Abstract

Background:

The ability to perform nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures is a core competency requirement for plastic surgery residents. However, limited data exist on training models to achieve competency in nonsurgical facial rejuvenation and on outcomes of these procedures performed by residents. The purpose here is to evaluate patient-reported outcomes and safety of nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures performed by plastic surgery residents.

Methods:

We prospectively enrolled 50 patients undergoing neuromodulator and/or soft-tissue filler injections in a resident cosmetic clinic between April-August 2016. Patients completed FACE-Q modules pre-procedure, and at 1-week and 1-month post-procedure. Paired t-tests were used to calculate statistical significance of changes between pre- and post-procedure scores. Effect sizes were calculated to assess clinical improvement from pre- to post-procedure. The magnitude of change was interpreted using Cohen’s arbitrary criteria (small 0.20, moderate 0.50, large 0.80).

Results:

Forty-five patients completed the study. Patients experienced significant improvements (p < 0.001) in all FACE-Q domains, including aging appearance appraisal (improved from 49.7 ± 29.4 to 70.1 ± 21.6, effect size 0.79), psychological well-being (44.0 ± 14.6 to 78.6 ± 20.7, effect size 1.93), social functioning (48.6 ± 16.6 to 75.5 ± 21.7, effect size 1.20), and satisfaction with facial appearance (50.1 ± 13.7 to 66.2 ± 19.7, effect size 0.95). At 1 month, overall satisfaction with outcome and decision were 75.8 ± 20.7 and 81.1 ± 20.4, respectively. No patients experienced complications.

Conclusions:

Nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures performed by residents can improve patients’ quality of life and provide high satisfaction without compromising safety.

Keywords: plastic surgery education, residency, facial rejuvenation, neurotoxin

INTRODUCTION

Facial rejuvenation with injectable agents continues to rise in popularity and nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures are the most commonly performed aesthetic procedures in the United States.[1] In 2016, patients underwent over 15 million nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures, with neuromodulator and soft-tissue filler injections being most prevalent. These procedures accounted for nearly 25% of total aesthetic surgery expenditures that year.[2] Therefore, the ability to competently and safely perform nonsurgical facial rejuvenation is integral to the practicing aesthetic surgeon and should be an essential component of comprehensive aesthetic surgery training in plastic surgery residency programs.

Currently, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) sets case minimums as a proxy for acceptable level of technical competency for graduating plastic surgery trainees. However, significant variability exists in aesthetic surgery training and education, particularly in regards to volume of, and exposure to, facial aesthetic surgery.[3] Recently, it was demonstrated that the bottom 10th percentile of plastic surgery residents failed to achieve minimums set by the ACGME for core nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures, including neuromodulator and soft tissue injections.[3] The discrepancy between the popularity of nonsurgical facial aesthetic procedures and resident exposure to these procedures needs to be addressed.[4,3] Models for achieving competency with these procedures in plastic surgery residency training are lacking.[5] Furthermore, there is limited literature on outcomes and safety following nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures performed by plastic surgery residents. Although patient-reported outcome measures, such as the FACE-Q, have emerged as validated mechanisms to assess patient satisfaction and quality of life, no studies to our knowledge have evaluated outcomes of these procedures performed by residents using the current iteration of the validated FACE-Q modules.[6–11]

A recent publication highlighted an institution’s experience with aesthetic surgery education utilizing a resident cosmetic clinic and demonstrated its operational structure, outcomes and safety for surgical aesthetic procedures.[12] In an effort to both meet ACGME requirements for plastic surgery trainees and educate residents in nonsurgical aesthetic procedures, our institution has also supported a biannual resident neurotoxin and fillers clinic for residents in their second year of training and beyond. The success of such clinics depends on patient outcomes and safety. In their best practice guidelines for resident aesthetic education, The American Council of Academic Plastic Surgeons (ACSPS) identified the need for studies reporting patient satisfaction and safety with resident-performed aesthetic procedures.[5] Therefore, the purpose of this study is to prospectively evaluate patient-reported outcomes, as measured by the FACE-Q, of nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures performed by plastic surgery residents. Our goal is to provide a generalizable model for resident aesthetic education that other institutions can adopt in an effort to reduce discrepancies across training programs and fulfill ACGME requirements.

METHODS

Study Design and Patient Population

After obtaining appropriate institutional review board approval (201604087), 50 consecutive patients were prospectively enrolled in this study. Patients were recruited from one of two biannual neuromodulator and soft-tissue filler clinics as well as weekly resident cosmetic clinics between April 2016 and August 2016. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients were eligible if they were over 18 years of age and able to provide informed consent. Patients who had neuromodulator or soft-tissue filler injections within 3 months of the study start date or had a known contraindication to these agents were excluded.

Participants were evaluated by residents in the resident cosmetic clinic and were eligible for neuromodulator alone, soft-tissue filler alone, or neuromodulator and soft-tissue filler injection based on their goals and discussion with the resident. The resident cosmetic clinic at our institution has existed for over twenty-five years. Patients were not charged a fee and were not reimbursed for participation. Two full-time academic aesthetic surgeons supervised all injections. Patients underwent injection with a neuromodulator (onabotulinumtoxinA/Botox® or incobotulinumtoxinA/Xeomin®) and/or a soft-tissue filler (Juvederm XC®, Belotero®, Radiesse®). The product for injection was obtained through educational training grants from Allergan© and Merz©. Injection sites for neuromodulators included forehead, glabella, and crow’s feet. All of the neurotoxins were diluted with 50U in 2 cc of preservative-free saline. Soft-tissue filler injection sites included the tear trough, lips, nasolabial folds, malar area and mandibular border.

Demographic and clinical data were tabulated. A pre-procedure FACE-Q was administered that included the following modules: Aging Appearance Appraisal, Psychological Well-Being, Social Functioning Scale and Satisfaction with Facial Appearance.[10,7] Patients completed a FACE-Q one week post-procedure. This assessed patient’s recovery with the module of: Early Life Impact and Early Symptoms. A post-procedure FACE-Q was e-mailed at one month and included the following modules: Aging Appearance Appraisal, Psychological Well-Being, Social Functioning Scale, Satisfaction with Facial Appearance, Satisfaction with Outcome, and Satisfaction with Decision. All questionnaires were completed by patients electronically using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) Software.[13] FACE-Q scores were calculated using the FACE-Q Manual and transformed from 0 to 100, with higher scores correlating with better outcomes.[10,7] Patient charts were reviewed at 1 month for any documented complications. Complications were defined a priori in accordance with previously reported classifications in the literature, and included vascular complications, technical errors (wrong location, inappropriate depth, and inappropriate volume), levator ptosis, and infectious complications.[14,15] Patients were instructed to return to the clinic for a touch up procedure, at no cost, if there were concerns regarding the aesthetic outcome and these data were tracked.

Statistical Analyses

Summary statistics were tabulated via established methods. For continuous variables with normal sample distributions (skewness < 5 and kurtosis < 5), Student’s t-test was used to compare group means, whereas for continuous variables with non-normal sample distributions, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test was used to compare group medians. As the purpose of this study was to evaluate outcomes with all neuromodulator and soft-tissue filler injections by residents, and not for impact by product type, a pooled analysis was performed regardless of neuromodulator and/or soft-tissue filler injection. For FACE-Q domains involving a pre-procedure and post-procedure measurement, the change was calculated as the mean difference of post-procedure minus pre-procedure measurement, with paired t-tests used to calculate the significance of change. Furthermore, effect sizes were calculated to assess for the clinical significance of the numeric improvement in certain FACE-Q domains from pre-procedure to post-procedure. The magnitude of change was interpreted using Cohen’s arbitrary criteria, a validated and established metric.[16] Effect sizes of 0.20-0.49 are interpreted as small, 0.50-0.79 moderate, and >0.80 large.[16,10,7,8]

RESULTS

Fifty patients were prospectively enrolled in this study and 45 patients (90.0%) completed the study by completing the pre-procedure, 1-week post-procedure, and 1-month post-procedure FACE-Q surveys (Table 1). The mean age was 45.4 ± 12.8 years (range: 20 - 69 years) and 98% (44 patients) were women. Neuromodulator only was injected in 26.6% of patients (n = 12), soft-tissue filler only in 40.0% (n=18), and both neuromodulator and soft-tissue filler in 33.3% (n=15).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and study characteristics

| Age, mean ± SD, range | 45.4 ± 12.8 (20-69) |

| Female, % | 98.0% |

| Response rate, % | 90% |

| Neuromodulator only, % | 26.6% |

| Filler only, % | 40.0% |

| Neuromodulator and filler, % | 33.3% |

| Median units of neuromodulator, Interquartile range, U | 40 (25-50) |

| Median volume of filler, Interquartile range, cc | 1 (0.725-1.725) |

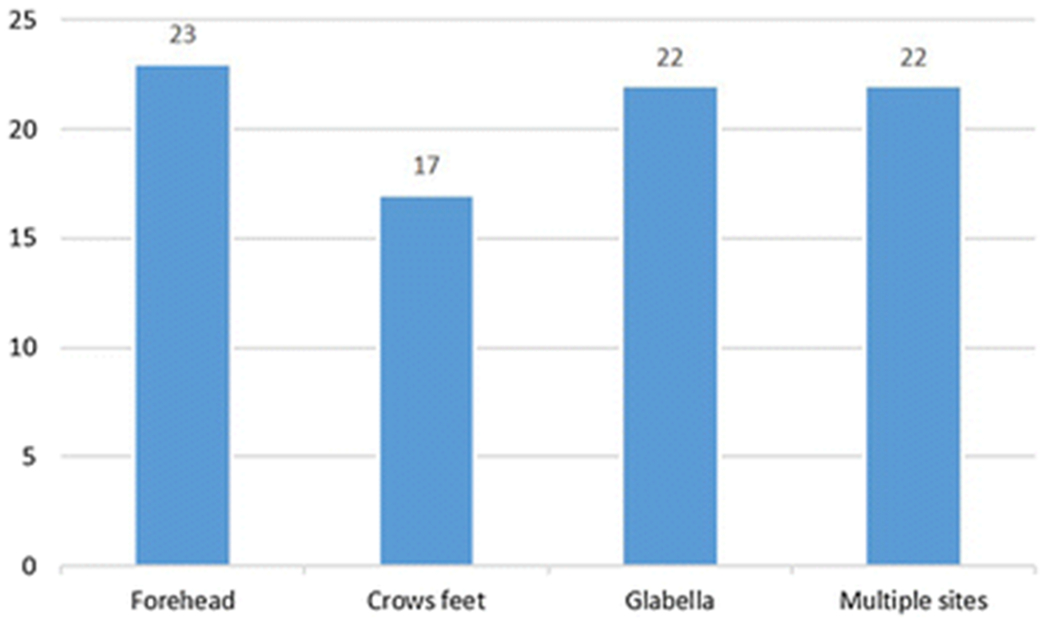

The median units of neuromodulator administered was 40U (interquartile range 25 – 50 U, range 25-75 U). These were administered in three anatomic sites including the forehead (n = 23), crow’s feet (n = 17), and glabella (n =22). Multiples anatomic sites were injected in 22 patients, with a median number of 2 anatomic sites injected per patient (range 1-3) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of neuromodulator injection by anatomic location

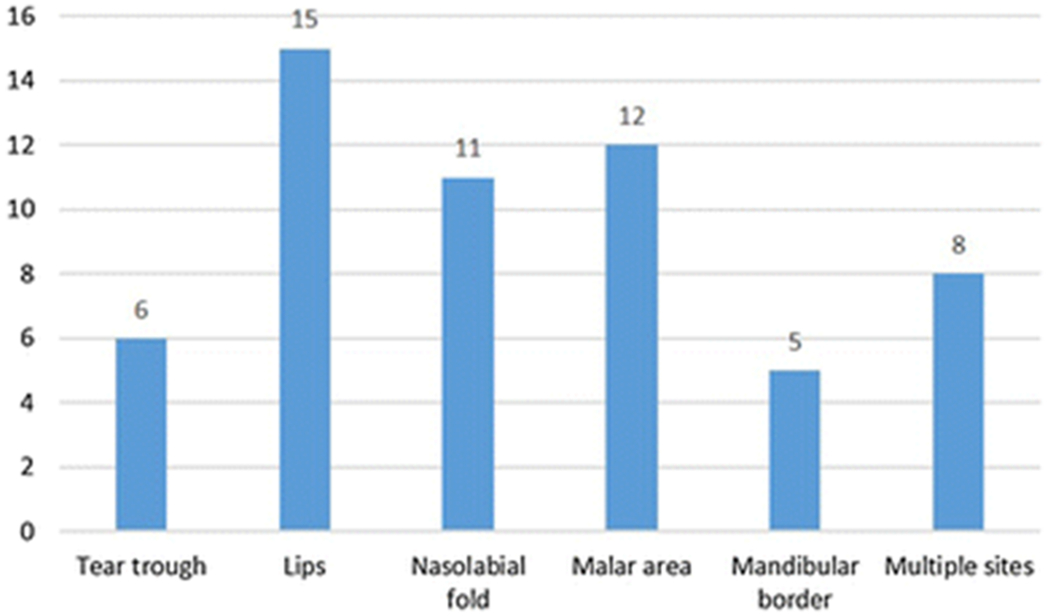

The median volume of filler was 1 cc (interquartile range 0.725 – 1.725 cc, range 0.4 – 3.4 cc). These were injected in five anatomic sites, including the tear trough (n = 6), lips (n = 15), nasolabial folds (n = 11), malar area (n = 12) and mandibular border (n = 5). Multiple anatomic sites were injected in 8 patients with a median number of 1 anatomic site injected per patient (range 1-4) (Figure 2). In Figure 3, we provide an example of a patient who was injected in multiples sites, including 45 units of neuromodulator in the forehead and glabella, 0.8cc of filler for malar augmentation, and 0.8cc of filler for tear trough correction (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Frequency of soft-tissue filler by anatomic location

Figure 3.

A 43-year-old female patient injected in multiples sites, including 45U of Botox in the forehead and glabella, 0.8 cc Juvederm XC for malar augmentation, and 0.8 cc of Belotero for tear trough correction. Top photos are pre-procedure and bottom photos are 3 months post-procedure.

Early Recovery Symptoms and Early Life Impact at 1 week

Patients’ early symptoms and potential complications were assessed using the Early Recovery Symptom and Early Life Impact domain of the FACE-Q at 1-week post-procedure. Participants had an early life impact mean score of 95.8 ± 7.1. An effect size could not be calculated as early life impact was only assessed at one time point. One patient reported feeling extremely bruised, two patients had moderate swelling, one patient had moderate itching, and one patient had moderate headaches post-procedure. The remainder of participants either had “a little” or “no” symptoms as outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Early recovery symptoms at 1 week

| Symptom | Not at all | A Little | Moderate | Extremely |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discomfort | 38 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Tenderness | 31 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Feeling sore | 35 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Feeling bruised | 27 | 17 | 0 | 1 |

| Swelling | 32 | 11 | 2 | 0 |

| Feeling facial tightness | 41 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Numbness | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stinging | 44 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Burning | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Throbbing | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tingling | 43 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Itching | 44 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Feeling tired | 44 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Feeling feverish | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Feeling lightheaded | 43 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Headaches | 40 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Pain | 42 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

Changes in Patient-Reported Outcomes (FACE-Q) at 1 month

Patients experienced a statistically significant improvement in all FACE-Q domains assessed (Table 2). Aging appearance appraisal improved from 49.7 ± 29.4 to 70.1 ± 21.6 (+20.4, p < 0.001), with an effect size of 0.79. Psychological well-being improved from 44.0 ± 14.6 to 78.6 ± 20.7 (+34.6, p < 0.001) with an effect size of 1.93. Social functional scale improved from 48.6 ± 16.6 to 75.5 ± 21.7 (+26.9, p < 0.001) with an effect size of 1.20. Satisfaction with facial appearance improved from 50.1 ± 13.7 to 66.2 ± 19.7 (+16.1, p < 0.001) with an effect size of 0.95. Effect sizes were calculated to assess for improvements for each scale from pre-procedure to post-procedure. The magnitude of change was interpreted using published data for the FACE-Q of Cohen’s arbitrary criteria (small 0.20, moderate 0.50, large 0.80).[16,10,7,8]. The magnitude of change in aging appearance appraisal was moderate, whereas for psychological well-being, social functional scale and satisfaction with facial appearance the magnitude of change was large. At 1-month, patient’s overall satisfaction with outcome and decision were 75.8 ± 20.7 and 81.1 ± 20.4 respectively. No patients had complications beyond 1 week based on review of all patient charts at 1 month. Additionally, no patients returned for a touch up procedure within the study period.

DISCUSSION

Nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures with neuromodulators and soft-tissue fillers remain the most requested and prevalent aesthetic procedures in the United States.[1] Therefore, integrating these procedures in plastic surgery residency is essential to training comprehensively skilled and safe aesthetic surgeons. To date, there has been limited data on the safety of nonsurgical facial aesthetic procedures performed by plastic surgery residents and limited data on patient satisfaction with these procedures, prompting a call for future studies to include these data by the ACAPS Aesthetic Surgery task force.[5] In this study, we demonstrated patients who underwent nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures with neuromodulators and/or with soft-tissue fillers experienced large changes in satisfaction with facial appearance and significant improvements in all domains of health-related quality of life measured with the FACE-Q, a validated patient-reported outcome measure. Furthermore, our study demonstrates that plastic surgery residents can perform nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures, under supervision, without compromising patient safety. No patient in our series experienced complications during the follow-up period and a majority of patients had “no” or “little” symptoms on the Early Recovery Symptom and Early Life Impact module of the FACE-Q. Overall, this study expands the literature on aesthetic surgery education and is the most comprehensive study to date on outcomes with resident-performed nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures.

The model for nonsurgical facial rejuvenation training reported in this study can be incorporated into residency programs across the United States and potentially address previously identified disparities in aesthetic surgery training. In 2015, it was reported that some plastic surgery programs were unable to meet minimum requirements for neuromodulator and soft-tissue filler procedures.[3] Furthermore, there continue to be widespread disparities in exposure to, and experience with, aesthetic surgery procedures in plastic surgery residency training programs nationwide.[5,17,12,3] Many leaders in aesthetic surgery have argued for improved resident exposure to aesthetic procedures to ensure trainees are prepared to practice independently with comprehensive competency in aesthetic surgery.[5,18] A recent publication highlighted the operational structure, outcomes, and safety of a resident cosmetic clinic to augment residents’ surgical aesthetic training.[12] This study expands on that experience and reports on the operational structure, safety, and patient-reported outcomes associated with a nonsurgical facial rejuvenation clinic. We recruit patients for facial rejuvenation procedures through our weekly resident cosmetic clinic and by hosting a resident nonsurgical procedures only clinic every 6 months. In keeping with best practice guidelines from ACAPS, these clinics are supervised by full time academic aesthetic surgery faculty and a medical director and supported by nursing staff.[5] Furthermore, longitudinal care is provided and outcomes are tracked. There is only one prior study evaluating outcomes with resident performed nonsurgical facial rejuvenation.[9] Although this study was an important first step in considering the safety and outcomes of resident-performed procedures, it was limited by a small sample size (11 patients) and by short-term follow-up (1 week). Furthermore, the FACE-Q has subsequently evolved to include a more comprehensive assessment of patient perceptions of satisfaction and health-related quality of life following aesthetic procedures.[6,10,7,8] Our study builds on this prior work by reporting 1-month outcomes and incorporating validated patient-reported outcome measures.

In this study, we demonstrated statistically and clinically significant improvements in all domains of health-related quality of life measured by the FACE-Q. Patients who underwent nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures performed by a plastic surgery resident experienced large changes in satisfaction with facial appearance and moderate changes in appraisal of aging appearance. Studies looking at satisfaction with facial appearance after different neurotoxin injections demonstrate similar improvements to what was observed in our study.[19] Prior studies in the dermatology literature have demonstrated the effect size for moderate changes in satisfaction with facial appearance for patients undergoing nonsurgical facial rejuvenation.[20] However validation studies of the aging appearance appraisal were previously limited to patients undergoing aesthetic facial surgery.[7]

Initial validation studies of FACE-Q modules included a mixed cohort, including patients undergoing surgical and nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures; therefore making it difficult to compare our results to these studies.[10] In the validation studies performed by Klassen et al., patients who had neurotoxin and/or soft-tissue fillers were included, albeit only accounting for 5.3% in one study.[10] Patients in these studies had early life impact scores, which assess how patients feel after their procedure in regards to eating, drinking, sleeping, and comfort in social situations, at 7 days of 65.2 ± 17.9.[10] Higher scores translate to better quality of life or greater satisfaction. The social functioning scale evaluates a patient’s social life with first impressions, friendships, and interactions with new people. The psychological well-being scale assesses emotional health, including happiness, confidence, and sense of control.[10,8] Social functioning and psychological well-being had an effect size, at 30 days, of 0. 2 (small according to Cohen’s arbitrary criteria) in the FACE-Q validation studies.[10] In our study, patients had an early life impact score of 95.8 ± 7.1, indicating high levels of health-related quality of life after nonsurgical facial aesthetic procedures performed by a plastic surgery resident. Additionally, effect sizes for social functioning and psychological well-being were 1.20 and 1.93 at 30 days, indicating large improvements in patient’s social life and emotional health.

Satisfaction with outcome and satisfaction with decision assess the process of care. The first globally assesses the patient’s appraisal of satisfaction with their procedure, while satisfaction with decision assesses the decision to have the procedure done, and includes an assessment of whether the procedure was worth undergoing. No study to date has specifically assessed these domains with neuromodulators and/or soft-tissue filler. The FACE-Q validation studies for these domains had values at 30 days of 62.5 ± 21.1 for satisfaction with outcome and 73.1 ± 23.1 for satisfaction with decision.[10] In the present study, satisfaction with outcome was 75.8 ± 20.7, whereas satisfaction with decision was 81.1 ± 20.4 at 30 days post-procedure. These values demonstrate a high level of satisfaction by patients. However, because patients in the study did not pay for their procedure or incur any cost of the product, this remains a potential confounder of the assessment of satisfaction with decision score.

We assessed patient complications and recovery through assessment of early recovery symptoms and chart review. A majority of patients had “no” symptoms or “a little” symptoms as defined in the early recovery symptoms module of the FACE-Q. Patients who did experience symptoms most commonly had bruising, tenderness, swelling and soreness after injection with neuromodulator and/or soft-tissue filler by a plastic surgery resident. Because evaluation of these known sequelae of injections is not standardized, comparisons of our experience to others is difficult for the early time point. However, no patient in our series had complications at 30-days post-procedure, including no patient with vascular, infectious or technical complications. Indeed, both neuromodulator and soft-tissue filler have known and potentially devastating complications, including brow or eyelid ptosis, skin necrosis, nodule formation, and even blindness.[14,15] Additionally, as a part of the study, patients had the option to return for any touch up procedure due to asymmetry or incomplete correction. No patient availed this option. In our experience, the absence of these complications and our training model suggest that plastic surgery residents can be taught to perform nonsurgical facial aesthetic procedures with injectables without compromising patient safety and quality outcomes.

Our study is not without limitations. Patients in this study received neuromodulator and/or soft-tissue filler at no cost. The perceived benefit or lack of satisfaction associated with the cost of product could have impacted the results of our study. However, the purpose of our study was to assess outcomes and safety within the confines of an educational, training model. Our resident clinic does not offer facial rejuvenation with these products at a cost. In this study, we aimed to investigate patient-reported outcomes, and given the limited duration of follow-up and nature of the clinic, we were not able to have a third party objectively evaluate aesthetic improvements in patients. Although patient-reported outcomes may serve as a proxy measure for aesthetic improvement, we acknowledge the value of objective assessments, in addition to patient-reported outcomes, in future studies. An additional limitation of this study is that we were not powered to detect differences between groups of residents (junior versus senior residents) or between different anatomical locations. In the future, we believe multi-center studies that collect and pool data across institutions will provide a sufficient number of patients to allow for these comparisons. Another limitation of this study is our follow-up is limited to 30 days. Although most complications and adverse events associated with injectables occur within this period, future studies with a longer follow-up period are warranted to evaluate the stability of aesthetic outcome over time.

CONCLUSIONS

Facial rejuvenation with nonsurgical procedures, including neuromodulators and soft-tissue fillers, can be performed by residents and provide high levels of satisfaction and improvements in multiple domains of health-related quality of life without compromising patient safety. Integrating nonsurgical facial rejuvenation procedures in plastic surgery residency is essential to training comprehensively skilled and safe aesthetic surgeons. The model for nonsurgical facial rejuvenation training reported in this study can be utilized by residency programs across the United States and potentially address disparities in aesthetic surgery training that currently exist.

Table 3.

Pre-procedure and post-procedure FACE-Q scores by domain at 1 month

| FACE-Q Domain | Pre-procedure Score (mean ± SD) | Post-procedure Score (mean ± SD) | Mean Difference | P value | Effect Size | Magnitude of Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aging appearance appraisal | 49.7 ± 29.4 | 70.1 ± 21.6 | 20.4 | < 0.001 | 0.79 | Moderate |

| Psychological well-being | 44.0 ± 14.6 | 78.6 ± 20.7 | 34.6 | < 0.001 | 1.93 | Large |

| Social functional scale | 48.6 ± 16.6 | 75.5 ± 21.7 | 26.9 | < 0.001 | 1.20 | Large |

| Satisfaction with facial appearance | 50.1 ± 13.7 | 66.2 ± 19.7 | 16.1 | < 0.001 | 0.95 | Large |

Table 4.

FACE-Q domains only assessed at 1 month post-procedure

| FACE-Q Domain | Score (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| Satisfaction with outcome | 75.8 ± 20.7 |

| Satisfaction with decision | 81.1 ± 20.4 |

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

MMT and TMM receive research grant support and consulting fees from Allergan unrelated to this study. All other authors have nothing to disclose. No financial support was directly provided for this study. Product for injection used in this study was obtained through educational training grants from Allergan© and Merz©. RPP is supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Institutional Research Training Grant, T32CA190194 (PI: Colditz). The content presented in this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Society of Plastic Surgeons (2016) ASPS Procedural Statistics. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics. Accessed 03/01/2017

- 2.American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2016) Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics. http://www.surgery.org/sites/default/files/ASAPS-Stats2016.pdf. Accessed 03/01/2017 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Silvestre J, Serletti JM, Chang B (2016) Disparities in Aesthetic Procedures Performed by Plastic Surgery Residents. Aesthetic surgery journal. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qureshi AA, Tenenbaum MM (2016) Commentary on: Disparities in Aesthetic Procedures Performed by Plastic Surgery Residents. Aesthetic surgery journal. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hultman CS, Wu C, Bentz ML, Redett RJ, Shack RB, David LR, Taub PJ, Janis JE (2015) Identification of Best Practices for Resident Aesthetic Clinics in Plastic Surgery Training: The ACAPS National Survey. Plastic and reconstructive surgery Global open 3 (3):e370. doi: 10.1097/01.gox.0000464864.49568.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Alderman A, East C, Badia L, Baker SB, Robson S, Pusic AL (2016) Self-Report Scales to Measure Expectations and Appearance-Related Psychosocial Distress in Patients Seeking Cosmetic Treatments. Aesthetic surgery journal 36 (9): 1068–1078. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panchapakesan V, Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Scott AM, Pusic AL (2013) Development and psychometric evaluation of the FACE-Q Aging Appraisal Scale and Patient-Perceived Age Visual Analog Scale. Aesthetic surgery journal 33 (8):1099–1109. doi: 10.1177/1090820x13510170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Cano SJ (2013) Development and psychometric evaluation of the FACE-Q satisfaction with appearance scale: a new patient-reported outcome instrument for facial aesthetics patients. Clinics in plastic surgery 40 (2):249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iorio ML, Stolle E, Brown BJ, Christian CB, Baker SB (2012) Plastic surgery training: evaluating patient satisfaction with facial fillers in a resident clinic. Aesthetic plastic surgery 36 (6): 1361–1366. doi: 10.1007/s00266-012-9973-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Schwitzer JA, Scott AM, Pusic AL (2015) FACE-Q scales for health-related quality of life, early life impact, satisfaction with outcomes, and decision to have treatment: development and validation. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 135 (2):375–386. doi: 10.1097/prs.0000000000000895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinno S, Schwitzer J, Anzai L, Thorne CH (2015) Face-Lift Satisfaction Using the FACE-Q. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 136 (2):239–242. doi: 10.1097/prs.0000000000001412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qureshi AA, Parikh RP, Myckatyn TM, Tenenbaum MM (2016) Resident Cosmetic Clinic: Practice Patterns, Safety, and Outcomes at an Academic Plastic Surgery Institution. Aesthetic surgery journal 36 (9):Np273–280. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics 42 (2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLorenzi C (2013) Complications of injectable fillers, part I. Aesthetic surgery journal 33 (4):561–575. doi: 10.1177/1090820x13484492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLorenzi C (2014) Complications of injectable fillers, part 2: vascular complications. Aesthetic surgery journal 34 (4):584–600. doi: 10.1177/1090820x14525035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen J (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences 2nd edn Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neaman KC, Hill BC, Ebner B, Ford RD (2010) Plastic surgery chief resident clinics: the current state of affairs. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 126 (2):626–633. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181df648c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald R, Graivier MH, Kane M, Lorenc ZP, Vleggaar D, Werschler WP, Kenkel JM (2010) Appropriate selection and application of nonsurgical facial rejuvenation agents and procedures: panel consensus recommendations. Aesthetic surgery journal 30 Suppl:36s–45s. doi: 10.1177/1090820x10378697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang BL, Wilson AJ, Taglienti AJ, Chang CS, Folsom N, Percec I (2016) Patient Perceived Benefit in Facial Aesthetic Procedures: FACE-Q as a Tool to Study Botulinum Toxin Injection Outcomes. Aesthetic surgery journal 36 (7):810–820. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjv244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hibler BP, Schwitzer J, Rossi AM (2016) Assessing Improvement of Facial Appearance and Quality of Life after Minimally-Invasive Cosmetic Dermatology Procedures Using the FACE-Q Scales. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD 15 (1):62–67 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]