Abstract

The study of mechanisms by which animals tolerate environmental extremes may provide strategies for preservation of living mammalian materials. Animals employ a variety of compounds to enhance their survival, including production of disaccharides, glycerol, and anti-freeze compounds. The cryoprotectant glycerol was discovered before its role in amphibian survival. In the last decade, trehalose has made an impact on freezing and drying methods for mammalian cells. Investigation of disaccharides was stimulated by the variety of organisms that tolerate dehydration stress by accumulation of disaccharides. Several methods have been developed for the loading of trehalose into mammalian cells, including inducing membrane lipid-phase transitions, genetically engineered pores, endocytosis, and prolonged cell culture with trehalose. In contrast, the many antifreeze proteins (AFPs) identified in a variety of organisms have had little impact. The first AFPs to be discovered were found in cold water fish; their AFPs have not found a medical application. Insect AFPs function by similar mechanisms, but they are more active and recombinant AFPs may offer the best opportunity for success in medical applications. For example, in contrast to fish AFPs, transgenic organisms expressing insect AFPs exhibit reduced ice nucleation. However, we must remember that nature’s survival strategies may include production of AFPs, antifreeze glycolipids, ice nucleators, polyols, disaccharides, depletion of ice nucleators, and partial desiccation in synchrony with the onset of winter. We anticipate that it is only by combining several natural low temperature survival strategies that the full potential benefits for mammalian cell survival and medical applications can be achieved.

Keywords: Cryopreservation, Cryobiology, Antifreeze proteins, Trehalose, Polyols, Nucleation, Dehydration

Introduction

Cryobiology may be defined as the study of the effects of temperatures lower than normal physiologic ranges upon biologic systems and cryopreservation as the storage of biomaterials below the temperature of ice nucleation. Simply freezing mammalian cells and tissues usually results in dead, nonfunctional materials. Although many types of isolated mammalian cells and small aggregates of cells can be frozen by following published procedures, obtaining reproducible results for many cell types and more complex tissues is still the subject of extensive investigation employing scientific method based upon our current understanding of the chemistry, physics, and toxicology of cryobiology (Karow 1981; Mazur 1984; Brockbank 1995, Brockbank and Taylor 2007). There is another investigative strategy that was well expressed by Harry Merryman (2004), “Mother Nature has the advantage of an extended life expectancy and has made good use of it. The number of her trials and errors defies imagination, and the countless successes are all here before us, potentially revealing not only how but sometimes the why as well. In the absence of a complete understanding of the events at the most basic level, it may be more fruitful at this time, in the interest of applications, to build on what Nature has already discovered rather than to engage in independent trial and error without the advantage of a few billion years to do it in.”

Nature employs a variety of compounds and strategies to enhance the survival of ectothermic animals during extreme environmental conditions (Fig. 1). There are two general categories of adaptations (Lee 2010). Some organisms are freeze-tolerant, meaning they can survive freezing, generally only in extracellular fluid compartments. Non-freeze-tolerant animals must become freeze avoiding to temperatures below those experienced in winter. Actually, how most animals survive freezing conditions is not known, as only a small percentage of cold-tolerant species have been studied. Generally, a suite of adaptations is required to achieve cold tolerance, and these vary from species to species, even within a closely related group. Adaptations may include production of high concentrations of polyols (particularly glycerol, glucose, disaccharides (particularly trehalose)) and a variety of thermal hysteresis producing antifreeze compounds. Many freeze-tolerant insects have proteins and lipoproteins with ice nucleation activity in their extracellular fluid to prevent supercooling that may result in rapid, uncontrolled freezing and lethal intracellular ice (Zachariassen and Hammel 1976; Duman et al. 1985; Duman 2001; Duman et al. 2010). The purpose of this brief overview is to demonstrate what we have learned from Nature to date and to indicate some exciting future biomedical research opportunities based upon Nature’s strategies for surviving extreme environmental conditions.

Figure 1.

Selected lessons from nature.

Polyols.

Gray tree frogs and the Siberian salamander are freeze-tolerant and they employ glycerol as a strategy to survive subzero temperatures (Storey and Storey 2004) in response to environmental cues before freezing occurs. In addition to glycerol, some animals accumulate sorbitol, ribitol, erythritol, threitol, and/or ethylene glycol as the environmental conditions of winter approach (Storey and Storey 1991). Glycerol, ethylene glycol, and polyethylene glycol have been employed for biomedical cryopreservation applications in the literature. Indeed, little advance was made in the field of cryopreservation until an accidental discovery of the cryoprotective properties of glycerol for biological materials during freezing (Polge et al. 1949). Glycerol has since become one of the most commonly employed cryoprotectants for mammalian cells. Subsequently, glycerol’s role in Nature was discovered, but it’s too late for it to inspire biomedical preservation applications.

Glucose.

Frogs, particularly wood frogs, employ glucose as a means of avoiding freezing damage. There have been few significant reports of mammalian cell preservation with glucose inspired by this observation. Glucose is often a component of cryopreservation formulations, but it is not usually one of the primary cryoprotective agents. However, a glycerol–glucose method for platelet preservation has been reported (Redmond et al. 1983). Glucose has also been reported to improve dimethylsulfoxide-cryopreserved hepatocyte viability immediately on thawing, but it failed to affect cell attachment and survival in culture (Miyamoto et al. 2006). In contrast, di-, tri-, tetra-, and oligosaccharides as cryoprotectants effectively improved both cell viability and attachment. One of the most interesting glucose-inspired studies was by Norris et al. (2006) who reported that a form of glucose that is accumulated but not metabolized by mammalian cells, 3-O-methyl-D-glucose, improves desiccation tolerance of keratinocytes. (Norris et al. 2006) In contrast, neither glucose alone nor 2-deoxy glucose, which is also accumulated by mammalian cells without metabolism, had significant survival benefits.

Disaccharides.

Nature has developed a wide variety of organisms and animals that tolerate dehydration stress by accumulation of large amounts of disaccharides, especially trehalose and sucrose, including plant seeds, bacteria, insects, yeast, brine shrimp, fungi and their spores, cysts of certain crustaceans, and some soil-dwelling animals (reviewed, Crowe et al. 2007). The protective effects of trehalose and sucrose may be classified under two general mechanisms: (1) “the water replacement hypothesis” or stabilization of biological membranes and proteins by direct interaction of sugars with polar residues through hydrogen bonding, and (2) stable glass formation (vitrification) by sugars in the dry state. The stabilizing effect of these sugars has also been shown in a number of model systems, including liposomes, membranes, viral particles, and proteins during dry storage at ambient temperatures. On the other hand, the use of these sugars in mammalian cells has been somewhat limited mainly because mammalian cell membranes are impermeable to disaccharides or larger sugars. There is strong evidence that sugars need to be present on both sides of the cell membrane in order to preserve the cells during dehydration.

Multiple methods have been developed for the loading of sugars into living cells. For the sake of brevity, we have focused on trehalose. One successful strategy developed by the Crowe group involved introduction of trehalose into human pancreatic islet cells during a cell membrane thermotropic lipid-phase transition, prior to freezing, in the presence of a mixture of 2 M dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and trehalose (Beattie et al. 1997). Toner’s group employed microinjection for trehalose delivery into oocytes followed by successful preservation (Eroglu et al. 2002) and they also used a novel genetically modified endotoxin-derived pore to reversibly permeabilize mammalian cells to sugars, and 0.2 M trehalose-loaded fibroblasts and keratinocytes were successfully frozen and thawed in the absence of any other cryoprotectants (Eroglu et al. 2000). Platelets have been preserved by freeze-drying them with trehalose with a survival rate of 85% (Wolkers et al. 2001). Trehalose was rapidly taken up by human platelets at 37°C by fluid-phase endocytosis. This method of platelet preservation has been the subject of further research and is being commercialized.

Oliver’s results suggest that human MSCs are capable of loading trehalose from the extracellular space by a clathrin-dependent fluid-phase endocytotic mechanism that is microtubule-dependent but actin-independent (Oliver et al. 2004). Mondal (2009) preserved Madin Darby bovine kidney cells by freezing and storage at −80°C after trehalose loading using a combination of fluid-phase endocytosis and heat shock at 40°C (Mondal 2009). The loaded cells demonstrated a gradual decrease to 50% viability over 180 d of storage. We have discovered that prolonged incubation of endothelial cells with trehalose under normal cell culture conditions enables cryopreservation in the absence of any other cryoprotectant (Brockbank et al. 2007).

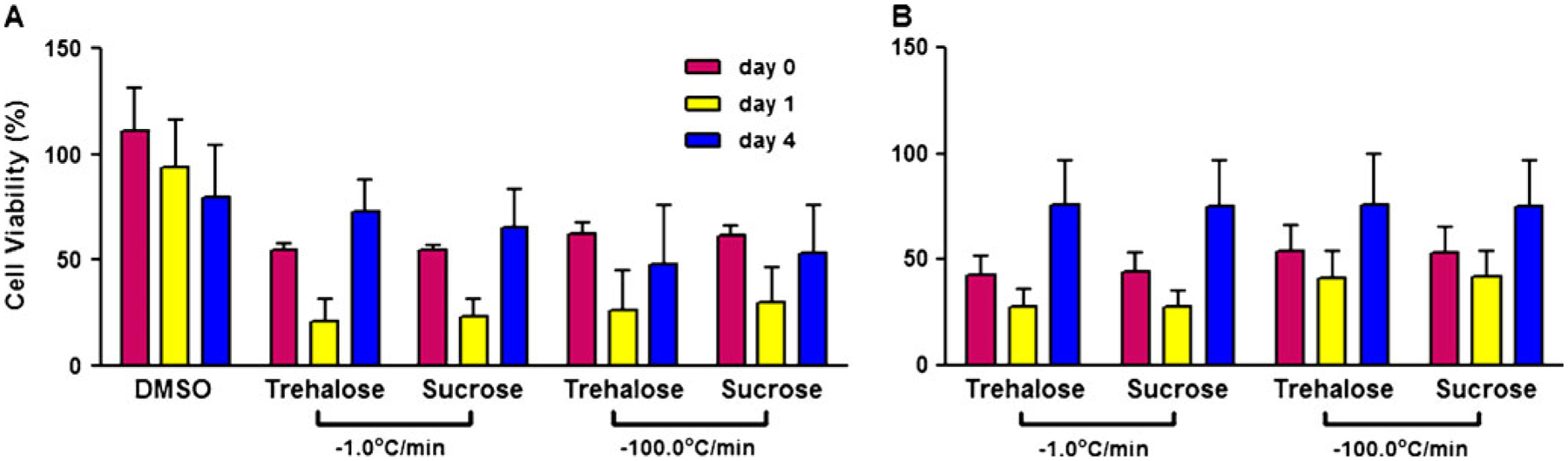

Another disaccharide loading strategy for cryopreservation and freeze-drying is use of an endogenous cell surface receptor present on some mammalian cells (Buchanan et al. 2005). The process involves the reversible switching of a naturally occurring P2X7 receptor present on hemopoietic stem cells. When ATP4− binds to the receptor, a non-specific pore is formed that allows molecules (<900 Da) to pass through. The receptor selectively binds adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and its activity is dependent on temperature, pH, and the concentration of divalent cations such as Mg2+.Closure of the pore after activation by ATP is achieved by simply removing ATP from the system or by adding exogenous Mg2+ that has a high affinity for the active form of ATP, namely ATP4−. We have exposed cells to ATP with trehalose for 1 h followed by a tenfold dilution of the ATP and inactivation of the active form of ATP (ATP 4−) by the addition of 1 mM MgCl2 followed by a 1-h recovery period at 37°C. When the cells were compared to an untreated control, cells cryopreserved with 10% DMSO demonstrated a greater initial viability close to 100% that steadily declined over days in culture postthaw. Figure 2 shows cells cryopreserved in trehalose or sucrose demonstrated initial viabilities between 50% and 60%. After a small drop in activity the next d, the viability of the cells by day 4 had improved and was equivalent or better than the initial viability measured immediately postthaw. Also observed was that the viability measured at day 4 from cells cryopreserved in sugars was nearly equal to the viability of cells cryopreserved in DMSO. This is more clearly seen when percent viability was calculated based on the DMSO control. On day 4 of culture, cells cryopreserved with sugars were at least 75% or better than their matched DMSO controls (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Viability of TF-1 cells after cryopreservation. TF-1 cells were porated with ATP and loaded with 0.2 M trehalose or sucrose before being cryopreserved at the indicated cooling rates in 0.8 M trehalose or sucrose. Upon thawing, cell metabolic activity was measured for consecutive days postthaw using alamarBlue. Percent viability was calculated based on an untreated control (A) or on time in culture matched control cells cryopreserved with 10% DMSO (B) and presented as the mean (±SEM) of nine replicates.

In addition to measuring metabolic activity, the cryopreserved TF-1 cells were also subjected to the 14-d colony-forming assay to evaluate their ability to form colonies as compared with cells cryopreserved using DMSO. As can be seen in Table 1, colony formation was equivalent for DMSO- and trehalose-preserved cells. Sucrose was also very effective and the results suggest that development of DMSO-free cryopreservation methods independent of cooling rate may be feasible with either disaccharide.

Table 1.

Colonies 14 d after cryopreservation of TF-1 cells

| Cooling rate | CPA | Cell recovery (mean±1SE) | Colony-forming units (mean±1SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| −1.0°C/min | DMSO | 1.53×105±2.70×104 | 288.50±143.50 |

| Trehalose | 1.25×105±2.67×104 | 310.25±109.98 | |

| Sucrose | 1.42×105±8.35×103 | 150.25±29.02 | |

| −100.0°C/min | Trehalose | 1.17×105±8.20×103 | 360.75±92.31 |

| sucrose | 1.10×105±1.10×104 | 242.25±80.29 |

Trehalose research, inspired by Nature, is making significant progress for preservation of mammalian cells. Several methods have been developed to get trehalose into mammalian cells, which work for specific cell types, but there is no single method that works for them all. Once trehalose is on the inside of mammalian cells, preservation is possible.

Thermal hysteresis antifreeze compounds.

Antifreeze proteins (AFPs) have the ability to lower the non-colligative freezing point of water while not affecting the melting point, thereby producing a characteristic difference between the freezing point and the colligative (equilibrium) melting point termed thermal hysteresis (DeVries 1986). In addition, AFPs can inhibit ice nucleators and modify ice structure (i.e., inhibit recrystallization) and the response of organisms to harsh environments. The antifreeze molecules are diverse in structure and have been identified in a variety of organisms including fish, insects, and other terrestrial arthropods, plants, fungi, and bacteria (DeVries 1971; Duman and Olsen 1993; Duman 2001; Cheng and Devries 2002; Duman et al. 2004; Griffith and Yaish 2004). The first to be discovered and best characterized are the antifreeze glycoproteins (AFGPs) (DeVries and Wohlschlag 1969; DeVries 1971, 2004) and proteins (AFPs) found in fish from ice-laden marine waters. These include the AFGPs of Antarctic nototheniids and northern cod (Gadid) fish species and five additional, structurally different types of AFPs (Jia and Davies 2002; DeVries 2004). The fish-derived antifreeze molecules are thought to adsorb preferentially to the prism face of ice or to internal planes that also result in inhibition of ice crystal growth perpendicular to the prism face (Raymond and DeVries 1977; Raymond et al. 1989; Jia and Davies 2002). The insect AFPs function by similar mechanisms, but at least some bind to both the prism and basal planes of ice (Graether and Sykes 2004; Petraya et al. 2008). Therefore, they are the most active AFPs, and consequently, may offer the best opportunity for success in applications. For example, although a number of transgenic plants and animals have been produced that express fish AFPs, none have exhibited any advantage over wild-type as regards cold tolerance. In contrast, both transgenic plants (Arabidopsis thaliana) and Drosophila melanogaster that express AFPs of the beetle Dendroides canadensis exhibited small (1–3°C) but significantly reduced nucleation temperatures (Huang et al. 2002; Nicodemus et al. 2006; Lin et al. 2010). Recently, an antifreeze glycolipid (AFGL) has been discovered in the freeze-tolerant Alaskan beetle Upis ceramboides (Walters et al. 2009). This AFGL is the only non-protein known to produce thermal hysteresis in organisms.

AFPs function in freeze-avoiding animals to prevent freezing from inoculation initiated by external ice across the body surface and by inhibition of ice nucleators (Duman 2001; Duman et al. 2010). However, in body fluids of freeze-avoiding species, thermal hysteresis is, at most, typically only a few tenths of a degree or less. In some freeze-tolerant species, there might not be a measurable thermal hysteresis, but only changed ice crystal morphology and/or recrystallization inhibition (Griffith and Yaish 2004). The term ice-active proteins (IAPs) is sometimes used (Wharton et al. 2009) to include proteins that function as true AFPs (those IAPs with greater THA) that actually function as antifreezes, as well as those IAPs in freeze-tolerant organisms that only produce low thermal hysteresis (a few tenths of a degree C), changes in ice crystal morphology, and/or recrystallization inhibition. The physiological function(s) of IAPs in freeze tolerance is not well understood (Duman et al. 2010). Recrystallization inhibition and perhaps changes in ice crystal morphology are likely functions of IAPs that are free in solution. However, there is evidence that some IAPs in animals may be present on cell membranes where they may function to inhibit the lethal spread of extracellular ice into the cytoplasm. This is almost certainly the case with the AFGL from the U. ceramboides beetles as nearly all the AFGL is present on membranes (Walters et al. 2009).

An unexpected function of the fish AFGPs and type-1 AFP from winter flounder is membrane stabilization at low temperature (Tonczak and Crowe 2002). It is not known if other AFPs or the AFGL have a similar effect on membranes.

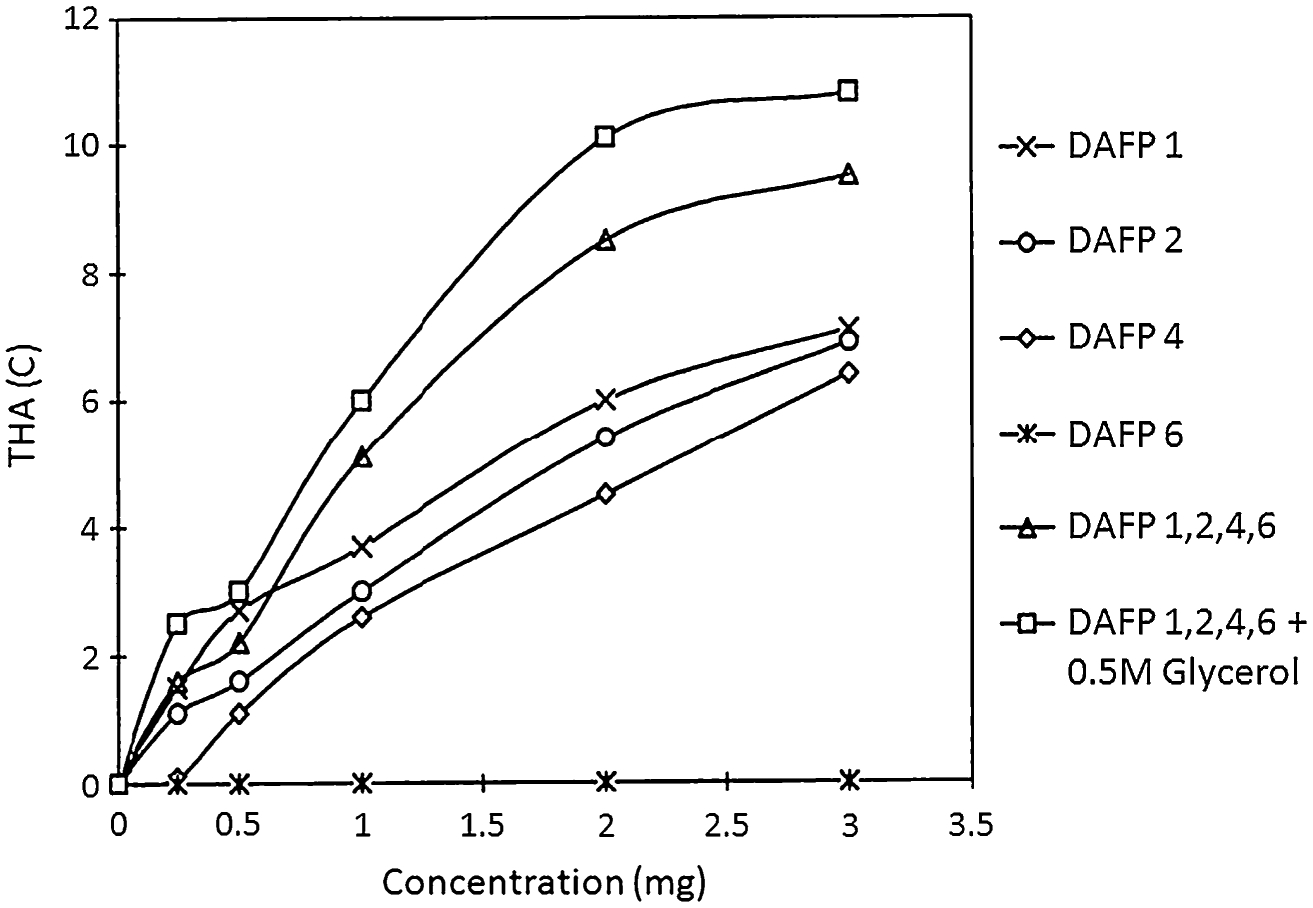

AFPs have been reported to protect single mammalian cells and embryos at subzero temperatures. Examples include cryoprotection of immature oocytes and two cell embryos of mice and pigs (Rubinsky et al. 1991a, b, 1992), bovine and ovine embryos at morula/blastocyst stage (Arav et al. 1993), and cryoprotection of chimpanzee sperm (Younis et al. 1998). Conversely, several experiments cast a doubt on the cryoprotective effect of AFPs, as no benefit has been demonstrated by addition of AFPs to cryopreserved equine embryos (Langeaux et al. 1997) and human red blood cells in glycerol (Pegg 1992). Cryoprotection of solid organs using AFGPs has been performed on rat livers and hearts. Successful isolated rat livers subzero preservation has been performed by Lee et al. (1992). Rat livers perfused with AFGP in Krebs solution before hypothermic storage had a higher rate of bile production and less enzyme leakage upon reperfusion compared with livers not perfused with AFGP. Whole rat livers frozen to −3°C protected by glycerol and AFGP had increased bile production and less hepatocyte structural damage compared with livers preserved with glycerol alone (Rubinsky et al. 1994). Cryopreservation of cardiomyocytes or hearts using anti-freeze proteins has been unsuccessful. Mugnano et al. (1995) examined the effect AFGP on freezing (−4°C) of cardiomyocytes. Using cryomicroscopy, they demonstrated that in the solution frozen without AFGP, large blunt crystals were formed excluding most cardiomyocytes from the plane of ice formation. After thawing, the cells appeared similar to unfrozen cells. Spicular ice formed rapidly in the presence of 10 mg/ml AFGP and needle-like crystals appeared to penetrate the cardiomyocytes, resulting in intracellular freezing followed by cell lysis. Wang et al. (1994) evaluated subzero cryopreservation of rat hearts using the Langendorff in vitro model of working isolated rat hearts. Cardiac explants were preserved using AFGP at different concentrations at subzero temperatures of −1.4°C. Hearts that were preserved for 3 h at concentrations of 10 mg/ml AFGP failed to beat upon reperfusion. The authors found that AFGPs were deleterious to the isolated rat hearts in a dose-dependent manner exacerbating the damage caused by freezing. Amir et al. (2003) reported successful subzero preservation of mammalian hearts using fish AFP I and AFP III in an in vivo heterotopic heart transplantation model. All hearts preserved at subzero temperatures using AFP I or AFP III survived, displaying good to excellent viability scores. They believed that the key to their success was maintaining preservation temperatures without freezing. Once freezing occurred, the hearts were irreversibly damaged. Preservation target temperatures and AFP I and III concentrations in their experiments were determined according to preliminary experiments, in which AFP thermal hysteresis activity curves in storage solution were plotted in order to achieve a supercooled solution without freezing. Electron microscopy studies demonstrated that antifreeze proteins prevented the damage caused by freezing, which correlated well with the post-transplant hemodynamic heart performance. This group followed up on this study in which hearts were preserved at −1.1 to −1.3°C for 6 h (Amir et al. 2003) with another study in which they evaluated whether lowering the temperature could increase the preservation time of a mammalian (rat) heart and whether prolonged subzero preservation using AFPs may improve the viability of harvested hearts compared to hearts preserved using standard techniques at +4°C (Amir et al. 2004). They were able to demonstrate, using an in vitro Langendorff perfusion system, that AFPs prevent freezing and improve survival in prolonged subzero preservation of rat hearts. Developed pressures of hearts preserved at subzero temperatures using AFP III were significantly better than those preserved using standard preservation techniques at +4°C (refrigerator temperature, range +2°C to +8°C). These studies, although not conclusive, combine to suggest that storage of living materials below +4°C may have significant advantages over +4°C. However, fish-derived AFPs provide only a low level of thermal hysteresis (maximum of ~2°C). In marked contrast, combinations of insect-derived AFPs provide thermal hysteresis activities of 10°C to 12°C and perhaps even more (Fig. 3, Wang and Duman 2006).

Figure 3.

Thermal hysteresis activity (THA in °C) of D. canadensis-derived AFP types 1, 2, 4, and 6 alone or in combination (mgs/mL) with and without glycerol (Wang and Duman 2005).

Based upon the hypothesis that naturally occurring AFPs could be used to limit problems associated with ice formation during cryopreservation (Knight and Duman 1986), we have previously investigated the role of fish-derived AFP Type I in cryopreservation by freezing (Hansen et al. 1993). Although this natural compound inhibited ice recrystallization in the extracellular milieu of cells, it increased ice crystal growth associated with the cells and resulted in AFP concentration-dependent cell losses compared to untreated control cultures. More recently in unpublished studies, we have combined naturally occurring fish-derived antifreeze compounds and cryoprotectants in an attempt to minimize ice damage during freezing or risk of ice formation during vitrification. We observed physical changes in ice form but failed to improve cell/tissue viability. More effective insect-derived AFPs are now available (Fig. 3). These AFPs are derived from beetles, such as the larvae of D. canadensis that produce a family of 13 AFPs which have much greater effects on ice formation than fish-derived AFPs (up to an order of magnitude greater thermal hysteresis; Duman et al. 1998; Andorfer and Duman 2000; Graether and Sykes 2004; Duman et al. 2010). In the case of another beetle, Cucujus clavipes, there has been documented survival of organisms to −100°C without freezing (Bennett et al. 2005; Sformo et al. 2010) and it is suspected that they deep supercool and vitrify naturally by dehydrating to 28–40% body water, concentrating glycerol, and producing AFPs similar to those of D. canadensis. It appears likely that these AFPs enhance the ability of Cucujus larvae to deep supercool and vitrify by inhibiting ice nucleators (Sformo et al. 2010), especially when enhanced by other compounds (Duman 2001; Wang and Duman 2005, 2006; Amornwittawat et al. 2008, 2009). AFPs from both these species have been produced in an Escherichia coli expression system. The availability of these recombinant insect-derived AFPs creates a new opportunity for cryopreservation of cells or tissues in which we anticipate that the AFPs may be employed in the cryoprotectant formulations and possibly incorporated in tissue-engineered construct matrices to aid in minimization of ice formation during cryopreservation. The large degree of thermal hysteresis exhibited by insect-derived AFPs in combination with glycerol may enable short-term subzero storage of tissues and organs with minimal risk of ice nucleation (Brockbank et al. 2009). This may enable much longer storage periods for major organs used in medical transplantation procedures due to the greater reduction of metabolic activity compared with short-term storage at 0–4°C on ice or in a refrigerator.

Conclusions

Glycerol, trehalose, and sucrose have already been utilized in cryopreservation strategies with varying degrees of success. Antifreeze proteins and glycoproteins have had minimal benefits for preservation of mammalian cells so far. However, the more we study Nature’s strategies for freeze avoidance and freeze tolerance, the greater the complexity and variety of strategies that are revealed. In addition to the chemicals and antifreeze compounds discussed above, some animals undergo degrees of desiccation, produce AFP-enhancing proteins, nucleate specific body compartments, or isolate themselves from the environmental ice with an impervious waxy coat. It is likely that utilization of lessons learned and to be learned from Nature for low temperature survival strategies is not simply addition of one or the other compound to mammalian cells during storage method development. We anticipate that it is only by combining several low temperature survival strategies from Nature that the full potential benefits for mammalian cell survival can be achieved.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NSF IOB06-18436 to JGD and R44DK081233 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases to KGMB. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Kelvin G. M. Brockbank, Cell & Tissue Systems, Inc., 2231 Technical Parkway, Suite A, North Charleston, SC 29401, USA Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA.

John G. Duman, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA

References

- Amir G; Horowitz L; Rubinsky B; Yousif BS; Lavee J; Smolinskyd AK Subzero nonfreezing cryopreservation of rat hearts using antifreeze protein I and antifreeze protein III. Cryobiology 48: 273–282; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir G; Rubinsky B; Kassif Y; Horowitz L; Smolinsky AK; Lavee J Preservation of myocyte structure and mitochondrial integrity in subzero cryopreservation of mammalian hearts for transplantation using antifreeze proteins—an electron microscopy study. Eur J Cardio Thoracic Surg 24: 292–297; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amornwittawat N; Wang S; Banatlao J; Chung M; Velasco E; Duman JG; Wen X Effects of polyhydroxy compounds on beetle antifreeze protein activity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, Proteins and Proteomics 1794: 341–346; 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amornwittawat N; Wang S; Duman JG; Wen X Polycarboxylates enhance beetle antifreeze protein activity. Biochim Biophys Acta: Proteins Proteomics 1784: 1942–1948; 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andorfer CA; Duman JG Isolation and characterization of cDNA clones encoding antifreeze proteins of the pyrochroid beetle Dendroides canadensis. J Insect Physiol 46: 365–372; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arav A; Ramsbottom G; Baguis A; Rubinsky B; Roche JF; Boland MP Vitrification of bovine and ovine embryos with the MDS technique and antifreeze proteins. Cryobiology 30: 621–622; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beattie GM; Crowe JH; Lopez AD; Cirulli V; Ricordi C; Hayek A Trehalose: a cryoprotectant that enhances recovery and preserves function of human pancreatic islets after long-term storage. Diabetes 46: 519–523; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett VA; Sformo T; Walters K; Toien O; Jeannet K; Hochstrasser R; Pan Q; Serianni AS; Barnes BM; Duman JG Comparative overwintering physiology of Alaska and Indiana populations of the beetle Cucujus clavipes (Fabricus): roles of antifreeze proteins, polyols, dehydration, and diapause. J Exp Biol 208: 4467–4477; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockbank KGM Essentials of cryobiology In: Brockbank KGM (ed) Principles of autologous, allogeneic, and cryopreserved venous transplantation. RG Landes Company, Austin, pp 91–102; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Brockbank KGM; Campbell LH; Ratcliff KM; Sarver KA Method for treatment of cellular materials with sugars prior to preservation. U.S. Patent #7,270,946; 2007.

- Brockbank KGM; Chen Z; Greene ED, Duman JG Anti-freeze proteins enable sub-zero preservation of tissue functions without freezing. Regenerative Medicine: Advancing Next Generation Therapies, abstract. 2009

- Brockbank KGM; Taylor MJ Tissue preservation In: Baust JG (eds) Advances in biopreservation, Chapter 8. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 157–196; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SS; Menze MA; Hand SC; Pyatt DW; Carpenter JF Cell Preserv Technol 3(4): 212–222; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CCM; DeVries AL Origins and evolution of fish antifreeze proteins In: Ewart KV; Hew CL (eds) Fish antifreeze proteins. World Scientific, New Jersey, pp 83–108; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe JH; Crowe LM; Wolkers W; Tsvetkova NM et al. Stabilization of mammalian cells in the dry state. In: Baust JG; Baust JM (eds). CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, Boca Raton, USA, pp 384–411; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AL Glycoproteins as biological antifreeze agents in Antarctic fishes. Science 172: 1152–1155; 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AL Antifreeze glycopeptides and peptides: interactions with ice and water. Meth Enzymol 127: 293–303; 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AL; Wohlschlag DE Freezing resistance in some Antarctic fishes. Science 163: 1073–1075; 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AL. Ice, antifreeze proteins and antifreeze genes in polar fishes In: Barnes BM and Carey HV, eds., Life in the Cold: evolution, mechanism, adaptation and application. University of Alaska Press, Fairbanks, pp. 307–316, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Duman JG Antifreeze and ice nucleator proteins in terrestrial arthropods. Ann Rev Physiol 63: 327–357; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman JG; Bennett VA; Sformo T; Hochstrasser R; Barnes BM Antifreeze proteins in Alaskan insects and spiders. J Insect Physiol 50: 259–266; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman JG; Neven LG; Beals JM; Olsen KR; Castellino FJ Freeze tolerance adaptations, including protein and lipoproten ice nucleators, in larvae of the cranefly Tipula trivittata. J Insect Physiol 31: 1–9; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Duman JG; Olsen TM Thermal hysteresis activity in bacteria, fungi and primitive plants. Cryobiology 30: 322–328; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Duman JG; Parmalee D; Goetz FW; Li N; Wu DW; Benjamin T Molecular characterization and sequencing of antifreeze proteins from larvae of the beetle Dendroides canadensis. J Comp Physiol B 168: 225–232; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman JG; Walters KR; Sformo T; Carrasco MA; Nickell P; Barnes BM Antifreeze and ice nucleator proteins In: Denlinger D, and Lee RE, eds., Low Temperature Biology of Insects. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 59–90; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu A; Russo MJ; Bieganski R; Fowler A; Cheley S; Bayley H; Toner M Intracellular trehalose improves the survival of cryopreserved mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol 18: 163–167; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu A; Toner M; Toth TL Beneficial effect of microinjected trehalose on the cryosurvival of human oocytes. Fertil Steril 77 (1): 152–158; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graether SP; Sykes BD Cold survival in freeze intolerant insects: the structure and function of beta-helical antifreeze proteins. Eur J Biochem 271: 3285–3296; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith M; Yaish MW Antifreeze proteins in plants: a tale of two activities. Trends Plant Sci 9: 399–405; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen TN; Smith KM; Brockbank KGM Type I antifreeze protein attenuates cell recoveries following cryopreservation. Transpl Proc 25(6): 3186–3188; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T; Nicodemus J; Zarka DG; Thomashow MF; Duman JG Expression of an insect (Dendroides canadensis) antifreeze protein in Arabidopsis thaliana results in a decrease in plant freezing temperature. Plant Mol Biol 50: 333–344; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia X; Davies PL Antifreeze proteins: an unusual receptor–ligand interaction. Trends Biochem Sci 27: 101–106; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karow AM Biophysical and chemical considerations in cryopreservation In: Karow AM; Pegg DE (eds) Organ preservation for transplantation. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, pp 113; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Knight CA; Duman JG Inhibition of recrystallization of ice by insect thermal hysteresis proteins: a possible cryoprotective role. Cryobiology 23: 256–262; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Langeaux D; Huhtinen M; Koskinen E; Palmer E Effect of antifreeze protein on the cooling and freezing of equine embryos as measured by DAPI-staining. Equine Vet J 25: 85–87; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY; Rubinsky B; Fletcher GL Hypothermic preservation of whole mammalian liver with antifreeze proteins. Cryo Lett 13: 59–66; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RE A primer on insect cold tolerance In: Denlinger DL, Lee RE (eds) Low temperature biology of insects. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 3–34; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li N; Andorfer CA; Duman JG Enhancement of insect antifreeze protein activity by low molecular weight solutes. J Exp Biol 201: 2243–2251; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X; O’Tousa JE; Duman JG Expression of two self-enhancing antifreeze proteins from Dendroides canadensis in Drosophila melanogaster. J Insect Physiol 56: 341–349; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P Freezing of living cells: mechanisms and implications. Am J Physiol 247(Cell Physiol 16): C125–C142; 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merryman H Foreword In: Fuller BJ; Lane N; Benson EE (eds) Life in the frozen state. CRC Press, Baton Rouge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y; Suzuki S; Nomura K; Enosawa S Improvement of hepatocyte viability after cryopreservation by supplementation of long-chain oligosaccharide in the freezing medium in rats and humans. Cell Transplant 15: 911–919; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal B A simple method for cryopreservation of MDBK cells using trehalose and storage at −80°C. Cell Tissue Bank 10(4): 341–344; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnano JA; Wang T; Layne JR Jr.; De Vries AL; Lee RE Antifreeze glycoproteins promote lethal intracellular freezing of rat cardiomyocytes at high subzero temperatures. Cryobiology 32: 556–557; 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicodemus J; O’Tousa JE; Duman JG Expression of a beetle, Dendroides canadensis, antifreeze protein in Drosophila melanogaster. J Insect Physiol 52: 888–896; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris MM; Aksan A; Sugimachi K; Toner M 3-O-methyl-D-glucose improves desiccation tolerance of keratinocytes. Tissue Eng 12: 1873–1879; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver AE; Jamil K; Crowe JH; Tablin F Loading Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Trehalose by Fluid-Phase Endocytosis. Cell Preserv Technol 2(1): 35–49; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pegg DE Antifreeze proteins. Cryobiology 29: 774–782; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Petraya N; Marshall CB; Celik Y; Davies PL; Braslovsky I Direct visualization of spruce budworm antifreeze protein interacting with ice. Basal plane affinity confers hyperactivity. Biophys J 95: 333–341; 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polge C; Smith AY; Parkes AS Revival of spermatozoa after vitrification and de-hydration at low temperatures. Nature 164: 666; 1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond JA; DeVries AL Adsorption inhibition as a mechanism of freezing resistance in polar fishes. Proceeding Natl Acad Sci USA 74: 2589–2593; 1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond JA; Wilson PW; DeVries AL Inhibition of ice on non-basal planes of ice by fish antifreeze. Proceeding Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 881–885; 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond J; Bolin RB; Cheney BA Glycerol-glucose cryopreservation of platelets. In vivo and in vitro observations. Transfusion 23(3): 213–214; 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsky B; Arav A; De Vries AL Cryopreservation of oocytes using directional cooling and antifreeze glycoproteins. Cryo Lett 12: 93–106; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsky B; Arav A; De Vries AL The cryoprotective effect of antifreeze glycopeptides from Antartic fishes. Cryobiology 29: 69–79; 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsky B; Arav A; Flecher GL Hypothermic protection—a fundamental property of antifreeze proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 180: 566–571; 1991b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsky B; Arav A; Hong JS; Lee CY Freezing of mammalian livers with glycerol and antifreeze proteins. Biomech Biophys Res Commun 200(2): 732–741; 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sformo T; Walters KR; Jeannette K; McIntyre J; Wowk B; Fahy G; Barnes BM; Duman JG Supercooling, vitrification and limited survival to −100°C in larvae of the Alaskan beetle Cucujus clavipes puniceus (Coleoptera: Cucujidae). J Exp Biol 213: 502–509; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey KB; Storey JM Biochemistry of cryoprotectants In: Denlinger DL; Lee RE (eds) Insects at low temperature. Chapman and Hall, New York, pp 64–93; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Storey KB; Storey JM Physiology, biochemistry, and molecular biology of vertebrate freeze tolerance: the wood frog In: Fuller BJ; Lane N; Benson EE (eds) Life in the frozen state. CRC Press, Baton Rouge, pp 243–274; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tonczak MM, Crowe JH The interaction of antifreeze proteins with model membrane and cells In: Ewart KV; Hew CL (eds) Fish antifreeze proteins. World Scientific, New Jersey, pp 187–212; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Walters KR; Serianni AS; Sformo T; Barnes BM; Duman JG A thermal hysteresis-producing xylomannan antifreeze in a freeze tolerant Alaskan beetle. Proceeding Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 20210–20215; 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L; Duman JG Antifreeze proteins of the beetle Dendroides canadensis enhance one another’s activities. Biochemistry 44: 10305–10312; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L; Duman JG A thaumatin-like protein from larvae of the beetle Dendroides canadensis enhances the activity of antifreeze proteins. Biochemistry 45: 1278–1284; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T; Zhu Q; Yang X; Layne JR Jr.; DeVries AL Antifreeze glycoproteins from the antartic notothenoid fishes fail to protect the rat cardiac explant during hypothermic and freezing preservation. Cryobiology 31: 185–192; 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton DA; Pow B; Kristensen M; Ramlov H; Marshall CJ Ice-active proteins and cryoprotectants from the New Zealand alpine cockroach Celatoblatta quinquemaculta. J Insect Physiol 55: 27–31; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkers WF; Walker NJ; Tablin F; Crowe JH Human platelets loaded with trehalose survive freeze-drying. Cryobiology 42: 79–87; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younis AI; Rooks B; Khan S; Gould KB The effect of antifreeze peptide III and insulin transferrin selenium (ITS) on cryopreservation of chimpanzee spermatozoa. J Androl 19: 207–214; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariassen KE; Hammel HT Nucleating agents in the haemolymph of insects tolerant to freezing. Nature 262: 285–287; 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]