Abstract

Type 3 immunity encompasses innate and adaptive immune responses mediated by cells that produce the signature cytokines IL-17A and IL-17F. This class of effector immunity is particularly adept at controlling infections by pyogenic extracellular bacteria at epithelial barriers. Since mastitis results from infections by bacteria such as streptococci, staphylococci and coliform bacteria that cause neutrophilic inflammation, type 3 immunity can be expected to be mobilized at the mammary gland. In effect, the main defenses of this organ are provided by epithelial cells and neutrophils, which are the main terminal effectors of type 3 immunity. In addition to theoretical grounds, there is observational and experimental evidence that supports a role for type 3 immunity in the mammary gland, such as the production of IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 in milk and mammary tissue during infection, although their respective sources remain to be fully identified. Moreover, mouse mastitis models have shown a positive effect of IL-17A on the course of mastitis. A lot remains to be uncovered before we can safely harness type 3 immunity to reinforce mammary gland defenses through innate immune training or vaccination. However, this is a promising way to find new means of improving mammary gland defenses against infection.

Keywords: type 3 immunity, IL-17, Th17, mastitis, dairy ruminants, mammary gland

A novel approach is required to improve mastitis vaccines

Mastitis is the most frequent and economically important disease of dairy ruminants worldwide [1]. The main bacteria responsible for mammary gland (MG) infections (staphylococci, streptococci, and coliform bacteria) can cause acute clinical mastitis, but more often subclinical long-lasting infection and inflammation [2]. Both types of infections are characterized by the recruitment of leukocytes, mainly neutrophils, into the mammary tissue and secretions. The mechanisms behind this recruitment are incompletely defined, and although several MG defenses have been identified, their coordination and regulation at the cellular and molecular levels are insufficiently understood. Besides, despite many attempts at devising efficacious vaccines, those presently licensed do not fulfill all expectations [2, 3]. We need novel approaches that could offer new development perspectives. We propose that putting the stress on type 3 immunity, its signature cytokines and the cells that produce them or respond to them, could help fulfill this need. In this position paper, we present the reasons that make type 3 immunity a likely major mechanism of MG defense against infection, and we describe the observational and experimental data that support this view. We highlight the emerging knowledge that suggests a role for type 3 immunity both in the inflammatory response of the MG to infection and the prospects that this outlook creates for our understanding of mastitis pathogenesis and its control through vaccination. Vaccination favoring type 3 immunity is an active field of investigation in medical research [4, 5]. We plead for its consideration in the mastitis vaccine field. The recent development of new tools allows researchers to investigate this new research area for dairy ruminants, and to fill some of the knowledge gaps that hamper mastitis control.

Type 3 immunity: a defense mechanism at epithelial barriers

The immune system comprises different classes of effector immunity. The term type 3 immunity emerged recently [6] to qualify an immune response that complements the type 1 and type 2 immunity, heralded by the Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes, respectively. As type 3 immunity is associated with Th17 differentiation and effector functions, it has initially been called type 17 immunity, but type 3 immunity seems more convenient, also encompassing the innate arm of this kind of immunity, mediated by type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3).

Type 3 immunity can be characterized by an immune response that exhibits a distinct profile that includes expression of the genes encoding interleukin-17A (IL-17A), IL-17F and IL-22, and key transcription factors retinoic acid-related orphan receptor Rorγt and Rorα and their gene targets [6, 7]. Type 3 immunity is an ancient immune mechanism whose roots can be found in nematodes or mollusks, which evolved to bridge innate and adaptive immunity to help metazoans live in a microbe’s world [8]. Type 3 immunity is characterized by the recruitment of neutrophils and the stimulation of epithelial antimicrobial defenses at infection sites. Type 3 immunity is often triggered by extracellular bacteria and fungi and seems to be particularly suited to defend epithelial barriers against these pathogens. It can also be implicated in chronic inflammation and autoimmunity. The cells responsible for type 3 immunity are diverse, including ILC3, γδT cells, CD4 helper (Th17) and CD8 (Tc17) αβT cells. Type 3 immune responses deal with infections through the collaboration between antigen-presenting cells, pathogen-specific B and T cells, innate lymphoid cells, neutrophils, and epithelial cells, thus orchestrating the interplay of innate and adaptive immune components [9].

Surprisingly, the MG is not considered as an organ protected by type 3 immunity, although there are considerations about the MG that make it a very likely type 3 battleground for invading bacteria (Table 1). This omission likely stems from the shortfall in the immunological toolkit for the study of type 3 immunity in ruminants and the relative disinterest for infectious mastitis in medical research. However, the toolbox for ruminant immunology was recently enriched, which should enable advances in this research field [10, 11]. Recently, CD4 + cells producing IL-17A have been described in ruminants [10, 12], and bovine Th17 cells have been isolated and expanded in culture [11].

Table 1.

Theoretical reasons why type 3 immunity should contribute to MG defense against pathogens.

| Features of type 3 immunity | Features of mammary gland defenses | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Immunity to extracellular bacteria and fungi | Infection by extracellular bacteria | [61] |

| Defense of epithelial barriers | Mainly epithelial infection (“duct disease”) | [62] |

| Amplifies neutrophilic inflammation | Neutrophils main cell type recruited during mastitis | [63] |

| Neutrophils important effector arm of type 3 immunity | Neutrophils main immune defense of the mammary gland | [63] |

| Induces epithelial self-defense by antimicrobial peptides | Mammary epithelial cells produce AMPs in response to bacteria or cytokines | [62] |

| Targets epithelial cells to trigger inflammation (chemokines) | Mammary epithelial cells respond to IL-17A by secreting chemokines | [17, 24] |

| Signature cytokines: IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22 | IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22 in mastitic milk | [19, 23] |

| Targets epithelial cells through receptors to IL-17 and IL-22 | Mammary epithelial cells express IL-17R and respond to IL-17A & IL-17F | [24] |

| Immunization elicits CD4 + cells producing IL-17 (Th17 lymphocytes) | CD4 + IL-17A + cells correlate with vaccination or antigen-specific sensitization of the mammary gland | [33] |

| The IL-23/IL-17 axis drives granulopoiesis | Mastitis drains neutrophil reserves | [64] |

What we know about type 3 immunity in the mammary gland

The production of IL-17 in the MG has been reported in several studies. Following the characterization of the bovine IL-17A cDNA [13], increases in Il17 gene transcripts measured by RT-qPCR in tissue and milk leukocytes from bovine MG infected by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus uberis provided observational and circumstantial evidence to suggest that IL-17 was implicated in the defense of the MG [13–16]. Overexpression of genes encoding IL-17A and IL-17F was found in the mammary tissue during infection by E. coli [17]. When ELISAs for bovine IL-17 and IL-22 became available, IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 were found in the milk of cows infected by E. coli [18, 19] or goats infected by S. aureus [20].

It has been established that IL-17A contributes to the defense of the MG against infections. Experimental evidence came from mouse models of MG infection. Experimental infection with a mastitis S. aureus strain of goat origin revealed an early influx of γδT cells producing IL-17A into the MG [21]. Other experimental infections of mouse MG with either S. aureus or E. coli showed an early contribution of IL-17 and Th17 cells to the control of infection, rapidly followed by IL-10 and probably regulatory T cells (Treg) intervention [22, 23]. In those studies, co-administration of IL-17A along with the inoculum increased the recruitment of neutrophils and decreased the severity of infection, whereas the administration of an antibody blocking IL-17A decreased the recruitment of neutrophils and resulted in an increased E. coli bacterial load. Those studies demonstrated that IL-17A plays a part in the defense of the mouse MG, with clear beneficial effects in the case of E. coli mastitis, and moderate effects on S. aureus mastitis. Of note, IL-22 concentrations increased markedly in infected MGs and the depletion of γδT lymphocytes did not affect the E. coli mammary load [23].

Another finding was that IL-17A amplifies mammary epithelial cells (MECs) responses to infection. A major effector arm of type 3 immunity involves epithelium proinflammatory and antimicrobial responses. Bovine MECs express (mRNA) the two components of the IL-17 receptor, IL17RA, and IL-17RC, and they respond to IL-17A or IL-17F by producing chemokines and antimicrobial peptides [24]. Interestingly, the response of MECs was enhanced by the simultaneous exposure to TNF-α or to staphylococcal or E. coli microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), suggesting that IL-17 exerts its full potential in a context of inflammation triggered by bacteria [17, 24]. Of note, under these conditions, MECs markedly overexpressed (mRNA) CCL20, a chemokine that attracts cells expressing the receptor CCR6, which include most of type 3 immunity cells [25]. This chemokine was found at the protein level in milk from bovine MGs exposed to E. coli LPS [26].

The preceding data refer to the contribution of type 3 immunity through its innate arm, even though Th17 cells were involved in the mouse mastitis model [23]. These Th17 cells may be the MG counterpart of the innate Th17 cells that have been found to play a part in the immune response to intestinal bacterial pathogens in mice [27]. The contribution to adaptive immunity is less well established. However, there is some evidence that type 3 immunity can be induced in the MG by vaccination. Neutrophilic inflammation in response to the local infusion of antigens can be induced in the MG by immunization. This mammary antigen-specific reaction (mASR) was first described by using ovalbumin as a model antigen. Upon infusion of a few µg of ovalbumin through the teat canal of cows previously sensitized to this antigen by subcutaneous immunization, neutrophils flocked to the lumen of the MG, whereas control unimmunized cows did not react [28]. The same phenomenon was reproduced in the MG of guinea pigs with killed S. aureus as antigen [29]. Experiments with adoptively sensitized guinea pigs have shown that lymphocytes, but not immune serum, made the recipient animals responsive to the sensitizing antigen [30, 31]. In the milk of sensitized and antigen challenged cows, IL-17A and IFN-γ were found as soon as 8 h post-challenge, along with overexpressed transcripts of the genes encoding IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, IL-22, IL-26, and IFN-γ in mammary tissue [32]. The mASR was later shown to correlate with the induction of circulating CD4 T cells producing both IL-17A and IFN-γ [33]. Indeed, a whole-blood assay measuring the production of IL-17A and IFN-γ upon stimulation with the antigen correlated with the magnitude of mASR [32]. Overall, these results strongly suggest that Th17 lymphocytes are associated with antigen-specific neutrophilic inflammation in the MG. This immune response supposes the existence of antigen-presenting cells (APC) in the MG. Cells with a CD11c high, MHCII + and CD205 + phenotype have been described in the bovine MG, within the alveolar epithelium and the connective tissue [34]. These cells, resembling dendritic cells, are distinct from macrophages and in a position to sample the lumen of the MG and present antigenic peptides to tissue-resident effector lymphocytes.

Mirroring the synergy of bacterial MAMPs with IL-17A seen in vitro with MECs, a synergy between innate (MAMPs) and adaptive (Th17) immunity seems to operate in vivo to amplify neutrophilic inflammation in the MG [35]. Such a synergy that increases the recruitment of neutrophils at the onset of infection may reduce the bacterial burden, facilitate the prompt clearance of bacteria, and consequently reduce the initial inflammatory insult to mammary tissue. This scenario was elicited by immunizing cows with a surface protein of Streptococcus agalactiae [36]. This result deserves further investigation at a larger scale and in greater depth with the immunological toolbox currently available for ruminants. An attempt was recently made by vaccinating cows with E. coli extracts before intramammary challenge with the vaccinating strain [19]. The results indicated a level of protection involving the production of IFN-γ and possibly Th17 cells, but the improvement over control cows was moderate. The antibody response did not seem to play an important role in the improved response to MG infection. A further study indicated that a type 3 immunity had been induced in the mammary tissue by local vaccination, as evidenced by the transcriptomic profile of CD4 T cells isolated from the MG parenchyma 24 h post-infection [37].

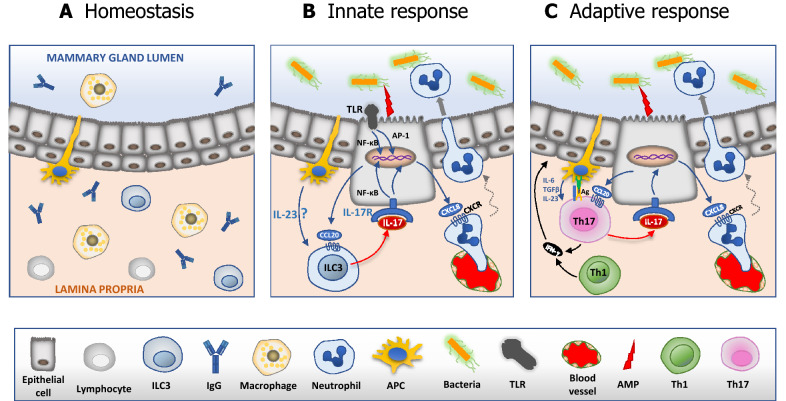

Undoubtedly, there is still a lot to be done before adaptive type 3 immunity can be harnessed effectively to protect against mastitis. However, a putative schematic view of the ways type 3 immunity might operate in the MG can be envisioned (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic view of type 3 immunity governing neutrophilic inflammation in the infected mammary gland. A The healthy MG is an immunologically quiet place at homeostasis as there is little or no bacterial stimulation. B According to the innate immunity scenario, macrophages (MΦ) or epithelial cells responding to invading bacteria attract and stimulate ILC3 that respond by secreting IL-17A. In turn, epithelial cells recruit neutrophils through chemokine secretion. C In the adaptive immunity scenario, the capture of bacteria and presentation of antigen by an antigen-presenting cell (APC) to a tissue resident Th17 cell triggers the release of IL-17A that prompts epithelial cells to secrete chemokines (including CXCL8). These chemokines recruit neutrophils that cross the epithelium to reach invading bacteria.

What we do not know: knowledge gaps

A major issue is the identification of the cells that could contribute to the defense of the MG against infections. Several different cell types are enrolled under the banner of type 3 immunity and produce the signature cytokines. There are antigen-specific cells with αβT-cell receptor (TCR) CD4 + (Th17) and CD8 + T (Tc17) or γδTCR (γδT cells), and lymphoid cells that do not express a TCR, the ILCs. Lymphocytes of the CD4 and CD8 lineages with memory phenotype are found in the milk of healthy and infected MGs, but their functions remain speculative [38, 39]. Among these cells, CD4 T cells expressing RORγt or producing IL-17A have been found in healthy or infected, lactating or involuting mouse MGs, but RORγt + CD8 + T cells have not yet been reported [23, 40]. These lymphocytes require antigen presentation by APCs in association with MHC class I or class II to be fully activated. Th17 cells are well known for their plasticity, and their changing phenotype depends on their environment. The cells, metabolites and cytokines that could influence the phenotype of Th17 cells in the MG remains an unexplored but important area of research. Besides Th17 cells, γδT cells express receptors of the innate immune system such as Toll-like receptors (TLR)1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4 and dectin 1, which allow them to respond to MAMPs [41, 42]. They can also secrete IL-17A and IL-22 without the engagement of the TCR in the presence of IL-1β and IL-23. In the bovine species, WC1 + γδT cells, CD4 + (Th17) and CD8 + T cells have been shown to produce IL-17A [10, 12, 43, 44]. In organs and at periphery tissues, most bovine γδT cells are of the WC1-phenotype and would differ functionally from the WC1 + phenotype [41]. During infection, γδT cells are recruited in milk and a few studies indicated selective recruitment of particular subsets [45, 46]. Other type 3 immune cells do not possess TCR and belong to the innate arm of immunity. The most recently described are the ILCs that come in three types, ILC1, ILC2 and ILC3 [47]. They are the innate counterparts of the Th1, Th2, and Th17 adaptive T cells. ILC3 cells mostly populate parenchymal tissues and mucosal epithelia, where they hold important functions of early resistance to pathogens, regulation of inflammation and tissue homeostasis [48]. Bovine ILCs have not been described yet. These cells are difficult to study because they reside mainly in peripheral tissues, hardly recirculate and are difficult to extract from their niche environment. We do not know if they can respond to MAMPs, as human ILCs do, or cannot, like mice ILCs. ILC3 respond to IL-23 and IL-1α or IL-1β to produce their effector cytokines (IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22) [48]. Whether IL-23 is overexpressed in the MG during infection remains to be established. It is likely that ILCs are present in mammary tissue and contribute to the defense of the MG, but so far that has not been documented.

We do not know precisely which cells produce IL-17A/F and IL-22 in the MG during infection. Much of the IL-17 released during an inflammatory response is produced by innate immune cells [49]. In both mice and humans, γδT cells and ILCs are important sources of the Th17 cytokines IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-22 in the epithelial tissues. We can speculate that different cell types secrete IL-17A and IL-22 during an E. coli infection or LPS inflammation episode because IL-17A/F and IL-22 concentration increases in milk did not coincide [19]. We are also ignorant of the respective roles of the type 3 immunity signature cytokines in the defense of the MG against infection, wound healing, physiology at involution and homeostasis. We know that IL-22 is endowed with important functions of control of pathogens and tissue repair [50]. However, we do not know the effects of IL-22 on mammary tissue. Several studies have shown that in the bovine species type 3 immunity and the associated cytokines are likely to play a positive or negative part in viral, mycobacterial (tuberculosis and paratuberculosis) or parasitic diseases [43, 51–55]. The cytokine IL-26 is also associated with type 3 immunity [56]. Contrary to the laboratory mouse, but like humans, ruminants have a functional Il26 gene. Human IL-26 possesses antibacterial activity [57]. Bovine Il26 can be expressed in mammary tissue and by bovine Th17 cells [11, 32], but its role in the mastitis context remains to be established.

Another knowledge gap refers to the homing and addressing of innate and adaptive lymphocytes to mammary tissue. Few studies addressed this important issue in the MG of ruminants. What we know is that the adhesion molecule MAdCAM-1 was not found to be expressed in the bovine MG and supramammary lymph nodes whatever the physiological stage and lymphocytes expressing the counter-receptor α4β7 were not detected in mammary tissues [58], suggesting that this vascular addressin is not involved in the recruitment of lymphocytes in healthy glands.

Prospects: beyond the mastitis vaccine deadlock

We have seen that there are several theoretical, observational and experimental arguments supporting the notion that type 3 immunity is an important arm of the immune defense of the MG. It is patent that a lot remains to be uncovered about the ins and outs of this immune type in ruminant in general and in the MG in particular. In the mastitis context, a major driver for a better knowledge of type 3 immunity in the MG is the development of efficacious vaccines. Conventional views of MG defenses and vaccine mode of action, which are essentially based on antibody response, may have come to a deadlock. An alternative approach based on new developments of immunology is possible by capitalizing on a better knowledge of cell-mediated type 3 immunity. This raises the possibility of new experiments and progress towards more efficacious vaccines, by combining immunology knowledge and vaccinology approaches [59].

For practical purposes, what do we need to harness type 3 immunity to control mastitis? The issue of the orientation of the immune response in ruminants is crucial. A major research topic should be the search for antigens and adjuvants that engage the appropriate APC and ILC subsets and therefore orient the adaptive immune response towards type 3 immunity. Preliminary data indicate that it is possible to induce protective Th17 cells in the MG. To elicit a protective type 3 immune response in the MG, we will need to select antigens with T-cell epitopes presented by the MHC class II targeting the right APCs by the proper delivery system, with the appropriate adjuvant. Undoubtedly, much remains to be explored before we are able to meet these different requirements. We know very little about CD8 T cells producing IL-17 (Tc17). Yet, those cells might be instrumental in flushing out bacteria sheltered in epithelial cells or macrophages. Other cells of the innate arm of type 3 immunity are also likely to play an important part in the defense of the MG. It can also be envisaged harnessing the innate component of type 3 immunity with immunomodulators. A foreseeable complication to these approaches will come from the proinflammatory facet of type 3 immunity and its impact on the MG integrity. In effect, an overshooting inflammatory reaction could jeopardize the MG function, i.e., secretion of milk. The immune response must be adapted to the pathogen: what is good for E. coli mastitis may not be necessarily good for S. uberis or S. aureus mastitis. Type 3 immunity could be beneficial by improving the efficiency of the acute phase of an infection that self-cures as E. coli mastitis usually does. Its role may be more complex in chronic infections such as S. aureus mastitis. It may even be detrimental in the case of S. uberis infection, as the efficiency of phagocytic killing by neutrophils is dubious [60]. However, IL-17 correlated with the resolution of MG infections by S. uberis [14], an observation that could be in relation with type 3 immunity protective mechanisms other than neutrophilic inflammation, such as the contribution of Tc17 cells or the self-defense response of epithelial cells. Type 1 immunity or Tc17 cells may be a more important component of the immune response with bacteria that are apt at surviving within epithelial cells such as S. aureus than with E. coli. Taking into account the pathogenesis of the infection at issue will be necessary. Moreover, inflammation-driven dysfunction may be more or less critical according to the organ at stake. In the lungs, for example, loss of function is incompatible with life, whereas, in the mammary gland, a temporary loss of function is critical only to the offspring if it lasts several days, and thus a level of inflammation is tolerable in the MG that would not be in the lungs. However, this caveat should be addressed by a fine-tuning of the elicited immunity. The new tools and concepts of immunology will help to respond to these challenges.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- IL

interleukin

- ILC

innate lymphoid cell

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- mASR

mammary antigen-specific reaction

- MAMP

microbe-associated molecular pattern

- MEC

mammary epithelial cell

- ROR

RAR-related orphan nuclear receptor

- TLR

toll-like receptor

Authors’ contributions

All authors discussed the topic, PR wrote the first draft, PC and PR drew the figure. All authors edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

PR, PC, RPM, FG, and PG were funded by INRAE, GF by INRAE and ENVT.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Martin P, Barkema HW, Brito LF, Narayana SG, Miglior F. Symposium review: novel strategies to genetically improve mastitis resistance in dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101(3):2724–2736. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klaas IC, Zadoks RN. An update on environmental mastitis: Challenging perceptions. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65(Suppl 1):166–185. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rainard P, Foucras G, Fitzgerald JR, Watts JL, Koop G, Middleton JR. Knowledge gaps and research priorities in Staphylococcus aureus mastitis control. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65(Suppl. 1):149–165. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Brien EC, McLoughlin RM. Considering the 'alternatives' for next-generation anti-Staphylococcus aureus vaccine development. Trends Mol Med. 2019;25(3):171–184. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malley R, Anderson PW. Serotype-independent pneumococcal experimental vaccines that induce cellular as well as humoral immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(10):3623–3627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121383109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Annunziato F, Romagnani C, Romagnani S. The 3 major types of innate and adaptive cell-mediated effector immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(3):626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaffen SL. An overview of IL-17 function and signaling. Cytokine. 2008;43(3):402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eberl G. Development and evolution of RORgammat+ cells in a microbe's world. Immunol Rev. 2012;245(1):177–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silberger DJ, Zindl CL, Weaver CT. Citrobacter rodentium: a model enteropathogen for understanding the interplay of innate and adaptive components of type 3 immunity. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(5):1108–1117. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wattegedera SR, Corripio-Miyar Y, Pang Y, Frew D, McNeilly TN, Palarea-Albaladejo J, McInnes CJ, Hope JC, Glass EJ, Entrican G. Enhancing the toolbox to study IL-17A in cattle and sheep. Vet Res. 2017;48(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13567-017-0426-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunha P, Vern YL, Gitton C, Germon P, Foucras G, Rainard P. Expansion, isolation and first characterization of bovine Th17 lymphocytes. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16115. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52562-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elnaggar MM, Abdellrazeq GS, Dassanayake RP, Fry LM, Hulubei V, Davis WC. Characterization of alphabeta and gammadelta T cell subsets expressing IL-17A in ruminants and swine. Dev Comp Immunol. 2018;85:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riollet C, Mutuel D, Duonor-Cerutti M, Rainard P. Determination and characterization of bovine interleukin-17 cDNA. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26(3):141–149. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tassi R, McNeilly TN, Fitzpatrick JL, Fontaine MC, Reddick D, Ramage C, Lutton M, Schukken YH, Zadoks RN. Strain-specific pathogenicity of putative host-adapted and nonadapted strains of Streptococcus uberis in dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 2013;96(8):5129–5145. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-6741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tao W, Mallard B. Differentially expressed genes associated with Staphylococcus aureus mastitis of Canadian Holstein cows. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2007;120(3–4):201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruno DR, Rossitto PV, Bruno RG, Blanchard MT, Sitt T, Yeargan BV, Smith WL, Cullor JS, Stott JL. Differential levels of mRNA transcripts encoding immunologic mediators in mammary gland secretions from dairy cows with subclinical environmental Streptococci infections. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2010;138(1–2):15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roussel P, Cunha P, Porcherie A, Petzl W, Gilbert FB, Riollet C, Zerbe H, Rainard P, Germon P. Investigating the contribution of IL-17A and IL-17F to the host response during Escherichia coli mastitis. Vet Res. 2015;46:56. doi: 10.1186/s13567-015-0201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blum SE, Heller ED, Jacoby S, Krifucks O, Leitner G. Comparison of the immune responses associated with experimental bovine mastitis caused by different strains of Escherichia coli. J Dairy Res. 2017;84(2):190–197. doi: 10.1017/S0022029917000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herry V, Gitton C, Tabouret G, Reperant M, Forge L, Tasca C, Gilbert FB, Guitton E, Barc C, Staub C, Smith DGE, Germon P, Foucras G, Rainard P. Local immunization impacts the response of dairy cows to Escherichia coli mastitis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3441. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03724-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rainard P, Gitton C, Chaumeil T, Fassier T, Huau C, Riou M, Tosser-Klopp G, Krupova Z, Chaize A, Gilbert FB, Rupp R, Martin P. Host factors determine the evolution of infection with Staphylococcus aureus to gangrenous mastitis in goats. Vet Res. 2018;49:72. doi: 10.1186/s13567-018-0564-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jing XQ, Cao DY, Liu H, Wang XY, Zhao XD, Chen DK. Pivotal Role of IL-17-producing gamma delta T cells in Mouse chronic mastitis experimentally induced with Staphylococcus aureus. Asian J Anim Vet Adv. 2012;7(12):1266–1278. doi: 10.3923/ajava.2012.1266.1278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Y, Zhou M, Gao Y, Liu H, Yang W, Yue J, Chen D. Shifted T helper cell polarization in a murine Staphylococcus aureus mastitis model. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0134797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porcherie A, Gilbert FB, Germon P, Cunha P, Trotereau A, Rossignol C, Winter N, Berthon P, Rainard P. IL-17A Is an important effector of the immune response of the mammary gland to Escherichia coli infection. J Immunol. 2016;196(2):803–812. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bougarn S, Cunha P, Gilbert FB, Harmache A, Foucras G, Rainard P. Staphylococcal-associated molecular patterns enhance expression of immune defense genes induced by IL-17 in mammary epithelial cells. Cytokine. 2011;56(3):749–759. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito T, Carso WFt, Cavassani KA, Connett JM, Kunkel SL. CCR6 as a mediator of immunity in the lung and gut. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317(5):613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Védrine M, Berthault C, Leroux C, Reperant-Ferter M, Gitton C, Barbey S, Rainard P, Gilbert FB, Germon P. Sensing of Escherichia coli and LPS by mammary epithelial cells is modulated by O-antigen chain and CD14. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geddes K, Rubino SJ, Magalhaes JG, Streutker C, Le Bourhis L, Cho JH, Robertson SJ, Kim CJ, Kaul R, Philpott DJ, Girardin SE. Identification of an innate T helper type 17 response to intestinal bacterial pathogens. Nat Med. 2011;17(7):837–844. doi: 10.1038/nm.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Cueninck BJ. Immune-mediated inflammation in the lumen of the bovine mammary gland. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1979;59(4):394–402. doi: 10.1159/000232286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Targowski SP, Nonnecke BJ. Cell-mediated immune response of the mammary gland in guinea pigs. I. Effect of antigen injection into the vaccinated and unvaccinated glands. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1982;2(1):29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1982.tb00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nonnecke BJ, Targowksi SP. Cell-mediated immune response in the mammary gland of guinea pigs adoptively sensitized with lymphocytes. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1984;6(1):9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1984.tb00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Cueninck BJ. Expression of cell-mediated hypersensitivity in the lumen of the mammary gland in guinea pigs. Am J Vet Res. 1982;43(9):1696–1700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rainard P, Cunha P, Bougarn S, Fromageau A, Rossignol C, Gilbert BF, Berthon P. T helper 17-associated cytokines are produced during antigen-specific inflammation in the mammary gland. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rainard P, Cunha P, Ledresseur M, Staub C, Touze JL, Kempf F, Gilbert FB, Foucras G. Antigen-specific mammary inflammation depends on the production of IL-17A and IFN-gamma by bovine CD4+ T lymphocytes. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maxymiv NG, Bharathan M, Mullarky IK. Bovine mammary dendritic cells: a heterogeneous population, distinct from macrophages and similar in phenotype to afferent lymph veiled cells. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;35(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rainard P, Cunha P, Gilbert FB. Innate and adaptive immunity synergize to trigger inflammation in the mammary gland. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0154172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rainard P, Lautrou Y, Sarradin P, Coulibaly A, Poutrel B. The kinetics of inflammation and phagocytosis during bovine mastitis induced by Streptococcus agalactiae bearing the protein X. Vet Res Commun. 1991;15(3):163–176. doi: 10.1007/BF00343221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cebron N, Maman S, Walachowski S, Gausseres B, Cunha P, Rainard P, Foucras G (2020) Mammary Th17-related immunity, but not high systemic Th1 response is associated with protection against E. coli mastitis. npj Vaccines (accepted for publication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Taylor BC, Keefe RG, Dellinger JD, Nakamura Y, Cullor JS, Stott JL. T cell populations and cytokine expression in milk derived from normal and bacteria-infected bovine mammary glands. Cell Immunol. 1997;182(1):68–76. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riollet C, Rainard P, Poutrel B. Cells and cytokines in inflammatory secretions of bovine mammary gland. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;480:247–258. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46832-8_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Betts CB, Pennock ND, Caruso BP, Ruffell B, Borges VF, Schedin P. Mucosal immunity in the female murine mammary gland. J Immunol. 2018;201(2):734–746. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baldwin CL, Telfer JC. The bovine model for elucidating the role of gamma delta T cells in controlling infectious diseases of importance to cattle and humans. Mol Immunol. 2015;66(1):35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonneville M, O'Brien RL, Born WK. Gammadelta T cell effector functions: a blend of innate programming and acquired plasticity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(7):467–478. doi: 10.1038/nri2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peckham RK, Brill R, Foster DS, Bowen AL, Leigh JA, Coffey TJ, Flynn RJ. Two distinct populations of bovine IL-17(+) T-cells can be induced and WC1(+)IL-17(+)gammadelta T-cells are effective killers of protozoan parasites. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5431. doi: 10.1038/srep05431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinbach S, Vordermeier HM, Jones GJ. CD4+ and gammadelta T Cells are the main producers of IL-22 and IL-17A in lymphocytes from mycobacterium bovis-infected cattle. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29990. doi: 10.1038/srep29990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soltys J, Quinn MT. Selective recruitment of T-cell subsets to the udder during staphylococcal and streptococcal mastitis: analysis of lymphocyte subsets and adhesion molecule expression. Infect Immun. 1999;67(12):6293–6302. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.12.6293-6302.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riollet C, Rainard P, Poutrel B. Cell subpopulations and cytokine expression in cow milk in response to chronic Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Dairy Sci. 2001;84(5):1077–1084. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eberl G, Colonna M, Di Santo JP, McKenzie AN. Innate lymphoid cells. Innate lymphoid cells: a new paradigm in immunology. Science. 2015;348(6237):aaa6566. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klose CSN, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells as regulators of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(7):765–774. doi: 10.1038/ni.3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cua DJ, Tato CM. Innate IL-17-producing cells: the sentinels of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(7):479–489. doi: 10.1038/nri2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alabbas SY, Begun J, Florin TH, Oancea I. The role of IL-22 in the resolution of sterile and nonsterile inflammation. Clin Transl Immunol. 2018;7(4):e1017. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGill JL, Rusk RA, Guerra-Maupome M, Briggs RE, Sacco RE. Bovine gamma delta T cells contribute to exacerbated IL-17 production in response to co-infection with bovine RSV and mannheimia haemolytica. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waters WR, Maggioli MF, Palmer MV, Thacker TC, McGill JL, Vordermeier HM, Berney-Meyer L, Jacobs WR, Jr, Larsen MH. Interleukin-17A as a biomarker for bovine tuberculosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1128/CVI.00637-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeKuiper JL, Coussens PM. Mycobacterium avium sp paratuberculosis (MAP) induces IL-17a production in bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and enhances IL-23R expression in-vivo and in-vitro. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2019;10:9952. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2019.109952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhuju S, Aranday-Cortes E, Villarreal-Ramos B, Xing Z, Singh M, Vordermeier HM. Global gene transcriptome analysis in vaccinated cattle revealed a dominant role of IL-22 for protection against bovine tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(12):e1003077. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flynn RJ, Marshall ES. Parasite limiting macrophages promote IL-17 secretion in naive bovine CD4(+) T-cells during Neospora caninum infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donnelly RP, Sheikh F, Dickensheets H, Savan R, Young HA, Walter MR. Interleukin-26: An IL-10-related cytokine produced by Th17 cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21(5):393–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meller S, Di Domizio J, Voo KS, Friedrich HC, Chamilos G, Ganguly D, Conrad C, Gregorio J, Le Roy D, Roger T, Ladbury JE, Homey B, Watowich S, Modlin RL, Kontoyiannis DP, Liu YJ, Arold ST, Gilliet M. T17 cells promote microbial killing and innate immune sensing of DNA via interleukin 26. Nat Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ni.3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hodgkinson AJ, Carpenter EA, Smith CS, Molan PC, Prosser CG. Adhesion molecule expression in the bovine mammary gland. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2007;115(3–4):205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pulendran B, Ahmed R. Immunological mechanisms of vaccination. Nat Immunol. 2011;131(6):509–517. doi: 10.1038/ni.2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Field TR, Ward PN, Pedersen LH, Leigh JA. The hyaluronic acid capsule of Streptococcus uberis is not required for the development of infection and clinical mastitis. Infect Immun. 2003;71(1):132–139. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.132-139.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barkema HW, Green MJ, Bradley AJ, Zadoks RN. Invited review: The role of contagious disease in udder health. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92(10):4717–4729. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rainard P, Riollet C. Innate immunity of the bovine mammary gland. Vet Res. 2006;37(3):369–400. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paape M, Mehrzad J, Zhao X, Detilleux J, Burvenich C. Defense of the bovine mammary gland by polymorphonuclear neutrophil leukocytes. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2002;7(2):109–121. doi: 10.1023/A:1020343717817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burvenich C, Van Merris V, Mehrzad J, Diez-Fraile A, Duchateau L. Severity of E. coli mastitis is mainly determined by cow factors. Vet Res. 2003;34(5):521–564. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.