomes).

Findings from the multivariable analyses were consistent with unadjusted results for MCID-based response at week 52 (OR, 1.80; P = .009) for patients treated with risankizumab vs ustekinumab (Table 2; exploratory outcomes). In addition to treatment exposure, the factors significantly associated with the response included age, BMI, and baseline PASI and EQ-5D-5L.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

At baseline, the mean anxiety scale score was between 6.9 to 7.3 and the mean depression 5.3, with 38.5% (77/200 for placebo) to 42.1% (83/197 for ustekinumab) and 25.2% (150/596 for risankizumab) to 28.4% (56/197 for ustekinumab) patients having symptoms of anxiety or depression (≥8), respectively, across treatment arms. At week 16, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with risankizumab were responders compared with those treated with ustekinumab and placebo (anxiety: 69.1% [381/551] vs 57.1% [104/182], P = .004, and vs 35.9% [66/184], P < .001; depression: 71.1% [354/498] vs 60.4% [96/159], P = .01, and vs 37.1% [59/159], P < .001) (Table 3; exploratory outcomes). At week 52, a substantial proportion of patients remained responders on both scales and on both treatment arms (risankizumab vs ustekinumab: anxiety 65.5% [361/551] vs 60.4% [110/182], P = .25; depression 68.9% [343/498] vs 66.7% [106/159], P = .67, respectively), and only approximately 10% of patients had symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Findings from the multivariable analyses were consistent with unadjusted results at week 52 (anxiety: OR, 1.25; P = .25; depression: OR, 1.15; P = .51) for patients treated with risankizumab vs ustekinumab (Table 2). Smoking status and the corresponding baseline HADS scale were significantly associated with the response for both scales. Race and prior biologic use were significantly associated with response for the anxiety subscale; BMI and baseline PASI were significantly associated with response for the depression subscale.

Discussion

In the era of patient-centered care, the use of PRO instruments in clinical trials is an important method to assess treatment efficacy from a patient’s perspective to complement and supplement traditional outcomes measured using biomarkers or physicians' assessments.29 Use of PROs is particularly relevant for chronic diseases such as psoriasis given the lifelong effect it has on patients. A separate study used pooled data from 3 phase 3 studies of risankizumab in moderate to severe psoriasis and found that sustaining high skin clearance or complete skin clearance (as measured via PASI) is associated with incremental and durable benefits in the quality of life and mental health of patients with psoriasis.30 The findings of this study confirmed the substantial disease burden at baseline and additionally found a superior effect of risankizumab compared with both placebo and ustekinumab, in relieving and eliminating the disease burden in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

Through the PSS, at baseline, patients reported symptoms such as redness and itching with a mean score between 2.3 and 2.6, indicating a level of moderate to severe disease severity; for symptoms of pain and burning, patients reported lower mean scores between 1.6 and 1.7, indicating mild to moderate disease severity. Correspondingly, the average DLQI scores of these patients at baseline ranged between 12.6 and 13.3, reflecting the large effect of psoriasis on their life.31 This study found that treatment with risankizumab was associated with a rapid onset of effect in relieving psoriasis symptoms, and in turn, improving HRQL and reducing psychological distress associated with psoriasis. In addition, this improvement was sustained and, in some cases, continued throughout the trial period. A significant overall improvement in symptoms was observed as early as week 4 and sustained with a reduction in PSS score at each consecutive time point until week 52. Correspondingly, improvement in DLQI was also significantly more in risankizumab-treated than ustekinumab-treated patients using both MCID-based and DLQI = 0/1 responder criteria. In addition, more patients treated with risankizumab than with ustekinumab had clinically meaningful improvement on their psychological distress at week 16 (statistically different) and week 52 (numerically higher for risankizumab).

The 5-level EQ-5D, as a generic preference-based measurement tool for an overall quality of life assessment, may not be a sensitive measurement for chronic plaque psoriasis.32 However, this study was able to find that a significantly greater proportion of patients showed improvements in EQ-5D-5L scores posttreatment with risankizumab. At baseline, the EQ-5D-5L score was comparable across the treatment arms with a mean of 0.8. By week 16, 10.2% (41.7% [249/597] for risankizumab vs 31.5% [62/197] for ustekinumab) more patients treated with risankizumab achieved clinically meaningful improvement in EQ-5D-5L and 12.4% (44.4% [265/597] for risankizumab vs 32.0% [63/197] for ustekinumab) more at week 52 when compared with those treated with ustekinumab.

Previous clinical trials have also found significant improvement in psoriasis symptoms13,14 and improvement in HRQL through DLQI in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis treated with other biologics, from older TNF antagonists10,11,12 to newer interleukin inhibitors.13,14,33,34,35 However, most of these studies had short follow-up periods (12-16 weeks) and, thus, did not allow for long-term evaluation of the PROs. Indeed, one of the strengths of the present study is the availability of longer time points at which PROs, including mental health impact, can be evaluated, allowing for both short- and long-term assessment.

These results align with prior clinical trials that evaluated the proportion of patients treated with ustekinumab found to have DLQI = 0/1 at short-term assessments.33,36 For example, in a clinical trial37 comparing ixekizumab with ustekinumab, the proportion of patients treated with ustekinumab achieving DLQI = 0/1 was 44.6% at week 12 and 53.0% at week 24. Despite differences in study designs, patient populations, and time points, these DLQI = 0/1 estimates for ustekinumab are consistent with those in ours, further validating the results of the present study and supporting the superiority of risankizumab in relieving the HRQL burden of disease through the perspective of the patients.

Limitations

Some limitations of this study should be considered. First, because patients enrolled in clinical trials may differ from those in practice, the generalizability of the study results may be limited. Second, the use of LOCF imputation for continuous measures may have introduced some bias in the comparisons. However, few missing data in the trials occurred, and the large changes observed in all measures suggest that if any bias occurred, it was minimal. Finally, the NRI imputation assumes that missing PRO scores were associated with nonresponse, which may have underestimated the true rate of response.

Conclusions

Risankizumab was superior to ustekinumab in reducing and potentially eliminating psoriasis symptoms as well as reducing psychological distress in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. In addition, compared with ustekinumab, risankizumab demonstrated substantially greater improvements in quality of life for this patient population with a quick onset of benefits and sustained long-term effects. These findings may further raise standards for treatments and provide promising outcomes for patients suffering from moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis.

Trial Protocol. UltIMMa-1

Trial Protocol. UltIMMa-2

Statistical Analysis Plan. UltIMMa-1

Statistical Analysis Plan. UltIMMa-2

eFigure. Consort Diagram

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):871-881.e871-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team . Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):377-385. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandran V, Raychaudhuri SP. Geoepidemiology and environmental factors of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Autoimmun. 2010;34(3):J314-J321. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krueger GG, Langley RG, Finlay AY, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of psoriasis improvement with etanercept therapy: results of a randomized phase III trial. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(6):1192-1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06948.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Korte J, Sprangers MA, Mombers FM, Bos JD. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9(2):140-147. doi: 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esposito M, Saraceno R, Giunta A, Maccarone M, Chimenti S. An Italian study on psoriasis and depression. Dermatology. 2006;212(2):123-127. doi: 10.1159/000090652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB Jr, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(3 Pt 1):401-407. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70112-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi J, Koo JY. Quality of life issues in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2)(suppl):S57-S61. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(03)01136-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Møller AH, Erntoft S, Vinding GR, Jemec GBE. A systematic literature review to compare quality of life in psoriasis with other chronic diseases using EQ-5D-derived utility values. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2015;6:167-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reich K, Nestle FO, Papp K, et al. Improvement in quality of life with infliximab induction and maintenance therapy in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(6):1161-1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reich K, Segaert S, Van de Kerkhof P, et al. Once-weekly administration of etanercept 50 mg improves patient-reported outcomes in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatology. 2009;219(3):239-249. doi: 10.1159/000237871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Revicki DA, Willian MK, Menter A, et al. Impact of adalimumab treatment on patient-reported outcomes: results from a Phase III clinical trial in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18(6):341-350. doi: 10.1080/09546630701646172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: Results from the phase III, double-blinded, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):405-417. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. ; ERASURE Study Group; FIXTURE Study Group . Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis--results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):326-338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon KB, Strober B, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and ustekinumab-controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10148):650-661. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31713-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clinicaltrials.gov . BI 655066 (Risankizumab) Compared to Placebo and Active Comparator (Ustekinumab) in Patients With Moderate to Severe Chronic Plaque Psoriasis. 2017. Accessed October 2018.https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02684370

- 17.Clinicaltrials.gov . BI 655066 Compared to Placebo & Active Comparator (Ustekinumab) in Patients With Moderate to Severe Chronic Plaque Psoriasis. 2018. Accessed October 2018. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02684357

- 18.Rentz AM, Skalicky AM, Burslem K, et al. The content validity of the PSS in patients with plaque psoriasis. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;1(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s41687-017-0004-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazzotti E, Barbaranelli C, Picardi A, Abeni D, Pasquini P. Psychometric properties of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) in 900 Italian patients with psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85(5):409-413. doi: 10.1080/00015550510032832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.EuroQol Research Foundation . EQ-5D-5L. 2018. Accessed October 2018. https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about

- 21.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rentz A, Mansukhani S, Esser D, et al. Reliability, Validity, and Ability to Detect Change of the Psoriasis Symptom Scale (PSS) in Patients with Plaque Psoriasis. EADV Congress, Paris, France [P2070]. 2018. Accessed October 2018. https://eadv.m-anage.com/Login.aspx?event=eadvparis2018

- 23.Shikiar R, Willian MK, Okun MM, Thompson CS, Revicki DA. The validity and responsiveness of three quality of life measures in the assessment of psoriasis patients: results of a phase II study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:71. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Feng Y, Mulhern B, van Hout B. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ. 2018;27(1):7-22. doi: 10.1002/hec.3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69-77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, Sturkey R, Finlay AY. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230(1):27-33. doi: 10.1159/000365390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen P, Lin KC, Liing RJ, Wu CY, Chen CL, Chang KC. Validity, responsiveness, and minimal clinically important difference of EQ-5D-5L in stroke patients undergoing rehabilitation. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(6):1585-1596. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1196-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puhan MA, Frey M, Büchi S, Schünemann HJ. The minimal important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6(1):46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FDA. Value and Use of Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) in Assessing Effects of Medical Devices. 2017. Accessed November 2017. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDRH/CDRHVisionandMission/UCM588576.pdf

- 30.Ryan C, Puig L, Zema C, et al. Incremental benefits on patient-reported outcomes for achieving PASI90 or PASI100 over PASI75 in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Paper presented at: Presented at the 27th EADV Congress 2018; Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: What do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(4):659-664. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swinburn P, Lloyd A, Boye KS, Edson-Heredia E, Bowman L, Janssen B. Development of a disease-specific version of the EQ-5D-5L for use in patients suffering from psoriasis: lessons learned from a feasibility study in the UK. Jval. 2013;16(8):1156-1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thaçi D, Blauvelt A, Reich K, et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: CLEAR, a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(3):400-409. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M, et al. ; UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 investigators . Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate to severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386(9993):541-551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60125-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakagawa H, Niiro H, Ootaki K; Japanese brodalumab study group . Brodalumab, a human anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody in the treatment of Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from a phase II randomized controlled study. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;81(1):44-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lebwohl M, Papp K, Wu J, et al. Neuropsychiatric adverse events in brodalumab psoriasis studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(6):AB178. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.691 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reich K, Pinter A, Lacour JP, et al. ; IXORA-S investigators . Comparison of ixekizumab with ustekinumab in moderate to severe psoriasis: 24-week results from IXORA-S, a phase III study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(4):1014-1023. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol. UltIMMa-1

Trial Protocol. UltIMMa-2

Statistical Analysis Plan. UltIMMa-1

Statistical Analysis Plan. UltIMMa-2

eFigure. Consort Diagram

Data Sharing Statement