Abstract

Background

This study aimed to evaluate the clinicopathological factors associated with surgical site infection (SSI) and the prognostic impact on patients after colorectal cancer (CRC) resection surgery.

Material/Methods

This retrospective study evaluated the relationships between SSI and various clinicopathological factors and prognostic outcomes in 326 consecutive patients with CRC who underwent radical resection surgery at Wuhan Union Hospital during April 2015–May 2017.

Results

Among the 326 patients who underwent radical CRC resection surgery, 65 had SSIs, and the incidence rates of incisional and organ/space SSI were 16.0% and 12.9%, respectively. Open surgery, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and a previous abdominal surgical history were identified as risk factors for incisional SSI. During a median follow-up of 40 months (range: 5–62 months), neither simple incisional nor simple organ/space SSI alone significantly affected disease-free survival (DFS) or overall survival (OS), whereas combined incisional and organ/space SSI had a significant negative impact on both the 3-year DFS and OS (P<0.001). A multivariate analysis identified that age ≥60 years, lymph node involvement, tumor depth (T3–T4), and incisional and organ/space SSI were independent predictors of 3-year DFS and OS. In addition, adjuvant chemotherapy and a carbohydrate antigen-125 concentration ≥37 ng/ml were also independent predictors of OS.

Conclusions

We have identified several clinicopathological factors associated with SSI, and identified incisional and organ/space SSI is an independent prognostic factor after CRC resection. Assessing the SSI classification may help to predict the prognosis of these patients and determine further treatment options.

MeSH Keywords: Colorectal Neoplasms, Postoperative Complications, Prognosis, Risk Factors

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common gastrointestinal cancers worldwide [1,2]. Although the prognosis of patients with CRC has improved dramatically because of radical resection and the increasing application of adjuvant chemotherapy [3–5], this tumor type remains the second most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. Therefore, it is essential to identify novel prognostic factors for CRC.

Surgical site infection (SSI), which is defined as an infection of the surgical site within 30 days after surgery or within 1 year after prosthesis implantation, has been reported as the most common nosocomial infection affecting surgical patients [6,7]. According to the National Nosocomial Infectious Surveillance (NNIS) System maintained by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), SSI can be sub-classified as incisional or organ/space SSI [6]. The reported incidence of SSI after colorectal surgery ranges from 3% to 30% [8–10], and this high incidence is attributed to the complexity of colorectal surgery and the risk of surgical site contamination by the contents of the large intestine [11]. Regarding outcomes, SSI has been associated with extended postoperative hospital stay, as well as increased costs, morbidity, and mortality [12,13].

SSI after CRC surgery has become an important field of clinical research. To date, most studies on this topic have focused on the risk factors of SSI [14–20], and few have addressed the prognostic role of postoperative SSI in patients with CRC. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the clinicopathological factors associated with SSI in a series of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients and to determine the postoperative prognostic impact of this condition.

Material and Methods

Selected patients and study design

This retrospective study included 326 patients who underwent radical surgery for CRC at the Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology in China between April 2015 and May 2017. We retrospectively collected the demographic, clinicopathological, and survival data of selected patients. SSI was diagnosed according to the definition provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1992 [6]. The category of “incisional SSI” included both superficial incisional SSI and deep-incision SSI, while “organ/space SSI” was defined as the formation of an abdominal abscess.

Patients with the following conditions were excluded from the study: (1) patients who did not undergo radical resection, (2) patients without primary incision closure, (3) patients with Stage 0 CRC according to the TNM classification, and (4) patients with distant metastases (TNM Stage 4). This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No. 2018-S377), and carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Surgical procedure

For preoperative preparation, all patients received an intestinal preparation 1 day before surgery and prophylactic antibiotics 1 h before surgery. All operations were performed by professional colorectal surgeons. The choice of surgical procedure depended mainly on the patient’s requirements and the surgeon’s experience, although the tumor size, local invasion, and previous abdominal surgery history also influenced this decision. Usually, the incision was made in the linear alba or through the right rectus and was protected by an incisional protective sleeve. The laparoscopic surgical procedure typically involved 3 to 5 ports used to mobilize the colorectal tissue and ligature the major blood vessels. The specimen was removed through a 5–8 cm auxiliary incision. Finally, intestinal anastomosis was achieved using the double-stapler method.

Data collection

We recorded data on patient age; sex; body mass index (BMI); American Society of Anesthesiologist risk (ASA) score; tumor location, size, differentiation, and depth; perineural and vascular invasion; hospitalization and discharge dates; SSI occurrence and treatment; blood transfusion data; surgical method; operation time; lymph node involvement; anastomotic leakage; adjuvant chemotherapy; preoperative obstruction; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic heart disease, and diabetes status; and the preoperative serum albumin, hemoglobin, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), and CA199 concentrations. The primary study endpoints were disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) at 3 years.

Postoperative follow-up

Postoperatively, the patients were assessed daily by surgeons until discharge. Thirty days after radical CRC resection, all patients were contacted via telephone to enquire about the symptoms of SSI. Additionally, all patients participated in a follow-up survey every 3–6 months during the first 3 years of outpatient visits. During this 3-year period, the patients were assessed using physical and laboratory tests, including measurements of the neutrophil percentage and tumor biomarkers (CEA, CA125, and CA-199) at each visit, computed tomography (CT) scans of the pelvis, abdomen, and chest every 6 months, and a complete colonoscopy each year. After the first 3 years, the patients participated in follow-up surveys every 6–12 months via outpatient visits or the telephone until death due to CRC recurrence and/or metastasis or the study endpoint (June 30, 2020). The median follow-up period was 40 months (range, 5–62 months).

Statistical analysis

The relationships between SSI and other clinicopathological parameters were calculated using the chi-square test or t test. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (percentages), while continuous variables are expressed as means±standard deviations. Factors identified as significant for SSI in a univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate logistic regression analysis. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the 3-year DFS and OS, and the statistical significance of inter-group differences in these outcomes were determined using the log-rank test. Another multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis was performed to examine the independent prognostic factors and risk factors for recurrence. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Basic patient characteristics

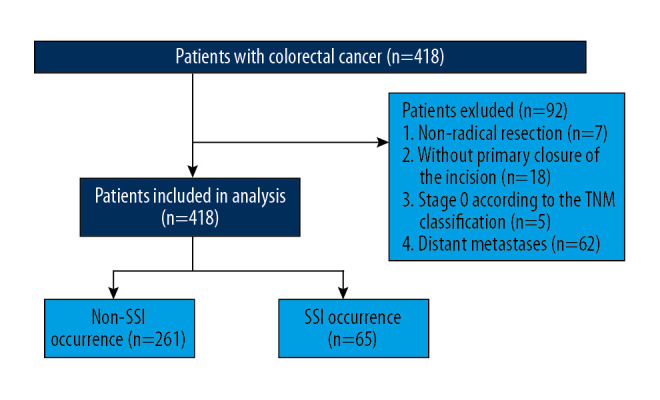

Among the 326 CRC patients included in our study during the indicated period (Figure 1), 65 patients (19.9%) met the criteria of SSI and 261 patients (80.1%) did not develop SSI. The median ages of the SSI and non-SSI groups were 61.0 (41–84) and 57.8 (22–84) years, respectively. There were no significant inter-group differences in age, sex, BMI, tumor size, tumor location, operation time, ASA score, preoperative obstruction, preoperative serum albumin and hemoglobin concentrations, differentiation, T stage, lymph node involvement, and adjuvant chemotherapy use (P>0.05; Table 1). However, the median postoperative hospital stay length was significantly longer in the SSI group than in the non-SSI group (12.5 vs. 25.3 days, P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Strategies for selecting patients to be included in the study.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients.

| Variables | SSI(−) (N=261) n (%)/mean±sd |

SSI(+) (N=65) n (%)/mean±sd |

Statistic | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.144* | 0.704 | ||

| Male | 162 (62.1) | 42 (64.6) | ||

| Female | 99 (37.9) | 23 (35.4) | ||

| Age (y) | 57.85±11.749 | 61.06±11.511 | 1.920** | 0.056 |

| BMI ≥25 kg/m2 | 0.104* | 0.747 | ||

| Yes | 57 (21.8) | 52 (80.0) | ||

| No | 204 (78.2) | 13 (20.0) | ||

| Preoperative CEA (ng/ml) | 7.86±17.156 | 9.715±14.53 | 0.800** | 0.424 |

| Preoperative CA125 (ng/ml) | 16.00±18.959 | 21.758±29.248 | 1.509** | 0.135 |

| Preoperative CA199 (ng/ml) | 33.57±122.680 | 63.92±176.309 | 1.311** | 0.194 |

| Preoperative Serum albumin (g/L) | 40.08±4.576 | 40.07±4.564 | 0.007** | 0.995 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin (g/L) | 118.28±22.021 | 120.23±22.632 | 0.637** | 0.525 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 4.43±2.026 | 4.44±1.704 | 0.057** | 0.955 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 3.239* | 0.072 | ||

| Yes | 20 (7.7) | 1 (1.5) | ||

| No | 241 (92.3) | 64 (98.5) | ||

| Operation time (hour) | 3.57±1.112 | 3.72±1.045 | 0.998** | 0.319 |

| Postoperative hospitalization dates | 12.53±3.636 | 25.35±17.044 | 6.031** | <0.001 |

| Blood transfusion | 0.650* | 0.420 | ||

| Yes | 75 (28.7) | 22 (33.8) | ||

| No | 186 (71.3) | 43 (66.2) | ||

| Anastomotic leakage | 135.364* | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 3 (1.1) | 34 (52.3) | ||

| No | 258 (98.9) | 31 (47.7) | ||

| Preoperative obstruction | 0.011* | 0.916 | ||

| Yes | 74 (28.4) | 18 (27.7) | ||

| No | 187 (71.6) | 47 (72.3) | ||

| Lymph node involvement | 0.568* | 0.451 | ||

| Yes | 122 (46.7) | 27 (41.5) | ||

| No | 139 (53.3) | 38 (58.5) | ||

| ASA score | 0.537* | 0.911 | ||

| I | 7 (2.7) | 2 (3.1) | ||

| II | 171 (65.5) | 41 (63.1) | ||

| III | 62 (23.8) | 15 (23.1) | ||

| IV | 21 (8.0) | 7 (10.8) | ||

| Tumor location | 0.659* | 0.417 | ||

| Colon | 142 (54.4) | 39 (60.0) | ||

| Rectum | 119 (45.6) | 26 (40.0) | ||

| Operative approach | 3.048* | 0.081 | ||

| Open | 90 (34.5) | 30 (46.2) | ||

| Laparoscopic | 171 (65.5) | 35 (53.8) | ||

| Differentiation | 2.506* | 0.113 | ||

| Well | 235 (90.0) | 54 (83.1) | ||

| Poor | 26 (10.0) | 11 (16.9) | ||

| T stage | 4.481* | 0.214 | ||

| I | 16 (6.1) | 3 (4.6) | ||

| II | 28 (10.7) | 13 (20.0) | ||

| III | 193 (73.9) | 45 (69.2) | ||

| IV | 24 (9.2) | 4 (6.2) |

ASA score – American Society of Anesthesiologists score; sd – standaed deviation. SSI – surgical site infection; BMI – body mass index.

Chi-square test;

t-test.

Relationship between SSI and clinicopathological factors in patients with colorectal cancer

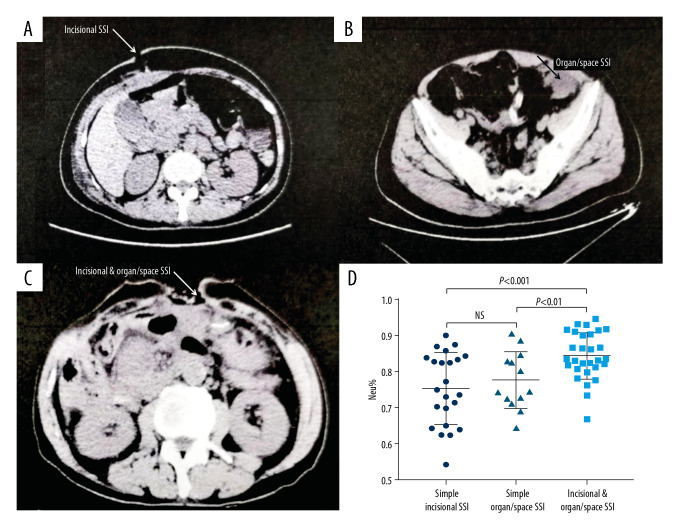

Representative CT images from patients in the simple incisional SSI, simple organ/space SSI, and incisional and organ/space SSI groups are shown in Figure 2. No abscesses were detected in patients with simple incisional SSI (Figure 2A), and no wound infections were detected in patients with simple organ/space SSI (Figure 2B). In contrast, CT revealed wound dehiscence and abscesses in patients with both incisional and organ/space SSI (Figure 2C). Figure 2D demonstrates the percentages of serum neutrophils in the 3 groups at the time of SSI diagnosis. Patients with incisional and organ/space SSI were found to have a significantly higher percentage of neutrophils than those in the simple incisional SSI and organ/space SSI groups (P<0.01 and P<0.001, respectively).

Figure 2.

Representative CT images and serum neutrophils percentage assessment in the 3 groups at the time of SSI diagnosis. (A) CT scanning of simple incisional SSI; (B) CT scanning of simple organ/space incisional SSI; (C) CT scanning of incisional and organ/space SSI; (D) The percentages of serum neutrophils in the 3 groups at the time of SSI diagnosis.

The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 2. The univariate analysis showed that neither incisional nor organ/space SSI was associated with sex, BMI, age, diabetes, tumor size, lymph node involvement, ASA score, operation time, preoperative serum albumin, preoperative hemoglobin, blood transfusion, tumor differentiation, vascular invasion, and perineural invasion (Table 2). Incisional SSI was significantly related to clinical factors such as COPD (P=0.007), an abdominal surgical history (P=0.026), and the operative approach (open vs. laparoscopic, P=0.031). The multivariate analysis confirmed that COPD (odds ratio [OR]=3.404, P=0.007) and an abdominal surgical history (OR=2.185, P=0.023) were independent risk factors for incisional SSI (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of risk factors for surgical site infection (SSI).

| Variables | Incisional SSI (N=52) | P value | Organ/space SSI (N=42) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.427 | 0.353 | ||

| Male (n=204) | 14.7% | 14.2% | ||

| Female | 18.0% | 10.7% | ||

| Age (y) | 0.152 | 0.467 | ||

| ≥60 (n=146) | 19.2% | 14.4% | ||

| <60 | 13.3% | 11.7% | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.207 | 0.189 | ||

| Yes (n=29) | 24.1% | 20.7% | ||

| No | 15.2% | 12.1% | ||

| COPD | 0.007 | 0.314 | ||

| Yes (n=26) | 34.6% | 19.2% | ||

| No | 14.3% | 12.3% | ||

| Tumor location | 0.062 | 0.915 | ||

| Colon (n=181) | 19.3% | 12.7% | ||

| Rectum | 11.7% | 13.1% | ||

| Tumor size | 0.684 | 0.409 | ||

| ≥5 cm (n=121) | 14.9% | 14.9% | ||

| <5 cm | 16.6% | 11.7% | ||

| Lymph node involvement | 0.401 | 0.790 | ||

| Yes (n=149) | 14.1% | 13.4% | ||

| No | 17.5% | 12.4% | ||

| Depth of tumor | 0.084 | 0.244 | ||

| T1, T2(n=60) | 14.3% | 13.9% | ||

| T3, T4 | 23.3% | 8.3% | ||

| ASA score | 0.466 | 0.382 | ||

| I–II (n=221) | 14.9% | 11.8% | ||

| III–IV | 18.1% | 15.2% | ||

| Blood transfusion | 0.134 | 0.205 | ||

| Yes (n=97) | 20.6% | 16.5% | ||

| No | 14.0% | 11.4% | ||

| Operative approach | 0.031 | 0.120 | ||

| Open (n=121) | 21.7% | 16.7% | ||

| Laparoscopic | 12.6% | 10.7% | ||

| Abdominal surgical history | 0.026 | 0.208 | ||

| Yes (n=69) | 24.6% | 17.4% | ||

| No | 13.6% | 11.7% | ||

| Vascular invasion | 0.492 | 0.362 | ||

| Yes (n=68) | 13.2% | 16.2% | ||

| No | 16.7% | 12.0% | ||

| Perineural invasion | 0.083 | 0.854 | ||

| Yes (n=74) | 9.5% | 13.5% | ||

| No | 17.9% | 12.7% | ||

| BMI | 0.668 | 0.693 | ||

| ≥25 kg/m2 (n=70) | 14.3% | 14.3% | ||

| <25 kg/m2 | 16.4% | 12.5% | ||

| Differentiation | 0.181 | 0.129 | ||

| Yes (n=293) | 9.2% | 14.7% | ||

| No | 16.2% | 24.3% | ||

| Preoperative obstruction | 0.574 | 0.673 | ||

| Yes (n=92) | 14.1% | 14.1% | ||

| No | 16.7% | 12.4% |

SSI – surgical site infection; ASA score – American Society of Anesthesiologists score; BMI – body mass index; COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Variables | Incisional SSI | Organ/space SSI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P value | Yes | No | P value | |

| Preoperative serum albumin (g/L) | 39.55 | 40.17 | 0.364 | 40.48 | 40.01 | 0.542 |

| Operation time (hours) | 3.78 | 3.57 | 0.204 | 3.76 | 3.58 | 0.311 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin (g/L) | 116 | 119.17 | 0.344 | 121.64 | 118.23 | 0.351 |

SSI – surgical site infection.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for incisional surgical site infection (SSI).

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| COPD | 3.404 (1.388–8.348) | 0.007 |

| Abdominal surgical history | 2.185 (1.114–4.286) | 0.023 |

| Operative approach (Lap) | 0.566 (0.307–1.043) | 0.068 |

OR – odds ratio; CI – confidence interval. COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Lap – paparoscopic.

Predictive value of SSIs for DFS and OS

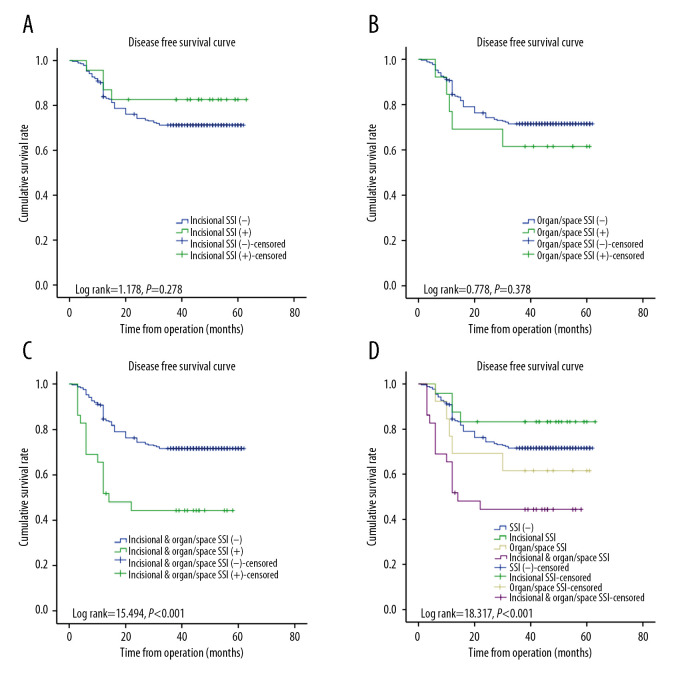

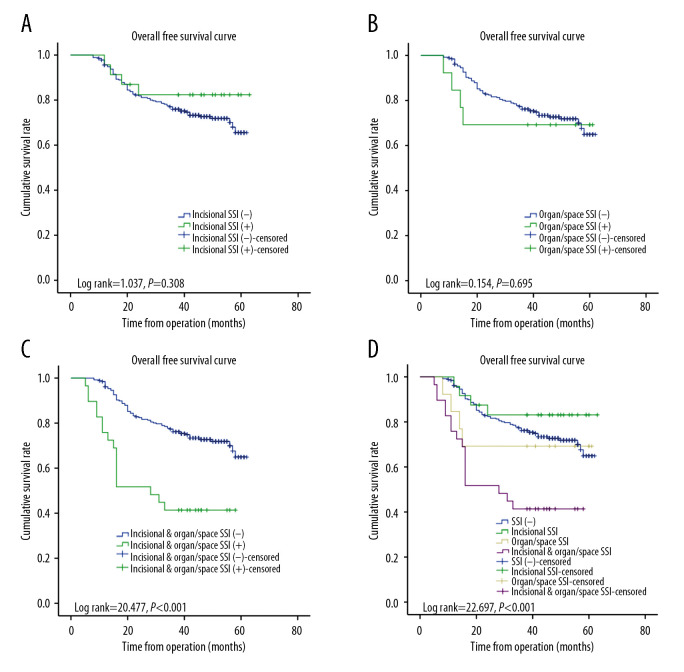

We divided the patients into 3 different subgroups according to the infection status: simple incisional SSI (Figure 3A), simple organ/space SSI (Figure 3B), and incisional and organ/space SSI (Figure 3C). Kaplan-Meier survival analyses revealed that patients with combined incisional and organ/space SSI had a significantly shorter DFS than those without any SSI (P<0.001; Figure 3C, 3D), whereas neither simple incisional SSI nor simple organ/space SSI had a significant effect on the 3-year DFS (P=0.278 and P=0.378, respectively; Figure 3A, 3B). We also determined that incisional and organ/space SSI had a significant negative impact on OS (P<0.001; Figure 4C, 4D), whereas simple incisional SSI or simple organ/space SSI had no statistically significant effect on OS (Figure 4A, 4B, P=0.308 and P=0.695, respectively).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of disease-free survival (DFS) according to SSI in patients with CRC. (A) DFS of patients with simple incisional SSI (P=0.278); (B) DFS of patients with simple organ/space SSI (P=0.378); (C) DFS of patients with incisional and organ/space SSI (P<0.001); (D) Patients with incisional and organ/space SSI had a significantly poorer 3-year DFS than those without any SSI, whereas neither simple incisional SSI nor simple organ/space SSI had a significant effect on DFS.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS) according to SSI in patients with CRC. (A) OS of patients with simple incisional SSI (P=0.308); (B) OS of patients with simple organ/space SSI (P=0.695); (C) OS of patients with incisional and organ/space SSI (P<0.001); (D) Compared with simple incisional SSI and simple organ/space SSI, only incisional and organ/space SSI had a significant negative effect on OS.

Prognostic factors in CRC patients

A univariate analysis identified incisional and organ/space SSI (P<0.001), age ≥60 years (P=0.018), tumor differentiation (P=0.033), lymph node involvement (P<0.001), tumor depth (T3–T4; P<0.001), operative approach (P=0.003), anastomotic leakage (P=0.026), vascular invasion (P=0.027), perineural invasion (P=0.003), preoperative CEA ≥5 ng/ml (P=0.029), preoperative CA125 ≥37 ng/ml (P=0.003), and preoperative CA199 ≥37 ng/ml (P=0.027) as factors associated significantly with recurrence. In a multivariate analysis, age ≥60 years (hazard ratio [HR]=1.880, P=0.005), lymph node involvement (HR=2.968, P<0.001), tumor depth (T3–T4; HR=3.789, P=0.027), and incisional & organ/space SSI (HR=4.000, P=0.007) were independent risk factors for recurrence. Incisional and organ/space SSI was confirmed to have a negative prognostic impact on the 3-year DFS outcomes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prognostic analysis on 3-year DFS in patients with colorectal cancer.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Incisional SSI | 0.581 (0.213–1.588) | 0.290 | |||

| Organ/space SSI | 1.492 (0.603–3.693) | 0.387 | |||

| Incisional+organ/space SSI | 2.794 (1.624–4.806) | <0.001 | 4.000 (1.459–10.964) | 0.007 | |

| Sex | F | Ref. | |||

| M | 1.006 (0.669–1.514) | 0.977 | |||

| Age ≥60 (year) | 1.596 (1.073–2.376) | 0.021 | 1.880 (1.207–2.929) | 0.005 | |

| Tumor location | Colon | Ref. | |||

| Rectum | 0.786 (0.524–1.177) | 0.242 | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | <5 | Ref. | |||

| ≥5 | 1.297 (0.869–1.935) | 0.203 | |||

| Tumor differentiation | poor | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| high | 0.568 (0.332–0.971) | 0.039 | 0.932 (0.506–1.718) | 0.823 | |

| Lymph node involvement | 3.280 (2.141–5.025) | <0.001 | 2.968 (1.818–4.847) | <0.001 | |

| Depth of tumor | T1–T2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| T3–T4 | 4.796 (1.950–11.796) | <0.001 | 3.789 (1.166–12.307) | 0.027 | |

| Operative approach | open | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Lap | 0.553 (0.372–0.823) | 0.003 | 0.693 (0.447–1.074) | 0.101 | |

| Anastomotic leakage | 1.839 (1.076–3.144) | 0.026 | 0.557 (0.178–1.743) | 0.315 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.796 (0.535–1.183) | 0.259 | |||

| Preoperative obstruction | 1.277 (0.837–1.948) | 0.256 | |||

| Vascular invasion | 1.631 (1.047–2.541) | 0.031 | 0.817 (0.482–1.386) | 0.454 | |

| Perineural invasion | 1.860 (1.219–2.838) | 0.004 | 1.372 (0.858–2.192) | 0.186 | |

| Blood transfusion | 1.493 (0.990–2.252) | 0.056 | |||

| Preoperative CEA (ng/ml) | <5 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| ≥5 | 1.545 (1.037–2.304) | 0.033 | 1.079 (0.684–1.701) | 0.774 | |

| Preoperative CA125 (ng/ml) | <35 | Ref. | |||

| ≥35 | 2.271 (1.289–4.003) | 0.005 | 1.660 (0.873–3.159) | 0.122 | |

| Preoperative CA199 (ng/ml) | <37 | Ref. | |||

| ≥37 | 1.733 (1.050–2.861) | 0.031 | 1.088 (0.622–1.901) | 0.768 | |

HR – hazard ratio; CI – confidence interval; SSI – surgical site infection; F – Female; M – Male; Lap – laparoscopic.

Another univariate analysis identified incisional and organ/space SSI (P<0.001), age ≥60 years (P=0.001), lymph node involvement (P<0.001), tumor depth (T3–T4; P=0.001), anastomotic leakage (P=0.016), operative approach (P=0.002), adjuvant chemotherapy (P=0.025), vascular invasion (P=0.011), perineural invasion (P=0.001), preoperative CEA ≥5 ng/ml (P=0.009), preoperative CA125 ≥37 ng/ml (P<0.001), and preoperative CA199 ≥37 ng/ml (P=0.005) as factors associated with the postoperative prognosis. A subsequent multivariate Cox regression analysis of these factors identified age ≥60 years (HR=1.941, P=0.007), lymph node involvement (HR=2.632, P<0.001), tumor depth (T3–T4; HR=2.961, P=0.041), incisional and organ/space SSI (HR=3.694, P=0.011), adjuvant chemotherapy (HR=0.598, P=0.025), and CA125 ≥37 ng/ml (HR=1.892, P=0.041) as independent prognostic factors for OS. Incisional and organ/space SSI was confirmed to have a negative prognostic impact on the patients’ OS outcomes (Table 5).

Table 5.

Prognostic analysis on OS in patients with colorectal cancer.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Incisional SSI | 0.598 (0.219–1.635) | 0.316 | |||

| Organ/space SSI | 1.222 (0.446–3.351) | 0.696 | |||

| Incisional+organ/space SSI | 3.164 (1.862–5.377) | <0.001 | 3.694 (1.346–10.138) | 0.011 | |

| Sex | F | Ref. | |||

| M | 1.081 (0.719–1.626) | 0.708 | |||

| Age ≥60 (year) | 2.026 (1.352–3.036) | 0.001 | 1.941 (1.197–3.147) | 0.007 | |

| Tumor location | Colon | Ref. | |||

| Rectum | 0.841 (0.561–1.260) | 0.402 | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | <5 | Ref. | |||

| ≥5 | 1.274 (0.850–1.910) | 0.242 | |||

| Tumor differentiation | poor | Ref. | |||

| high | 0.637 (0.367–1.105) | 0.109 | |||

| Lymph node involvement | 2.935 (1.921–4.484) | <0.001 | 2.632 (1.625–4.262) | <0.001 | |

| Depth of tumor | T1–T2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| T3–T4 | 3.947 (1.727–9.021) | 0.001 | 2.961 (1.043–8.405) | 0.041 | |

| Operative approach | open | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Lap | 0.537 (0.361–0.800) | 0.002 | 0.681 (0.439–1.057) | 0.087 | |

| Anastomotic leakage | 1.937 (1.133–3.312) | 0.016 | 0.662 (0.213–2.055) | 0.475 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.634 (0.426–0.945) | 0.025 | 0.598 (0.372–0.964) | 0.035 | |

| Preoperative obstruction | 1.184 (0.770–1.821) | 0.442 | |||

| Vascular invasion | 1.780 (1.140–2.781) | 0.011 | 0.943 (0.547–1.625) | 0.832 | |

| Perineural invasion | 2.032 (1.326–3.112) | 0.001 | 1.510 (0.936–2.434) | 0.091 | |

| Blood transfusion | 1.306 (0.858–1.987) | 0.213 | |||

| Preoperative CEA (ng/ml) | <5 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| ≥5 | 1.711 (1.147–2.553) | 0.009 | 1.129 (0.716–2.553) | 0.603 | |

| Preoperative CA125 (ng/ml) | <35 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| ≥35 | 3.106 (1.811–5.326) | <0.001 | 1.892 (1.027–3.485) | 0.041 | |

| Preoperative CA199 (ng/ml) | <37 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| ≥37 | 2.001 (1.234–3.246) | 0.005 | 1.381 (0.803–2.377) | 0.243 | |

SSI –surgical site infection; HR – hazard ratio; CI – confidence interval; F – Female; M – Male; Lap – laparoscopic.

Discussion

We determined an overall occurrence of SSI after CRC resection of 19.9% (65/326), as well as incidence rates of incisional SSI and organ/space SSI of 16.0% (52/326) and 12.9% (42/326), respectively. The combination of incisional and organ/space SSI was shown to predict a poor 3-year DFS after CRC resection (P<0.001), whereas neither incisional SSI nor organ/space SSI alone had a significant effect on the 3-year DFS (P=0.278 and P=0.378, respectively). Incisional and organ/space SSI was also confirmed as a prognostic factor for OS after colorectal cancer surgery (P<0.001) and as an independent prognostic factor for both DFS and OS (P=0.007 and P=0.011, respectively). We also identified several clinicopathologic factors as risk factors for incisional SSI.

CRC surgery is associated with a high incidence of SSI because of the significant bacterial load in the associated organ/space [11]. Additionally, age, diabetes, ASA score, COPD, obesity, open surgery, and anastomotic leakage have been reported as risk factors for SSI [14–20]. Consistent with those earlier findings, we identified COPD and open surgery as important risk factors for SSI. Interestingly, we also identified abdominal surgical history (P=0.028) as a risk factor for SSI. When treating a patient with a history of abdominal surgery, some surgeons might choose open surgery over laparoscopic surgery because of intraperitoneal adhesions, while others might begin with laparoscopic surgery but later convert to laparotomy. In an open surgery, continuous mechanical retraction of the abdominal wall and surgical incision adversely affect the blood supply to the incision and affect postoperative wound healing and increase the risk of SSI [20]. At our institution, some surgeons preferred to perform laparotomy through the original surgical incision, which might also have disrupted postoperative wound healing by reducing the blood supply in the scar.

Few studies have reported the prognostic role of SSI in patients with CRC. In this study, we found that neither simple incisional SSI nor organ/space SSI alone affected the prognosis of patients with CRC. In contrast, the combination of organ/space SSI and incisional SSI led to a poor prognosis in terms of both DFS and OS (P<0.001). The mechanisms underlying this association between incisional and organ/space SSI and an unfavorable prognosis remain unclear. However, combined incisional and organ/space SSI might indicate a more serious abdominal infection, as many incision infections are caused by an outward extension of an intraperitoneal infection. In our study, we found that incisional and organ/space SSIs were more serious than either incisional SSI or organ/space SSI alone (Figure 2D). Moreover, postoperative peritoneal and pelvic infections were shown to favor the proliferation, invasion, and migration capacities of cancer cells [21]. Bohle et al. also demonstrated that a postoperative intra-abdominal infection led to increased angiogenesis and tumor recurrence in vivo [22]. Several studies determined that peritoneal infection increased the concentrations of serum C-reactive protein (CRP), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which are closely associated with poor OS and cancer-specific survival [23,24]. Moreover, a serious SSI can delay or even prevent adjuvant chemotherapy [25]. All these factors may explain the poor prognosis of patients with CRC who develop incisional and organ/space SSI.

Our study had several limitations. First, our sample size was small, and this may have weakened the statistical power. Second, the design was retrospective, which is associated with inherent limitations. Third, the follow-up duration in this cohort was short. A longer follow-up duration would be needed to fully determine the role of SSI as a predictor of the longer-term prognosis (e.g., 5-year DFS) of patients with CRC.

Conclusions

In conclusion, combined incisional and organ/space SSI was shown to play a significant prognostic role in patients who underwent CRC resection. The combination of incisional and organ/space SSI may indicate a more serious infection than a simple incisional or organ/space SSI alone. Therefore, the combined SSI may be a clinically applicable marker and potential tool with which to identify a CRC patient with a poor prognosis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of support: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81902703 and 81874184)

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapiteijn E, Putter H, van de Velde CJ Cooperative investigators of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. Impact of the introduction and training of total mesorectal excision on recurrence and survival in rectal cancer in The Netherlands. Br J Surg. 2002;89(9):1142–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wibe A, Møller B, Norstein J, et al. A national strategic change in treatment policy for rectal cancer – implementation of total mesorectal excision as routine treatment in Norway. A national audit. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(7):857–66. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hohenberger W, Weber K, Matzel K, et al. Standardized surgery for colonic cancer: Complete mesocolic excision and central ligation – technical notes and outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11(4):354–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01735.x. discussion 364–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, et al. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: A modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13(10):606–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss CA, 3rd, Statz CL, Dahms RA, et al. Six years of surgical wound infection surveillance at a tertiary care center: Review of the microbiologic and epidemiological aspects of 20,007 wounds. Arch Surg. 1999;134(10):1041–48. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.10.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32(8):470–85. doi: 10.1016/S0196655304005425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang R, Chen HH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection after elective resection of the colon and rectum: A single-center prospective study of 2,809 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2001;234(2):181–89. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ju MH, Ko CY, Hall BL, et al. A comparison of 2 surgical site infection monitoring systems. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):51–57. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Limón E, Shaw E, Badia JM, et al. Post-discharge surgical site infections after uncomplicated elective colorectal surgery: Impact and risk factors. The experience of the VINCat Program. J Hosp Infect. 2014;86(2):127–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson DJ, Podgorny K, Berríos-Torres SI, et al. Strategies to prevent surgical site infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(6):605–27. doi: 10.1086/676022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malone DL, Genuit T, Tracy JK, et al. Surgical site infections: reanalysis of risk factors. J Surg Res. 2002;103(1):89–95. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S, Wang M, Lu X, et al. Abdomen depth and rectus abdominis thickness predict surgical site infection in patients receiving elective radical resections of colon cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:637. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kvasnovsky CL, Adams K, Sideris M, et al. Elderly patients have more infectious complications following laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(1):94–100. doi: 10.1111/codi.13109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poon JT, Law WL, Wong IW, et al. Impact of laparoscopic colorectal resection on surgical site infection. Ann Surg. 2009;249(1):77–81. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819279e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yaegashi M, Otsuka K, Kimura T, et al. Transumbilical abdominal incision for laparoscopic colorectal surgery does not increase the risk of postoperative surgical site infection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(5):715–22. doi: 10.1007/s00384-017-2753-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishawi M, Fakhoury M, Denoya PI, et al. Surgical site infection rates: Open versus hand-assisted colorectal resections. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18(4):381–86. doi: 10.1007/s10151-013-1066-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamboj M, Childers T, Sugalski J, et al. Risk of surgical site infection (SSI) following colorectal resection is higher in patients with disseminated cancer: An NCCN member cohort study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(5):555–62. doi: 10.1017/ice.2018.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itatsu K, Sugawara G, Kaneoka Y, et al. Risk factors for incisional surgical site infections in elective surgery for colorectal cancer: Focus on intraoperative meticulous wound management. Surg Today. 2014;44(7):1242–52. doi: 10.1007/s00595-013-0677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salvans S, Mayol X, Alonso S, et al. Postoperative peritoneal infection enhances migration and invasion capacities of tumor cells in vitro: An insight into the association between anastomotic leak and recurrence after surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2014;260(5):939–43. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000958. discussion 943–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohle B, Pera M, Pascual M, et al. Postoperative intra-abdominal infection increases angiogenesis and tumor recurrence after surgical excision of colon cancer in mice. Surgery. 2010;147(1):120–26. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen HJ, Christensen IJ, Sørensen S, et al. Preoperative plasma plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 and serum C-reactive protein levels in patients with colorectal cancer. The RANX05 Colorectal Cancer Study Group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7(8):617–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02725342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cascinu S, Staccioli MP, Gasparini G, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor can predict event-free survival in stage II colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(7):2803–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Des Guetz G, Nicolas P, Perret GY, et al. Does delaying adjuvant chemotherapy after curative surgery for colorectal cancer impair survival? A meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(6):1049–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]