Abstract

Nanogels, or nanostructured hydrogels, are one of the most interesting materials in biomedical engineering. Nanogels are widely used in medical applications, such as in cancer therapy, targeted delivery of proteins, genes and DNAs, and scaffolds in tissue regeneration. One salient feature of nanogels is their tunable responsiveness to external stimuli. In this review, thermosensitive nanogels are discussed, with a focus on moieties in their chemical structure which are responsible for thermosensitivity. These thermosensitive moieties can be classified into four groups, namely, polymers bearing amide groups, ether groups, vinyl ether groups and hydrophilic polymers bearing hydrophobic groups. These novel thermoresponsive nanogels provide effective drug delivery systems and tissue regeneration constructs for treating patients in many clinical applications, such as targeted, sustained and controlled release.

Keywords: nanogels, thermoresponsive, drug delivery

1. Introduction

1.1. Hydrogels

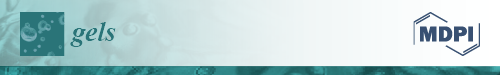

Hydrogels are three-dimensional cross-linked structures based on natural or synthetic polymers. Hydrogels can be produced in different physical forms, such as slabs, macroparticles, nanoparticles and films [1,2]. Promising properties, such as high water content, biocompatibility and degradability, make hydrogels very useful for biomedical applications [3,4,5]. A salient example of biocompatible hydrogels is the injectable and temperature-sensitive poly(amino carbonate urethane) (PACU) hydrogel, which has been used as a delivery vehicle for sustained release of human growth hormone factor [6]. Similarly, the alternating hydrophilic/hydrophobic properties of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-co-methacrylate [P(NIPAM-co-MA] hydrogel are used for temperature sensing in biomedical applications [7]. Due to nanogels’ structural properties, hydrogels are abundantly used in drug delivery systems and fabrication of tissue scaffolds [6,8,9]. The structure of hydrogels can be modified by conjugation with appropriate ligands to improve properties such as drug entrapment, release profile and targeting [10,11,12]. In a recent study, Liao et al. presented a novel method for the preparation of multi-responsive DNA-acrylamide (DNA-AAM)-based hydrogel microcapsules [13]. Hydrogels are also used extensively in tissue engineering as more suitable materials to fabricate biodegradable scaffolds for tissue regeneration [14,15]. One important parameter which can affect the biodegradability of hydrogels is the lower critical solution temperature (LCST). As a definition, when two immiscible liquid phases appear as a result of temperature increase at the different compositions of polymer and solvent, the minimum of the coexistence curve of the phase diagram is the LCST [16]. Figure 1 represents the schematic degradation mechanism of a thermoresponsive hydrogel for drug delivery applications, which is controlled by the LCST. Below the LCST, the thermosensitive hydrogel is in the solution state but when temperature increases and it is higher than LCST, gelation occurs, and for in-vivo or in-vitro conditions under specific circumstances such as exposing to enzymes, hydrogel can degrade. Hydrogels also have shortcomings, which leads to uncertainty in their applications in medicine, which can be addressed by transforming their macro- and micro-structure to the nanoscale.

Figure 1.

Schematic degradation of thermosensitive hydrogel below and above LCST.

1.2. Nanostructured Materials

Nanostructured devices are a novel class of materials with many biomedical applications [17,18,19]. The preeminent property of nanostructures is their high surface-to-volume ratio, which makes these structures injectable and improves their penetration between physiological barriers in the human body. These structures enhance disease treatment with minimum side effects and toxicity [20]. Nanostructures can be prepared in different forms, like nano-films [21], nanofibers [22,23], nanoparticles [24,25], and nanogels [26], which have the potential to be used in both drug delivery systems and tissue engineering. Recent studies indicate that nanoscale structures impact biological response; thus, they can be used to modify the surface of medical implants to decrease undesired biological responses [27,28]. Bamberger et al. synthesized a polysaccharide-based nanostructure within the 100–200 nm size range, which was modified with dextran (Dex) and polyethylene glycol (PEG) and assessed for its ability to bind to immune cells. They reported that the surface modification of nanoparticles with dextran (DEXylation) enhanced targeting with a desirable immune response [29].

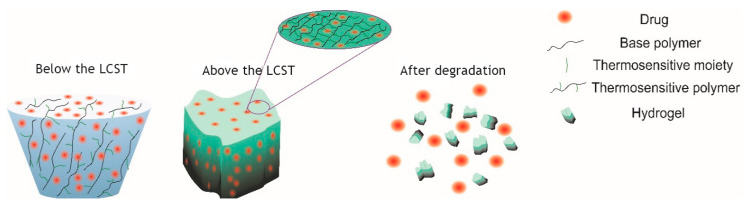

In drug delivery systems, nanostructures can be injected subcutaneously or intravenously to deliver the loaded drugs to the site of injury or disease with minimum cell toxicity and immune response [30]. The surface of the drug delivery system can be modified with ligands that can be detected by receptors on the surface of malignant tumours in cancer therapy [31,32,33,34]. Stimuli-responsive nanostructures have the potential to be used for targeted delivery and controlled drug release. The pH [35], temperature [36], magnetic field [37] and redox reaction [38,39] are the most commonly used environmental factors in stimuli-responsive systems. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers have the potential to induce enhanced permeability [40,41]. In addition, targeted delivery enables selective delivery of the drug to the diseased tissue while leaving the healthy tissue unharmed [42]. Despite the numerous advantages of nanocarriers for drug delivery, there are some challenges to be tackled, including difficulty of synthesis, low stability, and the circulation time of nanocarriers in blood circulation. In some cases, toxicity to normal cells and non-biodegradability are the main deficiencies of these structures [43]. Figure 2 shows two general types of modified nanocarriers, which can be used for the targeted delivery of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs.

Figure 2.

(a) Infrared-responsive nanocarriers for in-situ forming hydrogels as a drug delivery system and tissue scaffold and (b) magnetic fields and temperature-responsive nanocarriers for increasing drug release.

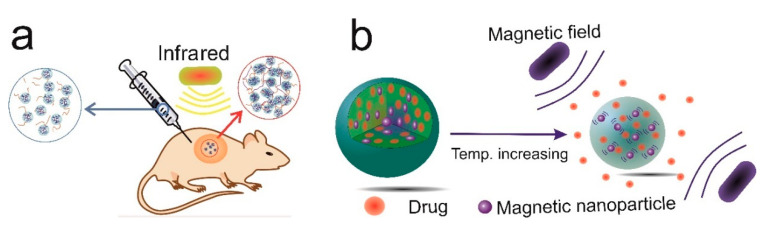

2. Nanogels

Nanogels are three-dimensional (3D) structures that are able to swell several times their non-swollen form [44,45]. Nanogels are nanostructured hydrogels with the advantages of both nanostructured materials and hydrogels. The two main characteristics of nanogels are their small size (up to 1000 nm) and high swelling ratio or water content [46]. Due to these properties, nanogels have become an excellent platform in many medical applications, including photo-imaging [47], tissue regeneration [48], cancer therapy [49] and gene delivery [50]. This is based on their remarkable characteristics, such as their high capacity for drug entrapment and release [51], tailorable size [52], tuneable toxicity [53], high stability, controlled and sustained drug release [54], precise targeted delivery [55], and high biodegradability [56]. Nanogels can be used for drug delivery through oral [57], pulmonary [58], nasal [59], intra-ocular [60] and topical [60] pathways. There are many methods that can be used to prepare stimuli-responsive nanogels for targeted delivery. Thermosensitive [61], pH-sensitive [62,63], glucose-sensitive [64], redox-sensitive [65], and magnetic-field-sensitive [66] nanogels are applicable to the treatment of many diseases (Figure 3). Furthermore, nanogels can be tailored as dual or multi-responsive structures [42,67]. Deng et al. explored the synthesis and properties of poly (N,N-dimethyl aminoethyl methacrylate -g- Ethylene glycol) P(DMAEMA-g-EG) nanogel carriers with 190–600 nm diameters, which showed pH, ionic strength and temperature sensitivity with LCSTs of about 35 °C [68]. The objective of this review is to describe the properties of thermoresponsive nanogels, with a focus on polymeric moieties that influence the thermoresponsive behavior of nanogels in biomedical applications. Given the wide range of applications, thermoresponsive nanogels are promising for many medical uses, such as for sensors, imaging, diagnosis, treatment and gene delivery. Different types of thermosensitive generator side groups, followed by various applications of the thermoresponsive nanogels, will be presented.

Figure 3.

Scheme of different stimuli-responsive nanogels in response to temperature, enzyme, the magnetic field, and pH in drug delivery applications.

Thermosensitive Nanogels

Thermosensitive nanogels are soft nanostructured materials that respond to temperature changes in the surrounding medium. Two approaches are used to prepare thermosensitive nanogels. In the first approach, thermosensitive polymer units are incorporated in the backbone or the main structure of a nanogel-forming polymer to induce thermosensitivity. In the second approach, hydrophobic moieties are attached as side groups to a hydrophilic polymer backbone to impart temperature sensitivity [69,70,71]. The LCST of the polymer decreases as the fraction of polymer units with a hydrophobic side group is increased. Therefore, the gelation temperature can be tuned by changing the degree of substitution of backbone units with hydrophobic moieties.

The mechanism responsible for thermosensitivity is the extent of the molecular interactions which could be categorized as hydrophobic or hydrophilic, depending on the free energy change of the surrounding solvent. A positive change or a negative change in the free energy of a mixture indicates its hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity, respectively [72]. Association of water molecules, as the governing interaction in the system, is the main cause of free energy change. Water molecules at temperatures lower than the LCST align well around hydrophilic parts. However, at temperatures above the LCST, owing to the hydrophobicity of the surrounding groups, water molecules start detaching, with a consequent phase separation between the water and polymers. Moreover, as the temperature increases, the alignment of water molecules collapses due to hydrophobic moieties, and the entropy of the system increases, which leads to gel formation. In other words, when the temperature is lower than the LCST, hydrophilic–hydrophilic interactions are stronger than hydrophobic–hydrophobic interactions, and this increases polymer solubility. As the temperature increases, hydrophobic–hydrophobic interactions become more important than hydrophilic–hydrophilic interactions, which eventually leads to aggregation of hydrophobic moieties and nanogel formation.

3. Thermosensitive Polymers

3.1. Polymers Bearing Amide Groups

3.1.1. PNIPAM

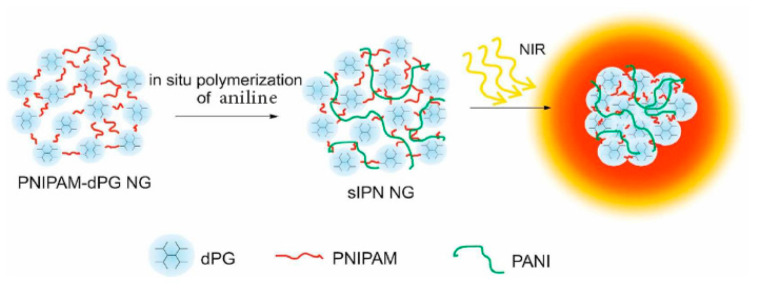

Poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide) (PNIPAM) is a thermosensitive polymer containing hydrophilic (C = O, NH) and hydrophobic groups (i.e., CH3). PNIPAM is synthesized by free radical polymerization. This polymer is abundantly investigated in tissue engineering and drug delivery applications [73,74,75]. Although the LCST of PNIPAM is about 32 °C, which makes this polymer an appropriate temperature-sensitive biomaterial, the non-biodegradability of PNIPAM impedes its widespread use in clinical applications. PNIPAM-based drug carriers can be modified with different functional groups for targeted drug delivery [76], controlled release [77], imaging and tracking [47], as well as other functionalities [66]. Zhou et al. investigated doxorubicin (DOX) release from a temperature-sensitive and photoluminescent hydrogel using PNIPAM and cadmium telluride quantum dots (CdTe QDs) (photoluminescent inducer) with polyacrylamide (PAA) as a crosslinker. Results demonstrated that the rate of drug release could be adjusted by external temperature [78]. Molina et al. formulated a near-infrared (NIR) absorbing nanogel based on N-isopropylacrylamide– dendritic polyglycerol–polyaniline (NIPAM-dPG-PANI) for photothermal cancer therapy (Figure 4). The size of nanogels was about 150–240 nm, and in-vitro MTT [3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide] assays on A2780 cells and in-vivo (mice) investigations were performed. In this research, the results indicated that mice could tolerate a 500 mg/kg dose of nanogels in 5 days without substantial toxicity [79]. Śliwa et al. synthesized a temperature-responsive nanogel with a hydrodynamic diameter of 150–650 nm for the controlled release of orange II. This nanogel was prepared by polymerization of 1-vinylimidazole (Vim) and PNIPAM monomers, with bisacrylamide (BAM) as the crosslinker [51].

Figure 4.

In-situ mechanism for near-infrared absorbing nanogels based on PNIPAM-dPG-PANI for photothermal cancer therapy. Adapted from Ref. [79] reproduced by permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry.

3.1.2. PNIPMAM

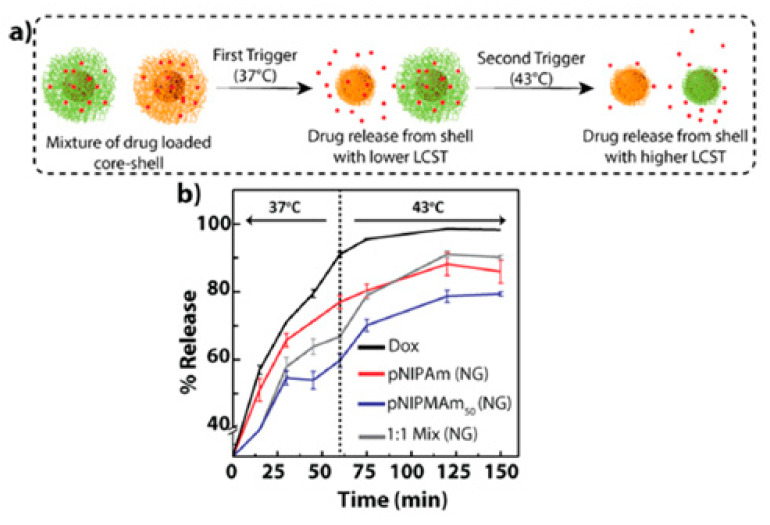

Poly (N-isopropyl methacrylamide) (PNIPMAM) is another amide-bearing thermosensitive polymer that contains methyl groups attached to the α-carbon, with a higher swelling ratio in the aqueous medium compared to PNIPAM [80]. Despite having similar characteristics to PNIPAM, there are remarkable differences between the two polymers for drug delivery applications. One important difference is the higher LCST of PNIPMAM (38 °C) compared to PNIPAM (32 °C), due to the higher hydrophilicity of PNIPAM compared to PNIPMAM [81]. Cors et al. synthesized a core–shell thermosensitive nanogel based on PNIPMAM as the core and PNIPAM as the shell in order to understand the swelling and shrinking behaviour of the polymer [82]. The results of this study indicated a linear increase in swelling with temperature in the range of 25 to 35 °C. Peters et al. prepared a thermosensitive PNIPMAM-based core–shell nanogel for cancer therapy for controlled and triggered release of DOX. The cytotoxicity of the synthesized nanogels was investigated with L929 fibroblasts, and low toxicity on cells was demonstrated [83]. In Figure 5, Deshpande et al. prepared core–shell nanogels using PNIPMAM as the shell and gold nanoparticles as the core for sustained, triggered release of DOX [84].

Figure 5.

NIPAM and NIPMAM-based thermosensitive core–shell nanogels for triggered and sustained release of DOX. (a) Schematic diagram showing the trigger-based release and (b) sustained release of DOX from the nanogels. Adopted from Ref. [84] reproduced by permission of American Chemical Society. Further permissions related to the material excerpted should be directed to the ACS.

3.1.3. PDEAAM

Poly (N,N-diethylacrylamide) (PDEAAM) is a thermosensitive polymer studied by Idziak et al. to determine the LCST of PDEAAM at different concentrations of sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), using ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). They showed that PDEAAM had a sharp phase transition with an LCST of about 33 °C [85]. Different research groups have studied PDEAAM’s properties, such as enhancement of thermosensitivity by copolymerization with 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) [86] and thermal responsivity of PDEAAM hydrogels prepared by γ-ray irradiation [87]. In the past decade, PDEAAM has been used for the preparation of responsive hydrogels [88,89,90], micelles [91,92] and nanogels [93,94] for biomedical applications. Lu et al. prepared non-ionic and thermosensitive nanogels with 100-nm diameters, based on N,N-diethyl acrylamide (DEA) and N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA), which can be used for DNA separation by microchip electrophoresis [95]. Rieger et al. synthesized thermoresponsive PEGylated micelles and nanogels to form core–shell nanostructures, with diameters of 800 and 550 nm at 15 and 70 °C, respectively [96], which could be used as drug carriers.

3.1.4. PVCL

Poly (N-vinyl caprolactam) (PVCL) is a water-soluble amphiphilic polymer, with non-ionic, thermoresponsive characteristics. Polymer molecular weight can affect LCST. Because of its biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity, PVCL is considered an ideal thermoresponsive polymer for biomedical applications [97,98,99], particularly when compared to PNIPAM [100,101,102]. PVCL conjugation with hydrophilic units such as PEG or derivatives of PEG enables the synthesis of temperature-responsive block copolymers. For temperatures above the CPT of PVCL, these block copolymers act as amphiphilic structures to form well-defined nanoscale aggregates by self-assembly pathways. Such stimuli-responsive structures, due to their ability to assemble or disassemble without using any additive, have immense potential for use in advanced drug delivery systems [103].

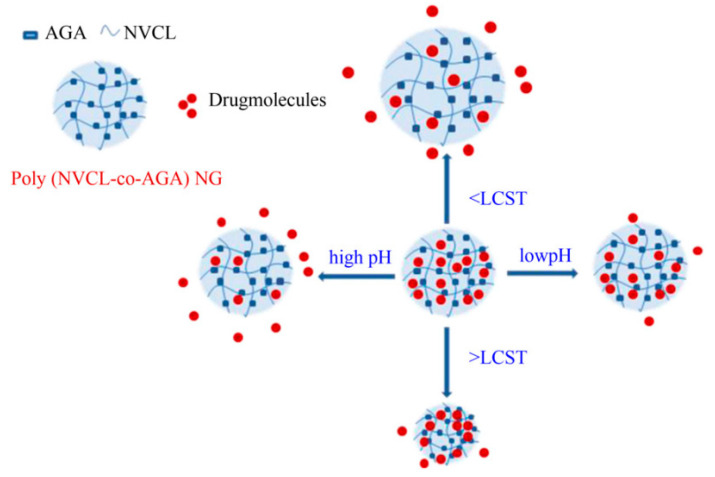

PVCL has also been utilized for the preparation of stimuli-responsive nanoparticles and nanofibers [37]. For instance, González et al. prepared thermoresponsive nanofibers via the electrospinning technique and investigated their use in drug delivery systems. PVCL and hydroxymethyl acrylamide were copolymerized and used to generate Rhodamine B (RhB)-loaded nanofibers with diameters in the range of 550–1200 nm. The results demonstrated that the copolymer could be used as a biosensor or as a matrix for controlled drug delivery [22]. In another study, Kehren et al. prepared polycaprolactone (PCL) microfibers modified with PVCL-based nanogel and investigated water uptake and degradability. The results demonstrated that the thermosensitivity of nanogels was preserved irrespective of whether the nanogels were in or out of the microfiber surface. Additionally, the PVCL nanogels in the structure regulated the degradability of the PVC-modified PVCL nanogels [104]. Madhusudana et al. synthesized dual-responsive nanogels by copolymerization of N-vinyl caprolactam (VCL) and acrylamidoglycolic acid (AGA) for applications in cancer therapy. The in-vitro release of the anticancer drug 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu) from VCL-AGA nanogels was influenced by both pH and temperature [105] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Dual-responsive nanogels based on N-vinyl caprolactam (VCL), which illustrate an increase in drug release at high pH, and the polymer network structure is collapsed at high temperature resulting in lower drug release. Adapted from Ref. [105] reproduced by permission of Elsevier.

Other previously studied thermosensitive nanogels with polymers bearing amide groups are also introduced in Table 1. Parameters such as size, interactions, thermosensitive part, therapeutic agent, and application are provided for better comparison.

Table 1.

Components and applications of investigated thermosensitive nanogels containing polymers bearing amide groups. “-“ means there is no therapeutic agent introduced in the reference paper and only thermosensitive drug carrier was synthesized and prepared.

| Component * | Thermosensitive Part |

Size (nm) | Therapeutics | Application/Properties | Interactions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P(NIPAM-AA) | NIPAM | 125–325 | - | heart repairing | hydrophobic and electrostatic | [106] |

| PTEGDA-b- P(NIPAM-co-NMA) |

NIPPAM | 300–480 | DOX | thermo-responsive | hydrophilic | [107] |

| PEI-g-PNIPAM | NIPAM | 200–350 | plasmid gene P53 | pH sensitive shell/temperature sensitive core |

ionic | [108] |

| P(NIPAM-co- DMAEMA-co-AFA) |

NIPAM | 100 | Cis | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [109] |

| CS-NIPAM -MAA- |

NIPAM | 235 | DOX | pH-/thermo-sensitive | electrostatic | [110] |

| starch-g -PNIPAM/ Fe3O4 |

NIPAM | 67–79 | MTX | magnetic and temperature responsive |

hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [111] |

| NIPAM- (PAMAM) |

NIPAM | 200 | Mall B | drug delivery system against cancer cells |

hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [112] |

| (PNIPAM) | NIPAM | 356 | BSA | controlled protein delivery |

hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [113] |

| PAMAM G3 –PNIPAM |

NIPAM | 200 | 5-Fu | enhancing 5-fluorouracil loading; cancer therapy |

hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [114] |

| P(NIPPAM-AMPS)- TEGDMA |

NIPAM | 199–2211 | DOX | pH-/thermo-sensitive | covalent | [115] |

| NIPAM- (dPG) -PANI |

NIPAM | 155–240 | Anti-cancer drug | efficient in-vivo photothermal cancer therapy | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [79] |

| mPEG-NIPAM- AA-MEA | NIPPAM | 52–144 | DOX | pH-/thermo-sensitive | electrostatic | [116] |

| PEDOT-NIPAM | NIPPAM | 264 | Cur | thermo-responsive | ionic | [117] |

| PNIPAM/(SA-GO) | NIPPAM | 75–375 | DOX | thermo-responsive | electrostatic | [118] |

| Alg-NIPAM | NIPPAM | 180 | DOX | redox-, pH- and thermo-sensitive |

electrostatic | [119] |

| PNIPAM-g-PEI | NIPAM | 300 | Toxic protein Ricin A (RA) encoding plasmid DNA (pRA-EGFR) |

thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [120] |

| (NIPAM-co-AA) | NIPAM | 70–130 | 5-Fu | pH-/thermo-sensitive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [121] |

| P(NIPAM-NBD-SP) | NIPAM | 90–130 | - | thermo-responsive | covalent | [122] |

| NIPAM- PEDOT-PES |

NIPPAM | 195–295 | DOX | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [123] |

| NIPAM-AA-PEGDA | NIPAM | 178–954 | Mt | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [124] |

| Salep-GO-NIPAM | NIPAM | 93 | Df and DOX | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [125] |

| PDEAEMA-Fe3O4 | PDEAAM | 150–320 | - | magnetic and thermo-sensitive |

electrostatic | [66] |

| PDEAEMA - EGDMA | PDEAAM | 160–360 | - | pH-/thermo-sensitive | electrostatic | [126] |

| PAA- b-PDEAAM |

PDEAAM | 10–110 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [92] |

| (DEA)/(DMA) | PDEAAM | 165–288 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [95] |

| (DEA)/(DMA) | PDEAAM | 280–440 | - | thermo-responsive | ionic | [93] |

| (PDEAAM) | PDEAAM | 65–185 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [127] |

| PEO-b-PDEAAM | PDEAAM | 30–150 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [94] |

| PDEAEMA | PDEAAM | 200–800 | Coumarin | thermo-responsive | covalent | [128] |

| PVCL-PAA | PVCL | 175–300 | Diclofenac | thermo-responsive | [129] | |

| PVCL-Dex-MA | PVCL | 100–400 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic | [130] |

| PVCL-PEGMA | PVCL | 80–420 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophilic | [131] |

| Fib-g-PVCL | PVCL | 150–170 | 5-Fu and Meg | thermo-responsive | ionic | [132] |

| PVCL | PVCL | 140–280 | - | nanogel with microfiber | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [104] |

| PVCL-co-VFA and P(VP-co-VFA) |

PVCL | 70–180 | - | pH-/thermo-sensitive | ionic | [133] |

| PDEAEMA/PVCL Dex-MA |

PVCL | 700–500 | DOX | - | [77] | |

| PVCL-AGA | PVCL | 50–100 | 5-Fu | pH-/thermo-sensitive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [105] |

| PVCL-co-IA | PVCL | 140–360 | DOX | pH-/thermo-sensitive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [134] |

| P(VCL-co-AAPBA) | PVCL | 120–250 | Insulin | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic and electrostatic | [135] |

| PVCL-PEGDA | PVCL | 50–120 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [103] |

| P(AETAC-X) - PNVCL |

PVCL | 155–770 | - | thermo-responsive | ionic | [136] |

| P(ODGal- VCL-MAA) |

PVCL | 100–190 | DOX | redox-, pH- and thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [137] |

| Por–PEG–PCL | PVCL | 100–250 | - | thermo-responsive | electrostatic attraction and hydrophobic interaction | [138] |

| POEOMA- b-PVCL |

PVCL | 150–920 | NR as drug model | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [139] |

| P(VCL/AAEMA /OEGMA) |

PVCL | 90–135 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [140] |

| PDEGA-b- PDMA-b-PVCL |

PVCL | 20–400 | - | thermo-responsive | covalent | [141] |

* Full names of abbreviations are available in Appendix A.

3.2. Polymers Bearing Polyether Groups

PEG

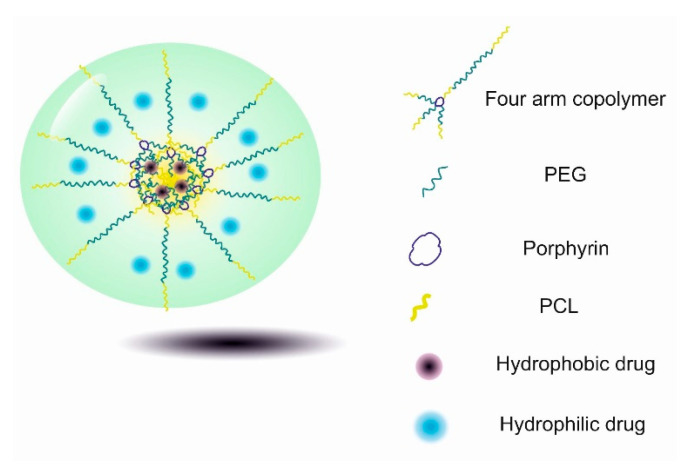

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is another important water-soluble, thermoresponsive polymer. The LCSTs of PEG-based polymers can be regulated by copolymerization with hydrophobic units [142]. Hydrophobic units like methyl and ethyl groups can regulate the polarity and temperature-responsiveness of the polymer within a physiological temperature range [143]. The composition of the monomers, molecular weight, concentration, and ionic strength of the solution considerably affect the LCST of PEG-based copolymers [144]. Xia Dong et al. synthesized a thermosensitive fluorescent nanogel using the four-arm PEG–PCL for bio-imaging applications. The results of the study demonstrated the superior capability of PEG–PCL as a drug carrier for tumour cells. Further, the PEG–PCL nanogels showed fluorescent activity in vivo while satisfying biocompatibility requirements, which made this nanogel system a suitable drug carrier for tumour-targeted delivery [138] (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Thermosensitive fluorescent nanogels based on the four-arm PEG–PCL copolymer for co-delivery of hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs.

3.3. Polymers Bearing Vinyl Ether Groups

3.3.1. PMEO2MA

Poly (2-[2-methoxyethoxy] ethyl methacrylate) (PMEO2MA) is an amphiphilic and biocompatible polymer that contains PVE functional groups (O(CH=CH2)2). The phase transition behaviour of PMEO2MA is similar to PNIPAM, which enables this polymer to be used as a thermosensitive material in biomedical applications [145]. París et al. investigated the phase transition temperature of P(MEO2MA-co-DMAEMA) hydrogel. The copolymer was synthesized via free radical polymerization and the LCSTs of hydrogels with different contents of MEO2MA were investigated in PBS solution. The results demonstrated that the hydrogel was temperature and pH sensitive and LCST of the hydrogel could be tuned by changing MEO2MA content, ionic strength or the environment pH [146]. In another study, Shen et al. prepared a core–shell thermosensitive nanogel using reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer polymerization based on PEG as the core and oligo (ethylene glycol) (OEG) as the outer layer of nanogels. MEO2MA was introduced as a thermoresponsive moiety. The synthesized nanogels with an average diameter of 40–80 nm had negligible cytotoxicity when tested on A549 cells [147].

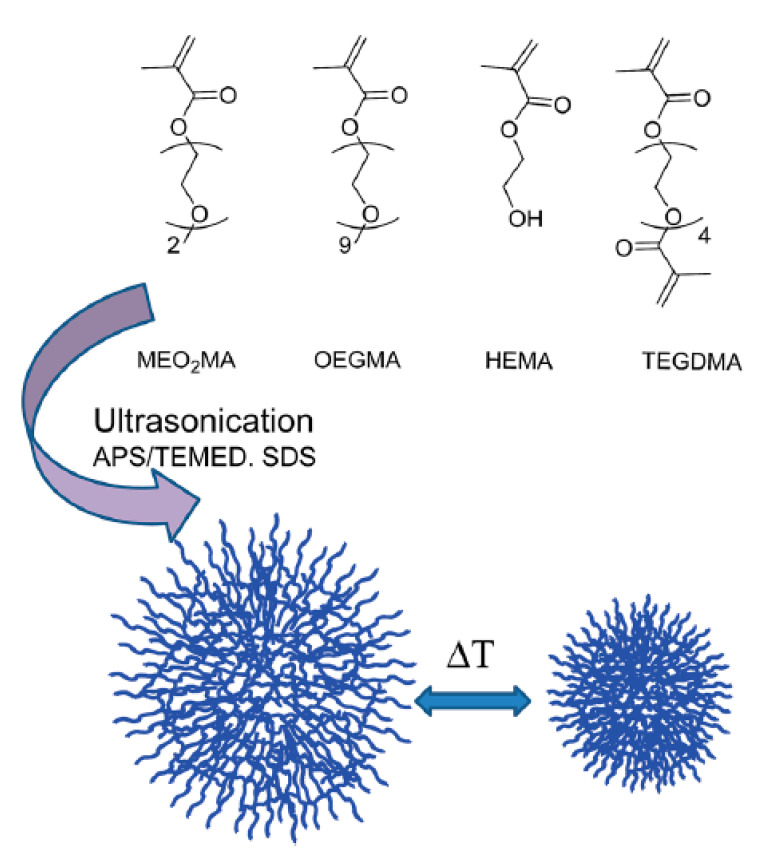

Biglione et al. synthesized a thermosensitive nanogel based on ethylene glycol using a facile ultra-sonication technique. Nanogels with 70 to 180 nm diameter were prepared using MEO2MA and oligo (ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylates (OEGMA) as temperature-responsive moieties and tetra ethylene glycol di-methacrylate (TEGDMA) as the crosslinker. Cytotoxicity and cell uptake evaluations were performed on A549 cells using RhB for labelling. The results indicate that the nanogels had appropriate cytotoxicity and cell permeation profiles [148] (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Thermosensitive nanocarriers based on MEO2MA and OEGMA with TEGDMA as the crosslinker. Adapted from Ref. [148] reproduced by permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry.

3.3.2. OEGMA

Oligo (ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate (OEGMA) has attracted attention as a new type of thermosensitive hydrogel [149]. Similar to PNIPAM, the LCST transition of OEGMA-based hydrogels is not very sensitive to external conditions. Therefore, ionic strength, concentration, and pH do not have a significant impact on the LCST transition of poly (OligoPOEGMA) [150]. Moreover, POEGMA polymers demonstrate exciting characteristics, including high anti-folding, nontoxicity, limited hysteresis, as well as adjustable temperature sensitivity [151]. Lutz et al. synthesized copolymers of MEO2MA and OEGMA via atom transfer radical polymerization and observed possible control of LCST between 26 and 90 °C by altering the monomer compositions [152]. Consequently, a large number of different types of polymers [153,154,155], micelles [156,157], vesicles [158], micro/nanogels [159], and smart POEGMA-based hydrogels [160] have been synthesized and investigated.

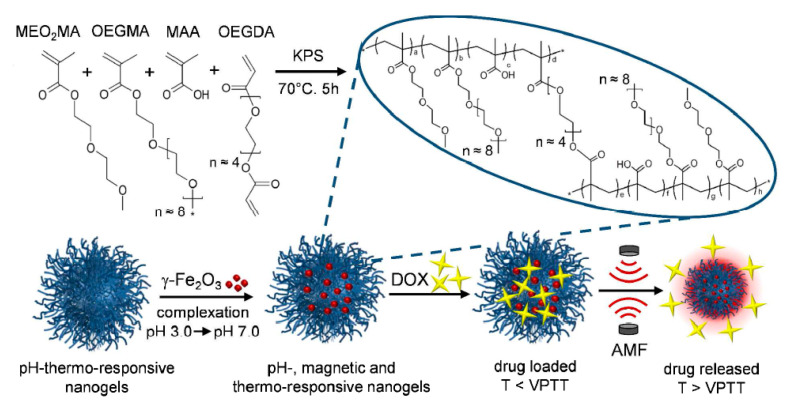

OEGMA-based thermoresponsive materials are widely used as drug carrier hydrogels and nanogels [161,162]. Cortes et al. prepared a thermosensitive and magnetic-responsive nanogel for intracellular remote release of DOX. The prepared nanogels had a diameter from 320 to 460 nm, and their LCST was about 47 °C, which was appropriate for a thermal, magnetic hyperthermia strategy. It was also demonstrated that DOX release from the nanogels increased by the application of an alternating magnetic field [163] (Figure 9). When a high-frequency magnetic field is applied to magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), they can generate heat, which is useful for hyperthermia treatment and acts as driving force for drug release [164]. The thermosensitive structures were used as chemical sensors and indicators. For instance, Liu and et al. synthesized OEG-based thermoresponsive, comb-like polymers via free radical polymerization, which was used as a temperature and pH-responsive sensor [165].

Figure 9.

Temperature- and magnetic-field-responsive nanogels based on OEGMA for intracellular remote release of DOX. Adapted from Ref. [163] reproduced by permission of American Chemical Society.

Previously studied thermosensitive nanogels with polymer-bearing vinyl ether groups are also shown in Table 2. Parameters such as size, interactions, thermosensitive part, therapeutic agent and application are all summarized.

Table 2.

Components and applications of investigated thermosensitive nanogels containing polymers bearing vinyl ether groups. ”-“means there is no therapeutic agent introduced in the reference paper and only thermosensitive drug carrier was synthesized and prepared.

| Component * | Thermosensitive Part |

Size (nm) | Therapeutics | Application/Properties | Interactions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO-Au @PEG | PEG | 15–57 | TZ | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [166] |

| (PEG-b-PADMO) | PEG | 10–80 | - | thermo-responsive | covalent | [142] |

| P(PEG-CPP-SA) | PEG | 80–215 | DOX | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [167] |

| PEG-PPG-PEG | PEG | 12*322 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [168] |

| PEEP-PEG-PEEP | PEG | 150–650 | DOX | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [169] |

| PEG-PLL-PLA-HA | PEG | 160–220 | BSA | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [170] |

| P(MEA-co-PEGMEA) | PEGMEA | 28–100 | thermo-responsive | ionic | [171] | |

| LAEMA-b-(PEGMA-co-LAEMA) | PEGMA | 34–315 | Pt, BSA, BG | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [172] |

| PEGMA-CVP | PEGMA | 85–205 | RhB | thermo-responsive | ionic | [173] |

| PEGMA- Maleimide-dithiol |

PEGMA | 10–192 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophilic | [174] |

| Hg NPs@ P(MEO2MA -co-OEGMA) |

MEO2MA, OEGMA | 65 | Bupivacaine | thermo-responsive | covalent and electrostatic | [161] |

| MEO2MA-PEGMA | MEO2MA | 40–80 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophilic | [147] |

| DMDEA- OEGMA-BADS |

OEGMA | 17–58 | Paclitaxel, DOX | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic | [159] |

| P[(LAEMA-MA)-b -(DEGMA-MBAM-LAEMA)] |

DEGMA | 60–180 | IAZA | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic | [175] |

| MEO2MA – OEGMA-HEMA |

MEO2MA, OEGMA | 71–180 | RhB as label | thermo-responsive | covalent | [148] |

| MEO2MA-OEGMA | MEO2MA, OEGMA | 45 | DOX | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [176] |

| PCL-b-P(MEO2MA-co-OEGMA) Mn-Zn-Fe2O4 |

MEO2MA, OEGMA | 33–129 | DOX | temperature and magnetic responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [177] |

| Clay/ P(MEO2MA -co- POEGMA) |

MEO2MA, OEGMA | 200–400 | - | nanogel/hydrogel nanocomposite | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [160] |

| MEO2MA-ChS @Carbon QDs | MEO2MA | 125–350 | DOX | pH-/thermo-sensitive | electrostatic | [26] |

| CMC-MEO2MA-OEOMA-DMA | MEO2MA | 10 | DOX | pH-/thermo-sensitive | electrostatic | [178] |

| Ag-Au @ MEO2MA-HA |

MEO2MA | 10*60 | TZ | HA as targeting, bimetallic NP as imaging | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [179] |

| QDs-SEMA- PMEO2MA |

MEO2MA | 6 | - | smart luminescent | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [180] |

| Ag/Au @PS- MEO2MA-co- MEO5MA |

MEO2MA | 20–40 | Cur | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [181] |

| P(MEO2MA-co-OEGMA-co-MAA) | OEGMA | 260–650 | DOX | temperature and magnetic sensitive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic and electrostatic | [163] |

| dPG-OEGMA-DEGMA | OEGMA | 50–200 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [182] |

| HA-P(DEGMA-co-OEGMA) | OEGMA | 150–214 | hydrophobic dye | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [183] |

| P(MEODEGM- AEMA-MPC) |

MEODEGM | 45–282 | insulin | thermo-responsive | Ionic and electrostatic | [54] |

* Full names of abbreviations are available in Appendix A.

3.4. Hydrophilic Polymers Bearing Hydrophobic Groups

The second approach to developing thermosensitive polymers is using hydrophobic moieties/polymers alongside hydrophilic materials. The most widely used hydrophilic materials are polysaccharides due to their biocompatibility. Different hydrophobic materials are used to conjugate on hydrophilic units to form thermosensitive materials. Many studies have been performed based on this approach, and different hydrophobic materials, such as cholesterol [184,185], poly L-lactide (PLLA) [186,187,188,189], beta glycerophosphate (β-GP) [190,191] and pluronic F127 (F127) [192,193] have been used to synthesize thermosensitive hydrogels and nanogels for biomedical applications.

3.4.1. Cholesterol-Bearing Polymers

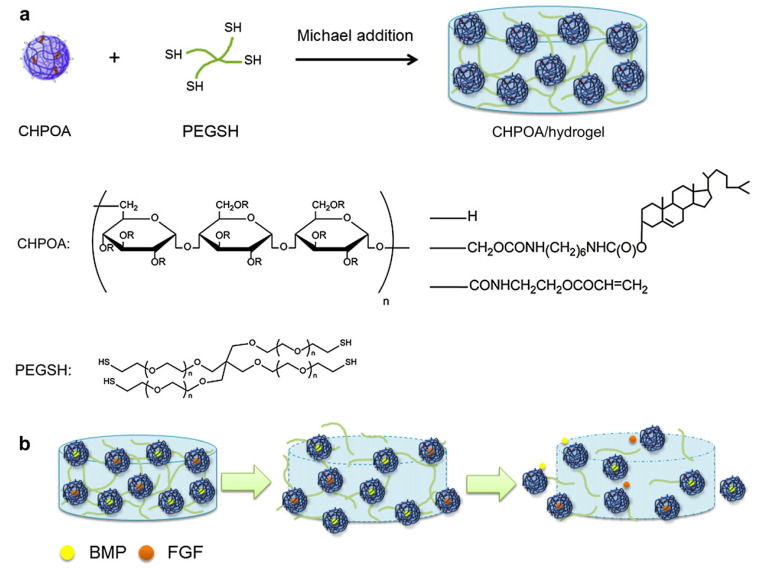

Cholesterol is an organic and hydrophobic molecule that exists in the mammalian body (component of the plasma membrane) and helps to make hormones, vitamin D, and compounds that aid in food digestion. In a few studies, cholesterol was used with pullulan (Plu) for nanogel formation and self-assembly of micelles [194,195,196]. Thara et al. prepared a self-assembled thermosensitive nanogel using cholesterol as a thermosensitive agent bearing hydroxypropyl cellulose (HP-Clu) with LCST of 50 °C. The diameter of nanogels was about 100 nm and 1500 nm at 37 °C and 60 °C in PBS, respectively [185]. In another study, Fujioka et al. synthesized cholesterol-bearing Plu nanogel for the delivery of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP2) and Fibroblast growth factor-18 (FGF18) delivery. The results showed that the delivery of two proteins by the cholesterol-based nanogels aided in the regeneration of bone in vivo in a mouse model [197]. The protein exchange reaction, such as serum albumin with trapped BMP2 and FGF18 molecules, causes growth factor release over 8 weeks to maintain the BMP2 concentration at a certain level around the bone defects in the in-vivo condition. The schematic synthesis followed by growth factor delivery is depicted in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Cholesterol-bearing pullulan biodegradable nanogels for bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) and fibroblast growth factor 18 (FGF18) delivery for bone regeneration. (a) Synthesis of the acryloyl-group-bearing CHP (CHPOA)/hydrogel block and CHPOA nanogel and the chemical structure of pentaerythritol tetra (mercaptoethyl) polyoxyethylene (PEGSH). (‘R’ in CHPOA is H (glucose), cholesterol, and acryloyl). (b) Schematic diagram shows the release of FGF18 and BMP2 from cholesterol-bearing pullulan nanogels (green arrow represents the protein exchange reaction of serum albumin with FGF18 and BMP2). Adapted from Ref. [197] reproduced by permission of The Elsevier.

3.4.2. PLLA-Bearing Polymers

Mechanical strength and the favourable degradation rate of aliphatic polyesters, such as PLLA, poly (lactide-glycolic acid) (PLGA), and PCL, make these polymers very attractive for the preparation of thermoresponsive nanogels. These hydrophobic polymers are mostly used in tissue engineering for constructing biodegradable scaffolds. However, mass transport of oxygen, nutrients and growth factors in such scaffolds is poor, and cell adhesion to the scaffold surface due to the hydrophobicity of polyesters is poor. Na et al. synthesized poly (l-lactic acid)/poly (ethylene glycol) and alternating multi-block temperature-responsive nanoparticles for anticancer drug delivery. The cytotoxicity of the nanoparticles was investigated with Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells, and the results indicated that cell toxicity was temperature dependent and increased with increasing temperature from 37 °C to 42 °C [188]. Nagahama et al. prepared lysozyme-loaded Dex-g-PLLA nanogels and investigated the effect of the hydrophobic unit on the sustained release of lysozyme by comparing the release from Dex-g-PLLA conjugate with dextran-cholesterol. The synthesized Dex-g-PLLA nanogels had low critical aggregation concentrations. The results indicated that the Dex-g-PLLA nanogel has a high potential for protein delivery with sustained release of lysozyme for one week without denaturation [187]. Kyo et al. prepared Plu-g-PLLA nanogels with 150–800 nm diameters for sustained release of DOX. The PLLA in Plu-g-PLLA serves to induce self-assembly of nanogel and improves the loading of hydrophobic drugs [71]. In a recent study, Jung et al. developed Plu-g-PLLA nanogels with succinic anhydride (SA) to deliver lysozyme as a protein drug. The average diameters of the thermosensitive nanogels were 190 nm and 540 nm at 4 °C and 37 °C, respectively. In-vivo studies in nude mice indicated the sustained release of the drug [198].

3.4.3. PLLA Bearing Polymers

Pluronic F127 is a hydrophilic non-ionic copolymer, based on non-toxic FDA-approved PEG and polypropylene glycol (PPG) segments, which is widely used in biomedical applications [192,199,200,201,202,203]. Sharma et al. developed a thermosensitive nanogel based on pluronic F127 as the carrier for the delivery of lidocaine (Lid) and prilocaine (Pl) and demonstrated by in-vitro and in-vivo experiments that the thermosensitivity of the carrier improves the delivery of Lid and PI [193]. Choi et al. prepared a nano-sponge based on heparin (Hep) and pluronic F127 and used it as a thermosensitive carrier for the controlled release of growth factors (bFGF, VEGF, BMP-2 and HGF) [204].

Previously studied thermosensitive nanogels with hydrophilic polymers bearing hydrophobic groups are shown in Table 3. Parameters such as size, interactions, thermosensitive part, therapeutic agent, and application are all summarized.

Table 3.

Components and applications of investigated thermosensitive nanogels containing hydrophilic polymers bearing hydrophobic groups. ”-“means there is no therapeutic agent introduced in the reference paper and only thermosensitive drug carrier was synthesized and prepared.

| Component * | Thermosensitive Part |

Size (nm) | Therapeutics | Application/Properties | Interactions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POP-PS | POP | 250–600 | hGH | thermo-responsive | ionic and hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [205] |

| cholesterol bearing HP-Clu |

Chl | 29–82 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [185] |

| PLLA-ChS Nisin |

PLLA | 180–300 | nisin | target delivery for infection disease | esterification | [206] |

| Succinylated pullulan -g- PLLA |

PLLA | 190–520 | lysozyme | thermo-responsive | electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions | [198] |

| S-Plu-g-OLLA | PLLA | 250–450 | amino acids | thermo-responsive | electrostatic | [207] |

| Plu-g-PLLA | PLLA | 202–341 | DOX | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [71] |

| Fe3O4@mSiO2-PEO-PLA | PLLA | 85–150 | DOX | thermo-responsive | esterification | [208] |

| Plu-g- PLLA | PLLA | 120–160 | DOX | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic | [209] |

| F-127 and Hep | F-127 | 50–525 | bFGF, HGF VEGF, BMP-2, |

thermo-responsive | ionic | [204] |

| ChS - β-GP | β-GP | 100–500 | ethosuximide | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic | [210] |

| P(GME-co-EGE) | P(GME-co-EGE) | 110–160 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic | [211] |

| F-127 and T80 | F-127 | 32.5 | Lid and Pl | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [193] |

| F-127 and Hep | F-127 | 133 | Cis | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [212] |

| PEO-PPO- PEO |

PPO | 60–360 | Mc | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [213] |

| Bi2O3 @PVA | PVA | 80–185 | TZ | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic and covalent | [214] |

| Gel A-GA | Gel A | 60–250 | - | thermo-responsive | - | [215] |

| HP-Clu and PMMA | HP-Clu | 150–240 | - | pH-/thermo-sensitive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [216] |

| HP-Clu- (PIA-co-PMA) | HP-Clu | 100–610 | DOX | pH-/thermo-sensitive | electrostatic | [217] |

| NAGA -DAAM | NAGA | 50–600 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic and hydrophilic | [218] |

| P(L-Asp-co- PEG)- capryl | caprylic acid | 7–180 | - | thermo-responsive | hydrophobic interaction | [219] |

* Full names of abbreviations are available in Appendix A.

4. Conclusions

This review describes the synthesis and applications of thermoresponsive nanogels for targeted and controlled drug delivery. Thermoresponsive nanogels are discussed based on their thermally sensitive polymeric moieties. NIPAM is one of the most studied thermosensitive polymers that have been frequently used to prepare nanoparticles, hydrogels and nanogels for biomedical applications. However, non-biodegradability is limiting the use of NIPAM in clinical applications. Researchers are developing other thermoresponsive materials that are biodegradable for clinical applications while also possessing the rapid and sharp LCST of NIPAM. Materials that possess both hydrophobic and hydrophilic moieties in their molecular structure can induce nanogel formation and thermosensitivity. Based on the stated characteristics of thermosensitive nanogels, and from the authors’ perspective, thermosensitive polymers can be divided into four groups, including those bearing amide, ether and vinyl ether and hydrophilic polymers bearing hydrophobic groups. Generally, the above-mentioned thermosensitive polymers are conjugated to polysaccharides for augmenting biocompatibility as well as other desirable properties. As an alternative approach, hydrophilic polymers can be combined with hydrophobic materials such as PLLA and cholesterol to form thermosensitive nanogels. Four groups of thermosensitive materials were covered in this review, and some of the materials that are used in the synthesis of thermosensitive nanogels were presented. Multi-responsive nanogels, especially those with thermosensitive functionality, are commonly used in a vast number of biomedical applications, including cancer therapy, targeted delivery and in-situ gelation for drug release and entrapment; therefore, thermosensitive nanogels, with their invaluable functions, will become even more remarkable and important structures for drug delivery and tissue engineering applications in foreseeable future.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Abbreviations.

| Component | Abbreviation | Component | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| (2-acetoacetoxyethyl) methacrylate | AAEMA | 1,3-bis(carboxyphenoxy) propane | CPP |

| 1-vinylimidazole | Vim | 2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethyl meth acrylate) | MeO2MA |

| 2-(5,5-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-2-yloxy) ethyl acrylate | DMDEA | 2-(acetylthio) ethyl methacrylate | AcSEMA |

| 2,2-bis(2-oxazoline) | BOX | 2-aminoethyl methacrylamide hydrochloride | AEMA |

| 2-dimethyl(aminoethyl) methacrylate | DMAEM | 2-dimethylmaleinimido ethylacrylamide | DMIAAm |

| 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate | HEMA | 2-lactobionamidoethyl methacrylamide | LAEMAm |

| 2-methacryloyloxyethyl acrylate | MEA | 2-methoxyethyl acrylate | MEA |

| 3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate) | MPMA | 3-{[(2R)-2-(octadecylamino)-3-phenyl propanoyl]amino}butyrate | TEAB |

| 3-acrylamidophenylboronic acid | AAPBA | 3-gluconamidopropyl methacrylamide | GAPMA |

| 4-(2-acryloylaminoethylamino)-7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole | NBDAA | 4-acrylamidofluorescein | AFA |

| 5-fluorouracil | 5-Fu | 6-O-vinyladipoyl-D-galactose | ODGal |

| Acetamidophenol | AP | Acrylamide | AAM |

| Acrylamidoglycolic acid | AGA | Acrylic acid | AA |

| Alginate | Alg | Atom transfer radical polymerization | ATRP |

| Basic fibroblast growth factor | bFGF | Beta glactosidase | BG |

| Beta glycerophosphate | β-GP | Bevacizumab | Bz |

| Bis (2-acryloyloxyethyl) disulfide | BADS | Bisacrylamide | BAM |

| Bismuth (III) oxide | Bi2O3 | Bone morphogenetic protein 2 | BMP-2 |

| Bovine serum albumin | BSA | Bupivacaine | BV |

| Butyl methacrylate | BMA | Butyl methylacrylate | PIB |

| Butyl methylacrylate | BMA | Carboxymethyl cellulose sodium salts | CMC |

| Carboxymethyl hexanoyl chitosan | CHChS | Cellulose | Clu |

| Chitosan | CHS | Cholesterol | Chol |

| Chondroitin sulfate | CS | Cisplatin | CIS |

| Cloud point temperature | CPT | Coumarin 102 | C 102 |

| Covinyl pyrrolidone | CVP | Curcumin | Cur |

| Cytochrome C | Cyt C | Dendritic polyglycerol | dPG |

| Deoxyribonucleic acid-acrylamide | DNA-AAM | Dextran | Dex |

| Dextran methacrylates | Dex-MA | Di(ethylene glycol) methyl ethyl methacrylate | DEGMA |

| Diacetone acrylamide | DAAM | Dibucaine | Dc |

| Diclofenac | Df | Dimethyl maleinimido acrylamide | DMIAAM |

| Doxorubicin | Dox | Ethosuximide | ESM |

| Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate | EGDMA | Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate | EGDMA |

| Ethylene glycole | EG | Fibrinogen | Fib |

| Fibroblast growth factor 18 | FGF18 | Food and Drug Administration | FDA |

| Gelatin type A | Gel A | Glutaraldehyde | GA |

| Graphene oxide | GO | Heparin | Hep |

| Hollow gold nanoparticle | HGNP | Human growth hormone | hGH |

| Human serum albumin | HAS | Hyaluronic acid | HA |

| Hydroxymethyl acrylamide | HMAA | Hydroxypropyl cellulose | HP-Clu |

| Indomethacin | Imc | Iodoazomycin Arabinofuranoside | IAZA |

| Itaconic acid | IA | Lewis lung carcinoma | LLC |

| Lidocaine | Lid | Lower critical aggregation concentration | LCAC |

| Lower critical solution temperature | LCST | L-Proline | L-Pro |

| Maleic acid | MA | Maleimide dithiol | MDT |

| Malloapelta B | Mall B | Megestrol acetate | Meg |

| Melatonin | Mt | Mesoporous silica | mSiO2 |

| Methacrylate | MA | Methacrylic Acid | MAA |

| Methotrexate | MTX | Methoxy-poly(ethylene glycol) | Met-PEG |

| Monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol) | mPEG | Muscone | Mc |

| N, N-di ethylacrylamide | DEAAM | N,N′-methylenebis(acrylamide) | MBAM |

| N,N-diethylacrylamide | DEA | N,N-dimethylacrylamide | DMA |

| N,N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate | DMAEMA | N-acryloyl-3-aminophenylboronic acid | APBA |

| N-acryloylglycinamide | NAGA | Naphthalimide-based dye | NPTUA |

| Nile red | NR | Nitrobenzoxadiazole | NDB |

| Nitrobenzoxadiazole | NBD | N-methylolacrylamide | NMA |

| N-tert-butyl acrylamide | NTBA | N-vinylcaprolactam | NVCL |

| N-vinylformamide | VFA | N-vinylpyrrolidone | VP |

| Oligo (ethylene glycol) | OEG | Oligo (ethylene glycol) methacrylates | OEGMA |

| Oligo (ethylene glycol)methyl ether methacrylate | MEO5MA | Oligo (ethylene oxide) monomethyl ether methacrylate | OEOMA |

| Oligo (L-lactide) | OLA | Paclitaxel | PTX |

| Phenylboronic acid | PBA | Phenylethynesulfonamide | PES |

| Phosphate-buffered saline | PBS | Photochromic spiropyran | SP |

| Pluronic F127 | F127 | Poloxamer 407 | P407 |

| Poly (2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethyl meth acrylate)) | PMEO2MA | Poly (2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethyl methacrylate) | PMEO2MA |

| Poly (2-(diethylamino)ethyl) methacrylate | PDEAEMA | Poly (2-aminoethyl methacrylamide hydrochloride) | PAEMA |

| Poly (2-Ethoxy-2-oxo-1,3,2-dioxaphospholane) | PEEP | Poly (2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline) | piPOz |

| Poly (2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) | PMPC | poly (2-methoxyethyl acrylate) | PMEA |

| Poly (2-methylthioethyl glycidyl ether) | PMTEGE | Poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) | PEDOT |

| Poly (acrylamide) | PAM | Poly (acrylonitrile) | PAN |

| Poly (amino carbonate urethane) | PACU | Poly (caprolactone) | PCL |

| Poly (ether) | PE | Poly (ethyl glycidyl ether) | PEGE |

| Poly (ethylene glycol dimethacrylate) | PEGDMA | Poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate | PEGDA |

| Poly (ethylene glycol) methacrylates | PEGMA | Poly (ethylene glycol) methyl ether acrylate | PEGMEA |

| Poly (ethylene glycole) | PEG | Poly (ethylene oxide) | PEO |

| Poly (glycidol) | PGL | Poly (glycidyl methyl ether) | PGME |

| Poly (lactide co-glycoside) | PLLA-co-GS | Poly (lactide-glycolic acid) | PLGA |

| Poly (L-alanine) | PLA | Poly (L-aspartic acid) | P(L-Asp) |

| Poly (L-lactide) | PLLA | Poly (L-lysine) | PLL |

| Poly (methacrylic acid) | PMA | Poly (methoxydiethylene glycol methacrylate) | PMEODEGM |

| Poly (methyl glycidyl ether) | PGME | Poly (N, N-di ethylacrylamide) | PDEAAM |

| Poly (N,N-dimethylacrylamide) | PDMA | Poly (N-acryloyl-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-oxazolidine | PADMO |

| Poly (N-isopropyl meth acryl amide) | PNIPMAM | Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) | PNIPAM |

| Poly (N-n-propylacrylamide) | PNNPAM | Poly (N-vinyl caprolactam) | PVCL |

| Poly (oligo (ethylene glycol) methacrylates) | POEGMA | Poly (organo phosphazene) | POP |

| Poly (phenylboronate ester) acrylate | PPBDEMA | Poly (propylene oxide) | PPO |

| Poly (sodium 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonate) | PAMPS | Poly (sodium styrenesulfonate) | PSSNa |

| Poly (urethane) | PU | Poly (vinyl ether) | PVE |

| Poly [(3-acrylamidopropyl)-trimethylammonium chloride] | PAMPTMA | Poly acrylamide | PAA |

| Poly ethylenimine | PEI | Poly Oligo (ethylene oxide) methyl ether methacrylate | POEOMA |

| Poly propylene glycol | PPG | Poly tetra (ethylene glycol) diacrylate | PTEGDA |

| Polyacrylic acid | PAA | Polyamidoamine | PAMAM |

| Polyaniline | PANI | Polyglycerol | PG |

| Polyvinyl alcohol | PVA | Porphyrin | Por |

| Prednisone | Pn | Prilocaine | Pl |

| Propranolol | Ppl | Propyl acrylic acid | PAA |

| Protamine | Pt | Protamine sulfate | PS |

| Pullulan | Plu | Quantum dots | QDs |

| Rhodamine B | RhB | Ricin A | RA |

| Salicylic acid | SCA | Sebacic acid | SA |

| Sodium 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropane sulfonate | AMPS | Sodium alginate | SA |

| spiropyran | SP | Styrene | ST |

| Succinic anhydride | SA | Succinylated pullulan | S-Plu |

| Temozolomide | TZ | Tetraethylene glycol dimethacrylate | TEGDMA |

| Tween 80 | T80 | Vascular endothelial growth factor | VEGF |

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hoare T.R., Kohane D.S. Hydrogels in drug delivery: Progress and challenges. Polymer. 2008;49:1993–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2008.01.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarwan T., Kumar P., Choonara Y.E., Pillay V. Hybrid thermo-responsive polymer systems and their biomedical applications. Front. Mater. 2020;7:73. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2020.00073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fundueanu G., Constantin M., Bucatariu S., Ascenzi P. Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-N-isopropylmethacrylamide) Thermo-Responsive Microgels as Self-Regulated Drug Delivery System. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2016;217:2525–2533. doi: 10.1002/macp.201600324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barati D., Shariati S.R.P., Moeinzadeh S., Melero-Martin J.M., Khademhosseini A., Jabbari E. Spatiotemporal release of BMP-2 and VEGF enhances osteogenic and vasculogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial colony-forming cells co-encapsulated in a patterned hydrogel. J. Control. Release. 2016;223:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarvestani A.S., Xu W., He X., Jabbari E. Gelation and degradation characteristics of in situ photo-crosslinked poly(L-lactide-co-ethylene oxide-co-fumarate) hydrogels. Polymer. 2007;48:7113–7120. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2007.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phan V.H.G., Thambi T., Duong H.T.T., Lee D.S. Poly(amino carbonate urethane)-based biodegradable, temperature and pH-sensitive injectable hydrogels for sustained human growth hormone delivery. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–12. doi: 10.1038/srep29978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fundueanu G., Constantin M., Bucatariu S., Ascenzi P. pH/thermo-responsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-maleic acid) hydrogel with a sensor and an actuator for biomedical applications. Polymer. 2017;110:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2017.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato Y., Yamamoto K., Horiguchi S., Tahara Y., Nakai K., Kotani S., Oseko F., Pezzotti G., Yamamoto T., Kishida T., et al. Nanogel tectonic porous 3D scaffold for direct reprogramming fibroblasts into osteoblasts and bone regeneration. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15824. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33892-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han L.H., Suri S., Schmidt C.E., Chen S. Fabrication of three-dimensional scaffolds for heterogeneous tissue engineering. Biomed. Microdevices. 2010;12:721–725. doi: 10.1007/s10544-010-9425-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi L., Wang F., Zhu W., Xu Z., Fuchs S., Hilborn J., Zhu L., Ma Q., Wang Y., Weng X., et al. Self-Healing Silk Fibroin-Based Hydrogel for Bone Regeneration: Dynamic Metal-Ligand Self-Assembly Approach. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017;27:1–14. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201700591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vilaça H., Castro T., Costa F.M.G., Melle-Franco M., Hilliou L., Hamley I.W., Castanheira E.M.S., Martins J.A., Ferreira P.M.T. Self-assembled RGD dehydropeptide hydrogels for drug delivery applications. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2017;5:8607–8617. doi: 10.1039/C7TB01883E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arsalani N., Kazeminava F., Akbari A., Hamishehkar H., Jabbari E., Kafil H.S. Synthesis of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane nano-crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol)-based hybrid hydrogels for drug delivery and antibacterial activity. Polym. Int. 2019;68:667–674. doi: 10.1002/pi.5748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao W.C., Lilienthal S., Kahn J.S., Riutin M., Sohn Y.S., Nechushtai R., Willner I. PH-and ligand-induced release of loads from DNA-acrylamide hydrogel microcapsules. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:3362–3373. doi: 10.1039/C6SC04770J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan C., Wang D.A. A biodegradable PEG-based micro-cavitary hydrogel as scaffold for cartilage tissue engineering. Eur. Polym. J. 2015;72:651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2015.02.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim Y.S., Cho K., Lee H.J., Chang S., Lee H., Kim J.H., Koh W.G. Highly conductive and hydrated PEG-based hydrogels for the potential application of a tissue engineering scaffold. React. Funct. Polym. 2016;109:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2016.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Q., Weber C., Schubert U.S., Hoogenboom R. Thermoresponsive polymers with lower critical solution temperature: From fundamental aspects and measuring techniques to recommended turbidimetry conditions. Mater. Horiz. 2017;4:109–116. doi: 10.1039/C7MH00016B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dadashi S., Boddohi S., Soleimani N. Preparation, characterization, and antibacterial effect of doxycycline loaded kefiran nanofibers. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019;52:979–985. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molaei M.J. A review on nanostructured carbon quantum dots and their applications in biotechnology, sensors, and chemiluminescence. Talanta. 2019;196:456–478. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zong H., Xia X., Liang Y., Dai S., Alsaedi A., Hayat T., Kong F., Pan J.H. Designing function-oriented artificial nanomaterials and membranes via electrospinning and electrospraying techniques. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2018;92:1075–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aderibigbe B., Naki T. Design and Efficacy of Nanogels Formulations for Intranasal Administration. Molecules. 2018;23:1241. doi: 10.3390/molecules23061241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park S., Choi D., Jeong H., Heo J., Hong J. Drug Loading and Release Behavior Depending on the Induced Porosity of Chitosan/Cellulose Multilayer Nanofilms. Mol. Pharm. 2017;14:3322–3330. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.González E., Frey M.W. Synthesis, characterization and electrospinning of poly (vinyl caprolactam-co-hydroxymethyl acrylamide) to create stimuli-responsive nanofibers. Polymer. 2017;108:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2016.11.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shariati S.R.P., Moeinzadeh S., Jabbari E. Nanofiber Based Matrices for Chondrogenic Differentiation of Stem Cells. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2016;16:8966–8977. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2016.12737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jabbari E., Yang X., Moeinzadeh S., He X. Drug release kinetics, cell uptake, and tumor toxicity of hybrid VVVVVVKK peptide-assembled polylactide nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013;84:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bordat A., Boissenot T., Nicolas J., Tsapis N. Thermoresponsive polymer nanocarriers for biomedical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019;138:167–192. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H., Di J., Sun Y., Fu J., Wei Z., Matsui H., Del C., Alonso A., Zhou S. Biocompatible PEG-Chitosan@Carbon Dots Hybrid Nanogels for Two-Photon Fluorescence Imaging, Near-Infrared Light/pH Dual-Responsive Drug Carrier, and Synergistic Therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015;25:5537–5547. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201501524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boddohi S., Moore N., Johnson P.A., Kipper M.J. Polysaccharide-Based Polyelectrolyte Complex Nanoparticles from Chitosan, Heparin, and Hyaluronan. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:1402–1409. doi: 10.1021/bm801513e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussain M., Xie J., Hou Z., Shezad K., Xu J., Wang K., Gao Y., Shen L., Zhu J. Regulation of Drug Release by Tuning Surface Textures of Biodegradable Polymer Microparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:14391–14400. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b02002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bamberger D., Hobernik D., Konhäuser M., Bros M., Wich P.R. Surface Modification of Polysaccharide-Based Nanoparticles with PEG and Dextran and the Effects on Immune Cell Binding and Stimulatory Characteristics. Mol. Pharm. 2017;14:4403–4416. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soni S., Babbar A.K., Sharma R.K., Maitra A. Delivery of hydrophobised 5-fluorouracil derivative to brain tissue through intravenous route using surface modified nanogels. J. Drug Target. 2006;14:87–95. doi: 10.1080/10611860600635608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy E.A., Majeti B.K., Mukthavaram R., Acevedo L.M., Barnes L.A., Cheresh D.A. Targeted Nanogels: A Versatile Platform for Drug Delivery to Tumors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011;10:972–982. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryu J.H., Bickerton S., Zhuang J., Thayumanavan S. Ligand-decorated nanogels: Fast one-pot synthesis and cellular targeting. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:1515–1522. doi: 10.1021/bm300201x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adamo G., Grimaldi N., Campora S., Bulone D., Bondì M.L., Al-Sheikhly M., Sabatino M.A., Dispenza C., Ghersi G. Multi-functional nanogels for tumor targeting and redox-sensitive drug and siRNA delivery. Molecules. 2016;21:1594. doi: 10.3390/molecules21111594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Multi-Functional Nanogels for Tumor Targeting and Redox-Sensitive Drug and siRNA Delivery—PubMed. [(accessed on 23 May 2020)]; doi: 10.3390/molecules21111594. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27886088/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Li Y., Bui Q.N., Duy L.T.M., Yang H.Y., Lee D.S. One-Step Preparation of pH-Responsive Polymeric Nanogels as Intelligent Drug Delivery Systems for Tumor Therapy. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19:2062–2071. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuo Y., Jiao Z., Ma L., Song P., Wang R., Xiong Y. Hydrogen bonding induced UCST phase transition of poly(ionic liquid)-based nanogels. Polymer. 2016;98:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2016.06.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Indulekha S., Arunkumar P., Bahadur D., Srivastava R. Dual responsive magnetic composite nanogels for thermo-chemotherapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2017;155:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miao C., Li F., Zuo Y., Wang R., Xiong Y. Novel redox-responsive nanogels based on poly(ionic liquid)s for the triggered loading and release of cargos. RSC Adv. 2016;6:3013–3019. doi: 10.1039/C5RA21820A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao Y., Dong C.M. Quadruple thermo-photo-redox-responsive random copolypeptide nanogel and hydrogel. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2018;29:927–930. doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2017.09.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee J.-Y., Chung S.-J., Cho H.-J., Kim D.-D. Bile acid-conjugated chondroitin sulfate A-based nanoparticles for tumor-targeted anticancer drug delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015;94:532–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmid D., Park C.G., Hartl C.A., Subedi N., Cartwright A.N., Puerto R.B., Zheng Y., Maiarana J., Freeman G.J., Wucherpfennig K.W., et al. T cell-targeting nanoparticles focus delivery of immunotherapy to improve antitumor immunity. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01830-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Q., Colazo J., Berg D., Mugo S.M., Serpe M.J. Multiresponsive Nanogels for Targeted Anticancer Drug Delivery. Mol. Pharm. 2017;14:2624–2628. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tran N., Webster T.J. Magnetic nanoparticles: Biomedical applications and challenges. J. Mater. Chem. 2010;20:8760–8767. doi: 10.1039/c0jm00994f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marek S.R., Conn C.A., Peppas N.A. Cationic nanogels based on diethylaminoethyl methacrylate. Polymer. 2010;51:1237–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2010.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin Y., Hu B., Yuan X., Cai L., Gao H., Yang Q. Nanogel: A Versatile Nano-Delivery System for Biomedical Applications. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:290. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12030290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vinogradov S.V. Nanogels in the race for drug delivery. Nanomedicine. 2010;5:165–168. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H., Ke F., Mararenko A., Wei Z., Banerjee P., Zhou S. Responsive polymer-fluorescent carbon nanoparticle hybrid nanogels for optical temperature sensing, near-infrared light-responsive drug release, and tumor cell imaging. Nanoscale. 2014;6:7443–7452. doi: 10.1039/C4NR01030B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park K.M., Son J.Y., Choi J.H., Kim I.G., Lee Y., Lee J.Y., Park K.D. Material for the Treatment of Urinary Incontinence. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:1979–1984. doi: 10.1021/bm401787u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang R., Tsai W.-B. Fabrication of Photothermo-Responsive Drug-Loaded Nanogel for Synergetic Cancer Therapy. Polymers. 2018;10:1098. doi: 10.3390/polym10101098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song L., Liang X., Yang S., Wang N., He T., Wang Y., Zhang L., Wu Q., Gong C. Novel polyethyleneimine-R8-heparin nanogel for high-efficiency gene delivery in vitro and in vivo. Drug Deliv. 2018;25:122–131. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2017.1417512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Śliwa T., Jarzębski M., Andrzejewska E., Szafran M., Gapiński J. Uptake and controlled release of a dye from thermo-sensitive polymer P(NIPAM-co-Vim) React. Funct. Polym. 2017;115:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2017.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Y., Xiao K., Luo J., Lee J., Pan S., Lam K.S. A novel size-tunable nanocarrier system for targeted anticancer drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 2010;144:314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou T., Xiao C., Fan J., Chen S., Shen J., Wu W., Zhou S. A nanogel of on-site tunable pH-response for efficient anticancer drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:4546–4557. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhuchar N., Sunasee R., Ishihara K., Thundat T., Narain R. Degradable thermoresponsive nanogels for protein encapsulation and controlled release. Bioconjug. Chem. 2012;23:75–83. doi: 10.1021/bc2003814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tan J.P.K., Tan M.B.H., Tam M.K.C. Application of nanogel systems in the administration of local anesthetics. Local Reg. Anesth. 2010;3:93–100. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S7977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kohli E., Han H.Y., Zeman A.D., Vinogradov S.V. Formulations of biodegradable Nanogel carriers with 5′-triphosphates of nucleoside analogs that display a reduced cytotoxicity and enhanced drug activity. J. Control. Release. 2007;121:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang X., Cheng D., Liu L., Li X. Development of poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylate) nanogel for effective oral insulin delivery. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2018;23:351–357. doi: 10.1080/10837450.2017.1295064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Backer L., Braeckmans K., Stuart M.C.A., Demeester J., De Smedt S.C., Raemdonck K. Bio-inspired pulmonary surfactant-modified nanogels: A promising siRNA delivery system. J. Control. Release. 2015;206:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yukia Y., Nochi T., Kong I.G., Takahashi H., Sawada S.I., Akiyoshi K., Kiyono H. Nanogel-based antigen-delivery system for nasal vaccines. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2013;29:61–72. doi: 10.1080/02648725.2013.801226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Novel Inulin-Based Mucoadhesive Micelles Loaded With Corticosteroids as Potential Transcorneal Permeation Enhancers—PubMed. [(accessed on 23 May 2020)]; doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2017.05.005. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28512019/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Asghar K., Qasim M., Dharmapuri G., Das D. Investigation on a smart nanocarrier with a mesoporous magnetic core and thermo-responsive shell for co-delivery of doxorubicin and curcumin: A new approach towards combination therapy of cancer. RSC Adv. 2017;7:28802–28818. doi: 10.1039/C7RA03735J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luan S., Zhu Y., Wu X., Wang Y., Liang F., Song S. Hyaluronic-Acid-Based pH-Sensitive Nanogels for Tumor-Targeted Drug Delivery. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017;3:2410–2419. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mohtashamian S., Boddohi S., Hosseinkhani S. Preparation and optimization of self-assembled chondroitin sulfate-nisin nanogel based on quality by design concept. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;107:2730–2739. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu Z., Zhang X., Guo H., Li C., Yu D. An injectable and glucose-sensitive nanogel for controlled insulin release. J. Mater. Chem. 2012;22:22788–22796. doi: 10.1039/c2jm34082h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abandansari H.S., Abuali M., Nabid M.R., Niknejad H. Enhance chemotherapy efficacy and minimize anticancer drug side effects by using reversibly pH- and redox-responsive cross-linked unimolecular micelles. Polymer. 2017;116:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2017.03.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pikabea A., Ramos J., Papachristos N., Stamopoulos D., Forcada J. Synthesis and characterization of PDEAEMA-based magneto-nanogels: Preliminary results on the biocompatibility with cells of human peripheral blood. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2016;54:1479–1494. doi: 10.1002/pola.27996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen S., Bian Q., Wang P., Zheng X., Lv L., Dang Z., Wang G. Photo, pH and redox multi-responsive nanogels for drug delivery and fluorescence cell imaging. Polym. Chem. 2017;8:6150–6157. doi: 10.1039/C7PY01424D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deng L., Zhai Y., Lin X., Jin F., He X., Dong A. Investigation on properties of re-dispersible cationic hydrogel nanoparticles. Eur. Polym. J. 2008;44:978–986. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2008.01.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dong H., Xu Q., Li Y., Mo S., Cai S., Liu L. The synthesis of biodegradable graft copolymer cellulose-graft-poly(L-lactide) and the study of its controlled drug release. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2008;66:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guo Y., Wang X., Shu X., Shen Z., Sun R.-C. Self-Assembly and Paclitaxel Loading Capacity of Cellulose-graft-poly(lactide) Nanomicelles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:3900–3908. doi: 10.1021/jf3001873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cho J.-K., Park W., Na K. Self-organized nanogels from pullulan- g -poly(L-lactide) synthesized by one-pot method: Physicochemical characterization and in vitro doxorubicin release. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009;113:2209–2216. doi: 10.1002/app.30049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schauperl M., Podewitz M., Waldner B.J., Liedl K.R. Enthalpic and Entropic Contributions to Hydrophobicity. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016;12:4600–4610. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dhanya S., Bahadur D., Kundu G.C., Srivastava R. Maleic acid incorporated poly-(N-isopropylacrylamide) polymer nanogels for dual-responsive delivery of doxorubicin hydrochloride. Eur. Polym. J. 2013;49:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2012.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qian K., Ma Y., Wan J., Geng S., Li H., Fu Q., Peng X., Kan X., Zhou G., Liu W., et al. The studies about doxorubicin-loaded p (N-isopropyl-acrylamide-co-butyl methylacrylate) temperature-sensitive nanogel dispersions on the application in TACE therapies for rabbit VX2 liver tumor. J. Control. Release. 2015;212:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu T., Geng S., Li H., Wan J., Peng X., Liu W., Zhao Y., Yang X., Xu H. The stimuli-responsive multiphase behavior of core-shell nanogels with opposite charges and their potential application in in situ gelling system. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2015;136:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Quan C.Y., Sun Y.X., Cheng H., Cheng S.X., Zhang X.Z., Zhuo R.X. Thermosensitive P (NIPAAm-co-PAAc-co-HEMA) nanogels conjugated with transferrin for tumor cell targeting delivery. Nanotechnology. 2008;19 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/27/275102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aguirre G., Villar-Alvarez E., González A., Ramos J., Taboada P., Forcada J. Biocompatible stimuli-responsive nanogels for controlled antitumor drug delivery. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2016;54:1694–1705. doi: 10.1002/pola.28025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou L., Zhang F. Thermo-sensitive and photoluminescent hydrogels: Synthesis, characterization, and their drug-release property. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2011;31:1429–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2011.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Molina M., Wedepohl S., Calderón M. Polymeric near-infrared absorbing dendritic nanogels for efficient in vivo photothermal cancer therapy. Nanoscale. 2016;8:5852–5856. doi: 10.1039/C5NR07587D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kubota K., Hamano K., Kuwahara N., Fujishige S., Ando I. Characterization of Poly(N-isopropylmethacrylamide) in Water. Polym. J. 1990;22:1051–1057. doi: 10.1295/polymj.22.1051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Djokpé E., Vogt W. N-isopropylacrylamide and N-isopropylmethacrylamide: Cloud points of mixtures and copolymers. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2001;202:750–757. doi: 10.1002/1521-3935(20010301)202:5<750::AID-MACP750>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cors M., Wrede O., Genix A.C., Anselmetti D., Oberdisse J., Hellweg T. Core-Shell Microgel-Based Surface Coatings with Linear Thermoresponse. Langmuir. 2017;33:6804–6811. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b01199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peters J.T., Hutchinson S.S., Lizana N., Verma I., Peppas N.A. Synthesis and characterization of poly(N-isopropyl methacrylamide) core/shell nanogels for controlled release of chemotherapeutics. Chem. Eng. J. 2018;340:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Deshpande S., Sharma S., Koul V., Singh N. Core-shell nanoparticles as an efficient, sustained, and triggered drug-delivery system. ACS Omega. 2017;2:6455–6463. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.7b01016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Idziak I., Avoce D., Lessard D., Gravel D., Zhu X.X. Thermosensitivity of Aqueous Solutions of Poly( N,N -diethylacrylamide) Macromolecules. 1999;32:1260–1263. doi: 10.1021/ma981171f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Colonne M., Chen Y., Wu K., Freiberg S., Giasson S., Zhu X.X. Binding of streptavidin with biotinylated thermosensitive nanospheres based on poly(N,N-diethylacrylamide-co-2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) Bioconjug. Chem. 2007;18:999–1003. doi: 10.1021/bc060302b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kishi R., Matsuda A., Miura T., Matsumura K., Iio K. Fast responsive poly(N, N-diethylacrylamide) hydrogels with interconnected microspheres and bi-continuous structures. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2009;287:505–512. doi: 10.1007/s00396-009-2002-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Horák D., Matulka K., Hlídková H., Lapčíková M., Beneš M.J., Jaroš J., Hampl A., Dvořák P. Pentapeptide-modified poly(N,N-diethylacrylamide) hydrogel scaffolds for tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2011;98 B:54–67. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Scherzinger C., Lindner P., Keerl M., Richtering W. Cononsolvency of poly(N, N-diethylacrylamide) (PDEAAM) and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) based microgels in water/methanol mixtures: Copolymer vs core-shell microgel. Macromolecules. 2010;43:6829–6833. doi: 10.1021/ma100422e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ngadaonye J.I., Geever L.M., Killion J., Higginbotham C.L. Development of novel chitosan-poly(N,N-diethylacrylamide) IPN films for potential wound dressing and biomedical applications. J. Polym. Res. 2013;20 doi: 10.1007/s10965-013-0161-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Blasco E., Schmidt B.V.K.J., Barner-Kowollik C., Piñol M., Oriol L. Dual thermo- and photo-responsive micelles based on miktoarm star polymers. Polym. Chem. 2013;4:4506–4514. doi: 10.1039/c3py00576c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Delaittre G., Save M., Gaborieau M., Castignolles P., Rieger J., Charleux B. Synthesis by nitroxide-mediated aqueous dispersion polymerization, characterization, and physical core-crosslinking of pH- and thermoresponsive dynamic diblock copolymer micelles. Polym. Chem. 2012;3:1526–1538. doi: 10.1039/c2py20084h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li X., Li X., Shi X., Qiu G., Lu X. Thermosensitive DEA/DMA copolymer nanogel: Low initiator induced synthesis and structural colored colloidal array’s optical properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2017;96:484–493. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2017.08.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grazon C., Rieger J., Sanson N., Charleux B. Study of poly(N,N-diethylacrylamide) nanogel formation by aqueous dispersion polymerization of N,N-diethylacrylamide in the presence of poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(N,N-dimethylacrylamide) amphiphilic macromolecular RAFT agents. Soft Matter. 2011;7:3482–3490. doi: 10.1039/c0sm01181a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lu X., Sun M., Barron A.E. Non-ionic, thermo-responsive DEA/DMA nanogels: Synthesis, characterization, and use for DNA separations by microchip electrophoresis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;357:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.01.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rieger J., Grazon C., Charleux B., Alaimo D., Jérôme C. Pegylated thermally responsive block copolymer micelles and nanogels via in situ RAFT aqueous dispersion polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2009;47:2373–2390. doi: 10.1002/pola.23329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yu Z., Gu H., Tang D., Lv H., Ren Y., Gu S. Fabrication of PVCL-co-PMMA nanofibers with tunable volume phase transition temperatures and maintainable shape for anti-cancer drug release. RSC Adv. 2015;5:64944–64950. doi: 10.1039/C5RA10808J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Roh Y.H., Moon J.Y., Hong E.J., Kim H.U., Shim M.S., Bong K.W. Microfluidic fabrication of biocompatible poly(N-vinylcaprolactam)-based microcarriers for modulated thermo-responsive drug release. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2018;172:380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lynch B., Crawford K., Baruti O., Abdulahad A., Webster M., Puetzer J., Ryu C., Bonassar L.J., Mendenhall J. The effect of hypoxia on thermosensitive poly(N-vinylcaprolactam) hydrogels with tunable mechanical integrity for cartilage tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2017;105:1863–1873. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kutsevol N., Glamazda A., Chumachenko V., Harahuts Yu., Stepanian S.G., Plokhotnichenko A.M., Karachevtsev V.A. Behavior of hybrid thermosensitive nanosystem dextran-graft-PNIPAM/gold nanoparticles: Characterization within LCTS. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2018;20:236. doi: 10.1007/s11051-018-4331-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen Y., Cheng W., Teng L., Jin M., Lu B., Ren L., Wang Y. Graphene Oxide Hybrid Supramolecular Hydrogels with Self-Healable, Bioadhesive and Stimuli-Responsive Properties and Drug Delivery Application. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2018;303:1–11. doi: 10.1002/mame.201700660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang J., Chen G., Zhao Z., Sun L., Zou M., Ren J., Zhao Y. Responsive graphene oxide hydrogel microcarriers for controllable cell capture and release. Sci. China Mater. 2018;61:1314–1324. doi: 10.1007/s40843-018-9251-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Callejas-Fernández J., Ramos J., Forcada J., Moncho-Jordá A. On the scattered light by dilute aqueous dispersions of nanogel particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;450:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]