Abstract

One male and one female dog were presented with giant kidney worm infection in the right kidney. Infection was identified through visualization of intra-renal Dioctophyme renale on abdominal ultrasound. Both dogs underwent right-sided laparoscopic ureteronephrectomy for treatment of the giant kidney worm infection. Additional adult worms were extirpated from the peritoneal cavity of both dogs. Both dogs recovered without complication from anesthesia and surgery and were discharged within 24 hours after surgery. Laparoscopic ureteronephrectomy has not previously been described for the treatment of giant kidney worm infection in North America.

Résumé

Urétéro-néphrectomie laparoscopique pour le traitement d’une infection par le ver géant du rein chez deux chiens. Un chien mâle et un chien femelle furent présentés avec une infection par le ver géant du rein dans le rein droit. L’infection fut identifiée par visualisation de Dioctophyme renale intra-rénal par échographie abdominale. Les deux chiens furent soumis à une urétéro-néphrectomie laparoscopique pour le traitement de l’infection par le ver géant du rein. Des vers adultes additionnels furent retirés de la cavité péritonéale des deux chiens. Les deux chiens ont récupéré sans complication de l’anesthésie et de la chirurgie et ont obtenu leur congé en moins de 24 h après la chirurgie. L’urétéro-néphrectomie laparoscopique n’avait pas encore été décrite en Amérique du Nord pour le traitement de l’infection par le ver géant du rein.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Dioctophyme renale, commonly known as the giant kidney worm, is a nematode that occasionally infects dogs. The giant kidney worm has an indirect life cycle; once a definitive host is infected the adult worms typically reside in the right kidney (1,2). The natural definitive host is the mink (Mustela vison) and once infection is established, eggs are shed in the urine. The eggs are then consumed by the intermediate hosts [aquatic oligochaetes (Lumbriculus variegatus)] in which they develop to third-stage larvae; intermediate hosts may then be consumed by fish and frogs which act as paratenic hosts. Definitive hosts become infected when they ingest infected oligochaetes, fish, or frogs (1,2), and the pre-patent period is 120 to 155 d. After ingestion, D. renale larvae penetrate the duodenal wall and migrate via the liver to the right kidney where maturation occurs (2,3). Other sites of infection can occur, typically the abdominal cavity or elsewhere within the urinary tract (4). When found outside of the kidney, the infection is defined as being ectopic, and in South America where infection is considered endemic, worms are commonly discovered during routine surgical procedures such as castration, ovariohysterectomy, or exploratory laparotomy (4). A unilaterally infected kidney typically results in sub-clinical infection (5), or development of non-specific clinical signs. In cases of ectopic infection, the clinical signs are associated with the location at which the parasite is found (4,5). There is no effective drug therapy for treatment of dioctophymosis, and nephrotomy or nephrectomy is required to remove the worm and prevent subsequent destruction of renal parenchyma (3).

The objective of this case report was to describe clinical findings, surgical treatment, and outcome in 2 dogs that underwent laparoscopic ureteronephrectomy for the treatment of right kidney dioctophymosis and pre-scrotal castration for treatment of ectopic D. renale infection. To the authors’ knowledge, there are no similar reports for dogs that have experienced D. renale infection in North America; however, laparoscopic nephrectomy procedures have previously been described for dogs infected in Brazil (6,7).

Case descriptions

Case 1

A 9-year-old, male, mixed-breed dog from northern Manitoba, Canada underwent routine health screening prior to rehoming. Serum biochemistry revealed elevated urea [14.9 mmol/L, reference range (RR): 3.2 to 11.0 mmol/L], normal creatinine (108 μmol/L, RR: 44 to 133 μmol/L) and elevated amylase (1635 IU/L, RR: 337 to 1469 IU/L). Symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) was elevated (21 μg/dL, RR: 0 to 14 μg/dL) alongside an elevation in the urine protein:creatinine ratio (0.4, RR: 0.0 to 0.2). Concurrent urinalysis showed a urine specific gravity (USG) of 1.025 with presence of blood (2+), 20 to 30 white blood cells (WBC) per high powered field (hpf ) and 15 to 20 red blood cells (RBC) per hpf. The dog was sero-positive to Borrelia burgdorferi (IDEXX Snap 4Dx Plus; IDEXX, Markham, Ontario) and antibodies to B. burgdorferi were elevated on IDEXX Lyme Quant C6 Antibody testing (210 U/mL, RR: 0 to 30 U/mL). Though the dog was not showing clinical signs of Lyme disease, a 1-month course of doxycycline was initiated. A repeat urinalysis 3 wk after the first evaluation revealed a USG of 1.026, 30 to 50 RBC per hpf and many Dioctophyme renale eggs. Following identification of the D. renale eggs, an abdominal ultrasound examination demonstrated at least 1 D. renale worm in the right kidney. The dog was referred to the Ontario Veterinary College-Health Sciences Centre (OVC-HSC) for surgical treatment.

Upon presentation to the OVC-HSC the dog was quiet, alert, and responsive with normal vital parameters. Thoracic auscultation, abdominal palpation, and peripheral lymph node evaluation were unremarkable. Upon rectal examination, there was an enlarged, symmetrical, non-painful prostate and the dog had generalized seborrheic dermatitis and muscle wasting (body condition score 3/9). In the preceding 24 h the dog had become polydipsic and on the day of presentation had developed gross hematuria which had not previously been observed. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Ultrasonographic examination of the urogenital tract was performed. The right renal parenchyma was nearly completely obliterated, leaving only a thin rim of cortical tissue at the periphery. Within this saccular kidney was a large, tubular, hypoechoic structure with hyperechoic walls, consistent with an adult female kidney worm (D. renale). Two similar but smaller structures were also found that were consistent with male kidney worms (D. renale). One was present coiled in the scrotum and caused displacement and compression of the testes (Figure 1a–c). A final worm extended through the inguinal canal into the caudal aspect of the peritoneum. Additional ultrasonographic findings of moderate diffuse urinary bladder mural thickening, mild right ureter mural thickening, mild left renomegaly, and moderate cystic prostatomegaly were observed. Urinary bladder mural thickening was attributed to infectious or inflammatory causes of cystitis and ureteritis. Mild left renomegaly was thought to be secondary to lack of functionality of the right kidney and subsequent compensatory hypertrophy. Finally, cystic prostatomegaly was most consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia due to the sexually intact nature of the patient.

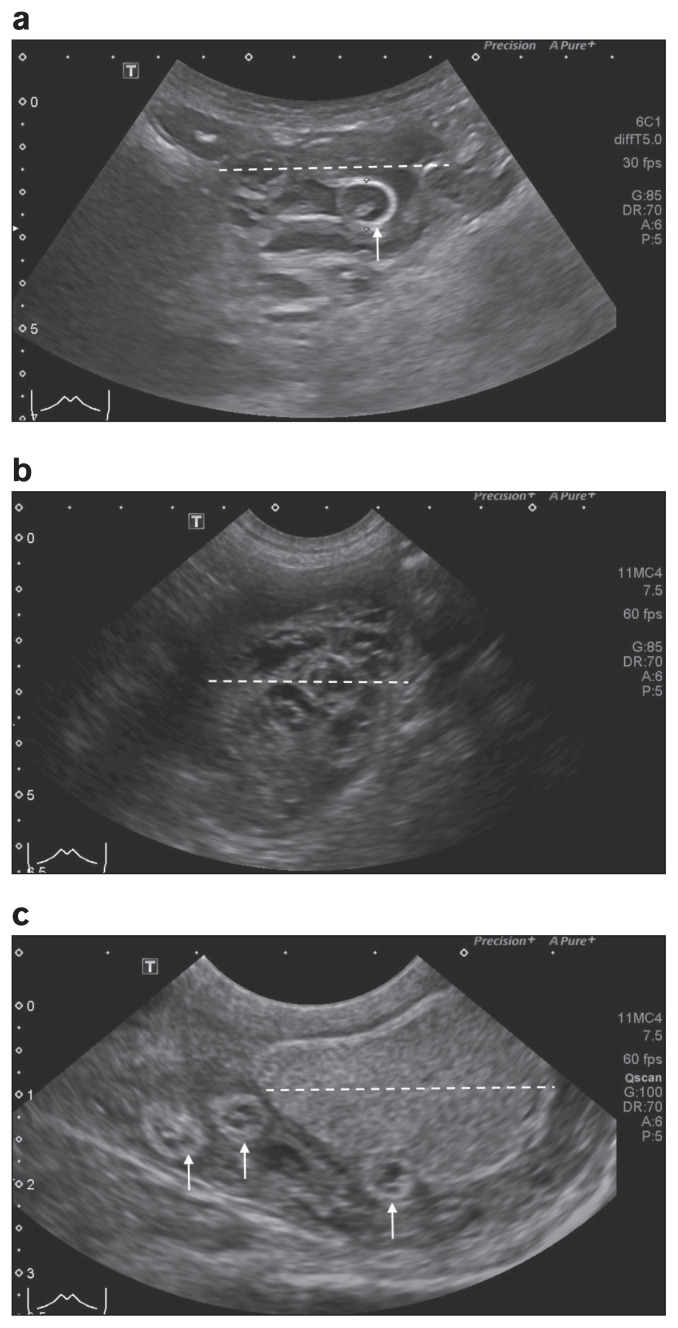

Figure 1.

a — Longitudinal ultrasound image of the right kidney (dashed white line) showing a tubular, 1.1-cm diameter, hyperechoic structure (white arrow) present in the right kidney and absence of normal renal parenchyma. b — Transverse ultrasound image of the right kidney (dashed white line) showing presence of multiple, hyperechoic tubular structures (up to 1.1 cm in diameter) within the kidney and absence of normal renal parenchyma. c — Longitudinal ultrasound image of the right scrotum showing the right testicle (dashed white line), and adjacent to the right testicle are 3, tubular hyperechoic structures, up to 1.0 cm in diameter (white arrows)

Three-view thoracic radiography was performed and was unremarkable. A complete blood (cell) count (CBC) revealed a mild leukocytosis (WBC 16.9 × 109/L, RR: 4.9 to 15.4 × 109/L) characterized by a mature neutrophilia (segmented neutrophil count 12.8 × 109/L, RR: 2.9 to 10.6 × 109/L) and monocytosis (1.4 × 109/L, RR: 0.0 to 1.1 × 109/L). A serum biochemistry profile revealed mild to moderate azotemia with elevations in urea (18.9 mmol/L, RR: 3.5 to 9.0 mmol/L) and creatinine (182 μmol/L, RR: 20 to 150 μmol/L). Laparoscopic right ureteronephrectomy and prescrotal castration were recommended along with removal of the free adult worm present within the inguinal canal/scrotum.

The following day the dog was anesthetized [induction: midazolam (Hospira Healthcare, Kirkland, Quebec), 0.3 mg/kg body weight (BW), IV, propofol (Fresenius Kabi Canada, Toronto, Ontario), 1.5 mg/kg BW, IV]; maintenance: isoflurane (Fresenius Kabi Canada) and positioned in dorsal recumbency to allow for draping of the ventral midline into the surgical field. The dog was then manually rotated 45 degrees into semi-lateral left recumbency. To obtain abdominal access, a single-incision, multi channeled laparoscopic port (SILS port; Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts, USA) was inserted caudal to the umbilicus on the ventral midline, using a 2 Rochester-Carmalt forceps technique (8), and 3 specialized, 6-mm cannulas for the single incision port were partially inserted. The abdomen was insufflated with carbon dioxide using pressure-regulated mechanical insufflation, to a maximum pressure of 8 mmHg. A 5 mm × 29 cm, 0 degree, laparoscope (Karl Storz Endoscopy, Goleta, California, USA) was inserted along with 1 additional 6-mm trocar-cannula assembly 3 cm cranial and 5 cm lateral to the single incision portal (Figure 2). Laparoscopic guidance was used to completely insert the single incision port cannulas. One 6-mm cannula was exchanged for a 15-mm cannula in the single incision port. Superficial exploration of the abdomen was performed and revealed an adult D. renale free within the peritoneal space (Figure 3). Laparoscopic Babcock forceps (Karl Storz Endoscopy) were inserted through a 6-mm cannula in the single incision port and used to grasp the free adult worm. The SILS port was removed while maintaining traction on the worm to allow for its extirpation from the abdomen. The SILS port was then reinserted; the remainder of the superficial exploration revealed multifocal yellow-tan adhesions throughout the liver, diaphragm, omentum, and right kidney. The remainder of the abdominal organs appeared grossly normal. A laparoscopic right-sided ureteronephrectomy was then performed using a previously described technique (9). A vessel-sealing device (Ligasure; Covidien) and right-angled forceps (Karl Storz Endoscopy) were introduced and the retroperitoneum was incised laterally along the right kidney and caudally over the proximal aspect of the ureter using the Ligasure. The proximal ureter was grasped to retract the kidney to allow for dissection of the renal hilus; the vessel-sealing device was used to seal and transect the renal artery and vein.

Figure 2.

Laparoscopic port set-up: patient in semi-left lateral recumbency with a single-incision, multi-channeled laparoscopic port (SILS port; Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts, USA) caudal to the umbilicus on ventral midline, with insufflation tubing, 2 specialized 6-mm cannulas and 1 specialized 15-mm cannula partially inserted into the port. A 6-mm trocar-cannula assembly is positioned 3 cm cranial and 5 cm lateral to the single incision portal (patients head is to the right of the image).

Figure 3.

Laparoscopic image of a free adult Dioctophyme renale in the peritoneal space.

The kidney was then dissected free from its remaining peritoneal attachments using the vessel-sealing device. Tension was placed on the ureter and the ureter was dissected to the level of its entrance to the urinary bladder. Laparoscopic hemoclips (Endo Clip; Covidien) were applied in triplicate before excision of the ureter using laparoscopic Metzenbaum scissors (Karl Storz Endoscopy), leaving 2 hemoclips on the remaining transected portion of the ureter. The right kidney and ureter were then placed into a specimen retrieval bag (Endo Catch; Covidien) and removed through the SILS port incision. The instrument ports were closed routinely in 3 layers before proceeding to castration.

A pre-scrotal incision was made over the left testicle and extended through the vaginal tunic. An adult D. renale was present within the vaginal tunic, cranial to the left testicle and was removed. The vaginal tunic had a granulomatous appearance and was discolored yellow. Thereafter, a routine open castration was performed and the vascular pedicle was divided using the vessel sealing device. When removing the right testicle, similar vaginal tunic changes were observed. The tunics and overlying tissues were closed routinely in 3 layers, and the right kidney, right ureter, and both testicles were submitted for histopathological evaluation.

Following surgery, the dog was allowed to recover in the intensive care unit and opioid (hydromorphone; Sterimax, Oakville, Ontario), 0.025 mg/kg BW, IV, q6h, analgesia was provided as well as IV fluid therapy. The following day the dog was bright and alert and comfortable upon abdominal palpation. Re-evaluation of the renal hematological parameters was undertaken and the azotemia present before surgery had improved (urea 10.8 mmol/L, RR: 3.5 to 9.0 mmol/L; creatinine 108 μmol/L, RR: 20 to 150 μmol/L). Based on the improved renal parameters and stable recovery, the dog was discharged to the care of his owners later that day, with gabapentin (Auro Pharma, Woodbridge, Ontario), 10 mg/kg BW, PO, q8h to 12h for pain relief.

Histopathological evaluation of the right kidney showed tubulointerstitial nephritis, characterized by lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with loss of renal tissue, tubular atrophy, and fibrosis. Within the right ureter and renal pelvis, there was urothelial hyperplasia with neutrophilic and histiocytic inflammation. In the testicular tissue, mesothelial hyperplasia with neutrophilic and histiocytic inflammation, tubular degeneration, and atrophy were present. The changes in the kidney, ureter, and testicles were consistent with inflammation secondary to mechanical irritation and immune stimulation by the intrarenal/intrascrotal D. renale. Eggs consistent with this parasite were observed in the subepithelial connective tissue of the remnant renal pelvis.

The dog was returned to the OVC-HSC 2 wk after surgery for repeat evaluation of renal parameters and urinalysis. Blood analysis revealed a persistent elevation in urea (14.6 mmol/L, RR: 3.5 to 9.0 mmol/L), creatinine within normal reference range (145 μmol/L, RR: 20 to 150 μmol/L) and elevated potassium (5.7 mmol/L, RR: 3.8 to 5.4 mmol/L), with a low sodium to potassium ratio (26, RR: 29 to 37). Urinalysis was performed on a free-flow sample, and showed adequate concentration (USG 1.025), with urine sediment examination revealing large numbers of variably preserved neutrophils. In addition, numerous, rod-shaped bacteria were found extracellularly and occasional intracellular bacteria were observed. Dioctophyme renale eggs were not identified and rare squamous epithelial cells were present. Urine culture confirmed infection with Escherichia coli and a 10-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (Clavaseptin; Vétoquinol, Lavaltrie, Quebec), 16 mg/kg BW, PO, q12h, was prescribed. Three weeks following completion of antimicrobial therapy, the dog was returned to the OVC-HSC for re-evaluation. Blood urea remained elevated (15.3 mmol/L, RR: 3.5 to 9.0 mmol/L) with normal creatinine (134 μmol/L, RR: 20 to 150 μmol/L). To further quantify renal function, an SDMA assay was performed and was within the normal range (14 μg/dL, RR: 0 to 14 μg/dL). Due to the previously low sodium to potassium ratio a resting cortisol was performed to screen for hypoadrenocorticism; the ratio was within the normal range (57.9 nmol/L, RR: 30 to 300 nmol/L). The urine was adequately concentrated (USG 1.029), and on sediment examination, leukocytes (20 to 30 per hpf ) and bacteria (3+) were present. As the sample was taken by free-catch and clinical signs of urinary tract infection had resolved, no further treatment was recommended.

At the time of most recent follow-up, 335 days after surgery, the dog was clinically normal.

Case 2

An 8-year-old, female, Labrador retriever dog from northern Manitoba underwent routine health screening prior to rehoming. Serum biochemistry including measurement of SDMA revealed normal renal and liver parameters. Urinalysis showed a USG of 1.016 with presence of 30 to 50 WBC per hpf, 0 to 2 RBC per hpf, marked bacteriuria (> 40 cocci per hpf ) and triple phosphate crystalluria (1 to 5 crystals per hpf ). No D. renale eggs were seen in the urine. Due to the pyuria with bacteriuria a 14-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was initiated, and, at re-evaluation 14 d later, an abbreviated abdominal ultrasonography study was performed. The study demonstrated a hydronephrotic right kidney, suspected to contain at least 1 D. renale worm. The dog was then referred to the OVC-HSC for pre-surgical assessment and treatment.

Upon presentation to the OVC-HSC the dog was bright, alert, and responsive with normal vital parameters. Thoracic auscultation, abdominal palpation, and peripheral lymph node evaluation were unremarkable. Clinical signs related to abnormalities in the urinary tract had not been reported and the remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. A renal health biochemistry profile revealed that there was no azotemia (urea 5.3 mmol/L, RR: 3.5 to 9.0 mmol/L; creatinine 75 μmol/L, RR: 20 to 150 μmol/L) and the electrolyte and protein measurements were within normal limits. Ultrasonographic examination of the urogenital tract showed almost complete effacement of the right renal parenchyma, leaving only a thin rim of tissue at the periphery. The remaining right renal tissue was small and abnormally shaped with a near tubular shape. Within the effaced renal parenchyma was a large, tubular, hypoechoic structure with hyperechoic walls, consistent with an adult female kidney worm (D. renale). The abdominal cavity was surveyed for other worms and no additional parasites were identified. The only additional sonographic abnormality of the urinary tract was a small volume of urocystic sediment, most consistent with crystalluria or small calculi. Laparoscopic right ureteronephrectomy was recommended.

The following day the dog was anesthetized for surgery [induction: (diazepam; Sandoz Canada, Boucherville, Quebec), 0.3 mg/kg BW, IV, (ketamine, Narketan; Vétoquinol), 6.25 mg/kg BW, IV; (maintenance: isoflurane, Fresenius Kabi Canada) with fentanyl (Sandoz Canada), constant rate infusion (CRI) 3 to 7 μg/kg BW per hour, IV]. The positioning of the dog, abdominal access using an SILS port and surgical procedure for laparoscopic right ureteronephrectomy were the same as described for the dog in case 1. During the surgical procedure, an adult D. renale worm was seen to be free within the peritoneal space. The free worm was removed using laparoscopic Babcock forceps. Similar to Case 1, superficial exploration of the abdomen revealed multifocal yellow-tan adhesions throughout the omentum and between the right lateral liver lobe and cranial pole of the right kidney. No tissues were submitted for histopathological evaluation.

Following surgery, the dog was allowed to recover in the intensive care unit and opioid (hydromorphone, 0.025 mg/kg BW, IV, q6h) analgesia was provided as well as IV fluid therapy. The following day the dog was bright and alert and comfortable upon abdominal palpation and was discharged to the care of her owners later that day, with gabapentin (Auro Pharma), 10 mg/kg BW, PO, q8 to q12 h for pain relief.

At the time of most recent follow-up, 183 d after surgery, the dog was clinically normal; monitoring of renal values was recommended.

Discussion

Dioctophyme renale, commonly known as the giant kidney worm, is a nematode that occasionally infects dogs. In Canada, where these cases occurred, reports of infection have been described in dogs in Manitoba (10,11) and southern Ontario (12). In addition, there is 1 report of a D. renale egg within a struvite urolith from a dog in western Ontario (13). Due to sub-clinical disease states caused by unilateral kidney infection (5), D. renale infection can be difficult to diagnose before destruction of renal parenchyma. To demonstrate infection, identification of parasite eggs in urine or worms on imaging is required (3,4,14). However, these diagnostic tests are not effective when an infection involves only male nematodes, immature parasites, or nematodes in ectopic locations. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test to detect anti-D. renale antibodies in the sera of dogs may be useful in diagnosing such cases but is not commercially available (15).

On initial evaluation, the male dog described here had azotemia and an inflammatory leukogram; however, urinalysis did not show evidence of D. renale eggs, likely representing an immature parasite infection and delaying the time to diagnosis. Three weeks later, parasite eggs were present in the urine, and ultrasound of the abdomen confirmed infection. As the dog was undergoing a screening evaluation prior to rehoming, was from a region where infection has been described in dogs, and had changes on blood analysis, consideration could have been given to a screening ultrasound examination of the urogenital tract at initial presentation. The female dog did not have evidence of azotemia or presence of D. renale eggs in her urine, and underwent a screening abdominal ultrasound at time of reevaluation for her urinary tract infection as she was from the same region as the previously evaluated male dog.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report to describe a laparoscopic surgical technique for ureteronephrectomy for the treatment of dioctophymosis in dogs infected in North America (3,4,6,7,16). A right-sided ureteronephrectomy was selected as the preferred method of worm removal in these cases as extirpation of the worm via nephrotomy may not have been the optimal treatment due to almost complete destruction of renal parenchyma visualized ultrasonographically. In cases in which bilateral infection is present, consideration could be given to bilateral nephrotomy for worm extirpation; however, the prognosis for adequate long-term renal function is uncertain. Other considerations for bilateral infection are renal transplant or euthanasia.

A laparoscopic procedure was used to minimize the size of the surgical incision and to allow for a shorter recovery period following surgery. Both dogs were hospitalized for less than 24 h after ureteronephrectomy and did not have any post-operative complications. Minimally invasive surgical procedures have been reported to reduce the incidence of pain and may reduce the incidence of wound complications compared to open surgical procedures (17–20). Laparoscopic procedures allow for conversion to open abdominal surgery should complications arise during dissection of the kidney and/or ureter. Hemorrhage, massive dilation of the affected ureter or adhesions that could not be addressed laparoscopically are examples of potential causes for conversion to traditional open laparotomy during laparoscopic ureteronephrectomy (9). In the male dog described here, mild thickening of the distal ureter had been noted on ultrasound before surgery but was not a complicating factor during surgery. Potential complications arising from ureteronephrectomy include iatrogenic damage to the contralateral ureter and the ureteral stump acting as a nidus for chronic infection if it is not resected at the level of the ureterovesicular junction (9).

Monitoring of hematological and serum biochemical parameters, and urinalysis is required in dogs following nephrectomy to ensure that the remaining kidney is functioning adequately. In the male dog of this report, urea remained elevated at the 24-hour, 2-week, and 5-week postoperative checks, but all readings were lower than the values obtained before surgery. Creatinine remained within the normal reference range, although as it was at the high end of the normal range this is considered chronic kidney disease stage II according to the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS), but there was no other evidence of declining renal function on urinalysis or SDMA evaluation. This may be attributed to compensatory function of the enlarged left kidney seen on ultrasound prior to surgery. In a study of 8 dogs that had right renal nephrectomy to treat dioctophymosis (16), there was inconsiderable change in hematological, serum biochemical, and urinalysis findings pre- and post-surgery, which was also attributed to functional compensation by the remaining left kidney. Similarly, in healthy canine kidney donors that have undergone unilateral nephrectomy, blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine concentrations remained within the normal reference range for up to 2.5 y following donation (21). Proteinuria has been reported in dogs after experimental unilateral nephrectomy (22); however, renal function remained stable and did not progress to chronic kidney disease. Further monitoring of the renal function in the dogs of the present report during routine geriatric health checks is recommended. Additional renal function testing such as evaluation of glomerular filtration rate in the contralateral kidney (3) was considered prior to ureteronephrectomy; however, this was not performed as it would not have altered the treatment plan.

This report describes the use of laparoscopy for right ureteronephrectomy as part of the surgical treatment for D. renale infection in 2 dogs. Minimally invasive surgery is frequently performed in companion animal practice and is being applied for more advanced surgical procedures. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Mace TF, Anderson RC. Development of the giant kidney worm, Dioctophyma renale (Goeze, 1782) (Nematoda: Dioctophymatoidea) Can J Zool. 1975;53:1552–1568. doi: 10.1139/z75-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Measures L, Anderson RC. Centrarchid fish as paratenic hosts of the giant kidney worm, Dioctophyma renale (Goeze, 1782), in Ontario. Can J Wildl Dis. 1985;21:9–11. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-21.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreira VL, Medeiros FP, July JR, Raso TF. Dioctophyma renale in a dog: Clinical diagnosis and surgical treatment. Vet Parasitol. 2010;168:151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paras KL, Miller L, Verocai GG. Ectopic infection by Dioctophyme renale in a dog from Georgia, USA, and a review of cases of ectopic dioctophymosis in companion animals in the Americas. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports. 2018;14:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2018.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osborne CA, Stevens JB, Hanlon GF, Rosin E, Bemrick WJ. Dioctophyma renale in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1969;155:605–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Secchi P, Valle SF, Brun MV, et al. Videolaparoscopic nephrectomy in the treatment of canine dioctophymosis. Acta Scientiae Veterinariae. 2010;38:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartmann HF, Oliveira MT, Feranti JPS, et al. One-stage laparoscopic nephrectomy and ovariohysterectomy for concurrent dioctophymosis and pyometra in a bitch. Acta Scientiae Veterinariae. 2018;46:282. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright T, Singh A, Mayhew PD, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted splenectomy in dogs: 18 cases (2012–2014) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2016;248:916–922. doi: 10.2460/javma.248.8.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayhew PD, Mehler SJ, Mayhew KN, Steffey MA, Culp WTN. Experimental and clinical evaluation of transperitoneal laparoscopic ureteronephrectomy in dogs. Vet Surg. 2013;42:565–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2013.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLeod JA. Dioctophyma renale infections in Manitoba. Can J Zoology. 1967;45:505–508. doi: 10.1139/z67-064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatfield C, Jones WG. Giant kidney worm in canine abdomen. Can Vet J. 1964;5:276–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrison A, Peregrine AS. Dioctophyme renale infection in a Labrador mix. Vet Tech J. 2008 May;:294–299. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whelen JC, Houston DM, White C, Farvin M. Ova of Dioctophyme renale in a canine struvite urolith. Can Vet J. 2011;52:1353–1355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahal SC, Mamprim MJ, Oliveira HS, et al. Ultrasonographic, computed tomographic, and operative findings in dogs infested with giant kidney worms (Dioctophyme renale) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;244:555–558. doi: 10.2460/javma.244.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedrassani D, do Nascimento AA, André MR, Machado RZ. Improvement of an enzyme immunosorbent assay for detecting antibodies against Dioctophyma renale. Vet Parasitol. 2015;212:435–438. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesquita LR, Rahal SC, Faria LB, et al. Pre- and post-operative evaluations of eight dogs following right nephrectomy due to Dioctophyma renale. Vet Q. 2014;34:167–171. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2014.924166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devitt CM, Cox RE, Hailey JJ. Duration, complications, stress and pain of open ovariohysterectomy versus a simple method of laparoscopic-assisted ovariohysterectomy in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;227:921–927. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.227.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh PJ, Remedios AM, Ferguson JF, Walker DD, Cantwell S, Duke T. Thoracoscopic versus open partial pericardectomy in dogs: Comparison of post-operative pain and morbidity. Vet Surg. 1999;28:472–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1999.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Culp WTN, Mayhew PD, Brown DC. The effect of laparoscopic versus open ovariectomy on postsurgical activity in small dogs. Vet Surg. 2009;38:811–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2009.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayhew PD, Freeman L, Kwan T, Brown DC. Comparison of surgical site infection rates in clean and clean-contaminated wounds in dogs and cats after minimally invasive versus open surgery: 179 cases (2007–2008) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;240:193–198. doi: 10.2460/javma.240.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urie BK, Tillson DM, Smith CM, et al. Evaluation of clinical status, renal function, and hematopoietic variables after unilateral nephrectomy in canine kidney donors. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;230:1653–1656. doi: 10.2460/javma.230.11.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finco DR, Brown SA, Crowell WA, et al. Effects of aging and dietary protein intake on uninephrectomized geriatric dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1994;55:1282–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]