Abstract

Adults and children in Canada are not meeting physical activity guidelines nor consuming sufficient nutrient-rich foods. High engagement in these unhealthy behaviours can lead to obesity and its associated diseases. Parent-child interventions aimed at obesity prevention/treatment have assisted families with making positive changes to their nutrition and physical activity behaviours. Given that the home environment shapes early health behaviours, it is important to target both parents and children when addressing diet and physical activity. One method that has been shown to improve health outcomes is co-active coaching. The current study explored the impact of a three-month co-active coaching and/or health education intervention on the dietary intake and physical activity behaviours of parents with overweight/obesity and their children (ages 2.5–10; of any weight). Body composition (i.e., body mass index [BMI] and waist circumference), changes in parental motivation with respect to physical activity and dietary behaviours, and parental perceptions of program improvements were collected. A concurrent mixed methods study comprised of a randomized controlled trial and a descriptive qualitative design was utilized. Fifty parent-child dyads were recruited and randomly assigned to the control (n = 25) or intervention (n = 25) group. Assessments were completed at baseline, mid-intervention (six weeks), post-intervention (three months), and six-month follow-up. A linear mixed effects model was utilized for quantitative analysis. Inductive content analysis was used to extract themes from parent interviews. No significant results were observed over time for the dependent measures. Parents in both control and intervention groups reported varied program experiences, including developing changes in perspective, increased awareness of habits, and heightened accountability for making positive changes in themselves, and consequently, their families. Parents also shared barriers they faced when implementing changes (e.g., time, weather, stress). Qualitatively, both groups reported benefitting from this program, with the intervention group describing salient benefits from engaging in coaching. This research expands on the utility of coaching as a method for behaviour change, when compared to education only, in parents with overweight/obesity and their children.

Keywords: overweight/obesity, parent-child dyad, coaching, physical activity, nutrition, motivation

1. Introduction

If developed during childhood, obesity is likely to persist into adolescence and adulthood [1]. Moreover, children who have parents with overweight/obesity are at a high risk of developing the disease themselves, in that the family environment exerts an important influence on the development of children’s habits [2,3,4]. Given that it is more difficult to change health behaviours later in life, it is crucial to establish healthy habits from a young age [5].

Currently in Canada, 38% of 3–4-year-olds and 61% of 5–17-year-olds are not meeting recommended Canadian 24-h Movement Guidelines for their age groups (>60-min of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA per day [6,7]). In addition, sedentary behaviours are on the rise, with 76% of 3–4-year-olds and 51% of 5–17-year-olds engaging in more screen-viewing time than is recommended in the Canadian 24-h Movement Guidelines for recreational screen-based sedentary behaviours [8]. These age groups spend 2.3 h (5–11 year-olds) and 4.1 h (12- to 17-year-olds) engaged in recreational sedentary behaviours (e.g., watching television, text messaging, video games) per day [8]. The increased time engaged in sedentary behaviours is concerning, in that it takes away from time that could be spent being physically active, and increased sedentary behaviour poses a health risk independent of MVPA levels [8,9]. Regular engagement in physical activity (PA) helps to reduce depressive symptoms and anxiety in children and also enhances their stress responses, resiliency, self-esteem, self-concept, and self-perception [8,9]. In turn, positive functioning in these areas can promote better moods, increase life satisfaction, and minimize negative impacts of stress [10,11,12]. Participating in PA, such as sports, helps to develop positive physical, psychological, and social functioning [10,12]. Children who play sports are more likely to continue engaging in PA into adulthood [13]. Unfortunately, significant declines in sport participation have been reported as children transition into adolescence, with a sharper decline noted in females’ participation rates than males’ at this life stage [13]. If a female has not participated in a sport (organized or individual) by the age of 10, there is only a 10% chance that she will be physically active as an adult [13].

Children whose parents are active are more likely to be active themselves [14]. Surprisingly, only 38% of Canadian parents with 5–17-year-olds report playing active games with them [13]. In addition, parents’ own PA engagement is very important. As noted by Garriguet, Colley, and Bushnik [15], who studied a sample of over 1300 parent-child pairs, every 20-min increase in parental MVPA was associated with 5–10-min increases in the MVPA of their 6–11-year-old children, independent of parental support for PA. Interestingly, only 16% of Canadian adults meet the current guidelines of 150 min of MVPA per week [16].

In addition to their deficits in PA levels, one in five Canadian children (ages 1–8) have energy intakes that exceed their energy needs [17]. Inadequate nutrition in children can lead not only to the development of obesity, and its associated diseases, but also can impact brain development, leading to psychosocial and behavioural problems [18,19,20]. Among Canadian adults aged 19 and over, 50% of women and 70% of men have energy intakes that exceed their needs [21]. Foods that are high in sodium, free sugars (i.e., added sugars), and saturated fat—deemed nutrients of concern—contribute to an increased risk of chronic diseases when consumed in excess [22]. Examples of these foods include cheese, red meat, sugar-sweetened beverages, and pre-packaged meals [22]. In 2017, 58% of all Canadians consumed sodium above the recommended limits, and one in two Canadians consumed higher than recommended levels of saturated fat [22].

As previously outlined, parents and the home environment are key influences on the development of children’s health habits [2,4]. Parents/caregivers can affect children’s eating behaviours by making nutritious food choices for the family, modeling dietary choices and patterns, and using feeding practices to reinforce the development of eating patterns and behaviours [2,4]. Eating behaviour is taught through parental examples; for instance, children’s intake of fruits, vegetables, and milk often increases after observing adults consuming those foods [23,24]. Food parenting practices are strategies parents use to influence the amount and types of foods their children eat [24,25]. Role modeling healthy eating behaviours, involving children in food decisions, and encouraging a balanced and varied diet are feeding practices parents must be made aware of, as those habits have been associated with healthy diets and body mass indices (BMI) in children [25]. Given that parents play a formative role in shaping their children’s health behaviours, it is imperative to provide parents with effective resources and supports aimed at raising awareness and increasing knowledge to enhance healthy behaviours in themselves and their families [25].

Parental motivation to engage in program tasks has been a large determinant of the success of health promotion interventions for parents and their children [3]. Motivation has been conceptualized as an individual’s readiness to change a behaviour—measured as the degree to which the person feels change is important—and their level of confidence in their ability to implement that change [26,27]. In programs targeted at improving obesity-promoting behaviours in children, parental motivation has been significantly associated with: (a) the promotion of healthy behaviours (i.e., dietary and PA changes) in their children, (b) a reduction in child BMI-z, and (c) the successful completion of program tasks by parents [28,29,30,31]. When compared to those with high levels of motivation, parents with low motivation at baseline of family-based behavioural treatment for childhood obesity were less likely to complete the full program [28,32]. Goal-setting and reinforcement intervention strategies have been found to increase parental motivation to change PA behaviour, even in the face of constraints such as time or scheduling difficulties; goal setting may provide busy parents with the additional incentive needed to prioritize their child’s PA over other tasks [33]. Therefore, addressing and facilitating parental motivation to engage in healthy behaviours is important for their and their child’s success in obesity prevention and treatment interventions [28].

In a systematic review of family-based lifestyle interventions for weight loss and weight control in children and adolescents (ages 2–19), Sung-Chan, Sung, Zhao, and Brownson [34] reported that these interventions produced positive effects regarding weight loss in children with overweight/obesity, and that family played an important role in modifying the nutrition and PA behaviours of these children. This finding was supported by ref. [33] in their review of family-based interventions to increase PA in children, in that increases in PA behaviours by one family member prompted others in the same family to engage in activity themselves. Similarly, in an intervention in which parents were asked to track their daily activity using pedometers, and also received weekly telephone calls focused on reflection and encouragement for behaviour change, reported appreciating the reinforcement they received from these weekly calls [32]. The authors hypothesized encouragement received during telephone calls motivated parents to change their children’s PA behaviours, as well as their own. The researchers of the aforementioned review [33] also found that while providing parents with health education was an effective intervention for changing PA knowledge, health education supplemented with reinforcement was more successful in producing behaviour change [33].

One method that has potency in eliciting positive improvements in behaviour change in various areas (e.g., smoking cessation; obesity treatment; mental health; [35,36,37,38]) is Co-Active Life Coaching (CALC; [39]). This primarily telephone-based method is a specific style of life coaching that centers on viewing clients as the expert in their own lives. The coach’s role is to assist the client in deepening their understanding of themselves and/or moving toward meaningful actions of their choosing [39]. This method of coaching allows clients and coaches to work collaboratively, not necessarily to focus on specific behaviours, but on any area of the client’s interest, which often result in behaviour changes. Previous research studies utilizing CALC as an intervention for obesity among adults have demonstrated significant improvement in physical and psychological outcomes [37,38].

Study Purpose

The purpose of this study was to identify the impact of a three-month parent-focused coaching plus health education intervention compared to three-month parent-focused health education only on: (a) the PA levels and dietary intake of children (ages 2.5–10) and their parents with overweight/obesity, (b) parental motivation to engage in healthy behaviours, and (c) parental body composition (i.e., BMI and waist circumference). Parents’ perspectives of how the intervention(s) influenced their own, their children’s, and their family unit’s nutrition and PA behaviours were explored, in addition to their perceptions of what would have made the program more effective for behaviour change.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

Trial registration: ISRCTN ISRCTN69091372. Retrospectively registered 24 September 2018.

A concurrent mixed methods study comprised of a randomized controlled trial and a descriptive qualitative design was utilized as the analytical framework for this study. Utilizing this type of mixed methods research design, in which both qualitative and quantitative data are collected, allows for both types of data to complement and supplement each other [40]. This permitted the researchers to gain a more complete understanding of participants’ experiences, which could not have been obtained by employing only one approach [40].

Parent-child dyads were randomly assigned to either: coaching plus health education (intervention) or health education alone (control). Ethical approval was received from the host institution’s Health Sciences’ Research Ethics Board (ID# 109219). The methods pertaining to the protocol and a complete intervention description have been published elsewhere [41]. However, as the current study progressed some necessary adjustments were made to the protocol. Thus, a brief procedural account is described below.

2.1.1. Participants and Recruitment

Parents were recruited through flyers, Facebook and Twitter posts, Kijiji advertising service site/s, a local radio advertisement, and advertisements in neighborhood and parent-focused magazines. To be eligible for this study, parents/guardians were required to have a BMI of ≥25 kg/m2, live with their child (ages 2.5–10) for at least 5 days/week, speak English, and be comfortable using a computer for data collection. Recruitment and enrollment occurred from August 2017-November 2018. Once a parent-child dyad was determined as eligible to participate, a baseline appointment was made to obtain informed consent, conduct parent measurements, inform the parent of group assignment, and provide the dyad with pedometers. All dyads consisted of one parent and one child; the participating parent received the intervention and/or health education.

The current study employed an active control group, in which participants received health education, as opposed to utilizing a no treatment control. This decision was made on ethical grounds [42], in order to provide parents who wanted to make changes in their and their children’s behaviours with resources that may help them do so. Researchers have reported that health education alone is an effective method to enhance knowledge toward behaviour change [43,44]. Moreover, from a health promotion perspective, providing individuals with knowledge to make healthy choices would allow them to increase control over their own health [45]. Therefore, health education was selected as an appropriate active control condition for this research.

2.1.2. Health Education Modules (Webinars)

Parents in both the control and intervention groups received six evidence-informed (e.g., [6,46,47] online health education (designed to be approximately 20–30 min each) sessions (or webinars) in module format. Three sessions focused on PA and lifestyle behaviours (i.e., benefits of PA, guidelines, sedentary behaviour, sleep, physical literacy, ideas for increasing PA in daily lives of parent and child, and local resources to help increase PA), and three sessions focused on nutrition (i.e., understanding nutrients and nutrition labels, eating with children, positive food environments, barriers to healthy eating, and healthy eating on a budget). Once participants joined the study, the modules were made available on the host university’s eLearning platform. Parents were asked to engage in their next lesson approximately 7–10 days after their previous one.

2.1.3. CALC Plus Health Education Intervention

Parents in this intervention group received CALC in addition to the online health education modules. Participants received nine, 20–30 min, one-on-one, telephone-based coaching sessions (three/month for 3 months) focusing on the agenda of the parent’s choosing. The lead researcher randomly paired parent participants with a Certified Professional Co-Active Coach (CPCC) and together they scheduled their sessions. The parent determined the agenda for each session, and the coach was asked to use only their CPCC skills (e.g., asking genuinely curious open-ended questions, reflecting back what the participant says, acknowledging the participant’s experience, and championing their progress; [39]).

2.1.4. Certified Professional Co-Active Coaches

The CPCC training program is intensive, and requires individuals to first complete two courses on CALC, followed by a 6-month certification program (which runs 3–5 h every week) [48]. In addition, trainees must work with a CPCC for one hour per month. The Co-Active coaching and certification program is accredited by the International Coach Federation (ICF) [48]. Sixteen CPCCs were invited to deliver the intervention; of those invited, 12 agreed to coach in this study. Upon participant enrollment, coaches were assigned one to three parents—based on how many parents each coach identified as suitable for them. Coaches received an honorarium.

2.2. Data Collection

Rolling recruitment was employed, tailoring the data collection periods to each participant. Data were collected at baseline (i.e., 1 week prior to the start of the intervention); mid-intervention (i.e., 6-weeks into the intervention); immediately post-intervention (i.e., 3 months after the intervention began); and finally, at 6 months post-intervention. Parent participants were asked to complete demographic information forms on behalf of themselves and their child at baseline. Both groups completed the same assessments at each follow-up period. The lead researcher and a research assistant conducted baseline and follow-up assessments at either the host university or at the participant’s home. One week prior to follow-up times, an email link was sent to parent participants asking them to complete the questionnaires, and email, text message, and telephone reminders were sent 1 and 2 weeks later if no response was received. If a participant could not be contacted after three consecutive communication attempts, they were contacted again at their next follow-up time, and if no response was received at that point, it was assumed that they were withdrawing from the study. A grocery store gift card was provided to dyads who completed the study.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Pedometer and 24-h Food Recall (Parent and Child)

At each assessment point, parents and children were asked to wear a pedometer for one week (including weekdays and weekends). In addition, parents were asked to track their and their child’s food intake for a full 24-h, in as much detail as possible (e.g., portion sizes, brand). To calculate parent and child nutrient consumption at each time-point, dietary recall records were entered into a food processing computer program (The Food Processor, Nutrition and Fitness Software, ESHA Research, Version 11.3.285, Oregon, United States of America). Trained nutrition students reviewed all food records to ensure accuracy of foods and portion sizes. After consulting with qualified dieticians at the host university, the following nutrient intakes were chosen for analysis in parents and children: protein, fiber, saturated fat, and sodium. Total caloric intake was analyzed in parents only, as it was suggested that this is not an impactful measure in child populations.

2.3.2. Height, Weight, and Waist Circumference (Parent)

The lead researcher and a research assistant conducted parental anthropometric measurements at each assessment time. This consisted of measuring height and weight (to calculate BMI), and waist circumference. Weight was measured using a SECA 803 digital floor scale (SECA, Chino, CA, USA), and height was measured using the SECA 207 mechanical stadiometer (SECA, Chino, CA, USA; at the host institution), or the SECA 217 portable stadiometer (SECA, Chino, CA, USA; for at-home follow-ups). Waist circumference measurements were obtained following Heart and Stroke Foundation [49] guidelines, whereby the measuring tape is placed at the midpoint between the bottom of the ribcage and the iliac crest along the ancillary line.

2.3.3. Standardized and Validated Questionnaires (Parent)

Parents were asked to complete standardized and validated questionnaires at each assessment point, which were available on the online survey software Qualtrics (Provo, Utah, USA). The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ; [50]) is a self-report measure of time spent performing physical activity (in metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes) and time spent sitting during the week. The IPAQ short-form was used in this research. Outlier and truncation instructions were followed. The Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ; [51]) is utilized to assess different forms of motivation as they relate to engaging in PA and a healthy diet. It is comprised of three subscales: (a) amotivation (i.e., absence of motivation; no meaningful relation between what they are doing and themselves); controlled motivation (i.e., behaviour that is performed to obtain a reward or to avoid negative consequences; behaviour performed to avoid feeling guilty; internally controlled but not self-determined); and (c) autonomous motivation (behaviour that is positively valued by the individual; behaviour is perceived as being part of the larger self and connected to other values and behaviours that may or may not be health related; self-determination that underlies behaviours that are engaged in for interest and pleasure from performing them). The TSRQ is measured on a Likert scale of 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true), with higher scores indicating higher motivation [52].

2.3.4. In-Person Interviews (Parent)

To best understand changes in experiences through the duration of this program, semi-structured, one-on-one interviews were conducted with parents at each follow-up assessment. Open-ended questions for the qualitative interviews (Table 1) were derived based on previous coaching studies [53,54], as well as the researchers’ expertise, to garner parents’ perceptions of how the interventions impacted them, their child, and their families, as well as program aspects that would have been more effective in eliciting behaviour change.

Table 1.

Interview Questions.

| - Please give us feedback on this program, positive or negative, about your experiences so far |

| ○ Please elaborate on what has assisted with behaviour change and what has not |

| - What did you like best about the program? |

| ○ What parts of the program did you find most helpful, and why? |

| - What did you not like about the program? |

| - Thinking back to before you started the program compared to now: |

| ○ What impact do you think the program has had on the physical activity behaviours of your child (the one who is registered in the study)? |

| ○ What impact do you think the program has had on your physical activity behaviours? |

| ○ What impact do you think the program has had on the physical activity behaviours of your family, as a whole? |

| ○ What impact do you think the program has had on the dietary intake/nutrition of your child (the one who is registered in the study)? |

| ○ What impact do you think the program has had on your dietary intake/nutrition behaviours? |

| ○ What impact do you think the program has had on the dietary intake/nutrition behaviours of your family, as a whole? |

| ○ What would you say is the most important thing you learned from being in the program? |

| ○ If we were to provide this program again, what recommendations would you have for any changes we should make? |

| ○ What else do you want us to know about your experience with the program and how it has influenced you, your child, and your family? |

Baseline interviews were conducted to understand motivations for joining this study, and because these data fall outside the purpose of this paper, the findings will be presented elsewhere. Qualitative findings included in this paper outline parents’ perceptions of the impact of the program over time on the aforementioned outcomes, and program improvements that would have been more effective for behavior change. Thus, themes from mid-, post-, and 6-months post intervention are presented. The lead researcher conducted the audio-recorded interviews that were transcribed verbatim, and a research assistant also took notes.

2.4. Analysis

Due to high participant drop out, as presented below, and some participants not completing questionnaires at each time point, there was substantial missing data in all data sets. For these reasons, a mixed effects model was considered as the analytic method of choice, as this allows for the use of all available data [55].

A linear mixed effects model was utilized, with group (intervention versus control), and time (baseline, mid-intervention, post-intervention, and 6 month follow-up) entered as fixed effects to explore the impact of the coaching intervention (as compared to education only) on: parent and child step counts and dietary intake; parental BMI and waist circumference; and IPAQ and TSRQ scores. Each of the dependent variables were evaluated within separate models. Per-comparison alpha was adjusted for multiple comparison bias (i.e., when comparing the results to an alpha of 0.01). One participant was a significant outlier, in terms of caloric intake, throughout the study and was removed from the sample prior to data analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.1 [56], with linear mixed effects analyses conducted using the lme4 [57] and lmerTest [58] packages. Post-hoc comparisons amongst the time periods were assessed using the emmeans package [59].

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, and two researchers independently completed inductive content analysis to identify common themes [60]. Strategies employed to uphold data trustworthiness are presented elsewhere [41]. Due to the differences in ‘treatment’ received by control and intervention groups, interviews were analyzed separately at each follow-up time point. Although quotations may be relevant to more than one theme, they are presented in the section in which the quote best fits.

3. Results

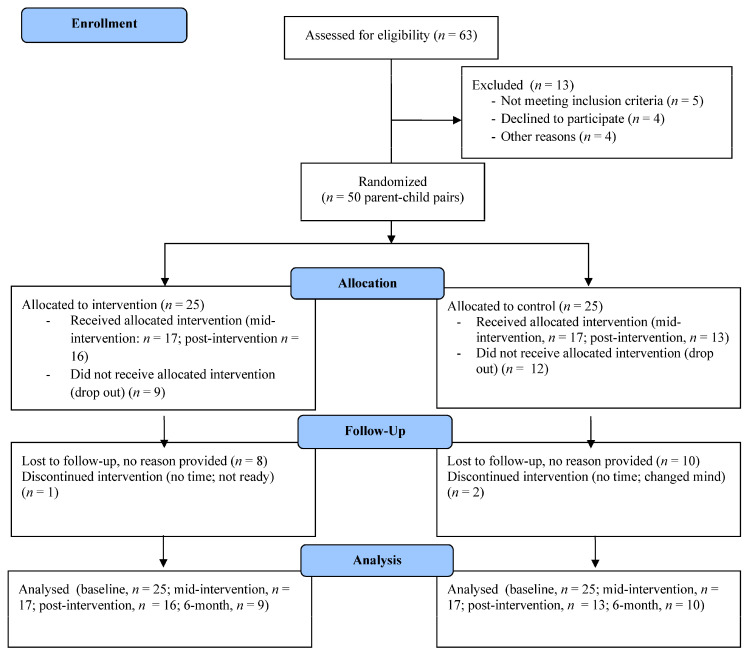

In total, 50 parent-child dyads enrolled in this study; the majority of parents and children were female and the average age was 37 (6.7) years and 6.8 years (2.8), respectively. Demographics for these individuals can be found in Table 2. Due to attrition, all participants did not complete assessments at every follow up time (i.e., six-week, n = 34; post-intervention, n = 29; six-month, n = 19). Site statistics showed that 68% (n = 17) of intervention group parents and 80% (n = 20) of control group parents accessed the health education webinars. For a full outline of retention and attrition, see CONSORT diagram (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Parent-Child Participants.

| Participant Characteristic (Baseline) | N | % | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Sex | ||||

| Male | 3 | 6 | ||

| Female | 47 | 94 | ||

| Parent Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 43 | 86 | ||

| African Canadian | 2 | 4 | ||

| Latin-American | 2 | 4 | ||

| Asian | 1 | 2 | ||

| Other | 2 | 4 | ||

| Parent BMI (kg/m2) | 36.1 | 7.3 | ||

| Parent Waist Circumference (inches) | 44.0 | 5.6 | ||

| Parent Education (Highest level completed) | ||||

| Secondary/High School | 6 | 12 | ||

| College | 20 | 40 | ||

| University | 17 | 34 | ||

| Graduate School | 7 | 14 | ||

| Family Situation | ||||

| Single-parent | 8 | 16 | ||

| Double-parent | 42 | 84 | ||

| Number of people in household | ||||

| 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 12 | 24 | ||

| 4 | 26 | 52 | ||

| 5 | 6 | 12 | ||

| 6 | 5 | 10 | ||

| 7 or more | 1 | 2 | ||

| Annual Household Income | ||||

| Less than $20,000 | 1 | 2 | ||

| $20,000–$39,999 | 7 | 14 | ||

| $40,000–$59,999 | 5 | 10 | ||

| $60,000–$79,999 | 10 | 20 | ||

| $80,000–$99,999 | 4 | 8 | ||

| $100,000–$119,999 | 3 | 6 | ||

| $120,000–$149,999 | 10 | 20 | ||

| >$150,000 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 5 | 10 | ||

| Child Sex | ||||

| Male | 18 | 36 | ||

| Female | 32 | 64 | ||

| Child Age | 6.8 | 2.8 | ||

| Child Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 39 | 78 | ||

| African Canadian | 4 | 8 | ||

| Native/Aboriginal | 1 | 2 | ||

| Latin-American | 2 | 4 | ||

| Asian | 1 | 2 | ||

| Other | 2 | 4 |

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing retention and attrition in current study.

3.1. Quantitative Results

Given that there were only three males, we opted to control for sex effects through the application of homogeneous subset selection (i.e., only female participants were selected for quantitative analysis). Thus, these results should only be generalized to female parents. No participants were deleted from the child data set.

3.1.1. Child PA and Dietary Intake

Results from children’s PA and dietary intake are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Child Nutritional Variables and Step Count for Intervention and Control Groups, at Baseline, Mid-Intervention, Post-Intervention, and 6-Month Follow-Up.

| Intervention Group Baseline | Intervention Group 6-Week | Intervention Group Post | Intervention Group 6-Month | Control Group Baseline | Control Group 6-Week | Control Group Post | Control Group 6-Month | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean steps (SD) | 6830 (1782.55) | 10,371 (6884) | 11,179 (4323) | 9259 (2072) | 11,671 (4264) | 10,741 (3520) | 11,016 (4700) | 10,537 (4981) |

| Protein, g (SD) | 59.5 (17.3) | 64.1 (25.1) | 75.3 (24.2) | 50.2 (10.8) | 75.9 (23.5) | 67.8 (23.4) | 69.7 (20.9) | 71.8 (14.8) |

| Fibre, g (SD) | 17.7 (13.1) | 15.9 (6.5) | 15.6 (3.8) | 15.2 (8.1) | 17.9 (9.2) | 15.9 (7.8) | 17.7 (7.8) | 18.9 (6.1) |

| Saturated Fat, g (SD) | 17.9 (5.5) | 25.7 (14.5) | 17.2 (8.0) | 23.9 (26.0) | 21.4 (8.8) | 16.7 (10.9) | 20.7 (16.6) | 26.5 (16.1) |

| Sodium, mg (SD) | 2204.1 (806.3) | 2467.0 (1498.3) | 2119.9 (608.9) | 2848.1 (1874.7) | 2551.9 (1016.26) | 2306.7 (2113.08) | 2904.1 (2275.6) | 2698.2 (1343.7) |

These included steps per week, protein intake, fiber intake, saturated fat intake, and sodium intake. The main effects model demonstrated no significant difference from the null model over time on: children’s step count, children’s protein intake, children’s fiber intake, children’s saturated fat intake, or children’s sodium intake. The interaction model also demonstrated no significant difference from the null model, suggesting that there was also no effect of the intervention over time on the aforementioned outcomes.

3.1.2. Parent PA, Dietary Intake, and Anthropometric Variables

Parental PA outcomes from each follow-up point are presented in Table 4, including step count (over the course of one week), BMI, waist circumference, IPAQ MET minutes per week, and sitting minutes per day.

Table 4.

Parental PA & Anthropometric Variables for Intervention and Control Groups, at Baseline, Mid-Intervention, Post-Intervention, and 6-Month Follow-Up.

| Intervention Group Baseline | Intervention Group 6-Week | Intervention Group Post | Intervention Group 6-Month | Control Group Baseline | Control Group 6-Week | Control Group Post | Control Group 6-Month | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean steps (SD) | 6381 (1731.8) | 7396 (2531) | 8700 (6053) | 5871(1341) | 6550 (2726) | 6805 (2270) | 7677 (1896) | 10,331 (5021) |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 36.7 (7.6) | 37.3 (8.4) | 36.7 (8.4) | 34.8 (7.8) | 35.8 (7.3) | 36.5 (8.5) | 35.9 (9.6) | 36.8 (8.9) |

| Mean Waist Circumference, inches (SD) | 44.1 (6.2) | 43.5 (6.4) | 43.8 (7.2) | 42.6 (6.9) | 43.7 (5.6) | 43.5 (6.2) | 42.9 (7.1) | 43.9 (6.6) |

| IPAQ MET Mins Per Week (SD) | 1113.6 (1009.6) | 1894.8 (1600.0) | 1603.8 (773.3) | 1436.4 (347.1) | 1948.4 (1451.1) | 2920.2 (2084.5) | 2044.5 (1095.2) | 2394.0 (1497.1) |

| IPAQ Sitting Mins Per Day (SD) | 261.8 (181.3) | 580.0 (1340.8) | 240.0 (144.7) | 285.0 (79.9) | 354.6 (247.8) | 328.9 (210.8) | 326.4 (108.8) | 222.0 (176.8) |

The main effects model demonstrated no significant difference from the null model on parental: BMI, waist circumference, steps per week, IPAQ MET minutes, or IPAQ sitting minutes per day. The interaction model demonstrated no significant difference from the null model, suggesting that there was no effect of the intervention over time on parental: BMI, waist circumference, number of steps per week, or IPAQ sitting minutes per day.

Parental nutritional outcomes from all follow-up points are presented in Table 5, including caloric intake, protein, fiber, saturated fat, and sodium.

Table 5.

Parent Nutritional Variables for Intervention and Control Groups, at Baseline, Mid Intervention, Post Intervention, and 6-Month Follow-Up.

| Intervention Group Baseline | Intervention Group 6-Week | Intervention Group Post | Intervention Group 6-Month | Control Group Baseline | Control Group 6-Week | Control Group Post | Control Group 6-Month | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calories (SD), kcal | 2026.5 (753.3) | 1833.9 (1741.7) | 2012.8 (622.3) | 1810.5 (730.3) | 2256.8 (557.9) | 1884.3 (561.2) | 1741.7 (438.4) | 1660.2 (381.4) |

| Protein (SD), grams | 82.1 (34.8) | 86.6 (34.8) | 107.1 (37.9) | 70.7 (31.9) | 98.1 (37.3) | 94.7 (31.3) | 88.4 (22.9) | 98.9 (33.9) |

| Fibre (SD), grams | 24.1 (18.2) | 24.7 (17.5) | 20.8 (5.7) | 19.5 (7.8) | 22.6 (10.4) | 23.6 (11.1) | 18.6 (9.7) | 17.1 (7.5) |

| Saturated Fat (SD), grams | 24.8 (12.4) | 27.6 (23.2) | 27.4 (14.9) | 30.7 (25.7) | 34.0 (17.1) | 21.9 (12.1) | 33.4 (26.7) | 28.5 (17.7) |

| Sodium (SD), milligrams | 3380.8 (1790.3) | 2670.5 (2000.8) | 2617.9 (1332.0) | 1942.9 (1450.6) | 3659.4 (1713.3) | 2450.2 (1657.7) | 2766.4 (1571.7) | 2468.9 (1737.0) |

The main effects model demonstrated no significant difference from the null model when adjusting for multiple comparison bias (i.e., when comparing the results to an alpha of 0.01) on parental: caloric intake, protein intake, fibre intake, or saturated fat intake. The interaction model also demonstrated no significant difference from the null model on the aforementioned outcomes.

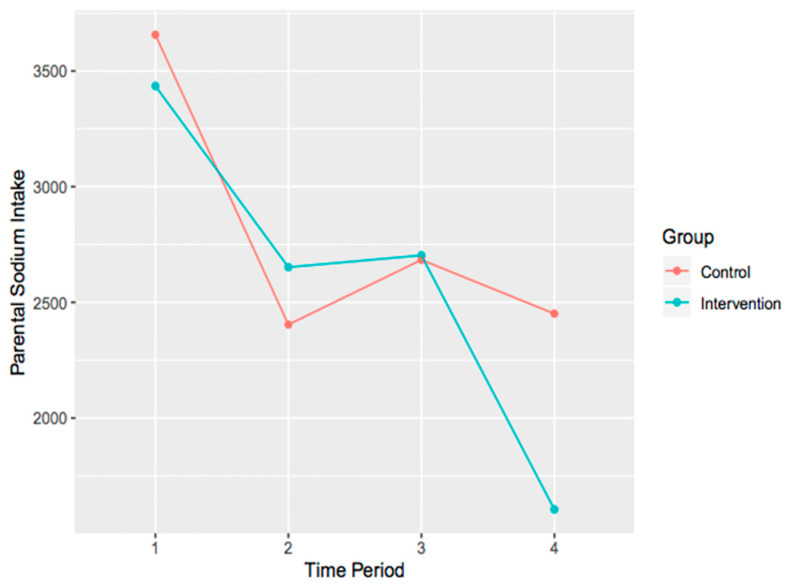

The main effects model demonstrated no significant difference from the null model, χ2 (4) = 13.25, p = 0.01, when adjusting for multiple comparison bias (i.e., when comparing the results to an alpha of 0.01) on parental sodium intake. Similarly, the interaction model demonstrated no significant difference from the null model, χ2 (7) = 15.09, p = 0.04, when adjusting for multiple comparison bias. It is important to note however, the trend that is present within the data (i.e., the effect ‘approached significance’). To explore this, interaction plots were created (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interaction plot of parental changes in sodium intake over time for both control and intervention groups.

3.1.3. Parental Motivation

Parental motivation was assessed using the TSRQ. Outcomes from each follow up time, for diet and exercise, are presented in Table 6. These outcomes included autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, and amotivation.

Table 6.

TSRQ Variables for Intervention and Control Groups, at Baseline, Mid Intervention, Post-Intervention, and 6-Month Follow-Up.

| Intervention Group Baseline | Intervention Group 6-Week | Intervention Group Post | Intervention Group 6-Month | Control Group Baseline | Control Group 6-Week | Control Group Post | Control Group 6-Month | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSRQ Diet, Autonomous Motivation (SD) | 5.9 (1.0) | 5.9 (1.1) | 5.6 (1.2) | 5.6 (1.2) | 6.0 (0.8) | 5.9 (0.8) | 5.7 (0.9) | 6.2 (1.0) |

| TSRQ Diet, Controlled Motivation (SD) | 3.8 (1.3) | 3.9 (1.3) | 4.0 (0.9) | 3.5 (1.6) | 3.7 (1.1) | 4.6 (1.2) | 3.8 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.5) |

| TSRQ Diet, Amotivation (SD) | 2.2 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.0 (0.9) |

| TSRQ Exercise, Autonomous Motivation (SD) | 5.9 (1.3) | 5.8 (1.5) | 5.8 (0.9) | 6.0 (1.0) | 6.0 (1.0) | 5.6 (1.0) | 5.6 (1.1) | 6.0 (1.3) |

| TSRQ Exercise, Controlled Motivation (SD) | 3.5 (1.2) | 3.8 (1.1) | 3.9 (1.3) | 3.6 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.5) | 4.2 (1.2) | 3.8 (1.4) | 3.6 (1.5) |

| TSRQ Exercise, Amotivation (SD) | 2.1 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.6) | 2.9 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.9) | 1.7 (1.0) |

The main effects model demonstrated no significant difference from the null model on: diet autonomous motivation, diet controlled motivation, diet amotivation, exercise autonomous motivation, exercise controlled motivation, or exercise amotivation. The interaction model also demonstrated no significant difference from the null model, suggesting that there is no effect of the intervention over time on the aforementioned outcomes.

3.2. Qualitative Findings

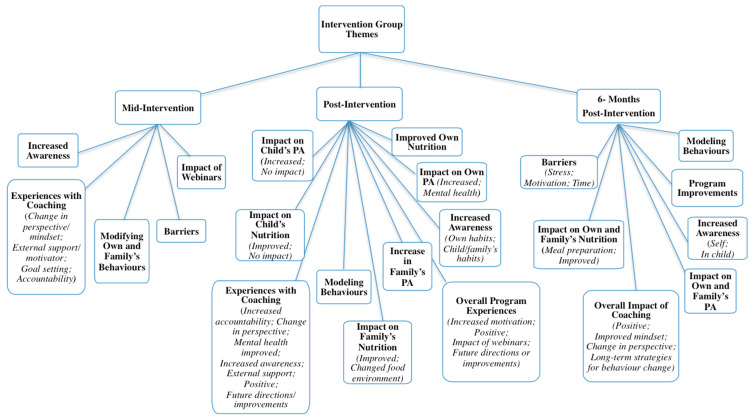

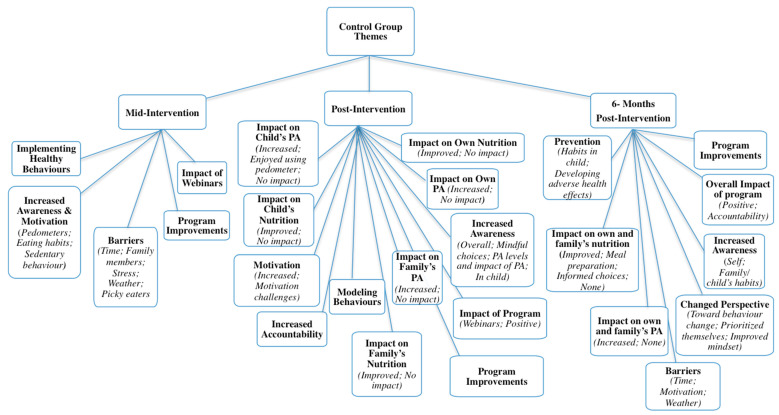

Qualitative interviews with parents resulted in a vast number of supporting statements (Nwords = 13,028, approximately), far more than could be included in the current manuscript. Duration of interviews varied at each follow-up time: 5–41 min (mid); 5–57 min (post); and 6–39 min (six-months). Data saturation was reached for each time point. To avoid repetition, themes and/or subthemes that were unique to each follow-up point are presented and described. For a complete outline of themes, organized by group and follow-up time, see Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Intervention themes from all relevant time points.

Figure 4.

Control themes from all relevant time points.

3.2.1. Mid-Intervention Themes

Intervention group themes. Five themes and four sub-themes were identified from mid-intervention follow-up interviews with intervention group participants (n = 17) with regard to impact of, and experiences in, the program. Corroborative quotations for each theme can be found in Table 7.

Table 7.

Corroborative Quotations for Mid-Intervention Themes and Sub-Themes (Intervention Group).

| Theme: Increased Awareness |

| Quote: “…The coaching aspect has definitely [made] a big difference for me. Because I can read the module, and then for a day I really think about it, or the days where, you know, I have to check the steps, I’m much more conscious of it, of, ‘Okay, I’ve got to do this.’ I want [my children] to be active, you know, I want to be on it. Or when I had to write down my food, I thought about it a lot more.” |

| Theme: Modifying Own and Family Behaviours |

| Quote: “I think that my nutrition’s changing … in the options that I’m picking, ‘cause I have to eat certain amounts of carbs, but it’s trying to make those healthier options of what type of carbohydrates I’m eating. Like, having a piece of bread or vegetable or fruit instead. … Is a much better option than having a bowl of cheezies. … I have to have a snack every night I’ll have a peanut butter sandwich instead of a bowl of chips.” |

| Theme: Impact of Webinars |

| Quote: “The biggest [learning] … that was impactful for me was going into the grocery store and reading the ingredients a little bit more. … You see things like 20 percent or 5 percent, and it didn’t mean anything to me [before completing the webinars].” |

| “I really like some of the tips for handling the issues…with children and eating… The idea of not giving them food when they’re upset… was interesting to me and the way it was described [I] was like, ‘Yeah that makes sense.’ If you feed them when they’re upset then they learn that food just makes them feel good… I can see how that would lead to emotional eating.” |

| Theme: Barriers |

| Quote: “I think over the winter … some of [webinar] ideas will be good, because we’re kind of stuck inside now. … That’s where we kind of get … lazier. So I think just doing different activities inside and stuff will be really good.” |

| “[If] I went to the YMCA that’s closest to me now I’m gone for over an hour to go to a class that’s 30 min. … It’s just a lot to take out of your day when you have two young kids at home.” |

| “So, if you are buying a lot [of healthy food], that adds up. Same with every single fruit. … even the ones that are not organic [are] expensive. The meat went through the roof, certain spices [are] way … too expensive.” |

Experiences with coaching: Most participants in the intervention group expressed that, at the six-week mark, coaching had positively impacted their lives. They described developing changes in their perspectives toward behaviour change; the benefit of having an external supporter or motivator; improvements in goal setting skills; and experiencing increased accountability to themselves and their coaches. For a full explanation of participants’ experiences with coaching, as well as coaches’ perspectives, and corroborative quotations please see ref. [61].

Increased awareness: Parents described an increase in awareness of their and their child’s habits, as well as their reasons for engaging in unhealthy behaviours. Many participants expressed that they turned to unhealthy foods when they were stressed or when they were having a bad day, and some mentioned that the foundation of their unhealthy nutrition habits stemmed from experiences in their childhood. They became more aware of the importance of engaging in self-care, and how focusing on their mindset led to improvements in other areas of their lives. Overall, participants expressed that though coaching sessions did not necessarily centre on nutrition and PA, they realized that improving their mental health resulted in improving their habits and behaviours. In addition, participants became more aware of their and their children’s PA habits through the pedometers. Some parents realized that their children were gaining higher step counts during the week when they were at school or daycare and fewer on the weekends. In addition, they became more aware of their own number of steps taken per day, as well as their levels of sedentary behaviour.

Modifying parental and family behaviours: Participants spoke about changes they made for themselves, and within their households. This included increasing the amount of fruits and vegetables they gave their children, as well as altering the types of foods and snacks they consumed themselves. In addition, participants started to increase their own engagement in PA, via walking, yoga, circuit training, skipping, and going to the gym. In some cases, these activities were done with their children.

Impact of webinars: Parents in the intervention group explained the impact of the educational webinars on their behaviours. Many said that they felt they already knew most of the information that was provided. Others said that they learned new information regarding nutrition labels, percent daily values, physical activities for their children, and about how food should not be used as a reward.

Barriers to behaviour change: Those parents who spoke about barriers explained that barriers prevented them from changing their current behaviours; these included weather, lack of time, and cost. They also felt they didn’t have enough time to exercise, that weather prevented them from being active outdoors, and gym memberships and healthy foods were too expensive.

Control group themes: Five themes and eight subthemes emerged at mid-intervention from interviews with parents in the control group (n = 17) regarding impact of, and experiences in, the program. Corroborative quotations for each theme can be found in Table 8.

Table 8.

Corroborative Quotations for Mid-Intervention Themes and Sub-Themes (Control Group).

| Increased Awareness & Motivation |

|---|

| ● Pedometers |

| “This [pedometer] is addictive. … I’m surprised how many more steps [my daughter] does in a day. … She was at … 16,000 where I was still at [9000].” |

| “My daughter… is talking about [the program] a lot, and was very excited about the step counters, and was …Very excited to be like, ‘Hey, look at how many steps I’ve achieved.’” |

| ● Eating Habits |

| “I have noticed … my daughter… is a lot more active than I am currently, but I have noticed…what we’re eating is starting to affect her. … my bad choices are now affecting the entire family, not just me … [A]ll of the [webinar] videos that were related to the child part of it … she watched with me. … She enjoyed that. But I think for me too, it’s realizing that the choices I’m making are affecting more than just me.” |

| “I have a job … driving around the city all day… [leading to] bad habits of going through drive-thrus… so I am now making more conscious decisions to stop at the grocery store, if I don’t have a lunch … I can just get a salad or something a little more healthier. … [The program has] made me more conscious that way. |

| ● Sedentary Behaviour |

| “[My child] loves YouTube. … So, we’ve always limited …screen time. But it’s interesting, when [the webinar is] saying… one or two hours a day of screen time. You think about how that adds up so fast. … She’s eating her breakfast, she comes home, she watches a little bit. It can easily be an hour, two hours without thinking about it. … So that’s definitely something that… I pay attention to.” |

| Implementing Healthy Behaviours |

| “[My child] can be a little bit of a picky eater, so [prior to joining the program] we would end up just caving into him and giving him whatever he wanted. … So, we cut back on that.” |

| “My husband and I have … got rid of all treats in the house, so when it’s a snack … the only option available is fruit.” |

| “… [I am] parking further away and walking and just trying to get as many steps in as possible.” |

| Impact of Webinars |

| “The program itself has been good information. The videos are good …it wasn’t a lot of things that I didn’t already know. … But, it’s good to … have the reiteration of things that I should know, but don’t follow.” |

| “I read [daily value percentages] now every time I go to a grocery store, I always check the values, I check the fat, I check everything that is not healthy, I try to stay away from that. … [Before] I wouldn’t care about that much.” |

| Barriers |

| ● Time |

| “[L]ife is busy, so… I kind of forgot about the [webinars] and so I have to remind myself to do that.” |

| ● Family members |

| “I find it frustrating sometimes … because my husband doesn’t eat vegetables. … And so, I’ll try to prepare … carrots and make them a bit sweet, or try and … entice [my family] with it. … And my husband will be making a face ‘cause he doesn’t like it and I’m like, ‘Can we not? Just like, don’t influence [the children], right? Or don’t say you don’t like it, can you not just eat one carrot and smile?’” |

| ● Stress |

| “I did start [eating healthy] for quite a while [during the program]. I was doing really well, and then some things changed, and there was a little bit too much stress…then I took a week off, and I realized how easy it is to fall back into bad habits.” |

| ● Weather |

| “But when it is that hot [outside], most people are staying in and kind of hibernating, because it’s too hot to be out, and so we have been trying to get outside every single day, but even if it’s just the backyard, but again, walking from my bedroom to the back door isn’t really a lot of exercise…” |

| ● Picky eaters |

| “I also feel like incorporating [healthy foods] in a way that [kids] don’t know isn’t really teaching them why it’s important [to eat healthy]. … And I also wish they would just give it a chance. Cause like, I make turnips, and I use a little bit of brown sugar, and I know that the oldest would like it, it’s just there’s no chance [my younger child will] even try it.” |

| Program Improvements |

| “I would forget about the online [webinars], just cause it’s online or whatever, maybe … a reminder… every week … Just kind of like touch base and remind you that the videos are on there.” |

| “… I think that extra accountability piece would have made a difference. Whereas, now this is the second time we’re meeting, it’s a couple months in, and… I know I’m accountable but not to the extent … if I was also getting that [coaching] phone call. I would have been, like, ‘Oh my gosh, they’re gonna know even more.’ … Not that I’m hiding anything, but… just having the extra little bit of accountability… would have been better in my situation.” |

Increased awareness and motivation: Parents in the control group explained that the pedometers made them aware of how much daily activity they and their children were acquiring. Many said that their children thoroughly enjoyed tracking steps, particularly because they would compete with their participating parent. Children, according to some parents, felt motivated to gain more steps when they realized that their step count numbers were higher than their parents’. Parents also began to take notice of the amount of screen time in which their children were engaging. Similar to the intervention group, parents in the control group expressed that they were surprised to learn how few steps they acquired on certain days and were also more aware of how much time they spent in sedentary behaviours. It was also shared that the dangers of prolonged bouts of sitting came as a shock to some participants. In addition to heightened awareness of PA habits, participants started to make changes to their and their family’s nutrition. They noticed the types of foods their children were consuming. Some parents explained that their motivation to change stemmed from realizing that their unhealthy habits not only affected themselves, but their families as well. In addition, the impact of modelling behaviours was also realized.

Implementing healthier choices: Parents described changes they started to make for themselves, and in their households. Some explained that they had resisted the temptation to buy fast foods, others said they began introducing more fruits and vegetables into their homes, and some described that they were switching unhealthy food choices for healthier ones (e.g., carbonated water instead of soda pop). Many parents also said that they had removed unhealthy treats from their homes and had decreased sugary snacks from their children’s diets. Some parents noticed the positive impact healthy eating was having on their and their child’s mindset in that they perceived their children as feeling better, having improved concentration, higher energy, and presenting with less agitation. Participants expressed that they had been making a conscious effort to increase their daily PA by bike riding, increasing their walking through parking further away from destinations, or taking the stairs more frequently. Some parents shared the information from the education sessions with their partners and/or families. They began involving their children in cooking and increasing PA with their families (e.g., going for walks together).

Impact of webinars: Similar to those in the intervention group, members of the control group reported that the education sessions were a refresher of information they mostly already knew. They explained that though they knew the information, they found it helpful and appreciated having reminders of what healthy habits entail regarding PA and nutrition. Some parents expressed that they learned new information from the webinars such as reading nutrition labels and differences in serving sizes.

Barriers to behaviour change: Some participants in the control group described that because there was no accountability piece for them and the webinars were self-led, they forgot to continue accessing them. A few participants explained that they had difficulty finding time to complete the webinars because they felt daily life was too hectic. Others spoke about barriers including picky eaters in their families and unsupportive partners who did not want to change their dietary habits. In addition, some parents noted that the weather prevented them from being more active, and that other family members made unhealthy foods too available to their children (e.g., grandparents).

Program improvements: Parents in the control group explained that, while they found the webinar information helpful, they wanted more frequent check-ins with the researchers to serve as support to keep them on track and accountable. A few parents stated that they wanted a more structured program to help them complete the webinars, as they found the self-led format challenging. The desire for assistance with addressing mental health challenges was also expressed.

3.2.2. Post-Intervention Follow-Up Themes

Intervention group themes: Ten themes and 21 sub-themes were identified from immediate post-intervention interviews with intervention group participants (n = 16) with regard to the impact of the program on themselves and their families. Eight of these themes and 12 sub-themes were unique to this follow-up time, and therefore will be described in detail below. Corroborative quotations for each new theme/sub-theme are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Corroborative Quotations for Post-Intervention Themes and Sub-Themes (Intervention Group).

| Impact on Child’s Nutrition |

|---|

| ● Improved |

| “[The program has] had a huge impact on [my child]. [W]e were always … a free feed family …the fridge is open, the cupboards are open, take what you want, when you want. [My son is] nine so what he wanted was cookies, and sugars, and sweets, and starches all the time. [W]e do so much more meal planning now than we ever did. We sit … and figure out the whole week…. [On] ‘eat whatever you want Friday’ … he won’t eat a whole bag of cookies… which makes me happy…. [He says] ‘I ate my sub I’m going to eat an apple first and then I’ll have my cookie.’ … Whereas before he would’ve been like ‘can I have two? … three?’ Both [of] my… children, but definitely my son [program participant], has been [making] significantly better choices.” |

| “[T]wo weeks ago, we went to McDonald’s and [my child] made a comment going ‘Mommy I don’t really like McDonald’s anymore.’ … But he used to want McDonald’s all the time.” |

| “[My child’s nutrition has] changed a lot. She’s looking more at what’s healthy for her, compared to ‘I’m just hungry and bored and wanna eat.’” |

| ● No Impact |

| “We try to eat… a lot of vegetables, and a lot of fruit, and…we’re already trying to do a lot of substitutions with a lot of vegetables, you know, tofu, beans, etc. … We’ve been doing that all along, so nothing’s changed for her.” |

| “I made it a goal even before the program… [to] feed [my child] better than I feed myself. … I made it a goal when she started eating sold food … to make sure that she was introduced to tons of vegetables and fruit, because it wasn’t the same for me growing up.” |

| Impact on Child’s PA |

| ● Increased |

| “[My child’s behaviours] completely [changed since starting the program]. [H]e’s probably watching half as much TV now as he did three months ago… and … [he’s] wanting to go outside, wanting to play games, wanting to explore … anything [to be] outside more… And he was never that kid before.” |

| [My child] sees me moving more. And she wants to participate, so … I did a 100 squat challenge every day for 30 days… and she would join in with me. … it’s acceptable behaviour to her now, to move more and to exercise. [S]he’ll come to me… and [say] ‘it’s time for exercise.’” |

| “[Before the program my child] was signed up for nothing, and now she’s signed up for 3 things. … So she’s doing karate, yoga, and skating.” |

| ● No Impact |

| “[My child] was super active before we started [the program] and she’s still really active today. … I think the only thing that I’ve changed is that.… I’m going to be enrolling her in some more programs for exercise and things like that.” |

| Improved Own Nutrition |

| “I’ve been… more purposeful to make extras for dinner because that’s one of the healthier meals that we eat [because] we eat as a family. … So I’ll make sure I’ll have enough leftovers for… myself for lunch, versus eating a small bowl of chips.” |

| “Grocery shopping has just changed. [I stick] to the outside perimeter of the grocery store versus going deep into the aisles. … [And when I’m] making muffins… I’ll just throw the carrots in. … I’m sure it’s not even a lot, but again, it’s changing the flavour, texture, getting the taste buds more used to having the sweetness of the carrot and the pineapple in the muffin instead of the sweetness of chocolate.” |

| “The program has definitely [had] a positive impact [on my dietary intake]. … I still struggle with stuff like eating enough fruits and vegetables. … My major goal when I was working with the coach was my sugar intake, that’s what we ended up focusing on. … I realized the other day that my coffee was too sweet and I reduced how much sugar was in it by one teaspoon and then it tasted so much better. I’m losing my taste for sugar for a little bit.” |

| Impact on Own PA |

| ● Increased |

| “I think [what] the program did for me was [help me] understand how important my routine was and how much of an impact it was having on my life. So…the last four weeks I’m up early and working out, I’m making breakfast for my family before I get to work instead of rolling out and [saying] ‘we’re grabbing [fast food] today.’ [Before] I would be like ‘here’s a donut, here’s a cupcake. … And I think if I hadn’t gone through the program, I think I’d still be that way.” |

| “I’m doing more practical activity … like raking and shoveling and playing, skating, skipping, that kind of stuff. It’s not that I’m going to the gym, ‘cause I’ll never be a gym person, is what I have learned over the years. … But [the program] has just spurred me to try and be more active so, it’s … in the back of my mind all the time.” |

| “[Because my job involves a lot of sitting] I can’t incorporate a lot of walking, but I did start… parking further, in parking lots. …[When] sit[ting] in client meetings all day …started standing up, even between the meetings, and I started stretching a little bit more instead of just sitting at the desk and waiting for the next client to come.” |

| ● Mental health |

| “[My coach and I] were talking about how when I’m feeling stuck, like literally just getting up and moving your body, can snap you out of a funk.” |

| Impact on Family’s Nutrition |

| ● Improved |

| “We’re eating healthier because we are following our meal plan, we’re pre-planning our meals so we know what we have in the house and that we make sure we have enough for the rest of the week because I don’t want to go to the grocery store four-five times a week, now it might be twice.” |

| “I’ll just buy one of those vegetable trays from the grocery store and just put it out and [my children] eat it!” |

| “All the kids [love salads now]. One night… was a huge success, half [my son’s] plate was just salad, just naked veggies. … And before [the program], I don’t think that they would have been.” |

| ● Changed food environment |

| “I think [my family] feel[s] like they’re getting a little bit more of a choice [of foods] now. Like if I call home and say we’re having this and this and this, [my children will] say like ‘oh can we have the green beans instead of that?’… [I say] ‘sure, we can switch those.’ …. [I]f I come home and I… need to then cook and then we eat, its 6:30–7:00. Whereas if [my family members] help, I get home, we eat, and then we can spend time together.” |

| “I now go through two bags of apples a week… and two bundles of bananas. … [Before], my bananas would just kind of rot, and then I’d make banana bread.” |

| “[We have been looking for] different [food] options. Like, the kids are even saying, ‘well, that’s not a good option, Mom. Let’s do this one.’ … So, having them buy into it is much easier. … And it’s just more of a conversation we have [about healthy eating], versus mom just plops stuff in front of them.” |

| Increase in Family’s PA |

| “We’ve been skating, we do skipping, and we were out raking yesterday. So [the program] pushes me…to try and do something everyday. Whereas before there were days where… I would come home and just be too tired and we wouldn’t do much at all.” |

| “[Physical activity is] easier because now …on days when I don’t feel like doing [physical activity], [my husband will] say … ‘okay, are we going to go on a walk with the dog tonight’ or ‘we’re going to take kids to the park, and on days where he doesn’t feel like doing it, then I’m the one pushing him. Whereas before it was both of us …watch[ing] TV.’” |

| “Friday nights [used to be] pizza and a movie nights. … And chips. …[V]ersus [now it is family] gym night. … Like, that’s a big change.” |

| Modeling Behaviours |

| “[The program is a] reminder that everything I do in my life, my children are watching me. So whatever I’m doing that I am a model for them. So if I’m modeling very lazy lethargic behaviour, watching TV all the time, not keeping active in my lifestyle, that’s what my kids are going to… think is okay and it’s going to trickle down because that’s what my parents were like. …[A]nd it trickled down into my life and I want to stop that now. I want my children to see what a healthy [life]style looks like.” |

| “I’m being accountable for what [my children are] putting in their bodies. … I knew what I was buying wasn’t the healthiest for them, but it was something that they like. So, I was [starting] to realize ‘okay, well just because it was something they like it doesn’t mean that they need to indulge in that.’” |

| Overall Program Experiences |

| ● Increased motivation |

| “[The program] helped me to get the first step to being motivated to doing something … literally just moving.” |

| ● Positive |

| “I loved the fact that you guys come to the house [for follow-ups]. [Because] … I’ve got a kid, so … getting out of the house is a whole production.” |

| “[The program] was just nice and… an overall reminder just to focus, slow down, look at what it is that we’re doing, and in my case, it was good to reinforce that … we’re doing the right things. …[Y]ou get so stuck in your routine … that you don’t slow down to actually look at what it is that you’re doing, and why, and is it working. So it was kind of nice to have a little bit of a review.” |

| ● Future directions or improvements |

| “I thought it was a really great program… I guess maybe if I was to say anything it would be to like give two different options to people [for the education sessions]… of being flexible, versus having … deadlines and check points. My personality is that I will either try and … rush through it at the start or … do it at the very end, but if there’s deadlines I’m always committed to meeting my deadlines.” |

| “I think there are so many more people [who] could benefit from the program …. [T]he program is so impactful for me that I think… it should be offered to every kid in school. [I]f their parents don’t take it, they don’t take it, but this sort of stuff needs to be taught more in our school at a younger age.” |

| “The only recommendation was to do the webinars… an audio version of them.” |

Impact on child’s nutrition: Most parents explained that they felt their children’s dietary intake had improved over the course of the program. Due to meal planning and making healthier foods more available in their homes, their children were making better nutritional choices than before the program. Parents reflected that their children’s preferences seemed to change in that instead of craving convenience or fast foods, they were more likely to select a fruit or vegetable when they wanted a snack. They explained that, before the intervention, their children enjoyed and craved fast foods and sugary snacks. Conversely, some parents felt that their children already had well-balanced diets. Parents explained that they tried to ensure their child’s habits were healthier than their own and had always made healthy food available in their homes. These parents they felt the program did not impact their child’s dietary intake.

Impact on child’s PA: Intervention group parents’ perceptions of their children’s PA levels varied; some felt levels increased while others felt there was no change. Some parents reported that children who observed their parents becoming more active began to increase their own activity as well. Parents explained that because they felt accountable for their child’s PA levels, they encouraged their child to be active, and became more cognizant of their child’s activity levels. Through increasing their daily PA, children engaged in less sedentary behaviour (such as watching television) and spent more time playing outside. A few parents noted that this was a vast change compared to before the program in that their children tended to be sedentary after school and/or their extra-curricular activities. Parents also noted that their children enjoyed using the pedometers; they sensed that using pedometers encouraged higher step counts in their children. Parents felt that, from this increase in PA, their children were also motivated to join other sporting activities. Some parents felt that because their child was already active, and remained so throughout the program, their PA levels did not change. Parents opined that because their children were very active during the days, whether through daily PA or structured activities, increases in their PA due to the program were unlikely.

Improved own nutrition habits: All parents in the intervention group felt that the program made at least some impact on their dietary intake and helped them improve their nutrition behaviours. They explained that instead of choosing quick and convenient foods, as they would have done before the program, they were more likely to choose healthier foods. They became cognizant about the choices they made and implemented what they felt were manageable changes. Parents explained that meal planning and preparation helped them with making the healthier choice more convenient in that these foods were now readily available in their homes. Moreover, in making small changes in their diets, participants found their food preferences changed over the course of the program (e.g., craving less sugar).

Impact on own PA: Some parents in the intervention group noted substantial improvements in their PA levels through their involvement in the program. Participants shared that they incorporated PA into their days such that PA became a part of their routine. For instance, they would take stretch breaks at work, or, if they could not be active outdoors, they would find indoor spaces where they could walk. Parents reported that they started to walk more in general, engaged in activities such as skipping or skating, or conducted their own exercises in their homes. As a result of engaging in higher PA levels, parents noticed that they also experienced more positive mental health than before their involvement in the program. Parents explained that the changes that they implemented became established habits for them, and that these changes translated to them feeling more positively about other aspects of their lives.

Impact on family nutrition: It was reported that intervention group families’ nutrition behaviours improved through parents’ involvement in this program. Parents shared that their family planned for and made meals together thereby motivating their family not only to eat healthier, but also understand the importance of doing so. Parents explained that, because their family changed their diets together, they were more likely to engage in healthy eating due to the support they felt from each other. They noted that their children’s preferences for unhealthy snacks began to change, and they started to request fruits and vegetables. In addition, parents shared that their children who were not participating in the study also changed their diets and began to seek out healthy food options. Parents described that they continued to change their home food environments by ensuring their homes no longer had convenience or junk foods. They no longer bought fast food or snacks that were high in sugars or fats (e.g., granola bars); instead, they made fruits and vegetables more readily available in their homes.

Increase in family PA: Intervention group parents shared that because they began to increase their own PA levels, their family did the same. They explained that their involvement in the program helped them make PA a priority for them and their families. They started to engage in PA together, which soon became part of their routine. Some families went for walks together, whereas others set designated times to be physically active together. Parents noted that this increase in family PA was a drastic change from their previous habits in that they and their families would have been engaging in more sedentary behaviours prior to participating in the program.

Modeling behaviours: Participating parents in the intervention group shared that the program helped them realize the extent to which their behaviours impact their whole family’s behaviours. Parents explained that when they changed their behaviours, their children noticed, and did the same. Parents also felt it was important to establish healthy behaviours to ensure that their children developed healthy habits which would be more likely to continue over their lifetime. Parents reflected that they did not realize the extent to which their children observed their parents’ behaviours, and through the webinars and coaching program, parents were able to make changes that benefitted themselves and their families.

Overall program experiences: Parents described that through the intervention program they increased their motivation to engage in healthy behaviours, felt the program was positive overall, explained the impact of the webinars, and also provided their feedback regarding future directions and improvements. Children and families began to increase PA levels and improve dietary intake upon observing these behaviours being implemented by participating parents, thereby further motivating parents to continue improving their habits. In general, parents felt the program was a positive experience and provided the momentum they needed to institute and maintain healthy behaviours. Most liked the format of the program (i.e., telephone sessions and at-home follow-ups), and others were pleased to observe positive impacts on their children’s health behaviours. Some parents felt the education sessions provided them with some new information, while others felt they served as reminders of health information they already knew. Participants suggested providing printed copies of the webinars, using a different site to host the webinars, and more structured deadlines for webinar completion dates. In addition, it was suggested that the program be offered in schools, and because of their positive experiences with coaching, parents recommended that all participants in the program should have the opportunity to work with a coach.

Control group themes: Twelve themes, and 21 sub-themes, emerged from post-intervention interviews with parents in the control group (n = 13) regarding the impact of the program on themselves and their families. Nine themes and 16 sub-themes were unique to this follow-up time, and therefore are discussed in detail. Corroborative quotations for each new theme/sub-theme can be found in Table 10.

Table 10.

Corroborative Quotations for Post-Intervention Themes and Sub-Themes (Control Group).

| Increased Awareness |

|---|

| “[My child and I] talked about healthy [eating], like she always knew what a healthy versus unhealthy food was, but like when [she’s] five and there’s a bag of chips and apple I mean obviously she is going to choose that. So I find now that she is more likely to go and choose one of her healthy snacks without me having to remind her.” |

| Impact on Child’s Nutrition |

| ● Improved |

| “We are hard on fast food now. …instead of just eating fries or cheese pizza [at the mall] she would go and get white rice, broccoli, or like shrimp. …[E]ven though some of that stuff’s not…made the best, at least I know … that stuff is going to fill her up [better] than the other stuff.” |

| “Even getting [my child] things like a protein bar right, because at least that’s better than eating a chocolate bar. … So, we would buy something that was a little… healthier on the go, because he’s usually running out the door in the mornings. … And, [I am] buying the … cut fruits and vegetables so that it is already ready for him to grab….” |

| “[My child has] always been a pretty good fruit eater. But we tried to introduce new foods, expand the repertoire… some vegetables, some protein. … [He is] eating carrots now, celery… we tried some beans, black beans and kidney beans. … Scrambled eggs.” |

| ● No Impact |

| “I don’t think [nutrition] necessarily changed for [my child]. It wasn’t necessarily the dietary stuff, for her. … There’s never been a lack of healthy options in the home.” |

| Impact on Child’s PA |

| ● Increased |

| “[Before the program my children would] come home… get a freezie or … a pack of gummies, and they would just sit. … Most of the time my oldest would always fall asleep then she would complain of headaches, so this summer… she wasn’t the one steady participating [in this program] per se but she picked up off of the younger one [who was participating]. [T]he younger one … now …[has] a routine, it’s normal for her. So now if she’s watching TV too long, she gets fidgety. … It’s almost like her body’s telling her like you need to get up and do something … She’s like ‘okay, I’m going to go play’ … [the older child is] getting better, too.” |

| “We definitely are more active now. … Like [my child] snowboards now, he plays hockey, so I volunteer on their hockey team. …. Before [the program] I’d put him in maybe one sport, but now I’m … trying to get him to do more. … So I’ll be taking him more often because it’s really important… it’s fun and we can be active and spend time together.” |

| ● Enjoyed using pedometer |

| “I do think [my child] tried to get more steps in with that pedometer. She’d be sitting still and then stand up and walk around and then look at the pedometer and stand up and look at the [step count]. And I would remind her, ‘It’s supposed to be honest, so when you’re walking… you don’t need to do extra steps.’ But, I suppose it is nice that she did get excited by it, and I couldn’t squash that, it was great.” |

| “[My child] was very conscious of [step counting], and of course he liked [it] because he got more steps the days he played soccer… he was into it.” |

| ● No impact |

| “I don’t think [my child’s PA was] really impacted that much. I think… out of the two of us, [my child is] far healthier than I am. Probably because I realize how unhealthy I can be, and want to make sure I’m not instilling those bad habits into her. So I think for her, it was … repetitive information. … She listened to what I had to say, she watched a few videos with me, whenever it was directed towards the child portion, and then just went on her way. I don’t think it really made a significant difference… she’s always active.” |

| Impact on Own Nutrition |

| ● Improved |

| “[Now] I [have] been like ‘nope, I don’t need to get those chips.’” |

| “When I have one carrot, or two, you know, just leftover vegetables… I just puree them…freeze it, and then I use it in my pasta sauce.” |

| “[I]ts not that I don’t like vegetables, it’s that… I find them like boring, and so … I try to make [healthy food] fun for me, too. But… [also trying to stay] away from … bad fats and everything like that.” |

| “[The program helped with me] knowing if I do want a snack, I don’t need the whole bag… [of] chips …. [N]ow, I put some in … a little kid bowl. … [I]f I eat a bag of chips with 1100 calories, that’s more than half of what I should be eating in a day… and I’m still hungry,’ so that was like a big ‘what did you just put in your body’ [realization].” |

| ● No Impact |

| “I wouldn’t say that my eating habits improved all that much but definitely I’m more aware of it.” |

| Impact on Own PA |

| ● Increased |

| “I play baseball during the summer, …I signed up for yoga, which I’ve always been intimidated by. … [I also have been] going to [the gym at work] after work, and now… I park further away so I walk 15 min to work, and 15 min from work.” |

| “I started a new job in the Fall. … And I’ve got my office on the sixth floor and I have stuff to do on the ninth floor and first floor and second floor; so I’m taking the stairs as much as I can.” |

| “Because my son is more active, I’m more active, I don’t just sit around all day. I’m …going out and doing sports with him …before I would probably never. I mean I would have but like it’s a drag. … I still find it exhausting, but I much rather go out and do things with him if it makes him happy.” |

| ● No impact |

| “When I did the first surveys and read the modules, I had a plan, well not exactly a plan, a thought that I would increase my walking, kind of throughout my work day, like take regular walk breaks. … But it just, it hasn’t happened.” |

| “I can’t seem to find time in the days … the days are just so busy, it’s hard to kind of find a time. I mentioned it to a colleague also, who said she would be interested in going walking… but we have never found a time that we’re both free to do that…which is depressing.” |

| Impact on Family’s PA |

| ● Increased |

| “I think [we have] increased physical activity… heading down to the park after school or going for a walk, [because] … it’s really easy sometimes when you’ve had a really long day…to say ‘No we’re just going to stay in.’ But if [my child is] asking to go on a walk, nine out of ten times we’re going to say yes. … We’ll take her to the park, or go for a rollerblade, or whatever it is she wants to do. … So just being more active as a family… more frequently.” |