Abstract

BACKGROUND

Hepatic lymphangioma, a malformation of the liver lymphatic system, is a rare benign neoplasm and usually coexists with other visceral lymphangiomas. Solitary hepatic lymphangioma is much more rarely seen and could cause a clinical misinterpretation as malignancy.

CASE SUMMARY

A 50-year-old woman with a liver mass of approximately 3.5 cm was initially diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma given the risk factors for liver cancer that she presented with, including Schistosome japonicum infection and jaundice, and also together with imaging results, which showed the mass enhanced quickly in the arterial phase and faded fast in the venous phase. The patient did not have the surgery first but received three rounds of transarterial chemoembolization because of her anxiety and fears for operation. Finally, the patient underwent laparoscopic liver segment 4b resection and cholecystectomy and was discharged from the hospital only 10 d after the operation. The pathological examination indicated the mass as hepatic lymphangioma. The patient has been followed up for 30 mo without recurrence. To raise the awareness of this misdiagnosed case and to better diagnose and treat this rare disease in future, we reviewed the published literature of solitary hepatic lymphangioma for its clinical symptoms, imaging presentation, operative techniques, histology features and prognosis.

CONCLUSION

Solitary hepatic lymphangioma mimicking malignancy makes diagnosis difficult. Complete surgical resection is the first choice to treat solitary hepatic lymphangioma.

Keywords: Hepatic lymphangioma, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Laparoscopic hepatectomy, Trans-arterial chemoembolization, Adult, Case report

Core Tip: Hepatic lymphangioma is an extremely rare benign neoplasm. We presented a case of solitary hepatic lymphangioma with a typical imaging performance of hepatocellular carcinoma, thus misdiagnosed as liver cancer and treated with transarterial chemoembolization for three rounds. Finally, the lesion was removed by liver resection and confirmed as lymphangioma in pathology. The patient recovered well and no recurrence was found during follow up. Published literature with solitary hepatic lymphangioma were reviewed and analyzed. Complete surgical resection is the first choice to treat solitary hepatic lymphangioma.

INTRODUCTION

Lymphangiomas are rare benign masses characterized by dilated lymphatic vessels, usually resulting from blockade of lymphatic reflux or abnormal development of the lymphatic system in embryogenesis[1-4]. The lymphatic system and venous system lack communication, which leads to the malformation of lymphatics. Lymphangioma is significantly associated with chromosome abnormalities, including chromosome X abnormalities (Turner syndrome), trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), trisomy 18, trisomy 13, and triploidy, copy number variants, and genetic mutations such as AKT1, PIK3CA, VEGFR3, and RASA1[5-8]. It is reported that lymphangiomas are more common in neonates and children compared to adults[1,9].

More than 90% of lymphangiomas occur in the lymphatic system outside the abdominal cavity, such as the neck, axilla, mediastinum, and lungs. Less than 5% of intra-abdominal lymphangiomas are described, and the most frequently affected location is the small bowel mesentery, followed by the omentum, mesocolon, and retroperitoneum[9,10]. When lymphangiomas affect multiple organs, including the liver, spleen, soft tissues, serosa (mesentery), peritoneum, retroperitoneum, and skeletal, the situation is named lymphangiomatosis, which could not be eradicated by surgery but may respond to systemic chemotherapy and radiotherapy with limited efficacy and poor prognosis[11-13]. In addition, solitary lesions in the liver are rare and are further classified into capillary lymphangioma, cystic lymphangioma, and cavernous lymphangioma[4,14,15].

When solitary hepatic lymphangioma is presented in a clinical setting, the diagnosis and treatment becomes challenging solitary hepatic due to its rarity, atypical trait, and clinical phenotype. In our case, a rare solitary hepatic lymphangioma resembled the features of liver malignancy. We therefore reviewed the published literature in order to raise concerns of the diagnosis and treatment of this disease.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 50-year-old woman who had a history of a liver tumor for 2 years was admitted to our hepatic surgery center, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

History of present illness

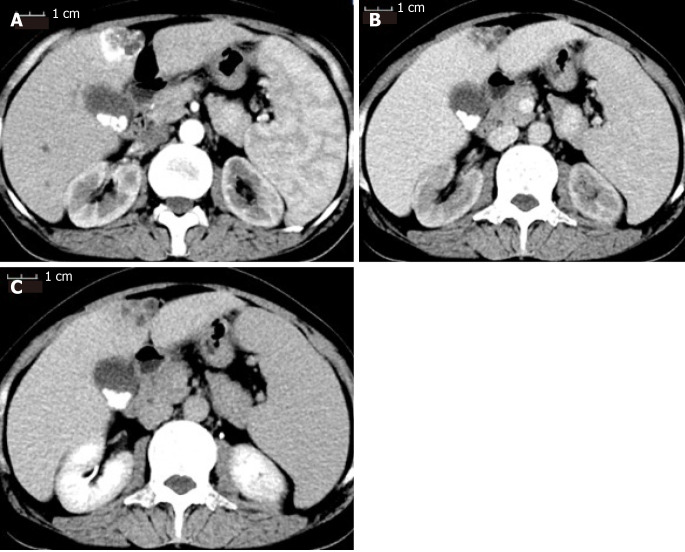

Two years ago, a liver mass was found in her left liver lobe by ultrasound during a regular body check. Then, the patient received an enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan, which showed a regular mass with a diameter around 3.5 cm located in the segment 4b close to falciform ligament. It manifested as a non-rim-like enhancement in the arterial phase (Figure 1A) and nonperipheral washout appearance in the portal venous phase and in delayed scan (Figure 1B and 1C). The lesion was classified as LR-5 according to liver imaging reporting and data system version 2018[16]. Meanwhile, the CT scan revealed multiple gallbladder stones and splenomegaly (Figure 1). The liver lesion was resectable. However, the patient had fears of surgery and concerns of its complications and was unwilling to receive the operation at first. Finally, the patient received transarterial chemoembolization that displayed the abnormal dying lesion consistent with the features of liver malignancy. The patient recovered well and was discharged 2 d after transarterial chemoembolization. One month later, the enhanced CT displayed the similar change of the lesion as described above and iodized oil deposition in the tumor (Figure 2). Then the patient revisited the hospital every 3 mo in the first year and every 6 mo in the second year. During this period, the patient underwent another two rounds of transarterial chemoembolization treatment as the iodized oil deposition decreased. The lesion was not reduced while tumor markers were in the normal range all the time. Later, the patient was tired of numerous follow-ups, overcame the fear of surgery, and decided to have the operation. She was soon transferred to our hepatic surgery center for further treatment.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of the patient before receiving transarterial chemoembolization. A: The mass was enhanced immediately during the arterial phase; B: The enhancement faded away quickly into equal density in the portal venous phase; C: The mass showed hypodensity in the delayed phase. The three phases of the computed tomography scan also showed multiple gallstones and splenomegaly.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of the patient after first transarterial chemoembolization. A: Iodized oil deposition in the tumor was observed in the arterial phase; B: Portal venous phase; C: Delayed phase.

History of past illness

The patient recalled a history of infection of Schistosome japonicum 3 years ago as she was found positive by fecal examination or serology testing during the annual Schistosome japonicum-infection census of Hubei Province, China. She also reported jaundice hepatitis during childhood because of yellowing of skin or sclera.

Physical examination

The physical examination revealed jaundice, and therefore the patient was admitted to the infectious disease department of our hospital first.

Laboratory examinations

After admission, the tests for infection of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Schistosome japonicum, and Treponema pallidum were all negative. Blood tests showed hemoglobin 81 g/L, hematocrit 23%, the average hemoglobin content 22.3 pg, mean corpuscular volume 62.7 fL, total bilirubin 57.6 μmol/L, indirect bilirubin 52.9 μmol/L, and free hemoglobin 121g/L. Gene test confirmed β-thalassemia with IVS654 heterozygous mutation, which could explain hemolytic anemia and splenomegaly. Serological tumor markers including alpha-fetoprotein (13908 IU/mL, normal range: 0-15770 IU/mL), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (24.4 U/mL, normal range: 0-27 U/mL), and carcinoembryonic antigen (2.1 ng/mL, normal range: 0-3.4 ng/mL) were within the normal ranges.

Imaging examinations

No additional imaging examinations were performed for the patient after being transferred to our department.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

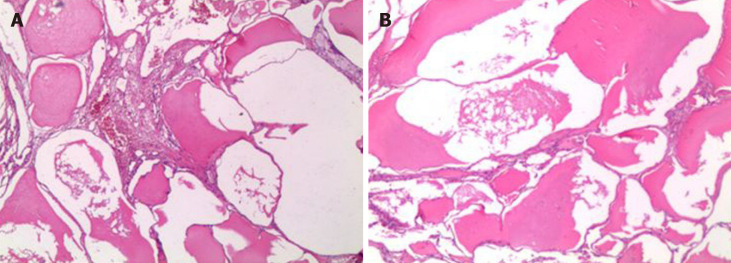

Although tumor markers, evidence of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and Schistosome japonicum infection, and family history did not support the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma, the results of the CT scan could not rule out liver malignancy. The postoperative histological examination of the liver tumor confirmed hepatic lymphangioma (Figure 3). Other confirmed diseases for the patient were chronic cholecystolithiasis and β-thalassemia with IVS654 heterozygous mutation.

Figure 3.

The specimen was examined under microscopy (40 ×). A: The mass was made of dilated-cystic lymphatic lumens lined by endothelium; B: Filled with acidophilic lymph.

TREATMENT

The patient subsequently received laparoscopic liver segment 4b resection and cholecystectomy. During laparotomy, the morphology, texture, and size showed no abnormality. There was a tumor around 4 cm × 3 cm in the segment 4b with a clear boundary and soft quality. No satellite lesions or metastasis was observed. The size of the gallbladder with mild edematous serous membrane adhering to the omentum majus was 10 cm × 7 cm × 3 cm. Liver segment 4b with 2 cm tumor margin and gallbladder were removed by ultrasonic scalpel.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The operation was successfully accomplished. The total operation time was 180 min, and total blood loss was about 50 mL without blood transfusion.

The patient recovered well and was discharged from the hospital 10 d after the surgery. She visited the hospital every 6 mo. There was no recurrence or metastasis during the 30 mo follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Hepatic lymphangioma is rarely seen in our clinical practice especially for the solitary lesion that could be mistakenly diagnosed as liver malignancies or hepatic cystic diseases and the diagnosis can only be confirmed by surgical pathology. Due to its low incidence and few experiences in management, no consensus or guideline is available at present. Therefore, we reviewed the published literature related to the disease[17,18] to gain more experience in the diagnosis and treatment of hepatic lymphangioma.

Based on the reviewed literature (Table 1), hepatic lymphangioma could be presented at any age from newborns to the elderly (average age is 30 years)[19,20]. In our case, the patient was a 50-year-old female. Females have a slightly higher incidence for solitary hepatic lymphangioma compared to males (ratio is 11:8) (Table 1). Clinical manifestation is nonspecific, and most cases are presented as upper abdominal discomfort or pain caused by the lesion compressing adjacent organs. Some cases show no symptoms and are found by routine health examination (Table 1)[21-27]. Thus preoperative diagnosis of the lesion cannot depend on symptoms and signs. Therefore, it is necessary to turn to imaging.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics and manifestations of reviewed solitary hepatic lymphangioma

| No. | Ref. | Year | Age | Sex | Manifestation |

| 1 | Kohashi et al[32] | 2017 | 50 yr | F | Epigastric discomfort |

| 2 | Lee et al[14] | 2016 | 42 yr | F | Right upper abdominal pain |

| 3 | Zouari et al[21] | 2015 | 8 mo | M | Abdominal distention |

| 4 | Nakano et al[19] | 2015 | 18 yr | F | Epigastric pain |

| 5 | Liu et al[22] | 2014 | 41 yr | M | Right upper abdominal pain |

| 6 | Zhang et al[4] | 2013 | 42 yr | F | None |

| 7 | Nazarewski et al[10] | 2013 | 41 yr | F | None |

| 8 | Peña Ros et al[17] | 2013 | 20 yr | F | Abdominal pain |

| 9 | Ak et al[18] | 2012 | 58 yr | F | Weight loss |

| 10 | Huang et al[23] | 2010 | 35 yr | M | Right upper abdominal pain |

| 11 | Matsumoto et al[1] | 2010 | 52 yr | F | Upper abdominal pain |

| 12 | Shahi et al[24] | 2009 | 22 d | M | Abdominal distension |

| 13 | Zeidan et al[25] | 2008 | 23 yr | M | Abdominal pain or vomiting |

| 14 | Stunell et al[36] | 2009 | 30 yr | F | Right upper quadrant pain |

| 15 | Nzegwu et al[26] | 2007 | 4 mo | M | Abdominal distension |

| 16 | Chan et al[28] | 2005 | 15 yr | F | Upper abdominal pain |

| 17 | Koh et al[29] | 2000 | 6 mo | M | Abdominal girth |

| 18 | Stavropoulos et al[20] | 1994 | 64 yr | M | Epigastric pain |

| 19 | Clerici et al[27] | 1989 | ND | F | ND |

ND: Not described.

Ultrasonographic appearances of hepatic lymphangioma are various, including non-echoic, low-echoic, and mixed-echoic masses with unicystic chamber or multichambers containing cystic and solid components (Table 2). CT scan presents as low density in whole and especially for unilocular cystic mass that reveals unenhanced imaging in the arterial phase. For multilocular mass with mixed components, enhancement is observed for septum in the arterial phase but not the cystic parts. Thus, depending on the above specific CT imaging features, the lesion may be successfully identified before the surgery[28,29]. However, our case did not follow those specific features because it enhanced quickly in arterial phase and faded away quickly in the venous phase. This resembled the features of hepatic malignancy.

Table 2.

Imaging of reviewed solitary hepatic lymphangioma

| No. | Ultrasound | CT | MRI |

| 1 | Low-echoic, unilocular cystic mass | Low density, non-enhancement | ND |

| 2 | Mixed-echoic, mass with cystic and solid components | Low density, non-enhancement | ND |

| 3 | Unilocular cystic mass | Low density, non-enhancement | ND |

| 4 | Mixed-echoic, mass with cystic and solid components | Low density, non-enhancement | Mixed signal |

| 5 | Mixed-echoic, mass with cystic and solid components | Low density, heterogeneous enhancement | ND |

| 6 | Mixed-echoic, mass with cystic and solid components | Low density, non-enhancement for cystic region, enhancement for septa | ND |

| 7 | Non-echoic, multilocular cystic mass | Low density, non-enhancement for cystic region, enhancement for septa | Enhancement for septa on T1 |

| 8 | ND | Low density, non-enhancement | ND |

| 9 | ND | Low density, non-enhancement for cystic region, enhancement for septa | Low signal on T1, high signal on T2 |

| 10 | Non-echoic, multilocular cystic mass | Heterogeneous density | Mixed signal on T2 |

| 11 | Mixed-echoic, mass with cystic and solid components | Low density, non-enhancement for cystic region, enhancement for septa | Low signal on T1, high signal on T2 |

| 12 | Unilocular cystic mass | Low density | ND |

| 13 | Multilocular cystic mass | ND | Low signal, enhancement for septa on T1 |

| 14 | Non-echoic, multilocular cystic mass | Low density, non-enhancement for cystic region, enhancement for septa | ND |

| 15 | Multilocular cystic mass | ND | ND |

| 16 | ND | Low density, non-enhancement for cystic region, enhancement for septa | ND |

| 17 | Multilocular cystic mass | Low density | ND |

| 18 | Mixed-echoic, mass with cystic and solid components | Low density | ND |

| 19 | Unilocular cystic mass | Low density | ND |

CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; ND: Not described.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of hepatic lymphangioma is low signal on T1 weighted imaging, high signal on T2 weighted imaging, and occasionally mixed signals. The specific presentation of enhanced MRI for the disease is similar to that of enhanced CT (Table 2). Usually, MRI is not the first option to be used in diagnosis of the most cases. Although enhanced CT or MRI provide the evident features, it is still difficult to make the diagnosis of hepatic lymphangioma because of no typical symptoms and signs. In addition, the bleeding within the mass adds to the difficulty of the diagnosis (Table 2). Therefore, initial diagnosis needs to be differentiated from simple cyst, cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma, hydatid cyst, sclerosing hemangioma, or hepatocellular carcinoma like our case (Table 3).

Table 3.

Initial diagnosis and surgical findings of reviewed cases

| No. | Initial diagnosis | Location | Number | Size in cm | Texture | Type of surgery |

| 1 | Hepatic cyst | Hepatoduodenal ligament | 1 | 13 × 10 | Unilocular cyst with serous fluid | LPR/CR |

| 2 | Hepatic cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma | Segments 7 and 8 | 1 | 23 × 30 | Multilocular cyst with bloody fluid | CR |

| 3 | ND | Right lobe | 1 | 14.9 × 10.7 × 9.7 | Unilocular cyst | CR |

| 4 | Rupture of a hepatic tumor | Left lobe | 1 | 12.0 × 9.5 | Multilocular cyst with blood clot | CR |

| 5 | Bile duct cyst/biliary cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma/hydatid cyst | Segment 2 | 1 | 16.2 × 13.0 × 4.3 | Multilocular cyst with serous fluid | CR |

| 6 | Hepatic hemangioma/cystadenocarcinoma | Right lobe | 1 | 23 × 15 × 7 | Multilocular cyst with brownish fluid | CR |

| 7 | Hepatic cyst | Gallbladder and hepatoduodenal ligament | 1 | 13.0 × 5.5 × 6.5 | Multilocular cyst with serous fluid | CR |

| 8 | ND | Segment 5 | 1 | 15 × 9 | Unilocular cyst | CR |

| 9 | Liver malignancy | Segment 5 | 1 | 3.0 × 2.2 × 1.5 | Multilocular cyst with mucoid fluid | CR |

| 10 | Cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma/hepatic cyst with bleeding | Segments 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 | 1 | 25 × 23 | Multilocular cyst with blood clot | CR |

| 11 | Sclerosing hemangioma/biliary cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma | Segment 4 | 1 | 3 | Multilocular cyst with mucoid fluid and solid content | CR |

| 12 | Uncertainty | Right lobe | 1 | 9.6 × 8.0 × 13.0 | Unilocular cyst with yellowish fluid | CR |

| 13 | ND | Right lobe | 1 | 12.6 × 9.4 × 11.5 | Multilocular cyst with serous fluid | CR |

| 14 | Hepatic cyst | Gallbladder | 1 | 15.2 × 9.4 | Multilocular cyst with serous fluid | CR |

| 15 | Hepatic cyst | Right lobe | 1 | ND | Multilocular cyst with serous fluid | CR |

| 16 | Hepatic lymphangioma | Segments 4 5, 6 | 1 | 21 × 20 × 6 | Multilocular cyst with brownish fluid | CR |

| 17 | Lymphangioma/mesenteric cyst | Segment 4 | 1 | 20 × 14 | Multilocular cyst | CR |

| 18 | Uncertainty | Segment 3 | 1 | 4 | Sponge-like cyst with chylous fluid and blood | CR |

| 19 | Hydatid cyst | ND | 1 | ND | Cystic | Resection |

CR: Complete resection; LPR: Laparoscopic partial resection; ND: Not described.

Biopsy of the lesion to further confirm the diagnosis of the tumor and provide information of nontumorous liver tissue is recommended for cirrhotic liver when the lesion is less than 2 cm with uncertain imaging diagnosis. Imaging diagnosis is conclusive for noncirrhotic liver and liver with uncertain cirrhosis[30]. For our case, the lesion was classified as LR-5 and diagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma with 100% certainty. However, although the patient presented with splenomegaly, diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was still difficult. Thus, according to the guidelines, a biopsy should be performed. However, a biopsy of the lesion was not carried out at that time due to the patient refusing surgery. Therefore, we needed to summarize the experience of the treatment of our case, perform a biopsy, and follow the guidelines exactly.

A final definite diagnosis of hepatic lymphangioma relied on pathological examination (Table 4). The gross specimen presented as a unilocular cyst or multilocular cysts in different sizes with septum. Some of which contained solid content and were filled with clear serous fluid, chylous fluid, and blood clots. Under the microscope, the mass, parts of which had fibrous hyperplasia constituting solid components, was constituted by a large amount of cystic-dilated lymphatic lumens lined by simple squamous endothelium and filled with acidophilic lymph. The morphology was enough to make the diagnosis for most cases[13,31]. Certainly, lymphatic marker, D2-40 (podoplanin), further confirmed the identification of the disease[1,19,32]. In addition, endothelial markers, including von Willebrand factor, CD31, and CD34 and two lymphatic markers, LYVE-1 and Prox-1, are recommended through immunohistochemistry staining when it is difficult to distinguish lymphatic vessels from blood vessels[1].

Table 4.

Histology and follow-up of reviewed solitary hepatic lymphangioma

| No. | Histology | VWF | CD-31 | CD-34 | D2-40 | LYVE-1 | Prox-1 | Discharged in d | Follow-up in mo | Prognosis |

| 1 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | - | + | ND | ND | ND | 24 | Alive/disease free |

| 2 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | 10 | 18 | Alive/disease free |

| 3 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 4 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | + | ND | + | ND | ND | 8 | 48 | Alive/disease free |

| 5 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | - | ND | ND | ND | ND | 30 | Alive/disease free |

| 6 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | + | - | ND | ND | ND | 24 | Alive/disease free |

| 7 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Alive/disease free |

| 8 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 9 | Cavernous lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 10 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 17 | Alive/disease free |

| 11 | Cystic lymphangioma | - | + | + | + | + | + | ND | 6 | Alive/disease free |

| 12 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 5 | 1 | Alive/disease free |

| 13 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 24 | Alive/disease free |

| 14 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 | ND | ND |

| 15 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 | Alive/disease free |

| 16 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 18 | Alive/disease free |

| 17 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 3 | Alive/disease free |

| 18 | Cavernous lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 7 | 24 | Alive/disease free |

| 19 | Cystic lymphangioma | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

-: Negative; +: Positive. ND: Not described; VWF: Von Willebrand factor.

Hepatic lymphangioma is usually considered a benign tumor[20,33]. Treatments for hepatic lymphangioma include complete resection, partial resection with cleaning cystic fluid, needle aspiration, sclerosing agent injection, liver transplantation, and immunosuppressive drugs for diffused and serious condition[11,12,34-36]. Partial resection with cleaning cystic fluid and needle aspiration can definitely lead to tumor recurrence[32,36]. The effectiveness of sclerosing agent injection, which is effective for a simple liver cyst, is unknown. The use of immunosuppressive agents to treat hepatic lymphangioma or lymphangiomatosis has not been approved[12,38]. Liver transplantation is the last choice for hepatic lymphangiomatosis with deteriorated liver function and progressing symptoms affecting the quality of life[11,12,34,35,37]. It is thought that hepatic lymphangioma or lymphangiomatosis is a low grade malignancy or has the potential to metastasize as hepatic recurrence is observed even after liver transplantation[12,38]. All the reviewed solitary cases including our case received complete tumor resection, and all are disease free during the follow-up periods. Thus, we suggest that complete resection be the first option when the diagnosis of hepatic lymphangioma is made.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, solitary hepatic lymphangioma is a very rare disease and the initial diagnosis may be difficult because of its atypical manifestation. Complete surgical resection is the priority to treat hepatic lymphangioma.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We greatly appreciate the patient and her family and the medical staff involved in this study.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed consent statement was obtained from the patient and her family.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), prepared and revised the manuscript according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: April 16, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Article in press: August 25, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Kreisel W, Rossi RE, Sempokuya T, Soresi M S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Xin Long, Hepatic Surgery Center, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China.

Lei Zhang, Hepatic Surgery Center, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China.

Qi Cheng, Hepatic Surgery Center, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China.

Qian Chen, Endoscopic Unit, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China.

Xiao-Ping Chen, Hepatic Surgery Center, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China. chenxpchenxp@163.com.

References

- 1.Matsumoto T, Ojima H, Akishima-Fukasawa Y, Hiraoka N, Onaya H, Shimada K, Mizuguchi Y, Sakurai S, Ishii T, Kosuge T, Kanai Y. Solitary hepatic lymphangioma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2010;40:883–889. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godart S. Embryological significance of lymphangioma. Arch Dis Child. 1966;41:204–206. doi: 10.1136/adc.41.216.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wigle JT, Oliver G. Prox1 function is required for the development of the murine lymphatic system. Cell. 1999;98:769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang YZ, Ye YS, Tian L, Li W. Rare case of a solitary huge hepatic cystic lymphangioma. World J Clin Cases. 2013;1:152–154. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i4.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noia G, Maltese PE, Zampino G, D'Errico M, Cammalleri V, Convertini P, Marceddu G, Mueller M, Guerri G, Bertelli M. Cystic Hygroma: A Preliminary Genetic Study and a Short Review from the Literature. Lymphat Res Biol. 2019;17:30–39. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2017.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saccone G, Di Meglio L, Di Meglio L, Zullo F, Locci M, Zullo F, Berghella V, Di Meglio A. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of fetal chest wall cystic lymphangioma: An Italian case series. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;236:139–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagrodia N, Defnet AM, Kandel JJ. Management of lymphatic malformations in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27:356–363. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park S, Kim SH, Youn SE, Lee ST, Kang HC. A Child With Lymphangioma Due to Somatic Mutation in PIK3CA Successfully Treated With Everolimus. Pediatr Neurol. 2019;91:65–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2018.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Losanoff JE, Richman BW, El-Sherif A, Rider KD, Jones JW. Mesenteric cystic lymphangioma. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:598–603. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nazarewski L, Patkowski W, Pacho R, Marczewska M, Krawczyk M. Gall-bladder and hepatoduodenal ligament lymphangioma - case report and literature review. Pol Przegl Chir. 2013;85:39–43. doi: 10.2478/pjs-2013-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee A, Rajanayagam J, Sarikwal A, Davies J, Lewindon P. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: liver transplantation for massive hepatic lymphangiomatosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:233. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ooi CY, Brody D, Wong R, Moroz S, Ngan BY, Navarro OM, Fecteau A, Grant D, Ng VL. Liver transplantation for massive hepatic lymphangiomatosis in a child. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:366–369. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181ec1cfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Steenbergen W, Joosten E, Marchal G, Baert A, Vanstapel MJ, Desmet V, Wijnants P, De Groote J. Hepatic lymphangiomatosis. Report of a case and review of the literature. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1968–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HH, Lee SY. Case report of solitary giant hepatic lymphangioma. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2016;20:71–74. doi: 10.14701/kjhbps.2016.20.2.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alqahtani A, Nguyen LT, Flageole H, Shaw K, Laberge JM. 25 years' experience with lymphangiomas in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1164–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90590-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chernyak V, Fowler KJ, Kamaya A, Kielar AZ, Elsayes KM, Bashir MR, Kono Y, Do RK, Mitchell DG, Singal AG, Tang A, Sirlin CB. Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LI-RADS) Version 2018: Imaging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in At-Risk Patients. Radiology. 2018;289:816–830. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018181494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peña Ros E, Candel Aremas MF, Pastor Pérez P, Albarracín Marín-Blázquez A. [Cystic hepatic lymphangioma: a rare cause of abdominal pain in the adult] Cir Esp. 2013;91:e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ak SJ, Park SK, Park HU. [A case of isolated hepatic lymphangioma] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;59:189–192. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2012.59.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakano T, Hara Y, Shirokawa M, Shioiri S, Goto H, Yasuno M, Tanaka M. Hemorrhagic giant cystic lymphangioma of the liver in an adult female. J Surg Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjv033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stavropoulos M, Vagianos C, Scopa CD, Dragotis C, Androulakis J. Solitary hepatic lymphangioma. A rare benign tumour: a case report. HPB Surg. 1994;8:33–36. doi: 10.1155/1994/63638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zouari M, Ben Dhaou M. Solitary hepatic lymphangioma in an 8-month-old child. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:440. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.440.6111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Q, Sui CJ, Li BS, Gao A, Lu JY, Yang JM. Solitary hepatic lymphangioma: a one-case report. Springerplus. 2014;3:314. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang L, Li J, Zhou F, Yan J, Liu C, Zhou AY, Tang A, Yan Y. Giant cystic lymphangioma of the liver. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:784–787. doi: 10.1007/s12072-010-9220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shahi KS, Geeta B, Rajput P. Solitary hepatic lymphangioma in a 22-day-old infant. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:E9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeidan S, Delarue A. Uncommon etiology of a cystic hepatic tumor. Dig Surg. 2008;25:10–11. doi: 10.1159/000114195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nzegwu MA, Ekenze SO, Okafor OC, Anyanwu PA, Odetunde OA, Olusina DB. Solitary hepatic lymphangioma in an infant. J Perinat Med. 2007;35:164–165. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2007.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clerici D, Griffa B, Ceppi M, Basilico V, Milvio E. [Cystic lymphangioma of the liver. Presentation of a clinical case] Minerva Chir. 1989;44:1139–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan SC, Huang SF, Lee WC, Wan YL. Solitary hepatic lymphangioma--a case report. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2005:100–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koh CC, Sheu JC. Hepatic lymphangioma--a case report. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16:515–516. doi: 10.1007/s003839900327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roisman I, Manny J, Fields S, Shiloni E. Intra-abdominal lymphangioma. Br J Surg. 1989;76:485–489. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kohashi T, Itamoto T, Matsugu Y, Nishisaka T, Nakahara H. An adult case of lymphangioma of the hepatoduodenal ligament mimicking a hepatic cyst. Surg Case Rep. 2017;3:2. doi: 10.1186/s40792-016-0280-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kochin IN, Miloh TA, Arnon R, Iyer KR, Suchy FJ, Kerkar N. Benign liver masses and lesions in children: 53 cases over 12 years. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13:542–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Datz C, Graziadei IW, Dietze O, Jaschke W, Königsrainer A, Sandhofer F, Margreiter R. Massive progression of diffuse hepatic lymphangiomatosis after liver resection and rapid deterioration after liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1278–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller C, Mazzaferro V, Makowka L, ChapChap P, Demetris J, Tzakis A, Esquivel CO, Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. Orthotopic liver transplantation for massive hepatic lymphangiomatosis. Surgery. 1988;103:490–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stunell H, Ridgway PF, Torreggiani WC, Crotty P, Conlon KC. Hepatic lymphangioma: a rare cause of abdominal pain in a 30-year-old female. Ir J Med Sci. 2009;178:93–96. doi: 10.1007/s11845-007-0094-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ra SH, Bradley RF, Fishbein MC, Busuttil RW, Lu DS, Lassman CR. Recurrent hepatic lymphangiomatosis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1593–1597. doi: 10.1002/lt.21306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiménez-Rivera C, Avitzur Y, Fecteau AH, Jones N, Grant D, Ng VL. Sirolimus for pediatric liver transplant recipients with post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease and hepatoblastoma. Pediatr Transplant. 2004;8:243–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2004.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]