Abstract

Background

There is widespread agreement about the importance of communication skills training (CST) for healthcare professionals caring for cancer patients. Communication can be effectively learned and improved through specific CST. Existing CSTs have some limitations with regard to transferring the learning to the workplace. The aim of the study is developing, piloting, and preliminarily assessing a CST programme for hospital physicians caring for advanced cancer patients to improve communication competences.

Methods

This is a Phase 0-I study that follows the Medical Research Council framework; this paper describes the following sections: a literature review on CST, the development of the Teach to Talk training programme (TtT), the development of a procedure for assessing the quality of the implementation process and assessing the feasibility of the implementation process, and the pilot programme. The study was performed at a 900-bed public hospital. The programme was implemented by the Specialized Palliative Care Service. The programme was proposed to 19 physicians from 2 departments.

Results

The different components of the training course were identified, and a set of quality indicators was developed. The TtT programme was implemented; all the physicians attended the lesson, videos, and role-playing sessions. Only 25% of the physicians participated in the bedside training. It was more challenging to involve Haematology physicians in the programme.

Conclusions

The programme was completed as established for one of the two departments in which it was piloted. Thus, in spite of the good feedback from the trainees, a re-piloting of a different training program will be developed, considering in particular the bed side component.

The program should be tailored on specific communication attitude and believes, probably different between different specialties.

Keywords: Palliative care, Communication training, Oncology, Complex intervention

Background

There is widespread agreement on the importance of communication skills training (CST) for healthcare professionals caring for cancer patients [1, 2]. The literature indicates that honest and open communication with cancer patients can improve adherence to treatment programmes [3, 4] and lead to benefits for physicians [4–6]. Conversely, poor communication leaves patients alone with their worries and anxiety [7], while professionals become more prone to dissatisfaction and burnout [8].

As highlighted in a number of studies, physician-patient communication can be effectively learned and improved through specific training programmes [2, 9–19]. Nevertheless, the transferability of trainees’ acquired competences to the clinical setting is difficult for range of reasons:

CST are usually intensive residential programmes held outside trainees’ workplaces and attended by participants from different work environments and setting

CST are usually implemented by psychologists or experts from psychiatry and behavioural sciences who, de facto, are not directly involved in physician-patient communications

experiential learning techniques usually employed within these training, such as role playing with peers or trained actors, are not real encounters with real patients, which included in only a minority of programmes.

As many difficult conversations take place in hospitals, all health professionals should be trained to engage in them.

Any hospitals physician should be able to converse about a prognosis, the goals of treatment at the end of life and managing global suffering [20]. To achieve these objectives, a primary palliative care curriculum must be taught, and education about communication issues regarding advanced illness should be the starting point. It is widely documented that the development and implementation of a communication training course is necessary for generalist palliative care physicians to develop core competencies is this area.

Beginning from limitations acknowledged by the literature about existing CST, we developed a novel communication training programme addressed to hospital physicians caring for oncologic patients with palliative care needs, conceived to be implemented inside participants’ workplace (i.e. the hospital), held by specialized palliative care and including encounters with real patients among experiential learning techniques.

The SPIKES protocol, developed in USA with the aim of teaching communication skills at the end of life to medical oncology fellows, was the theoretical model that inspired the programme [21]. It consists in a six steps protocol, each of which is associated with a specific skill (Setting up the interview, assessing the patients’ Perception, obtaining the patients Invitation, giving Knowledge and information to the patients, addressing the patient Emotion, Strategy and Summary).

The training was developed, implemented, assessed and evaluated as a complex intervention [22, 23] according to a phase 0-I of the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework [22, 23].

Our paper describes the phases guiding this process:

developing a communication training programme focused on hospital physicians caring for advanced cancer patients;

developing an evaluation system to assess the quality of the implementation;

launching and preliminarily assessing both the programme and the evaluation system

Methods

This is a mixed-method, Phase 0-I study that follows the MRC framework for the assessment of complex interventions [22, 23]. According to this framework, it is useful to consider the process of development and evaluation of complex interventions as having several distinct phases. These can be compared with the sequential phases of drug development or may be seen as more iterative. Progression from one phase to another may not be linear. In many cases an iterative process occurs. Preliminary work is often essential to establish the probable active components of the intervention so that they can be delivered effectively during the trial. Identifying which stage of development has been reached in specifying the intervention and outcome measures will give researchers and funding bodies reasonable confidence that an appropriately designed and relevant study is being proposed.

The study was subdivided into three phases.

Phases of the project

Phase 1: developing the communication training programme

SPIKES protocol [21] was the theoretical model that inspired the programme. Besides, we performed a review of systematic reviews on existing communication training programmes with a focus on oncology and palliative care. The PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library CINHAL and Scopus databases were searched using the MeSH terms [cancer OR tumour OR neoplasm OR oncol*] AND [systematic] AND [communication skills OR communication strateg* OR communication training] for English language articles published until December 2015. An author (S.T.) reviewed the studies’ titles and the abstracts. Screening for full texts was undertaken by two authors (S.D.L. and S.T.).

A sample of physicians who were potentially eligible for the training were preliminarily interviewed, with the aim of gathering information on their perceived training needs in this field and developing the programme accordingly. Interviewed physicians were 4 males and 2 females with a mean age of 52 years (range: 41–67) and an average professional experience of 25 years (range: 18–43). Interviews were analysed qualitatively through thematic analysis [24]. In Table 1 interview’s topic and questions are reported.

Table 1.

Interview guide on physicians’ perceived training needs

| Topic | Question |

|---|---|

| Training needs | Could you please tell me which are your major difficulties in communicating bad news to advanced cancer patients and their relatives? |

| Can you please give me any specific examples? | |

| According to your opinion which are the major difficulties of your colleagues? | |

| Perceived self-strengths/resources | Regarding your difficulties in bad communication, could you please tell me what are the strengths of your communication, according to your opinion? |

| Expectations about the training program | Could you please tell me which are your expectations about the training program? |

Phase 2: assessing the quality of the implementation

This phase was aimed at developing specific procedures to assess the consistency of the implementation process. A set of indicators was developed for a twofold purpose: the first was to assess whether the programme was delivered exactly as outlined and the second was to evaluate each component of the intervention. Thus, information on the objectives achieved or not achieved was collected for each component of the programme (Table 2). The procedure included a semi-structured questionnaire on the perceived usefulness of the programme (Table 3).

Table 2.

The quality improvement programme with indicators

| Dimension | Rationale | Indicators | Expected standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| General training in palliative care | A basic training on palliative care is necessary to educate the future trainees on palliative care topics (e.g., communication) | Proportion of ward physicians attending the 4-h basic training | 100% |

| Request to receive the communication training | A perceived need that training in communication is important for changing future behaviour | Call from the head of the department for communication training | Requested |

| Developing the documentation for the training | Specific documentation is mandatory | Received the documentation | Received |

| Didactic lesson | Little basic knowledge on delivering bad news is necessary | Proportion of ward physicians attending the didactic lesson | 75% of the participants attend the didactic lesson |

| Videos | An overview of and a preliminary discussion on different teaching methods prepare students for the didactic lesson | Proportion of ward physicians participating in the video sessions | 100% |

| Role playing | Experiential learning as role playing improve behavioural changes in trainees | Proportion of ward physicians attending at least 2 role playing sessions; proportion of ward physicians performing in at least 2 role playing sessions, at least one as a patient/relative and one as the physician | 75%;75% |

| Bedside trainings | Real-life training improves participants’ awareness of their communication style | Proportion of ward physicians attending at least 3 bed-side sessions | 75% of the participants attend the bed-side training |

| Semi-structured questionnaire on the perceived usefulness of the programme | A self-evaluation of the usefulness of the training components can improve both the structure and contents of the programme | Proportion of physicians attending the whole programme and completing the questionnaires | 100% |

| Bedside training follow up | Follow-up sessions control and re-enforce the maintenance over time of the training course | Proportion of ward physicians performing at least 2 bed-side session follow ups | 75% |

Table 3.

Semi-structured questionnaire on the perceived usefulness of the TtT programme

| How helpful do you think the 4 components have been with regard to | Delivering bad news to patients and families, % quite/extremely | Exploring patient’s concerns and wishes about illness, % quite/extremely | Building empathy, % quite/extremely |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Lesson | 100 | 86 | 86 |

| 2) Video screening | 100 | 100 | 86 |

| 3) Role playing | 86 | 100 | 100 |

| 4) Bed-side training | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Phase 3: assessing feasibility and implementation methods

This phase was aimed at assessing the feasibility of the implementation process within the hospital setting. Both the intervention and the procedure used to assess the quality of the implementation were implemented through a convenience sample of two hospital teams.

We considered the programme feasible if:

the components of the training course were appropriately identified

the set of quality indicators was developed and implemented

the programme was completed as established for the two hospital departments.

Where feasibility was not achieved, the programme included interviews with trainees to detect difficulties and weaknesses of the programme itself (Table 4).

Table 4.

Interview guide on physicians’ difficulties in completing the programme

| Topic | Physicians questions |

|---|---|

| Project involvement | Could you please tell me what you thought about this training program when you heard about it? |

| Expectations | What were your expectations in the project? |

| Perceived benefits/weakness | Regarding this project, could you please tell me what the strengths of this intervention were, according to your opinion? If it impacted on your usual job, how did it do? |

| And what about its weakness? | |

| Short report of the experience | Regarding this program, could you please tell me what do you remember about the lesson/the role play? |

| Did you complete the training program in all its components? | |

| Future suggestions | As health professional, could you please tell me any suggestions for future training program? |

Population and context

The study was performed at the Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova of Reggio Emilia. This is a 900-bed Italian research hospital, accredited as a Clinical Cancer Centre by the Organization of European Cancer Institutes (OECI). The Specialized Palliative Care Service (SPCS) is a specialized hospital-based unit with no beds whose mission is to perform clinical, training and research activities in palliative care. The unit was established in 2013, and at present, it includes two senior physicians and three advanced practice nurses, one of whom is devoted to training courses full-time. Psychologists from the hospital Psycho-Oncology Unit cooperate with the SPCS by holding clinical consultations and taking charge of SPCS staff training.

The training was overseen by the two palliative care physicians, the senior nurse specialized in training methodology from the SPCS, and three psychologists from the Psycho-oncology Unit. Based on prior experience in developing and leading communication courses in oncology and palliative care [9, 13, 25, 26], three of the training teachers (S.T., S.D. L and G. A) trained another palliative care physician (S. A.) before the beginning of the programme with the aim of providing her with the competencies needed to act as a teacher.

We proposed the programme to all physicians from the Medical Oncology and Haematology Departments. The Medical Oncology Department provides care for patients with advanced onco-haematological diseases. The department has 20 beds and four physicians. The Haematology Department provides care to haematological patients at all disease stages. The department has 16 beds and 15 physicians. Trainees from both departments were senior physicians. Four were physicians from the Medical Oncology department, four from the Haematology ward, ten from the Haematology day care unit and one from the Haematology home care unit. Only one physician from the Medical Oncology Department had been previously involved in a training course in communication.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Reggio Emilia on 12 June 2015 (n 861/12.6.2015) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm).

Data analysis

Phase I

An author (S.T.) reviewed the studies’ titles and the abstracts for the review of systematic review. Screening for full texts was undertaken by two authors (S.D.L. and S.T.).

The interviews with professionals before the implementation of the programme were recorded, transcribed, and analysed qualitatively with the objective of exploring in detail physicians’ perceived training needs (Table 5). Two researchers (ST and SDL) independently read the transcripts and categorized them into themes [24]. Any disagreement between the researchers was discussed, and a final categorization was determined.

Table 5.

Themes, sub-themes and representative quotations from qualitative analysis of 6 physicians interviews

| Themes and subthemes | Representative quotations |

|---|---|

| Communication difficulties | |

| Communicating the end of active therapy | “… Trying guide the patients through small steps toward their real situation [the end of curative treatments] is a sort of ‘art of the relationship’, to build through small steps” (Ph 2) |

| “When you comes to this point [the end of curative treatments] there is a difficulty in transferring this information to the patient.. This conversation should be anticipated much earlier and not just when you stop the treatment” (ph 3) | |

| Talking about prognosis | “Telling to a patient the prognosis ... There is always something to do but, from that precise moment, you start to lie ... Obviously, I can’t say that there are four weeks of survival left!” (Ph 1) |

| “Sometimes there is a sort of omission in communicating a poor prognosis to the hematological patient. This step can really missing …” (Ph 3) | |

| “Communicating the prognosis to a patient you have known for a long time. We always tend to show the glass half full …” (Ph 4) | |

| Handling interference from relatives | “There are family members who ‘overturn’ the suffering of their loved one not to the disease but the work of health professionals” (ph 1) |

| “Situations in which there is an oppositive behavior or even an aggression by family members, and these become the cases that are most difficult to manage” (Ph 2) | |

| “Families who do not give up, who cannot cut this sort of umbilical cord that unites them with their loved one …” (Ph 3) | |

| “The relative who continues to search and ask for treatments even when things are over” (Ph 5) | |

| Source of communication competencies | |

| Experience | “I have to say that age and experience help me, so it is easy for me knowing both advanced cancer patient’s previous history and how that history will continue in the future. Therefore, I can also ‘touch’ the sensitive points of what that patient would like to be told, to know …” (Ph 1) |

| “It seems to me that I have absorbed some communication techniques ... I would not seem presumptuous” (Ph 2) | |

| “Our thirty years of experience, in my opinion, is enough!” (Ph 6) | |

| Collaboration with colleagues | “In some situations, your resources are not enough. Then you ask for help to other specialists who will be the psychologist, or the palliative care physician, or your collaborators and colleagues” (Ph 1) |

| “I learned communication from briefings, structured meetings, meetings with colleagues on more complex cases” (Ph 3) | |

| “The confrontation with our team ... with the psychologist” (Ph 4) | |

| “We improved in keeping a common line when we communicate with patients, and this helps” (Ph 5) | |

| Personal attitude | “Patients and relatives confirm that I can establish a fairly empathic relationship with them. This probably derives from my previous training, from my personality, from my capacity of getting understandably and easily certain speeches” (Ph 2) |

| “Surely there is an attitude allowing me to easily establish relationship with patients ... an ability to listen to them ... an attitude in understanding them... adaptability ... sensitivity ...” (Ph 1) | |

| Expectations toward the training | |

| Becoming more empathetic | “Knowing how to leave a little hope even in the face of bad news” (Ph 6) |

| “Knowing how to give more consolation when the epilogue cannot be favorable” (Ph 1) | |

| Improving communication with colleagues | “Knowing how to listen more my colleagues, other operators. The clinical eye of the nurse for example” (Ph 3) |

| “Improving communication between operators” (Ph 5) | |

| Experiencing less stress | “Approaching myself in a less stressful way in the face of these bad communications that we have to deliver every day” (Ph 4) |

Phase II

An overview of the objectives achieved and not achieved for each component of the implementation of the programme was obtained through an analysis of the pilot implementation process (Table 2). The answers to the semi-structured questionnaire about the perceived usefulness of each component of the programme (Table 3) were analysed by means of descriptive statistics. The usefulness of each component (i.e. lesson, videoscreening, role playing, bed-side training) was assessed by considering the three main objectives of the training (i.e. delivering bad news, exploring patients’ concerns and supporting them and building empathy).

Phase III

The interviews with professionals concerning difficulties encountered by physicians in completing the implementation process (Table 4) were recorded, transcribed, and analysed qualitatively with the objective of exploring in detail reasons related to problems with training completion (Table 6). ST and SDL independently read the transcripts and categorized them into main themes according to the objective of the evaluation. Any disagreement between the researchers was discussed, and a final categorization was determined.

Table 6.

Themes and representative quotations from qualitative analysis of interviews with physicians who did not complete the training

| Themes | Representative quotations |

|---|---|

| Global feedback on the training | “The only thing was my discomfort facing other people during role play I think that role play should be avoided in the presence of other colleagues. [...] Observer teachers are one thing, because they have to help you see some mistakes, your colleagues are another thing.” (Ph 1) |

| “It was difficult ... Not so much when you play your part but when we analysed things ... Everyone has difficult cases outstanding ... It was difficult to cope with the return to the memory of cases that I had not yet worked out”. (Ph 4) | |

| “I remember that during the theorethical lesson S.T. [the teacher] stated that we must be able to highlight with the patient the end of his/her life … and that we have to do this in a very clear way … which is something that I do not agree because … at the end you always have to give hope to the patient. Besides, our patients already know when their time has come, so there’s no point in stressing it. Then if we want to underline it with family members, that’s due!” (Ph 1) | |

| “I remember the role plays very well. […]Role plays have impressed me a lot. I don’t remember anything in particular about the theoretical lesson ... “(Ph 3) | |

| Organizational issues | “Also palliative care physicians have a number of things to do, and this could be a limitation …” (Ph 4) |

| “With reference to the training, I think that It should be planned having in mind both the characteristics of haematological patients and our great workload” (Ph 2). | |

| Misunderstandings about the structure of the programme | Interviewer “May I ask you if you have completed all the communication training? Did you carry it out in all its parts?” […] |

| Ph 1: “Yes, I did. I had one problem only … My distress in front of other persons, during the role-playing sessions …” | |

| “It was a training including either a theoretical, a practical and a field component. I still have to achieve this part because when I needed to communicate some kind of diagnosis, I could not arrange for a meeting with S. [the trainee]. Thus, I still have to do it. I will call S.T. when I will have to communicate a ‘bad’ diagnosis”.(Ph 3) | |

| Problems in detecting the “right” situation | “I could not attend the bedside sessions because I needed to communicate an illness diagnosis, thus S.T. said that I should call her when I had to perform a truly difficult communication!” (Ph 4) |

| “Our patients can get worse from one moment to the next, so you make a good plan but ... it’s hard to keep up with this!” (Ph 1) |

Results

Phase 1: developing the communication training programme

The literature review

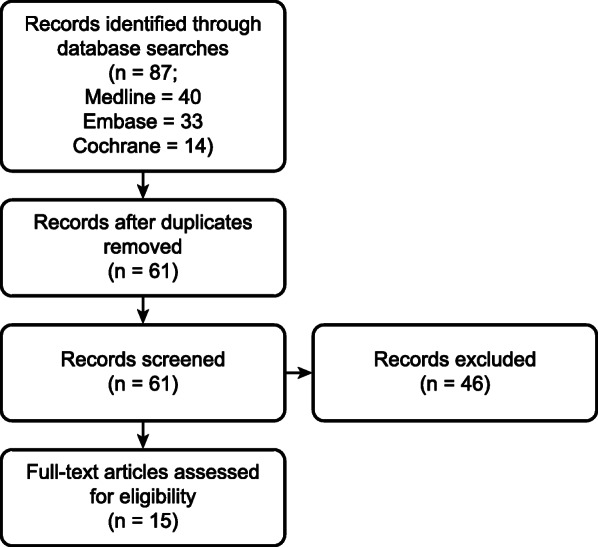

The literature selection process is summarized in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1). The search identified 87 records. A total of 61 duplicates were removed, and 43 abstracts were excluded due to ineligibility. Fifteen systematic reviews of CST in oncology and palliative care were included in our review [14, 27–40].

Fig. 1.

Flow chart

The following recommendations arose from the analysis of the retrieved papers:

Communication training should be developed and delivered by professionals with both skills and expertise in the field. Facilitators should practice the skills they learn [32, 39, 41].

Courses should be addressed to small groups of professionals (4–6 persons) [41].

Successful training courses should last at least 1 day, although there is evidence that the best results come from training courses conducted over a longer period [28, 31, 33, 37, 38].

Follow-up sessions are also indicated as a promising strategy aimed at reinforcing and maintaining acquired skills over time [17, 38, 41].

Courses should be learner-centred and practice-oriented and should use a combination of didactic and experiential methods [28, 31, 33–35, 41, 42], such as role playing [17, 28, 34–36, 39, 43].

The interviews with physicians

A convenient sample of 6 out of 19 physicians participating in the programme were interviewed 1 month before the implementation of the training course to collect their perceived training needs and consequently tailor the contents of the course to them. The major difficulties reported by the trainees concerned three topics: communicating the end of active therapy, talking about prognosis and handling interference from relatives with physicians’ choices with regard to communication with patients about illness. The interviewees considered their communication competencies derived from either field experience, collaboration with colleagues, and nurturing personal attitudes such as sensitivity. Becoming more empathetic in communicating hope, improving communication with colleagues and experiencing less stress and emotional involvement during difficult conversations with patients and their relatives were the interviewees’ expectations regarding the course (Tables 1 and 5).

The Teach to Talk programme

According to the literature, existing programmes suffer from a number of limitations: courses are usually residential and are implemented for trainees from different work environments, experiential learning techniques based on role playing with actors make use of simulated scenarios that are very different from real encounters with patients and relatives, facilitators are not directly involved in clinical practice, and training courses are not implemented within the real contexts in which physicians communicate with patients.

Considering both the recommendations and criticisms raised from the literature review as well as the difficulties that emerged from the analysis of the interviews with physicians, we developed a novel intervention named “Teach to Talk” (TtT) training programme. The key features of the programme are the following:

the programme is implemented within the participants’ hospital ward, i.e., in the context in which participants are required to practice the communication skills they are learning;

the programme includes peer to peer role playing;

the programme includes bedside sessions with real patient encounters;

teachers are professionals from the hospital SPCS. They are supported by professionals with a psychosocial background, such as psychologists or counsellors.

Inspired by the contents of the SPIKES protocol, the “Teach to Talk” (TtT) programme is aimed at improving physicians’ competencies in the following three broad areas: 1) delivering bad news, 2) exploring patients’ concerns and supporting them, and 3) building empathy.

The SPCS delivers the intervention in five components: video screening, didactic lesson, role playing, bedside training and follow-up. The TtT components as well as the procedures concerning their implementation are described in detail in Table 7.

Table 7.

The Teach to Talk (TtT) programme

| 1. Video screening. Participants are asked to watch didactic videos representing clinical consultations in which the communication skills involved in the above-mentioned tasks are practiced by actors. | |

| 2. Didactic lesson. Subsequently, the participants are provided with an introductory didactic lesson concerning the communication skills needed to deliver bad news, how to explore patients’ concerns and how to build empathy. The discussion between the trainees is focused on both issues from the videos and from the presentation of an actual scenario chosen by the participants. This component is delivered in three hours. | |

| 3. Role playing. Beginning in the week after the lesson, role playing sessions are organized, each involving no more than 4 physicians, in which 2 act as actors and the others as observers. Two consecutive role-playing sessions are scheduled at a time, each one lasting about one and half hours. The communication scenarios are proposed by the participants and are based on real situations that they have experienced on the field. | |

| 4. Bed-side training. Each participant is supported by a member of the PCT implementing the program in conducting a number of consultations with in- or out-patients, where difficult communication tasks are involved. Bed-side trainings (three per participant) are planned with trainees after the completion of the role play sessions. Each bed-side training is preceded by a briefing aimed at sharing communication objectives and how to manage different scenarios, and the trainings are followed/concluded by a debriefing in which the trainee’s strengths and weaknesses concerning the performed communication tasks are discussed. The Breaking bad news assessment schedule (BAS) is used to guide the discussion [44]. | |

| 5. Follow-up. The follow-up phase takes place 6 months later and consists of 2 bed-side trainings per participant, featuring the structure described above. | |

| The entire program should be concluded in 6-10 weeks. |

Phase 2: quality assessment of the programme

The procedure to assess the quality of the programme included a list of indicators covering all of its components (see Table 2). With reference to the lesson, videos, role playing and bedside sessions, a 75% minimum attendance rate was estimated by researchers to be reasonable, which is consistent with the study aims. The time spent by the facilitators teaching the training course was also recorded.

Phase 3: preliminary assessment of the programme: the evaluation system

The heads of the two departments and all 19 physicians from the two departments agreed to participate in the programme (Table 8). The intervention was implemented between December 2015 and June 2017.These stages are planned as shown in the Gantt Diagram (Table 9).

Table 8.

Participants demographic characteristics

| Department | Sex (male:female) | Age (years) Average | Work experience (years) Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Oncology | 2:2 | 56 (47–67) | 27 (12–43) |

| Haematology | 10:5 | 46 (36–60) | 16 (4–32) |

Table 9.

The Gantt diagram of the TtT training programme

| Theoretical lesson | Role Play | Bed Side | Follow up bed side | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical oncology Department | November 2015 | December 2015 | December 2015 | December 2015–January 2016 |

| Hematology Department | January 2017 | February 2017 | February-june 2017 | Not done |

Table 10 summarizes the main findings of the pilot study. The staff from both wards had previously attended general palliative care training. After requesting communication training from the SPCS, these staff members were duly contacted to schedule the preliminary assessment of the participants’ needs for communication training. The issues raised during the interviews were used as a framework to prepare both the lesson and the role-playing sessions. Other topics from the emotional domain were also considered.

Table 10.

The results of the TtT programme

| Dimensions | Medical Oncology Department | Haematology Department |

|---|---|---|

| General training in palliative care | 100% | 100% |

| Request to receive the communication training | Requested | Requested |

| Developing the documentation for the training | Received | Received |

| Didactic lesson | 100% | 100% |

| Videos | 100% | 100% |

| Role playing | 100% | 100% |

| Bedside trainings | 100% | 6% (1/15) |

| Semi-structured questionnaire on the perceived usefulness of the programme | 100% | 20% (3/15) |

| Bedside training follow up | 75% (3/4) | 0% |

The SPCS prepared the documentation for both the lesson and the role-playing session, as established at the outset. As was laid out in the programme, the training was conducted entirely in the participants’ work environment in small groups. Both the lesson and the role-playing sessions were attended by all the participants. The goals to be achieved during the role playing were changed from those set out in the protocol because the researchers decided to use clinical examples proposed by the trainees. The staff from Medical Oncology completed the entire programme, while those from Haematology completed only part of the programme. Indeed, only one physician completed the entire programme in 6 months. Four did not perform any bedside training sessions. For two of staff members, the trainers did not deem it to be useful for them to complete three bedside training sessions, and the competences they had acquired were judged to be sufficient by the trainers. One physician completed the entire training. The remaining 8 physicians performed only one bed side session.

In addition to the training, follow-up was performed, as established by the programme, by only 3 physicians from the Medical Oncology Department.

The results from the semi-structured questionnaire administered to the physicians who completed the training showed that all the components, particularly the role playing and bedside training sessions, were evaluated as useful or very useful by participants.

Both the didactic lesson and the role-playing sessions were jointly conducted by a palliative care physician from the SPCS and a psychologist from the Psycho-oncology Unit. The synergic approach of the facilitators guaranteed a sort of double perspective in guiding the trainees, both in relation to learning and using appropriate communication skills and to recognizing and managing difficult emotions. Throughout the implementation of the programme, physicians facilitating the bedside training sessions were constantly supervised by the psychologists involved in the project and by a senior nurse training expert. A portfolio was used as a guide to the supervision process.

Findings from the interviews with the four physicians who did not request bedside sessions provide insights into criticisms concerning the implementation of this component, as well as on their comprehensive view on the training. Following, themes emerged from qualitative analysis are briefly described, representative quotations for each theme are reported in Table 6.

Global feedback on the training

Two physicians expressed some discomfort in participating to role plays, emphasizing in one case a feeling of embarrassment to be observed by colleagues and in the other an unpleasant sensation of arousal linked to the memory of some emotionally demanding relationships with patients. One physician reported on her disappointment toward a message acknowledged during the theoretical lesson, concerning the relevance of communicating to patients a poor prognosis. On the whole, interviewed physicians highlighted that the educational value of role plays and videos was greater than that of the theoretical lesson.

Organizational issues

Some participants referred to practical difficulties in predicting when they have the time to engage themselves in a critical communication with a patient concerning, for example, the end of the active provision of treatment. Problems also emerged because, according to interviewed physicians’ opinion, the trainers themselves were very busy with their clinical activities.

Misunderstandings about the structure of the programme

One physician was convinced she had completed the entire training course, while another was still trying to arrange an encounter with the trainer.

Problems in detecting the “right” situation

A physician explained that, during the training, she had to communicate bad news concerning only illness diagnosis, a task perceived as less challenging and difficult than communicating a poor prognosis. Another physician highlighted her difficulty in knowing in advance whether she should have to cope with a difficult communication scenario due to rapid changes in patients’ condition.

Discussion

This study focused on the development of a communication training programme, indicators of the fidelity of the implementation, the different components of the intervention and its preliminary assessment. The programme was completed as established for one of the two departments in which it was piloted; for the Haematology department, bedside training and the consequent follow-up sessions were missing. Thus, in spite of the high perceived utility expressed from the trainees, major changes are needed to ensure the feasibility of this training program.

We developed our intervention and included all the components evaluated as essential in the last ASCO statements [45]. We chose to offer only one lesson, which was attended by all the participants from both wards, and we used role-playing between peers to allow for safe interaction between colleagues within the small-group setting and peer-reviewed the feedback, which a number of studies stated were effective tools [36, 46–54]. This approach was also highlighted in our pilot study, where participants evaluated the role playing sessions in which they took part as highly useful.

Regarding the bedside training, recent studies [55, 56] have suggested and proved the importance of coaching after didactic modules because of its focus on individual learning goals and the possibility of tailoring training to personal weaknesses. One-to-one coaching by palliative care physicians was also the main tool used in the study by Clayton et al. [56] on a group of voluntary, junior doctors. Satisfaction with the course was expressed by the participants, but only one-third of the participants saw improvement in their communication skills.

In our pilot study, most physicians from the Haematology ward did not receive this coaching session (bedside training), even though there had been a formal request by the heads of the ward to participate in the training and the training met the specific needs expressed by physicians during the preliminary need assessment.

Two main reasons could explain the major limitation of our training programme: first, haematologists must address organizational issues, as declared in some interviews; second, theoretical and cultural issues underlying the haematologists’ concept of palliative care and the palliative care approach should be taken into account as contributory factors.

The Teach to Talk programme has been implemented since 2015 by an SPCS inside the hospital. The interaction with the Haematology ward is well documented by the increasing number of year-to-year consultation requests. Interaction between palliative care and haematology has been explored by recent literature. Although the value of palliative care is recognized by haematologists, there still seems to be resistance to the reality and practicalities associated with the referral of haematologic patients to palliative care services [57].

In literature a great amount of evidence underscores the difficult of hematologists to recognize patients’ poor prognosis and talk with them about it [58–60]: in the study by Alexander, a lack of patients involvement in decision about treatment, as well a tendency to avoid prognostic discussion emerge in the analysis of video recorded real encounters with patients. Hematologists participants in a qualitative research [57] acknowledge taking a paternalistic approach towards certain decisions and explained their therapeutic optimism in order to bolster patients in toxic but curative treatments. The intention ‘not to give up’ was strengthened by the intense physician-patient relationship and by the unpredictable nature of the treatment itself [57]. The hematologic patient is described differently from the oncologic one for the no predictable disease’s trajectory [60, 61] thus, the right moment to share a bad communication could be not so clear.

These difficulties were similar with problems raised by the haematologists in our study, for instance, with regard to the appropriate time to communicate with patients regarding the turning point of an illness (e.g., the end of active treatment or disease leading to poor prognosis). An international trial by Szekendi et al. [62] highlighted the impact of embedding a palliative care team with a selected non-palliative care service: non-palliative care physicians report an increase in comfort as well as in their skills in conducting care conversations.

As far as we know, few training courses in communication are addressed to haematologists and thus focus on their specific communication needs [63]. At the same time, communication remains a challenge for haematologists. Formal communication skills training and target interventions for patients with haematologic malignancies by palliative care staff have been called for by some authors [64, 65].

We developed a set of indicators to assess the quality of the implementation. We propose to take these indicators into account in every setting to expedite implementation. In particular, we believe the preliminary stages (general training in palliative care, requests to receive the communication training, communication need assessment) to be mandatory to improve core competencies in basic palliative care for other professionals.

Findings from this study need to be interpreted by acknowledging some limitations. We have initiated the programme at only one clinical cancer centre. Nevertheless, we launched our project within a coherent methodological framework. This approach involved the recommendation to assess the local feasibility of complex interventions so the project can be amended as necessary and evaluated on a larger scale.

The results of this study strongly suggest the need for developing a revised version of the TtT programme. In hospital settings, the duration of the intervention should be longer than 8 weeks, depending on the specific characteristics of the ward in which it is implemented (e.g., number of physicians, professionals’ training needs, frequency of bad news communication, organization of work). The number of bedside sessions per participant should be determined on the basis of the competencies acquired by single participants throughout the training in accordance with the facilitator’s judgement.

Bedside sessions should be scheduled a priori with facilitators rather than self-managed by participants because self-management, an active and proactive behaviour, may facilitate concrete change in communication attitudes.

Conclusions

In the last 10 years, research from the literature emphasized that training in communication skills is not enough to bring about real change in professional attitudes [19, 27, 66, 67]. We implemented an educational intervention with a well-integrated palliative care team in order to overcome limitations of existing residential training programmes and to impact communicative behaviour in the contexts where professionals actually work. However, major changes are needed to ensure the feasibility of this training programme.

Turrillas et al. [68] argue that the most effective training method should be tailored to the environment and context. A re-piloting of a different training program will be developed, considering in particular the bed side component.

Moreover the program should be tailored on specific communication attitude and believes, probably different between different specialties as emerged in our interviews to haematologists.

Acknowledgements

We would like to pay tribute to all the physicians from the Medical Oncology and Haematology Departments for their goodwill and trust in our team. We are also grateful to Dr. W. Baile: without him, our love for communication teaching would never have been pursued.

Abbreviations

- MRC

Medical Research Council

- SPCS

Specialized palliative care service

- CST

Communication skill training

- TtT

Teach to talk

- ASCO

American society of clinical oncology

- BAS

Breaking bad news assessment schedule

Authors’ contributions

ST made a substantial contribution to this study, from its concept to the realization of the program, interpretation of the data, draft of the article and its revision. DPL made a substantial contribution to the concept of the design of the work and critically revised the article for important intellectual content. CM contributed to the design of the work, analysis and interpretation of the data, critically revised the article. AS and AG contributed to the realization of the program. D.L.S made a substantial contribution to the realization of the program, the analysis and interpretation of the data and drafting of the article. All authors approved the version to be published.

Funding

The present research was performed independently and did not receive any internal or external funding.

Availability of data and materials

The study documentation is collected and managed by the coordinator of the study centre (PC Unit, AUSL – IRCCS di Reggio Emilia), and datasets are available on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study involves a specific information note and a consent form with the relevant resolution of the data. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

The approval of this study was subject to the opinion of the Provincial Ethics Committee of Reggio Emilia Comitato Etico di Area Vasta Emilia Romagna Nord (AVEN), in consideration of the Protocol, the privacy policy, the relative informed consent forms, the interview used in the and the questionnaire addressed to the professionals.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee on 12 June 2015 (n 861/12.6.2015).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Block SD, Billings JA. A need for scalable outpatient palliative care interventions. Lancet. 2014;383:1699–1700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62676-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiefel F, Kiss A, Salmon P, et al. Training in communication of oncology clinicians: a position paper based on the third consensus meeting among European experts in 2018. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:2033–2036. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee SC, Matasar MJ, Bylund CL, et al. Survivorship care planning after participation in communication skills training intervention for a consultation about lymphoma survivorship. Transl Behav Med. 2015;5:393–400. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0326-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bialer PA, Kissane D, Brown R, et al. Responding to patient anger: development and evaluation of an oncology communication skills training module. Palliat Support Care. 2011;9:359–365. doi: 10.1017/S147895151100037X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Asai M, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of communication skills training program for oncologists based on patient preferences for communicating bad news. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12:379–386. doi: 10.1017/S147895151300031X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gattellari M, Ward JE, Solomon MJ. Randomized, controlled trials in surgery: perceived barriers and attitudes of Australian colorectal surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1413–1420. doi: 10.1007/BF02234591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donovan-Kicken E, Caughlin JP. Breast cancer patients’ topic avoidance and psychological distress: the mediating role of coping. J Health Psychol. 2011;16:596–606. doi: 10.1177/1359105310383605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanafelt T, Dyrbye L. Oncologist burnout: causes, consequences, and responses. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1235–1241. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baile WF, De Panfilis L, Tanzi S, et al. Using sociodrama and psychodrama to teach communication in end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:1006–1010. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costantini A, Baile WF, Lenzi R, et al. Overcoming cultural barriers to giving bad news: feasibility of training to promote truth-telling to cancer patients. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24:180–185. doi: 10.1080/08858190902876262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenzi R, Baile WF, Costantini A, et al. Communication training in oncology: results of intensive communication workshops for Italian oncologists. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20:196–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamiani G, Meyer EC, Leone D, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation of an innovative approach to learning about difficult conversations in healthcare. Med Teach. 2011;33:e57–e64. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.534207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morasso G, Caruso A, Belbusti V, et al. Improving physicians’ communication skills and reducing cancer patients’ anxiety: a quasi-experimental study. Tumori. 2015;101:131–137. doi: 10.5301/tj.5000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gysels M, Richardson A, Higginson IJ. Communication training for health professionals who care for patients with cancer: a systematic review of effectiveness. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:692–700. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maguire P, Faulkner A, Booth K, et al. Helping cancer patients disclose their concerns. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32a:78–81. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiss A. Communication skills training in oncology: a position paper. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:899–901. doi: 10.1023/A:1008340806731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, et al. Enduring impact of communication skills training: results of a 12-month follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1445–1449. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, et al. Efficacy of a cancer research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:650–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stiefel F, de Vries M, Bourquin C. Core components of communication skills training in oncology: a synthesis of the literature contrasted with consensual recommendations. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2018;27:e12859. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1173–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES-A six step procol for delivering bad news:application to the patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5:302–311. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000;321:694–696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ. 2007;334:455. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39108.379965.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanco K, Rhondali W, Perez-Cruz P, et al. Patient perception of physician compassion after a more optimistic vs a less optimistic message: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:176–183. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Priami D, Sollami A, Vivoli V, et al. Tutorship process in health care professions: a survey investigation in Emilia Romagna. Acta Biomed. 2015;86(Suppl 2):97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barth J, Lannen P. Efficacy of communication skills training courses in oncology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1030–1040. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gysels M, Richardson A, Higginson IJ. Communication training for health professionals who care for patients with cancer: a systematic review of training methods. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:356–366. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0732-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Interactive technologies and videotapes for patient education in cancer care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:7–20. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0112-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uitterhoeve RJ, Bensing JM, Grol RP, et al. The effect of communication skills training on patient outcomes in cancer care: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19:442–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, et al. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:903–918. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore PM, Rivera Mercado S, Grez Artigues M, et al. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD003751. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003751.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berkhof M, van Rijssen HJ, Schellart AJ, et al. Effective training strategies for teaching communication skills to physicians: an overview of systematic reviews. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Libert Y, Conradt S, Reynaert C, et al. Improving doctor’s communication skills in oncology: review and future perspectives. Bull Cancer. 2001;88:1167–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rao JK, Anderson LA, Inui TS, et al. Communication interventions make a difference in conversations between physicians and patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Med Care. 2007;45:340–349. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254516.04961.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lane C, Rollnick S. The use of simulated patients and role-play in communication skills training: a review of the literature to August 2005. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lannen P, Barth J. Do communication skills trainings improve behavior, attitude and patient outcomes equally? Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2009;18:S103. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fellowes D, Wilkinson S, Moore P. Communication skills training for health care professionals working with cancer patients, their families and/or carers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD003751. 10.1002/14651858.CD003751.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Bialer PA, Gilewski T, Kissane D, et al. The development and implementation of an institution-based communication skills training program for oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:9128. doi: 10.1200/jco.2010.28.15_suppl.9128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walsh RA, Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW. Breaking bad news. 2: what evidence is available to guide clinicians? Behav Med. 1998;24:61–72. doi: 10.1080/08964289809596382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stiefel F, Barth J, Bensing J, et al. Communication skills training in oncology: a position paper based on a consensus meeting among European experts in 2009. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:204–207. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Faculty development to change the paradigm of communication skills teaching in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1137–1141. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aspegren K. BEME Guide No. 2: teaching and learning communication skills in medicine-a review with quality grading of articles. Med Teach. 1999;21:563–570. doi: 10.1080/01421599978979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller SJ, Hope T, Talbot DC. The development of a structured rating schedule (the BAS) to assess skills in breaking bad news. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(5-6):792–800. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM, et al. Patient-clinician communication: American society of clinical oncology consensus guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3618–3632. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nestel D, Tierney T. Role-play for medical students learning about communication: guidelines for maximising benefits. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-1187-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jackson VA, Back AL. Teaching communication skills using role-play: an experience-based guide for educators. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:775–780. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wearne S. Role play and medical education. Aust Fam Physician. 2004;33:858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coyle N, Manna R, Shen M, et al. Discussing death, dying, and end-of-life goals of care: a communication skills training module for oncology nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:697–702. doi: 10.1188/15.CJON.697-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Epner DE, Baile WF. Difficult conversations: teaching medical oncology trainees communication skills one hour at a time. Acad Med. 2014;89:578–584. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown B. AFC handbook: worth a look. Community Pract. 2010;83:42–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luttenberger K, Graessel E, Simon C, et al. From board to bedside - training the communication competences of medical students with role plays. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tai J, Molloy E, Haines T, et al. Same-level peer-assisted learning in medical clinical placements: a narrative systematic review. Med Educ. 2016;50:469–484. doi: 10.1111/medu.12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tai JH, Canny BJ, Haines TP, et al. Implementing peer learning in clinical education: a framework to address challenges in the “real world”. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29:162–172. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2016.1247000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Figueiredo MN, Rudolph B, Bylund CL, et al. Erratum to: ComOn coaching: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial to assess the effect of a varied number of coaching sessions on transfer into clinical practice following communication skills training. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:596. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1602-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clayton JM, Adler JL, O'Callaghan A, et al. Intensive communication skills teaching for specialist training in palliative medicine: development and evaluation of an experiential workshop. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:585–591. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wright B, Forbes K. Haematologists’ perceptions of palliative care and specialist palliative care referral: a qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7:39–45. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alexander S, Sullivan M, Back A, et al. Information giving and receiving in hematological malignancy consultations. Psyco-oncology. 2012;21:297–306. doi: 10.1002/pon.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chhabra K, Pollak K, Lee S. Physician communication styles in initial consultation for hematological cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:573–578. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manitta V, Philip J, Cole Sinclair M. Palliative care and the hemato-oncological patient: can we live togheter? A review of the literature. J Pal Med. 2010;13:1021–1025. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roeland E, Ku G. Spanning the canyon between stem cell transplantation and palliative care palliative care in haematological malignancies. Hematology. 2015;2015:484–489. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szekendi MK, Vaughn J, McLaughlin B, et al. Integrating palliative care to promote earlier conversations and to increase the skill and comfort of nonpalliative care clinicians: lessons learned from an interventional field trial. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35:132–137. doi: 10.1177/1049909117696027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Christie D, Glew S. A clinical review of communication training for haematologists and haemato-oncologists: a case of art versus science. Br J Haematol. 2017;178:11–19. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Condron NB, et al. Barriers to quality end-of-life care for patients with blood cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3126–3132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.8177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Epstein AS, Goldberg GR, Meier DE. Palliative care and hematologic oncology: the promise of collaboration. Blood Rev. 2012;26:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bousquet G, Orri M, Winterman S, et al. Breaking bad news in oncology: a metasynthesis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2437–2443. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.6759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verma A, Griffin A, Dacre J, et al. Exploring cultural and linguistic influences on clinical communication skills: a qualitative study of international medical graduates. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:162. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0680-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Turrillas P, Teixeira MJ, Maddocks M. A systematic review of training in symptom management in palliative care within postgraduate medical curriculums. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57:156–170.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The study documentation is collected and managed by the coordinator of the study centre (PC Unit, AUSL – IRCCS di Reggio Emilia), and datasets are available on reasonable request.