Abstract

In order for treatment as prevention to work as a national strategy to contain the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States (US), the HIV care continuum must become more robust, retaining more individuals at each step. The majority of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in the US are gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM). Within this population, there are distinct race- and ethnicity-based disparities in rates of HIV infection, engagement, and retention in HIV care, and viral suppression. Compared with White MSM, HIV-infected Black MSM are less likely to be on anti-retroviral therapy (ART), adhere to ART, and achieve viral suppression. Among MSM living in urban areas, falling off the continuum may be influenced by factors beyond the individual level, with new research identifying key roles for network- and neighborhood-level characteristics. To inform multi-level and multi-component interventions, particularly to support Black MSM living in urban areas, a clearer understanding of the pathways of influence among factors at various levels of the social ecology is required. Here, we review and apply the empirical literature and relevant theoretical perspectives to develop a series of potential pathways of influence that may be further evaluated. Results of research based on these pathways may provide insights into the design of interventions, urban planning efforts, and assessments of program implementation, resulting in increased retention in care, ART adherence, and viral suppression among urban-dwelling, HIV-infected MSM.

Keywords: Men who have sex with men, Networks, Neighborhoods, HIV care continuum

Introduction

Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) comprise the largest proportion, at two-thirds, of new HIV diagnoses in the United States (US) [1, 2]. Black MSM make up 39% of new HIV infections and are thus significantly overrepresented among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) [3–5]. Poor individuals and/or individuals living in areas characterized by poverty are also over-represented among PLWHA [6, 7]. In New York City, in 2016, just 8% of new HIV cases among men were in low poverty areas, and just 12% of all PLWHA live in low poverty areas. The HIV care continuum, also known as the care cascade, is a series of sequential steps that an HIV-infected (whether known or unknown) individual takes from initial screening and confirmatory diagnosis to medical care engagement to anti-retroviral therapy (ART) adherence to full and consistent viral suppression, which results in effectively no risk of HIV transmission in serodiscordant sex without a condom or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) [8]. Each step along the continuum represents a potential point of intervention to improve health outcomes for HIV-infected persons and decrease HIV transmission [9–11].

Stark disparities in HIV care-related outcomes by race and ethnicity exist at each step of the cascade. For example, compared with White MSM, Black MSM are less likely to be engaged in care, to be on ART, adhere to ART, and to be virally suppressed [12–18]. Although nearly three-quarters (72%) of Black MSM are linked to care, less than half (46%) are retained in care. Slightly more than a third (37%) are virally suppressed [19]. HIV-infected Black MSM with detectable viral loads have been found to have drug-resistant HIV infection, and using outdated or unusual ART regimens [20]. In many urban areas, for example, New York City (NYC), the proportions of HIV-infected persons retained in care and virally suppressed are higher than those reported nationally [21]. Still, only 59% of the Black MSM estimated to be HIV-infected in NYC are retained in care and 42% achieve viral suppression [22]. Further, racial disparities in 5-year survival rates exist in both low and high poverty areas of NYC [7].

Among MSM living in urban areas, progressing along the care continuummay be influenced by factors beyond the individual level, such as network- and neighborhood-level characteristics. To inform multi-level and multi-component interventions, a clearer understanding of the pathways of influence among factors at various levels of the social ecology is required. Here, we present a series of potential pathways of influence, based on a review of the empirical literature and relevant theoretical perspectives, between the neighborhood environment and HIV care-related outcomes. It is our hope that these will provide useful heuristics for future research that will inform intervention design and implementation approaches to increasing retention in HIV care, ART adherence, and viral suppression among urban-dwelling, HIV-infected MSM. To this end, first, we briefly review the literature on individual-level factors associated with the HIV care continuum among MSM. Next, we describe what empirical research exists on neighborhood- and network-level factors and HIV continuum-related outcomes. Finally, we describe three potential pathways of influence that, with further investigation, may reveal important points of intervention and insights into implementation for HIV care continuum-related interventions, programming, and dissemination supports. Throughout, we highlight the literature on and implications for urban-dwelling, Black or African-American MSM, who are both disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS and segregated in lower income neighborhoods through discriminatory policies and practices due to socio-historical forces.

Individual-Level Correlates of the HIV Care Continuum

Research among HIV-infected populations in general has identified a myriad of factors that influence the HIV care continuum focused primarily on the individual level (e.g., mental health, substance use, incarceration history, unstable housing, low education level, attitudes, and beliefs) [11, 23–36] and the patient-provider level (e.g., cultural competency, trust, and patient-provider interactions and relationships) [36–47]. At the individual level, depression and substance use are prevalent among HIV-infected populations and represent key barriers to initial testing, access to care, retention in care, and ART adherence [48–55]. Among HIV-infected MSM, key individual-level factors that also affect the care continuum include sexual identity and “outness” [56], internalized homonegativity/heterosexism [57], syndemic conditions [53], lack of knowledge or awareness of HIV testing and testing resources [58, 59], fear (of rejection, disclosure, or both) [58, 59], experience of stigma and homophobia [60], and HIV-related stigma within gay communities [61]. Among PLWHA, diversion of ART drugs (i.e., selling or trading of ART drugs in an unregulated/informal market) is associated with poverty and competing needs [62], as well as ART non-adherence among those who are involved in this practice [63, 64].

Among Black MSM living with HIV, recent research identifies factors of particular importance to HIV care-related outcomes. Thus, among young Black, HIV-infected MSM, identity-related issues and HIV serostatus disclosure represent barriers to HIV care access, while successful transition to adulthood has been found to be associated with ART adherence [65–68]. For Black, HIV-infected MSM, provider-level cultural competency, patient-level trust, and patient-provider interactions and relationship characteristics have been identified as key drivers of retention in care [36, 38, 39, 69–73]. A growing number of studies connect experiences of racial discrimination and HIV stigma with negative HIV care and related outcomes [14, 65, 74–76]. HIV-infected Black MSM who experienced greater racial discrimination are more likely to have low adherence to HIV treatment and less likely to have a high CD4 count and undetectable viral load [74, 76]. In addition, in qualitative studies among Black, HIV-infected MSM, HIV-related stigma and homophobia were associated with non-disclosure of HIV-positive serostatus, reluctance to obtain HIV medical care, and lower adherence to ART [36, 68]. Several studies have identified additional social barriers to engagement and retention in care, such as lack of health insurance and poverty [10, 14, 36, 76, 77].

Neighborhood- and Network-Level Correlates of the HIV Care Continuum

Social ecological theory suggests that individual-level adverse health outcomes may be influenced by the neighborhood environment either directly or indirectly [78–80]. Exposures to negative neighborhood-based experiences and conditions may have direct effects on health [81–83], whereas community and neighborhood resources, including social capital (an umbrella term that captures a range of social interactions, connections, and resources that are embedded in the individuals, networks, and organizations within an area or group), may buffer against these adverse effects [84]. A growing body of research connects neighborhood factors with increased HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) risk [85–95].

Poverty and Income Inequality

Neighborhood poverty contibutes to racial disparities in HIV-related mortality [96], with a recent study reporting a relationship between neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation (including neighborhood-level measures of poverty, unemployment, low educational attainment, and median household income) and late HIV diagnosis [97]. Other research examines how neighborhood poverty and unemployment [98] and physical disorder [99] are associated with low CD4 counts and lack of medication access, and non-adherence, respectively. In NYC, a recent investigaton using surveillance data assessed whether neighborhood-level characeristics were associated with viral suppression and maintanence, with results indicating that high levels of poverty were associated with reduced maintenance of viral suppression, but not initial suppression [100]. Poverty and access to transportation may be correlated at the neighborhood level and act synergystically to influence access to care. Spatial cluster analyses have identified “hot spots” of poor care outcomes [101], with a recent study reporting evidence of significant clustering among neighborhoods in Atlanta with low levels of linkage to care and viral suppression. Another study found that the influence of neighborhood-level household vehicle ownership varied by the poverty level of the neighborhood, with vehicle access associated with greater viral suppression in low poverty areas, as compared with higher poverty areas [102]. Similarly, recent research have noted that longer commute time, using public transportation compared to private transportation, and distance to HIV provider were associated with lower rates of HIV care attendance among a sample of predominately Black, HIV-infected MSM living in Atlanta [103].

Absolute measures such as poverty do not tell the full story, however. Neighborhood-level income inequality has been found to be associated with various poor HIV-related outcomes. In a recent study of late HIV diagnosis in New York City neighborhoods, Ransome et al. (2016a) found that neighborhoods with high income inequality (highest tertile vs. lowest, based on the GINI coefficient) had higher relative risks of late HIV diagnosis compared to neighborhoods with low income inequality in unadjusted analyses [97]. Once adjusted for other neighborhood characteristics (i.e., socioeconomic deprivation, black residential concentration, HIV testing resources), the association between income inequality and late HIV diagnosis developed a scattered pattern of significance [97], suggesting that measuring income inequality alone may not be sufficient to capture neighborhood structural inequality. In a separate but related analysis, Ransome et al. (2016b) examined the associations between dimensions of social capital (defined as social cohesion, informal social control, and civic/political participation), neighborhood level structural inequality, and late HIV diagnosis in New York City neighborhoods. Similar to their earlier finding, higher levels of neighborhood-level income inequality were associated with a higher relative risk of late HIV diagnosis [104]. Income inequality did not only exert direct effects on late HIV diagnoses, but also attenuated the protective relationships between other social factors and late HIV diagnoses, such as high political participation and high informal social control and exacerbated the relationship between high social fragmentation and late HIV diagnosis,[104] all suggesting that the effects of income inequality interact with social processes to influence HIV diagnoses. In a nationwide analysis in the United States, states with high income inequality (measured by the GINI coefficient) had higher rates of AIDS (HIV stage 3) diagnosis among MSM [105].

Residential Racial Segregation

Neighborhood-level economic characteristics do not exist in a vacuum. Related, but independently important, are other structurally conditioned social characteristics, including residential segregation, and its often-used proxy measure, black residential concentration. Racial segregation has been shown to be a fundamental cause of health disparities, including gonorrhea [91], breast cancer rates [106], depression [98], and pre-term birth [107]. Residential racial segregation was maintained in the US through de facto and de jure policies in the areas of housing, education, employment, healthcare, voting, and access to public infrastructure and systems [108, 109]. Residential segregation (measured by black racial concentration) was associated with higher relative risk of late HIV diagnosis, an association that was attenuated but not removed entirely when socioeconomic deprivation and income inequality were considered, suggesting an underlying mechanism beyond economics [97]. It was also found to be associated with survival post AIDS diagnosis among non-Hispanic Blacks along several dimensions of segregation, but those associations varied by time of diagnosis. Specifically, in the pre-HAART era, no dimension of racial segregation was associated with hazards (measured by hazard ratio) of survival. During the early HAART era (1996–1998), non-Hispanic Blacks living in neighborhoods with higher levels of isolation and clustering have lower hazards of survival (hazard ratios below 1), whereas in the late HAART era (1999–2004), non-Hispanic Blacks living in neighborhoods with higher levels of centralization and concentration were more likely to survive longer (hazard ratios greater than 1) [110].

Access to and Spatial Distribution of Resources

Easy access to HIV care-related resources may be a crucial neighborhood-based influence on robust and consistent care engagement. One study, set in Philadelphia, found that access to public transit, distance to pharmacies and medical care, and economic deprivation were significantly associated with residence in geographic hot spots characterized by low levels of retention in care and viral suppression [101, 111]. A Chicago-based study found that YBMSM lived in neighborhoods with lower densities of HIV-related service organizations and that the locations and spatial clustering of these organizations correlated poorly with some of the zip codes in which YBMSM reported high rates of condomless sex [112]. This suggests a potential mismatch between recourse location and behavioral need. Neighborhood resources may have a paradoxical relationship to neighborhood-level concentrated poverty and racial segregation, with highly segregated, lower income areas having more community-based resources designed to address substance abuse and other social problems, in part due to lower community opposition to these facilities being sited there [113–115].

An intriguing new line of research is exploring how venues, both type (i.e., healthcare, other service organizations, social venues such as bars/restaurants) and their spatial distribution (i.e., whether they cluster in physical space), influence HIV-related outcomes. A recent study found that Black MSM in Chicago utilized healthcare at multiple HIV health centers (HHCs) and that the utilization patterns varied by HHC type (HHCs that offered only treatment services vs. HHCs that offered preventive services with specialized programs for HIV-positive individuals). Utilization also varied by individual-level characteristics, such as HIV status and age, and the social network characteristics, specifically size and HIV status composition, with HIV-positive Black MSM with smaller networks often using HHCs that do not provide prevention for positive programming [116]. Fujimoto et al. (2017) analyzed spatial clustering in venues that served young MSM in Chicago and Houston and reported that young MSM-serving and social organizations that were geographically clustered had highly centralized network locations (measured by centrality indegree) and engaged in competition [117]. Further research into the way in which these venues interact with other resources and care providers is warranted. This work also suggests that characteristics of both residential and care-specific neighborhoods may influence care access and related outcomes, as HIV-positive individuals may not live in the same neighborhoods where they seek HIV medical care.

Social Capital

Social capital, conceptualized here as what is transmitted across network ties, may also play an important, but complex, role. In an analysis where social capital was defined as social trust, high levels of social trust were associated with lower likelihood and rates of late HIV diagnosis across races and transmission categories; this was especially true among Black MSM relative to White MSM, across states in the USA [118]. This same study found that states with higher levels of social trust also had lower levels of all-cause mortality rates among HIV-infected MSM and injecting drug users [118]. In a related analysis, social capital was disaggregated into several constituent parts (social cohesion, civic engagement, informal social control, social fragmentation, and political participation); gender-stratified analyses found that, among men, neighborhoods with the highest levels of social cohesion and social participation had lower relative risk of late HIV diagnosis in unadjusted models, while areas with high levels of social fragmentation, income inequality, and black racial composition had higher odds of late HIV diagnoses. In adjusted models, however, when all the social capital dimensions were assessed together, neighborhoods with the highest levels of informal social control continued to have lower relative risk of late HIV diagnosis, while neighborhoods with high levels of social fragmentation continued to have elevated odds relative risk of late HIV diagnosis. Once all factors (social capital and neighborhood-level socioeconomic factors) were assessed together, neighborhoods with the highest level of civic engagement, high levels of income inequality, and high levels of black racial concentration all had higher relative risk of late HIV diagnosis, while neighborhoods with the highest levels of informal social control had lower relative risk of late HIV diagnosis [104]. Ransome et al. (2017) found that among residents of Philadelphia (organized by census tract), higher levels of social participation were associated with higher prevalence of late HIV diagnosis, higher prevalence of linkage to care, but a lower prevalence of retention in that care. Further, they found that the social cohesion was not associated with the outcomes, and social engagement was associated only with a slightly higher prevalence of residents engaged in HIV care [119]. The study was cross-sectional, however, so it is possible that the higher prevalence of late HIV diagnosis could have driven social participation and social engagement. This highlights the need not only for more nuanced research on indicators of social capital but also on longitudinal work in this area.

Social Networks

Neighborhood compositional characteristics (e.g., racial residential segregation [97, 120, 121], income inequality [97, 121], black racial concentration [97, 120], poverty [121], and low HIV service venue densities [12]) and network structures (e.g., racial diversity or lack thereof [122], awareness of HIV status [123], norms/beliefs of influential network members [124], centrality and types of venue networks [117]) may interact to influence HIV-related outcomes. Social networks can be both space/venue-centered and person/community-centered, with both potentially important to the HIV care continuum. While research has been conducted on the contribution of venue characteristics to HIV-related risk or protective behaviors [125–127], and HIV care [116, 128, 129], how neighborhood- and venue-based social networks influence the HIV care cascade is less well understood. Also poorly understood is how the venue-based social networks interact with individual- and neighborhood-level characteristics to influence HIV care-related outcomes [130]. Regardless of whether a network is venue-, neighborhood-, or social identity community-based, information, attitudinal and behavioral norms, and resources, often conceptualized as social capital, travel across network connections and both constitute and reconstitute neighborhood conditions [117].

Characteristics of social networks such as structure (size and density or the extent to which network members know one another) and composition (age, race/ethnicity, family members) may also play a role in movement along the HIV care continuum, with social networks supporting or impeding access to healthcare and medication adherence. High levels of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual networks and social support from network members, mediated by lower perceived HIV stigma and stress, have been found to be associated with improved HIV care outcomes [131–136]. Attitudes around same-sex relationships within social institutions, such as family, churches, and the larger community, may be particularly important among Black MSM and have been found to be associated with negative mental health outcomes [77, 137], which may in turn affect willingness to seek HIV prevention and care. Network stability may also be an important factor; instability due to unaffordable housing, arrests, and substance use may impede network support as well as the receipt of resources from network members. Thus, social networks provide the structure and stability for the interactions that link neighborhood conditions and characteristics to individual-level health and behavior, with networks often being interconnected within urban neighborhoods [81].

Theoretical Pathways Linking Neighborhood- and Network-Level Correlates and HIV Care-Related Outcomes

Neighborhood factors may influence the HIV care continuum through several pathways, including: (1) stress/coping pathway whereby neighborhood conditions (e.g., segregation, community violence, and physical disorder) directly produce adverse effects on mental health, substance use, or elicit other negative coping responses; (2) stigma/resilience pathway whereby neighborhood characteristics (e.g., social norms around PLWHA and LGBTQ people, social support) produce mental and other health effects and feelings of community alienation/connectedness; and (3) access/resource pathway whereby material and transit-related resources (e.g., healthcare facilities, access to transit) directly increase access to HIV medical care and related services.

The Stress/Coping Pathway

According to stress theory, experiences of stressful life events give rise to coping responses, which can be adaptive or maladaptive. When a coping response is adaptive, the impact of the stressor is mitigated; when the response either does not exist or is maladaptive, the stressor has a negative effect on the individual [138, 139]. Neighborhood environmental conditions, such as concentrated poverty, racial segregation, physical disorder, and violence, can increase the likelihood of experiencing chronic and acute stressors. Physical disorder (e.g., boarded up windows and abandoned buildings) can lead to stressful experiences, such as crimes and assault, as they provide spaces and cover for illegal activity (e.g., drug using) [51, 131, 140] and can cause general arousal or anxiety, which can have negative effects on immune function [141, 142]. In an analysis of neighborhood-level indicators of physical disorder and sexual behaviors, lower levels of physical disorder (broken/boarded-up windows) were negatively associated with serodiscordant condomless anal sex among Black (but not White) MSM, suggesting a protective effect of well-tended and homogenous neighborhoods for this group [143]. There is extensive literature on the relationship between exposure to community violence and adverse health outcomes among adolescents [144–146]. Yet, the role of exposure to community violence and HIV care outcomes among HIV-infected MSM has not been fully explored [147]. Qualitative research on adherence suggests that neighborhood-based events can lead to reduced adherence and/or negative clinical outcome [68]. Residential racial and class segregation, which are increasingly correlated [148], is associated with over-policing, which is associated with negative neighborhood-based experiences such as stress response, arrest, physical assault, and homicide among Black men in particular. Negative or traumatic neighborhood-based experiences may trigger alcohol and other drug (AOD) use, relapse, and/or negative mental health outcomes, such as major depressive episodes or anxiety disorder [149–152]. Specific to PLWHA, among low socioeconomic status (SES), substance-using HIV-infected individuals in urban South Florida, residence in a highly disordered neighborhood was associated with ART non-adherence and ART drug diversion to finance illicit drug purchases [99, 153].

Racial residential segregation in urban areas may be related to diminished educational opportunities [154], over-policing [155, 156], and other sources of stress [157]. Impacts of residential racial segregation on health outcomes via stress pathways include high blood pressure [158], pre-term birth [107], cancer [106], and disparities in self-rated health [120], among others [159]. Among MSM, segregation has been correlated with HIV incidence at the city level [121] and late HIV diagnoses among Black MSM [97]. In St. Louis, neighborhoods with higher levels of poverty, unemployment, and racial segregation were associated with lower CD4 and lower likelihood to be on ART [98]. The effects of racial segregation may be mediated or moderated by social and sexual network characteristics; living in racially segregated areas may contribute to smaller sexual networks, which in turn may contribute to higher HIV prevalence within those networks. Small tight networks, coupled with lower levels of racial mixing in sexual networks, may contribute to less choice in sexual partners, which reinforces closely knit networks, which can also contribute to rapid HIV spread within that network if it enters [122]. In contrast, residential segregation may contribute to large numbers of loose and tight ties within racially homogeneous social networks, which may buffer the negative experiences associated with racial minority group membership, such as discrimination or police brutality. These racially homogeneous social networks may provide more emotional, social, and instrumental support to mitigate the negative effects of racism.

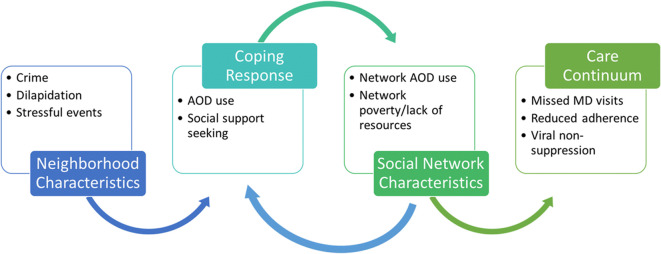

Social network characteristics may buffer or exacerbate the negative impact of these neighborhood environmental conditions, such as concentrated poverty, physical disorder, and community violence. High levels of neighborhood-level poverty may interact with networks where members use and abuse illicit drugs and may be involved in diversion of ART medications to financially support drug use [63, 64, 99, 153]. In contrast, network characteristics may provide resources to cope with stressful events or behavioral or subjective norms that support maladaptive coping responses. Figure 1 illustrates how select neighborhood characteristics may relate to network- and individual-level factors and processes along the stress/coping pathway.

Fig. 1.

Stress/coping pathway

The Stigma/Resilience Pathway

HIV/AIDS stigma is associated with significant negative health and social outcomes among PLWHA [160, 161]. HIV/AIDS stigma, in addition to being a social problem, influences the HIV care cascade by reducing access to testing [162, 163] and medical treatment [164, 165]. It also hampers uptake of biomedical prevention technologies, critical tools to interrupt HIV transmission [140, 162, 164–169]. Very little is known about how community-level HIV stigma influences HIV care-related outcomes, as most area-level indicators are at the state level or in the form of HIV criminalization. At the individual level, stigma leads to psychological distress through self-stigmatization or internalized stigma, with internalization of negative perceptions by society directed toward one’s stigmatized group [170]; this can have negative mental and physical health implications. Some neighborhoods may be more likely to welcome HIV/AIDS- and LGBTQ-related community resources and may organize collectively to create safe spaces, promoting resilience among residents with HIV, who may feel more supported in care seeking, adherence, and status disclosure.

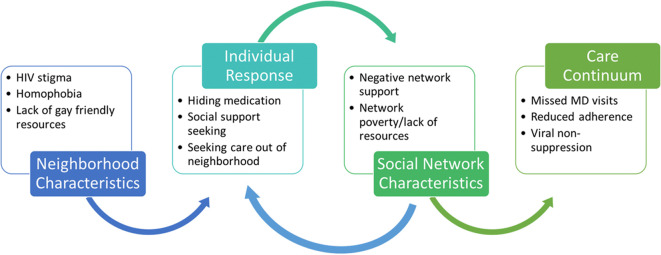

Recent research found that neighborhood-based sexual orientation-based discrimination and gay presence was associated with HIV sexual risk behaviors among MSM [164, 171, 172]. HIV stigma at the neighborhood level may influence individual-level HIV care outcomes through psychological distress and coping pathways, as well as via access to resources for PLWHA. Neighborhood homophobia may also be important to access to care and other outcomes, interacting potentially with individual-level internalized homophobia and HIV stigma. Finally, individual-level attachment to identity-based communities may buffer negative impacts [173, 174]. Social capital at the neighborhood level may also support resilience pathways, as described earlier related to residential racial segregation. Network structures may reinforce the effect of the neighborhood stigma- and discrimination-related or positive social capital characteristics. For example, neighborhoods with high levels of HIV stigma and homophobia may encourage some MSM residents to seek and maintain social ties outside of the neighborhood, thereby increasing the chances that their social networks will be loose and remote, but not influenced by neighborhood factors. Figure 2 illustrates how select neighborhood characteristics may relate to network- and individual-level factors and processes along the stigma/resilience pathway.

Fig. 2.

Stigma/resilience pathway

The Access to Resource Pathway

Access to healthcare and related needs is a core component of health system research [175], with access to prevention and treatment resources being directly related to treatment and adherence and potentially buffering the negative effects of community violence, physical disorder, and concentrated poverty [159, 176, 177]. The critical role of access to resources in AOD use-related and violence-related outcomes has been characterized [178–180]. Other than emerging data on the role of access to public or private transit and distance to services [102, 103], there is limited data on how access to community resources relate to retention in care and ART adherence among HIV-infected MSM.

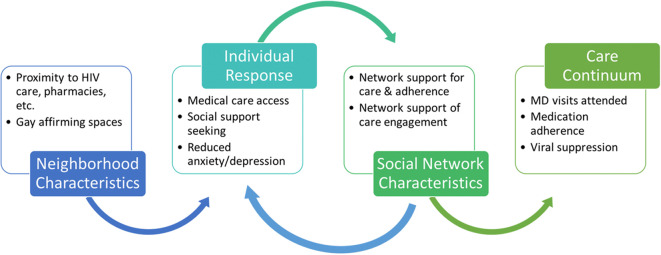

Neighborhood resources may have a paradoxical relationship to neighborhood-level concentrated poverty and racial segregation, with highly segregated, lower income areas having more community-based resources designed to address substance abuse and other social problems, in part due to lower community opposition to these facilities being sited there [113–115]. This could increase access, although how these resources interact with neighborhood-level social norms of support (for PLWHA) and individual-level attitudes (for example, internalized stigma) is unknown. Networks can influence HIV medical care via the access to resource pathway in several ways, including provision of local, resource-related information and insights (e.g., information on how and where to get HIV medical care, availability and access to local ART adherence programs). Neighborhood resources may shape network-based socially interactive pathways, such providing spaces for diffusion of behavior change (e.g., techniques to support HIV provider follow-up appointment attendance and ART adherence) across network ties within specific geographic areas [181–184]. Figure 3 illustrates how select neighborhood characteristics may relate to network- and individual-level factors and processes along the access to resources pathway.

Fig. 3.

Access to resources

Discussion

Despite a growing need to support PLWHA along the HIV care continuum, our understanding of how the urban, neighborhood environment influences HIV care outcomes, what factors connect them, and how they differ by race/ethnicity is incomplete. How network structure and composition mediate and/or moderate neighborhood characteristics to influence the HIV care continuum among HIV-infected MSM is also largely unknown. Application of stress theory, in the context of extant empirical research, suggests that concentrated poverty, racial segregation, community violence, and physical disorder may be associated with frequent and severe stressful life events and subsequently HIV care outcomes. This association may be mediated by individual-level psychological distress and moderated by coping mechanisms, with maladaptive ones (i.e., alcohol and drug use) mediating adverse neighborhood effects and positive ones (i.e., positive coping skills) buffering them. Social network characteristics, particularly social support transmitted along network connections, may buffer these associations.

Consideration of stigma and resilience theory suggests that neighborhoods with low levels of HIV stigma and homophobia may be more supportive of ART adherence, HIV serostatus disclosure, and other health-promoting behaviors among PLWHA, while also being less tolerant of stigmatizing attitudes and discriminatory behaviors of fellow residents. In contrast, residents of neighborhoods with high levels of HIV stigma and homophobia may have smaller and less supportive social networks with negative behavioral and attitudinal norms (e.g., tolerance of inconsistent ART use, negative beliefs around HIV infection and serostatus disclosure, HIV conspiracy beliefs) [185, 186]. Neighborhood social capital may support resilient responses as well; for example, neighborhoods with high levels of trust and social norms that welcome PLWHA and other stigmatized social groups, such as MSM, there may be more disclosure of status and/or sexual orientation.

Finally, when considering the role of neighborhood material resources and transit access in a dense, urban environment, it is reasonable to posit that distance to transit, care providers, and pharmacies may be associated with retention in care and adherence, with network-level factors, such as instrumental social support moderating associations. Consideration of this pathway opens up an examination of how material resource and infrastructural (e.g., transit) distribution across neighborhoods may interact with neighborhood race- and social class-based composition to influence HIV care-related outcomes in urban settings. Disentangling how social class- and race-based segregation influence HIV-related care behavior and outcomes is increasingly important, as social class-based segregation [187] and gentrification [188] of historically Black urban neighborhoods has increased since the turn of the last century. A comprehensive understanding of pathways by which neighborhood- and network-level factors influence HIV care outcomes among MSM also requires investigation into the full range of urban neighborhood contexts that MSM may experience, including those beyond residential neighborhoods, such as medical care neighborhoods [96, 98, 99, 111, 189–193]. It is likely that neighborhood influences on care-related outcomes are not limited to residential neighborhoods, but may also include the characteristics of where care is received. Similarly, the concentration of HIV in high poverty areas and among Black MSM also requires the application of intersectional and contextual approaches that evaluate how social class and race intersect at both the individual and neighborhood levels to affect HIV care-related outcomes [108].

Also important is an understanding of the spatial distribution of and relations among outcomes and characteristics that overcome limitations of traditional neighborhood-level research [78, 194–196]. Blended methods, such as spatial statistical analyses and multi-level modeling, are needed to identify the location and scale of multiple neighborhoods that are potentially important to MSM and relations among neighborhood characteristics and outcomes [81, 126]. The frameworks and conceptual models presented here highlight the continuing need to collect both multilevel and longitudinal data. Traditional epidemiologic analytic methods are well suited when variable relationships are unidirectional, with well-defined endogenous and exogenous variables [197]. Other methods, such as structural equation modeling (SEM) and latent variable analysis, expand the ability to study complicated relationships over traditional regression methods, but use of these methods still leaves unanswerable questions (i.e., interference, latency, and feedback loops) [197, 198].

The conceptual models presented here represent complex systems; as such, they require different analytic methods. Complex systems are those that are made up of heterogeneous elements that may exist at multiple levels of influence, that these elements interact with each other creating unique effects that differ from the effects of the individual elements, and that these effects persist over time and can potentially adapt to shifting circumstances [198]. To understand complex systems, both a different perspective and different methods will be required [199]. By focusing on the system, we must focus on the relationships between the elements rather than the characteristics of those elements [200]. There are several analytic methods that may be useful under this paradigm including systems dynamics, network analysis, and agent-based modeling [197, 198, 200]. Systems dynamics is based on the principle that the complex behaviors of a system result from the interplay of feedback loops, latency periods, and shifting population needs over time [198]. Network analysis focuses on the patterns of and relationships between elements (i.e., individuals in a kin/friendship network, organizations, countries) [200]. This type of relational analysis allows for the understanding of how network members influence (and are influenced by) each other, and can be used to study how social phenomena move through a network and influence health. Finally, agent-based modeling uses computer simulation of individuals (knowns as “agents”) in simulated time and space. These agents interact with their environment and each other and these interactions give rise to macrosocial processes. In turn, agents are influenced by the macrosocial processes and the environment and can adapt behaviors as a result [200]. Agent-based modeling could be helpful in elucidating the processes hypothesized in this paper because individual behavior is complex; individuals are capable of learning and adapting, are not static in space or time, they do not make decisions in a vacuum (are influenced by and influence kin/friendship networks), and both respond to and influence the macrosocial processes within they live.

In combination, such information and approaches would inform the development of interventions that focus on malleable contextual—neighborhood and network—characteristics. These interventions could act to reduce HIV stigma, discrimination, and homophobia through structural interventions and/or media campaigns in specific neighborhoods; they could encourage HIV serostatus disclosure, ART adherence, and retention in care within social networks through peer or opinion leaders. They could focus on integrating care for HIV, substance use, and mental health, with employment and housing programming; developing standardized procedures for dispensing ART drugs across payers, providers, and pharmacies to decrease potential for ART drug diversion; and enhancing health system navigation assistance through technology-based intervention, peer navigators, and combination approaches. Interventions that may be suggested by the results of such research also include urban planning-based interventions to improve the physical and social conditions of the neighborhoods with high HIV prevalence, focusing on de-concentration of poverty, racial integration, public transit patterns, crime reduction, and improvements in greenspace and housing stock. As well, housing interventions that actively house PLWHA in diverse, ordered, and higher income neighborhoods may be suggested by results of research into these pathways of potential influence.

Conclusions

To make the treatment as prevention strategy work and to reduce racial disparities in HIV care-related outcomes in urban settings, innovative, multilevel approaches are needed that will maximize the impact of ART. Because of the significant racial disparities in outcomes in such settings, we must also understand whether and how neighborhood and network characteristics uniquely act and interact to influence care outcomes among Black MSM, a subpopulation with particularly adverse HIV care-related outcomes. Given the very limited data available on neighborhood and network dynamics among HIV-infected MSM, we have attempted here to elucidate the different mechanisms by which neighborhoods and networks impact the HIV care continuum. Potentially forthcoming changes to the Affordable Care Act and related state- and city-level health and social policies may also influence how neighborhood and networks combine to influence HIV care outcomes. Identifying malleable characteristics that are amenable to both traditional individual-level intervention and novel multilevel approaches is needed as well.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers for their helpful comments on this paper. Grant Information: R56 MH110176-01A1.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2015-vol-27.pdf. Accessed 29 Dec 2016, 2016.

- 2.Wejnert C, Le B, Rose CE, Oster AM, Smith AJ, Zhu J. HIV infection and awareness among men who have sex with men-20 cities, United States, 2008 and 2011. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21(15):2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Racial/ethnic disparities in diagnoses of HIV/AIDS—33 states, 2001–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(9):189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2013; vol. 25. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/. Accessed 13 Aug 2015.

- 6.Prevention. CfDCa Characteristics associated with HIV infection among heterosexuals in urban areas with high AIDS prevalence—24 cities, United States, 2006–2007. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(31):1045–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unit HEaFS. HIV Surveillance Anuual Report, 2016. New York, NY December 2017 2017.

- 8.Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, et al. Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 2016;316(2):171–181. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stricker SM, Fox KA, Baggaley R, et al. Retention in care and adherence to ART are critical elements of HIV care interventions. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(Suppl 5):S465–S475. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0598-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Horn T, Thompson MA. The state of engagement in HIV care in the United States: from cascade to continuum to control. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(8):1164–1171. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horstmann E, Brown J, Islam F, Buck J, Agins BD. Retaining HIV-infected patients in care: where are we? Where do we go from here? Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(5):752–761. doi: 10.1086/649933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maulsby C, Millett G, Lindsey K, et al. HIV among Black men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: a review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):10–25. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchacz K, Baker RK, Palella FJ, Jr, et al. Disparities in prevalence of key chronic diseases by gender and race/ethnicity among antiretroviral-treated HIV-infected adults in the US. Antivir Ther. 2013;18(1):65–75. doi: 10.3851/IMP2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beer L, Oster AM, Mattson CL, Skarbinski J, Medical Monitoring P Disparities in HIV transmission risk among HIV-infected black and white men who have sex with men, United States, 2009. AIDS. 2014;28(1):105–114. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P, et al. Differences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(14):1337–1344. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hightow-Weidman LB, Jones K, Phillips G, 2nd, Wohl A, Giordano TP, Group YoCSIS Baseline clinical characteristics, antiretroviral therapy use, and viral load suppression among HIV-positive young men of color who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(Suppl 1):S9–14. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Axelrad JE, Mimiaga MJ, Grasso C, Mayer KH. Trends in the spectrum of engagement in HIV care and subsequent clinical outcomes among men who have sex with men (MSM) at a Boston community health center. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(5):287–296. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiteside YO, Cohen SM, Bradley H, et al. Progress along the continuum of HIV care among blacks with diagnosed HIV—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(5):85–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen I, Connor MB, Clarke W, Marzinke MA, Cummings V, Breaud A, et al. Antiretroviral drug use and HIV drug resistance among HIV-infected Black men who have sex with men: HIV Prevention Trials Network 061. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(4):446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Torian LV, Xia Q, Wiewel EW. Retention in care and viral suppression among persons living with HIV/AIDS in New York City, 2006-2010. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):e24–e29. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torian L. The continuum of care for persons with HIV in New York City in 2012: all persons, MSM by race and overall, and blacks, Hispanics, and whites. Pers Commun. 2014.

- 23.Leyro TM, Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO. Examining associations between cognitive-affective vulnerability and HIV symptom severity, perceived barriers to treatment adherence, and viral load among HIV-positive adults. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(1):139–148. doi: 10.1007/s12529-014-9404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham CO, Buck J, Shaw FM, Spiegel LS, Heo M, Agins BD. Factors associated with returning to HIV care after a gap in care in New York State. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(4):419–427. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pecoraro A, Royer-Malvestuto C, Rosenwasser B, et al. Factors contributing to dropping out from and returning to HIV treatment in an inner city primary care HIV clinic in the United States. AIDS Care. 2013;25(11):1399–1406. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.772273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodward EN, Pantalone DW. The role of social support and negative affect in medication adherence for HIV-infected men who have sex with men. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012;23(5):388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halkitis PN, Perez-Figueroa RE, Carreiro T, Kingdon MJ, Kupprat SA, Eddy J. Psychosocial burdens negatively impact HIV antiretroviral adherence in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men aged 50 and older. AIDS Care. 2014;26(11):1426–1434. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.921276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurtz SP, Buttram ME, Surratt HL. Vulnerable infected populations and street markets for ARVs: potential implications for PrEP rollout in the USA. AIDS Care. 2014;26(4):411–415. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.837139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blumenthal J, Haubrich R, Jain S, et al. Factors associated with high transmission risk and detectable plasma HIV RNA in HIV-infected MSM on ART. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(10):734–741. doi: 10.1177/0956462413518500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelsen A, Gupta S, Trautner BW, et al. Intention to adhere to HIV treatment: a patient-centred predictor of antiretroviral adherence. HIV Med. 2013;14(8):472–480. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torian LV, Wiewel EW. Continuity of HIV-related medical care, New York City, 2005-2009: do patients who initiate care stay in care? AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(2):79–88. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Traeger L, O'Cleirigh C, Skeer MR, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Risk factors for missed HIV primary care visits among men who have sex with men. J Behav Med. 2012;35(5):548–556. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9383-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kyser M, Buchacz K, Bush TJ, et al. Factors associated with non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in the SUN study. AIDS Care. 2011;23(5):601–611. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.525603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosen MI, Black AC, Arnsten JH, et al. Association between use of specific drugs and antiretroviral adherence: findings from MACH 14. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):142–147. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King RM, Vidrine DJ, Danysh HE, et al. Factors associated with nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive smokers. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(8):479–485. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Remien RH, Bauman LJ, Mantell JE, et al. Barriers and facilitators to engagement of vulnerable populations in HIV primary care in New York City. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(Suppl 1):S16–S24. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whetten K, Leserman J, Whetten R, et al. Exploring lack of trust in care providers and the government as a barrier to health service use. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):716–721. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saha S, Jacobs EA, Moore RD, Beach MC. Trust in physicians and racial disparities in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24(7):415–420. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beach MC, Saha S, Korthuis PT, et al. Patient-provider communication differs for black compared to white HIV-infected patients. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):805–811. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9664-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magnus M, Herwehe J, Murtaza-Rossini M, et al. Linking and retaining HIV patients in care: the importance of provider attitudes and behaviors. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(5):297–303. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollini RA, Blanco E, Crump C, Zuniga ML. A community-based study of barriers to HIV care initiation. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(10):601–609. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holtzman CW, Shea JA, Glanz K, et al. Mapping patient-identified barriers and facilitators to retention in HIV care and antiretroviral therapy adherence to Andersen’s behavioral model. AIDS Care. 2015;27(7):817–828. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1009362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dang BN, Westbrook RA, Black WC, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Giordano TP. Examining the link between patient satisfaction and adherence to HIV care: a structural equation model. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torian LV, Wiewel EW, Liu KL, Sackoff JE, Frieden TR. Risk factors for delayed initiation of medical care after diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(11):1181–1187. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Philbin MM, Tanner AE, Duval A, Ellen J, Kapogiannis B, Fortenberry JD. Linking HIV-positive adolescents to care in 15 different clinics across the United States: creating solutions to address structural barriers for linkage to care. AIDS Care. 2014;26(1):12–19. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.808730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dang BN, Westbrook RA, Hartman CM, Giordano TP. Retaining HIV patients in care: the role of initial patient care experiences. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(10):2477–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Graham JL, Shahani L, Grimes RM, Hartman C, Giordano TP. The influence of trust in physicians and trust in the healthcare system on linkage, retention, and adherence to HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(12):661–667. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halkitis PN, Shrem MT, Zade DD, Wilton L. The physical, emotional and interpersonal impact of HAART: exploring the realities of HIV seropositive individuals on combination therapy. J Health Psychol. 2005;10(3):345–358. doi: 10.1177/1359105305051421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cunningham CO, Sohler NL, Berg KM, Shapiro S, Heller D. Type of substance use and access to HIV-related health care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20(6):399–407. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sohler NL, Wong MD, Cunningham WE, Cabral H, Drainoni ML, Cunningham CO. Type and pattern of illicit drug use and access to health care services for HIV-infected people. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S68–S76. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turner BJ, Fleishman JA, Wenger N, et al. Effects of drug abuse and mental disorders on use and type of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:625–633. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parsons JT, Rosof E, Mustanski B. Patient-related factors predicting HIV medication adherence among men and women with alcohol problems. J Health Psychol. 2007;12(2):357–370. doi: 10.1177/1359105307074298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Biello KB, Oldenburg CE, Safren SA, et al. Multiple syndemic psychosocial factors are associated with reduced engagement in HIV care among a multinational, online sample of HIV-infected MSM in Latin America. AIDS Care. 2016;28(Suppl 1):84–91. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1146205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White JM, Gordon JR, Mimiaga MJ. The role of substance use and mental health problems in medication adherence among HIV-infected MSM. LGBT Health. 2014;1(4):319–322. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Grasso C, et al. Substance use among HIV-infected patients engaged in primary care in the United States: findings from the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems cohort. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1457–1467. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Christopoulos KA, Das M, Colfax GN. Linkage and retention in HIV care among men who have sex with men in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(suppl_2):S214–S222. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson MO, Carrico AW, Chesney MA, Morin SF. Internalized heterosexism among HIV-positive, gay-identified men: implications for HIV prevention and care. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(5):829. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pharr JR, Lough NL, Ezeanolue EE. Barriers to HIV testing among young men who have sex with men (MSM): experiences from Clark County, Nevada. Glob J Health Sci. 2016;8(7):9. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n7p9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Washington TA, D’Anna L, Meyer-Adams N, Malotte CK. From their voices: barriers to HIV testing among black men who have sex with men remain. Paper presented at: Healthcare, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Arreola S, Hebert P, Makofane K, Beck J, Ayala G. Access to HIV prevention and treatment for men who have sex with men: finding from the 2012 global mens health and rights survey (GMHR). Paper presented at: Oakland, CA: The Global Forum on MSM & HIV (MSMGF), 2012.

- 61.Smit PJ, Brady M, Carter M, et al. HIV-related stigma within communities of gay men: a literature review. AIDS Care. 2012;24(4):405–412. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.613910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalichman SC, Hernandez D, Kegler C, Cherry C, Kalichman MO, Grebler T. Dimensions of poverty and health outcomes among people living with HIV infection: limited resources and competing needs. J Community Health. 2015;40(4):702–708. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9988-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsuyuki K, Surratt HL. Antiretroviral drug diversion links social vulnerability to poor medication adherence in substance abusing populations. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(5):869–881. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0969-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsuyuki K, Surratt HL, Levi-Minzi MA, O'Grady CL, Kurtz SP. The demand for antiretroviral drugs in the illicit marketplace: implications for HIV disease management among vulnerable populations. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(5):857–868. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0856-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jeffries WL, Townsend ES, Gelaude DJ, Torrone EA, Gasiorowicz M, Bertolli J. HIV stigma experienced by young men who have sex with men (MSM) living with HIV infection. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27(1):58–71. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2015.27.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hussen SA, Andes K, Gilliard D, Chakraborty R, Del Rio C, Malebranche DJ. Transition to adulthood and antiretroviral adherence among HIV-positive young Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):725–731. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hussen SA, Harper GW, Bauermeister JA, Hightow-Weidman LB. Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIVAI. Psychosocial influences on engagement in care among HIV-positive young black gay/bisexual and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(2):77–85. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arnold EA, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. ‘Triply cursed’: racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young Black gay men. Cult Health Sex. 2014;16(6):710–722. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.905706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bogart LM, Wagner G, Galvan FH, Banks D. Conspiracy beliefs about HIV are related to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence among African American men with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(5):648–655. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c57dbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gaston GB. African-Americans’ perceptions of health care provider cultural competence that promote HIV medical self-care and antiretroviral medication adherence. AIDS Care. 2013;25(9):1159–1165. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.752783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hightow-Weidman LB, Jones K, Wohl AR, et al. Early linkage and retention in care: findings from the outreach, linkage, and retention in care initiative among young men of color who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(Suppl 1):S31–S38. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davila JA, Miertschin N, Sansgiry S, Schwarzwald H, Henley C, Giordano TP. Centralization of HIV services in HIV-positive African-American and Hispanic youth improves retention in care. AIDS Care. 2013;25(2):202–206. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.689811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gillman J, Davila J, Sansgiry S, et al. The effect of conspiracy beliefs and trust on HIV diagnosis, linkage, and retention in young MSM with HIV. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):36–45. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bogart LM, Landrine H, Galvan FH, Wagner GJ, Klein DJ. Perceived discrimination and physical health among HIV-positive Black and Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1431–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0397-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Landrine H, Klein DJ, Sticklor LA. Perceived discrimination and mental health symptoms among Black men with HIV. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2011;17(3):295–302. doi: 10.1037/a0024056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Klein DJ. Longitudinal relationships between antiretroviral treatment adherence and discrimination due to HIV-serostatus, race, and sexual orientation among African-American men with HIV. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(2):184–190. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9200-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Levy ME, Wilton L, Phillips G, 2nd, et al. Understanding structural barriers to accessing HIV testing and prevention services among black men who have sex with men (BMSM) in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):972–996. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0719-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–1789. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cubbin C, Sundquist K, Ahlen H, Johansson SE, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Neighborhood deprivation and cardiovascular disease risk factors: protective and harmful effects. Scand J Public Health. 2006;34(3):228–237. doi: 10.1080/14034940500327935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cohen DA, Farley TA, Mason K. Why is poverty unhealthy? Social and physical mediators. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(9):1631–1641. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Latkin CA, German D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Neighborhoods and HIV: a social ecological approach to prevention and care. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):210–224. doi: 10.1037/a0032704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ivy W, 3rd, Miles I, Le B, Paz-Bailey G. Correlates of HIV infection among African American women from 20 cities in the United States. AIDS Behav. Sep 28 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Galster GC. The mechanism(s) of neighborhood effects: theory, evidence, and policy implications. ESRC Seminar: “Neighbourhood effects: theory & evidence”. Scotland: St. Andrews University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Reilly KH, Neaigus A, Jenness SM, Hagan H, Wendel T, Gelpi-Acosta C. High HIV prevalence among low-income, Black women in New York City with self-reported HIV negative and unknown status. J Women's Health (Larchmt) 2013;22(9):745–754. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Johns MM, Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA. Individual and neighborhood correlates of HIV testing among African American youth transitioning from adolescence into young adulthood. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(6):509–522. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.6.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cohen D, Spear S, Scribner R, Kissinger P, Mason K, Wildgen J. “Broken windows” and the risk of gonorrhea. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(2):230–236. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA, Caldwell CH. Neighborhood disadvantage and changes in condom use among African American adolescents. J Urban Health. 2011;88(1):66–83. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9506-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Latkin CA, Curry AD, Hua W, Davey MA. Direct and indirect associations of neighborhood disorder with drug use and high-risk sexual partners. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(6 Suppl):S234–S241. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schroeder JR, Latkin CA, Hoover DR, Curry AD, Knowlton AR, Celentano DD. Illicit drug use in one’s social network and in one’s neighborhood predicts individual heroin and cocaine use. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11(6):389–394. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Biello KB, Kershaw T, Nelson R, Hogben M, Ickovics J, Niccolai L. Racial residential segregation and rates of gonorrhea in the United States, 2003-2007. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1370–1377. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ford JL, Browning CR. Neighborhoods and infectious disease risk: acquisition of chlamydia during the transition to young adulthood. J Urban Health. 2014;91(1):136–150. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9792-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cubbin C, Brindis CD, Jain S, Santelli J, Braveman P. Neighborhood poverty, aspirations and expectations, and initiation of sex. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(4):399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pouget ER, Kershaw TS, Niccolai LM, Ickovics JR, Blankenship KM. Associations of sex ratios and male incarceration rates with multiple opposite-sex partners: potential social determinants of HIV/STI transmission. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):70–80. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Phillips G, 2nd, Birkett M, Kuhns L, Hatchel T, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. Neighborhood-level associations with HIV infection among young men who have sex with men in Chicago. Arch Sex Behav. Jul 14 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Arnold M, Hsu L, Pipkin S, McFarland W, Rutherford GW. Race, place and AIDS: the role of socioeconomic context on racial disparities in treatment and survival in San Francisco. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(1):121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ransome Y, Kawachi I, Braunstein S, Nash D. Structural inequalities drive late HIV diagnosis: the role of black racial concentration, income inequality, socioeconomic deprivation, and HIV testing. Health Place. 2016;42:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shacham E, Lian M, Onen NF, Donovan M, Overton ET. Are neighborhood conditions associated with HIV management? HIV Med. 2013;14(10):624–632. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Levi-Minzi MA, Chen M. Environmental influences on HIV medication adherence: the role of neighborhood disorder. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):1660–1666. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wiewel EW, Borrell LN, Jones HE, Maroko AR, Torian LV. Neighborhood characteristics associated with achievement and maintenance of HIV viral suppression among persons newly diagnosed with HIV in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2017:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 101.Eberhart MG, Yehia BR, Hillier A, et al. Behind the cascade: analyzing spatial patterns along the HIV care continuum. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(Suppl 1):S42–S51. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a90112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Goswami ND, Schmitz MM, Sanchez T, et al. Understanding local spatial variation along the care continuum: the potential impact of transportation vulnerability on HIV linkage to care and viral suppression in high-poverty areas, Atlanta, Georgia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(1):65–72. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dasgupta S, Kramer MR, Rosenberg ES, Sanchez TH, Reed L, Sullivan PS. The effect of commuting patterns on HIV care attendance among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Atlanta, Georgia. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2015;1(2):1–11. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ransome Y, Galea S, Pabayo R, Kawachi I, Braunstein S, Nash D. Social capital is associated with late HIV diagnosis: an ecological analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(2):213–221. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Forsyth AD, Valdiserri RO. A state-level analysis of social and structural factors and HIV outcomes among men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27(6):493–504. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2015.27.6.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Landrine H, Corral I, Lee JG, Efird JT, Hall MB, Bess JJ. Residential segregation and racial cancer disparities: a systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 107.Margerison-Zilko C, Perez-Patron M, Cubbin C. Residential segregation, political representation, and preterm birth among US-and foreign-born Black women in the US 2008–2010. Health Place. 2017;46:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):936–944. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Alexander M. The new Jim Crow. Ohio St J Crim L. 2011;9:7. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fennie KP, Lutfi K, Maddox LM, Lieb S, Trepka MJ. Influence of residential segregation on survival after AIDS diagnosis among non-Hispanic blacks. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(2):113–119.e111. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Eberhart MG, Yehia BR, Hillier A, et al. Individual and community factors associated with geographic clusters of poor HIV care retention and poor viral suppression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(Suppl 1):S37–S43. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pierce SJ, Miller RL, Morales MM, Forney J. Identifying HIV prevention service needs of African American men who have sex with men: an application of spatial analysis techniques to service planning. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13:S72–S79. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200701001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Takahashi LM. The socio-spatial stigmatization of homelessness and HIV/AIDS: toward an explanation of the NIMBY syndrome. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(6):903–914. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Takahashi LM. Stigmatization, HIV/AIDS, and communities of color: exploring response to human service facilities. Health Place. 1997;3(3):187–199. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(97)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tempalski B, Friedman R, Keem M, Cooper H, Friedman SR. NIMBY localism and national inequitable exclusion alliances: the case of syringe exchange programs in the United States. Geoforum. 2007;38(6):1250–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schneider JA, Walsh T, Cornwell B, Ostrow D, Michaels S, Laumann EO. HIV health center affiliation networks of Black men who have sex with men: disentangling fragmented patterns of HIV prevention service utilization. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(8):598. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182515cee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Fujimoto K, Turner R, Kuhns LM, Kim JY, Zhao J, Schneider JA. Network centrality and geographical concentration of social and service venues that serve young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2017:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 118.Ransome Y, Batson A, Galea S, Kawachi I, Nash D, Mayer KH. The relationship between higher social trust and lower late HIV diagnosis and mortality differs by race/ethnicity: results from a state-level analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21442. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.01/21442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ransome Y, Kawachi I, Dean LT. Neighborhood social capital in relation to late HIV diagnosis, linkage to HIV care, and HIV care engagement. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(3):891–904. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1581-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yang T-C, Zhao Y, Song Q. Residential segregation and racial disparities in self-rated health: how do dimensions of residential segregation matter? Soc Sci Res. 2017;61:29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Buot M-LG, Docena JP, Ratemo BK, et al. Beyond race and place: distal sociological determinants of HIV disparities. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e91711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Raymond HF, McFarland W. Racial mixing and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):630–637. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fuqua V, Chen Y-H, Packer T, et al. Using social networks to reach Black MSM for HIV testing and linkage to care. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):256–265. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9918-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Schneider JA, Cornwell B, Ostrow D, et al. Network mixing and network influences most linked to HIV infection and risk behavior in the HIV epidemic among black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):e28–e36. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Woods WJ, Euren J, Pollack LM, Binson D. HIV prevention in gay bathhouses and sex clubs across the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S88. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbca1b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tobin KE, Latkin CA, Curriero FC. An examination of places where African American men who have sex with men (MSM) use drugs/drink alcohol: a focus on social and spatial characteristics. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pollack LM, Woods WJ, Blair J, Binson D. Presence of an HIV testing program lowers the prevalence of unprotected insertive anal intercourse inside a gay bathhouse among HIV-negative and HIV-unknown patrons. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv. 2014;13(3):306–323. doi: 10.1080/15381501.2013.864175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Johnson RL, Botwinick G, Sell RL, et al. The utilization of treatment and case management services by HIV-infected youth. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(2):31–38. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Magnus M, Jones K, Phillips G, et al. Characteristics associated with retention among African American and Latino adolescent HIV-positive men: results from the outreach, care, and prevention to engage HIV-seropositive young MSM of color special project of national significance initiative. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(4):529–536. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b56404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tobin KE, Latkin CA. Social networks of HIV positive gay men: their role and importance in HIV prevention. Understanding prevention for HIV positive gay men. Berlin: Springer; 2017. pp. 349–366. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wohl AR, Galvan FH, Myers HF, et al. Do social support, stress, disclosure and stigma influence retention in HIV care for Latino and African American men who have sex with men and women? AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1098–1110. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9833-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Persson L, Ostergren PO, Hanson BS, Lindgren A, Naucler A. Social network, social support and the rate of decline of CD4 lymphocytes in asymptomatic HIV-positive homosexual men. Scand J Public Health. 2002;30(3):184–190. doi: 10.1080/14034940210133870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Goldenberg T, Stephenson R. “The more support you have the better”: partner support and dyadic HIV care across the continuum for gay and bisexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(Suppl 1):S73–S79. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Burgoyne R. Exploring direction of causation between social support and clinical outcome for HIV-positive adults in the context of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care. 2005;17(1):111–124. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331305179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]