Abstract

The purpose of this study is to analyze the effects of TKA under-dimensioning during daily activities. A regular (“control”) size and an undersized design of the same fixed bearing asymmetric PS prosthesis were analyzed during walking and squat using finite element analysis. The two models showed similar internal-external rotations and antero-posterior displacements during both activities. Slightly higher displacements, wider contact areas and lower contact pressure were found in the control size. Post-cam engagement angles were similar on both sizes. Changes in TKA size slightly affected knee kinematics and kinetics, with post-cam related differences leading to minor changes in kinetic patterns.

Keywords: TKA, Kinematics, Kinetics, Undersized implant, Finite element model, Post-cam

1. Introduction

Recent anatomical studies have shown that size and shape of femur and tibia at the knee vary among individuals, most notably between male and female.1, 2, 3 For this reason, many different designs and sizes of total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) are available on the market, in order to provide the surgeons (and therefore the patients) with the most suitable device according to the requirements.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Among the different TKA designs, even focusing on Posterior Stabilized (PS) only, the market offers several different options in terms of implant geometry, post-cam features (design, dimensions and eventual asymmetry) and materials, aimed to improve the implant performances when restoring physiological knee kinematics and kinetics.9, 10, 11 Furthermore, also the implant size is a factor of paramount relevance: this feature, in parallel with the design itself, has a key impact on implant performances and thus great care should be given to this decision. It is nonetheless to consider that having the specific size for each patient is not always possible, if not resorting to custom made devices: for this reason, if the patient geometry is between two sizes, surgeons often have to decide which approach to adopt between oversizing and undersizing.

Several studies on the consequences of oversizing have indeed returned negative outcomes with soft tissue envelope damaging (the overhanging irritates the capsule, the iliotibial band or the collateral ligaments12), patient pain (when implanted following posterior reference, it indeed leads to patellofemoral pressure increase12) and biomechanical functional recovery in terms of stiffness and kinetic results,13, 14, 15 hence it should be avoided when possible. On the other hand, studies on undersizing reported eventual laxity (mainly occurring if following anterior reference 16, 17, 18, 19) or anterior cortical notching issues,20, 21, 22, 23 but overall acceptable (if not even better) results.14,24

To further study the effects of undersizing, hence, a comparative biomechanical analysis of different daily motion tasks was performed between a control PS TKA design and an undersized one. The aim was then to quantify and highlight the eventual disadvantages and issues of this approach, in terms of implant kinematics and kinetics, in order to have the biomechanical background required to justify or eventually deny it.

2. Materials and methods

The finite element model developed for this study was based on a previously validated and published knee finite element model21,24,25 which includes the following features.

2.1. Geometry

The three-dimensional (3D) geometries of the tibial and femoral bones were obtained from Computed tomography (CT) images of a right mechanical equivalent tibial and femoral Sawbones (fourth-generation composite tibia and femur, Pacific Research Laboratories, WA, USA), including cortical bone, cancellous bone and intramedullary canal.26, 27, 28 On such geometries, anatomical landmarks29,30 were identified to detect the anatomical and mechanical axis of the bones, together with the mediolateral one for the tibia and the trans-epicondylar one for the femur; landmarks for the insertion points of medial and lateral collateral ligaments (MCL and LCL) and of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) were also identified.

In this study, the PHYSICA PS Posterior Stabilized fixed bearing (Lima Corporate, San Daniele del Friuli, Udine, Italy) was used. Its PS femoral component is characterized by a J-curve design and by a 3° asymmetric cam and it is available in 10 sizes, with an open box dimensions changing from size to size together with the thin flange, in order to preserve the patient bone stock and to adapt the implant to the dimensions of the anatomical site. Each size of the femoral component can be coupled with the same size and with sizes ±2 with respect to the liner. According to the dimension of the bone two different implants, i.e. size 6 (“control model”) and size 4 (“undersized model”), both right sides, were selected for this study. The CAD file of the prosthesis were then implanted in the finite element model following the proper surgical procedure, provided by the manufacturer. In details, a mechanically aligned position was considered for both the femoral and tibial component.25 The femoral component was posterior referenced positioned, which avoids flexion laxity, but could lead to anterior notching in case of undersizing. The tibial plate is aligned to the anterior border of the cortical bone, which means with a properly sized 6 tibia, a size 4 implant is positioned more anteriorly, anteriorizing also the contact points, according to the matching compatibility the worst case for undersizing was chosen.

3. Material model and properties

Linear elastic models were chosen for all the materials involved in this study, in agreement with previous literature studies21,31, 32, 33, 34: this assumption allows a good approximation of all the mechanical properties, in order to gain a qualitative comparison among different configurations; cortical bone was modeled as transversely isotropic, while the cancellous one was considered isotropic.24,25,31,33,35 Ligaments were considered isotropic and modeled as beams with a specific cross section area and a validated pre-strain21,25,31,33. The materials used for the femoral, tibial and insert components were, respectively, cobalt-chromium-molybdenum alloy (CoCrMo), titanium-aluminum-vanadium alloy (Ti6Al4V) and ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE), assumed to be homogeneous and isotropic.31,33,36, 37, 38 A coefficient of friction of 0.04 was considered for the interaction between the femoral component and the tibial insert.21,25,38,39 The interfaces between prosthetic components and bone were rigidly fixed simulating the effect of a cement (PMMA) layer21,25,38: this latter was applied at the cut surface of the femur in contact with the femoral knee component and at the tibial bone cut in contact with the tibial component, with a constant penetration of 3 mm into the bone (based on a test of different cementing techniques40,41). The material adopted for the cement was considered homogeneous and isotropic as well.28,38,42

A full overview of the material models and properties used in the study is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Material properties of the knee model. For the cortical bone, the direction E3 represents the axial direction. εr represents the pre-strain of the ligaments.

| Material | Model | Young's Modulus [MPa] | Poisson's Ratio | εr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical bone | Transversely Isotropic | E1 = 11,500 | ν12 = 0.31 | NA |

| E2 = 11,500 | ν13 = 0.31 | |||

| E3 = 17,000 | ν23 = 0.51 | |||

| Cancellous bone | Elastic Isotropic | 2130 | 0.30 | NA |

| CoCrMo | Elastic Isotropic | 240,000 | 0.30 | NA |

| Ti6Al4V | Elastic Isotropic | 114,000 | 0.30 | NA |

| UHMWPE | Elastic Isotropic | 724.2 | 0.46 | NA |

| PMMA | Elastic Isotropic | 2620 | 0.30 | NA |

| aMCL | Elastic Isotropic | 196 | 0.45 | 0.04 |

| pMCL | Elastic Isotropic | 196 | 0.45 | 0.03 |

| LCL | Elastic Isotropic | 111 | 0.45 | 0.05 |

3.1. Analyzed configurations and motor tasks

In this study, two different configurations were considered: as control model, a size-6 prosthesis was implanted and as undersized model the size 4 was chosen. No different-sizes combinations were analyzed in this study. Both implants were placed in the same patient bone model, with the size-6 being the proper one for the patient geometries fitting exactly the joint anatomy.

Each configuration was analyzed during dynamically simulated gait and a squat motor tasks, which were replicated applying appropriate forces and kinematics.31,36,37,43,44 In detail, a 10s loaded movement up to 120° was considered for the squat and the boundary conditions (in terms of flexion-extension angle, axial force and anterior-posterior force) were taken accordingly to previous experimental activities45, 46, 47; even if patellar bone and soft tissue envelope were not modeled during the present activity, the adopted boundary conditions take in account also forces exerted by the extensor mechanism and by the collateral ligament using the proper validated pre-strain21,25. As in the experimental tests, the other degrees of freedom were kept free. To reproduce the gait cycle, instead, the flexion extension, anteroposterior force, intra-extra rotation and axial force were imposed accordingly to the ISO-14243-131,36,37 and a duration of 1s was considered for this motor task, following protocols in literature. Similar to previous study, the tibia was considered fixed, in the region of the ankle, for all the analyzed activities.25,31,35,38,48

3.2. Finite element analysis and output

For each configuration, each model was defined using tetrahedrons with element size between 1.5 and 4 mm. To reduce the discretization error, a convergence test was performed to check the mesh quality of the selected element size for every region of the model. Abaqus/Explicit version 2017 (Dassault Systèmes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France) was used to perform all the finite element simulations.

For all the models developed, the tibio-femoral kinematics (in terms of internal-external rotation and anteroposterior translation) were extracted and compared among the configurations. Medial, lateral and post-cam contact areas, pressures and forces were also extracted and investigated.

4. Results

4.1. Motor task: gait

Focusing on contact areas, the two different sizes present similar behavior for what concerns patterns and medial-lateral ratio along the whole motion (as shown in Fig. 1). It is however to highlight that the Control Model returns higher values in terms of contact areas magnitude (as illustrated in Fig. 2 and graphically reported in Fig. 3), which lead consequently to lower contact pressures if compared to the undersized model (as shown in Fig. 4). Furthermore, when considering the contact forces, the medial-lateral subdivision returns to be 60%–40% in the undersized model and 56%–44% for the control size.

Fig. 1.

Medial and Lateral contact areas during the gait cycle in Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

Fig. 2.

Average Medial and Lateral Contact Areas in the two phases of the gait cycle in Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

Fig. 3.

Contact Areas and Stress on the tibial component in two different moments of the gait cycle: Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

Fig. 4.

Average Medial and Lateral Contact Pressures in the two phases of the gait cycle in Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

Both models returned then similar results when analyzing the differences in stance and swing contact force patterns (Fig. 5): stance phase is indeed characterized by a higher force if compared to swing phase, and this explains the values of contact areas found there; greater force is then found on the medial side of the insert rather than on the lateral one.

Fig. 5.

Medial and Lateral contact Forces during the gait cycle in Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

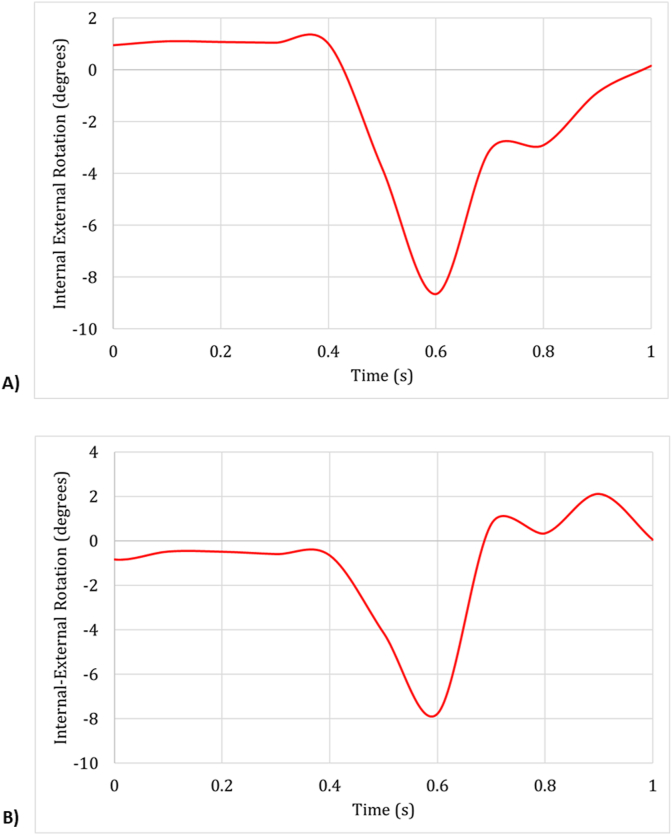

The kinematic results of the two models were found to be in agreement with each other, showing similar internal-external rotations ranges and patterns (Fig. 6) and anteroposterior displacement (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Internal-External rotation angles during the gait cycle in Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

Fig. 7.

AnteroPosterior Displacements during the gait cycle in Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

4.2. Motor task: squat

As reported in Fig. 8, the medial and lateral contact forces are similar for both models up to 70° of flexion; in the undersized model, after 70°, the force on the lateral side starts to be significantly higher than the medial one. The control size, on the other hand, presents more similar values for the contact forces among the two sides.

Fig. 8.

Medial and Lateral contact Forces during squat in Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

Contact areas in medial and lateral sides along the motion task are then represented in Fig. 9: a similar pattern is followed in both sizes and sides, with the area increasing as the flexion angle grows (since the forces increase accordingly) up to 60°, where a plateau starts in correspondence with the post-cam engagement angle. Together with the fact that the control size returns a lower difference between the results in the two compartments, a remarkable feature is the almost symmetrical behavior found between flexion and extension movement.

Fig. 9.

Medial and Lateral contact areas during squat in Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

Dealing with kinematics, the two models resulted to be comparable in terms of internal-external rotation: both sizes indeed showed similar behavior, with an initial internal rotation followed by an external one up to 11° in the range of flexion between 40° and 60° (as shown in Fig. 10). Anteroposterior displacement (Fig. 11) then returned to be similar to other prosthesis designs,20 with an initial anterior translation followed by a posterior displacement at increased flexion angles; the range of displacement spans around 10 mm in both configurations.

Fig. 10.

Internal-External rotation angles during squat in Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

Fig. 11.

AnteroPosterior Translations during squat for Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

Fig. 12, Fig. 13 highlight the biomechanical results, in terms of contact areas and location of the contact point in the post-cam system of the control and the undersized.

Fig. 12.

Post-Cam contact areas during squat in Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

Fig. 13.

Post-Cam contact point Vertical Displacements during squat in Undersized (A) and Control (B) Models.

5. Discussions

5.1. Motor task: gait

The difference in contact areas found in the two different sizes returned a narrower force distribution, and hence higher pressures, related to the overall undersized prosthesis: this factor could represent one of the main causes of wear, so this stands as an important point in the kinetic comparison. It is also to be noted that the medio-lateral force distribution found in the control size, being 56%–44%, is slightly more similar to the physiological goal of 55%–45% (see Fig. 5)21,33; in this regard, it is however to consider that the positioning of the femoral and tibial components along medio-lateral direction may influence the force distribution, and having a smaller size allows more flexibility in the foresaid positioning (with consequently higher attention required from the surgeon). Having a smaller implant and a bigger femoral condylar curvature gives more freedom to position the tibial plate properly.

On the other hand, it is to note that the control size prosthesis, having larger dimensions, compared to the undersized one, presents slightly higher displacements: this behavior is in agreement with the physiological knee roll-back motion,46,47,49,50 and in the cases studied it returns to be proportional to the size of the implant itself. This increased displacement could be however, be considered responsible to an eventual wear of the polyethylene insert, but it is to be considered that the contribute of this factor to the actual failure of the implant is negligible compared to other factors as the stressed involved in this configuration are lower thanks to the bigger dimensions.

5.2. Motor task: squat

The kinematic results concerning internal-external rotation, then, were compared with literature and have been found to be in agreement with studies by Victor et al.46 and by Kwack,51 who analyzed native knee specimens using a knee-joint robotic machine under boundary conditions similar to the ones used in the present activity and also similar to Hill49 and Iwaki.50

Anteroposterior displacement (Fig. 11), spanning around 10 mm for both configurations with an initial anterior translation followed by a posterior displacement at increased flexion angles, was found in agreement with what reported in literature by Walker52 and by Arnout20 and reflects the physiological behavior of the roll-back sought.

Another difference between the two sizes emerges when dealing with the post-cam system (Figs. 12 and 13): even if the engagement angles of the post-cam returned to be around 70°, comparable with those of other prosthetic models20 and with the physiological cruciate activation angle,53 it is important to mention that size 4 prosthesis is not able to guarantee the contact between the post and the cam in a continuous manner throughout the flexion of the joint. At 90° flexion angle, indeed, the contact point turns to be between the cam and the posterior side of the insert plateau instead of between the post and the cam (as shown in Fig. 10): the main consequence of this behavior results in the force being charged on the plateau rather than on the post, justifying the high values found on the lateral side for this size. The control size, on the other hand, is able to provide a continuous contact between post-cam components and consequently presents more agreeing values for the contact forces, as seen in Fig. 8.

Despite these differences, it is however positively remarkable that in both size configurations the forces are exerted along a proximo-distal direction then preventing insert lift-off (Fig. 14); moreover, the forces change their position accordingly to the relative angle of flexion in order to avoid any luxation of the post-cam mechanism. These findings are also in agreement with other numerical study on asymmetric post-cam design showing closer kinematics compared to symmetric post-cam.54,55

Fig. 14.

Post-Cam force angle during squat in the Control Model.

5.3. Limitations

There are nonetheless limitations and assumptions associated with this study: an ideal alignment and positioning of the prosthesis components were assumed during simulation, so the small postoperative coronal, sagittal, and rotational malalignments eventually occurring in actual TKA surgeries were ignored.56 Moreover, the study is based only on one TKA design and bone geometry and does not take in consideration any bone deformity that could indeed alter the final TKA outcome.43,44,57, 58, 59 Nevertheless, such approach is quite common in the field as the main aim of the study is to focus on one design feature (i.e. the size) and not to include additional variability in the system.24,25,31,34 From a modeling point of view, an assumption is related to the ligaments model, here implemented as a beams; this approach is nonetheless quite common in the literature, with previously validated ligaments model.21 The selection of the behavior of the different materials analyzed needs to be addressed too, being the bony structures (as well as the soft tissues) assumed as linear elastic and homogeneous even if it is well known that the cortical and the cancellous bone contemplate spatial inhomogeneity in their properties.34 Another limitation of this study is in the use of a linear model for the polyethylene, which could provide an overestimation in the local value of stress under plasticization. The aim of this study, however, is mainly to perform a comparison between the two configurations using the same approach and consequently these limitations don't represent cause of issues.

In this study, a full knee model, including pre-strained ligaments, was used. As reported by Innocenti et al.,21 the inclusion of the collateral ligaments in the numerical models is fundamental in order to obtain realistic loads, and therefore bone stress distribution; Godest et al. (2002) described then the role of the surrounding tension within the soft tissues and they reported that both the relative position of the components and the tension of the surrounding soft tissues have an impact on the results.60

6. Conclusions

PS TKA oversizing often leads to issues in joint performances and patient unsatisfaction, mainly due to soft-tissue balancing. On the other hand, undersizing directly influences the joint stability and contact areas (together with contact pressures, boundary conditions being equal), which could lead to slightly higher polyethylene wear rates hence compromising the prosthesis performances.

Clinical results of undersized implants, however, didn't highlight any of these issues and this fact, together with the agreement found in the present study, could represent a valid justification to select undersizing as the optimal approach, with due diligence, when the patient's dimensions are in between two sizes.

Acknowledgement

Research Grant by Lima Corporate.

References

- 1.Harner C.D., Xerogeanes J.W., Livesay G.A. The human posterior cruciate ligament complex: an interdisciplinary study. Ligament morphology and biomechanical evaluation. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(6):736–745. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazzucchelli L., Deledda D., Rosso F. Cruciate retaining and cruciate substituting ultra-congruent insert. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(1):2. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.12.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters C.L., Mulkey P., Erickson J., Anderson M.B., Pelt C.E. Comparison of total knee arthroplasty with highly congruent anterior-stabilized bearings versus a cruciate-retaining design. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:175–180. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3068-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andriacchi T.P., Galante J.O., Fermier R.W. The influence of total knee-replacement design on walking and stair-climbing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(9):1328–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ewald F.C., Jacobs M.A., Miegel R.E., Walker P.S., Poss R., Sledge C.B. Kinematic total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(7):1032–1040. Sep. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelman G.J., Biden E.N., Wyatt M.P., Ritter M.A., Colwell C.W., Jr. Gait laboratory analysis of a posterior cruciate-sparing total knee arthroplasty in stair ascent and descent. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):21–25. doi: 10.1097/00003086-198911000-00006. discussion 25-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schultz R.A., Miller D.C., Kerr C.S., Micheli L. Mechanoreceptors in human cruciate ligaments. A histological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(7):1072–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Victor J., Banks S., Bellemans J. Kinematics of posterior cruciate ligament-retaining and -substituting total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomised outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(5):646–655. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B5.15602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.In Y., Kim J.M., Woo Y.K., Choi N.Y., Sohn J.M., Koh H.S. Factors affecting flexion gap tightness in cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:317–321. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Insall J.N., Hood R.W., Flawn L.B., Sullivan D.J. The total condylar knee prosthesis in gonarthrosis. A five to nine-year follow-up of the first one hundred consecutive replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:619–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laskin R.S., Maruyama Y., Villaneuva M., Bourne R. Deep-dish congruent tibial component use in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;380:36–44. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li G., Most E., Otterberg E. Biomechanics of posterior-substituting total knee arthroplasty: an in vitro study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:214–225. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Most E., Zayontz S., Li G. Femoral rollback after cruciate-retaining and stabilizing total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;410:101–113. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000062380.79828.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakayama K., Matsuda S., Miura H. Contact stress at the post-cam mechanism in posterior-stabilised total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:483–488. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B4.15684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stern S.H., Insall J.N. Posterior stabilized prosthesis. Results after follow-up of nine to twelve years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:980–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belvedere C., Leardini A., Catani F. In vivo kinematics of knee replacement during daily living activities: condylar and post-cam contact assessment by three-dimensional fluoroscopy and finite element analyses. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:1396–1403. doi: 10.1002/jor.23405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catani F., Belvedere C., Ensini A. In-vivo knee kinematics in rotationally unconstrained total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1484–1490. doi: 10.1002/jor.21397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catani F., Ensini A., Belvedere C. In vivo kinematics and kinetics of a bi-cruciate substituting total knee arthroplasty: a combined fluoroscopic and gait analysis study. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1569–1575. doi: 10.1002/jor.20941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez J.A., Bhende H., Ranawat C.S. Total condylar knee replacement: a 20-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;388:10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnout N., Vanlommel L., Vanlommel J. Post-cam mechanics and tibiofemoral kinematics: a dynamic in vitro analysis of eight posterior-stabilized total knee designs. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(11):3343–3353. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Innocenti B., Bilgen Ö.F., Labey L., van Lenthe G.H., Sloten J.V., Catani F. Load sharing and ligament strains in balanced, overstuffed and understuffed UKA. A validated finite element analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(7):1491–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maniar R. Rationale for the posterior-stabilized rotating platform knee. Orthopedics. 2006;29:S23–S27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ranawat C.S., Komistek R.D., Rodriguez J.A., Dennis D.A., Anderle M. In vivo kinematics for fixed and mobile-bearing posterior stabilized knee prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:184–190. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brihault J., Navacchia A., Pianigiani S. All-polyethylene tibial components generate higher stress and micromotions than metal-backed tibial components in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(8):2550–2559. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3630-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Innocenti B., Bellemans J., Catani F. Deviations from optimal alignment in TKA: is there a biomechanical difference between femoral or tibial component alignment? J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(1):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Au A.G., James Raso V., Liggins A.B. Contribution of loading conditions and material properties to stress shielding near the tibial component of total knee replacements. J Biomech. 2007;40(6):1410–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heiner A.D., Brown T.D. Structural properties of a new design of composite replicate femurs and tibias. J Biomech. 2001;34(6):773–781. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soenen M., Baracchi M., De Corte R., Labey L., Innocenti B. Stemmed TKA in a femur with a total hip arthroplasty. Is there a safe distance between the stem tips? J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8):1437. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Innocenti B., Salandra P., Pascale W., Pianigiani S. How accurate and reproducible are the identification of cruciate and collateral ligament insertions using MRI? Knee. 2016;23(4):575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Victor J., Van Doninck D., Labey L., Innocenti B., Parizel P.M., Bellemans J. How precise can bony landmarks be determined on a CT scan of the knee? Knee. 2009;16(5):358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castellarin G., Pianigiani S., Innocenti B. Asymmetric polyethylene inserts promote favorable kinematics and better clinical outcome compared to symmetric inserts in a mobile bearing total knee arthroplasty Knee Surgery. Sports Traumatology. 2019;27(4):1096–1105. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ingrassia T., Nalbone L., Nigrelli V., Tumino V., Ricotta V. Finite element analysis of two total knee prostheses. Int J Interact Des Manuf. 2013;7(2):91. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Innocenti B., Pianigiani S., Ramundo G., Thienpont E. Biomechanical effects of different varus and valgus alignments in medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;31(12):2685–2691. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarathi Kopparti P., Lewis G. Influence of three variables on the stresses in a three-dimensional model of a proximal tibia-total knee implant construct. Bio Med Mater Eng. 2007;17:19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Zayat B.F., Heyse T.J., Fanciullacci N., Labey L., Fuchs-Winkelmann S., Innocenti B. Fixation techniques and stem dimensions in hinged total knee arthroplasty: a finite element study. Arch Orthop Traum Surg. 2016;136(12):1741–1752. doi: 10.1007/s00402-016-2571-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Innocenti B., Robledo H., Bernabe R., Pianigiani S. Investigation on the effects induced by TKA features on tibio-femoral mechanics. Part I: femoral component designs. J Mech Med Biol. 2015;15(2):1540034. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pianigiani S., Alario Bernabé R., Robledo Yagüe H., Innocenti B. Investigation on the effects induced by TKA features on tibio-femoral mechanics part II: tibial insert designs. J Mech Med Biol. 2015;15(2):1540035. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Innocenti B. High congruency MB insert design: stabilizing knee joint even with PCL deficiency. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05764-0. 10.1007/s00167-019-05764-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sobieraj M.C., Rimnac C.M. Ultra high molecular weight polyethylene: mechanics, morphology, and clinical behavior. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2009;2(5):433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.VaninbroukxM, Labey L, Innocenti B, et al. Cementing the femoral component in total arthroplasty: which technique is the best? Knee;16:265. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Vanlommel J., Luyckx J.P., Labey L. Cementing the tibial component in total knee arthroplasty: which technique is the best? J Arthroplasty. 2009;26:492. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.01.107. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waanders D., Janssen D., Mann K. The mechanical effects of different levels of cement penetration at the cement–bone interface. J Biomech. 2010;43:1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Innocenti B., Pianigiani S., Labey L., Victor J., Bellemans J. Contact forces in several TKA designs during squatting: a numerical sensitivity analysis. J Biomech. 2011;44(8):1573–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pianigiani S., Vander Sloten J., Pascale W., Labey L., Innocenti B. A new graphical method to display data sets representing biomechanical knee behaviour. J Exp Orthop. 2015;2(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s40634-015-0034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luyckx T., Didden K., Vandenneucker H., Labey L., Innocenti B., Bellemans J. Is there a biomechanical explanation for anterior knee pain in patients with patella alta? Influence of patellar height on patellofemoral contact force, contact area and contact pressure. J Bone Jt Surg (Br) 2009;91(3):344–350. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B3.21592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Victor J., Labey L., Wong P., Innocenti B., Bellemans J. The Influence of muscle load on tibio-femoral knee kinematics. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:419–428. doi: 10.1002/jor.21019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Victor J., Van Glabbeek F., Vander Sloten J., Parizel P.M., Somville J., Bellemans J. An experimental model for kinematic analysis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(Suppl 6):150–163. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Innocenti B., Truyens E., Labey L., Wong P., Victor J., Bellemans J. Can medio-lateral baseplate position and load sharing induce asymptomatic local bone resorption of the proximal tibia? A finite element study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2009;4:26. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hill P.F., Vedi V., Williams A., Iwaki H., Pinskerova V., Freeman M.A. Tibiofemoral movement 2: the loaded and unloaded living knee studied by MRI. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(8):1196–1198. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b8.10716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iwaki H., Pinskerova V., Freeman M.A. Tibiofemoral movement 1: the shapes and relative movements of the femur and tibia in the unloaded cadaver knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(8):1189–1195. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b8.10717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kwak S.D., Ahmad C.S., Gardner T.R. Hamstrings and iliotibial band forces affect knee kinematics and contact pattern. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:101–108. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walker P.S., Sussman-Fort J.M., Yildirim G., Boyer J. Design features of total knees for achieving normal knee motion characteristics. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(3):475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toutoungi D.E., Lu T.W., Leardini A. Cruciate ligament forces in the human knee during rehabilitation exercises. Clin Biomech. 2000;15(3):176–187. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(99)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yong-Gon K., Juhyun S., Oh-Ryong K. Effect of post-cam design for normal knee joint kinematic, ligament, and quadriceps force in patient-specific posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty by using finite element analysis. BioMed Res Int. 2018:2314–6133. doi: 10.1155/2018/2438980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koh Y., Nam J., Kang K. Effect of geometric variations on tibiofemoral surface and post-cam design of normal knee kinematics restoration. J EXP ORTOP. 2018;5:53. doi: 10.1186/s40634-018-0167-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ritter M.A.1, Davis K.E., Meding J.B., Pierson J.L., Berend M.E., Malinzak R.A. The effect of alignment and BMI on failure of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;7(17):1588–1596. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00772. 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang H.1, Simpson K.J., Ferrara M.S., Chamnongkich S., Kinsey T., Mahoney O.M. Biomechanical differences exhibited during sit-to-stand between total knee arthroplasty designs of varying radii. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(8):1193–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.02.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang J.W.1, Wang C.J. Total knee arthroplasty for arthritis of the knee with extra-articular deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(10):1769–1774. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200210000-00005. Oct. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hazratwala K., Matthews B., Wilkinson M., Barroso-Rosa S. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with extra-articular deformity Arthroplasty. Today Off. 2016;2(1):26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Godest A.C., Beaugonin M., Haug E. Simulation of a knee joint replacement during a gait cycle using explicit finite element analysis. J Biomech. 2002;35:267. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]