Abstract

Centromeres are built on repetitive DNA sequences (CenDNA) and a specific chromatin enriched with the histone H3 variant CENP‐A, the epigenetic mark that identifies centromere position. Here, we interrogate the importance of CenDNA in centromere specification by developing a system to rapidly remove and reactivate CENP‐A (CENP‐AOFF/ON). Using this system, we define the temporal cascade of events necessary to maintain centromere position. We unveil that CENP‐B bound to CenDNA provides memory for maintenance on human centromeres by promoting de novo CENP‐A deposition. Indeed, lack of CENP‐B favors neocentromere formation under selective pressure. Occasionally, CENP‐B triggers centromere re‐activation initiated by CENP‐C, but not CENP‐A, recruitment at both ectopic and native centromeres. This is then sufficient to initiate the CENP‐A‐based epigenetic loop. Finally, we identify a population of CENP‐A‐negative, CENP‐B/C‐positive resting CD4+ T cells capable to re‐express and reassembles CENP‐A upon cell cycle entry, demonstrating the physiological importance of the genetic memory.

Keywords: CENP‐A, CENP‐B, centromere, chromatin, chromosome segregation

Subject Categories: Cell Cycle; Chromatin, Epigenetics, Genomics & Functional Genomics

Rapid removal and reactivation of CENP‐A defines the temporal cascade of events necessary to maintain centromere position, with DNA‐bound CENP‐B providing memory and preventing movement of centromere position.

Introduction

Proper transmission of genetic information at each cell division is vital to healthy development and survival. Centromeres are key in maintaining a correct karyotype. In monocentric species, abnormalities in their number or integrity lead to mitotic defects (Barra & Fachinetti, 2018). Thus, cells must preserve a unique centromere per chromosome to prevent the emergence of genomic instability. In most species including humans, this is achieved via a robust epigenetic self‐assembly loop that ensures the replenishment of centromeric proteins at the same location for an indefinite number of cell cycles (McKinley & Cheeseman, 2016).

The most striking evidence that centromere position is epigenetically identified derives from the discovery of stably inherited neocentromeres in human patients (Voullaire et al, 1993). In these cases, a centromere has been formed on an ectopic position along the chromosome arm at non‐centromeric DNA sequences. Except rare cases, human neocentromeres are associated with chromosomal rearrangements, entailing the partial or total excision of the original centromeric DNA (CenDNA), and are found in developmental diseases and some types of tumors (Marshall et al, 2008).

In the last two decades, many reports have converged toward the evidence that in most species, the CENtromere Protein A (CENP‐A), a specialized histone H3 variant enriched at centromeric regions (Earnshaw & Rothfield, 1985; Palmer et al, 1987), is the centromeric epigenetic mark (Fukagawa & Earnshaw, 2014). Through a tight regulatory process (Zasadzińska & Foltz, 2017), CENP‐A maintains centromere position via a two‐step mechanism (Fachinetti et al, 2013). First, at mitotic exit CENP‐A self‐directs its assembly (template model) to maintain its centromere localization (Jansen et al, 2007) via the CENP‐A Targeting Domain (CATD) (Black et al, 2004, 2007; Foltz et al, 2009; Bassett et al, 2012), at which new CENP‐A molecules are assembled adjacent to the existing ones (Ross et al, 2016). Subsequently, CENP‐A promotes the assembly of several centromeric components, collectively named the Constitutive Centromere‐Associated Network (CCAN) complex (Foltz et al, 2006; Hori et al, 2008; Weir et al, 2016; Pesenti et al, 2018), mostly via a direct interaction with CENP‐C and CENP‐N (Carroll et al, 2009, 2010; Guse et al, 2011; Kato et al, 2013). In turn, the CCAN complex is required to assemble the kinetochore (Musacchio & Desai, 2017).

In vertebrates, CENP‐A incorporation into chromatin is mediated by a specific chaperone, HJURP (Dunleavy et al, 2009; Foltz et al, 2009; Bernad et al, 2011) that forms a complex with acetylated histone H4 (Sullivan & Karpen, 2004; Bailey et al, 2016; Shang et al, 2016). The HJURP/CENP‐A/H4 complex is directed to the centromere via the Mis18 complex (Barnhart et al, 2011; Wang et al, 2014; Nardi et al, 2016; Pan et al, 2019), an octameric protein complex (M18BP1 and Mis18α/β subunit) that licenses new CENP‐A deposition (Moree et al, 2011; Dambacher et al, 2012). How the Mis18 complex recognizes centromeres is still a matter of investigation, but M18BP1 and Mis18β were shown to interact with the C‐terminal domain of CENP‐C (Moree et al, 2011; Dambacher et al, 2012; Stellfox et al, 2016; Pan et al, 2017) or directly with CENP‐A in both chicken (Hori et al, 2017) and frogs (French et al, 2017) (although the residue involved in this interaction is missing in humans). Polo‐like kinase 1 (PLK‐1) and cyclin‐dependent kinases (CDK) 1 and 2 ensure the cell cycle regulation of both HJURP and Mis18 complex (Silva et al, 2012; McKinley & Cheeseman, 2014; Müller et al, 2014; Stankovic et al, 2016; Pan et al, 2017).

Despite the strong indication that the self‐assembly loop mediated by CENP‐A uniquely defines centromere position, native human centromeres are always associated with long stretches of repetitive tandemly arranged DNA sequences named alpha satellites (Allshire & Karpen, 2008). Intriguingly, in mammals, fission yeast, and insects, these tandem repeats acquired, over evolution, a DNA sequence‐specific binding protein (CENP‐B or CENP‐B‐related proteins) (Gamba & Fachinetti, 2020). In humans, CENP‐B binds to a specific motif named CENP‐B box that is present within the alpha‐satellite unit at all centromeres, except the Y chromosome (Earnshaw et al, 1989; Miga et al, 2014). Why centromeres are built over tandem repeats and why CENP‐B evolved to bind CenDNA, although it is not present in all organisms, are still open questions.

The role of CENP‐B and repetitive DNA at centromeres has puzzled researchers for years. On the one hand, CENP‐B appears to be non‐essential since it is absent from the Y centromere (Earnshaw et al, 1989) and from stably inherited neocentromeres (Voullaire et al, 1993), and CENP‐B knock‐out mice are viable (Hudson et al, 1998; Kapoor et al, 1998; Perez‐Castro et al, 1998). Conversely, we showed that CENP‐B bound to CenDNA is important to maintain chromosome segregation fidelity (Fachinetti et al, 2015; Hoffmann et al, 2016) by counteracting chromosome‐specific aneuploidy during mitosis (Dumont et al, 2020). Beside their active role in chromosome segregation, CenDNA and CENP‐B were also implicated in favoring the establishment of functional human artificial chromosomes (HACs) (Ohzeki et al, 2002; Okada et al, 2007), possibly by recruiting CENP‐A directly via the CENP‐B amino‐terminal tail (Fujita et al, 2015). However, recently, Logsdon et al described that HAC formation is not strictly dependent on alpha‐satellite sequences or CENP‐B (Logsdon et al, 2019). Interestingly, in half of the cases of α‐satellite‐free HAC formation, centromeric DNA was acquired within their sequence, somewhat supporting a role for CenDNA during mini‐chromosome formation.

Hence, whether CENP‐B and the underlying CenDNA are required for de novo centromere formation of naturally occurring human centromeres and/or if they contribute to centromere identity remains elusive.

Here, we explore the importance of repetitive DNA sequences in centromere specification at native human centromeres by generating an inducible depletion and re‐activation system of the centromeric epigenetic mark CENP‐A. With this unique approach, we reveal the order of events necessary to maintain centromere position in human cells. We uncover the importance of CENP‐B binding to CenDNA in centromere specification at native human centromeres by preserving a critical level of CENP‐C necessary to promote de novo CENP‐A assembly. Our work has both physiological and pathological implications as demonstrated by the existence of CENP‐A‐negative resting CD4+ T lymphocytes capable to re‐enter in the cell cycle and the formation of neocentromeres in a CENP‐B‐negative chromosome, respectively.

Results

Previously deposited CENP‐A is not essential for new CENP‐A deposition at endogenous centromeres

CENP‐A is well known to maintain centromere position via an epigenetic self‐assembly loop (McKinley & Cheeseman, 2016). This suggests that at least a pool of CENP‐A must always be maintained at the centromere to mediate new CENP‐A deposition. Here, we sought to challenge this concept and test if previously deposited centromeric CENP‐A is required to license new CENP‐A deposition at the native centromere position. To this aim, we used a two‐step assay (hereafter referred to as CENP‐AOFF/ON system) that allows us, in a first step, to deplete endogenous CENP‐A and, subsequently, to re‐express it (Fig 1A). To generate this unique tool/model, we took advantage of the reversibility of the auxin‐inducible degron (AID) system that allows rapid protein depletion and re‐accumulation following synthetic auxin (indol‐3‐acetic acid, IAA) treatment and wash‐out (WO), respectively (Nishimura et al, 2009; Holland et al, 2012; Hoffmann & Fachinetti, 2018). By combining genome editing with the AID tagging system, we previously showed our ability to rapidly and completely remove endogenous CENP‐A from human centromeres with a half‐life of about 15 min (Hoffmann et al, 2016), with only a small percentage of cells that remain unaffected by the IAA treatment (Fig EV1A). Following IAA WO, endogenous CENP‐AEYFP‐AID (hereafter referred to as CENP‐AEA) is rapidly (within 1–2 h) re‐expressed at detectable level as observed by immunoblot (Fig 1B). The rapid CENP‐A re‐accumulation could be explained by the continuous presence of mRNA CENP‐A transcripts despite the immediate protein degradation in the presence of IAA. Hence, the generated CENP‐AOFF/ON system provides a powerful tool to test CENP‐A reloading in the absence of previously deposited CENP‐A.

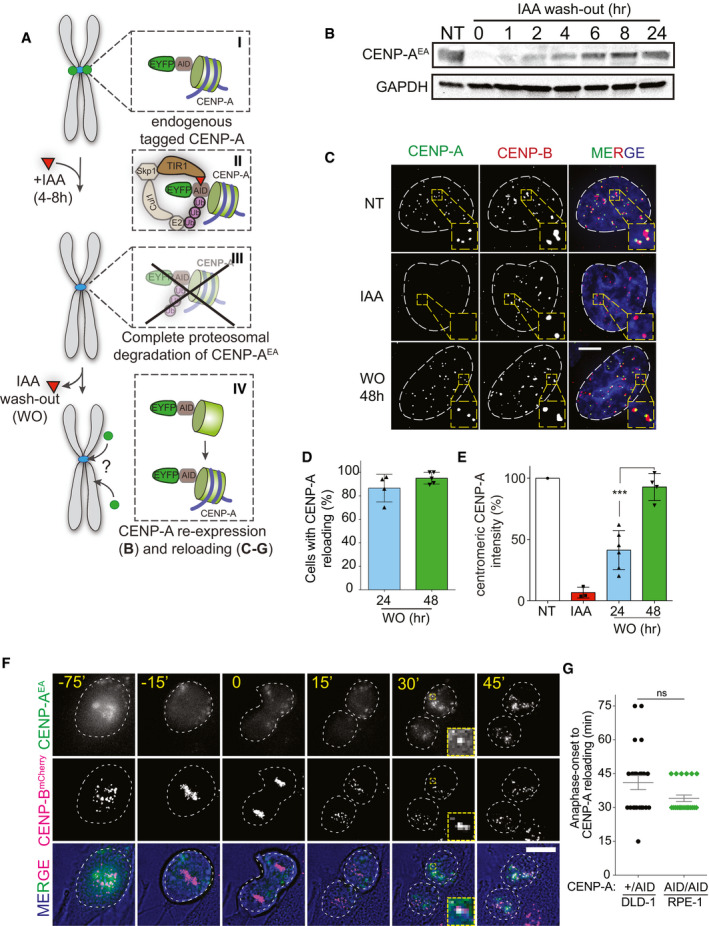

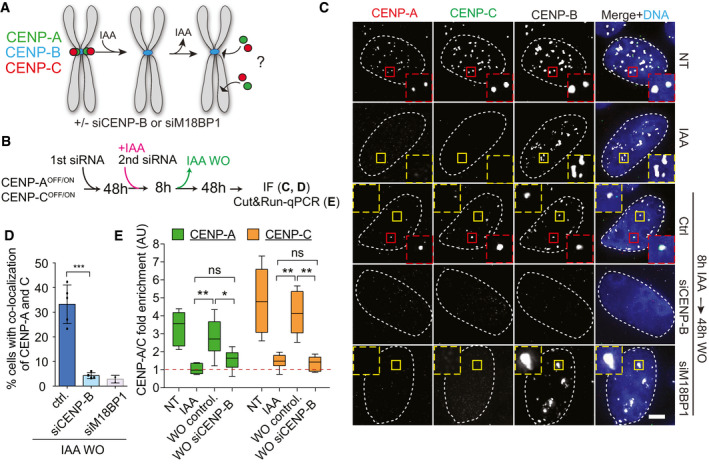

Figure 1. The CENP‐A epigenetic self‐assembly mechanism is not required for de novo CENP‐A deposition at native human centromere.

- Schematic illustration of the two‐step CENP‐AOFF/ON assay using the auxin (IAA) inducible degradation system.

- Immunoblot showing CENP‐AEA protein level at the indicated time in RPE‐1 cells.

- Representative immunofluorescence images showing CENP‐A reloading at CENP‐B-marked centromeres. White dashed circles contour nuclei. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Quantification of the percentage of cells showing centromeric CENP‐A 24 or 48 h after IAA WO. Each dot represents one experiment (˜30–50 cells per condition per experiment), and error bars represent standard deviation (SD) of 5 independent experiments.

- Quantification of centromeric CENP‐A levels normalized to non‐treated level. Each dot represents one experiment, and error bars represent SD. Unpaired t‐test: ***P = 0.0005.

- Stills of live cell imaging to follow de novo CENP‐AEA reloading in RPE‐1 cells harboring endogenously tagged CENP‐Bmcherry. Images were taken every 15 min. White dashed circles contour nuclei prior/after mitosis and cells during mitosis based on bright‐field images. Scale bar, 10 μm.

- Dot plot showing the timing of CENP‐AEA reloading after anaphase onset in the indicated cell lines. Each dot represents one cell, and error bars represent standard deviation. Unpaired t‐test, ns.

Source data are available online for this figure.

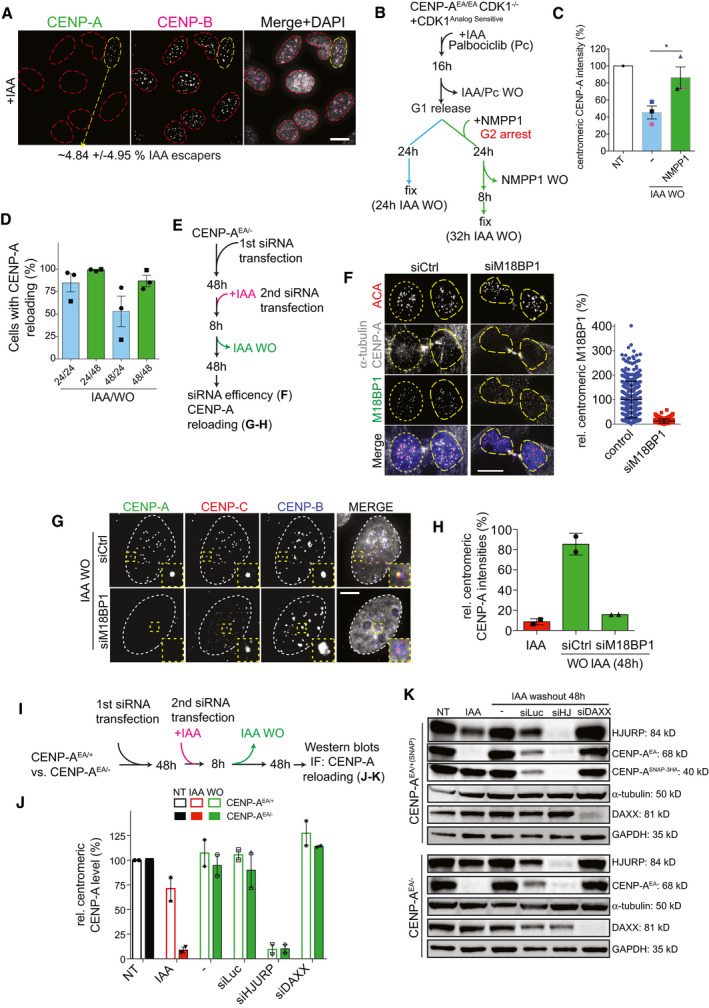

Figure EV1. (related to Fig 1). De novo CENP‐A reloading follows the canonical CENP‐A deposition pathway.

- Image of IAA‐treated cells. IAA escaper is highlighted with a dashed yellow circle, and CENP‐A depleted cells are contoured with red dashed lines. Scale bar, 10 μm.

- Schematic for the experiments shown in C.

- Quantification of centromeric CENP‐A levels normalized to non‐treated level. Each dot represents one experiment, and error bars represent SD. Unpaired t‐test: *P = 0.0493.

- Quantification of the relative number of DLD‐1 (square) and U‐2OS (circle) cells with centromeric CENP‐A at the indicated timing of IAA treatment and recovery. Each dot represents one experiment with at least 20 cells per condition. Error bars represent standard deviation (SD) from 3 independent experiments.

- Schematic for the experiments shown in F‐H.

- Left panel: representative images to confirm M18BP1 knock‐down in late M phase cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. Yellow dashed lines highlight nuclei of daughter cells. Right panel: relative M18BP1 levels in late M/early G1 phase after siRNA knock‐down using M18BP1 antibody. Each dot represents one centromere, and error bars represent standard deviation.

- Representative images of de novo CENP‐A reloading upon M18BP1 knock‐down. Nuclei are highlighted with white dashed lines. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Quantification of centromeric CENP‐A intensities in the indicated conditions (relative intensities normalized to CENP‐A level in untreated cells). Each dot represents one experiment (> 30 cells per condition per experiment), and error bars represent SD of 2 independent experiments.

- Schematic representation for the experiments shown in J‐K.

- Bar graphs showing quantification of centromeric CENP‐A intensities following the indicated treatment. Each dot represents one experiment with at least 30 cells. Error bars represent SD of 2 independent experiments.

- Immunoblot of total protein levels in the indicated cell lines and conditions.

Source data are available online for this figure.

We next tested if newly expressed CENP‐A is reloaded back at the native centromere position by immunofluorescence (IF). Following CENP‐A depletion for 4–8 h and IAA WO for 24 or 48 h, we found that in most (~90%) of the cells, newly expressed CENP‐A re‐localizes with centromeric regions marked by CENP‐B, which remains tightly bound to the CENP‐B boxes (Fig 1C–E). Interestingly, centromeric CENP‐A levels recovered to only ~50% of untreated levels after one cell cycle (24‐h WO), but fully recovered to untreated levels after IAA 48‐h WO (Fig 1E). This was due to incomplete recovery of total CENP‐A levels rather than the absence of preexisting CENP‐A molecules or preexisting centromeric factors that mediate CENP‐A assembly. Indeed, centromeric CENP‐A amount recovered to untreated levels within one cell cycle when we prolonged G2 phase—time where most CENP‐A is transcribed (Shelby et al, 1997)—after IAA WO using a CDK1 analog sensitive inhibition system (Hochegger et al, 2007; Saldivar et al, 2018) (Fig EV1B and C). Following short‐term CENP‐A depletion, many CCAN components partially remain at centromeric regions (Hoffmann et al, 2016), potentially promoting CENP‐A deposition (Okada et al, 2006; Hori et al, 2008; McKinley et al, 2015). We thus depleted CENP‐A for longer durations (24–48 h) as, in these conditions, most CCAN proteins are lost from centromeres (Hoffmann et al, 2016). We used p53‐deficient DLD‐1 cells and chromosomally unstable U‐2OS cells to bypass cell cycle block due to events of chromosome mis‐segregation following CENP‐A depletion. Even in these conditions, newly expressed CENP‐A molecules were reloaded at CENP‐A‐depleted centromeres (Fig EV1D).

We then followed de novo CENP‐A reloading using live cell imaging taking advantage of the EYFP tag on the endogenous CENP‐A (Hoffmann et al, 2016). To mark centromere position in live cells, we endogenously tagged CENP‐B with mCherry using CRISPR/Cas9 in RPE‐1 cells. Following the induction of a CENP‐AOFF/ON cycle, we observed a burst of reloading of CENP‐A shortly after mitotic exit (approximately 30 min after anaphase onset) (Fig 1F and G, Movie EV1), in agreement with the previously described timing of CENP‐A reloading (Jansen et al, 2007). This experiment showed that CENP‐A reloading in the absence of any previously deposited centromeric CENP‐A is still tightly restricted to a narrow cell cycle window. So, we further examined if de novo CENP‐A reloading relies on the same key regulation mechanisms as canonical CENP‐A deposition (McKinley & Cheeseman, 2016). We confirmed that de novo CENP‐A deposition is dependent on M18BP1 and HJURP, but not DAXX, a histone chaperone that was shown to be involved in non‐centromeric CENP‐A deposition (Lacoste et al, 2014) (Fig EV1E–K). However, as HJURP depletion strongly impacts the stability of soluble CENP‐A, re‐expression of CENP‐A was also strongly affected by HJURP depletion making a direct conclusion on HJURP dependency uncertain (Fig EV1K).

Altogether, our data indicate that centromere position is preserved even in the absence of CENP‐A. Also, it demonstrates that previously assembled CENP‐A is not essential for de novo deposition of CENP‐A nor to control its abundance, as levels of new CENP‐A rise very fast at CENP‐A‐depleted centromeres, a result in disagreement with the template model. Further, like canonical CENP‐A reloading in the presence of previously deposited CENP‐A, de novo CENP‐A reloading is cell cycle regulated and occurred exclusively after mitotic exit.

Our results rely on complete depletion of CENP‐A following IAA addition, as we have previously shown by IF, immunoblot and immunoprecipitation (Hoffmann et al, 2016). To further prove the efficiency of the auxin system, we challenged it by inducible, doxycycline‐mediated overexpression (OE) of CENP‐A tagged with EYFP and AID (Fig EV2A). CENP‐A OE leads to elevated CENP‐A incorporation at the centromere and also outside the centromere region (Lacoste et al, 2014; Nechemia‐Arbely et al, 2017). Using this system, we obtained ~2,000‐fold higher nuclear CENP‐AEA protein level as compared to endogenous CENP‐A levels at a single centromere (Fig EV2B and C). Despite the vast excess of CENP‐A in these cells, no CENP‐A was detectable upon IAA addition by IF (Fig EV2B and C). We concluded that the AID system remains—by far—unsaturated under endogenous CENP‐A expression level conditions, as we are able to deplete higher CENP‐AEA levels to non‐detectable level.

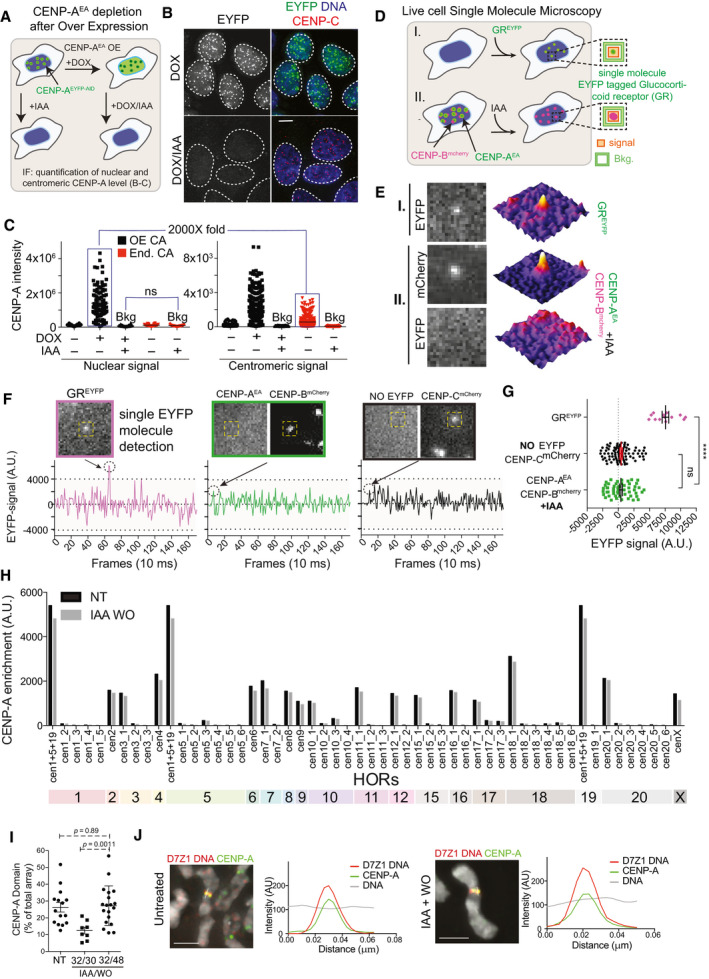

Figure EV2. (related to Fig 2). Complete centromeric CENP‐AEA depletion with the AID system.

- Schematic illustration of experiment shown in B, C.

- Representative images showing complete depletion of CENP‐AEA despite doxycycline (DOX)‐induced overexpression in DLD‐1 cells. Nuclei are contoured with white dashed lines. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Quantification of CENP‐A intensities in the nucleus and at the centromere in the presence or absence of IAA/DOX. Endogenous (End.) CENP‐AEYFP‐AID (CA) or overexpressed (OE) CA is depleted to non‐detectable background‐level in the presence of IAA. Each dot represents a cell. Mean CA intensities are indicated by a black line.

- Schematic illustration of the single molecule microscopy (SMM) experiments shown in E, G.

- Representative microscopy images from live cell imaging and corresponding 3D surface plots showing single molecule GREYFP detection in I and following IAA treatment CENP‐AEA signal absence at CENP‐Bmcherry marked centromeres in II, using SMM acquisition settings.

- Examples of background‐corrected EYFP signal intensities quantified over time (as shown in D) for single GREYFP molecules (in magenta), centromeric EYFP signals in IAA‐treated CENP‐AEA/EA cells (in green), and in the absence of EYFP molecules (in black).

- Signal quantification as shown in D in the indicated conditions. Unpaired t‐test, ns (P = 0.88), ****P < 0.0001, error bars represent standard deviation. Each dot represents the quantification of one GREYFP signal (GREYFP, n = 13) or one centromere, respectively (No EYFP CENP‐Cmcherry, n = 85 and CENP‐Bmcherry CENP‐AEA, n = 52).

- CENP‐A levels at the indicated HOR arrays quantified by CUT&RUN sequencing. CENP‐A levels 48 h after IAA wash‐out recover at the original HOR.

- Quantifications of CENP‐A occupancy at the DXZ1 HOR array after one CENP‐AOFF/ON cycle in DLD‐1 cells using IF‐FISH on chromatin fibers. Each dot represents a single chromatin fiber. Error bars show standard deviation. P‐values from unpaired t‐test.

- Line scan analysis at the D7Z1 array on chromosome spreads in the indicated treatment. Scale bar, 2 μm.

We then used live cell single molecule microscopy (SMM) to assess the presence of single CENP‐A molecules tagged with EYFP after IAA addition. We first confirmed the ability to detect a single EYFP molecule by transiently expressing EYFP‐tagged Glucocorticoid Receptor (GREYFP) as it was previously used to study dynamics of single molecules in human cells (Harkes et al, 2015) (Fig EV2D). Here, we observed a clear diffraction limited spot with a Gaussian profile that bleached in a single bleach step as expected when observing a single molecule (Fig EV2E–G). In contrast, we were unable to detect such profile for CENP‐AEA at CENP‐BmCherry‐positive centromeres following IAA treatment. Quantification of EYFP fluorescent intensities of IAA‐treated CENP‐AEA cells at centromeres was significantly lower than the fluorescent signal of a GREYFP single molecule and comparable to the background signal obtained in EYFP‐free RPE‐1 CENP‐CmCherry‐AID cells (Fig EV2E–G).

In summary, we concluded that CENP‐A reloading following CENP‐AOFF/ON is unlikely to be due to any remaining CENP‐A molecules. In addition, as CENP‐A loading occurs only at mitotic exit, the dynamic equilibrium between its IAA‐mediated degradation and re‐expression does not influence our results.

De novo CENP‐A localization remains unaltered in the absence of old centromeric CENP‐A

Human centromeres display a hierarchical organization ultimately structured as higher order repeat arrays (HOR) (Miga, 2017). Some chromosomes have centromeres with multiple HOR arrays which display different abundance of CENP‐B boxes and CENP‐A occupancy (Sullivan et al, 2011). In some cases (e.g., chromosomes 7 or 17), the two homologue chromosomes display equal CENP‐A occupancy but at different HOR arrays (epiallelic status) (Maloney et al, 2012). Also, it has been demonstrated that inactive HOR arrays with low CENP‐A occupancy have the capacity to trigger HAC formation (Maloney et al, 2012). The CENP‐A self‐assembly mechanism model implies that previously incorporated CENP‐A is required to avoid the sliding of the centromere to a different chromosomal position.

Using the CENP‐AOFF/ON system, we tested if de novo CENP‐A deposition was slightly displaced ultimately leading to a different distribution at HOR arrays within the same centromeric locus (Fig 2A). CENP‐A—HOR array occupancy was determined by CUT&RUN (Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease) combined with high‐throughput sequencing (Skene & Henikoff, 2017). Sequencing reads were mapped to the latest HOR reference assembly for centromeric sequences, as described previously (Dumont et al, 2020). In agreement with previous observations of CENP‐A occupancy, in untreated cells, CENP‐A localized mostly to a defined HOR, but it could also be found on different HORs of the same chromosome (Sullivan et al, 2011; Nechemia‐Arbely et al, 2019). Following CENP‐A depletion and re‐activation, we found that the distribution of de novo CENP‐A along the different HORs was maintained, as we did not observe any remarkable differences in CENP‐A HOR array occupancy compared to the untreated condition (Figs 2B–D and EV2H). These results were confirmed by line scan and by chromatin fiber techniques coupled with FISH (Fig EV2I and J). Here, we determined CENP‐A occupancy along the HOR array of chromosome X (DXZ1) and found that CENP‐A re‐occupies around 35% of the DXZ1 array within 48 h (Fig EV2I), similar to the control and in agreement with previous results (Maloney et al, 2012).

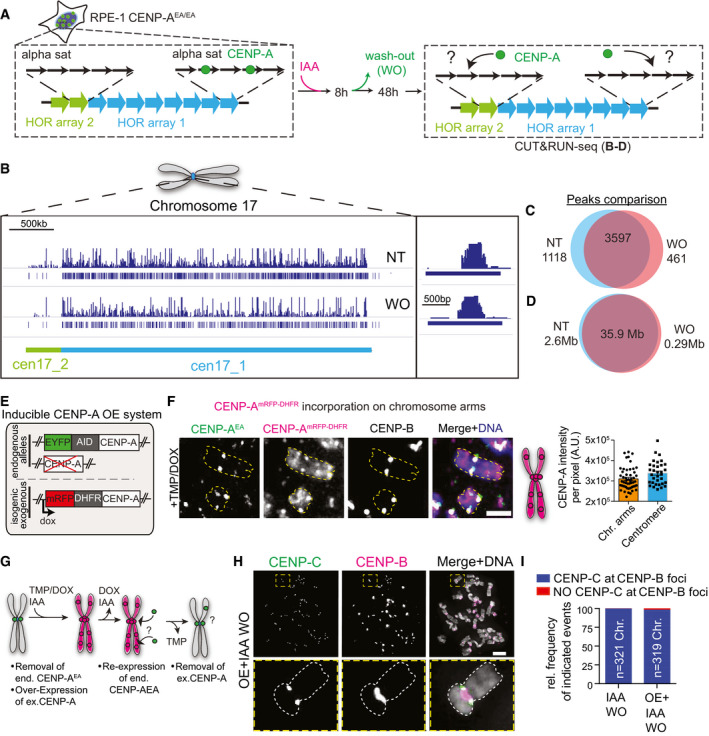

Figure 2. Previously deposited CENP‐A is dispensable for precise de novo CENP‐A incorporation.

- Schematic of DNA sequence organization at centromeres with more than one higher order repeat array (HOR) and experimental set‐up of the CENP‐AOFF/ON cycle performed in experiments B‐D.

- Full coverage plot of chromosome 17 centromeric array (chr17:22,500,000–26,900,000 of the hg38 assembly) showing enrichment of CENP‐A by CUT&RUN‐seq in the untreated (NT) and IAA wash‐out (WO) sample. CENP‐A is reloaded to cen17_1 (D17Z1). A shift of CENP‐A occupancy to cen17_2 (D17Z1B) is not detected.

- Venn diagram showing the number of CUT&RUN‐seq peaks that are NT specific (left, blue), WO specific (right, red), or overlapping (center).

- Venn diagram showing the total length in Mb of CUT&RUN‐seq peaks that are NT specific (left, blue), WO specific (right, red), or shared between NT and WO (center).

- Illustration of genomic make‐up of DLD‐1 with an exogenous CENP‐AmRFP‐DHFR overexpression system.

- Representative images showing ectopic CENP‐A on a chromosome spread after induction of CENP‐A overexpression in DLD‐1 cells. Centromere position is marked using immunofluorescence staining for CENP‐B. Yellow dashed lines contour representative chromosomes. Scale bar, 2 μm. Schematic to the right illustrates the observed CENP‐AmRFP‐DHFR localization pattern on a chromosome. Right panel: Comparison of CENP‐ADHFR level per pixel at the centromere and on chromosome arms following IAA and DOX/TMP treatment. Each dot represents one centromere or a region on the chromosome arms.

- Schematic illustration for the experiments shown in H, I.

- Representative images of chromosome spreads after re‐expression of endogenous CENP‐AEA into a CENP‐AmRFP‐DHFR overexpression background and subsequent removal of the overexpression as illustrated in (G). Antibody against CENP‐C was used to score for the presence of the functional centromere. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Quantification of the indicated events after one CENP‐AOFF/ON cycle compared to treatment shown in (G).

Altogether, we concluded that CENP‐A is reloaded at the same HOR array even in the absence of previously deposited CENP‐A and that (epi‐)genetic mechanism(s) other than CENP‐A are involved in maintaining centromere position.

To further test the importance of the original centromere location, we then generated an in vivo competition assay between the native centromeres lacking endogenous CENP‐A and ectopic site(s) enriched with exogenous CENP‐A. To do so, we used an inducible CENP‐A OE system with a binary (on/off) controllable activity in the CENP‐AOFF/ON background. This binary control is achieved via a doxycycline‐inducible expression of CENP‐A tagged with a destabilization domain E. coli‐derived DiHydroFolate Reductase (DHFR) protein (Fig 2E). Addition of a small ligand named TriMethoPrim (TMP) is required for protein stabilization (Iwamoto et al, 2010). We then assessed if de novo endogenous CENP‐A reloads at non‐centromeric sites following mis‐incorporation of exogenous CENP‐A—which can be indistinguishable from centromeric CENP‐A (Fig 2F)—and if this was sufficient to trigger ectopic centromere formation (Fig 2G). In most analyzed cases, centromere function (defined by the presence of CENP‐C) was occurring at CENP‐B marked centromeres and never observed at ectopic loci despite the initial presence of ectopic CENP‐A along the chromosome arms (Fig 2H and I).

These data demonstrate the importance of alpha‐satellite DNAs and their embedded features in marking centromere position.

De novo CENP‐A deposition is impaired in CENP‐B‐deficient cells

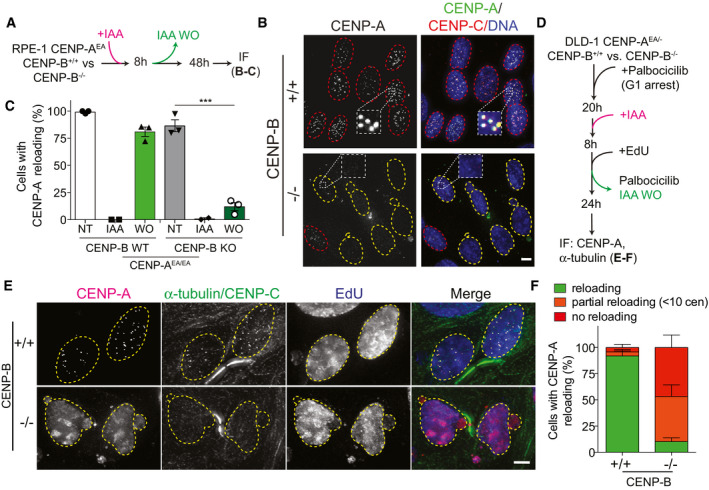

We next asked what maintains centromere position in the absence of previously deposited CENP‐A. We have already demonstrated that CENP‐B plays a major role in stabilizing centromere proteins, including a fraction of CENP‐C, on CENP‐A‐depleted centromeres (Hoffmann et al, 2016). We therefore hypothesized that CENP‐B may be important for de novo CENP‐A deposition. To test this, we assessed CENP‐A de novo deposition in CENP‐B KO RPE‐1 cells harboring the CENP‐AOFF/ON system (Hoffmann et al, 2016). Following CENP‐AOFF/ON, we found that de novo CENP‐A reloading was strongly impaired in CENP‐B −/− cells compared to CENP‐B +/+ cells, with < 20% of the cells that reloaded CENP‐A upon re‐expression (Fig 3A–C).

Figure 3. De novo CENP‐A deposition is impaired in the absence of CENP‐B.

- Schematic illustration of the CENP‐AOFF/ON cycle performed in the experiments shown in B, C.

- Representative images of de novo CENP‐A reloading in CENP‐B wild‐type (+/+) and CENP‐B knock‐out (−/−) cells. Cells with centromeric CENP‐A are marked with a red dashed contour line, while a yellow contour lines mark cell without centromeric CENP‐A. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Quantification of relative number of RPE‐1 cells with centromeric CENP‐A in the indicated conditions. Each dot represents one experiment with at least 20 cells per condition. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM) from 3 independent experiments. Unpaired t‐test, ***P = 0.0003.

- Schematic representation of experiments shown in E, F.

- Representative images of DLD‐1 CENP‐B (+/+) or (−/−) cells in late M phase following one CENP‐AOFF/ON cycle. EdU staining was used to confirm successful wash‐out of palbociclib and cell progressing through S‐phase. Yellow dashed lines contour nucleus of cells in late M phase. Scale bar 5 μm.

- Quantification of indicated events observed in late M phase cells in the indicated cell lines. Error bars show SEM from 4 independent experiments.

Co‐depletion of CENP‐A and CENP‐B leads to immediate mitotic defects (Hoffmann et al, 2016) that result in a p53‐mediated cell cycle arrest. So, we first tested if massive chromosome mis‐segregation per se has an effect on de novo CENP‐A reloading by chemical inhibition of the spindle checkpoint kinase Mps1 (Santaguida & Musacchio, 2009). Despite massive chromosome mis‐segregation in this condition, de novo CENP‐A reloading was not affected (Fig EV3A–C). To rule out that failure of de novo CENP‐A deposition in CENP‐B KO cells is not simply a consequence of cell cycle arrest, we depleted CENP‐B using CRISPR in a p53‐deficient DLD‐1 cell line (Fig EV3D). We then synchronized cells to specifically assess de novo CENP‐A reloading uniquely in cells that underwent mitosis following the CENP‐AOFF/ON pulse (Fig 3D). Using α‐tubulin staining to visualize early G1 cells, we found that ~90% of CENP‐B −/− cells showed impaired de novo CENP‐A reloading while almost all CENP‐B +/+ cells successfully reloaded CENP‐A (Fig 3E and F), similar to control RPE‐1 cells. Interestingly, ~50% of the CENP‐B −/− cells failed to reload CENP‐A completely, while around 40% of cells showed only partial reloading of CENP‐A with less than 10 centromeric CENP‐A dots per daughter cell (Figs 3E and F, and EV3E). We then tested if re‐expression of CENP‐B could rescue CENP‐A de novo deposition in CENP‐B KO cells. To this aim, we integrated CENP‐B into an isogenic FRT locus that can be induced by doxycycline addition. Following a CENP‐AOFF/ON pulse, most cells rescued by CENP‐B successfully reloaded CENP‐A to a similar extent as the CENP‐B wild‐type cell line (Fig EV3F and G).

Figure EV3. (related to Fig 3). CENP‐B is a key factor for efficient de novo CENP‐A reloading.

-

ARepresentative immunofluorescence showing de novo CENP‐A deposition in CENP‐B (+/+) DLD‐1 cells after reversine‐induced chromosome mis‐segregation. DAPI staining is contoured by a white dashed line. Scale bar, 5 μm.

-

B, CBar graphs showing the relative number of CENP‐A-positive cells (B) and the level of centromeric CENP‐A level (C) in the presence of reversine. Each dot represents one experiment with more than 20 cells per condition. Error bars represent SD of 3 independent experiments.

-

DLeft: schematic of the CRISPR/Cas9 strategy to deplete CENP‐B in DLD‐1 cells as measured in the dot plot on the right. Each dot represents one centromere, and error bars show standard deviation.

-

EImmunofluorescence images showing partial de novo CENP‐AEA reloading (< 10 centromeres) in CENP‐B−/− DLD‐1 cells in late M phase. Nuclei of daughter cells are highlighted with white dashed lines. Scale bar, 5 μm.

-

FImmunoblot of total protein levels in the indicated conditions in the indicated cell line. FL = full length.

-

GBar graphs showing the relative number of DLD‐1 cells with centromeric CENP‐A in indicated conditions in the indicated cell line. Each dot represents one single experiment, > 30 cells per condition. Unpaired t‐test, **P = 0.0053, error bars represent SD of 4 independent experiments.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Overall, our data demonstrate that CENP‐B is required for efficient reloading of de novo CENP‐A in the absence of any previously deposited centromeric CENP‐A

Overall, our data demonstrate that CENP‐B is required for efficient reloading of de novo CENP‐A in the absence of any previously deposited centromeric CENP‐A

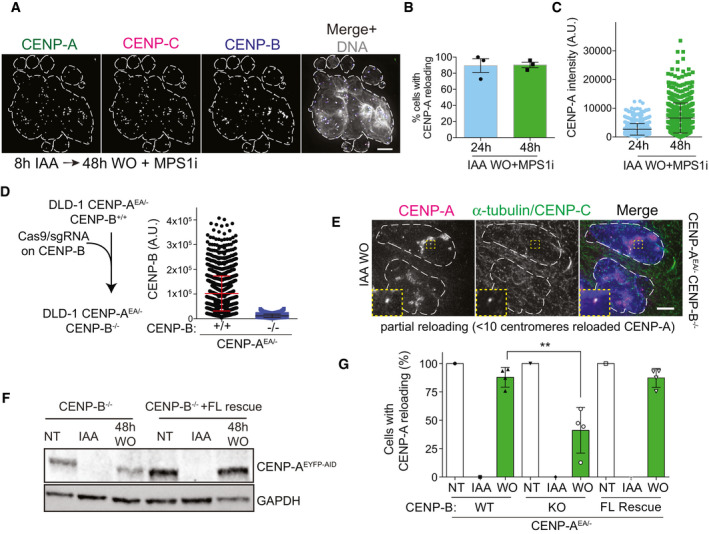

Neocentromere formation occurs on the Y chromosome under selective pressure

The centromere of the Y chromosome contains repetitive alpha‐satellite DNA sequences but lacks CENP‐B binding sites. Hence, CENP‐B is absent from the Y centromere (Earnshaw et al, 1989; Miga et al, 2014). To assess de novo CENP‐A reloading at the Y centromere, we used Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) probes against the Y centromere or the X centromere, as a control, in combination with IF in interphase cells and on metaphase spreads in DLD‐1 cells (Fig 4A and B). Following a CENP‐AOFF/ON cycle, de novo CENP‐A or CENP‐C colocalized with the X centromere in both interphase and metaphase spreads, respectively, with no significant changes in abundance when compared to non‐treated cells or to single allele AID‐tagged CENP‐AAID/+cells (Fig 4C and D and Appendix Fig S1A and B). Conversely, only ~25% of cells showed CENP‐A/CENP‐C at the Y centromere in both interphase (Appendix Fig S1A and B) and mitotic (Fig 4C and D) cells. So, as observed in CENP‐B KO cells, de novo CENP‐A reloading is impaired at CENP‐B lacking centromeres.

Figure 4. Neocentromere formation arises at the CENP‐B‐negative Y chromosome.

- Concept of experiments shown in B‐D.

- Timeline of experiment performed in C, D.

- Representative IF‐FISH images of mitotic spreads in non‐treated cell (NT) and following a CENP‐AOFF/ON cycle (IAA WO). Chromosomes are contoured by a green (X), magenta (Y), or white (other autosomes) dashed line. The centromeres of chromosome X/Y are highlighted by a green/magenta arrow. Scale bar, 2 μm.

- Quantification of CENP‐C (as read‐out of CENP‐A) presence at the X (green) or Y (magenta) centromere in the indicated cell lines. Each dot represents one experiment. Error bars represent SD from 3 independent experiments. Unpaired t‐test, **P = 0.0042.

- Schematic illustration of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of the non‐essential RPS4Y gene on the Y chromosome with the insertion of a neomycin resistance cassette.

- Experimental set‐up for G, H.

- Representative IF‐FISH images showing CENP‐C localization on the Y chromosome in cell growing under selective pressure (G418) following a CENP‐AOFF/ON cycle. Chromosomes are highlighted by a white dashed contour line. CENP‐C was found at the native centromere position (top panel, blue), the Y chromosome fused to another chromosome indicated by the increased size of the chromosome and the absence of Chr‐Y painting probe staining (second panel, orange) or CENP‐C was found on a different location on the Y chromosome and did not overlap with Cen‐Y DNA (lower panels, red). Scale bar, 2 μm.

- Quantification of indicated events depicted in G. Each dot represents one experiment (> 20 spreads for experiment). Error bars represent SEM from 3 independent experiments. Unpaired t‐test, *P = 0.0137 and 0.039.

We then studied whether CENP‐A deposition can occur at a different, non‐alpha‐satellite location after CENP‐A re‐expression. However, the Y chromosome is not an essential chromosome in the in vitro cell culture model, and since neocentromere formation happens at very low frequency (Shang et al, 2013), the impaired CENP‐A reloading is expected to lead to the loss of the Y chromosome in the majority of cells (Ly et al, 2017). To prevent its loss, we selected for the retention of the Y chromosome by inserting a selectable cassette (neomycin) (Fig 4E and Appendix Fig S1C and D). Following CENP‐A depletion and re‐activation, we subjected cells to G418 treatment to select clones that maintained the Y chromosome (neomycin positive), as observed by colony formation assay (Appendix Fig S1E). Following a CENP‐AOFF/ON cycle, we observed a strong impact of G418 selection on cell viability that likely reflects failure of CENP‐A deposition on the Y chromosome and subsequent loss of the chromosome bearing the selection marker. IF‐FISH on the pool of surviving clones revealed three outcomes: (i) In ~70% of the cells, CENP‐C was found to be at the original Y centromere location, indicating that other centromere features different from CENP‐A and CENP‐B favor centromere formation at native centromere position (Fig 4F–H); (ii) in about 15% of the cells, the entire or portions of the Y chromosome (likely containing the neomycin cassette) was fused to other chromosomes, an event that could be observed also in untreated condition, although at very low frequency (Fig 4G and H); (iii) intriguingly, in the about 15% of remaining cases, CENP‐C staining was observed elsewhere on the Y chromosome, and not coinciding with the Y centromeric probe, indicating the presence of a neocentromere (Fig 4G and H). Importantly, neocentromere‐like elements were exclusively found after CENP‐A depletion and re‐activation by IAA WO, but never under untreated conditions (Fig 4H).

These data indicate that neocentromere‐like elements can form on a CENP‐B‐deficient chromosome following rapid CENP‐A re‐expression, but only when CENP‐A‐mediated centromere identity was transiently perturbed. Nevertheless, native centromere location continues to be the preferential site for centromere re‐formation.

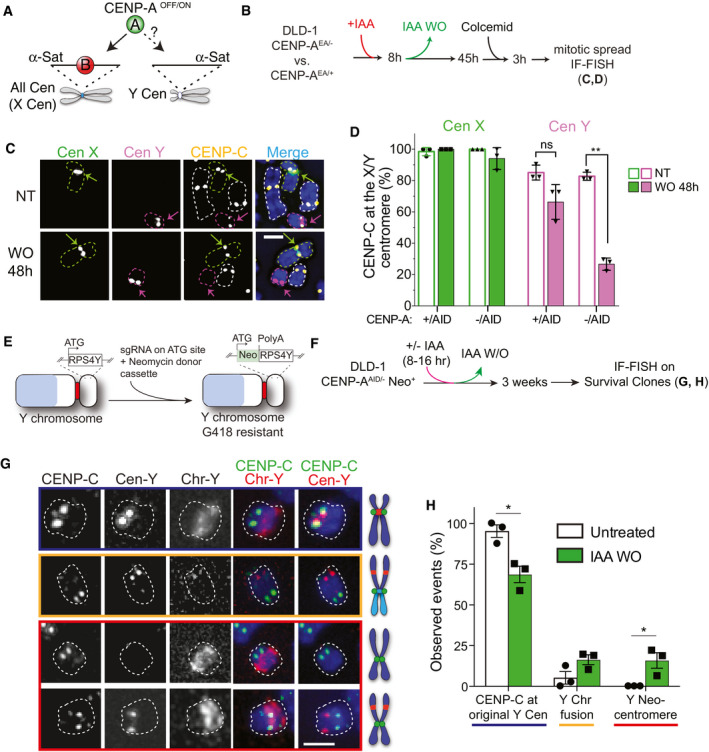

CENP‐B bound to an ectopic location promotes CENP‐C recruitment independently of CENP‐A

We next investigated how CENP‐B maintains centromere position at native centromeres. Previous studies showed that CENP‐C interacts with CENP‐B directly (Suzuki et al, 2004; Fachinetti et al, 2015), in addition to its well‐known interaction with CENP‐A (Guse et al, 2011; Fachinetti et al, 2013; Kato et al, 2013). Here, we noticed that exogenous CENP‐B expression not only rescued de novo CENP‐A reloading in CENP‐B−/− cells (Fig EV3G), but also lead to increased CENP‐C levels at the centromeres that were mostly maintained even after CENP‐A depletion (Appendix Fig S2A and B). These observations indicate that CENP‐B not only maintains and stabilizes CENP‐C (Hoffmann et al, 2016), but might also recruit CENP‐C de novo to the centromere.

To test this hypothesis, we used the LacO‐LacI system in a previously described U‐2OS cell line (Janicki et al, 2004) in which we further integrated the CENP‐AOFF/ON system at the CENP‐A endogenous locus. This system allows us to test whether CENP‐B can recruit CENP‐C to an ectopic LacO locus independently of CENP‐A (Fig 5A). Following transfection of CENP‐B‐LacI‐mCherry, CENP‐C recruitment to the ectopic big LacI/CENP‐B sites was observed in the majority of the cells, even upon IAA treatment to deplete CENP‐A, in contrast to the LacI/mCherry control (Fig 5B–D). Interestingly, CENP‐C molecules at the LacO array were organized in patches rather than covering LacO sites homogenously. Based on previous studies (Hori et al, 2013; Shono et al, 2015), we predicted that once CENP‐C is recruited to the LacO array, it should recruit CENP‐A. Indeed, following IAA WO, CENP‐A was recruited at most CENP‐B/CENP‐C‐positive LacO arrays (Fig 5C–E). Efficient recruitment of CENP‐A was dependent on CENP‐C, as pre‐removal of CENP‐C by siRNA largely abolished CENP‐A recruitment at CENP‐B‐positive LacO arrays (Appendix Fig S2C–G). Residual CENP‐A recruitment in this condition could be due to incomplete CENP‐C depletion by siRNA or to a weak ability of CENP‐B to directly recruit CENP‐A (Fujita et al, 2015). CENP‐A recruitment via CENP‐C further stabilizes the latter, as we found that CENP‐C levels at the LacO array were higher in cells that had CENP‐A (non‐treated cells and in the IAA WO) compared to IAA‐treated cells (Fig 5B–D).

Figure 5. Ectopic CENP‐B is capable to recruit CENP‐C independently of CENP‐A at LacO arrays.

- Experimental schemes for B‐F. LacI‐CENP-B or LacI control (baits) was expressed into CENP‐AEA/− lacO‐tetO U‐2OS cells. Immunostaining against CENP‐C or CENP‐A (preys) was performed following LacI‐CENP-B transfection in untreated, IAA‐treated, and IAA wash‐out (WO) conditions.

- Representative immunofluorescence images showing CENP‐C recruitment at the LacO array in the indicated conditions. LacO array is displayed in the insets. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Bar plot showing frequency of CENP‐C (orange) or CENP‐A (green) recruitment to LacO array in the indicated conditions. Each dot represents one independent experiment (> 20 cell analyzed for experiment). Error bars represent SEM from 3 independent experiments. Unpaired t‐test, ****P < 0.0001.

- Quantification of CENP‐C (orange) or CENP‐A (green) protein levels at the LacO array in the indicated conditions normalized to protein intensities in non‐treated conditions at the mCherry‐LacI-CENP‐B-LacO array using CENP‐A or CENP‐C antibody. Each dot represents one independent experiment (> 20 cell analyzed for experiment). Error bars represent SEM from 3 independent experiments. Mann–Whitney test was performed on pooled single cell data of three independent experiments, ****P < 0.0001.

- Representative immunofluorescence images showing CENP‐A recruitment to ectopic mCherry‐LacI-CENP‐B in the indicated conditions. LacO array is shown in the inset. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Quantification of the frequency of CENP‐C recruitment to LacO arrays by different LacI constructs. Error bars represent SEM from 5 independent experiments. Unpaired t‐test, ***P = 0.0001.

- CENP‐B immunoblot following GST pull‐down experiments using GST‐tagged CENP‐C (1–727) as bait and with the indicated proteins as preys.

Source data are available online for this figure.

We next tested which CENP‐B domains were involved in CENP‐C recruitment. Previous yeast two‐hybrid analysis suggested that CENP‐B's acidic domain interacts with CENP‐C (Suzuki et al, 2004). We transiently expressed several CENP‐B constructs that lack either the DNA Binding Domain (DBD), the acidic domain, or both. As positive and negative controls, we used CENP‐B Full Length (FL) and H3.1 or CENP‐TΔC (Gascoigne et al, 2011), respectively. As the DBD of CENP‐B was shown to interact with CENP‐A (Suzuki et al, 2004; Fujita et al, 2015), we performed these experiments in the absence of CENP‐A (+IAA) to avoid any interference of CENP‐A in CENP‐C recruitment. In agreement with previous studies (Gascoigne et al, 2011; Hori et al, 2013), we could not observe CENP‐C recruitment by H3.1 or ectopic CENP‐T. Surprisingly, CENP‐C was recruited at the CENP‐BΔacidic‐LacI in a similar manner to that of FL or ΔDBD (Fig 5F). However, double deletion of both the DBD and the acidic domain almost completely prevented CENP‐C recruitment to a level similar to that of CENP‐T or the negative control H3.1 (Fig 5F). This remaining small fraction of CENP‐C recruited to the LacO could be due to the presence of endogenous CENP‐B that dimerizes with the CENP‐B variants. We confirmed these results using pull‐down assays with purified recombinant proteins (Appendix Fig S2H–J). Here, we observed direct interaction between GST‐CENP‐C (1–727) and ΔDBDCENP‐B (Fig 5G). However, removal of the acidic domain in ΔDBDCENP‐B abolished the interaction with CENP‐C (Fig 5G). In summary, we concluded that both the acidic domain and the DBD of CENP‐B are involved in CENP‐A‐independent recruitment and maintenance of CENP‐C that, in principle, is capable to initiate the epigenetic centromere assembly loop mediated by CENP‐A.

CENP‐B marks native centromere position to promote de novo CENP‐A/C reloading

Given the strong enrichment of CENP‐B‐LacI at the LacO array, it was unclear if the interaction with CENP‐C is relevant for new CENP‐A deposition at endogenous centromeres. In addition, CENP‐B‐LacI at the LacO array could potentially cluster with endogenous centromeres. Therefore, we tested if CENP‐B could promote centromere formation also at the native centromere position, where CENP‐B levels are far lower compared to the LacI system. To test this, we generated a DLD‐1 cell line in which both endogenous CENP‐A and CENP‐C can be rapidly depleted (and re‐expressed) simultaneously using the auxin‐inducible protein degradation system (CENP‐A/COFF/ON; Appendix Fig S3A–C).

After CENP‐A/C depletion and re‐activation, we tested if both proteins were reloaded de novo to the centromere and if it was CENP‐B‐dependent (Fig 6A and B). Following CENP‐A/COFF/ON, we observed reloading of both proteins at some CENP‐B‐positive centromeres in ~30% of the cells (Fig 6C and D). CENP‐A reloading under this condition was also observed by live cell imaging (Movie EV2 and Appendix Fig S3E) and CUT&RUN followed by qPCR (Fig 6E). We noticed that only a fraction of centromeres per cell show efficient reloading, as also demonstrated by the low CENP‐A/C centromeric protein levels upon re‐activation (Appendix Fig S3F). When CENP‐A/C reloading did not occur at all centromeres, there was a detrimental impact on cell viability, differently to what we observed in cells in which only CENP‐A is removed and re‐activated (Appendix Fig S3G).

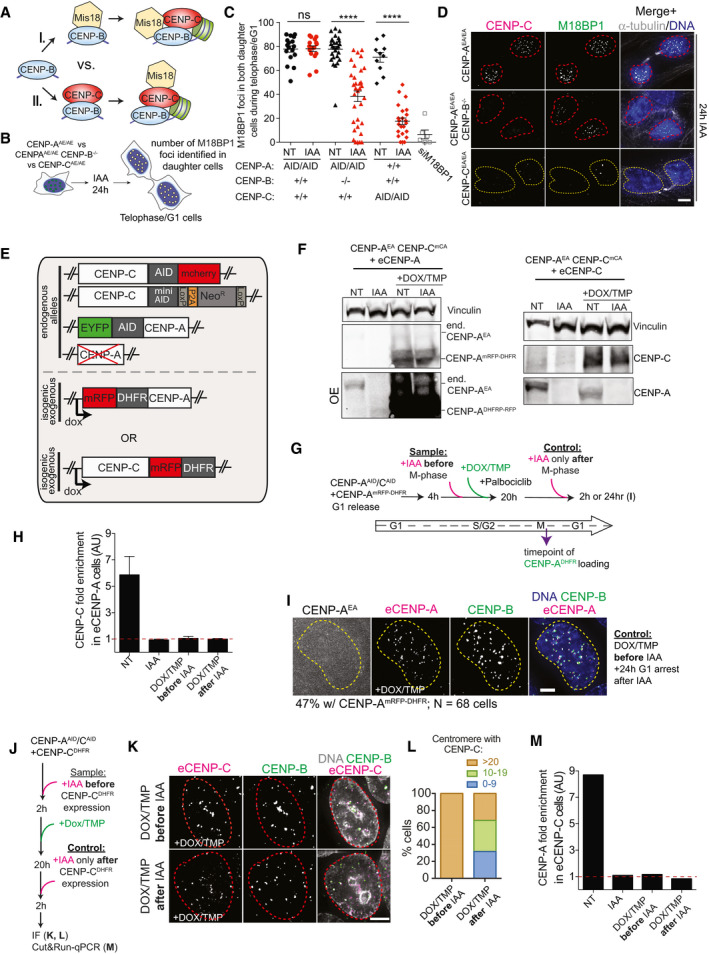

Figure 6. CENP‐B drives de novo CENP‐A and CENP‐C assembly at endogenous centromeres.

- Schematic representation of experiments in B–E.

- Timeline of experiment in C‐E.

- Representative immunofluorescence images showing CENP‐A and CENP‐C reloading in the indicated conditions. Cells with centromeric CENP‐A/CENP‐C are marked with a red dashed contour line, while a yellow contour lines mark cell without centromeric CENP‐A. The centromere position is marked using immunofluorescence staining for CENP‐B. White dashed lines contour DAPI stained nucleus of representative cells. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Bar plot showing the percentage of cells with CENP‐A and CENP‐C co-localization after a CENP‐A/COFF/ON cycle in the indicated conditions. Error bars show SD from 5 independent experiments. Unpaired t‐test, ***P = 0.0002. Each dot represents one experiment (> 30 cells analyzed for experiment).

- Box plot of CUT&RUN–qPCR for CENP‐A (green) or CENP‐C (orange). Box plot shows median, 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers show minimum and maximum values. Results from 3 independent experiments including combined data from qPCRs using alpha‐satellite primers and primers binding at the centromere of chromosome 4. Enrichment is measured relative to the IgG control and normalized to Alu repeats. Mann–Whitney test, CENP‐A: **P = 0.0087, *P = 0.0411, CENP‐C: **P = 0.0022.

Despite only a fraction of centromeres show CENP‐A/C reloading, our data indicate that the endogenous centromere position remains the hotspot for new centromere formation even in the absence of CENP‐A and CENP‐C. We next tested if partial de novo CENP‐A/C reloading was CENP‐B dependent. Upon downregulation of CENP‐B by siRNA (Appendix Fig S3H), de novo CENP‐A/C reloading was almost completely lost, as observed by IF and CUT&RUN–qPCR (Fig 6B–E), reduced to a similar level as that obtained by downregulating M18BP1 expression via siRNA (Fig 6B–D).

Altogether, our results show that, occasionally, CENP‐B can initiate CENP‐A/C deposition to maintain centromere position along with the canonical CENP‐A deposition machinery (at least M18BP1‐mediated) in cells in which CENP‐A/C was simultaneously co‐depleted.

CENP‐B initiates the CENP‐A self‐assembly epigenetic loop by recruiting CENP‐C at native human centromeres

We next wanted to identify the mechanism by which CENP‐B promotes de novo CENP‐A/C reloading at the centromere. Our results imply a model in which CENP‐B drives the initiation of the epigenetic centromere assembly loop. This can be achieved either by direct recruitment of CENP‐A via CENP‐B‐DBD (Okada et al, 2007; Fujita et al, 2015), or by direct recruitment of CENP‐A via CENP‐C that in turn interacts with components of the Mis18 complex (Moree et al, 2011; Stellfox et al, 2016). Alternatively, CENP‐B could directly promote the recruitment of the Mis18 complex (Fig EV4A), although previous evidence argued that the M18BP1 complex is insufficient to recruit endogenous CENP‐A at an ectopic site (Shono et al, 2015). To test this hypothesis, we measured the number of endogenous M18BP1 centromere foci in early G1 RPE‐1 cells following rapid depletion of CENP‐A, CENP‐C, or co‐deletion of CENP‐A and CENP‐B (Fig EV4B). CENP‐A removal or depletion of CENP‐B alone did not alter M18BP1 recruitment at centromeric regions, while CENP‐A/CENP‐B co‐depletion led to a reduction in the total number of M18BP1 foci (Fig EV4B–D). Rapid and complete removal of CENP‐C even further perturbed M18BP1 foci at most centromeres (Fig EV4C and D). Since CENP‐C depletion showed the most drastic effect, and co‐depletion of CENP‐A/CENP‐B lead to a strong, although not complete, loss of centromeric CENP‐C signal (Hoffmann et al, 2016), we favor the model that CENP‐C, but not CENP‐B, promotes M18BP1 recruitment, as previously observed (Moree et al, 2011; Dambacher et al, 2012).

Figure EV4. (related to Fig 7). Exogenously expressed CENP‐C, but not CENP‐A, reloaded at the original centromere position in absence of endogenous CENP‐A/C.

- Models of CENP‐B-induced CENP‐A reloading via (I.) initial Mis18 recruitment or (II.) initial CENP‐C recruitment.

- Schematic of the experiment analyzed in C, D.

- Quantification of M18BP1 foci in late M phase/early G1 (eG1) in both daughter cells in the indicated conditions. Each dot represents two daughter cells. Error bars show SEM. Unpaired t‐test: ****P < 0.0001.

- Representative immunofluorescence images showing M18BP1 foci in different cell lines after 24‐h IAA treatment. Cells with centromeric CENP‐A are marked with a red dashed contour line, while a yellow contour line marks cell without centromeric CENP‐A. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Illustration of the genomic make‐up of DLD‐1 cells used to test CENP‐A or CENP‐C reloading in the absence of endogenous CENP‐A/C.

- Immunoblot showing exogenous CENP‐A (left) and CENP‐C (right) expression upon addition of doxycycline (DOX) and TMP to induce CENP‐ADHFR‐mRFP or CENP‐CDHFR‐mRFP overexpression in DLD‐1 cells.

- Experimental design of experiments shown in Fig 7C–E and Appendix Fig S7H and I.

- Bar graphs showing the control of CUT&RUN–qPCR on CENP‐C antibody and primers binding to the centromere of chromosome 4 in the indicated conditions. Enrichment is measured relative to the IgG control and normalized to Alu repeats. Error bars represent SD of 3 independent experiments.

- Representative immunofluorescence image showing 24 h CENP‐AmRFP‐DHFR stability in the absence of endogenous CENP‐A and CENP‐C in G1 arrested cells.

- Experimental design of experiments shown in Fig 7F–H and Appendix Fig S7K–M.

- Representative immunofluorescence image showing CENP‐C reloading in interphase cells (nuclei are highlighted by a dashed red contour line) in the presence (control) or absence (sample) of endogenous CENP‐A/C. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Quantification of relative number of exogenous CENP‐C-positive centromeres per cell in the indicated conditions quantified on chromosome spreads.

- Bar graph showing the control of CUT&RUN–qPCR on CENP‐A antibody and primers binding to the centromere of chromosome 4 in the indicated conditions. Enrichment is measured relative to the IgG control and normalized to Alu repeats.

Source data are available online for this figure.

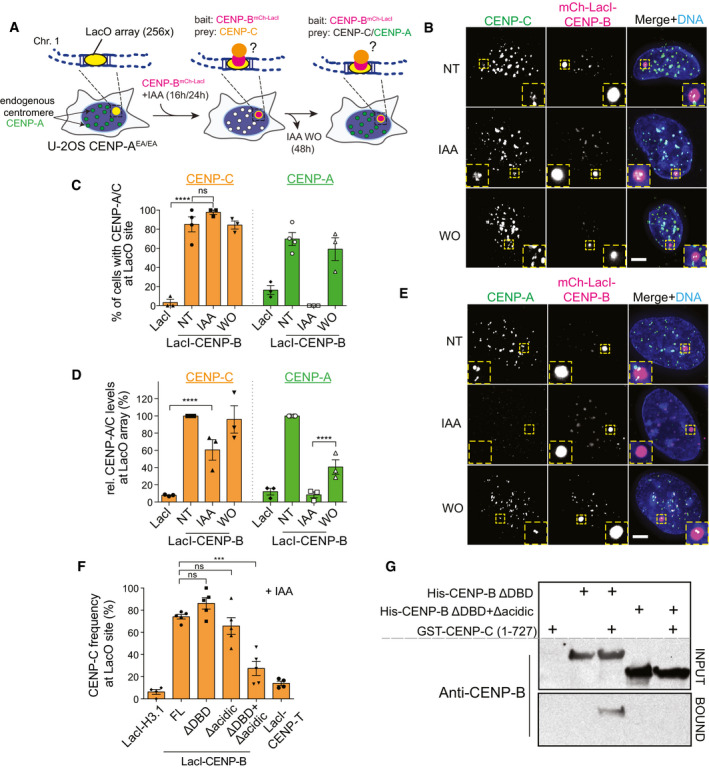

Our data emphasize that endogenous centromeric CENP‐B can initiate the epigenetic self‐assembly loop via CENP‐C recruitment independently of CENP‐A. Hence, we next dissected the temporal events that control centromere formation at endogenous CENP‐B positive centromeres (Fig 7A). To do this, we developed a system to rapidly co‐deplete CENP‐A and CENP‐C and separately induce the expression of either exogenous (e) CENP‐A or CENP‐C tagged with mRFP and a DHFR destabilization domain (Figs 7B and EV4E). The expression of ectopic eCENP‐A or eCENP‐C was placed under the control of a doxycycline‐regulatable promoter and stabilized by addition of TMP molecule (Fig EV4E and F).

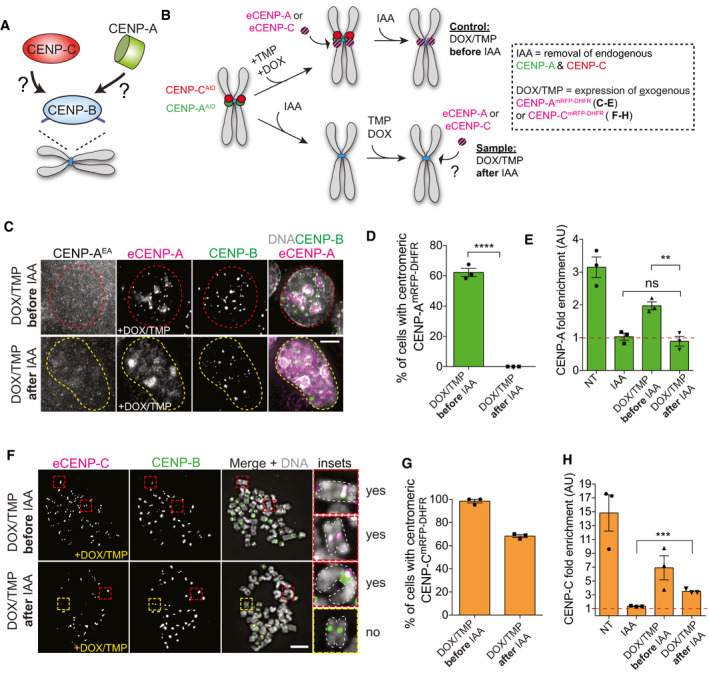

Figure 7. CENP‐B is capable to initiate the CENP‐A‐mediated epigenetic loop via de novo recruitment of CENP‐C at the native centromere.

- Schematic to illustrate the goal of this experiment.

- Schematic illustration of the experiments performed in C‐H.

- Representative immunofluorescence images showing exogenous CENP‐AmRFP‐DHFR reloading in the presence (control), but not in the absence (sample) of endogenous CENP‐A and CENP‐C. Scale bar; 5 μm. Chromosomes with centromeric CENP‐A are marked with a red dashed contour line, while a yellow contour line marks cell chromosome without centromeric CENP‐A.

- Quantification of relative number of cells showing centromeric eCENP‐AmRFP‐DHFR in the indicated conditions. Error bars represent SEM from 3 independent experiments. Each dot represents one independent experiment with at least 30 cells per condition. Unpaired t‐test, ****P < 0.0001.

- Bar plot of CUT&RUN–qPCR quantification using CENP‐A antibody and primers binding at the centromere of chromosome 4. Enrichment is measured relative to the IgG control and normalized to Alu repeats. Error bars represent SEM from 3 independent experiments. Each dot represents one independent experiment. Unpaired t‐test, **P = 0.0048.

- Representative immunofluorescence chromosome spreads showing reloading of exogenous eCENP‐CmRFP‐DHFR in the presence (control) and in the absence (sample) of endogenous CENP‐A and CENP‐C. Cells were arrested with colcemid for 3 h prior to spread. Cells with centromeric CENP‐C are marked with a red dashed contour line, while a yellow contour line marks cell without centromeric CENP‐C. Chromosomes in inset are highlighted using a white dashed line. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Quantification of relative number of cells with eCENP‐CmRFP‐DHFR in the indicated conditions. Each dot represents one independent experiment with at least 30 cells per condition. Error bars represent SEM from 3 independent experiments.

- Bar plot of CUT&RUN–qPCR results using CENP‐C antibody and primers binding at the centromere of chromosome 4. Enrichment is measured relative to the IgG control and normalized to Alu repeats. Each dot represents one independent experiment. Error bars represent SEM from 3 independent experiments. Unpaired t‐test, ***P = 0.0003.

We first tested if eCENP‐A can be loaded at the CENP‐B‐positive centromeres that lack preexisting CENP‐A and CENP‐C. We synchronized cells to be able to monitor eCENP‐A loading in G1 prior to or after endogenous CENP‐A/C removal by IAA (Fig EV4G). Surprisingly, we did not observe any eCENP‐A loading when endogenous CENP‐A/CENP‐C was removed prior to its deposition, in contrast to control cells in which CENP‐A/C removal was performed after eCENP‐A loading (Fig 7C and D). The absence of eCENP‐A loading to centromeric regions depleted of CENP‐A/C was also confirmed by CUT&RUN–qPCR (Figs 7E and EV4H). This lack of signal was only partly explained by CENP‐A reduced stability due to the absence of CENP‐C (Falk et al, 2015, 2016), as even prolonged IAA treatment (24 h) in control cells to remove endogenous CENP‐A/C did not abolish the enrichment of eCENP‐A at centromeric regions (Fig EV4G and I).

Next, we tested the capacity of eCENP‐C to be reloaded at the centromere in the absence of centromeric CENP‐A/C. Here, we used asynchronous cells (Fig EV4J) as CENP‐C loading is not restricted to early G1 (Hoffmann et al, 2016). In contrast to eCENP‐A, we found that initial depletion of endogenous CENP‐A/C did not prevent eCENP‐C loading at CENP‐B‐positive centromeres in ~60% of interphase or mitotic cells (Figs 7F and G, and EV4J–L). As previously noted (Fig 6A–E), we observed only partial centromeric eCENP‐C loading (Fig EV4L). We confirmed the ability of eCENP‐C to reload at the centromere by CUT&RUN–qPCR in the absence of CENP‐A reloading (Figs 7H and EV4M).

Altogether, our results show that CENP‐C, but not CENP‐A, can be loaded, at least partially, at centromeres that lack previously deposited CENP‐A/CENP‐C.

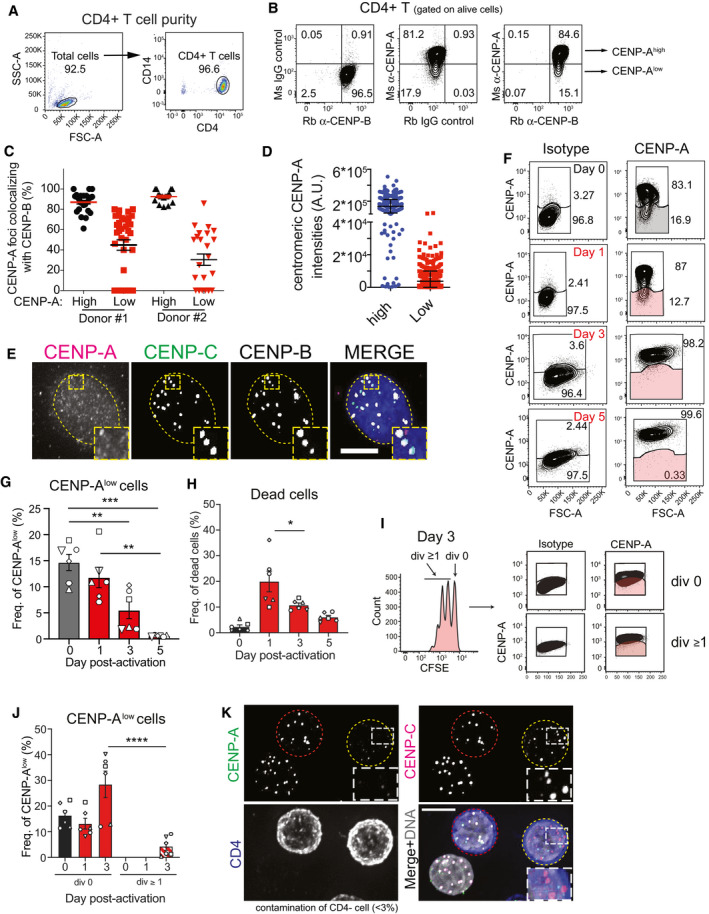

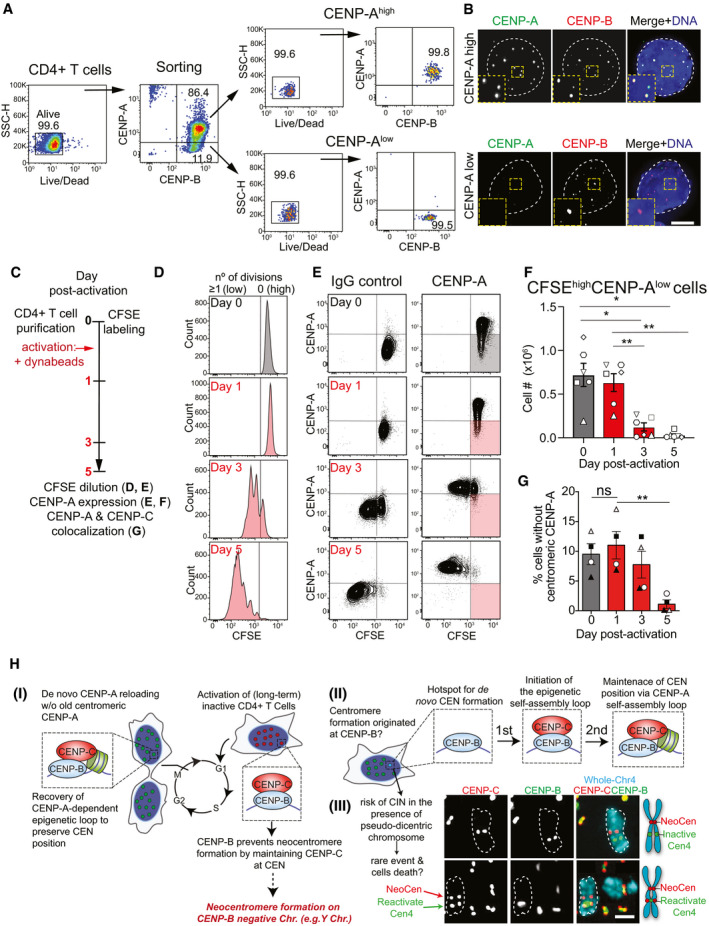

CENP‐A‐negative resting CD4+ T cells re‐assemble CENP‐A de novo upon cell cycle entry

Our results imply that CENP‐B provides memory of centromere identity. We next aimed to assess the physiological relevance of this mechanism. While dividing cells maintain CENP‐A expression, terminally differentiated non‐dividing cells lacking CENP‐A have been described (Swartz et al, 2019). Subsets of differentiated lymphocytes are quiescent in the peripheral blood from healthy individuals, and they can re‐enter the cell cycle upon activation through T Cell Receptor (TCR) activation. We hypothesized that a sub‐population of circulating T lymphocytes may contain a fraction of CENP‐A‐negative cells, and they might re‐acquire CENP‐A expression and centromere deposition upon activation. We measured the level of CENP‐A and CENP‐B in resting, non‐dividing CD14−/CD4+ T cells isolated from peripheral blood of healthy human donors (Fig EV5A). While all the analyzed CD4+ T cells were CENP‐B‐positive, two distinct populations were detected based on their CENP‐A expression, referred to as CENP‐Ahigh and CENP‐Alow (Figs 8A and EV5B). Next, we sorted CENP‐Ahigh and CENP‐Alow CD4+ T cells to investigate CENP‐A localization. While in CENP‐Ahigh cells CENP‐A colocalized with centromeric CENP‐B, in most CENP‐Alow cells CENP‐A was undetectable or barely detectable at CENP‐B‐marked centromeres (Figs 8B and EV5C and D). In contrast, CENP‐C localized at these CENP‐A‐depleted centromeres (Fig EV5E). This result prompted us to investigate CENP‐A expression and localization upon T‐cell activation (Fig 8C). To track the number of cell divisions across time, purified CD4+ T cells were labeled with the fluorescent dye CFSE (Fig 8D). In undivided cells (CFSEhigh), we observed a gradual increase in CENP‐A expression from day 1 to day 3 upon T‐cell activation (Figs 8E and EV5F), consistent with the exit from quiescence and re‐entry in the cell cycle (Figs 8D and E, and EV5F). The frequency of dead cells did not increase between day 1 and day 3 (Fig EV5H), suggesting that CENP‐Alow T cells were not lost as a result of compromised viability. In cells that had divided at least once (CFSElow, day 3 to day 5), the CENP‐A level was high and homogenous (Figs 8D and E, and EV5F). At day 3, only the remaining population that had not yet divided (div 0) contained cells expressing lower levels of CENP‐A, compared to cells that had divided (Fig EV5I and J). These results were consistent across independent blood donors (Figs 8F and EV5G and J) and were confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis (Figs 8G and EV5K). Our data thus suggest that CENP‐Alow T lymphocytes convert into CENP‐Ahigh cells upon T‐cell activation before cell division. Overall, we conclude that a physiologic sub‐population of quiescent resting human CD4+ T cells expresses CENP‐B and CENP‐C, but lacks detectable centromeric CENP‐A. Upon cell cycle entry, CENP‐A is reloaded at endogenous centromeres, in agreement with the essential role of CENP‐B/CENP‐C in the maintenance of centromere identity.

Figure EV5. (related to Fig 8). CENP‐A‐deprived CD4+ T cells are found in human blood samples but disappear upon T‐cell activation.

- Representative FACS plots showing the efficiency of total CD4+ T‐cell purification from human blood PBMCs.

- Representative FACS plots showing gating of CENP‐B-positive/CENP-A‐high and CENP‐B-positive/CENP-A‐low populations of freshly purified human CD4+z T cells based on isotype controls. Ms = mouse; Rb = rabbit.

- Graph showing CENP‐A foci identified in high or low CENP‐A expressing cell colocalizing with CENP‐B foci in two donors. Each dot represents the percentage of CENP‐A/B colocalizing in one cell. Error bar shows SEM.

- Quantification of centromeric CENP‐A level in high or low CENP‐A expressing CD4+ T cells. Each dot represents one centromere. Error bars show standard deviation.

- Representative immunofluorescence images showing CENP‐B- and CENP‐C-positive centromeres, but lacking CENP‐A in a CD4+ T cell. Nucleus is contoured by a dashed yellow line. Scale bar, 5 μm

- Representative plots showing CENP‐A expression vs. forward scatter area (FSC‐A), which determines the relative size of CD4+ T cells after activation. Gates represent the frequency of CENP‐A high and low populations in total CD4+ T (shaded gates represent CENP‐Alow cells).

- Graph representing the absolute number of CFSE‐high/CENP‐A-low CD4+ T cells during the experimental kinetics. One‐way ANOVA, multiple comparisons, n = 6 (each symbol represents a different donor). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

- Graph showing the frequency of dead cells in CD4+ T cell cultures over time. One‐way ANOVA, multiple comparisons, n = 6 (each symbol represents a different donor). Error bars show SEM. *P < 0.05

- CFSE dilution and CENP‐A expression at day 3 post‐activation. Representative FACS plots showing CENP‐A expression in CD4+ T cells that have not divided (div 0) and those that have divided once or more times (div ≥ 1), gated based on CFSE dilution. Gates in CENP‐A plots were set based on isotype control for each specific population (cells in shaded gates are CENP-A‐low CD4+ T cells).

- Graph representing the frequency of CENP‐A low cells (shaded gate in I). One‐way ANOVA, multiple comparisons, n = 6 (each symbol represents a different donor). Error bars show SEM. ****P < 0.0001.

- Representative immunofluorescence images showing CENP‐A, CENP‐C, and CD4 staining after FACS. Cells with centromeric CENP‐A are marked with a red dashed contour line, while a yellow contour line marks cell without centromeric CENP‐A. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Figure 8. Centromere identity is maintained in resting CENP‐A‐deprived CENP‐B/C positive CD4+ T cells.

- Gating strategy for the sorting of freshly purified resting human CD4+ T cells based on CENP‐A expression. Dead cells were excluded (first plot) using Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 780, and CENP‐Ahigh and CENP‐Alow cells (both CENP‐B+) were sorted (second plot). Post‐sort analysis of each population is then shown (third and fourth plots).

- Representative images of sorted CD4+ T cells with high or low CENP‐A level. The nucleus is contoured by a white dashed line. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Schematic representation of the analysis of CENP‐A expression over time in CD4+ T cells, shown in D‐G. T cells were activated with anti‐CD3/anti‐CD28-coated beads.

- Tracking of cell division by CFSE dilution. The black line separates cells that have not divided (no of div = 0, CFSE high) from those that have undergone at least one division (no of div ≥ 1, CFSE low).

- CENP‐A expression and CFSE dilution. Black lines were set based on CENP‐A isotype control and CFSE maximal staining at day 0 (cells in shaded quadrants are CFSE‐high/CENP‐A-low). One representative donor is depicted.

- Absolute number of CFSE‐high/CENP‐A-low CD4+ T cells (shaded gate in E). Symbols represent individual donors. Error bars represent SEM from 6 independent donors. One‐way ANOVA, multiple comparisons, n = 6. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

- Frequency of cells without centromeric CENP‐A determined by immunofluorescence microscopy before and post‐activation. Symbols represent individual donors, n = 4. Error bars represent SEM from 4 independent donors. Unpaired t‐test: **P = 0.0064.

- Model of the role of CENP‐B in the maintenance of centromere identity. I‐III: See text for details. In III: (top) representative image of a pseudodicentric chromosome in PD‐NC4 cells with an active (red) and inactive (green) centromere bound by CENP‐C and CENP‐B, respectively; (bottom) example of a rare centromere re‐activation in which the inactive (red) centromere gains CENP‐C binding capacity. White dashed lines contour representative chromosomes. Schematic to the right illustrates the observed CENP‐C and CENP‐B localization patterns on a chromosome.

Discussion

In this work, we identify CENP‐B as a key contributor to maintain centromere position together with CENP‐A (Fig 8HI). By preserving a critical level of CENP‐C at native centromeres, CENP‐B provides memory for maintenance of native human centromeres by promoting de novo CENP‐A assembly. This has a physiological impact in cells that have temporarily lost CENP‐A (e.g., a sub‐population of resting CD4+ T cells) where the CENP‐B/CENP‐C connection is key to preserving the original centromere identity. Additionally, under selective pressure, neocentromere‐like elements form at CENP‐B‐negative centromeres. We demonstrated that CENP‐B bound to centromeric DNA can trigger the recruitment of CENP‐C, not only at ectopic LacO site, but also at native centromeres (Fig 8HII). We show that CENP‐C is a key factor for CENP‐A loading which, subsequently, initiates the maintenance of centromere position in a CENP‐A‐dependent manner. While CENP‐C has been mainly described as the reader of the epigenetic mark CENP‐A, now we have demonstrated its capability to recognize and mark centromere position via CENP‐B and independently of CENP‐A. Moreover, we showed that CENP‐A itself, in the absence of CENP‐C, lacks this ability to reinstate centromere memory. In contrast to previous models, our observations suggest that de novo centromere formation is likely initiated by a critical level of CENP‐C rather than CENP‐A (Fig 8HII). However, our data still emphasize the importance of the centromeric self‐assembly loop to efficiently maintain centromere position for indefinite cell cycles, a function that cannot be fulfilled exclusively by CENP‐B and CENP‐C themselves. This is in agreement with the well‐studied essentiality of CENP‐A in proliferating somatic cells in all CENP‐A‐containing species studied so far (Fukagawa & Earnshaw, 2014; McKinley & Cheeseman, 2016; Stankovic & Jansen, 2017).

Our data have several implications. First, as CENP‐A also incorporates outside the canonical centromeric sites (Bodor et al, 2014; Nechemia‐Arbely et al, 2019), we propose that CENP‐B is required to prevent neocentromere formation by preserving CENP‐C at the original centromere location and favoring the maintenance of centromere identity in a CENP‐C‐dependent manner (Fig 8HI). This is even more critical in the event of CENP‐A up‐regulation, as observed in some types of cancer, although to date is still unclear how massive CENP‐A mis‐incorporation promotes the emergence of genome instability (Barra & Fachinetti, 2018). Certainly, in contrast to what has been observed in flies (Heun et al, 2006; Olszak et al, 2011), ectopic CENP‐A is unable to drive neocentromere formation in human cells. This could be explained by the lack of CENP‐C‐mediated nucleosome protection mechanism of ectopic CENP‐A during DNA replication (Nechemia‐Arbely et al, 2019) that we argue is strongly supported by CENP‐B. Furthermore, we have proven that, under selective pressure, neocentromere‐like elements can form on the CENP‐B‐deficient centromere of the Y chromosome (Fig 4).

The contribution of the CENP‐B/CENP‐C connection to centromere identity is most relevant at CENP‐A‐depleted centromeres (Fig 8HI). We identified a population of resting CD4+ T cells characterized by low CENP‐A expression with undetectable localization at centromeres (Fig 8A and B). The origin and properties of T cells lacking CENP‐A warrants further study. We hypothesize that CENP‐A loss under physiological conditions could be a consequence of prolonged cell cycle withdrawal, a feature of quiescent cells. This suggests the inability to reload CENP‐A during quiescence, a phenomenon recently described (Swartz et al, 2019). Importantly, this loss is reversible in CD4+ T cells and we find that resuming the cell cycle restores CENP‐A expression and centromere localization. In this scenario, upon cell activation, T cells are more likely to reactivate CENP‐A transcription during G2 (Shelby et al, 1997) and to reload it at mitotic exit via its canonical pathways (Zasadzińska & Foltz, 2017), as the absence of CENP‐A in the first mitosis can be tolerated (Hoffmann et al, 2016). This type of de novo CENP‐A reloading was also observed in our CENP‐AOFF/ON system using human cell lines as we found full recovery of centromeric CENP‐A level within one (Fig EV1B and C) or two cell cycles (Fig 1). This suggests the existence of a quantitative transmission mechanism, likely determined by CENP‐A expression levels, that preserves the number of CENP‐A molecules independently of the presence of previously deposited CENP‐A. In T cells, one cell cycle was sufficient to recover full and homogenous CENP‐A expression, irrespective of the initial fraction of CENP‐A‐low cells among independent donors. This demonstrates that the amount of previously deposited CENP‐A molecules is not the key determinant of total centromere CENP‐A. A complete turnover of all preexisting CENP‐A molecules has been only previously observed in holocentric organisms (Gassmann et al, 2012). Our findings further demonstrate that post‐translational modifications on preexisting centromeric CENP‐A are not essential to guide new CENP‐A deposition at the centromere in contrast to previously described models (Niikura et al, 2015, 2016).

Our results also show that endogenous CENP‐B level enables centromere formation via CENP‐C recruitment (Fig 8HII). This finding has implications for the mechanisms that drive HAC formation via CENP‐B, as we dissected the temporal events necessary for maintenance of centromere position. A previous report proposed that CENP‐B promotes HAC formation via direct recruitment of CENP‐A (Okada et al, 2007), since, to a certain extent, they stabilize each other (Fachinetti et al, 2015; Fujita et al, 2015). However, our data on ectopically tethered CENP‐B and at native centromeres show that this interaction appears insufficient to load and stabilize CENP‐A in the absence of CENP‐C (Fig 7C–E and Appendix Fig S2C–G). Importantly, CENP‐C is a key factor for centromere formation as it is both able to recruit CENP‐A via the Mis18 complex (Moree et al, 2011; Dambacher et al, 2012; Stellfox et al, 2016; Pan et al, 2017) and stabilize it (Falk et al, 2015, 2016). Interestingly, the Mis18 complex was not sufficient to mediate detectable endogenous CENP‐A assembly when tethered to an ectopic location (LacO) (Ohzeki et al, 2019), reinforcing the importance of CENP‐C to maintain centromere position. However, our data do not entirely rule out a contribution of centromere components other than CENP‐C to stabilize the Mis18 complex in human centromeres.

Finally, the existence of stably inherited pseudodicentric neocentric chromosomes—in which both the non‐repetitive neocentromere bound by CENP‐A and the inactive centromeric locus carrying satellite DNA and CENP‐B are found on the same chromosome [e.g. PD‐NC4 cells (Amor et al, 2004)]—disfavors the notion that CENP‐B initiates centromere formation. In this scenario, the presence of ectopic CENP‐B should represent a threat for the cells as it can occasionally lead to a dicentric chromosome. Indeed, we sporadically observed the spontaneous re‐activation of the inactive native centromere in PD‐NC4 cell line and the formation of a dicentric chromosome (Fig 8HIII). However, in these cells the abundance of repetitive DNA and CENP‐B at the inactive centromere was particularly low (Fachinetti et al, 2015), perhaps reducing its ability to promote centromere formation via CENP‐C recruitment. The potential to become a dicentric chromosome could further explain why the occurrence of pseudodicentric chromosomes remains a very rare event and that CENP‐B only inefficiently promotes centromere formation on HACs (Ohzeki et al, 2002; Okada et al, 2007). Interestingly, to date, 3 out of 8 cases of described pseudodicentric neocentric chromosomes in humans occur on the Y chromosome (Marshall et al, 2008) where centromere re‐activation is predicted to be less frequent due to lack of CENP‐B. Previous reports have suggested that CENP‐B is removed from non‐centromeric regions via its chaperone Nap1 (Tachiwana et al, 2013). Considering our findings, such regulation appears also to be important to prevent CENP‐B‐driven centromere formation outside of alpha‐satellite DNA.

Altogether, our data suggest cooperation of CENP‐A/CENP‐B/CENP‐C in maintenance of centromere position and function. CENP‐C, via CENP‐B, is the initiation factor for new centromere formation capable to promote de novo CENP‐A deposition, that in turn stabilizes CENP‐C in a temporal manner. What causes the heterogeneity of CENP‐B‐mediated CENP‐C recruitment remains to be identified. As the percentage of cells that reload CENP‐C doubles following ectopic CENP‐C expression (Fig 7G), it is possible that the inefficient reloading is due to low CENP‐C protein levels following IAA WO. In this regard, the importance of CENP‐C for endogenous CENP‐A loading was previously observed at ectopic chromatin‐integrated LacO sites (Hori et al, 2013; Shono et al, 2015). However, CENP‐C protein levels at these ectopic sites are tremendously higher compared to the native centromere. As protein level recovers gradually over time following IAA wash‐out, this can explain why we initially failed to identify rapid new CENP‐C loading (within 3 h) at endogenous centromeres in the absence of CENP‐A (Hoffmann et al, 2016). CENP‐C is also absent at the CENP‐B‐bound inner centromere during metaphase. Possibly, the chromatin environment or post‐translational modifications might also regulate CENP‐C recruitment. Concerning this aspect, the acidic domain of CENP‐B was recently described to function as an interface for several chromatin remodeling proteins with either chromatin compaction or decompaction activities (Otake et al, 2020). Although the precise regulation of these CENP‐B‐mediated chromatin alterations remains unclear, chromatin compaction could impair CENP‐C recruitment and thus explain partial CENP‐C recruitment.

Another question that remains to be elucidated is the role of CENP‐I in centromere formation as it was shown to recruit CENP‐A at an ectopic site (Hori et al, 2013; Shono et al, 2015) and to display an extended localization profile compared to the other CCAN proteins in a similar, but not identical pattern to CENP‐B (Kyriacou & Heun, 2018). However, in vitro assays favor the hypothesis of a cooperative binding between CENP‐I and the CCAN likely via a direct interaction with CENP‐C (Klare et al, 2015; McKinley et al, 2015; Weir et al, 2016; Pesenti et al, 2018) that in turn promotes and stabilizes centromeric CENP‐A.

Finally, our model does not exclude that CENP‐B and repetitive DNA could maintain the centromere in a manner that is independent of the direct interaction with CENP‐B and CENP‐C. A recent computational study suggested that CENP‐B induces the formation of specific non‐B DNA structure (Kasinathan & Henikoff, 2018) that could potentially facilitate CENP‐A incorporation. Interestingly, BACs containing centromeric DNA favor CENP‐A assembly in contrast to non‐centromeric DNA (Aze et al, 2016). Non‐B DNA structures are also observed at CENP‐B‐free centromeres (neocentromeres and the Y chromosome) and could explain the formation of de novo centromere on some types of DNA in a HAC formation assay (Logsdon et al, 2019). In support of this hypothesis, our data on CENP‐A reloading at the Y chromosome show that the alpha‐satellite DNA sequences provide CENP‐B independent features that favor centromere re‐formation. More studies are needed to shed light on the centromere DNA secondary structures and their possible role in centromere biology. Interestingly, in S. pombe, centromere DNA inherently destabilizes H3 nucleosomes to favor CENP‐A deposition (Shukla et al, 2018). Previous studies have also reported that CENP‐C has DNA binding activity, that could potentially promote CENP‐C loading to site of de novo centromere formation, although its DNA sequence specificity remains uncertain (Sugimoto et al, 1994; Yang et al, 1996; Politi et al, 2002; Xiao et al, 2017). Additionally, the alpha‐satellite locus bears marks of active transcription (Sullivan & Karpen, 2004) and satellite transcripts might play a direct role in centromere formation by mediating CENP‐A and CENP‐C incorporation (Bergmann et al, 2010; Chan et al, 2012; Quénet et al, 2014; Chen et al, 2015; McNulty et al, 2017; Bobkov et al, 2018). CENP‐B might play an additional role in transcript regulation possibly by competing with DNA methylation and methylated DNA binding proteins at CENP‐B boxes (Scelfo & Fachinetti, 2019). Lastly, CENP‐B was proposed to act as a chromatin regulator by directly modulating heterochromatin formation (Okada et al, 2007; Morozov et al, 2017). Indeed, the acetyltransferase KAT7 via M18BP1 has been implicated in CENP‐A deposition (Ohzeki et al, 2016).

Future studies will be important for defining the interplay among DNA sequence, transcription, and epigenetic modifications in establishing and maintaining centromere identity via CENP‐B and CENP‐C.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Cells were cultivated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Flp‐In TRex DLD‐1 cells and U‐2OS 2‐6‐3 R.I.K LacO cells (Janicki et al, 2004) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified essential medium (DMEM) medium containing 10% tetracycline free Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Pan Biotech). U‐2OS cells were cultured with 0.1 mg/ml hygromycin (Invitrogen). Immortalized hTERT RPE‐1 cells were maintained in DMEM:F12 medium containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (BioSera), 0.123% sodium bicarbonate, and 2 mM L‐glutamine.

IAA (I5148; Sigma) dissolved in ddH2O was used at 500 μM, doxycycline (1 μg/ml), TMP (10 μM), reversine (0.5 μM), colcemid (0.1 mg/ml, Roche), palbociclib (1 μM), G418TM (0.3 mg/ml, Gibco™), Flavopiridol (5 μM, Sigma), and NM‐PP1 (5 μM, Sigma). IAA was washed‐out three times using culture medium. Efficient IAA removal was ensured by first repeating the washes after 15 min and second after 30 min to allow excess compound to diffuse from cells. For DOX/TMP wash‐outs, cells were additionally detached (TrypLE™, Gibco), washed by centrifugation, and then re‐seeded on glass slides in normal culture medium.

Gene targeting