Abstract

223Ra-dichloride is a bone-seeking targeted alpha (α)-emitting approved for bone metastases in prostate cancer. Here, we report a case of therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia (t-APL) following administration of 223Ra, showing some evidence of a causative relationship. A patient with metastatic prostate cancer received therapy with 223Ra, with 6 injections of the radiopharmaceutical at a standard dose of 55 kBq/kg at 4-week intervals for a cumulative administered activity of 26.3 MBq. PET/CT with 18F-methylcholine repeated 1 month after the conclusion of 223Ra was negative. After 8 months, he developed pancytopenia and we made a diagnosis of therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia (t-APL). We then studied the genomic locations of the breakpoints in the PML and RARA genes, which were at nucleotide positions 1708-09 of PML intron 3, respectively, outside the previously reported Topo II-associated hotspot region. t-APL was cured with all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic trioxide. The type of PML/RARA rearrangement we identified, in absence of other myelotoxic treatments, is suggestive of a possible direct causal relationship with exposure to 223Ra and warrants further investigations.

Keywords: Acute promyelocytic leukemia, Prostate cancer. radium-223, Therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia

Introduction

223Ra-dichloride (Xofigo®) (223Ra) is a bone-seeking targeted alpha (α)-emitting radiopharmaceutical, recently approved for the treatment of symptomatic bone metastases in castration-resistant prostate cancer (PC). α-Particles induce DNA double-strand breaks, leading to cell cycle-independent cell death. However, the α-particle range of 223Ra is less than 100 μm, thereby theoretically maximizing dose to cortical bone and metastatic cells while minimizing the dose to the marrow and other normal tissues. In fact, hematological toxicity from Radium-223 in the ALSYMPCA study, a phase 3 randomized trial, was similar to that of placebo [1].

Here, we report a case of therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia (t-APL) following administration of 223Ra, showing some evidence of a possible causative relationship.

Case Report

In August 2016, a 79-year-old male underwent prostate biopsy due to increased prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels (306 ng/mL), which revealed a PC, Gleason 8 (4 + 4), and asymptomatic metastasis of right humerus, left sacroiliac joint, and first lumbar vertebrae. He started triptorelin and bicalutamide. In November 2017, after progression of bone metastasis, he suspended bicalutamide, continuing triptorelin.

From June 2018 to December 2018, he received therapy with 223Ra, which consisted of 6 intravenous injections of the radiopharmaceutical at a standard dose of 55 kBq/kg at 4-week intervals for a cumulative administered activity of 26.3 MBq. Positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) with 18F-methylcholine, carried out at baseline (June 2018: Figs. 1A and 2A), showed highly increased tracer uptake in the skeletal lesions. PET/CT with 18F-methycholine, repeated 1 month after the conclusion of 223Ra-treatment (January 2019: Figs. 1B and 2B), demonstrated complete metabolic response of the bone metastases and CBC was normal. In August 2019, the patient presented with diarrhea and pancytopenia, which was initially thought to be related to bone marrow infiltration by metastatic disease, which meanwhile had progressed as shown by CT (increase of bone marrow metastasis). In consideration of the age (82 years) of the patient, and the PC, bone marrow evaluation was deferred, and he began enzalutamide. Two months later, blood counts were still low (white blood cell count: 1100/μL, hemoglobin: 7.4 g/dL, platelets: 42,000/μL, and neutrophils: 600/μL), and he was readmitted to the geriatric ward for neutropenic fever, which promptly responded to ceftriaxone. Considering the possibility of a different cause of cytopenia and the infectious complication of neutropenia, we performed a bone marrow aspiration that showed a mixed infiltration from large cells suggestive of epithelial origin, and blasts with Auer rods, rare Faggott cells, suggestive of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). FISH was positive for the t(15;17) translocation, and the PML/RARα BCR3 transcript was detected by PCR.

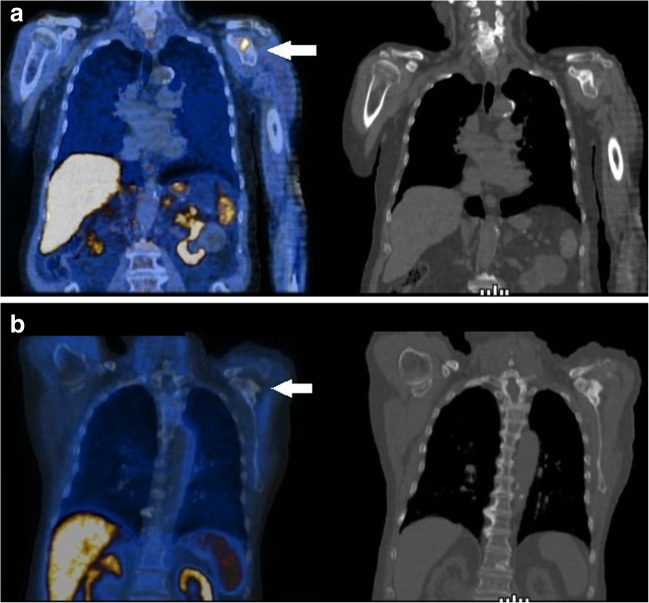

Fig. 1.

a Upper row. PET/CT scan with 18F-methylcholine at baseline demonstrated a focus of increased tracer uptake in a metastatic lesion in the acromion of the left scapula (white arrow) as evident in the fused coronal PET/CT (left) and corresponding CT images (right). b Lower row. PET/CT with 18F-methylcholine-acquired 1 month after the completion of 223Ra treatment demonstrated complete metabolic response of the skeletal lesion (white arrow)

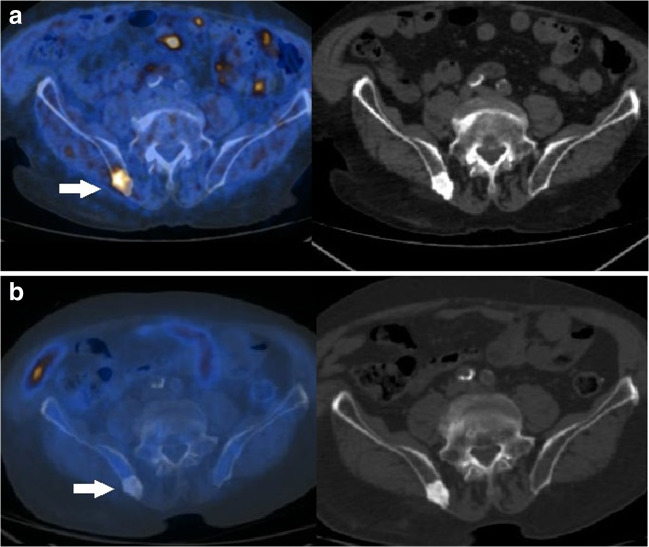

Fig. 2.

a Upper row. PET/CT with 18F-methylcholine acquired before 223Ra treatment showed highly increased tracer incorporation in a sclerotic metastasis in the right posterior iliac bone (white arrow), as well evident in the axial fused PET/CT (left) and corresponding CT (right) slices. b Lower row. PET/CT with 18F-methylcholine repeated 1 month after treatment showed no pathological uptake of the tracer in the right bone metastasis (white arrow)

We then studied the genomic locations of the breakpoints in the PML and RARA genes, which were at nucleotide positions 1708-09 of PML intron 3, respectively, outside the previously reported Topo II-associated hotspot region [2, 3]. However, the RARA breakpoint was localized at position 15828-29, in the 3′ region of intron 2, which was previously described as preferential breakpoint region in t-APL [4]. The bone marrow trephine biopsy showed extensive metastatic carcinoma with immune profile consistent with prostate primary (cytokeratin AE1/AE3, E-cadherin and PSA positive). The residual bone marrow tissue contained a discrete number of immature myeloid cells showing positivity for CD33, MPO, and CD99, in keeping with the diagnosis of synchronous APL.

We then started a chemo-free induction regimen with all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA, 45 mg/m2/day) and age-adjusted 50% dose of arsenic trioxide (ATO, 0.075 mg/kg/day). The treatment was poorly tolerated by the patient, who developed pneumonia due to Aspergillus fumigatus and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and post-traumatic bilateral subdural hemorrhage that did not require draining. Moreover, ATO was suspended twice: once for QTc prolongation, and resumed at lower dose, and afterwards for febrile neutropenia (G4). At completion of induction, the patient improved, blood counts returned to normal, and bone marrow aspiration resulted in dry tap. We performed a further bone marrow trephine biopsy still showing an extensive involvement of prostate cancer; however, APL was not identified. Therefore, maintenance with ATRA 2 weeks on and 2 weeks off was continued for APL, and enzalutamide was administered for PC.

Discussion

Secondary acute myelogenous leukemia (sAML) is a disease of elderly patients, is frequently resistant to cytotoxic chemotherapy, and has a higher relapse rate and a worse prognosis than de novo AML [5]. sAML is a heterogeneous disease, both biologically and clinically, and includes therapy-related AML (t-AML), arising after exposure to cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation therapy. t-APL is a subtype of t-AML, which has been associated with treatment with Topo II inhibitors, in particular for breast cancer or mitoxantrone [2, 6]. The pathogenesis of t-AML has been associated with two possible hypotheses: the selection by chemotherapy of a pre-existing pre-leukemic clone, associated to clonal hematopoiesis of undetermined significance (CHIP), or, alternatively, chemotherapy may promote the acquisition of the leukemic profile by accumulation of DNA mutations [7].

APL secondary to a primary malignancy (PM) accounted for 4.8% of all APLs in GIMEMA studies; 74% were t-APL, while the others did not receive any chemotherapy or radiotherapy for the treatment of their PM [8]. The median time interval between primary malignancy and sAPL was 36 months (range, 8–366 months). The latency varied depending on the type of therapy received for the PM, and it was shorter in patients who received either chemotherapy or radiotherapy than in those treated with surgery alone [8]. Most t-APL arise after chemotherapy for solid malignancies: in a series of 106 cases, the most common primary neoplasia was breast cancer (60%), followed by non-Hodgkin lymphoma (15%), Hodgkin lymphoma (2%), and 5 patients with PC; all had received radiotherapy [9]. Different from sAML, t-APL has a prognosis similar to that of de novo APL, with high rates of response and prolonged survival [10]. This finding has been confirmed both in older reports on t-APL treated with ATRA and idarubicin, and in the modern series of t-APL treated with ATRA plus ATO [11, 12].

Recently, Odo et al. reported on a patient with APL arising after exposure to 223Ra and docetaxel for metastatic PC, concluding that a causative role of 223Ra was unlikely, due to the latency of 2 years, and the specificity of APL, and not AML [13]. The PML and RARA genomic breakpoints were not characterized in this patient. In addition, Varkaris et al. reported a case of AML diagnosed 7 months after exposure to 223Ra in a patient treated with 24 Gy of radiotherapy to various bone sites and 72 Gy to the prostate bed for castration-resistant metastatic PC [14]. Differently from these two patients, who were exposed to chemotherapy (docetaxel) and radiotherapy, our patient never received any chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Apart from the association of enzalutamide with leucopenia and neutropenia, there are no data in literature regarding a possible role of antiandrogens in leukemogenesis. In the phase III AFFIRM trial of enzalutamide vs. placebo in patients with CRPC, 2 events of acute myeloid leukemia occurred in the enzalutamide arm (0.25%), but all patients were previously treated with docetaxel [15]. Therapy-independent mechanisms, including coincidence, genetic predisposition, or previous environmental exposure to carcinogens, associated with advanced age of the patient, may have played a role, but the association of 223Ra to t-APL must also be hypothesized, given also the preferential genomic localization of the RARA breakpoint in our patient. Actually, in patients treated with topoisomerase II inhibitor translocation, breakpoints are clustered in “hot spot” regions within PML and RARα genes, at sites that are susceptible to mitoxantrone cleavage [2, 6, 16]. A similar clustering of breakpoints in PML/RARα, but lying outside the mitoxantrone hot spot region, has been found after exposure to epirubicin [17]. Unfortunately, little is known on the characteristics of the PML/RARA breakpoints after exposure to radiotherapy and in the rare cases of t-APL developing after radioiodine-131, a gamma/beta emitter [18]. It has to be underlined that while beta-emitters mainly produce DNA damage through water hydrolysis and free radical formation, targeted alpha therapy presents a peculiar radiobiological mechanism, producing tumoricidal effects independently from oxygenation and cell cycle phase. Dense ionizing energy deposition due to alpha emitters can determine DNA double-strand breaks and, more importantly, multiple damage sites (MDSs), very challenging to be repaired for the cell, thus resulting in lethal or sub-lethal effects. Preliminary studies showed that point mutations plus recurring chromosomal rearrangements represent crucial steps leading to the development of t-AML [19]. In view of the above, although therapy-independent mechanisms, including coincidence, genetic predisposition, or previous environmental exposure to carcinogens, associated with advanced age, may have played a role in causing AML, the association between 223Ra-exposure with t-APL should also be considered, given the preferential genomic localization of the RARA breakpoint in our patient.

Moreover, in the randomized ALSYMPCA trial on the use of 223Ra in patients with PC, 2% of patients on the 223Ra arm experienced bone marrow failure or pancytopenia, as compared to none of the patients treated with placebo. There were two deaths due to bone marrow failure, and this complication was ongoing at the time of death in 7 of 13 patients treated with 223Ra [20]. It has to be highlighted that 223Ra-dichloride represents a recently introduced therapy; thus, the scientific literature concerning its long-term effects is still scanty. In this regard, the preliminary results of the clinical study REASSURE, aimed to evaluate the long-term safety of 223Ra therapy, have been recently published [21]. In a large cohort of 583 subjects monitored for an average observation period of 7 months (range, 0–20), the authors described hematological drug-related adverse effects in the 21% who had previously received chemotherapy and only in the 9% of those who had not previously undergone chemotherapy, being anemia the most commonly reported condition. Of note, one of the enrolled subjects was diagnosed with leukemia that led the patient to death. However, no further information was given regarding the type of leukemia and karyotypic alterations.

Moreover, it would have been interesting to verify the results of bone marrow evaluations in the patients with marrow failure reported in the ALSYMPCA trial [1] or the REASSURE study [20], to exclude other missed cases of t-AML. Physicians should be aware about the possibility of a t-AML arising in patients treated with 223Ra developing cytopenia or signs of bone marrow failure [22]. On this path, the authors call for further research to improve scientific knowledge on 223Ra-therapy long-term effects, also through multicentric Phase IV postmarketing surveillance and pharmacovigilance studies.

In conclusion, 223Ra has significantly improved overall survival in metastatic PC [1], but some cases of t-AML and of bone marrow failure have been reported. Our case underlines the importance of further marrow investigation in patients developing cytopenia following this treatment. Indeed, since APL is a highly curable leukemia using the ATRA plus ATO regimen, which has a low toxicity profile, missing this diagnosis is potentially very harmful [11]. The type of PML/RARA rearrangement we identified, in absence of other myelotoxic treatments, is suggestive of a possible direct causal relationship with exposure to 223Ra and warrants further investigations.

Acknowledgments

We thank AIRC5x1000 call “Metastatic disease: the key unmet need in oncology to MYNERVA project, #21267, Myeloid NEoplasms research venture AIRC” (Fondazione AIRC per la Ricerca sul Cancro).

We thank Dr. Francesca Mancini for the cytomorphological assistance.

Author Contributions

PS performed research; PS, OT, and FL designed and wrote the manuscript; OT and VMT performed the genetic analysis; FL provided the PET images. All the authors contributed to patient’s care. GC and VMT supervised the work.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Perrone Salvatore, Elettra Ortu La Barbera, Tiziana Ottone, Marcello Capriata, Mauro Passucci, Luca Filippi, Oreste Bagni, Maria Teresa Voso, and Giuseppe Cimino declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Salvatore Perrone, Email: sperrone@hotmail.it.

Elettra Ortu La Barbera, Email: e.ortulabarbera@hotmail.it.

Tiziana Ottone, Email: tiziana.ottone@uniroma2.it.

Marcello Capriata, Email: capriatamarcello@gmail.com.

Mauro Passucci, Email: Passucci.mauro@gmail.com.

Luca Filippi, Email: l.filippi@ausl.latina.it.

Oreste Bagni, Email: o.bagni@ausl.latina.it.

Maria Teresa Voso, Email: voso@med.uniroma2.it.

Giuseppe Cimino, Email: cimino@bce.uniroma1.it.

References

- 1.Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O'Sullivan JM, Fossa SD, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213–223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasan SK, Mays AN, Ottone T, Ledda A, La Nasa G, Cattaneo C, et al. Molecular analysis of t(15;17) genomic breakpoints in secondary acute promyelocytic leukemia arising after treatment of multiple sclerosis. Blood. 2008;112:3383–3390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-115600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ottone T, Hasan SK, Voso MT, Ledda A, Montefusco E, Fenu S, et al. Genomic analysis of therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemias arising after malignant and non-malignant disorders. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:346–347. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasan SK, Ottone T, Schlenk RF, Xiao Y, Wiemels JL, Mitra ME, et al. Analysis of t(15;17) chromosomal breakpoint sequences in therapy-related versus de novo acute promyelocytic leukemia: association of DNA breaks with specific DNA motifs at PML and RARA loci. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2010;49:726–732. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Granfeldt Ostgard LS, Medeiros BC, Sengelov H, Norgaard M, Andersen MK, Dufva IH, et al. Epidemiology and clinical significance of secondary and therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia: a national population-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3641–3649. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mistry AR, Felix CA, Whitmarsh RJ, Mason A, Reiter A, Cassinat B, et al. DNA topoisomerase II in therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliai C, Schiller G. How to address second and therapy-related acute myelogenous leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2020;188:116–128. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pulsoni A, Pagano L, Lo Coco F, Avvisati G, Mele L, Di Bona E, et al. Clinicobiological features and outcome of acute promyelocytic leukemia occurring as a second tumor: the GIMEMA experience. Blood. 2002;100:1972–1976. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaumont M, Sanz M, Carli PM, Maloisel F, Thomas X, Detourmignies L, et al. Therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2123–2137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duffield AS, Aoki J, Levis M, Cowan K, Gocke CD, Burns KH, et al. Clinical and pathologic features of secondary acute promyelocytic leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137:395–402. doi: 10.1309/AJCPE0MV0YTWLUUE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dayyani F, Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, Pierce S, Jones D, Faderl S, et al. Outcome of therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia with or without arsenic trioxide as a component of frontline therapy. Cancer. 2011;117:110–115. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kayser S, Krzykalla J, Elliott MA, Norsworthy K, Gonzales P, Hills RK, et al. Characteristics and outcome of patients with therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia front-line treated with or without arsenic trioxide. Leukemia. 2017;31:2347–2354. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Odo U, Vasudevamurthy AK, Sartor O. Acute Promyelocytic leukemia after treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with radium-223. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15:e501–e5e2. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varkaris A, Gunturu K, Kewalramani T, Tretter C. Acute myeloid leukemia after radium-223 therapy: case report. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15:e723–e7e6. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, Taplin ME, Sternberg CN, Miller K, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravandi F. Therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2011;96:493–495. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.041970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mays AN, Osheroff N, Xiao Y, Wiemels JL, Felix CA, Byl JA, et al. Evidence for direct involvement of epirubicin in the formation of chromosomal translocations in t(15;17) therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:326–330. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grudeva-Popova J, Yaneva M, Zisov K, Ananoshtev N. Therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia after treatment with radioiodine for thyroid cancer: case report with literature review. J BUON. 2007;12:129–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Christiansen DH, Desta F, Andersen MK. Alternative genetic pathways and cooperating genetic abnormalities in the pathogenesis of therapy-related myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:1943–1949. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayer HealthCare. Xofigo prescribing information. In. 2019. http://labeling.bayerhealthcare.com/html/products/pi/Xofigo_PI.pdf. Accessed 3/11/2020.

- 21.Dizdarevic S, Petersen PM, Essler M, Versari A, Bourre JC, la Fougere C, et al. Interim analysis of the REASSURE (radium-223 alpha emitter agent in non-intervention safety study in mCRPC popUlation for long-teRm evaluation) study: patient characteristics and safety according to prior use of chemotherapy in routine clinical practice. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:1102–1110. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-4261-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacene H, Gomella L, Yu EY, Rohren EM. Hematologic toxicity from radium-223 therapy for bone metastases in castration-resistant prostate cancer: risk factors and practical considerations. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16:e919–ee26. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]