Abstract

Objective

To express the significance and report the clinical outcomes of active duty military patients who underwent direct pectoralis major repairs in a chronic setting.

Methods

Retrospective review of data collected on 16 active duty military patients who underwent direct repair of a chronic pectoralis major tear. Pre-operative and post-operative evaluations (minimum 2 year follow up; mean, 53.46 months; range, 24–88 months) included range of motion, Bak classification, visual analog scale (VAS), Single Assessment Numerical Evaluation (SANE) Score, Quick Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) Score, and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Shoulder Score.

Results

Using a Bak classification, 94% (15/16) of patients were reported with good or excellent results. Mean VAS score improved from 7.08 ± 1.66 to 0.54 ± 1.20 (p < 0.0001). Mean SANE score improved from 42.31 ± 19.96 to 94.62 ± 5.94 (p < 0.0001). The average Quick DASH score increased from 55.42 ± 15.34 to 7.30 ± 6.39 (p < 0.0001). The average ASES score increased from 48.71 ± 13.80 to 94.62 ± 7.63 (p < 0.0001). There was no loss of motion after surgery in forward flexion, external rotation or internal rotation. The average internal rotation muscle power increased from 4.15 ± 0.48 to 4.92 ± 0.28 (p < 0.0001).

Complications

6.25% (1/16) patients developed a keloid scar, tender to direct pressure post-operatively. 94% (15/16) of patients returned to their pre-operative level of recreational and military job activity.

Conclusion

Military patients who underwent direct repair of a chronic pectoralis major tear had excellent clinical outcomes, low risk of complications, and a high return to pre-operative level of recreational and military job activity.

Level of evidence

Case Series; IV.

Keywords: Direct repair, Chronic pectoralis major tear, Pectoralis major tear, Military patients

1. Introduction

Tears of the pectoralis major are infrequent but functionally significant injuries, particularly for more active individuals, such as athletes and members of the military. The chronicity of the tear typically determines the type of surgical management, with direct repair preferred in acute cases. Under chronic conditions, challenges develop that may preclude direct repair and support the need for graft reconstruction. Specifically, shortening of the musculotendinous unit and scarring potentially increase the risk of neurovascular injury, and place an increasing amount of tension on the repair. Despite those concerns, direct repair for chronic pectoral tendon tears is a viable option, requiring meticulous surgical mobilization of the musculotendinous unit and secure osseous fixation. There is limited information in the current orthopedic literature on the outcome of direct repair of chronic pectoralis major tears.

The purpose of this study is to report the clinical outcomes of military patients with direct repair of a chronic pectoralis major tendon tear.

2. Materials & methods

This study is a retrospective review of data collected prospectively on 16 active military patients with a chronic (greater than 6 weeks) pectoralis major tendon tear. All patients underwent surgery by a single surgeon between 2010 and 2017. All patients were male, with the mean age of 27 years (range 21 to 41 years). The dominant extremity was involved in ten patients. Inclusion criteria consisted of patients with an isolated pectoralis major tendon tear presenting for clinical evaluation and treatment six weeks or more after the initial injury. Exclusion criteria consisted of patients with concomitant injuries to the shoulder girdle with the torn pectoralis major.

The mechanism of injury in thirteen patients was a bench-pressing exercise, in two patients was combative training, and in one patient a fall. The diagnosis was confirmed by physical examination, with findings including weakness and pain in internal rotation, loss of the anterior axillary fold, and typical traction deformity of the pectoralis major muscle (Fig. 1) in all patients. MRI without contrast confirmed the pectoralis major tear in nine patients (Fig. 2). The other seven patients were diagnosed prior to surgery based on the history and clinical examination (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Typical traction deformity of right pectoralis major sternal head tendon tear (*) in a 28 year old male, 13 months post bench pressing injury.

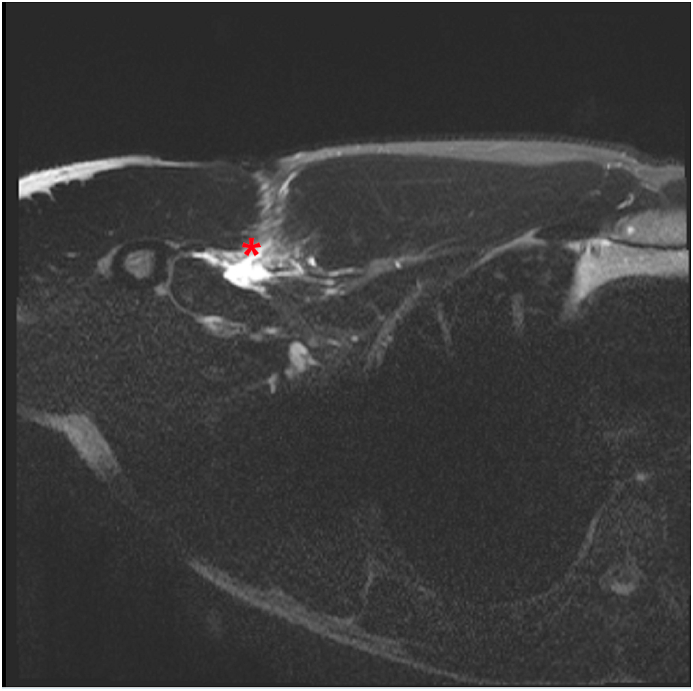

Fig. 2.

Chest MRI without contrast confirming pectoralis major sternal head tendon tear (*).

Table 3.

Demographics, diagnostic characteristics, and muscle power assesment of patients.

| Pt # | Rank | Occupation/Specialty | Time to surgery (months) | Reason for late presentation | Dx | IR Strength prior to surgery | IR Strength at last follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SFC | Firefighter | 11 | Pt was treated conservatively first by different provider. | MRI | 5- | 5 |

| 2 | SGT | Infantry | 24 | Injury was misdiagnosed initially. | MRI | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | SST | Infantry | 2 | Pt presented for treatment 2 mos s/p injury. | Clinical | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | PFC | Infantry | 18 | Pt was moving from different base. Presented late due to military activity. | MRI | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | SPC | Infantry | 5 | Pt was treated conservatively first by different provider. | MRI | 5- | 5 |

| 6 | SPC | Infantry | 11 | Pt was treated conservatively first by different provider. | Clinical | 5- | 5 |

| 7 | 1LT | Infantry | 8 | Pt was treated conservatively first by different provider. | MRI | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | SPC | Infantry | 12 | Pt was treated conservatively first by different provider. | Clinical | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | SFC | Infantry | 12 | Injury was misdiagnosed initially as partial RC tear and biceps tendinosis. (2 steroid injections to shoulder + PT) | Clinical | 4+ | 5 |

| 10 | SFC | Infantry | 30 | Pt presented for treatment 2 years s/p injury and then elected to stay on conservative treatment for 6 mos. | MRI | 4 | 5- |

| 11 | CW4 | Artillery | 48 | Injury was misdiagnosed initially and the patient was treated with PT, steroid injection and pain medications. | Clinical | 4 | 5- |

| 12 | SPC | Infantry | 4 | Pt presented for treatment more than 3 mos s/p injury. | Clinical | 4- | 5- |

| 13 | SSG | Artillery | 1.5 | Pt presented for treatment 6 weeks s/p injury. | MRI | 4 | 5 |

| 14 | SPC | Infantry | 11 | Pt was treated conservatively first by different provider. | Clinical | 3+ | 5- |

| 15 | SSG | Artillery | 6 | Pt was treated conservatively first by different provider. | MRI | 5- | 5 |

| 16 | SGT | Radar operator | 10 | Presented late due to deployment. | MRI | 4+ | 5 |

Patients were assessed pre-operatively and post-operatively by measuring active range of motion, strength by manual muscle testing, and functional scores including visual analog scale (VAS), Single Assessment Numerical Evaluation (SANE) Score, Quick Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) Score, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Score, and Bak Classification. The patients were asked about their satisfaction level regarding the cosmetic outcome of the reconstruction.

The mean time to surgical repair was 13.3 months (range 1.5 to 48 months). The reason for late presentation in six patients was due to deployments and other military obligations. Seven others were treated conservatively by other providers before being referred to us, and three were misdiagnosed initially and referred to us for other shoulder problems(Table 3). The sternal head of the pectoralis major was torn in 12 patients. Both the sternal and clavicular heads were torn in four patients. The follow-up assessments were set at a minimum of two years (mean 53.5 months, range 24 to 88 months).

2.1. Surgical procedure

General anesthesia was preferred to allow complete muscle relaxation and mobilization of the torn pectoralis major tendon. The patient was placed in a beach chair position with the body elevated 30–45°. A small roll of sheets was placed under the patient's scapula to allow optimal shoulder motion during the repair. The arm, shoulder and chest were prepped and draped free to allow intraoperative manipulation. An evaluation under anesthesia was made with special attention to the anterior chest wall and axilla.

A deltopectoral approach was used, with the proximal extent of the incision placed slightly medial to allow easier access to the retracted tendon, while the distal aspect was placed slightly lateral for better exposure of the pectoralis insertion. In the case of an isolated rupture of the sternocostal head, this was explored inferior to the intact clavicular head of the pectoralis major. As the torn tendon was identified, several #2 traction sutures (FiberWire; Arthrex, Naples, FL) were place through it, and a combination of sharp and blunt dissection was used to free the muscle and tendon from the chest wall and subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 3). Care was taken to avoid extensive deep dissection under the muscle belly, to avoid injury of the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. A distinction could be made between the sternal and clavicular heads and each one was carefully dissected and mobilized separately.

Fig. 3.

The torn pectoralis major sternal head tendon isolated and freed from surrounding scar tissue, ready for fixation back to its humeral footprint.

Once the tendons were sufficiently mobilized to enable adequate reduction to its footprint, the footprint area was prepared using a motorized burr to create an area of bleeding bone. Care was taken not to over-decorticate, which would weaken the site of anchor insertion. When the clavicular head is intact, it can be used to help identify the sternal head footprint on the humerus just posterior and slightly proximal to it. In cases where both heads are ruptured, the superior insertion of the latissimus dorsi can be used as a marker for the distal border of the footprint. The average dimensions of the footprint are 73 mm in length and 3 mm in width, along the lateral border of the bicipital groove. Two to six double loaded anchors (Super Quick DS; DePuy Mitek, Raynham, MA) were placed in a square configuration, with 1–1.5 cm between each set of two anchors. One limb of each suture from the anchor was passed into the tendon using a Mason-Allen configuration, creating a broad fixation of the deteriorated tissue, thus minimizing the risk of suture cutout. The second limb was brought through the tendon with a single throw and used as the post to tension. The arm was position in neutral rotation and abduction and slight forward flexion to minimize the tension on the tendons during fixation. Pulling the post reduced the tendon tightly to the footprint as the suture slid through the anchor. This was followed by alternating half hitches, completing the repair.1, 2, 3 In cases of relatively low tissue quality, we used a greater number of sutures for tendon fixation. The logic was to reduce the tension on each suture. The repair was inspected and palpated while the arm was gently internally and externally rotated to ensure a tight, stable repair.

2.2. Post-operative protocol

All patients were discharged home on the day of surgery. Analgesic pain medications were prescribed for no more than 10 days post-operatively. All patients were immobilized in a SmartSling (Ossur, Reykjavik, Iceland) for 6 weeks after surgery. Elbow, wrist, and finger active range of motion exercises were initiated after resolution of the interscalene block. No active motion of the shoulder was allowed during the first six weeks after surgery; only passive forward elevation of the adducted arm to 130° was allowed. After six weeks, passive range of motion was advanced and active range of motion exercises were introduced to all patients. Strengthening exercises were started 12 weeks after surgery. Return to full military job activity and contact sport was allowed 6–9 months after surgery.

2.3. Statistical analysis

A paired t-test was used to compare the differences between the pre-operative and post-operative results. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

No range of motion loss was noted in any patient in forward elevation, external rotation, or internal rotation. Manual muscle testing using Medical Research Council (MRC) grading revealed an average increase in internal rotation muscle power from 4.15 ± 0.48 (range, 3 to 5) pre-operatively to 4.92 ± 0.28 (range, 4 to 5) post-operatively (p < 0.0001). The mean VAS score improved from 7.08 ± 1.66 (range, 4 to 9) pre-operatively to 0.54 ± 1.20 (range, 0 to 4) post-operatively (p < 0.0001). The mean SANE score improved from 42.31 ± 19.96 (range, 20 to 85) pre-operatively to 94.62 ± 5.94 (range, 85 to 100) post-operatively (p < 0.0001). The average Quick DASH score improved from 55.42 ± 15.34 (range, 29.55 to 81.82) pre-operatively to 7.30 ± 6.39 (range, 0 to 19.98) post-operatively (p < 0.0001). The mean ASES score improved from 48.71 ± 13.80 (range, 30 to 71.67) pre-operatively to 94.62 ± 7.63 (range, 72.5 to 100) post-operatively (p < 0.0001) (Table 1). Using a Bak classification 94% (15/16 patients) reported good to excellent results after primary repair. 94% (15/16 patients) were satisfied with the cosmetic outcome of the pectoralis major repair (Fig. 4). Complications included the development of a keloid scar which was tender to direct pressure post-operatively in 6.25% (1/16 patients). 94% (15/16 patients) returned to their pre-operative level of recreational and military job activity (10 infantry, 3 artillery, 1 firefighter, 1 radar operator) (Table 3).

Table 1.

Pre-surgical measurements VS final measurements.

| Type of Measurement | Pre-surgical Measurement |

Final Measurement |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Active Forward Flexion | 158.46 ± 3.15 | 158.84 ± 2.99 | P = 0.76 |

| Mean Active External Rotation | 68.46 ± 4.27 | 68.46 ± 3.76 | P = 1.00 |

| Mean Active Internal Rotation | T10 ± 2 levels | T9 ± 2 levels | P = 0.30 |

| Mean Muscle Power in Internal Rotation | 4.15 ± 0.48 | 4.92 ± 0.28 | P < 0.0001 |

| VAS | 7.08 ± 1.66 | 0.54 ± 1.20 | P < 0.0001 |

| SANE | 42.31 ± 19.96 | 94.62 ± 5.94 | P < 0.0001 |

| Quick DASH | 55.42 ± 15.34 | 7.30 ± 6.39 | P < 0.0001 |

| ASES Score | 48.71 ± 13.80 | 94.62 ± 7.63 | P < 0.0001 |

Fig. 4.

Cosmetic outcome of right pectoralis major sternal head tendon tear repair.

4. Discussion

Rupture of the pectoralis major is a functionally limiting injury. Although non-operative treatment is an option, surgical repair is typically advised to restore strength and function, especially in more active individuals such as athletes and military personnel.4, 5, 6 The injury is more frequent in the military than in the general population due to higher levels of exercise, physical training (specifically bench pressing), and combat requirements. Due to deployments, changes in duty station, and work responsibilities, immediate repair during the acute phase of injury is frequently not possible for military personnel. As such, these patients frequently present with chronic pectoralis major tears requiring surgical treatment to restore pre-injury level of function.

Reports of direct repair of chronic pectoralis major tears in the orthopaedic literature are sparse. Over the course of the past six decades, the peer-reviewed literature on direct repair of chronic pectoralis major tendon tear includes only reports on small groups of patients. Additionally, various definitions are used to define the period as chronic between injury and repair (e.g. 3–8 weeks to time of repair) and patients with less than two years follow-up are included in most of these studies (Table 2). Despite these limitations, direct repairs performed in chronic settings have been successful, resulting in a high percentage of satisfied patients who return to activity with improved function and cosmesis.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Additionally, the results from some studies suggest that direct repairs in the chronic setting are comparable to the results of direct repair in the acute setting.11,13 The results of this study further support those previous conclusions, specifically with regards to military personnel.14,15

Table 2.

Studies focusing on primary repair of chronic pectoralis major tear.

| Our Study | Deepak Joshi et al.3 | Mansoor Choudhary et al.6 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients at final follow-up | 16 | 11 | 8 (7 primary repair, 1 allograft) |

| Mean follow up time | 53 months | 48 months | 19.6 months |

| Mean patients age | 27 | 26 | 36 |

| Time from injury to surgery | 13.3 months | 2.6 months | 25.6 months |

| Mean final scores | ASES 94.62 ± 7.63 VAS 0.54 ± 1.2 Sane 94.62 ± 5.94 Quick DASH 7.3 ± 6.39 |

ASES 95.09 ± 2.6 Penn 9.36 ± 0.8, 8.27 ± 0.9 and 59 ± 1.34 |

Oxford Shoulder 43.7 |

| Complications Rate | 6.25% Keloid scar | 18.2% Unsatisfactory cosmetic appearance | 25% skin tethering and stiffness |

Concerns about direct repair in the chronic setting are legitimate. Scarring of the pectoralis tissue, shortening of the pectoralis muscle-tendon unit, and degradation of the repairable tendon tissue can create challenges to direct repair. As such, critical steps to the success of direct repair in the chronic setting include meticulous surgical dissection respectful of surrounding neurovascular structures, anatomic repair with minimal tension, and secure fixation.

Graft reconstruction (autograft or allograft) is a viable option in chronically torn pectoralis major tendons. But, there are issues to consider with this reconstructive approach, such as donor site morbidity associated with autograft procurement and factors associated with the use of allograft tissue (e.g. cost, infection, healing). Given the consistent and reliable outcomes of direct repair including biologic healing of native tissue, we suggest that graft reconstruction be considered only in cases where the muscle-tendon unit cannot be adequately mobilized or the repairable tissue is not of sufficient quality to ensure secure repair.

The limitations of this study, similar to other reports on surgical repair of chronic pectoralis major tendon tears, include a small sample size who were all male and military members, with all repairs performed by a single surgeon (NP). To our knowledge, this study includes the largest patient group with chronic direct pectoralis major repair in the English literature. It took eight years to collect data on all of these patients, which reflects the infrequency both of this injury and the setting of delayed repair.

Despite those limitations, the results offer useful information to surgeons and patients making treatment decisions for chronic pectoralis tears. Overall, the results of this study indicate that direct repair is a reliable and safe option for chronic pectoralis major tendon tears.

5. Conclusion

Overall, military patients who underwent direct repair of a chronic pectoralis major tear had excellent clinical outcomes, low risk of complications, improved strength, and a high return to pre-operative level of military job and recreational activity.

Funding

None of the authors have received grant support or research funding for this manuscript.

None of the authors have any proprietary interests in the materials described in the article.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nata Parnes: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing - original draft, Supervision. Jeff Perrine: Investigation, Resources, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Hunter Czajkowski: Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing - review & editing. Michael J. DeFranco: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

References

- 1.Carey P., Owens B. Insertional footprint anatomy of the pectoralis major tendon. Orthopedics. 2010;33:1124–1127. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20091124-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mooers B, Westermann R, Wolf B. Outcomes following suture-anchor repair of the pectoralis major tears: a case series and review of the literature. Iowa Orthop J 35: 8-12. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Joshi D., Jain J., Chaudhary D. Outcome of repair of chronic tears of the pectoralis major using corkscrew suture anchors by box suture sliding techniques. World J Orthoped. 2016;7:670–677. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i10.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanna C., Glenny A., Stanley S. Pectoralis major tears: comparison of surgical and conservative treatment. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:202–206. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.3.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kircher J., Liskoven C., Patzer T. Surgical and non-surgical treatment of total rupture of pectoralis major muscle in athletes: update and critical appraisal. J Sports Med. 2010;1:201–205. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S9066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansoor C., Numan S. The outcome of surgical management of chronic pectoralis major ruptures in weightlifters. Acta Orthop Belg. 2017;83:433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anbari A., Kelly J., Moyer R. Delayed repair of a ruptured pectoralis major tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:254–256. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280021901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunkelman N., Collier F., Rook F. Pectoralis major muscle rupture in windsurfing. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:819–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindenbaum B. Delayed repair of a ruptured pectoralis major muscle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;109:120–121. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197506000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J., Gowd A., Garcia G. Analysis of return to sports and weight training after repair of the pectoralis major tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:2151–2157. doi: 10.1177/0363546519851506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schepsis A., Grafe M., Jones H. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:9–15. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280012701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfe S., Wickiewicz T., Cavanaugh J. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:587–593. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aarimaa V., Rantanen J., Heikkila J. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1256–1262. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ElMaraghy A., Devereaux A systematic review and comprehensive classification of pectoralis major tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nute D., Kusnezov N., Dunn J., Waterman B. Return to function, complications, and reoperation rates following primary pectoralis major tendon repair in military service members. J Bone Joint Surg. 2017;99A:25–32. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]