Abstract

Tragic events such as pandemics can be remembered as well as foreshadowed by works of art. Paintings by the artists Edvard Munch and John Singer Sargent (1918–19) tell us in real time what it was like to be stricken by the Spanish flu. Paintings by Edward Hopper (1940s and ’50s) foretell the lockdown and social distancing of today’s COVID-19 pandemic.

Tragic events such as pandemics can be remembered as well as foreshadowed by works of art. Paintings by the artists Edvard Munch and John Singer Sargent (1918–19) tell us in real time what it was like to be stricken by the Spanish flu. Paintings by Edward Hopper (1940s and ’50s) foretell the lockdown and social distancing of today’s COVID-19 pandemic.

Main Text

Introduction

The 2020 Lasker Medical Research Awards will not be given this year, owing to the global COVID-19 pandemic. One way to help fill this void is to reflect back on the foundational discoveries in immunology, spanning more than a century, that are now guiding current basic and clinical investigations aimed at halting the SARS-CoV-2 virus and treating infected individuals. The Lasker Foundation challenged the Pulitzer Prize-winning author and physician-scientist Siddhartha Mukherjee to tell the story of the COVID-19 pandemic in an historical context centered around major advances in immunology. In the accompanying Perspective published in this issue, Mukherjee provides a vivid and lively account, told in sweeping fashion (Mukherjee, 2020).

The essay below invites the reader to reflect back in time from a different perspective—from that of the artist and from those of us who behold and appreciate art—and to consider ways in which a terrible pandemic from a century ago foreshadows our current situation.

Cultural Legacy of Spanish Flu Overshadowed by World War I

The current COVID-19 pandemic bears an uncanny resemblance to the Spanish 1918 flu pandemic in terms of person-to-person transmission, global transmission, and frequent lethality. Over a 2-year period (February 1918–December 1920), as many as 500 million people, one-third of the world’s population, were infected with the influenza virus. The death toll was staggering, with an estimated 100 million lives lost worldwide. For comparison, this number of deaths is higher than all of the soldiers and civilians killed during World War I. Moreover, the virus killed significantly more people in 24 weeks than HIV/AIDS has killed in 40 years (Barry, 2004).

Yet, despite the human disaster of the 1918 flu pandemic, its cultural legacy was overshadowed by World War I and soon forgotten. Artists in particular were more attracted to depictions of war than of bedridden patients. And not surprisingly, there are only a few notable works of art in our museums to remind us of the suffering and devastation caused by the 1918 flu pandemic.

Edvard Munch: Remembering the Spanish Flu Before and After Recovery

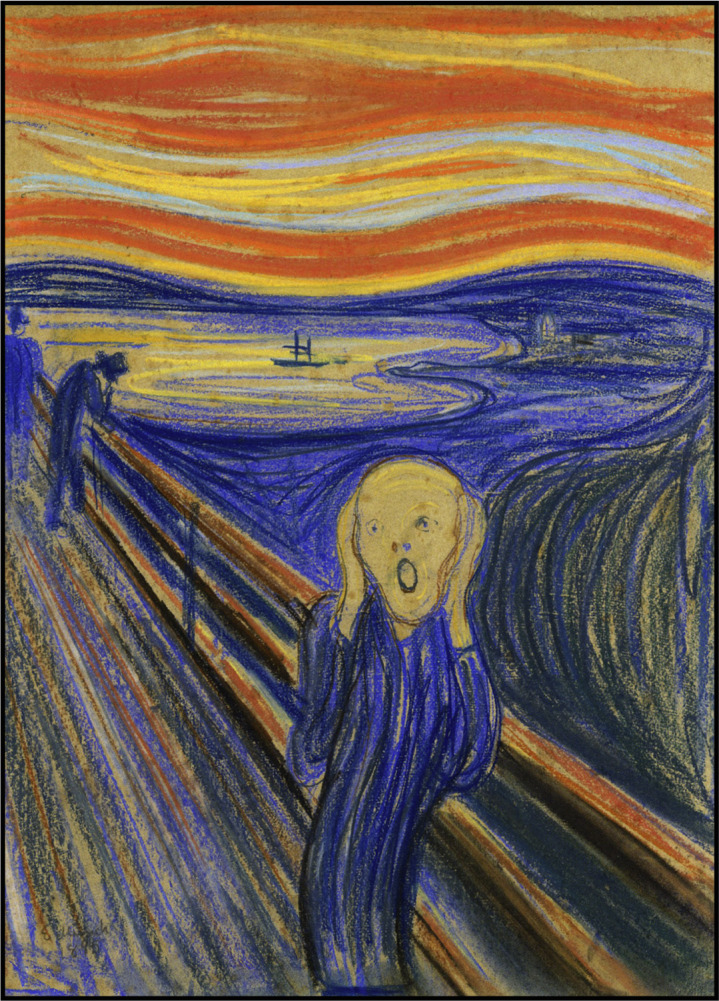

Two of the most notable works were done by the Norwegian-born, expressionist painter and printer, Edvard Munch (1863–1944). Munch is renowned for his translation of personal trauma and emotions to create pictorial scenes of various human experiences filled with discord and mystery (Steihaug et al., 2013). His most famous painting, The Scream, is one of the most iconic images in the history of art (Figure 1 ), ranking with Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Van Gogh’s The Starry Night, and Picasso’s Guernica.

Figure 1.

Edvard Munch’s Most Popular Painting

The Scream. 1895. Oil, tempera, and chalk on board. 35 × 29 in. National Gallery, Oslo.

In 1919, Munch fell victim to the flu epidemic. As a 56-year-old man in good health, he survived the episode and was inspired to depict his experience contracting and surviving the ordeal (Prelinger, 2002). The first of his two paintings, entitled Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu, shows the artist isolated and alone. He is slumped over in a wicker chair and wrapped in a sick robe and blanket (Figure 2 A). He appears emaciated, his skin is pale and possibly jaundiced, his hair is thin, and he stares at us with recessed eyes that denote disorientation and delirium. His gaping mouth, which is reminiscent of The Scream, suggests that he was having difficulty breathing. Munch painted this self-portrait while in the midst of his illness.

Figure 2.

Munch’s Two Spanish Flu Self-Portraits

(A) Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu. 1919. Oil on canvas. 59 × 52 in. National Gallery, Oslo. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

(B) Self-Portrait After the Spanish Flu. 1919–20. Oil on Canvas. 23 × 29 in. Munch Museum, Oslo. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In the second of Munch’s Spanish flu paintings, entitled Self-Portrait After the Spanish Flu, Munch portrays himself in the early stages of recovery (Figure 2B). He is standing and no longer in his wicker chair, which is shown empty at the back of the room. Color has returned to his sallow face, the presumed jaundice has gone, he has let his beard grow, and he has shed his sick robe for his customary green suit. But the deep red color encircling his puffy eyes suggest profound despair and exhaustion generated by his illness.

John Singer Sargent: Remembering the Spanish Flu while Recuperating in a World War I Army Tent

A third notable work of art that provides a contemporaneous firsthand experience of the 1918 flu pandemic was done by the Italian-born American artist John Singer Sargent (1856–1925). Sargent was the leading portrait painter of his generation, creating more than 900 oil paintings and 2,000 watercolors. Many of his subjects for portraits were famous artists, authors, politicians, and businessmen such as Claude Monet, August Rhodin, Robert Louis Stevenson, Theodore Roosevelt, and John D. Rockefeller (Herdrich, 2018). His best and most famous painting, entitled Portrait of Madame X, did not involve a well-known celebrity but rather a young French exotic beauty who was dressed in a suggestive off-the-shoulders, long black gown with a plunging neckline (Figure 3 ). When first shown in Paris in 1884, the painting created a scandal and caused a temporary setback to Sargent’s career, though ultimately it established his reputation, especially in England where he became a highly sought-after artist.

Figure 3.

John Singer Sargent’s Most Popular Painting

Portrait of Madame X. 1884. Oil on canvas. 95 × 43 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

In 1918, the British War Memorials Committee commissioned Sargent to work as a war artist with the task of creating sketches depicting British and American troops in joint combat. While working in Northern France, he caught a bad case of the flu and spent the next week recovering in a hospital tent that included a mixture of some soldiers recovering from war wounds with others recovering from the flu (Chorba and Breedlove, 2018). While on his sick bed, Sargent created a watercolor depicting the interior of the hospital tent, entitled Interior of a Hospital Tent (Figure 4 ). A khaki-brown canopy hangs down from the ceiling of the tent, below which is a line of military cots covered with blankets that are either red or brown. The different colors indicate whether the patient was contagious (red) or not (brown). In the fourth red cot, a soldier (possibly Sargent himself) is propped up on pillows reading. Beyond him, there are four or five brown cots with wounded soldiers. Sargent describes his nights in the tent as “horrific” and ”fitful,” owing to the “groans” of the wounded and the “coughing” of the infected. Singer’s watercolor, which is exhibited in the permanent collection of the Imperial War Museum in London, is a unique contribution that offers a frontline glimpse of the two concurrent conflicts occurring at the same time − the 1918 flu pandemic and World War I.

Figure 4.

The Concurrent Conflicts of 1918: Spanish Flu and World War I

John Singer Sargent. Interior of a Hospital Tent. 1918. Watercolor over pencil on paper. 16 × 21 in. Imperial War Museum, London. © IWM.

Edward Hopper: Foreshadowing the Social Isolation of the COVID-19 Pandemic

No artist has captured the social alienation and isolation of ordinary people coping with the stresses of modern life like Edward Hopper (1882–1967), America’s most important realist painter of the 20th century (Levin, 1980; Berman, 2007). Hopper’s popularity stems from his distinct style of painting images perfectly and realistically combined with his unique portrayal of people who sit alone in bleak diners, motel rooms, and theaters or who stare out of the bay windows of their apartments. Hopper’s masterly use of light and shadow is key to creating the mood of disconnection and emotion of loneliness that engenders the mystery and intrigue that attracts viewers to his paintings. A prominent art critic refers to Hopper as “the visual bard of American solitude” (Schjeldahl, 2020).

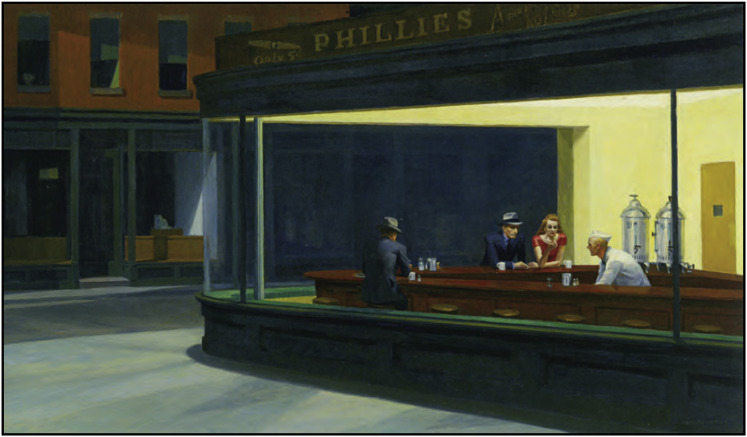

Hopper’s most famous work, entitled Nighthawks, is one of the most recognizable and reproduced paintings in the history of art (Figure 5 ). The picture, which was begun just days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, depicts an all-night diner in which three customers and a waiter are hunched over a cherry-wood countertop. All four are preoccupied with their own problems and trapped in their own thoughts. The scene is viewed through the diner’s large plate glass window, creating the illusion of an aquarium in which the four night owls are displayed. An eerie neon light spills out from the inside the diner, illuminating the dark and deserted street. What makes the painting so memorable is that it epitomizes the reality of modern life in which people living in large cities often feel isolated and unable to connect even though they are surrounded by millions of people.

Figure 5.

Edward Hopper’s Most Popular Painting

Nighthawks. 1942. Oil on canvas. 33 × 60 in. Art Institute of Chicago.

It is not surprising that within the last 6 months Hopper has been anointed by magazine writers, newspaper journalists, and internet bloggers as the artist of the COVID-19 outbreak (Jones, 2020; Schjeldahl, 2020; Wullschläger, 2020). More than any other artist, his work best speaks to the spirit of the pandemic’s quarantine culture. Two of Hopper’s oil paintings are especially noteworthy in this regard. One painting dramatically foreshadows lockdown, and another foreshadows social distancing, the two dominant practices of the current pandemic that are necessary to minimize spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

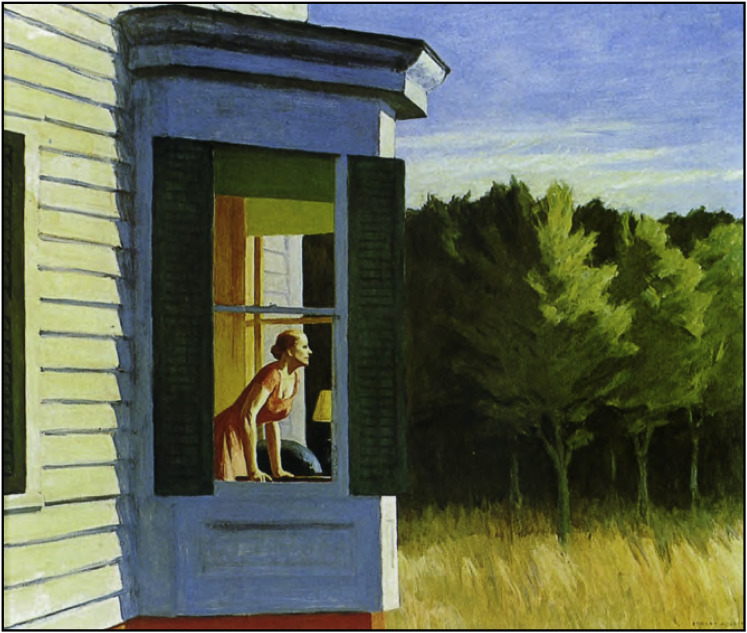

In the painting entitled Cape Cod Morning (1950), a woman gazes out of the bay window, her arms tense and her grip locked tight on the table in front of her (Figure 6 ). Her focus is forward and to the outside world, yet she seems imprisoned in her own home, anxiously staring toward an uncertain future and hoping that the lockdown will end soon.

Figure 6.

Foreshadowing the Lockdown of COVID-19

Edward Hopper. Cape Cod Morning. 1950. Oil on canvas. 34 × 40 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC. © 2020 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

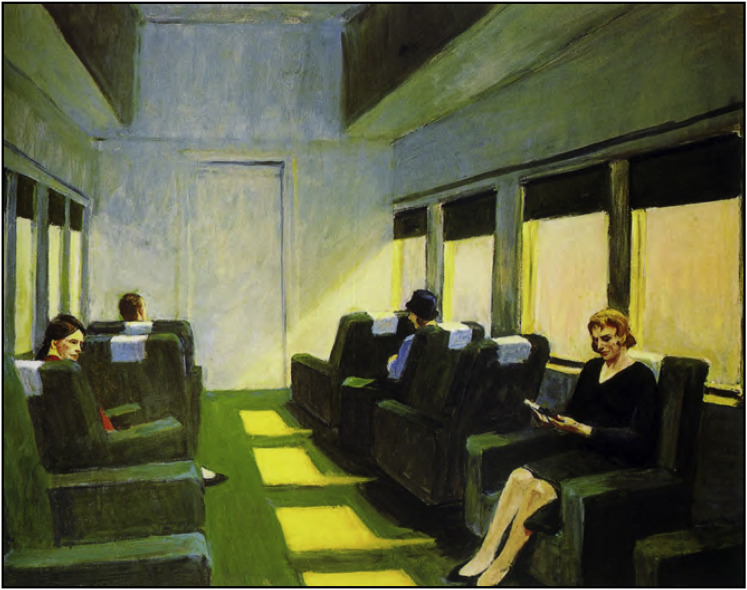

Traveling by train or airplane is typically conducive to conversations and interactions among the passengers. But that is not the case in Hopper’s painting entitled Chair Car (1965), in which four travelers are shown inside a commuter train (Figure 7 ). The inside space is dreary with no decorations. The travelers appear isolated from one another, each lost within his or her own world. The painting evokes a feeling of cold unpleasantness that anticipates our current practice of social distancing.

Figure 7.

Foreshadowing the Social Distancing of COVID-19

Edward Hopper. Car Chair. 1965. Oil on canvas. 40 × 50 in. © 2020 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Art as a Diary of Human Tragedies and a Reflection of the Artist’s Mind

The COVID-19 pandemic is shaping up to be a defining event of the 21st century. How will it be remembered by artists? How will their paintings and prints depict the human emotion and tragedy resulting from the suffering, death, and beleaguered time brought about by the SARS-CoV-2 infection surge?

In the history of art, one of the most striking examples of an artwork that captured the emotions of a specific human tragedy is a painting by the Spanish romantic artist Francisco Goya (1746–1826) entitled The Third of May 1808. This work, which Goya began soon after the event, expresses his outrage at Napoleon’s soldiers for their brutal treatment of a group of unarmed Spanish civilians (Figure 8 ). The painting depicts two clusters of men. On the right stands the French firing squad that conveys the impression of a bloodthirsty machine. On the left stand the defenseless Spanish captives, half of whom lay dead in pools of blood and the other half terrified as they face the firing squad awaiting execution. The radiant lantern allows the soldiers to execute their gory work before the sun comes up. The man in the white shirt stretching out his arms as if on a crucifix is reminiscent of Christ and is symbolic not only of the rebels but also of the human condition. Goya’s depiction of the bloody trauma is so shocking that many museum goers find the painting impossible to view.

Figure 8.

Goya’s Revolutionary Portrayal of a Tragic Event

Francisco Goya, The Third of May 1808. 1814. Oil on canvas. 106 × 137 in. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Art historians consider Goya’s painting to be one of the first paintings of the modern era in that it departed radically from classic history paintings of Christian art and depictions of war (Licht, 1979). The renowned art historian Kenneth Clark proclaimed The Third of May 1808 to be “the first great picture which can be called revolutionary in every sense of the word, in style, in subject, and in intention” (Clark, 1961). Goya’s work inspired many famous anti-war paintings based on real-life tragic events, including Édouard Manet’s Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867–69) and Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937) and his later work Massacre in Korea (1951).

The Third of May 1808 is the gold standard for originality against which all future paintings of tragic events should strive to achieve. Only time will tell if artists who experience COVID-19 firsthand will measure up to Goya’s standard and create new ways to tell the tragic story of the pandemic.

References

- Barry J.M. Penguin Books; 2004. The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. [Google Scholar]

- Berman A. 2007. Hopper: The supreme American realist of the 20th-century. Smithsonian Magazine.https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/hopper-156346356/ [Google Scholar]

- Chorba T., Breedlove B. Concurrent conflicts - the Great War and the 1918 influenza pandemic. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018;24:1968–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Clark K. Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1961. Looking at Pictures. [Google Scholar]

- Herdrich S.L. Rizzoli Electa; 2018. Sargent: The Masterworks. [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. 2020. “We are all Edward Hopper paintings now”: is he the artist of the coronavirus age? The Guardian.https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/mar/27/we-are-all-edward-hopper-paintings-now-artist-coronavirus-age [Google Scholar]

- Levin G. W.W. Norton & Co.; 1980. Edward Hopper: The Art and the Artist. [Google Scholar]

- Licht F. Palgrave Macmillian; 1979. Goya, the Origins of the Modern Temper in Art; p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S. Before Virus, After Virus: A Reckoning. Cell. 2020;183:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.042. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelinger E. Yale University Press; 2002. After the Scream: The Late Paintings of Edvard Munch. [Google Scholar]

- Schjeldahl P. 2020. Edward Hopper and American Solitude. The New Yorker.https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/06/08/edward-hopper-and-american-solitude [Google Scholar]

- Steihaug J.-O., Guleng M.B., Sauge B. Skiva Rizzoli; 2013. Edvard Munch: 1863-1944. [Google Scholar]

- Wullschläger J. 2020. Edward Hopper: the master of urban isolation in a new online show. Financial Times.https://www.ft.com/content/c51c1c7c-8474-11ea-b872-8db45d5f6714 [Google Scholar]