Abstract

Introduction

Expert knowledge is critical to fight dementia in inequitable regions like Latin American and Caribbean countries (LACs). However, the opinions of aging experts on public policies’ accessibility and transmission, stigma, diagnostic manuals, data‐sharing platforms, and use of behavioral insights (BIs) are not well known.

Methods

We investigated opinions among health professionals working on aging in LACs (N = 3365) with regression models including expertise‐related information (public policies, BI), individual differences (work, age, academic degree), and location.

Results

Experts specified low public policy knowledge (X2 = 41.27, P < .001), high levels of stigma (X2 = 2636.37, P < .001), almost absent BI knowledge (X2 = 56.58, P < .001), and needs for regional diagnostic manuals (X2 = 2893.63, df = 3, P < .001) and data‐sharing platforms (X2 = 1267.5, df = 3, P < .001). Lack of dementia knowledge was modulated by different factors. An implemented BI‐based treatment for a proposed prevention program improved perception across experts.

Discussion

Our findings help to prioritize future potential actions of governmental agencies and non‐governmental organizations (NGOs) to improve LACs’ dementia knowledge.

Keywords: behavioral insights, data‐sharing platforms, diagnosis manuals, expert knowledge, Latin American and Caribbean countries, public policy, stigma

1. BACKGROUND

Expert knowledge is a powerful vehicle for fighting dementia, particularly in regions with strong inequities and underserved populations such as Latin American and Caribbean countries (LACs). 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Health professionals working in aging represent a critical sector of society for developing adequate diagnosis, care, and research. Their opinions and beliefs are powerful forces that drive future impact. 6 Although limited in the region, 7 , 8 , 9 accessibility and transmission of public policies are critical components of expert knowledge. 10 , 11 Knowledge transmission can also address social barriers such as stigma, 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 and can be instrumentalized to enhance clinical care and treatment via the use of diagnostic manuals and data‐sharing platforms. 9 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 The use of innovative knowledge, such as behavioral insights (BIs), are recent tools for health systems in general, 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 and in the aging and dementia fields in particular. 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 How these paths of expert knowledge affect the diagnosis and treatment of dementia in LACs is not well known; the expert opinions of health practitioners in the field of aging have not yet been systematically assessed regarding these issues. In this study, we investigated different dimensions of expert knowledge of health professionals in LACs, including knowledge of public policies, barriers to knowledge and to their implementation, and tools that impact clinical practice, as well as BI applied to dementia.

Access and transmission of specific public policies to fight dementia influence the success of any national program being considered a priority. 10 However, access to policies seems to be limited in the general population, including health care professionals. 7 , 8 The medical and scientific literature is also restricted in LACs, 7 and the dynamics of the health care system generate barriers to knowledge. 11 Policies in the region are heterogeneous and limited. 2 Beyond this available evidence, there is no reporting about access and transmission of public policies of dementia across LACs. Although intuitively attributable to limited access and transmission of public policy knowledge from the government to the public, no evidence from experts in the field has yet been reported. Understanding field experts’ barriers to knowledge will be critical because advances in dementia care are most likely to be developed by this sector of the population. Furthermore, field experts are the most likely individuals to communicate relevant policies to their patients, representing a critical inroad to expanding regional dementia knowledge.

One of the main barriers to implement available knowledge is stigma. 12 However, most of the research on stigma comes from high‐income countries (HICs). 12 Some country‐level evidence in LACs suggests that stigma around dementia is high in the region. 13 , 14 , 15 Moreover, Hispanic populations are more likely to hold stigmatized beliefs about dementia. 16 However, no previous regional reports have assessed the systematic opinion of professionals working in the field. Practical tools to disseminate expert knowledge, such as manuals 9 , 17 providing guidelines and orientation for dementia diagnosis, as well as data‐sharing platforms (Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, ADNI; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network, DIAN; The Global Alzheimer's Association Interactive Network, GAAIN) 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 that promote research capabilities, are valued instruments. However, the use of these tools at a regional level is restricted in LACs. 24 Most international registries for dementia do not include LACs. 9 Moreover, there is not considerable knowledge regarding the preferences of health care professionals for these tools in the region.

Bis, or nudges—understanding how individuals and systems behave in the current setting—enable practical knowledge to be applied to enhance human decision‐making and to promote behavioral change that results in a better outcome. BIs are widely applied to health care settings, 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 including in chronic diseases, aging, and dementia. 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 However, these tools are not well known, with only anecdotal use in LACs. 33 , 34 The opinion of health care professionals regarding the efficiency, usefulness, and real impact of BI in dementia, particularly in LACs, is unknown.

To tackle these unanswered questions, we developed a large survey that was applied to 3365 health care professionals working in aging across LACs. We collected professional opinions about knowledge of dementia, including access to and transmission of public policies, barriers due to stigma, need of diagnostic manuals and data‐sharing platforms, as well as the opinion and impact of BIs in dementia assessment programs. To identify the largest barriers to dementia knowledge in LACs, we implemented different models to assess the impact of expertise‐related information (knowledge of public policies, knowledge of BIs, experience), individual differences (work background, age, academic degree), and location (region and country levels within LACs) on dementia knowledge. We also assessed a BI treatment for effects in the same group of professionals as an early investigation into the utility of BI as a tool for enhancing access to dementia knowledge in this region.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

The final sample comprised 3365 individuals, with a mean age of 52.72 (SD = 14.44), 61.3% of which were male. With regard to response rate, only complete surveys from professionals working in aging across LACs were included from an initial database of >4000 individuals. All participants were professionals and members of Intramed (www.intramed.net), an online portal that congregates a large community of health care professionals and facilitates the exchange of research and clinical knowledge. The sample included health care professionals working in aging from different specialties and educational backgrounds representing 19 countries (see below). All individuals participated voluntarily by accepting an invitation sent through the Intramed newsletter and gave informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki by pressing an “I agree” button beneath an explanatory letter. The institutional ethics committee approved all aspects of this study.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: Authors reviewed the literature using traditional sources (PubMed). Surveys about dementia in Latin American countries (LACs) with non‐exhaustive and anecdotal information have been reviewed. In addition, surveys about the knowledge of dementia have been assessed in other regions. These publications were relevant to assess different aspects of aging experts’ opinions about dementia knowledge across LACs.

Interpretation: Our large survey of experts' opinions (N = 3365) indicated a lack of knowledge of dementia in LACs at different levels. Experts specified low accessibility and transmission of public policies. Stigma was considered a pervasive phenomenon, and participants highlighted the need for regional diagnosis manuals and data‐sharing platforms. Most participants declared not having knowledge of behavioral insights (BI). Finally, treatments based on BI interventions induced higher perceived impact.

Future directions: Results may inform the development of specific governmental and non‐governmental organization (NGO) programs in the region to improve a knowledge‐to‐action framework for diagnosis, research, and intervention on dementia.

2.2. Survey

The survey (Table 1) collected professional opinions about dementia knowledge based on the domains described earlier. In addition, to test different BI treatment strategies, the survey's last section required professionals to read a public program about aging presented in different formats and then rate aspects of perceived interest. Data were collected using a web‐based tool from March 2018 to April 2019. We extracted several outcome (dependent) variables (Supplementary Section S1) based on questions related to the following areas: (a) policies of dementia (public policy accessibility and transmission; “public policy knowledge index” [PPKI] based on the participant's degree of knowledge on health public policies), (b) barriers and tools (stigma; diagnostic manual; data‐sharing platform), and (c) BI (BI Knowledge, efficiency, and usefulness; BI Index [BII], based on the participant's degree of knowledge about BI).

TABLE 1.

Predictor variables

| Predictor variables and questions |

|---|

| Sector |

| Q: Do you work in the public or private sector? |

| A: Public/Private/Both/I don't work |

| Experience |

| Q: How long (years) have you been working in the aging field of health or social development? |

| A: Less than 2 years/Between 3 and 6 years/Between 6 and 10 years/More than 10 years |

| Academic Degree |

| Q: What is your highest academic degree? |

| A: Doctoral degree/Master's degree/Medical Specialization/Hospital Concurrence/University or Professional degree/Associate degree/Bachelor's degree/Technicature/No formation in this subjects. |

| Age |

| Q: How old are you? |

| A: Age (in years) |

| Country/Region |

| Q: In what country do you live? |

| A: Country |

| Public Policy Knowledge Index (PPKI, this variable was also used as a outcome variable) |

The following items from the survey were considered as predictor variables to generate regression models.

We also compared four BI treatments and their effect on three measures of influence. We developed a description of a public program to prevent violence against older adults with descriptive characteristics similar to those found in existing programs in LACs. The control message included basic information related to the program (goals, characteristics of the program and how it is implemented). To design the treatment messages, the “Easy, Attractive, Social and Timely” framework (EAST) from the BI Team 35 was used. The first treatment (simplification) presented the same content as the control message but was simplified for easier reading with the use of bullet points, colloquial language, and informative subtitles. The second treatment (social norm) presented the simplified content plus a message of social normalization, referencing the participation of other professionals in the program and its positive impact. For the last treatment (social norm and visual information), related photos were added to the simplified, normalized content to increase the impact of the transmission. We then evaluated the effect of the four treatments for their influence on contact (interest in being contacted), impact (of the program), and clarity (how clear is the message). Translations of the interventions are provided in Supplementary Material 1. The questions related to the treatment effects are provided in Supplementary Section S1.

We considered several predictors (Table 1) for their impact on different dependent measures, including work context (private, public, or both), experience (years in the field), academic degree, age, country, and PPKI (measured as an outcome variable and also used as a predictor in some models).

2.2.1. Data analysis

All data analysis was conducted in R. 36 The information about work background on aging was obtained from both the Intramed participants’ profiles and explicit questions in the survey. Only those surveys with both sources demonstrating experience in aging were included. Three different geographical levels (locations) were considered: (1) Latin America level, by including all data; (2) sub‐regional level, categorizing data in LAC‐South (Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Venezuela, Uruguay) or LAC‐North (Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama); and (3) country level from LAC‐South and LAC‐North, including participants from Mexico and Argentina (which have the largest numbers of participants in the analyzed cohort). See Supplementary Table S1 for details. We created different scores for academic degree, experience, and sector (public, private or both), as well as composite scores (for PPKI, BII) as detailed in Supplementary Section S2.

2.2.2. Models

For every dependent variable (Supplementary Section S1), a Pearson chi‐square test for Count Data was performed. Regression models were also fit for every item, on every location (Latin America, sub‐region and country). All of the regression models included the following predictor variables: sector (public, private), age, academic degree, experience degree, and PPKI. Models also included predictors for region or country when pertinent. Analyses of BI treatments additionally included the intervention type variable as a predictor. For BI knowledge, efficiency, usefulness, and BII, a binary logistic regression was conducted with a likelihood ratio test to assess the difference between the null deviance and the residual deviance. 37 For ordinal categorical variables (accessibility and transmission, stigma, diagnostic manuals, data‐sharing platform, BI treatments), we implemented ordered logistic regression models with P‐values calculated by comparing the t‐value against the standard normal distribution. Model performance was evaluated with Lipsitz goodness‐of‐fit test for ordinal logistic models. 38 Where non‐significant models were obtained, stepwise selection was conducted to check whether a better model would reduce variance. With this method, any imbalance in categories for predictor variables (ie, different sample sizes of countries) results in wider confidence intervals, but does not affect the reliability of the model itself. 38 We established a significance threshold of P ≤ .05, and trends were also reported. See Supplementary S3 for additional details on data analysis.

3. RESULTS

The sample was composed primarily of physicians of different specialties (93.16% physicians) and other professionals (0.03% speech therapists, 0.06% technicians, 0.12% administrators, 0.15% kinesiologists, 0.18% nutritionists, 0.3% biochemists, 10.3% dentists, 0.33% pharmacists, 1.46% psychologists, 1.72% nurses, and 2.20% from other disciplines). The sample included participants from 19 LACs (Argentina, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Uruguay, Chile, Paraguay, Bolivia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Cuba, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panamá, República Dominicana, and Venezuela). See Supplementary Table S1 for participants’ distribution across countries. The education level of participants ranged from technicians (0.51%), certificates (2.82%), tertiaries (2.97%), undergrads (25.79%), post‐graduate specialization (41.69%), master's degree (11.98%), PhDs (7.96%), and hospital interns (2.23%) to not having any education in related fields (4.04%). In terms of work experience, 4.93% presented <2 years of experience, 22.26% had between 2 and 5 years, 10.64% between 6 and 10 years, and 73.16% >10 years. With regard to work sector, 0.86% did not work, 13.43% worked in the private sector, 21.99% worked in the public sector, and 63.71% worked in both. See Table 2 for demographic characteristics of the sample.

TABLE 2.

Participant's demographic data, work experience, and educational background

| Region | Sex (% male) | Age | Experience (%) | Academic degree (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <2 y | Between 3 and 6 y | Between 6 and 10 y | >10 y | Technicians | Certificates | Tertiaries | Undergrads | Post‐graduate specialization | Master's degree | PhD | Hospital interns | No degree reported | |||

| LA | 61.3 | 52.72 ± 14.44 | 4.93 | 11.26 | 10.64 | 73.17 | 0.51 | 2.82 | 2.97 | 25.79 | 41.69 | 11.98 | 7.96 | 2.23 | 4.04 |

| LAC North | 53.64 | 50.05 ± 13.47 | 4.16 | 13.72 | 12.2 | 69.91 | 0.28 | 3.97 | 0.19 | 28.48 | 35.1 | 16.65 | 10.97 | 1.23 | 3.12 |

| LAC South | 65.07 | 53.97 ± 14.71 | 5.33 | 10.18 | 10.00 | 74.49 | 0.57 | 2.33 | 4.32 | 24.71 | 44.8 | 9.69 | 6.48 | 2.73 | 4.36 |

| Mexico | 55.14 | 52.1 ± 13.13 | 3.74 | 9.5 | 11.37 | 75.39 | 0.31 | 4.83 | 0.16 | 31.00 | 40.03 | 15.42 | 4.21 | 0.78 | 3.27 |

| Argentina | 77.95 | 58.29 ± 13.82 | 3.39 | 6.11 | 7.63 | 82.87 | 1.02 | 1.95 | 3.22 | 21.97 | 51.82 | 7.29 | 5.51 | 3.31 | 3.9 |

3.1. Public policy knowledge

3.1.1. Public policy accessibility

Most participants reported that accessibility of public policies regarding dementia is low (“Poorly accessible,” “Not at all accessible”) rather than high (“Very accessible,” “Quite accessible”). At the LAC level, the differences between the proportions of responses in each category (“Don't know”: 175/5.5%, “Not at all accessible”: 218/6.86%, “Poorly accessible”: 1826/57.44%, “Quite accessible”: 791/24.88%, “Very accessible”: 169/5.32%) was significantly different (X2 = 3217.14, df = 4, P < .001). This finding was consistent when combining responses into bins for low (2044/68.04%) versus high (960/31.96%, X2 = 391.16, df = 1, P < .001). Significant effects were similarly identified at both the regional and country levels (see also Supplementary data, section S4). See Figure 1I

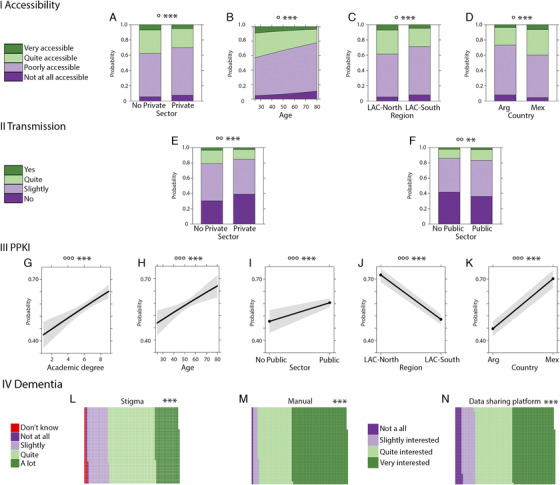

FIGURE 1.

Dementia public policies in Latin America. I Accessibility. (A) Probability of response frequency regarding accessibility by sector. (B) Probability of response frequency regarding accessibility by age. (C) Probability of response frequency regarding accessibility and region. (D) Interaction of probability of response frequency of accessibility by country. II Transmission. (E) Probability of response frequency regarding transmission by private sector. (F) Probability of response frequency regarding accessibility by the public sector. III PPKI (public policy knowledge index). (G) Probability of response frequency regarding high PPKI by academic degree. (H) Probability of response frequency regarding high PPKI index by age. (I) Probability of response frequency regarding high PPKI by the public sector. (J) Probability of response frequency regarding PPKI by public region. (K) Probability of response frequency regarding PPKI by country. IV Aging. (L) Proportion of responses about aging stigma. (M) Proportion of responses about interest in aging and dementia manual. (N) Proportion of responses about interest in a data‐sharing platform. Significance (P values): effects significance (*: P ≤ .1, **: P ≤ .05, ***: P ≤ .01), model significance (°: P ≤ .1, °°: P ≤ .05, °°°: P ≤ .01). Academic degree: 1: no reported education, 2: technicians, 3: tertiaries, 4; certificates, 5: undergrads, 6: hospital interns, 7: post‐graduate specialization, 8: master's degree, 9: PhD

Regression analyses using all predictors of interest were not significant, suggesting that low accessibility to public policies occurs independent of any other modulatory effect. However, the resulting model using stepwise selection identified a trend at the regional level (LR = 15.15, df = 9, P = .09). This model included the predictors of region, private sector, and age (Supplementary Table S2) and showed significant negative effects suggestive of lower accessibility in LAC‐South, the private sector, and with older age.

The resulting model using stepwise selection at the country level also presented a trend (LR = 15.69, df = 9, P = .07). This model included the predictors: country, private sector, academic degree, and PPKI (Supplementary Table S3). Significant effects included lower accessibility for the private sector and higher accessibility for Mexico. This is in accordance with the effects found at the regional level.

3.1.2. Public policy transmission

The quality of transmission by the Government of public policies related to dementia was predominantly considered low (“No,” “Slightly”) rather than high (“Quite,” “Yes”) quality. At the LAC level, we identified significant differences in transmission ratings (“Not applicable”: 1.05%, “No”: 36.72%, “Slightly,” 45.90%, “Quite”: 13.66%, “Yes”: 2.67%; X2 = 2507.71, df = 4, P < .001). These findings were corroborated when combining responses for low (83.51%) and high (16.49%) quality only (X2 = 1350.26, df = 1, P < .001). Similar results were detected at the regional and country levels (see Supplementary section S5).

Regression models including all predictors of interest were not significant, suggesting that low transmission occurs independent of any other modulatory effect. Performing stepwise selection, a model with a statistical trend was found at the LAC level (LR = 17.03, df = 9, P = .05). The model included predictors for both the public and private sector (Supplementary Table S4). Significant effects suggested that the public sector was associated with a higher quality transmission, whereas the private sector was associated with a lower quality transmission. (See Figure 1II.)

3.1.3. Public policy knowledge index (PPKI)

Significant models were obtained for every level of geographical region (Figure 1III). At the LAC level, the significant model (X2 = 41.27, df = 5, P < .001), showed that a higher PPKI was associated with the public sector and higher academic degree (Supplementary Table S5). At the sub‐regional level (X2 = 137.75, df = 6, P < .001) the same effects were detected, except that older age was also associated with a higher PPKI, and LAC‐South was associated with lower PPKI values (Supplementary Table S6). Finally, at the country level, the model (X2 = 87.14, df = 6, P < .001) showed that higher PPKI values were associated with the public sector, older age, higher academic degree, and being from Mexico (Supplementary Table S7). All models converged to the same notion that higher levels of PPKI were mainly associated with the public sector, having a higher academic degree, having an older age, and residing in LAC‐North.

3.2. Knowledge about barriers and tools

3.2.1. Stigma

Most participants answered that there is a high (“Quite,” “A lot”) rather than low (“Not at all,” “Slightly”) stigmatization related to age and dementia. At the LAC level, there was a significant difference between responses (X2 = 2636.37, df = 4, P < .001; “Don't know”: 2.02%, “Not at all”: 1.52%, “Slightly”: 21.60%, “Quite”: 49.51%, “A lot”: 25.25%), which was corroborated when comparing low (23.60%) versus high (76.40%) response types (X2 = 919.35, df = 1, P < .001). These effects were replicated at both the regional and country level (Supplemental S6). At the regional level, although the model was significant (LR = 17.91, df = 9, P = .04), no significant contributor was identified (Supplementary Table S8), suggesting that stigma is a pervasive effect that is not being modulated by any specific predictor. (See Figure 1IV.L.)

3.2.2. Manual

Most participants reported having a high (“Quite interested,” “Very interested”) rather than low (“Slightly interested,” “Not at all”) interest in a manual about dementia. At the LAC level, responses presented significant differences (X2 = 2893.63, df = 3, P < .001) in their count (“Not at all”: 1.55%, “Slightly interested”: 5.14%, “Quite interested”: 35.10%, “Very interested”: 58.2%), corroborated when combining them into low (6.69%) versus high (93.31%, X2 = 2525.18, df = 1, P < .001) response types. These effects were replicated at the regional and country levels (Supplemental S7). No significant regression models were identified. (See Figure 1IV.M.)

3.2.3. Data‐sharing platform

Most participants were interested in data‐sharing platforms for dementia, as more responses reporting high (“Quite interested,” “Very interested”) rather than low (“Not at all,” “Slightly interested”) interest were reported. At the LAC level, significant (X2 = 1267.5, df = 3, P < .001) differences between responses (“Not at all”: 8.39%, “Slightly interested”: 13.61%, “Quite interested”: 37.21%, “Very interested”: 42.79%) were found, consistently observed when combining low (20%) and high (80%, X2 = 1211.4, df = 1, P < .001) response types. These effects were replicated at regional and country levels (Supplemental S8).

Significant regression models were found at the LAC and location levels. For the LAC model (LR = 24.92, df = 9, P < .001), higher interest in a data‐sharing platform was associated with a higher PPKI and younger age (Supplementary Table S9). The sub‐regional model (LR = 18.78, df = 9, P = .03) identified the same effects as the LAC model, and higher interest was also associated with the LAC‐South (Supplementary Table S10). (See Figure 1.IV.N.)

3.3. Behavioral insights

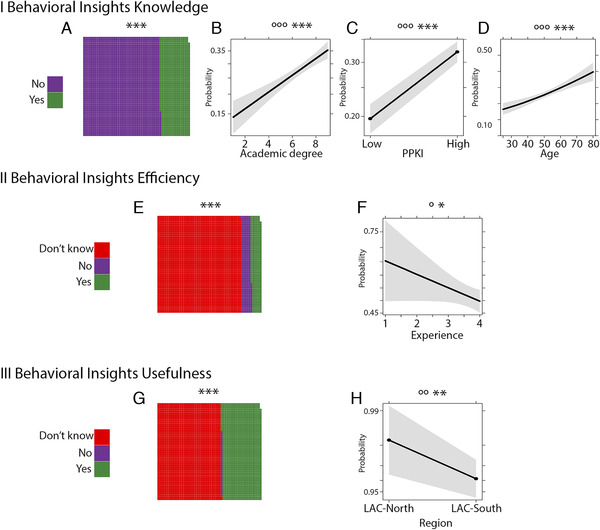

3.3.1. Behavioral insights knowledge

The majority of participants reported having a low (“No”) rather than high (“Yes”) knowledge of BI concepts. At the LAC level, there were significant (X2 = 560.58, df = 1, P < .001) differences between responses (“No”: 71.95%, “Yes”: 28.05%). These effects were replicated at the regional and country levels (Supplemental S9).

Regression models with the complete set of predictors were all significant. At the LAC level, the model (X2 = 167.14, df = 6, P < .001) showed a significant association between higher BI knowledge and the private sector, older age, higher academic degree, and higher PPKI (Supplementary Table S11). At the sub‐regional level, the model (X2 = 167.16, df = 7, P < .001) identified the same effects as in the LAC level model (Supplementary Table S12). Finally, at the country level, (X2 = 99.48, df = 7, P < .001) the same effects were identified, with the exception of the effect of private sector (Supplementary Table S13, Figure 2I).

FIGURE 2.

Information about behavioral insights in Latin America. I Behavioral insight (BI) knowledge. (A) Proportion of responses about knowledge of BI. (B) Probability of response frequency regarding high BI knowledge index (BII) by academic degree. (C) Probability of response frequency regarding high BI by PPKI (public policy knowledge index). (D) Probability of response frequency regarding high BII by age. II Behavioral insights efficiency. (E) Probability of response frequency about behavioral insights efficiency. (F) Probability of response frequency regarding response “Yes” against “No” for BI's efficiency and Experience. III Behavioral insight usefulness. (G) Proportion of responses about behavioral insights usefulness. (H) Probability of response frequency regarding “Yes” versus “No” for BI's usefulness by region. Significance references: 1. Significance (P values): effects significance (*: P ≤ .1, **: P ≤ .05, ***: P ≤ .01), model significance (°: P ≤ .1, °°: P ≤ .05, °°°: P ≤ .01). Academic degree: 1: no reported education, 2: technicians, 3: tertiaries, 4; certificates, 5: undergrads, 6: hospital interns, 7: post‐graduate specialization, 8: master's degree, 9: PhD. Experience: 1: <2 years, 2: 3‐6 years, 3: 6‐10 years, 4: >10 years

3.3.2. Behavioral insights index (BII)

Significant regression models for every level were obtained including all the predictors of interest. At the LAC level, the model (X2 = 166.67, df = 6, P < .001) showed significant effects whereby higher BII was associated with the private sector, older age, higher academic degree, and higher PPKI (Supplementary Table S14). At sub‐regional (X2 = 167.27, df = 7, P < .001) and country levels (X2 = 96.2, df = 7, P < .001), models showed the same effects as that of the LAC level (Supplementary Tables S15 and S16, respectively), except at the country level, where the private sector effect was undetected.

3.3.3. Behavioral insights efficiency

Participants mostly reported not having knowledge about the efficiency of BI (“Don't know”: 80.41%) rather than BI being inefficient (“No”: 9.52%) or efficient (“Yes”: 10.07%). At the LAC level, there were significant (X2 = 2900.73, df = 2, P < .001) differences between answers. These effects were replicated at both the regional and country levels (Supplemental S10).

Models including all predictors were not significant at any level. Using stepwise selection, the resulting model identified a trend at the LAC level (X2 = 3.4, df = 1, P = .07) along with a trend suggesting that inefficiency was more often reported by individuals with a lower experience degree (Supplementary Table S17). At the sub‐regional level, the stepwise model (X2 = 3.4, df = 1, P = .07) showed the same results as obtained for LAC (Supplementary Table S18). (See Figure 2II.)

3.3.4. Behavioral insights usefulness

Most participants had no knowledge regarding usefulness of BI (“Don't know”: 60.85%) rather than thinking they are useless (“No”: 1.20%) or useful (“Yes”: 37.85%). At the LAC level, there were significant (X2 = 2900.73, df = 2, P < .001) differences between responses (Supplemental S11). At the sub‐regional level, the stepwise regression model (X2 = 4.2, df = 1, P = .04) included a significant effect whereby BIs were considered not useful by LAC‐South (Supplementary Table S19). At the country level, the model including all predictors showed a statistical trend (X2 = 12.72, df = 7, P = .08); there was a significant effect of country, whereby Mexico showed a significant association with greater usefulness, consistent with the sub‐regional results (Supplementary Table S20). (See Figure 2III.)

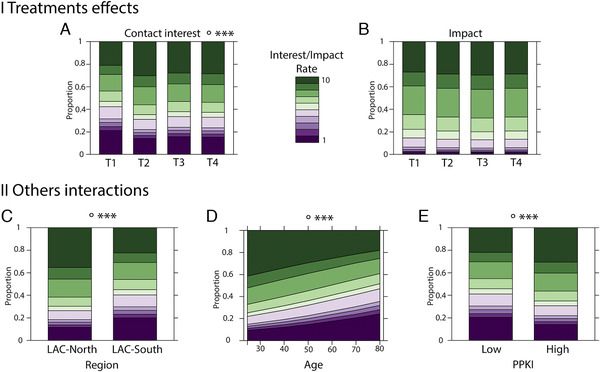

3.4. Behavioral insights treatments

In brief, participants that were part of the BI treatments were more likely to want to be contacted. In addition, a higher PPKI and belonging to LAC‐North were both associated with greater effects of BI treatments. (See Figure 3.) All three BI treatments (Simplification; Social Norm; Social Norm and Visualization) showed similar effects when compared to each other.

FIGURE 3.

Behavioral insight treatments for health care professionals in Latin America. I Treatment effects. (A) Probability of response frequency of responses regarding contact interest related to the aging program and treatments. (B) Probability of the frequency of perception interest related to the aging program and treatments. II Other interactions. (C) Probability of the frequency of contact interest related to the aging program and region. (D) Probability of the frequency of contact interest related to the aging program and age. (E) Probability of the frequency of contact interest related to the aging program and public policy knowledge index (PPKI). T1: Control. T2: Treatment using simplification. T3: Treatment using social norms. T4: Treatment using social norms and visual information. Significance (P values): effects significance (*: P ≤ .1, **: P ≤ .05, ***: P ≤ .01), model significance (°: P ≤ .1, °°: P ≤ .05, °°°: P ≤ .01)

3.4.1. Contact interest

The regression model including all predictors at the regional level presented a statistical trend (LR = 15.86, df = 9, P = .07). Higher interest in being contacted was significantly associated with the three different treatments with respect to the control condition, as well as higher PPKI, younger age, and LAC‐North region (Supplementary Table S21).

3.4.2. Impact

At the country level, the regression model including all predictors of interest presented a trend (LR = 17.22, df = 9, P = .05). It showed that higher values of perceived impact were associated with the BI treatments, higher PPKI, and being from Mexico (Supplementary Table S22).

3.4.3. Clarity

No significant effects were found (Supplementary Table S23).

4. DISCUSSION

Results of our large survey of health experts' opinions indicate a lack of knowledge of dementia in LACs at different regional levels, and several factors seem to modulate the extent and specificity of this knowledge gap. Most experts specified low accessibility and transmission of public policies and higher PPKI were related to the public sector and LAC‐North regions. Regarding knowledge barriers and tools, stigma was considered a pervasive phenomenon, and most participants highlighted the need for regional diagnostic manuals and data‐sharing platforms that are currently absent. Most participants declared not having knowledge of BI, or knowledge of its usefulness or efficacy, with some modulator effects. Finally, treatments based on BI interventions presented higher levels of interest in future contact and perceived impact across experts compared to control material. Our results may inform development of specific governmental and NGO programs in the region to improve a knowledge‐to‐action framework for diagnosis, research, and intervention on dementia.

4.1. Public policy knowledge

Our survey suggested poor accessibility and transmission of public policies relevant to dementia across the region, accentuated by some geographical (South), demographic (older people), and sector (private) variables. Results seem to be consistent with the low availability of formal geriatric and dementia specialty training in the region, 8 particularly in South America. 39 Lack of knowledge is considered a critical barrier to implementing best policy practices. 11 Heterogeneous policies to fight dementia in the region face multiple challenges. 2 Available strategies to improve the access and transmission of current policies 10 , 40 should be considered. Regarding the experts’ public policy knowledge, higher levels of knowledge were related to working in the public sector and having higher academic degrees. At sub‐regional and country levels, older age emerged as a predictor of higher knowledge, and lower knowledge was associated with LAC‐South/Argentina. This result highlights the critical role of the public sector in reinforcing knowledge of experts, 1 and suggests a need for greater professional training in the LAC‐South region. 39

4.2. Stigma and tools for creating knowledge

Most participants agreed that stigma is ubiquitous across the region, and this effect was independent of any particular predictors, confirming previous country‐level results in students 13 and community members 13 in some LACs, and even health practitioners in other regions. 11 Stigma research has mostly focused on HICs 12 underscoring the need for additional research in the developing world. The development of evidence‐based stigma reduction approaches appears to be in critical need across LACs.

Two main resources for expert knowledge, diagnostic manuals and data‐sharing platforms, were highly appraised by most survey participants, with higher PPKI, younger age, and LAC‐South showing greatest interest in such resources. Harmonized approaches with manuals 17 and registries 9 have proven successful, 22 with some emergent inclusion of LACs. 24 Similarly, data‐sharing platforms such as ADNI, 18 , 19 DIAN, 23 and GAAIN 41 are beginning to include a small amount of LAC data. We are also developing a platform with regional organizations including the Interamerican Development Bank. Beyond these on‐going efforts, our study suggests a strong interest in developing additional resources specific to the region. The development of knowledge‐enhancing tools may improve epidemiological data, research, preclinical registries, national guidelines, and interventions.

4.3. Behavioral insights

Most of the participants reported not having knowledge of BI. Older age, higher degree, working in the private sector, and greater policy knowledge increased the probability of having knowledge of BI. The increasing knowledge of BI in the private sector may be explained by the fact that BI is well known across health care business. 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 Consistent with low BI knowledge, most participants did not know if these programs are effective (with lower experience and academic degree increasing the negative evaluation) or useful (with LAC‐North and Mexico having more positive impressions, consistent with the majority of BI studies coming from LAC‐North 34 , 42 ). The low opinions on BI efficacy and usefulness may be explained by the very low familiarity with BI and related interventions. Innovative aspects of BI may need more public discussion to increase awareness of these methods, as well as further development of impact programs. 28

The use of different BI treatments improved appraisal of aging‐related information among participants. Compared with standard procedures, the BI treatments increased the participants' interest in being re‐contacted (with higher PPKI and LAC‐North associated with greater effects of the intervention). Our preliminary findings support the use of BI interventions with simplified, visual, and social norms–guided information and suggest that this type of intervention may help to facilitate engagement and perception of impact across health care professionals, 34 , 43 as well as the general population in this region 33 and beyond. 32

4.4. Limitations and further assessments

One main limitation of this work is the use of self‐report surveys, which are influenced by social desirability. Nevertheless, this limitation is general for surveys on dementia. 6 , 8 , 10 , 44 Moreover, we have focused on professionals working in the field, maximizing the expertise that informs these opinions. In addition, we have modeled the effects of different predictors in different dimensions of knowledge and have shown that BI intervention seems to have a positive impact. Nevertheless, future studies are required to directly assess the impact of knowledge in diagnoses, care, and intervention in dementia across LACs.

The present results should be extrapolated to all LACs with caution. As in other LAC surveys, 8 , 39 there was an imbalance of representation across countries. Limitations notwithstanding, this is one of the largest LAC regional survey of expert professionals working on aging. The observation of consistency of several patterns across countries—as well as some expected discrepancies–is reassuring with regard to the generalizability of our findings. In addition, the imbalance effect was statistically accounted for in our analytical study design by using different regional levels and implementing approaches that account for the impact of sample size when estimating confidence intervals. 45 Future studies will optimally include samples with balanced representation across LACs.

Present findings pave the way for future comparisons with other geographical regions, including HIC, Europe, and Asia. Information regarding access and transmission of specific policies, although considered a priority, 10 has yet to be systematically compared across different regions. In principle, our findings and prior work 7 , 8 suggest that LACs have lower levels of access and transmission than HICs. Our results also complement world‐wide reports of stigma, mostly coming from the United States and Europe. 12 Prior reports provide some evidence indicating higher levels of stigma in LACs. 15 Cross‐cultural validated interventions will need to be tested across regions. In addition, in comparison with HICs, 9 , 17 , 18 , 20 , 23 LACs have very few platforms or manuals for improving diagnosis and disease characterization (but see 46 ). Furthermore, our survey suggested that there is limited knowledge of BI in LACs, in contrast to the widespread use of BI in health settings, 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 chronic diseases, aging, and dementia 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 in other regions. All of these tools (manuals, platforms, BI interventions) will be critically needed to provide a more global characterization and “know how” of dementia representing populations across the globe.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our survey of experts in aging indicates a strong dementia knowledge gap that may have a negative impact on multiple levels. Government and regional NGOs may benefit from the present findings by focusing on specific coordinated actions to increase transmission, accessibility, and knowledge of public policies and dementia expertise. 47 , 48 In addition, the impact of stigma could benefit from educational programs on dementia in LAC, as suggested recently. 1 Regional manuals to aid dementia diagnosis seem to be a priority and will help to increase the shared practical knowledge of dementia in health care. Similarly, there may be clear benefit to expanding data‐sharing platforms to enhance clinical practices and facilitate research in the region. With regards to BI, the first challenge will be improving BI knowledge so this approach can be used more systematically to achieve these objectives. Overall, our results raise awareness among decision‐makers, professionals, governments, and NGOs (such as the Global Brain Health Institute and the Alzheimer's Association) about the need to further enhance expert knowledge about dementia in LACs.

FUNDING

This work is partially supported by Alzheimer's Association GBHI ALZ UK‐20‐639295; IntraMed, NIH‐NIA R01 AG057234, the Interamerican Development Bank, and the MULTI‐PARTNER CONSORTIUM TO EXPAND DEMENTIA RESEARCH IN LATIN AMERICA [ReDLat, supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Aging (NIH/NIA R01 AG057234), Alzheimer's Association (SG‐20‐725707), Tau Consortium, and Global Brain Health Institute)]. AI and AS are partially supported by ANID /FONDAP/ 15150012. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of these Institutions.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors report no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception (AI), design (AI, DF, AT, EH, MD) supervision (JY), survey revision (AT, MC, FT), acquisition and preprocessing (DF, AI, EH, MD, AT), analysis (EH and MD), interpretation (AI, EH, MD), draft manuscript (AI, EH, MD, AT), high‐level revision (JY), manuscript revision (all).

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

Data from the data sets are available for research only after ethical approval for a specific project. The code for the data analysis of this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supporting information

Supplementary information

Ibanez A, Flichtentrei D, Hesse E, et al. The power of knowledge about dementia in Latin America across health professionals working on aging. Alzheimer's Dement. 2020;12:e12117 10.1002/dad2.12117

Daniel Flichtentrei, Eugenia Hesse, Martin Dottori and Ailin Tomio contributed equally to this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Parra MA, Baez S, Allegri R, et al. Dementia in Latin America: assessing the present and envisioning the future. Neurology. 2018;90(5):222‐231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Custodio N, Wheelock A, Thumala D, Slachevsky A. Dementia in Latin America: epidemiological evidence and implications for public policy. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ibáñez A, Sedeño L, García AM, Deacon RMJ, Cogram P. Human and animal models for translational research on neurodegeneration: challenges and opportunities from South America. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baez S, Ibanez A. Dementia in Latin America: an emergent silent tsunami. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reitz C, Mayeux R. Genetics of Alzheimer's disease in Caribbean Hispanic and African American populations. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75(7):534‐541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, et al. General practitioners' knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age Ageing. 2004;33(5):461‐467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gonzalez FJ, Gaona C, Quintero M, Chavez CA, Selga J, Maestre GE. Building capacity for dementia care in Latin America and the Caribbean. Dement Neuropsychol. 2014;8(4):310‐316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Richly P, Lopez P, Prats M, et al. Are medical doctors in Latin America prepared to deal with the dementia epidemic? Int Psychogeriatr. 2018:1‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krysinska K, Sachdev PS, Breitner J, Kivipelto M, Kukull W, Brodaty H. Dementia registries around the globe and their applications: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(9):1031‐1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bethell J, Pringle D, Chambers LW, et al. Patient and public involvement in identifying dementia research priorities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(8):1608‐1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tropea J, LoGiudice D, Liew D, Roberts C, Brand C. Caring for people with dementia in hospital: findings from a survey to identify barriers and facilitators to implementing best practice dementia care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(3):467‐474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Herrmann LK, Welter E, Leverenz J, et al. A systematic review of dementia‐related stigma research: can we move the stigma dial? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):316‐331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blay SL, Peluso É TP. College students and the public stigma of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(10):1379‐1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blay SL, Toledo Pisa Peluso E. Public stigma: the community's tolerance of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):163‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bhatt J, Comas Herrera A, Amico F, et al. The World Alzheimer Report 2019: Attitudes to dementia. 2019.

- 16. Gray HL, Jimenez DE, Cucciare MA, Tong HQ, Gallagher‐Thompson D. Ethnic differences in beliefs regarding Alzheimer disease among dementia family caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(11):925‐933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Besser L, Kukull W, Knopman DS, et al. Version 3 of the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center's Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2018;32(4):351‐358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carrillo MC, Bain LJ, Frisoni GB, Weiner MW. Worldwide Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(4):337‐342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hendrix JA, Finger B, Weiner MW, et al. The Worldwide Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: an update. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(7):850‐859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Butcher J. Alzheimer's researchers open the doors to data sharing. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(6):480‐481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Aisen PS, et al. 2014 Update of the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: a review of papers published since its inception. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(6):e1‐120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Langa KM, Ryan LH, McCammon RJ, et al. The Health and Retirement Study Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol Project: study design and methods. Neuroepidemiology. 2020;54(1):64‐74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tang M, Ryman DC, McDade E, et al. Neurological manifestations of autosomal dominant familial Alzheimer's disease: a comparison of the published literature with the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network observational study (DIAN‐OBS). Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(13):1317‐1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee J, Banerjee J, Khobragade PY, Angrisani M, Dey AB. LASI‐DAD study: a protocol for a prospective cohort study of late‐life cognition and dementia in India. BMJ open. 2019;9(7):e030300‐e030300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Young SD. Behavioral insights on big data: using social media for predicting biomedical outcomes. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22(11):601‐602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Robertson T, Darling M, Leifer J, Footer O, Gordski D. Behavioral design teams: the next frontier in clinical delivery innovation? Issue Brief. 2017;2017:1‐16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. VanEpps EM, Volpp KG, Halpern SD. A nudge toward participation: improving clinical trial enrollment with behavioral economics. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(348):348fs313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hansen PG, Skov LR, Skov KL. Making healthy choices easier: regulation versus nudging. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:237‐251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Möllenkamp M, Zeppernick M, Schreyögg J. The effectiveness of nudges in improving the self‐management of patients with chronic diseases: a systematic literature review. Health Policy. 2019;123(12):1199‐1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nordgren A. How to respond to resistiveness towards assistive technologies among persons with dementia. Med Health Care Philos. 2018;21(3):411‐421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Notthoff N, Carstensen LL. Positive messaging promotes walking in older adults. Psychol Aging. 2014;29(2):329‐341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Westmoreland GR, Counsell SR, Sennour Y, et al. Improving medical student attitudes toward older patients through a “council of elders” and reflective writing experience. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(2):315‐320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Valle R, Yamada A‐M, Matiella AC. Fotonovelas: a health literacy tool for educating Latino older adults about dementia. Clin Gerontol. 2006;30(1):71‐88. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mendoza‐Ruvalcaba NM, Fernández‐Ballesteros R. Effectiveness of the vital aging program to promote active aging in Mexican older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1631‐1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Strassheim H. Behavioural mechanisms and public policy design: preventing failures in behavioural public policy. Public Policy and Administration. 0(0):0952076719827062. [Google Scholar]

- 36. R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [computer program]. Vienna: Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Field A, Miles J, Field Z. Discovering Statistics Using R. Sage publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lipsitz SR, Fitzmaurice GM, Molenberghs G. Goodness‐of‐fit tests for ordinal response regression models. J R Stat Soc Ser C. 1996;45(2):175‐190. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lopez JH, Reyes‐Ortiz CA. Geriatric education in undergraduate and graduate levels in Latin America. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2015;36(1):3‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nakanishi M, Nakashima T. Features of the Japanese national dementia strategy in comparison with international dementia policies: how should a national dementia policy interact with the public health‐and social‐care systems? Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(4):468‐476.e463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Neu SC, Crawford KL, Toga AW. Sharing data in the global Alzheimer's Association Interactive Network. Neuroimage. 2016;124(Pt B):1168‐1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nava‐Munoz S, Moran AL. CANoE: a context‐aware notification model to support the care of older adults in a nursing home. Sensors. 2012;12(9):11477‐11504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Diez‐Canseco F, Toyama M, Ipince A, et al. Integration of a technology‐based mental health screening program into routine practices of primary health care services in Peru (the Allillanchu project): development and implementation. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(3):e100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Di Pucchio A, Di Fiandra T, Marzolini F, Lacorte E, Vanacore N. Survey of health and social‐health services for people with dementia: methodology of the Italian national project. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2017;53(3):246‐252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ranganathan P, Pramesh CS, Aggarwal R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: measures of agreement. Perspect Clin Res. 2017;8(4):187‐191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. New manual aims to create common standards for dementia diagnosis across Latin America. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;(7)(16):1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Parra M, Baez S, Sedeño L, et al. Dementia in Latin America: Paving the way towards a regional action plan. Alzheimers Dement. 2020. 10.1002/alz.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ibanez A, Kosik KS. COVID‐19 in older people with cognitive impairment in Latin America. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(9):719‐721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information

Data Availability Statement

Data from the data sets are available for research only after ethical approval for a specific project. The code for the data analysis of this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.